Abstract

We investigate the performance of SRI/ESG investments against conventional investments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although previous studies have examined the performance of SRI during financial crises, little is known about their performance during the COVID-19 crisis. Applying asset-pricing models, we analyze returns, abnormal returns, and the Sharpe ratio of the ESG ETFs in the US and the MSCI SRI indices for the world, the US, Japan, and Europe before and during the pandemic period vis-à-vis conventional investments. Our results confirm the greater outperformance of SRI indices during the pandemic. These findings have academic and practical implications.

Keywords: COVID-19, ESG, SRI, MSCI, ETF, Financial crisis

1. Introduction

Since the first official case was reported in mid-January 2020, COVID-19 has rapidly spread throughout the world. The number of estimated global active cases,1 based on information from Johns Hopkins University and Bloomberg, have risen sharply from 50,000 in February to 1,000,000 in April and to over 10,000,000 in October 2020. The financial markets reacted very strongly to this pandemic.

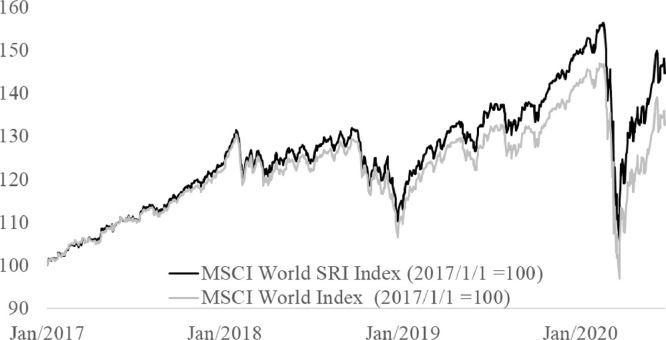

With this pandemic, responsible investing2 is expected to attract further attention from investors (see, e.g., Aegon Asset Management 2020; J.P. Morgan 2020). Indeed, the apparent overperformance of the MSCI socially responsible investing (SRI) index amplifies the attractiveness of this type of investment (Figure 1 ). However, as can also be seen, this overperformance was already observed prior to COVID-19, and several studies have documented this phenomenon (see, e.g., Kempf & Osthoff 2007; Auer 2016). Therefore, market participants (e.g., investors) would be interested in knowing whether this outperformance becomes even greater in crisis periods such as during the current pandemic and whether this greater outperformance can continue to be attributed to SRI or to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors.3

Figure 1.

Performance of the MSCI World Net Return Index and the MSCI World SRI Net Return Index.

A number of studies have provided theoretical explanations as well as empirical analyses on why socially responsible or sustainable investments outperform conventional investments; we mention here three of the most important reasons.4 These studies claim and have shown that sustainable businesses improve their social image and are therefore able to differentiate themselves and their products from other companies. These companies in turn enjoy brand loyalty from customers who value sustainability. Hence, sustainability creates brand equity and brand loyalty for responsible businesses (see, e.g., Heal 2005; Flammer 2015; Albuquerque et al. 2019; Albuquerque et al. 2020). This then translates into higher profitability and reduces the sensitivity of responsible businesses against systematic risk and economic downturns.

Another important reason cited by studies as to why responsible businesses outperform is that these businesses often have high-quality or good management (see, e.g., Heal 2005; Siddiq & Javed 2014; Aegon Asset Management 2020). It can be argued that responsible businesses attract managers who are ethical and have desirable values in terms of how they conduct business, treat employees, and relate to customers and society in general. This results in these businesses being well run, leading to higher productivity and organizational performance, increased sales, and eventually higher profits.

Furthermore, studies argue and have empirically demonstrated that responsible businesses attract loyal investors (see, e.g., Bollen 2007; Benson & Humphrey 2008; Scalet & Kelly 2010; Nofsinger & Varma 2014; Becchetti et al. 2015; Nakai et al. 2016; Chiappini & Vento 2018). These investors who are motivated by nonfinancial reasons such as ESG concerns, stick with responsible companies even during crisis periods when investors in general will be selling off.

