Abstract

Objectives

Prior to COVID-19, levels of adoption of telehealth were low in the U.S., though they exploded during the pandemic. Following the pandemic, it will be critical to identify the characteristics that were associated with adoption of telehealth prior to the pandemic as key drivers of adoption and outside of a public health emergency.

Materials and methods

We examined three data sources: The American Telemedicine Association’s 2019 state telehealth analysis, the American Hospital Association’s 2018 annual survey of acute care hospitals and its Information Technology Supplement. Telehealth adoption was measured through five telehealth categories. Independent variables included seven hospital characteristics and five reimbursement policies. After bivariate comparisons, we developed a multivariable model using logistic regression to assess characteristics associated with telehealth adoption.

Results

Among 2923 US hospitals, 73% had at least one telehealth capability. More than half of these hospitals invested in telehealth consultation services and stroke care.

Non-profit hospitals, affiliated hospitals, major teaching hospitals, and hospitals located in micropolitan areas (those with 10-50,000 people) were more likely to adopt telehealth.

In contrast, hospitals that lacked electronic clinical documentation, were unaffiliated with a hospital system, or were investor-owned had lower odds of adopting telehealth. None of the statewide policies were associated with adoption of telehealth.

Conclusions

Telehealth policy requires major revisions soon, and we suggest that these policies should be national rather than at the state level. Further steps as incentivizing rural hospitals for adopting interoperable systems and expanding RPM billing opportunities will help drive adoption, and promote equity.

Keywords: Health policy, Medical informatics, Quality of healthcare, Healthcare costs, Government regulation

1. Introduction

Telehealth is a health care delivery modality that distributes health-related services and clinical information through telecommunication technologies [1]. It has numerous applications, including consultations and office visits [2], [3], eICU [4], stroke care [5], psychiatric and addiction treatment [6] and other telehealth services [7], [8], [9]. Telehealth applications have been found to be beneficial for clinicians and patients, including alleviating hospital congestion, improving cost-effectiveness [10], supporting patients’ management of chronic illnesses [7], and helping rural hospitals provide specialty care [11].

Prior to the pandemic, telehealth services were used by various clinicians and systems [12], [13], [14], yet adoption levels remained low: estimates from 2016 showed that 61% of US healthcare institutions and 40% to 50% of US hospitals adopted telehealth in some capacity, and even among hospitals that had adopted levels of use appear modest [8], [9], [15], [16], [17].

In addition, telehealth adoption varied extensively across U.S states due to the variability in legislation and reimbursement policies for telehealth services. In addition, some states lacked the resources needed to fully deploy telehealth across the state [18].

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) entirely disrupted the provision of care, catapulting telehealth to the forefront, and in many places substituting it for care traditionally provided in-person [19], [20], [21]. Indeed, studies showed a 154% increase in telehealth visits during the last week of March 2020, compared with the same period in 2019 due to expanded reimbursement policies [22], [23].

How things will proceed in the post-pandemic world remains uncertain with respect to telehealth use [23]. However, it is likely that many of the prior levers promoting and curtailing its use will again be salient once the public health emergency ends [24]. We therefore sought to identify the local hospital characteristics and regional policy features that before the pandemic were associated with adoption and may help drive successful implementation nationwide.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

We examined three data sources: The American Hospital Association’s (AHA) 2018 annual survey of acute care hospitals, its Information Technology Supplement and the American Telemedicine Association’s 2019 (ATA) state telehealth analysis.

The 2018 AHA Information Technology (IT) Supplement was sent to the chief information officers of every acute care hospital in the US to collect information about their electronic health records, interoperability, and transition to electronic systems for the period of 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2018 [25]. The 2019 American Telemedicine Association (ATA): State of the States report, analyzed telehealth coverage and reimbursement policies across all 50 states and the District of Colombia for the period between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2019 [18].

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Dependent variable

The national telehealth adoption rate for 2018 was calculated for each hospital in the sample using five telehealth adoption categories supplied by the AHA full survey: consultation and office visits, eICU, stroke care, psychiatric and addiction treatment, and other telehealth categories.

