Abstract

This study aims to examine the association between family communication and psychological distress with coping as a potential mediator. The study also developed and validated the Family Communication Scale (FCS) in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Participants (n = 658; 74.9% female) were general public ranged in age between 18 and 58 years (mean age = 26.38, SD = 10.01). The results showed that family communication directly influenced psychological distress and indirectly influenced through approach coping. However, avoidant coping was not directly associated with psychological distress, nor did it mediate the association between family communication and psychological distress. The findings suggest that people, who have better family communication, highly engage in approach coping which in turn leads to better psychological health in face of adversity. The findings have important empirical and theoretical implications.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, family communication, approach coping, avoidant coping, psychological distress

Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic had drastic effects on individuals’ lives, mental health, daily activities and family relationship and communication all over the world (Prime, Wade, & Browne, 2020; Reddy & Gupta, 2020). The first official cases of COVID-19 were reported in China at the end of 2019 (Zhu, Wei, & Niu, 2020). Since COVID-19 pandemic has spread to all over the world, there were more than 195.2 million confirmed cases and more than 4.2 million deaths across the globe, as of 28 July 2021 (Center for Systems Science and Engineering, 2021). Governments and health authorities implemented either partial or full to prevent the spread of the virus (Fisher et al., 2020).

Since 12 March 2020, Turkish Government also implemented a variety of COVID-19 restrictions including weeks-long full-time lockdowns, endorsement of quarantine for 14 days for all passengers arriving in Turkey from other countries, providing distance learning and closure of non-essential businesses (Oncu, Yıldırım, Bostancı, & Erdoğan,, 2021; WHO, 2020; Yıldırım & Güler, 2020). Furthermore, since 1 March 2021, Turkish Government announced another four-tier system on local COVID-19-related restrictions and provinces that have been divided into four different risk groups: low (blue), medium (yellow), high (orange) and very high (red) based on infection rates (Tanca, Aydoğ, Murphy, & Zincirlioğlu, 2020).

All the precautions mentioned suggest how the disease could be dangerous and fatal (Guner, Hasanoğlu, & Aktaş, 2020). Although vaccination has been commenced in many countries at the very beginning of 2021, countries are still under the pressure caused by the anxiety of new variants of this virus (Gallagher, 2021). Even if the lockdowns will be eased in future due to some medical developments, the habits gained during the pandemic such as social distancing may keep influencing individuals, families and societies (Kalil, Mayer, & Shah, 2020). The long-term restrictions forced families and individuals to find out how to balance the economic and health demands while it also pushed some family members to stay away from their parents, siblings and other relatives (Biroli, Bosworth, & Della Giusta, 2020). Some people have already developed new daily life attitudes to adapt to the new changes and cope with lockdown measures (Tang & Li, 2021). Large-scale tragedies such as current pandemic increase the likelihood of the occurrence of stressors. However, intensifying warnings by the health authorities regarding prevention of the virus transmission have a profound influence on family communication and family-centred coping strategies (Hado & Feinberg, 2020).

Well-being and health of individuals in the face of adversity remain a top concern for health authorities. Pandemic-related stressors have caused many mental health problems including depression, anxiety and traumatic stress disorders (Ozamiz, Santamaria, Gorrochategui, & Mondragon, 2020; Yıldırım & Özaslan, 2021). While close family members living together may develop stronger coping strategies to deal with pandemic-related stressors (Salin, Kaittila, Hakovirta, & Anttila, 2020), those who are lonely for a long time during the pandemic may suffer from distress, extreme anxiety, loneliness, sorrow and pain (Shanahan et al., 2020; Yıldırım, 2021; Yıldırım & Güler, 2021). As such, it is important that individuals hold effective coping strategies people benefit from to overcome from adversities, solve emotional dilemmas, improve psychological well-being and decrease the pressures that stressful conditions may cause (Yıldırım & Maltby, 2021). Psychological resources like adaptive beliefs, meaning in life, motivations, social and communicational skills are also important to protect mental health in difficult times (Gómez-Salgado, Andrés-Villas, Domínguez-Salas, Díaz-Milanés, & Ruiz-Frutos, 2020). Skills and capacity of a family to cope with stressful situations, receiving intra-family communication support and holding adaptive behaviours to deal with stressful events and conditions also play important roles (Alshehri et al., 2020; McCubbin & Figley, 2014)

