Abstract

Background

To explore the geographical pattern and temporal trend of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) epidemiology from 1990 to 2019, and perform a bibliometric analysis of risk factors for ASD.

Methods

In this study, ASD epidemiology was estimated with prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) of 204 countries and territories by sex, location, and sociodemographic index (SDI). Age-standardized rate (ASR) and estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) were used to quantify ASD temporal trends. Besides, the study performed a bibliometric analysis of ASD risk factors since 1990. Publications published were downloaded from the Web of Science Core Collection database, and were analyzed using CiteSpace.

Results

Globally, there were estimated 28.3 million ASD prevalent cases (ASR, 369.4 per 100,000 populations), 603,790 incident cases (ASR, 9.3 per 100,000 populations) and 4.3 million DALYs (ASR, 56.3 per 100,000 populations) in 2019. Increases of autism spectrum disorders were noted in prevalent cases (39.3%), incidence (0.1%), and DALYs (38.7%) from 1990 to 2019. Age-standardized rates and EAPC showed stable trend worldwide over time. A total of 3,991 articles were retrieved from Web of Science, of which 3,590 were obtained for analysis after removing duplicate literatures. “Rehabilitation”, “Genetics & Heredity”, “Nanoscience & Nanotechnology”, “Biochemistry & Molecular biology”, “Psychology”, “Neurosciences”, and “Environmental Sciences” were the hotspots and frontier disciplines of ASD risk factors.

Conclusions

Disease burden and risk factors of autism spectrum disorders remain global public health challenge since 1990 according to the GBD epidemiological estimates and bibliometric analysis. The findings help policy makers formulate public health policies concerning prevention targeted for risk factors, early diagnosis and life-long healthcare service of ASD. Increasing knowledge concerning the public awareness of risk factors is also warranted to address global ASD problem.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorders, global burden disease, prevalence, incidence, disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), epidemiology, biblimetric analysis

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a series of neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction, and stereotyped, repetitive patterns of sensory–motor behaviors (1). ASD is associated with heterogeneous symptomatology regarding physical, mental, neurodevelopmental, and functional disorders, which can extend to adulthood and result in a substantial burden on individuals, families, and society (2, 3). Although prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in children have been reported in countries and regions such as the USA (4, 5), China (6), India (7), Europe (8), and Asia (9), there is a lack of epidemiological estimates on prevalence, incidence and ASD-related health loss over time with risk factors (10). In 2016, the Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators reported the developmental disabilities among children younger than 5 years but not specifically focused on the all-age autism spectrum disorders (11, 12). Previous reviews provided global and regional overview of ASD prevalence and commodities, but national-level of ASD burden was not provided (13–15). Moreover, the risk factors leading to ASD were not presented in previous global epidemiological studies for ASD (16).

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database covers epidemiological information on the global, regional and national burden of diseases, injuries, causes of death and risk factors, providing a comprehensive way to investigate the geographical distribution and changes in ASD patterns over time (17). Analyses of current epidemiologic situations and temporal trends may help policy makers assess the global ASD burden, allocate resources, and formulate relevant policies. This information can further guide diagnosis, prevention, intervention and rehabilitation efforts for collaboration in regions with various degree of socioeconomic development (18–20).

In addition, understanding the status and frontier of the risk factors will facilitate researchers to investigate corresponding prevention approaches. Although many risk factors for ASD have been proposed, the complex causes of autism have made it difficult to link the complicated issue with a definite risk (21), which is not included in the GBD database yet. Hence, this study aimed to present the epidemiological estimates of autism spectrum disorders in terms of prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) from 1990 to 2019 with GBD database. Besides, a bibliometric analysis was conducted to comprehensively analyze the research hotspots of ASD risk factors.

Methods

Overview

GBD Collaborator Group is a scientific council producing cutting-edge database of the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors (17). GBD 2019 estimated global epidemiology covering incidence, prevalence, mortality, years lived with disability (YLDs), years of life lost (YLLs), and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) in 204 countries and territories grouped into 21 regions. Data utilized in this study were retrieved and publicly available from the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) website. The study followed the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) recommendations (22).

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are characterized by persistent impairments in social communication, reciprocal interaction, and the presence of restricted, stereotypical behaviors. ASD is a non-fatal but life-long disease commencing in early childhood with overlapping neurodevelopmental causes. In the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ASD diagnostic criteria eliminated diagnostic subtypes (autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disabilities-Not Otherwise Specified), and designated as a single category (23).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (version 4.1.2). ASD burden was measured using prevalence, incidence, DALYs, and corresponding age-standardized rates in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019. A team of librarians identified multiple relevant data sources from published literature and websites. Standard methods, such as Bayesian meta-regression tool and regression methods, have been used to estimate prevalence, incidence and DALYs with uncertainty intervals (UIs) of autism spectrum disorders by location, year and sex by the GBD Collaborators using multiple modeling software (17). Based on the ordered draw of the modeling process, 95% UI, similar with confidence intervals (CI) mathematically, were identified from the epidemiological estimation methodology. The raw data were publicly available from the GBD Results Tool (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/). Age-standardized rate (ASR) and estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) were used to quantify temporal trends of ASD (24). Specifically, ASR was the sum of the product of the ratio of each age group (most are five years per group) with redistribution and the weight of the selected population group, divided by the total weight of the standard population. As a result, ASRs, including age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR), age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) and age-standardized DALY rate, could exclude the interference from variations in age distribution and population quantity. ASR was reported per 100,000 populations annually. Meanwhile, the EAPC point estimation based on ASR was employed to reflect the shifting trends of ASD burden over time. EAPC was calculated with the formula EAPC = 100 × [exp(β) − 1], where β demonstrated the secular trend of ASR in the 30 years. If the EAPC estimation and its 95% confidence interval were both above/below zero, the corresponding ASR was in an increasing/decreasing trend. Otherwise, the changing trend of ASR was deemed to be stable.

Socio-demographic index (SDI) was a comprehensive measurement of educational attainment, lagged distributed income, and total fertility rate to describe socioeconomic development status (25, 26). The countries and territories were categorized into five SDI quintiles (low, low-middle, middle, high-middle, and high). Finally, we calculated Pearson's correlation coefficient between EAPCs and ASRs and between EAPCs and SDI values in 2019, to investigate influential factors of ASR change trends (27).

Risk factor for autism spectrum disorder is multifactorial, such as genetic predispositions or environmental factors, which has not been included in the GBD database. Hence, the current study obtained literature published from January 1, 1990 to November 7, 2022 to make a preliminary bibliometric analysis. The retrieved results were analyzed using CiteSpace (version 6.1 R3), a literature visualization and analysis software developed to identify scientific progress and research frontiers of a certain field (28). The search strategy included the terms “autism” and “risk factor” from Web of Science. The literature was limited to English language, and finally 3,590 references were obtained after removing duplicates. For visualization, we selected “Top 50 levels of most occurred items from each slice” and “Pruning/pathfinder” to generate keyword clustering.

