Abstract

Education institutions are expected to contribute to the development of students' critical thinking skills. Due to COVID-19, there has been a surge in interest in online teaching. The aim of this study is therefore to design a strategy to promote critical thinking in an online setting for first year undergraduates. An intervention was carried out with 834 students at an engineering school; it comprised five activities designed to develop critical thinking. Both the control and experimental groups worked with a project-based learning strategy, while the experimental group was provided with scaffolding for a socially shared regulation process. All students answered an identical pre- and post-test so as to analyze the impact on critical thinking. Both strategies performed significantly better on the post-test, suggesting that online project-based learning improves critical thinking. However, following a socially shared regulation scaffolding led to a significantly greater improvement. In this sense, the socially shared regulation scaffolding provided to the experimental group proved to be key, while feedback was also an important element in the development of critical thinking. This study shows that online project-based learning fosters the development of critical thinking, while providing a socially shared regulation scaffolding also has a significant impact.

Keywords: Critical thinking, Project-based online learning, Socially shared regulation, Instructional design, Collaborative learning

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has challenged education systems and made us rethink how we teach, forcing us to adopt remote learning and teaching methodologies. In an online teaching environment, critical thinking is one skill that remains relatively unstudied (Saadé et al., 2012). Even though the number of studies has increased, they are still rarely cited (Chou et al., 2019).

In 1990, the American Philosophical Association stated that critical thinking “is essential as a tool of inquiry, and a liberating force in education and a powerful resource in one's personal and civic life.” They defined a critical thinker as someone who is analytical and knowledgeable, willing to challenge information, investigate, and seek rigorous results; someone who understands who they are, understands their biases, and is likely to rethink and reconsider. They consider critical thinking to be the foundation of a democratic society (Facione, 1990).

Today, we live in a rapidly changing society immersed in a knowledge economy (van Laar et al., 2017), where the internet has become people's main source of information (Saadé et al., 2012). As the effects of fake news have become a major issue, media literacy and critical thinking have emerged as essential skills (; Scheibenzuber et al., 2021). Employers expect employees to discriminate between information that is useful and information that is not, as well as implementing newly acquired knowledge (van Laar et al., 2017). Critical thinking is therefore key as it allows us to understand information and determine whether it is reliable, regardless of the domain (Saadé et al., 2012). This involves independent thinking and the ability to formulate opinions after considering different perspectives (van Laar et al., 2019). In summary, it is a higher-order thinking skill that involves problem-solving, decision-making, and creative thinking (Facione, 1990).

In this context, education institutions are expected to contribute to the development of their students' critical thinking skills (Thorndahl & Stentoft, 2020). In other words, they should teach students how to think and not what to think (Velez & Power, 2020). Learning how to think, through the development of critical thinking, should therefore be encouraged from the first year of university (Thomas, 2011). First-year courses should promote critical thinking by making it explicit and having students reflect on their learning processes (Thomas et al., 2007). By doing so, students will be more successful in their university studies and have more time to practice and develop their critical thinking skills before they graduate (Thomas, 2011).

Project-based learning is one educational methodology that improves communication skills and promotes critical thinking (Wengrowicz et al., 2017). It promotes learning based on real-life projects (Dilekli, 2020, p. p53), while motivating students; helping improve their problem-solving and argumentation skills, and encouraging them to broaden their minds (Velez & Power, 2020). This involves working autonomously in teams to tackle open-ended problems, from the research phase through to developing a final product (Usher & Barak, 2018), thus boosting their intellectual development (Wengrowicz et al., 2017). Project-based learning enhances collaboration (McManus & Costello, 2019), allowing students not only to learn from themselves but also from each other (Hernández et al., 2018). Students who participate collaboratively do significantly better on critical thinking tests than those who work independently (Erdogan, 2019; Silva et al., 2019; and; Gokhale, 1995). Therefore, implementing collaborative learning and providing adequate instructions may help students develop critical thinking (Loes & Pascarella, 2017).

Previous studies of online project-based learning have mainly focused on how students collaborate; only a few studies examine the methodologies used to help students acquire knowledge (Koh et al., 2010). Furthermore, digital technology has allowed education systems to move from a physical to an online environment (Saadé et al., 2012). While presenting a challenge to the field of education, it can also help students acquire the skills that are essential for modern life (Sailer et al., 2021). Recent studies have highlighted the challenges of teaching critical thinking online. This includes facilitating social interactions (Wan Husssin et al., 2019), maintaining quality when taking a course online (Goodsett, 2020), and designing effective feedback (Karaoglan & Yilmaz, 2019). Additionally, critical thinking has important effects on student performance in online activities, especially when it comes to the correct use of information (Jolley et al., 2020) and engaging in higher-order thinking (Al-Husban, 2020).

Developing critical thinking in an online environment requires the interplay between content, interactivity, and instructional design (Saadé et al., 2012). In this sense, traditional teaching methods are less effective at developing critical thinking (Chou et al., 2019). When working with ill-structured problems in an online, project-based learning environment (Şendaǧ & Odabaşi, 2009), effective student interaction leads to higher levels of knowledge construction (Koh et al., 2010). Project- and problem-based courses foster a student's ability to take positions and make decisions, both of which are essential to critical thinking (Bezanilla et al., 2019). Furthermore, the most common approach to enhancing critical thinking is through online synchronous or asynchronous discussions (Chou et al., 2019). Through online discussions, students can share and contrast knowledge, engage in discussions and debates, and sustain group motivation (Afify, 2019). More research into how online, project-based and problem-based learning affects the development of critical thinking is therefore encouraged (Foo & Quek, 2019).

In terms of instructional design, the extent to which critical thinking skills are developed online depends on the scaffolding that is provided (Giacumo & Savenye, 2020; Hussin et al., 2018). Structured interaction is essential for promoting critical thinking and knowledge construction in online teaching (He et al., 2014). Although there is a general consensus that critical thinking can be promoted by designing specific instructional strategies (Butler et al., 2017), little is known about how teachers promote critical thinking in their classrooms (Cáceres et al., 2020). There is therefore a need for more instructional strategies that specifically aim to promote critical thinking skills (Butler et al., 2017), especially in an online setting.

Considering the above, our research question asks: How can we develop critical thinking among first-year undergraduates in an online setting?

2. Method

2.1. Research context

Every year, around 800 first-year undergraduate students enroll in Engineering Challenges, a cornerstone course implemented by the Engineering School at a university in Chile. Cornerstone courses are engineering design courses that provide first-year students with an initial introduction to the skills they need for solving real-world problems (Dringenberg & Purzer, 2018). One of the most efficient ways of teaching design is by letting the students become active participants in the design process, which is best achieved through project-based learning (Dym et al., 2005). Furthermore, project-based learning provides substantial support for the teaching and learning of science and engineering (Usher & Barak, 2018), while also being an excellent way of introducing students to the life of an Engineer (Lantada et al., 2013). Because of this, cornerstone courses are usually taught through project-based learning, which promotes critical thinking and provides students with a space to express their views (Wengrowicz et al., 2017).

This cornerstone course was chosen as a case study as it is a required course and had a relatively high number of participants (see the course summary in Appendix A). The total number of students enrolled in 2020 was 834. Students were divided into ten sections. Each section was randomly assigned to the experimental or control group. In engineering design courses with a project-based methodology, students usually work in teams of three to eight students (Chen et al., 2020). In this course, students were divided into teams of six or seven members. This was mainly because of methodological constraints, such as the time needed for the students' oral presentations, as well as resource constraints, such as the number of teaching assistants available.

Classroom diversity encourages active thinking and intellectual engagement, which is beneficial for students and improves academic outcomes (Berthelon et al., 2019). At the same time, higher satisfaction and lower dropout rates have been associated with increased levels of perceived similarity (Shemla et al., 2014). Based on these criteria, the Office of Undergraduate Studies was tasked with choosing the teams. They separated students from the same high school and paired students belonging to minority subgroups: female students (30%), students who came from outside the Metropolitan Region (23%), and students who entered through alternative admissions programs (22%).