Furthermore, during the stressful times, close family relations and partaking in daily activities to some extent provide families help families to overcome from the experienced situations (Cluver, Lachman, & Sherr, 2020). Therefore, studies provided evidence regarding the necessity of family-centred care and inter-family collaboration (e.g. family members presence) in relation to coping with stressful events (Chukwu, Okoye, & Onyeneho, 2019; Rubino, Esparza, & Chassiakos, 2020). Failure to achieve such collaborations may cause anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress during and after the adversity while family-centred care has the potential to improve the treatment results (Srivastava, 2014, p. 65).

Family per se and supports from relatives, partners, friends, neighbours and significant others are significant sources of psychological support particularly during chaotic times (Buchanan & McConnell, 2017). Family coping strategies can reinforce family resources and relationships to protect the members from traumatic situations (Kiser, 2015, p. 92). Family communication in difficult times may develop resilience through more powerful and supportive relationships (Prime, Wade, & Browne, 2020). Those who have better family communication may engage in approach coping which may in turn lead to better psychological health in the face of adversity (Marra, Buonanno, & Vargas, 2020). These dynamics are generated by the communication and support among family members (Sari, Retna, & Daulay, 2019).

Family Communication and Psychological Distress During Pandemic

COVID-19 pandemic caused individuals to have anxiety, stress and concerns for their future to some extent (Bakioglu, Korkamaz, & Ercan, 2020). Fear and anxiety are most common psychological reactions that individuals experience in difficult times (Salari, Hosseinian-Far, Jalali, & Vaisi-Raygani, 2020). Family communication and coping strategies are important factors during stressful times. Also, coping strategies affect the quality and development of relationships in families (Maguire, 2012, p. 76). Other factors including conflict, number of stressors that disturb family relationship and availability of intra/inter-family communication may also affect coping strategies (Gaff & Bylund, 2010). Therefore, it appears that there is a bidirectional interaction between family communication and coping. Family communication and coping are also influenced by factors including social and cultural structures of the society, socioeconomic level of the family, educational level and accessibility to different services and opportunities (Arias & Carter, 2017). Both concepts affect family organisations, provide internal and external support and create inter-community communication (Fisher & Nussbaum, 2015; Wittenberg, Goldsmith, & Ragan, 2020).

Family communication differs from ordinary interpersonal or intergroup communication. Family communications helps individuals to develop family adjustment, and cope with family distress, and other psychosocial problems (Le Poire, 2006; Segrin & Flora, 2005). Thus, family members contribute to a family culture and communication through generating intimacies, norms and values (Taipale, 2019, p. 110). In particular, during difficult times like current pandemic, family communication becomes more important since it enables family members to express their concerns, fears and anxiety, and this will help them to protect their psychological health. However, in unhealthy families where there are poor communication and relationship, various problems including interpersonal conflict may exist (Hado & Feinberg, 2020). As such, family communication is important in times of crisis.

Present study

With the literature sketched above, this study aimed to examine the associations between family communication, coping styles and psychological distress. In particular, we hypothesized that (i) family communication would have a significant effect on coping styles and psychological distress, (ii) coping styles would have a significant effect on psychological distress, and (iii) coping style would mediate the association between family communication and psychological distress. Given the adverse impact of the current health crisis, understanding the mitigating factor is pivotal for health care providers and policymakers to effectively respond to the crisis and better manage future outbreaks or similar disasters.

