Abstract

Background

Although ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) is a well-established, nonpharmacologic therapeutic option for patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy, its availability is still not widespread. The COVID-19 pandemic may have further restricted the access of people with pharmacoresistant epilepsy (PWE) to KDT. Thus, we evaluated the experiences of Brazilian PWE and their caregivers during the first year of the pandemic.

Methods

An online self-assessed survey containing 25 questions was distributed via social media to be answered by PWE treated with KDT or their caregivers through Google Forms from June 2020 to January 2021. Mental health was assessed using the DASS and NDDI-E scales.

Results

Fifty adults (>18 yo), of whom 68% were caregivers, answered the survey. During the pandemic, 40% faced adversities in accessing their usual healthcare professionals and 38% in obtaining anti-seizure medication (ASM). Despite these issues, 66% of those on KDT could comply with their treatment. Those struggling to maintain KDT (34%) named these obstacles mainly: diet costs, social isolation, food availability, and carbohydrate craving due to anxiety or stress. An increase in seizure frequency was observed in 26% of participants, positively associated with difficulties in obtaining ASM [X2 (1, N = 48) = 6.55; p = 0.01], but not with KDT compliance issues.

Conclusions

People with pharmacoresistant epilepsy and undergoing KDT, as well as their caregivers, faced additional challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, not only difficulties in accessing healthcare and KDT maintenance but also on seizure control and mental health.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Ketogenic diet, COVID-19, Pandemic, SARS-CoV-2, Online survey

1. Introduction

Ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) is an effective treatment for pharmacoresistant epilepsy, requiring close monitoring by a team of healthcare professionals to guarantee compliance, and manage potential side effects, often demanding quick access to specialized in-hospital care [1], [2]. Despite that, KDT has limited availability in some regions of the world [1].

Nevertheless, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted multiple aspects of life, and social distancing and lockdown measures have become essential methods to mitigate the spread of the virus. In addition to daily risks of exposure, the odds of contracting the virus in a healthcare facility have increased, with even greater challenges for people with chronic conditions such as epilepsy [3]. Furthermore, diminished access to healthcare could limit the availability of anti-seizure medication (ASM) and KDT maintenance, which could impact mental health. It could be particularly concerning for people with pharmacoresistant epilepsy (PWE), who frequently require more constant follow-up [3], [4].

Brazil is the first Latin American country with COVID-19 cases, which registered its first case on February 26, 2020, and quickly became the country with the second-highest number of COVID-19-related death cases in the world [5]. It is a resource-poor country facing profound social, economic, and political inequalities and hardships. These challenges for PWE undergoing KDT and their families/caregivers could be even more profound. Access to healthcare units, food availability, and digital inclusion may be crucial for maintaining care during the pandemic [4]. However, the literature on these aspects is scarce.

Therefore, our study evaluated the healthcare assistance delivered to PWE under KDT and their families/caregivers in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings aim to help develop feasible solutions that are adapted to the regional reality and prepare for future similar events.

2. Material and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted through the online survey platform Google Forms during the first year of the pandemic in Brazil (June 2020–January 2021). The survey was aimed at PWE and their caregivers who reside in Brazil, with no restrictions on age, disease duration, or whether the diagnosis was provided during the pandemic.

2.1. Instruments

The survey was distributed through social media, with support from stakeholder organizations, including the Associação Brasileira de Epilepsia (ABE) and Liga Brasileira de Epilepsia (LBE). In addition, physicians and nutrition professionals were invited to ask their patients on KDT to participate. The questionnaire was specifically designed for this project and consisted of 25 multiple choices and few open questions, which were later categorized. It could be responded by the individual with epilepsy or their caregivers, in the case of underaged PWE, which is most people on KDT in Brazil. The questionnaire addressed the following domains:

-

a.

Demographics: Respondents’ (whether PWE or caregiver) age, sex, city of residence, household financial circumstances before and after the pandemic, and employment and educational level.

-

b.

Epilepsy characteristics: Duration of the disease, changes in seizure frequency, and treatment modality.

-

c.