There is a scarcity of studies on the relative performance of responsible investments vis-à-vis conventional investments during economic downturns, and the results are mixed. Some find that responsible investments outperform conventional investments (e.g., Nofsinger & Varma 2014; Becchetti et al. 2015; Nakai et al. 2016; Tripathi & Bhandari 2016; Wu et al. 2017; Risalvato et al. 2019; Arefeen & Shimada 2020). By contrast, others find opposing results (e.g., Morales et al. (2019) or no difference or mixed results (e.g., Leite & Cortez 2015; Chiappini & Vento 2018; Lean & Pizzutilo 2020). An increasing number of academic studies have examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the financial markets (see, e.g., Broadstock et al. 2020; Cepoi 2020; Folger-Laronde et al. 2020; Heyden & Heyden 2020; Rahman et al. 2020; Sakurai & Kurosaki 2020; Shehzad et al. 2020; Sherif 2020; Singh 2020). However, the knowledge on the performance of SRI/ESG against conventional investment practices during this pandemic has yet to be developed. To address this gap, we analyze the performance of the SRI indices and ESG funds before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and compare them to conventional indices while controlling for confounding factors. This study therefore aims to provide an early analysis on how responsible investing performs amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our analysis on the SRI indices confirms that they outperform conventional indices before and during the COVID-19 crisis period. This finding is supported even after controlling for other risk factors (e.g., the Fama–French five factors). By contrast, the exchange-traded funds (ETF) focusing on responsible investments fail to obtain superior performance against the benchmark indices. The results of the ETFs might have been affected by the mix of positive and negative screening strategies utilized by funds, which may have diluted the responsible investment factors. Furthermore, the presence of the ETF management fees and the time required to reflect benchmark changes may have affected the results.

Our contribution is threefold. First, we add new evidence on the resilience of SRI/ESG investments to economic downturn. Second, our analyses provide valuable information on how investors can benefit from responsible investing. Third, our study offers an early analysis of the performance of responsible investing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our analysis assumes that the COVID-19 pandemic began when the globally confirmed cases exceeded 10,000. To check the robustness of our results, we reconduct the analyses using different pandemic starting dates (i.e., when cases exceeded 20,000, 30,000, 40,000, and 50,000). Our conclusion remains unchanged.

2. Data and methodology

To examine the performance (based on the annualized returns, the Sharpe ratio, and the abnormal returns) of responsible investing before and during the COVID-19 pandemic period, we analyze the performance of the ESG ETFs traded in the US market5 and the MSCI SRI Net Return Indices for the world, the US, Japan, and Europe.6 The ESG ETFs are identified from the list of entire ETFs based on the description of the funds. Overall, we examine four SRI indices and 24 funds. We use the corresponding MSCI Net Return Indices as the market benchmarks. The daily data for those from January 1, 2018 to June 24, 2020 are obtained from Refinitiv DataScope. The pandemic period is determined by the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the world available on the Johns Hopkins University's website.7 Our main analysis assumes that the pandemic started on February 1, 2020 when the number of global cases exceeded 10,000.

The annualized returns used in the analyses are calculated by

| (1) |

where rj is the annualized return of an ETF or MSCI Index, j. To analyze the performance of the sample ETFs, we use the average performance of all ETFs considered in a trading day. Then, the simplified Sharpe ratio is estimated by

| (2) |

where Sharpe is the simplified daily rolling Sharpe ratio, and σ is the standard deviation of the annualized daily returns of an ETF or MSCI Index, j. We use the 30-trading-day rolling standard deviation to capture enough lengths of information in the estimation while minimizing the influence of the pre-pandemic period.

These estimates are then compared against the same performance measures for the corresponding benchmark. For example, the MSCI World Index is used against the MSCI SRI World Index. Furthermore, to examine whether the SRI/ESG performance changes during the pandemic, we compute the excess SRI indices and ESG fund performance measured by subtracting the performance of the benchmark indices from those of the SRI indices and ESG funds. We then compare these excess performance measures before and during the pandemic.

We also analyze the abnormal returns of the SRI/ESG before and during the pandemic. The abnormal returns are estimated by subtracting expected returns from the actual returns. The expected returns are estimated as

| (3) |

where ri is the annualized daily returns of the MSCI SRI Index for country or region j (either the US, Japan, or Europe) or of the ESG ETFs. MSCIj is the MSCI Index corresponding to the region or country used as an explained variable.