2.2.2. Independent variables

We used the IT supplement to explore how telehealth adoption in a hospital was associated with the following independent variables:

The presence of electronic clinical documentation systems,

Hospital size was based on the total number of beds

Ownership status was based on government, not for profit, or investor-owned

We used the 2019 ATA report synthesizes the complex policy landscape into a summary of each state’s telehealth policies. We created six independent variables of reimbursement policies based on each state’s summary.

Reimbursement for remote patient monitoring, refers to state policies that support the use of digital technologies to collect health information from patients in one location and transfer it to a healthcare provider in another location [18].

Reimbursement for store and forward technology, included support for sharing medical information like digital images, documents, and video through secure online communication [18]. Reimbursement for interactive communication between the patient and provider using audio and video [18].

Commercial parity was a policy that required commercial payers to pay the same price for telehealth care as for in-person visits.

Medicaid parity required Medicaid to reimburse for telehealth care to the same extent as in-person visits.

Location-based parity, required not only clinics and hospitals but also schools, homes, and any other patient location to be reimbursable.

2.3. Statistical analysis

We included all hospitals that participated in the 2018 survey, except those located in US territories because they are subject to different rules and regulations [26]. We present mean scores and 95% confidence intervals, as appropriate. We used Raking method and hospital level sampling weights to adjust the model for potential non-response bias [26], [27].

To identify predictors, we used a dual stage analysis. First, we examined bivariate associations between telehealth adoption and various hospital and policy characteristics using a chi-square test for categorical variables and student’s t-test for continuous variables (Table 1 ). Second, we selected variables from our bivariate analyses that were significantly associated with telehealth adoption (p < 0.05) for multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for all variables in Table 2 . All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 and considered a 2-sided p-value of <0.05 to be significant. The Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board determined this study not to be human subjects research.

Table 1.

US hospital characteristics, state-level telehealth policies, and bivariate associations.

| Hospital characteristic | All hospitals | Hospitals with telehealth | Hospitals without telehealth | p value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has electronic clinical documentation, N (%) | 2857 (97) | 2119 (99) | 738 (94) | <0.001 |

| Affiliated with a major hospital system, N (%) | 2031 (70) | 1586 (74) | 445 (57) | <0.001 |

| Hospital ownership, N (%) | ||||

| Government | 578 (20) | 370 (17) | 208 (26) | <0.001 |

| Nonprofit | 1889 (65) | 1566 (73) | 323 (41) | |

| Investor owned | 456 (15) | 206 (9) | 250 (32) | |

| No teaching | 1570 (54) | 1062 (49) | 508 (65) | <0.001 |

| Minor teaching | 1129 (39) | 875 (40) | 254 (32) | |

| Major teaching | 224 (7) | 205 (9) | 19 (2) | |

| Geography, N (%) | ||||

| Metro | 2006 (69) | 1477 (68) | 529 (67) | 0.019 |

| Micro | 425 (14) | 326 (15) | 99 (12) | |

| Rural | 492 (17) | 339 (15) | 153 (19) | |

| Percent of hospital patients covered by accountable care contracts, % (95% CI) | 3.85 (2.84,3.57) | 4.41 (3.674, 4.64) | 0.73 (0.34, 0.90) | <0.0001 |

| Total beds mean (95% CI) | 186.31 (178.07, 193.95) | 205.09 (195.67, 215.78) | 131.21 (120.4,142.71) | <0.001 |

| Legislated state telehealth policy characteristics N (%) | ||||

| Remote patient monitoring | 23 (45) | 908 (42) | 409 (52) | <0.0001 |

| Store and forward | 29 (57) | 1266 (59) | 597 (76) | 0.029 |

| Video coverage | 51 (98) | 2138 (99) | 779 (99) | 0.729 |

| Commercial parity | 36 (73) | 1451 (67) | 557 (71) | 0.046 |

| Medicaid parity | 32 (63) | 1350 (63) | 518 (66) | 0.092 |

| Location-based parity | 44 (86) | 1683 (78) | 663 (85) | <0.0001 |

chi-squared test for categorical variables; t-test for continuous variables.

