Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the national lockdown have led to significant changes in the use of emergency care by the French population.

Aims

To describe the national and regional temporal trends in emergency department (ED) admissions for myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke, before, during and after the first national lockdown.

Methods

The weekly numbers of ED admissions for MI and stroke were collected from the OSCOUR® network, which covers 93.3% of all ED admissions in France. National and regional incidence rate ratios from 02 February until 31 May (2020 versus 2017–2019) were estimated using Poisson regression for MI and stroke, before, during and after lockdown.

Results

A decrease in ED admissions was observed for MI (–20% for ST-segment elevation MI and–25% for non-ST-segment elevation MI) and stroke (–18% for ischaemic and–22% for haemorrhagic) during the lockdown. The decrease became significant earlier for stroke than for MI. No compensatory increase in ED admissions was observed at the end of the lockdown for these diseases. Important regional disparities in ED admissions were observed, without correlation with the regional levels of COVID-19 cases. The impact of lockdown on ED admissions was particularly significant in six regions (Ile-de France, Occitanie, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, Nouvelle Aquitaine, Hauts-de-France and Bretagne).

Conclusions

The decrease in ED admissions for MI and stroke observed during the lockdown was probably caused by fear of COVID-19 and augmented by the lockdown, and was heterogeneous across the French territory. ED admissions were slow to return to the usual levels from previous years, without a compensatory increase. These results underline the need to reinforce messages directed at the population to encourage them to seek care without delay in case of cardiovascular symptoms.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Stroke, COVID-19, Emergency department, Syndromic surveillance

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ED, emergency department; ICD-10, 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases; IRR, incidence rate ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PACA, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Résumé

Contexte

La pandémie COVID-19 et le confinement national ont conduit à des changements importants dans le recours aux soins d’urgences par la population.

Objectifs

Décrire les évolutions nationales et régionales des admissions aux urgences (SU) pour infarctus du myocarde (IM) et AVC avant, pendant et après le premier confinement.

Méthodes

Le nombre hebdomadaire d’admissions aux urgences pour IM et AVC a été collecté auprès du réseau Oscour qui couvre 93,3 % de toutes les admissions aux urgences en France. Les ratios national et régionaux des taux d’incidence du 03 février au 31 mai (2020 versus 2017–2019) et les intervalles de confiance à 95 % ont été estimés à l’aide de la régression de Poisson avant, pendant et après le confinement pour IM et AVC.

Résultats

Une diminution des admissions aux urgences a été observée pour les IM (–20 % pour les STEMI et–25 % pour les NSTEMI) et les AVC (–18 % pour les ischémiques et–22 % pour les hémorragiques) pendant le confinement. La diminution était significative plus précocement pour l’AVC que pour l’IM. Aucune compensation des admissions n’a été observée à la fin du confinement pour ces maladies. D’importantes disparités régionales dans les variations d’admissions aux urgences ont été observées sans corrélation avec le niveau régional d’infection par la COVID-19. L’impact du confinement sur les admissions à l’urgence a été particulièrement marqué dans six régions (Ile-de France, Occitanie, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, Nouvelle Aquitaine, Hauts-de-France et Bretagne).

Conclusions

La diminution des admissions pour IM et AVC aux urgences, observée lors du confinement, probablement en raison de la peur de l’infection au covid-19 et majorée par le confinement, était hétérogène sur le territoire français. Le retour à des taux d’admission aux urgences habituels a été long, sans compensation à la sortie du confinement. Ces résultats soulignent la nécessité de renforcer les messages de prévention adressés à la population pour l’inciter à se faire soigner sans délai en cas de symptômes cardiovasculaires.

Mots clés: Infarctus du myocarde, Accident vasculaire cérébral, Covid-19, Services d’urgence, Surveillance syndromique

Background

In France, the first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was confirmed on 24 January 2020. A first national lockdown of the population lasted from week 12 (16–22 March 2020) to week 19 (04–10 May 2020). The pandemic and the lockdown have led to significant changes in the organization of the healthcare system. In addition, fear of in-hospital infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19, and advice emanating from health authorities and widely reported in the mass media since the beginning of the outbreak, probably led patients to stay at home or to postpone calling the emergency services in case of mild disease symptoms, including cardiovascular symptoms. Several studies have reported pronounced reductions in hospital admissions for myocardial infarction (MI) in different countries [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. On the other hand, results regarding the evolution of hospital admissions for stroke during the lockdown are scarce, and no data have been reported according to the type of stroke [6], [7]. Although some data have highlighted a drop in hospitalization for acute cardiovascular diseases, few data have documented the duration of this decline and whether or not the situation returned to normal with regard to the management of cardiovascular diseases in the weeks following the end of the lockdown [8].

In France, the COVID-19 pandemic spread heterogeneously over the French territory during the first wave of infection. Important regional disparities were observed, with some regions affected early and strongly by the first wave of contamination (Grand Est and then Paris and its suburbs, and Hauts-de-France to a lesser extent) and others affected very little (the South and West of France). In this context, the impact of the pandemic on the health system may have differed between regions. Few data are available regarding the regional impact of the COVID-19 crisis on MI and stroke management in France.

