Abstract

Objective

Mood and physical symptoms related to the menstrual cycle affect women's productivity at work, often leading to absenteeism. However, employer-led initiatives to tackle these issues are lacking. Digital health interventions focused on women's health (such as the Flo app) could help fill this gap.

Methods

1867 users of the Flo app participated in a survey exploring the impact of their menstrual cycle on their workplace productivity and the role of Flo in mitigating some of the identified issues.

Results

The majority reported a moderate to severe impact of their cycle on workplace productivity, with 45.2% reporting absenteeism (5.8 days on average in the previous 12 months). 48.4% reported not receiving any support from their manager and 94.6% said they were not provided with any specific benefit for issues related to their menstrual cycle, with 75.6% declaring wanting them. Users stated that the Flo app helped them with the management of menstrual cycle symptoms (68.7%), preparedness and bodily awareness (88.7%), openness with others (52.5%), and feeling supported (77.6%). Users who reported the most positive impact of the Flo app were 18–25% less likely to report an impact of their menstrual cycle on their productivity and 12–18% less likely to take days off work for issues related to their cycle.

Conclusions

Apps such as Flo could equip individuals with tools to better cope with issues related to their menstrual cycle and facilitate discussions around menstrual health in the workplace.

Keywords: Menstrual cycle, women's health, productivity, absenteeism, digital health, workplace wellbeing, premenstrual syndrome

Introduction

Women lose more days of work for health reasons compared to men.1 One of the reasons put forward to explain this difference is menstrual cycle-related symptoms.2,3 Although this is a relatively under-researched area, evidence suggests that symptoms women experience during parts of their menstrual cycle may impact their performance at work.4,5 In a recent survey of approximately 33,000 respondents,5 13.8% of women reported absenteeism (i.e. failure to report for or remain at work or in school as planned) during their menses and 80.7% reported presenteeism (i.e. the act of showing up for work or school without being productive). They also reported an average of 23.3 days a year of productivity loss. Strikingly, only 20% of women felt comfortable disclosing the reason for their absence to their employers or teachers. One of the most debilitating symptoms related to the menstrual cycle is dysmenorrhea (i.e. cramp-like pain occurring before and/or during menstruation), often accompanied by heavy menstrual bleeding. Dysmenorrhea, affecting 45–95% of women,6 has been reported as heavily impacting productivity and focus, often leading to absences from work.4,7–10 Similarly, heavy menstrual bleeding has been associated with productivity loss.11,12

Another commonly reported issue affecting 20–40% of women is premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and its more severe form, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMS and PMDD are defined by a series of psychological and physical symptoms occurring in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and causing dysfunction in social or economic performance (PMS) and/or significant affective and functional impairment (PMDD).13 Higher levels of PMS and PMDD symptoms have been associated with impaired productivity and absenteeism.14–16 Furthermore, conditions of the uterus, such as endometriosis (i.e. an often painful condition where the endometrium starts to grow outside of the uterus) can have a significant impact on women's performance at work. Women with endometriosis report absenteeism and reduced productivity,17–20 amounting to an average of 10.8 h of lost work per week with a cost up to $456 per woman per week.21

On top of direct costs to employers, issues related to the menstrual cycle can negatively affect women's quality of life, career progression,22 including disadvantaging them during the hiring process,23 and increase healthcare costs. Women affected by dysmenorrhea report compromised quality of life, with repercussions encompassing interpersonal relationships.24–27 Heavy menstrual bleeding has been associated with both reduced quality of life and increased healthcare utilization.11,12,28–30 The health-related quality of life burden of PMS and PMDD has been deemed greater than type 2 diabetes and hypertension (in terms of reported pain), and comparable to chronic rheumatological conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.14,31,32 Lastly, endometriosis is associated with increased healthcare costs (with an average annual cost of €9579 per woman20) and decreased quality of life, including impairments in psychological and social functioning.33–36 Despite the clear cost to individuals, healthcare systems and employers alike, workplace solutions effectively tackling the negative impact of issues related to the menstrual cycle are lacking.

Digital health interventions (DHI), such as internet-based resources and mobile apps, have become increasingly popular in the workplace due to their scalability, availability, and anonymity.37,38 The latter aspect, anonymity, is particularly relevant for interventions addressing issues that are still surrounded by high levels of stigma (such as mental or menstrual health39–44). One such DHI focusing on women's health is the Flo mobile phone app (by Flo Health Inc.). Flo allows users to track their physical and mood symptoms throughout their menstrual cycle and offers AI-based period and ovulation predictions. Given the impact of the menstrual cycle on several aspects of women's life (from mood and behavior to physiology45), being able to track symptoms throughout the cycle facilitates women's preparedness, helps them identify patterns of irregular bleeding and supports conversations with healthcare providers.46 In the Flo app, personalized, evidence-based and expert-reviewed content is provided to users throughout their cycle both via the in-app library as well as through health assistants (chatbots). Health assistants also allow users to check for symptoms against an array of conditions. It is well-established that inadequate health literacy negatively impacts both individuals and healthcare systems.47 Specifically, inadequate health literacy has been linked to poorer wellbeing48 and self-care49 as well as higher healthcare costs50 due to underutilization of preventive services51 and delayed help-seeking behaviors when symptoms arise.52 Furthermore, Flo users have the opportunity to ask questions and provide answers to other users worldwide in an anonymous fashion, thus reducing the perceived stigma surrounding topics such as sexual life and menstrual health.40,42,43 Finally, the Flo app connects to a variety of wearable devices which collect sleep, heart rate and physical activity data. Lower heart rate and higher heart-rate variability (HRV) have been associated with better health and mental health,53,54 whereas the inverse pattern is associated with ill-health conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome and uterine fibroids.55–57

The aim of the current study was to measure the impact of disturbances related to the menstrual cycle on work-related productivity in users of the Flo app. Furthermore, we wanted to characterize the current levels of support women receive from their employers to tackle issues related to their menstrual cycle, both in terms of perceived support from managers as well as in terms of provision of benefits specific to women's health. Finally, we aimed to understand whether using the Flo app could help mitigate the impact of issues related to the menstrual cycle, which could in turn reduce their impact on productivity, as well as provide support.

