Abstract

Telehealth reduces disparities that result from physical disabilities, difficulties with transportation, geographic barriers, and scarcity of specialists, which are commonly experienced by individuals with spinal cord injuries and disorders (SCI/D). The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been an international leader in the use of virtual health. The VA’s SCI/D System of Care is the nation’s largest coordinated system of lifelong care for people with SCI/D and has implemented the use of telehealth to ensure that Veterans with SCI/D have convenient access to their health care, particularly during the restrictions that were imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Telehealth, Virtual health, Spinal cord injuries and disorders (SCI/D), Veterans Administration (VA), Veterans Health Administration (VHA), COVID-19

Key points

-

•

Video-based telehealth and other forms of delivering care virtually are useful tools in the provision of care to individuals with spinal cord injuries and disorders (SCI/D).

-

•

A wide range of services can be virtually delivered by SCI/D interdisciplinary team members, including education, counseling, reinforcement, monitoring, and information gathering.

-

•

The Veterans Administration increased the use of virtual health during the COVID-19 National Health Emergency so that continuity of care could be maintained for Veterans with SCI/D.

-

•

Telehealth supports care delivery to Veterans with SCI/D in a manner that is convenient and efficient.

Introduction

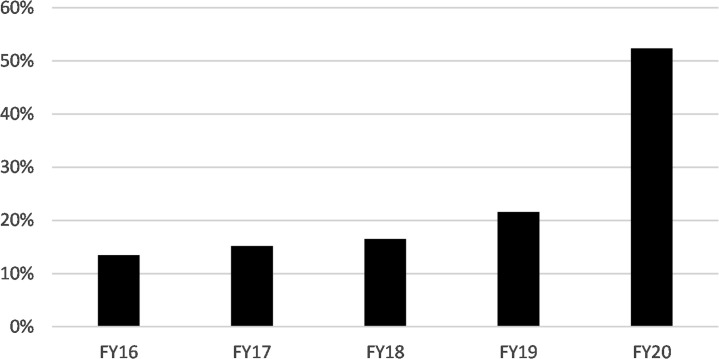

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is an international leader in the use of virtual health, including live video telehealth, asynchronous store-and-forward telehealth, remote patient monitoring, and mobile health. There are more than 9 million Veterans enrolled in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, and of those, approximately 6 million receive health care at VA medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics throughout the United States each year.1 Among these users of VA health care, 1.6 million Veterans (27.2%) received some type of virtual health care, and more than 4.8 million virtual visits were conducted between October 1, 2019 and September 30, 2020 (FY2020). Although this volume reflects higher use than in previous years, likely because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the VA has seen a steady and significant increase in the delivery of virtual care since 2009, when it aggressively implemented telehealth as part of the VA’s Transformation 21 (T-21) Initiative, an effort aimed at modernizing VA care. The growth of virtual care services is illustrated in Fig. 1 , which shows the percentage of VA’s overall patient population served through virtual care modalities over the past 5 years.

Fig. 1.

Percent of VA patients who received virtual care services.

Although the VA’s T-21 Initiative ushered in the VA’s modern age use of telehealth, the use of virtual care was not new to VA. As the nation’s largest integrated health care system, the VA was an early adopter and innovator in implementing the use of telehealth technologies to expand access to health care services to Veterans across the country. For example, in collaboration with the University of Nebraska in 1968, neurologic and psychiatric services were provided by a 2-way closed-circuit television system to VA patients located at VA Medical Centers (VAMC) in Omaha, Lincoln, and Grand Island, Nebraska.2 In 1970, a microwave bidirectional television system was set up between Massachusetts General Hospital and the Bedford VA Medical Center’s psychiatric ward to deliver video-based care.3 These early efforts were reflective of the VA’s commitment to technological innovation in enhancing care to Veterans. The potential value of this increased access is important for many individuals and groups, including the most vulnerable Veterans. Virtual care can reduce disparities that result from physical disabilities, difficulties with transportation, geographic barriers, and scarce specialists. In using virtual care to address disparities and access barriers, a particularly important subgroup to consider is Veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders (SCI/D) owing to the severity of disabilities associated with severe neurologic impairments, scarcity of knowledgeable SCI/D experts, and long distances to access care in VA SCI/D centers.