Method

Participants

The study participants consisted of 658 Turkish young adults drawn from the general public. Of the participants, 74.9% of them were females, and they ranged in age from 18 to 58 years (M = 26.57, SD = 9.82). More than one-fifth of the sample consisted of those who belonged to average perceived socioeconomic background (80.1%). The majority of participants obtained an undergraduate degree (73.6%). Some participants (4%) reported that they were confirmed with COVID-19.

Measures

Family communication

Family communication during the COVID-19 pandemic was measured using Family Communication Scale (FCS) developed for the purpose of this study (see Appendix). To assess the level of family communication, the research team initially developed nine items. The items were generated based on an extensive literature review concerning the positive communication in family during the health crisis along with a review of available family relationship scales and the experiences of people under the stressful situations. Three experts in the field reviewed the items to establish the content validity. These experts confirmed the face and content validity and suggested minor revisions. Following the revisions, the scale was presented to participants who answered each statement using a 4-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the scale demonstrate greater levels of positive family communication. All items were then exposed to an exploratory factor analysis. More information regarding psychometric properties of the scale is presented below.

Coping

Coping strategies were assessed using the Brief-COPE Scale (Carver, 1997). The scale is a 28-item self-report measure of coping with challenges. The scale includes 14 subscales (active coping, self-distraction, denial, substance use, use of instrumental support, use of emotional support, venting, behavioural disengagement, planning, positive reframing, acceptance, humour, self-blame and religion) with two items per subscale. Patients are asked to answer each item on a 4-point Likert scale ranging between 1 (I have not been doing this at all) and 4 (I have been doing this a lot), with a higher score on each coping strategy indicating greater use of the specific coping strategy. This scale was translated into Turkish by Tuna (2003). Based on previous studies (Carver, Scheier & Weintraub, 1989; Eisenberg, Shen, Schwarz, & Mallon, 2012), we created a total score for both approach coping (active coping, planning, acceptance, positive reframing, seeking informational support and seeking emotional support) and avoidant coping (substance use, denial, venting, self-distraction, self-blame and behavioural disengagement). In this study, the internal consistency estimate for the scale was satisfactory for both approach coping (Cronbach’s a = 0.76) and avoidant coping (Cronbach’s a = 0.73).

Psychological Distress

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) was used to evaluate general psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2002). The K10 comprises 10 short statements, and each statement is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). A total score can be obtained by sum of all responses, with higher scores signifying greater levels of psychological distress. The scale was adapted into Turkish Altun, Ozen and Kuloglu (2019). In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Procedure

An online survey was administered to participants who volunteered to take part in the study. A message contained the study link was disseminated online to participants. Social networking sites such as Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp were largely used to collect data for the study. Participants were fully informed that their responses to study questionnaire could be kept anonymous, private and confidential. They were also informed that no identifying information is needed in their questionnaire. All participants were made aware about the withdrawal from the study at any time without giving any reason. Once participants voluntarily gave the informed consent at the first page of online survey, they were asked to proceed to the study questionnaires.

Data analysis

A two-step analytical approach was carried out to test the hypothesized structural model. In the first step of analysis, descriptive statistics, internal consistency reliability and correlation coefficient were explored. Skewness and kurtosis statistics with their associated values < |2|, which refer to acceptable normal distribution (West, Finch & Curran, 1995), were employed to assess the normality assumption of the measures used in this study. Afterwards, the Pearson correlation analysis was run to explore the relationship between the variables of this study. In the second step, a mediation model was conducted to analyse the mediating effect of approach coping on the relationship between family communication and psychological distress. The proposed mediation model was performed using the PROCESS macro (Model 4) for SPSS version 3.4 (Hayes, 2018) which is a useful approach in terms of providing various complicated regression paths that other statistical software does not provide. The bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 resamples to calculate the 95% confidence intervals was used to examine the significance indirect effect (Hayes, 2018; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). All data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 and AMOS version 25 for Windows.

