Abstract

The COVID-19 outbreak has created major challenges for transportation companies. Grounded in the dynamic capabilities view theory, this paper adopts a multi-methodological operations management approach to derive scientifically sound insights with regard to handling key customer relationships in the crisis. To be specific, first, qualitative interviews with representatives of small carriers and forwarders as well as an examination of their social media posting are conducted. The qualitative research reveals the customer relationships situation of transportation companies during the COVID-19 pandemic. What specific actions build relational capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic is uncovered. The research model is then tested based on the survey with one hundred Polish SME carriers. Several insights are generated. First, this study provides evidence that among various available networking routines, companies should concentrate on relationship monitoring, conflict handling, and selective relationship downsizing, while initiating new partnerships does not appear to be beneficial. Second, this study suggests that the positive influence of relational caps on company performance is moderated positively by contracts signed between partners and negatively by the financial debt of focal companies. Finally, this study discusses its results with regard to other studies on business relationships in dramatic environmental changes and highlights the corresponding implications.

Keywords: COVID-19, Transportation companies, Dynamic capabilities, Multi-methodological study, SMEs, Asymmetric relationships

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has created huge challenges and risks (Chiu and Choi, 2016, Choi et al., 2019, Sun et al., 2020) for business service operations (Wang et al. 2015), including the logistics industry (Choi 2020). Just before the COVID-19 outbreak, road transportation was the dominant mode of shipping goods within the European Union (EU) (IMF 2020). The transportation, freight and logistics (TFL) industry in EU is traditionally orchestrated by big European companies, mainly manufacturers and retailers from such countries like Germany, UK, and France. Road transportation, being the main part of this industry, is very complex with more than 600,000 trucks and 740,000 driver jobs (Klaus 2019a). Besides, thousands of smaller transportation companies simultaneously serve the market (Klaus 2019a). Note that the location of transportation companies is very diverse in the EU between member states as the vast majority of drivers are located in less developed countries such as Poland and a few other Central and Eastern European countries. This dispersion between supply and demand for transportation has created debates on new transportation regulations. There are proposals to normalize environmental and social outputs but not well-taken owing to many issues. For example, the rule that enforces the local labor laws, including the minimum wages, on transportation companies is controversial. This rule might have a detrimental effect not only on the efficiency of the EU’s TFL industry but also on the whole EU economy in the long run (Klaus 2019b).

In 2017 Polish transportation companies still had a major share in the EU transportation market. However, in the last two years (before the COVID-19 pandemic), they already started suffering as there was a 6.4% drop in transported cargo already in 2018 (Stefaniak 2020). The industrialists deeply worry as the president of Employers Association Transport and Logistics Poland commented: “The Polish companies would lose at least a half, if not two-thirds of the current share in the market of international transport services” (Stefaniak 2020). It is important to note that the Polish TFL industry is rather fragmented. Thus, Polish small and medium-size transportation companies play an important role. It also means that these “truckers” are usually too financially constrained to build their capacities for value-adding services. They also highly depend on their direct customers, mostly the forwarding companies from Western Europe. Considering this specific background, there is no surprise that the COVID-19 pandemic that hit the EU in March 2020 was interpreted as a sign of apocalypse by many Polish SME carriers. Nobody expected this. In March 2020, the new regulations on city lockdown (i.e. people were allowed to leave their homes only for some professional purposes) and international transport (i.e. within EU member states, passenger transportation entirely stopped and cargo transportation was restricted) became a nightmare for Polish carriers. Since then, the turnovers have immediately dropped by around 40%, and the whole multi-level TFL sector in Europe has gone for cost cutting. This has created huge tensions in the relationships among carriers, forwarders, and shippers (Ołdak 2020). According to the sales director at one of biggest Polish transportation companies, the costs of COVID-19 are unequally shared by the companies operating at different tiers of EU’s logistics chain: “If biggest market players continue using their power position for profits on the arms of carriers, that currently do not even make any profits, it will soon result in lack of stock” (Ołdak 2020).

Considering the pessimistic market situation in the EU’s TFL sector before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the strategic role small companies play within this sector, this paper focuses on exploring the connection between relationship management capabilities and transportation SMEs performance during a crisis like COVID-19. Specifically, this paper uses insights mainly from “dynamic capabilities view” (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000, Teece et al., 1997) supported by “transaction costs view” (Williamson 1999) to propose a research model that hypothetically connects relationship management capabilities and transportation SMEs performance during a crisis. Although dynamic capabilities view (DCV) is one of the most influential paradigms in strategy literature, especially with regards to market volatility, research applying DCV towards companies functioning in a crisis like COVID-19 is rare. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature related to organizational recovery from natural or humanitarian disasters (Ballesteros and Wry, 2017, Battisti and Deakins, 2017, Kaltenbrunner and Reichel, 2018) and economic crisis (Fainshmidt et al., 2017, Makkonen et al., 2014, Nair et al., 2014). According to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that applies DCV in the logistics industrial context to examine strategic customers management in a market facing a crisis such as COVID-19 (see Section 1.3 for the detailed research contribution statement).

The study follows the multi-methodological approach (Simchi-Levi, 2014, Choi et al., 2016, Chiu et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020). It follows the well-known triangulation principle (Choi et al. 2016) in empirical operations management studies by combining results from statistical analysis of quantitative survey data and insights from qualitative interviews. The qualitative research also helps explore if and how transportation companies use some relationship management capabilities towards their strategic customers. Details of the research methodologies will be discussed in Section 3.

This study’s contributions are shown in the following. Firstly, it extends prior research on relationship management capabilities. Specifically, this study advises that in the context of dramatic environmental changes companies should concentrate on relationship monitoring, conflict handling, and selective relationship downsizing. However, initiating new partnerships does not appear to be beneficial. Second, the study complements prior research on formal/hard and informal/soft control mechanisms with regard to supply chain partners’ opportunistic behaviour (Clauss and Bouncken, 2019, Tangpong et al., 2010). It provides evidence uncovering that these two mechanisms amplify each other in managing partnerships under the pandemic lockdown. Thirdly, while dynamic capabilities are generally being associated with company entrepreneurial growth (Teece, 2007, Teece, 2009), this study treats dynamic relational capabilities as an approach to drive the company through threats emerging in the market environment. By doing this, the study contributes to the fast-developing literature on “dark side” of supply chain relationships (DuHadway et al., 2019, Tsai et al., 2012, Villena et al., 2011).

2. Related literature and empirical research model

2.1. Dynamic relationship management capabilities and company performance under COVID-19

For over a decade, after a few pioneering publications have appeared (Möller and Svahn, 2003, Ritter et al., 2002), research on relationship management capabilities or relational caps, has achieved great progress. This stream of research highlights that there is no single capability solely responsible for inter-firm networking. Instead, various capabilities together, depending on the context would help (Forkmann et al., 2018, Kohtamäki et al., 2018, Zacharia et al., 2011). However, prior research applying capabilities perspective to explore inter-organizational relations in the context of handling dramatic changes in the business environment is very limited. Table 1 concisely summarizes this stream of research.

Table 1.