As a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, we were faced with the challenge of teaching this cornerstone course remotely. These students had never been to the university campus, never met each other face-to-face, and had to work from home without ever physically interacting with their peers or professors.

2.2. Research model and procedure

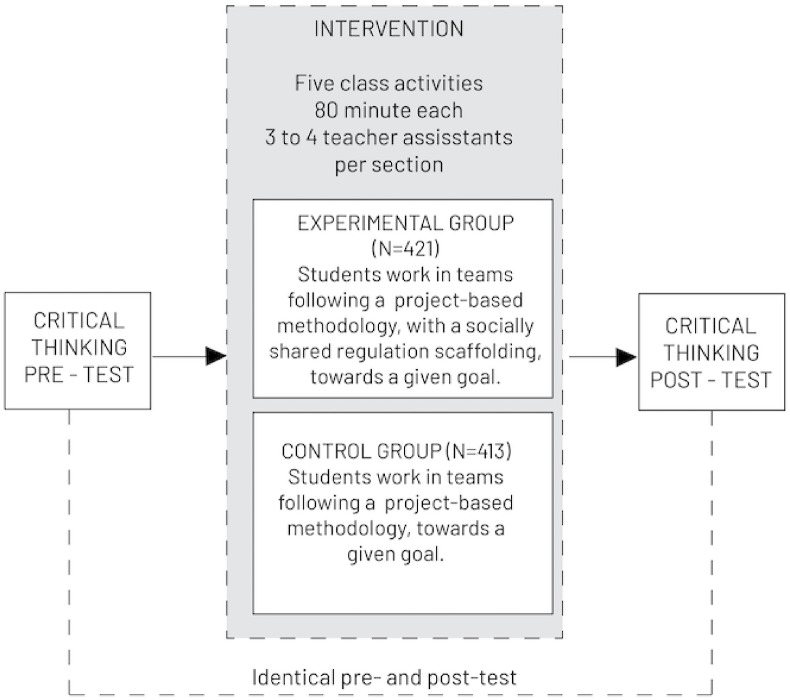

The research design for this study involved an intervention consisting of five class activities and a pre- and post-test designed to analyze the impact of the intervention on critical thinking, as shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Research design.

Students in both groups worked online with a project-based methodology following a design thinking process throughout the semester. Design thinking is understood as a design process where divergent and convergent thinking is perpetuated (Dym et al., 2005). It also involves the user throughout the whole design process as their feedback is seen as fundamental for solving most complex engineering problems (Coleman et al., 2020).

Students in both groups worked on five assignments individually during the semester (see Appendix B for an example of an individual assignment). Students completed a team-based activity after each individual assignment. During these collaborative sessions, an intervention was carried out. A teaching assistant explained the objective and deliverables for each activity to the students in the experimental and control groups. The students in both groups worked in teams using breakout rooms in Zoom. The students on each team had to use their individual assignment as input for the activity and were supported by the teaching assistant. After finishing the activity, each team had to upload the corresponding deliverable to Canvas. Both groups worked exclusively online. See Appendix C for a detailed explanation of each of the five activities completed by both groups (i.e. control and experimental).

Students in the control group worked in teams, with the same objective and deliverable as the experimental group. As the experimental group, teams in the control group were placed in breakout rooms in Zoom. Following a project-based methodology, the students in the control group worked freely in teams in order to achieve the objective and produce the deliverable while the teaching assistants answered questions and gave support to whoever needed it. Appendix D presents an example script for the third activity given to the students in the control group.

For students to develop and apply critical thinking skills to a new and unknown situation, they must acquire metacognitive skills (Thomas, 2011). While working in teams, socially shared regulation promotes metacognition when structure guidance exists (Kim & Lim, 2018). Malmberg et al. (2017) establish the following categories for a socially shared regulation process: (i) define the objective (i.e. task understanding), (ii) determine the relevant components of the task and how to accomplish them (i.e. planning), (iii) establish clear goals, (iv) monitor, and (v) evaluate progress in terms of timeframes and actions. The scaffolded activities were designed based on these categories (see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Implementing Malmberg et al.’s (2017) categories for socially shared regulation.

| Categories for a socially shared regulation process (Malmberg et al., 2017). | Implementing these categories in each activity during the intervention |

|---|---|

| Define the objective | The objective of the activity, i.e. what students should accomplish in terms of learning, was defined and communicated to the students (see the specific objective of each activity in the row: “Team Activity Objective” in Appendix C: Detailed explanation of each of the five activities completed by both groups). |

| Determine the relevant components of the task and how to accomplish them (i.e. planning) | The activity was divided into a series of steps to be completed in order to meet the objective. Each step was given to the students in the first four activities. In the last activity, each team had to develop its plan (for the scaffolding for each activity, see Appendix E: Planning). |

| Establish clear goals | The goal of the activity, i.e. what students must deliver after finishing the activity, was defined and communicated to students (see the specific deliverable of each activity in the row: “Team Activity Deliverable” in Appendix C: Detailed explanation of each of the five activities completed by both groups) |

| Monitor | For each of the steps, the team had to monitor their work (for an example of the scaffolding and data, see Appendix F: Monitoring). |

| Evaluate progress | After finishing the activity, students individually evaluated and reflected on their work (for an example of the scaffolding and data, see Appendix G: Reflection). |

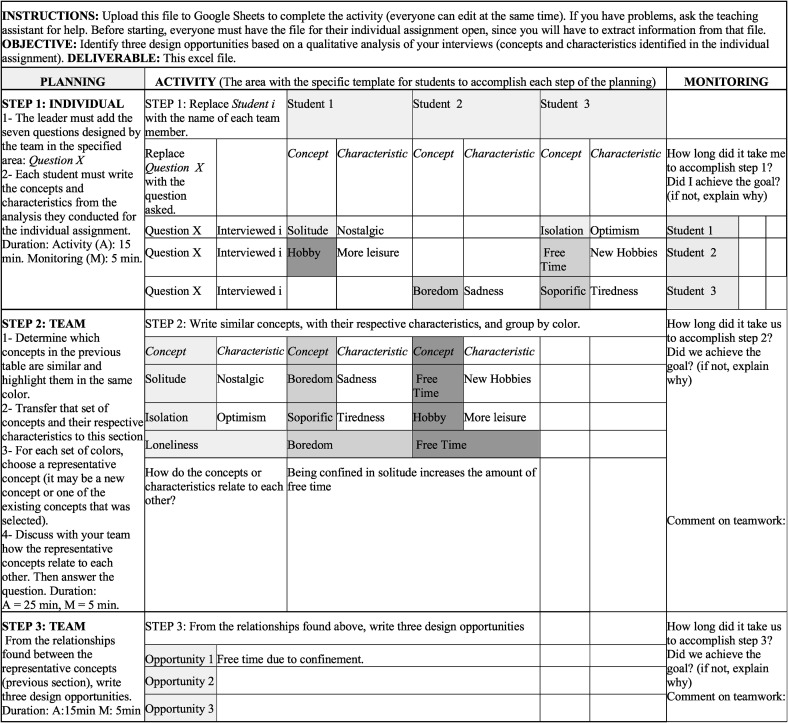

Fig. 2 shows the script for the activities for the experimental group. For each activity, every team received a worksheet shared through Google Drive, which they could work on collaboratively. The file specified the objective of the activity, the deliverable (goal), and the exact plan to be followed by the students. It also included a specific area where they could execute the plan and monitor each step. Appendix H shows the example script for the third activity given to the students in the experimental group.

Fig. 2.

Script for the activities for the experimental group.