Healthcare access during the pandemic: Respondents were asked if they had and which were the difficulties in accessing healthcare facilities, physicians, and ASM, and in maintaining KDT (caregivers responded on behalf of the PWE they cared for).

-

d.

KDT: Respondents were asked about difficulties in continuing KDT both before and after the pandemic (caregivers responded on behalf of the PWE they cared for).

-

e.

Mental Health Assessment: The Brazilian-Portuguese version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) [6] and the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS 21) [7] for the general population were used. Answers provided by caregivers were considered a reflection of their mental health (DASS-21, in which we included responses from both patients and caregivers). To assess PWE, we considered answers provided directly by them (NDDI-E, specific for the population with epilepsy).

NDDI-E ranked, on a scale of four, from “Never” to “Always or Frequently” the experiences PWE had in the past 30 days. The cutoff point used to determine major depressive symptoms was >15 [8]. It is a self-reported scale only aimed at PWE; therefore, we did not analyze caregivers’ responses on the NDDI-E scale.

The DASS 21 contains three subscales evaluating depression (DASSd), anxiety (DASSa), and stress (DASSs) states [9]. Each subscale contains seven questions, and scores are calculated separately based on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 3. The points are summed up and then multiplied by two [9]. This scale was adopted in this study, assessing 30 days before the survey was conducted, whereas the original scale evaluates a previous period of 1 week [9]. The mental health of both caregivers and PWE were assessed using this scale.

Additionally, we evaluated concerns regarding the pandemic through a 5-point Likert scale created by the researchers, ranging from “Not worried” to “Extremely worried.”

-

f.

Changes in lifestyle due to COVID-19: Those diagnosed with COVID-19 infection, whether the caregiver, the patient, or other family members, and their willingness to adhere to preventive measures and need for assistance during the pandemic were also surveyed.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were based on treatment modality and place of residence. Therefore, only those who reported KDT as treatment alone or combined with other modalities and living in Brazil were included in the study. All other answers, duplicates, and incomplete answers were excluded from our analysis.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS® Statistics Grad Pack software Premium version 27.0. Qualitative variables are expressed as absolute or relative frequencies. Quantitative variables were defined as measures of central tendency and measures of data dispersion. The normality of the data was analyzed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The association between two variables was determined using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Finally, a comparison between two groups was performed using Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney test, or Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

2.4. Ethics

This study was carried out under the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki, 2014). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee (Coordinating center – CEPSH/UFSC Protocol Approval No. 4.059.818). All subjects voluntarily agreed to participate and completed the consent form on the first page of the questionnaire before proceeding to the survey.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

After removing duplicate and incomplete answers (N = 8) and considering the inclusion criteria of PWE on KDT, 50 responses were included in this study. Replies were received from four of the five Brazilian geographical regions, and the majority were from the Southeast (62%) and South (18%) regions (Fig. 1 ). Most participants were female (32 [64%]), and the average age was 35.60 years (SD = 10.89). The mean epilepsy duration was 12.62 years (SD = 10.61). Caregivers provided most responses on the patient’s behalf [34 (68%)], and 16 (32%) PWE answered the survey themselves.

Fig. 1.

Answers per Brazilian geographical regions (%).

