Abstract

Introduction

An increasing number of patients are voicing their opinions and expectations about the quality of care in online forums and on physician rating websites (PRWs). This paper analyzes patient online reviews (PORs) to identify emerging and fading topics and sentiment trends in PRWs during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

Text data were collected, including 55,612 PORs of 3430 doctors from three popular PRWs in the United States (RateMDs, HealthGrades, and Vitals) from March 01 to June 27, 2020. An improved latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA)-based topic modeling (topic coherence-based LDA [TCLDA]), manual annotation, and sentiment analysis tool were applied to extract a suitable number of topics, generate corresponding keywords, assign topic names, and determine trends in the extracted topics and specific emotions.

Results

According to the coherence value and manual annotation, the identified taxonomy includes 30 topics across high-rank and low-rank disease categories. The emerging topics in PRWs focus mainly on themes such as treatment experience, policy implementation regarding epidemic control measures, individuals’ attitudes toward the pandemic, and mental health across high-rank diseases. In contrast, the treatment process and experience during COVID-19, awareness and COVID-19 control measures, and COVID-19 deaths, fear, and stress were the most popular themes for low-rank diseases. Panic buying and daily life impact, treatment processes, and bedside manner were the fading themes across high-rank diseases. In contrast, provider attitude toward patients during the pandemic, detection at public transportation, passenger, travel bans and warnings, and materials supplies and society support during COVID-19 were the most fading themes across low-rank diseases. Regarding sentiment analysis, negative emotions (fear, anger, and sadness) prevail during the early wave of the COVID-19.

Conclusion

Mining topic dynamics and sentiment trends in PRWs may provide valuable knowledge of patients’ opinions during the COVID-19 crisis. Policymakers should consider these PORs and develop global healthcare policies and surveillance systems through monitoring PRWs. The findings of this study identify research gaps in the areas of e-health and text mining and offer future research directions.

Keywords: Text mining, Topic modeling, COVID-19, LDA, Dynamics of healthcare topics, Discrete emotions

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19), which originated from Wuhan, China, has been devastating globally. In the United States (U.S.), thousands of daily new cases have been reported since March 2020. The total number of confirmed reported cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., at this writing (June 27, 2020), exceeded 2,537,636 with 126,203 mortalities, and over 13,039,853 cases with 571,659 mortalities were reported globally [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for global measures to control the spread of the pandemic. Several countries have recommended strict preventive measures, such as travel bans, lockdowns, quarantine and isolation of clustered cases, frequent hand washing, and wearing facemasks in public places. Governments of various countries, including the health officials in the U.S., are now imposing more intensive steps such as social distancing to prevent/discourage gatherings in public areas [2].

With the global spread of the COVID-19 pathogen, peoples’ online activities (i.e., Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, etc.) began to increase. This increasing trend of using social media could significantly influence individuals’ healthcare behavior. Several studies have shown peoples’ use of online media during the crisis and its impact on their attitudes and behaviors [3,4]. Social media can definitely play a key role in communicating up-to-date policies and regulations from health officials [5]. Therefore, analysis of the online data showing individuals’ behaviors and concerns about healthcare providers during COVID-19 offers unique opportunities to address public concerns and improve the quality of healthcare services [6]. Online users’ publicly available data on social media sites can be used to easily classify key concepts, sentiments, and issues that people worry about regarding the COVID-19 infection [4]. Analysis of online data can also complement conventional surveys and aid the development of efficient health interventions and policies at large [7].

Using natural language processing (NLP) to automatically mine topics and opinions from patient online reviews (PORs) has been a complicated task. Topic modeling is a statistical tool for uncovering abstract topics from a series of documents. Notably, latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) [8] is a probabilistic statistical model that taxonomically describes its components. Focused on the comparatively simple and vigorous bag-of-words explained as text, it does not take into account the order of words and sentences. The fundamental assumption of this model is a mixture of topic terms [8]. LDA points out those different themes involved in online reviews that may be linked to one of the topics. It has been extensively used to identify topics from unstructured data in different domains, particularly in healthcare [9,10]. Due to the extensive applicability of this topic modeling approach in the biomedical domain, several improvements were made to the standard LDA. Previous work has explained the potential extensions of LDA in the medical domain, with examples that include the extraction of hidden information from electronic health records [11], different patterns mining relating to patients’ health status [12], consumer health expressions mining [13], and analysis of user-generated content (UGC) [14].

While prior research has improved the LDA model for analyzing UGC, there has been little research using it during the crisis because it is difficult to model the semantic interpretation of UGC posted during the crisis. Furthermore, the diversified distribution of topics makes it difficult to extract topics from particular documents. Researchers have conducted several studies on different pandemic crises, such as COVID-19 [3], Zika [15], and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) [16], using different text mining techniques. For example, a study by Liu et al. [4] used a topic modeling approach to extract different topics from Chinese social media. Abd-Alrazaq et al. [5] used LDA algorithms to detect key topics posted by Twitter users related to the Coronavirus infection. Using structural topic modeling and network analysis, Jo et al. [2] also investigated web-based health communication trends. They analyzed what motivated peoples’ anxiety in the early stages of COVID-19 in South Korea. Stokes et al. [17] used LDA to identify people’s preferences and concerns regarding COVID-19 in an online discussion forum. Kleinberg et al. [18] used topic modeling to predict peoples’ emotional behaviors during the COVID-19 crisis in the United Kingdom. Using topic modeling, Ordun et al. [19] identified different topics from COVID-19 tweets. Cho et al. [20] also used LDA to identify the patient safety concerns about healthcare stakeholders during the pandemic period. Several other studies qualitatively analyzed Twitter data during the COVID-19 period in different countries [[21], [22], [23]]. Researchers have also studied prediction [6], public perceptions and behaviors [7,24,3], and emerging research trends [25]. In summary, few studies have focused on improved LDA for analyzing UGC during crises. However, earlier investigations on the improvement of LDA have overlooked the semantic framework, which has strict limitations. The semantics in any particular natural language sentence are named sentence importance, and the semantic unit communicates significance in the context of the sentence. The natural paragraph has unique semantic and pragmatic roles as the organizational structure of the document. Moreover, the content in the natural paragraph overwhelmingly concentrates on a single topic. Previous studies disclosed that semantically analyzing UGC has achieved good results [19,17,26].

In this age of digitization, many healthcare facilities face the need to quickly upgrade their information technology systems to address contemporary challenges regarding patients’ concerns during the COVID-19 crisis. Social media analytic tools constantly monitor changing public sentiments, assess public desires and concerns, and forecast real-time disease patterns [24]. Although previous studies have explored crisis-related public sentiments and discussion topics [16,18], recent investigations have shown that PORs, including specific types of emotions reflected in those reviews, play a crucial part in patients’ decision-making process [24,3]. If the opinions expressed in a review are a combination of discrete positive and negative emotions regarding the evaluation of products or services, the assessment of the products or services becomes perfect. Therefore, the authors intend to provide real insights into the impact of public health communications and assume that specific emotions appearing in the PRWs and their underlying PORs are extremely important during the current COVID-19 crisis.