Results

ASD epidemiology in 2019

Globally, there were estimated 28.3 million (95% UI, 23.5–33.8 million) prevalent cases of autism spectrum disorders, with an age-standardized prevalence rate of 369.4 (95%UI, 305.9 to 441.2 in 2019 (Table 1). ASD was responsible for 603,790 (95% UI, 501,680 to 720,097) incident cases globally, with an age-standardized incidence rate of 9.3 (95% UI, 7.7 to 11.1) in 2019. In addition, ASD accounted for 4.3 million (95% UI, 2.8 to 6.2) DALYs, with an age-standardized rate of 56.3 (95% UI, 36.8 to 81.5) DALYs in 2019 (Table 2). For SDI regions, the Middle SDI region had the highest burden of prevalent cases and DALYs in 2019, while the Low-middle SDI region had the most incident cases. Geographical distribution of the prevalence, incidence and DALYs estimates for autism spectrum disorders in 2019 were presented in Figures 1, 2, and Supplementary Figure S1.

Table 1.

Number and age-standardized prevalence rate for ASD by global burden of disease region in 1990 and 2019.

| Prevalent cases No. (95% UI) | ASPR/100,000 No. (95% UI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2019 | 1990 | 2019 | |

| Overall | 20,336,256 (16,857,367–24,222,582) | 28,324,939 (23,500,644–33,811,271) | 372.8 (309.1–444.9) | 369.4 (305.9–441.2) |

| Male | 15,647,724 (12,986,732–18,607,125) | 21,633,776 (17,985,166–25,761,348) | 571.2 (473.8–679.6) | 560.1 (465.2–6667.3) |

| Female | 4,688,533 (379,052–57,118,664) | 6,691,162 (5,436,262–8,153,529) | 173.4 (140.9–211.5) | 176.3 (143.0–214.5) |

| High SDI | 4,319,311 (3,613,076–5,102,134) | 5,484,192 (4,587,041–6,520,432) | 539.6 (451.7–638.4) | 579.3 (485.3–684.5) |

| High-middle SDI | 4,665,416 (3,863,289–5,575,606) | 5,520,271 (4,566,936–6,619,212) | 404.6 (334.9–483.3) | 405.4 (335.9–485) |

| Middle SDI | 5,698,916 (4,667,746–6,901,112) | 7,566,752 (6,220,224–9,144,158) | 319.7 (262.7–387.2) | 321.4 (264.5–388) |

| Low-middle SDI | 3,710,774 (3,057,599–4,450,285) | 5,612,896 (4,621,359–6,739,732) | 311.5 (257.2–373.9) | 312.8 (258.2–375.7) |

| Low SDI | 1,931,430 (1,592,707–2,329,440) | 4,125,396 (3,401,890–4,965,501) | 340.5 (280.2–408.3) | 342.2 (281.4–410.2) |

| Andean Latin America | 136,708 (112,528–164,539) | 219,156 (180,811–263,070) | 340.4 (280.9–408.5) | 342.1 (282.4–410.5) |

| Australasia | 86,986 (72,543–103,962) | 119,973 (100,247–143,664) | 436.8 (364.3–521.8) | 436.1 (363.8–521.2) |

| Caribbean | 159,035 (137,865–183,541) | 206,648 (178,807–238,417) | 344.2 (284–414.1) | 343.8 (283.7–413.6) |

| Central Asia | 10,875 (8886–13,126) | 20,847 (17,026–25,167) | 371.7 (305.9–446.9) | 374.8 (308–450.9) |

| Central Europe | 268,361 (220,526–321,320) | 354,787 (291,432–426,875) | 370.5 (305.8–443.3) | 373.6 (308.4–446.9) |

| Central Latin America | 445,113 (367,189–532,928) | 393,541 (325,032–472,445) | 351.7 (289.6–420.6) | 350.9 (288.8–419.5) |

| Central sub-Saharan Africa | 608,677 (502,158–726,427) | 875,348 (720,122–1,047,034) | 370.4 (303–446.3) | 370.8 (303.3–446.9) |

| East Asia | 4,412,839 (3,624,038–5,309,093) | 5,098,806 (4,206,229–6,150,048) | 353.5 (290.3–425.4) | 367.8 (304.4–441.9) |

| Eastern Europe | 866,526 (716,655–1,038,602) | 773,320 (638,888–927,709) | 394.8 (326.1–472.8) | 397.3 (328.3–476) |

| Eastern sub-Saharan Africa | 776,444 (638,587–926,809) | 1,667,223 (1,372,086–1,991,501) | 378.2 (311.7–454.2) | 378.4 (311.7–454.4) |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 1,047,349 (872,107–1,244,347) | 1,078,242 (895,833–1,288,544) | 617.8 (515–734.7) | 634.3 (528.8–756.7) |

| High-income North America | 1,435,440 (1,210,088–1,685,566) | 2,185,918 (1,833,599–2,587,355) | 526.2 (443.4–617.9) | 640 (537.7–756.4) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 1,105,582 (911,505–1,326,857) | 1,879,528 (1,550,850–2,261,649) | 303.5 (250.4–365.5) | 304.4 (251.2–366.1) |

| Oceania | 19,903 (16,274–23,989) | 40,114 (32,728–48,523) | 290 (236.8–350.4) | 289 (235.5–349) |

| South Asia | 3,370,030 (2,767,916–4,062,245) | 5,310,541 (4,355,785–6,406,808) | 291.9 (240.1–351.9) | 290 (238.4–349.2) |

| Southeast Asia | 1,519,341 (1,253,044–1,824,857) | 2,097,143 (1,729,612–2,515,054) | 310.5 (256.1–373.2) | 312.5 (257.7–374.4) |

| Southern Latin America | 240,321 (199,640–288,082) | 313,298 (260,284–376,359) | 480.8 (399.3–576.6) | 482.5 (400.8–579) |

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | 204,885 (167,918–245,329) | 298,595 (244,999–358,553) | 369.4 (302.9–444.8) | 371.6 (304.9–447.7) |

| Tropical Latin America | 563,007 (465,390–674,324) | 774,446 (638,700–930,842) | 353.9 (292–425.4) | 353.9 (292–425.3) |

| Western Europe | 2,113,126 (1,773,298–2,507,729) | 2,354,684 (1,967,645–2,791,090) | 573.7 (482.7–679.9) | 581.3 (488.2–686.4) |

| Western sub-Saharan Africa | 769,073 (634,591–917,695) | 1,807,743 (1,490,123–2,160,089) | 375.3 (309.6–449) | 370.6 (305.5–443.3) |

ASD, autism spectrum disorders; ASPR, age-standardized prevalence rate; SDI, sociodemographic index.

Table 2.

