Abstract

Undoubtedly, coronavirus (COVID-19) has caused one of the biggest challenges of all times. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has caused more than 150 million infected cases and one million deaths globally as of May 5, 2021. Understanding the sentiment of people expressed in their social media comments can help in monitoring, controlling, and ultimately eradicating the disease. This is a sensitive matter as the threat of infectious disease significantly affects the way people think and behave in various ways. In this study, we proposed a novel method based on the fusion of four deep learning and one classical supervised machine learning model for sentiment analysis of coronavirus-related tweets from eight countries. Also, we analyzed coronavirus-related searches using Google Trends to better understand the change in the sentiment pattern at different times and places. Our findings reveal that the coronavirus attracted the attention of people from different countries at different times in varying intensities. Also, the sentiment in their tweets is correlated to the news and events that occurred in their countries including the number of newly infected cases, number of recoveries and deaths. Moreover, common sentiment patterns can be observed in various countries during the spread of the virus. We believe that different social media platforms have great impact on raising people’s awareness about the importance of this disease as well as promoting preventive measures among people in the community.

Keywords: Deep learning, Coronavirus (COVID-19), Sentiment analysis, Information fusion, Tweet analysis

1. Introduction

The sudden spread of COVID-19 virus observed in animal and/or bird populations which became infectious and damaging in humans has become a cause of concern for scientists and policymakers. The COVID-19 called by the World Health Organization as a pandemic has endangered human lives all over the world [1]. Some geographies have few cases, others with early community transmission have a few hundred, and those with uncontrolled, pervasive transmission have tens of thousands. To minimize the number of infected people, several strategies including social distancing measures, travel bans, self-quarantines, and business closures have been implemented, which rapidly transform the structure of societies all around the world. This situation progresses day by day; therefore, speedy and on-time information release is a top priority for disease control and prevention. Besides, the threat of infectious disease significantly affects how people think and behave in various ways. Some of the observed changes over the last months are stockpiling and increased fear has substantial consequences on societal well-being, health, and the global economy [2]. In response to this unprecedented situation, governments have initiated extraordinary public-health and economic responses. We are observing a remarkable restructuring of the economic and social order in which business and society have traditionally operated.

Over the last few months, some epidemiological studies have been done to characterize and control the coronavirus disease. In a study conducted by Holshue et al. [3], described the identification, diagnosis, clinical course, and management of the first case of 2019-nCoV infection confirmed in the United States. Their findings emphasized the importance of direct management between clinicians and public health authorities at the local, state, and federal levels, as well as the need for rapid broadcasting of both hygiene information to prevent more spread of the disease and clinical information to care patients with this evolving infection. In another study published by Perlman [4] highlighted the importance of collecting many temporally and geographically unrelated clinical isolations to evaluate the extent of virus transformation and measure whether these transformations specify adaptation to the human host. One of the topics mentioned worth studying is the impact of physical-distancing measures. We know that meticulous, at-scale physical-distancing measures can result in substantial reduction in the number of new COVID-19 cases. Though, the range of methods in use and level of severity with which they are being employed to learn about what exactly works and how long it takes requires more investigation. Many studies are being conducted to find out more about the epidemiological impacts of this disease and much still needs to be learned about this infection.

The other key concern during this unprecedented time is the resilience of economy in response to this pandemic. In a study conducted by FitzGerald et al. [5], COVID-19 pandemic is coined as “instant economic crisis”, and they investigated how deep and long the economic crisis will last. They discussed the cautious reopening of social and economic lives. Also, it studied the effects of restrictions applied to populations to halt the fast spread of the virus, including quarantines, stay-at-home orders, business closures, and travel prohibitions which led to an enormous decline in world economy. The data to quantify these impacts are still coming; however, early statistics show that 30 million Americans so far have applied for unemployment aids in the week ending on May 9th. To deal with this situation, they proposed 5 stages of strategies, including resolve, resilience, return, re-imagination, and reform. Cadena et al. [6] carried out a study on how to restart national economies during the coronavirus crisis. They indicated that the world must act on both controlling the virus and alleviating the negative impact on citizens’ businesses at the same time. The improvement we make on those fronts will help to shape the economic recovery. Illanes et al. [7] investigated the impact of coronavirus on higher education and how they respond. They proposed an integrated nerve center which is a simple, flexible, multidisciplinary construct intended to adjust to fast-changing conditions. It contained four types of actions including discover, decide, design, and deliver. The main goal of the proposed integrated nerve center is for the institution to be efficient in getting ahead of events and react timely, cleverly, and tactically. Qiu et al. [8] scrutinized the role of several socioeconomic factors in facilitating the transmissions of COVID-19 at the local and cross-city levels in China. A machine learning method is used to choose critical parameters that robustly can predict virus transmission among the rich exogenous weather characteristics.

Nowadays, many methods to share information have been incorporated by massive social media platforms in high speed, and penetration. More than 2.9 billion individuals use social media frequently, and a lot of them for long periods of time. Sharma et al. [9] designed a dashboard to analyze the misinformation in Twitter conversations during these unprecedented times. This dashboard provided visibility to the social media discussions around coronavirus and the quality of information shared on the platform as the situation progressed. They also designed a detection method to find misleading, deceiving and clickbait contents from Twitter information flow. In another study, Merchant and Lurie [10] investigated the role of social media as a key tool in handling the on-going pandemic along with changing features of preparedness and response for future disasters. They emphasized that social media should be utilized to circulate accurate information about different critical topics during the pandemic, like when to test, what to do with the results, and where to receive care. In addition to the mentioned problems, few studies addressed the problem of event detection [11]. For example, Doulamis et al. [11], classified twitter analysis methods based on tasks, types of events, and the orientation of tweets’ content. In a similar study, Farzindar and Khreich [12] reviewed event detection in Twitter data based on the types of events, features, detection methods, and tasks. Recently, Saeed et al. [13] classified existing methodologies for Twitter event detection and highlighted their limitations. They also proposed few solutions to address the shortcomings of existing methodologies.

The people are being forced out of public spaces, much discussion about Coronavirus now happens online, e.g., on social media platforms such as Twitter. As an increasing number of people rely on the social media platform, now the question is how we can leverage social media data to help with mitigation and control of COVID-19 pandemic. However, there is no study yet to understand the public’s perception and opinion about COVID-19 pandemic. The goal of this study is to track people’s sentiments to gauge how their expectations, perceptions, and behaviors change throughout the crisis across multiple countries over time. This study aims to answer the following questions related to coronavirus:

-

•

Is there a difference in the sentiment intensities of Twitter users shown in the coronavirus-related tweets in eight countries?

-

•

Is there a meaningful correlation between the number of newly infected cases, new recoveries, and deaths with tweets’ sentiment in different dates and countries?

To answer the above-mentioned research questions, we proposed a new method based on the fusion of deep and classical supervised learning methods. In this approach, four deep learning and one classical supervised classification models are first trained on a large labeled dataset of tweets and then, as a late fusion method, a meta learner is trained on the features obtained using five classification methods. This trained learner is finally used to classify the unlabeled coronavirus-related tweets. The reason for applying both classical and deep classification models is that different types of test samples can be classified using these models [14]. Also, it has been shown that the fusion method can achieve higher performance than simple machine learning methods in different applications [15], [16], [17], [18], [19].