Prior studies on relational capabilities handling dramatic environmental changes.

| Authors | Related concepts on capabilities | Main research insights |

|---|---|---|

| Pananond (2007) | Networking capabilities, Technological capabilities | Thai multinational firms adjust their networking capabilities under economic crisis by switching from personalized, relationship-based networks into more formal inter-organizational ties as well as developing industry-specific technological skills |

| Almor (2011) | Technological capabilities | The resilience to economic crisis may be facilitated by properly developing “tight” networks and customized strategies by small, high-tech Israeli multinationals. |

| Ikeda and Nagasaka (2011) | Disaster risk copying capabilities | Facing diasters in Japan, there is a need for capabilities developed on network level linking various actors (“government, community and business” actors) to share information, foster communication, group decision making and collaborative actions. |

| Makkonen et al. (2014) | Regenerative capabilities, renewing capabilities | In the context of global financial crisis of 2008 integrating knowledge through external networks is the core component of renewing capabilities. |

| Useem et al. (2015) | Natural disaster management | Responding to disaster in Chile, a multi-national mining firm was able to use its local grass-roots relationships, affiliate networks, and partner organizations to assess the damages and achieve better tailor recovery. |

| Battisti and Deakins (2017) | Capability to integrate resources from external inter-organizational sources | In the post-disaster environment (after earthquake) of New Zealand, a firm’s capability to integrate resources from external sources positively affects the extent to which a disaster impacts its resource base. |

| Tang et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional cooperation capability | Managing nuclear power plant accidents in China demand developing capabilities combining centralizing political-administrative planning with a network governance mechanism. |

| Dias et al. (2020) | Innovation capability, developed inter-organizational relationships, NPD | The Portuguese SMEs seem to revise their mechanism of developing new products during a crisis by using greater variety of capabilities to foster innovations. |

The prior research on relational capabilities (caps) focuses on two main areas which are disaster risk management, either natural or human mistake disasters (e.g. Ikeda and Nagasaka, 2011, Useem et al., 2015) and economic crisis management (e.g. Pananond, 2007, Makkonen et al., 2014). Disaster risk management studies generally suggest that nowadays effective management of disasters must go beyond organizing legal institutions and centralized government planning. It needs organizational capabilities that enable the sharing of information sources and collaborative actions among government, NGOs, business entities, and local communities. Noteworthy, the proper positioning of such capabilities is quite blurred, but these capabilities do not reside at the level of any micro business entity. Thus, the network coordination mechanism must be somehow facilitated through governmental intervention which is not surprising. In the case of disasters, there is a need to apply a large-scale perspective, usually a regional one to act fast while facing dynamic events threatening people's life and health. In contrast to that, prior studies on economic crisis management only focus on a single company perspective which is insufficient. Nevertheless, prior studies in the area suggest that utilizing “exploiting capabilities” may require (i) managing informal connections and social capital (Makkonen et al. 2014) or (ii) the ability to formalize business connection (Pananond 2007). However, these studies focus on company networking in the crisis applying “a long perspective” in evaluating what has changed in the firms’ networking patterns under the crisis. See Table 1 for examples (e.g., Pananond, 2007, Dias et al., 2020, etc.).

Being responsive is critical in logistics systems (Choi 2013). Prior studies did not explore what kind of strategies companies should apply to their strategic relationships as an immediate response to the crisis to secure some assets invested in these relationships. There is hence a gap in the literature because the economic crisis accelerates the opportunistic behaviour in business relationships. This paper fills this gap.

Additionally, prior studies on relational capabilities in the crisis context are fragmented across industries. This paper focuses on the transportation and logistics industry which is believed to be very much crisis-sensitive. The insights are novel and have practical value.

To be specific, this paper has its theory base from the strategy literature, where the rising market turbulence was acknowledged (d'Aveni et al. 1995) and so-called dynamic capabilities specific business capabilities adjusted to this turbulence were proposed (Teece et al., 1997, Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000). The dynamic capabilities are seen as processes implemented by the organization that help them in “proactive adjustment towards environment” (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000). Teece, 2012, Di Stefano et al., 2014 located these processes in two main aspects of organizational functioning, namely “managerial skills and decision making” and “long-standing routines across organizations”. Importantly, the dynamic capabilities embrace both. Although the capabilities building could be a lengthy path-dependent process (Vergne and Durand 2011). When companies face dramatic instability in the market environment, the dynamic capabilities take the form of simpler and faster decision-making (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). Therefore, this study assumes that in typical SMEs in logistics, the company capabilities may be developed and applied in response to black swan phenomena like the COVID-19 outbreak.

The dynamic capabilities view (DCV) theory suggests that dynamic capabilities may be applied not only by seizing new resources but also by mobilizing existing resources (Teece, 2007). Therefore, DCV may also be applied to the existing relationship base, i.e. assuring appropriate distribution of relational rents in the existing relationship portfolio from the perspective of a focal company (Dyer et al. 2008). Note that prior research on applying relational caps to secure company resources from the crisis is scarce and there is no consensus on what business practices constitute the core of such relational caps. This study hence follows Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) and contributes by concentrating on exploring such relational caps in a very volatile crisis environment. We focus on relevant communication and perceptual aspects of SMEs behaviours during the crisis that could potentially constitute relational caps. We concentrate on “soft competences” elements of relational caps, i.e. negotiation skills (Mitrega et al., 2012). Some “hard assets”, i.e. mutual investments between partners or long-term contracts, are treated as “beyond boundaries” of crisis relational caps. Although such “hard assets” are very important for understanding firms’ relational situation in the crisis (Dyer and Singh 1998), such assets are not likely developed in a short time when the crisis hits the SMEs and their supply chains. In such context, any new relationship-specific investments are usually not feasible, because companies experiencing crisis usually withdraw from new resource commitments. In the same spirit, the complex contracts as a hard element of company networking might be very helpful during the crisis because they function as safeguards for mutual distribution of relational benefits (Anderson and Dekker, 2005, Gorovaia and Windsperger, 2018). In a crisis, one can expect that existing contracts may be exploited and sometimes revisited and negotiated. However, new long-term contracts are usually avoided because companies must first overcome the day-to-day financial challenge under the crisis. Therefore, in this study, we define crisis relational caps of SME in the crisis as a set of processes that are implemented by SMEs in response to the crisis to protect SMEs from being exploited by their strategic customers during the crisis.

SMEs are widely perceived as more vulnerable concerning the economic crisis, given their inadequate preparedness for cash flow breakdowns and the lack of professional management (Herbane 2010). They can be also more easily hurt in their strategic partnerships, because business partners may take advantage of a relatively bigger size and protect their financial situation (Alvarez and Barney 2001). Facing various forms of pressure that strategic customers may use towards their smaller counterparts (Oukes et al. 2019) and increased likelihood of unethical business networking during the crisis, relational caps developed as communication and analytical practices during the crisis can be of crucial to SMEs. Therefore, we hypothesize that: “There is a positive link between SMEs relational caps applied to their relationships with partners and SMEs performance during the crisis (H1)”.

2.2. Moderation effects related to contractual complexity and company debt

In the early versions of transaction costs theory (TCT), the exchange between market entities was supposed to happen only in two general coordination forms; either external coordination (market) or internal coordination (hierarchy, firm). In this approach, the hierarchical exchange between entities is not the most effective means due to bureaucratic transaction costs incurred. However, the later version of TCT, especially TCT’s applications in strategy research, would present a more complex picture which assumes various types of governance mechanism ranking from “ideal market” (discrete transactions, zero transaction costs), “hazard” (repeatable relations, some transaction costs, no safeguard features), “hybrid” (high transaction costs, contractual safeguards) to “firm” (highest transaction costs, strongest administrative safeguards) (Park, 1996, Williamson, 1999). From the perspective of business relationships’ management, such continuum provides alternative strategic options which should be chosen at various points of time and concerning the context: “try markets, try hybrids (long term contractual relations into which security features have been crafted), and resort to firms when all else fails (comparatively)” (Williamson, 1999, p. 1091). In the market, SMEs are exposed to various forms of transaction risks, especially when dealing with larger counterparts which may use their bargaining power position for opportunistic actions (e.g., delaying payment or even not paying at all). Therefore, SMEs are recommended to develop some safeguard mechanisms which may relate to establishing complex contracts and significant mutual investments. Hence, the contracts between the business partners would increase the likelihood of the efficient share of the “relationship pie” (Gorovaia and Windsperger 2018) and control for opportunistic hazards (Anderson and Dekker 2005). However, this research does not focus on these safeguards, because in the specific context of pandemic crisis, it is not likely that any SMEs would be able to introduce some new safeguards in their strategic partnerships (e.g. mutual investments, establishing contract) to minimize the threats related to partners opportunistic behaviour. Such safeguards might be very helpful to manage their key accounts. Thus, they are taken into consideration as research control variables (see later in the relevant section). However, this research focuses on relational caps (mainly pragmatic communication routines) that can be developed and mastered in a relatively short time as a countervailing tool for SMEs dealing with strategic business relationships.

