Abstract

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has dramatically affected the aviation industry. This paper investigates how 20 European airlines communicated their crisis messages during the pandemic by employing Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) to airline responses. This qualitative study consisting of a systematic review and content analysis, examined 7237 messages from social media channels and press releases posted between December 1, 2019, and May 25, 2020, when the crisis unfolded worldwide. The results indicate that the airlines primarily emphasized instructing and adjusting crisis communication strategies. Further, Twitter replaced Facebook as the primary communication channel. This study provides insights on how airlines can and should communicate crisis-related messages amidst a severe pandemic. The study concludes with the implications of these findings and recommendations for airline stakeholders moving forward.

Keywords: Airline industry, COVID-19, Crisis communication, Situational crisis communication theory, Twitter, Facebook

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak originated from a market in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 (Federal Office of Public Health, 2020). The virus COVID-19 belongs to the family of other known coronaviruses, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS; Federal Office of Public Health, 2020). The virus is spread through droplets from person to person and is highly contagious. Scientists warn that discovering a vaccine will take time, at least 18 months (“When will a coronavirus vaccine be ready?” 2020). Due to the reasons mentioned above, most countries worldwide have implemented strict measures to protect their citizens, such as travel restrictions, border closures, quarantines, and social distancing (Deloitte, 2020). Gallego and Font (2020) argue that within the first six months, COVID-19 has proven to be the most damaging pandemic in recent history, and it is the first virus that has caused a global recession (Ozili and Arun, 2020).

With the unprecedented outbreak of COVID-19, the airline industry has experienced the most profound crisis in history, with passenger traffic significantly decreasing. (Gössling et al., 2020). 90% of the airlines worldwide have been grounded, with an estimated global industry loss of $252 billion in 2020 (Ellis et al., 2020). The industry's ultimate impact and effect are yet unknown, and it may take the airline industry several years if not longer, to fully recover. The airline industry has been negatively affected by the COVID-19 outbreak since governments closed their borders. Travel restrictions have severely affected flight schedules; large airlines, such as Lufthansa, have canceled half of their flights in April 2020 (“Coronavirus is grounding,” 2020). While Lufthansa requested financial aid, SAS Scandinavia had to lay off 90% of their staff (ibid). The economic impact of this global crisis on the industry is unknown, but many economists argue that the entire industry is at stake, and not all companies will survive (ibid). Due to the novelty of the topic, the airline industry's coronavirus-related crisis has not been extensively researched; thus, it is not evident how companies should act amid a severe pandemic. This gap is addressed in the current project.

Before COVID-19, the airline industry had endured other global health crises, such as the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS; IATA, 2020). Before COVID-19, SARS had caused the most impact on the aviation industry. However, experts argue that COVID-19 will have a longer-lasting effect on the industry than any other pandemics (IATA, 2020). Apart from epidemics, the airline industry has experienced several other challenges and crises daily, especially with the emergence of social media and the introduction of in-flight connectivity (IATA, 2016). If mishandled, these issues have the potential to severely dent an airline's established reputation. Thus, the airline industry must be well-prepared to handle crises due to the high public exposure.

Most of the existing research on the aviation industry's response during a pandemic has focused on the accessibility of the airline network and the propagation of airborne diseases (Bowen and Laroe, 2006; Ferrell & Agarwal, 2018). Due to the novelty of the COVID-19 crisis, studies have mainly focused on the impact of COVID-19 on the aviation industry, the links between the medium- and the long-term effects, and labor-related issues (Cugueró-Escofet, Suau-Sanchez and Voltes- Dorta, et al., 2020; Sobieralski, 2020). However, little research has been conducted on the interrelationship between crisis communication and epidemics, which can trigger a public relations crisis and negatively impact the corporate reputation (Yu et al., 2020). Although research on crisis communication in the airline industry exists, it mainly focuses on airline disasters and not responses to a pandemic (Greer and Moreland, 2003; Canny, 2016; Othman and Yusoff, 2020). Further, most of the epidemics and economic crises that airlines have weathered in the past occurred when social media and digital technology were not as prevalent as today. This explains the lacuna in research and justifies the need to assess airlines' communication strategies during a pandemic.

To address one research gap, this study examines the crisis communication modalities in the pre-crisis and crisis response phases from December 1, 2019, to May 25, 2020, of 20 airlines in Europe in light of the global COVID-19 outbreak to gauge the effectiveness of their ‘crisis’ messages. Through an analysis of the airlines' messages and preferred communication channels, the researchers aim to establish a link between the messages and the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) strategies posited by Coombs (2007) to identify how the airline industry should communicate during a severe crisis. While a recent study by Albers and Rundshagen (2020) conducted a similar analysis, they focused on news items instead of the social media and press release messages in the current study. They also applied Wenzel's typology of crisis response strategies, while this study employs Coombs's SCCT theories. Thus, this paper attempts to contribute to the literature on crisis communication messages by analyzing messages posted by the top 20 European airlines in the spring months of 2020 to gauge their effectiveness as crisis response strategies. Two specific research questions were posited:

RQ1: Have the European airlines communicated correctly according to the SCCT?

RQ2: What is the preferred communication channel for disseminating the crisis response strategy in the airline industry?

This paper aims to fill the gap in current research by providing a novel insight into crisis communication, particularly that of European airlines and how they communicated with their stakeholders amid the COVID-19 outbreak. The communication strategies were evaluated based on the airlines’ most popular social media channels. This included all social media posts from December 1, 2019, to May 25, 2020. Thus, this research serves to fulfill a research gap and help researchers further widen their horizons in the tourism and aviation industries. This study concludes with recommendations for action and theoretical implications of this study.

