Abstract

Background and Purpose

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a comprehensive impact on healthcare services worldwide. We sought to determine whether COVID-19 affected the treatment and prognosis of hemorrhagic stroke in a regional medical center in mainland China.

Methods

Patients with hemorrhagic stroke admitted in the Neurosurgery Department of West China Hospital from January 24, 2020, to March 25, 2020 (COVID-19 period), and from January 24, 2019, to March 25, 2019 (pre-COVID-19 period), were identified. Clinical characteristics, hospital arrival to neurosurgery department arrival time (door-to-department time), reporting rate of pneumonia and 3-month mRS (outcome) were compared.

Results

A total of 224 patients in the pre-COVID-19 period were compared with 126 patients in the COVID-19 period. Milder stroke severity was observed in the COVID-19 period (NIHSS 6 [2–20] vs. 3 [2–15], p = 0.005). The median door-to-department time in the COVID-19 period was approximately 50 minutes longer than that in the pre-COVID-19 period (96.5 [70.3–193.3] vs. 144.5 [93.8–504.5], p = 0.000). A higher rate of pneumonia complications was reported in the COVID-19 period (40.6% vs. 60.7%, p = 0.000). In patients with moderate hemorrhagic stroke, the percentage of good outcomes (mRS < 3) in the pre-COVID-19 period was much higher than that in the COVID-19 period (53.1% vs. 26.3%, p = 0.047).

Conclusions

COVID-19 may have several impacts on the treatment of hemorrhagic stroke and may influence the clinical outcomes of specific patients. Improvements in the treatment process for patients with moderate stroke may help to improve the overall outcome of hemorrhagic stroke during COVID-19.

Key Words: hemorrhagic stroke, Outcome, Pneumonia, Coronavirus disease

Introduction

Stroke, which includes ischemic and hemorrhagic types, is a common cause of disability and mortality worldwide. Although the ischemic type accounts for nearly 80% of all strokes, hemorrhagic stroke can often lead to more serious health consequences.1 Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are particularly crucial to improve survival and functional prognosis in stroke. The COVID-19 pandemic not only endangers human health by itself but also impacts the treatment and diagnosis of other diseases by triggering complications and even changes the entire health care service process. In mainland China, all patients who go to the hospital are required to wear masks and accept SARS-CoV-2 screening to prevent nosocomial infection. In this study, we attempted to determine whether and how these in-hospital epidemic prevention measures exert their influence on the treatment and prognosis of patients with hemorrhagic stroke.

Methods

West China Hospital, the largest medical center in western China, possesses a stroke center that is open 24 h a day. On January 24, Sichuan Province issued a “first-level response” to cope with COVID-19, which was then degraded to a “third-level response” on March 25. Patients with hemorrhagic stroke who visited the Neurosurgery Department of West China Hospital during the period from January 24, 2020 to March 25, 2020 (COVID-19 period) and the period from January 24, 2019 to March 25, 2019 (for comparison, pre-COVID-19 period) were identified. The diagnosis of hemorrhagic stroke, including subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), was confirmed by a combination of symptoms, physical findings, and imaging findings. Computed tomography was performed in all patients. Patient medical records, including age, sex, vascular risk factors (smoking and drinking), underlying diseases, stroke type, baseline NIHSS score, treatment information, complications, and clinical outcomes (modified Rankin Scale, mRS), were reviewed and recorded. Door-to-department time was defined as the duration between emergency department (ED) arrival and neurosurgery department arrival. This time includes two parts: the time patients stay in the ED and accept treatment and screening of COVID-19 from ED physicians, and the transit time. The criteria for pneumonia diagnosis is consistent with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS)2. Specifically, pneumonia was diagnosed in patients with clinically compatible signs (e.g., fever, dyspnea, cough, sputum production) and demonstration of infiltrate on chest imaging (chest X-ray or CT scan). Besides, all the included patients have received COVID-19 tests and none of them were tested positive for COVID-19.

All patients were followed-up through phone calls, and the clinical outcome at 3 months was recorded. Good clinical outcome was defined as an mRS score of 0–2 at the follow-up.

