Abstract

Soft‐tissue sarcomas (STS) represent a group of rare and heterogeneous tumors associated with several challenges, including incorrect or late diagnosis, the lack of clinical expertise, and limited therapeutic options. Digital pathology and radiomics represent transformative technologies that appear promising for improving the accuracy of cancer diagnosis, characterization and monitoring. Herein, we review the potential role of the application of digital pathology and radiomics in managing patients with STS. We have particularly described the main results and the limits of the studies using radiomics to refine diagnosis or predict the outcome of patients with soft‐tissue sarcomas. We also discussed the current limitation of implementing radiomics in routine settings. Standard management approaches for STS have not improved since the early 1970s. Immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer treatment; nonetheless, immuno‐oncology agents have not yet been approved for patients with STS. However, several lines of evidence indicate that immunotherapy may represent an efficient therapeutic strategy for this group of diseases. Thus, we emphasized the remarkable potential of immunotherapy in sarcoma treatment by focusing on recent data regarding the immune landscape of these tumors. We have particularly emphasized the fact that the development of immunotherapy for sarcomas is not an aspect of histology (except for alveolar soft‐part sarcoma) but rather that of the tumor microenvironment. Future studies investigating immunotherapy strategies in sarcomas should incorporate at least the presence of tertiary lymphoid structures as a stratification factor in their design, besides including a strong translational program that will allow for a better understanding of the determinants involved in sensitivity and treatment resistance to immune‐oncology agents.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, digital pathology, immunotherapy, radiomics, sarcoma

List of abbreviations

- 18F‐FDG

18F‐fluoro‐2‐deoxuglucose

- AI

artificial intelligence

- BCR

B cell‐related

- c‐index

concordance index

- CE

contrast enhanced

- CI

confidence interval

- CINSARC

Complexity INdex in SARComas

- CNN

convolutional neural network

- CT

computed tomography

- CTLA‐4

cytotoxic T‐Lymphocyte antigen 4

- DWI

diffusion weighted imaging

- FNCLCC

French ‘Federation National des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer’

- FS

fat suppressed

- IBSI, Imaging Biomarker Standardization Initiative ; ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- LAG3

lymphocyte activation gene‐3

- LFS

local relapse‐free survival

- MFS

metastatic relapse‐free survival

- MRCLPS

myxoid round cells liposarcoma

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OS

overall survival

- PD‐1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PD‐L1

programmed cell death ligand 1

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PERCIST

PET evaluation response criteria in solid tumor

- PFS

progression free survival

- RECIST

response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- PFS

progression free survival

- RFs

radiomics features

- RQS

radiomics quality score

- RR

Response rate

- STS

soft tissue sarcomas

- TCR

T cell receptor

- TILs

tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

- TLS

tertiary lymphoid structure

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- WI

weighted imaging

1. BACKGROUND

Soft‐tissue sarcomas (STS) represent a heterogeneous group of tumors. An accurate histological diagnosis and an assessment of the risk of relapse are critical for delineating treatment strategies. Traditional pathology approaches and molecular genetic assays have played a crucial role in the classification of STS. Recently, artificial intelligence (AI)‐based solutions paved the way for the development of digital pathology approaches, with whole‐slide imaging that enables capturing relevant information beyond human visual perception. Such progress has been implemented in the field of imaging with the possibility of characterizing human tumors through “radiomics” analyses, which are based on several image‐derived, quantitative measurements, including intensity histogram, spatial distribution relationships, and textural heterogeneity. Both digital pathology and radiomics approaches can be used to understand the relationships between histological and imaging characteristics of STS, such as heterogeneity and their biological characteristics or expected prognosis and treatment outcomes. Besides improving the staging and prognosis assessment, expanding the therapeutic armamentarium is another challenge for better care of patients with STS. Chemotherapy has reached a therapeutic plateau in this group of diseases [1]. Immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer treatment; nonetheless, immuno‐oncology agents have not yet been approved for patients with STS. However, several lines of evidence suggest that immunotherapy may represent an efficient therapeutic strategy for this group of diseases.

In this review, we provide an up‐to‐date and state‐of‐the‐art application of digital pathology and radiomics in managing patients with STS and the potential role of immunotherapy in improving patient outcomes.

2. IMPROVING THE PROGNOSTICATION OF PATIENTS WITH STS THROUGH DIGITAL PATHOLOGY AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Digital pathology is based on the use of algorithms, machine‐learning techniques, and AI to extract information from routine pathologic images. In recent years, several studies have demonstrated the potential of digital pathology in improving the diagnostic and staging workflow in human tumors. However, the application of digital pathology in STS is unclear.

STS constitutes a heterogeneous group of malignant tumors, representing 1% and 15% of cancer in adults and children, respectively [1]. Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment. However, up to 40% of the patients develop metastatic relapse despite optimal locoregional treatment, which leads to death in most cases [2]. Assessing the risk of relapse is an important concern for physicians managing these patients. Perioperative chemotherapy reduces the risk of relapse by approximately 30% [3, 4, 5, 6]. However, identifying patients most likely to benefit from perioperative systemic treatment remains challenging [7]. Clinical factors, such as the grade, size, and depth of the tumors, are usually associated with the risk of metastatic relapse and are considered by oncologists for assessing the relapse risk [8]. A nomogram may serve as a convenient and reliable tool for the individualized prediction of recurrence [2, 9]. However, this method is not perfect. Combining gene expression profiling data through the Complexity INdex in SARComas (CINSARC) signature improves the nomogram, thereby enhancing the prediction of relapse [10]. Moreover, despite the increasing incorporation of genomic profiling into patient care, the procedure is not routinely followed at most healthcare facilities handling sarcoma cases.

Recently, AI has appeared promising in predicting the prognosis of several conditions [11]. There are reports on the emergence of models that could directly predict disease outcomes from digitized whole‐slide images of mesothelioma [12] or hepatocellular carcinoma [13] using deep‐learning methods. These models outperformed the previous methods that relied on expensive and time‐consuming expert annotations or gradings for producing results. In addition, multiple studies have demonstrated the benefits of performing a multimodal analysis to complement AI image analysis with expert knowledge and clinical data [14]. Foersch et al. [15] reported an example of such synergy for STS by predicting the disease‐specific survival in specific STS subtypes. They demonstrated the ability of multimodal machine learning to predict metastatic relapse in patients with STS.

Taken together, researchers are initiating the deployment of digital pathology. Such machine learning‐based digital models may be potentially transformative for managing patients in a routine setting.

3. INNOVATIVE IMAGING TECHNIQUES TO IMPROVE THE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH SARCOMA

Besides an accurate histological diagnosis, imaging is fundamental to every step involved in managing patients with STS, including the initial referral to a sarcoma reference center, biopsy guidance, local and distant tumor staging, surgery planning, follow‐up, and response assessment [16]. Imaging provides a non‐invasive and global view of the tumor phenotype (or radiophenotype) that complements biopsy sample‐based assays. The commonly used prognostic nomogram SARCULATOR [9] and response evaluation criteria for STS (response evaluation criteria in solid tumors [RECIST v1.1]) [17] rely only on the simplest imaging feature, namely the longest tumor diameter, despite STS demonstrating various baseline radiological presentations and patterns of response under treatment.

However, the last few decades have witnessed the following development: (i) radiomics‐based approaches, (ii) quantitative multi‐parametric imaging enabling the non‐invasive assessment of tumor neo‐angiogenesis (through dynamic contrast‐enhanced [CE] magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), cell shape and density (through diffusion‐weighted imaging [DWI]), and metabolism (through 18F‐fluoro‐2‐deoxyglucose [18F‐FDG] positron emission tomography [PET] computed tomography [CT]), and (iii) novel radiolabeled antibodies in preclinical studies and phase I/II clinical trials [18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. The parallel innovation and increasing availability of AI algorithms for the classification, prognostication, clustering, and computer vision tasks have enabled capturing and integration complex datasets to achieve a virtual diagnosis and improve the prognostication and treatment response assessment.

3.1. Principle of radiomics approaches

The radiomics technique involves the extensive quantification of the tumor shape and texture based on any imaging modality beyond the conventional radiologist's depiction, using mathematical operators, such as histograms, gray level matrices, and wavelet or fractal analyses (Figure 1). Subsequently, hundreds of resulting numeric variables, termed radiomics features (RFs), are incorporated and mined using machine‐learning algorithms to develop predictive models aimed at improved tailoring of patient management [20, 23]. Radiomics approaches rely on complex pipelines, including the selection and quality control of imaging, homogenization of an imaging dataset to ensure comparability, manual or semi‐automatic segmentation of the volume of interest (for instance, the primitive tumor itself, its surrounding tissues, or metastases), RF extraction, exploratory data analysis, the use of technics to correct for imbalanced datasets, dimensionality reduction, training multiple machine‐learning algorithms using resampling methods (such as nested cross‐validation), and testing on novel original datasets to evaluate and select the best model objectively. This empirical process implies defining a metric for measuring the performance of the trained machine‐learning models depending on the final objective of the radiomics study and the distribution of the outcomes in the study population. For instance, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and accuracy, Harrell concordance index (c‐index) and root mean squared error are commonly encountered for binary classification, prognostication and regression problems, respectively [24]. Calibration curves and decision curve analysis are additional means to evaluate the radiomics models [20, 25]. Due to this complexity, radiomics approaches are qualified as “handcraft.” Recently, researchers have developed alternative RFs, termed deep‐learning RFs, using transfer learning, namely convolutional neural networks (CNNs) previously trained on the Imagenet dataset, such as Xception [26], VGG16 [27] and 19 [28], ResNet50 [29], or InceptionResNetV2 [30]. These deep‐learning RFs supposedly provide higher reproducibility than handcraft RFs [31]. Moreover, radiomics composite scores are often integrated into nomograms along with the clinical, biological, and histopathological features, which generally improve their predictive performances [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37].