In addition to the two above-mentioned coronavirus-related questions, we aim to answer the following research question:

Does the proposed fusion model improve the performance of sentiment classification of tweets?

Understanding the dynamics of public responses to such events under uncertainty is necessary to avoid unnecessary panic and provide a proper response. This study used geotagged Twitter data from eight English-speaking countries including the US, UK, Canada, and Australia as well as some non-English-speaking counties including Iran, China, Spain, and Italy to collect a wide range of public opinion data and track the public reaction to coronavirus. The results of this study will help to identify factors that shape the public reactions to coronavirus in the context of this rapidly unfolding public health emergency. The study findings will also help to provide guidance to the public health authorities to communicate well with people and help to provide public health responses to those who are most susceptible to the virus.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

•

Proposes a new fusion model for sentiment analysis of tweets by combining state-of-the-art transformer-based deep models. This model is trained and validated using large-scale Twitter dataset.

-

•

A new real-world large-scale Twitter dataset of coronavirus-related tweets of people in 8 highly affected countries is collected and analyzed to develop the deep model.

-

•

Collected Twitter dataset, Google trend data from 8 countries are analyzed to find meaningful patterns related to coronavirus.

-

•

Analysis of coronavirus-related tweets and Google trend data for the 8 countries is presented to find the sentiment of people in different time intervals and countries.

-

•

Results of this study may help social scientists and governments in finding the temporal and geographical sentiment of people regarding the coronavirus.

2. Existing research on the analysis of COVID-19 in microblog texts

Few studies on Twitter analysis of COVID-19 have been reported recently. In this section, we briefly discussed the most related studies and compared them with the current study.

Zhu et al. [20] analyzed 8 topics extracted from Weibo microblog data from spatiotemporal perspectives. There are four major differences between this study and our study. First, they analyzed Weibo text while we analyzed Twitter data. Second, they focused on different spatial zones of China while we analyzed tweets from 8 different countries. Third, they analyzed microblog texts from spatiotemporal view while we analyzed tweets from an emotional point (i.e., sentiment analysis). Fourth, they addressed classical machine learning methods for extracting and analyzing topics in microblog texts while we employed both deep learning and classical machine learning methods for sentiment classification of tweets.

Zhao and Xu [21] discussed the public attention in two-month time intervals to COVID-19-related events in China through Sina Microblog. They analyzed the hot topics and sentiment trends in this time interval and reported “the emotional tendency of public toward the COVID-19 epidemic-related hot topics has changed from negative to neutral, with negative emotions weakening and positive emotions increasing as a whole” [21]. The main differences between this study and ours are as follows. First, they analyzed Sina microblog texts while we analyzed Twitter data. Second, they focused only on China while we analyzed tweets for 8 different countries. Third, they analyzed a short two-month period while we analyzed a six-month time interval. Four, they focused on the public attention toward different aspects of COVID-19, while we focused on the sentiment change over time.

Saleemi [22] analyzed the relationship between cost-based market liquidity and investors’ sentiment analysis of Twitter data. The results of this study showed that “Twitter sentiment indicators are relevant in the forecasting of market liquidity and execution cost at market level” [22]. The main differences between this study and ours are as follows. One, they analyzed the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) related tweets while we analyzed COVID-19 Twitter data. Second, they focused only on Australia while we analyzed tweets for 8 different countries. Third, they focused on the relation between market and sentiment of investors’ tweets, while we addressed the problem of sentiment analysis of the COVID-19 related tweets.

Barkur et al. [23] proposed a model to analyze the sentiment of Indians through lockdown announcements. They analyzed 24000 tweets and showed that “Even though there is negativity, fear, disgust, and sadness about the lockdown, the positive sentiments stood out” [23]. The main differences between this study and ours are as follows. First, they only analyzed Indian related tweets while we analyze tweets for 8 different countries. Second, they only analyzed tweets for a short time interval from March 25th to 28th, 2020 while we analyzed tweets published in a six-month time interval. Thirdly, they focused on emotions like fear, disgust, and sadness, while we addressed the problem of sentiment analysis of COVID-19 related tweets. Finally, they only considered two keywords namely, #India Lockdown and #India fights Corona for collecting tweets while we used more than 20 COVID-19 keywords.

Wang et al. [24] compared public opinion towards COVID-19 between California and New York. They reported that “COVID-19 tweets from California had more negative sentiment scores than New York” [24]. Also, they showed similar trend over time in both states. The main differences between this study and ours are as follows. First, they only analyzed two states of USA tweets while we analyzed tweets for 8 different countries. Second, they only analyzed tweets for a short time interval from March 5, 2020, to April 2, 2020, while we analyzed tweets published in a six-month time interval. Third, they employed the VADER tool for sentiment analysis while we proposed a fusion of deep and classical machine learning models for sentiment analysis of tweets.

Chen et al. [25] analyzed the use of neutral and controversial terms for COVID-19 on Twitter. They showed substantial difference between the emotion in tweets containing controversial and non-controversial terms. The main differences between this study and ours are as follows. First, they analyzed a few specific controversial and non-controversial terms while we analyzed general COVID-19 terms. Second, they only analyzed tweets for a short time interval from March 5, 2020, to April 5, 2020, while we analyzed tweets published in a six-month time interval. Third, they employed LIWC2015 that is a dictionary-based linguistic analysis tool for sentiment analysis while we proposed a fusion of deep and classical machine learning models for sentiment analysis of tweets. Four, they focused on emotions like fear, disgust, and sadness, while we addressed the problem of sentiment analysis of COVID-19 related tweets.

Jelodar et al. [26] proposed to use a recurrent deep learning method for sentiment classification of microblogging texts related to COVID-19. Specifically, they proposed a model to extract COVID-19 related topics. There are few major differences between this study and our study. First, they analyzed reddit text while we analyze Twitter data. Second, they did not consider country-specific comments while we analyzed tweets for 8 different countries. Third, they used long short-term memory (LSTM) as a deep learning method while we employed both deep learning and classical machine learning methods for sentiment classification of tweets. Finally, they focused on the extraction of topics while we focused on the extraction of sentiment intensity of Twitter users toward COVID-19.