Veterans Administration spinal cord injuries and disorders system of care and virtual care

VA has the largest integrated, comprehensive, single network of SCI/D care in the nation, providing a full range of primary and specialty care to Veterans with SCI/D. More than 25,000 (FY20: 25,187 in the SCI/D Registry) eligible Veterans receive health care and services within the VA SCI/D System of Care, which is designed to provide lifelong care for all eligible Veterans with SCI/D. This SCI/D System of Care is focused on the provision of care from initial spinal cord injury, or onset of spinal cord disease, throughout the entire lifespan and includes health care management, health promotion and disease prevention, sustaining care, management of new health problems, and long-term care. In addition, the VA’s SCI/D System of Care is geographically dispersed throughout the nation, while maintaining integrated services and information systems. This dispersity allows continuity of care to be maintained even when Veterans move around the country, whether temporarily or permanently. At times, non-Veterans also receive care in the VA. For instance, rehabilitation is provided in the VA SCI/D System of Care to active-duty military service members with SCI/D, as established by a memorandum of agreement between the VA and Department of Defense.4

In the VA Spinal Cord Injury System of Care, the population served includes individuals with traumatic injuries and several nontraumatic spinal cord disorders, including multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, transverse myelitis, severe spondylotic cervical myelopathy, and spinal cord tumor. People with all levels of injury and severity are followed in the SCI/D System of Care, including individuals that are ventilator dependent and that need end-of-life care.5

The VA SCI/D System of Care is organizationally designed as a “hub-and-spokes” model in which 25 regional SCI/D centers (hubs), strategically located throughout the country, provide comprehensive primary and highly specialized care tailored to the needs of Veterans with SCI/D. Each of the regional SCI/D centers provides a full continuum of services, including acute rehabilitation, sustaining medical/surgical treatment, primary and preventive care, including annual evaluations, mental health services, provisions for prosthetics and durable medical equipment, and unique SCI/D care, such as ventilator management, respite care, and end-of-life care. Interconnected SCI/D programs and activities coordinate and extend care into the community, including SCI/D home care and other noninstitutional extended care programs. SCI/D centers are staffed by interdisciplinary teams (IDTs) of highly trained SCI/D health care clinicians, which include but are not limited to physicians; physician assistants; nurse practitioners; nurses; physical, occupational, recreation, and kinesiotherapists; psychologists; social workers; pharmacists; dietitians; and vocational counselors.

Each SCI/D center works with VAMC within a geographic catchment that does not have SCI/D centers, called VA SCI/D Spokes; smaller SCI/D teams in those VAMCs are called VA SCI/D Patient Aligned Care Teams. Approximately 110 spokes have dedicated SCI/D teams to deliver primary and basic SCI/D specialty care, and they work collaboratively with the respective SCI/D center to ensure that Veterans with SCI/D receive comprehensive care to address their diverse and complex needs. A spoke is often geographically closer and more accessible to a Veteran’s place of residence.

Services in the VA SCI/D System of Care span clinical settings, including inpatient, outpatient, long-term, home, and telehealth care. There are also unique dedicated institutional SCI/D long-term care units at 6 of the VA SCI/D centers. An SCI/D National Program Office provides operational, programmatic, administrative, management, and strategic oversight to the SCI/D System of Care and is organizationally aligned in VA Central Office.

In addition to the VA SCI/D System of Care infrastructure and services, there is an organized and accurate registry of Veterans with SCI/D. Standardized information about demographics, services and utilization, and outcomes is specified and collected for purposes of clinical care, operations, benchmarking, quality improvement, and research. The VA SCI/D registry is a standardized, automated database, which contains aggregated data created at the point of care. There are strict registry inclusion criteria, and the resultant data have been validated throughout the SCI/D System of Care. Using the registry, operational reports are created and made available through the VHA Support Service Center. A registry-based telehealth utilization report provides detailed reporting on telehealth usage among the VA’s SCI/D patient population.

Although this comprehensive network of physical locations and infrastructure is in place to provide SCI/D care, health care delivery to this population is complicated by barriers related to underlying physical disabilities, complex comorbid conditions, sparse SCI/D specialty services in most communities, and the rural residence of many Veterans with SCI/D. The use of SCI/D virtual care allows for Veterans with SCI/D to have more frequent contact and communications with SCI/D specialists, especially when large geographic distances limit access to specialty care. Many benefits of virtual care extend to individuals with SCI/D, including improved access, better coordinated patient care, closer follow-up, improved access to specialists, and increased patient satisfaction with care, whereas other benefits, such as prevention of secondary conditions, reduction in emergency room utilization, and cost savings, are less certain.6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Health care access provided to Veterans in the VA SCI/D System of Care is significantly enhanced using a wide range of virtual care modalities. These modalities include synchronous modalities, such as live video telehealth, asynchronous activities, such as store-and-forward telehealth, interactive remote patient monitoring, secure messaging, and a variety of mobile applications designed to promote Veteran health through self-care coaching. Telehealth within the SCI/D System of Care is supported by the SCI/D National Program Office with a dedicated Telehealth Program Analyst responsible for oversight, program and policy development, training, and supporting field-based telehealth staff in the SCI/D System of Care.