Team-based metacognitive processes can be supported by having a clear objective, as well as carrying out activities such as planning, monitoring, evaluating, and reflecting (Schraw et al., 2006). Such activities help students develop team awareness and content understanding (Kim & Lim, 2018). As Pintrich (2000) suggested, monitoring represents the level of awareness and self-observation of cognition, behavior, and motivation. The scaffolding questions therefore looked to encourage students to observe how they worked as a team when completing the task. Appendix F presents the questions to be answered during the monitoring phase, as well as an example of the data.

Roberts (2017) argues that reflection is a crucial part of the metacognitive process and allows students to “close the loop” by evaluating their learning and improving their learning skills. According to Pintrich (2000), reflection involves evaluating our cognitive behavior and motivation by looking at the information that is available or analyzing the causes of success/failure. At the end of each activity, students had to write an individual reflection on their work. This included how they worked collaboratively, what they did right or wrong (i.e. evaluate), and what they could have done better. During the day, students had to upload their personal reflection to Canvas. Appendix G shows the questions that had to be answered during the individual reflection process, as well as some example entries.

Providing feedback on how students go about completing critical thinking activities is the best way of encouraging its development (Foo & Quek, 2019). Such feedback should be provided when the students can make sense of it, as well as being associated with the following task (Henderson et al., 2019). During the third activity, students were therefore given general feedback on their previous reflections and then asked to reflect on their work by answering the same questions they had answered for the previous activities. Appendix I shows the feedback given to students and how they relate to the different critical thinking skills.

2.3. Hypothesis

Based on the theoretical framework presented above, the following hypotheses were developed:

H1

An online project-based learning methodology encourages the development of critical thinking.

H2

The development of critical thinking improves when following a socially shared regulation scaffolding in online courses involving collaborative project-based learning activities.

H3

Giving feedback on previous reflections in an online setting focusing on critical thinking skills encourages the development of such skills.

2.4. Ethical considerations

This research was conducted with the approval of the university ethics committee. Students were informed about this research at the beginning of the semester and signed a consent form if they agreed to participate. They were advised that their participation would not affect their grade and that they could drop out of the study at any time.

2.5. Research sample

Only students who completed the critical thinking pre- and post-tests and participated in all five activities were considered in the study (see Table 2 for the number of participants).

Table 2.

Number of participants.

| Control Group | Experimental Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of students enrolled in the course. | 413 | 421 |

| Number of students who completed the critical thinking pre- and post-test. | 266 | 287 |

| Number of students considered in the study, i.e. completed the critical thinking pre- and post-test and participated in all five activities. | 191 | 191 |

Not all of the students who enrolled in the course completed the pre- and post-tests (Table 2). Of the students who did, 191 from the experimental group uploaded their reflection for all five activities (Section 2.2). Based on gender, stratified random sampling was then used to select 191 students from the control group to form the final sample (Frey, 2018).

The admissions process in Chile involves a standardized university entrance exam (PSU) and the student's school grades. This system has historically benefited high socioeconomic status students as students from private schools perform significantly better on the PSU test than students from public schools (Bernasconi & Rojas, 2003; Matear, 2006). For this reason, the students' school type was also considered in the statistical analysis (see Section 2.7).

Each of the ten sections was taught by a different professor and teaching assistants. This was therefore also considered as a variable in the statistical analysis so as to understand whether teaching effectiveness influenced the development of critical thinking (see section 2.7).

2.6. Instruments used and their validation

This quasi-experimental study involved a critical thinking pre- and post-test, as well as the students' monitoring and self-reflection for the five activities mentioned in Section 2.2. The data was analyzed using mixed-methods research, which aims to “increase the scope of the inquiry by selecting the methods most appropriate for multiple inquiry components” (Greene et al., 1989). In this type of study, the qualitative data is mainly used to assess the implementation and processes, while the quantitative methods are used to assess the outcomes (Greene et al., 1989; Schoonenboom et al., 2018). Following this approach, the critical thinking pre- and post-test was analyzed from a quantitative perspective. As the monitoring and reflection were part of the process they were analyzed using qualitative methods (see Section 2.6.2 for a description of the analysis).

2.6.1. Critical thinking pre- and post-test

To understand the impact of online problem-based learning on critical thinking, as well as the impact of the socially shared regulation scaffolding, the students completed an identical pre- and post-test (López et al., 2021).

The critical thinking assessment tool used in this study was developed following an iterative process of design-based research (Bakker & van Eerde, 2015). This process began with the theoretical definition of critical thinking proposed by the American Philosophical Association, where critical thinking is composed of the following skills: interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation (Facione, 1990). This definition was updated and complemented, replacing explanation with argumentation (Bex & Walton, 2016), and self-regulation with metacognition (Garrison & Akyol, 2015; Roebers, 2017). Therefore, the definition of critical thinking used in this assessment tool comprises the following sub-skills: interpretation, analysis, inference, evaluation, argumentation, and metacognition.

Based on this construct, a series of questions were developed for each of the sub-skills mentioned above. These questions were tested during each iteration of the design-based research process. For each iteration, a panel of experts evaluated the questions to determine whether they adequately reflected the sub-skills upon which they were based (Almanasreh et al., 2019). The psychometric properties were also evaluated based on item analysis (Shaw et al., 2019). This process led to the development of a test comprising 28 questions, with each measuring one of the sub-skills from the definition of critical thinking described above. The questions on the test were based on videos, news articles, and infographics, among others. All of the questions were open-ended as this format allows for the evaluation of higher-order thinking skills (Ku, 2009). As interpretation is a lower-order skill and cannot be measured using this format, the test did not include any questions based on this sub-skill (Tiruneh et al., 2017). See Appendix J for the critical thinking pre and post-test.

Item analysis was used to validate the pre- and post-tests. This involved evaluating the difficulty and discrimination of the items (DeVellis, 2006). Items with a difficulty value outside the range of 0.1 and 0.9 (i.e. the percentage of students who answered these items correctly) were eliminated (Shaw et al., 2019). Items with a discrimination value of less than 0.1 were also eliminated (Shaw et al., 2019).

The reliability of the tests was analyzed specifically based on this set of questions. Cronbach's alpha for the pre-test was α = 0.675, while for the post-test it was α = 0.651.

2.6.2. Reflections and monitoring

Investigator Triangulation (IT) was used to analyze the teams' monitoring and the students' reflections. The most common form of collaborative Investigator Triangulation involves multiple investigators using a pre-established coding framework to code qualitative data (Archibald, 2016).

The critical thinking skills measured by the pre- and post-test were used as the coding framework to analyze the teams' monitoring and students' reflections qualitatively. As the intervention followed a socially shared regulation process, it was also important to code the students' processes for regulating learning. This was done based on the definitions for self-regulation, co-regulation, and socially shared regulation proposed by Järvelä and Hadwin (2013) and Miller and Hadwin (2015). See Appendix K for these definitions and examples of the coding.

The research team designed a rubric based on these categories (see Appendix K). Using this rubric, a quality parameter (1 or 2) was assigned to each piece of data. If a code was present more than once in a student reflection or team monitoring the highest score was considered. See Appendix K for examples of the quality parameter.

Investigator Triangulation is enhanced when each investigator's area of expertise is different (Kimchi et al., 1991). For this study, a sociologist and an engineering student therefore coded the teams' monitoring and students' reflections. During the analysis, the research team met with the two raters in order to compare, discuss, and reach a consensus on the coding. When no consensus was reached, the two researchers independently coded the pieces. The Intercoder Reliability between both researchers was 0.641, which is considered substantial for qualitative data in exploratory academic research (Landis & Koch, 1977). Following this, a “negotiated agreement” strategy was adopted (Campbell et al., 2013; O'Connor & Joffe, 2020), meaning that the two researchers met, discussed, and reached a consensus on every piece of text (O'Connor & Joffe, 2020). By following this process, the researchers reviewed the codes assigned by the observers, thus strengthening the reliability of the results (Archibald, 2016). Fig. 3 shows the process of data coding.