Number and age-standardized rates of incidence and of DALYs for ASD by global burden of disease region in 1990 and 2019.

| Incident cases No. (95% UI) | ASIR/100,000 No. (95% UI) | DALYs No. (95% UI) | Age-standardized DALY rate/100,000 No. (95% UI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2019 | 1990 | 2019 | 1990 | 2019 | 1990 | 2019 | |

| Overall | 602,887 (501,382–718,288) | 603,790 (501,680–720,097) | 9.2 (7.6–10.9) | 9.3 (7.7–11.1) | 3,105,909 (2,025,303–4,514,467) | 4,306,615 (2,821,512–6,232,361) | 56.7 (37–82.2) | 56.3 (36.8–81.5) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 461,633 (386,362–548,162) | 459,493 (384,472–544,406) | 13.6 (11.4–16.1) | 13.7 (11.5–16.3) | 2,393,774 (1,560,490–3,443,926) | 3,294,468 (2,152,733–4,769,103) | 86.9 (56.7–125.1) | 85.3 (55.8–123.6) |

| Female | 141,254 (113,407–170,938) | 144,297 (115,510–174,371) | 4.4 (3.6–5.4) | 4.6 (3.7–5.6) | 712,135 (467,655–1,041,370) | 1,012,148 (663,237–1,477,450) | 26.2 (17.2–38.2) | 26.8 (17.5–39.2) |

| Sociodemographic index | ||||||||

| High SDI | 75,696 (63,921–89,058) | 72,189 (60,836–84,979) | 13.3 (11.3–15.7) | 14.5 (12.3–17.1) | 654,789 (429,489–932,431) | 822,967 (541,875–1,175,034) | 82.2 (53.8–117.4) | 88.2 (57.9–126.3) |

| High-middle SDI | 100,983 (83,515–120,117) | 77,479 (64,215–92,332) | 10.2 (8.4–12.1) | 10.3 (8.6–12.3) | 713,059 (465,214–1,032,597) | 838,198 (546,345–1,211,677) | 61.8 (40.3–89.5) | 62.1 (40.4–89.8) |

| Middle SDI | 173,883 (143,431–208,737) | 139,286 (114,750–167,032) | 8.4 (6.9–10.1) | 8.1 (6.7–9.7) | 875,927 (569,681–1,284,765) | 1,155,444 (754,951–1,679,972) | 48.8 (31.8–71.5) | 49.2 (32.1–71.6) |

| Low-middle SDI | 148,418 (122,088–177,306) | 137,109 (1,126,789–163,455) | 8.2 (6.7–9.8) | 8.1 (6.6–9.6) | 566,661 (372,963–827,871) | 856,771 (561,754–1,245,320) | 47.2 (31–68.5) | 47.6 (31.2–69.1) |

| Low SDI | 103,577 (85,506–123,644) | 151,149 (124,811–180,571) | 9.2 (7.6–10.9) | 8.37 (6.9–10.0) | 293,883 (191,832–427,362) | 630,885 (414,559–917,940) | 51.3 (33.6–74.5) | 51.9 (34.1–75.2) |

| Region | ||||||||

| Andean Latin America | 5,235 (4322–6299) | 5,659 (4672–6810) | 9.1 (7.5–10.9) | 9 (7.4–10.8) | 20,989 (13,726–30,731) | 33,571 (22,051–48,663) | 51.9 (33.9–75.6) | 52.3 (34.4–75.9) |

| Australasia | 1,669 (1396–1988) | 1,957 (1636–2333) | 11 (9.2–13.1) | 11.1 (9.3–13.2) | 13,166 (8,637 –18,709) | 18,038 (11,831–26,144) | 66.4 (43.6–94.3) | 66.3 (43.5–96.1) |

| Caribbean | 2,918 (2537–3357) | 2,745 (2369–3134) | 15 (13–17.2) | 15.2 (13.1–17.3) | 24,224 (15,958–33,906) | 31,128 (21,014–44,022) | 91.6 (60.3–129) | 92.9 (62.4–131.9) |

| Central Asia | 596 (491–717) | 923 (759–1109) | 9.9 (8.1–11.9) | 9.8 (8.1–11.8) | 1,646 (1092–2399) | 3,173 (2084–4577) | 55.1 (36.5–80.7) | 55.3 (36.5–80) |

| Central Europe | 9,227 (7599–11,021) | 8,923 (7349–10,654) | 9.9 (8.1–11.8) | 9.9 (8.1–11.8) | 41,257 (26,948–60,088) | 54,402 (35,733–78,754) | 56.9 (37.3–82.7) | 57.4 (37.7–83.2) |

| Central Latin America | 7,550 (6234–8948) | 4,860 (4014–5764) | 9.4 (7.8–11.1) | 9.4 (7.8–11.2) | 67,585 (43,770–97,177) | 59,276 (38,737–85,387) | 56.5 (36.6–81.2) | 57.1 (37.2–82) |

| Central sub-Saharan Africa | 21,860 (18,043–26,050) | 19,340 (15,980–23,070) | 9.2 (7.6–11) | 9.2 (7.6–10.9) | 93,735 (61,359–134,650) | 133,793 (87,313–194,854) | 53.7 (35.1–77.3) | 53.6 (35–78.2) |

| East Asia | 111,604 (91,661–133,843) | 71,074 (58,298–84,934) | 9.3 (7.6–11.1) | 9.6 (7.9–11.5) | 680,072 (444,396–996,214) | 778,339 (509,697–1,129,871) | 54.3 (35.4–79.6) | 56.6 (37–82.7) |

| Eastern Europe | 14,259 (11,834–17,033) | 11,166 (9244–13,324) | 10.2 (8.4–12.1) | 10.3 (8.5–12.3) | 131,359 (85,365–190,703) | 116,804 (76,389–169,067) | 60.2 (39.2–87.3) | 60.8 (39.6–87.8) |

| Eastern sub-Saharan Africa | 42,923 (35,394–51,307) | 67,380 (55,602–80,554) | 10.1 (8.3–12.1) | 10 (8.2–11.9) | 118,378 (77,519–171,365) | 255,582 (168,416–369,498) | 57.1 (37.3–82.6) | 57.4 (37.7–83.1) |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 14,603 (12,198–17,337) | 10,412 (8699–12,345) | 15.4 (12.9–18.3) | 15.7 (13.1–18.6) | 159,572 (104,216–229,855) | 162,304 (106,518–233,835) | 94.5 (61.6–136.4) | 97.3 (63.6–141) |

| High-income North America | 29,858 (25,081–35,106) | 33,093 (27,800–38,830) | 13.6 (11.4–16) | 16.4 (13.8–19.3) | 216,781 (142,092–307,646) | 326,234 (215,047–462,932) | 79.9 (52.3–113.3) | 96.9 (63.7–137.7) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 44,221 (36,225–53,111) | 45,002 (36,857–53,912) | 7.9 (6.5–9.5) | 7.7 (6.3–9.3) | 170,028 (110,895–247,697) | 287,617 (188,299–418,662) | 46.3 (30.2–67.6) | 46.4 (30.4–67.5) |

| Oceania | 808 (661–977) | 1,506 (1228–1822) | 7.6 (6.2–9.2) | 7.6 (6.2–9.3) | 3,050 (1985–4418) | 6,136 (3980–8860) | 44 (28.7–63.9) | 43.9 (28.6–63.2) |

| South Asia | 129,806 (106,720–155,432) | 121,886 (100,113–145,614) | 7.6 (6.2–9) | 7.6 (6.2–9.1) | 512,702 (337,803–748,333) | 808,171 (530,435–1,176,149) | 44 (29–64.4) | 44 (28.9–63.9) |

| Southeast Asia | 49,221 (40,292–58,767) | 42,761 (34,987–51,276) | 8.2 (6.7–9.7) | 8.2 (6.7–9.8) | 233,298 (151,876 –343,401) | 321,010 (208,179–470,066) | 47.3 (30.9–69.5) | 47.8 (31–70.1) |

| Southern Latin America | 6,094 (5094–7271) | 5,784 (4838–6900) | 12.1 (10.2–14.5) | 12.5 (10.4–14.9) | 36,786 (23,775–52,798) | 47,678 (30,967–68,855) | 73.5 (47.5–105.4) | 73.7 (47.9–106.2) |