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of hospital and state characteristics associated with telehealth adoption.

| Hospital characteristics | Adjusted odds of adopting telehealth (95 %CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Has electronic clinical documentation | ||

| Yes | – | – |

| No | 1.045 (1.024, 1.066) | 0.000 |

| Affiliated with a hospital system | ||

| Yes | – | – |

| No | 0.567 (0.475, 0.667) | <0.0001 |

| Hospital ownership | ||

| Government/federal | – | – |

| Nonprofit | 1.886 (1.551, 2.293) | <0.0001 |

| Investor | 0.538 (0.410, 0.706) | <0.0001 |

| Teaching status | ||

| No teaching | – | – |

| Minor teaching | 1.213 (0.959, 1.535) | 0.108 |

| Major teaching | 2.977 (1.699, 5.217) | 0.003 |

| Geographic rurality | ||

| Metropolitan | – | – |

| Micropolitan | 1.481 (1.159, 1.893) | 0.005 |

| Rural | 1.189 (0.960, 1.473) | 0.113 |

| Percent of hospital patients covered by accountable care contracts | 1.040 (1.023, 1.056) | <0.0001 |

| Total number of beds | 1.001 (1.000, 1.001) | 0.042 |

| Legislated telehealth policy characteristics | ||

| Remote patient monitoring | 1.051 (0.852, 1.297) | 0.640 |

| Commercial parity | 1.148 (0.869, 1.516) | 0.333 |

| Store and forward | 1.078 (0.826, 1.407) | 0.579 |

| Location-based parity | 0.881 (0.689, 1.127) | 0.314 |

CI is confidence interval.

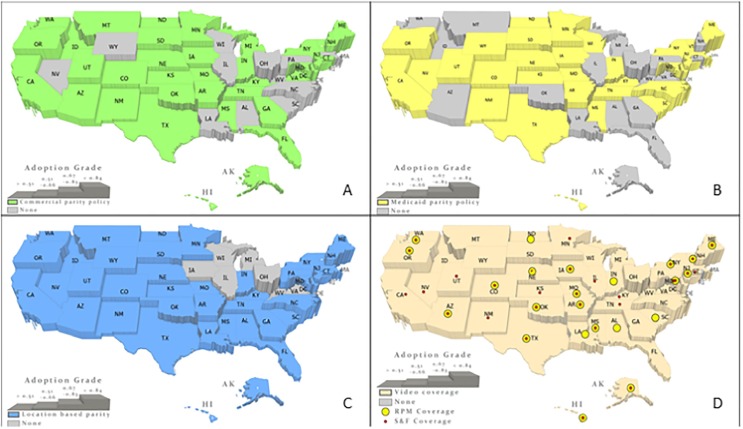

2.4. Spatial overlay assessment

To visualize the relationship between state policies and telehealth adoption across states in 2018, we used Geographic Information System mapping (ESRI ArcGIS PRO version 2.4).

2.5. Limitations

Our work has limitations. First, we measured telehealth adoption using five telehealth categories, potentially omitting certain variants of telehealth. Hence, our ability to asses all types of telehealth applications was limited. In addition, the level to which telehealth was used was not assessed, and even among hospitals which had adopted, this was likely quite variable. Second, although the 2018 AHA survey included 6218 U.S hospitals, the 2018 IT supplement included only 3518 hospitals, of which 2923 hospitals responded to AHA survey items about telehealth. Hence, the study sample included only 47% of US hospitals, limiting generalizability. However, we adjusted the sample for non-response, and it represents the largest hospital-based survey in the country. Third, although we measured a comprehensive set of variables, there are many factors that could have affect hospitals decision to invest in telehealth and we were not able to study all of them.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has altered the healthcare delivery landscape, although its lasting impact is uncertain, and things could move in several directions.

3. Results

3.1. Hospital characteristics

We analyzed 2923 hospitals (Table 1) that were adjusted with hospital-level sampling weights for potential nonresponse bias to represent a nationwide sample (See Appendix 1 for characteristics of hospitals who did not participate in the survey).

Hospitals had a mean bed size of 186 (95% CI, 178 to 194). Nearly all (97%) hospitals used electronic clinical documentation systems, 70% were affiliated with a major health system, 65% were non-profit, 69% were in a metropolitan area, and 54% were non-teaching.