Fig. 3.

Process of data coding.

This data was used to understand the development of critical thinking skills and the importance of feedback, present in the third activity (See section 2.7).

2.7. Data analysis

The experiment included a critical thinking pre- and post-test design (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). The first step was to check whether the post-test score was higher than the pre-test one for the whole data set (i.e. control and experimental) and for each group (i.e. control or experimental). An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (Owen et al., 1998) was conducted, as well as the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in order to verify the assumption of normality (Mishra et al., 2019).

The association between the critical thinking post-test score (0–100) and the information available on each student, such as pre-test score (0–100), gender (male or female), school type (private or public), student section (coded from 1 to 10 with a median of 39 students per section), and group (control or experimental) were considered. Linear regression modeling was proposed for examining this association (Kutner et al., 2004). Mathematically, this model is written as follows:

| (1) |

where represents the post-test score of the ith student and is her/his covariate vector with coefficients . Finally, denotes the error term and follows a Normal (0,) distribution.

Although the model is specified generically as in (1), there are different combinations of variables (25 = 32) that can potentially explain the post-test score. For example, the simplest model includes only the intercept (), i.e. no variables, while the most complex model includes all of the variables. To obtain the best model, all combinations were tested and the model with the best fit was selected. This selection was made based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), with the lowest AIC indicating the best fit (Akaike, 1973). Typically, if one model is more than 2 AIC units less than another, the former is considered significantly better than the latter (Brewer et al., 2016).

Finally, based on the qualitative data (see Section 2.6.2), the student reflections from the experimental group were analyzed by comparing Activities 1 and 3 and then Activities 1 and 5. Activities 1 and 5 are the first and last activities, while Activity 3 was when the students were given feedback on their reflections. This comparison looks to identify any trends by comparing the presence of each skill at two different moments during the experiment. These proportions were analyzed using a chi-square (χ2) test (Cochran, 1954). All of these analyses were performed in the R programming language (R Core Team, 2020).

3. Results

There was an improvement on the post-test, both overall as well as for each group (Table 3 ). However, the improvement for the experimental group was greater than the control group, suggesting that the intervention influenced the development of critical thinking.

Table 3.

Mean score and SD on critical thinking test.

|

Data considered in the analysis |

Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | |

| Total sample (control + experimental) | 57.14 (20.45) | 59.18 (19.11) |

| Control | 57.33 (18.81) | 58.32 (19.41) |

| Experimental | 56.95 (21.96) | 61.43 (18.58) |

Since the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test did not reject the hypothesis of normality for the total sample (p-value = 0.57) and for the two groups (control p-value = 0.28 and experimental p-value = 0.27), analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze whether the online project-based learning methodology improved critical thinking for all participants. The null hypothesis of the ANCOVA was that the mean score on the pre- and post-tests would be equal. This hypothesis was rejected for the total sample (F = 44.41, df = 1, p-value < 0.05, = 0.10, and Cohen's F effect size = 0.34) and for the two groups (control: F = 56.51, df = 1, p-value < 0.05, = 0.23, and Cohen's F effect size = 0.55; experimental: F = 8.31, df = 1, p-value < 0.05, = 0.04, and Cohen's F effect size = 0.21). Note that the Cohen's F effect size for the experimental group is relatively small. This is because this group has a non-linear relationship between the pre- and post-test scores, which can be verified through the small .

The association between the post-test scores and the information available for each student was analyzed using a linear regression model (see Section 2.7). All possible combinations of the five covariates (i.e. initial test score, gender, school type, student section, and group) were analyzed in 32 models. The best model was then selected based on the AIC, which is a model selection criterion that considers the trade-off between the goodness of fit and the simplicity of the model (see Section 2.7 for some references). Table 4 shows a summary of the regression parameters for the best model. Appendix L includes a ranking of all the models, explained variance (adjusted R-squared) of each model, and the significant variables (p-value < 0.05).

Table 4.

Statistical summary for the best model (AIC = 3294.8) with an asterisk for the significant variables (considering a significance level of 5%, p-value < 0.05).

| Parameter | Variable | Estimate | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 38.86∗ | 2.93 | (33.10; 44.62) | |

| Initial test score | 0.31∗ | 0.04 | (0.22; 0.40) | |

| Group | 5.24∗ | 1.84 | (1.62; 8.85) |

The intercept estimates the average post-test score (38.86) for a control group student with a pre-test score of zero. The estimate of suggests that a percentage point increase in the pre-test score leads to an average increase of 0.31 percentage points in the post-test score. On the other hand, the estimate of shows that, on average, students in the experimental group scored 5.24 points higher on the post-test than students in the control group. Furthermore, the explained variance (adjusted R-squared) of this model is 12%, which is satisfactory for this type of problem (Cohen, 1988).

Concerning the qualitative data, Table 5 presents the progression tendency for each critical thinking skill observed during activities 1, 3, and 5 (see Section 2.7). Even though metacognition was considered a coding category, it was not included in the data analysis because only ten phrases were coded under this specific category. For an example of each critical thinking skill, see Appendix K.

Table 5.

Progression tendency for each critical thinking skill.

| Critical Thinking Skill | Was the critical thinking skill present in the student's reflection? | Activity |

χ2 test |

Activity |

χ2 test |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | effect size | p-value | 3 | 5 | effect size | p-value | ||

| Argumentation | Not present | 75.27 | 59.14 | 0.16 | < 0.05 | 59.14 | 53.23 | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| Present | 24.73 | 40.86 | 40.86 | 46.78 | |||||

| Inference | Not present | 53.23 | 62.90 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 62.90 | 83.87 | 0.23 | < 0.05 |

| Present | 46.77 | 37.10 | 37.10 | 16.13 | |||||

| Interpretation | Not present | 54.84 | 57.53 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 57.53 | 63.44 | 0.05 | 0.46 |

| Present | 45.16 | 42.47 | 42.47 | 36.56 | |||||

| Evaluation | Not present | 71.50 | 52.69 | 0.18 | < 0.05 | 52.69 | 56.45 | 0.03 | 0.69 |

| Present | 28.50 | 47.31 | 47.31 | 43.55 | |||||

| Analysis | Not present | 84.95 | 43.55 | 0.42 | < 0.05 | 43.55 | 39.78 | 0.03 | 0.69 |

| Present | 15.05 | 56.45 | 56.45 | 60.22 | |||||

| Regulation | Not present | 77.60 | 72.05 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 72.05 | 89.25 | 0.20 | < 0.05 |

| Present | 22.40 | 27.95 | 27.95 | 10.75 | |||||

Table 5 shows that the number of students in the experimental group who were able to construct an argument, evaluate, and analyze increased significantly between the first and third activities. The presence of regulation (i.e. self-regulation, co-regulation, and shared regulation) increased, albeit not significantly, between the first and third activities. The students' inference and interpretation skills decreased, though again not significantly. Between the third and the fifth activities, interpretation and evaluation decreased, while argumentation and analysis increased. However, these differences were not statistically significant. Nevertheless, inference and regulation decreased significantly.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to understand how can we develop critical thinking among first-year undergraduates in an online setting.

Throughout the semester, the experimental and control groups in our study worked in teams following an online project-based methodology. Both groups performed significantly better on the critical thinking post-test than the pre-test (see Section 3). This increase in critical thinking is consistent with previous research, which suggests that active learning methodologies such as project-based learning (Hernández-de-Menéndez et al., 2019), as well as collaboration, promote critical thinking (Erdogan, 2019; Loes & Pascarella, 2017; Silva et al., 2019). The development of critical thinking skills in an online context has mainly focused on asynchronous discussion about real-world situations (Puig et al., 2020). The contribution of the present study is that it shows that project-based learning can foster critical thinking in a purely online setting.