As a consequence, this research treats contractual safeguards mainly from the perspective of their hypothesized interaction with relational caps. Specifically, as key customer relationships in the pandemic crisis are the focal point here, it is assumed that financial difficulties push key customers into “intensified opportunistic behaviours” including illegal practices. Thus, the contractual safeguards may be useful not only to mitigate such threats directly (i.e. increased likelihood the customer pays not time and therefore transportation company turnover is secured), but also indirectly (through increased inclination for open negotiations). On the other hand, without such complex contracts in the relationships between among transportation companies and forwarders as their strategic customers (which are quite likely in spot based transactions), applying relational caps by these companies might be very difficult. This argument is based on the fact that in such situations, the crisis negotiations (e.g. about prolonged terms of payment) may likely turn into a “zero-sum communication game”. Transportation SMEs as the weaker business partners in our study, should be able to utilize their contractual safeguards in communication with their strategic partners because detailed contracts would facilitate efficient conflict resolution (Lumineau and Malhotra 2011). Therefore, this study hypothesizes: The contractual safeguards fuels a positive link between SMEs relationship management capabilities applied to their relationships with key partners and SMEs performance during the crisis (H2).

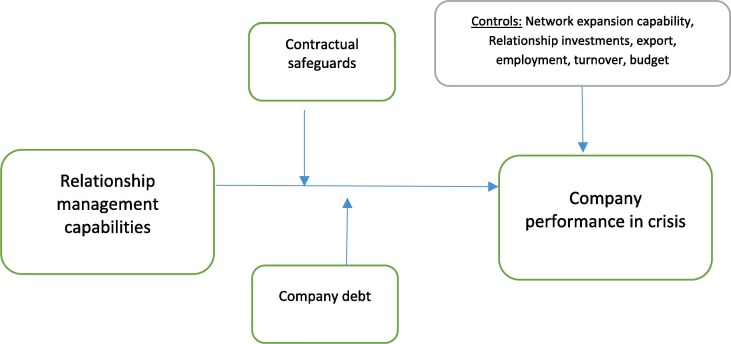

In general, building and applying dynamic capabilities involves significant financial and non-financial costs, because it assumes a non-trivial change in the way companies operate and act (Fainshmidt et al., 2016, Teece, 2007). Responding rapidly to new market conditions demands resource slack, because the company resources must be directed to the areas of uncertain outcomes, and the managers without adequate resources may find such decision too risky (Bromiley 1991). The link between access to resources and dynamic capabilities has been demonstrated empirically (Fang and Zou 2009). While dynamic capabilities are by per se to build new combinations of company resources, their application is conditioned by current access to resources, even in the context of discontinuous market changes like a financial crisis (Makkonen et al. 2014). In the case of SMEs the low asset liquidity, e.g. high financial debt, limits their ability to seize the business opportunities (Serrasqueiro and Nunes 2008), so logically it limits also flexibility concerning acting within business relationships. For example, instead of selective downsizing the business partnerships that become problematic during the crisis, indebted companies may continue these relationships even at “zero margins” just to maintain some income to pay basic financial commitments, e.g. leasing rentals or salaries. Consequently, heavily indebted companies may be less selective with regard to potential new collaborations, e.g. new customers, and they may accept very uncomfortable conditions. Therefore: The SMEs financial debt moderates negatively a positive link between SMEs relationship management capabilities applied to their relationships with key partners and SMEs performance during the crisis (H3). The research model is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

The research model.

3. Research methodology

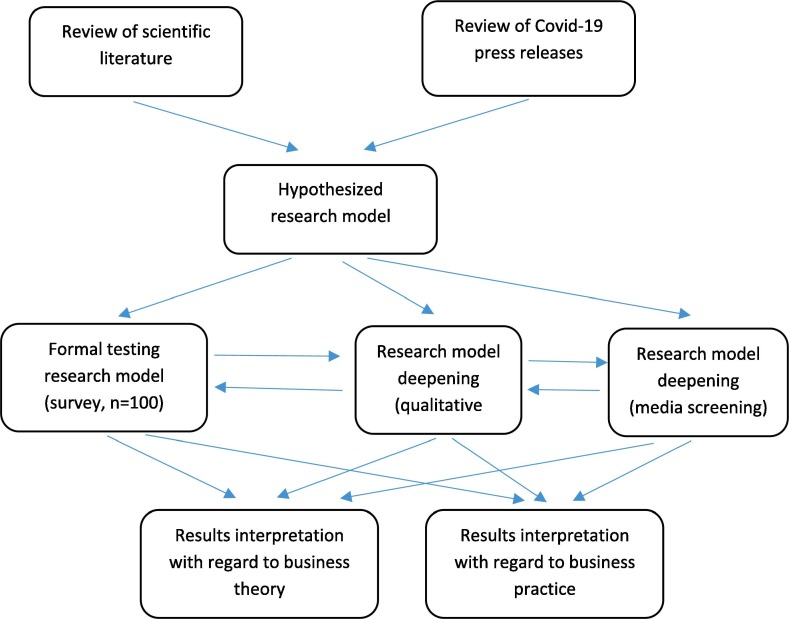

This study combines deductive reasoning with induction that is especially useful for explaining the situation deviating from the typical realm, where there is a need for some sort of creativity in the research approach (Dubois and Gadde, 2002, Kovács and Spens, 2005). Such an approach seems to be relevant for delivering action-based conclusions, which seems to be very needed for companies during the covid-19 pandemic. The coronavirus pandemic can revolutionize supply chains across the world and could potentially question some existing theories. Therefore, although the research model was developed based on premises of capabilities view of company strategy (Teece et al., 1997, Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000) with some insights from transaction cost theory (Williamson 1999), this research combines various sources of data to explore inductively the specific research context and validate initially the theoretical framework before it is tested on the sample of SMEs. In other words, it adopts a multi-methodological approach (Choi et al. 2016), which combines qualitative interviews and empirical quantitative survey-based statistical analyses, to derive insights and provide scientifically sound conclusions. Fig. 2 illustrates the main stages of the research process.

Fig. 2.

The applied multi-method research process.

3.1. Data sources and measures

This research presents the COVID-19 coronavirus situation of Polish road transportation SMEs to describe the context of interactions between transportation companies and their strategic business customers and explore if and how these companies apply relational caps under the pressure of coronavirus. In the first two weeks of April 2020, when the COVID-19 was spreading fast around the world, there were telephone interviews carried out with representatives of 8 Polish transportation companies combined with monitoring media news about the transportation industry and observing posts published by representatives of transportation companies on social media. The characteristics of companies and informants that were involved in interviews are briefly presented in the appendix.