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | 7,211 (5956–8603) | 7,815 (6468–9334) | 9.8 (8.1–11.7) | 9.8 (8.1–11.7) | 31,425 (20,608–45,813) | 45,505 (29,825–65,836) | 56.2 (36.7–81.3) | 56.4 (37–81.4) |

| Tropical Latin America | 15,756 (13,009–18,760) | 14,382 (11,894–17,114) | 9.2 (7.6–11) | 9.3 (7.7–11.1) | 86,132 (56,209–124,848) | 117,552 (76,819–170,312) | 53.8 (35.2–78.2) | 53.9 (35.2–78) |

| Western Europe | 31,691 (26,879–37,291) | 29,331 (24,871–34,482) | 14.2 (12.1–16.7) | 14.2 (12–16.7) | 319,676 (208,840–454,860) | 353,845 (233,430 –504,526) | 87.5 (57.1–125) | 88.7 (58.1–127.1) |

| Western sub-Saharan Africa | 42,800 (35,511–51,287) | 77,149 (64,001–92,454) | 10 (8.3–12) | 9.8 (8.2–11.8) | 117,111 (76,701–169,033) | 276,573 (181,323–400,818) | 56.7 (37.2–81.6) | 56.2 (36.9–81.3) |

ASD, autism spectrum disorders; ASIR, age-standardized incidence rate; DALY, disability-adjusted life year; SDI, sociodemographic index.

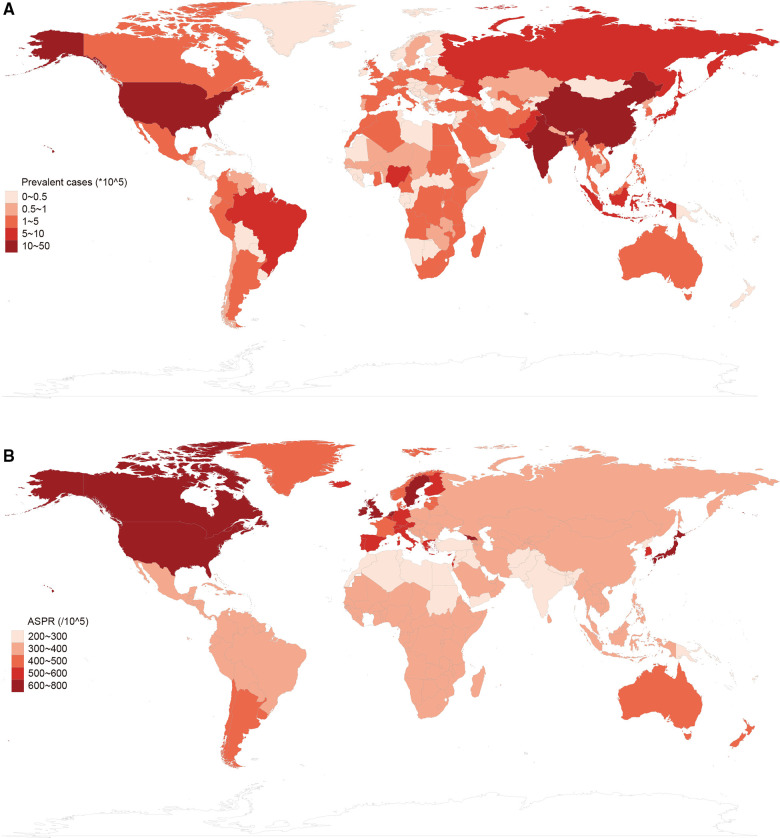

Figure 1.

Global prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in 2019. (A) Prevalent cases of autism spectrum disorders by location for both sexes in 2019. (B) Age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR) of autism spectrum disorders by location for both sexes in 2019.

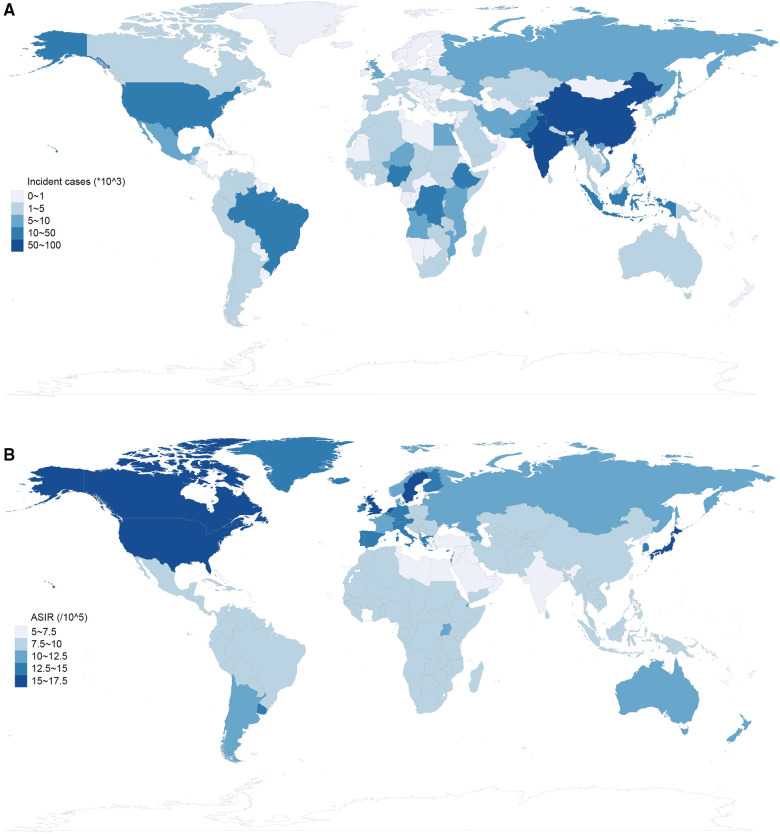

Figure 2.

Global incidence of autism spectrum disorder in 2019. (A) Incident cases of autism spectrum disorders by location for both sexes in 2019. (B) Age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of autism spectrum disorders by location for both sexes in 2019.

