Abstract

Depression is one of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders and the leading cause of disability among adolescents, with sleep duration as its vital influential factor. Adolescents might be mentally sensitive to the stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, the alteration of adolescents' sleep duration, depression, and their associations within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic have not been well documented. We conducted a longitudinal study, recruiting 2496 adolescents from 3 junior high schools to examine the alteration of their sleep duration and depressive symptoms before and during the pandemic, and to explore their potential association(s). Data were collected before (December 2019) and during the pandemic (July 2020). Paired samples t-test revealed a significant decrease in sleep duration and a significant increase in depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Higher grades, COVID-19 infection history, higher CES-DC score, and the COVID-19 pandemic itself might contribute to decreased sleep duration, while longer exercise duration during the pandemic might be a protective factor. According to the cross-lagged analysis, the existence of depressive symptoms before the pandemic was significantly associated with a shorter sleep duration during the pandemic (β = −0.106, p < 0.001). Previously shortened sleep duration was significantly associated with a greater likelihood of depressive symptoms during the pandemic (β = −0.082, p < 0.001). Our findings revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic has a negative influence on adolescents’ mental health and sleep. Mental preparedness should be highlighted to mitigate the psychosocial influences of any possible public emergencies in the future. Sleep duration represents a viable home-based intervention for depressive symptoms.

Keywords: Depression, Sleep, Teenagers, Longitudinal associations, Repeated measures

1. Introduction

Depression is a common mental health disorder [1], affecting an estimated 300 million people worldwide [2]. Its main symptoms include lack of interest, insomnia, inability to enjoy life, and suicidal thoughts [3]. Depression is associated with a series of somatic consequences, including Alzheimer's disease [4], hypertension [5], stroke [6], obesity [7], cancer [8], and increased overall mortality [9]. Depression is recognized as the leading cause of disability worldwide and a major contributor to the global burden of disease by the World Health Organization. Adolescence is a critical transitional developmental period to adulthood [10], and hormonal fluctuation, physical development, and social adaptation stress could all contribute to the high incidence of depression in adolescents [11]. Adolescent depression is associated with a myriad of adult psychological outcomes, such as lower educational level, early pregnancy, unemployment [12], and higher risk of depression and suicidality in adulthood [13].

Sleep duration is a vital and modifiable influential factor of depression [14]. According to the National Sleep Foundation, teenagers are encouraged to sleep 8–10 h per day [15]. It was reported that shorter sleep duration is directly related with depressive symptoms among adolescents [16]. Sleep duration of fewer than 8 h on weekdays and more than 9 h on weekends were both reported to be significantly associated with depressive symptoms compared with 8 h [17]. Moreover, a longitudinal study revealed bilateral relations between sleep duration and depression among 10,704 community-dwelling adults [18]. Participants who slept less than 6 h per day had a higher risk of depression onset, while participants with depression were more likely to have shorter sleep duration [18]. However, the interconnectedness between sleep duration and depression among adolescents is not well documented.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is a contagious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been declared a pandemic in March 2020 by the World Health Organization. Ever since the Second World War and the 1918 influenza pandemic, the world has not faced such unprecedented unrest like the COVID-19 pandemic due to its contagion, lack of community immunization, and uncertainty. Adolescents could be mentally sensitive to sustained stressors such as the COVID-19 pandemic [19]. A previous meta-analysis revealed that trauma exposure was significantly associated with higher odds of depression among adolescents [20]. Several recent studies focused on the prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [21,22]; however, longitudinal studies were rare. The current study adopted a longitudinal design aimed at examining the alteration of sleep duration and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents under the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and exploring their bilateral associations.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and subjects

We carried out a longitudinal study, exploring the change of sleep duration and depressive symptoms among adolescents, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, in Sichuan Province, China, and examining the bilateral relationships between them.A total of 3080 students from 3 junior high schools in Sichuan Province were recruited through cluster randomization in the Chengdu Survey of Positive Child Development. 2496 participants completed the whole study, amounting to a response rate of 81.0%. Data were collected in two waves: Wave 1 was carried out in December 2019 (before the pandemic), and Wave 2 was conducted in July 2020 (during the pandemic). Participants completed the questionnaire independently and returned it to the researcher immediately; the average data collection session for each participant was about 10 min.

2.2. Ethical consideration

Our study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Sichuan University, with the registration number K2020025. All participants volunteered for the study with their written informed consent, and confidentiality was strictly assured. Participants were aware of their rights to withdraw at any point of the study.