2. Crises and crisis communication

A crisis can be qualified as an unforeseen adverse event that requires immediate action by the organization and can harm a company's reputation by undermining its emergency procedures during an unforeseen outbreak (Claeys, 2017; Coombs, 2007). Moreover, public safety, financial loss, and reputation damage are three related threats that a company may experience (Coombs, 2014a). Coombs (2007) maintained that stakeholders make “attributions” about the possibility of a crisis, which affects the way they think, perceive, and interact with the organization. Thus, attribution theory posits that people are continually searching for the source or entity that is to be held culpable, especially if the crisis is unexpected or has a significant adverse effect on them (Coombs, 2007). Hence, leaders within a company must understand crisis responsibility and anticipate the possible attributions of the public.

One framework to understand the basic principles of crisis communications is SCCT, which argues that an effective response to the crisis depends on assessing the situation and the associated reputational threat (Coombs, 2007). Moreover, Coombs (2007) introduced ways to support this assessment by defining three types of crisis: 1) victim, i.e., where the organization is seen as a victim of the crisis (e.g., rumors, natural catastrophes), and results in a minor reputational threat; 2) accident, i.e., where the organization's actions were unintentional (e.g., the failure of equipment, charges from external stakeholders), leading to a medium reputational threat; and 3) intentional, i.e., where the organization knowingly took an unacceptable risk, resulting in a significant reputational threat. Once the organization defines the crisis type, SCCT suggests employing effective crisis response strategies.

SCCT states that before selecting a crisis response option, the organization should release general information on the crisis and instructing information about public safety measures (Coombs, 2007; Kim and Liu, 2012). The immediate crisis response strategy consists of three clusters (Coombs, 2007). The first is the deny cluster, where the organization rejects responsibility and denies any connection between the crisis and the organization or blames another organization or person for the crisis. The second group is the diminish cluster in which an organization attempts to decrease its responsibility for the crisis or the resulting damages. The third group is referred to as the rebuild cluster, in which they admit responsibility and offer compensation or apologies to the victims and stakeholders involved in the crisis. This strategy attempts to offset the negative attribution with corrective action (Coombs, 2007). The secondary crisis response strategy supports the three primary strategies to diminish the adverse effects and correct accusations and misleading information (Coombs, 2007). The secondary crisis response strategy consists of reminder strategy (e.g., remind the stakeholders about the company's past good work), ingratiation strategy (e.g., praise stakeholders on their good deeds), and victimage strategy (e.g., remind stakeholders that the organization is a victim of the crisis (Coombs, 2007). Finally, its prior reputation and crisis history may positively or negatively affect a reputational threat.

A company's crisis history consists of the crisis management strategies utilized by it. Crisis management includes three different phases: Pre-crisis, crisis response, and post-crisis, comprising different activities: Preventing crises, responding to them, and gaining knowledge from past crises (Coombs, 2014a). Thus, when an organization experiences a crisis, it should be mindful of the crisis type and its crisis history while formulating an appropriate crisis response strategy.

Coombs’ (2007) SCCT has been applied in the context of the airline industry. For example, Canny (2016) used the SCCT to analyze how the Lufthansa Group responded to a crisis in 2015 when an Airbus A320-211 carrying 150 people crashed in the French Alps. Using the SCCT as a theoretical lens, Canny (2016) analyzed communication through media channels and explored crisis response strategies. A recent study by Othman and Yusoff (2020) employed the SCCT to examine the crisis management strategies used by Malaysia Airlines during the MH370 crisis. Overall, the SCCT framework helps entities to anticipate how stakeholders will react to the crisis response strategies used during a crisis.

2.1. Communicating during a crisis

The communication strategy called stealing thunder proposes to proactively release crisis information when a company experiences a crisis (Lee, 2016). Research shows that when an organization steals the thunder, the company becomes a source of information and can lead and control its flow (Claeys, 2017; Lee, 2016). This garners more favorable attention from the public and journalists (Lee, 2016) and ensures that the public perceives the organization as ethical (Claeys, 2017).

2.1.1. Social media

Researchers reported that discussions about wrongful accusations and rumors could spread quickly and reach a broad audience when conducted on social media platforms (Cameron and Cheng, 2018; Grančy, 2014). This can trigger a severe “para-crisis” that can harm its reputation (Cameron and Cheng, 2018; Coombs, 2014b). Social media platforms have also increased the probability of crises being disclosed by internal and external stakeholders (Claeys, 2017). Stakeholders are prioritized according to their importance for reaching their objectives (Mootien et al., 2013). In the airline industry, stakeholders include airports, airlines, consumers, manufacturers, interest groups, shareholders, the media, interest groups, suppliers, and governing institutions. Claeys (2017) argues that the public will eventually find information on a crisis through other sources if it is not officially revealed by the organization, resulting in the company losing its credibility. Thus, stealing thunder is essential for a company, especially with social media and its increased communication pace. Previous studies have shown that an organization must choose the right channel when dealing with a crisis. The right stakeholders need to be reached, and the potential problem addressed promptly (Coombs, 2018; Göritz et al., 2011). Moreover, Göritz et al. (2011) found that the communication channel is more critical for maintaining a company's reputation than the content of the message.

Social media's role in crisis communication in the airline industry has been widely recognized. For instance, the International Air Transport Association has introduced airline companies' best practices (IATA, 2016). One recommendation is to develop a social media policy by taking immediate action in the middle of a crisis. Coombs (2014b), in turn, argued that social media could be helpful during crises because they allow customers to vent, thus releasing tension. An excellent example of this approach is Qantas Airlines and its Twitter campaign (Coombs, 2014b). Qantas had a Twitter campaign about luxury vacation; however, the campaign did not have the desired effect among customers. The customers' comments were not about luxury vacations; instead, they included angry statements about recent labor disputes. Coombs (2014b) argues that stakeholders must have their say.

