Abstract

Inflammatory processes are essential for innate immunity and contribute to carcinogenesis in various malignancies, such as colorectal cancer, esophageal cancer and lung cancer. Pharmacotherapies targeting inflammation have the potential to reduce the risk of carcinogenesis and improve therapeutic efficacy of existing anti-cancer treatment. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), comprising a variety of structurally different chemicals that can inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes and other COX-independent pathways, are originally used to treat inflammatory diseases, but their preventive and therapeutic potential for cancers have also attracted researchers’ attention. Pharmacogenomic variability, including distinct genetic characteristics among different patients, can significantly affect pharmacokinetics and effectiveness of NSAIDs, which might determine the preventive or therapeutic success for cancer patients. Hence, a more comprehensive understanding in pharmacogenomic characteristics of NSAIDs and cancer-related inflammation would provide new insights into this appealing strategy. In this review, the up-to-date advances in clinical and experimental researches targeting cancer-related inflammation with NSAIDs are presented, and the potential of pharmacogenomics are discussed as well.

Keywords: cancer, inflammation, cyclooxygenase, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pharmacogenomics

Introduction

As a fundamental innate immune response, inflammation is involved in tissue repair, defending against pathogens and other danger signals. Transient and well-organized inflammation is salutary while chronic inflammation has been proved to be related to the development of different malignancies (Grivennikov et al., 2010; Elinav et al., 2013; Greten and Grivennikov, 2019). Chronic inflammation can be evoked by both infectious and non-infectious processes of chronic injury or irritation, especially in organs exposed to the external environment (Ulrich et al., 2006). Besides, cancer-intrinsic and therapy-induced metabolic changes, cell stress and cell death are also important sources of cancer-associated inflammation (Hou et al., 2021). Chronic inflammation is regarded as an aberrantly prolonged immune response which results in epigenetic alterations that drive cancer initiation and progression, as well as the accumulation of growth factors that support the development of nascent cancer (Hou et al., 2021). Continuous production of various inflammatory molecules (cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins, etc.) and recruitment of inflammatory cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME) promote tumor progression, metastasis and even therapy resistance (Greten and Grivennikov, 2019; Wang D. et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2021).

Preclinical and epidemiological evidences suggest that agents with anti-inflammatory effect, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), have the potential to prevent or delay cancer initiation and improve therapeutic efficacy of cytotoxic agents, targeted agents and immune checkpoint inhibitors (Crusz and Balkwill, 2015). NSAIDs comprise a group of structurally diverse chemicals that can reduce the synthesis of prostaglandins by inhibiting the activity of the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes and other COX-independent pathways. The expression level of COX-2, an inducible isoform of the COX enzyme family, has been found elevated in breast cancer, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, bladder cancer and so on (Hashemi Goradel et al., 2019). Aspirin, one of the most classical NSAIDs, has been proved to be associated with decreased incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer (Li et al., 2015; Wang L. et al., 2021). Defined as pharmacological intervention to prevent or delay the process of carcinogenesis, cancer chemoprevention is now considered a practicable approach, especially with NSAIDs. In patients diagnosed with malignancies, concurrent use of NSAIDs with cytotoxic agents, targeted agents or immune checkpoint inhibitors seems to be hopeful as well (Edelman et al., 2008; Cortellini et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020).

Despite the promising anti-cancer effects of NSAIDs, their treatment response varies among patients for many reasons, particularly because of inter-individual genetic differences of specific genes that are involved in drug metabolism or drug-induced signal transduction, and certain genetic variations have a significant impact on pharmacokinetics and effectiveness of specific drugs (Ulrich et al., 2006). Accordingly, the study of variations of genetic characteristics related to drug response is defined as pharmacogenomics (Roden et al., 2019). For instance, carriers of specific NF-κB variants might benefit from NSAIDs in cancer chemoprevention (Chang et al., 2009; Seufert et al., 2013). Therefore, taking account of relevant pharmacogenomic differences makes it possible to enhance the chemopreventive and therapeutic potential of NSAIDs in the treatment of malignancies.

In this article, we summarized general concept of inflammation and cancer development, and then highlighted advances in NSAID-targeted pro-cancer mechanisms involved in this process. The distinct results of clinical studies in chemoprevention and treatment of cancer with NSAIDs were presented and discussed as well. Furthermore, NSAID metabolism and its anti-cancer mechanisms, as well as related pharmacogenomic characteristics, were demonstrated. Factors affecting the effectiveness or risk of NSAIDs other than pharmacogenomic features were also mentioned.

Inflammation and cancer development

Inflammation is a defensive response against infection and tissue injury, which can constrain the spread of pathogens or facilitate tissue repair. In the initiation of inflammation, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) expressed by pathogens or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) produced in sterile tissue injury or infection-related cell damage can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which are generally expressed by innate immune cells, such as mast cells, tissue macrophages and dendritic cells (Zhao et al., 2021). Then these innate immune cells activate signal transduction pathways that promote the antimicrobial or proinflammatory functions, including secreting proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines and vasoactive amines (Zindel and Kubes, 2020). As a consequence, leukocytes and plasma proteins involved in innate immunity are recruited to sites of infection or tissue injury, where they start to eliminate microbes or cell debris and repair damaged tissue in a well-orchestrated way (Zindel and Kubes, 2020). Actually, when inflammatory cell recruitment reaches its peak, it is typically followed by clearance of these cells and the restoration of tissue homeostasis, and this process is known as resolution (Fullerton and Gilroy, 2016). However, if the proinflammatory stimulus is not eliminated during the acute phase of inflammation within several days or weeks, it will lead to incomplete or frustrated resolution and then develop into chronic inflammation, which has been proved to be associated with an increased risk for cancer (Grivennikov et al., 2010; Fullerton and Gilroy, 2016; Zhao et al., 2021).

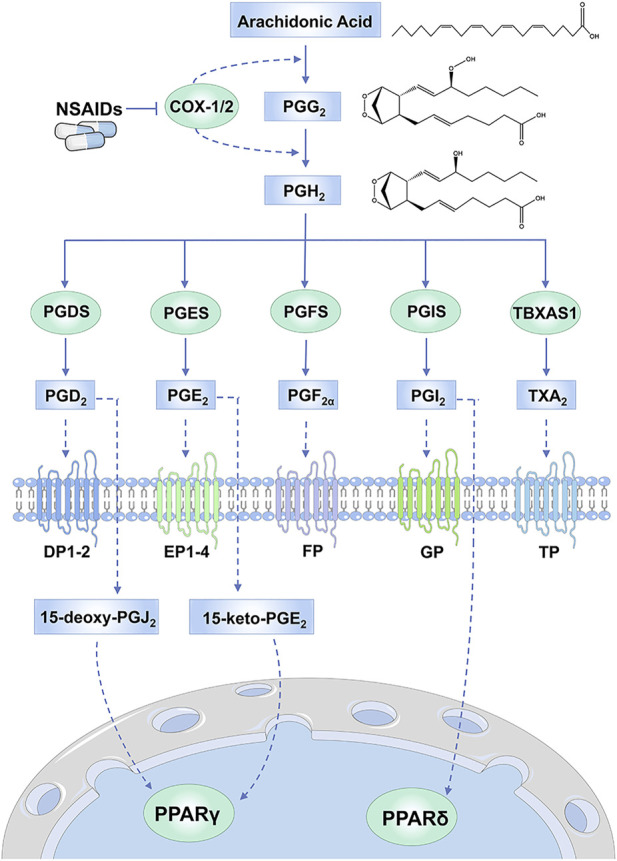

During acute and chronic inflammation, the expression levels of proinflammatory molecules are upregulated, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon (IFN) γ, which are able to induce the synthesis of various eicosanoids, including prostaglandins (Aoki and Narumiya, 2012; Wang B. et al., 2021). Prostaglandins (PGs, including PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2 and thromboxane A2) are synthesized from arachidonic acid by cyclooxygenase (COX), whose Human Genome Organization name is prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase (Aoki and Narumiya, 2012; Wang D. et al., 2021). There are two COX isoforms: COX-1 (PTGS1) and COX-2 (PTGS1). COX-1 is constitutively expressed in most tissues, where it plays a role in maintaining tissue homeostasis by providing basal levels of prostaglandins (Wang B. et al., 2021). By contrast, COX-2 usually has limited expression in normal tissues, but it is highly inducible in response to IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ, especially at sites of inflammation and during tumor progression (Hashemi Goradel et al., 2019). Both COX isoforms can transform arachidonic acid into prostaglandin G2 (PGG2) and, subsequently, into PGH2, which is finally converted into various prostaglandins via specific synthases ( Figure 1 ). Prostaglandins then exert their actions by activating G-protein-coupled receptors on the cell surface, including the PGD2 receptors (DP1 and DP2), the PGE2 receptors (EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4), the PGF2α receptor (FP), the PGI2 receptor (IP) and the thromboxane A2 receptor (TP) (Funk, 2001). In some cases, nuclear receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) can also be activated by certain prostaglandins or their metabolites (Wang and Dubois, 2010).