Spinal Cord Injuries and Disorders Telehealth Coordinators

As part of the T-21 Initiative in 2009, VA telehealth was expanded to further develop people-centric, results-driven, and forward-looking systems. As part of this initiative, each of the VA’s 25 SCI/D centers (hubs) was staffed with an SCI/D telehealth nurse coordinator, responsible for the implementation, oversight, expansion, and ongoing support of telehealth programs for the respective SCI/D center and its affiliated spokes. In most cases, the SCI/D Telehealth Coordinator is an experienced registered nurse, trained in the care of people with SCI/D as well as being technologically and telehealth proficient. These coordinators are responsible for establishing virtual care programs and ensuring that SCI/D virtual care modalities are effective and used efficiently by other members of the SCI/D IDT. Beyond the technical support and administrative oversight of telehealth operations, there are advantages in having a registered nurse function in this role. Because of their clinical expertise, the SCI/D telehealth coordinators are often involved in the direct provision of telehealth-based care to Veterans with SCI/D. For instance, some maintain a panel of Veterans with SCI/D that they regularly communicate with using video for follow-up care, education, and health maintenance. Other SCI/D telehealth coordinators monitor and coordinate care for patients who are participating in telehealth-based chronic disease management programs for conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. As members of the SCI/D clinical team, the telehealth coordinators participate in treatment planning and advance telehealth-based options to optimize patient care.

Utilization and Workload (Before and After the COVID National Public Health Emergency)

The implementation of telehealth use throughout the SCI/D System of Care has been an evolving process, particularly during the past 10 years. The use of telehealth and other virtual health modalities is not simply a case of what can or cannot be performed virtually. From the perspective of the health care clinician, initial adoption of telehealth was challenging, as it involved a cultural shift in the way care was delivered. Clinicians, especially those who work with complex patient populations, value in-person visits and sometimes question if high-quality care will be compromised without “hands-on” encounters with patients. Acute rehabilitation following the new onset of SCI/D remains an inpatient encounter rather than an attempt to do so virtually. There are many discrete clinical interactions with SCI/D patients that require an in-person, hands-on encounter, such as the detailed and standardized International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. New onset of specific symptoms (eg, neurologic loss, fever, respiratory symptoms) continues to be evaluated in face-to-face visits rather than virtual visits.

Besides these specific examples, the use of telehealth is now used to supplement and support almost all aspects of delivering clinical care to Veterans with SCI/D. All SCI/D disciplines have used virtual care and telehealth to communicate with Veterans, particularly during the COVID pandemic. The virtual annual evaluation highlights evaluations by the SCI/D IDT. Because most SCI/D outpatient clinics closed during the early months of the pandemic, annual evaluations were often performed virtually. SCI/D providers, nurses, therapists, social workers, psychologists, dieticians, and pharmacists have conducted their portion of the annual evaluation using telehealth. More generally, virtual health has been effective in providing patient education, counseling, reinforcement, monitoring, straightforward observations, and information gathering.

During the COVID pandemic, there have been unique interactions that demonstrate the value of virtual health. A standardized, nationally approved SCI/D COVID-19 screen template was developed in the early months of the pandemic and has been used by SCI/D center and spokes teams to reach out to Veterans with SCI/D. Various SCI/D team members use telephone and telehealth to contact the Veteran and ask questions, including the primary qualifying SCI/D diagnosis, living setting, caregiver status, if the patient has new concerns, and if there are new or additional symptoms. Many sites proactively contacted all Veterans on their respective SCI/D registries.

SCI/D clinicians are using telehealth to problem solve and triage new problems. Evaluating new equipment problems, reviewing progress and/or new concerns with pressure injuries, and addressing medication issues are examples of the usefulness of telehealth in addressing new concerns. Telehealth has also been used for continuity, management of chronic problems, and/or continuing treatment, such as weight management, mental health counseling, diabetes follow-up, and a variety of educational programs.

The use of clinical video telehealth is especially useful to enhance encounters made by SCI/D home care nurses during their in-person visits with Veterans living in the community. During a home visit, the SCI/D nurse sometimes needs input from a provider; a simple video connection can bring in any type of specialist for consultation. In addition, store-and-forward telehealth is used during SCI/D home visits to transmit images of pressure injuries to consulting providers and ensure efficient care management. Often, this eliminates the need for travel, which is complicated if weight-bearing on the pressure injury is contraindicated. The VA has recently engaged in a pilot to enhance SCI/D home care using wearable technology that allows the transmission of vital signs, such as oxygen levels, heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature, allowing providers to virtually monitor a patient’s condition and provide interventions when necessary.