2.3. Measurement tools

2.3.1. Depressive symptoms

The Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) was used to assess depressive symptoms [23]. It is a 20-item self-reporting tool for depression-related symptoms experienced in the past week, scoring each item on a four-point Likert scale of 0–3, with 0 indicating ‘not at all’ and 3 indicating ‘a lot’. The maximum score of CES-DC is 60, with a higher score indicating greater depressive symptoms. Satisfactory reliability and validity of CES-DC have been demonstrated in the Chinese population with the test and retest alpha coefficient of 0.82 and 0.85, respectively [24].

2.3.2. Sleep duration

Sleep duration was measured using two items, the first one asked participants the average hours they slept per night in the past week, and the other asked about the additional average minutes. The total sleep duration was converted into minutes while analyzing.

2.3.3. Demographics and COVID-19 infection history

Demographic information includes eight items: age (years), grade (7, 8, and 9), gender (boy and girl), nationality (The Hans and Minorities), dwelling (urban and suburban), only child (yes and no), exercise duration during the pandemic, and COVID-19 infection history (Did you or your family members get infected by COVID-19?).

2.4. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 26.0, and Mplus software, version 7.3. Descriptive statistics, including mean with standard deviation (SD) and proportion with percentages in parentheses, were used to summarize the characteristics of the participants, sleep duration, and the CES-DC scores. Paired samples t-test (using SPSS software, version 26.0) was adopted to compare sleep duration and CES-DC score before and during the pandemic. Generalized Estimating Equations model (GEE, using SPSS software, version 26.0) was used to identify variables that contributed to the alteration of sleep duration. A cross-lagged analysis (using Mplus software, version 7.3) was used to explore the bilateral relations between sleep duration and depressive symptoms. All statistical tests used were two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Among 2496 participating students included in the final analysis, 1085 (43.5%) were in Grade 7, 1057 (42.3%) in Grade 8, and 354 (14.2%) in Grade 9. The average age of the participants was 13.4 (0.9) (ranging from 11 to 16), and the average daily exercise duration during the pandemic was 1.2 (0.8) hours. Nearly three-fifths of the participants (59.9%) were from the urban area, 1698 students (68.0%) were from only-child families. More than half of them were girls (50.2%), only 20 (0.8%) were Minorities, and 69 (2.8%) reported COVID-19 infection history.

3.2. The alteration of sleep duration and depressive symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Paired samples t-test was used to compare the adolescents’ sleep duration and depressive symptoms before (Wave 1) and during (Wave 2) the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a significant decrease in sleep duration from 516.7 (71.4) minutes before to 497.0 (79.0) during the pandemic (p < 0.001). A significant increase in depressive symptoms from 15.1 (10.5) before to 15.9 (11.1) during the pandemic (p < 0.001) was detected as well. Table 1 summarized the alteration of sleep duration and depressive symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1.

The alteration of sleep duration and depressive symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (N = 2496).

| Variables | Wave 1 |

Wave 2 |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Sleep duration | 516.7 | 71.4 | 497.0 | 79.0 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 15.1 | 10.5 | 15.9 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

Note: SD = Standard Deviation.

3.3. Variables associated with the alteration of sleep duration based on Generalized Estimating Equations

Concretely speaking, 1063 participants (42.6%) experienced decreased sleep duration, 918 of them (36.8%) maintained their sleep duration, while only 515 (20.6%) experienced increased sleep duration. We adopted GEE model, with exchangeable working correlation matrix, linear regression, and main effect model, to explore the variables that might have contributed to the alteration of sleep duration. Participants’ demographics, COVID-19 infection history, time point, exercise duration, and CES-DC score were entered into the GEE model as factors (ordinal data) and covariates (numerical data), respectively; sleep duration was entered as the dependent variable. According to the results of the GEE model, higher grades (Grade 9: β = −0.333, P = 0.001; Grade 8: β = −0.212, P = 0.001), COVID-19 infection history (β = −2.480, P < 0.001), higher CES-DC score (β = −0.006, P = 0.001), and time point Wave 2 (β = −0.323, P < 0.001) were risk variables which might contribute to decreased sleep duration. Longer exercise duration during the pandemic (β = 0.067, P = 0.022) was the potential protective factor of sleep duration (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Variables associated with the alteration of sleep duration based on Generalized Estimating Equations (N = 2496).