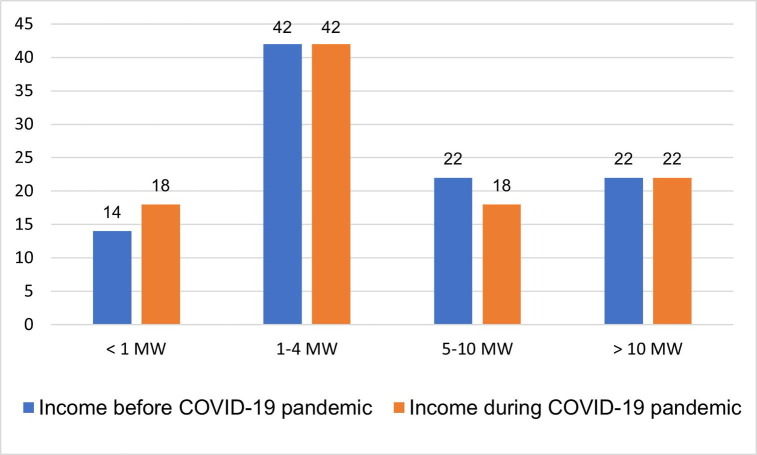

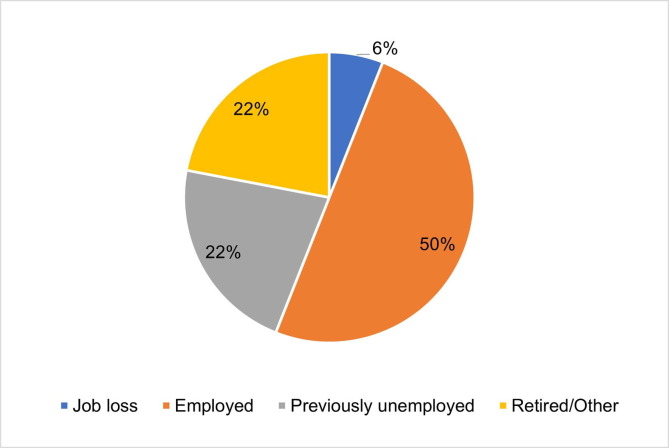

Regarding employment and financial status, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed no significant changes in overall household income (T = 9, z = −1.73, p = 0.08), and only three participants (6%) reported job loss during the pandemic. In addition, the majority (84%) had at least a primary level education, and 72% had completed high school. Regarding Internet access, 43 (86%) participants had access to a connected computer, and 48 (96%) owned a smartphone with Internet connection. The participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 1 and Fig. 2, Fig. 3 .

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of respondents.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 50) |

|---|---|

| Age, yearsa | 35.60 ± 10.89 (1–57) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 32 (64) |

| Subjects, n (%) | |

| Patients | 16 (32) |

| Disease duration, yearsa | 12.62 ± 10.61 (1–46) |

| Treatment, n (%) | |

| Ketogenic diet | 50 (100) |

| Ketogenic diet only | 3 (6) |

| Anti-seizure medication | 47 (94) |

| Vagus nerve stimulation | 4 (8) |

| Cannabidiol | 1 (2) |

| Previous surgery | 1 (2) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| No formal education | 8 (16) |

| Elementary school | 5 (10) |

| High school | 9 (18) |

| Graduate | 12 (24) |

| Post-graduate | 16 (32) |

mean ± SD (minimum – maximum).

Fig. 2.

Household income before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (%). MW = minimum wage in Brazil, equivalent to US$ 183.00.

Fig. 3.

Occupational status of respondents during the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to the pre-pandemic period.

3.2. COVID-19 pandemic impact on seizures and treatment

When asked about seizure frequency, 56% reported no change during the pandemic, 26% reported an increase, 6% reported a decrease, and 12% reported that they did not know. During the pandemic, only 34% faced challenges in continuing KDT. In comparison, 38% reported difficulties in obtaining medication, of which 47% indicated a shortage in availability, and 47% had no access to prescription or could not get the usual free samples from their doctor. The chi-square test showed an association between difficulties in accessing medication and increased seizure frequency (X2 [1, N = 48] = 6.55; p = 0.01). However, the Fisher's exact test showed no association between difficulties in accessing KDT and increased seizure frequency (X2 [1, N = 49] = 1.03; p = 0.33).

Access to customary healthcare facilities and professionals was impaired in 20 (40%) PWE, the most common cause being the suspension of elective consultations for 18 (90%) of these patients.

Regarding KDT specifically, when asked to select from a list of difficulties to answer, “Which was your major difficulty with KDT before the pandemic?”, 46% of the respondents indicated that they had no problems. For those (54%) who identified their major compliance barriers, diet cost (37%) and adverse effects (22%) were the main impediments. During the pandemic, 34% of respondents openly reported difficulties in maintaining KDT, such as diet cost (41%), impaired access to markets due to restrictive measures/social isolation (18%), and increased consumption of carbohydrates due to anxiety or stress (23%).