We have implemented a few ex-ante and ex-post tools to address the validity and reliability of insights from qualitative research (Wilhelm et al. 2016). First of all, the semi-structured interview protocol was designed to cover all main aspects of relationship management capabilities which were previously conceptualized by Mitrega et al. (2012) as so-called networking capability with regard to downstream and upstream supply chain partnerships. Specifically, we have asked informants about their companies’ actions undertaken in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic related to customer relationships at all main stages of the relationship cycle: relationship initiation, relationship development, and relationship termination. Secondly, as we have interviewed small companies and our informants were mainly company owners, the multi-informant technique was treated as not relevant, however, we had to make sure that we gather research insights from both carriers and their business customers as well – that is why we have interviewed two forwarders and insights gathered this way were generally in line with insights retrieved from carriers. Additionally, we have triangulated interview results with social media posting related to the current situation in the transportation sector by screening the closed facebook group “Companies that do not pay Trans/Timo” (PL: “Firmy, które nie płacą Trans/Timo”). The “truckers” were very active at this profile sharing information about unreliable business partners and activities that can effectively help them in managing such uncomfortable relations. Thirdly, we have assured our informants and moderators of the Facebook group that all information we gather will be processed in a strictly anonymous way. This aspect was treated as very important by informants, because the interview referred to controversial dimensions of business relationships, e.g. conflict handling or relationship fading. Fourthly, the interviews were partially transcribed, and together with social media posting, these transcripts were analyzed by two coders, e.g. research coordinator and post-doc specialized in social sciences. The codes prepared inductively in parallel were later compared and all differences were discussed to achieve the consensus concerning data interpretation.

The insights from interviews combined with the review of variable indicators used in prior research were used to develop the questionnaire covering the main research constructs. For the relational caps the measurement items proposed previously by Mitrega et al. (2012) with regard to conflict management capability and relationship termination capability were adapted to the research context. Firm performance as a focal outcome variable was measured according to Reinartz et al. (2004) and informants were asked about how they assess the performance of their companies relative to competitors in the current coronavirus pandemic period (April 2020)

The “contractual safeguards” were measured according to Liu et al. (2010)’s measures for contractual complexity: Please indicate what part of vehicles at your disposal comes from external sources (leasing/credit/rental) in comparison to your own equity (own assets): 5 items; from 0% (1) to more than 75% (5)”. To test if theoretical links presented here hold when combined with other links that could provide an alternative explanation to the company performance during the crisis, the model was enriched with a set of control variables: specific relationship investments, export level, employment, turnover, and sales/marketing budget (relative to competitors). The majority of these controls were single-item constructs, while relationship investments (concerning key customer accounts) was measured as a latent construct adapted from Zhang et al. (2016). Because relational caps as our main independent construct were conceptualized and measured concerning company processes oriented at existing relationships this research has also controlled for the effect of “Network expansion capability or Expanding” (Zaefarian et al. 2017) that refers here to the processes oriented at building new partnerships with strategic customers. The main items used in this research are presented in Appendix. Note that, to adapt the items referring to relational caps to the specific context of small and medium-sized carriers in their relationships with customers, we explicitly asked the informants to refer in their answers to current activities relevant for their relationships with “key, strategic customers” only. We did it because we wanted to acquire the insights not about “long-term established” company routines and relational assets (i.e. social capital embedded in existing partnerships); but we wanted to focus on these activities that can constitute simple strategic orientations which can function as an immediate tool to handle the most volatile business scenario (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000). We assumed that relationships with key customers would constitute a very risky but also most important context of applying relational caps. This assumption is logical because the key customer relationships would involve companies that were bigger than the SME logistics companies. However, as our research was not dyadic, we did not control for the size of the buying companies that our informants had in mind while referring to key customer relationships.

The Biostat research agency specialized in conducting surveys for scientific purposes was used as an outsourced professional company to facilitate data gathering among transportation companies in a difficult period related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The agency has used the Bisnode, a comprehensive database of Polish companies, to randomly select a sample of 1500 Polish transportation companies. During the lockdown period of 10–20 April the agency has used computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) to reach companies from the selected sample. The CATI technique was used for the flexible and iterative selection of knowledgeable informants in the companies, usually company owners or top managers. At the same time this technique allowed for relatively fast data gathering which was treated as important, because the research team was oriented at gathering data exactly during the pandemic lockdown to acquire unbiased insight into the research phenomenon as it develops. On April 13th the data gathering was stopped with 100 filled questionnaires and after assuring that all selected companies received invitations at least once. The relatively small response rate (7%) resulted from a few factors. As the database contained transportation companies of all kind, the initial questions have filtered out companies that did not match the research scope, i.e. they were oriented at passenger transportation, they did not maintain any relationships with key customers and they were not the small or medium company. The April lockdown was also a very difficult period for surveying managers of transportation companies because these managers were very anxious concerning their business survival. The effective sample characteristics are presented in the Table 2 .

Table 2.

Transportation companies' sample descriptive statistics (n = 100).

| Number of employees | 10–49 employees −75% 50–99 – 14% 100–249 – 11% |

| Annual turnover | No more than 2 million Euro – 51% From 2 to 10 million Euro – 38% More than 10 million Euro – 11% |

| Company age | Longer than 2 and shorter than 5 years – 1% 5–10 years – 6% Longer than 10 and less than 30 years – 77% 30 years or longer – 17% |

| Export sales intensity | Only domestic sales – 22% Export 1–25% − 12% Export 26–50% − 16% Export 51–75% − 21% Export 76%-99% − 26% Only foreign customers sales – 3% |

| Firm ownership | Domestic capital only – 95% Foreign capital share – 2% Foreign capital only – 3% |

| Informants knowledge about key account relationships | Quite good knowledge – 6% Good knowledge – 39% Very good knowledge – 55% |

| Informants positions | Owner or management board – 60% Sales/marketing manager – 2% Sales/marketing specialist – 22% Other position – 16% |

Among 100 surveyed companies, the majority were companies that employed less than 50 people (75%) and their annual turnovers were no larger than 2 million EU (51%), well-matching the definition of small companies. The companies in the sample functioned quite long in the industry (95% longer than 10 years). Only 22% of these companies have focused on domestic transport only, while 50% of them earned incomes mainly from international transportation. Almost all (95%) of the sampled transportation firms were entities of domestic (Polish) ownership only. As a remark, some attempts were made to select the most appropriate informants in each investigated company. The majority of these informants were company owners or board members (60%). Around ¼ were either specialists or managers employed in sales/marketing departments, while 16% were individuals occupying “Other position”. This category refers to informants that were employed at positions entitled differently than positions from the pre-defined list but they performed similar roles in the companies, usually mixing roles from various traditionally coined positions. The most typical positions here were: director, key account manager, forwarding manager, and commercial proxy. The selected informant was checked to be knowledgeable about the investigated issues. For instance, they were asked directly (see results concerning knowledgeability presented in Table 2) and sometimes indirectly (by training interviewers to respond carefully in situations when the informant was not sure about the meaning of some notions). However, our questionnaire was pretty clear for our informants, thanks to prior qualitative research which worked as a reference and pilot study for notions we used in our questions.

4. Analysis and results

4.1. Qualitative research results

Comprising insights from interviews with managers, mass media news, and social media, the picture of the transportation industry under the COVID-19 pandemic is found dramatic. Although in the opinion of informants this sector has gradually moved into a strong competition and low margins and a very ambiguous regulatory environment for several years already, the COVID-19 crisis from its beginning has caused a severe drop in turnovers, i.e. usually around 30–50%, and turned this industry into the quite hostile and atomistic system, where business actors try to make their living through using all methods available. The typical key customer of the companies that were interviewed, i.e. forwarder or manufacturing company, has dramatically downsized their operations during the lockdown and it had an immediate impact on the cargo transportation services they needed, especially in terms of its quantity. The situation was found as very dynamic with the potential to become more stable following unclear pandemic tendencies, governmental decisions about cross border transportation, etc.