The objective of our study was to describe the national and regional temporal trends in emergency department (ED) admissions for MI (non-ST-segment elevation MI [NSTEMI] and ST-segment elevation MI [STEMI]) and stroke (ischaemic and haemorrhagic), before, during and after the first national lockdown.

Methods

We used the nationwide OSCOUR® data source (Organisation de la surveillance coordonnée des urgences) to describe visits to the ED for acute MI or stroke.

OSCOUR® data

ED data are collected from daily computerized medical records, completed during consultations in hospitals participating in the OSCOUR® network, which grew from 23 hospitals in 2004 to 696 hospitals in 2020, covering 93.3% of all ED visits in France [9].

Transmitted data contain clinical information, with a primary diagnosis and up to five secondary discharge diagnoses, coded using the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). In addition to medical diagnoses, demographic information (date of birth, sex and residential postal code) and administrative information (date and time of admission and discharge, provenance and orientation after ED admission [hospitalization, death, discharge]) are collected. Of interest, information about transport used to reach hospital was available for ED admission: personal vehicle; ambulance; firefighter's vehicle; or mobile emergency and intensive care services (Service Mobile d’Urgence et Reanimation [SMUR]).

Outcome definitions

We studied all ED admission summaries where one of the following ICD-10 codes was recorded for the diagnosis of acute MI (I21 to I23) or stroke (I60 to I64). Among all acute MIs (ICD-10 codes I21 to I23), STEMI were identified using I21.0, I21.1, I21.2, and I21.3 codes; other codes between I21 and I23 were classified as NSTEMI. MIs sent directly to a specific acute care unit are not included in our study. For stroke, the diagnoses of ischaemic stroke (codes I63, I64) and haemorrhagic stroke (codes I60 to I62) were studied.

Geographical area

Because regions (corresponding to the first level of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS1)) [10] were impacted differently by the COVID-19 crisis during the first wave, we hypothesized that the evolution of the use of EDs for cardiovascular diseases would differ according to the level of transmission of COVID-19. Consequently, we grouped regions into four areas ranging from high to moderate transmission of COVID-19, according to the mortality rate observed in the first month of lockdown, i.e. between 14 March and 14 April 2020 [11]. Among the 13 French administrative regions (Table A.1), the Red area covered the two regions with the highest mortality rate (over 25/100,000) (Grand Est and Ile-de-France); the Orange area included four regions with a mortality rate between 15 and 25/100,000 (Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, Hauts-de-France, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Corse); the Yellow area included four regions with a mortality rate between 10 and 15/100,000 (Centre-Val de Loire, Pays de la Loire, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur [PACA] and Normandie); and the Green area covered the three regions with lowest mortality rate (between 1 and 10/100,000) (Occitanie, Bretagne, and Nouvelle Aquitaine).

Statistical analyses

Data from 03 February until 31 May were studied. The study period was divided into three sections: before (weeks 6 to 11), during (weeks 12 to 19) and after (weeks 20 to 22) the lockdown period. The weekly numbers of ED admissions for acute cardiovascular diseases were extracted by subtype of MI (STEMI, NSTEMI) and stroke (ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke). Incidences in 2020 were compared with the mean incidences observed between 2017 and 2019 during the same three periods of the year. Population data to estimate incidences were gathered from the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques [Insee]). Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using Poisson regression for each period and each outcome, overall and according to age group, sex, type of transport used to reach the hospital, region and residential area (Red, Orange, Yellow or Green). Regional IRRs and 95% CIs were also estimated for MI (NSTEMI and STEMI) and stroke (ischaemic and haemorrhagic) subtypes to increase the statistical power to detect significant differences.

All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). No study with human or animal subjects was performed by any of the authors during the development of this article, and data did not include any identifiable private information. Approval from an institutional review board was unnecessary.

Results

Myocardial infarction

In 2020, between 03 February (week 6) and 31 May (week 22), 7916 patients were admitted to an ED for MI (2768 for STEMI and 5148 NSTEMI) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Emergency admissions for myocardial infarction or stroke, before, during and after the lockdown period in Francea, by subjects’ characteristics and transport type.

| STEMI |

NSTEMI |

Ischaemic stroke |

Haemorrhagic stroke |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | During | After | Before | During | After | Before | During | After | Before | During | After | |

| ED admission | 1167 (100) | 1096 (100) | 505 (100) | 2001 (100) | 2090 (100) | 1057 (100) | 9180 (100) | 10,309 (100) | 4505 (100) | 2172 (100) | 2337 (100) | 1025 (100) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 417 (35.7) | 367 (33.5) | 173 (34.3) | 709 (35.4) | 762 (36.5) | 363 (34.3) | 4536 (49.4) | 4968 (48.2) | 2247 (49.9) | 1011 (46.5) | 1116 (47.8) | 487 (47.5) |

| Male | 749 (64.2) | 729 (66.5) | 332 (65.7) | 1292 (64.6) | 1328 (63.5) | 694 (65.7) | 4644 (50.6) | 5339 (51.8) | 2258 (50.1) | 1161 (53.5) | 1221 (52.2) | 538 (52.5) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 15–44 | 80 (6.9) | 71 (6.5) | 38 (7.5) | 107 (5.3) | 104 (5.0) | 54 (5.1) | 529 (5.8) | 451 (4.4) | 211 (4.7) | 188 (8.7) | 177 (7.6) | 78 (7.6) |