FIGURE 1.

Synthetic and signal transduction pathways of prostaglandins. Arachidonic acid can be transformed into PGG2 and PGH2 via COX enzymes, which can be inhibited by NSAIDs. Then PGH2 is converted into various prostaglandins via specific synthases. Prostaglandins then exert their actions by activating receptors on cell membranes, including DP1-2, EP1-4, FP, IP and TP. Nuclear receptors such as PPARγ and PPARδ can also be activated by prostaglandins or their metabolites. Abbreviations: PGG2, prostaglandin G2; PGH2, prostaglandin H2; PGDS, PGD synthase; PGES, PGE synthase; PGFS, PGF synthase; PGIS, PGI synthase; TBXAS1, TXA synthase; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR).

Constant exposure to proinflammatory stimulus, whether it is infectious or non-infectious, is responsible for the overexpression of COX-2 and development of chronic inflammation, which might lead to malignancies, such as hepatitis virus infection-related hepatocellular carcinoma (Lu et al., 2015), reflux esophagitis-related esophageal cancer (Yang et al., 2012) and inflammatory bowel disease-related (IBD) colorectal cancer (Ullman and Itzkowitz, 2011). Previous research demonstrated that COX-2 achieved cancer-promoting effects mainly by its downstream prostaglandins, which contributed to cancer initiation, progression and resistance to treatment (Hashemi Goradel et al., 2019; Hou et al., 2021). COX-2 can be expressed by cancer cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and regulatory T (Treg) cells (Hashemi Goradel et al., 2019). The upregulated expression of COX-2 has been observed in numerous premalignant and malignant diseases, including colorectal adenoma, Barrett’s esophagus, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, glioblastoma and so on (Wang and Dubois, 2006; Jiang et al., 2017; Wang D. et al., 2021). It is generally accepted that COX-2 contributes to carcinogenesis mainly via overproducing prostaglandins, especially PGE2.

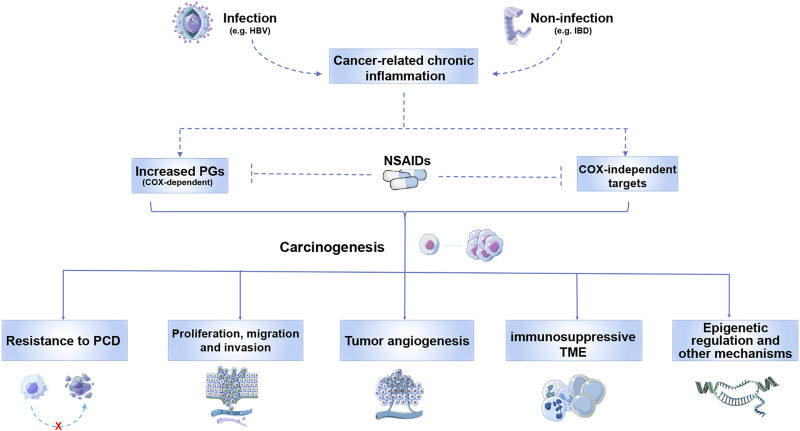

Besides COX enzymes, NSAIDs exert their function through COX-independent pathways as well. Several mechanisms have been proposed to demonstrate the tumor-promoting effects of NSAID-targeted signals, which are summarized as follows ( Figure 2 ). Overproduction of PGE2 in tumor tissues usually results in resistance to apoptosis of cancer cell, as well as enhanced ability in proliferation, migration and invasion (Wang and Dubois, 2010; Lee et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2021). Besides, PGE2 promotes angiogenesis in cancer development (Zhang and Daaka, 2011; Xu et al., 2014). Generation of immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) by regulating tumor-infiltrating immune cells is also achieved by PGE2, which includes stimulating type-2 macrophage polarization, inducing T cell dysfunction and preventing tumor infiltration of dendritic cells or cytotoxic T lymphocytes (Ahmadi et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2022). The emergence of cancer stem cells (CSCs) is related to different PGE2-related signaling pathways as well (Li et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Fang et al., 2017). Aspirin could promote apoptosis in CSCs in a COX-independent pathway (Chen et al., 2018). In addition, epigenetic regulation such as DNA methylation of tumor suppressive genes induced by PGE2 promotes cancer development (Xia et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2019). Except for PGE2, thromboxane A2, another COX-2 derived production, was reported to be related to enhanced tumor angiogenesis (Pradono et al., 2002). Whereas abundant evidences suggested contribution of COX-2 in various cancers, the role for COX-1 in cancer development remains much less discovered. Several studies showed that COX-1-dependent pathways was required for carcinogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis in certain malignancies as well (Daikoku et al., 2005; Li et al., 2014; Lucotti et al., 2019).

FIGURE 2.

Tumor-promoting inflammation-related signals that can be targeted by NSAIDs. Both infectious and non-infectious chronic inflammation contributes to carcinogenesis via increasing PGs and activating COX-independent signals that can be suppressed by NSAIDs. These COX-dependent and independent pathways promote cancer development by inducing resistance to PCD, and facilitating proliferation, migration and invasion. Induction of tumor angiogenesis, immunosuppressive TME and other mechanisms are also achieved by NSAID-targeted signals. Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PGs, prostaglandins; PCD, programmed cell death; TME, tumor microenvironment.

Clinical outcomes of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in treating cancer-related inflammation

NSAIDs constitute a group of drugs with diverse chemical structure, which share a common mechanism of action by inhibiting COX activity and COX-independent pathways. Generally, all NSAIDs compete with arachidonate for the COX active site, which results in decreased production of prostaglandins. Now that COX enzymes and prostaglandins have been proved to be significantly related to cancer development, the application of NSAIDs becomes a promising strategy for the treatment of inflammation-driven cancers. The most commonly used NSAIDs and their clinical trials in chemoprevention or post-diagnosis use are listed in Table 1, and participants in chemoprevention trials were mostly with higher cancer risks.

TABLE 1.

Classification, selectivity and anti-cancer clinical trials of classical NSAIDs.

| Family/Class | Drug | Selectivity for COXs | Clinical trials in cancer prevention or treatment with NSAIDs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemoprevention | Post-diagnosis treatment | |||

| Salicylates | Aspirin | COX-1 and COX-2 | Effective: esophageal adenocarcinoma, CRC Ineffective: breast cancer, lung cancer Unpublished results: melanoma, oral cancer | Effective: CRC, breast cancer |

| Unpublished results: prostate cancer, melanoma | ||||

| Diflunisal | COX-2 selective | None | None | |

| Acetic acid derivatives | Indomethacin | COX-1 and COX-2 | None | Unpublished results: CRC, esophageal cancer, ovarian cancer, melanoma |

| Sulindac | COX-1 and COX-2 | Effective: colorectal adenoma Ineffective: lung cancer Unpublished results: oral cancer, melanoma | Effective: breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; Unpublished results: melanoma | |

| Diclofenac | COX-2 selective | None | Unpublished results: basal cell carcinoma | |

| Etodolac | COX-2 selective | None | None | |

| Propionic acid derivatives | Ibuprofen | COX-1 and COX-2 | None | None |

| Flurbiprofen | COX-1 selective | None | None | |

| Naproxen | COX-1 and COX-2 | Effective: CRC | None | |

| Enolic acid derivatives | Piroxicam | COX-1 and COX-2 | None | None |

| Meloxicam | COX-2 selective | None | Effective: multiple myeloma | |

| Diaryl heterocyclic compounds | Celecoxib | COX-2 selective | Effective: breast cancer, colorectal adenoma Ineffective: esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, oral cancer Unpublished results: NSCLC, CRC | Effective: ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, head and neck cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, CRC Ineffective: breast cancer, NSCLC, esophageal cancer, prostate cancer, thyroid cancer, pancreatic cancer Unpublished results: bladder cancer, kidney cancer, oral cancer |

| Rofecoxib | COX-2 selective | Effective: colorectal adenoma Unpublished results: prostate cancer | Effective: NSCLC Ineffective: CRC | |

*Information resource: https://clinicaltrials.gov Reported trials in this table are restricted to completed interventional studies. Abbreviations: COX, cyclooxygenase; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; CRC, colorectal cancer; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