Results

Psychometric properties of FCS

We presented psychometric properties of the FCS to improve the utility of the scale. The factor structure of the FCS was examined using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Exploratory factor analysis was initially conducted on nine items. The analysis suggested the removal of three items due to poorly loading (less than .32) on the general factor. Following extracting these items from the scale, the analysis was run again. The results yielded a one-factor solution that has a salient eigenvalue of 3.29 and explained 54.75% of the variance, with factor loading ranging from .49 to .87. Confirmatory factor analysis was then performed using multiple data model fist statistics and their cutoff values: the standardized root means square residual (SRMR)and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) where the values ≤0.05=good, ≤0.08 = adequate and ≤0.10 = acceptable; the Tucker–Lewis index and comparative fit index where the values ≤0.95 = good and ≤0.90 = adequate (Hooper, Coughlan & Mullen, 2008; Hu & Bentler, 1999). The measurement model, which included the six items loading to family communication latent construct, presented good-data model fit statistics (X2 = 50.36, df = 8, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.09, SRMR = 0.036). Factor loadings of the scale were adequate – strong and ranged between 0.37 and 0.91. The findings also showed that the FCS had a good Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.82). Collectively, the results presented initial evidence showing that the FCS could be used to assess the positive family communication in times of health crisis in Turkish adults.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Descriptive findings showed that skewness and kurtosis values ranged between −.03 and 1.48, suggesting that all measures were relatively normally distributed. The internal consistency reliability estimate of the scales was good, ranging from .73 to .93, as presented in Table 1. Additionally, the correlation results demonstrated that family communication was positively correlated with approach coping and negatively correlated with psychological distress. Approach coping was negatively correlated with avoidant coping and psychological distress. Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between avoidant coping and psychological distress.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between the study variables.

| Variable | Mean | SD | Skew | Kurt | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family communication | 18.34 | 4.23 | −0.73 | −0.03 | .82 | — | .27** | .07 | −.19** |

| 2. Approach coping | 34.57 | 5.92 | −0.52 | 0.22 | .76 | — | −.22** | −.18** | |

| 3. Avoidant coping | 25.10 | 4.38 | 0.54 | 1.48 | .73 | — | .12** | ||

| 4. Psychological distress | 25.02 | 9.96 | 0.46 | −0.56 | .93 | — |

Note. **p<.001.

Mediation model

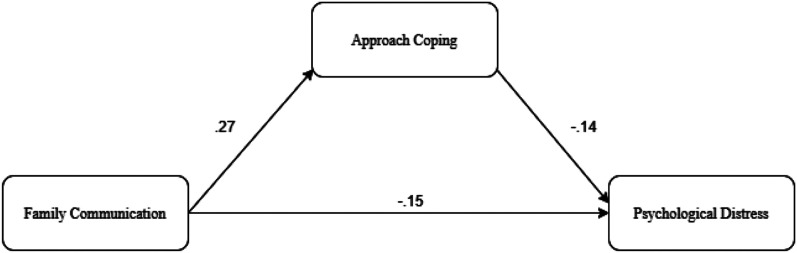

Mediation analyses were conducted to examine the mediating effect of approach coping on the relationship of family communication with participants’ psychological distress. Results from the mediation analysis indicated that family communication had a significant predictive effect on participants’ approach coping (β = .27, p<.001) and psychological distress (β = −.15, p < .001). Approach coping had a significant predictive effect on psychological distress (β = −.14, p < .001). Family communication explained 7% of the variance in approach coping. Family communication and approach coping together accounted for 5% of the variance in psychological distress. The indirect effects of family communication on psychological distress through approach coping were significant (β = −.09, 95% CI [−.15, −.03]) since 95% confidence interval did not include zero. The standardized predictive effects showing the associations between the analysed variables are reported in Figure 1 and Table 2. These results suggest that approach coping is a critical resource to increase the impact of family communication in the experience of less psychological distress among Turkish young adults in the face of adversity.