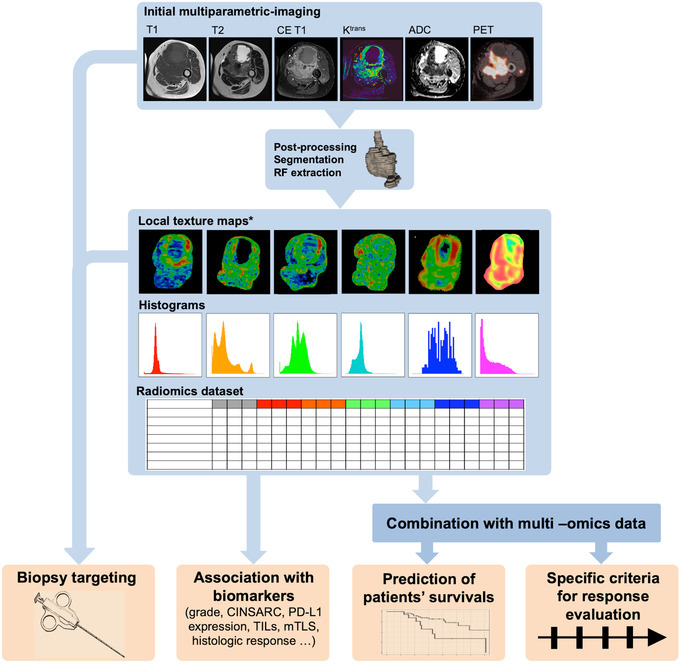

FIGURE 1.

The radiomics workflow and potentialities adapted to baseline multi‐parametric multimodal imaging of a patient with soft‐tissue sarcoma. A schematic illustration of the patient's journey, including image acquisition, analysis utilizing radiomics, and other clinical and biological variables to derive a predictive signature of the patient's outcome. High‐level statistical modeling involving machine learning is applied for disease classification, patient clustering, and individual risk stratification. Abbreviations: ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient, CE T1: contrast‐enhanced T1, CINSARC: complexity index in sarcoma signature, Ktrans: transfer constant, mTLS: mature tertiary lymphoid structure, PD‐L1: program death ligand 1, PET: (18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose) positron emission tomography, RF: radiomics features, and TILs: tumor infiltrative lymphocytes.

3.2. Applications of radiomics approaches for patients with STS

Since its emergence in the early 2010s, clinicians have commonly used radiomics in the field of STS. STS exhibits various radiological presentations with different patterns of heterogeneity that are barely explainable using human vocabulary and usual radiological qualitative or semi‐quantitative variables (also termed “semantic” features). Nonetheless, a key assumption behind radiomics is that these heterogeneity patterns reflect different subtypes of STS in terms of molecular features, treatment sensitivity, and prognosis [38].

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the major published sarcoma radiomics studies using CT and MRI. First, MRI‐based radiomics from conventional sequences (T1‐weighted imaging [WI], T2‐WI, and CE T1‐WI) and DWI have demonstrated high diagnostic performance in discriminating between benign soft‐tissue tumors and STS (accuracy: 0.65–0.93 and AUC: 0.77–0.97 for approximately 609 unique patients) [32, 39–42]. Some authors have obtained good results for the peculiar but routine issues of discriminating lipoma from liposarcomas (AUC: 0.8–0.98 and accuracy: 0.87–0.95) [43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48] and leiomyoma from uterine sarcoma (AUC: 0.83–0.96 and accuracy: 0.74–0.88) [49, 50, 51, 52, 53]. Second, radiomics approaches have successfully predicted the histologic grade (according to the French “Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer”) from pre‐treatment MRIs (AUC: 0.76–0.92, accuracy: 0.82–0.98 for approximately 1,080 unique patients) [31, 33‐35, 54, 55]. However, these authors used different definitions of high grade (i.e., grade II and III versus only grade III), and the grade was occasionally evaluated on biopsy samples, despite the possibility of grade underestimation and biased results [56, 57].

TABLE 1.

Summary of the main radiomics studies involving the initial diagnosis and staging of sarcoma

| First author | Year | Question | No. Of patients | Imaging modality | Results | Main limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uterine leiomyosarcoma versus leiomyoma | ||||||

| Gerges et al. [49] | 2018 | Discrimination of leiomyomas versus leiomyosarcomas | 68 patients from 1 cohort (17 leiomyosarcomas) | MRI (T1, T2, ADC) | Two independent predictors (age and mean T2 signal); AUC = 0.955§. | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; only one algorithm tested; no validation cohort; no comparisons with radiologists; no available code. |

| Nakagawa et al. [50] | 2019 | Discrimination of leiomyomas versus leiomyosarcomas with high signal intensities on T2. | 80 patients from 1 center (30 leiomyosarcomas) | MRI (T2) | Model using extreme gradient boosting; AUC = 0.93§; outperformed radiologists' prediction. | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; 2D ROIs; no reproducibility analysis; no validation cohort; no available code. |

| Xie et al. [51] | 2019 | Discrimination of uterine sarcoma and atypical leiomyoma | 78 patients from 1 center (29 leiomyosarcomas) | MRI (ADC) | Model using logistic regression; AUC = 0.830, accuracy = 0.74, Se = 0.76, Sp = 0.73§. | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; only one algorithm tested; no validation cohort; no available code. |

| Wang et al. [52] | 2021 | Discrimination of leiomyomas and malignant uterine mesenchymal tumors | 134 patients from 1 center (30 malignant tumors) divided into training and testing sets | MRI (T2) | Model using SVM and LASSO; AUC = 0.76; best performance obtained with a mixed model clinical‐radiomics model (AUC = 0.91), similar to senior radiologist (AUC = 0.90) | Retrospective; only one algorithm tested; no available code. |

| Dai et al. [53] | 2022 | Discrimination of uterine sarcoma and atypical leiomyoma | 172 patients from 1 center (86 malignant tumors) divided into training and testing sets | MRI (T2, ADC) | Model using Random Forests on clinical data and deep‐learning features; AUC = 0.96, accuracy = 0.88; outperformed models on deep‐learning features alone, handcrafted radiomics features (± clinical data) | Retrospective; only one algorithm tested; no comparisons with radiologists; no available code |

| Lipoma vs liposarcoma | ||||||

| Thornhill et al. [43] | 2014 | Discrimination of lipoma and LPS | 44 patients from 1 center (20 LPSs) | MRI (T1) | Model using linear discriminant analysis; AUC = 0.98, Se = 0.95, Sp = 0.87§; outperformed radiologists' predictions. | Inclusion of myxoid and de‐differentiated LPS; retrospective; no reproducibility analysis; no validation cohort; no available code |

| Vos et al. [44] | 2019 | Discrimination of lipoma and well‐differentiated LPS or ALT | 116 patients from 1 center (58 ALTs) | MRI (T1, T2) | Models combining multiple ML algorithms; AUC = 0.89, Se = 0.74, Sp = 0.88§; outperformed radiologists' prediction | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; no validation cohort; no available code |

| Pressney et al. [45] | 2020 | Discrimination of lipoma and well‐differentiated LPS or ALT | 60 patients from 1 center (30 ALTs) | MRI (PD, T1) | Score combining texture and radiological features; AUC = 0.8, Se = 0.9, Sp = 0.6§ | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; no machine‐learning algorithm; no resampling; no validation cohort; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Malinauskaite et al.[46] | 2020 | Discrimination of lipoma and LPS | 38 patients from 1 center (14 LPSs) | MRI (T1) | Model using SVM; AUC = 0.926, accuracy = 0.95, Se = 0.89, Sp = 1§; outperformed radiologists' prediction | Inclusion of myxoid and de‐differentiated LPS; retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no validation cohort; no available code. |