Chemoprevention strategies with NSAIDs have the potential to reduce incidence of several malignancies. Aspirin, one of the most widely used NSAIDs, has been identified as an effective cancer-preventive agent according to numerous epidemiological and clinical studies (Hou et al., 2021). A meta-analysis of 42 observational studies (99,769 cases) suggested an association between aspirin use and reduced incidence of breast cancer (Ma S. et al., 2021). Another meta-analysis based on individual-level data from nine cohort studies (2,600 cases) and 8 case-control studies (5,726 cases) identified a lower ovarian cancer risk associated with frequent aspirin use (Hurwitz et al., 2022). Likewise, the frequency of aspirin use was also emphasized by a meta-analysis in endometrial cancer (7 case-control and 11 cohort studies included, 14,766 cases in total), where the reduced cancer risk was closely related to the high-frequency of aspirin use instead of the duration of use (Wang et al., 2020). In addition to the frequency and duration of aspirin use, dose-effect relationship is a critical issue as well. A meta-analysis focusing on dose-effect relationship between aspirin and cancer risk revealed that high frequency or high dose use of aspirin might increase lung and prostate cancer risks, while low-dose of aspirin use could prevent colorectal cancer (Wang L. et al., 2021). Contrarily, a meta-analysis in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (2 case-control and 16 cohort studies included) showed that the use of aspirin was associated with a lower risk of liver cancer, but not in a dose-dependent or a duration-dependent relationship (Wang et al., 2022). Interestingly, the meta-analysis in HCC concluded that aspirin had protective effects against HCC in patients with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection (Wang et al., 2022), which was also supported by a nationwide study of patients with chronic viral hepatitis in Sweden (Simon et al., 2020). Moreover, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis of all observational studies on aspirin use and digestive-tract cancers up to March 2019, aspirin use was related to lower risks in various digestive malignancies, including colorectal cancer (45 studies), squamous-cell esophageal cancer (13 studies), adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia (10 studies), stomach cancer (14 studies), hepatobiliary cancer (5 studies) and pancreatic cancer (15 studies) (Bosetti et al., 2020). However, the findings of two large cohort studies didn’t support that aspirin use was associated with reduced pancreatic cancer risk, except in patients with diabetes (Khalaf et al., 2018). Despite the satisfactory chemoprevention effect of aspirin, it is noteworthy that prophylactic use of NSAIDs should be cautious with different populations. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (9,525 cases receiving aspirin and 9,589 cases receiving placebo) reported that older adults taking daily low-dose aspirin (100 mg) led to an increase in all-cause mortality, primarily due to cancer, and the follow-up data of this trial suggested that aspirin might accelerate the progression of cancer in older adults (McNeil et al., 2018; McNeil et al., 2021). COX-2 selective inhibitors like celecoxib and etodolac also have been proved to be efficient in chemoprevention for non-melanoma skin cancers and gastric cancer (Elmets et al., 2010; Yanaoka et al., 2010). Unlike generally accepted conclusion on the benefit of aspirin in preventing colorectal cancer, it is still questionable whether NSAIDs can reduce cancer risks in certain malignancies. For instance, lung cancer, one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths, was proved to be of little association between its incidence and aspirin use according to different well-designed studies (Oh et al., 2011; Mc Menamin Ú et al., 2015; Loomans-Kropp et al., 2021). In hematologic malignancies, high use (≥4 days/week for ≥4 years) of acetaminophen was associated with increased incidence of myeloid neoplasms and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (Walter et al., 2011).

In addition to prophylactic use as chemoprevention strategies, NSAIDs can also improve the survival in patients who are already diagnosed with certain malignancies, which is supported by numerous observational studies and clinical trials. Post-diagnosis regular aspirin use was associated with reduced colorectal cancer-specific and overall mortality, especially in patients with positive PTGS2 (COX-2) expression and mutated PIK3CA tumors, reported by a meta-analysis (Li et al., 2015). Further studies revealed that, among colorectal cancer patients with low tumoral levels of PD- L1, survival benefit from post-diagnosis aspirin use was greater than in others (Domingo et al., 2013; Hamada et al., 2017). Another prospective cohort study of newly diagnosed biliary tract cancer (BTC) found that post-diagnosis aspirin use was associated with decreased BTC-specific mortality of different subtypes (Liao et al., 2021). In a cohort study of prostate cancer, similar results were observed in patients with high-risk cancers (≥T3 and/or Gleason score ≥8), where postdiagnosis daily aspirin use was associated with lower prostate cancer-specific mortality (Jacobs et al., 2014). In patients with esophageal, hepatobiliary and breast cancer, post-diagnosis use of aspirin was associated with increased survival as well (Fraser et al., 2014; Frouws et al., 2017).

Some clinical proofs supported that cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy or chemotherapy may benefit from additional use of NSAIDs. In prostate cancer patients treated with radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy, aspirin use was associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality, especially in patients with high-risk disease (Choe et al., 2012). In pre-treated metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, aspirin improved overall survival significantly (Giampieri et al., 2017). In advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with COX-2 expression undergoing chemotherapy, who received celecoxib had better survival than that in non-users, according to a randomized clinical trial (Edelman et al., 2008). Aspirin could also decrease the proangiogenic effects of tamoxifen (a selective endocrine receptor modulator) in breast cancer patients, which suggested that antiplatelet or antiangiogenic therapy might improve the effectiveness of tamoxifen in breast cancer treatment (Holmes et al., 2008). In postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors, sulindac, a non-selective NSAID, reduced breast density, which is a risk factor for breast cancer, and the results implied that PGE2 inhibition by NSAIDs might be important for breast density change or collagen modulation during breast cancer development (Thompson et al., 2021). However, the benefit of NSAIDs in patients undergoing chemotherapy is not always satisfactory in certain cancer types or populations. In a randomized clinical trial of stage III colon cancer, additional celecoxib to standard adjuvant chemotherapy for 3 years did not significantly improve disease-free survival of the included patients, compared with patients receiving placebo (Meyerhardt et al., 2021). Similar results were reported by a trial in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer, where additional rofecoxib did not prolong the survival of patients receiving standard chemotherapy (Gridelli et al., 2007). In breast cancer patients receiving aromatase inhibitor treatment, short-term (≤18 months) celecoxib or low-dose aspirin use did not improve event-free survival or distant disease-free survival, and low-dose aspirin use even increased all-cause mortality (Strasser-Weippl et al., 2018).

The emergence of targeted therapies and immunotherapies has successfully prolonged overall survival for all kinds of cancer patients, and the use of NSAIDs along with targeted agents or immune checkpoint inhibitors seems promising. A retrospective analysis in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant (EGFR) NSCLC patients suggested that concurrent aspirin use with osimertinib (EGFR inhibitor) was associated with prolonged progression-free survival (Liu et al., 2020), and a similar result was also reported in NSCLC (Han et al., 2020). In advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving sorafenib or regorafenib (multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitors), concomitant use of aspirin improved their survival (Casadei-Gardini et al., 2021). A multicenter retrospective study showed that aspirin use was independently related to an increased objective response rate among 1012 cancer patients (52.2% NSCLC, 26% melanoma, 18.3% renal cell carcinoma and 3.6% others) treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (Cortellini et al., 2020), and a meta-analysis reported that concurrent use of low-dose aspirin was associated with better progression-free survival in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors, including NSCLC (Zhang et al., 2021). Nevertheless, some studies revealed that NSAIDs did not benefit certain patients receiving targeted therapy or immunotherapy. In platinum refractory NSCLC patients, the combination of celecoxib and gefitinib (EGFR inhibitor) did not improve the response rate compared with gefitinib alone (Gadgeel et al., 2007). Immunotherapy with antibodies targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) usually results in enterocolitis, and melanoma patients with anti-CTLA-4 enterocolitis took NSAIDs more frequently than patients without enterocolitis, which suggested that patients treated with anti-CTLA-4 were supposed to avoid NSAIDs (Marthey et al., 2016). In addition, concurrent use of immune checkpoint inhibitors and aspirin or NSAIDs did not improve disease control or survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients, and use of NSAIDs was even associated with a higher risk of progression and death (Zhang et al., 2022).

Drug metabolism, anti-cancer mechanisms and pharmacogenomics of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Pharmacogenomics in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug metabolism

The effectiveness of NSAIDs in cancer chemoprevention and post-diagnosis therapies varies in distinct populations and cancer types, primarily due to diverse genetic characteristics among different malignancies and individuals. The genetic variation of specific genes that are involved in drug metabolism or drug-induced signal transduction might affect the success of chemoprevention or treatment with NSAIDs (Scherer et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015). Taking account of such relevant pharmacogenomic differences has the potential to modify chemopreventive and therapeutic effects of NSAIDs.

