Abstract

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, several federal, state, and payor policy changes have facilitated the uptake of telehealth service delivery. These changes have resulted in a significant uptick in the utilization of maternal mental health and substance use disorder screening and treatment services for pregnant and postpartum women. The Medical University of South Carolina's [MUSC] Women's Reproductive Behavioral Health Program provides outpatient mental health and substance use treatment to pregnant and postpartum women within obstetric practices. With the onset of COVID-19, our program converted all of its screening for and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders to remote platforms. Lessons learned during this time may lay the foundation for transitioning to sustainable telehealth-based referral and delivery of substance use treatment more broadly.

Keywords: COVID-19, Postpartum, Peripartum, Telehealth

1. Review of the topic

The rise in maternal morbidity and mortality in the U.S. has prompted increased attention to upstream factors influencing maternal health, including mental health and substance use disorders (Grodzinsky et al., 2019; Salameh & Hall, 2020; Walker, Arbour, & Wika, 2019; Wang, Glazer, Howell, & Janevic, 2020). The rate of opioid use disorder (OUD) has quadrupled among delivery hospitalizations over the past two decades (Haight, Ko, Tong, Bohm, & Callaghan, 2018). Throughout many areas of the U.S., pregnant women with OUD face limited access to comprehensive clinical services, including pharmacotherapy for OUD, such as buprenorphine, and behavioral health care (Ecker et al., 2019; Krans & Patrick, 2016). For example, a recent structured online national survey of obstetricians (n=565) assessed factors influencing treatment recommendations for pregnant women with OUD and found that the majority (77%) had provided care for a woman with OUD in the past year; however, only 14% or physicians were DATA-waivered to prescribe buprenorphine and less than half of waivered physicians reported actually prescribing buprenorphine in the past year (Howard & Freeman, 2020). Key barriers to OUD treatment among pregnant and postpartum women include an insufficient number of specialized or DATA-waivered providers, delays in referral and care connection, stigma and criminalization, lack of transportation, and inability to cover cost of services (Frazer, McConnell, & Jansson, 2019; Kroelinger et al., 2019; Sutter, Gopman, & Leeman, 2017).

Another major barrier has traditionally been the requirement that the first visit with a provider be conducted in-person. This regulation was enacted in 2009 by the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Intended as a way to control Internet pharmacies, it also inadvertently placed wholesale restrictions on telemedicine. The “practice of telemedicine” exceptions are narrow, highly technical, and have not evolved with the practice of telemedicine that have increased exponentially since Congress passed the Ryan Haight Act. In February 2018, Congress announced the Improving Access to Remote Behavioral Health Treatment Act and companion bill, the Special Registration for Telemedicine Clarification Act, that allow mental health and addiction treatment centers to obtain DEA registration as a clinic, thereby making it possible for telemedicine providers to prescribe controlled substances to patients without the need for an in-person visit. While these recommendations have been made, the DEA has not released details about this bill. Thus, given that telehealth treatment provides a promising avenue to address many barriers in service provision for pregnant and postpartum women with OUD (Guille et al., 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic may provide a unique opportunity to demonstrate the impact of temporary provisions and move these bills forward to ensure that programs like the one described here are sustained.

2. Current state of services

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, several federal, state, and payor policy changes have been enacted to facilitate the uptake of telehealth service delivery in general, as well as among women with OUD in particular (ASAM, 2020; DEA, 2020; SAMHSA, 2020). Key changes include: (1) waivers of regulatory requirements for use of HIPPA compliant telehealth platforms; (2) expansion of Medicaid coverage for telehealth services; (3) allowing issuance of controlled substance via telemedicine without conducting the initial in-person evaluation; and (4) easing restrictions around take-home medications that opioid treatment programs issue.