An additional challenge to telehealth implementation is that Veterans with SCI/D often value the opportunity to come to the SCI/D center to see their providers and other Veterans in person. Many Veterans have been receiving care in the SCI/D System of Care for decades, and they develop trusting relationships with care providers. Veterans establish friendships and close relationships with peers. Although virtual care may offer convenience, improved access, lower costs and may be an appropriate modality for many SCI/D-related services, some Veterans still choose to have in-person visits for these other reasons.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a monumental shift in both utilization and attitudes toward telehealth among providers and Veterans. Especially during the initial months of the pandemic, telehealth use became a fundamental tool in maintaining continuity of care for Veterans with SCI/D served by the VA. As illustrated in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 , there has been a remarkable increase in the number of Veterans with SCI/D who have participated in telehealth visits during FY2020. This increase is not surprising given that most routine outpatient in-person visits were canceled during the early months of the pandemic, and visits were shifted to virtual care. Fig. 2 shows the percentage of Veterans listed on the SCI/D registry who have received telehealth services. The figure demonstrates the steady adoption of telehealth use within the SCI/D system of care in FY2016 to FY2019 and the dramatic increase experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic during FY20.

Fig. 2.

Percent of Veterans listed on the VHA SCI/D registry who received telehealth services.

Fig. 3.

Telehealth visits provided to Veterans listed on the VHA SCI/D registry.

Fig. 4.

Average number of telehealth visits per SCI/D patient listed on the VHA SCI/D registry who received telehealth.

Fig. 3 shows the total number of telehealth visits provided to Veterans with SCI/D during the past 5 years, also illustrating the gradual increase in telehealth utilization in the previous 4 years, which greatly accelerated during FY20. In comparing FY2019 to FY20, there was more than a 400% increase in telehealth visits. This increase in telehealth utilization during the COVID pandemic reflects the SCI/D System of Care effective response to the pandemic and new constraints on face-to-face visits because Veterans with SCI/D are at extremely high risk of complications following respiratory disease. People who live with SCI/D often develop respiratory complications and/or are at risk of complications, hospitalizations, or death from respiratory illnesses. Burns and colleagues11 recently published research concerning a higher mortality for Veterans with SCI/D (19%) than the general Veteran population (7.7%) enrolled for VHA health care; both populations have a similar proportion of individuals aged 65 years or greater. The SCI/D Veteran case fatality rate with COVID-19 is 2.4 times the rate observed in the non-SCI/D Veteran population, with an absolute rate that is 11% greater (95% confidence interval: 5%–19%; Z score = 4.8; P < .0002). Because of the high risk for COVID-related complications, hospitalizations, and death, there were aggressive efforts to contact Veterans with SCI/D by clinicians using telehealth to avoid in-person visits, and to screen Veterans with SCI/D for symptoms of COVID or other respiratory problems.

When telehealth usage among Veterans with SCI/D is analyzed at the individual patient level, as illustrated in Fig. 4, Veterans who participated in telehealth received an average of 3 telehealth visits per year between FY2016 and FY2019. In FY20, that doubled to approximately 6 visits per year, reflecting increased use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the original goals of telehealth implementation in VA was to increase access, especially for Veterans who live in rural areas and need to travel long distances to a clinic or medical center. Long distance travel is particularly difficult for people with disabilities, including SCI/D. However, there are issues that can make telehealth use challenging for rural Veterans. Connectivity, through cellular broadband, wired, or satellite-based Internet, is limited in rural areas of the country. In late FY20, the VA implemented a new program called “Digital Divide,” which provides an assessment of the “technology gaps” that might prevent a Veteran from participating in telehealth. Once gaps are identified, solutions can be offered to the Veteran, which may include a referral to the Federal Communication Commission Lifeline program to subsidize home Internet service and provide devices such as smartphones or tablets. In addition, the VA has a program to loan broadband-enabled iPads to Veterans who lack such devices. As technology advances and the availability of high-speed Internet options expands to more rural communities across the nation, it is expected that more Veterans will be able to take advantage of the improved access offered through virtual modalities.