Most NSAIDs are administered as active drugs, but some of them are prodrugs that require metabolic activation, such as sulindac. Several metabolic pathways are responsible for inactivation and elimination of NSAIDs, including oxidation (cytochrome P450 enzymes, CYP) and glucuronide conjugation (uridine-5′-diphosphate-glucuronosyl transferases, UGTs). The pharmacokinetic properties of NSAIDs vary among different individuals, partly because of their variance in NSAID metabolism-related genes, which affects plasma concentration and half-life of NSAIDs (Theken et al., 2020). CYP2C9 (cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily C, polypeptide 9) is one of the most important enzymes for the oxidation of NSAIDs as well as other CYP enzymes, especially the CYP2C family (Theken et al., 2020). Besides, glucuronidation through UGTs is also an important pathway for NSAIDs clearance. UGT1A1, UGT1A6, UGT1A7, and UGT1A9 contribute most to aspirin glucuronidation, while the most important enzymes involved in non-aspirin NSAID glucuronidation are other members of the UGT family (Ulrich et al., 2006).

CYP2C enzymes and UGTs are highly polymorphic, and genetic variation of these genes plays a role in the inter-individual variability in NSAID elimination and efficacy. More than 60 variant alleles or multiple sub-alleles of CYP2C9 have been found, which can be categorized according to their functional status as follows: normal function (e.g., CYP2C9*1), decreased function (e.g., CYP2C9*2 and *5), and no function (e.g., CYP2C9*3 and *6) (Theken et al., 2020). Previous researches demonstrated that functional polymorphisms of CYP2C9 and UGT1A6 were related to modified effects of NSAIDs in the chemoprevention of colorectal adenoma and cancer (Bigler et al., 2001; Chan et al., 2005; Samowitz et al., 2006; Chan et al., 2009; Yamazaki et al., 2021). In addition, other functionally relevant polymorphisms of UTGs were also associated with modification of NSAID effectiveness on colorectal cancer risk (Angstadt et al., 2014; Scherer et al., 2014). These inspiring findings emphasize the need for further pharmacogenomic researches to identify individuals that might benefit from NSAIDs in cancer chemoprevention.

Anti-cancer mechanisms and pharmacogenomics of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

According to classical theories, NSAIDs exert their anti-cancer effects mainly based on COX-dependent mechanisms via inhibiting COX-2 activity and prostaglandin production. Nevertheless, emerging evidences presented some novel targets in COX-independent anti-tumor effects, where NSAIDs directly interacted with proteins other than COX enzymes. COX-independent molecular targets are summarized in Table 2. Pharmacogenetic studies have demonstrated that genetic variation is one of the leading causes of variability in drug response. Among different types of genetic variations that affect inter-individual drug response, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) play a critical role due to their occurrence frequency of >1% in the human population (Gholamian Dehkordi et al., 2021). Because different NSAIDs have various molecular targets, including the most classical COX enzymes and COX-independent molecules, genetic variations in these genes and their closely related upstream or downstream genes can be tremendous. Therefore, identification of certain determining pharmacogenomic features is critical for predicting drug response and select eligible patients to receive NSAIDs along with standard anti-cancer treatment. For instance, aspirin use was associated with reduced rate of colorectal cancer recurrence in patients with PIK3CA-mutant tumors compared with patients with PIK3CA wild-type tumors (Domingo et al., 2013). Therefore, PIK3CA mutations could be regarded as an effective pharmacogenomic feature in predicting aspirin effectiveness in colorectal cancer patients.

TABLE 2.

COX-independent molecular targets of NSAIDs.

| Targets | Effects of NSAIDs | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear receptors | PPAR-γ | Stimulation of PPAR-γ; inhibition of cancer cell growth and enhancement of cell migration | Wick et al. (2002); Babbar et al. (2003); Kato et al. (2011) |

| PPAR-δ | Inhibition of PPAR-δ; induction of cancer cell apoptosis | He et al. (1999); Liou et al. (2007) | |

| RXRα | Inhibition of RXRα, induction of cancer cell apoptosis | Kolluri et al. (2005); Zhou et al. (2010) | |

| Transcription factors | NF-κB | Inhibition of NF-κB; suppression of cancer proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis | Shishodia and Aggarwal, (2004); Feng et al. (2007); Liao et al. (2015) |

| AP-1 | Inhibition of AP-1; suppression of malignant transformation induced by tumor promotor | Dong et al. (1997); Liu et al. (2003) | |

| Sp1 | Inhibition of Sp1; suppression of tumor angiogenesis | Wei et al. (2004) | |

| Kinases | AMPK/mTOR | Activation of AMPK and inhibition of mTOR; induction of autophagy in cancer cells | Din et al. (2012); Hawley et al. (2012) |

| PDPK-1 | Inhibition of PDPK-1; suppression of tumor proliferation and induction of apoptosis | Arico et al. (2002); Kulp et al. (2004) | |

| Others | PDE5 | Inhibition of PDE5; suppression of tumor cell growth and induction of apoptosis | Tinsley et al. (2009); Tinsley et al. (2010) |

| SERCA | Inhibition of SERCA; induction of cancer cell apoptosis | Johnson et al. (2002); White et al. (2013) | |

| Histone acetyltransferase p300 | Interaction with p300; induction of CSC apoptosis and suppression of tumor progression | Chen et al. (2018) | |

Accumulating proofs suggested that NSAIDs were capable of suppressing proliferation, migration and invasion in cancer cells and promoting their programmed cell death. Selecting patients with potential benefits based on their pharmacogenomic characteristics was also supported by some evidences. Various NSAIDs suppressed NF-κB-regulated COX-2 expression in a dose-dependent manner and inhibited the proliferation of tumor cells (Takada et al., 2004). Inhibition of NF-κB pathway induced by aspirin suppressed the growth, migration and metastasis of osteosarcoma (Liao et al., 2015). NF-κB polymorphisms had an impact on cancer risks, and carriers of specific NF-κB variants might benefit from NSAIDs in cancer chemoprevention (Chang et al., 2009; Seufert et al., 2013). In addition to NF-κB, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways can be affected by NSAIDs as well. Aspirin suppressed mTORC1 signaling and the PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK pathways, and it showed synergetic anti-cancer efficacy in combination with sorafenib in hepatocarcinoma cells (Sun et al., 2017). By inhibiting AKT/mTOR signaling, aspirin also promoted RSL3-induced ferroptosis in PIK3CA-mutant colorectal cancer cells (Chen et al., 2022). In hepatocellular carcinoma, celecoxib acted synergistically with chemotherapeutic drugs in promoting apoptosis, and celecoxib induced COX-2 inhibition in different apoptotic pathways, including stimulating death receptor signaling, activation of caspases and mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (Kern et al., 2006). Combined use of celecoxib and erlotinib (EGFR inhibitor) also suppressed prostaglandin signaling and promoted apoptosis of intestinal tumors in vivo (Buchanan et al., 2007). Aspirin even triggered disruption of the chromosomal architecture of the COX-2 locus in lung cancer cells during radiation treatment and increased the level of apoptosis (Sun et al., 2018). In lymphoma B cells, celecoxib enhanced the apoptotic activity of TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) through COX-2-independent effects via decelerating the cell cycle and inhibiting expression of survival proteins, like Mcl-1 (Gallouet et al., 2014). Similar targets were verified in colon cancer cells, where combined use of aspirin with sorafenib suppressed proliferation by targeting the anti-apoptotic proteins FLIP and Mcl-1 and sensitized cancer cells to TRAIL (Pennarun et al., 2013). Sulindac could also induce apoptosis by binding to retinoid X receptor-alpha rather than COX, which inhibited TNFα induced PI3K/AKT signaling and activated the death receptor-mediated apoptotic pathway (Zhou et al., 2010). The combination of aspirin and osimertinib inhibited AKT/FOXO3a signaling component phosphorylation and increased Bim expression in osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cells and promoted Bim-dependent apoptosis, which decreased tumor growth in vivo (Han et al., 2020).

Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis is also a significant function of NSAIDs. PGE2-EP3 signaling induced tumor metastasis and angiogenesis by upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), which could be suppressed by NSAIDs (Amano et al., 2009). Another study proved that PGE2 biosynthesis was dependent on COX-1 rather than COX-2 in endothelial cells, which could be blocked by aspirin in vivo (Salvado et al., 2013). Overexpression of COX-2 stimulated the expression of angiogenic-related genes in breast cancer cells isolated from COX-2 transgenic mice, and treatment with celecoxib suppressed tumor growth and micro-vessel density (Chang et al., 2004). Vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) have been identified as major mediators of tumor angiogenesis, and aspirin decreased serum level of VEGF and suppressed the pro-angiogenic effects of tamoxifen in breast cancer patients, where interindividual variability was noted by the researchers (Holmes et al., 2008). Genetic variations in VEGF-A and its receptors 1 (FLT1) and 2 (KDR) were proved to be associated with colon cancer survival, and the association could be modified by NSAID use, which indicated that cancer patients with specific SNPs in these genes could benefit more from NSAIDs (Slattery et al., 2014). In patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (CIN 3), serum VEGF levels were helpful to identify patients who may benefit from celecoxib, which provided novel strategies to cervical cancer chemoprevention (Rader et al., 2017). These results implied the existence of undiscovered pharmacogenomic features related to anti-angiogenesis effects of NSAIDs in cancer treatment.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) play an important role in cancer recurrence, metastasis and resistance to drugs, and NSAIDs can reduce cancer stem cells according to some researches. In colorectal cancer, NSAIDs (indomethacin, sulindac, aspirin and celecoxib) could inhibit the formation of CSCs and reduce chemotherapy-induced CSCs via inhibiting COX-2 and NOTCH/HES1, and activating PPARγ (Moon et al., 2014). Chemotherapeutic drugs could generate CSCs through an NFκB-IL6-dependent inflammatory environment and result in multidrug resistance in breast cancer, but treatment with aspirin was able to disturb the nuclear translocation of NF-κB in CSCs and improve sensitivity to chemotherapy (Saha et al., 2016). Aspirin could eliminate colorectal CSCs in a COX-independent pathway, where aspirin directly interacted with histone acetyltransferase p300, promoted H3K9 acetylation, activated FasL expression, and resulted in apoptosis in CSCs (Chen et al., 2018).