Facebook is the largest social networking site, with over two-and-a-half billion active users (Statista, 2020). Nearly one-third of the world's population has an account on Facebook. Instagram has a primarily younger audience, with over a billion active users (Statista, 2020). With over 575 million users, LinkedIn is a platform for business professionals and companies (Egan, 2017). Twitter is a microblogging service with over 386 million users globally (Statista, 2020). Google-owned YouTube is the largest video platform, with 2.2 billion users globally, and it is the second most prominent social media network (Egan, 2017; Statista, 2020). Unlike Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn, which have textual content, YouTube is a video-based platform. However, Pinterest was excluded Pinterest from the analysis. Pinterest, a picture-sharing channel where users can find inspiration and ideas, is more of a visual search engine than a communication channel (Egan, 2017).

Research shows that European airlines’ most popular social media channels are Facebook, followed by Twitter and LinkedIn (Bick, Bühler and Lauritzen, 2014). This study extends previous research projects by examining Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, and Instagram to create a more holistic vision of how and where European airlines communicated crisis-related messages.

3. Data collection and analysis

A qualitative research approach was used to conduct this research. Qualitative data includes validating information obtained through organizing the data, coding, and interpreting themes. The researchers conducted an in-depth analysis of social media content through open coding to reveal patterns in the data (Cascio et al., 2019) which is essential for devising themes and concepts concerning the research topic. Some researchers may argue that grounded theory has its limitations, as it is difficult for researchers to prevent researcher-induced biases (Timonen et al., 2018) and researchers may use their judgment to find themes. This is perhaps the most significant criticism of this theory that the data analysis is not scientific (deductive) but based on inductive reasoning, drawn from the data analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 2017). To overcome this challenge, Glaser and Strauss (2017) suggested the constant comparative method. This method combines the coding and analytic procedures and allows a more systematic approach (Glaser and Strauss, 2017). Moreover, the constant comparative method permits the researcher to continually validate their thinking (Glaser and Strauss, 2017), which was the case in this study.

The constant comparative method, along with the single coding approach, has been implemented in this research to limit the threats to reliability and validity.

3.1. Methods

This research focused on 20 representative European airlines selected based on their annual income (Ishak, 2019). The selected airlines have extensive experience in the industry and provide a reliable data source for the present study (Wiesche et al., 2017). For data collection and analysis, NVivo 1.2 (Mac version) was used. According to the results, effective channels of the airlines’ crisis communication derived from the following five social media platforms: Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and LinkedIn (see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Social Media Channels and Followers.

| Social Media Channel | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airlines | YouTube | Total | |||||

| 1 | KLM | 14 million | 1.3 million | 586,945 | 2.3 million | 191,000 | 18 million |

| 2 | Turkish Airline | 10 million | 1.7 million | 717,026 | 1.8 million | 416,000 | 14.6 million |

| 3 | Air France | 7.3 million | 1.0 million | 21,399 | 585,201 | 93,700 | 9.0 million |

| 4 | TUI UK | 5.9 million | 172,000 | 264,082 | 197,893 | 19,300 | 6.5 million |

| 5 | Ryanair | 5.0 million | 680,000 | 221,090 | 465,887 | 67,000 | 6.4 million |

| 6 | British Airways | 3.2 million | 994,000 | 431,954 | 1.3 million | 269,000 | 6.1 million |

| 7 | Lufthansa | 3.9 million | 1.4 million | 396,873 | 269,921 | 66,100 | 6.0 million |

| 8 | EasyJet | 1.7 million | 364,000 | 169,420 | 516,820 | 24,200 | 2.7 million |

| 9 | Iberia | 1.8 million | 394,000 | 202,306 | 32,355 | 32,300 | 2.4 million |

| 10 | Swiss Int. Airlines | 1.2 million | 775,000 | 122,127 | 271,711 | 55,400 | 2.4 million |

| 11 | TAP Portugal | 1.3 million | 520,000 | 200,507 | 69,715 | 28,500 | 2.1 million |

| 12 | Virgin Atlantic | 655,935 | 544,000 | 231,672 | 626,177 | 57,400 | 2.1 million |

| Airways | |||||||

| 13 | Alitalia | 1.4 million | 345,000 | 99,510 | 160,181 | 19,300 | 2.0 million |

| 14 | Vueling Airlines | 1.2 million | 182,000 | 122,833 | 299,003 | 7,830 | 1.8 million |

| 15 | Norwegian | 1.2 million | 370,000 | 123,747 | 118,200 | 22,400 | 1.7 million |

| 16 | SAS Scandinavian |

1.2 million | 259,000 | 108,260 | 119,371 | 13,900 | 1.7 million |

| 17 | Eurowings | 982,825 | 319,000 | 18,327 | 90,877 | 19,600 | 1.4 million |

| 18 | Finnair | 649,916 | 219,000 | 72,513 | 108,399 | 27,500 | 1.0 million |

| 19 | Aeroflot | 1.0 million | 656,000 | 13,933 | 38,918 | 27,700 | 978,533 |

| 20 | Jet 2 | 611,540 | 114,000 | 46,765 | 78,306 | 5,230 | 855,691 |

Total 63.4 million 12.3 million 4 million 9.4 million 1.4 million.

Note. Listed according to the number of followers.

In addition to the social media platforms, press releases from the official websites have also been analyzed. From December 1, 2019, to May 25, 2020, the airlines’ communication content was collected. This was done as the crisis was unfolding and governments worldwide were beginning to shut down air travel. During data collection, the researcher focused on content published in two languages—English and German (the native language of each of the researchers).