In summary, the existing works on the analysis of COVID-19 microblog texts are proposed for spatiotemporal analysis [20], topic analysis [21], [26], market liquidity [22], event analysis [23], term analysis [25]. In contrast to the existing methods, this study focused on the extraction of sentiment intensity of Twitter users in 8 countries toward COVID-19. In addition to this difference, this work presents a new COVID-19 Twitter dataset extracted for a duration of four months. We showed the relationship between a number of infected cases and death due to COVID-19 and the change in the sentiment intensity of Twitter users.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Motivation

Sentiment analysis [27], [28] aims to find people’s opinions and attitudes from their comments in social media toward different aspects of products and events [28], [29]. It has been studied in different languages [30], [31], [32], [33], [34] and performed on the comments of different social media [35], [36], [37]. Sentiment analysis of different Twitter data has been studied in the literature such as critical events [38], drug reviews [14], classifying Twitter streams during outbreaks [39], prediction of the early impact of literature [40], halal products on Twitter [41], consumer sentiment towards a particular brand [42], [43], and many other subjects [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]. In the past few decades, advances in machine learning and particularly deep learning technologies/methods, sentiment analysis of variety of resources have gained significant attention [47], [48]. Hence, in this study, we have investigated the public opinion towards COVID-19 in eight countries mentioned in 4.1 to 4.8 using artificial intelligence techniques. We have made an effort to understand to seriousness of people to pandemic during the specified period. It may be noted that in this study, we are presenting the opinion of a group of people in these eight countries as case studies. Our results reflect the opinion and sentiments of citizens of these countries who tweeted their opinion about COVID-19 using the keywords shown in Table 1.

As discussed earlier, sentiment analysis is a meticulous method used to achieve public opinion of subjects. With the onset of coronavirus in late 2019 and its spread in early 2020, we have decided to focus on analyzing people’s opinions and their thinking about the impacts of COVID-19 in eight countries which are severely affected by this disease. Examining past studies along with our previous experience shows that analyzing the people’s general opinion can reveal how seriously people have taken the disease. This can provide insight to the governments and organizations about their involvement with this disease to develop better solutions to the disease for their citizens.

3.2. Data

In this study, we employed two sources of data, namely Google Trends and Twitter data. Google Trends data was used to analyze the interest of people to obtain information about COVID-19 disease using Google searches of related keywords. This type of data has been used for different applications including predicting the stock market [49], detecting emerging political topics on Twitter [50], and predicting the speed of national spread coronavirus [51]. Twitter data was used to analyze the change of sentiment in peoples’ tweets over time. The same keywords and time intervals were used to obtain both Google Trends and Twitter data. Specifically, we crawled the data from 2020-01-01 to 2020-04-21 and filtered the initial dates for which there was no tweets associated with the keywords. This shifted the beginning of the time frame to 2020-01-24. Keywords listed in Table 1 were used to crawl the tweets and retrieve Google Trends. In addition to the above keywords, we also considered the hashtag sign at the beginning of keywords in the crawling process.

Table 1.

List of keywords used to crawl the tweets and retrieve the normalized Google Trends.

| Corona | Coronavirus | COVID-19 | SARS-CoV-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| nCoV | SARS-CoV-2 | 2019-nCoV | COVID-2019 |

| SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV2 | SARS-CoVs | MERS-CoV |

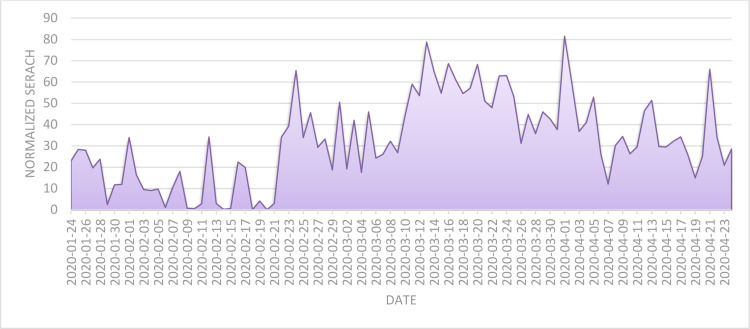

3.2.1. Google Trend data

Google Trends is a popular service offered by Google to obtain a normalized count of users’ searches for a given phrase in a specific time frame. This service returns a number in the range 0 (lowest number of searches)-100 (highest number of searches) for the given keywords in the provided time frame. The normalized search number of Google Trends service used to compare “Coronavirus” and “corona” in a three-month time frame from 2020-01-24 is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Comparing the normalized search number of “Coronavirus” and “corona” in a three-month time frame from 2020-01-24 using Google Trends website https://trends.google.com.

In this study, we did not use the Google Trends website directly, instead, we used Pytrends1 library written in the Python language to have more flexibility in obtaining relevant data needed for our analysis.

3.2.2. Tweets

All keywords shown in Table 1 were used to filter the tweets extracted from 8 countries including United States, China, Iran, Italy, Spain, Australia, England, and Canada from to :

Twint2 library of Python was used to collect geo-tagged tweets for the specified keywords and time frame. For each country, we selected only English tweets. Table 2 summarized the number of tweets, average length, and average number of words.

Table 2.

Specifications of tweets collected for 8 countries.

| Country | Number of tweets | Average length | Average number of words |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 3,57,449 | 185.245 | 24.423 |

| China | 82,887 | 207.575 | 26.223 |

| Iran | 19,506 | 190.783 | 24.333 |

| Italy | 44,107 | 194.717 | 22.858 |

| Spain | 38,410 | 192.714 | 22.445 |

| Australia | 1,64,915 | 201.317 | 25.275 |

| England | 3,24,173 | 192.904 | 25.952 |

| Canada | 24,602 | 199.319 | 24.653 |

3.3. Proposed model

To evaluate the overall performance of the sentiment of tweets, a new fusion model is proposed in this study. The overall architecture of the proposed model is shown in Fig. 2. The first layer of the proposed method consists of four deep learning and one classical supervised classification models. The reason for applying both classical and deep classification models is that different types of test samples can be classified using these models [14]. In fact, according to the theory of three-way decisions [52], data samples that belong to the low-confidence decision region of one classifier may belong to the high-confidence decision region of another. Hence, using different types of classifiers may improve the overall confidence of the classification system and improve the accuracy of the results.

Fig. 2.

Proposed model to analyze the sentiment analysis of tweets.

In the next subsections, each classification method is described.

3.3.1. Naïve Bayes Support Vector Machines (NBSVM)

This model is a text classification method proposed by Wang and Manning [53] takes the classical support vector machine (SVM) and combines it with Bayesian probabilities. In this model, word count features are replaced by Naïve Bayes log-count ratios:

| (1) |

where, p and q are word count vectors for a binary classification problem with the label as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Here, is the feature count vector for training sample i and V is the set of features. This model is shown to be not only fast but also accurate for different text classification problems.

In the current study, we implemented a simple neural implementation of NBSVM which consists of two embedding layers followed by a sigmoid activation layer. The input document to this model is represented as a sequence of words IDs. The reason for using representation is that this model trains much faster than one using term-document matrix because the look-up mechanism of the embedding layer reduces the number of parameters and words. In the NBSVM model, the first embedding layer stores the Naïve Bayes log-count ratios which are the probability of a word appearing in a document in one class versus another. The second layer stores learned coefficients for each word in the document. The final prediction of the model is simply the dot product of these two vectors. The main benefit of this simple neural implementation is that its training process is very fast as it is using a graphics processing unit (GPU).