3.3. COVID-19 infection, prevention, concerns, and necessary assistance

Three PWE (6%) had COVID-19 symptoms; however, they were not tested. Only one respondent was confirmed to have COVID-19 but reported no change in seizures during the infection period. Concerning COVID-19 preventive measures, all participants reported wearing masks when leaving their homes, 94% were in social isolation, 98% kept a minimum distance of 1–2 m from other people, and 98% washed their hands more frequently.

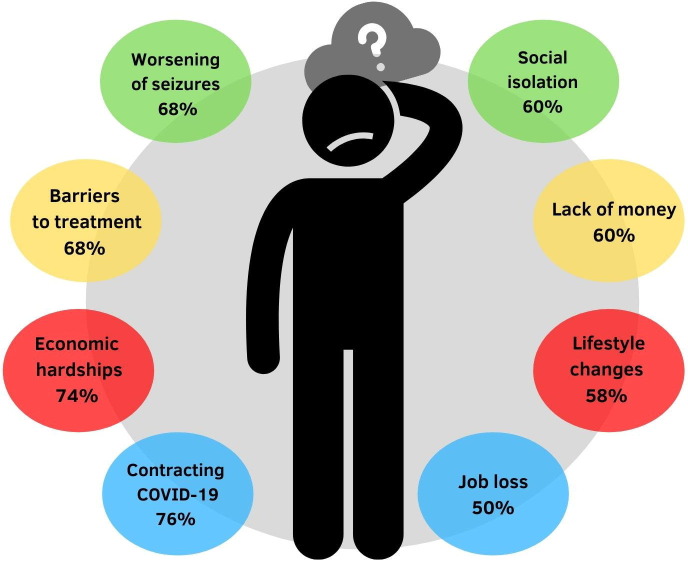

Regarding the pandemic, the main concerns – to which the majority responded to be very or extremely worried – were contracting COVID-19, economic hardships, barriers to treatment, worsening of seizures, social isolation, lack of money, lifestyle changes, and job loss (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Main concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When asked to select from a list of demands that they would consider necessary during the pandemic, the majority of respondents would like to have better access to online medical prescriptions (76%), updated and unbiased COVID-19 information (62%), home delivery of medication (52%), and medical counseling over the phone (42%) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Main demands of people with epilepsy on Ketogenic Diet Therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| List of requirements/demands | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Access to online medical prescriptions | 38 (76) |

| Updated COVID-19 information | 31 (62) |

| Home-delivery of medication | 26 (52) |

| Medical counseling over the phone | 21 (42) |

| Access to seizure detectors | 17 (34) |

| Online self-help programs | 16 (32) |

| Psychological help | 15 (30) |

| Food donation | 9 (18) |

| Financial assistance | 9 (18) |

3.4. Mental health during the pandemic

The mean overall NDDI-E score was 13.88 (SD = 5.24), below the cutoff point for a “Major Depression Disorder” diagnosis, but 38% of PWE had a score of >15. Overall mean DASS anxiety, depression, and stress scores were 12.92 (SD = 11.74), 12.88 (SD = 11.74) and 19.40 (SD = 13), respectively (Table 3 ). Severe or extremely severe anxiety was reported by 44% of PWE, severe or extremely severe depressive symptoms by 37%, and severe or extremely severe stress by 50%.

Table 3.

Results of mental health assessments.

| Scales | PWE (N = 16) | Caregivers (N = 32) | Mean scoresb |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDDI-E > 15, n (%) | 6 (37) | N/A | 13.88 ± 5.24 (6–22) |