NSAIDs can also affect the epigenetic regulation of certain genetic loci, which results in anti-cancer effects. Aspirin could reduce histone demethylase (KDM6A/B) expression and suppress the expression of inflammation-related stemness genes (especially ICAM3), and inhibit tumor growth and metastasis (Zhang et al., 2020). A population-based study revealed that aspirin users with unmethylated promotor of BRCA1 and global hypermethylation of long interspersed elements-1 (LINE-1) had lower breast cancer-specific mortality (Wang et al., 2019). This study provided important pharmacogenetic evidence, which implied that epigenetic features of specific susceptibility genes should be taken into consideration before NSAID use.

Evidences showed that the regulation of immune cells in TME was achieved by NSAIDs as well. A prospective cohort study showed that regular aspirin use was related to a lower risk of colorectal carcinomas with low concentrations of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), which implied that aspirin contributed to the increased TILs in tumor tissues (Cao et al., 2016). Inhibition of the COX-2/PGE2/EP4 axis increased tumor-infiltrating immune cells in the microenvironment and restored sensitivity of drug-resistant tumor to pembrolizumab (Pi et al., 2022). The risk of developing breast cancer can be increased by radiotherapy for existing malignancies, post-irradiation use of low-dose aspirin for 6 months in mice could prevent the establishment of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, which was characterized by enriched proinflammatory factors and abundant myeloid cells, and aspirin intervention signiflcantly decreased COX-2 and TGFβ intensity in tumors from irradiated hosts (Ma L. et al., 2021).

In addition to the well-known focus on cancer proliferation, programmed cell death, angiogenesis, stemness, epigenetic regulation and immune regulation, other mechanical and clinical researches revealed some promising pharmacogenomic features as well. A large-scale case-control study showed that NSAID use was associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer, and the association varied according to genetic variation at two SNPs at chromosomes 12 and 15 (Nan et al., 2015). Tumor repopulation is a major cause of radiotherapy failure, and pancreatic cancer repopulation upon radiation was suppressed by aspirin in vitro and in vivo via inhibiting dying tumor cells from releasing exosomes and PGE2, which were critical for the survival and proliferation of tumor repopulation cells (Jiang et al., 2020). This study suggested that pancreatic cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy might benefit from combined use of aspirin. A study proved that tumor sensitivity to radiotherapy was enhanced by four tested NSAIDs (diclofenac, indomethacin, piroxicam and NS-398) via increasing tumor oxygenation, which was primarily mediated by an effect on mitochondrial respiration (Crokart et al., 2005). In lung cancer, aspirin caused disruption of the chromosomal architecture in the COX-2 locus and reduced its production in cell lines, which enhanced radiosensitivity of lung cancer cells (Sun et al., 2018).

Considerable amounts of studies demonstrated the effectiveness of NSAIDs in chemoprevention and post cancer-diagnosis use in certain cancer types, but there is still requirement for more researches in comprehensively clarifying the underlying anti-cancer mechanisms of NSAIDs, as well as exploring more pharmacogenomic features to guide personalized chemoprevention and treatment.

Conclusion and future directions

Chronic inflammation results in upregulation of proinflammatory molecules, recruitment of inflammatory cells, genetic and epigenetic alterations in normal cells, thus initiating carcinogenesis and cancer development. NSAIDs are capable of suppressing various aberrantly activated genes during inflammation and cancer progression, including the most classical COX enzymes and other COX-independent pro-cancer genes. Numerous epidemiological, clinical and mechanical researches revealed the effectiveness of NSAIDs in chemoprevention and post cancer-diagnosis treatment in both solid tumors and hematological malignancies. However, NSAIDs do not benefit every individual with cancer risk, particularly because of their genetic variations in NSAID-related genes. Detecting such pharmacogenomic features among normal people or cancer patients makes it possible to select individuals who might benefit from NSAIDs in chemoprevention or anti-cancer treatment.

Besides pharmacogenomic features, other factors might have an impact on the effectiveness or toxicity of NSAIDs as well. The dose, duration and frequency of NSAID use is a critical issue. An average daily dose of 100 mg of coated aspirin have favorable preventive effects on cancer, and cancer-specific survival benefit is achieved with aspirin doses as low as 80 mg daily (Chia et al., 2012; Lotrionte et al., 2016). The effective dose and frequency of celecoxib in chemoprevention and treatment varied among different populations, and some recommended doses and frequencies are listed as follows: 400 mg daily for preventing recurrence of breast cancer and colorectal adenoma, 600 mg bid for NSCLC patients receiving erlotinib and 16 mg/kg/day for children with colorectal cancer risk (Reckamp et al., 2006; Lynch et al., 2010; Saxena et al., 2020). Researches focusing on relationship between duration and effectiveness of NSAID use remains limited. Consistent aspirin use over 6 years reduced colorectal cancer risk among men (Chan et al., 2008). Aspirin use over 10 years significantly reduced HCC incidence while the use for 5–10 years only achieved marginal reduction (Fujiwara et al., 2019). Pharmacokinetic interaction with other anti-cancer drugs also affected the effectiveness of NSAIDs. Ibuprofen co-administered with pemetrexed suppressed the clearance of pemetrexed and increased its maximum plasma concentration (Sweeney et al., 2006). Coadministration of celecoxib and capecitabine increased celecoxib exposure in patients, which suggested the importance of close monitoring of cancer patients receiving NSAIDs with a narrow therapeutic index (Ramírez et al., 2019). In addition, selective COX-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib have been associated with great risk of adverse cardiovascular effects, and aspirin use was associated with a higher risk of major bleeding in individuals without cardiovascular disease (Zheng and Roddick, 2019; Schjerning et al., 2020). Such NSAID-related adverse events must be considered before use.

Novel technologies such as liquid biopsy and next generation sequencing have enabled the quick and sensitive detection of pharmacogenomic features among cancer patients (Bignucolo et al., 2017). Early detection and real-time monitoring of NSAID-related pharmacogenomic features could help identify individuals with specific genomic characteristics related to NSAID sensitivity and allow precise selection of patients, thus achieving successful personalized chemoprevention and treatment for cancer.

Author contributions

HL, YL, and JW collected the original literature and drafted the manuscript. JC, HJ, YX, and SD revised and edited the draft. YX and SD supervised the work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

COX, cyclooxygenase; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; RXRα, retinoid X receptor α; NF-κB, Nuclear factor-kappa B; AP-1, activator protein 1; SP-1, Transcription factor Sp1; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; PDPK-1, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1; PDE5, phosphodiesterase 5; SERCA, sarcoendoplasmic/reticulum Ca2+ATPase; CSC, cancer stem-like cells.