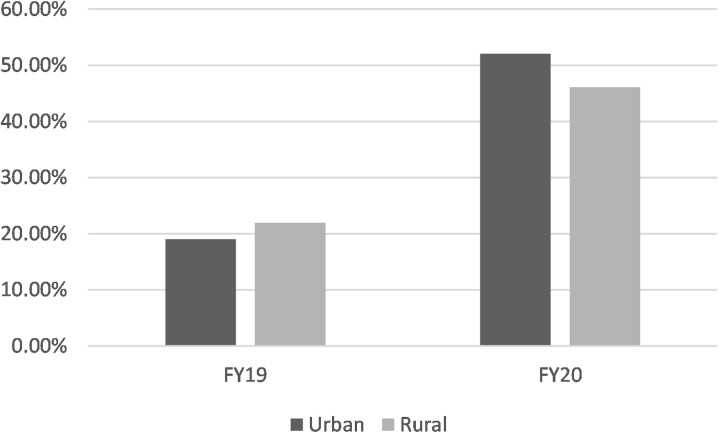

Although one might expect that rural Veterans would be the primary users of VA telehealth services, urban Veterans also took advantage of virtual care services. In FY19, 21.98% of Veterans listed on the SCI/D registry and designated as “rural” took advantage of telehealth services, whereas 19.02% of those designated as “urban” did the same, reflecting a modest difference between the 2 groups. In FY20, as illustrated in Fig. 5 , there was a small shift, likely because of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 46.1% of “rural” Veterans receiving telehealth services compared with 52.7% of their urban-residing counterparts. During the pandemic, other factors likely unrelated to geography prevented or discouraged Veterans with SCI/D from seeking in-person care, including closure of many SCI/D clinics, limiting admissions to inpatient SCI/D center beds, delaying elective procedures, and reluctance by Veterans with SCI/D to go in to clinics and medical centers.

Fig. 5.

Percent of SCI/D Veterans receiving telehealth services based on geography.

In addition to the need to accurately identify the VA SCI/D population, which is provided by the SCI/D registry described earlier, tracking telehealth utilization is highly dependent on accurate and specific coding of SCI/D telehealth encounters. When telehealth was initially introduced throughout the SCI/D System of Care years ago, tracking implementation and utilization were complicated by the absence of a coding system to easily differentiate telehealth visits from in-person visits, and visits provided by SCI/D providers versus other VA providers. Differentiating between provider types was remedied with the development of an SCI/D-specific telehealth workload coding system, which now provides accurate tracking of workload, including the location and provider of care. The system requires providers to accurately code the encounter in the VA’s electronic medical record system.

Although Veterans with SCI/D are often provided both SCI/D-specific primary and specialty care services by SCI/D-trained clinicians within the SCI/D System of Care, some Veterans with SCI/D receive care in non-SCI/D settings by non-SCI/D clinicians (eg, primary care, mental health services). Fig. 6 illustrates that 57% of telehealth services provided to Veterans with SCI/D were SCI/D-specific, whereas the remaining 43% of the services they received were provided in settings outside the SCI/D System of Care. In addition, Veterans with SCI/D may be enrolled and receive services from a VA facility's remote home monitoring program to manage chronic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, which is managed by nurses who may not be solely dedicated to SCI/D care.

Fig. 6.

VHA telehealth services delivered to Veterans with SCI/D in FY20.

The establishment of more effective workload tracking, combined with the ability to more accurately identify the VA’s SCI/D patient population using the SCI/D registry, places the VA in a better position to use data more effectively to better understand the current state, establish improvement goals and performance benchmarks, and expand use of telehealth within the SCI/D Veteran population.

In summary, when comparing the VA’s SCI/D cohort with the overall population of Veterans served by the VA, a greater percentage of Veterans with SCI/D (52.3%) took advantage of VA telehealth services compared with 27.9% of the overall VA patient population.

Performance Measurement

The VHA is the largest integrated health system in the United States. In 1995, under the leadership of the VHA Undersecretary for Health, Kenneth Kizer, MD, MPH, a major initiative was launched that included a focus on achievement of performance-based outcomes. This initiative has been evolving for years and has resulted in recognition of VA for leadership in clinical informatics and data-driven performance improvement. To best serve Veterans, the alignment of strategic direction, business operations, technology, and data must be methodically designed, aggregated, and managed to deliver the right information to the right people at the right place and time. During this same period, there have been significant efforts to increase the use of performance-based metrics for telehealth in VA. Beginning in FY11, performance expectations were set for all VHA facilities to achieve delivery of virtual care-based services to a minimum percentage of Veterans enrolled at each VA facility. At the same time, the SCI/D System of Care set performance targets to align with VA’s goals and to increase telehealth utilization. As a result of these and other implementation efforts, steady growth in the use of telehealth has been seen over the years, as illustrated earlier in Fig. 1. Establishing standards and providing accurate data identified best practices and potential areas of improvement.

Maintaining relevant and achievable targets for telehealth use and expansion has faced challenges related to the competition for resources and provider time as well as the need to have adequate and cooperative buy-in from providers to incorporate telehealth use into their practice. The SCI/D System of Care has made a concerted effort to ensure that the establishment of performance metrics includes input from SCI/D subject matter experts in the field. Recently, this has been accomplished through the establishment of “think tanks” made up of field-based clinicians to address a wide variety of issues related to the care of Veterans with SCI/D. In the SCI/D Registry and Outcomes Think Tank, a performance measurement workgroup defines metrics to drive the enhancement and quality of services in the SCI/D System of Care. Recognizing the importance of virtual modalities in maintaining continuity of care and improving access to specialty services for Veterans with SCI/D during the COVID-19 pandemic, this group established an FY2021 goal to achieve 100% of outpatient SCI/D providers with capabilities to provide video-based telehealth services to patients in their home or other non-VA sites using the VA Video Connect (VVC) Platform. This goal aligns with a larger VA-wide goal to ensure that all primary care providers have this capability. Recognizing the importance of providing convenient access to specialty care for Veterans with SCI/D regardless of where they live and to address the varied needs that arise in this population, the goal in SCI/D goes a step further to ensure that all SCI/D clinicians have the capability to deliver virtual care, including physical and occupational therapists, pharmacists, social workers, mental health practitioners, and others who are delivering outpatient care to Veterans with SCI/D. The goal is to ensure that all SCI/D IDT clinicians are able to provide care, and Veterans with SCI/D have the choice to receive in-person or virtual care. In looking forward, the Think Tank workgroups are considering volume-based targets, which will aim to drive expanded use of telehealth to a larger percentage of Veterans with SCI/D and to ensure that facilities continue to offer telehealth-based services as a routine component of care for Veterans with SCI/D.