In order to identify codes, a coding scheme with keywords was designed. The coding scheme was established after coding the first messages, and the initially identified keywords became prominent. The SCCT model was applied for further coding (Coombs, 2007). The coding scheme with the corresponding keywords is presented in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Keywords selected for coding according to SCCT.

| SCCT Response Clusters | Strategies | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Instructing and adjusting information | flight update, attention to passenger on flight, cancellation, safety, HEPA, masks, disinfection | |

| Deny | Scapegoat | due to COVID-19, because of COVID-19, due to government restrictions |

| Diminish | Justification | thank you for your understanding, patience, high volume of requests, customer service, |

| Rebuild | Apology | Apology, we are sorry |

| Compensation | Voucher, refund, rebook, free change, flexible booking option | |

| Bolster | Ingratiation | thank you, clapping for our carers, in collaboration with, in coordination, together with, organized with, repatriation, medical supply, cargo flight |

| Reminder | always have been | |

| Victimage | Grounded, waiting for you, we look forward to seeing you again soon |

Before a framework was established at the beginning of the coding process, the messages containing information about customer service were initially grouped as the instructing and adjusting information category. However, subsequently, it became apparent that particular messages did not belong to this group and should be re-classified as justification messages.

4. Results and data analysis

A total of 7237 posts by the targeted airlines were collected from December 1, 2019, to May 25, 2020. Of these messages, 2344 (32%) were classified as being related to the COVID-19 crisis. The collected posts were coded and analyzed according to the SCCT model (Coombs, 2007).

4.1. Defining the starting point of the COVID-19 crisis

On January 25, 2020, two airlines—Aeroflot and Finnair—posted their first crisis-related messages:

Aerflot: “Information for passengers flying to/from China between 24 January and 7 February. Due to the virus pandemic in China, Aeroflot is offering passengers booked for flights to/from Chinese destinations to change their flight dates or return tickets” (Facebook, January 25, 2020).

Finnair: “Coronavirus update: We have updated our policy regarding the crew's possibility to wear masks when working on our flights, in line with the recommendation from Chinese authorities, who recommend that people in direct customer contact wear masks as a precaution” (Facebook, January 25, 2020).

In contrast to Aeroflot and Finnair, EasyJet was the last to post its first crisis-related message in mid-March 2020:

EasyJet: “We are currently experiencing extremely high volumes on social media, and we are sorry for any inconvenience this may cause … We would like to reassure you that the safety, health, and wellbeing of our passengers and crew always has been, and always will be, our number one priority. Thanks for your support during this time.” (Facebook, March 17, 2020)

Overall, the content analysis results revealed that most airlines (65%) released their first crisis communication messages in early March 2020, while 25% published their first messages in January 2020. Only 5% of the airlines released their first crisis-related message in February 2020. Accordingly, the pre-crisis timeframe was determined in the present study as the period from December 1, 2019, to February 29, 2020. The crisis timeframe was set as the period from March 1, 2020, to May 25, 2020.

4.2. Crisis communication strategies used by the airlines

The content analysis of the collected data revealed that in their crisis communication messages, the airlines employed five different strategies. The crisis response strategies were: (1) instructing and adjusting information, (2) deny, (3) diminish, (4) rebuild, and (5) bolster. These strategy clusters and their individual strategies and the frequency of related posts are summarized in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Crisis communication strategies identified in the data.

| Crisis Response Strategies | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Instructing and Adjusting Information | 859 | 36.7 |

| Primary Crisis Response Strategy 528 |

22.5 | |

| Deny | ||

| Scapegoat | ||

| Diminish | ||

| Justification | ||

| Rebuild | ||

| Apology | ||

| Compensation | ||

| Secondary Crisis Response Strategy 957 |

40.8 | |

| Bolster | ||

| Ingratiation | ||

| Reminder | ||

| Victimage | ||

| Total | 2344 | 100 |

4.2.1. Most employed crisis communication strategies

As shown in Table 3, the secondary crisis response strategy was the most frequently used in the data (n = 957, 40.8%). Among the secondary crisis response strategies, the ingratiation strategy (n = 819, 34.9%) has been employed the most. During the crisis, airlines frequently praised frontline workers and airline customers and employees. Another strategy used within this cluster was the victimage strategy (n = 133, 5.7%). The least adopted strategy from the Bolster cluster was the reminder strategy (n = 5, 0.2%). Some examples of relevant crisis response messages in the Bolster cluster are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Airline social media responses and SCCT strategies.

| Response category | Airline (s) | Social Media | Corresponding findings/examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructing and Adjusting (base response) | Air France TAP Portugal Turkish Airlines Finnair KLM Swiss |

Facebook (May 15, 2020) Facebook (March 11, 2020) Twitter (March 26, 2020) Twitter (March 9, 2020) Twitter (March 25, 2020) Twitter (Feb. 4, 2020) |