| Variables | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender = girl | −0.021 | 0.039 | 0.294 | 0.588 | 0.979 |

| Infection history = yes | −2.480 | 0.132 | 353.917 | <0.001 | 0.084 |

| Nationality = Minority | 0.212 | 0.219 | 0.943 | 0.331 | 1.236 |

| Dwelling = suburban | 0.052 | 0.040 | 1.678 | 0.195 | 1.054 |

| Only child = yes | 0.023 | 0.043 | 0.289 | 0.591 | 1.024 |

| Time point = Wave 2 | −0.323 | 0.027 | 146.133 | <0.001 | 0.724 |

| Grade | |||||

| 9 | −0.333 | 0.100 | 11.204 | 0.001 | 0.717 |

| 8 | −0.212 | 0.061 | 12.008 | 0.001 | 0.809 |

| 7 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Age | 0.043 | 0.036 | 1.479 | 0.224 | 1.044 |

| CES-DC score | −0.006 | 0.002 | 10.533 | 0.001 | 0.994 |

| Exercise duration | 0.067 | 0.029 | 5.250 | 0.022 | 1.069 |

3.4. Longitudinal, bilateral relations between sleep duration and depressive symptoms

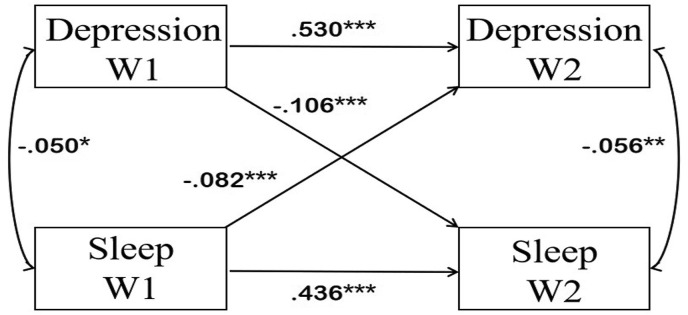

The existence of depressive symptoms at Wave 1 was significantly associated with shorter sleep duration at Wave 2 (β = −0.106, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1 ). Shorter sleep duration at Wave 1 was also significantly associated with a greater likelihood of depressive symptoms at Wave 2 (β = −0.082, p < 0.001). Depressed adolescents were prone to have shorter sleep duration during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, adolescents who used to have shorter sleep duration were more likely to report depressive symptoms during the pandemic. The cross-lagged model also presented other structural paths. Previous depressive symptoms were likely to increase during the COVID-19 pandemic (β = 0.530, p < 0.001). Previous sleep duration was positively related to sleep duration during the COVID-19 pandemic (β = 0.436, p < 0.001). Depressive symptoms were negatively associated with sleep duration both before and during the pandemic, with correlation coefficients of −0.50 (p < 0.05) and −0.056 (p < 0.01), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Cross-lagged model between sleep duration and depressive symptoms. Note: The two-way arrow in the chart indicates the result of correlation analysis, with the data of correlation coefficient; the one-way arrow indicates the result of path analysis, with the data of standardized regression coefficient (β). ∗∗∗: P < 0.001, ∗∗: P < 0.01, ∗: P < 0.05. Depression W1: depressive symptoms before the COVID-19 pandemic; Depression W2: depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic; Sleep W1: sleep duration before the COVID-19 pandemic; Sleep W2: sleep duration during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Discussion

The current study found a significant increase in depressive symptoms and a decrease in sleep duration under the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which enriched the extant knowledge pertaining to the alteration of adolescents' mental health and sleep associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study confirmed the bilateral relations between adolescents’ sleep duration and depressive symptoms for the first time, under the extreme context of the COVID-19 crisis.

The increase in the presentation of depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic is in line with previous longitudinal studies [25,26]. For example, the increase of depressive symptoms was reported among 248 out of 467 Australian adolescents who had completed the survey before and during the COVID-19 pandemic [25]. Another study reported an increase in depressive symptoms among 24 American adolescents experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic as well [26]. Besides the immediate medical consequence of infection, the strict social confinement measures to contain COVID-19 might contribute to depressive symptoms as well [27]. On one hand, adolescents might lose the rhythm, meaning, and structure of their daily lives during confinement and school closure due to the lack of peer interaction and physical activities [28]. On the other hand, because of the online learning request and the unique culture, Chinese adolescents were more likely to be monitored and supervised by their parents in a 24/7 manner; this resulted not only in parent-teen challenges and negotiations but also the experience of lost autonomy [29,30].