To determine whether the sustainability or ESG factor continues to exist or strengthens during the pandemic period, we further conduct panel regression analyses based on the random-effect model before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, using both conventional and SRI MSCI Indices as the explained variables. In the analysis, we include an ESG/SRI dummy to determine if the SRI indices perform better than the conventional MSCI Indices. The regression model is

| (4) |

where SRIDummy is the MSCI SRI Index dummy that takes the value of one if the explained variable is the MSCI SRI Index and zero otherwise. Control is the control variables, which are the five factors introduced by Fama and French (2015): market, size, value, profitability, and investment.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the annualized daily returns of the main variables used in this study. The analysis reveals that, although the SRI indices perform better than the conventional MSCI Indices, the ESG funds perform poorly. Considering the variability of the return series, the SRI indices also offer higher risk-adjusted returns. In the next section, we conduct the analysis explained above.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (annualized log-transformed daily returns).

| Funds | MSCI SRI Indices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG Funds | World | US | Japan | Europe | |

| Mean | -0.010 | 0.057 | 0.095 | 0.014 | 0.016 |

| Min | -31.384 | -23.153 | -29.171 | -14.382 | -29.605 |

| Max | 16.467 | 19.851 | 21.794 | 14.529 | 18.660 |

| Kurtosis | 25.484 | 22.461 | 18.808 | 7.940 | 28.963 |

| Skewness | -2.367 | -1.310 | -0.844 | 0.080 | -2.022 |

| Std. Div. | 3.274 | 2.841 | 3.565 | 2.511 | 2.756 |

| MSCI Indices | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | US | Japan | Europe | ||

| Mean | - | 0.027 | 0.061 | -0.008 | -0.030 |

| Min | - | -23.461 | -29.067 | -14.664 | -31.598 |

| Max | - | 18.930 | 20.226 | 15.977 | 19.206 |

| Kurtosis | - | 21.914 | 18.891 | 9.556 | 29.634 |

| Skewness | - | -1.467 | -1.041 | 0.121 | -2.115 |

| Std. Div. | - | 2.890 | 3.500 | 2.457 | 2.912 |

Notes: For ESG funds, the average value of daily returns of the SRI/ESG ETFs listed in the US is used.

3. Empirical results

3.1. SRI/ESG performance before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

We first analyze the recent performance of the SRI indices and ESG funds against the conventional MSCI Indices. Panels A and B of Table 2 show that, over the entire sample period and before the COVID-19 pandemic, the MSCI SRI Indices produce higher average returns than the conventional MSCI Indices and they are significantly positive except for Japan. The performance remains superior, even when the risk-adjusted returns (i.e., the Sharpe ratio) are used in the analysis. Therefore, the responsible investment factor appears to help in selecting better performing companies. Panel C of Table 2 shows the excess average returns of SRI indices and ESG funds over the conventional MSCI Indices during the pandemic. We again see the superior performance of the SRI indices, especially for the risk-adjusted measures, except for Japan. Thus, the sustainability factor continues to positively affect the performance of these SRI indices.

Table 2.

Performance of SRI/ESG funds/indices against MSCI Indices (performance and t-test).

| Panel A: Full Sample Period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funds | MSCI SRI Indices | ||||

| ESG Funds | World | US | Japan | Europe | |

| Diff. Return | -0.040 | 0.028⁎⁎ | 0.034⁎⁎ | 0.022 | 0.047⁎⁎⁎ |

| Diff. Sharpe | -0.015 | 0.021⁎⁎⁎ | 0.021⁎⁎ | 0.018* | 0.033⁎⁎⁎ |

| Panel B: Before COVID-19 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funds | MSCI SRI Indices | ||||

| ESG Funds | World | US | Japan | Europe | |

| Diff. Return | -0.057 | 0.020⁎⁎ | 0.025* | 0.016 | 0.030⁎⁎ |

| Diff. Sharpe | -0.024 | 0.017⁎⁎ | 0.017* | 0.016 | 0.025⁎⁎⁎ |

| Panel C: During COVID-19 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funds | MSCI SRI Indices | ||||