Technological Considerations

The initial implementation of telehealth within VA involved connecting 2 VA care sites by video. Within the SCI/D System of Care, this allowed Veterans with SCI/D to participate in visits, being present at the clinic or the SCI/D center. Telehealth visits between two VA care sites was particularly important for transitions of care. It also allowed Veterans to travel to a closer SCI/D spoke site location and still receive services from SCI/D specialists located at a distant SCI/D center in collaboration with the SCI/D spoke team. The technology and special telehealth equipment involved in these encounters are housed at VA clinics and SCI/D centers, operated by specially trained Telehealth Clinical Technicians and SCI/D Telehealth Coordinators. There are great coordinative advantages in these synchronous real-time video appointments between VA facilities and include activities such as discharge planning; specialty consultations, including pressure injury, neurogenic bladder, and pain management; preoperative planning; and wheelchair seating assessments. In general, Veterans and clinicians value these telehealth encounters, but coordination of the clinic-based telehealth visits is difficult, particularly when several clinicians participate. Challenges with clinic-to-clinic live video telehealth include coordination of appointments, equipment, space, and staff between 2 geographically separated teams.

Recognizing the potential to reach directly in to the Veterans’ homes, VA has more recently released an application known as VVC, which allows Veterans to participate in virtual visits with a clinician using any video-enabled device, including a smartphone, tablet, or personal computer. VVC eliminates the need for the Veteran to travel and allows for direct conversation with the clinician. It also simplifies coordination for the visit in comparison with clinic-based telehealth. However, in implementing this program, challenges included a lack of technology, knowledge, and skills, especially for older Veterans, to participate in these types of visits. To solve this, the VA funded a program to loan Apple iPads, mentioned earlier, to Veterans who lacked their own devices. During the last quarter of calendar year 2020, the VA provided 57,000 of these devices to Veterans, and an additional 18,000 are on order. The program to provide tablets to Veterans solved many problems. However, Veterans with SCI/D may still have challenges or barriers in using iPads, particularly when hand function is impaired. A variety of strategies, tools, and modifications to use the devices have been used as needed by each individual Veteran with SCI/D. For instance, some Veterans require the activation of accessibility features built into the Apple iOS software to control the device with voice or a stylus. Simplification of multiple steps required to join an appointment has also been helpful for many Veterans with SCI/D. Devices can be set up in a mode known as “single use,” which disables many of the features of an iPad in order to simplify its use for 1 application and minimizing multiple steps that normally would have to be taken to access the VVC application. In normal use, a Veteran receives an e-mail reminder about their upcoming video appointment, which contains a link to join the virtual meeting. However, some Veterans have been challenged with multiple steps required to join a VVC meeting, including use of a password to unlock the iPad, opening an e-mail application, finding the particular e-mail with their appointment, clicking the link to join the appointment, and then going through multiple steps to join the appointment. This challenge has been resolved with system modifications, which allow a provider to call the Veteran’s specific device through the VVC application, only requiring a single click on the screen of the iPad by the Veteran.

The SCI/D Telehealth Coordinators and other SCI/D IDT members are invaluable in addressing barriers, training, education, positioning, adaptive equipment (eg, grips, stands, and styluses), and modifications of software settings to enable Veterans with SCI/D to more easily use VVC. Although the VA has set up a help desk hotline that operates on a 24-hour, 7-day-a-week schedule for Veterans who need assistance in setting up and using their VVC application, one of the limitations is that the technicians who staff the hotline are not trained to understand the unique physical limitations and challenges that are relevant to the use of technology by a person with SCI/D. Efforts are underway to address these limitations through increased training.