3.2. Telehealth adoption

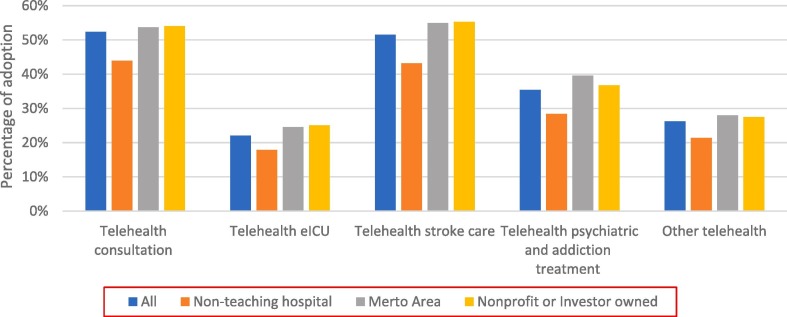

Most (73%; 2142 out of 2923) hospitals adopted at least one telehealth capability in 2018 (Fig. 1 ). Telehealth for patient consultation was adopted for 85% of major teaching hospitals, 49% of micro rural hospitals, and 54% of nonprofit hospitals used telehealth for patient consultation. eICU capabilities were present in 39% of major teaching hospitals, 23% of micro rural hospitals, and 25% of nonprofit hospitals. Telehealth for stroke care was adopted in 70% of major teaching hospitals, 53% of micro rural hospitals, and 56% of nonprofit hospitals. 62% of major teaching hospitals, 29% of micro rural hospitals, and 37% of nonprofit hospitals provided telehealth for psychiatric and addiction treatment.

Fig. 1.

Telehealth capabilities in US hospitals segmented by teaching status, ownership, and geography.

3.3. State level telehealth policies

State telehealth policies were variably adopted in 2018 (Table 1). Nearly all (98%) states provided reimbursement for interactive communication, 57% Store and Forward reimbursement, and 45% Remote Patient Monitoring. Most states legislated parity policies: 73% for commercial payors, 63% for Medicaid, and 86% for location.

3.4. Characteristics associated with telehealth adoption

In bivariate analyses, all hospital characteristics were significantly different between hospitals that had and had not adopted telehealth (Table 1). Larger hospitals (205 beds vs 131 beds, p < 0.001), those affiliated with a major health system (74% vs 57%, p < 0.001), those more heavily participating in an ACO (4.2% covered lives vs 0.6% covered lives, p < 0.0001), hospital ownership (for example, nonprofit hospitals [73% vs 41%, p < 0.001]), and teaching status (for example, major teaching [9% vs 2%, p < 0.001]). Legislative characteristics were only significantly different for Remote Patient Monitoring (42% vs 52%, p < 0.0001), Store and Forward (59% vs 76%, p = 0.004), and location-based parity (78% vs 85%, p < 0.0001).

In multivariable analyses (Table 2), we found that the adjusted odds of adopting telehealth increased for nonprofit hospitals (vs government hospitals, aOR 1.81 [95% CI, 1.44 to 2.28]), major teaching hospitals (vs nonteaching hospitals, aOR 2.39 [95% CI, 1.34 to 4.26]), micropolitan hospitals (vs metropolitan, aOR 1.50 [95% CI, 1.14 to 1.97]), hospitals covered by ACO (vs. hospitals who do not participate in an ACO, aOR 1.04 [95% CI, 1.02 to 1.05]) and larger hospitals (vs. smaller hospitals, aOR 1.01 [95% CI, 1.00 to 1.01]) . In contrast, hospitals had lower odds of adopting telehealth if they lacked electronic clinical documentation (aOR, 0.45 [95% CI, 0.26 to 0.81]), were unaffiliated with a hospital system (aOR, 0.49 [95% CI, 0.39 to 0.60]), or were investor-owned (aOR, 0.39 [95% CI, 0.29 to 0.52]). None of the statewide policies were associated with adoption of telehealth.