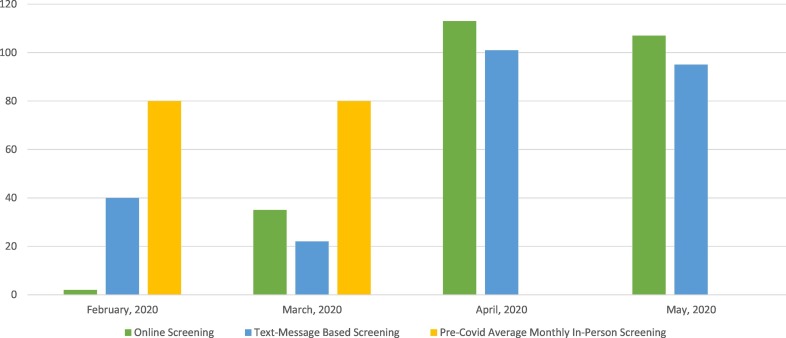

These changes have resulted in a significant uptick in the utilization of maternal mental health and substance use disorder screening and treatment services for pregnant and postpartum women. The Medical University of South Carolina's [MUSC] Women's Reproductive Behavioral Health Program provides outpatient mental health and substance use treatment to pregnant and postpartum women within obstetric practices. With the onset of COVID-19, our program converted all of its screening for and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders to remote platforms. Specifically, peripartum women seeking or referred to mental health or substance use disorder services complete either a brief online screening or text-message-based screening. Following the screening, a care coordinator contacts the patient within 24-h (Monday–Friday, 8 AM-5 PM) by phone. The care coordinator further assesses the patient's mental health and/or substance use disorder treatment needs, and, if appropriate, schedules the patient for a home-based telehealth visit with a specialist in reproductive psychiatry. Research indicates that 96% of Americans own a cellphone and 80% own a smartphone, with comparable rates reported for minority individuals (e.g., African Americans 98% and 80%; Hispanics/Latinx 96% and 79%, respectively) and those in rural areas (95% and 71%) (Pew Research Center, 2020). However, if the patient does not have access to a device to use for telehealth services, or does not have access to Internet, the care coordinator works with the patient to either loan a device or find a solution to prevent lack of technology from becoming a barrier to treatment access. Following the onset of COVID-19 there was a sharp increase in our program's online and text-message-based screening services (Fig. 1 ). Similarly, following the onset of COVID-19, the average monthly utilization of telehealth services increased by 90%.

Fig. 1.

Online and text message-based maternal mental health and substance use disorder screenings prior to and during COVID-19.

Given the heightened prevalence of interpersonal violence (IPV) among peripartum women referred to mental health or substance use disorder services (Pallatino, Chang, & Krans, 2019), clinicians must incorporate screening and safety measures to protect this population. Thus, the text-message-based screening services incorporate assessment for interpersonal violence in discrete text message to ensure privacy. If women report IPV or safety risk during the assessment, the providers work with the patient to coordinate and offer in-person services at the clinic or to receive telehealth in the car outside of the home, or in another safe and private place where she can access Wi-Fi (e.g., library). Given the need for integrated IPV services within primary care clinics (Weaver et al., 2015), we continue to improve services to assess and refer to treatments to ensure the safety of patients, which is especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic when women are more isolated than is typical.

3. Impact on future service delivery

Although the recent increase in telehealth for OUD treatment occurred in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, this initial transition to telehealth-based screening, referral, and service delivery for women with OUD is promising and may provide an opportunity to address longstanding barriers to treatment. Specifically, when the COVID-19 pandemic ends and we resume services as usual, implementing a combination of virtual referral and telehealth delivery for women with OUD may mitigate commonly identified barriers to treatment, including transportation, time, childcare, and stigma (Frazer et al., 2019). Thus, the changes enacted to allow for feasible service-delivery during the pandemic have actually provided an opportunity to expand telehealth services for peripartum and postpartum women that typically would not have received services in pre-pandemic times. Reaching women during the peripartum and postpartum period is essential, given that the likelihood of relapse is extremely high during the postpartum period and that Medicaid coverage only spans through 90-days postpartum. Thus, engaging women during this critical relapse window, while they have insurance coverage, is essential.