3.3.2. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

The 1D-CNN model used in this study is shown in Fig. 3(a) [54]. This model consists of an embedding layer which is used for mapping vocabulary indices into an embedding space. Specifically, given a sentence s composed of M words , we first transform each word into a word embedding . Given a word w, its embedding is obtained using the following matrix–vector product:

| (4) |

where, is the embedding matrix and is a vector of size with value 1 at index w and zero in all other positions. A sequence of word embeddings of length M, , is sent to the next layer which is a dropout layer. Dropout is used for regularization and avoid overfitting problems.

Fig. 3.

Proposed method comprising of: (a) CNN, (b) BiGRU, and (c) fastText (See Fig. 2).

A 1D convolution layer is employed to learn word feature maps. In the convolution layer, a filter F of size M h is repeatedly applied to the sub-matrices of the input matrix to produce a feature map in which:

| (5) |

where, and is a sub-matrix of S from row i to j.

Global max pooling is used as the next operation to down-sample feature maps and to reduce the parameter size of the following fully-connected layers. Max-pooling is a popular pooling strategy to select the most significant feature msf of the feature map M as follows:

| (6) |

The outputs of the global max-pooling layer are concatenated and sent to the next layer as a pooled feature vector. A dense (fully connected) layer is used as the hidden layer of the network followed by a dropout layer. Finally, the output layer consisting of a dense layer with two Softmax cells is used for classification. The parameter setting of the CNN model is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Details of hyperparameters used for the proposed CNN model.

| Parameter name | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Max features | 20,000 | Vocabulary size of the embedding layer. |

| Embedding dim | 50 | Embedding dimension. |

| Dropout | 0.2 | Dropout rate |

| Number of filters | 250 | Number of filters in the convolution layer. |

| Kernel size | 3 | Kernel size in the convolution layer. |

| Activation function | Relu | Activation function of the convolution layer |

| Dense | 250 | Number of neurons in the hidden layer. |

| Loss function | Categorical cross entropy | Loss function of the output layer. |

| Optimizer | Adam | Optimization algorithm of the model. |

3.3.3. Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Network (BiGRU)

To model long dependencies in the text, gated recurrent network (GRU) is used [55]. Bidirectional GRU (BiGRU) is a special type of GRU which extracts sequential dependencies in both forward and backward directions. The BiGRU enables the model to consider both the preceding and succeeding contexts. This is an important feature because considering the context of sentiment words is an important problem in sentiment analysis applications [56]. In the proposed system, the BiGRU model shown in Fig. 3(b) is used. Similar to the CNN model described in 3.3.2, BiGRU model consists of an embedding layer for mapping vocabulary indices into an embedding space followed by a dropout layer. However, this model employed pre-trained word vectors trained on “common crawl” and “Wikipedia” using fastText model [57]. This word vector is trained using CBOW with position-weights. After the dropout layer, a BiGRU layer is applied to extract both the forward and backward contexts. This layer consists of GRU cells which employ two gates, an update gate r combining forget and input gates used in standard Long Short-Term Memory cells (LSTMS), and a reset gate z. The update and reset mechanisms are based on the following functions:

| (7) |

| (8) |

where, is the logistic sigmoid function, U and W are the weight matrices of gates, and are input and hidden state, and b shows the bias vector. The output of the cell is computed using the value of the input and the hidden state. The hidden state of the cell is computed using the following functions:

| (9) |

| (10) |

To extract both the future and preceding contexts, two hidden layers and , are combined in the BiGRU layer. This provides the temporal information flow in both directions.

In addition to the global max pooling, a global average pooling layer is also applied to the output of the BiGRU model to obtain different feature maps. The outputs of the pooling layers are then concatenated and sent to a fully connected dense output layer. The parameter setting of the BiGRU model is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hyperparameter setting used for BiGRU model.

| Parameter name | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Max features | 20,000 | Vocabulary size of the embedding layer. |

| Embedding dim | 300 | Embedding dimension. |

| Dropout | 0.2 | Dropout rate |

| Number of cells | 80 | Number of GRU cells in the BiGRU layer. |

| Activation function | Relu | Activation function of the convolution layer |

| Dense | 2 | Number of neurons in the output layer. |

| Loss function | Categorical cross entropy | Loss function of the output layer. |

| Optimizer | Adam | Optimization algorithm of the model. |

3.3.4. fastText

The fastText model used in this study (see Fig. 3) is similar to the original fastText model [58] and has similar embedding, spatial dropout, and global max-pooling layers as described in 3.3.2, 3.3.3. Moreover, the fastText model uses batch normalization layer to improve the training speed and performance of the model.

The input to the fastText model is a bag-of-words representation. This representation is then fed to a lookup layer, where the embeddings are computed for every single word. In the next step, word embeddings are averaged to attain a single embedding for the whole text. The hidden layer has parameters. Finally, the averaged vector is fed to a linear classifier which is a softmax function in this study. The parameter setting of the fastText model is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hyper parameters used for fastText model.

| Parameter name | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Max features | 20,000 | Vocabulary size of the embedding layer. |

| Embedding dim | 64 | Embedding dimension. |

| Spatial Dropout | 0.25 | Dropout rate |

| Activation function | Relu | Activation function of the convolution layer |

| Dense 1 | 64 | Number of neurons in the hidden layer. |

| Dropout | 0.5 | Dropout rate |

| Dense 2 | 2 | Number of neurons in the output layer. |

| Loss function | Categorical cross entropy | Loss function of the output layer. |

| Optimizer | Adam | Optimization algorithm of the model. |

3.3.5. DistilBERT

DistilBERT [58] is proposed to reduce the size and improve the training speed of original bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) model [59]. The DistilBERT model is pre-trained by concatenating “English Wikipedia” and “Toronto book corpus” [60]. The original BERT model has 24 transformer blocks, a hidden size of 1024, and 16 self-attention heads with 340 million parameters. In the DistilBERT model, the number of layers is reduced by a factor of two. This makes the DistilBERT model 60% faster than the original BERT model [59]. As pointed out in [59], “DistilBERT was trained on 8 16GB V100 GPUs for approximately 90 hours”. This is much faster and less memory intensive than similar architectures such as RoBERTa [61] model which requires one day of training on 1024 32GB V100.

3.3.6. Meta learner

To fuse the five base learners (see 3.3.1 to 3.3.5), several strategies can be used. In this study, we selected a stacked generalization mechanism. Stack generalization is a fusion method used to train a new learner (meta learner) to fuse the output of base learners, trained on the same training data set [60], [62]. Stack generalization conditionally assigns different weights to its inputs (i.e., the outputs of base learners) [63]. The pseudo-code of stack generalization mechanism is shown in Algorithm 1 [48]. The input to the algorithm is a training dataset , a test vector , a set of base learners , and a meta learner . The result of applying algorithm to the test vector is a prediction vector which specifies the labels of samples in . The first step in the algorithm is to split into S almost equal folds. Then, each learner is applied to all folds except one () and produce a temporary prediction vector . Finally, a new training dataset for the meta learner is created by concatenating the temporal predictions. This new dataset is used to train the meta learner.

When using stack generalization, the base learners must be accurate and diverse [60]. Hence, we selected five different classification methods described in 3.3.1 to 3.3.5. Specifically, all the base learners are accurate as they have lower classification errors than the random classifier and they are expected to be diverse as their structures are totally different. The XGBoost method [64] is used in this study as the meta learner. This method is a computationally efficient implementation of an iterative gradient boosting algorithm to create a fusion of weak regression trees [65].