Our findings align with the conceptual framework, the C♭-model, proposed by Sailer et al. (2021). This model suggests that engaging students in learning activities involving digital technologies supports the construction of new knowledge and the development of skills, while also positively affecting students' attitudes towards technology. It also indicates that students' knowledge, skills, and attitudes are, at the same time, requisites for the success of the proposed learning activities. In this study, students were involved in the four types of learning activities proposed by the C♭-model: Interactive activities, when working on a team project; Constructive activities, when students ideate and design the solution to a real-life problem; Passive learning, while watching the class videos or listening to class presentations; and Active learning, when making digital notes. In terms of the students' knowledge, skills, and attitudes, the model proposes four dimensions to be considered: Professional knowledge and skills, Self-regulation, Basic digital skills, and Attitudes towards digital technology. These four dimensions co-existed in the present study, as the students in both groups learned about and used 3D modeling software, Zoom, Canvas, and Google Drive (basic digital skills), positively affecting their attitudes towards technology (Sailer et al., 2021). The socially shared regulation scaffolding, which requires the students to self-regulate (Järvelä et al., 2019), fostered professional knowledge and skills, such as critical thinking. Self-regulation is also essential when working with ill-structured problems (Lawanto et al., 2019) as it is done within project-based learning which also proved to foster critical thinking.

Progress among students in the experimental group was significantly greater than for students in the control group (see Section 3). This suggests that the proposed socially shared regulation scaffolding promoted high-level group regulation strategies (Järvelä & Hadwin, 2013) that allowed for the development of critical thinking. It also supports the general idea that a team's success is influenced by the quality of the adopted regulation strategy and not just by the fact that they are working together (Panadero & Järvelä, 2015). The use of a socially shared regulation scaffolding is in line with the existing literature, which highlights the fact that scaffolding can allow learners to engage in activities that would otherwise be beyond their capabilities (Mohd Rum & Ismail, 2017). We have proven empirically that following a socially shared regulation scaffolding can boost the development of critical thinking in an online project-based setting.

Students in the experimental group were given feedback before writing their reflections for the third activity. This feedback emphasized the following critical thinking skills: analysis, evaluation, metacognition, regulation, and argumentation (see Appendix I). No feedback was given following the third activity. Analysis, evaluation and argumentation increased significantly, while regulation also increased (albeit not significantly) between the first and third activity (Table 5). These results are consistent with Thomas (2011), who states that when it comes to higher-order thinking skills students require feedback on what they need to do to develop a specific skill. As feedback increases the likelihood of meaningful learning (Henderson et al., 2019), it should be provided continuously. When reflecting, students could freely answer the questions in Appendix G, without explicitly referring to any of the critical thinking skills. These results therefore show that the students transitioned between skills. For example, the way argumentation was defined allowed an interpretation to become an argument if the reasons supporting the student's position were described (see Appendix K). Accordingly, this may explain the decrease in interpretation and subsequent increase in argumentation. The reason for the decrease in inference throughout the activities can be explained by the fact that it was not mentioned in the feedback given to the students (see Appendix I).

None of the other variables that were studied (i.e. gender, school type, and student section) proved to be significant for any of the 32 models (see Appendix L). These findings are in line with the findings by Masek and Yamin (2011), who showed that gender did not appear to be a relevant predictor for the development of critical thinking when using project-based learning. The fact that school type was also not significant is consistent with the results described by Hilliger et al. (2018), who found that students from the public-school system in Chile enjoy considerable academic success during their first year at university. Finally, the fact that student section (i.e. teaching effectiveness) was not significant is in line with Uttl et al. (2017), who showed that the correlation between teaching effectiveness and student learning decreases when the number of sections increases.

5. Conclusion, limitations, and future research

This study aimed to answer the research question: How can we develop critical thinking among first-year undergraduates in an online setting?

To answer this question, 834 first-year engineering undergraduates participated in an online project-based course involving five collaborative activities. A control and experimental group were established, with the experimental group following a socially shared regulation scaffolding. A critical thinking pre- and post-test was completed by both groups in order to assess the impact on critical thinking. We learned that online project-based learning had a significant impact on both groups. However, following a socially shared regulation scaffolding led to significantly greater improvements.

The first hypothesis of this study was that an online project-based learning methodology encourages the development of critical thinking. The results of this study show that both groups increased their critical thinking skills significantly throughout the experience. The first contribution of this study is that it demonstrates empirically that an online project-based learning methodology can be used to develop critical thinking skills (see Section 3).

The second hypothesis was that the development of critical thinking improves when following a socially shared regulation scaffolding in online courses involving collaborative project-based learning activities. The results showed that the experimental group improved their critical thinking skills significantly more than the control group (see Section 3). Therefore, the second contribution of this study is that it demonstrates that critical thinking can be boosted by following a socially shared regulation scaffolding in an online project-based setting.

The third hypothesis was that giving feedback on previous reflections in an online setting focusing on critical thinking skills encourages the development of such skills. The results revealed that three of the skills (Argumentation, Evaluation, and Analysis) improved significantly when giving feedback. While a fourth skill (Regulation) also improved, the results were not significant. As feedback on critical thinking was only provided to the students once during the course, future work should study the impact of providing students with feedback on every element of critical thinking after each activity.

The existing literature has systematically highlighted the importance of project-based learning in developing critical thinking skills (Bezanilla et al., 2019). It has also shown that socially shared regulation can foster higher-order thinking skills such as metacognition (Sobocinski et al., 2020). However, there has been little assessment of how these effects translate into an online setting. These findings bridge that gap by providing quality evidence supporting the assumption that these effects do indeed translate into an online environment.

While the results are encouraging, we must consider the limitations of the study. Of the 834 learners enrolled in the course, only 382 students were considered in the study (see Section 2.5). The selection bias generated by this loss of participants may therefore affect the findings (Wolbring & Treischl, 2016). However, any possible hypothesis regarding the direction of this bias would be completely unfounded. The sample only comprised students from an engineering school at a highly selective university. Only 31% of the sample were female, while just 27% came from the public education system. As for the limitations of the course itself, the final deliverable for a project-based course is the development of a product (Usher & Barak, 2018). In this case, the main difference between the online and face-to-face versions of the course was the prototyping phase. Students normally use the university prototyping laboratories during the face-to-face course in order to deliver an actual physical product. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, students were asked to deliver an abstract of their project, a poster, and a 3D model or mock-up of their solution. Furthermore, the critical thinking pre-and post-tests were completed asynchronously and, therefore, the conditions in which they were taken are also unknown. Finally, the study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic and it is not known how this context may have affected the students' performance.

These limitations represent opportunities for future research. It would be important to repeat the study with a different profile of student. Another important addition would be to include qualitative research based on the students' reflections and analyze how their writing changes from one critical thinking skill to another. Furthermore, the intervention was originally designed to be carried out during face-to-face lectures and had to be adapted to an online context. We therefore recommend redesigning the activities to take full advantage of the sort of interactive media and reusable learning objects available in an online setting. In terms of online collaboration, the intervention was based on a socially shared scaffolding for the regulation of learning; the way teams regulate their work online, and face-to-face may be different (Lin, 2020). Future research should therefore also look to examine the differences between the impact of the proposed scaffolding in a blended and face-to-face setting.

Credit author statement

Catalina Cortázar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft; Miguel Nussbaum: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision; Jorge Harcha: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation; Danilo Alvares: Formal analysis; Felipe López: Resources; Julián Goñi Investigation; Verónica Cabezas: Writing – review & editing

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the team of professors who taught the course, the Office of Undergraduate Studies, and the Office of Engineering Education. This study was partially funded by FONDEDOC and FONDECYT 1180024.

Appendix.

Appendix A.