Learning topic dynamics and sentiment trends from a broad corpus have gained more interest in data mining, as an extensive amount of user feedback is accessible on the Internet. However, little is known about the emerging and fading trends in doctor-patient interactions during the early wave of the current COVID-19 crisis in the U.S. Researchers need to investigate different topic dynamics and sentiment trends in PRWs regarding patients’ experiences with doctors during the COVID-19 outbreak. To cope with this challenge, an improved topic coherence-based LDA (TCLDA) model and sentiment analytic technologies were implemented. Using a mixed-methods approach (TCLDA model, manual annotation, and sentiment analytic technology), this study aims to implicitly discover the domain-specific topics and discrete emotions from a large collection of PORs crawled from three publicly available PRWs in the U.S. The data sources used in the study are different from the general social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Weibo used in previous studies. The data from the PRWs (RateMDs.com, HealthGrades.com, and Vitals.com) provide information about the dynamics of these topics and sentiments to gain insight into the healthcare system during the pandemic. It is important to understand which aspects of doctor-patient interactions are rising or falling in popularity. With the implementation of the improved LDA model, several documents are assigned to the topics, and each topic is a collection of several keywords. The PORs are evaluated using patients’ quality of treatment and other aspects through these topic distributions. Given the large body of studies that apply the same research methods to identify related topics and sentiments from social media, this will help researchers to argue the significance of these topics and sentiment trends from the PORs data. Studying shifts in public opinions using the extracted topics and four fundamental discrete emotions will expose how public perceptions concerning the crisis have shifted over time.

2. Material and methods

The authors’ context is three leading, publicly available, online health rating platforms in the U.S. (RateMDs, HealthGrades, and Vitals). These platforms provide an ideal setting and ample data to explore different topics and sentiment trends regarding patients’ healthcare experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A Python-based web crawler was developed to extract PORs from these platforms. This study’s final dataset includes 55,612 patient reviews of 3430 doctors collected from March 1, 2020 to June 27, 2020. Ten types of disease specialties were chosen, including five high-rank and five low-rank diseases, based on the mortality rate and disease rank from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [27].

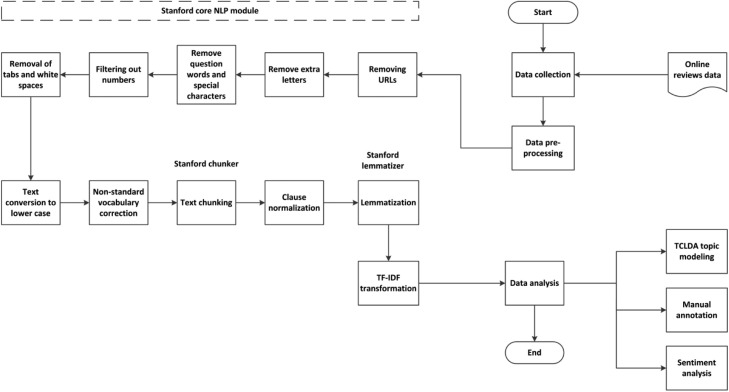

Levels of need and motivation modify a person’s behavior. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory [28], low-level needs and requirements, for instance, physiological requirements and action should be fulfilled before high-level needs. Once basic consumer needs are met, they move to a higher level of specifications. In healthcare, the patients’ needs and motivation also shift across different disease types [29]. Some physicians must meet low-level needs for low-disease severity, and others must satisfy high-level needs for high-disease severity. Patients’ traits significantly influence their degree of satisfaction with the quality of care. Therefore, the rationale behind splitting the dataset into high-rank vs. low-rank disease categories was because patients suffering from high-rank diseases (serious diseases) tend to be more sensitive to the physician quality of care and hence expect different levels of service than those suffering from low-rank diseases (mild diseases). The varying disease conditions significantly affect patients’ health consultation decisions and opinions toward a healthcare provider [29,30]. A data split was performed to identify high-rank (32,441of total 55,612 reviews) and low-rank (23,171 of total 55,612 reviews) disease categories. The overall proposed methodology is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Overall proposed methodology.

2.1. Data analysis

After data collection, several pre-processing steps were performed to clean raw data using Stanford NLP tools. 1) Remove URLs, short words (with less than 3 characters), and stop words (a, an, the, etc.) since they do not provide valuable information for opinion mining. Stop words can be identified by recognizing words that frequently appear in various documents. For example, represent each word as wi (i = 1… M), in document d. For each word wi, calculate its frequency in document d denoted as fi. Arrange them in descending order and remove the top 20 % of words. 2) Remove additional letters from words; for instance, the word “Awesome” was substituted for “Awesomeeee.” 3) Delete question words (who, why, whom, etc.) and special characters ($, #, &, etc.) as both do not influence the study analysis. 4) To optimize the review content, delete digits from the dataset. 5) All white spaces and tabs were deleted. 6) All reviews were processed to lower case. 7) Non-standard vocabulary (spelling correction, etc.) was corrected. 8) Stanford Chunker was employed to chunk input reviews. 9) To normalize verb chunks and noun chunks, clause normalization was performed. 10) All the words in the corpus were lemmatized to their base form using the WordNetLemmatizer function and WordNet Python natural language toolkit (NLTK) (http://nltk.org). A step-wise data pre-processing is shown in Fig. 1.

A matrix for document terms was created with the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF–IDF). TF–IDF is used to highlight the significance of a word in a document [31]. To extract an appropriate LDA topic number, a mixed-methods investigation was performed, including an improved LDA (i.e., TCLDA).

Topic modeling (LDA) is a complex text-mining approach, perfect for this study’s research objective, to understand patients’ voices by identifying emerging and fading topics on the RateMDs, HealthGrades, and Vitals rating platforms. However, the drawback of conventional LDA is that it does not take into account any of the semantic characteristics embedded within the document content. Rather than using conventional LDA to model topics at the document level, it is preferable to refine the document into various semantic topic units, which is especially appropriate for modeling text reviews. This study emphasized the LDA model [8] and its improved version (i.e., TCLDA), which has become a benchmark model for unsupervised topic identification in a text document. TCLDA was used to analyze PORs by semantically identifying different topic trends on the three different U.S.-based platforms. The proposed version is an improvement over the traditional LDA models, which explicitly analyzed the patients’ posted comments [10,17].

Let α and β reflect the Dirichlet’s parameter prior to the per-document topic distribution and per-topic word distribution, respectively. θ ( d ) denotes the topic distribution for document d (e.g., a POR). ϕ (z) indicates the word representation for topic z. w is the word, and D stands for the number of documents, wNd represents the number of words in a document d, and T signifies the number of topics. The LDA corpus-generation model assumes the following mechanism for a document d=(w 1,….wNd) including Nd words from a dictionary involving V different terms, where wi is the ith word for all i = 1,. . ., Nd [32]. The following are the three stages of the LDA model:

-

1)

Choose ϕ (z) ∼ Dir (β).

-

2)

Choose θ (d)∼ Dir (α).

-

3)

For each of the Nd words:

-

4)

Choose a topic z ∼ Multinomial (θ (d)).

-

5)

Choose a word wi∼ Multinomial topic (z): P(wi | z; ϕ (z)).

The topics in the review text corpus can be explored by Gibbs sampling methods [33] that assign values to the unknown parameters θ and ϕ.