| ESG Funds | World | US | Japan | Europe | |

| Diff. Return | 0.047 | 0.069* | 0.082 | 0.053 | 0.132⁎⁎ |

| Diff. Sharpe | 0.031 | 0.039* | 0.043* | 0.027 | 0.071⁎⁎ |

Notes: The table presents the tests comparing the performance of the SRI/ESG funds/indices and MSCI Indices estimated using Eqs (1) and (2). The tests are conducted with the hypotheses of H0: SRI Index/Fund = MSCI, Ha: SRI Index/Fund > MSCI. Panel A examines the difference in the performances using the full sample period, Panel B examines the period before the COVID-19, and Panel C examines the COVID-19 period. The pandemic period is defined as that after the confirmed cases of COVID-19 exceeded 10,000 (February 1, 2020) until the end of our sample period (June 24, 2020). The second column compares the performances of the ESG funds and the MSCI World Index. The third column compares the performances of the MSCI SRI World and MSCI World Indices. The fourth column compares the MSCI SRI US and MSCI US Indices, the fifth column compares the MSCI SRI Japan and MSCI Japan Indices, and the sixth column compares the MSCI SRI Europe and the MSCI Europe Indices. “Diff. Return” presents the difference in the returns of the SRI/ESG funds/indices and the MSCI Indices. “Diff. Sharpe” shows the differences in the Sharpe ratios. The Sharpe ratios are estimated using the 30-trading-day rolling standard deviations of the annualized returns. t-tests are conducted. ***, **, and * indicate the coefficient is significant at the 10, 5, and 1% levels, respectively.

By contrast, the ETFs fail to obtain positive excess returns over our sample period, including during the pandemic. As shown in the latter part of this section, the ETFs continually fail to show superior performance against our benchmarks. This may be caused by a fundamental issue pointed out in the literature (e.g., Derwall et al. 2011; Friede et al. 2015). ESG factors are unable to help improve investment performance as these are canceled out via the mixture of positive and negative SRI/ESG screening strategies. This is considered to be one of the main reasons why many of the SRI/ESG portfolio studies8 fail to show superior performances, and, because we average the multiple ETFs to conduct the analyses, this might be the most valid reason for our finding. Furthermore, the results may be also affected by the presence of fees (0.44% per year on average according to Washington Journal9 ) and the time required for funds to reflect changes in benchmarks (viz. passive funds). These issues should be explored in future research.

To examine whether the SRI/ESG effects amplify during the COVID-19 period, we estimate the excess annualized returns by subtracting the benchmark index return from the SRI/ESG return. For the Sharpe ratio analysis, we re-estimate it by using the excess annualized returns. Then, we compare the performance of those measures before and during the pandemic period. The results presented in Table 3 show that the MSCI SRI World and Europe Indices outperform the benchmark on both measures. The results show that the excess performance may be indifferent during the two periods for the other two SRI indices.

Table 3.

Excess performance of SRI/ESG funds/indices before vs. during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Funds | MSCI SRI Indices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG Funds | World | US | Japan | Europe | |

| Diff. Exc. Return | -0.104 | 0.049* | 0.057 | 0.037 | 0.101⁎⁎ |

| Diff. Exc. Sharpe | -0.088 | 0.084* | 0.076 | 0.029 | 0.134⁎⁎ |

Notes: The table provides the results of t-tests comparing the excess returns of SRI/ESG funds/indices (excess to the MSCI Indices) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (H0: Excess SRI Index/Fund During COVID-19 = Before COVID-19, Ha: Excess SRI Index/Fund During COVID-19 > Before COVID-19). “Diff. Exc. Return” presents the difference in the excess returns between before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Diff. Exc. Sharpe” shows the differences in the Sharpe ratios. The Sharpe ratios are estimated using the 30-trading-day rolling standard deviations of the annualized excess returns. t-tests are conducted. ***, **, and * indicate the coefficient is significant at the 10, 5, and 1% levels, respectively.