| 45–64 | 422 (36.2) | 422 (38.5) | 199 (39.4) | 650 (32.5) | 721 (34.5) | 363 (34.3) | 1897 (20.7) | 2113 (20.5) | 931 (20.7) | 483 (22.2) | 510 (21.8) | 223 (21.8) |

| 65–74 | 270 (23.1) | 224 (20.4) | 100 (19.8) | 481 (24.0) | 459 (22.0) | 246 (23.3) | 1956 (21.3) | 2223 (21.6) | 1002 (22.2) | 426 (19.6) | 450 (19.3) | 203 (19.8) |

| ≥ 75 | 395 (33.8) | 379 (34.6) | 168 (33.3) | 763 (38.1) | 806 (38.6) | 394 (37.3) | 4798 (52.3) | 5522 (53.6) | 2361 (52.4) | 1075 (49.5) | 1200 (51.3) | 521 (50.8) |

| Area | ||||||||||||

| Red | 165 (14.1) | 154 (14.1) | 75 (14.9) | 362 (18.1) | 393 (18.8) | 198 (18.7) | 1561 (17.0) | 1701 (16.5) | 820 (18.2) | 478 (22.0) | 457 (19.6) | 221 (21.6) |

| Orange | 291 (24.9) | 276 (25.2) | 131 (25.9) | 486 (24.3) | 473 (22.6) | 271 (25.6) | 2113 (23.0) | 2412 (23.4) | 1104 (24.5) | 512 (23.6) | 551 (23.6) | 258 (25.2) |

| Yellow | 346 (29.6) | 329 (30.0) | 141 (27.9) | 608 (30.4) | 605 (28.9) | 294 (27.8) | 2267 (24.7) | 2573 (25.0) | 1045 (23.2) | 456 (21.0) | 542 (23.2) | 247 (24.1) |

| Green | 328 (28.1) | 294 (26.8) | 133 (26.3) | 501 (25.0) | 566 (27.1) | 270 (25.5) | 2924 (31.9) | 3252 (31.5) | 1397 (31.0) | 661 (30.4) | 711 (30.4) | 277 (27.0) |

| Other | 37 (3.2) | 43 (3.9) | 25 (5.0) | 44 (2.2) | 53 (2.5) | 24 (2.3) | 315 (3.4) | 371 (3.6) | 139 (3.1) | 65 (3.0) | 76 (3.3) | 22 (2.1) |

| Transport | ||||||||||||

| Ambulance | 208 (17.8) | 266 (24.3) | 106 (21.0) | 386 (19.3) | 530 (25.4) | 235 (22.2) | 2583 (28.1) | 3654 (35.4) | 1452 (32.2) | 507 (23.3) | 661 (28.3) | 277 (27.0) |

| Personal | 456 (39.1) | 327 (29.8) | 198 (39.2) | 681 (34.0) | 569 (27.2) | 341 (32.3) | 2677 (29.2) | 2424 (23.5) | 1211 (26.9) | 442 (20.3) | 427 (18.3) | 194 (18.9) |

| SMUR | 104 (8.9) | 98 (8.9) | 50 (9.9) | 209 (10.4) | 198 (9.5) | 85 (8.0) | 245 (2.7) | 300 (2.9) | 115 (2.6) | 209 (9.6) | 235 (10.1) | 95 (9.3) |

| Firefighters | 216 (18.5) | 212 (19.3) | 80 (15.8) | 409 (20.4) | 415 (19.9) | 186 (17.6) | 2296 (25.0) | 2313 (22.4) | 984 (21.8) | 670 (30.8) | 656 (28.1) | 295 (28.8) |

Data are expressed as number (%). ED: emergency department; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; SMUR: Service Mobile d’Urgence et Reanimation (mobile emergency and intensive care services); STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Before: weeks 6 to 11; during: weeks 12 to 19; after: weeks 20 to 22.

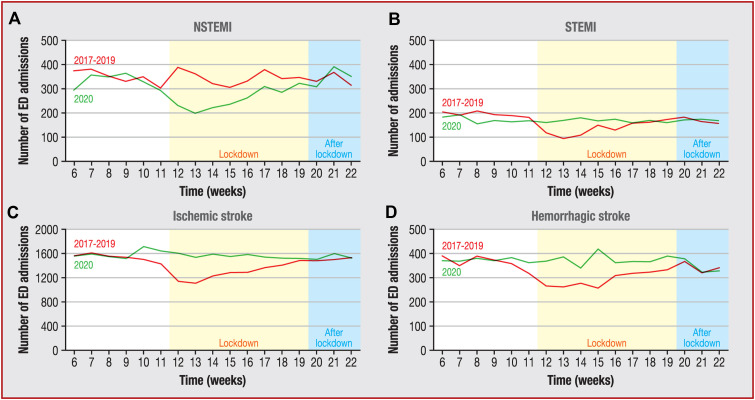

During the lockdown period (weeks 12 to 19), compared with the same weeks in 2017–2019, there was a significant decrease in patients admitted to an ED for STEMI (IRR 0.81, 95% CI 0.75–0.88) and NSTEMI (IRR 0.75, 95% CI 0.71–0.80), reaching its lowest level in week 13 for both (Fig. 1 A and B). The decrease during lockdown was of the same magnitude for both sexes, irrespective of MI type. For NSTEMI, the decrease was more important in those aged 15–44 years (IRR 0.66, 95% CI 0.51–0.84), although it was significant for all age groups (Table 2 ). Finally, the decrease was particularly marked among people who traveled to the ED in their personal vehicle, for both STEMI and NSTEMI.