Cornerstone Course Summary

| Teaching Methods | Project-based Learning Flipped Classroom In-class teamwork activities and workshops |

| Course content | Engineering Design Process, Data analysis (qualitative and quantitative), Materials, Mathematical Models, Estimation |

| Learning Outcomes | 1. Solve a real-world problem. Apply a user-centered design methodology to an engineering problem. Produce a device that responds to a specific group's inequalities in terms of social, economic or environmental vulnerability. 2. Articulate individual contributions to teamwork in order to develop a joint project. |

| Assessment Methods | 1. Individual assessment: Homework assignments & exam. 2. Team assessment: Oral presentations on the design process (research & prototype). 3. Peer assessment after each team deliverable. |

| Evaluation Criteria | 1. Professor: During the semester, the professor assesses the design process. 2. Stakeholders: The final deliverable is presented at a technology fair, where they are assessed by different stakeholders. |

Appendix B. Example of an individual assignment

Individual Assignment 3

Objective: To advance in the analysis of your data individually.

-

1.

Individually you should interview at least two people using the set of questions your team defined. Before starting the interviews, you must have the consent of the interviewee.

-

2.

Transcribe the two interviews that you conducted. The transcript must include the consent, questions, and answers obtained.

-

3.

Qualitatively analyze both interviews according to the methodologies seen in class.

-

4.

Identify concepts and characteristics in each of the texts (remember that concepts are short words or phrases). Each answer must have at least one concept. If the answer has several paragraphs, the minimum-optimum is one concept per paragraph.

Recommendation: This analysis will serve as input for your first presentation.

Example of concept and characteristic

Each concept must be linked to its characteristic(s). For example, when faced with the question: How have you felt during confinement?

My interviewees could answer:

-

•

Interviewee 1: I've been sad since I haven't been able to see my friends.

-

•

Interviewee 2: Being at home, not seeing anyone, has allowed me to spend my time on the things that I am most passionate about, such as painting and playing the guitar.

As an example, in both cases my concept could be Loneliness.

However, the characteristics are different.

-

•

Interviewee 1 speaks from nostalgia.

-

•

Interviewee 2 speaks from optimism.

Appendix C. Detailed explanation of each of the five activities completed by both groups (i.e. control and experimental)

| Class Activity Number | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Design Phase | Know (your team) | Know (your user & context) | Identify |

| Individual Assignment Objective | Introduce yourself. | Learn about your user and his/her context. | Analyze the interviews. |

| Individual Assignment Deliverable (input for the team activity). | One-minute video about yourself answering the following questions: 1 Why did you choose to study engineering? 2 What do you like? 3 What do you not like? 4 How do you imagine this course will be? 5 How can you contribute to the teamwork? Answer considering the following attributes: Sincere, Patient, Innovative, Open-minded, Persistent, Good communicator, Responsible. |

Individually, define the interview objective and design the questions you consider relevant to your user and his/her context. Give an argument for how these sets of questions respond to the interview objective. | Individually interview at least two people with the set of questions designed in team activity 2. Analyze the responses qualitatively, determining the relevant concepts and their characteristics (Grounded Theory). |

| Team Activity Name | Know (your team) | Know (your user & context) | Identify Design Opportunities |

| Team Activity Objective | Determine the team leader. Use personal videos as input. | Determine at least seven questions that you, as a team, considered relevant to ask in order to get to know your user and context. Use the files from the individual assignment as input. | Identify three design opportunities based on a qualitative analysis of your interviews (concepts and characteristics identified in the individual assignment). |

| Team Activity Deliverable | Name of the team leader. | The interview objective and a set of questions with their specific objectives. An argument for how these sets of questions respond to the general interview objective. | Based on an analysis of all the interviews, answer the three following questions: 1 What are the central phenomena or ideas that emerge from the interviews? 2 What are the characteristics or properties of those central phenomena or ideas? 3 How are these central ideas or phenomena related? Determine three design opportunities that respond to your chosen user and his/her context. |

| Class Activity Number | 4 | 5 | |

| Design Phase | Ideation & Prototype | Test | |

| Individual Assignment Objective | Ideate solutions | Determine the testing procedure. | |

| Individual Assignment Deliverable (input for the team activity). | 1 Design and explain three different solutions, which do not share common elements, for the chosen design opportunity (ONE opportunity with THREE solutions). 2 For each of the solutions, argue how it solves the opportunity mentioned above (maximum five lines). 3 For each of the solutions, argue why it is consistent with the user and his/her context (maximum five lines). 4 For each of the solutions draw a sketch to graphically complement your proposal. Your sketch should be self-explanatory in terms of form and function. |

1 Determine the general objectives of the testing. 2 Choose a testing methodology (Heuristic, AB testing, or Walkthrough). Justify your choice. 3 Choose with whom you will test (user, expert, or key informant). Justify your choice. 4. Design a set of questions or activities to achieve the objective of the testing. Each question/activity must have a specific objective. 5. Briefly, give an argument for how this set of questions/activities meets the general objective. |

|

| Team Activity Name | Ideate solutions & prototype | Test your solution | |

| Team Activity Objective | Based on the design opportunity chosen by the team, jointly design a solution relevant to the context, user, and opportunity. Use the files from the individual assignment as input. | Design the team testing procedure and questions/activities to be asked/performed. Use the files from the individual assignment as input. | |

| Team Activity Deliverable | 1 Context, user, and design opportunity. 2 Which individual solutions did you rely on when designing your new solution, and why? 3 Sketch and explanation of the team's proposed solution. |

1 Context, user, design opportunity and proposed solution. 2 Testing objective. 3 At least five questions or testing activities that fulfill the testing objective. |

|

Appendix D. Example script for the third activity given to the students in the control group

OBJECTIVE OF THE ACTIVITY: Identify three design opportunities based on a qualitative analysis of your interviews (concepts and characteristics identified in the individual assignment)

Steps to follow:

-

1

Each member of the team should read out the concepts and characteristics determined by their interviews.

-

2Using these concepts and characteristics as input (individual assignment), the whole team should answer the following questions (you can draw a map to see the relationships between the phenomena):

-

i.What are the central phenomena or ideas that emerge from the interviews?

-

ii.What are the characteristics or properties of those central phenomena or ideas?

-

iii.How are these central ideas or phenomena related?

-

i.

-

3

Determine three design opportunities that respond to your chosen user and their context.

-

4

Each team leader must upload the document with their three design opportunities to the section created in Canvas.

-

5

The document must contain the answer to the questions above, as well as the three design opportunities.

Appendix E. Planning

E.1.

Plan for the first activity

| Plan | Instruction | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 1.1 Watch the videos of your team members and mark the attributes of each member with an X, as shown in the example. | 15 min |

| Step 2 | 2.1 Rank the attributes that a leader must have, from 1 to 7 (1 being most relevant and 7 being least relevant). | 5 min |

| Step 3 | 3.1 For each attribute, write the name of every team member who was considered to have shown said attribute (using the data from Table 1 from each of you). There can be more than one person per attribute. | 10 min |

| Step 4 | 4.1 Considering the individual attribute ranking (see 2.1), you must discuss with your teammates the reason for the first two positions in your rank. If considered necessary, you can re-rank your attributes following this discussion. | 20 min |

| Step 5 | 5.1 As a team, rank the attributes from 1 to 7. | 20 min |

| Step 6 | 6.1 Choose the team leader. The member whose profile best matches the ranking of attributes established by your team should be named the group leader. You must write their name and email address. |

5 min |

E.2.

Plan for the second activity

| Plan | Instruction | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 1.1 Select the seven questions from your individual assignment that seem most appropriate for achieving the objective of getting to know your user and context. Write your name where it says Member No. and copy the questions and their objectives in the rows of that column. This table must be filled in simultaneously. | 10 min |

| Step 2 | 2.1 With your team, determine which objectives (see Step 1) are the most relevant for your research. The team leader should fill in the table. | 5 min |

| Step 3 | 3.1 Write the objectives identified in the previous section (see Step 2). Under each objective, write the questions from Step 1 that should provide an answer for that objective. The leader of each team is in charge of filling out the document. | 15 min |

| Step 4 | 4.1 Design a question for each objective. You can choose one from Step 3 or write a new one. | 10 min |

E.3.