References

- Ahmadi M., Emery D. C., Morgan D. J. (2008). Prevention of both direct and cross-priming of antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses following overproduction of prostaglandin E2 by tumor cells in vivo . Cancer Res. 68 (18), 7520–7529. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-08-1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano H., Ito Y., Suzuki T., Kato S., Matsui Y., Ogawa F., et al. (2009). Roles of a prostaglandin E-type receptor, EP3, in upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and vascular endothelial growth factor during enhancement of tumor metastasis. Cancer Sci. 100 (12), 2318–2324. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01322.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angstadt A. Y., Hartman T. J., Lesko S. M., Muscat J. E., Zhu J., Gallagher C. J., et al. (2014). The effect of UGT1A and UGT2B polymorphisms on colorectal cancer risk: Haplotype associations and gene–environment interactions. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 53 (6), 454–466. 10.1002/gcc.22157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T., Narumiya S. (2012). Prostaglandins and chronic inflammation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33 (6), 304–311. 10.1016/j.tips.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arico S., Pattingre S., Bauvy C., Gane P., Barbat A., Codogno P., et al. (2002). Celecoxib induces apoptosis by inhibiting 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 activity in the human colon cancer HT-29 cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 277 (31), 27613–27621. 10.1074/jbc.M201119200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbar N., Ignatenko N. A., Casero R. A., Jr., Gerner E. W. (2003). Cyclooxygenase-independent induction of apoptosis by sulindac sulfone is mediated by polyamines in colon cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 278 (48), 47762–47775. 10.1074/jbc.M307265200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler J., Whitton J., Lampe J. W., Fosdick L., Bostick R. M., Potter J. D. (2001). CYP2C9 and UGT1A6 genotypes modulate the protective effect of aspirin on colon adenoma risk. Cancer Res. 61 (9), 3566–3569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignucolo A., De Mattia E., Cecchin E., Roncato R., Toffoli G. (2017). Pharmacogenomics of targeted agents for personalization of colorectal cancer treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (7), 1522. 10.3390/ijms18071522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti C., Santucci C., Gallus S., Martinetti M., La Vecchia C. (2020). Aspirin and the risk of colorectal and other digestive tract cancers: An updated meta-analysis through 2019. Ann. Oncol. 31 (5), 558–568. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan F. G., Holla V., Katkuri S., Matta P., DuBois R. N. (2007). Targeting cyclooxygenase-2 and the epidermal growth factor receptor for the prevention and treatment of intestinal cancer. Cancer Res. 67 (19), 9380–9388. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-07-0710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Nishihara R., Qian Z. R., Song M., Mima K., Inamura K., et al. (2016). Regular aspirin use associates with lower risk of colorectal cancers with low numbers of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Gastroenterology 151 (5), 879–892. e874. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadei-Gardini A., Rovesti G., Dadduzio V., Vivaldi C., Lai E., Lonardi S., et al. (2021). Impact of Aspirin on clinical outcome in advanced HCC patients receiving sorafenib and regorafenib. HPB Oxf. 23 (6), 915–920. 10.1016/j.hpb.2020.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. T., Giovannucci E. L., Meyerhardt J. A., Schernhammer E. S., Wu K., Fuchs C. S. (2008). Aspirin dose and duration of use and risk of colorectal cancer in men. Gastroenterology 134 (1), 21–28. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. T., Tranah G. J., Giovannucci E. L., Hunter D. J., Fuchs C. S. (2005). Genetic variants in the UGT1A6 enzyme, aspirin use, and the risk of colorectal adenoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97 (6), 457–460. 10.1093/jnci/dji066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. T., Zauber A. G., Hsu M., Breazna A., Hunter D. J., Rosenstein R. B., et al. (2009). Cytochrome P450 2C9 variants influence response to celecoxib for prevention of colorectal adenoma. Gastroenterology 136 (7), 21272127–21272136. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E. T., Birmann B. M., Kasperzyk J. L., Conti D. V., Kraft P., Ambinder R. F., et al. (2009). Polymorphic variation in NFKB1 and other aspirin-related genes and risk of Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 18 (3), 976–986. 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-08-1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. H., Liu C. H., Conway R., Han D. K., Nithipatikom K., Trifan O. C., et al. (2004). Role of prostaglandin E2-dependent angiogenic switch in cyclooxygenase 2-induced breast cancer progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 (2), 591–596. 10.1073/pnas.2535911100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Qi Q., Wu N., Wang Y., Feng Q., Jin R., et al. (2022). Aspirin promotes RSL3-induced ferroptosis by suppressing mTOR/SREBP-1/SCD1-mediated lipogenesis in PIK3CA-mutatnt colorectal cancer. Redox Biol. 55, 102426. 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Li W., Qiu F., Huang Q., Jiang Z., Ye J., et al. (2018). Aspirin cooperates with p300 to activate the acetylation of H3K9 and promote FasL-mediated apoptosis of cancer stem-like cells in colorectal cancer. Theranostics 8 (16), 4447–4461. 10.7150/thno.24284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia W. K., Ali R., Toh H. C. (2012). Aspirin as adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer-reinterpreting paradigms. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 9 (10), 561–570. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe K. S., Cowan J. E., Chan J. M., Carroll P. R., D'Amico A. V., Liauw S. L. (2012). Aspirin use and the risk of prostate cancer mortality in men treated with prostatectomy or radiotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 30 (28), 3540–3544. 10.1200/jco.2011.41.0308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortellini A., Tucci M., Adamo V., Stucci L. S., Russo A., Tanda E. T., et al. (2020). Integrated analysis of concomitant medications and oncological outcomes from PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice. J. Immunother. Cancer 8 (2), e001361. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crokart N., Radermacher K., Jordan B. F., Baudelet C., Cron G. O., Grégoire V., et al. (2005). Tumor radiosensitization by antiinflammatory drugs: Evidence for a new mechanism involving the oxygen effect. Cancer Res. 65 (17), 7911–7916. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-05-1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crusz S. M., Balkwill F. R. (2015). Inflammation and cancer: Advances and new agents. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 12 (10), 584–596. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H. Y., Wang S. J., Song F., Cheng X., Nan G., Zhao Y., et al. (2021). CD147 receptor is essential for TFF3-mediated signaling regulating colorectal cancer progression. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6 (1), 268. 10.1038/s41392-021-00677-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku T., Wang D., Tranguch S., Morrow J. D., Orsulic S., DuBois R. N., et al. (2005). Cyclooxygenase-1 is a potential target for prevention and treatment of ovarian epithelial cancer. Cancer Res. 65 (9), 3735–3744. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-04-3814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Din F. V., Valanciute A., Houde V. P., Zibrova D., Green K. A., Sakamoto K., et al. (2012). Aspirin inhibits mTOR signaling, activates AMP-activated protein kinase, and induces autophagy in colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology 142 (7), 15041504–15041515. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E., Church D. N., Sieber O., Ramamoorthy R., Yanagisawa Y., Johnstone E., et al. (2013). Evaluation of PIK3CA mutation as a predictor of benefit from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 31 (34), 4297–4305. 10.1200/jco.2013.50.0322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z., Huang C., Brown R. E., Ma W. Y. (1997). Inhibition of activator protein 1 activity and neoplastic transformation by aspirin. J. Biol. Chem. 272 (15), 9962–9970. 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman M. J., Watson D., Wang X., Morrison C., Kratzke R. A., Jewell S., et al. (2008). Eicosanoid modulation in advanced lung cancer: cyclooxygenase-2 expression is a positive predictive factor for celecoxib + chemotherapy-cancer and leukemia group B trial 30203. J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (6), 848–855. 10.1200/jco.2007.13.8081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav E., Nowarski R., Thaiss C. A., Hu B., Jin C., Flavell R. A. (2013). Inflammation-induced cancer: Crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13 (11), 759–771. 10.1038/nrc3611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmets C. A., Viner J. L., Pentland A. P., Cantrell W., Lin H. Y., Bailey H., et al. (2010). Chemoprevention of nonmelanoma skin cancer with celecoxib: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 102 (24), 1835–1844. 10.1093/jnci/djq442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang M., Li Y., Huang K., Qi S., Zhang J., Zgodzinski W., et al. (2017). IL33 promotes colon cancer cell stemness via JNK activation and macrophage recruitment. Cancer Res. 77 (10), 2735–2745. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-16-1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R., Anderson G., Xiao G., Elliott G., Leoni L., Mapara M. Y., et al. (2007). SDX-308, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent, inhibits NF-kappaB activity, resulting in strong inhibition of osteoclast formation/activity and multiple myeloma cell growth. Blood 109 (5), 2130–2138. 10.1182/blood-2006-07-027458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser D. M., Sullivan F. M., Thompson A. M., McCowan C. (2014). Aspirin use and survival after the diagnosis of breast cancer: A population-based cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 111 (3), 623–627. 10.1038/bjc.2014.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frouws M. A., Bastiaannet E., Langley R. E., Chia W. K., van Herk-Sukel M. P., Lemmens V. E., et al. (2017). Effect of low-dose aspirin use on survival of patients with gastrointestinal malignancies; an observational study. Br. J. Cancer 116 (3), 405–413. 10.1038/bjc.2016.425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara N., Singal A. G., Hoshida Y. (2019). Dose and duration of aspirin use to reduce incident hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 70 (6), 2216–2217. 