Temporal trends of ASD prevalence from 1990 to 2019

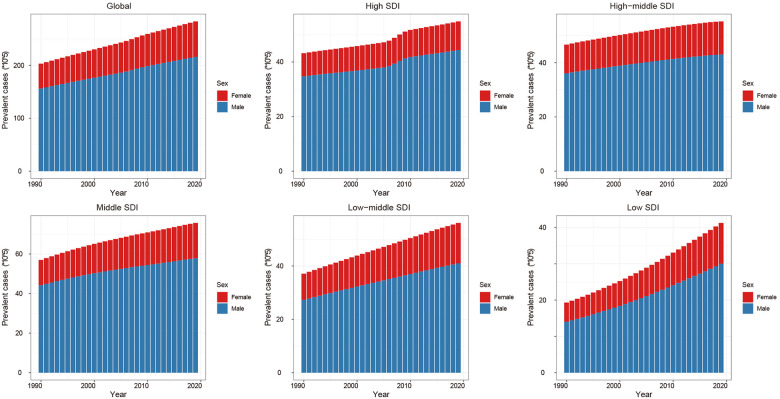

From 1990 to 2019, the global ASD prevalent cases increased by 39.3% and the age-standardized prevalence rate has not almost improvement [EAPC = −0.02, 95% CI (−0.03 to −0.01), Supplementary Table S1]. Males were more likely to have ASD than females (male to female ratio in ASIR = 3.34:1 in 1990, and 3.23:1 in 2019). At the regional level, the age-standardized prevalence rate of ASD was found to be highest in high-income North America [640.0 (95% UI, 537.7 to 756.4)], high-income Asia Pacific [634.3 (95% UI, 528.8 to 756.7)] and Western Europe [581.3 (95% UI, 488.2 to 686.4)] (Table 1). Subgroup analysis by SDI regions demonstrated that although high SDI region had the most rapid increase in prevalence (ASPR: 539.6 in 1990 and 579.3 in 2019, EAPC = 0.30, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.35) (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S1). At the level of country or territory, there was wide geographic variation in the ASPR of ASD (range, 215.8 to 739.6). United Kingdom [739.6 (95% UI, 617.2 to 876.3)], Sweden [706.8 (95% UI, 589.1 to 838.5)] and Japan [676.5 (95% UI, 562.8 to 805)] had the three highest ASPR in 2019 (Figure 1, Supplementary Tables S1, S5).

Figure 3.

Global prevalence of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) by sex and socio-demographic index (SDI) quintiles from 1990 to 2019.

Temporal trends of ASD incidence from 1990 to 2019

From 1990 to 2019, the global ASD incidence has not been improved since incident cases increased marginally by 0.1% and the age-standardized prevalence rate increased by 1.1% [EAPC = 0.06, 95% CI (0.04 to 0.07), Supplementary Table S2]. Females had fewer ASD incidence than males (1990: 461,633 in males and 141,254 in females; 2019: 459,493 in males and 144,297 in females). At the regional level, the age-standardized incidence rate of ASD was highest in high-income North America 16.4 (95% UI, 13.8 to 19.3), high-income Asia Pacific 15.7 (95% UI, 13.1 to 18.6) and Caribbean 15.2 (95% UI, 13.1 to 17.3) (Table 2). For SDI regions, the high SDI region had the most increase in age-standardized incidence rate from 1990 to 2019 (change = 9%; EAPC = 0.36, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.41, Supplementary Table S2). At the level of country or territory, ASIR varied from 5.4 to 18.6. Andorra [18.6 (95% UI, 15.3 to 22.3)], United Kingdom [18.0 (95% UI, 15 to 21.2)] and Sweden [17.1 (95% UI 14.4 to 20.2)] had the three highest age-standardized prevalence rates in 2019 (Figure 2, Supplementary Tables S2 and S5).

Temporal trends of ASD DALYs from 1990 to 2019

From 1990 to 2019, the global ASD DALYs increased by 38.7% and the age-standardized DALY rate has almost no improvement [EAPC = −0.02, 95% CI (−0.03 to −0.01), Supplementary Table S3]. The number of global DALYs in males was higher than in females (1990: 2393774.2 in male and 712134.9 in females; 2019: 3294467.6 in males and 1012147.8 in females). At the regional level, the age-standardized DALYs rate of ASD was found to be highest in high-income Asia Pacific 97.3 (95% UI, 63.6 to 141), high-income North America 96.9 (95% UI, 63.7 to 137.7) and Caribbean 92.9 (95% UI, 62.4 to 131.9) (Table 2). Subgroup analysis by SDI regions demonstrated that although the high SDI region had the most rapid increase in DALYs (age-standardized DALY rate: 82.2 in 1990 and 88.2 in 2019, EAPC = 0.81, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.95, Supplementary Table S3). At the level of country or territory, age-standardized incidence DALYs rates varied from 33.3 to 112.3 among the countries and territories. United Kingdom [112.3 (95% UI, 73.7 to 160.5)], Sweden [108.0 (95% UI, 71.2 to 155.3)] and Japan [103.8 (95% UI, 67.7 to 149.7)] showed the highest age-standardized DALYs rates in 2019 (Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

Correlation between the socio-demographic Index and ASD epidemiology

Pearson's correlation coefficients between ASRs in 1990 and the corresponding EAPC values were not statistically significant (Supplementary Figure S6). We explored the association between SDI in 2019 and EAPC values of ASPR, ASIR, and age-standardized DALY rate among the countries and territories. The results demonstrated that the associations between SDI, and EAPCs of ASIR and age-standardized DALY rate, were not statistically significant. However, the EAPC value of ASPR was positively associated with SDI in 2019 (Supplementary Figure S7). Further, we investigated the correlation between SDI and ASPR, ASIR, and age-standardized DALY rate from 1990 to 2019. As a result, all ASRs were significantly and positively correlated with corresponding SDI values (correlation coefficient of ASPR = 0.672, of ASIR = 0.638, of age-standardized DALY rate = 0.681, P < 0.05) in 21 regions worldwide. For most countries and territories, after a decrease in expected ASRs, these rates increased rapidly when SDI values were higher than 0.4 in 2019 (Supplementary Figures S8–S10).

Bibliometric analysis

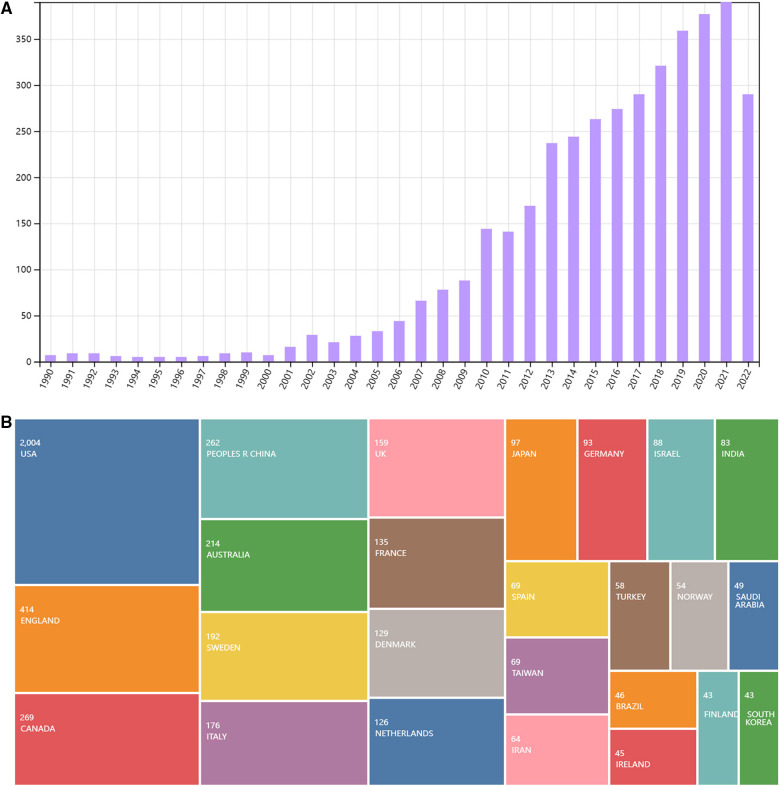

A total of 3,991 articles in English were retrieved from Web of Science. After deleting duplicate literatures, 3,590 references were obtained for risk factors of ASD. As presented in Figure 4A, the overall number has been increasing since 1990. Among the countries/territories, USA, England, Canada, China, and Australia make leading contributions to exploring ASD risk factors in the past decades (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) The number of publications on risk factors of ASD since 1990. (B) Leading countries or territories that contributed to publications on risk factors of ASD since 1990.