3.2. Abnormal returns during the COVID-19 pandemic

We next analyze the abnormal returns of the SRI/ESG indices while controlling for the market factor. Table 4 reveals that the average values of the annualized abnormal returns obtained for MSCI SRI Indices are significantly positive, except for Japan. Table 4 also presents the result of the t-test examining whether or not the abnormal returns observed in the MSCI SRI Indices change during the pandemic period, and indicates that such returns are significantly higher during the pandemic in Europe.

Table 4.

Abnormal returns of SRI/ESG funds/indices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Funds | MSCI SRI Indices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG Funds | World | US | Japan | Europe | |

| Ave. Ab. Return | -0.004 | 0.089⁎⁎ | 0.107* | 0.082 | 0.155⁎⁎ |

| Diff. Ab. Return | -0.097 | 0.045 | 0.071 | 0.033 | 0.086⁎⁎ |

Notes: The table presents the abnormal returns of SRI/ESG. “Ave. Ab. Return” is the average abnormal returns obtained during the COVID-19 pandemic and the tests are conducted with the hypotheses of “H0: Abnormal Returns During COVID-19 = 0, Ha: Abnormal Returns During COVID-19 > 0”. “Ab. Diff. Return” is the difference in the average abnormal returns before and during the COVID-19 period (during pandemic – before pandemic). The tests are conducted with the hypotheses of “H0: Difference in Abnormal Returns = 0, Ha: Difference in Abnormal Returns > 0”. The abnormal return is estimated by taking the difference between actual and expected returns. The expected return is calculated on an out-of-sample basis using Eq. (3). For Ave. Ab. Return, the period of 2 years prior to the start of the pandemic is used to obtain the coefficients for the expected return estimation. For Diff. Ab. Return, to avoid in-sample bias in the abnormal return estimation for before COVID-19, we use the sample during 2018 to estimate the coefficients and then use them to estimate the out-of-sample expected returns for before 2019 and during the COVID-19 period. Information on the COVID-19 cases is obtained from Johns Hopkins University. ***, **, and * indicate the coefficient is significant at the 10, 5, and 1% levels, respectively.

3.3. SRI/ESG incentive before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

To assess further the robustness of our results, we conduct a panel regression analysis using the random-effect model presented in Eq. (4), which controls for not only the market factor but also other factors based on the Fama–French five-factor model.10 Our analyses incorporate the returns calculated for both conventional and SRI MSCI Indices simultaneously as the explained variables and the SRI dummy as the main explanatory variable. The SRI dummy takes the value of one for those SRI indices and zero otherwise. This dummy variable allows us to examine the sustainability or responsible effect on the index performance. The results are presented in Table 5 , which shows that the SRI dummy variable has a positive and statistically significant coefficient during the pandemic period. Furthermore, the magnitude of this coefficient is found to increase during the pandemic. The results, therefore, confirm the presence of the sustainability factor effect in improving the performance of the indices. This is found to be even greater during the COVID-19 period.11

Table 5.

Panel regression on the performance of MSCI SRI Indices against conventional MSCI Indices.

| US | Japan | Europe | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | During | Before | During | Before | During | |

| Con. | -0.0204⁎⁎⁎ | -0.155⁎⁎⁎ | -0.00725* | -0.16⁎⁎⁎ | -0.0129 | -0.15* |

| Mkt. Return | 2.298⁎⁎⁎ | 2.336⁎⁎⁎ | 2.097⁎⁎⁎ | 2.081⁎⁎⁎ | 2.212⁎⁎⁎ | 2.371⁎⁎⁎ |

| SMB | -0.211⁎⁎⁎ | -0.119⁎⁎⁎ | -0.352⁎⁎⁎ | -0.33⁎⁎⁎ | -0.485⁎⁎⁎ | -0.26⁎⁎⁎ |

| HML | -0.0628 | -0.0918 | -0.041 | -0.157 | -0.321⁎⁎ | -0.738 |

| RMW | -0.0297 | -0.273 | -0.0832 | -0.0844 | -0.206⁎⁎ | -0.0493 |

| CMA | 0.225 | 0.292 | -0.283⁎⁎⁎ | -0.442 | 0.323⁎⁎⁎ | 0.778⁎⁎⁎ |

| SRI_Dummy | 0.0334⁎⁎⁎ | 0.0892⁎⁎⁎ | 0.0306⁎⁎⁎ | 0.152⁎⁎⁎ | 0.0482⁎⁎⁎ | 0.198⁎⁎⁎ |