Methods

Participants

Users of the Flo app who were employed full- or part-time, working in the United States and over 18 years of age were eligible to participate in this study. Recruitment took place within the Flo Health app between the 24th of January 2022 and the 13th of March 2022.

Informed electronic consent was obtained in accordance with approval from the Independent Ethical Review Board (WCG IRB) which deemed the study exempt. All data used in this study were de-identified and results aggregated to protect users’ privacy.

Materials

A survey was created using SurveyMonkey (see Supplemental Materials). Only users with the Premium (paid) subscription were included in the study, given that the majority of Flo content and chatbots are only available to Premium users. Information regarding each respondent's working environment was collected, including role and employer size. To measure the effects of the menstrual cycle on different dimensions of productivity, we asked our users to indicate on a scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”) how much their menstrual cycle negatively impacts their concentration, efficiency, energy levels, relationship with coworkers, level of interest in their own work and mood at work. Whilst the majority of available productivity questionnaires use the number of hours or days of productivity loss to compute a productivity measure, we employed a more user-friendly approach (multiple choice) investigating the severity of the impact of the menstrual cycle on well-known dimensions of work life. Furthermore, given that the survey was distributed via a notification within the Flo app, we decided to minimize survey completion time, thus limiting the number of questions to 6. To measure absenteeism, respondents were asked whether they missed work in the past 12 months due to issues related to the menstrual cycle, and, if so, the number of days of absence.

To assess the current level of support employees receive from their employers to address issues related to their menstrual cycle, we asked how freely respondents felt they could talk to their manager about such issues (on a scale from 1, “Not at all,” to 5, “Extremely”) and how much support they received from their manager (on a scale from 1, “No support,” to 5, “A great deal”). We also asked whether their employer offered benefits or wellness programs that helped and whether they would like such offerings.

Finally, to explore whether using the Flo app could help mitigate issues related to the menstrual cycle in order to reduce the impact on productivity and improve perceived support, we asked respondents how much they agreed with the following five statements: (1) “Flo helped me be prepared and aware of my body's signals”; (2) “Flo helped me feel supported”; (3) “Flo helped me improve how I manage my period symptoms”; (4) “Flo helped me be more open with others about my symptoms and how they make me feel,” and (5) “Flo improved my mood.” The final question of the survey asked respondents to indicate which aspects and functionalities of the Flo app helped them the most (options included: period predictions, symptom tracking, fertile days and ovulation predictions, symptom and cycle-related chats with Flo's health assistant, cycle widget, reading and watching in-app content, discussions in secret chats, courses with experts, report for their doctor and pills reminder).

Survey responses were linked to in-app data, including age, type of symptoms logged throughout the menstrual cycle and, for a subset of the sample, wearable data (activity, sleep and heart rate). Users can track a variety of dimensions, including physical symptoms (e.g. cramps, bloating), mood (e.g. happy, anxious), sex and drive (e.g. whether unprotected sex occurred), and vaginal discharge (e.g. creamy, watery).

Data were analyzed using the dplyr, tidyr, readr, stringr, purrr, Boot, and FastDummies packages for R. Figures were produced using Matplotlib and Seaborn packages for Python.

Procedures

Participants were notified of the opportunity to take part in a survey exploring how their menstrual cycle impacts their productivity at work via an in-app notification. Upon clicking on the notification, participants were redirected to SurveyMonkey and asked to provide electronic informed consent. Participants were then asked whether they were currently employed, and participants who were not were disqualified. Eligible participants proceeded to complete the survey on their electronic device which took an average of 3 min.

Statistical analyses

To obtain groupings of high and low levels of impact of the menstrual cycle on productivity, we summed the responses to the six productivity questions reported above and then split the users using the median value. Similarly, to investigate differences between those who reported having taken days off work due to their menstrual cycle and those who did not, we grouped users according to their answer to the question “Have you missed work in the past 12 months due to issues related to the menstrual cycle?.” To explore differences between groupings, t-tests with Welch's correction for degrees of freedom were employed for parametric data and Pearson's χ2 for frequency data.

To assess the relationship between the perceived impact of Flo and the reported impact the menstrual cycle has on users’ productivity and absenteeism, we employed individual logistic regression models for each statement related to the use of Flo (see “Materials” above). For productivity, the dependent variable in each model was whether user productivity was impacted (a binary variable with 0 = “low impact” and 1 = “high impact”), whereas for absenteeism it was whether the user reported having taken days off work (0 = “no absences” and 1 = “absences”). In both cases, the independent variable was the reported effect of Flo on the five statements reported above (with 0 = “Disagree”/“Somewhat disagree”/“Neither agree nor disagree” and 1 = “Somewhat agree”/“Agree”).