| DASS anxiety, n (%) | |||

| Normal (0–7)a | 5 (31) | 17 (41) | 12.92 ± 11.74 (0–42) |

| Mild (8–9)a | 1 (6) | 1 (3) | |

| Moderate (10–14)a | 3 (19) | 7 (21) | |

| Severe (15–19)a | 1 (6) | 1 (3) | |

| Extremely severe (20+)a | 6 (37) | 8 (23) | |

| DASS depression, n (%) | |||

| Normal (0–9)a | 5 (31) | 17 (41) | 12.88 ± 11.74 (0–42) |

| Mild (10–13)a | 1 (6) | 6 (18) | |

| Moderate (14–20)a | 4 (25) | 3 (9) | |

| Severe (21–27)a | 1 (6) | 4 (12) | |

| Extremely severe (28+)a | 5 (31) | 4 (12) | |

| DASS stress, n (%) | |||

| Normal (0–14)a | 3 (19) | 13 (38) | 19.40 ± 13 (0–42) |

| Mild (15–18)a | 2 (12) | 7 (21) | |

| Moderate (19–25)a | 3 (19) | 4 (12) | |

| Severe (26–33)a | 3 (19) | 7 (21) | |

| Extremely severe (34+)a | 5 (31) | 3 (9) |

aCutoff point for each scale.

bmean ± SD (minimum – maximum).

The independent t-test showed no differences in mean scores between the sexes. Furthermore, the PWE group presented higher mean DASS depression subscale scores than the caregiver group, t(48) = 2.14, p = 0.04. No significant differences were found for the other DASS subscales.

Those with difficulties in accessing KDT healthcare during the pandemic presented higher DASS scores compared to those with no difficulties: t(47) = −3.06, p = 0.00; t(47) = −2.06, p = 0.045; and t(47) = −3.54, p = 0.00 for DASSd, DASSa, and DASSs, respectively. The analysis of NDDI-E for these patients with difficulties showed no significant difference compared with others: t(14) = −2.124, p = 0.052. For those with restricted access to medication, mean scores were greater at every scale: t(12) = −2.51, p = 0.03; t(46) = −11.41, p < 0.001; t(28.72) = −12.91, p = 0.00; and t(46) = −12.71, p = 0.00 for NDDI-E, DASSd, DASSa, and DASSs, respectively.

4. Discussion

Although well established in some Brazilian regions, the KDT is still not routinely offered in resource-limited settings. Few dedicated epilepsy centers in Brazil are mainly provided to pediatric patients. In addition, the country is facing social and economic hardships in containing the COVID-19 pandemic [5], possibly restricting PWE’s and caregivers’ access to healthcare facilities, and few national data on the matter are available [4]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first national survey evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health assistance and the socio-economic and mental health status of PWE under KDT. Difficulties in obtaining prescribed medication, accessing healthcare professionals, and maintaining KDT were the main findings of the present study. We also found that the mental health of PWE and caregivers was compromised.

Ketogenic diet therapy follow-up issues were reported by 54% of patients, even before the pandemic. Consistent with a previous study conducted in Brazil during this period [4], we found that food cost was the main barrier to those who had difficulties with KDT continuation, both during (41%) and before (37%) the pandemic. Its significant worldwide socioeconomic impacts may have worsened this situation [10], interfering with food availability and prices [11]. Indeed, food availability issues (18%) were reported alongside difficulties in accessing food establishments due to social isolation measures (18%), as was also found by Kossoff et al. [12]. Mental health also influenced KDT continuation as four (23%) patients increased their carbohydrate intake due to anxiety or stress, indicating the necessity to adapt the diet to their needs [12].

Despite that, 66% of the responders had no issues during the pandemic with KDT maintenance. Furthermore, a recent study in Canada [13] evidenced that PWE, who initiated KDT, experienced decreased emergency department visits and inpatient visits, and healthcare costs. Additionally, KDT is becoming a rising trend in resource-limited countries, with successful experiences in Egypt [14] and Zambia [15].

Mental health during the pandemic was assessed using two different scales. We found that more than one-third of PWE was screened positive for depression on the NDDI-E scale. The DASS 21 scale showed that 37%, 43%, and 50% of PWE had severe or extremely severe depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. We could not evaluate whether the pandemic increased these rates for PWE because previous data were unavailable, nor their association with KDT due to lack of controls (without KDT). Although our results indicated a significant association between difficulties in maintaining KDT and higher scores on the DASS 21 scale, the same was observed for those who had impaired access to medication, including higher scores on the NDDI-E scale.