Notes: The table presents the results of panel regression analysis using the random-effect model (Eq. (4)). The explained variables used in the analyses include the MSCI and the MSCI SRI Indices. The data up to May 2020 are used for the US, and up to April 2020 for Europe and Japan. The first row indicates which country's or region's MSCI Indices are used in the analysis. SRI_Dummy is the MSCI SRI Index dummy that takes the value of one if the explained variable is the MSCI SRI Index and zero otherwise. ‘Before’ indicates the period prior to the COVID-19 pandemic used in the analysis and ‘During’ indicates the period during the pandemic. Other variables used in the analyses are the five factors introduced by Fama and French (2015); Mkt. Return is the market return, SMB is the size factor, HML is the value factor, RMW is the profitability factor, and CMA is the investment factor. We also conduct analysis on the ETFs using the Fama–French factors for the US. The result is not presented here, because it is consistent with that in previous tables. ***, **, and * indicate the coefficient is significant at the 10, 5, and 1% levels, respectively.

To check further the robustness of our findings, we reconduct all analyses using different starting dates that delineated the COVID-19 pandemic. For these dates, we use those for when the number of global confirmed cases reached 20,000, 30,000, 40,000, and 50,000. In summary, our findings remain unchanged, regardless of the dates used.

4. Conclusion

Responsible investing has become a popular investment practice. The theoretical explanations provided in the relevant literature claim that ESG activities of companies help them to build strong equity and a loyalty brand that lead to higher resilience against economic downturn. The literature also observes that the ESG effect arises from the ability of responsible companies to attract loyal shareholders who support the share price during downturns. Our finding supports the hypothesized outcome of the ESG effect, that is, SRI/ESG investments outperform conventional investments during the downturn. In this study, we analyzed the financial performance of SRI indices and ESG funds by comparing them against the market before and during the COVID-19 period while controlling for well-known risk factors. Our analyses confirmed that the outperformance of SRI indices increased during the pandemic period, both globally and across regions. ESG ETFs, however, did not outperform benchmarks, and we proposed several possible reasons for this.

The present study contributes to the literature on sustainable finance and our results will be useful to practitioners and policy makers. In particular, our findings indicate that investors can protect their wealth during the downturn through selecting responsible companies, especially in Europe. As our analyses employed the MSCI indices covering companies that collectively represent a substantial portion of the overall market capitalization, the results would be generalizable for the overall stock markets of the countries and regions analyzed in this study. However, our analyses are limited to the equity markets and are therefore not generalizable for other asset classes such as fixed income. This is an issue that can be investigated in future studies, as well as how the dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic impact the financial markets.12

The followings are the contributions of the authors:

Akihiro Omura: Conceptualization; Software; Data curation, Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing – Original; Writing – Review & Editing

Eduardo Roca: Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – Review & Editing

Miwa Nakai: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Visualization; Writing – Review & Editing

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: The ETF data required sorting and cleaning, and we would like to thank fellow academics and the industry professionals who provided valuable suggestions, especially Dr John Hua Fan, Dr Alexandr Akimov, and Mr. Kenichi Kanegae. This research was partially funded by the competitive research funding schemes of Fukui Prefectural University and Griffith University.

Estimated as “Total Cases – Total Deaths – Total Recovered” following Johns Hopkins University.

The degree of responsibility of a company is often measured by its activities from the perspective of ESG factors. An investment style that focuses on such aspects is often referred to as an SRI or ESG investment.

There is heterogeneity in the terms used to describe responsible investments. These terms include ‘socially responsible’ investment/investing, ‘ethical’ investment/investing, or ‘values-based’ investment/investing. However, Sandberg et al. (2009) and Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2013) suggest that, although there are differences in the terms, conceptually, these investments styles are comparable.

For a discussion of other potential reasons why responsible investments perform better than conventional investments, see, e.g., Heal (2005).