Results

We collected a total of 2670 partial responses and 1867 complete survey responses. When retrieving user data from respondents’ Flo accounts, we were able to link 1801 out of 1867 users (age: M = 28.7, SD = 6.7, range = 18–53), potentially due to account deletion after survey completion. Therefore, survey results are reported for the whole sample providing complete responses, whereas data extracted from the app is reported for 1801 users (including age, which is extracted from app data). Table 1 presents the samples’ demographic and work-related information. Please note that not all participants included their age as part of their in-app profile.

Table 1.

Work-related information of the sample (N = 1867).

| Work characteristic | Respondents, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Work environment | ||

| On-site (e.g. office) | 1285 (69) | |

| Remote | 310 (17) | |

| Hybrid | 272 (15) | |

| Company size | ||

| 0–50 | 793 (42) | |

| 51–250 | 390 (21) | |

| 251–500 | 150 (8) | |

| 501–1000 | 102 (5) | |

| 1001–1500 | 58 (3) | |

| 1501–3000 | 59 (3) | |

| 3001–5000 | 57 (3) | |

| 5000 + | 258 (14) | |

| Work role | ||

| Clerical | 129 (7) | |

| Entry-level | 183 (10) | |

| Executive management | 49 (3) | |

| Laborer | 115 (6) | |

| Manufacturing position | 37 (2) | |

| Medical professional | 229 (12) | |

| Middle management | 191 (10) | |

| Professional | 366 (20) | |

| Service worker | 306 (16) | |

| Skilled trades | 49 (3) | |

| Supervisor | 137 (7) | |

| Technical | 76 (4) | |

Impact of disturbances related to the menstrual cycle on work-related productivity

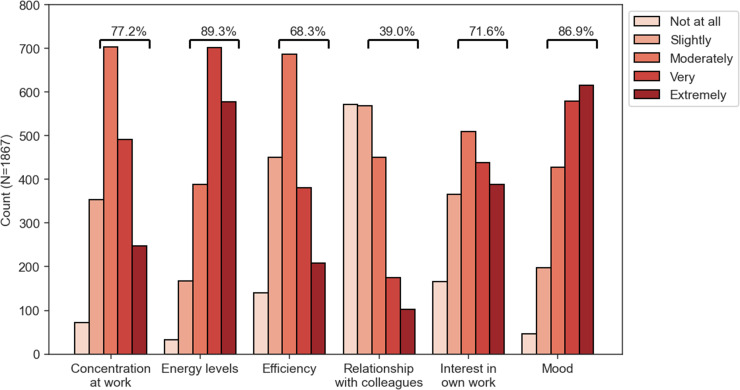

As can be seen in Figure 1, the majority of the respondents reported a moderate to severe negative impact on their concentration (77.2%), energy levels (89.3%), efficiency (68.3%), interest in their own work (71.6%), and mood (86.9%). The least impacted dimension was relationship with colleagues, with 39.0% of users reporting a moderate to severe impact due to their menstrual cycle.

Figure 1.

Frequency of survey questions exploring the impact of the menstrual cycle on different dimensions of productivity. Percentages represent grouped responses from “Moderately” to “Extremely,” defining higher impact.

45.2% (843/1867) of the respondents reported having missed days of work due to their menstrual cycle in the previous 12 months. On average, 5.8 days of work were missed (range = 0.5–42 days, SD = 5.8 days, N = 833). 10/843 users were deemed outliers (values > 2.5 SD) and were therefore excluded from the calculation. 15/843 respondents reported 0 days of missed work but their entries were modified to “0.5” since the survey would only accept integer values and we assumed that users attempted to include a decimal value as their answer.

To explore patterns of logged moods and symptoms throughout users’ menstrual cycles, we linked app data to survey data. We only included users who had logged moods and symptoms during at least two or more cycles within the last 12 months (N = 1638) and we included all symptoms logged at least once throughout the selected window. We compared the logs of those who had reported missing work in the previous 12 months to the rest of the sample and those who had reported a high impact on their productivity at work to those who reported low impact. Table 2 shows the top 15 most frequent logged symptoms of those who were absent and those who reported a high impact on productivity. The three most commonly reported symptoms by users at the sample level were cramps (91%), fatigue (85%), and bloating (81%). The findings are consistent for both users who reported absenteeism (N = 761) and users reporting a high impact on their productivity (N = 714).

Table 2.

Frequency of the 15 commonly reported symptoms in absent and high productivity impact users.

| Symptom/Mood/Disturber | User

(N = 1638) N, % |

Absent users

(N = 761) N, % |

High productivity impact users

(N = 714) N, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cramps | 1487 (91) | 706 (93) | 662 (93) |

| Fatigue | 1386 (85) | 659 (87) | 617 (86) |

| Bloating | 1327 (81) | 631 (83) | 606 (85) |

| Backache | 1301 (79) | 641 (84) | 590 (83) |

| Headache | 1296 (79) | 618 (81) | 583 (82) |

| Tender breasts | 1205 (74) | 582 (76) | 537 (75) |

| Irritated | 1203 (73) | 576 (76) | 547 (77) |

| Mood swings | 1202 (73) | 573 (75) | 554 (78) |

| Cravings | 1157 (71) | 543 (71) | 527 (74) |

| Calm | 1123 (69) | 509 (67) | 485 (68) |

| Acne | 1117 (68) | 523 (69) | 515 (72) |

| Nausea | 1058 (65) | 539 (71) | 484 (68) |

| Anxious | 1040 (63) | 509 (67) | 485 (68) |

| Diarrhea | 1010 (62) | 510 (67) | 450 (63) |

| Sad | 973 (59) | 496 (65) | 461 (65) |

We also explored whether there were any differences in wearable data profiles (namely sleep, activity and heart rate) based on the productivity and absenteeism groupings both throughout the cycle as well as in premenstrual and menstrual phases only (where we expect a more marked physiological response).