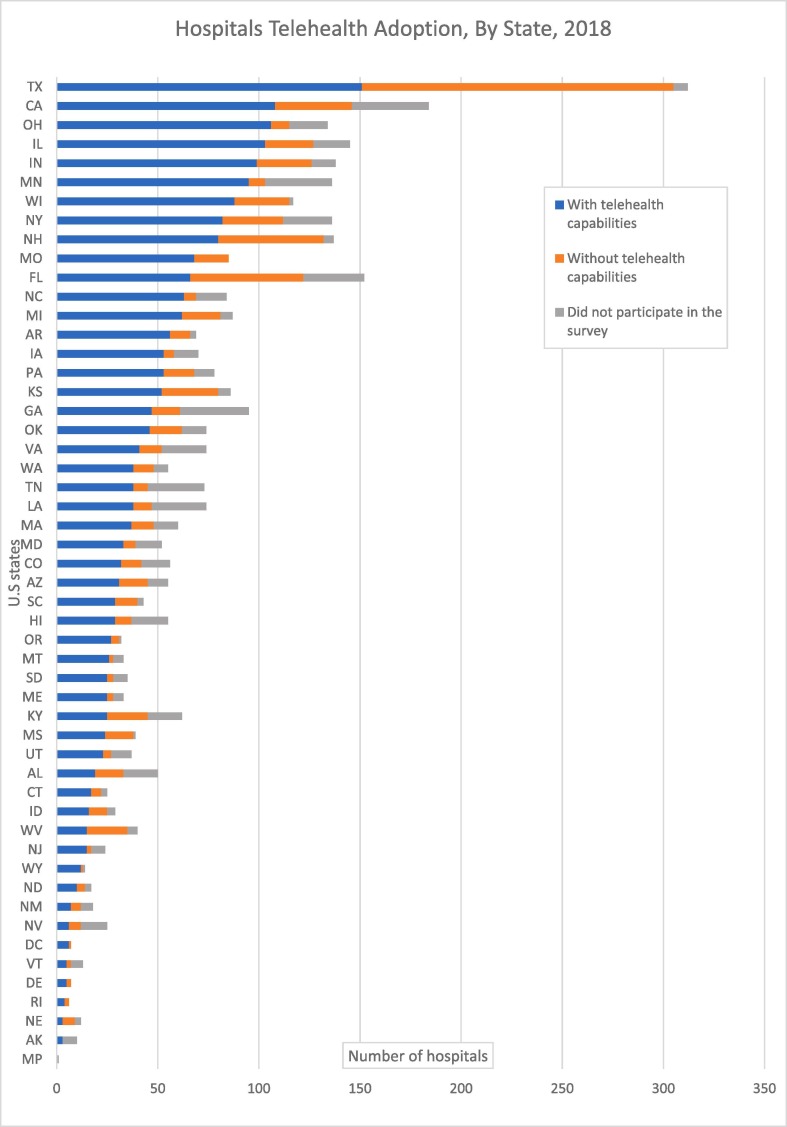

3.5. Geographic variation

We found greater adoption of telehealth on the east and west coasts of the country (Fig. 2 ). Hospitals located in east and west coast states had high participation levels in the AHA survey and broader adoption of telehealth capabilities (Fig. 3 ). Remote Patient Monitoring, Store and Forward, and video coverage policies were legislated in most of New England and in the central states. Nevertheless, the central states hospitals which had high participation levels in the AHA survey (Fig. 3) also had lower levels of adoption than New England states (Fig. 2A). Location based parity policies were legislated in most of the country except in the east north central states. Hospitals in the neighboring west north central states which legislated these policies and had high participation levels in the survey (Fig. 3) had lower levels of telehealth adoption (Fig. 2B). Varied adoption levels were found in a group of neighboring states within the Northeast, Midwest and South which did not legislate commercial parity policies (Fig. 2C). Likewise, groups of neighboring states within the West, South and Middle Atlantic and East North Central which did not legislate Medicare parity policies demonstrated varied levels of adoption (2D).

Fig. 2.

Telehealth adoption in U.S hospitals by legislated telehealth policies and geographic variations (Clockwise: Commercial parity policy, Medicaid parity policy, Video, RPM and S&F coverage and Location based parity).

Fig. 3.

Telehealth adoption in U.S hospitals by states and participation in the AHA survey.

4. Discussion

In a nationally-representative analysis of US hospitals, we found that statewide telehealth policies were not associated with telehealth adoption but hospitals that were nonprofit, major teaching, affiliated with a health system, and micropolitan were more likely to adopt. We feel this calls for novel longstanding policy that can appropriately incentivize all hospitals to adopt telehealth. Specifically, we suggest removing geographic restrictions from reimbursement policies permanently, which would incentivize rural hospitals to integrate interoperable EHR systems and expanding Remote Patient Monitoring billing opportunities for more types of health organizations.