| Leporq et al. [47] | 2020 | Discrimination of lipoma and well‐differentiated LPS or ALT | 81 patients from 1 center (40 ALTs) | MRI (fat‐suppressed CE‐T1) | Model using SVM; AUC = 0.96, accuracy = 0.95; Se = 1, Sp = 0.9§ | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no validation cohort; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Yang et al. [48] | 2022 | Discrimination of lipoma and well‐differentiated LPS or ALT using deep‐learning‐feature or handcrafted radiomics analysis | 127 patients from 2 centers (58 ALTs) divided into training and testing sets | CT‐scan and MRI (T1, T2) | Nomogramm using clinical, biological and deep‐learning signature; AUC = 0.94, accuracy = 0.87, Se = 0.95, Sp = 0.78; outperformed radiomics and radiologists. | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous dataset; no synthetic/adversarial data; no available code. |

| Benign soft tissue tumors versus soft‐tissue sarcoma | ||||||

| Juntu et al. [39] | 2010 | Discrimination between benign and malignant STTs | 135 patients from 1 center (49 malignant tumors) | MRI (T1) | Model using SVM; AUC = 0.02, accuracy = 0.93, Se = 0.94, Sp = 0.91§; outperformed radiologists. | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; 2D square ROIs instead of ED VOIs; no reproducibility analysis; no validation cohort; no available code. |

| Martin‐Carreras et al. [40] | 2019 | Discrimination between myxoma and myxofibrosarcoma | 56 patients from 1 center (27 myxofibrosarcomas) | MRI (T1) | Model using random forests, AUC = 0.88, accuracy = 0.84, Se = 0.85, Sp = 0.83§. | Retrospective; T1 sequence not appropriate for myxoid tumor; no reproducibility analysis; no validation cohort; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Fields et al. [41] | 2021 | Discrimination between benign and malignant STTs | 128 patients from 1 center (92 malignant tumors) | MRI (T1, CE‐T1, T2, PD ± fat suppression) | Model using Adaboost on multiple sequences; AUC = 0.77, Se = 0.87, Sp = 0.34§; simpler model using random forests on fat suppressed T2 (AUC = 0.75§) | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; no validation cohort; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Lee et al. [42] | 2021 | Discrimination between benign and malignant STTs | 151 patients from 1 center (71 malignant tumors) divided into training and testing sets | MRI (ADC) | Model using random forest on radiomics, ADCminimal and ADCmean; AUC = 0.77‐0.81, accuracy = 0.65‐0.71, Se = 0.71‐0.83, Sp = 0.59 | Retrospective; no available code. |

| Yue et al. [32] | 2022 | Discrimination between benign and malignant STTs | 139 patients from 1 center (75 malignant tumors) divided into 3 cohorts | MRI (T2 with fat suppression, CE T1) | Nomogram model using radiomics scores build with LASSO logistic regression and clinical‐radiological variables; AUC = 0.95, accuracy = 0.87, Se = 0.81, Sp = 0.95 | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Grade | ||||||

| Corino et al. [54] | 2018 | Grading of STS using radiomics | 19 patients from 1 center (14 with grade 3 STS) | MRI (ADC) | Model using histogram‐based features; AUC = 0.87, accuracy = 0.98§ | Retrospective; very small and heterogeneous dataset; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; only one tested algorithm; no validation cohort; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Peeken et al. [33] | 2019 | Grading of STS using radiomics | 225 patients from 2 centers (157 patients with grade 2/3 STS) divided into training and testing sets | MRI (fat‐suppressed T2 and CE‐T1) | Model using penalized logistic regression; AUC = 0.76, accuracy = 0.83, Se = 0.9, Sp = 0.5; outperforms clinical model. Nomogram using T2 radiomics score and TNM staging better predicts OS than stage alone (c‐indices = 0.74 versus 0.69). | Retrospective; grade assessed on biopsy at risk of underestimation; splits depending on center at risk of center bias; no comparison with radiologists; no available code |

| Zhang et al. [55] | 2019 | Grading of STS using radiomics | 35 patients from 1 center (26 with grade 2‐3 STS) | MRI (fat suppressed T2) | Model using SVM; AUC = 0.92, accuracy = 0.88, Se = 0.92, Sp = 0.80§. | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; no validation cohort; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Yan et al. [34] | 2021 | Grading of STS using radiomics | 180 patients from 2 centers (87 with grade 3 STS) divided into training and testing sets | MRI (T1, fat‐suppressed T2) | Nomogram including radiomics score using LASSO logisitic regression; AUC = 0.88, accuracy = 0.82, Se = 0.84, Sp = 0.79; outperformed clinical‐radiological model; moderate performances for PFS prediction (c‐index = 0.58) | Retrospective; splits depending on center at risk of center bias; only one tested algorithm; no available code |

| Navarro et al. [31] | 2021 | Improvement in grade classification performances using deep‐learning features instead of handcrafted radiomics features | 306 patients from 2 centers (229 patients with grade 2‐3 STS) divided into training and testing sets | MRI (fat‐suppressed T2 and CE‐T1) | Model using deep learning on fat suppressed T2; AUC = 0.76, accuracy = 0.83, Se = 0.91, Sp = 0.40; similar as radiomics but more reproducible | Retrospective; grade assessed on biopsy at risk of underestimation; deep‐learning features assessed on a single 2D slice at risk of sampling bias; splits depending on center at risk of center bias; no synthetic data for deep learning; no comparison with radiologists; no available code |

| Yang et al. [35] | 2022 | Improvement in grade classification performances using deep‐learning features instead of handcrafted radiomics features | 540 patients from 1 center (309 with grade 2‐3 STS) divided into training and testing sets | MRI (T1, fat‐suppressed T2) | Nomogram including deep‐learning signature (ResNet50) using support vector machines; AUC = 0.87, accuracy = 0.83, Se = 0.85, Sp = 0.78; outperformed clinical and handcrafted radiomics models; correlated with overall survival | Retrospective; no synthetic data for deep learning; unclear management of 3D tumor volume in deep‐learning analysis; no comparison with radiologists; no available code |

NOTE.‐ Abbreviations: ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient, ALT: atypical lipomatous tumor, AUC: area under the ROC curve, CE: contrast‐enhanced, LASSO: least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, LPS: liposarcoma, ML: machine learning, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PD: proton density, PFS: progression‐free survival; Se: sensitivity, Sp: specificity, STS: soft tissue sarcoma, SVM: support vector machine. §: the text in italic corresponds to performances that were only evaluated on the training cohort and not on an independent test set, and thus, likely to be overestimated. Of note, only studies with multivariate analyses and CT‐scan or MRI are presented. For multiple publications from the same cohorts, we only present the largest and more impactful one.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the main radiomics studies involving the prognostication and the prediction of response to neoadjuvant treatment in sarcoma patients

| First author | Year | Question | No. Of patients | Imaging modality | Results | Main limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prognosis | ||||||

| Vallières et al. [58] | 2015 | Prediction of lung metastatic relapse in STS patients. Methods to optimize fusion of PET and MR imaging. Influence of processing on predictions. | 51 patients from the TCIA dataset | PET‐CT and MRI (T1, fat‐suppressed T2) | Model using logistic regression; AUC = 0.98, Se = 0.96, Sp = 0.93§. | Retrospective; only one algorithm tested; no comparison with radiologists; no validation cohort |

| Peeken et al. [59] | 2019 | Prognostication of STS using radiomics (LFS, MFS, OS). | 212 patients from 3 centers, divided into 1 training and 2 testing sets | CT‐scans | Models using gradient boosting to predict LFS (c‐index = 0.77), MFS (c‐index = 0.68‐0.73) and OS (c‐index = 0.59‐0.73); also models using random forests to predict grading (AUC = 0.64). Radiomics models outperformed clinical models for LFS. | Retrospective; use of CE and non‐CE CT‐scans; splits depending on center at risk of bias; only one algorithm tested; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Crombé et al. [60] | 2020 | Prediction of metastatic relapse at 2 years in patients treated with NAC; the influence of signal intensity harmonization methods on prediction. | 70 patients from 1 center divided into training and testing sets | MRI (T2) | Model using elasticnet logistic regression; AUC = 0.82, accuracy = 0.75; best performances reached with histogram matching method. | Retrospective; only one tested algorithm; no comparison with radiologists; no available code |

| Crombé et al. [61] | 2020 | Prediction of MFS in myxoid/round cells liposarcomas | 35 patients from 1 center | MRI (T2) | Model using LASSO Cox regression on radiological and radiomics features; c‐index = 0.93§ | Retrospective; heterogeneous patient management (± NAC); small dataset; only one algorithm tested; no validation cohort; no available code |

| Crombé et al. [65] | 2020 | Prediction of MFS in STS patients treated with NAC. Development of methods to quantify the intra‐tumoral heterogeneity in neo‐angiogenesis. | 50 patients from 1 center | MRI (T2, DCE‐MRI) | Best model using LASSO Cox regression and combination of radiological and radiomics features from T2 + DCE‐MRI; c‐index = 0.84§. Better performance with radiomics directly extracted from raw DCE‐MRI data than from parametric maps. | Retrospective; only one algorithm tested, no validation cohort; no available code |