ASD risk factors-research categories

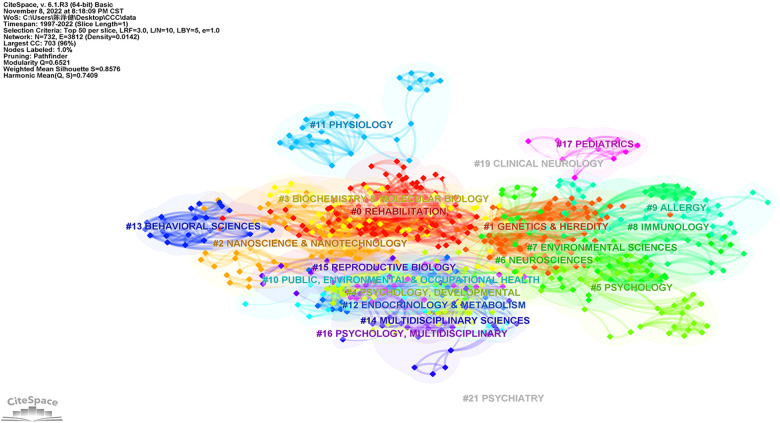

In the current study, we identified the top research categories with citations analyzed by the CiteSpace software. As demonstrated in Figure 5, research category was represented a cloud of circular nodes, with the areas depicting the number of research literature in each field. Moreover, the node orientations demonstrated the publication's importance. As a result, “#0 Rehabilitation”, “#1 Genetics & Heredity”, “#2 Nanoscience & Nanotechnology”, “#3 Biochemistry & Molecular biology”, “#4/5 Psychology”, “#6 Neurosciences”, and “#7 Environmental Sciences” may have played pivotal roles in the field of ASD risk factors since 1990.

Figure 5.

The cluster map of co-occurrence research categories related to risk factors on ASD since 1990.

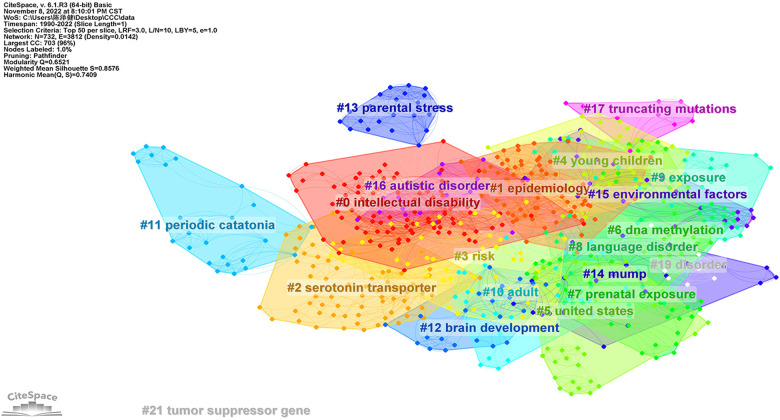

ASD risk factors-keywords clustering

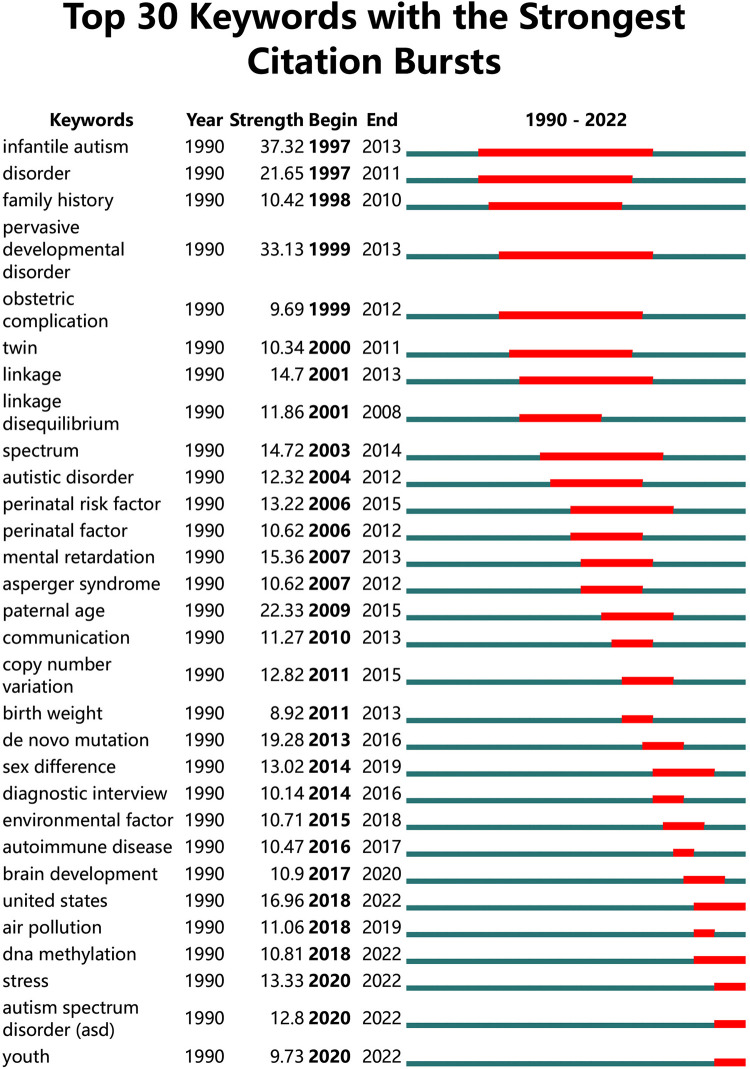

We use the default setting of CiteSpace (Slice length = “1” year; Select the node type = “Keyword”; Top N = “50”) and a pruning algorithm to cluster the keywords. After processing, top keywords with the strongest co-occurrence frequency were found to understand hotspots in this field since 1990. As shown in the Figure 6, the Mean Silhouette score was 0.8576, and the Modularity Q score was 0.7409. The emerging clusters revealed that ASD risk factors could be multifaceted and there is no definite conclusion. Hence, we used Burst Keywords analysis to explore the risk factor receiving high attention in the past decades (Figure 7). For example, “Pervasive developmental disorder”, “obstetric complication”, and “perinatal factor” were of the earliest burst. In recent years, “de novo mutation”, “environmental factor”, and “DNA methylation” have been among the most focused keywords.

Figure 6.

The cluster map of co-occurrence keywords related to risk factors on ASD since 1990.

Figure 7.

The top 30 keywords with the strongest citation bursts related to risk factors on ASD since 1990.

Discussion

In this study, we presented the epidemiological estimates and temporal trends of autism spectrum disorders based on the GBD database at the global, regional, and national levels from 1990 to 2019. Globally, there were estimated 28.3 million prevalent cases (ASR, 369.4 per 100,000 populations), 603,790 incident cases (ASR, 9.3 per 100,000 populations) and 4.3 million DALYs (ASR, 56.3 per 100,000 populations) in 2019. From 1990 to 2019, the prevalent cases and DALYs of ASD increased by almost 40%, while incidence and the ASRs have not been improved. We found the ASRs were significantly higher in the high SDI region, and the ASRs increased as SDI increased except the low SDI region. Moreover, we identified the hotspots concerning ASD risks factors since 1,900 because it is not provided in the GBD database.