3.4. Training the model

The Twitter data downloaded (see 3.2.2) has no sentiment label and hence cannot be used to train the models. Our proposed model is a deep learning model, needs a large training dataset to train the model. To address this problem, we used the Stanford Sentiment140 dataset [66] containing 1,600,000 tweets labeled as positive or negative. During the training process, we randomly selected 80% of the tweets for training the models and 20% for validation.

4. Results

As shown in Table 2, more than one million Twitter posts are collected for 8 countries during these three months. In order to analyze these data, we applied the six above-mentioned deep learning methods to the tweets of the Stanford Sentiment140 dataset [66]. This is because we aim to evaluate the performance of these algorithms on such well-known labeled data. To do so, as discussed earlier, we employed the following algorithms: CNN, BiGRU, fastText, NBSVM, DistilBERT, and the proposed fusion model. Also, to evaluate the performance of these methods, we used both accuracy and F1-score in the testing stage as described in Eqs. (11) to (14).

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

where, TP, TN, FP, and FN are true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative, respectively. The obtained results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of classification performance obtained using various algorithms with Stanford Sentiment140 dataset.

| Method | Accuracy | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|

| Proposed model | 0.858 | 0.858 |

| CNN | 0.816 | 0.815 |

| BiGRU | 0.797 | 0.797 |

| FastText | 0.796 | 0.796 |

| NBSVM | 0.798 | 0.798 |

| DistilBERT | 0.855 | 0.855 |

It can be noted from Table 6 that, the proposed method showed better performance than CNN, BiGRU, NBSVM, and fastText. Also, yielded slightly better performance than DistilBERT. This is promising as DistilBERT is a state-of-the-art method which is widely used in many text mining applications [58].

The normalized number of corona-related searches and the daily percentage of positive and negative sentiments in 8 different countries from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23 are discussed in the following subsections.

4.1. China

The graph of a normalized number of corona-related keywords (see Table 1) searches versus the time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) in China is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Graph of normalized number of keyword searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) in China.

As shown in Fig. 4, the number of searches from 2020-01-24 to 2020-02-21 is less than the rest of the time frame. This may be explained by considering the total number of cases and total deaths chart for China, as shown in Fig. 5. As can be seen in the figure, from 2020-02-21 the total number of cases remained almost constant and the number of deaths has reached a new steady state. This has led to more people paying attention to corona-related topics.

Fig. 5.

Total number of: (a) coronavirus cases, and (b) deaths in China.

The overall trend of positive and negative sentiment toward the corona-related keywords for China is shown in Fig. 6. As shown in this figure, the lowest negative sentiment is about 35% of the maximum on 2020-03-08 while the highest is about 70% of the maximum on 2020-03-28. Most of the positive days are from 2020-02-28 to 2020-03-08. This interval is a special time frame with respect to the number of recoveries. As shown in Fig. 7, the highest number of recoveries occurred during this period.

Fig. 6.

Frequency of positive and negative sentiments in tweets for China from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23.

Fig. 7.

Number of newly infected cases vs. number of recovered patients each day in China.

4.2. Italy

The graph of normalized number of the corona-related keyword (see Table 1) searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) for Italy is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Graph of normalized number of keyword searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) in Italy.

Similar to China, a sudden growth in the number of searches occurred from 2020-02-21 for Italy. This may be due to two reasons; First, searches are influenced by global statistics. Second, as shown in Fig. 9, new patients in Italy have been reported since 2020-02-21.

Fig. 9.

Number of daily new cases in Italy.

The overall trend of positive and negative sentiment toward the corona-related keywords for Italy is shown in Fig. 10. It can be seen that the amount of negative sentiment in Italy is higher than China (the maximum of negative sentiment is about 75% and the minimum is about 55%). This may be due to the fact that China is the first country to experience COVID-19 and the reaction of people in social media especially on Twitter to this virus is less affected by the global news. Hence, less negative news affected the people who tweeted about COVID-19.

Fig. 10.

Frequency of positive and negative sentiments in tweets for Italy from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23.

4.3. England

The graph of normalized number of corona-related keywords (see Table 1) searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) for England is shown in Fig. 11. As shown in the figure, the major growth in the number of corona related searches occurred in 2020-03-10 which is 20 days later than similar change for Italy and China. This may be the result of observing the first patients in 2020-03-10 for England (see Fig. 12).

Fig. 11.

Graph of normalized number of keyword searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) in England.

Fig. 12.

Number of daily new cases in England.

The overall trend of positive and negative sentiment towards the corona-related keywords for England is shown in Fig. 13. In England, between 12th March to the end of March, the percentage of negative sentiments is high compared to other days and remained almost constant during this time period. However, a small fall is seen on 5th April and a jump is observed after this which may be due to the increase in the number of deaths in England in this period.

Fig. 13.

Frequency of positive and negative sentiments in tweets for England from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23.

4.4. United States

The graph of normalized number of corona-related keywords (see Table 1) searches for the United States is shown in Fig. 14. As shown in the figure, there is a steady increase in the number of searches from 2020-03-10 which may be due to new cases (see Fig. 15).

Fig. 14.

Graph of normalized number of keyword searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) in the United States.

Fig. 15.

Number of daily new cases in the United States.

The overall trend of positive and negative sentiments towards the corona-related keywords for US is shown in Fig. 16. A relatively constant trend is observed in the US during this study period. This may be due to spread of new cases in the US compared to the countries analyzed in previous sections. The percentage of negative tweets started increase from March 12th due to the rise of new cases in the US. The negative rate is high for the following two weeks and remained stable. The peak in the US occurred on 27th March, which is close to 0.58. This is the start of sharp increase in the number of total cases and total deaths in the US as shown in Fig. 17.

Fig. 16.

Frequency of positive and negative sentiments in tweets for USA from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23.

Fig. 17.

Graph of total number of: (a) coronavirus cases and (b) deaths in the USA.

4.5. Canada

The graph of normalized number of corona-related keywords (see Table 1) searches versus time period (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) for Canada is shown in Fig. 18. As displayed in the figure, most of the searches started from 2020-03-11 which is the starting point of new cases as shown in Fig. 19. The peak of the chart in Fig. 19 is at 2020-03-18 which corresponds to the start of a more increased rate in newly infected patients is shown in Fig. 20.

Fig. 18.

Graph of normalized number of keyword searches versus time period (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) in Canada.

Fig. 19.

Number of daily new cases in Canada.

Fig. 20.

Number of newly infected cases vs. number of recovered patients each day in Canada.

A very similar trend to the US is seen in Canada (see Fig. 21). The percentage of negative tweets remained high for approximately two weeks with a peak of 0.68 on 27th March. However, compared to the US, the valley point of negative sentiment is relatively lower for Canada which is about 0.35. This occurred in the first few days of the time frame and may be due to few numbers of reported cases in those days.

Fig. 21.