Being financially pushed by the crisis and observing the dynamic rise of competition, the shippers become more inclined to use various forms of coercion against carriers. According to representatives of transportation companies, their customers enforce worse price and quantity conditions, and these new conditions are usually accepted because carriers try very much to keep the customer relationship. Even in case of customers functioning on quite stable markets, e.g. supermarkets, there is a tendency to exploit ranging competition between carriers by moving some transportation orders from long-term contracting to discrete contracts arranged through freight exchange platforms like www.timocom.co.uk or https://www.trans.eu/. These platforms are used by many companies shipping goods to adjust the freight price expectations to current market conditions which means that more and more customers impose such auction-based prices on the carriers that they collaborated with before the crisis: “In the time of crisis nobody wants to overpay” [Informant ζ, Middle size freight forwarder]. During the interviews, some managers complained they lost long-term customer partnership, because many other companies providing their services at very low prices, while providing at such low prices does not make sense in comparison to just downsizing the business, e.g. “On the freight exchange today I saw some people going for 60 cents per km. Madness…” [Informant ε, Middle size carrier]. According to the opinion of the same informant, the carriers that work on such prices spoil the industry, but they do so because they strive to pay current obligations that way, e.g. taxes, salaries, or rental fees. Although negotiating with new customers is very difficult, because the decision to take the freight on the exchange platform must be made extremely fast to make it before competitors do, in existing key partnerships the atmosphere is still a bit better: “I tend to give a bit more to this company because I know they will provide what is expected, especially when some unusual road congestion problems appear” [Informant ζ, Middle size freight forwarder]

Many informants observed the increase of unethical opportunistic behavior which take the form of either postponing the payment or even not paying for orders at all. This is one of the reasons that made Facebook profile “Companies that do not pay” very popular among transportation companies during coronavirus lockdown. Therefore, monitoring and disseminating information on the credibility of existing and potential customers becomes vital to protect from being exploited. The transportation companies use various formal pressure to claim their debts, e.g. sending formal notes, informing exchange platforms, hiring debt collection agencies. Importantly, some companies also try to build their source of coercive pressure, e.g. fueling massively at the customer’s facilities for final clearance. If the customer does not want to pay on time, they are informed that the expensive load of petrol could be kept as compensation. In the same spirit, the cargo that was shipped by the customer is sometimes treated: “I have worked for X for some time, but they stopped paying (…) I am calling the X saying: you did not pay for this and that, so we stop cooperation, but before we do it pay for all prior freights and this one that we do now or the goods are not unloaded” [Informant ε, Middle size carrier]. However, not all small carriers seem to know their rights and they sometimes prefer to look for a new shipment instead of claiming their rights in the current contract: “These /swear word/ feast on many carriers not even trying to fight for themselves” [post on Facebook profile “Companies that do not pay”, retrieved on 27.04.2020].

4.2. Measures validity and PLS-SEM results

Taking into consideration all constructs from the model, i.e. baseline model variables and control variables, the survey questionnaire contained 20 items associated with 5 latent constructs: Relational Caps, Contractual safeguards, Firm performance, Relationship investments, and Expanding (see all items in the appendix). Before estimating the hypothesized links between the constructs, the measurement was evaluated in terms of its reliability and validity using SmartPls 3.0 (Ringle et al. 2018). Table 3 suggests that the measures meet all standard thresholds for reliability and convergent validity: AVE greater than 0.5, Composite Reliability greater than 0.6; Cronbach's Alpha greater than 0.7.

Table 3.

Construct reliability and convergent validity.

| Cronbach's Alpha | Rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship management capabilities | 0.843 | 0.853 | 0.884 | 0.560 |

| Firm performance | 0.808 | 0.958 | 0.863 | 0.613 |

| Contractual complexity | 0.806 | 1.000 | 0.867 | 0.686 |

| Network expansion capability | 0.705 | 0.715 | 0.815 | 0.525 |

| Relationship investments | 0.716 | 0.735 | 0.840 | 0.637 |

To assure the appropriate level of discriminant validity, individual AVE of each construct should be higher than the squared correlation between the two constructs (Fornell and Larcker 1981). According to Table 4 , this condition is met as the square root of the AVE for each individual construct is displayed at the table diagonal, while correlations between constructs are presented below the diagonal.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity according to Fornell-Larcker criterion.

| Contractual safeguards (Contract) | Firm performance (Performance) | Expanding | Relationship investments (Invest) | Relational Caps (RCaps) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contract | 0.829 | ||||

| Performance | 0.193 | 0.783 | |||

| Expanding | 0.222 | 0.179 | 0.725 | ||

| Invest | 0.029 | 0.187 | 0.018 | 0.798 | |

| RCaps | 0.337 | 0.311 | 0.678 | 0.083 | 0.748 |

Considering the features of the dataset, which is the relatively small sample size and non-normal data distribution, the PLS-SEM technique was chosen as more relevant instead of covariance-based (CB) SEM (Hair et al., 2011, Hair et al., 2017). PLS-SEM has been popularized actively amongst management scholars (Becker et al. 2012), has an established procedure for testing the measurement quality of higher-order constructs, and gives a good approximation of CB-SEM results when CB-SEM requirements cannot be met (Hair et al., 2017).

Following Hair et al. (2013), bootstrapping was used to assess the path coefficients’ significance. The number of bootstrap samples was 5,000, with Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) Bootstrap as the most stable estimation method. Table 4 present the PLS results with regard to the model containing 3 main hypothesized links (H1-H3) and all potential links between control variables and company performance.

The link Relational Caps - > Company performance was found statistically significant (p less than 0.05) supporting H1, while two significant moderation effects support H2 and H3. Among control variables two factors seem to have a clear negative impact on company performance in the crisis: Employment and Export intensity, while acquired government help has a significant positive impact and prior Relationship investments and contractual safeguards have a marginally positive impact too (p less than 0.1 threshold). As PLS-SEM does not provide any commonly accepted goodness of fit criterion, Garson (2016) was followed to evaluate the structural model. Specifically, R2 = 0.54 and Q2 = 0.26 for the company performance in the model with controls; and, R2 = 0.43 and Q2 = 0.20 for the company performance in the model without controls suggests medium effect size for the model. Additionally, F square values for each hypothesized exogenous variables clearly above 0 (see Table 5 ) suggest acceptable effect sizes for the relatively small sample (Garson 2016).

Table 5.

PLS path coefficients.

| Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T-Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | F square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCaps -> Performance | 0.257 | 0.148 | 2.173 | 0.030 | 0.103 |

| RCaps × Contract-> Performance | 0.304 | 0.163 | 2.154 | 0.031 | 0.017 |

| RCaps × Debt -> Performance | −0.278 | 0.122 | 2.245 | 0.025 | 0.317 |

| Debt -> Performance | −0.052 | 0.104 | 0.506 | 0.613 | 0.004 |

| Contract -> Performance | 0.234 | 0.160 | 1.536 | 0.125 | 0.083 |

| Employment -> Performance | −0.197 | 0.104 | 2.006 | 0.045 | 0.053 |

| Export intensity -> Performance | −0.229 | 0.100 | 2.601 | 0.009 | 0.102 |

| Govern Help -> Performance | 0.169 | 0.089 | 2.037 | 0.042 | 0.046 |

| Mark. budget -> Performance | 0.140 | 0.124 | 1.390 | 0.165 | 0.057 |

| Network expand-> Performance | −0.032 | 0.135 | 0.924 | 0.355 | 0.047 |

| Relat Duration -> Performance | 0.108 | 0.084 | 1.219 | 0.223 | 0.014 |

| Invest -> Performance | 0.213 | 0.133 | 1.906 | 0.057 | 0.141 |

| Turnover -> Performance | 0.129 | 0.119 | 1.311 | 0.190 | 0.093 |

5. Research implications

5.1. Discussions

This study corresponds with prior research on relationship management capabilities with regard to either upstream or downstream supply chain partners (Malhotra and Mackelprang, 2012, Moshtari, 2016, Yang et al., 2018, Zacharia et al., 2011) which provided the evidence for the statistical link between such capabilities and the focal company performance.