Sleep data were obtained for the 12 months prior to the survey completion from 596 survey respondents. The median duration over the week per cycle (only including nights prior to a working day, i.e. Sunday to Thursday) was computed. No difference was found in absenteeism or productivity groups for either the full cycle or selected phases (see Supplemental Materials).

Step count data was available for 1301 users. Collected step count entries provided the total number of steps taken for each user on individual dates. No significant difference in the median number of steps per day was found in either absenteeism or productivity groups (see Supplemental Materials).

HRV data obtained from wearable devices were only available for 50 respondents. Nevertheless, other heart-rate (HR) data were available for 295 respondents; 48 respondents had resting heart rate (RHR) available from a third-party provider (FitBit API); 253 respondents had series HR data, and 6 users had a combination of both. We were able to estimate RHR for users with series HR data; specifically, we grouped series HR data by user and date and used the 5th percentile as an estimate of RHR, given the lower percentile of daily heart-rate distribution would be closer to RHR.58 After outlier exclusion, we conducted the same analysis on the combined sample (N = 295 for full-cycle data, N = 245 for premenstrual and menstrual phases) as well as on the estimated RHR sample only (N = 253 for full-cycle data, N = 203 for selected phases) to ensure lack of bias due to different estimation methods (see Supplemental Materials). We found a significant difference in RHR in the premenstrual and menstrual phases between users reporting having taken days off from work due to their menstrual cycle (M = 68.5, SD = 7.5) and those who did not (M = 66.2, SD = 7.8), with the former group exhibiting higher RHR (t(241.17) = 2.295, p = 0.02, d = 0.293, N = 245). No difference was found across the menstrual cycle between individuals who took days off work due to their cycle and those who did not (see Supplemental Materials for the full analysis). Similarly, no difference (in either full cycle or premenstrual and menstrual phases) was observed for individuals reporting a higher impact of their menstrual cycle on productivity (versus low impact).

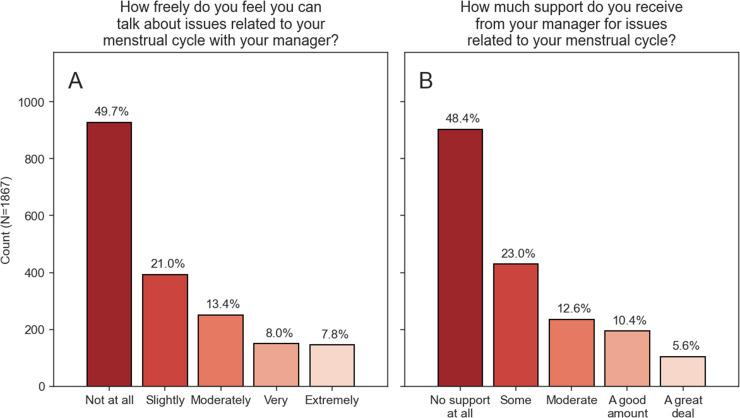

Perceived level of support and employers’ benefits

49.7% of respondents reported that they did not feel they could talk freely about issues related to their menstrual cycles with their manager (Figure 2(A)). Similarly, 48.4% reported they do not receive any support from their manager when it comes to their menstrual cycles (Figure 2(B)).

Figure 2.

(A) Frequency of survey responses from “not at all” to “extremely” when asked “how freely do you feel you can talk about issues related to your menstrual cycle with your manager?” (B) Frequency of survey responses from “no support at all” to “A great deal” when asked “how much support do you receive from your manager for issues related to your menstrual cycle?.”

In terms of offered benefits, the vast majority of the sample (94.6%) reported not having any specific benefit or wellness program that helped them with their menstrual cycle. Importantly, 75.6% of non-benefit-receiving respondents reported wanting them. The benefits listed by the 5.4% who reported having them included wellness programs, counseling, gym membership, health insurance, and paid leave.

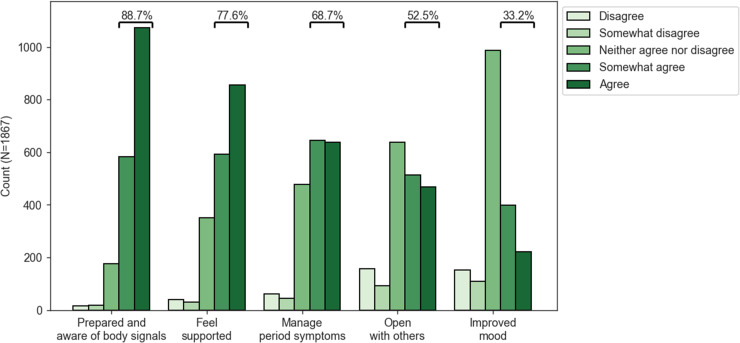

Role of Flo in mitigating the negative impact of cycle on productivity

The majority of respondents (complete responses, N = 1867) agreed or somewhat agreed that using Flo helped them be prepared and aware of their body's signals (88.7%), feel supported (77.6%), improve how they manage their period symptoms (68.7%), and be more open with others about their symptoms and how they make them feel (52.5%). 33.2% reported that Flo improved their mood (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frequency of survey questions exploring the role of Flo in mitigating different dimensions of menstrual cycle impact (preparedness and awareness of body signals, feelings of support, management of period symptoms, openness with others, improvement in mood). Users responded on a scale from “Disagree” to “Agree.” Percentages represent grouped responses from “Somewhat agree” to “Agree,” defining those who agreed with the statements.