Frequency of positive and negative sentiments in tweets for Canada from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23.

4.6. Australia

The graph of normalized number of corona-related keyword (see Table 1) searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) for Australia is shown in Fig. 22. As shown in the figure, the time frame may be divided into two parts. The first part is from the beginning of the time frame to 2020-03-02 corresponding to the first part of Fig. 23 during which the number of daily new cases is almost zero. The second part begins from 2020-03-02 which continues till the end of the time frame.

Fig. 22.

Graph of normalized number keyword searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) for Australia.

Fig. 23.

Graph of new corona virus daily cases versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) in Australia.

The overall trend of positive and negative sentiment toward the corona-related keywords for Australia is shown in Fig. 24. The trend in Australia is very similar to other aforementioned countries except for Italy. An upward trend started on 12th March and remained high for the next two weeks. The highest percentage of negative tweets is about 0.63 happened on 30th March. This percentage dropped to its lowest point on 8th March. The other critical factor that affected results is the number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths in these countries shot-up from 12th March.

Fig. 24.

Frequency of positive and negative sentiments in tweets for Australia from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23.

4.7. Iran

The graph of a normalized number of corona-related keywords versus time duration from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) for Iran (see Table 1) is presented in Fig. 25. As illustrated in the figure, the normalized number of searches during the period 2020-01-24 to 2020-02-19 is less than the rest of the time frame. This is due to the fact that the first case is observed in 2020-02-19 and submitted searches in previous dates are provided to get the general information about the new COVID-19 disease.

Fig. 25.

Graph of normalized coronavirus keyword searches versus various dates (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) for Iran.

The overall trend of positive and negative sentiment toward the corona-related keywords for Iran is shown in Fig. 26. In contrast to most of the aforementioned countries, the negative sentiment for Iran is not constant and fluctuates from 25% to 80%. This can be explained by observing the fluctuation in the number of newly infected cases versus the number of recovered and discharged patients, as shown in Fig. 27.

Fig. 26.

Frequency of positive and negative sentiments in tweets for Iran from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23.

Fig. 27.

Graph of a number of newly infected cases versus number of recovered patients each day in Iran.

The maximum negative sentiment for Iran is on 2020-04-02 which corresponds to the maximum number of active cases (see Fig. 28).

Fig. 28.

Graph of total number of Corona infected versus time duration in Iran.

4.8. Spain

The normalized number of corona-related keywords (see Table 1) searches for Spain is shown in Fig. 29. As shown in the figure, the number of searches has increased from 2020-02-20. This is similar to China, Italy, and Iran and maybe due to international news about COVID-19. In 2020-03-08, we observed a sharp increase in the number of searches. As shown in Fig. 30, the number of total cases (674 on 2020-03-08 and 1231 on 2020-03-09) and total deaths (17 on 2020-03-08 and 30 on 2020-03-09) have increased during this period.

Fig. 29.

Graph of normalized keyword searches versus time duration (from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23) for Spain.

Fig. 30.

Graph of total number of: (a) coronavirus cases, (b) deaths in Spain.

The overall trend of positive and negative sentiment towards the corona-related keywords for Spain is shown in Fig. 31.

Fig. 31.

Frequency of positive and negative sentiments in tweets for Spain from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23.

As shown in the figure, the minimum negative sentiment values (about 40%) are observed from 2020-02-28 to 2020-03-09. This time period corresponds to the valley point of charts in Fig. 30. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 32, new cases and new recoveries are reported after this time period. The maximum negative sentiment values are seen around 2020-03-20 when new cases started as shown in Fig. 32.

Fig. 32.

Graph of number of newly infected cases versus the number of recovered patients on each day in Spain.

5. Discussions

This section discusses the results obtained in eight countries (Sections 4.1 to 4.8) and summarized the answers to the research questions listed in Section 1.

The availability of abundant textual data from different online sources can be utilized to better recognize the growth, nature, and spread of COVID-19. As discussed in the previous section (see Section 3), we leveraged the tweets of users from eight countries who have been seriously impacted by COVID19 to explore their positive or negative opinions about the disease. In this study, the positive tweets show that the users are somewhat optimistic about the disease, while negative tweets mean that they are worried or disappointed about the impacts it might have on their life. The reaction and opinion of people about COVID-19 depend on various factors like socioeconomic, health condition, the economy of their country, culture, etc. which are beyond the scope of this study and will be discussed in our future work. However, few obvious differences are observed in the sentiment of tweets obtained from the eight countries. For example, in Iran, China, and Canada more positive tweets are observed, while in Italy and Spain more negative tweets are prevailing. Another difference is observed between English and non-English speaking countries. There is less fluctuation in the percent of tweets’ sentiments in English-speaking countries.

While answering the first research question, one can see the difference in the intensities of sentiments of Twitter users about coronavirus-related tweets in eight countries (Fig. 6, Fig. 10, Fig. 13, Fig. 16, Fig. 21, Fig. 24, Fig. 26, Fig. 31). Overall, it may be noted that the increase in positive sentiment correlates with the increase in the number of recoveries. However, the percent of positive tweets differ in different countries. For example, the most positive tweets belong to Iran, China, and Canada (80%, 65%, and 65%) while the most negative tweets belong to Iran, Italy, and Spain (80%, 75%, and 75%, respectively). For English speaking countries, there is less fluctuations in the percent of tweets’ sentiments. This may be due to the fact that the words are chosen more accurately by the users in those countries, while non-English users unintentionally may have used the sentiment words incorrectly to express in their tweets. Therefore, different sentiment pattern exists in different countries and hence there is a meaningful difference in English and non-English speaking countries.

While answering the second research question, one can see a correlation between the number of newly infected cases, new recoveries, and deaths with tweets’ sentiment in different dates and countries, in addition to the figures mentioned (Fig. 7, Fig. 9, Fig. 12, Fig. 15, Fig. 19, Fig. 20, Fig. 23, Fig. 27, Fig. 28, Fig. 30, Fig. 32). As shown in these figures, the maximum negative sentiment values are seen either around the rise of new and active cases or the number of death charts. Similarly, the maximum positive sentiment values are obtained for time frames for which the highest number of recoveries occurred. This, answers the third research question conclusively.

Finally, to answer the last research question which addresses the performance of different models, the collected coronavirus-related dataset has no gold-standard labels and hence cannot be used to assess the performance of the models. Therefore, as stated in Section 3.2, a large-scale Twitter dataset containing 1.6 million tweets is used. As shown in Table 6, the performance of the proposed model is better than four other deep models described in Sections 3.3.1 to 3.3.5 and slightly better than DistilBERT which is a state-of-the-art model for many text mining applications [58]. Hence, our proposed model has performed better than the state-of-the-art techniques for Twitter sentiment analysis and hence, can be used to accurately classify the coronavirus Twitter dataset collected for sentient analysis of users’ tweets in eight countries in this study.