Figure 1.

Weekly number of emergency department (ED) admissions for myocardial infarction and stroke in France, from weeks 6 to 22 in 2017–2019 and 2020. A. Non-ST-segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). B. ST-segment myocardial infarction (STEMI). C. Ischaemic stroke. D. Haemorrhagic stroke. a Note that the scale of the graph in panel C is different. [Publishers: * to be changed to a in the figure.].

Table 2.

Incidence rate ratio of emergency department admissions between 2020 and 2017–2019 for myocardial infarction, before, during and after the lockdown period in Francea.

| STEMI | NSTEMI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | During | After | Before | During | After | |||||||

| IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | |

| ED admissions | 1.13 (1.04–1.23) | 0.005 | 0.81 (0.75–0.88) | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.87–1.11) | 0.74 | 0.92 (0.87–0.98) | 0.01 | 0.75 (0.71–0.8) | < 0.0001 | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) | 0.37 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 1.17 (1.02–1.35) | 0.03 | 0.81 (0.71–0.93) | 0.003 | 1.09 (0.88–1.35) | 0.44 | 0.89 (0.80–0.98) | 0.02 | 0.76 (0.69–0.83) | < 0.0001 | 0.99 (0.86–1.15) | 0.92 |

| Male | 1.10 (0.99–1.22) | 0.06 | 0.82 (0.74–0.90) | < 0.001 | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 0.35 | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 0.15 | 0.75 (0.70–0.81) | < 0.0001 | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) | 0.23 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 15–44 | 1.08 (0.79–1.49) | 0.61 | 0.77 (0.56–1.05) | 0.10 | 1.18 (0.74–1.88) | 0.49 | 0.91 (0.70–1.18) | 0.48 | 0.66 (0.51–0.84) | 0.001 | 0.75 (0.53–1.07) | 0.11 |

| 45–64 | 1.14 (0.99–1.31) | 0.07 | 0.86 (0.75–0.98) | 0.02 | 0.98 (0.80–1.19) | 0.82 | 0.93 (0.84–1.04) | 0.21 | 0.81 (0.73–0.89) | < 0.0001 | 1.11 (0.95–1.28) | 0.19 |

| 65–74 | 1.26 (1.05–1.51) | 0.01 | 0.75 (0.63–0.89) | 0.001 | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) | 0.38 | 1.10 (0.97–1.26) | 0.14 | 0.73 (0.64–0.82) | < 0.0001 | 1.11 (0.93–1.34) | 0.25 |

| ≥ 75 | 1.03 (0.90–1.19) | 0.67 | 0.80 (0.70–0.92) | 0.001 | 0.99 (0.80–1.22) | 0.90 | 0.82 (0.74–0.90) | < 0.0001 | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | < 0.0001 | 0.98 (0.85–1.12) | 0.76 |

| Transport | ||||||||||||

| Ambulance | 1.13 (0.93–1.38) | 0.22 | 1.23 (1.03–1.47) | 0.03 | 1.32 (0.99–1.77) | 0.06 | 0.89 (0.77–1.02) | 0.08 | 1.01 (0.89–1.13) | 0.93 | 1.23 (1.01–1.49) | 0.03 |

| Personal | 1.17 (1.02–1.34) | 0.02 | 0.63 (0.55–0.72) | < 0.001 | 1.08 (0.88–1.32) | 0.46 | 0.95 (0.85–1.05) | 0.33 | 0.60 (0.54–0.66) | < 0.0001 | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) | 0.86 |

| SMUR | 1.16 (0.88–1.55) | 0.29 | 0.90 (0.68–1.18) | 0.43 | 1.00 (0.67–1.47) | 0.99 | 1.04 (0.86–1.26) | 0.68 | 0.77 (0.64–0.93) | 0.01 | 0.99 (0.73–1.33) | 0.94 |

| Firefighters | 1.23 (1.01–1.50) | 0.04 | 0.88 (0.73–1.06) | 0.18 | 0.81 (0.61–1.09) | 0.17 | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) | 0.91 | 0.84 (0.73–0.95) | 0.01 | 0.97 (0.80–1.19) | 0.80 |

CI: confidence interval; ED: emergency department; IRR: incidence rate ratio; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; SMUR: Service Mobile d’Urgence et Reanimation (mobile emergency and intensive care services); STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Before: weeks 6 to 11; during: weeks 12 to 19; after: weeks 20 to 22.