The decrease in adolescents' sleep duration during the COVID-19 pandemic contradicted previous findings of other studies [31,32]. For example, an increase of sleep duration from 9.1 h before to 9.3 h during the COVID-19 pandemic was found among 611 Spanish adolescents and children who were under strict confinement [31]. Similarly, an increase of sleep duration from 9.11 h before to 9.51 h during the pandemic was found among 1480 children and adolescents from three European countries [32]. Moreover, participants in a qualitative study reported better and longer sleep following the pandemic [33]. Though there was one study that found no significant change in adolescents’ sleep duration during the confinement [34], its small sample size of only 9 adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder had limited its representativeness. Our finding has added different information to the extant literature, indirectly supported by a previous study that reported 18.0% of junior high adolescents had insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic [35]. The reason underlying the decrease in sleep duration might be the increased screen time [36], the worry related to the pandemic [37], and extra time spent on debugging equipment for online learning every day. Moreover, we had disclosed variables associated with decreased sleep duration via GEE model, including higher grades, COVID-19 infection history, higher CES-DC score, and the COVID-19 pandemic itself. Meanwhile, longer exercise duration during the pandemic might be a protective factor of sleep (Table 2), which may contribute to explaining the differences in findings.

According to our findings, adolescents who had depressive symptoms before the pandemic were prone to sleep less during the pandemic, whereas those who slept less before the pandemic were more likely to report depressive symptoms during it. These findings were similar to previous findings. For example, a recent meta-analysis including 50 studies found out shorter sleep duration was associated with more severe depressive symptoms among adolescents [38]. It was also reported that a sleep duration of fewer than 6 h was significantly associated with depressive symptoms in a sample of 4805 Chinese female adolescents [16]. A longitudinal study revealed the bilateral relations between sleep duration and depression among 10,704 community-dwelling adults [18]. Participants who slept fewer than 6 h per day had a higher risk of depression onset, and participants with depression were more likely to have shorter sleep duration [18]. Digging deeper, more clinically depressed adolescents were found to have a higher risk of experiencing rapid eye movement sleep fragmentation in a Finnish study [39]. Moreover, traumatic events such as the COVID-19 pandemic often lead to hyperarousal and hypervigilance, which might be the reasons underlying the relation between sleep duration and depressive symptoms [40].

Our findings are convincing, by its relatively larger sample size of 2,496, strict paired sampling, and longitudinal study design. The offline data collection guaranteed a satisfactory response rate as well. Our findings have practical implications to individual, family, school, and public policy levels by highlighting the mental health well-being of adolescents under social crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic and offering a potential viable home-based intervention.

5. Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. Firstly, in spite of the cluster randomization and multicenter sampling, the current study was carried out in Sichuan Province only, which may weaken its representativeness. Participants from other regions of China should be considered in further studies. Secondly, although the study achieved a satisfactory response rate by onsite data collection, reporting bias cannot be completely ruled out. Lastly, although a longitudinal study design was adopted, it may be difficult to draw clear causal associations from such an observational study. There may be some other confounding factors that could modify the associations we found or create ‘fake’ correlations. More confounding variables, such as season, weather, physical conditions, parents' education, economic status, and living arrangements, may need to be considered to strengthen the robustness of the longitudinal associations found in this study, which are also expected to be extended into the longer-term effects by continuous follow-ups [41].

6. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has a negative influence on adolescents' mental health and sleep. Mental preparedness should be highlighted to mitigate the psychosocial influences of any possible public emergencies in the future. There are longitudinal, bilateral associations between adolescents' depressive symptoms and sleep duration under the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep duration is an inherently modifiable influential factor for depressive symptoms. Its potential economic viability and ‘natural’ image make it an attractive targeted intervention for adolescents' well-being now and in the long run.

Funding

This work was supported by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (19H0642); Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province, China (2020JDKP0021).

CRediT author statement

Shujuan Liao: Writing - Original Draft, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Biru Luo: Writing - Original Draft.

Hanmin Liu: Writing - Review & Editing, Methodology.

Li Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Wei Shi: Writing - Review & Editing.

Yalin Lei: Data Curation, Investigation, Formal analysis.

Peng Jia: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision.

Acknowledgmends

We thank the International Institute of Spatial Lifecourse Epidemiology (ISLE) for research support.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest associated with this article can be viewed by clicking on the following link: .https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.06.007.