Figure 1.

Proposed mediation model indicating the association between the variables. Note. All coefficients were significant at p < .001.

Table 2.

Unstandardized coefficients for the mediation model.

| Consequent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Coeff | SE | t | p |

| M (Approach coping) | ||||

| X (family communication) | .37 | .05 | 7.10 | <.001 |

| Constant | 27.72 | .99 | 27.97 | <.001 |

| R2 =.07; F = 50.40; p < .001 | ||||

| Y (psychological distress) | ||||

| X (family communication) | −.36 | .09 | −3.83 | <.001 |

| M (approach coping) | −.23 | .07 | −3.44 | <.001 |

| Constant | 39.46 | 2.50 | 15.81 | <.001 |

| R2 = .05, F = 18.10; p < .001 | ||||

| Indirect effect of X on Y | Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| Family communication–>Approach coping–>Psychological distress | −.09 | .03 | −.15 | −.03 |

Note. Number of bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals: 10,000. SE = standard error. Coeff = unstandardized coefficient. X = independent variable; M = mediator variable; Y = outcomes variable.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has significant impacts on mental health and communication of individuals across the globe. Pandemic also changed family communication (Marra, Buonanno & Vargas, 2020). In this study, we presented a framework for family communication and psychological distress with approach coping as a potential mediator. The results suggest that family communication directly influenced psychological distress and indirectly influenced by approach coping. In parallel with previous studies (Buchanan & McConnell, 2017; Hado & Feinberg, 2020), the findings suggest that people, who have better family communication, and highly engage in approach coping, would have better psychological health in face of adversity. However, avoidant coping was not directly associated with psychological distress, nor did it mediate the association between family communication and psychological distress.

The present findings supported the hypotheses of the study, indicating that coping strategies, particularly approach coping, mediated the association between family communication and psychological distress. Since early of 2020, COVID-19 pandemic has become a global health crisis affecting lives of millions of people in the world. Stressful experiences in the face of adversity negatively affect individuals’ psychological health (Shahsavarani, Abadi, & Kalkhoran, 2015). Considering the psychological impacts of quarantine as a measure of pandemic (Brooks et al., 2020; Hawryluck et al., 2004; Reynolds et al., 2008), understanding the factors related to COVID-19 pandemic and the role of mitigating factors (e.g. coping) that may help to protect psychological health of people is vital for professionals to facilitate mental health services during and after the pandemic. Such an understanding will also foster better management of similar subsequent disasters.

Consistent with the findings of the current study, earlier research showed that family communication was an important contributing factor for psychological health and well-being (Marra et al., 2020). Coping strategies serve a primary factor to protect and foster psychological health and well-being in face of adversity (Yıldırım, Akgül & Geçer, 2021). The present findings suggest that individuals who experience high levels of positive family communication use more approach coping styles, which in turn allow them to experience less psychological distress in the face of adversity. There is evidence to support this in the available literature. For instance, individuals with higher adaptive coping strategies tend to have better mental health and well-being (Yıldırım, Akgül, & Geçer, 2021). Coping strategies help people to deal with stressors and promote psychological health and well-being by fostering them to move forward towards growth and flourishing (Lohman, & Jarvis, 2000). These results suggest that coping, especially approach coping, is a critical mechanism for promoting one’s psychological health in the context of adversity (Yıldırım et al., 2021).

Further, this study developed and reported preliminary evidence concerning the psychometric properties of the FCS as a measure of family communication. The results showed that the FCS is a unidimensional scale with a high reliability and construct validity that can be used in research and practice to assess the level of positive communication in family during difficult time. Such a scale does not only stimulate international scholars to conduct research in family communication and psychological health but also allow them to compare research outcomes across cultures.