The coherence score was used to determine the collection of the appropriate number of topics [34]. Topic coherence estimates the uniformity of a particular topic by calculating the semantic similarity between high-score words in a topic that improve the semantic understanding of the topic [35]. For instance, words are denoted as vectors in vector space modeling, and cosine similarity is calculated between word vectors. The coherence is the average of cosine similarities [36].The coherence model from the Gensim Python library [37] was used to compute the coherence value. The coherence score increases significantly up to 15 topics, becomes stable at 20 topics, and then trends downward after stabilization (see Fig. 2 ). The lines reflect the mean coherence values of three runs in which the number of topics ranged from 1 to 30. It has been noticed that it is difficult for researchers to interpret the results if only statistical methods are applied [38]. Therefore, statistical methods and manual annotations were integrated and 15 topics were selected from each disease category using Python 3.6 and LDAvis tool (pyLDAvis) [39] (the hyper-parameter and value of the mixture weight λ is the probability of a word being generated by the latent feature topic-to word model = 0 ≤ λ ≤ 1 and fix 30 topics with their keywords). Labels were assigned to the corresponding keywords to elaborate the topics. The visualization of 30 topics was represented as circles in Section 3.2. The blue color reflects the topics, while the red color represents highlighting a particular topic (Topic 1 in this study). The size of the circle represents the percentage of tokens included in the corpus of the topic. These circles overlapped, and their centers are defined based on the computed topics distance [39]. LDAvis leverages the R language [40], and in particular, the shiny package [41], not just its browser-interaction functionality with D3 [42], but allows users to quickly alter the topical distance calculation and multidimensional scaling algorithm to construct a global topic view.

Fig. 2.

Coherence score against each topic number.

2.2. Dynamics of topics in physician-rating websites

The authors’ proposed method extracts a set of topics from PORs. To gain more insight into these topics, it is important to find the dynamics of these topics across different disease categories during the early wave of the COVID-19 outbreak, more specifically, which topics of discussion are emerging (growing) or fading (declining) in popularity. Following the previous topic trends identification studies [43,44], a topic is categorized as an emerging topic if it is a heavily (popular) discussed topic over time. Moreover, emerging features, such as terms or phrases, are typically used to detect emerging topics. An emerging topic should therefore have a high degree of novelty and a low degree of fading. In PRWs, the topic typically exhibits a life cycle that arises at some point in time and builds to a climax while attracting more and more interest, leans towards fading, and eventually disappears or restarts. In contrast, a topic demonstrates a fading trend (less popular) if it was marginal earlier discussion but attracts less attention [43]. In general, a fading trend has less novelty value. Fig. 3 illustrates the topic life cycle.

Fig. 3.

Conceptual diagram of topic life cycle and two topic evolution processes.

Thus, topics of interest for patients can be analyzed based on the probability model [43]. In this research, the authors propose a novel probability and a fading probability for the collective identification of emerging and fading topics from latent topics created by a topic model. The emerging topics and fading topics were calculated along with the probability of each topic within each document, and the total probability was recorded. Topic trends were produced by adding the probability of topics for a given document and then dividing them by the total number of documents in a corpus. A higher topic strength denotes increasing popularity as an emerging topic, while a lower topic strength represents decreasing popularity.

The value of θ can be obtained from the prior discussion. The meaning of θ in a matrix for document terms is presented below:

Hence, column entries represent topics and row entries represent documents. The value of θD,k indicates the probability of topic k given document D. The emerging and fading topics are defined based on topic strength (i.e., aggregate probability of topic k in document D) as given below:

| (1) |

Where denotes the topic strength of topic k and D represents the number of documents in the corpus.

As emerging and fading topics are based on temporal changes of topics, the dynamics of the research topics (i.e., emerging and fading topics) may be learnt using the following method:

-

1)

Classify documents by time. The authors use week as the time unit in this paper. Suppose the document collection for week Wi is Ci.

-

2)

The probability θkdi of each ith-document allocated to topic k, according to θ, is obtained.

-

3)

Keep the topic strength as follows:

| (2) |

-

4)

With the graphical illustration of the kth topic strength in week Wi, the dynamics of the topic k can be seen as emerging and fading topics.

The entire process of the TCLDA algorithm for topic extraction and mining topic dynamics is defined in Appendix A.

2.3. Human annotation and testing procedure

While efforts have been made to label the topics automatically, they are imprecise and do not ensure coherence [45]. To produce meaningful topic names, each topic was labeled manually, despite the fact that it was more labor-intensive. After several rounds of discussion, topics were named following the top 10 keywords and the annotators’ consensus decisions. The detailed annotation and testing process is as follows.

In order to conduct an extrinsic assessment, the LDA-based topics were compared with the ground truth (actual topic). The authors’ trained LDA used the PORs in the corpus (80 % training data and 20 % testing data) to label certain reviews. The ground truth was defined by using human annotators, who manually categorized reviews from the corpus (1500 reviews in total) into a topic. The annotators were experts in the information systems domain who were familiar with the list of identified topics. They were asked to categorize each review into the list of topics assigned to them. Since three annotators coded each review, the disagreements between the three coders were addressed until all disputes had been resolved. The inter-rater agreement between any two coders was calculated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, ranging from 0.70 to 0.84, indicating a good agreement. Therefore, the manually annotated reviews that all of the annotators agreed upon were considered the ground truth. The underlying qualitative approach of manual annotation was based on a wide variety of in-depth interpretations from human coders, which facilitated inductive, exploratory research, and the implications of theoretical methods [46]. To assess performance in a quantitative manner, topic-wise accuracy, precision, and F1 measures were calculated, which are the most common assessment metrics used in text classification. After checking TCLDA’s output on training and testing data, the trained model was used to label each review to its most probable topic.

2.4. PORs overall sentiment dynamics

Sentiment analysis is a computational and NLP-based method that focused on the analysis of people’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in a given text [47], and it is an important technique in social media analytics research. In this study, the authors used a machine-learning model to predict the public emotional response in PORs. This model categorized each POR into four discrete emotions in Plutchik’s wheel of emotions [48]. For a given POR, the model returned one emotion from the group of four discrete emotions, specifically, fear, anger, sadness, or joy. Following Plutchik’s wheel of emotions [48], fear-anger and sadness-joy are viewed as opposite emotions. Fear is an awful feeling that usually triggers threats or uncertainties created by conditions, whereas anger arises from ambiguities caused by others. Sadness is seen as a negative emotion usually encountered after traumatic situations beyond one’s control, and joy is a happy feeling resulting from enjoyable events that are considered assured and under control [49].

This research shows the emotional reactions of PRWs users toward the pandemic. Trends for the four discrete emotions and descriptions underlying these emotions were analyzed. The emotional connotations behind the PORs were analyzed using a sentiment analytic technology called CrystalFeel, which offered proven accuracy in recent work [50]. CrystalFeel is a machine learning technique that uses parts-of-speech, n-grams, word embedding, multiple affective lexicons, and original in-house built EI Lexicons to predict the degree of strength associated with fear, anger, sadness, and joy in the PORs. For the approach, the authors used the CrystalFeel algorithm’s emotional strength scores (quantitative values) and transformed them into labels (qualitative values) for a more precise understanding, where “fear,” “anger,” “sadness,” and “joy,” were labeled as each POR’s dominant emotion (see Algorithm 1). Pearson correlations (r) between emotions and weekly time periods were performed to statistically show emotional patterns over time.

Algorithm 1: Mining sentiment trends during the early wave of the pandemic

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Fig. 4 shows the relationship between the number of new confirmed COVID-19 cases, deaths, and online reviews during the study period. Statistics regarding the increasing number of deaths and confirmed cases were collected from the WHO [1]. All three measures were negligible in the first week of the study period (i.e., March 7, 2020) because the virus started to spread widely in mid-March. Therefore, there was a sudden increase in these measures since the third week of the study period (i.e., March 15, 2020) because there was no lockdown before that date, and people were less careful about social distancing and wearing masks in public. However, these measures were dropped in May (week 10) due to the strict lockdown and travel bans. During the George Floyd protests in June 2020 (week 14 and onwards), these three measures surged again following Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police. An estimated 15–26 million people participated in the “2020 Black Lives Matter” protests in the U.S., making Black Lives Matter one of the largest movements in U.S. history. During the protest, people did not care about social distancing and wearing masks in public places, and the number of infected cases increased sharply. As a result, the discussion on PRWs (PORs posting) regarding different aspects of care increased significantly during this phase of the COVID-19 crisis.