Understanding the epidemiology of ASD burden facilitates tailoring health programs to address this great health challenge. Studies have shown that ASD was the leading cause of disability among all mental disorders in children globally but lack of knowledge concerning its geographical distribution in all-age populations (11, 29). A systematic review on ASD prevalence and DALYs found estimated 52 million prevalent cases (ASR, 760) and 7.7 million DALYs (ASR, 58.2) of ASD worldwide in 2010 (13). However, it is impracticable to compare with our report because of substantial differences in methodologies and data sources. The review included much epidemiological data from high-income countries, lack in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially Africa, Latin America and Central and Eastern Europe (10, 13). At the national level, the age-standardized prevalence rates ranged from 215.8 to 739.6 per 100,000 populations in our study, which were greatly lower than previous reports (30). The reason for the considerable but not contradictory differences mainly lied in the study population: our study highlighted the all-age populations while most epidemiological studies were only concerned with children and young adolescents. As the incident rate has been increasing but tending to be stable (EAPC = 0.06), the overall ASPR could have been attenuated by the underemphasized age groups (Supplementary Table S5). Besides, data sources could have led to heterogeneous results, such as data derived from health records or parents' report, and from nationally representative population or selected sites (5, 31, 32). Our study also showed a male preponderance in ASRs similar to previous studies, which were related to complicated but unknown mechanisms, including environmental, genetic or epigenetic reasons (13, 33, 34).

Monitoring the temporal trend of ASD burden helps find the emerging challenges and adapt health systems over time. Globally, the ASD prevalent cases and DALYs increased by almost 40% in the past 30 years, while the ASRs and incidence tended to be stable. Such increases may be mainly attributable to the global population growth, instead of change in ASD incidence (29). As the ASRs were deemed unchanging over time, etiological research and primary prevention for reducing ASD incidence deserve continuous attention for a long time to come (30). Furthermore, ASD symptoms could extend beyond childhood and persist across lifespan although it was commonly perceived to be childhood disorders (35). Hence, the epidemiological data in all-age populations, including children, adolescents and adults, should draw attention when considering the increasing burden over time. Meanwhile, medical resources on the topic of early diagnosis and therapy are crucial for secondary prevention of permanent disabilities during golden period sensitive to treatment (36). Additionally, regions especially those with high prevalent cases, such as China, India and USA, should formulate policies to support long-term healthcare service, education, skills training and vocational assistance for rehabilitation (tertiary prevention) and reducing stigmatization (37, 38).

We investigated the correlation between social development status and ASD burden, which may shed a light on ASD prevention and international cooperation to address disease burden. The causes of ASD were unrevealed but usually attributed to complex genetics-environment interactions. According to the results, all ASRs were positively correlated with SDI values from 1990 to 2019. For most countries and territories, after a decrease in expected ASRs, these rates increased rapidly when SDI values were higher than 0.4 in 2019. The positive correlation was underpinned by the view that awareness, concepts, and healthcare service availability of ASDs could be improved with social development (39). Moreover, environmental exposure, such as air pollution and endocrine-disrupting chemicals, was accompanied with socioeconomic development in the past decades (30). However, there was a paradox when attributing to socioeconomic status, because ASD burden in low SDI region did not fit the association. This result might be explained by non-etiologic reasons in LMICs, such as public awareness since the diagnosis was based on social and contextual observations (40, 41) or etiologic factors such as genetic and environmental risk factors (30).

ASD is a complex multifactorial disease, and it needs interdisciplinary cooperation to find out the linking causes with the issue, such as Genetic & Heredity, Biochemistry, Public health and Environmental sciences, etc. For example, parental age, environmental exposure, de novo mutations and epigenetic alterations were shown associated with ASD risk (1, 21, 42). After bibliometric analysis, we found literature on risk factors for ASD shows a growing trend since 1999. Moreover, some emerging research directions could provide new perspective on ASD etiology. Previous studies found that allergic diseases are over-represented in ASD and hypothesized that immune dysregulation may have contributed to autism pathogenesis (43). Furthermore, gut microbiome can modulate gastrointestinal physiology and immune system relevant to ASD symptoms (44). More specifically, we can inspect the change of research hotspots from keywords with citation burst over time. Earlier bursts indicated that previous studies focused on family history, developmental psychology, and prenatal factors. In recent years, advances in technology have led to further exploration into genetics, immune systems, and environmental factors (30, 45, 46).

This study has several limitations. First, although the GBD provides spatiotemporal estimates of disease burden for geographical location with sparse data, the accuracy and reliability of modeling rely on the quality of data used in the study, thus the epidemiological estimates should be interpreted with cautions (17). Second, the study included literature only from Web of science. Future study could include articles in multiple databases with various languages to reduce bias. Third, due to the restrictions of data type, further investigation stratified by pathophysiology, etiology, and disease severity should be conducted in future studies (47). Considering that different ASD phenotypes can be associated with psychiatric, mental, and physical disorders (14, 15), GBD models should include monitoring comorbidities to address the overall and life-long needs of individuals with autism spectrum disorders.

Conclusions

Autism spectrum disorders remain a global public health problem. The global prevalent cases and DALYs of ASD increased greatly with population growth, while age-standardized rates and incidence has not been improved from 1990 to 2019. The increased ASRs were associated with higher sociodemographic status except the low SDI region, although which was the main contributor to the rapid increases in prevalent cases and DALYs. The epidemiological findings could help policy makers illustrate the global health challenge to formulate policies and implement measures for prevention from risk factors, early diagnosis, and life-long healthcare service. Increasing knowledge concerning the public awareness, risk factors, diagnostic criteria and interventions are also warranted to reduce ASD burden.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation staff and the Global Burden of Disease Study collaborators for their work.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

YAL, ZJC and XDL: conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the data, drafted the first draft of the manuscript and edited subsequent drafts, and generated all figures and tables. YAL: conducted the bibliometric analysis. MHG, YAL and NX: carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. CG, ZWZ, GY, HYX, XPW, YLL, XHH, and ML: contributed to the interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JX and XLH: conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.972809/full#supplementary-material.