| Yang et al. [62] | 2021 | Prediction of OS using radiomics after curative treatment. | 353 patients from 1 center, divided into training and testing sets. | CT‐scan | Models using random survival forests and radiomics, age, lymph node involvement, and FNCLCC grade, c‐index ≈ 0.80. | Retrospective; unknown contrast agent injection; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; no reproducibility analysis; no comparisons with radiologists and between models; no available code |

| Peeken et al. [63] | 2021 | Prediction of OS using radiomics. Comparison with conventional radiological analysis. | 179 patients from 2 centers, divided into training and testing sets | MRI (T1, fat‐suppressed T2) | Model using radiomics from T2, AJCC and age; c‐index = 0.73; outperformed other combinations of clinical, radiologic and radiomics features. | Retrospective; heterogenous patients’ management (± NART); splits depending on center at risk of center bias; no available code |

| Chen et al. [36] | 2021 | Prognostication of STS treated with NART using radiomics (MFS) | 62 patients from 1 center and TCIA | MRI (fat suppressed T2) | Nomogram using radiomics score (built with LASSO Cox regression), tumor size and location; c‐index = 0.78§; outperformed clinical stage and radiomics score alone. | Retrospective; no image post‐processing for heterogeneous datasets; only one tested algorithm; no validation cohort; no comparison with radiologists; no available code |

| Fadli et al. [64] | 2022 | Prognostication of STS using delta‐radiomics clusters assessing natural tumor evolution (LFS, MFS, OS) | 68 patients from 1 center | MRI (CE‐T1) | Unsupervised classification based on logarithmic changes in radiomics features before treatment beginning is an independent predictor of LFS, but not MFS or OS. | Retrospective; only one tested algorithm; no validation cohort |

| Liu et al. [37] | 2022 | Prediction of LFS using deep‐learning radiomics. Comparisons with handcraft radiomics features. | 282 patients from 3 centers, divided into training and testing sets | MRI (T1, T2, ± CE‐T1) | Nomogram using deep‐learning radiomics score, NCI, histology, Ki67 (c‐index = 0.77). Outperforms usual staging systems, but the best performance was reached by KI67 alone (c‐index = 0.76). | Retrospective; unclear management of ROIs (2D or 3D?) and multiple sequences; splits depending on center at risk of center bias; no synthetic data for deep learning; only one algorithm tested; no comparison with radiologists; no available code |

| Prediction of response to treatment | ||||||

| Crombé et al. [66] | 2019 | Prediction of histologic response (<10% viable cells on surgical specimen) following NAC in high‐grade STS using delta‐radiomics. | 65 patients from 1 center (16 good responders), divided into training and testing sets | MRI (T2) at baseline and after 2 out of 6 cycles | Model using random forests on radiomics and radiological features; AUC = 0.63, accuracy = 0.75, Se = 0.98, Sp = 0.28; outperforms RECIST v1.1. Systematic errors to predict response in STS with abundant necrosis and bleeding. | Retrospective; lack of consensus on the definition of histologic response; no comparison with Choi criteria; no available code. |

| Crombé et al. [67] | 2019 | Prediction of histologic response (<10% viable cells on surgical specimen) following NAC in high‐grade STS using radiomics from DCE‐MRI. Influence of temporal parameters of DCE‐MRI sequence on response prediction | 25 patients from 1 center (5 good responders), prospective cohort. | MRI (DCE‐MRI) at baseline | Model using logistic regression on radiomics; AUC = 0.90§. Best performance with sequence lasting 5 min at a temporal resolution of 6 sec. | Small dataset; lack of consensus on the definition of histologic response; only one tested algorithm; no validation cohort; no comparison with radiologists; no available code. |

| Gao et al. [68] | 2020 | Prediction of histologic response (<50% viable cells on surgical specimen) using radiomics(at baseline, after 3rd fraction and after NART) and delta radiomics | 30 patients from 1 center (unclear no. of good responders) | MRI (ADC) | Model using SVM and radiomics and delta‐radiomics assessed at the 3 time points; AUC = 0.91, accuracy = 0.92, Se = 0.90, Sp = 0.97§. | Retrospective; lack of consensus on the definition of histologic response; no validation cohort; no comparison with Choi criteria and radiologists; no available code. |

| Peeken et al. [69] | 2021 | Prediction of histologic response (<5% viable cells on surgical specimen) using radiomics (before and after NART) and delta‐radiomics. | 156 patients from 2 centers (16 good responders), divided into training and testing sets. | MRI (fat suppressed T2, CE‐T1) | Model using random forests on radiomics and delta‐radiomics; AUC = 0.75. Delta radiomics improve prediction compared to single timepoint radiomics alone. | Retrospective; heterogeneous patient management (± NAC); lack of consensus on the definition of histologic response; no comparison with RECIST, Choi criteria, or radiologists |

Abbreviations: ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient, AUC: area under the ROC curve, c‐index: Harrell concordance index, CE: contrast‐enhanced, DCE‐MRI: dynamic contrast‐enhanced MRI, LASSO: least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, LFS: local relapse‐free survival, MFS: metastatic relapse‐free survival, ML: machine learning, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NAC: neoadjuvant chemotherapy, NART: neoadjuvant radiotherapy, OS: overall survival, PD: proton density, PFS: progression‐free survival; Se: sensitivity, Sp: specificity, STS: soft tissue sarcoma, SVM: support vector machine. §: the text in italic corresponds to performances that were only evaluated on the training cohort and not on an independent test set, and thus, likely to be overestimated. Of note, only studies with multivariate analyses and CT‐scan or MRI are presented. For multiple publications from the same cohorts, we only present the largest and more impactful one.

Clinicians have applied radiomics to predict patient prognosis, predominantly metastatic relapse‐free survival (MFS), local relapse‐free survival (LFS), overall survival (OS), and the risk of presenting lung metastases following initial treatments (either curative surgery alone or neoadjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy followed by curative surgery). The resulting radiomics prognostic models demonstrated good to strong performances (c‐index: 0.77 for LFS, 0.84–0.93 for MFS, and 0.73–0.80 for OS) [36, 58–65]. Eventually, radiomics has demonstrated the ability to predict the histologic response following neoadjuvant treatments using baseline RFs and delta‐radiomics, which correspond to a quantitative change in RFs between two radiological evaluations. Despite variations in the definitions for the histological response across studies (<5%, <10%, and <50% of the viable tumor cells on surgical samples), all studies demonstrated significant associations between the radiomics models and response (AUC: 0.63–0.91 and accuracy: 0.75–0.92) [66, 67, 68, 69]. The major secondary findings were as follows: (i) radiomics approaches appeared to provide better predictions than conventional tools (RECIST v1.1 and semantic radiological analysis alone), (ii) delta‐radiomics improved performances compared with single timepoint radiomics, and (iii) models directly designed to predict prognosis were more effective than those initially designed to predict the grade [33, 66, 68, 69].

These encouraging results support the need to better incorporate quantitative information from medical imaging because the radiophenotype of STS is related to each clinically relevant outcome. However, no study has investigated the association between any imaging biomarker (including radiomics) and the gene expression profiles in STS (including the CINSARC signature) or their potential synergy with the circulating tumor DNA [70]. Eventually, combining multimodal multi‐parametric imaging and AI could enable performing a “virtual biopsy,” i.e., a comprehensive and non‐invasive assessment of the tumor's pathological, molecular and prognostic features in cases where an actual biopsy is rarely feasible or insufficiently contributive.

3.3. Current limitations to the clinical applications of radiomics and the means to overcome them

Researchers have to address several obstacles common to imaging biomarkers [71], namely biological correlations, reproducibility and repeatability of the radiomics model, feasibility in other centers, external validation, comparisons against the reference methods with a distinct added value, and prospective validation in decision‐making situations. Thus, no radiomics signature is currently in routine clinical use regardless of the cancer type.

However, implementing radiomics in the routine setting has several limitations, which the radiomics community is aware of and has endorsed several proposals to overcome. First, they have created an international collaboration, termed the Imaging Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IB, to standardize the methodology behind radiomics and the definitions of RFs, and provide several recommendations to perform distinct radiomics studies (https://ibsi.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) [72, 73]. Second, Lambin et al. [20] have proposed a score, termed the radiomics quality score (RQS), to quantify the quality of any radiomics study. The RQS consists of 16 items covering each study step, which can be used as support while designing a radiomics signature. Third, sharing databases with well‐labeled imaging datasets and open‐source codes to test the radiomics signatures would undeniably increase the confidence in radiomics and fill the translational gaps. The cancer imaging archive is the most famous of the initiatives to host freely available imaging datasets (https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/) [74]. A small sarcoma dataset with PET‐CT and conventional MRI is already present and included in radiomics studies; however, greater efforts are needed.

Moreover, the tedious and time‐consuming manual segmentations of the tumor volume and the lack of practical and user‐friendly applications for clinicians impose restrictions on radiomics. (Semi) automated segmentations using a deep‐learning U‐net CNN are expected to facilitate the segmentation step in the future [75]. Eventually, fully‐automated pipelines that rely on deep‐learning algorithms directly applied to the raw 3‐D images should be able to capture the information better, owing to numerous and more personalized features for sarcoma.