Fig. 4.

Number of new cases, deaths, and online reviews during the study period.

3.2. COVID-19-related topics, themes, and their dynamics

The COVID-19 pandemic has received considerable global attention. Topic modeling provides insights into what people discussed more or less frequently regarding their treatment experience with doctors and other aspects during the COVID-19 crisis.

Fig. 5 presents the topic model design, representing 30 different topics across high-rank and low-rank disease categories as circles. The region of circles shows the cumulative frequency and each topic’s overall prevalence. The distance between the two topics is shown in the vector space model. The first principal component (PC1) is drawn at the transverse axis, while the second component (PC2) is delineated on the longitudinal axis.

Fig. 5.

Distance map between topics (high-rank and low-rank diseases) PC: Principal component.

Fig. 6 is an example that presents the top ten words for topic 1, which includes the largest proportion of all topics. Topic 1 was chosen, and the system visualized the distribution of word frequencies compared to the entire corpus. Each bar displays the total frequency of each keyword and the approximate frequency in topic 1. In topic 1, the PORs mainly discussed doctor competence regarding infection diagnosis, and they mentioned virus symptoms, professional, experienced, and skills most frequently. Then, the topic label was assigned according to the content. This approach has been well demonstrated by previous studies [51,4].

Fig. 6.

Top 10 most relevant terms for Topic 1 in the high-rank disease category (12.9 % of tokens).

Table 1 shows the top keywords for 15 topics across high-rank diseases. These keywords were based on the probability distribution against each topic’s keywords. This process is reported in previous litera- ture [52]. There were a total of 11 emerging topics and 4 fading topics across high-rank diseases. Considering emerging topics, doctor competence regarding infection diagnosis, treatment/operational process and research, disease diagnosis and prevention, friendly staff, emergency services and trauma center, and hospital cafeteria servicescape represented a total of 50.44 % (16,364/32,441reviews) of the high-rank disease corpus. These topics were mostly related to the treatment experience theme.

Table 1.

Emerging and fading topics in patient online reviews across high-rank diseases.

| Nature of topics | Topic number | Topic labels | Keywords (Probability) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging Topics | Topic #1 | Doctor competence regarding infection diagnosis | Virus symptoms (.362), professional (.130), experienced (.094), skills (.088), intelligent (.074), honest (.061), symptoms (.04), breath shortness (.045), answering questions (.055), dizziness (.051). |

| Topic #2 | Treatment/ operational process and research | Infection (.280), treatment (.190), diagnosis (.091), isolation (.087), medication (.071), spread (.065), changed the life (.061), medical procedures (.059), COVID-19 vaccine (.055), laboratory research (.041). | |

| Topic #3 | Emotions toward epidemic | Test shortage (.555), racist jokes (.201), making fun (.103), compensation (.076), loved one (.032), lost job (.019), afraid (.011), great job (.009), stay safe (.008), new wave (0.006). | |

| Topic #4 | Prevention and control procedures | Fight against the outbreak (.279), meeting (.145), fight (.087), work regulation (.081), community (.075), help (.073), opportunity (.071), service (.067), accurate diagnosis (.063), serious and responsible (.059). | |

| Topic #5 | Mental health | Rude (.37), depressed (.105), long (.087), wait (.079), mental (.071), damage (.070), nationwide (.068), less time (.066), society (.063), long (.021). | |

| Topic #6 | Disease diagnosis and prevention | Cough (.189), bowel (.185), blood (.187), spread (.061), control (.059), pandemic (.058), official (.055), CDC (.051), warn (.048), report (.035). | |

| Topic #7 | Vaccine development | Problem diagnosis (.432), clinical trials (.106), phase 3 (.071), recovery (.069), immunity (.066), side effects (.065), policy (.063), infection (.045), symptoms (.044), dose-escalation (.039). | |

| Topic #8 | Friendly staff | Helpful (.378), friendly (.121), offer sanitizer (.091), wonderful (.089), social distance (.081), bedside manner (.075), frontline (.056), soap (.053), professional staff (.031), great staff (.025). | |

| Topic #9 | Emergency services and trauma center | 24 h (.255), quarantine (.125), ventilator (.088), pain reduction (.085), outbreak (.081), surgery (.078), reduced strain (.075), trauma (.073), special facilities (.071), specialized equipment (.069). | |

| Topic #10 | Hospital cafeteria servicescape | Hygienic (.519), clean (.068), clean table (.061), delicious food (.058), covered (.055), filter (.053), water (.050), quick service (.048), fresh food (.045), comfortable environment (.043). | |

| Topic #11 | Sense of pandemic | Deaths (.211), number (.163), rate (.161), severity cases (.091), new (.085), risk (.079), mortality (.068), worse (.066), feel (.041), confirmed (.035). | |

| Fading Topics |

Topic #12 | Panic buying | Purchase (.449), product (.085), sold out (.081), toilet (.080), store (.077), company (.076), factory (.075), business (.035), sell (.031), crowd (.011). |

| Topic #13 | Communication (listen and explain) | Bad (.375), problem (.109), compare (.098), uncomfortable (.091), communication (.085), impatience (.071), worry (.065), poor explanation (.050), nervous (.045), unhappy (.011). | |

| Topic #14 | Appointment process | Registration (.594), wait (.089), closed (.085), queue (.065), online system failure (.045), system performance (.041), cancel (.035), testing procedure (.021), bad (.015), long (.010). | |

| Topic #15 | Doctor value | Recommend (.456), highly recommend (.101), kind caring (.080), excellent doctor (.075), great doctor (.071), love dr (.065), God (.055), trust (.051), pleased (.031), impressed (.015). |

Regarding emerging topics, topics such as prevention and control procedures and vaccine development represented a total of 26.01 % (8,441/32,441reviews) of the high-rank disease corpus. These topics reflected the policy implementation regarding the epidemic control measures theme. It is critical for health professionals and policymakers to interact with people utilizing Internet media during the pandemic; therefore, the executives of key management agencies, medical facilities, and methods of community regulation were also emphasized in these topics. Active medical strategies could be used to disseminate optimistic and enthusiastic predictions that might eradicate needless patient fears and ensure trust in the country’s health officials to control the virus. Two other topics, emotions toward the epidemic and the sense of the pandemic, represented a total of 10.56 % (3426/32,441reviews) of the high-rank disease corpus. These topics indicated the individuals’ attitudes toward the pandemic. Finally, the topic related to mental health represented a total of 4.56 % (1479/32,441reviews) of the high-rank disease corpus. Previous research found that both medical workers and citizens under quarantine had elevated mental health issues [53] in earlier pandemics. Such investigations can enable readers to re-center this easily overlooked domain, and therefore early intrusion can be made based on this emerging sociological development.

In contrast, fading topics deal with panic buying and daily life impact and represented a total of 2.21 % (718/32,441 reviews) of the high-rank disease corpus. These details showed that the medical and social sectors were adversely affected by the COVID-19 crisis. It is also a big challenge for public health that needs worldwide collaborations. It was also observed that across high-rank diseases, topics such as communication (listen and explain), appointment process, and doctor value were less discussed on the three platforms, representing a total of 6.76 % (2194/32,441 reviews) of the high-rank disease corpus. These three topics lie under the common theme of treatment process and bedside manner. The topic related to the appointment process included keywords representing the secondary impact of COVID, such as longer waiting time and closure/cancellation of a doctor’s appointment.