The results of this study can be used for governors, social policymakers, and healthcare managers to better understand the effect of COVID-19 on the overall sentiment of society. This may be used to design better strategies for improving public mood during different phases of pandemic. For example, when the increasing trend is detected in the active cases chart or number of death chart, the social policymakers can devise suitable policies and decisions to control the public sentiment and decrease the effects of a pandemic on the emotions of society. Another application of the obtained results of the current study is to use similar trend occurred in other countries to predict the effect of changes in the COVID-19 charts on the sentiment charts. In addition to these applications, researchers can use the results of the current study to compare the public mood of different countries during the pandemic. This may be of concerns for social scientists as well as global healthcare agencies.

6. Conclusion

The coronavirus or COVID-19 disease is one of the biggest human challenges of the last few decades. All governments and researchers are relentlessly trying to reduce the deadly effects of this pervasive disease. This study is conducted to find the general sentiment (opinion) of people in eight countries around the world. To do so, we collected the tweets from those eight countries between 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-21 and also Google Trends users by using coronavirus-related keyword searches from 2020-01-24 to 2020-04-23. For sentiment analysis, we proposed a new hybrid fusion model using five deep classifiers and then combined them to improve the final output using a meta learning method. To assess the performance of the proposed method for Twitter sentiment analysis, we evaluated all five base models and proposed model using Stanford Sentiment140 Twitter dataset with 1600,000 labeled tweets. Our findings show that the proposed fusion models can classify the sentiments with promising performance and can be used to analyze the collected coronavirus-related dataset accurately. Three main observations of this study are: (i) rise in information about coronavirus is correlated with the reported first infected case, (ii) every country has unique sentiment patterns, (iii) maximum negative sentiment values happened either around the rise of new and active cases or a number of death charts. Similarly, the highest number of recoveries happened during the time period of maximum positive sentiment values. In addition to these findings, the results show that different sentiment pattern exists in different countries and it may be concluded that there are meaningful differences in English and non-English speaking countries. We hope that these findings will have a significant impact on controlling the disease. The limitation of our study is ignoring the effects of global COVID-19 news and statistics on the overall sentiment of other countries. Another limitation is the keyword selection for information seeking and filtering tweets are independent of the country for which we are extracting the dataset. In future, this work can be extended by focusing on the tweets published by special communities or target societies to find its impact on the public sentiment and mood.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohammad Ehsan Basiri: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing - original draft. Shahla Nemati: Conceptualization, Methodology. Moloud Abdar: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Somayeh Asadi: Writing - original draft, Investigation. U. Rajendra Acharrya: Supervision, Validation, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

References

- 1.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 2.Lyócsa Štefan, Baumohl Eduard, Výrost Tomáš, Molnár Peter. Fear of the coronavirus and the stock markets. Finance Res. Lett. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holshue Michelle L., Chas DeBolt, Scott Lindquist, Lofy Kathy H., John Wiesman, Hollianne Bruce, Christopher Spitters, et al. First case of novel coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;382(2020):929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perlman Stanley. Another decade, another coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020:760–762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/an-instant-economic-crisis-how-deep-and-how-long.

- 6.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/how-to-restart-national-economies-during-the-coronavirus-crisis.

- 7.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/coronavirus-and-the-campus-how-can-us-higher-education-organize-to-respond.