Amidst the pandemic, knowing which kind of assistance is required by PWE and caregivers is essential and challenging for the healthcare provider. We found that access to online prescriptions (76%), home delivery of medication (52%), and medical counseling over the phone (42%) were the main demands. In addition, 62% deemed updated COVID-19 information as necessary, elucidating the significant amount of data (infodemics), especially from the media and the Internet, as a possible source of confusion and anxiety [16], considering the current trends of false or ambiguous information, including those regarding KDT [17]. These types of support would facilitate access to healthcare, avoid exposure to COVID-19, and aid in maintaining tranquility and adequate prevention against the virus. Nonetheless, food donation and financial help were the least needed, despite food costs being the primary impairment to KDT continuation.

Concerning these challenges and needs, telehealth is an emerging tool that healthcare professionals can use to guide food costs and reliable information on COVID-19, renovate ASM prescriptions, and assess mental health. The literature supports the use of telemedicine during this period, reporting successful outpatient follow-up, with consultations through online platforms and close contact via email, phone, or text [12]. WhatsApp, an accessible online messaging platform, was an interesting option for KDT management, with high acceptability rates [18]. In Brazil, a KDT center presented solutions to maintain KDT and renew ASM prescriptions such as communication via calls, WhatsApp messaging, and email. They also developed booklets to aid patients with the diet, providing suggestions for cheaper brands and lists of food substitutes because they also found food costs to be an issue [4].

Nevertheless, internet connection and adaptability [4] and monitoring of biomarkers, anthropometric measures, and body composition are challenges in telemedicine [4], [12]. Therefore, these issues, alongside patients' social and economic realities, must be considered when using these tools. In Brazil, for example, governmental policies to provide internet access to chronically ill patients and meal distribution programs would be interesting solutions to continue their care [4]. Furthermore, providers need to customize healthcare delivery [19] and provide a safer environment to overcome barriers, so people with pharmacoresistant epilepsy could participate in face-to-face consultations, when required, to check exams and nutritional status in KDT.

Some limitations of this study need to be addressed. First, online self-assessment questionnaires may have selection bias inherent to this methodology, such as the accuracy of their answers (e.g., whether all patients met the diagnostic criteria for pharmacoresistant epilepsy, as preconized by the International League Against Epilepsy [ILAE]) [20]. Second, the sample was small, comprising 50 respondents, related to the fact that KDT is still a developing therapeutic option in a large portion of Brazil. Third, as most PWE under KDT in Brazil are pediatric patients, most of our respondents were their parents or caregivers. It could explain why our samples’ mean age was higher [35.60 years (SD = 10.89)]. Fourth, we obtained a general overview of respondents and their households – and, when specified, in some cases, we could not attest whether the answers provided by caregivers concerned their personal information or the patients’, such as age and sex. We considered that caregivers’ responses regarding epilepsy, difficulties, and treatment were provided based on data from the PWE they cared for. Fifth, geographic distribution was also a limitation because most respondents were from Southern and Southeast regions and those with Internet access. Therefore, our findings may not be representative of the Brazilian PWE population on KDT. Lastly, respondents were required to answer the NDDI-E and DASS instruments in the last 30 days. We considered it a more reliable period, subject to lower recall bias, in contrast to their original description.

5. Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, participants reported difficulties accessing healthcare and ASM while maintaining the KDT; for the latter, the primary impairment was food cost, both before and after the pandemic. The main demand during this period was access to online ASM prescriptions and reliable COVID-19 information. Mental health was also poorer in those who reported difficulty accessing their medication and/or maintaining KDT. An increase in seizure frequency was observed to be related to access to ASM but not to KDT issues. Finally, access to healthcare via telemedicine could be one solution, allowing healthcare providers to guide and support PWE and caregivers. In a resource-poor country like Brazil, coordinated action at all levels of the healthcare system is crucial for the continuous care of PWE.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

KL holds a CNPq (Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technologic Development, Brazil) PQ2 Research Fellowship (Process No. 313205/2020-5) and is supported by PRONEM (Programa de Apoio a Nucleos Emergentes – KETODIET – SC Project – Process No. 2020TR736) from FAPESC/CNPq, Santa Catarina, Brazil. We are deeply grateful for all the support from Associação Brasileira de Epilepsia (ABE) and Liga Brasileira de Epilepsia (LBE) for helping us disseminate this survey among its associates. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the Support for Scientific and Technological Research Foundation of Santa Catarina State (FAPESC) and the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technologic Development (CNPq), Brazil [Process No. 2020TR736].