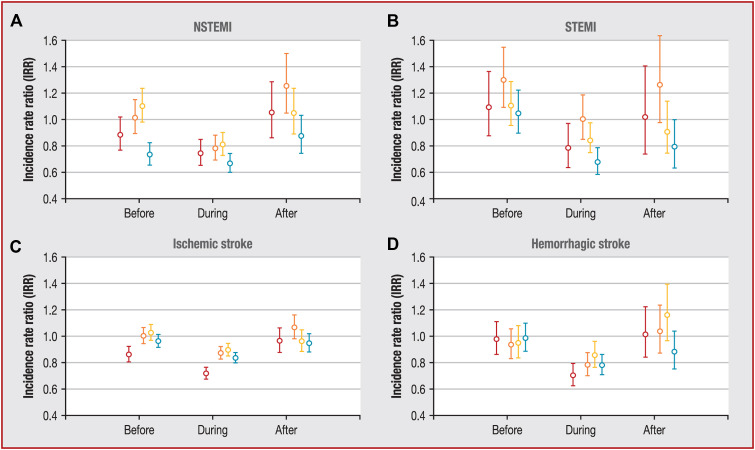

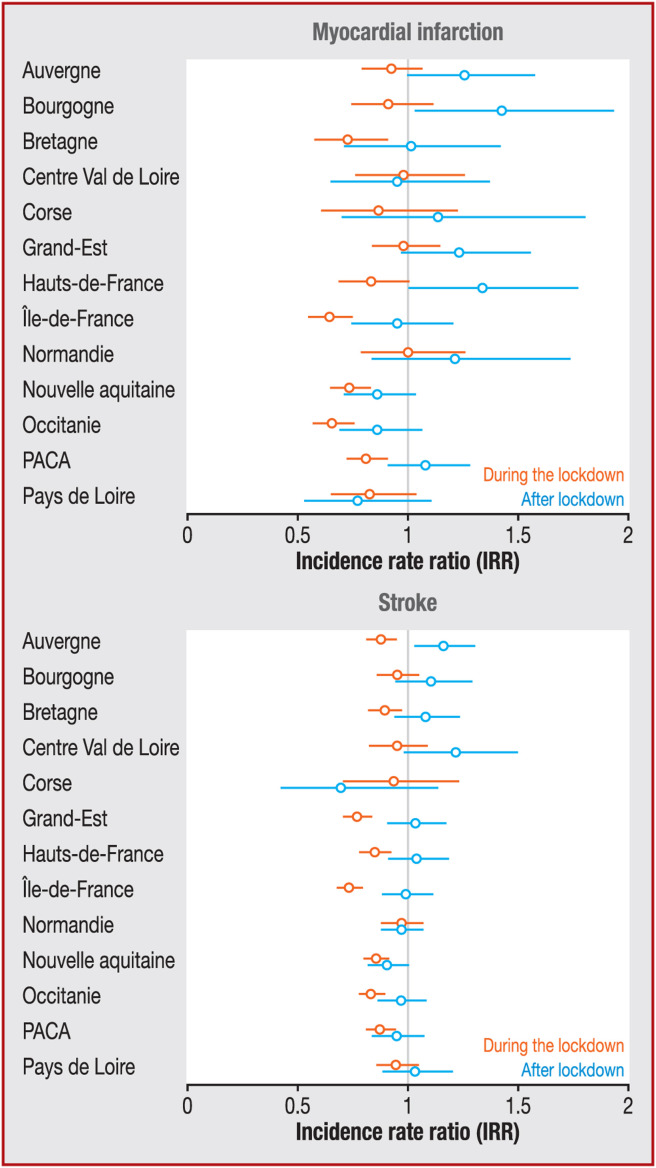

The decrease in the level of ED admission during the weeks of lockdown was independent of the local spread of COVID-19 transmission, as we observed significant decreases in the Green, Yellow, Orange and Red geographical areas for STEMI, and in the Green, Yellow and Red areas for NSTEMI (Fig. 2 A and B). On the contrary, regional discrepancies in MI ED admission levels during the weeks of lockdown were observed within regions similarly affected by COVID-19. For instance, in the Red area, the drop in admissions was statistically significant in Ile-de-France (IRR 0.60, 95% CI 0.52–0.71), but non-significant in Grand-Est (IRR 0.94, 95% CI 0.80–1.10). Similarly, in regions less affected by COVID-19 (Green area), the drop in admissions varied significantly from one region to another (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 2.

Incidence rate ratios of emergency department admissions between 2020 and 2017–2019 for myocardial infarction and stroke, before (weeks 6 to 11), during (weeks 12 to 19) and after (week 20 to 22) the lockdown period in France, by geographical area. A. Non-ST-segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). B. ST-segment myocardial infarction (STEMI). C. Ischaemic stroke. D. Haemorrhagic stroke. The Red area (-●-) included Grand Est and Ile-de-France (COVID-19 mortality rate over 25/100,000); the Orange area (-●-) included Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, Hauts-de-France, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Corse (mortality rate between 15 and 25/100,000); the Yellow area (-●-) included Centre-Val de Loire, Pays de la Loire, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and Normandie (mortality rate between 10 and 15/100,000); and the Green area (-●-) included Occitanie, Bretagne and Nouvelle Aquitaine (mortality rate between 1 and 10/100,000).