Plan for the third activity

| Plan | Instruction | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 1.1 The team leader must add the seven questions designed by the team to the specified area: Question X | 15 min |

| 1.2 Each student must write down the concepts and characteristics that came from analyzing the responses to each question. | ||

| Step 2 | 2.1 Determine which concepts in the previous table (Step 1) are similar and highlight them in the same color. | 25 min |

| 2.2 Transfer that set of concepts and their respective characteristics to this section (Step 2) | ||

| 2.3 For each set of colors, choose a representative concept and write it down. It may be a new word or one of the concepts that has been highlighted. | ||

| 2.4 Discuss with your team how the representative concepts relate to each other, then answer the question in the form. | ||

| Step 3 | 3.1 Determine three design opportunities based on the relationships found between the representative concepts (Step 2). | 15 min |

E.4.

Plan for the fourth activity

| Plan | Instruction | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 1.1 Each team member must explain to the team the three proposed solutions from their individual assignment. | 20 min |

| 1.2 When listening to your teammates' solutions write down the solutions that seem to have elements in common (work individually). | ||

| Step 2 | 2.1 With your team, identify similar solutions by grouping them with a colored circle (make categories). | 15 min |

| Step 3 | 3.1 For each of the colors used, answer the following: What are the common elements of these solutions? How do these elements respond to the opportunity you defined? |

10 min |

| 3.2 Rank the categories according to how relevant they are to the opportunity defined by the team. | ||

| Step 4 | 4.1 As a team, design a single solution considering the most critical categories defined in Step 3.2 | 10 min |

E.5.

Plan for the fifth activity. In this activity, each team had to design their own plan. Two of the teams' plans are presented below.. E.5.1. Plan proposed by team “A”E.5.2. Plan proposed by team “B”

| Plan | Instruction | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 1.1 Write down the objectives, highlighting the keywords for each one. | 10 min |

| Step 2 | 2.1 From Step 1, write down a group objective. | 10 min |

| Step 3 | 3.1 Each of the students must choose a maximum of 5 questions that they have written in the individual assignment and consider the most relevant. Highlight 1 keyword for each question. | 5 min |

| Step 4 | 4.1 Relate the concepts highlighted in Step 3. | 10 min |

| Step 5 | 5.1 Choose five or more questions that satisfy the team's main objective. | 15 min |

| Plan | Instruction | Time |

| Step 1 | 1.1 Explain to your teammates what your test prototypes were. | 5 min |

| Step 2 | 2.1 Rank the different types of testing (AB testing, walkthrough, or heuristic) and explain your decision. As a team, choose one of the types of testing to be performed. Then, write down the type of test chosen and justify the team's decision. | 15 min |

| Step 3 | 3.1 Each member must write down the general objectives of their individual assignment and, as a team, we must write down a new general objective. Then, decide as a team who will work with whom conducting the testing. | 10 min |

| Step 4 | 4.1 With the information gathered from the previous steps, design a group testing protocol. It must contain the design opportunity, the user, general objectives of the testing, and who will work with whom. Additionally, it must also include at least five questions or activities. | 20 min |

Appendix F. Monitoring

| Scaffolding Phase | Answered by | Answered when | Questions | Examples of data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring | Whole team together | While performing the activity, after finishing each of the steps (planning). | How long did it take us (the team) to complete the task? | Team 1: “35 min" Team 2: “16 min" Team 3: “20 min" |

| Did we (the team) fulfill the objective of the task? | Team 1, 2 & 3: “yes" | |||

| Add comments about your teamwork. | Team 1: “The performance was quite slow, due to a clutter of ideas, but the objective was met without any problems." Team 2: “Each member explained their solutions quickly and clearly. There were few doubts, which we discussed quickly, and there were not many solutions or ideas that already existed." Team 3: “It took us longer than expected since it took us a while to comment on the activity. Several of us thought differently about how the activity should be carried out, although we had points in common. However, the goal was met." |

Appendix G. Reflections

| Scaffolding Phase | Answered by | Answered when | Questions | Examples of data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection | Individually | After finishing the activity. | 1 Individually reflect on: How did your team work through today's process? What was each team member's role? What did you do well and what did you do poorly as a team? Once this information has been analyzed, answer the following: What could your team have done differently? 2 Did you observe any progress in teamwork when completing the previous activity? If so, what progress was made? |

Student 1: 1. “This time, we improved from the start by making 2 spreadsheets instead of 1, unlike last class. I feel that this activity was more complicated than the previous ones as it required more reflection; despite this, we were able to complete it without any problems. I feel that the other team (sustainability) progressed a little slower than the autism team, so they did not manage to finish, but after class, they will send it to me and so I'll be able to upload it. Anyway, you have to keep in mind that they have one less member so it can affect their progress. I would have liked us to have met as a whole group at the end of today's class to reflect on the topic that we will choose but, due to time constraints, we weren't able to.” 2. “I feel that we have worked more effectively. Besides, now it's easier for us to understand the activities since they are quite similar to the previous ones so, in general, we had fewer doubts this class than the last one." Student 2: “Today, the work was much more effective than the last group task in Excel. We finished just in time, doing a good job. In general, I feel that the estimated times in the plan for each task are not very realistic, but at least today we finished the activity. As we had already worked with this methodology before, the instructions were clearer, so we had no problems. A teammate had problems with his computer, and we waited for him while we were working. I feel it was still difficult to extract a concept and characteristic from an answer since some questions covered more than one topic. There was some confusion about whether the concepts were correct or not. To make decisions we generally voted, and I feel that's a good thing. We are failing to participate; some members don't say much about the work. Conclusion: use time well, finish the activity, find excellent design opportunities. In a normal context, I feel that this work would flow much better, but this methodology still has certain advantages such as, for example, everyone contributes simultaneously to the same document. Today, I felt that we did an excellent job as a team and got used to the course methodology. Therefore, and by making this reflection, I have a good feeling about the class." |

Appendix H. Example script for the third activity given to the students in the experimental group

Appendix I. Feedback given to students and their relation to the different critical thinking skills

I.1. Feedback given to students on the previous reflections before asking them to reflect on their work from the third activity

By analyzing previous reflections, we have seen that there are students who can:

-

1

Analyze the process and draw conclusions from the activity.

-

2

Reflect on how the instructions for the task were followed.

-

3

Determine the criteria for evaluating the work done by the team or individually.

-

4

Recognize mistakes and propose improvements.

-

5

Transfer observations from the activity to another context.

-

6

Indicate what they learned or concluded from this process of reflection.

I.2. Relation between each Critical Thinking skill and the feedback given. This table was not given to the students

| Critical Thinking Skill | Prompts |

|---|---|

| Analyze | Analyze the process and draw conclusions from the activity. |

| Analyze | Reflect on how the instructions for the task were followed. |

| Evaluate | Determine the criteria for evaluating the work done by the team or individually. |

| Regulate (auto-, co-, shared-) | Recognize mistakes and propose improvements. |

| Metacognition | Transfer observations from the activity to another context. |

| Argumentation | Indicate what they learned or concluded from this process of reflection. |

Appendix J. Critical Thinking pre- and post-test

I. VIDEO(advertising campaigns)

-

a.

Watch the following video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vtabkq9f9Co

- Based on this video, please answer the following question.

-

1.What is the main message of the commercial for Soprole Milk Custard?

-

2.Identify 3 steps that you followed in order to answer the previous question

-

3.Now, in your opinion, do you think that your response to question 1 was correct or incorrect?