Conflict of interest

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Multimedia component 1

References

- 1.Liu Q., He H., Yang J., et al. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: findings from the global burden of disease study. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;126:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel V., Chisholm D., Parikh R., et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities. Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1672–1685. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui R. A systematic review of depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(4):480. doi: 10.2174/1570159X1304150831123535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Y., Huang C., Zhao K., et al. Retracted: depression as a risk factor for dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2013;28(5):441–449. doi: 10.1002/gps.3845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng L., Chen D., Yang Y., et al. Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30(5):842–851. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835080b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong J.-Y., Zhang Y.-H., Tong J., et al. Depression and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Stroke. 2012;43(1):32–37. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.630871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luppino F.S., van Reedt Dortland A.K., Wardenaar K.J., et al. Symptom dimensions of depression and anxiety and the metabolic syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(3):257–264. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820a59c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chida Y., Hamer M., Wardle J., et al. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5(8):466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuijpers P., Vogelzangs N., Twisk J., et al. Differential mortality rates in major and subthreshold depression: meta-analysis of studies that measured both. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(1):22–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crews F.T., Vetreno R.P., Broadwater M.A., et al. Adolescent alcohol exposure persistently impacts adult neurobiology and behavior. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(4):1074–1109. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.012138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thapar A., Collishaw S., Pine D.S., et al. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clayborne Z.M., Varin M., Colman I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson D., Dupuis G., Piche J., et al. Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: a systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(8):700–716. doi: 10.1002/da.22777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhai L., Zhang H., Zhang D. Sleep duration and depression among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(9):664–670. doi: 10.1002/da.22386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirshkowitz M., Whiton K., Albert S.M., et al. National Sleep Foundation's updated sleep duration recommendations. Sleep Health. 2015;1(4):233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J., Yuan X., Qi H., et al. Prevalence of depression and its correlative factors among female adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00601-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu B.-P., Wang X.-T., Liu Z.-Z., et al. Depressive symptoms are associated with short and long sleep duration: a longitudinal study of Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Y., Shi L., Bao Y., et al. The bidirectional relationship between sleep duration and depression in community-dwelling middle-aged and elderly individuals: evidence from a longitudinal study. Sleep Med. 2018;52:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo M., Zhang D., Shen P., et al. COVID-19 lockdown and social capital changes among youths in China. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2021 doi: 10.34172/IJHPM.2021.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vibhakar V., Allen L.R., Gee B., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression in children and adolescents after exposure to trauma. J Affect Disord. 2019;255:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou S.-J., Zhang L.-G., Wang L.-L., et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2020;29:749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guessoum S.B., Lachal J., Radjack R., et al. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatr Res. 2020;113264 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff L.S. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.William Li H.C., Chung O.K.J., Ho K.Y. Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale for children: psychometric testing of the Chinese version. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(11):2582–2591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magson N.R., Freeman J.Y., Rapee R.M., et al. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen Z., Cosgrove K.T., DeVille D., et al. The impact of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health: preliminary findings from a longitudinal sample of healthy and at-risk adolescents. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Courtney D., Watson P., Battaglia M., et al. COVID-19 impacts on child and youth anxiety and depression: challenges and opportunities. Can J Psychiatr. 2020;65(10):688–691. doi: 10.1177/0706743720935646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker S.P., Gregory A.M. Editorial Perspective: perils and promise for child and adolescent sleep and associated psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bülow A., Keijsers L., Boele S., et al. Parenting adolescents in times of a pandemic: changes in relationship quality, autonomy support, and parental control? 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.López-Bueno R., López-Sánchez G.F., Casajús J.A., et al. Health-related behaviors among school-aged children and adolescents during the Spanish Covid-19 confinement. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:573. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Francisco R., Pedro M., Delvecchio E., et al. Psychological symptoms and behavioral changes in children and adolescents during the early phase of COVID-19 quarantine in three European countries. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:1329. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.570164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gruber R., Saha S., Somerville G., et al. The impact of COVID-19 related school shutdown on sleep in adolescents: a natural experiment. Sleep Med. 2020;76:33–35. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia J.M., Lawrence S., Brazendale K., et al. Brief Report: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health behaviors in adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Disabil Health J. 2020:101021. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou S.-J., Wang L.-L., Yang R., et al. Sleep problems among Chinese adolescents and young adults during the coronavirus-2019 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020;74:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiang M., Zhang Z., Kuwahara K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents' lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(4):531–532. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kılınçel Ş., Kılınçel O., Muratdağı G., et al. Factors affecting the anxiety levels of adolescents in home-quarantine during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Asia Pac Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.1111/appy.12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Short M.A., Booth S.A., Omar O., et al. The relationship between sleep duration and mood in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;101311 doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pesonen A.-K., Gradisar M., Kuula L., et al. REM sleep fragmentation associated with depressive symptoms and genetic risk for depression in a community-based sample of adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baiden P., Fallon B., den Dunnen W., et al. The enduring effects of early-childhood adversities and troubled sleep among Canadian adults: a population-based study. Sleep Med. 2015;16(6):760–767. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia P. Spatial lifecourse epidemiology. Lancet Planet Health. 2019;3(2):e57–e59. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multimedia component 1