Table 2 presents the 11 emerging topics and 4 fading topics across low-rank diseases. Emerging topics that were converged under the treatment process and experience theme included topics such as convenient hospital location, uncomfortable environment, physician knowledge and confidence, treatment/operational process, disease diagnosis, unfriendly and non-cooperative staff, medical examination for COVID-19, and treatment cost, representing a total of 59.06 % (13687/23,171) of the low-rank disease corpus. The findings showed that PRWs transmitted this sort of health information by concentrating on identifying suspect cases and medication that could cure the patient and spread the virus. The topic related to treatment cost indicated that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has greatly influenced peoples’ economic conditions.

Table 2.

Emerging and fading topics in patient online reviews across low-rank diseases.

| Nature of topics | Topic number | Topic labels | Keywords (Probability) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging Topics | Topic #1 | Convenient hospital location | Good location (.754), accessible (.055), transport (.051), perfect (.045), convenient (.031), ease (.028), center (.025), travel restrictions (.021), available (.010), hospital location (.005). |

| Topic #2 | Uncomfortable environment | Noisy environment (.697), dirty rooms (.103), rush (.045), hot (.032), corridors (.030), sitting area (.028), disinfection (.025), loud (.023), cry (.010), messy wards (.007). | |

| Topic #3 | Physician knowledge and confidence | Hope (.411), noble (.123), trust (.092), confidence (.081), better (.075), best (.069), think (.061), assurance (.041), happy (.032), confirmed cases (.015). | |

| Topic #4 | Treatment/ operational process | Great treated (.432), diagnosis (.152), medication (.131), diagnosed with ease (.061), blood test (.058), antibiotics (.055), COVID-test (.041), mask (.032), hospitalization (.023), laboratory report (.015). | |

| Topic #5 | COVID-19 deaths, fear, and stress | Horror (.687), pain (.125), serious (.036), danger (.033), diarrhea (.027), blood (.024), kill (.021), died (.018), tension (.016), strain (.013). | |

| Topic #6 | Confirmed cases | Confirmed (.487), patient (.156), pneumonia (.092), novel (.088), infection (.071), new type (.066), novel corona virus (.031), deadly (.006), infection (.003). | |

| Topic #7 | Disease diagnosis | Treatment (.369), blood sugar (.145), blood pressure (.123), control (.111), insulin (.054), vaccine (.051), drug (.043), stable (.042), frequent urination (.033), weight loss (.029). | |

| Topic #8 | Public health measures | Hands (.210), wash (.198), soap (.101), away (.095), n95 (.091), face (.085), mask (.081), sanitizer (.035), gloves (.018), safe (.008). | |

| Topic #9 | Unfriendly and non-cooperative staff | Staff (.256), unfriendly (.138), rude (.125), front desk staff (.121), call (.091), unhelpful (.085), ignore (.081), loud (.076), twice (.051), bother (.031). | |

| Topic #10 | Medical examination for COVID-19 | Operation (.32), X-ray (.191), medical examination (.082), n95 (.080), clear report (.075), prescription (.073), protection (.071), laboratory report (.063), reexamine (.051), medical supply (.045), pneumonia (.041), blood test (.031). | |

| Topic #11 | Treatment cost | Expenses (.628), money (.195), registration fee (.045), waste money (.031), expensive (.026), travel bans (.023), affordability (.021), difference (.016), insurance (.012), credit (.003). | |

| Fading Topics |

Topic #12 | Detection at public transportation, passenger, travel bans and warnings | Parking (.329), closed (.113), cancel (.101), travel (.038), signs (.035), safe (.031), surveillance (.019), work (.013), university (.004), need (.002). |

| Topic #13 | Materials supplies and society support during COVID-19 | Supply shortage (.44), donation (.121), manufacture (.119), market (.109), enterprise (.053), production (.045), recover (.041), medicine (.035), control (.031), injection (.006). | |

| Topic #14 | Patient visit process | Takes time (.615), answer questions (.156), explain (.052), listen (.041), attentive (.035), fear (.031), wash (.025), friendly (0.021), cooperative (.019), stress about COVID-19 (.005). | |

| Topic #15 | Medical ethics (relational conduct) | Knowledgeable (.271), great (.145), care (.121), family (.109), manner (.085), wonderful (.081), feel (.077), recommend (.075), hand wash (.021), time (.015). |

The topics under the theme for awareness and COVID-19 control measures included confirmed cases and public health measures and represented 25.47 % (5903/23,171) of the low-rank disease corpus. The COVID-19 deaths, fear, and stress topic represented a total of 10.65 % (2469/23,171) of the low-rank disease corpus. This suggests that PRWs have assisted public health utility because of their evolving rates, and the number of cases gives consumers intuitive feelings about the pace, momentum, and risk of viral spread. It also allows users to remain alert to viral transmission, avoid the virus, and alter their day-to-day activities.

For fading topics, the theme healthcare provider attitude toward patients during pandemic included two topics, patient visit process and medical ethics (relational conduct), which represented a total of 2.66 % (617/23,171) of the low-rank disease corpus. The other two individual topics were the detection at public transportation, passenger, travel bans and warnings and materials supplies and society support during COVID-19, which represented a total of 1.18 % (273/23,171) and 0.98 % (227/23,171) of the low-rank disease corpus, respectively. To deal with COVID-19, the U.S. government has taken steps on the basis of these principles. Detecting viral infections in public conveyance networks provoked great public concern. Since the outbreak was sudden and the transmission is rapid, people in affected areas required medical materials and other necessities. Hence, public agencies should maintain material supplies and raise donations and funding to protect people from the pathogen.

As shown in Table 3 , the high values of topic-wise accuracy, precision, and F1 scores suggests that a majority of the reviews can be correctly labeled on their most probable topic by using the TCLDA model.

Table 3.

Topic-wise classification performance.

| Topics for high-rank diseases | A | P | F1 | Topics for low-rank diseases | A | P | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor competence regarding infection diagnosis | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.81 | Convenient hospital location | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| Treatment/operational process and research | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.75 | Uncomfortable environment | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| Emotions toward epidemic | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.73 | Physician knowledge and confidence | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.77 |

| Prevention and control procedures | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.85 | Treatment/operational process | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| Mental health | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.75 | COVID-19 deaths, fear, and stress | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Disease diagnosis and prevention | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.81 | Confirmed cases | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Vaccine development | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.75 | Disease diagnosis | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.75 |

| Friendly staff | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | Public health measures | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| Emergency services and trauma center | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.75 | Unfriendly and non-cooperative staff | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.76 |

| Hospital cafeteria servicescape | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.75 | Medical examination for COVID-19 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

| Sense of pandemic | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.72 | Treatment cost | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.69 |

| Panic buying and daily life impact | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.71 | Detection at public transportation, passenger, travel bans and warnings | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.72 |

| Communication (listen and explain) | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.68 | Patient visit process | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| Appointment process | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.69 | Medical ethics (relational conduct) | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| Doctor value | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.69 | Materials supplies and society support during COVID-19 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.71 |

Note. A = Accuracy, P = Precision, F1 = F1 measures.