Implications and limitations

Stressful times may cause anxiety and change the dynamic of the family structure and relationships. Therefore, having well-structured family communication and coping strategies will keep family members together and help them to cope with the stressful times. Findings from the present study support the idea that adaptive coping strategy is an essential factor to promote psychological health during difficult times. The present study showed that higher positive family communication fosters greater use of approach coping, which in turn leads to better psychological health during stressful times. Mental health providers could develop and implement intervention and prevention services to promote psychological health and well-being during and after the health crisis. With the integration of approach coping in these programs, it is believed that these services could facilitate the promotion of psychological health of individuals in the context of stressful situations. Coping strategies are empirically and theoretically found to be an essential mechanism to promote and protect psychological health and well-being in the face of adversity (Razurel, Kaiser, Sellenet & Epiney, 2013). As such, professionals could design and implement coping-based preventions and interventions programs to foster psychological health during the pandemic.

Even though this study presented important evidence regarding the associations between family communication, coping and psychological distress which have important implications for research and practice, the emerging findings should be taken into account in the light of several methodological limitations. Firstly, the data were collected using self-reported measures, which could have carried some subject-related biases, and future research should examine the associations among the analysed variables by implementing different assessment approaches such as peer reports. Secondly, this study used a cross-sectional design which surely cannot provide a definitive conclusion regarding the causal relationship among the employed variables. Therefore, it is important for future research to use longitudinal design to present further insights into the relationships between the study variables. Thirdly, the proposed model was tested using a newly developed scale of family communication. Although we showed that the FCS was a reliable and valid instrument to assess the family communication, undoubtedly further research is needed regarding its psychometric properties. The scale needs to be tested in different contexts with different samples. Finally, gender was not proportionally distributed, and it may have affected emerging results. Therefore, the findings of the present study should be replicated with a more diverse sample that is approximately equally distributed in gender.

In conclusion, the present study reported that family communication directly affected psychological distress and indirectly influenced by approach coping. Our results emphasize the importance of coping strategies in the relation between family communication and distress. Understanding the associations between the above-mentioned variables can facilitate preventions and intervention programs aimed to reduce psychological distress in family communication by focussing on improvement of adaptive coping strategies.

Acknowledgement

We thank to all participants who voluntarily contributed to this study.

Appendix.

Family Communication Scale

Please think of your communication with your family in the face of adversity such as during the COVID-19 pandemic and indicate your agreement with all the following statements which apply to you by selecting a number from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

1 = Strongly disagree

2 = Disagree

3 = Agree

4 = Strongly agree

| 1. I can freely share my feelings and opinions with my family members. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. I understand value of positive communication with my family members. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. I am satisfied with the way that we communicate in our family. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. In our family, we make decisions together. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. I enjoy spending time with my family. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. In our family, we motivate each other to create a great family environment. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Footnotes

MY: conceived the research idea; made the research design; analysed the data; interpreted the results; prepared manuscript; EG: collected the data; partly contributed to manuscript preparation.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Research Data Policy and Data Availability Statements: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ORCID iD

Murat Yıldırım https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1089-1380

References

- Alshehri N. A., Yildirim M., Vostanis P. (2020). Saudi adolescents’ reports of the relationship between parental factors, social support and mental health problems. Arab Journal of Psychiatry, 31(2), 130-143. DOI: 10.12816/0056864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altun Y., Ozen M., Kuloglu M. M. (2019). Turkish adaptation of Kessler Psychological Distress Scale: validity and reliability study/Psikolojik Sikinti Olceginin Turkce uyarlamasi: Gecerlilik ve guvenilirlik calismasi. Advances in Peritoneal Dialysis, 20, 23-32. [Google Scholar]

- Arias V. S.,, Punyanunt-Carter N. M. (2017). Family, culture, and communication. Oxford, USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bakioglu F., Korkamaz O., Ercan H. (2020). Fear of COVID-19 and positivity: Mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty, depression, anxiety, and stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 32, 28. 10.1007/s11469-020-00331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biroli P., Bosworth S., Della Giusta M. (2020). Family life in lockdown. Bonn: The IZA Institute of Labour Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. K., Webster R. K., Smith L. E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912-920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan T.,, McConnell A. (2017). Family as a source of support under stress: Benefits of greater breadth of family inclusion. Self and Identity, 16(1), 97-122. [Google Scholar]