4. IMPROVING THE TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH STS THROUGH IMMUNOTHERAPY OF SARCOMAS

STS presents a unique treatment challenge because of the lack of improvement in the existing standard of care (such as doxorubicin) since the early 1970s [76]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been approved for more than 15 cancer indications; however, this is not the case for sarcomas [77]. Several biological aspects of STS suggest a strong rationale for immunotherapy as follows: (i) the presence of chromosomal translocations that result in unique fusion proteins, (ii) the high expression of tumor‐associated antigens, of which the group of cancer‐testis antigens, such as NY‐ESO‐1, are expressed by 80% of synovial sarcomas [78] and 90% of myxoid liposarcomas [79, 80], and partially (iii) the moderate frequency of genetic mutations (e.g., PIK3CA in 18% of myxoid liposarcomas, TP53 in 17% of pleomorphic liposarcomas, and NF1 in 11% of myxofibrosarcomas and 8% of pleomorphic liposarcomas). These aspects may represent foreign antigens that can be targeted either by the natural immune response or actively induced immune response through immunotherapy.

Naturally‐occurring immune infiltrates have been reported in several STS subtypes. Orui et al. [81] detailedly characterized the immune infiltrates in numerous STS subtypes with the detection of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells expressing granzyme B, thus indicative of their cytotoxic function; the dendritic cells were CD1a‐negative but CD83‐positive, thus indicating a mature phenotype. Furthermore, Tseng et al. [82] suggested an adaptive immune response with the presence of intratumoral lymphoid structures. In liposarcomas, CD8+ T cells appeared scattered throughout the tumor, whereas CD4+ T cells and CD20+ B cells were localized to these lymphoid structures. The presence of immune infiltrates in STS suggests the feasibility of immunotherapy for these subtypes.

4.1. Role of ICIs in patients with STS

Despite the recent success of ICIs, there are limited and controversial human data to support the efficacy of immunotherapy in STS across immunotherapy clinical trials conducted in patients with STS [83].

A non‐comparative randomized phase II study conducted on 85 patients with refractory STS compared the treatment with nivolumab versus nivolumab + ipilimumab, revealing a 5% response rate (RR) with nivolumab alone, whereas the combination displayed promising antitumor activity with a 16% RR [84]. Another phase II study, SARC028, demonstrated an RR of 40% for undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and 20% for de‐differentiated liposarcoma under pembrolizumab treatment [85]. In contrast, a phase II study conducted by the French Sarcoma Group demonstrated only one response among 50 evaluated STS patients treated with pembrolizumab plus oral cyclophosphamide [86].

We recently reported a pooled analysis of clinical trials investigating the efficacy of ICIs on sarcomas [87]. This study included 384 patients from nine clinical trials; of these patients, 153 (39.8%) received a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD‐1) or programmed cell death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) antagonist as a single agent. The overall objective response rate (ORR) was 15.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 8.6%–25.1%). However, it dropped to 9.8% upon excluding alveolar soft‐part sarcoma, an extremely rare sarcoma subtype displaying exquisite sensitivity to PD‐1/PD‐L1 monoclonal antibodies, from the analysis [88, 89].

Overall, all studies investigating ICIs included patients without applying any biomarker‐based selection strategy (Table 3). Researchers have observed anecdotal responses in some histological subtypes (e.g., undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas or de‐differentiated liposarcomas), which might be more sensitive to treatment [84, 85]. PD‐L1 expression, currently used as a biomarker for immunotherapy in several epithelial tumors (non‐small cell lung cancer, head and neck, and triple‐negative breast cancer), is not relevant for STS. An overall PD‐L1 expression of ≥1% in tumor cells was observed in >15% of the patients, without distinct correlation with the clinical benefits [87]. Moreover, the tumor mutation burden was low, with a median burden of fewer than two mutations/Mb across all histological subtypes [90].

TABLE 3.

Clinical trials investigating immunotherapy in patients with soft‐tissue sarcoma

| Trial | Population / Histotypes | Overall Response Rate | Median progression‐free survival | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Treatment | Biomarker | Overall | LMS | LPS | UPS | Synovial sarcoma | ASPS | Overall | LMS | LPS | UPS | Synovial sarcoma | ASPS | ||||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | ||||||||||||||||||

| SARC028 | Initial cohort (Tawbi et al. 2017) | Multi‐arm, non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Pembrolizumab 200mg flat dose q3w |

Four cohorts of 10 patients in each histotype: LMS, DDLPS, UPS, synovial sarcoma |

– | 17.5% | 0% | 20% | 40% | 0% | – | 15w | 25w | 30w | 7w | – | ||

| Expansion cohorts (Burgess, ASCO 2019) | Pembrolizumab 200mg flat dose q3w | Two cohorts: 39 DDLPS and 40 UPS | – | – | – | 10% | 23% | – | – | – | 2M | 3M | – | – | ||||

| Alliance A091401 | Initial cohort (D'Angelo et al., 2018) | Multi‐arm, non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Nivolumab 3mg/kg q2w | 42 STS | – | 5% | – | – | – | – | – | 1.7M | – | – | – | – | – | |

|

Nivolumab 3mg/kg + ipilimumab 1mg/kg q3w for 4 cycles followed by nivolumab 3mg/kg q2w |

41 STS | – | 16% | – | – | – | – | – | 4.1M | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Expansion cohorts (Chen et al., 2020) | Nivolumab 3mg/kg q2w | 15 DDLPS & 13 UPS | – | – | – | 6.7% | 7.7% | – | – | – | – | 4.6M | 1.5M | – | – | |||

|

Nivolumab 3mg/kg + ipilimumab 1mg/kg q3w for 4 cycles followed by nivolumab 3mg/kg q2w |

14 DDLPS & 14 UPS | – | – | – | 14.3% | 28.6% | – | – | – | 5.5M | 2.7M | |||||||

| Somaiah, ASCO 2020 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial |

Durvalumab 1500mg + tremelimumab 75mg q4w for 4 cycles followed by durvalumab alone |

57 soft‐tissue sarcomas: 6 LPS, 5 UPS, 5 synovial sarcoma, 10 ASPS and others |

– | 14.3% | – | – | – | – | – | 2.8M | – | 2M | 1.8M | 7.46M | 34.23M | ||

| D'Angelo, Nature Commun 2022 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Bempegaldesleukin (CD122 agonist) 6μg/kg + nivolumab 360mg q3w | 77 sarcomas | – | 11.7% | 10% | 0% | 20% | – | 25% | – | 1.8M | 3.9M | 2.4M | – | 2.6M | ||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors + chemotherapy | ||||||||||||||||||

| PembroSarc | Toulmonde, JAMA Oncol 2018 | Multi‐arm, non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial |

Cyclophosphamide 50mg twice daily 1 week on/1 week off + Pembrolizumab 200mg q3w |

41 STS | All‐comers | 2.4% | 0% | – | 0% | – | – | 1.4M | 1.4M | – | 1.4M | – | – | |

| Italiano, Nature Med 2022 | 30 STS | TLS positive tumors | 30% | – | – | – | – | – | 4.1M | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Pollack, JAMA Oncol 2020 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Doxorubicin (45mg/m2 and 75mg/m2) + pembrolizumab 200mg q3w | 37 STS | – | 19% | 0% | – | – | – | – | 8.1M | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Livingston, CCR 2021 | Non‐randomized, Phase 1/2 trial | Doxorubicin (60mg/m2 with escalation to 75mg/m2) + pembrolizumab 200mg q3w | 30 STS | – | 36.7% | 40% | 28.6% | 100% | – | – | 5.7M | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| SAINT | Gordon, ASCO 2022 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Trabectedin (1.2mg/m2) q3w + nivolumab 3mg/kg q3w + ipilimumab 1mg/kg q12w | 88 STS | – | 21.6% | – | – | – | – | – | 7M | – | – | – | – | – | |

| TRAMUNE | Toulmonde, Clin Cancer Res 2022 | Non‐randomized, Phase Ib trial | Trabectedin (1.2mg/m2) + durvalumab 1120mg q3w | 16 STS | – | 7% | – | – | – | – | <3M | – | – | – | – | – | ||

|

Nathenson, ASCO 2020 George, CTOS 2021 |

Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Eribulin (1.4mg/m2) D1, D8 + pembrolizumab 200mg q3w | 20 LPS, 19 LMS, 18 UPS/other sarcomas | – | 17.5% | 5.3% | 15% | – | – | – | – | 2.5M | 6.2M | – | – | – | ||

| Rosenbaum, ASCO 2022 | Non‐randomized, Phase 1/2 trial | Gemcitabin (900mg/m2 D1, D8) + Docetaxel (75mg/m2 D8) retifanlimab (anti‐PD‐1, 210mg or 375mg D1) q3w | 13 STS with 6 LMS | – | 33.3% | – | – | – | – | – | >5.5M | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| GALLANT | Adnan, ASCO 2022 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Gemcitabine (600mg/m2 D1, D8), doxorubicin (18mg/m2 D1, D8), docetaxel (25mg/m2 D1, D8) + nivolumab 240mg q2w | 43 STS | – | 18.6% | – | – | – | – | – | >4.6M | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors + antiangiogenics | ||||||||||||||||||

| Wilky, Lancet Oncol 2020 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Axitinib 5mg twice daily + pembrolizumab 200mg q3w | 33 STS with 12 ASPS | – | 25% | – | – | – | – | 54.5% | 4.7M | – | – | – | – | 12.4M | ||

| IMMUNOSARC | Martin‐Broto, JITC 2020 |

Non‐randomized, Phase Ib/2 trial |

Sunitinib 37.5mg daily for 2weeks followed by 25mg daily + nivolumab 3mg/kg q2w | 60 STS | – | 21.7% | – | – | – | – | – | 5.6M | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors + Oncolytic viruses | ||||||||||||||||||

| TNT | Chawla, ASCO 2021 |

Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial |

Nivolumab (3mg/kg q2w) + trabectedin (1.2mg/m2 q3w) + TVEC (intratumoral q2w) | 36 STS | – | 8.3% | – | – | – | – | – | 5.5M | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Kelly, JAMA Oncol 2020 |

Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial |

Pembrolizumab (200mg) + TVEC (intratumoral) q3w | 20 STS | – | 35% | – | – | – | – | – | 3.9M | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors in specific histotypes | ||||||||||||||||||

| Maki, Sarcoma 2013 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Ipilimumab 3mg/kg q3w | 6 synovial sarcomas | – | – | – | – | – | 0% | – | – | – | – | – | 1.85 months | – | ||

| Ben‐Ami, Cancer 2017 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Nivolumab 3mg/kg q2w | 12 uterine LMS | – | – | 0% | – | – | – | – | – | 1.8 months | – | – | – | – | ||

| Acsé Pembrolizumab | Blay, ASCO 2021 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Pembrolizumab 200mg q3w |

Rare sarcomas (incidence<0.2/100.000): 34 chordomas, 14 ASPS, 8 DSRCT, 11 SMARCA4‐malignant rhabdoid tumors & 31 others |

– | 15.3% | – | – | – | – | 50% | 2.75 months | – | – | – | – | 7.5 months | |

| OSCAR | Kawai et al, CTOS 2020 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Nivolumab 240mg q2w | 11 clear cell sarcomas and 14 ASPS | – | 4% | – | – | – | – | 7.1% | 4.9 months | – | – | – | – | 6 months | |

| Gxplore‐005 | Shi, Clin Cancer Res 2020 | Non‐randomized, Phase 2 trial | Geptanolimab (anti‐PD‐1, 3mg/kg q2w) | 37 ASPS | – | – | – | – | – | – | 37.8% | – | – | – | – | – | 6.9 months | |

Abbreviations: LMS, leiomyosarcoma; LPS, liposarcoma; UPS, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma; ASPS, alveolar soft part sarcoma; DDLPS, dedifferentiated liposarcoma; STS, soft tissue sarcoma; M, months; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology

For an in‐depth investigation of the therapeutic impact of ICIs in patients with sarcoma and its correlation with the sarcoma microenvironment, we conducted an extensive analysis of the immune landscape of sarcomas [91]. By analyzing transcriptomic data from more than 600 STSs, we identified a subgroup of sarcomas classified as “immune high,” characterized by an elevated expression of a B cell‐related (BCR) gene signature, which was predictive of survival, independent of the level of CD8+ T cell infiltration [91]. In addition, an immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis revealed that this class of sarcoma is characterized by the presence of intratumoral tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs) [91]. TLSs are ectopically formed aggregates of B‐cell follicles, follicular dendritic cells, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which play a critical role in anticancer immunity in several tumor types [92]. Moreover, a retrospective analysis of the biopsies from 47 patients included in the SARC028 study indicated that the BCR gene signature was highly predictive of the response to the anti‐PD‐1 antibody pembrolizumab, thereby suggesting that the presence of TLSs may serve as a robust biomarker for immunotherapy customization in patients with sarcoma [91].

Subsequently, we amended the PEMBROSARC study (NCT02406781; sponsor: Institut Bergonié, Bordeaux, France) to include a recent cohort, which was based on the presence of TLSs to investigate the efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced sarcomas, characterized by the presence of this potential biomarker [93]. We included 35 patients with TLS‐positive advanced STS in this study. The 6‐month non‐progression rate and ORRs were 40% (95% CI: 22.7%–59.4%) and 30% (95% CI: 14.7%–49.4%), respectively, compared with 4.9% (range: 0.6%–16.5%) and 2.4% (95% CI: 0.1%–12.9%), respectively, in previous cohorts of the PEMBROSARC study, which included all comers [86]. Interestingly, a retrospective analysis of the tumor samples from the patients included in the all‐comer cohort displayed that all except one patient harbored a TLS‐negative sarcoma, thus suggesting that patient selection based on the presence of TLSs would be an efficient approach toward the identification of an appropriate population for sarcoma‐targeted immunotherapy [93].

TLSs are observed in approximately 20% of the patients with STS and can be identified in almost all histological subtypes, despite the high proportion of TLS‐positive cases in some subtypes (e.g., de‐differentiated liposarcoma versus leiomyosarcoma) [92]. The TLS status can be assessed by real‐life samples, including small biopsies. Larger samples are more sensitive to detect TLS, which predominate at the tumor front; however, the biopsy samples can be efficiently used to screen TLSs [94]. We recommend a double CD20/CD23 staining to detect TLSs, which offers the advantage of simultaneously ensuring the presence of TLSs comprising B cells (CD20+) and the co‐localization of follicular dendritic cells (CD23+).

The identification of a subgroup of sarcoma characterized by the presence of intratumoral TLSs represents an important step towards the development of immunotherapy for patients with sarcoma; nonetheless, researchers are yet to address at least two major questions before emphasizing immunotherapy as a novel and efficient standard of care in patients with STS as follows: how to improve the response rate of TLS‐positive sarcomas and how to make immunotherapy an efficient approach in TLS‐negative sarcomas?

4.2. Improving the response rates to ICIs in TLS‐positive sarcomas

Simultaneously targeting different immune checkpoints is a potential approach to improve immunotherapy efficacy in patients with TLS+ sarcomas. TLS+ sarcomas are characterized by the increased expression of immune checkpoints besides PD‐1, such as cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA‐4), TIGIT or lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3) [91]. LAG3 (CD223) is the third immune checkpoint recently targeted in clinical practice and has garnered considerable interest and scrutiny [95]. LAG3 upregulation is required to control the overt activation and prevent the onset of autoimmunity. However, persistent antigen exposure in the tumor microenvironment (TME) results in sustained LAG3 expression, thus contributing to a state of exhaustion that manifests as impaired proliferation and cytokine production. The exact signaling mechanisms downstream of LAG3 and their interplay with other immune responses remain largely unknown. However, the synergy between LAG3 and PD‐1 in multiple settings, coupled with the contrasting intracellular cytoplasmic domain of LAG3, compared with the other immune responses, highlights the potential uniqueness of LAG3. Our research findings [91] and others [96] have demonstrated the strong upregulation of LAG3 in inflamed sarcomas. LAG3+ tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were observed in approximately two‐thirds of complex genomic sarcomas, and their expression was strongly correlated with disease outcomes [96]. Based on this rationale, a clinical trial is currently investigating the activity and safety of nivolumab combined with relatlimab, a monoclonal antibody that targets LAG3, versus nivolumab alone, in patients with STS (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04095208).

4.3. Successful immunotherapy in 80% of the patients with TLS‐negative sarcoma

Investigating combination strategies with ICIs to transform “cold tumors” into “hot tumors” and improve their sensitivity to ICIs is key to addressing this issue. Several clinical trials are currently investigating the combinations of ICIs with different classes of agents, namely chemotherapy, radiotherapy, toll‐like receptor agonists, anti‐angiogenics, oncolytic viruses, and epigenetics, that enable the conversion of “cold tumors” to “inflamed tumors”. To better understand the impact of such combinations on the TME, investigators and patients should realize the importance of sequential blood and tissue sampling or a randomized design to avoid any bias in data interpretation. A recent study investigated the combination of doxorubicin and pembrolizumab in patients with advanced STS [97]. The RR (13%) and PFS observed in this phase II study were similar to those observed when doxorubicin was used as a single agent [97]. Unfortunately, the lack of sequential tumor biopsies and randomization precludes any conclusion about the impact of the TME combination and correlations with the clinical benefits, thereby limiting the value of the study in terms of an improvement of knowledge for the scientific community.