“To ensure you travel in complete safety, body temperature checks by infrared thermometer are being gradually deployed on departure of all of our flights. Passengers whose temperature exceeds 38C (100F) will not be able to board and will be able to postpone their trip free of charge.” “The health and safety of our customers and crew are TAP's priority. Through daily preventive disinfection, our specialized flight cleaning teams continue to ensure, with reinforcement due to the pandemic, that passengers who are soon to board one of our flights will have all the necessary conditions to make a safe flight.” “With HEPA filters, we renew the air in our aircraft every 3 min and keep the air quality always at a high level for you.” “We are cancelling our flights to/from Milan March 7- April and to/from Rome 12 March 7- April.” “CHECK YOUR FLIGHT STATUS- Due to travel restrictions and cancellations, our operation has changed. Always check your ‘flight status’ page, as flights ae subject to change and push messages may come with a delay.” “SWISS decided to extend flight suspensions to and from Beijing and Shanghai until 29 February. Flight operations to and from Hong Kong will continue as planned.” |

| Ingratiation | Air France Eurowings Swiss |

Facebook (April 7, 2020) Twitter (April 4, 2020) Twitter (May 7, 2020) |

“Every day, our teams receive many messages of support. We sincerely thank you for all these wonderfully heartwarming words. Air Franc and all its teams are fully mobilized to provide you optimum support and assistance and answer all your questions.” “It's time to say THANK YOU! All Eurowings colleagues on the ground and in the air understand only too well that the situation is not always easy for our passengers at the moment.” “SWISS and Edelweiss are thankful that both chambers of the Swiss Federal Assembly have approved by clear majorities the guarantee credit to help Swiss air transport cope with the consequences of the current coronavirus crisis.” |

| Victimage | British Airways KLM TAP Portugal |

Facebook (April 9, 2020) Facebook (April 29, 2020) Twitter (April 1, 2020) |

“We'll never stop dreaming of creating wonderful memories for our customers, but we know that now is not the time to travel. When our aircraft are cleared for take-off once again, we will be ready to fly and serve. From our family to yours, thank you. We love you Britain, and will see you very soon.” “For over a hundred years it's been our passion to fly you to the most beautiful places in the world. However, under the current circumstances, we're not able to fly you everywhere. That's why we've decided to bring a piece of our homeland to you.” “Today we say ‘See You Soon’ on behalf of the entire TAP family … We were born to fly and we are sure that soon we will have the pleasure of welcoming you on board again. Let us take care of each other. Together, we ill fly over borders and obstacles again.” |

| Reminder | EasyJet Iberia |

Facebook (March 17, 2020) Facebook (May 6, 2020) |

“We would like to reassure you that the safety, health, and wellbeing of our passengers and crew always has been, and always will be, our number one priority. Thanks for your support during this time.” “Security has always been part of our DNA. However, today we have to adapt our protocol and protect ourselves.” |

| Compensation | EasyJet Eurowings |

Facebook (April 30, 2020) Twitter (April 23, 2020) |

“Has your flight been cancelled? Get a little ‘easyJet extra’ towards your next trip when you choose a voucher.” “You have booked a flight for May or June and no longer wish to travel on that date? You can easily rebook or request a flight voucher.” |

| Apology | Alitalia Iberia |

Facebook (March 17, 2020) Instagram (April 20, 2020) |

“We apologise for the difficulties reaching our call centre.” “We are sorry to make you wait while we resolve your travel incidents.” |

| Justification | Air France British Airways |

Facebook (April 23, 2020) Twitter (March 13, 2020) |

“Our teams have been reinforced and remain mobilized on a daily basis to answer your queries as soon as possible. However, the number of requests remains extremely high.” “We understand that many of our customers have questions about this fast-moving situation. We've brought in extra teams to help, but please bear with us, it's taking longer than usual.” |

| Scapegoat | Finnair Iberia |

Twitter (March 20, 2020) Press room (Feb. 6, 2020) |

“We are adjusting our European traffic in April due to the impacts of the coronavirus. We are decreasing the seat capacity of our European traffic in April by over 20 per cent.” “Because of the coronavirus epidemic alert, the situation caused by the coronavirus outbreak in China has led Iberia to expand the interruption of its Madrid-Shanghai service until the end of April.” |

4.2.2. Second most employed crisis communication strategy

The second most preferred crisis communication strategy was the instructing and adjusting information strategy (See Table 4). Specifically, this strategy was used in 859 messages (36.7%) during the crisis period. Some examples of this strategy are provided on Table 4. Messages classified as instances of this strategy can be further categorized into (1) instructing information messages (n = 273, 11.7%), which inform stakeholders about safety measures and precautions taken to protect their customers and employees and (2) adjusting information messages (n = 586, 25%), such as posts about flight cancellations and changes.

4.2.3. Least employed crisis communication strategy

Furthermore, in the primary crisis response strategy (n = 528, 22.5%; see Table 3), which has been the least employed strategy, the most frequently used cluster was the rebuild cluster (n = 294, 12.5%). This cluster includes two strategies—compensation and apology—with the latter used only 21 times (0.9%) in the data. The compensation strategy included mostly messages about free cancellations, re-booking options, refunds and voucher compensations (n = 273; 11.6%). The justification strategy (n = 152, 6.5%), which belongs to the diminish cluster, was employed in combination with the airline's customer service. One of the least frequently used strategies was the scapegoat strategy from the deny cluster (n = 82; 3.5%). Table 4 provides several examples of primary crisis response messages.

4.3. Airlines’ crisis communication before and during the COVID-19 crisis

The unprecedented COVID-19 crisis took the aviation industry by surprise, and their communication frequency declined. According to the results, the airlines communicated 22% more often during the pre-crisis period, December 1, 2019, to February 29, 2020, then during the crisis phase from March 1, 2020, to May 25, 2020. Specifically, while the airlines released, on average, 2.42 messages per day during the pre-crisis period, the number of messages during the crisis phase dropped to 1.65 messages per day. Furthermore, the results also revealed considerable differences in how each airline managed their crisis communication during the COVID-19 crisis period (See Table 5 ). For example, while Eurowings and Finnair communicated the most frequently during the crisis, the Norwegian and the Vueling Airlines' crisis communication was very sparse (249, 239 vs. 34, 31). Furthermore, there were differences in the airline companies’ preferences for specific strategies. For instance, while Swiss International Airlines predominantly used the bolster strategy, Finnair extensively used the instructing and adjusting information strategy.