As described in Section 2.2, the authors used the probability model and topic strength-based approach to the PORs dataset to examine the dynamics of the topics learned from the study’s method from March 1, 2020 to June 27, 2020. Fig. 7, Fig. 8 portray the dynamics of 30 topics (15 topics within each disease category having 10 most probable keywords in those topics as shown in Table 1, Table 2). For the high-rank disease category in Fig. 7, it can be observed that most of the topics are comparatively steady. For example, topic 6 (disease diagnosis and prevention), topic 7 (vaccine development), topic 8 (friendly staff), topic 9 (emergency services and trauma center), topic 10 (hospital cafeteria servicescape), topic 11 (sense of pandemic) and topic 15 (doctor value). Some topics indicated increasing trends as emerging topics, including topic 1 (doctor competence regarding infection diagnosis), topic 2 (treatment/operational process and research), topic 3 (emotions toward epidemic), topic 4 (prevention and control procedures), and topic 5 (mental health). Other topics, such as topic 12 (panic buying), topic 13 (communication (listen and explain)), and topic 14 (appointment process), reflected decreasing trends as fading topics.

Fig. 7.

The dynamics of 15 topics across high-rank diseases.

Fig. 8.

The dynamics of 15 topics across low-rank diseases.

In contrast, for the low-rank disease category in Fig. 8, topics such as topic 1 (convenient hospital location), topic 2 (uncomfortable environment), topic 3 (physician knowledge and confidence), topic 4 (treatment/operational process), and topic 5 (COVID-19 deaths, fear, and stress) represented increasing trends as emerging topics. Other topics, such as topic 12 (detection at public transportation, passenger, travel bans and warnings) and topic 13 (materials supplies and society support during COVID-19), reflected decreasing trends as fading topics. Moreover, topic 6 (confirmed cases), topic 7 (disease diagnosis), topic 8 (public health measures), topic 9 (unfriendly and non-cooperative staff), topic 10 (medical examination for COVID-19), topic 11 (treatment cost), topic 14 (patient visit process), and topic 15 (medical ethics (relational conduct)) were relatively stable.

The main difference between the topic dynamics across high-rank and low-rank disease categories might be their connection with mortality. As the disease-rank is linked to physical factors (health condition) and physiological factors (pain and worry), a patient suffering from a high-rank disease spends more effort to get high-quality services from a competent doctor [29]. For instance, a patient with heart disease feels more pain and anxiety than a patient who just has influenza or a cold. As a result, they are keen on higher-quality medical services to deal effectively with physical and physiological factors [30]. As such, most emerging topics in the high-rank disease category focused on technical aspects of care, whereas most emerging topics in the low-rank disease category focused on the treatment process during COVID-19. However, fading topics for both disease categories concentrated on a different aspect of care by showing less interest in these aspects on the three PRWs.

Overall, it is interesting to see that the similarities and differences among emerging and fading topics from both disease categories are quite close to the reality of the U.S. healthcare system, which indicates that the online feedback does reflect real patient experience and genuineness of the healthcare system. Therefore, the methodology used in this study can assist healthcare providers and hospital officials in better understanding and improving the healthcare service delivery quality by mining patients’ voices regarding a healthcare system.

3.3. Overall sentiment dynamics

PORs disclose information about individuals’ perceptions and emotions. Fig. 9 shows individuals’ emotional reaction trends to the COVID-19 crisis. It reflected the overall weekly sentiment distribution of PORs in PRWs during the study period. The findings indicated a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) value of 0.821 between the inferred sentiment strength with out-of-training sample of human annotations and of 0.711, 0.740, 0.703, and 0.716 on emotional strength in forecasting fear, anger, sadness, and joy [50]. It can also be observed that fear (blue line in Fig. 9) was consistently the prevailing emotion over time. Fear dominated at the beginning of March when the first case of the virus appeared in the U.S. The spread of the virus and its uncertain nature may have been synonymous with fear, causing uncertainty about strict government measures and spread, indicated by words such as “confirmed case,” “wave,” and “outbreak.” However, as the pandemic intensified, the narratives showed fear of medical and food supply shortages, articulated with the terms “supply shortage” and “sold out.”

Fig. 9.

Overall emotion trends during the early wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The status of fear fell to less than one-quarter of weekly PORs from early to mid-April as the crisis developed (r69= –0.89; P < .001). On the other hand, PORs exhibiting anger (the second most dominant emotion represented as a brown line in Fig. 9) gradually increased from the beginning to the end of March, peaking at 27 % on March 12, the day after the WHO Pandemic Declaration. Since then, the PORs with anger decreased marginally but persisted at a very high level (r71 = 0.72; P < .001). PORs exhibiting fear and anger dramatically decreased following the declaration of the pandemic, while PORs displaying sadness (the third dominant emotion represented as green line in Fig. 9) were comparatively lower than those of other emotions but doubled after the WHO announcement (r69 = 0.85; P < .001). The most frequent keywords regarding anger included “racist jokes” and “making fun.” Anger then moved to the conversation about the exhaustion of loneliness (sadness) that could arise because of social isolation and other factors indicated by keywords such as “quarantine,” “isolation,” “lost job,” and “deaths.” Likewise, PORs about joy (a less dominant emotion until March 31, represented as an orange line in Fig. 9), often reflecting a sense of pride, appreciation, hope, and satisfaction [50], also increased (r69 = 0.83; P < .001). People around the globe have also seen a parallel increase of a sense of joy, incorporating gratitude, optimism, and a desire for human resilience with words such as “friendly,” “great job,” “compensation,” and “happy.” However, there was a sudden increase in joy after April 1, 2020, as the U.S. Department of Labor announced the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program of $600 per week to be distributed to individuals collecting Unemployment Compensation.

3.4. Research strengths

There are several possible contributions of this research. First, the authors did not find any work regarding the most popular and least popular trends during the epidemic crisis [54,16]. This paper investigates different psychological reactions in PRWs as emerging and fading topics and sentiment trends regarding patients’ healthcare experiences. The findings help patients to improve perceptions, attitudes, and awareness of clinicians regarding different medical issues.

Previously, papers explicitly analyzed health-related text to mine patients’ opinions by applying the most commonly used topic modeling techniques (i.e., LDA) [5,20] and sentiment analysis approaches [47]. Generally speaking, this paper methodologically contributes to text mining techniques and offers a mixed-method approach (TCLDA model, manual labeling, and sentiment analysis tool) to more systematically and semantically analyzes domain-specific knowledge regarding COVID-19–related topics and sentiments from PORs across time. The authors assume that this will bring major technical advancement in the field of text mining.

In this study, PORs were mined across high-rank and low-rank diseases. Fear of the pandemic was especially dominant during the early wave of the crisis. The study findings agree with the results of other studies [55,24,3,56], which demonstrate that COVID-19 significantly affects the cognitive behavior of individuals. Opinion mining of the recent crisis-related content helps us to understand how the public feels and what they believe about pandemics. Various stakeholders have different opinions on the standards of treatment that are influenced by their perceptions and aspirations across various disease categories. The study results have implications for health officials regarding the need to take into account the well-being and mental health of the society and those dealing with mental illness [3]. The authors assume that the topic modeling and sentiment mining methodology used for text mining have great potential to obtain useful insights and clues from larger datasets.

3.5. Practical implications

The findings indicate that PORs represent an emerging online asset that closely resembles the real healthcare system of the U.S. As a result, PORs could assist healthcare providers to better understand patients’ voices in terms of anger and joy to improve the quality of care.