Users reported that the app features they found most useful were period predictions (85.5%), symptoms tracking (73.8%), fertile days predictions (67.4%), and symptom and cycle-related chats with Flo's health assistant (53.1%). Those who reported having taken days off work were more likely to find symptom tracking most useful (χ(1) = 10.32, p = 0.01). Similarly, cycle-related chats were deemed most useful for users reporting a high impact on their productivity (χ(1) = 5.077, p = 0.024). No other difference was found (see Supplemental Materials for the full analysis).

We next explored the relationship between the perceived impact of Flo and the reported impact the menstrual cycle had on users’ productivity and absenteeism using individual logistic regression models for each statement. For all five dimensions, we found that users who agreed that Flo helped were 18–25% (OR: 0.82–0.75, Table 3) less likely to report that their menstrual cycle impacted their productivity. Similarly, users who agreed that Flo helped them manage their menstrual symptoms, be more prepared and aware of their bodily signals, improve their mood and feel supported were 12–16% less likely to take days off work for issues related to the menstrual cycle. Openness with others was not associated with lower absenteeism.

Table 3.

Likelihood and odds ratio of positive effect on productivity impact and absenteeism reported by Flo users. Odds ratios have been confirmed by bootstrapping 1×104 samples.

| Agree/Somewhat agree (N = 1867) | Likelihood to report low impact on productivity (%) | Productivity impacted odds ratio (bootstrap CI) | p | Likelihood to report absenteeism (%) | Absenteeism odds ratio (bootstrap CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manage symptoms | 1282 | 22 | 0.78 (0.70, 0.87) | <0.001 | 12 | 0.88 (0.79, 0.98) | <0.05 |

| Improve mood | 620 | 25 | 0.75 (0.64, 0.88) | <0.001 | 15 | 0.85 (0.72, 0.99) | <0.05 |

| Open with others | 981 | 18 | 0.82 (0.72, 0.93) | 0.002 | 8 | 0.92 (0.81, 1.04) | 0.19 |

| Prepared and aware | 1656 | 25 | 0.75 (0.68, 0.83) | <0.001 | 16 | 0.84 (0.76, 0.92) | <0.001 |

| Feel supported | 1448 | 24 | 0.76 (0.68, 0.84) | <0.001 | 14 | 0.86 (0.78, 0.96) | <0.001 |

Discussion

Principal findings

The aim of the current study was to assess the impact of the menstrual cycle on workplace productivity and absenteeism in Flo users, investigate current levels of support available to them in the workplace and explore whether the Flo app could help mitigate some of the identified issues. The majority of our sample reported disruption of productivity on several dimensions and a significant number reported having taken days off of work to deal with issues related to the menstrual cycle. Our respondents did not feel supported in the workplace, with the majority reporting difficulties in freely communicating with their managers and a lack of benefits directly tackling menstrual cycle issues. Nevertheless, using the Flo app positively impacted the management of menstrual cycle symptoms, preparedness and bodily awareness, openness with others (regarding issues related to the menstrual cycle), and levels of perceived support. Users who reported the most positive impact of the Flo app were less likely to report an impact of their menstrual cycle on their productivity and less likely to take days off work for issues related to their cycle.

Comparison with prior work

In line with the literature, our findings indicate that the menstrual cycle severely impacts productivity. In 45.2% of our sample, issues related to the menstrual cycle led to absenteeism. In Schoep and colleagues,5 80.7% of respondents indicated productivity loss and 13.8% reported having missed days of work or study due to menstruation-related issues. Discrepancies between our findings and the ones reported by Schoep and colleagues may be due to the different tools implemented in the two surveys. We measured the impact on productivity by asking how severely their menstrual cycle impacts different dimensions of their work whilst Schoep and colleagues focused on productivity loss (i.e. the amount of hours individuals were not productive). Similarly, absenteeism was calculated as the number of missed days per cycle in their survey, whilst we asked our users to report the total number of missed days over the course of the previous 12 months. Furthermore, they asked respondents to focus on their period when answering the questions, whereas we enquired about the entirety of the menstrual cycle. Further research utilizing both sets of questions within the same sample would be needed to draw a direct comparison.

The finding that cramps are the most commonly reported symptom is to be expected, given the high prevalence and severe impact of dysmenorrhea.6,59 Reports of tiredness60 and lack of energy61 around menstruation are also in line with the second most common symptom in our sample, fatigue. The same holds true for the third symptom, bloating.59–61 In line with our expectations, symptoms were largely logged during the premenstrual and menstruation phases of the cycle.

In terms of physiological data, the lack of difference in sleep patterns for those who reported absenteeism and high impact on productivity is surprising, especially given the link between sleep disturbances and workplace productivity.62,63 Nevertheless, a more systematic investigation with sleep data linked to self-reported productivity in different phases of the menstrual cycle may reveal more granular differences. On the other hand, our finding that those reporting absenteeism also exhibit a higher resting heart rate is in line with the literature and may indicate that individuals who take days off work might experience higher levels of stress64,65 or may be in a lower state of cardiovascular fitness.66 Further research, specifically aiming at investigating the relationship between resting heart rate and workplace absenteeism and productivity is needed to shed light on this result.