10.1002/hep.30813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton J. N., Gilroy D. W. (2016). Resolution of inflammation: A new therapeutic frontier. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15 (8), 551–567. 10.1038/nrd.2016.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk C. D. (2001). Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: Advances in eicosanoid biology. Science 294 (5548), 1871–1875. 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadgeel S. M., Ruckdeschel J. C., Heath E. I., Heilbrun L. K., Venkatramanamoorthy R., Wozniak A. (2007). Phase II study of gefitinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI), and celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor, in patients with platinum refractory non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J. Thorac. Oncol. 2 (4), 299–305. 10.1097/01.Jto.0000263712.61697.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallouet A. S., Travert M., Bresson-Bepoldin L., Guilloton F., Pangault C., Caulet-Maugendre S., et al. (2014). COX-2-independent effects of celecoxib sensitize lymphoma B cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 20 (10), 2663–2673. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-13-2305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholamian Dehkordi N., Mirzaei S. A., Elahian F. (2021). Pharmacodynamic mechanisms of anti-inflammatory drugs on the chemosensitization of multidrug-resistant cancers and the pharmacogenetics effectiveness. Inflammopharmacology 29 (1), 49–74. 10.1007/s10787-020-00765-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giampieri R., Restivo A., Pusceddu V., Del Prete M., Maccaroni E., Bittoni A., et al. (2017). The role of aspirin as antitumoral agent for heavily pretreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving capecitabine monotherapy. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 16 (1), 38–43. 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten F. R., Grivennikov S. I. (2019). Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 51 (1), 27–41. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridelli C., Gallo C., Ceribelli A., Gebbia V., Gamucci T., Ciardiello F., et al. (2007). Factorial phase III randomised trial of rofecoxib and prolonged constant infusion of gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: The GEmcitabine-COxib in NSCLC (GECO) study. Lancet. Oncol. 8 (6), 500–512. 10.1016/s1470-2045(07)70146-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov S. I., Greten F. R., Karin M. (2010). Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140 (6), 883–899. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T., Cao Y., Qian Z. R., Masugi Y., Nowak J. A., Yang J., et al. (2017). Aspirin use and colorectal cancer survival according to tumor CD274 (programmed cell death 1 ligand 1) expression status. J. Clin. Oncol. 35 (16), 1836–1844. 10.1200/jco.2016.70.7547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R., Hao S., Lu C., Zhang C., Lin C., Li L., et al. (2020). Aspirin sensitizes osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cells in vitro and in vivo via Bim-dependent apoptosis induction. Mol. Oncol. 14 (6), 1152–1169. 10.1002/1878-0261.12682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi Goradel N., Najafi M., Salehi E., Farhood B., Mortezaee K. (2019). Cyclooxygenase-2 in cancer: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 234 (5), 5683–5699. 10.1002/jcp.27411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley S. A., Fullerton M. D., Ross F. A., Schertzer J. D., Chevtzoff C., Walker K. J., et al. (2012). The ancient drug salicylate directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase. Science 336 (6083), 918–922. 10.1126/science.1215327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T. C., Chan T. A., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. (1999). PPARdelta is an APC-regulated target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cell 99 (3), 335–345. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81664-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C. E., Huang J. C., Pace T. R., Howard A. B., Muss H. B. (2008). Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors differentially affect vascular endothelial growth factor and endostatin levels in women with breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 14 (10), 3070–3076. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-07-4640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J., Karin M., Sun B. (2021). Targeting cancer-promoting inflammation - have anti-inflammatory therapies come of age? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18 (5), 261–279. 10.1038/s41571-020-00459-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz L. M., Townsend M. K., Jordan S. J., Patel A. V., Teras L. R., Lacey J. V., Jr., et al. (2022). Modification of the association between frequent aspirin use and ovarian cancer risk: A meta-analysis using individual-level data from two ovarian cancer consortia. J. Clin. Oncol., Jco2101900. 10.1200/jco.21.01900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs E. J., Newton C. C., Stevens V. L., Campbell P. T., Freedland S. J., Gapstur S. M. (2014). Daily aspirin use and prostate cancer-specific mortality in a large cohort of men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 32 (33), 3716–3722. 10.1200/jco.2013.54.8875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Qiu J., Li Q., Shi Z. (2017). Prostaglandin E2 signaling: Alternative target for glioblastoma? Trends Cancer 3 (2), 75–78. 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M. J., Chen Y. Y., Dai J. J., Gu D. N., Mei Z., Liu F. R., et al. (2020). Dying tumor cell-derived exosomal miR-194-5p potentiates survival and repopulation of tumor repopulating cells upon radiotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer 19 (1), 68. 10.1186/s12943-020-01178-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. J., Hsu A. L., Lin H. P., Song X., Chen C. S. (2002). The cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib perturbs intracellular calcium by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases: A plausible link with its anti-tumour effect and cardiovascular risks. Biochem. J. 366 (3), 831–837. 10.1042/bj20020279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T., Fujino H., Oyama S., Kawashima T., Murayama T. (2011). Indomethacin induces cellular morphological change and migration via epithelial-mesenchymal transition in A549 human lung cancer cells: A novel cyclooxygenase-inhibition-independent effect. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82 (11), 1781–1791. 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.07.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern M. A., Haugg A. M., Koch A. F., Schilling T., Breuhahn K., Walczak H., et al. (2006). Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition induces apoptosis signaling via death receptors and mitochondria in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 66 (14), 7059–7066. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-06-0325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf N., Yuan C., Hamada T., Cao Y., Babic A., Morales-Oyarvide V., et al. (2018). Regular use of aspirin or non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is not associated with risk of incident pancreatic cancer in two large cohort studies. Gastroenterology 154 (5), 1380–1390. e1385. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolluri S. K., Corr M., James S. Y., Bernasconi M., Lu D., Liu W., et al. (2005). The R-enantiomer of the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug etodolac binds retinoid X receptor and induces tumor-selective apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 (7), 2525–2530. 10.1073/pnas.0409721102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulp S. K., Yang Y. T., Hung C. C., Chen K. F., Lai J. P., Tseng P. H., et al. (2004). 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1/Akt signaling represents a major cyclooxygenase-2-independent target for celecoxib in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 64 (4), 1444–1451. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. J., Kim S. J., Hahn Y. I., Yoon H. J., Han B., Kim K., et al. (2019). 15-Keto prostaglandin E(2) suppresses STAT3 signaling and inhibits breast cancer cell growth and progression. Redox Biol. 23, 101175. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. J., Reinhardt F., Herschman H. R., Weinberg R. A. (2012). Cancer-stimulated mesenchymal stem cells create a carcinoma stem cell niche via prostaglandin E2 signaling. Cancer Discov. 2 (9), 840–855. 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-12-0101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhu F., Chen H., Cheng K. W., Zykova T., Oi N., et al. (2014). 6-C-(E-phenylethenyl)-naringenin suppresses colorectal cancer growth by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-1. Cancer Res. 74 (1), 243–252. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-13-2245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Wu H., Zhang H., Shi Y., Xu J., Ye Y., et al. (2015). Aspirin use after diagnosis but not prediagnosis improves established colorectal cancer survival: A meta-analysis. Gut 64 (9), 1419–1425. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D., Zhong L., Duan T., Zhang R. H., Wang X., Wang G., et al. (2015). Aspirin suppresses the growth and metastasis of osteosarcoma through the NF-κB pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 21 (23), 5349–5359. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-15-0198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S. F., Koshiol J., Huang Y. H., Jackson S. S., Huang Y. H., Chan C., et al. (2021). Postdiagnosis aspirin use associated with decreased biliary tract cancer-specific mortality in a large nationwide cohort. Hepatology 74 (4), 1994–2006. 10.1002/hep.31879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J. Y., Ghelani D., Yeh S., Wu K. K. (2007). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs induce colorectal cancer cell apoptosis by suppressing 14-3-3epsilon. Cancer Res. 67 (7), 3185–3191. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-06-3431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Ma W. Y., Bode A. M., Zhang Y., Dong Z. (2003). NS-398 and piroxicam suppress UVB-induced activator protein 1 activity by mechanisms independent of cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 278 (4), 2124–2130. 10.1074/jbc.M202443200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Ge D., Ma L., Mei J., Liu S., Zhang Q., et al. (2012). Interleukin-17 and prostaglandin E2 are involved in formation of an M2 macrophage-dominant microenvironment in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 7 (7), 1091–1100. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182542752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Hong L., Nilsson M., Hubert S. M., Wu S., Rinsurongkawong W., et al. (2020). Concurrent use of aspirin with osimertinib is associated with improved survival in advanced EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 149, 33–40. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomans-Kropp H. A., Pinsky P., Umar A. (2021). Evaluation of aspirin use with cancer incidence and survival among older adults in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw. Open 4 (1), e2032072. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotrionte M., Biasucci L. M., Peruzzi M., Frati G., Giordano A., Biondi-Zoccai G. (2016). Which aspirin dose and preparation is best for the long-term prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer? Evidence from a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 58 (5), 495–504. 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Zhang Q., Wu K., Chen X., Zheng Y., Zhu C., et al. (2015). Hepatitis C virus NS3 protein enhances cancer cell invasion by activating matrix metalloproteinase-9 and cyclooxygenase-2 through ERK/p38/NF-κB signal cascade. Cancer Lett. 356 (2), 470–478. 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucotti S., Cerutti C., Soyer M., Gil-Bernabé A. M., Gomes A. L., Allen P. D., et al. (2019). Aspirin blocks formation of metastatic intravascular niches by inhibiting platelet-derived COX-1/thromboxane A2. J. Clin. Invest. 129 (5), 1845–1862. 10.1172/jci121985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch P. M., Ayers G. D., Hawk E., Richmond E., Eagle C., Woloj M., et al. (2010). The safety and efficacy of celecoxib in children with familial adenomatous polyposis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105 (6), 1437–1443. 10.1038/ajg.2009.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Gonzalez-Junca A., Zheng Y., Ouyang H., Illa-Bochaca I., Horst K. C., et al. (2021a). Inflammation mediates the development of aggressive breast cancer following radiotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 27 (6), 1778–1791. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-20-3215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Guo C., Sun C., Han T., Zhang H., Qu G., et al. (2021b). Aspirin use and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies from 1989 to 2019. Clin. Breast Cancer 21 (6), 552–565. 10.1016/j.clbc.2021.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marthey L., Mateus C., Mussini C., Nachury M., Nancey S., Grange F., et al. (2016). Cancer immunotherapy with anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies induces an inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis 10 (4), 395–401. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mc Menamin Ú C., Cardwell C. R., Hughes C. M., Murray L. M. (2015). Low-dose aspirin and survival from lung cancer: A population-based cohort study. BMC Cancer 15, 911. 10.1186/s12885-015-1910-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil J. J., Gibbs P., Orchard S. G., Lockery J. E., Bernstein W. B., Cao Y., et al. (2021). Effect of aspirin on cancer incidence and mortality in older adults. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 113 (3), 258–265. 10.1093/jnci/djaa114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil J. J., Nelson M. R., Woods R. L., Lockery J. E., Wolfe R., Reid C. M., et al. (2018). Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 379 (16), 1519–1528. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhardt J. A., Shi Q., Fuchs C. S., Meyer J., Niedzwiecki D., Zemla T., et al. (2021). Effect of celecoxib vs placebo added to standard adjuvant therapy on disease-free survival among patients with stage III colon cancer: The CALGB/SWOG 80702 (alliance) randomized clinical trial. Jama 325 (13), 1277–1286. 10.1001/jama.2021.2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon C. M., Kwon J. H., Kim J. S., Oh S. H., Jin Lee K., Park J. J., et al. (2014). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs suppress cancer stem cells via inhibiting PTGS2 (cyclooxygenase 2) and NOTCH/HES1 and activating PPARG in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 134 (3), 519–529. 10.1002/ijc.28381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan H., Hutter C. M., Lin Y., Jacobs E. J., Ulrich C. M., White E., et al. (2015). Association of aspirin and NSAID use with risk of colorectal cancer according to genetic variants. Jama 313 (11), 1133–1142. 10.1001/jama.2015.1815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. W., Myung S. K., Park J. Y., Lee C. M., Kwon H. T. (2011). Aspirin use and risk for lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 22 (11), 2456–2465. 10.1093/annonc/mdq779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennarun B., Kleibeuker J. H., Boersma-van Ek W., Kruyt F. A., Hollema H., de Vries E. G., et al. (2013). Targeting FLIP and Mcl-1 using a combination of aspirin and sorafenib sensitizes colon cancer cells to TRAIL. J. Pathol. 229 (3), 410–421. 10.1002/path.4138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi C., Jing P., Li B., Feng Y., Xu L., Xie K., et al. (2022). Reversing PD-1 resistance in B16F10 cells and recovering tumour immunity using a COX2 inhibitor. Cancers (Basel) 14 (17), 4134. 10.3390/cancers14174134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradono P., Tazawa R., Maemondo M., Tanaka M., Usui K., Saijo Y., et al. (2002). Gene transfer of thromboxane A(2) synthase and prostaglandin I(2) synthase antithetically altered tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 62 (1), 63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader J. S., Sill M. W., Beumer J. H., Lankes H. A., Benbrook D. M., Garcia F., et al. (2017). A stratified randomized double-blind phase II trial of celecoxib for treating patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: The potential predictive value of VEGF serum levels: An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol. Oncol. 145 (2), 291–297. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.02.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez J., House L. K., Karrison T. G., Janisch L. A., Turcich M., Salgia R., et al. (2019). Prolonged pharmacokinetic interaction between capecitabine and a CYP2C9 substrate, celecoxib. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 59 (12), 1632–1640. 10.1002/jcph.1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckamp K. L., Krysan K., Morrow J. D., Milne G. L., Newman R. A., Tucker C., et al. (2006). A phase I trial to determine the optimal biological dose of celecoxib when combined with erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12 (11), 3381–3388. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-06-0112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden D. M., McLeod H. L., Relling M. V., Williams M. S., Mensah G. A., Peterson J. F., et al. (2019). Pharmacogenomics. Lancet 394 (10197), 521–532. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31276-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S., Mukherjee S., Khan P., Kajal K., Mazumdar M., Manna A., et al. (2016). Aspirin suppresses the acquisition of chemoresistance in breast cancer by disrupting an nf?b-IL6 signaling Axis responsible for the generation of cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 76 (7), 2000–2012. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-15-1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvado M. D., Di Gennaro A., Lindbom L., Agerberth B., Haeggström J. Z. (2013). Cathelicidin LL-37 induces angiogenesis via PGE2-EP3 signaling in endothelial cells, in vivo inhibition by aspirin. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33 (8), 1965–1972. 10.1161/atvbaha.113.301851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samowitz W. S., Wolff R. K., Curtin K., Sweeney C., Ma K. N., Andersen K., et al. (2006). Interactions between CYP2C9 and UGT1A6 polymorphisms and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in colorectal cancer prevention. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4 (7), 894–901. 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena P., Sharma P. K., Purohit P. (2020). A journey of celecoxib from pain to cancer. Prostagl. Other Lipid Mediat. 147, 106379. 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2019.106379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer D., Koepl L. M., Poole E. M., Balavarca Y., Xiao L., Baron J. A., et al. (2014). Genetic variation in UGT genes modify the associations of NSAIDs with risk of colorectal cancer: Colon cancer family registry. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 53 (7), 568–578. 10.1002/gcc.22167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schjerning A. M., McGettigan P., Gislason G. (2020). Cardiovascular effects and safety of (non-aspirin) NSAIDs. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17 (9), 574–584. 10.1038/s41569-020-0366-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seufert B. L., Poole E. M., Whitton J., Xiao L., Makar K. W., Campbell P. T., et al. (2013). IκBKβ and NFκB1, NSAID use and risk of colorectal cancer in the Colon Cancer Family Registry. Carcinogenesis 34 (1), 79–85. 10.1093/carcin/bgs296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishodia S., Aggarwal B. B. (2004). Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor celecoxib abrogates activation of cigarette smoke-induced nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB by suppressing activation of IkappaBalpha kinase in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: Correlation with suppression of cyclin D1, COX-2, and matrix metalloproteinase-9. Cancer Res. 64 (14), 5004–5012. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-04-0206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon T. G., Duberg A. S., Aleman S., Chung R. T., Chan A. T., Ludvigsson J. F. (2020). Association of aspirin with hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (11), 1018–1028. 10.1056/NEJMoa1912035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery M. L., Lundgreen A., Wolff R. K. (2014). VEGFA, FLT1, KDR and colorectal cancer: Assessment of disease risk, tumor molecular phenotype, and survival. Mol. Carcinog. 53 (1), E140–E150. 10.1002/mc.22058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser-Weippl K., Higgins M. J., Chapman J. W., Ingle J. N., Sledge G. W., Budd G. T., et al. (2018). Effects of celecoxib and low-dose aspirin on outcomes in adjuvant aromatase inhibitor-treated patients: Cctg MA.27. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110 (9), 1003–1008. 10.1093/jnci/djy017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D., Liu H., Dai X., Zheng X., Yan J., Wei R., et al. (2017). Aspirin disrupts the mTOR-Raptor complex and potentiates the anti-cancer activities of sorafenib via mTORC1 inhibition. Cancer Lett. 406, 105–115. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K., Yu J., Hu J., Chen J., Song J., Chen Z., et al. (2022). Salicylic acid-based hypoxia-responsive chemodynamic nanomedicines boost antitumor immunotherapy by modulating immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Acta Biomater. 148, 230–243. 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Dai H., Chen S., Zhang Y., Wu T., Cao X., et al. (2018). Disruption of chromosomal architecture of cox2 locus sensitizes lung cancer cells to radiotherapy. Mol. Ther. 26 (10), 2456–2465. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]