For practice, researchers have shown that, in fact, online crisis management activities increasingly become “synchronized and interlinked” [57] and that crisis response activities in reality and online are becoming increasingly “simultaneous and intertwined” [57]. Social networking sites offer a valuable forum for the public to freely communicate and disseminate information and awareness about public health [58]. Nevertheless, social networks can also be an influential tool, particularly during a public health crisis, to increase patient satisfaction and reduce frustration with healthcare services.

Moreover, five different emerging and fading topics (communication abilities, relational behavior, professional skills and expertise, personal qualities, availability and accessibility) point toward future areas of physician training and the quality-of-service evaluation. To advance understanding of these constructs, healthcare professionals should begin specifying the different aspects of patient satisfaction and dissatisfaction with doctors [13]. This allows for an improved capacity to identify and target these specific areas of satisfaction and dissatisfaction that warrant improvements in individual healthcare and address important, unmet needs. On the other hand, patients can take advantage of this publicly available online asset to choose a competent doctor who would provide the best medical services for their disease treatment.

Finally, the increasing negative emotions in the form of fear, anger, and sadness must be healed and offset by strategic communications regarding public health that aim to stabilize the psychological well-being of the people [2]. Suppose authorities fail to address public concerns efficiently. In that case, citizens could develop an increasing mistrust regarding handling of the virus that could lead to false information about the disease control and prevention measures taken by healthcare officials [4,5]. In addition, more efforts are required to formulate policies and globally develop disease diagnosis and surveillance systems through the analysis of PORs posted on PRWs. Stronger and more constructive involvement of the public on health social media is required. Governments and health officials can also “listen to patients’ voices” or monitor the PORs from the PRWs, particularly in a time of crisis, to help formulate policies and laws related to public health (e.g., social distancing and quarantine) and supply chains.

3.6. Limitations

This paper reveals some limitations. First, the findings of this study are based on the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic and are therefore limited by the relatively smaller sample size (n = 55,612). Given that text-mining methods are better able to perform with larger datasets, future research can continue data collection after the pandemic in order to capture more novel topics and themes. Second, although the three platforms used for the analysis are the most popular PRWs in the U.S., future research can also investigate these emerging and fading trends in other regions where death and recovery rates were faster than in the U.S., such as the United Kingdom, Russia, Brazil, and India. Third, currently, this study only takes the COVID-19 period as a dataset. A comparison of topics between pre−COVID and the current time would be interesting, considering questions like: “Are topics changing due to COVID-19?” “Are people more positive about their doctors?” “Are there COVID-related topics in PORs?”

Collecting and comparing reviews pre−COVID and during the COVID pandemic may be an interesting avenue for future research. Fourth, the time range adopted in this work was from March 1, 2020 to June 27, 2020. Future research could compare and expand the study to multiple years by performing longitudinal topic modeling, for example, the period of March to June during the years of 2018, 2019, and 2020. There might be significant differences in patient sentiments that can be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, this paper raised an exciting research question regarding the popularity of healthcare topics and sentiments on PRWs. The authors believe that patients’ attention may change due to the COVID-19. Hence, it is important for readers to know what topics and sentiments were important to patients before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors’ future research will address this issue.

4. Conclusion

The collection and analysis of PORs illustrates how U.S. patients express their views during the early period of the COVID-19 crisis. To the authors’ knowledge, this was the first study to implicitly mine different topic dynamics (i.e., emerging and fading topics) and sentiment trends (i.e., dominant and less dominant emotions) from PORs across different disease categories. A mixed-methods approach using implicit data analysis (i.e., TCLDA model, manual labeling, and sentiment analytic technology) was used to highlight 22 emerging topics and 8 fading topics as various semantic topic units across high-rank and low-rank diseases. Moreover, negative emotions were dominant during the early wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. In summary, the findings indicated that analysis of PORs using an automated text mining approach could provide exciting insights for patients regarding their opinions toward the quality of care and for practitioners to take several steps in improving the healthcare system.

Authors’ contribution

Dr. Adnan Muhammad Shah contributed to every part of this research. Prof. Xiangbin Yan was involved in planning and supervising the research. Dr. Qayyum and Dr. Jamal participated in the data acquisition, developing the algorithm and implementation phase. Dr. Rizwan Ali verified the analytical methods and outputs, helped with all the technical details, and proofread the manuscript. All authors have discussed and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Summary Points.

Already known

-

•

Analyzing online data showing individuals’ behaviors and concerns about healthcare providers during the COVID-19 crisis offers unique opportunities to address public concerns and improve the quality of healthcare services.

-

•

There is no systematic way to analyze the emerging and fading trends in doctor-patient interactions during the COVID-19 crisis in the U.S.

-

•

Researchers need to investigate different topic and sentiment dynamics in physician rating websites to classify the key healthcare concepts, dominant opinions, thoughts, and issues.

What we added

-

•

An improved topic modeling (TCLDA), manual annotation, and sentiment analytic technology were employed to implicitly discover topics and dominant emotions from a collection of patient online reviews.

-

•

With the implementation of the TCLDA model, several documents were assigned to some topics, and each topic included the collection of several keywords.

-

•

The authors discovered health-related topics as emerging and fading topics and dominant emotions across different disease categories during the early wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation, People’s Republic of China (No.71531013, 71729001).

Appendix A. An improved LDA topic model-based on topic coherence (TCLDA)