A more recent development, a mobile app called MyVA Images, is an example of the rapid advancement of virtual health apps that have tremendous potential for interactive asynchronous modalities. MyVA Images allows Veterans and/or their caregivers to securely submit still images or short video clips, in response to requests entered by providers to aid in evaluation and treatment. For example, a provider may request a photograph of an area of pressure injury for further evaluation and treatment. A gait video clip may be requested to further assess walking, mobility, and balance. Photographs of the environment may be requested to evaluate safety, accessibility, and barriers in the home. The MyVA Images App is in the pilot phase with expected wide rollout during 2021. Other mobile applications in use by VA provide self-management for pressure injuries, management of posttraumatic stress disorder, pain management, and coaching during quarantine and isolation during the COVID pandemic.

Discussion

During the past several years, virtual health technologies have expanded rapidly, increasing access to health care in ways that were never before possible. For people with SCI/D and other severe disabilities, there is great potential in using telehealth to address needs and unique barriers to care. In addition, virtual health can be used during local, national, or international emergencies, when travel, access, systems, infrastructure, and in-person visits are affected.

The VA SCI/D System of Care has seen the unprecedented use of virtual health technologies during the COVID-19 health emergency. Because in-person visits were restricted, many disciplines from the SCI/D IDT used direct telehealth communication with Veterans with SCI/D to address a variety of needs and functions, including outreach to check on the status of each Veteran on the SCI/D Registry during the COVID pandemic; contact with Veterans with SCI/D to encourage flu vaccinations; follow-up of SCI/D complications (eg, pressure injuries, neurogenic bladder, and chronic pain); monitoring of chronic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension; acute and subacute rehabilitation following onset of SCI/D by various members of the SCI/D IDT; medication reconciliation by SCI/D pharmacists; and annual evaluations.

Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, many virtual health modalities have been used in the VA SCI/D System of Care. The greatest growth and use have been direct synchronous telehealth from clinicians to Veterans with SCI/D in their homes. Given the mobility challenges and vulnerability of Veterans with SCI/D to clinical complications, minimizing exposure during the COVID National Public Health Emergency to health threats experienced during in-person health care visits using telehealth in the home was and remains a top priority.

The advancement of technology during the past few years has also allowed expansion of virtual health to most Veterans with SCI/D, even in extremely rural environments, and expands the ability to provide what the Veteran needs at the right time while staying at home. During and following the pandemic, it is likely that continued rapid development and implementation of virtual health modalities and tools will occur.

There have been previous studies and articles about the use of telehealth in people with spinal cord injury.7 Many of the studies were feasibility, observational, or pilot studies with small samples, primarily using telehealth communication directly to the consumer. Diverse questions were studied, and various outcome measures were used, most of which focused on the postrehabilitation period following an acute spinal cord injury. Other studies examined various modalities, often using asynchronous telehealth, including store-and-forward images of pressure injuries, Web-based treatments, and interactive home monitoring. In general, and anecdotally, there is wide acceptance of virtual health by many patients, consumers, caregivers, and clinicians. Nevertheless, there has been little systematic study of the use of virtual care modalities in the SCI/D population. Much work is needed to determine the relative benefits, effectiveness, costs, and obstacles to the wide use of virtual health as compared with face-to-face health care by the SCI/D community.

There is no doubt that virtual care will be part of the evolution of health care throughout the world for years to come. Many aspects of these technological advances have the potential to solve many access problems shared across disability groups. Changes have already begun. Data published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services demonstrated similar changes as evidenced in VA and in the SCI/D System of Care. Between 2014 and 2016, there was a 37.7% increase in the number of beneficiaries with disabilities using telehealth and a 53.7% increase in the total services used by these same beneficiaries.12

The COVID-19 pandemic has transformed health care as well as society and the economy. This current article focuses on the use of virtual health by Veterans with SCI/D during the COVID-19 National Public Health Emergency. A description of utilization and virtual modalities is provided comparing the current year with previous years of concerted efforts to provide virtual care to Veterans with SCI/D. This global health emergency has presented unprecedented challenges to in-person health care visits and catalyzed the rapid development of virtual care to meet and move beyond those challenges. During the COVID pandemic, VA telehealth and other virtual care modalities have been used to connect Veterans with SCI/D and IDT clinicians to maintain health, prevent complications, and address new issues because access to the VA SCI/D System of Care was significantly curtailed. In all likelihood, this situation will continue for several months or perhaps years. At the time of this writing, there is another surge that has resulted in record high numbers and rates for new daily cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. Reliance on virtual health modalities during the COVID pandemic will remain a priority in the VA SCI/D System of Care.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been many advantages in the use of telehealth and other virtual modalities. Virtual care has provided a means of consistent communication, access, and continuity of care that overcome physical barriers during a time when in-person services were discontinued, “stay-at-home” orders were established, and physical distancing measures were used to reduce community and nosocomial spread. Secondary benefits included the conservation of personal protective equipment and decreased use of beds for other purposes to expand COVID units and to allow flexibility and adaptability to physical or geographic boundaries where there are surges.