Figure 3.

Regional incidence rate ratios of emergency department admissions between 2020 and 2017–2019 for myocardial infarction and stroke, during (black line) and after (grey line) the lockdown period in France. PACA: Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur.

An increase in ED admissions for MI started in week 14, and returned to 2017–2019 levels in week 17 (data not shown). The return to normal ED admission levels occurred earlier for STEMI than for NSTEMI (Fig. 1, Fig. A.1A and Fig. A.1B). In the Green area, the return to usual NSTEMI admission levels was later (weeks 20 to 22) than in the Red area (weeks 16 to 17) (Fig. A.1A and Fig. A.1B). By the end of May 2020, all regions had regained usual levels of ED admissions, except for two Green regions: Occitanie for STEMI (IRR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.99); and Nouvelle Aquitaine for NSTEMI (IRR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.99) (Fig. A.2A and Fig. A.2B).

Stroke

In 2020, between 03 Feb (week 6) and 31 May (week 22), 29,528 patients were admitted to an ED for stroke (23,994 for ischaemic stroke and 5534 for haemorrhagic stroke) (Table 1).

There was a significant decrease in the incidence of patients admitted to an ED for ischaemic stroke (IRR 0.84, 95% CI 0.82–0.86) and haemorrhagic stroke (IRR 0.78, 95% CI 0.74–0.82) during the lockdown period (weeks 12 to 19). The decrease in ED admissions for stroke started earlier than for MI. At a national level, the lowest level was reached in week 13 for ischaemic stroke and in week 15 for haemorrhagic stroke (Fig. 1C and Fig. 1D). Similarly to MI, no difference in the level of admissions for stroke was observed by sex during the lockdown, but the decrease was more pronounced in those aged 15–44 years (IRR 0.71, 95% CI 0.63–0.80 for ischaemic stroke; and IRR 0.64, 95% CI 0.53–0.77 for haemorrhagic stroke) and among people who traveled to the ED in their personal vehicle or were transported by firefighters (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Incidence rate ratio of emergency department admissions between 2020 and 2017–2019 for stroke, before, during and after the lockdown period in Francea.

| Ischaemic stroke | Haemorrhagic stroke | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | During | After | Before | During | After | |||||||

| IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | IRR (95% CI) | P | |

| ED admissions | 0.97 (0.94–1) | 0.05 | 0.84 (0.82–0.86) | < 0.0001 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.40 | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.19 | 0.78 (0.74–0.82) | < 0.0001 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 0.99 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | 0.01 | 0.81 (0.78–0.85) | < 0.0001 | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.55 | 0.91 (0.83–0.99) | 0.02 | 0.78 (0.73–0.85) | < 0.0001 | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) | 0.93 |

| Male | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.71 | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | < 0.0001 | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.56 | 1.02 (0.94–1.1) | 0.71 | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) | < 0.0001 | 1.00 (0.88–1.12) | 0.95 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 15–44 | 1.08 (0.96–1.23) | 0.20 | 0.71 (0.63–0.80) | < 0.0001 | 0.78 (0.65–0.94) | 0.01 | 0.97 (0.79–1.18) | 0.76 | 0.64 (0.53–0.77) | < 0.0001 | 0.81 (0.60–1.09) | 0.17 |

| 45–64 | 0.98 (0.92–1.05) | 0.58 | 0.84 (0.79–0.89) | < 0.0001 | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) | 0.54 | 0.94 (0.83–1.07) | 0.35 | 0.75 (0.67–0.84) | < 0.0001 | 1.00 (0.83–1.20) | 1.00 |

| 65–74 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 0.71 | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | < 0.0001 | 1.01 (0.92–1.10) | 0.84 | 1.00 (0.87–1.14) | 0.96 | 0.80 (0.71–0.91) | 0.001 | 0.96 (0.79–1.17) | 0.69 |

| ≥ 75 | 0.93 (0.90–0.97) | 0.00 | 0.83 (0.80–0.86) | < 0.0001 | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.49 | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 0.14 | 0.80 (0.74–0.86) | < 0.0001 | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | 0.56 |

| Transport | ||||||||||||

| Ambulance | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 0.01 | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 0.83 | 1.10 (1.02–1.19) | 0.01 | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) | 0.22 | 0.89 (0.81–0.99) | 0.04 | 1.14 (0.96–1.35) | 0.14 |

| Personal | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.02 | 0.73 (0.69–0.77) | < 0.0001 | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 0.78 | 1.02 (0.89–1.16) | 0.77 | 0.74 (0.65–0.83) | < 0.0001 | 0.99 (0.81–1.21) | 0.95 |

| SMUR | 0.75 (0.64–0.89) | 0.001 | 0.78 (0.67–0.91) | 0.002 | 0.81 (0.64–1.04) | 0.10 | 0.90 (0.74–1.08) | 0.26 | 0.79 (0.66–0.93) | 0.01 | 0.90 (0.68–1.19) | 0.47 |

| Firefighters | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | 0.94 | 0.80 (0.75–0.84) | < 0.0001 | 0.89 (0.81–0.97) | 0.01 | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) | 0.42 | 0.73 (0.66–0.80) | < 0.0001 | 0.93 (0.80–1.09) | 0.39 |

CI: confidence interval; ED: emergency department; IRR: incidence rate ratio; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; SMUR: Service Mobile d’Urgence et Reanimation (mobile emergency and intensive care services); STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Before: weeks 6 to 11; during: weeks 12 to 19; after: weeks 20 to 22.