This study corresponds with prior studies about relational capabilities in dramatic environmental changes (e.g. Pananond, 2007, Makkonen et al., 2014) by providing the evidence that such capabilities may be useful in addressing the pandemic crisis by small and medium-size enterprises, specifically through applying communication routines of handling conflicts and descaling within the existing base of key customer relationships. Therefore, this study extends prior studies in this area as they have concentrated mostly on different aspects of relationship management, i.e. integrating knowledge through external networks (Makkonen et al. 2014) and fostering social capital (Dias et al. 2020). However, similarly to these prior studies and in contrast to the studies on relational caps for disaster management (Ikeda and Nagasaka, 2011, Useem et al., 2015, Tang et al., 2017), our study locates the relational caps at the level of individual company which uses relational caps to protects its market position from negative environmental impacts.

Introducing the received governmental help as a control variable into the model, the relational caps of focal transportation companies were shown to be more beneficial than the institutional aid even though the positive governmental influence on company performance was also confirmed in our data. Therefore, it may be argued that from the perspective of individual transportation SMEs, the best system of crisis risk management should combine the individual business strategies with the support of country institutions. This point is in line with prior studies on managing humanitarian disasters (Tang et al. 2017). However, one should also acknowledge the important methodological limitation related to this result. The data set was collected in the first two weeks of April 2020 and the informants were referring to the perceived governmental help only for this period. It is hence possible that some performance results of institutional help were experienced later. Specifically, a bit later than we conducted our research (in late May 2020), the second part of governmental aid was introduced in Poland (i.e. “Tarcza Ankryzysowa” PL) with some solutions tailored for transportation companies which contained not only financial supports but also procedural supports, e.g. free legal advisory or online administrative proceeding (complementing traditional offline system). Although the majority of transportation companies benefited somehow from the immediate support provided by the government (e.g. pension system reliefs, operational leasing support), more than 40% did not use any institutional support at all at this early stage. The key reason is that they did not meet the official criteria (e.g. they were too big) or they were not sure about how to apply for the support. According to the survey conducted at the beginning of May 2020, the majority of managers from transportation companies declared that the immediate governmental support was useful but “to very limited” concerning the serious problems the industry was facing at that time.

The study parallels Pananond (2007) in terms of suggesting that companies may benefit from introducing a more selective approach towards their business partners during the economic crisis. However, it also extends Pananond (2007) by illustrating that some elements of this strategy should be implemented as an immediate response to the crisis. Specifically, the proposed relational caps construct would highlight the importance of both “communication routines related to conflict handling” and “analyzing evaluating relationships and withdrawing” (e.g., measured via “We have a procedure to end relationships with the undesired customer”). Although our study does not provide evidence that focal companies were reducing some customer relationships in the COVID-19 outbreak, implementing such an analytical/selective approach towards existing relationships could at least redirect managers’ attention within existing partnerships towards the more promising ones. Additionally, such an approach builds the first step towards restructuring the whole portfolio of partnerships, which was found to be beneficial in the long-term by Pananond (2007). This is also fully aligned with the DCV approach to business relationship management (Mitrega et al., 2012, Mitrega et al., 2018).

The research results with “relationship investments” and “contractual safeguards” as control variables confirm the idea that “hard relational assets” can be a valuable aid during the dramatic environmental changes corresponding to prior research concerning relational caps in humanitarian disasters (Useem et al., 2015) and economic crises (Almor, 2011, Makkonen et al., 2014). This is also in line with the transaction costs perspective because both of these control variables are tools to mitigate “blind opportunism” in conflictual crisis relationships (Williamson, 1999, Anderson and Dekker, 2005, Gorovaia and Windsperger, 2018). In addition, our study extends prior research by providing the evidence that ad-hoc relational caps may be more effectively applied in key customer relationships (thanks to existing contractual safeguards which relate to the investigated moderating effect). In turn, such moderation comes from efficient (Lumineau and Malhotra 2011) conflict resolution, and inclination of partners to identify a win-to-win solution when a conflictual relationship is driven by contractual safeguards. In other words, this study suggests that complex contracts facilitate the use of relational caps because the other side of the business relationship is more open in negotiations.

Some additional factors included in the research model, e.g., “export intensity” and “employment”, may worsen the current performance of investigated SMEs under COVID-19. The negative impact of the first control variable is very intuitive because the research was undertaken exactly during the time of COVID-19 lockdown in Poland when the international borders within the EU were closed or heavily restricted for goods being transported. Since 50% of surveyed companies earned incomes mainly from international transportation, there is no doubt that the lockdown made a huge impact on their profitability at that time. In turn, the negative impact on “employment” may be interpreted through our mixed-methods insights about the pandemic transportation business and the specific performance measure being used. Note that the crisis performance was measured through the items referring mostly to the profitability (e.g. current profitability, current general results), not the company turnover. For larger companies, it was more difficult to reduce some of their fixed costs during the crisis, especially those costs related to salaries and external financing, e.g. leasing costs. For transportation companies hiring more people, it was probably easier to survive the first hit of pandemic drop as they usually had the long-term contracts to keep some earnings. However, their profitability was still damaged through the necessity to pay for some regular obligations. Additionally, the smaller company was more likely to be benefitted from the first wave of governmental support, which could have a relatively significant impact on profitability at that time. Importantly, it is possible that employing other measures at different points of time could provide different research results. Limitations are hence admitted.

Following the premise that there is no single relationship management capability but rather different relationship management capabilities based on internal and external contingencies (Forkmann et al., 2018, Mitrega et al., 2018), this study offers an understanding of relational caps in the specific context of the transportation industry under dramatic pressures of COVID-19 crisis. Specifically, among various networking routines available (Mitrega et al., 2012, Zaefarian et al., 2017) this study provides the evidence that road transportation companies can help themselves in the crisis by applying specific relational orientation: focusing on handling conflicts with existing strategic partners and withdrawing from unprofitable relationships. This strategic trajectory is intuitive, because every crisis pushes companies into various forms of opportunistic behavior including illegal practices, so the focal company must be very careful in crisis partnering in terms of protecting its relationship assets from being unilaterally appropriated by partners.

This study corresponds with the literature on managing supply chain relationship risks (Cheng and Chen, 2016, Mishra et al., 2019, Szczepański and Światowiec-Szczepańska, 2012). There are two main control mechanisms for managing partnering risk: formal tools (governance mode and formal contracts) and informal mechanism (relational norms and trust) (Szczepański and Światowiec-Szczepańska, 2012). This study incorporates both of these aspects either in the form of main hypothesized effects, i.e. the link between relational caps and performance reflecting informal risk-mitigating mechanism or in the form of moderation effects, i.e. the positive link between relational caps and performance alleviated by contractual safeguards. However, in contrast to the majority of prior studies on relationship risk management, the relational caps proposed in this study refers not only to non-intentional risks but also to malicious relational risks understood as intentional disruptions (DuHadway and Carnovale, 2019, DuHadway et al., 2019) which seem to be of great importance in the context of COVID-19 affected supply chains.

Our mixed-methods approach applied here provided the evidence that during the COVID-19 pandemic there was a dangerous tendency to externalize the burden of the crisis on the arms of other supply chain partners which could be detrimental to the stability of the whole supply chain and the logistics industry particularly. Our study confirms the general tendency for intensified blind opportunism in business relationships, as already found in prior economic crisis studies. Thus, this study supplements findings in the contemporary research on B2B conflict management in buyer–supplier relationships (see, e.g., Bradford, et al. 2004; Pfajfar et al. 2019; Ratajczak-Mrozek, et al. 2019) focusing on the ability to self-censor overreaction to negative behavior, using interpersonal social capital and maintaining an image of ethical partner (Huang and Chiu, 2018). This study also complements prior studies on conflict management showing that SMEs may successfully protect their assets in conflictual crisis relationships with business customers by applying relational caps. Using the relational caps was treated in this research as a specific non-coercive strategy for conflict resolution (Pfajfar et al. 2019). However, relational caps go beyond joint problem solving (Bradford, et al. 2004) and social capital. Last but not least, this study extends prior research of relationship conflicts management by testing the usability of some relational strategies for logistics SMEs under COVID-19.