Table 5.

Frequency of Airlines’ Communication According to SCCT Recommendation.

| Airlines | Instructing/Adjusting | Deny | Diminish | Rebuild | Bolster | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurowingsa | 53 | 2 | 15 | 37 | 142 | 249 |

| Finnair | 92 | 18 | 23 | 31 | 75 | 239 |

| Swiss Int. Airlines | 36 | 3 | 8 | 26 | 124 | 197 |

| Lufthansa | 57 | 12 | 4 | 27 | 66 | 166 |

| Ryanaira | 101 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 28 | 153 |

| SAS Scandinavian | 48 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 71 | 140 |

| KLM | 43 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 67 | 139 |

| TAP Portugal | 62 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 37 | 136 |

| Jet2a | 103 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 15 | 134 |

| TUI UK | 37 | 3 | 21 | 7 | 53 | 121 |

| Virgin Atlantic | 23 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 72 | 108 |

| Aeroflot | 58 | 1 | 4 | 27 | 13 | 103 |

| Turkish Airlines | 47 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 33 | 99 |

| Iberia | 13 | 2 | 2 | 26 | 34 | 77 |

| Alitalia | 28 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 31 | 67 |

| British Airways | 5 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 34 | 57 |

| Air France | 20 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 16 | 49 |

| EasyJeta | 11 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 16 | 45 |

| Norwegiana | 7 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 34 |

| Vueling Airlinesa | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 31 |

Note.a = low-cost carriers.

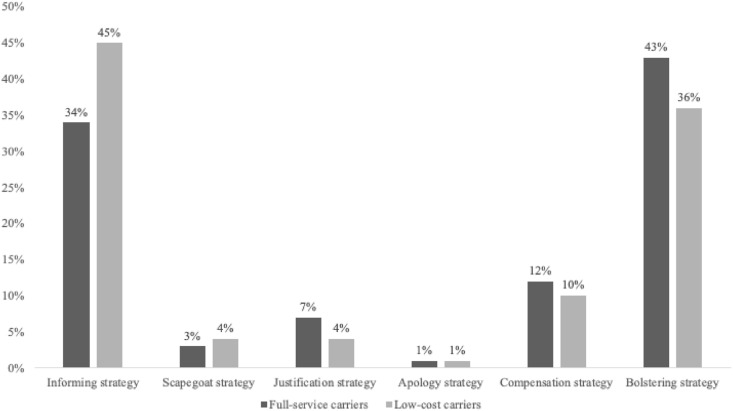

Interestingly, the airlines’ preferences in choosing strategies for crisis communication were influenced by whether a given airline was a full-cost or a low-cost carrier. The results showed that full-cost carriers more frequently used the bolster strategy (43%) than their low-cost counterparts (36%; see Fig. 1 ). Furthermore, as opposed to full-cost airlines, low-cost carriers more frequently published messages based on the instructing and adjusting information strategy (34% vs. 45%, respectively). Finally, full-service carriers frequently communicated about compensations and refunds (12%) compared to low-cost carriers (10%).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of full-service and low-cost carriers' crisis communication.

4.4. Channels used during pre-crisis and crisis communication

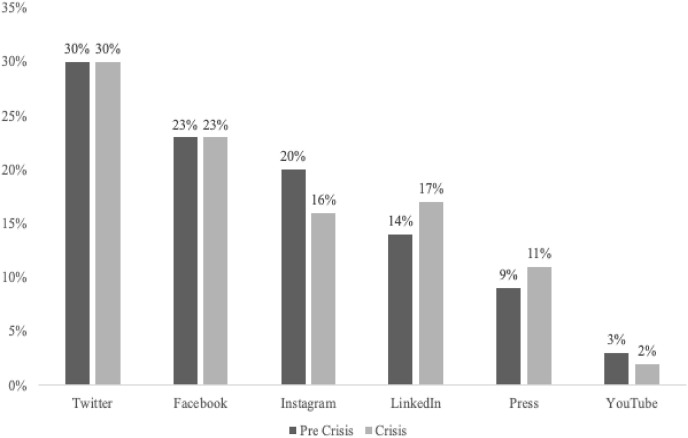

The results revealed several unique patterns concerning the choice and frequency of use of social media channels during the pre-crisis and crisis periods (see Fig. 2 ). To start with, Twitter was the most frequently used channel—airlines used it for 30% of their messages both before and during the crisis. Furthermore, the second most frequently used social media channel was Facebook, used for 23% of the airlines’ messages and updates. Interestingly, Instagram was more frequently used during the pre-crisis phase (20%) than in the crisis period (16%). The pattern was reversed with LinkedIn: It was more frequently used during the crisis period (17%) than before the crisis (14%).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of using different communication channels during the pre-crisis and crisis periods.

5. Discussion and implications

5.1. Defining the starting point of the COVID-19 crisis

The presented study results revealed considerable differences in how each of the studied airlines handled the start of the crisis. The World Health Organization (WHO; 2020) announced that COVID-19 was a global pandemic at the end of January 2020. However, most airlines released their first crisis-related message almost one and a half months afterward—early March 2020. This late response is surprising, mainly because when a company faces a crisis, a quick reaction in a matter of minutes is pivotal (Elliott, 2019). Employing the stealing thunder strategy, a proactive release of crisis information to the public gives an organization the power to be in charge of the information flow, thereby facilitating the crisis's mitigation (Lee, 2016).