Additionally, we found that hospital investment in telehealth was disproportionally distributed between several telehealth capabilities. More than half of all hospitals with telehealth capabilities adopted telehealth consultation services that connect the hospitals’ specialists through video or telephone to remote patients. Telehealth capabilities for stroke care which have relatively strong evidence of benefit, [15], [28] were adopted at more than 50% of all hospitals with telehealth capabilities. Telehealth eICU systems which have high implementation costs for hospitals were adopted by <30% of all hospitals with telehealth capabilities.

While a previous study highlighted the positive association between state-level policies on hospitals’ adoption of telehealth capabilities [26], we found that in 2018, in contrast, state-level policies had no significant impact on hospitals’ decisions adopt telehealth. Since this analysis the COVID-19 pandemic pushed healthcare systems nationwide to rapidly expand their telehealth capabilities. To minimize in-person visits, many patients’ visits were replaced with virtual visits either through video or by telephone [29]. Accordingly, temporary new reimbursement policies were updated and implemented to allow providers to supply this type of care [27]. However, these policies will expire soon, unless new ones are implemented, which would likely lead to a drop in the rapid replacement of in-person visits [31]. In fact, data published in May 2020 showed an emerging rebound of in-person visits across all specialties as of mid-May 2020, when the number of new COVID-19 cases dropped [32]. Moreover, the percentage of telehealth visits for under-served patients who live in rural areas decreased during the pandemic [29]. This evidence unsurprising given our findings of significant differences in the adoption of telehealth capabilities between micropolitan and rural hospitals, in favor of the former. Indeed, to boost the provision of telehealth based care in rural hospitals the federal government temporary removed geographic restrictions that prevent hospitals located in certain statistical areas to bill for telehealth services [33].

A good example for such a barrier exist in the case of spoke and hub telestroke networks that allow off-site neurologists to diagnose, evaluate, and intervene in real-time when patients in rural areas suffer strokes [34]. While telestroke networks reduce mortality and save costs for rural hospitals, the initial investment in these networks represent a significant financial burden for small, unaffiliated rural hospitals. [28] Permanent removal of geographic restrictions would help justify such investment as hospitals will be able to bill payers for telestroke services regardless of location [28].

A complementary strategy would modify incentives to those rural hospitals that adopt interoperable electronic health records with telehealth capabilities. Our analysis showed that hospitals that implemented EHR systems were significantly more likely to adopt telehealth capabilities. Rural hospitals, in particular, require interoperable EHR systems that coordinate care between different providers and cross-geographic regions, as they often deliver complex medical care locally [35]. Thus, incentivizing the implementation of interoperable EHR systems with telehealth capabilities could address rural hospitals’ need to connect with distant specialists, enable sharing of patient data between providers, and coordination of the administrative processes for virtual patients. As a result, the costs of care coordination will decrease and the degree of telehealth adoption in these settings will grow.

An alternative approach towards driving telehealth adoption in hospitals that lack the capital and infrastructure for such an investment could be based on the expansion of billing opportunities for telehealth services. For example, allowing hospitals to bill for greater amounts of monthly Remote Patient Monitoring time, at higher rates, and for multiple sessions a day could encourage broader adoption of Remote Patient Monitoring capabilities in hospitals, although this could also result in gaming.

Delivering safe care during the COVID-19 pandemic has required every type of healthcare organization to replace in-person care with virtual care [36]. Under these unusual circumstances, allowing Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC), rural health centers, and home health agencies to bill for Remote Patient Monitoring services could create opportunities for more health organizations to adopt Remote Patient Monitoring capabilities [30]. Redesigning telehealth reimbursement policies with more billing and reimbursement opportunities can pave the way for less wealthy hospitals to replace in-person care with telehealth care in the post-pandemic future.

5. Conclusions

This analysis of US hospitals demonstrated that state level telehealth policies were not associated with telehealth adoption unlike large, affiliated, major teaching hospitals in micropolitan areas. As the role of telehealth-based care is shifting from fringe to mainstream due to temporary policy updates, policymakers, providers, and payers should decide whether to revert these reforms back or to progress to a new national telehealth approach once the current public health emergency comes to an end. Permanent removal of geographic restrictions from reimbursement policies, incentivizing rural hospitals for integrating interoperable EHR systems and expanding RPM billing opportunities for more types of health organizations can help drive further integration of telehealth capabilities nationwide in the post-pandemic future.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

-

1.