References

- 1.Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet. (2018) 392(10146):508–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31129-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Dewik N, Al-Jurf R, Styles M, Tahtamouni S, Alsharshani D, Alsharshani M, et al. Overview and Introduction to autism Spectrum disorder (ASD). Adv Neurobiol. (2020) 24:3–42. 10.1007/978-3-030-30402-7_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. (2014) 168(8):721–8. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu G, Strathearn L, Liu B, Bao W. Prevalence of autism Spectrum disorder among US children and adolescents, 2014-2016. Jama. (2018) 319(1):81–2. 10.1001/jama.2017.17812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, Durkin MS, Esler A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism Spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2021) 70(11):1–16. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou H, Xu X, Yan W, Zou X, Wu L, Luo X, et al. Prevalence of autism Spectrum disorder in China: a nationwide multi-center population-based study among children aged 6 to 12 years. Neurosci Bull. (2020) 36(9):961–71. 10.1007/s12264-020-00530-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patra S, Kar SK. Autism spectrum disorder in India: a scoping review. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2021) 33(1–2):81–112. 10.1080/09540261.2020.1761136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delobel-Ayoub M, Saemundsen E, Gissler M, Ego A, Moilanen I, Ebeling H, et al. Prevalence of autism Spectrum disorder in 7-9-year-old children in Denmark, Finland, France and Iceland: a population-based registries approach within the ASDEU project. J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 50(3):949–59. 10.1007/s10803-019-04328-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu S, Lu Y, Li Y, Shi J, Cui H, Gu Y, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 284:112679. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh YJ, Kim YS, Kauchali S, Marcín C, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. (2012) 5(3):160–79. 10.1002/aur.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.GBD. Developmental disabilities among children younger than 5 years in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Glob Health. (2018) 6(10):e1100–e21. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30309-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matson JL, Cervantes PE, Peters WJ. Autism spectrum disorders: management over the lifespan. Expert Rev Neurother. (2016) 16(11):1301–10. 10.1080/14737175.2016.1203255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxter AJ, Brugha TS, Erskine HE, Scheurer RW, Vos T, Scott JG. The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychol Med. (2015) 45(3):601–13. 10.1017/S003329171400172X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossain MM, Khan N, Sultana A, Ma P, McKyer ELJ, Ahmed HU, et al. Prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders among people with autism spectrum disorder: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112922. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rydzewska E, Dunn K, Cooper SA. Umbrella systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on comorbid physical conditions in people with autism spectrum disorder. Br J Psychiatry. (2021) 218(1):10–9. 10.1192/bjp.2020.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solmi M, Song M, Yon DK, Lee SW, Fombonne E, Kim MS, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of autism spectrum disorder from 1990 to 2019 across 204 countries. Mol Psychiatry. (2022) in press. 10.1038/s41380-022-01630-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GBD. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. (2020) 396(10258):1204–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. Country cooperation strategy guide 2020: Implementing the thirteenth general programme of work for driving impact in every country. Geneva: World Health Organization; (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017160 (Accessed 15 March, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 19.UN. Sustainable development goals. New York: United Nations; (2015). 2015. Available at: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwaigenbaum L, Penner M. Autism spectrum disorder: advances in diagnosis and evaluation. Br Med J. (2018) 361:k1674. 10.1136/bmj.k1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elsabbagh M. Linking risk factors and outcomes in autism spectrum disorder: is there evidence for resilience? Br Med J. (2020) 368:l6880. 10.1136/bmj.l6880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, Boerma JT, Collins GS, Ezzati M, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet. (2016) 388(10062):e19–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5 edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng Y, Li H, Wang M, Li N, Tian T, Wu Y, et al. Global burden of thyroid cancer from 1990 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3(6):e208759. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassebaum N, Kyu HH, Zoeckler L, Olsen HE, Thomas K, Pinho C, et al. Child and adolescent health from 1990 to 2015: findings from the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors 2015 study. JAMA Pediatr. (2017) 171(6):573–92. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiner RC, Jr., Olsen HE, Ikeda CT, Echko MM, Ballestreros KE, Manguerra H, et al. Diseases, injuries, and risk factors in child and adolescent health, 1990 to 2017: findings from the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors 2017 study. JAMA Pediatr. (2019) 173(6):e190337. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Z, Jiang Y, Yuan H, Fang Q, Cai N, Suo C, et al. The trends in incidence of primary liver cancer caused by specific etiologies: results from the global burden of disease study 2016 and implications for liver cancer prevention. J Hepatol. (2019) 70(4):674–83. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Song M. Visualizing a field of research: a methodology of systematic scientometric reviews. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14(10):e0223994. 10.1371/journal.pone.0223994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. (2013) 382(9904):1575–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyall K, Croen L, Daniels J, Fallin MD, Ladd-Acosta C, Lee BK, et al. The changing epidemiology of autism Spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Public Health. (2017) 38:81–102. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zablotsky B, Black LI, Maenner MJ, Schieve LA, Blumberg SJ. Estimated prevalence of autism and other developmental disabilities following questionnaire changes in the 2014 national health interview survey. Natl Health Stat Report. (2015) 87:1–20. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zablotsky B, Black LI, Maenner MJ, Schieve LA, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics. (2019) 144(4):e20190811. 10.1542/peds.2019-0811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beggiato A, Peyre H, Maruani A, Scheid I, Rastam M, Amsellem F, et al. Gender differences in autism spectrum disorders: divergence among specific core symptoms. Autism Res. (2017) 10(4):680–9. 10.1002/aur.1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferri SL, Abel T, Brodkin ES. Sex differences in autism Spectrum disorder: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2018) 20(2):9. 10.1007/s11920-018-0874-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Rooij D, Anagnostou E, Arango C, Auzias G, Behrmann M, Busatto GF, et al. Cortical and subcortical brain morphometry differences between patients with autism Spectrum disorder and healthy individuals across the lifespan: results from the ENIGMA ASD working group. Am J Psychiatry. (2018) 175(4):359–69. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17010100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw KA, McArthur D, Hughes MM, Bakian AV, Lee LC, Pettygrove S, et al. Progress and disparities in early identification of autism Spectrum disorder: autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 2002–2016. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021) 61(7):905–14. 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howlin P, Moss P. Adults with autism spectrum disorders. Can J Psychiatry . (2012) 57(5):275–83. 10.1177/070674371205700502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang X, Li R, Wong SHS, Sum RKW, Wang P, Yang B, et al. The effects of exercise interventions on executive functions in children and adolescents with autism Spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine. (2021) 52(1):75–88. 10.1007/s40279-021-01545-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masi A, DeMayo MM, Glozier N, Guastella AJ. An overview of autism Spectrum disorder, heterogeneity and treatment options. Neurosci Bull. (2017) 33(2):183–93. 10.1007/s12264-017-0100-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Someki F, Torii M, Brooks PJ, Koeda T, Gillespie-Lynch K. Stigma associated with autism among college students in Japan and the United States: an online training study. Res Dev Disabil. (2018) 76:88–98. 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernier R, Mao A, Yen J. Psychopathology, families, and culture: autism. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2010) 19(4):855–67. 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bölte S, Girdler S, Marschik PB. The contribution of environmental exposure to the etiology of autism spectrum disorder. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2019) 76(7):1275–97. 10.1007/s00018-018-2988-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson-Agramonte MLA, Noris García E, Fraga Guerra J, Vega Hurtado Y, Antonucci N, Semprún-Hernández N, et al. Immune dysregulation in autism Spectrum disorder: what do we know about it? Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23(6):3033. 10.3390/ijms23063033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vuong HE, Hsiao EY. Emerging roles for the gut microbiome in autism Spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry. (2017) 81(5):411–23. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paulsen B, Velasco S, Kedaigle AJ, Pigoni M, Quadrato G, Deo AJ, et al. Autism genes converge on asynchronous development of shared neuron classes. Nature. (2022) 602(7896):268–73. 10.1038/s41586-021-04358-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matelski L, Van de Water J. Risk factors in autism: thinking outside the brain. J Autoimmun. (2016) 67:1–7. 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lord C, Bishop SL. Recent advances in autism research as reflected in DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2015) 11:53–70. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.