Declaration of interest

None.

References

- 1.Kossoff E.H., Al-Macki N., Cervenka M.C., Kim H.D., Liao J., Megaw K., et al. What are the minimum requirements for ketogenic diet services in resource-limited regions? Recommendations from the International League Against Epilepsy Task Force for Dietary Therapy. Epilepsia. 2015;56:1337–1342. doi: 10.1111/epi.13039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin-McGill K.J., Jackson C.F., Bresnahan R., Levy R.G., Cooper P.N. Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001903.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.French J.A., Brodie M.J., Caraballo R., Devinsky O., Ding D., Jehi L., et al. Keeping people with epilepsy safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology. 2020;94:1032–1037. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lima M.C., Sander M., dos Santos Lunardi M., Ribeiro L.C., Rieger D.K., Lin K., et al. Challenges in telemedicine for adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy undergoing ketogenic diet treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the public healthcare system in Brazil. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;113:107529. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallal P.C. SOS Brazil: Science under attack. Lancet. 2021;397:373–374. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00141-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Oliveira G.N.M., Kummer A., Salgado J.V., Portela E.J., Sousa-Pereira S.R., David A.S., et al. Brazilian version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19:328–331. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vignola R.C.B., Tucci A.M. Adaptation and validation of the depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS) to Brazilian Portuguese. J Affect Disord. 2014;155:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilliam F.G., Barry J.J., Hermann B.P., Meador K.J., Vahle V., Kanner A.M. Rapid detection of major depression in epilepsy: a multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:399–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70415-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antony M.M., Bieling P.J., Cox B.J., Enns M.W., Swinson R.P. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess. 1998;10:176–181. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., et al. The socioeconomic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jafri A., Mathe N., Aglago E.K., Konyole S.O., Ouedraogo M., Audain K., et al. Food availability, accessibility and dietary practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-country survey. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:1798–1805. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kossoff E.H., Turner Z., Adams J., Bessone S.K., Avallone J., McDonald T.J.W., et al. Ketogenic diet therapy provision in the COVID-19 pandemic: dual-center experience and recommendations. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;111:107181. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiting S., Donner E., Ramachandran-Nair R., Grabowski J., Jetté N., Duque D.R. Decreased health care utilization and health care costs in the inpatient and emergency department setting following initiation of ketogenic diet in pediatric patients: the experience in Ontario, Canada. Epilepsy Res. 2017;131:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerges M., Selim L., Girgis M., Ghannam A.E., Abdelghaffar H., El-Ayadi A. Implementation of ketogenic diet in children with drug-resistant epilepsy in a medium resources setting: Egyptian experience. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2019;11:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nkole K.L., Kawatu N., Patel A.A., Kanyinji C., Njobvu T., Chipeta J., et al. Ketogenic diet in Zambia: managing drug-resistant epilepsy in a low and middle income country. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2020;14:100380. doi: 10.1016/j.ebr.2020.100380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hao X., Zhou D., Li Z., Zeng G., Hao N., Li E., et al. Severe psychological distress among patients with epilepsy during the COVID-19 outbreak in southwest China. Epilepsia. 2020;61:1166–1173. doi: 10.1111/epi.v61.610.1111/epi.16544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amsalem D., Dixon L.B., Neria Y. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak and mental health. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Semprino M., Fasulo L., Fortini S., Martorell Molina C.I., González L., Ramos P.A., et al. Telemedicine, drug-resistant epilepsy, and ketogenic dietary therapies: a patient survey of a pediatric remote-care program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112:107493. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subotic A., Pricop D.F., Josephson C.B., Patten S.B., Smith E.E., Roach P. Calgary Comprehensive Epilepsy Program Collaborators. Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being and virtual care of patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;113:107599. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwan P., Arzimanoglou A., Berg A.T., Brodie M.J., Allen Hauser W.A., Mathern G., et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1069–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]