Michal Gaziel-Yablowitz had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

-

2.

Study concept and design: All authors.

-

3.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

-

4.

Drafting of the manuscript: Gaziel-Yablowitz.

-

5.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

-

6.

Statistical analysis: Gaziel-Yablowitz.

-

7.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Gaziel-Yablowitz.

-

8.

Study supervision: Levine.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: David Bates: Dr. Bates reports grants and personal fees from EarlySense, personal fees from CDI Negev, equity from ValeraHealth, equity from Clew, equity from MDClone, personal fees and equity from AESOP, and grants from IBM Watson Health, outside the submitted work. David Levine: PI-initiated grant support from Biofourmis and IBM, separate from the present work.

Appendix 1.

DesRoches CM, Charles D, Furukawa MF, Joshi MS, Kraovec P, Mostashari F, et al. Adoption of electronic health records grows rapidly, but fewer than half of US hospitals had at least a basic system in 2012. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(8). Published online July 9, 2013.

| Hospital characteristics | Non -Respondents (N = 1678) |

Respondents (N = 2796) |

|---|---|---|

| Size | ||

| Small | 889 (40.4%) | 1309 (59.6) |

| Medium | 680 (37.2%) | 1148 (62.8%) |

| Large | 109 (24.3%) | 339 (75.7%) |

| Teaching | ||

| Major | 59 (21.5%) | 216 (78.5) |

| Minor | 270 (33.4%) | 538 (65.6%) |

| No teaching | 1349 (39.8%) | 2042 (60.2%) |

| Ownership | ||

| For profit | 410 (57.8%) | 299 (42.2%) |

| Private non-profit | 910 (33.4%) | 1815 (66.6%) |

| Public | 358 (39.8%) | 682 (60.2%) |

| Location | ||

| Rural | 458 (39.8% | 692 (60.2%) |

| Urban | 1220 (36.7%) | 2104 (63.3%) |

References

- 1.Miller E.A. Solving the disjuncture between research and practice: telehealth trends in the 21st century. Health Policy. 2007;82(2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Totten AM, Hansen RN, Wagner J, et al. Telehealth for Acute and Chronic Care Consultations. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2019. Accessed October 5, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK547239/.

- 3.Donelan K., Barreto E., Sossong S., et al. Patient and clinician experiences with telehealth for patient follow-up care. Am. J. Manag. Care. 2019;25:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berenson R.A., Grossman J.M., November E.A. Does telemonitoring of patients—the eICU—improve intensive care? Health Aff. (Millwood) 2009;28(Supplement 1):w937–w947. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geisler F., Kunz A., Winter B., Rozanski M., Waldschmidt C., Weber J.E., Wendt M., Zieschang K., Ebinger M., Audebert H.J. Telemedicine in prehospital acute stroke care. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019;8(6) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goetter E.M., Blackburn A.M., Bui E., Laifer L.M., Simon N. Veterans' prospective attitudes about mental health treatment using telehealth. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2019;57(9):38–43. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20190531-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dang S., Dimmick S., Kelkar G. Evaluating the evidence base for the use of home telehealth remote monitoring in elderly with heart failure. Telemed. E-Health. 2009;15(8):783–796. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss H.E., Lai K.E., Ko M.W. Survey of telehealth adoption by neuro-ophthalmologists during the COVID-19 pandemic: benefits, barriers, and utility. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castaneda P., Ellimoottil C. Current use of telehealth in urology: a review. World J. Urol. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00345-019-02882-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buvik A., Bergmo T.S., Bugge E., Smaabrekke A., Wilsgaard T., Olsen J.A. Cost-effectiveness of telemedicine in remote orthopedic consultations: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(2):e11330. doi: 10.2196/11330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McWilliams T., Hendricks J., Twigg D., Wood F., Giles M. Telehealth for paediatric burn patients in rural areas: a retrospective audit of activity and cost savings. Burns. 2016;42(7):1487–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHugh C., Krinsky R., Sharma R. Innovations in emergency nursing: transforming emergency care through a novel nurse-driven ED telehealth express care service. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2018;44(5):472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caffery L.J., Farjian M., Smith A.C. Telehealth interventions for reducing waiting lists and waiting times for specialist outpatient services: a scoping review. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;22(8):504–512. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16670495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao M., Hamadi H., Xu J., Haley D.R., Park S., White-Williams C. Telehealth and hospital performance: does it matter? J. Telemed. Telecare 0. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1357633X20932440. 1357633X20932440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shea C.M., Tabriz A.A., Turner K., North S., Reiter K.L. Telestroke adoption among community hospitals in North Carolina: a cross-sectional study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2018;27(9):2411–2417. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armaignac D.L., Saxena A., Rubens M., Valle C.A., Williams L.-M., Veledar E., Gidel L.T. Impact of telemedicine on mortality, length of stay, and cost among patients in progressive care units: experience from a large healthcare system. Crit. Care Med. 2018;46(5):728–735. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huilgol Y.S., Miron-Shatz T., Joshi A.U., Hollander J.E. Hospital telehealth adoption increased in 2014 and 2015 and was influenced by population, hospital, and policy characteristics. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(4):455–461. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ATA State of the States 50 State Telehealth Analysis, Coverage & Reimbursement. American Telemedicine Association, 2019.