Although this study did not apply longitudinal research techniques, by conceptualizing relational caps with regard to business relationships at various development stages, this study contributes indirectly to the literature on buyer–seller relationship dynamics (Autry and Golicic, 2010, Hussain et al., 2020, Vanpoucke et al., 2014) by providing the evidence that in the industry heavily infected by the COVID-19 pandemic, companies should rather concentrate on these partnerships that are already developed instead of selecting and attracting new business partners. Specifically, among potential networking routines oriented at different relationships in terms of their stage, i.e., “initiation, maturing, ending” (Mitrega et al., 2012), this study provides the evidence that in the very outburst of pandemic crisis (April 2020 in the EU transportation industry), the capabilities related to new partnerships (i.e. network expansion capability as control variables in our model) do not provide the needed financial aid for SMEs. Therefore, while facing the dramatic pandemic momentum, the small transportation companies are rather suggested to utilize capabilities focused on existing partnerships which is in line with the relational caps concept. Although prior research provided evidence that relationship expansion capability is useful to leverage supply chain performance (Forkmann et al., 2016, Zaefarian et al., 2017), it did not examine the situation with a big crisis like CVOID-19.

Following DCV this study emphasizes the multi-stage nature of dynamic capabilities (Teece, 2007, Vanpoucke et al., 2014) by decomposing relationship management into processes related to relationship risk detection (1) and relationship risk mitigation (2) (DuHadway et al. 2019) that parallels dynamic capabilities’ distinction between sensing and seizing (Teece, 2007, Vanpoucke et al., 2014) for systematic improvement of company resources and capabilities vis-à-vis changing market environment. In line with Anand et al. (2009) that conceptualized dynamic capabilities in operation management as continuous improvement initiatives, this study suggest that in the context of the COVID-19 crisis the focal company should continuously question the relationship status quo, i.e. implement routines to systematically monitor costs and benefits of relationships with current strategic customers affected by the crisis. Although our survey does not provide measure to check how long was process of building relational caps in SMEs we investigated, our qualitative research suggests that some of the networking actions discussed in this paper are undertaken rather ad-hoc as a reaction to the pandemic. For example, managers of transportation companies are much more oriented now at downsizing the operations in relation to their behavior before the lockdown and this is because they lost many of their customers, and acquiring new unreliable customers is treated as too risky. Therefore, this study corresponds with Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) who suggested that in dramatically unstable contexts the dynamic capabilities may take form of applying “simple business rules” instead of learning complex organizational routines. Although, this proposition was early accepted in the literature, so far very few studies considered it empirically (i.e. Makkonen, et al. 2014), due to the lack of adequate research context.

As this research explores the perspective of SME transportation companies and their relationship management capabilities concerning their “strategic customers” (as labeled in the questionnaire), these customers were assumed to be larger companies (i.e. forwarders and manufacturers) with stronger bargaining positions. As a result, although partners’ behavioral power (Oukes et al., 2019) was not focused explicitly here, this research corresponds with the literature on power asymmetries in the supply chain (Cowan et al., 2015, Handley and Benton, 2012a, Handley and Benton, 2012b, Johnsen et al., 2020). Similarly to this literature, this research accepts that asymmetries are nowadays an inherent feature of efficient supply chains, especially for small and medium-sized companies. However, in line with some recent studies incorporating the perspective of the dominated supplier (Cowan et al., 2015, Lacoste and Johnsen, 2015, Siemieniako and Mitręga, 2018), our qualitative research illustrates that strong asymmetry is risky as dominant actors try to retrieve all “relationship pie” when being pushed by the pandemic crisis, which in turn risks supply chain sustainability. This study complements prior research on networking in the context of asymmetrical relationships offering relational caps that dominated logistics suppliers may apply towards their business partners to protect their share in relationship benefits. Specifically, this study provides evidence that relational caps applied by transportation SMEs concerning their strategic customers during the crisis were critical.

Last but not the least, this study makes an industry-related contribution with regard to the relationship management strategies in the logistics service industry (e.g. transportation, warehousing, and transshipment). This body of research is fragmented and focuses mainly on different governance forms for improving efficiency and innovativeness of logistics providers from the perspective of retailers or manufacturers outsourcing logistics services (Kopczak, 1997, Tsai et al., 2012, Wallenburg et al., 2019). Thus, the logistics literature discusses relationship risk management from the perspective of the buying company, not from the perspective of the service supplier (Tsai et al. 2012). Recently, Kuo et al. (2017) demonstrated that dynamic capabilities applied by container shipping firms vis-à-vis their market are positively related to their service capabilities with regard to business buyers and their competitive advantage. Our research follows and extends their research by conceptualizing and testing empirically relational caps as a strategic approach applicable by road transportation companies vis-à-vis dramatic turbulences in their markets. The strategic importance of the road transportation sector within the supply chains of contemporary manufacturers comes from the dominance of this transportation mode in many places in the world (Pérez-Bernabeu et al., 2015). Particularly, in European Union, the “truckers” are an irreplaceable component of supply chains orchestrated by multinational corporations. The border restrictions introduced due to the COVID-19 lockdown together with few years of institutional struggles related to the so-called mobility act (Klaus 2019a) put small trackers “at the wall” which means that they either radically change their business strategies or they disappear. Our research does not provide the answer to all of the troubles these companies have, especially it does not offer the guide for any radical innovations, however, relationship management tactics presented leverage their performance in “the April 2020 heart of the pandemic storm”. Thus, managers of EU transportation companies may use these tactics to manage risk related to key partnerships and sustain in the market if they face a similarly dramatic business realm in the future.

5.2. Managerial implications

Although the last few years of disputes concerning the so-called “mobility package” was a tough lesson for EU transportation companies, i.e. anticipated substantially increased operation costs, the COVID-19 lockdown was something that these companies were not prepared for and now they need to find a way to “survive the storm”. Although there is no one panacea in business and no one “magic stick” for a crisis, this research suggests that one of the ways that should be helpful is the appropriate approach towards customer relationships, namely implementing “Relationship management capabilities” or Relational Caps. The insights combined from various sources, including a survey with 100 transportation SMEs, interviews with managers, and studying social media posts, allow for translating such capabilities into some rules or business practices transportation companies may apply during the crisis.

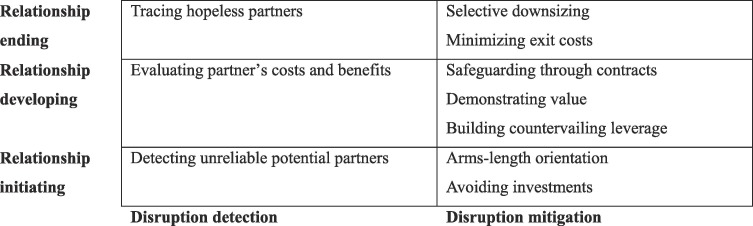

Fig. 3 presents the main relational tactics that are suggested for small suppliers embedded in relationships with business customers during the black swan market turbulences such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Fig. 3 follows the distinction between uncomfortable factor “detection” vs. uncomfortable factor “mitigation” as two distinct stages of relationship risk management process proposed recently by DuHadway et al. (2019), which in turn, mirrors the distinction between “sensing” and “seizing” as two classical sub-processes that together with “transforming” build dynamic capabilities (Teece 2007)1 . On the vertical dimension Fig. 3 is based on distinguishing between different networking stages, namely relationship initiating, relationship developing, and relationship fading that were suggested as components of networking capabilities (Mitrega et al., 2012, Mitrega et al., 2017). Although survey results provide the evidence only for general impact from relational caps related mainly to conflict handling tactics and selective relationship downsizing, our mixed-methods approach allows for constructing a typology of these relational caps along two-dimensional matrix.