Our respondents also reported not feeling like they could talk freely about issues related to their menstrual cycle with their manager nor that they could receive support from management. These findings mirror the result of Schoep and colleagues5 in that only 20.1% of their respondents told their employers that they were taking days of absence due to their menstrual cycle. It is also not surprising that the vast majority of respondents reported not having any benefit provided by their employer specifically addressing issues related to their menstrual cycle. Those who had benefits available to them (5.4%) reported wellness programs, counseling, gym membership, health insurance, and paid leave as the most common options. A previous study15 collated recommendations to managers and employers from individuals with premenstrual symptoms impacting workplace productivity. These included training for staff on PMS and the availability of resources to help individuals cope with it at work. Even though we did not directly assess the impact that productivity loss and absenteeism due to issues related to the menstrual cycle may have on hiring and career progression, it is well-known that childcare responsibilities, intention to have children, as well as pregnancy may disadvantage women in the workplace.67–69 Similarly, employers may be implicitly biased by absences and reduced productivity related to issues of the menstrual cycle. Further research is needed to assess the extent to which such biases impact women's careers.

Users reported a positive impact of the Flo app on several dimensions, including management of menstrual cycle symptoms, preparedness, bodily awareness, openness with others, and feelings of support. Being prepared and aware of one's own bodily signals as well as symptom management positively impact individuals’ ability to plan ahead and cope with issues related to their menstrual cycles. To maximize positive outcomes, the adoption of digital health tools could be part of systemic changes in employer-led policies, such as flexible working environments, to allow employees to distribute workloads around their expected productivity loss. Similarly, users report that the Flo app increases their openness with others around issues related to the menstrual cycle, which could, in turn, positively influence interactions with colleagues and management. Our respondents also felt supported by the Flo app, likely due to the stigma-free environment it offers. Further research should explore the possibility of using digital health tools to facilitate discussions in the workplace around taboo topics such as menstrual health. One-third of respondents (33.2%) reported that the Flo app helped improve their mood. This finding may be due to the fact that direct links between better preparedness and awareness, improved management of symptoms, feelings of support, openness, and mood may not be explicitly perceived by our users. Further research, looking at changes in mood in a randomized controlled trial is needed to shed light on the role of Flo on individuals’ mood.

The app features our users found most useful included period predictions, symptoms tracking, fertile days predictions and symptoms, and cycle-related chats with Flo's health assistant. Interestingly, a significant difference in the most useful features was found between those who reported having taken days off work and those who did not, with the former finding symptom tracking more useful. This cohort may experience a higher impact of their symptoms on their daily activities, making it important for them to have a record of when the symptoms occurred throughout their menstrual cycle. As for productivity, the finding that cycle-related chats were more useful for users reporting a high impact on their productivity is not surprising and it suggests these users may need more support in dealing with issues related to their menstrual cycle.

Finally, we found that those who agreed that the Flo app helped them were also less likely to report a high impact of their menstrual cycle on their workplace productivity and were less likely to be absent from work. These findings suggest that the Flo app could help mitigate some of the identified issues impacting workplace productivity. To shed light on this, interventional studies, assessing the direct effects of Flo on workplace productivity, are needed.

Limitations

A limitation of the current study is that we did not ask respondents to state which symptoms impacted their productivity the most. Whilst we analyzed patterns of symptoms logged in conjunction with different phases of the menstrual cycle, we cannot draw any definitive conclusions as to their relationship with the reported impact of the menstrual cycle on productivity and absenteeism. Nevertheless, previous evidence points to the premenstrual and menstruation phases as the most impactful.5,14,60

In addition, our sample included only Flo users, who may use Flo to manage their symptoms, whereas previous studies surveyed a more general population of women who may not benefit from app-based symptom management. Similarly, only women who owned and used mobile phones were included, which may limit generalizability.

Even though we asked our users about their mode of working (on-site vs hybrid vs remote, see Table 1), we did not collect any information regarding COVID nor its sequelae. As such, it is not possible for us to draw any conclusions as to whether COVID worsened any negative effects of the menstrual cycle on workplace productivity, and further research is needed to investigate these important issues. Additionally, it has to be noted that, whilst the vast majority of our sample was working on-site at the time they answered the survey, we do not know whether their working mode was different in the 12 months prior. This is particularly relevant to the question about the number of missed days of work, so these results should be generalized with caution.

Further, the current study lacked a comparison group. Users who decided to take part in this study may be experiencing more negative symptoms than others or may use the app more regularly (thus benefiting more from it), which could impact generalizability (see Supplemental Materials for an analysis of the logging patterns in respondents versus non-respondents).

Finally, the sample only included users who paid for the premium version of the app. Evidence suggests that willingness to pay for an app or online content is related to education levels, income and perceived usefulness.70,71 Thus, users included in the present survey may need more support in terms of women's health, which might lead to overestimation of the observed effects compared to the general population.

Conclusions

Issues related to the menstrual cycle severely impact workplace productivity, with employees reporting little to no resources being available to them to properly address this important issue. Digital health apps, such as the Flo app, could fill this gap, by increasing individuals' levels of bodily awareness, preparedness, support, and symptom management. Furthermore, digital tools could facilitate discussions around menstrual health in the workplace as well as help increase health literacy in the wider employee population. To maximize their effect, digital solutions could be accompanied by systemic changes in workplace practices surrounding menstrual and women's health.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221145852 for Menstrual cycle-associated symptoms and workplace productivity in US employees: A cross-sectional survey of users of the Flo mobile phone app by Sonia Ponzo, Aidan Wickham, Ryan Bamford, Tara Radovic, Liudmila Zhaunova, Kimberly Peven, Anna Klepchukova and Jennifer L Payne in Digital Health

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Flo users who took part in the study.