- 19.Smith A.C., Thomas E., Snoswell C.L., Haydon H., Mehrotra A., Clemensen J., Caffery L.J. Telehealth for global emergencies: implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J. Telemed Telecare. 2020;26(5):309–313. doi: 10.1177/1357633X20916567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain T., Mehrotra A. Comparison of direct-to-consumer telemedicine visits with primary care visits. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(12) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28392. e2028392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koonin L.M. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January–March 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer S.H., Ray K.N., Mehrotra A., Bloom E.L., Uscher-Pines L. Prevalence and characteristics of telehealth utilization in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22302. e2022302-e2022302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berwick D.M. Choices for the “New Normal”. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2125. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.2018 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement. American Hospital Association, 2018.

- 26.Adler-Milstein J., Kvedar J., Bates D.W. Telehealth among US hospitals: several factors, including state reimbursement and licensure policies, influence adoption. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2014;33(2):207–215. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deville J.-C., Särndal C.-E., Sautory O. Generalized raking procedures in survey sampling. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993;88(423):1013–1020. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1993.10476369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Switzer J.A., Demaerschalk B.M., Jipan X., Liangyi F., Villa K.F., Wu E.Q. Cost-effectiveness of hub-and-spoke telestroke networks for the management of acute ischemic stroke from the hospitals’ perspectives. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2013;6(1):18–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortega G., Rodriguez J.A., Maurer L.R., Witt E.E., Perez N., Reich A., Bates D.W. Telemedicine, COVID-19, and disparities: policy implications. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(3):368–371. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Affairs (ASPA) AS for P. Telehealth: Delivering Care Safely During COVID-19. HHS.gov. Published April 22, 2020 (accessed February 19, 2021). https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/telehealth/index.html.

- 31.Establishing A Value-Based ‘New Normal’ For Telehealth | Health Affairs Blog. Accessed December 1, 2020. 10.1377/hblog20201006.638022/full. [DOI]

- 32.The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Outpatient Visits: A Rebound Emerges | Commonwealth Fund. (accessed December 1, 2020). https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/apr/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits.

- 33.Post-COVID Telehealth Priorities Letter to Congress. ATA. Published June 29, 2020. (accessed December 1, 2020). https://www.americantelemed.org/policy/post-covid-telehealth-priorities-letter-to-congress/.

- 34.McSweeney S., Pritt J.A., Swearingen A., Kimble C.A., Coustasse A. Telestroke: overcoming barriers to lifesaving treatment in rural hospitals. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2017 http://bok.ahima.org/doc?oid=302221 (Summer) (accessed December 1, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill E., Dykes P.C., Rudin R.S., Storm M., McGrath K., Bates D.W. Technology-facilitated care coordination in rural areas: what is needed? Int. J. Med. Inf. 2020;137:104102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffman D.A. Increasing access to care: telehealth during COVID-19. J. Law Biosci. 2020;7(1) doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsaa043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]