Fig. 3.

Typology of relational tactics for managing supply chain disruptions.

This study suggests that during the crisis outburst transportation companies should master their management skills rather with regard to existing customer partnerships than through seeking new collaborators. Relationship management capabilities translate in this case into careful anticipating threats in customer relationships, e.g. detecting early worsening situations, safeguarding assets, and withdrawing from cooperation when necessary. According to this research, the processes oriented at initiating new customer relationships do not influence positively the current performance of transportation companies and this is probably because of volatile times such as the COVID-19 pandemic are not a good context for building new partnerships. During the crisis, many actors in the logistics sector are inclined to maximize short term gains even at the cost of some long-run assets. The new cooperation is usually established through an auction-based mechanism, where arm’s length relationships are facilitated only. Cooperation with existing key customers creates more potential for maintaining profitable freight orders, because there is still some social capital to build on and the transportation companies may demonstrate their value during a crisis, i.e. staying very interactive and reliable in relation to key customers during unexpected road situations, while rapid switching to unknown providers is too risky.

This research suggests that conforming to business partners maybe not enough in crisis and carriers should carefully check if some of their partnerships did not become one-sided only, i.e. working for the benefits of a business customer only. The investments already made in key accounts, e.g. learning specific operational requirements, are probably helpful in these relationships today (as illustrated by the control variable in our model). However, the crisis changes the relationships between forwarders and carriers towards more antagonistic, because all key actors in supply chains reduce their activities and seek additional savings. Such pressure is the source of enormous stress on people in the logistics and it may easily turn them into seeking short-term gains and “externalizing problems on contractors”. Therefore, transportation companies should carefully monitor the forwarders and manufacturers they cooperate with and react early if partners start behaving opportunistically. For example, not paying on time, when the partner used to pay on time regularly may be perceived as a signal that needs careful attention. The transportation companies should also monitor information about their partners in social media because acting opportunistically against other companies is many times revealed there by other carriers. Such instances potentially signal general business inclination that should be detected as early as possible.

Sensing the uncomfortable changes in partners' behavior builds a space for confronting these dynamics, which is not easy because strategic customers of transportation companies are usually more resourceful and they may use various forms of pressure on the carriers they cooperate with. However, this research provides evidence that applying by carriers practices to handle such conflicts is beneficial because such practices are positively linked to the performance of carriers during a crisis. The conflicts with business customers arise frequently from different interpretations of cooperation terms, especially when the situation on roads become unpredictable, e.g. jams at international boards or the unloading area. In such situations, there is a need to maintain contact with the shipper so that any misunderstandings may be discussed and the carrier may have a chance to describe the situation from the perspective of a driver being directly at a place.

This study suggests that the best results may be achieved by combining relationship communication practices with detailed contracts regulating partners' behavior, so the carriers should balance their efforts among both of these elements. Carriers should, for example, behave more actively, when terms for new carriages are established by suggesting detecting the clauses that bring conditions that are not feasible to meet or move the whole operation responsibility only to their side. Whereas possible, these terms should be negotiated, and if this is not possible the transportation company should be at least aware of the risk, especially if the partner’s intention is not clear, i.e. through prior opportunism being observed.

Severe environmental disturbances such as the coronavirus crisis of 2020 threaten the stability of whole international supply chains, so managers of transportation companies must accept that not all strategic partnerships may survive such pressures. This may be very difficult as some of these relationships have been built for decades. However, if the customer relationship is found as spoiled, i.e. the customer doesn’t seem to be willing to pay and tend to be oriented only at cost-cutting, the transportation company should manage the relationship accordingly to protect its assets. This research illustrated some countervailing practices in such situations when business customers act in an unethical way like communicating the partner’s behavior through the freight exchange opinion system and relevant social media groups. Having control over the cargo during transportation is also the leverage of the company position, e.g. by purposive delaying unloading until the money for service is transferred. Such practices should be treated as final measures due to its coercive character and unclear lawfulness. In general, all of these management practices seem to be helpful for transportation companies to effectively safeguard their assets while handling uncomfortable partners.

5.3. Future research and limitations

This empirical study lays the foundation for further studies. For example, theoretical studies employing the mathematical modeling approach can be conducted. Methods such as mean-risk analyses (Choi et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020) can be adopted. Besides, the COVID-19 outbreak has created huge challenges for logistics operations in supply chains. Many important operational risk management tools and measures (Asian and Nie, 2014, Araz et al., 2020) should be examined to help deal with the crisis.

Like other studies in the area, this research has some specific methodological limitations. The main issue is that this study has applied only a perceptual measure of company performance following the general measurement model proposed by Reinartz et al. (2004) with respect to managing customer relationships (i.e., similar but in the context of “normal business realm”). The measure they offered became later utilized in various management science areas, including business-to-business context (e.g. Forkmann et al., 2016, Zaefarian et al., 2017). It was similar to other subjective measures of organizational performance (Dess and Robinson, 1984). In this study, the measure proposed by Reinartz et al. (2004) was adapted to the very specific crisis context by asking the informants to indicate the performance of their companies (general performance, growth, market share and profitability) in relation to “other companies of the similar type” and with regard to “the current situation”. This approach allowed us to identify perceptual performance of investigated companies adjusted to the pandemic crisis momentum. However, it is unclear to what extent the informants were able to evaluate their financial performance in relation to other companies. Thus, further research could be conducted to overcome this limitation by applying other measures, e.g. performance dynamics connecting pre-crisis and post-crisis period (and ideally, also applying objective measures of company performance or at least, the multi-informant approach for perceptual measures (Ketokivi and Schroeder, 2004). Kindly note that such measures were not available in our research setting because only some companies in Poland are obliged to report their results, depending on their size and legal form. Additionally, such objective data is to be reported annually. Thus, for transportation companies that were obliged to report, this data would be available no sooner than around July 2021, far after the timeline for this special issue that we have to follow. However, our measure seems to be acceptable taking into consideration the strong statistical links between subjective and objective measures of company performance found in prior research (Wall et al., 2004, Ketokivi and Schroeder, 2004). Secondly, our mixed methods approach provides additional justification for our research model, because specific networking routines constituting relational caps were indeed found to be beneficial for the situation faced by various explored carriers.

This research focuses on relational caps as applied in the transportation and logistics SMEs in their “key customer relationships” under COVID-19. These relationships were assumed to be asymmetric in terms of behavioral and structural powers (Oukes, et al. 2019). Further research can focus more explicitly on power and dependence asymmetry and their impact on using relational caps. However, such research would demand assessing not only the size and resources of SMEs but also the size and resources of their business partners. As a result, it would require researchers to apply a dyadic measurement of power-related constructs in standard empirical quantitative research (Pfajfar, et al. 2019). Getting the data would hence be challenging.

Last but not least, the data we used in our analyses was based on one institutional setting only, i.e. road transportation industry in Poland. Although we have presented that Polish transportation companies remain an important and “strategic element” of the whole European transportation system and European supply chains, further research should be conducted to see if more insights can be revealed by studying the scenarios in other countries. By going beyond the context of highly entrepreneurial transformative economy like the case of Poland (Skare and Porada-Rochoń, 2019, Dvorský et al., 2019), it will be interesting to explore other logistic systems which are, e.g., largely dependent on asymmetrical relations with transportation companies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maciej Mitręga: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Tsan-Ming Choi: Writing - review & editing, Revision, Advice.

Acknowledgements

The research presented in the paper was sponsored by National Science Centre in Poland (PL – “Narodowe Centrum Nauki”) within the project registration no. 2017/25/B/HS4/01669.

Footnotes

The authors sincerely thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their kind comments on this paper over the past few rounds, especially during this difficult period of time with COVID-19.