The decrease in ED admissions for stroke was significant in all geographical areas during the lockdown period for both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. Regional dynamics of ED admissions for all stroke are described in Fig. 3B. The ED admissions were significantly lower in Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes, Ile-de-France, Grand-Est, Hauts-de-France, Bretagne, Nouvelle Aquitaine, Occitanie and PACA during the lockdown.

An increase in ED admissions for ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke started in week 14 and returned to 2017–2019 levels in week 19 (data not shown). The return to usual admission levels for both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke was later in the Green area (weeks 20 to 22) than in the Red area (weeks 18 to 19) (Fig. 1C, Fig. 1D, Fig. A.1C and Fig. A.1D). By the end of May 2020, the ED admission level remained lower in Nouvelle Aquitaine (IRR 0.86, 95% CI 0.76–0.96) and PACA (IRR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75–0.99) for ischaemic stroke, and in Occitanie for haemorrhagic stroke (IRR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58–1.00) (Fig. A.2C and Fig. A.2D).

Discussion

Results from our study showed a significant reduction in ED admissions for acute cardiovascular diseases, with a marked impact in younger age groups and a later return to 2017–2019 levels for stroke and NSTEMI. Regional disparities in ED admissions were observed without correlation to the regional level of COVID-19 transmission. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on ED admissions for acute cardiovascular diseases was particularly marked in six regions (Ile-de France, Occitanie, PACA, Nouvelle Aquitaine, Hauts-de-France and Bretagne) and in Grand-Est for stroke.

Our results regarding the decrease in ED admissions for MI during the lockdown are consistent with those reported from Northern Italy, Austria and Northern California [3], [4], [12], and those described from other data sources in France [1], [2], [5]. In those studies, a 20–40% decrease in MI hospitalization was observed, with a more pronounced decrease in NSTEMI compared with STEMI [1], [8]. For stroke, few nationwide data have been published, with contrasting results. A Norwegian study reported a reduction in the incidence of stroke during the lockdown, whereas no relevant difference was observed between 2019 and 2020 in the total number of patients admitted for ischaemic stroke in an Italian hospital [7]. To our knowledge, no data according to the subtype of stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) has been previously published [6], [7].

In our study, the most important decrease was observed among patients who traveled to the ED in their personal vehicle. These patients were probably those with transient or less severe forms of stroke or MI, or with least typical symptoms. The greater decline observed in admissions for NSTEMI than for STEMI corroborates this finding.

While we cannot exclude that reductions in professional physical effort, stress and air pollution–three triggers of acute cardiovascular diseases–during the lockdown period may have resulted in a decrease in the incidence of MI and stroke, the main hypothesis to explain the drop in ED admission is people's fear of coming to hospital during the pandemic [13]. At the beginning of the outbreak, messages from medical doctors and health authorities asking people with non-serious symptoms to stay at home were widely spread by the media to the French population. Thus, it is likely that many people did not want to disturb emergency services or feared getting COVID-19 if they went into the hospital, and therefore postponed their admission in ED. Results from previous studies support this hypothesis. In a study by Kristoffersen et al., a reduced proportion of patients reaching hospital with stroke, the symptoms of which had lasted for less than 4.5 hours, was reported during the lockdown [6]. In addition, a French study showed an increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests, supporting the hypothesis that the decrease in early use of care and delayed management would lead to an increase in out-of-hospital mortality, probably as a result of delayed management. However, this increase was limited to the first 2 weeks of lockdown [14].

This study raises fears of a delay in the management of patients that could result in more complications and hospital mortality, but also an increase in out-of-hospital cardiovascular mortality [14], [15]. The first French results showed a non-significant increase in hospital deaths [1], but some studies have shown increased severity of stroke or MI in other countries [6], [15]. Several prevention messages for the population were redesigned early in April by the French health authorities and the Neurovascular Society and the French Society of Neuroradiology, to encourage people with cardiovascular disease symptoms to consult or call the emergency services. These messages and the communication around the implementation of different management pathways for patients with COVID-19 did not result in a rapid return to usual rates, particularly for stroke. Overall, it is now necessary to study more broadly the location of death by MI and stroke during lockdown weeks, as well as the possible impact of delayed management (length of hospitalization, severity of the disease at entrance, in-hospital mortality, sequelae, etc.), to clarify how the drop in ED admissions observed translates in terms of the burden of cardiovascular diseases.