4.4. Immunotherapy for sarcomas beyond ICIs

Besides ICIs, researchers have investigated other immunotherapy strategies in patients with STS. For this review, we focused on T‐cell receptor (TCR) gene‐modified cells, which are more advanced in terms of clinical development. This therapeutic approach is based on the ex vivo expansion of autologous T cells following their genetic engineering to express a novel TCR that recognizes specific tumor antigens. Ongoing clinical trials investigating such TCR‐based therapies in patients with STS use TCRs directed at validated cancer germline antigens, i.e., MAGE‐A4 and NY‐ESO‐1, expressed in particular STS subtypes, including myxoid/round cell liposarcoma (MRCLS) and synovial sarcomas.

Ramachandran et al. [98] reported that the adoptive transfer of NY‐ESO‐1c259 T cells in 42 patients with synovial sarcoma (NCT01343043) was associated with an ORR of 35.7% (15 patients; 1 CR and 14 PR cases) by RECIST. D'Angelo et al. [99] demonstrated that the persistence and functionality of these adoptively transferred T cells were associated with sustained responses in a significant proportion of patients. Moreover, treatment with an autologous T‐cell therapy targeting NY‐ESO‐1 displayed antitumor activity up to 40% ORR and long median PFS, with an acceptable safety profile in a study that enrolled 23 patients with advanced and metastatic MRCLS [100]. Similarly, preliminary data suggested that afamitresgene autoleucel, a genetically modified autologous melanoma‐associated antigen 4 (MAGE A4) specific T cell therapy, could induce a prolonged response in heavily pre‐treated patients with advanced MAGE‐A4‐expressing SS and MRCLS [101].

Despite promising preliminary results, the development of TCR‐based adoptive cell therapies for treating patients with STS is associated with several challenges, including those associated with manufacturing and processing of the final TCR product, patient selection, optimizing lymphodepletion conditioning, and managing adverse events. Ongoing and future studies will determine the role of TCR therapy in patients with STS.

5. IMPLEMENTING RADIOMICS TO PREDICT THE BENEFITS OF IMMUNOTHERAPY IN PATIENTS WITH STS

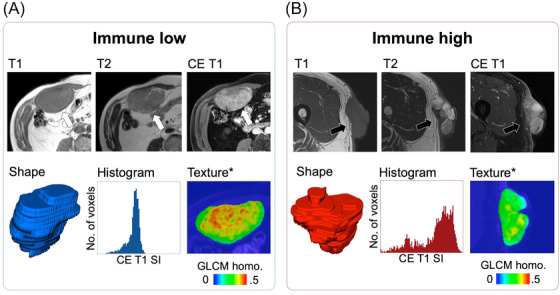

The development of immunotherapy for sarcomas is not an aspect of histology (except for alveolar soft‐part sarcoma) but rather that of the TME. Future studies investigating immunotherapy strategies in sarcomas should incorporate at least the presence of TLS as a stratification factor in their design, besides including a strong translational program that will allow for a better understanding of the determinants involved in sensitivity and treatment resistance. Moreover, investigators should explore innovative methods to evaluate the clinical benefits associated with a particular treatment. To date, no STS‐specific imaging biomarker has been validated to predict the sensitivity of STS to ICIs and the risk of immunotherapy‐related adverse events and to improve the early response evaluation during treatment with ICIs. More than 50 studies have investigated the association between imaging and immune phenotypes or responses to ICIs in solid tumors [102]. Immune‐inflamed tumors demonstrate distinct TMEs with dense CD8+ TILs (stimulated by the accumulation of tumor mutation burden and neoantigens) and a high expression of PD‐L1; therefore, it should be translated to conventional imaging, radiomics, and molecular imaging [103]. Solid tumors with a higher proportion of TILs appear to be better circumscribed, with a rounder shape, larger size, various apparent diffusion coefficient values depending on the cancer histology, increased heterogeneity and irregularity on CT scans, and higher homogeneous contrast enhancement on MRI [104, 105]. An exploratory study by Toulmonde et al. [106] specifically involving STS identified a radiomics signature combining nine RFs that distinguished immune‐high and ‐low undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas in a small hypothesis‐generating cohort of 14 patients (accuracy = 93%). Figure 2 depicts an example of the radiomics application to distinguish immune‐high and immune‐low STSs.

FIGURE 2.

Radiomics to distinguish between immune low (A) and high UPS (B) according to Toulmonde et al. [106]. On contrast‐enhanced MRI, immune high UPS (black arrows) is characterized by a more heterogeneous aspect than immune low UPS (white arrows), captured through a combination of nine radiomics features, all related to heterogeneity. *The local texture map corresponds to the GLCM homogeneity (homo.) calculated on a small tile (or kernel) of 3 × 3 voxels. Higher values correspond to greater local homogeneity. Abbreviations: CE: contrast‐enhanced; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; No.: number; SI: signal intensity; UPS: undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas; GLCM: gray‐level co‐occurrence matrix. This figure is original.

Multicentric retrospective cohorts have demonstrated the correlations between the radiomics patterns on CE‐CT scans and response to ICIs, including multiple solid tumors (AUC = 0.83 for predicting ICI response in a non‐small cell lung cancer cohort in the study by Trebeschi et al. [105] and multivariate hazard ratio for high radiomics score group = 0.52 [0.34–0.79] in the study by Sun et al. [107]). Researchers should investigate the validation and adaptation of these radiomics scores for patients with STS treated with ICIs.

The early prediction of the response to an ICI may be enhanced using radiomics and molecular imaging. RECIST has been replaced by immune‐RECIST to reduce the confusion between true progression and pseudo‐progression. Likewise, the PET response criteria for solid tumors (PERCIST) have been replaced by immune‐PERCIST and PET response evaluation criteria for immunotherapy [108, 109, 110]. However, researchers have evaluated neither their added value in terms of predicting the OS or PFS in patients with STS undergoing ICI therapy nor that of delta‐radiomics approaches.

Eventually, 18F‐FDG has proven to lack the specificity and consistency for robustly discriminating TMEs associated with distinct outcomes under ICI treatment; therefore, investigators are designing novel tracers with monoclonal antibodies (or antibody fragments) targeting PD‐1 (such as Zirconium‐89‐nivolumab), PD‐L1 (such as 18F‐BMS‐986192 adnectin), CTLA‐4 (such as Zirconium‐89‐ipilimumab), CD8+ lymphocytes (such as Zirconium‐89‐Df‐IAB22M2C), or interleukin‐2 receptor (such as Technetium‐99‐IL2), under the name of immuno‐PET [111, 112, 113]. Beyond preclinical patient‐derived xenograft studies, ongoing clinical trials have been evaluating the tolerance, distribution, and interest of these tracers in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer, thus revealing correlations with tumors expressing PD‐L1 ≥50% on IHCs, high numbers of TILs, and the response to anti‐PD‐1 immunotherapy [114, 115, 116]. However, none of these methods have been attempted in patients with STS or STS xenografts.

6. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, innovative diagnostic technologies, such as digital pathology, and quantitative multimodal multi‐parametric imaging, including radiomics, can enhance the diagnosis, prognosis assessment, and treatment monitoring of STS. Further studies are required to evaluate the impact of their implementation in routine practice. Recent research has revealed the potential for efficient immunotherapies against sarcoma. While capturing the heterogeneity of STS is challenging, ICI‐based regimens are likely the strategy for patients with TLS‐positive tumors. Clinicians should implement innovative approaches based on a stringent characterization of the STS microenvironment in patients with TLS‐negative tumors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Concept and design: AI; drafting of the manuscript: AC and AI; and supervision: AI. All authors participated in writing and revising this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

AI: Research grant: AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS Merck, MSD, and Roche. Advisory Board: AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen Cilag, Lilly, Roche, Blueprint medicines, and PharmaMar. AC: No competing interests.

FUNDING

Agence Nationale de la Recherche (RHU CONDOR).

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Crombé A, Roulleau‐Dugage M, Italiano A. The diagnosis, classification, and treatment of sarcoma in this era of artificial intelligence and immunotherapy. Cancer Commun. 2022;42:1288–1313. 10.1002/cac2.12373