We used SPSS statistics 23.0 for data analysis. Independent-samples t tests, chi-square tests, Mann-Whitney U tests and Fisher's exact tests were performed where appropriate for the comparison of different types of data between COVID-19 and pre-COVID-19 patients. p-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

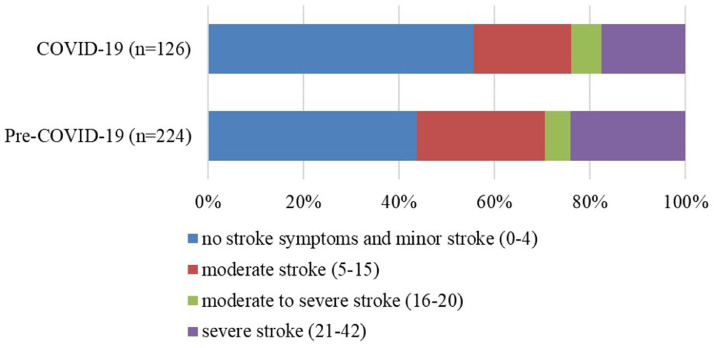

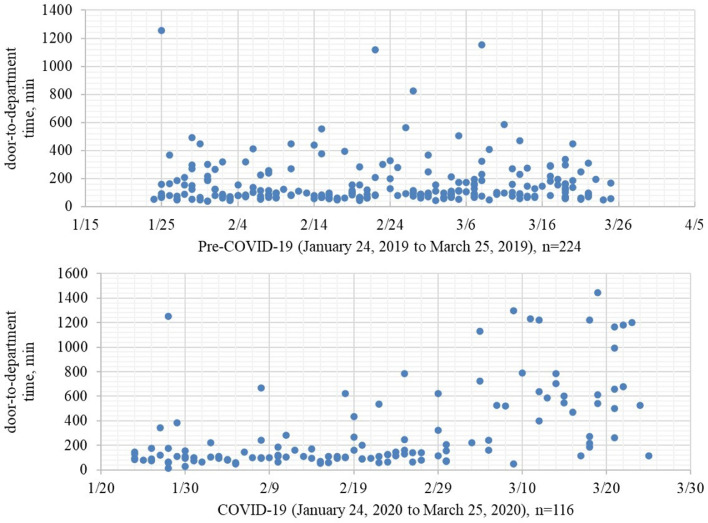

In total, 224 and 126 patients with hemorrhagic stroke were admitted through the emergency department in the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods, respectively. There were no significant differences in age, sex, vascular risk factors, or classification of hemorrhagic stroke between the two groups. The disease severity for patients admitted pre-COVID-19 was greater than that for patients admitted during COVID-19 (6 [2–20] vs. 3 [2–15], p = 0.005; Table 1 ). The ratios of different disease severities are shown in Fig. 1 . More patients accepted surgery in the COVID-19 period (51.3% vs. 62.7%, p = 0.040; Table 1). The median door-to-department time in the COVID-19 period was approximately 50 minutes longer than that in the pre-COVID-19 period (96.5 [70.3–193.3] vs. 144.5 [93.8–504.5], p = 0.000; Table 1), and we present the data of each single patient in Fig. 2 . A higher rate of pneumonia complications was reported in the COVID-19 period (40.6% vs. 60.7%, p = 0.000; Table 2 ). After we classified disease severity, it was mainly caused by higher reported rates of pneumonia in patients with minor (0–4 NIHSS, = 0.000) or severe (21–42 NIHSS, p = 0.032) stroke (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Pre–COVID-19 and COVID-19 Patients

| Pre-COVID-19 (N = 224) | COVID-19 (N = 126) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y (SD) | 53.7 (17.3) | 54.9 (14.9) | 0.515 |

| Males, % | 120 (53.6) | 66 (52.4) | 0.830 |

| Smoker, % | 60 (26.8) | 28 (22.2) | 0.345 |

| Drinker, % | 53 (23.7) | 22 (17.5) | 0.175 |

| Underlying Disease | |||

| Hypertension | 135 | 64 | 0.086 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21 | 7 | 0.206 |