Footnotes

Contributorship: All authors made a substantial contribution to the manuscript. SP, LZ, AK, and JLP designed the research. TR and RB assisted with the implementation of the research. AW, KP, and RB conducted the analysis of the results. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

SP, AW, KP, TR, RB, LZ, and AK are employees of Flo Health. JLP is a consultant for Flo Health.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Independent Ethical Review Board (WCG IRB).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

Guarantor: SP.

ORCID iD: Sonia Ponzo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6754-5078

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Avdic D, Johansson P. Absenteeism, gender and the morbidity–mortality paradox. J Appl Econom 2017; 32: 440–462. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Côté I, Jacobs P, Cumming D. Work loss associated with increased menstrual loss in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100: 683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann MA, Rockoff JE. Do menstrual problems explain gender gaps in absenteeism and earnings?: evidence from the national health interview survey. Labour Econ 2013; 24: 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armour M, Ferfolja T, Curry C, et al. The prevalence and educational impact of pelvic and menstrual pain in Australia: a national online survey of 4202 young women aged 13-25 years. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2020; 33: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoep ME, Adang EMM, Maas JWM, et al. Productivity loss due to menstruation-related symptoms: a nationwide cross-sectional survey among 32 748 women. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e026186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update 2015; 21: 762–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grandi G, Ferrari S, Xholli A, et al. Prevalence of menstrual pain in young women: what is dysmenorrhea? J Pain Res 2012; 5: 169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev 2014; 36: 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissman AM, Hartz AJ, Hansen MD, et al. The natural history of primary dysmenorrhoea: a longitudinal study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2004; 111: 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnett MA, Antao V, Black A, et al. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2005; 27: 765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka E, Momoeda M, Osuga Y, et al. Burden of menstrual symptoms in Japanese women: results from a survey-based study. J Med Econ 2013; 16: 1255–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Doan QV, Blumenthal P, et al. A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and health-care costs and utilization in abnormal uterine bleeding. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res 2007; 10: 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rapkin AJ, Winer SA. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: quality of life and burden of illness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2009; 9: 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinemann LAJ, Minh TD, Filonenko A, et al. Explorative evaluation of the impact of severe premenstrual disorders on work absenteeism and productivity. Womens Health Issues 2010; 20: 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardy C, Hunter MS. Premenstrual symptoms and work: exploring female staff experiences and recommendations for workplaces. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borenstein JE, Dean BB, Leifke E, et al. Differences in symptom scores and health outcomes in premenstrual syndrome. J Womens Health 2007; 16: 1139–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen KE, Kesmodel US, Baldursson EB, et al. The influence of endometriosis-related symptoms on work life and work ability: a study of Danish endometriosis patients in employment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013; 169: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Álvarez-Salvago F, Lara-Ramos A, Cantarero-Villanueva I, et al. Chronic fatigue, physical impairments and quality of life in women with endometriosis: a case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Della Corte L, Di Filippo C, Gabrielli O, et al. The burden of endometriosis on women’s lifespan: a narrative overview on quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod 2012; 27: 1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Reprint of: impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril 2019; 112: e137–e152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grandey AA, Gabriel AS, King EB. Tackling taboo topics: a review of the three Ms in working women’s lives. J Manag 2020; 46: 7–35. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price H. Periodic leave: an analysis of menstrual leave as a legal workplace benefit. Okla Law Rev 2022; 74: 187. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iacovides S, Avidon I, Bentley A, et al. Reduced quality of life when experiencing menstrual pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014; 93: 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unsal A, Ayranci U, Tozun M, et al. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and its effect on quality of life among a group of female university students. Ups J Med Sci 2010; 115: 138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández-Martínez E, Onieva-Zafra MD, Parra-Fernández ML. The impact of dysmenorrhea on quality of life among Spanish female university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16(5): 713. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Jefout M, Seham A-F, Jameel H, et al. Dysmenorrhea: prevalence and impact on quality of life among young adult Jordanian females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2015; 28: 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen JT, Lefebvre P, Laliberté F, et al. Cost burden and treatment patterns associated with management of heavy menstrual bleeding. J Womens Health 2012; 21: 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasiak R, Filonenko A, Vanness DJ, et al. Impact of estradiol-valerate/dienogest on work productivity and activities of daily living in European and Australian women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Int J Womens Health 2012; 4: 271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser IS, Langham S, Uhl-Hochgraeber K. Health-related quality of life and economic burden of abnormal uterine bleeding. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol 2009; 4: 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang M, Wallenstein G, Hagan M, et al. Burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder on health-related quality of life. J Womens Health 2008; 17: 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, et al. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003; 28: 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao X, Yeh Y-C, Outley J, et al. Health-related quality of life burden of women with endometriosis: a literature review. Curr Med Res Opin 2006; 22: 1787–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Facchin F, Barbara G, Saita E, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and mental health: pelvic pain makes the difference. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2015; 36: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marinho MCP, Magalhaes TF, Fernandes LFC, et al. Quality of life in women with endometriosis: an integrative review. J Womens Health 2018; 27: 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sepulcri R, Amaral V. Depressive symptoms, anxiety, and quality of life in women with pelvic endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009; 142: 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carolan S, Harris PR, Cavanagh K. Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howarth A, Quesada J, Silva J, et al. The impact of digital health interventions on health-related outcomes in the workplace: a systematic review. Digit Health 2018; 4: 2055207618770861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bradbury A. Mental health stigma: the impact of age and gender on attitudes. Community Ment Health J 2020; 56: 933–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook RJ, Dickens BM. Reducing stigma in reproductive health. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2014; 125: 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horsfall J, Cleary M, Hunt GE. Stigma in mental health: clients and professionals. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2010; 31: 450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnston-Robledo I, Chrisler JC. The menstrual mark: menstruation as social stigma. Sex Roles 2013; 68: 9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babbar K, Martin J, Ruiz J, et al. Menstrual health is a public health and human rights issue. Lancet Public Health 2022; 7: e10–e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ponzo S, Morelli D, Kawadler JM, et al. Efficacy of the digital therapeutic mobile app BioBase to reduce stress and improve mental well-being among university students: randomized controlled trial. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020; 8: e17767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pierson E, Althoff T, Thomas D, et al. Daily, weekly, seasonal and menstrual cycles in women’s mood, behaviour and vital signs. Nat Hum Behav 2021; 5: 716–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levy J, Romo-Avilés N. “A good little tool to get to know yourself a bit better”: a qualitative study on users’ experiences of app-supported menstrual tracking in Europe. BMC Public Health 2019; 19: 1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tokuda Y, Doba N, Butler JP, et al. Health literacy and physical and psychological wellbeing in Japanese adults. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 75: 411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ratnayake P, Hyde C. Mental health literacy, help-seeking behaviour and wellbeing in young people: implications for practice. Educ Dev Psychol 2019; 36: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 2002; 288: 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiss BD, Palmer R. Relationship between health care costs and very low literacy skills in a medically needy and indigent medicaid population. J Am Board Fam Pract 2004; 17: 44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, et al. Health literacy and preventive health care use among medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care 2002; 40: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bennett CL, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, et al. Relation between literacy, race, and stage of presentation among low-income patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 3101–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim H-G, Cheon E-J, Bai D-S, et al. Stress and heart rate variability: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig 2018; 15: 235–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Souza HCD, Philbois SV, Veiga AC, et al. Heart rate variability and cardiovascular fitness: what we know so far. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2021; 17: 701–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Sá JCF, Costa EC, da Silva E, et al. Analysis of heart rate variability in polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol 2011; 27: 443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dhanalakshmi Y, Pal GK, Sirisha A, et al. Assessment of heart rate variability in patients with fibroid uterus. Int J Physiol 2019; 7: 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yildirir A, Aybar F, Kabakci G, et al. Heart rate variability in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2006; 11: 306–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Speed CA, Arneil TC, Harle RK, et al. Measure by Measure: Resting Heart Rate Across the 24 Hour Cycle. 2021. 2021.11.24.21266320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Clayton AH. Symptoms related to the menstrual cycle: diagnosis, prevalence, and treatment. J Psychiatr Pract 2008; 14: 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schoep ME, Nieboer TE, van der Zanden M, et al. The impact of menstrual symptoms on everyday life: a survey among 42,879 women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019; 220: 569.e1–569.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lete I, Häusler G, Pintiaux A, et al. The inconvenience due to women’s monthly bleeding (ISY) survey: a study of premenstrual symptoms among 5728 women in Europe. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2017; 22: 354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ishibashi Y, Shimura A. Association between work productivity and sleep health: a cross-sectional study in Japan. Sleep Health 2020; 6: 270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gingerich SB, Seaverson ELD, Anderson DR. Association between sleep and productivity loss among 598 676 employees from multiple industries. Am J Health Promot 2018; 32: 1091–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taelman J, Vandeput S, Spaepen A, et al. Influence of mental stress on heart rate and heart rate variability. In: Vander Sloten J, Verdonck P, Nyssen M, et al. (eds) 4th European conference of the international federation for medical and biological engineering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2009, pp.1366–1369. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vrijkotte TGM, van Doornen LJP, de Geus EJC. Effects of work stress on ambulatory blood pressure, heart rate, and heart rate variability. Hypertension 2000; 35: 880–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, et al. Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Becker SO, Fernandes A, Weichselbaumer D. Discrimination in hiring based on potential and realized fertility: evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Labour Econ 2019; 59: 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kübler D, Schmid J, Stüber R. Gender discrimination in hiring across occupations: a nationally-representative vignette study. Labour Econ 2018; 55: 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salihu HM, Myers J, August EM. Pregnancy in the workplace. Occup Med Oxf Engl 2012; 62: 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Punj G. The relationship between consumer characteristics and willingness to pay for general online content: implications for content providers considering subscription-based business models. Mark Lett 2015; 26: 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tobias G, Sgan-Cohen H, Spanier AB, et al. Perceptions and attitudes toward the use of a mobile health app for remote monitoring of gingivitis and willingness to pay for Mobile health apps (part 3): mixed methods study. JMIR Form Res 2021; 5: e26125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221145852 for Menstrual cycle-associated symptoms and workplace productivity in US employees: A cross-sectional survey of users of the Flo mobile phone app by Sonia Ponzo, Aidan Wickham, Ryan Bamford, Tara Radovic, Liudmila Zhaunova, Kimberly Peven, Anna Klepchukova and Jennifer L Payne in Digital Health