Although the future utilization of VA SCI/D virtual care following the COVID-19 pandemic is unknown, telehealth use will probably be greater than prepandemic levels, now that a significant number of providers and Veterans have experienced its advantages. As with other technologic advancements, there is great potential for use of virtual health modalities by people with disabilities. Nevertheless, there remain broad questions about the development of virtual health and its application for people with disabilities. There is recent evidence that the digital divide remains large between Americans with and without a disability. The Pew Research Center recently found that disabled Americans are about 3 times as likely as those without a disability to say they never go online (23% vs 8%), One-in-four disabled adults say they have high-speed Internet at home, a smartphone, a desktop or laptop computer, and a tablet, compared with 42% of those who report not having a disability. Regardless of age, disabled Americans are adopting technology at lower rates, although the divide is even greater with older disabled Americans.13 In the VA SCI/D System of Care, the average age of Veterans on the SCI/D Registry is 63 years of age, underscoring the complexities involved in a population of severely disabled that is in many cases older adults.

There are broad issues related to the development of virtual health for people with disabilities. There is a moral imperative to ensure that innovations in virtual care are available and accessible to people with disabilities. Although there is face validity to the potential benefits of virtual care for disabled Americans, advances in the field can paradoxically further heighten health and social disparities. Involving people with disabilities on the development, implementation, and study of virtual health is of the utmost importance.

There is much work left to do. There are still fundamental questions about effectiveness of virtual health, optimizing virtual care in the SCI/D community, addressing barriers, rigorously addressing satisfaction by Veterans and clinicians, and examining costs. Because Veterans with SCI/D is a well-defined population and there is a well-organized infrastructure for care, the VA SCI/D System of Care is an ideal setting to examine many of these questions.

Clinics care points

-

•

Virtual health increases access and offers advantages for people with severe disabilities, such as spinal cord injuries and disorders.

-

•

Virtual health increases access during periods of natural disasters and other public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Telehealth offers advantages to prospectively contact people living in the community at high risk for complications, such as Veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

The Veterans Health Administration is an international leader in the use of virtual health and has greatly increased use of telehealth during the COVID National Public Health Emergency in the Spinal Cord Injuries and Disorders System of Care.

-

•

There are some aspects of the spinal cord injuries and disorders examination that cannot be performed virtually, including the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury.

-

•

In the spinal cord injuries and disorders population, there are still fundamental questions about effectiveness of virtual health, how best to optimize care, limitations of telehealth, and how best to address barriers, rigorously addressing satisfaction by Veterans and clinicians and examining costs.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.How many Veterans receive healthcare at VA each year? https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp#:∼:text=The%20Veterans%20Health%20Administration%20(VHA,Veterans%20enrolled%20in%20the%20VA Available at: Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 2.Wittson C.L., Benschoter M.S. Two-way television: helping the medical center reach out. Am J Psychiatry. 1972;129(5):624–627. doi: 10.1176/ajp.129.5.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dwyer T.F. Telepsychiatry: psychiatric consultation by interactive television. Am J Psychiatry. 1973;130(8):865–869. doi: 10.1176/ajp.130.8.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memorandum of Agreement between Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense for medical treatment provided to active duty service members with spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, blindness, or polytraumatic injuries (2009).

- 5.VHA Directive 1176(2): Spinal cord injuries and disorders system of care, September 30, 2019 (Revised February 7, 2020).

- 6.Careau E., Dussault J., Vincent C. Development of interprofessional care plans for spinal cord injury clients through videoconferencing. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(1):115–118. doi: 10.3109/13561820902881627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irgens I., Rekand T., Arora M., et al. Telehealth for people with spinal cord injury: a narrative review. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:643–655. doi: 10.1038/s41393-017-0033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woo C., Seton J.M., Washington M., et al. Increasing specialty care access through use of an innovative home telehealth-based spinal cord injury disease management protocol (SCI DMP) J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39(1):3–12. doi: 10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulter E.H., McLean A.N., Hasler J.P., et al. The effectiveness and satisfaction of web-based physiotherapy in people with spinal cord injury: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:383–389. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houlihan B.V., Brody M., Everhart-Skeels S., et al. Randomized trial of a peer-led, telephone-based empowerment intervention for persons with chronic spinal cord injury improves health self-management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns S.P., Eberhart A.C., Sippel J.L., et al. Case-fatality with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in United States Veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders. Spinal Cord. 2020;58(9):1040–1041. doi: 10.1038/s41393-020-0529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CMS. Information on Medicare telehealth report. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2018. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/Downloads/Information-on-Medicare-Telehealth-Report.pdf Available at: Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 13.Pew Research Center Disabled Americans are less likely to use technology. 2017. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/07/disabled-americans-are-less-likely-to-use-technology/ Available at: Accessed December 15, 2020.