| Renal insufficiency | 4 | 3 | 0.706 |

| Heart disease | 4 | 1 | 0.658 |

| Pulmonary disease | 5 | 8 | 0.074 |

| Classification of Hemorrhagic Stroke and Severity | |||

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 126 | 60 | 0.120 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 98 | 66 | |

| Median-baseline NIHSS (IQR) | 6 (2–20) | 3 (2–15) | 0.005 |

| Treatment | |||

| Medical Only | 109 | 47 | 0.040 |

| Surgical | 115 | 79 | |

| Median door-to-department time, min (IQR) | 96.5 (70.3–193.3) | 144.5 (93.8–504.5) | 0.000 |

Figure 1.

Ratios of Different Stroke Severities in the COVID-19 and Pre-COVID-19 Periods

Figure 2.

Door-to-Department Time

Table 2.

Reported Rates of Pneumonia in Patients with Different Stroke Severity

| NIHSS | Pre-COVID-19 |

COVID-19 |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Pneumonia (%) | N | Pneumonia (%) | ||

| 0–4 | 98 | 26 (26.5) | 70 | 45 (64.3) | 0.000 |

| 5–15 | 60 | 28 (46.7) | 26 | 14 (53.8) | 0.541 |

| 16–20 | 12 | 4 (33.3) | 8 | 6 (75.0) | 0.170 |

| 21–42 | 54 | 33 (61.1) | 22 | 19 (86.4) | 0.032 |

| Total | 224 | 91 (40.6) | 126 | 84 (67.7) | 0.000 |

The clinical outcomes of 274 patients were gathered at 3 months, and there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups overall; 92 patients (51.1%) in the pre-COVID-19 period and 51 patients (54.3%) in the COVID-19 period achieved good outcomes (p = 0.621, Table 3 ). However, in patients with baseline NIHSS scores ranging between 5 and 15 (moderate stroke), the percentage of patients who achieved good outcomes in the pre-COVID-19 period was much higher than that in the COVID-19 period (53.1% vs. 26.3%, p = 0.047; Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Outcome of Pre–COVID-19 and COVID-19 Patients

| NIHSS | Sample Size |

Good Outcome (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID-19 | COVID-19 | Pre-COVID-19 | COVID-19 | P | |

| 0–4 | 75 | 50 | 60 (80.0) | 44 (88.0) | 0.241 |

| 5–15 | 49 | 19 | 26 (53.1) | 5 (26.3) | 0.047 |

| 16–20 | 12 | 7 | 3 (25.0) | 1 (14.3) | 1.000 |

| 21–42 | 44 | 18 | 3 (6.8) | 1 (5.6) | 1.000 |

| Total | 180 | 94 | 92 (51.1) | 51 (54.3) | 0.621 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this research is the first study focusing on hemorrhagic stroke and reports patients’ 3-month mRS during COVID-19. According to the results of our study, the COVID-19 pandemic has had several impacts on the diagnosis and treatment processes for hemorrhagic stroke in our center. In contrast to the pre-COVID-19 period, there was a sharply decreased number of patients admitted to our department with hemorrhagic stroke. At the same time, decreased disease severity was observed. Since the incidence and ratios of different severities should remain stable, we thought that there were 2 possible reasons for these phenomena: first, consistent with some existing studies,3 fewer patients sought hospital treatment because of COVID-19; second, due to transportation restrictions, fewer patients could arrive at our hospital, the medical center of our region, and they needed to seek treatment at the primary healthcare institution. All hypotheses we mentioned above should be further confirmed by data from primary hospitals in our region, but improving the service capabilities of primary medical and health institutions is important for improving the prognosis of patients with hemorrhagic stroke,4 which may become even more important during COVID-19.