Nevertheless, EasyJet's first crisis-related message was long overdue. Instead of releasing proactive information about flight cancellations and providing further passenger assistance, as Aeroflot and Finnair did in January 2020, EasyJet's first crisis message was a mix of several different crisis response strategies, such as apology (“we are sorry for any inconvenience this may cause”), justification (“we are currently experiencing extremely high volumes on social media”), reminder (“we would like to reassure you that the safety, health, and wellbeing of our passengers and crew always has been, and always will be, our number one priority”), and ingratiation (“Thanks for your support during this time!” (EasyJet, Facebook, March 17, 2020). Such mixing of several crisis response strategies can undermine the response's effectiveness (Coombs, 2007). Accordingly, to be effective, a company should have a consistent crisis response strategy in place.

5.2. Crisis communication strategies used by the airlines

Before defining a crisis response, an organization should carefully consider its crisis responsibility and the attribution made by its stakeholders. According to the SCCT framework, the COVID-19 crisis can be classified as a victim crisis (Coombs, 2007). The airlines were victims of the crisis: Since borders were closed, the demand for air travel sharply declined, and the companies had no other choice than to cancel flights and eventually ground their fleet (Deloitte, 2020). Coombs (2007) argued that stakeholders' attribution in a victim crisis is weak; therefore, the overall reputational threat is mild. Under such circumstances, the SCCT framework recommends using the instructing and adjusting information strategy and the bolster strategy (Coombs, 2007). Overall, the airlines followed this recommendation, and their COVID-19 crisis communication response did not accept responsibility for the crisis.

5.2.1. Most employed crisis communication strategy

The results of the content analysis revealed that airlines predominantly implemented communication strategies from the bolster cluster. They employed the reminder strategy from the SCCT framework, which aims to remind customers about a company's past good deeds. Additionally, airlines emphatically praised their stakeholders during the crisis. Applauding messages to frontline hospital workers and ‘thank you’ messages to customers, government institutions, and employees were frequently released. Except for Jet2 and Aeroflot, all other airlines made extensive use of this strategy, with Eurowings releasing the highest number of ingratiation messages. Praising stakeholders was previously reported to evoke sympathy for an organization, particularly during a victim crisis (Coombs, 2007). Through the ingratiation strategy, the airlines sought to minimize a potential threat to their reputation.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic can be classified as a victim crisis, airlines made little use of the victimage strategy than other strategies within the bolster cluster. With their victimage messages, the airlines sought to evoke sympathy for their situation and emphasize how much they suffered from the COVID-19 crisis. According to Coombs (2007), organizations use the victimage strategy to persuade their customers that they are also the victims of a situation and deserve mercy. However, due to the adverse and robust impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, all stakeholders—including customers, employees, governments —can be regarded as victims. From this perspective, airlines appearing as victims seeking the sympathy and attention of other victims may not be an effective crisis strategy. This could explain why the victimage strategy was rarely used.

5.2.2. Second most employed crisis communication strategy

As recommended by the SCCT framework, companies should prioritize communication about safety precautions and actions taken to reduce potential harm to the public, regardless of the crisis type (Coombs, 2007). As demonstrated by the results, the airlines followed the SCCT recommendation and released instructing information about safety precautions taken to reduce the risk for customers and employees who had contracted the virus while traveling with or working for the company. Apart from instructing information messages, airlines also frequently released adjusting information messages, such as flight updates, cancellations, and amendments. In general, such information messages are the basis of any crisis response and must be implemented anyhow. The entities responded to the crisis by releasing essential information, demonstrated their transparency to the stakeholders, and applied the stealing thunder strategy (Lee, 2016).

5.2.3. Least employed crisis communication strategy

Furthermore, the results demonstrated that, besides using the instructing and adjusting information strategy combined with the bolster strategies, which lines up with the SCCT recommendation, airlines also used the primary crisis response strategy. Except for Vueling Airlines, all other airlines adopted one or all crisis response strategies within the primary crisis response strategy, therefore going beyond the SCCT recommendation.

From the SCCT perspective, the rebuild strategies—apology and compensation—are beneficial and relevant during crises where there is a strong attribution of responsibility and a severe reputational threat, such as intentional or accidental crises (Coombs, 2007). However, in the event of a victim crisis, offering compensation is not obligatory. Nonetheless, the rebuild strategy is one of the main strategies for further accumulating reputational assets (Coombs, 2007). The airlines' motives behind their proactive offers of compensation may have been the airlines’ intention to avoid a further crisis, gain a reputational advantage, and influence consumer behavior after the crisis.

Furthermore, the content analysis results highlighted that the airlines' customer service centers most explicitly used the justification strategy. However, many airlines admitted that they were overwhelmed by customers' messages and calls. Research has reported that many social media crises result from customer service problems (Coombs, 2014b). As discussed in the literature, according to Coombs (2014b) and Cameron and Cheng (2018), such ‘para-crises,’ unless appropriately handled, can trigger a real crisis. To address the issue and diminish their responsibility for the crisis circumstances, many airlines opted to justify the long waiting times explicitly. Alongside the justification strategy, a few airlines also published apology messages for the inconvenience caused.

Overall, releasing crisis communication where the blame for an emergency is attributed to a third party facilitates reducing the attributed crisis responsibility (Coombs, 2007). Hence, it may be logical for an organization to seek a scapegoat for a victim crisis. However, this strategy was among the least frequently used. As Antonetti and Baghi (2019) argued, a possible explanation is that to have an effective and credible scapegoat strategy, a company needs to identify a third party that can be blamed for an emergency. However, during a pandemic, a third party can neither be identified nor held responsible for the situation. Accordingly, this strategy was rarely used for COVID-19 crisis communication.