References

- 1.WHO . 2020. COVID-19 Dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/region/amro/country/us (Accessed 30 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jo W., Lee J., Park J., Kim Y. Online information exchange and anxiety spread in the early stage of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak in South Korea: structural topic model and network analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(6) doi: 10.2196/19455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue J., Chen J., et al. Public discourse and sentiment during the COVID 19 pandemic: using Latent Dirichlet Allocation for topic modeling on Twitter. PLoS One. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Q., Zheng Z., et al. Health communication through news media during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in China: digital topic modeling approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(4) doi: 10.2196/19118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abd-Alrazaq A., Alhuwail D., Househ M., Hamdi M., Shah Z. Top concerns of tweeters during the COVID-19 pandemic: infoveillance study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(4) doi: 10.2196/19016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh R.K., Rani M., et al. Prediction of the COVID-19 pandemic for the top 15 affected countries: advanced autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2) doi: 10.2196/19115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geldsetzer P. Use of rapid online surveys to assess people’s perceptions during infectious disease outbreaks: a cross-sectional survey on COVID-19. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(4) doi: 10.2196/18790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blei D.M., Ng A.Y., Jordan M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003;3:993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hao H., Zhang K. The voice of Chinese health consumers: a text mining approach to web-based physician reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18(5) doi: 10.2196/jmir.4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao H., Zhang K., Wang W., Gao G. A tale of two countries: international comparison of online doctor reviews between China and the United States. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017;99:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speier W., Ong M.K., Arnold C.W. Using phrases and document metadata to improve topic modeling of clinical reports. J. Biomed. Inform. 2016;61:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manek A.S., Kailash Pandey K., Shenoy P.D., Mohan M.C., Venugopal K.R. Classification of drugs reviews using W-LRSVM model. 2015 Annual IEEE India Conference (INDICON); IEEE, New Delhi, India; 2015. pp. 1–6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah A.M., Yan X., Tariq S., Ali M. What patients like or dislike in physicians: analyzing drivers of patient satisfaction and dissatisfaction using a digital topic modeling approach. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021;58(3):102516. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., Chen M., Huang D., Wu D., Li Y. iDoctor: Personalized and professionalized medical recommendations based on hybrid matrix factorization. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2017;66:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2015.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farhadloo M., Winneg K., Chan M.-P.S., Hall Jamieson K., Albarracin D. Associations of topics of discussion on twitter with survey measures of attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors related to Zika: probabilistic study in the United States. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018;4(1) doi: 10.2196/publichealth.8186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi S., Lee J., et al. Large-scale machine learning of media outlets for understanding public reactions to nation-wide viral infection outbreaks. Methods. 2017;129:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stokes D.C., Andy A., Guntuku S.C., Ungar L.H., Merchant R.M. Public priorities and concerns regarding COVID-19 in an online discussion forum: longitudinal topic modeling. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020;35(7):2244–2247. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05889-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleinberg B., van der Vegt I., Mozes M. Measuring emotions in the COVID-19 Real world worry dataset. Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on NLP for COVID-19 at ACL 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ordun C., Purushotham S., Raff E. 2020. Exploratory Analysis of Covid-19 Tweets Using Topic Modeling, UMAP, and DiGraphs.https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.03082.pdf arXiv preprint arXiv:200503082. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho I., Lee M., Kim Y. What are the main patient safety concerns of healthcare stakeholders: a mixed-method study of Web-based text. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020;140:104162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park H.W., Park S., Chong M. Conversations and medical news frames on twitter: infodemiological study on COVID-19 in South Korea. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(5) doi: 10.2196/18897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen E., Lerman K., Ferrara E. Tracking social media discourse about the COVID-19 pandemic: development of a public coronavirus twitter data set. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2) doi: 10.2196/19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang C., Xu X., et al. Mining the characteristics of COVID-19 patients in China: analysis of social media posts. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(5) doi: 10.2196/19087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lwin M.O., Lu J., et al. Global sentiments surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic on twitter: analysis of twitter trends. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2) doi: 10.2196/19447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma S., Gustafsson A. Investigating the emerging COVID-19 research trends in the field of business and management: a bibliometric analysis approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020;118:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim E.H.-J., Jeong Y.K., Kim Y., Kang K.Y., Song M. Topic-based content and sentiment analysis of Ebola virus on Twitter and in the news. J. Inf. Sci. 2016;42(6):763–781. doi: 10.1177/0165551515608733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CDC . 2017. Deaths and Mortality.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2017/019.pdf (Accessed 1 February 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maslow A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943;50(4):370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah A.M., Yan X., Shah S.A.A., Shah S.J., Mamirkulova G. Exploring the impact of online information signals in leveraging the economic returns of physicians. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019;98:103272. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang H., Guo X., Wu T. Exploring the influence of the online physician service delivery process on patient satisfaction. Decis. Support Syst. 2015;78:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2015.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajaraman A., Ullman J.D. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom: 2011. Mining of Massive Datasets. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah A., Yan X., Tariq S., Ali M. What patients like or dislike in physicians: analyzing drivers of patient satisfaction and dissatisfaction using a digital topic modeling approach. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021;58(3):102516. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papanikolaou Y., Foulds J.R., Rubin T.N., Tsoumakas G. Dense distributions from sparse samples: improved Gibbs sampling parameter estimators for LDA. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2017;18(1):2058–2115. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens K., Kegelmeyer P., Andrzejewski D., Buttler D. In: Proceedings of the 2012 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning, Association for Computing Machinery, Jeju Island, Korea. Tsujii Jun’ichi, Henderson James, Paşca M., editors. 2012. Exploring topic coherence over many models and many topics; pp. 952–961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song M., Heo G.E., Kim S.Y. Analyzing topic evolution in bioinformatics: investigation of dynamics of the field with conference data in DBLP. Scientometrics. 2014;101(1):397–428. doi: 10.1007/s11192-014-1246-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Röder M., Both A., Hinneburg A. Exploring the space of topic coherence measures. Proceedings of the Eighth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Association for Computing Machinery, Shanghai, China. 2015:399–408. doi: 10.1145/2684822.2685324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehurek R. 2014. Gensim.Models.Coherencemodel – Topic Coherence Pipeline.https://radimrehurek.com/gensim/models/coherencemodel.html [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimmer J., Stewart B.M. Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit. Anal. 2017;21(3):267–297. doi: 10.1093/pan/mps028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sievert C., Shirley K. LDAvis: a method for visualizing and interpreting topics. Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces, Association for Computational Linguistics, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. 2014:63–70. doi: 10.3115/v1/W14-3110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.R.C. Team; 2014. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.http://www.Rproject.org (Accessed 5 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 41.R Studio Inc; 2014. Shiny: Web Application Framework for R; Package Version 0.9.1.http://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=shiny (Accessed 5 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bostock M., Ogievetsky V., Heer J. D3 data-driven documents. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2011;17(12):2301–2309. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2011.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang J., Peng M., et al. A probabilistic method for emerging topic tracking in Microblog stream. World Wide Web. 2017;20(2):325–350. doi: 10.1007/s11280-016-0390-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie W., Zhu F., Jiang J., Lim E., Wang K. TopicSketch: Real-Time Bursty Topic Detection from Twitter. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2016;28(8):2216–2229. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2016.2556661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau J.H., Grieser K., Newman D., Baldwin T. Automatic labelling of topic models. Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Association for Computational Linguistics, Portland, Oregon. 2011:1536–1545. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murthy D. In: The SAGE Handbook of Social media Research Methods. Pertti A., Leonard B., Julia B., editors. SAGE Publications Ltd; London: 2017. The ontology of tweets: mixed methods approaches to the study of twitter; pp. 559–572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beigi G., Hu X., Maciejewski R., Liu H. In: Sentiment Analysis and Ontology Engineering: An Environment of Computational Intelligence. Pedrycz W., Chen S.-M., editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2016. An overview of sentiment analysis in social media and its applications in disaster relief; pp. 313–340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plutchik R. In: Theories of Emotion. Plutchik R., Kellerman H., editors. Elsevier; 1980. A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roseman I.J. Appraisal determinants of emotions: constructing a more accurate and comprehensive theory. Cogn. Emot. 1996;10(3):241–278. doi: 10.1080/026999396380240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta R.K., Yang Y. CrystalFeel at SemEval-2018 task 1: understanding and detecting emotion intensity using affective lexicons. Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2018), Association for Computational Linguistics, New Orleans, Louisiana. 2018:256–263. doi: 10.18653/v1/S18-1038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller M., Banerjee T., Muppalla R., Romine W., Sheth A. What are people tweeting about Zika? An exploratory study concerning its symptoms, treatment, transmission, and prevention. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(2) doi: 10.2196/publichealth.7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chuang J., Manning C.D., Heer J. In: Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces, Association for Computing Machinery, Capri Island, Italy. Tortora Genny, Levialdi S., Tucci M., editors. 2012. Termite: visualization techniques for assessing textual topic models; pp. 74–77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeong H., Yim H.W., et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol. Health. 2016;38 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fu K.-W., Liang H., et al. How people react to Zika virus outbreaks on Twitter? A computational content analysis. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016;44(12):1700–1702. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.04.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li S., Wang Y., Xue J., Zhao N., Zhu T. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: a study on active Weibo users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(6):2032. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xue J., Chen J., et al. Twitter discussions and emotions about the COVID-19 pandemic: machine learning approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(11) doi: 10.2196/20550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Veil S.R., Buehner T., Palenchar M.J. A work-in-process literature review: incorporating social media in risk and crisis communication. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2011;19(2):110–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2011.00639.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Breland J.Y., Quintiliani L.M., Schneider K.L., May C.N., Pagoto S. Social media as a tool to increase the impact of public health research. Am. J. Public Health. 2017;107(12):1890–1891. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2017.304098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]