These ETFs also include funds exposed to the global market as the number of ETFs invested in the non-US markets.

We select the MSCI Indices following previous studies including Erragragui and Lagoarde-Segot (2016) and select these countries and regions as they comprise some of the largest stock markets and the largest number of responsible investors (considering the number of UN Principles for Responsible Investment signatories). We acknowledge that there are new MSCI Indices (i.e., MSCI ESG Indices) but because the data period is short, our analysis focuses on the SRI indices.

The papers include Goldreyer and Diltz (1999); Cummings (2000); Bauer et al. (2005); Jones et al. (2008); Renneboog et al. (2008); Cortez et al. (2009); Humphrey and Lee (2011); Basso and Funari (2014); Halbritter and Dorfleitner (2015); and Revelli and Viviani (2015).

https://guides.wsj.com/personal-finance/investing/how-to-choose-an-exchange-traded-fund-etf/#:~:text=The%20average%20ETF%20carries%20an,according%20to%20Morningstar%20Investment%20Research

The conclusions remain unchanged even if we rerun the analysis without the market factor.

The analysis is also conducted on the ETF funds. However, as with other analyses, the result is insignificant. For conciseness, we do not present these results here.

We would like to thank the reviewer for his/her valuable comments.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.frl.2020.101914.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Aegon Asset Management, 2020. Why ESG matters in a crisis. Available online: https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b1ly879667bxnt/why-esg-matters-in-a-crisis.

- Albuquerque R., Koskinen Y., Yang S., Zhang C. Resiliency of environmental and social stocks: An analysis of the exogenous Covid-19 market crash. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies. 2020;9:593–621. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque R., Koskinen Y., Zhang C. Corporate social responsibility and firm risk: Theory and empirical evidence. Management Science. 2019;65:4451–4469. [Google Scholar]

- Arefeen S., Shimada K. Performance and resilience of socially responsible investing (SRI) and conventional funds during different shocks in 2016: Evidence from Japan. Sustainability. 2020;12:540. [Google Scholar]

- Auer B.R. Do socially responsible investment policies add or destroy European stock portfolio value? Journal of Business Ethics. 2016;135:381–397. [Google Scholar]

- Basso A., Funari S. Constant and variable returns to scale DEA models for socially responsible investment funds. European Journal of Operational Research. 2014;235:775–783. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R., Koedijk K., Otten R. International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. Journal of Banking & Finance. 2005;29:1751–1767. [Google Scholar]

- Becchetti L., Ciciretti R., Dalò A., Herzel S. Socially responsible and conventional investment funds: Performance comparison and the global financial crisis. Applied Economics. 2015;47:2541–2562. [Google Scholar]

- Benson K.L., Humphrey J.E. Socially responsible investment funds: Investor reaction to current and past returns. Journal of Banking & Finance. 2008;32:1850–1859. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen N.P. Mutual fund attributes and investor behavior. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. 2007;42:683–708. [Google Scholar]

- Broadstock D.C., Chan K., Cheng L.T.W., Wang X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from Covid-19 in China. Finance Research Letters. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepoi C.-O. Asymmetric dependence between stock market returns and news during Covid19 financial turmoil. Finance Research Letters. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappini H., Vento G.A. Socially responsible investments and their anticyclical attitude during financial turmoil evidence from the Brexit shock. Journal of Applied Finance & Banking. 2018;8:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez M.C., Silva F., Areal N. The performance of European socially responsible funds. Journal of Business Ethics. 2009;87:573–588. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings L.S. The financial performance of ethical investment trusts: An Australian perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. 2000;25:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Derwall J., Koedijk K., Ter Horst J. A tale of values-driven and profit–seeking social investors. Journal of Banking & Finance. 2011;35:2137–2147. [Google Scholar]

- Erragragui E., Lagoarde-Segot T. Solving the SRI puzzle? A note on the mainstreaming of ethical investment. Finance Research Letters. 2016;18:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fama E.F., French K.R. A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics. 2015;116:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Flammer C. Does corporate social responsibility lead to superior financial performance? A regression discontinuity approach. Management Science. 2015;61:2549–2568. [Google Scholar]

- Folger-Laronde Z., Pashang S., Feor L., ElAlfy A. ESG ratings and financial performance of exchange–traded funds during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. 2020:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Friede G., Busch T., Bassen A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance Investment. 2015;5:210–233. [Google Scholar]

- Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2013. 2012 global sustainable investment review. Available online: http://gsiareview2012.gsi-alliance.org/pubData/source/Global%20Sustainable%20Investement%20Alliance.pdf.