The observed decrease in ED admissions for cardiovascular disease seems to be independent of the level of prevalence of COVID-19 at the regional level. Indeed, the decrease in ED admissions for acute cardiovascular disease does not seem to be related to hospitals being inundated in the Red area of the French territory. However, regional disparities were observed, with different dynamics of return to usual levels. It remains difficult to understand and fully explain each regional trend because of the possible contribution of several phenomena that are difficult to estimate. One of these is the different local prehospital and in-hospital reorganizations to prioritize COVID-19 management and create dedicated COVID-19 units. In the most affected regions, some patients could have been redirected to different hospitals because of reallocation of stroke or cardiology units as COVID-19 units. In addition, as shown in our results, there was also a drop in patients traveling to EDs in their personal vehicle. This result highlighted the important psychological impact of lockdown, irrespective of hospital reorganization, and we cannot exclude that this psychological impact may have been different in each region, where socioeconomical and environmental conditions may differ. Indeed, modification of people's perception of the risk of going to the hospital by local health messages and regional saturation of emergency call platforms (Service d’aide médicale urgente [SAMU] in France) may have had differing effects across the territory in people who were slightly or transiently symptomatic. Finally, we cannot exclude that the reduction in air pollution exposure may have had a most important impact in urbanized regions such as Ile-de-France, and may have led to a more pronounced reduction in ED admissions linked to a true decrease in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases.

Study strengths and limitations

This study, covering more than 90% of ED admissions throughout France, is the first to provide an estimate of the date of return to usual admission rates for MI and stroke at national and regional levels. The large number of ED admissions allowed us to present the results by subtype of MI and stroke, and by region. The comparison of admission levels with the average of the previous 3 years was a strength of our work. Indeed, in several studies, the comparison of admission levels during the outbreak was carried out between the first weeks of lockdown and the previous weeks of February and early March [1], [6], [8]. In these studies, given the seasonality of MI and stroke, with higher rates in winter, the observed decline in admissions could have been augmented by naturally higher levels in winter, in previous weeks.

There were several limitations to this study. First, data presented are ED admissions, not hospitalizations for MI and stroke. Most stroke cases are admitted to the ED for cerebral imaging and, in our study, nearly 90% of patients admitted to an ED were hospitalized. However, as patients with MI could be referred directly to a cardiology department, without going through an ED, our study reflected only a part of MI management. It is possible that part of the decrease in ED admissions for MI may reflect an increase in the management of these patients in acute cardiology units through prehospitalized triage. However, similar results focusing on MI hospitalization have been described [1]. Second, no detailed information, medical co-morbidities or personal histories of cardiovascular disease of patients are gathered in ED admission data. Thus, we could not compare the profiles of the patients admitted in 2020 with those admitted in previous years and, in particular, the severity of the pathologies. Finally, the lack of details regarding delay to admission and mortality limited the interpretation of these trends.

Conclusions

The impact of COVID-19 on acute cardiovascular disease ED admissions was significant during the lockdown, with marked regional disparities. ED admissions were slow to return to the usual level of previous years, without a compensatory increase. These results underline the need to reinforce messages to the population to encourage them to seek care without delay in case of cardiovascular symptoms.

Funding

None.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Tweet: The decrease in emergency department admissions for MI and stroke observed during the lockdown was probably caused by fear of COVID-19 and was heterogeneous across the French territory. Levels of admissions were slow to return to the usual levels from previous years.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2021.01.006.

Online Supplement. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Mesnier J., Cottin Y., Coste P., et al. Hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction before and after lockdown according to regional prevalence of COVID-19 and patient profile in France: a registry study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e536–e542. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lantelme P., Couray Targe S., Metral P., et al. Worrying decrease in hospital admissions for myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;113:443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon M.D., McNulty E.J., Rana J.S., et al. The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Incidence of Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:691–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzler B., Siostrzonek P., Binder R.K., Bauer A., Reinstadler S.J. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1852–1853. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huet F., Prieur C., Schurtz G., et al. One train may hide another: Acute cardiovascular diseases could be neglected because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;113:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kristoffersen E.S., Jahr S.H., Thommessen B., Ronning O.M. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on stroke admission rates in a Norwegian population. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ane.13307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisullo G., Brunetti V., Di Iorio R., et al. Effect of lockdown on the management of ischemic stroke: an Italian experience from a COVID hospital. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:2309–2313. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04545-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mafham M.M., Spata E., Goldacre R., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet. 2020;396:381–389. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caserio-Schonemann C., Meynard J.B. Ten years experience of syndromic surveillance for civil and military public health, France, 2004-2014. Euro Surveill. 2015;20:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS). Available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/background.

- 11.Hubert B., Gagnière B., Pivette M., Desenclos J.-C. Santé Publique France; Saint-Maurice: 2020. Scénarios du nombre de décès, d’hospitalisations et d’admissions en réanimation construits à partir des caractéristiques des cas de COVID-19 observés dans la province de Hubei, Chine. Comparaison avec les caractéristiques des patients hospitalisés en France avec un diagnostic de grippe de 2012 à 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Filippo O., D’Ascenzo F., Angelini F., et al. Reduced Rate of Hospital Admissions for ACS during Covid-19 Outbreak in Northern Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:88–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larrieu S., Jusot J.F., Blanchard M., et al. Short term effects of air pollution on hospitalizations for cardiovascular diseases in eight French cities: the PSAS program. Sci Total Environ. 2007;387:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marijon E., Karam N., Jost D., et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic in Paris, France: a population-based, observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e437–e443. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Rosa S., Spaccarotella C., Basso C., et al. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-19 era. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2083–2088. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.