- 8.Yun Qiu, Chen Xi, Shi Wei. Impacts of social and economic factors on the transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J. Popul. Econ. 2019;33:1127–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karishma Sharma, Seo Sungyong, Meng Chuizheng, Rambhatla Sirisha, Liu Yan. 2020. COVID-19 on social media: Analyzing misinformation in Twitter conversations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.12309. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merchant Raina M., Lurie Nicole. Social media and emergency preparedness in response to novel coronavirus. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2011–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doulamis Nikolaos D., Doulamis Anastasios D., Kokkinos Panagiotis. Event detection in twitter microblogging. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2015;46(12):2810–2824. doi: 10.1109/TCYB.2015.2489841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farzindar Atefeh, Khreich Wael. A survey of techniques for event detection in twitter. Comput. Intell. 2015;31(1):132–164. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zafar Saeed, Abbasi Rabeeh Ayaz, Maqbool Onaiza, Sadaf Abida, Razzak Imran, Daud Ali, Aljohani Naif Radi, Xu Guandong. What’s happening around the world? A survey and framework on event detection techniques on Twitter. J. Grid Comput. 2019;17(2):279–312. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basiri Mohammad Ehsan, Abdar Moloud, Cifci Mehmet Akif, Nemati Shahla, Rajendra Acharya U. A novel method for sentiment classification of drug reviews using fusion of deep and machine learning techniques. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020;198 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahla Nemati. 2018 9th International Symposium on Telecommunications, IST. IEEE; 2018. Canonical correlation analysis for data fusion in multimodal emotion recognition; pp. 676–681. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahla Nemati. 2019 5th International Conference on Web Research, ICWR. IEEE; 2019. OWA operators for the fusion of social networks’ comments with audio-visual content; pp. 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amir Zadeh, Chen Minghai, Poria Soujanya, Cambria Erik, Morency Louis-Philippe. Proceedings of 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP. ACL; 2017. Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis; pp. 1114–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannathal N., Rajendra Acharya U., Ng E.Y.K., Krishnan S.M., Min Lim Choo, Laxminarayan Swamy. Cardiac health diagnosis using data fusion of cardiovascular and haemodynamic signals. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2006;82(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raghavendra U., Rajendra Acharya U., Gudigar Anjan, Tan Jen Hong, Fujita Hamido, Hagiwara Yuki, Molinari Filippo, Pailin Kongmebhol U., Ng Kwan Hoong. Fusion of spatial gray level dependency and fractal texture features for the characterization of thyroid lesions. Ultrasonics. 2017;77:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Bangren, Zheng Xinqi, Liu Haiyan, Li Jiayang, Wang Peipei. Analysis of spatiotemporal characteristics of big data on social media sentiment with COVID-19 epidemic topics. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;140 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Yuxin, Xu Huilan. Chinese public attention to COVID-19 epidemic: Based on social media. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(5) doi: 10.2196/18825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jawad Saleemi. COVID-19 outbreak, correlating the cost-based market liquidity risk to microblogging sentiment indicators. Nat. Account. Rev. 2020;2(3):249–262. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gopalkrishna Barkur, Kamath Vibha Giridhar B. Sentiment analysis of nationwide lockdown due to COVID 19 outbreak: Evidence from India. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xueting Wang, Zou Canruo, Xie Zidian, Li Dongmei. 2020. Public opinions towards covid-19 in california and new york on twitter. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Long, Lyu Hanjia, Yang Tongyu, Wang Yu, Luo Jiebo. 2020. In the eyes of the beholder: Sentiment and topic analyses on social media use of neutral and controversial terms for covid-19. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10225. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamed Jelodar, Wang Yongli, Orji Rita, Huang Hucheng. Deep sentiment classification and topic discovery on novel coronavirus or covid-19 online discussions: Nlp using lstm recurrent neural network approach. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 2020;24(10):2733–2742. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2020.3001216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cambria Erik, Schuller Björn, Xia Yunqing, Havasi Catherine. New avenues in opinion mining and sentiment analysis. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2013;28(2):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cambria Erik. Affective computing and sentiment analysis. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2016;31(2):102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2017. A Practical Guide To Sentiment Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basiri Mohammad Ehsan, Kabiri Arman. Words are important: improving sentiment analysis in the Persian language by lexicon refining. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inform. Process. 2018;17(4):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basiri Mohammad Ehsan, Kabiri Arman. 2017 International Symposium on Computer Science and Software Engineering Conference (CSSE) IEEE; 2017. Translation is not enough: comparing lexicon-based methods for sentiment analysis in Persian; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su Yi-Jen, Hu Wu-Chih, Jiang Ji-Han, Su Ruei-Ye. A novel LMAEB-CNN model for chinese microblog sentiment analysis. J. Supercomput. 2020:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oueslati Oumaima, Cambria Erik, HajHmida Moez Ben, Ounelli Habib. A review of sentiment analysis research in Arabic language. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020;112:408–430. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basiri Mohammad Ehsan, Nasser Ghasem-Aghaee, Reza Ahmad. Lexicon-based sentiment analysis in Persian. Curr. Future Develop. Artif. Intell. 2017;30:154–183. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chauhan Ummara Ahmed, Afzal Muhammad Tanvir, Shahid Abdul, Abdar Moloud, Basiri Mohammad Ehsan, Zhou Xujuan. A comprehensive analysis of adverb types for mining user sentiments on amazon product reviews. World Wide Web. 2020:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fatemeh Fouladfar, Dehkordi Mohammad Naderi, Basiri Mohammad Ehsan. Predicting the helpfulness score of product reviews using an evidential score fusion method. IEEE Access. 2020;8:82662–82687. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemati Shahla, Rohani Reza, Basiri Mohammad Ehsan, Abdar Moloud, Yen Neil Y., Makarenkov Vladimir. A hybrid latent space data fusion method for multimodal emotion recognition. IEEE Access. 2019;7 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruz G.A., Henríquez P.A., Mascareño A. Sentiment analysis of Twitter data during critical events through Bayesian networks classifiers. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020;106:92–104. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aparup Khatua, Khatua Apalak, Cambria Erik. A tale of two epidemics: Contextual Word2Vec for classifying twitter streams during outbreaks. Inf. Process. Manage. 2019;56(1):247–257. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassan S.U., Aljohani N.R., Idrees N., Sarwar R., Nawaz R., Martínez-Cámara E., Ventura S., Herrera F. Predicting literature’s early impact with sentiment analysis in Twitter. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020;192 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feizollah A., Ainin S., Anuar N.B., Abdullah N.A.B., Hazim M. Halal products on Twitter: Data extraction and sentiment analysis using stack of deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access. 2019;7:83354–83362. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghiassi M., Skinner J., Zimbra D. Twitter brand sentiment analysis: A hybrid system using n-gram analysis and dynamic artificial neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013;40(16):6266–6282. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ana Valdivia, Victoria Luzón M., Herrera Francisco. Sentiment analysis in tripadvisor. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2017;32(4):72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moloud Abdar, Basiri Mohammad Ehsan, Yin Junjun, Habibnezhad Mahmoud, Chi Guangqing, Nemati Shahla, Asadi Somayeh. Energy choices in Alaska: Mining people’s perception and attitudes from geotagged tweets. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020;124 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.109781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Lei, Niu Jianwei, Yu Shui. Sentidiff: Combining textual information and sentiment diffusion patterns for Twitter sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2019;32(10):2026–2039. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saad S.E., Yang J. Twitter Sentiment analysis based on ordinal regression. IEEE Access. 2019;7 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ebrahimi Monireh, Yazdavar Amir Hossein, Sheth Amit. Challenges of sentiment analysis for dynamic events. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2017;32(5):70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basiri Mohammad Ehsan, Nemati Shahla, Abdar Moloud, Cambria Erik, Rajendra Acharrya U. ABCDM: An attention-based bidirectional CNN-RNN deep model for sentiment analysis. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020;115:279–294. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Qifa, Bo Zhongpu, Jiang Cuixia, Liu Yezheng. Does google search index really help predicting stock market volatility? Evidence from a modified mixed data sampling model on volatility. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2019;166:170–185. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rill Sven, Reinel Dirk, Scheidt Jörg, Zicari Roberto V. Politwi: Early detection of emerging political topics on twitter and the impact on concept-level sentiment analysis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2014;69:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin Yu-Hsuan, Liu Chun-Hao, Chiu Yu-Chuan. Google searches for the keywords of wash hands predict the speed of national spread of COVID-19 outbreak among 21 countries. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:30–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao Y. Three-way decisions with probabilistic rough sets. Inform. Sci. 2010;180(3):341–353. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Sida, Manning Christopher D. Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Short Papers-Volume 2. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2012. Baselines and bigrams: Simple, good sentiment and topic classification; pp. 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cicero Dos Santos, Maira Gatti, Deep convolutional neural networks for sentiment analysis of short texts, in: Proceedings of COLING 2014, the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers, 2014, pp. 69-78.

- 55.Jabreel Mohammed, Hassan Fadi, Moreno Antonio. Advances in Hybridization of Intelligent Methods. Springer; Cham: 2018. Target-dependent sentiment analysis of tweets using bidirectional gated recurrent neural networks; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xia Yunqing, Cambria Erik, Hussain Amir, Zhao Huan. Word polarity disambiguation using bayesian model and opinion-level features. Cogn. Comput. 2015;7(3):369–380. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joulin Armand, Edouard Grave, Piotr Bojanowski, Tomas Mikolov, Bag of tricks for efficient text classification, in: Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, vol. 2, 2017, pp. 427—431.

- 58.Sanh Victor, Debut Lysandre, Chaumond Julien, Wolf Thomas. 2019. Distilbert a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, Kristina Toutanova, Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding, in: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, vol. 1, 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- 60.Sesmero M. Paz, Ledezma Agapito I., Sanchis Araceli. Generating ensembles of heterogeneous classifiers using stacked generalization. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Data Mining Knowl. Discov. 2015;5(1):21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yinhan Liu, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, Omer Levy, Mike Lewis, Luke Zettlemoyer, Veselin Stoyanov,

- 62.Akhtar Md Shad, Ekbal Asif, Cambria Erik. How intense are you? predicting intensities of emotions and sentiments using stacked ensemble. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2020;15(1):64–75. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma Zhiyuan, Wang Ping, Gao Zehui, Wang Ruobing, Khalighi Koroush. Ensemble of machine learning algorithms using the stacked generalization approach to estimate the warfarin dose. PLoS One. 2018;13(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tianqi Chen, Carlos Guestrin, Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system, in: Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016, pp. 785-794.

- 65.Stein Roger Alan, Jaques Patricia A., Valiati Joao Francisco. An analysis of hierarchical text classification using word embeddings. Inform. Sci. 2019;471:216–232. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Go Alec, Bhayani Richa, Huang Lei. CS224N Project Report, Stanford Vol. 1 (12) 2009. Twitter Sentiment classification using distant supervision; p. 2009. [Google Scholar]