- Goldreyer E.F., Diltz J.D. The performance of socially responsible mutual funds: Incorporating sociopolitical information in portfolio selection. Managerial Finance. 1999;25(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Halbritter G., Dorfleitner G. The wages of social responsibility—Where are they? A critical review of ESG investing. Review of Financial Economics. 2015;26:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Heal G. Corporate social responsibility: An economic and financial framework. The Geneva papers on risk and insurance–Issues and practice. 2005;30:387–409. [Google Scholar]

- Heyden, K.J., Heyden, T., 2020. Market reactions to the arrival and containment of Covid-19: An event study. Available at SSRN 3587497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Humphrey J.E., Lee D.D. Australian socially responsible funds: Performance, risk and screening intensity. Journal of Business Ethics. 2011;102:519–535. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J.P. J.P. Morgan; 2020. Why Covid-19 could prove to be a major turning point for ESG investing. [Google Scholar]

- Jones S., Van der Laan S., Frost G., Loftus J. The investment performance of socially responsible investment funds in Australia. Journal of Business Ethics. 2008;80:181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kempf A., Osthoff P. The effect of socially responsible investing on portfolio performance. European Financial Management. 2007;13:908–922. [Google Scholar]

- Lean H.H., Pizzutilo F. Performances and risk of socially responsible investments across regions during crisis. International Journal of Finance & Economics. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Leite P., Cortez M.C. Performance of European socially responsible funds during market crises: Evidence from France. International Review of Financial Analysis. 2015;40:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Morales L., Soler-Domínguez A., Hanly J. The power of ethical investment in the context of political uncertainty. Journal of Applied Economics. 2019;22:554–580. [Google Scholar]

- Nakai M., Yamaguchi K., Takeuchi K. Can SRI funds better resist global financial crisis? Evidence from Japan. International Review of Financial Analysis. 2016;48:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nofsinger J., Varma A. Socially responsible funds and market crises. Journal of Banking & Finance. 2014;48:180–193. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.L., Amin A., Al Mamun M.A. The Covid–19 outbreak and stock market reactions: Evidence from Australia. Finance Research Letters. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renneboog L., Ter Horst J., Zhang C. Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. Journal of banking & finance. 2008;32:1723–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Revelli C., Viviani J.L. Financial performance of socially responsible investing (SRI): What have we learned? A meta-analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review. 2015;24:158–185. [Google Scholar]

- Risalvato G., Venezia C., Maggio F. Social responsible investments and performance. International Journal of Financial Research. 2019;10:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai Y., Kurosaki T. How has the relationship between oil and the US stock market changed after the Covid-19 crisis? Finance Research Letters. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg J., Juravle C., Hedesström T.M., Hamilton I. The heterogeneity of socially responsible investment. Journal of Business Ethics. 2009;87:519. [Google Scholar]

- Scalet S., Kelly T.F. CSR rating agencies: What is their global impact? Journal of Business Ethics. 2010;94:69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad K., Xiaoxing L., Kazouz H. Covid-19’s disasters are perilous than global financial crisis: A rumor or fact? Finance Research Letters. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherif M. The impact of coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak on faith-based investments: An original analysis. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiq S., Javed S. Impact of CSR on organizational performance. European Journal of Business and Management. 2014;6:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. Covid-19 and safer investment bets. Finance Research Letters. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi V., Bhandari V. Performance of socially responsible stocks portfolios–the impact of global financial crisis. Journal of Economics and Business Research. 2016 ISSN2068-3537 22. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Lodorfos G., Dean A., Gioulmpaxiotis G. The market performance of socially responsible investment during periods of the economic cycle–Illustrated using the case of FTSE. Managerial and Decision Economics. 2017;38:238–251. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.