- Carver C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 4, 92-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C. S., Scheier M. F., Weintraub J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Systems Science and Engineering (2021). Coronavirus COVID-19 global cases at Johns Hopkins University. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- Chukwu N.E., Okoye U.O., Onyeneho N.G. (2019). Coping strategies of families of persons with learning disability in Imo state of Nigeria. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 38, 9. 10.1186/s41043-019-0168-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L., Lachman J., Sherr L. (2020). Parenting in a time of COVID-19. The Lancet, 395(10231), 64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg S. A., Shen B. J., Schwarz E. R., Mallon S. (2012). Avoidant coping moderates the association between anxiety and patient-rated physical functioning in heart failure patients. Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 35(3), 253-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J., Languilaire J-C., Lawthom R., Nieuwenhuis R., Petts R. J., Runswick-Cole K., Yerkes M. A. (2020). Community, work, and family in times of COVID-19, Community. Work & Family, 23(3), 247-252. 10.1080/13668803.2020.1756568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C. L.,, Nussbaum J. F. (2015). Maximizing wellness in successful aging and cancer coping: The importance of family communication from a socioemotional selectivity theoretical perspective. Journal of Family Communication, 15(1), 3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaff C. L.,, Bylund L. (2010). Family communication about genetics: Theory and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. (2021). Coronavirus: UK variant 'may be more deadly'. Retrieved fromwww.bbc.com; https://www.bbc.com/news/health-55768627.

- Gómez-Salgado J., Andrés-Villas M., Domínguez-Salas S., Díaz-Milanés D., Ruiz-Frutos C. (2020). Related health factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. International Journal of Environment Research and Public Health, 17(3947), 325. 10.3390/ijerph17113947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guner R., Hasanoğlu İ., Aktaş F. (2020). COVID-19: Prevention and control measures in community. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 50(1), 571-577. 10.3906/sag-2004-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hado E.,, Feinberg L. (2020). Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, meaningful communication between family caregivers and residents of long-term care facilities is imperative. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4–5), 410-415. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1765684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluck L., Gold W. L., Robinson S., Pogorski S., Galea S., Styra R. (2004). SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(7), 1206-1212. 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. (2018). Introduction to mediation moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- HooperCoughlan D.J.,, Mullen M.R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Method, 61, 53-60. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.,, Bentler P.M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 61, 1-55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A., Mayer S., Shah R. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on family dynamics in economically vulnerable households. Chicago: Becker Friedman Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Andrews G., Colpe L. J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D. K., Normand S. L., Zaslavsky A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiser L. (2015). Strengthening family coping resources: Intervention for families impacted by trauma. Oxon: Routledge. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poire B. A. (2006). Family communication: Nurturing and control in a changing World. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lohman B. J.,, Jarvis P. A. (2000). Adolescent stressors, coping strategies, and psychological health studied in the family context. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(1), 15-43. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire K. (2012). Stress and coping in families. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marra A., Buonanno P., Vargas M. (2020). How COVID-19 pandemic changed our communication with families: Losing nonverbal cues. Critical Care, 24, 297. 10.1186/s13054-020-03035-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin H. I.,, Figley C. R. (2014). Stress and the family: Coping with normative transitions. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Oncu M. A., Yıldırım S., Bostancı S. H., Erdoğan F. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on health management and health services: A case of Turkey. Duzce Medical Journal, 23, 61-70. 10.18678/dtfd.860733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozamiz N. E., Santamaria M. D., Gorrochategui M. P., Mondragon N. I. (2020). Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 36(4), 328. 10.1590/0102-311X00054020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K.J.,, Hayes A.F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavioural Research Methods, 403, 879-891. 10.3758/BRM403879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime H., Wade M., Browne D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631-643. 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razurel C., Kaiser B., Sellenet C., Epiney M. (2013). Relation between perceived stress, social support, and coping strategies and maternal well-being: A review of the literature. Women & Health, 53(1), 74-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy B. V.,, Gupta A. (2020). Importance of effective communication during COVID-19 infodemic. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 9(8), 3793-3796. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_719_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds D. L., Garay J. R., Deamond S. L., Moran M. K., Gold W., Styra R. (2008). Understanding, compliance, and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiology and Infection, 136(7), 997-1007. 10.1017/S0950268807009156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino S. J., Esparza L. G., Chassiakos Y. (2020). New leadership for today's health care professionals. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett. [Google Scholar]

- Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(57), 659. 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin M., Kaittila A., Hakovirta M., Anttila M. (2020). Family coping strategies during Finland’s COVID-19 lockdown. Sustainability, 12(9133), 563. 10.3390/su12219133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sari D. K., Retna D., Daulay W. (2019). Association between family support, coping strategies and anxiety in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy at general hospital in Medan, North Sumatera, Indonesia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 20, 458. 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.10.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C.,, Flora J. (2005). Family communication. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shahsavarani A., Abadi E., Kalkhoran M. (2015). Stress: Facts and theories through literature review. International Journal of Medical Reviews, 2(2), 230-241. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L., Steinhoff A., Bechtiger L., Murray A. L., Nivette A., Hepp U., Ribeaud D, Eisner M. (2020). Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 28, 1-10. 10.1017/S003329172000241X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R. H. (2014). Culture, religion and family-centred care. In Shaul R. Z. (Ed), Paediatric Patient and Family-Centred Care: Ethical and Legal Issues (pp. 57-79). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Taipale S. (2019). Intergenerational connections in digital families. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tanca D., Aydoğ E., Murphy A., Zincirlioğlu Ö. (2020). The political and economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic in Turkey. Edam: Istanbul. [Google Scholar]

- Tang S.,, Li X. (2021). Responding to the pandemic as a family unit: Social impacts of COVID-19 on rural migrants in China and their coping strategies. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8, 8. 10.1057/s41599-020-00686-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuna M. E. (2003). Cross-cultural differences in coping strategies as predictors of university adjustment of Turkish and U.S. students (Doctoral dissertation). Turkey: The Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University. [Google Scholar]

- West S. G., Finch J. F., Curran P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with non-normal variables: Problems and remedies. In Hoyle R. H. (Ed), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56-75). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg E., Goldsmith J., Ragan S. L. (2020). Caring for the family caregiver. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020). Turkey’s response to Covid-19: First impressions. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M. (2021). Loneliness and Psychological Distress: A Mediating Role of Meaning in Life during COVID-19 Pandemic. IntechOpen. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.97477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M., Akgül Ö., Geçer E. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 anxiety on general health: The role of COVID-19 coping. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 28, 1-12. 10.1007/s11469-020-00429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M.,, Güler A. (2020). COVID-19 severity, self-efficacy, knowledge, preventive behaviors, and mental health in Turkey. Death Studies, 54, 1-8. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1793434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M.,, Güler A. (2021). Positivity explains how COVID-19 perceived risk increases death distress and reduces happiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 168(110347). DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M.,, Maltby J. (2021). Examining Irrational Happiness Beliefs within an Adaptation-Continuum Model of Personality and Coping. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 10.1007/s10942-021-00405-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M.,, Özaslan A. (2021). Worry, severity, controllability, and preventive behaviours of COVID-19 and their associations with mental health of Turkish healthcare workers working at a pandemic hospital. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 91, 1-15. 10.1007/s11469-021-00515-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Wei L., Niu P. (2020). The novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Global Health Research and Policy, 5, 6. 10.1186/s41256-020-00135-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]