In conclusion, policy changes that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic have allowed a unique opportunity to address multiple barriers to service provision among peripartum and postpartum women to allow for feasible telehealth screening and service delivery. Lessons learned during this time, as well as safety data to address concerns regarding effects of waiving initial in-person patient visit and easing take-home prescription regulations, may lay the foundation for transitioning to sustainable telehealth-based referral and delivery of substance use treatment more broadly.

Funding

This study was supported by NIDA R34 DA046730 to support the first author.

References

- American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). (2020). Supporting access to telehealth for addiction services: Regulatory overview and general practice considerations. Accessed May 20, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.asam.org/Quality-Science/covid-19-coronavirus/access-to-telehealth.

- Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). (2020). DEA SAMHSA buprenorphine telemedicine. March 2020. Accessed May 11, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-022)(DEA068)%20DEA%20SAMHSA%20buprenorphine%20telemedicine%20%20(Final)%20+Esign.pdf.

- Ecker J, Abuhamad A, Hill W, Bailit J, Bateman BT, Berghella V, Blake-Lamb T, Guille C, Landau R, Minkoff H, Prabhu M, Rosenthal E, Terplan M, Wright TE, Yonkers KA. (2019). Substance use disorders in pregnancy: Clinical, ethical, and research imperatives of the opioid epidemic: A report of a joint workshop of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American Society of Addiction Medicine. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 221(1), B5-B28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.022. PubMed PMID: 30928567. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Frazer Z., McConnell K., Jansson L.M. Treatment for substance use disorders in pregnant women: Motivators and barriers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019;205 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107652. 31704383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinsky A., Florio K., Spertus J.A., Daming T., Schmidt L., Lee J.…Magalski A. Maternal mortality in the United States and the HOPE registry. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2019;21(9) doi: 10.1007/s11936-019-0745-0. 31342274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guille C., Simpson A., Douglas E., Boyars L., Cristaldi K., McElligott J., Johnson D., Brady K. (2020) Treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnant women via telemedicine. JAMA Network Open, 3(1). https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamanetworkopen.2019.20177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, Callaghan WM. (2018). Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization - United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(31), 845–849. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6731a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Howard H.G., Freeman K. U.S. survey of factors associated with adherence to standard of care in treating pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020;41(1):74–81. doi: 10.1080/0167482x.2019.1634048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krans E.E., Patrick S.W. Opioid use disorder in pregnancy: Health policy and practice in the midst of an epidemic. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;128(1):4–10. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000001446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroelinger CD, Rice ME, Cox S, Hickner HR, Weber MK, Romero L, Ko JY, Addison D, Mueller T, Shapiro-Mendoza C, Fehrenbach SN, Honein MA, Barfield WD. (2019). State strategies to address opioid use disorder among pregnant and postpartum women and infants prenatally exposed to substances, including infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(36), 777–783. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6836a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pallatino C., Chang J.C., Krans E.E. The intersection of intimate partner violence and substance use among women with opioid use disorder. Substance abuse. 2019;1(8) doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1671296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center . 2020. Mobile Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ [Google Scholar]

- Salameh T.N., Hall L.A. Depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders and treatment receipt among pregnant women in the United States: A systematic review of trend and population-based studies. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2020;41(1):7–23. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2019.1667460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2020). FAQs: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. Accessed May 11, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing-and-dispensing.pdf.

- Sutter M.B., Gopman S., Leeman L. Patient-centered care to address barriers for pregnant women with opioid dependence. Obstetrics & Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2017;44(1):95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K.C., Arbour M.W., Wika J.C. Consolidation of guidelines of postpartum care recommendations to address maternal morbidity and mortality. Nursing for Women’s Health. 2019;23(6):508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E., Glazer K.B., Howell E.A., Janevic T.M. Social determinants of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity in the United States: A systematic review. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020;135(4):896–915. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver T.L., Gilbert L., El-Bassel N., Resnick H.S., Noursi S. Identifying and intervening with substance-using women exposed to intimate partner violence: phenomenology, comorbidities, and integrated approaches within primary care and other agency settings. Journal of Women's Health. 2015;24(1):51–56. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]