One interesting result in our research is the extremely high reported rate of pneumonia during COVID-19. The occurrence rate of SAP has long been controversial,5 , 6 not only because there is no uniform clinical diagnostic standard but also because the occurrence of pneumonia is heavily influenced by stroke severity. After the subgroup analysis by severity, differences were mainly found in patients with minor or severe hemorrhagic stroke. The Chinese government has adopted several important preventative strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic; wearing masks is the representative strategy. In our hospital, we also limit the number of family members at the bedside and restrict people with respiratory symptoms from approaching patients. These measures should reduce the incidence of pneumonia; however, our results indicate the opposite. As shown in some previous studies,7 stroke patients exposed in the emergency department could have a higher occurrence of SAP, and the prolonged door-to-department time in our study may be responsible for the higher pneumonia rate. Another reasonable explanation for this phenomenon is that our doctors paid more attention to patients’ lungs during COVID-19, although this type of “concern” did not lead to improvement in patients’ clinical outcomes (3-month mRS, Table 2).

From the perspective of clinical outcome, no statistically significant difference was found when comparing total samples. Because stroke severity is the major confounder that directly impacts prognosis, better baseline NIHSS scores could always predict better prognosis, and subgroup analysis was also performed in this section. For patients who suffered moderate hemorrhagic stroke (NIHSS score 5–15) during COVID-19, the clinical outcomes were not as good as those before COVID-19. NIHSS is commonly used to predict the prognosis of stroke: a score of > or =16 strongly forecasts death, while a score of < or =6 forecasts a good recovery.8 Moderate stroke (5–15 NIHSS) is the “interzone” between good and bad prognoses, which remains afflicted with uncertainty. For these patients, the differences in the treatment process would have a larger impact on the prognosis. Based on our results, it is reasonable to consider whether the worse prognosis of moderate stroke during COVID-19 is associated with a prolonged waiting time in the emergency department (door-to-department time).

There are some limitations in our study. First, this research is a single-center retrospective study; therefore, the quality of medical information was inherently limited, and the full extent of our study was constrained. Second, our patients were not stratified according to the different pathogeneses of hemorrhagic stroke for further analysis. Third, some patients who arrived in the emergency department and left the hospital or died before admission to the neurosurgery department were not included in our study, which could have a potential impact on the distribution of disease severity and outcomes.

Our findings show that COVID-19 may have several impacts on the treatment of hemorrhagic stroke and may influence the clinical outcomes of patients with moderate stroke. Improvements in the treatment process for patients with moderate stroke may help to improve the overall outcome of hemorrhagic stroke during COVID-19.

Ethical approval/Informed consent

Prior to conducting the study, approval was obtained from the Ethics Council of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Grand support

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Footnotes

This work was performed in the West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Nguyen G, Cercy K, Johnson CO, Alam T, Parmar PG, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abd-Allah F, Abejie AN, et al. Global, regional, and country-specific lifetime risks of stroke, 1990 and 2016. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2429–2437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, Cooley LA, Dean NC, Fine MJ, Flanders SA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–e67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teo KC, Leung WCY, Wong YK, Liu RKC, Chan AHY, Choi OMY, Kwok WM, Leung KK, Tse MY, Cheung RTF, et al. Delays in stroke onset to hospital arrival time during COVID-19. Stroke. 2020;51:2228–2231. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bekelis K, Marth NJ, Wong K, Zhou W, Birkmeyer JD, Skinner J. Primary stroke center hospitalization for elderly patients with stroke: implications for case fatality and travel times. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016;176:1361–1368. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim BR, Lee J, Sohn MK, Kim DY, Lee SG, Shin YI, Oh GJ, Lee YS, Joo MC, Han EY, et al. Risk factors and functional impact of medical complications in stroke. Ann Rehabil Med. 2017;41:753–760. doi: 10.5535/arm.2017.41.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finlayson O, Kapral M, Hall R, Asllani E, Selchen D, Saposnik G. Risk factors, inpatient care, and outcomes of pneumonia after ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2011;77:1338–1345. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823152b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones EM, Albright KC, Fossati-Bellani M, Siegler JE, Martin-Schild S. Emergency department shift change is associated with pneumonia in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:3226–3230. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.613026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams HP, Jr., Davis PH, Leira EC, Chang KC, Bendixen BH, Clarke WR, Woolson RF, Hansen MD. Baseline NIH stroke scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: a report of the trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) Neurology. 1999;53:126–131. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]