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1. Italiano A, Mathoulin‐Pelissier S, Cesne AL, Terrier P, Bonvalot S, Collin F, et al. Trends in survival for patients with metastatic soft‐tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2011;117(5):1049‐1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Callegaro D, Miceli R, Bonvalot S, Ferguson PC, Strauss DC, van Praag VVM, et al. development and external validation of a dynamic prognostic nomogram for primary extremity soft tissue sarcoma survivors. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;17:100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pervaiz N, Colterjohn N, Farrokhyar F, Tozer R, Figueredo A, Ghert M. A systematic meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft‐tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2008;113(3):573‐581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Issels RD, Lindner LH, Verweij J, Wust P, Reichardt P, Schem B‐C, et al. Neo‐adjuvant chemotherapy alone or with regional hyperthermia for localised high‐risk soft‐tissue sarcoma: a randomised phase 3 multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(6):561‐570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Italiano A, Le Cesne A, Mendiboure J, Blay J‐Y, Piperno‐Neumann S, Chevreau C, et al. Prognostic factors and impact of adjuvant treatments on local and metastatic relapse of soft‐tissue sarcoma patients in the competing risks setting. Cancer. 2014;120(21):3361‐3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gronchi A, Ferrari S, Quagliuolo V, Broto JM, Pousa AL, Grignani G, et al. Histotype‐tailored neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus standard chemotherapy in patients with high‐risk soft‐tissue sarcomas (ISG‐STS 1001): an international, open‐label, randomised, controlled, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):812‐822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Italiano A, Stoeckle E. Role of perioperative chemotherapy in soft‐tissue sarcomas: It's time to end a never‐ending story. Eur J Cancer. 2018;97:53‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rothermundt C, Fischer GF, Bauer S, Blay J‐Y, Grünwald V, Italiano A, et al. Pre‐ and Postoperative Chemotherapy in Localized Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma: A European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Expert Survey. Oncologist. 2018;23(4):461‐467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Callegaro D, Miceli R, Bonvalot S, Ferguson P, Strauss DC, Levy A, et al. development and external validation of two nomograms to predict overall survival and occurrence of distant metastases in adults after surgical resection of localised soft‐tissue sarcomas of the extremities: a retrospective analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17(5):671‐680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crombé A, Spalato‐Ceruso M, Michot A, Laizet Y, Lucchesi C, Toulmonde M, et al. Gene expression profiling improves prognostication by nomogram in patients with soft‐tissue sarcomas. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2022;42(6):563‐566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang S, Yang J, Fong S, Zhao Q. Artificial intelligence in cancer diagnosis and prognosis: Opportunities and challenges. Cancer Lett. 2020;471:61‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Courtiol P, Maussion C, Moarii M, Pronier E, Pilcer S, Sefta M, et al. Deep learning‐based classification of mesothelioma improves prediction of patient outcome. Nat Med. 2019;25(10):1519‐1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saillard C, Schmauch B, Laifa O, Moarii M, Toldo S, Zaslavskiy M, et al. Predicting Survival After Hepatocellular Carcinoma Resection Using Deep Learning on Histological Slides. Hepatology. 2020;72(6):2000‐2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boehm KM, Khosravi P, Vanguri R, Gao J, Shah SP. Harnessing multimodal data integration to advance precision oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(2):114‐126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foersch S, Eckstein M, Wagner D‐C, Gach F, Woerl A‐C, Geiger J, et al. Deep learning for diagnosis and survival prediction in soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(9):1178‐1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gronchi A, Miah AB, Dei Tos AP, Abecassis N, Bajpai J, Bauer S, et al. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO‐EURACAN‐GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(11):1348‐1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology. 2016;278(2):563‐577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abousaway O, Rakhshandehroo T, Van den Abbeele AD, Kircher MF, Rashidian M. Noninvasive Imaging of Cancer Immunotherapy. Nanotheranostics. 2021;5(1):90‐112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, Peerlings J, de Jong EEC, van Timmeren J, et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(12):749‐762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crombé A, Matcuk GR, Fadli D, Sambri A, Patel DB, Paioli A, et al. Role of Imaging in Initial Prognostication of Locally Advanced Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Acad Radiol. 2022;S1076‐6332(22)00250‐1 (online ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spinnato P, Kind M, Le Loarer F, Bianchi G, Colangeli M, Sambri A, et al. Soft Tissue Sarcomas: The Role of Quantitative MRI in Treatment Response Evaluation. Acad Radiol. 2021;S1076‐6332(21)00360‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Limkin EJ, Sun R, Dercle L, Zacharaki EI, Robert C, Reuzé S, et al. Promises and challenges for the implementation of computational medical imaging (radiomics) in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(6):1191‐1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, Gerds T, Gonen M, Obuchowski N, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for some traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):128‐138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(6):565‐574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chollet F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. 2017. F.Chollet, Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2017;1800‐1807.

- 27. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large‐Scale Image Recognition. 2015. Available from: https://arXivorg/abs/14091556

- 28. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2016;770‐778.

- 29. Szegedy C, Vanhoucke V, Ioffe S, Shlens J, Wojna, Z . Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2016;2818‐2826

- 30. Russakovsky O, Deng J, Su H, Krause J, Satheesh S, et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int J Comput Vis 2015;115:211‐252. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Navarro F, Dapper H, Asadpour R, Knebel C, Spraker MB, Schwarze V, et al. Development and External Validation of Deep‐Learning‐Based Tumor Grading Models in Soft‐Tissue Sarcoma Patients Using MR Imaging. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(12):2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yue Z, Wang X, Yu T, Shang S, Liu G, Jing W, et al. Multi‐parametric MRI‐based radiomics for the diagnosis of malignant soft‐tissue tumor. Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;91:91‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peeken JC, Spraker MB, Knebel C, Dapper H, Pfeiffer D, Devecka M, et al. Tumor grading of soft tissue sarcomas using MRI‐based radiomics. EBioMedicine. 2019;48:332‐340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yan R, Hao D, Li J, Liu J, Hou F, Chen H, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging‐Based Radiomics Nomogram for Prediction of the Histopathological Grade of Soft Tissue Sarcomas: A Two‐Center Study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;53(6):1683‐1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yang Y, Zhou Y, Zhou C, Zhang X, Ma X. MRI‐Based Computer‐Aided Diagnostic Model to Predict Tumor Grading and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Soft Tissue Sarcoma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022. (online ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen S, Li N, Tang Y, Chen B, Fang H, Qi S, et al. Radiomics Analysis of Fat‐Saturated T2‐Weighted MRI Sequences for the Prediction of Prognosis in Soft Tissue Sarcoma of the Extremities and Trunk Treated With Neoadjuvant Radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2021;11:710649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu S, Sun W, Yang S, Duan L, Huang C, Xu J, et al. Deep learning radiomic nomogram to predict recurrence in soft tissue sarcoma: a multi‐institutional study. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(2):793‐805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gillies RJ, Anderson AR, Gatenby RA, Morse DL. The biology underlying molecular imaging in oncology: from genome to anatome and back again. Clin Radiol. 2010;65(7):517‐521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Juntu J, Sijbers J, De Backer S, Rajan J, Van Dyck D. Machine learning study of several classifiers trained with texture analysis features to differentiate benign from malignant soft‐tissue tumors in T1‐MRI images. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31(3):680‐689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martin‐Carreras T, Li H, Cooper K, Fan Y, Sebro R. Radiomic features from MRI distinguish myxomas from myxofibrosarcomas. BMC Med Imaging. 2019;19(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fields BKK, Demirjian NL, Hwang DH, Varghese BA, Cen SY, Lei X, et al. Whole‐tumor 3D volumetric MRI‐based radiomics approach for distinguishing between benign and malignant soft tissue tumors. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(11):8522‐8535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee SE, Jung J‐Y, Nam Y, Lee S‐Y, Park H, Shin S‐H, et al. Radiomics of diffusion‐weighted MRI compared to conventional measurement of apparent diffusion‐coefficient for differentiation between benign and malignant soft tissue tumors. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thornhill RE, Golfam M, Sheikh A, Cron GO, White EA, Werier J, et al. Differentiation of lipoma from liposarcoma on MRI using texture and shape analysis. Acad Radiol. 2014;21(9):1185‐1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vos M, Starmans MPA, Timbergen MJM, van der Voort SR, Padmos GA, Kessels W, et al. Radiomics approach to distinguish between well differentiated liposarcomas and lipomas on MRI. Br J Surg. 2019;106(13):1800‐1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pressney I, Khoo M, Endozo R, Ganeshan B, O'Donnell P. Pilot study to differentiate lipoma from atypical lipomatous tumour/well‐differentiated liposarcoma using MR radiomics‐based texture analysis. Skeletal Radiol. 2020;49(11):1719‐1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Malinauskaite I, Hofmeister J, Burgermeister S, Neroladaki A, Hamard M, Montet X, et al. Radiomics and Machine Learning Differentiate Soft‐Tissue Lipoma and Liposarcoma Better than Musculoskeletal Radiologists. Sarcoma. 2020;2020:7163453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leporq B, Bouhamama A, Pilleul F, Lame F, Bihane C, Sdika M, et al. MRI‐based radiomics to predict lipomatous soft tissue tumors malignancy: a pilot study. Cancer Imaging. 2020;20(1):78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yang Y, Zhou Y, Zhou C, Ma X. Novel computer aided diagnostic models on multimodality medical images to differentiate well differentiated liposarcomas from lipomas approached by deep learning methods. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17(1):158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gerges L, Popiolek D, Rosenkrantz AB. Explorative Investigation of Whole‐Lesion Histogram MRI Metrics for Differentiating Uterine Leiomyomas and Leiomyosarcomas. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2018;210(5):1172‐1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nakagawa M, Nakaura T, Namimoto T, Iyama Y, Kidoh M, Hirata K, et al. Machine Learning to Differentiate T2‐Weighted Hyperintense Uterine Leiomyomas from Uterine Sarcomas by Utilizing Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Quantitative Imaging Features. Academic Radiology. 2019;26(10):1390‐1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]