-

4.When answering the question: “1. What is the main message of the commercial for Soprole Milk Custard?” Did you find it easy or difficult?

-

5.Based on your response, why did you find it easy or difficult?

-

6.Write your own question based on the commercial

-

7.Based on your previous question, set a requirement that the response to the question should meet in order to be considered correct.

-

8.You can write another criteria if you want to.

-

1.

-

b.

Watch the following video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WhESgLoQbZQ

Based on this video, please answer the following question: Imagine that a classmate is asked the following question: What is the main message of the commercial for Colun manjar? And their response was this: “Everything tastes better with Colun manjar”.

-

9.

What score would you give your classmate's response based on the following marking guide?

| Score | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 2 | The response explicitly refers to the fact that a mother's love is shown through Colun manjar |

| 1 | The response contains one of the following elements:

|

| 0 | Any other response |

-

10.

Justify the score you gave, based on the above marking guide:

-

11.

One student's response to the following question: What was the author's main intention when including the phrase “Me too, we're brothers, gimme five”? Was “To evoke a positive emotion”

-

12.

Do you think this is correct or incorrect?

-

13.

Justify your response to question 12

II. INFORMATIVE TEXT

Informative texts are the sort of texts whose main aim is to inform and raise awareness about specific issues. Please read Estadounidenses ven la inteligencia artificial como destructora de empleos [Americans see Artificial Intelligence as a Job Destroyer] (San Juan, 2019), and then answer the questions that follow.

-

14

What is the main idea of this text?

III. INFOGRAPHICS

Just like letters, images have been with us throughout our existence. This type of visual language has enabled and fostered the development of a range of different skills and media. One such media is infographics, an informative and visual representation that looks to communicate a message using a combination of data and images. Inteligencia Artificial aplicada a Chatbots [Artificial Intelligence Applied to Chatbots] (Hey Now, 2018) is an example of an infographic. Study it carefully and then complete the activities that follow.

-

15.

What conclusion could you make regarding the use of chatbots by companies?

-

16.

Do you think that people benefit from companies using artificial intelligence?

IV. OPINION PIECE

An opinion piece is a type of text where thought leaders give their opinion on a relevant topic of interest. Politicians, academics, journalists, sportspeople and other public figures have found opinion pieces to be a useful way of expressing themselves and sharing their point of view on a range of topics.

-

a.OPINION PIECE I: Pleaser read Defensa de la inmigración [In Defense of Immigration] (Peña, 2019), and then answer the following questions:

-

17.What is the main idea of this opinion piece?

-

18.What might the author's intention have been when including the following phrase in their opinion piece?

- “They're joined by groups of different cultural heritage who seem to have forgotten that their own story begins with … [an] immigrant”.

-

19.Based on the text, what can we conclude about modern societies?

-

20.In terms of patriotism in Chilean society, we can infer that:

-

21.Identify and write a conclusion based on this column

-

17.

-

bOPINION PIECE II: Please read La Peste [La Plague] (Matamala, 2020), and then answer the following questions:

-

22.Why do you think that the author included the following phrase in his column? … “the plague is not tailored to man, therefore man thinks that the plague is unreal, it is a bad dream that will go away”.

-

23.Identify and describe an idea that the author wanted to communicate through this column.

-

24.What phrase(s) did the author use to support this idea?

-

25.Identify and describe an idea (different from the previous one) that the author wanted to communicate through this column. If you think there are no more ideas, you can suggest this as your answer.

-

26.What phrase(s) did the author use to support this idea? (in case you have identified a new idea)

-

27.What is the main conclusion you could take from this opinion piece?

-

28.What is a secondary conclusion that you could take from this opinion piece?

-

22.

Appendix K. Coding definitions, rubric and examples

Table K.1.

Critical thinking skills definition, rubric & examples

| Code: Critical Thinking Skills | Definitions | Quality = 1 | Quality = 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretation | Describes an experience. | Describes what happened superficially. Example: “With a great leader." |

Describes what happened in detail. Example: “Today, the activity was long, but we achieved what was expected and in the requested timeframe as we finished during class." |

| Inference | Identifies an element and formulates a hypothesis in order to draw a conclusion. | Formulates hypotheses, identifying elements on which to draw a conclusion. This is done superficially. Example: “I still think that we need to interact more, although I think this may be due to the time of the class because we're all a little sleepy." |

Formulates hypotheses, identifying elements on which to draw a conclusion. This is done in detail. Example: “The two women in the group continue to participate little, but I think this is only due to the fact that it is online work. I believe that when we have face-to-face classes, the participation of all members of the team will be more equal." |

| Analysis | Determines roles in an argument, is capable of developing relations and comparing ideas. | Compares ideas, develops relationships or abstract concepts from what is proposed. This is done superficially. Example: “The previous activity we worked very fast, this time we took more time to analyze the information, therefore it took us longer." |

Compares ideas, develops relationships or abstract concepts from what is proposed. This is done in detail. Example: “From my perspective, in this activity we saved a lot of time thanks to the fact that it was in PowerPoint. We tried to work as a team to do each of the activities and, in general, there were no problems and it was fast, but I feel that we did not consider everything in the sorting part. Some classifications emerged that included others, and we ran out of colors to classify ideas that were not related to others, so they were immediately discarded. This is why I think we should have given ourselves more time to think about this part and do it better, but with the time limits, it wasn't possible." |

| Evaluation | Assesses statements, recognizes the factors involved, raises questions. | Recognizes factors that allow for an evaluation. They are presented without any real detail. Example: “I believe that we chose really well thanks to the good communication between us." |

Recognizes factors that allow for an evaluation. They are presented in detail. Example: “Among the things we did well as a group, I can highlight our organization, respect, and open-mindedness. It was a gratifying and fluid process, in which we agreed with most of our opinions, but a negative thing would be that we did some sections of the activity very quickly, as we were against the clock. However, I am delighted to have completed everything conscientiously and responsibly." |

| Argumentation | There is a coherent explanation in response to an event. There is an identification of steps, a sequence of steps linked to a purpose. | The breakdown of steps to achieve a result is present, or reasons are given to accept an argument. This is done superficially. Example: “After doing the activity, I am quite satisfied with my group. It was the first time the members would work together conscientiously and responsibly to work out which option was the best." |

The breakdown of steps to achieve a result is present, or reasons are given to accept an argument. This is done in depth. Example: “Despite everyone having worked on the activity, a constant difficulty was the speed at which we worked. Some delays could have been avoided. These were mainly caused by differences between us and not being used to the platform that was assigned for doing the work." |

| Metacognition | Capable of generalizing processes and transferring them to another context. | The sentence or paragraph talks about how you can apply what you learned/what happened during the activity in the future. This is done superficially. Example: “For the next time, we have to organize our time better." |

The sentence or paragraph talks about how you can apply what you learned/what happened during the activity in the future. This is done in detail. Example: “This activity is beneficial for daily life. For example, in a future company when we want to do a project, and we have to give ideas, we will have to organize these ideas in order to use them more efficiently." |

Table K.2.

Regulations of learning: definitions, rubric &; examples

| Code: Type of Regulation | Definitions | Quality = 1 | Quality = 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Regulation | Self-examination. Presents mistakes and procedures to change (“I" perspective) | Explains what was done or could have been done differently. This is done superficially. Example: “I should have proudly accepted the compliments that everyone gave me." |

Explains what was done or could have been done differently. This is done in detail. Example: “I tried to give a lot of ideas when doing the activity, and I encouraged my teammates to seek perfection in our answers, always respecting the answers already proposed and supporting what the majority decided." |

| Co-Regulation | Activities were guided, supported, shaped, or constrained by others in the group (“you” perspective) | There is a “someone” who regulates the rest of the team or another teammate. This is only explained superficially. Example: “Renata was the best at organizing the team, and that is why we chose her as our leader." |