Concerning RQ1, the results confirmed that the airlines followed the SCCT recommendations effectively to communicate their crisis-related messages. The results also showed that the airlines are aware of a possible continuation of the current emergency and, accordingly, included the crisis response strategies beyond the base response that best suited their needs.

5.3. Airlines’ crisis communication before and during the COVID-19 crisis

This paper's second goal was to explore the differences in crisis communication frequency before and during the COVID-19 crisis. For airlines such as British Airways, Iberia, or Norwegian, the crisis communication almost stopped in May 2020. The reason for this abrupt cessation of announcements was that 90% of the airlines' worldwide fleet was grounded, and many airline staff had been laid off (Ellis et al., 2020). As discussed in the introduction, although the airline industry is well-equipped to handle crises, unforeseeable and unprecedented situations such as COVID-19 can challenge even the most well-equipped and well-trained organizations.

Regarding the frequency, the results showed that, within the timeframe analyzed in the present study, the airlines published content 2344 times. The researcher also found differences in the frequency of crisis communication between different periods of the current emergency: Specifically, while the airlines published 2.42 messages per day in the pre-crisis phase, around 1.65 crisis-related messages were released per day in the crisis phase. Furthermore, the results also showed that airlines navigated the crisis in different ways. While some focused more on the bolster strategy, others predominantly used the instructing and adjusting information strategy. According to Coombs (2007), the more cooperative an airline's response strategy, the higher is its costs for the company. In this context, it is unsurprising that, as compared to full-service carriers, low-cost carriers more frequently gave a less coordinated response.

5.4. Channels used during pre-crisis and crisis communication

Concerning the airlines' communication channels for pre-crisis and crisis communication, the findings revealed that Twitter was the most frequently used channel during the pre-crisis and crisis periods. This is an interesting finding, as the targeted airlines' social media channels have more followers on Facebook, followed by Instagram, than Twitter. Furthermore, this finding contradicts the conclusion drawn in a previous study, where Facebook was reported to be the most commonly used social media channel in the airline industry (Bick, Bühler and Lauritzen, 2014). Also, the finding that Instagram was not a preferred channel of crisis communication for the airlines converges with Egan’s (2017) argument that as a picture- and video-sharing platform for expressing one's creativity, individuality, and achievements, Instagram is not a suitable channel for the communication of crisis-related content. Finally, the findings confirmed that LinkedIn was a more credible source for crisis-related content.

Only looking at the follower count is not sufficient for organizations to have an effective communication strategy. As argued by Coombs (2018) and Göritz et al. (2011), organizations should be aware of the target audiences of major social media channels and possess sufficient knowledge of how users interact on those channels. Overall, the present study shows that the airlines managed to adjust their social media channel strategies during the crisis to address appropriate stakeholders.

5.5. Implications

This study is particularly relevant in the current situation, as it provides an insight into how European airlines communicated to their stakeholders amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The results can also help airlines get prepared for a possible second (or third) wave deriving from variants of the COVID-19 pandemic. The aviation industry plays a central role in the tourism sector; thus, this research can interest those in the hospitality industry, particularly service-related organizations. The findings also highlight the importance of knowing the peculiarities of different social media channels and their users. Such knowledge enables an organization to elaborate and implement effective crisis communication strategies. Overall, the present study provides a comprehensive framework for the airline and tourism industry to understand crisis communication dynamics on social media better.

Towards the end of the present research period, some improvements in the COVID-19- related situation occurred, and European countries started to lift their quarantine measures and re-open their borders. However, despite these optimistic developments, the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was inevitable. For this reason, this study suggests several practical implications when communicating in the future about this or another pandemic. Firstly, entities should ensure that they have a well-established crisis communication team that can be empowered to make decisions. In the event of lay-offs, the crisis communication team has to remain in operation. An airline entity's CEO should ensure that the crisis communication team is not affected by lockdowns or lay-offs. Secondly, the existing crisis communication plans need to be updated with the findings and lessons learned from the pandemic. The crisis communication manager and the crisis team are responsible for this task. Thirdly, airline companies must assign a dedicated spokesperson, who can bolster the credibility of a company's crisis communication, cannot be overestimated. According to the data, none of the airlines named or listed their crisis communication managers' contact details or crisis teams on their homepages. Only a few of the airlines displayed the contact details of the public relations team. The spokesperson is also responsible for the completion of this task. Fourthly, the crisis communication manager should create a crisis checklist. The knowledge gained from the pandemic must be implemented in this checklist and ensure that an organization has to have several pre-written statements ready for release. This strategy will increase the pace of crisis communication. Finally, to reduce pressure on the customer service center, a task force must be established and trained. This task force should be on call and support the customer service center in times of crisis. The training manager and the crisis communication manager should establish the task force and provide adequate training.

Based on this study, the best practices to safeguard a company's reputation in the event of a second wave are as follows: 1) Communicate the basic facts about the crisis first, within an hour of the first signs of a crisis; 2). Emphasize instructing and adjusting information strategies; 3) Increase communication frequency during a crisis; and 4) Determine the appropriate crisis communication channels for addressing specific stakeholder groups.

6. Conclusion/limitations/future studies

To conclude, the airline industry suffered from the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Despite the first signs of recovery in the airline industry when the present research project was being completed, it remains unknown how the “new normal” will unfold. This study reveals that to protect an organization's reputation, crisis communication cannot be overestimated. Taken together, the findings of the conducted research expanded upon SCCT's response options and support the argument that every crisis is different and requires a unique approach to offset the reputational threat posed by the crisis. Notably, despite the extensive negative economic impacts of a crisis on an organization, companies can turn it into an opportunity and benefit from it in terms of setting effective communication practices for the future. However, it is still to be seen whether the airline industry will have a soft landing or a turbulent ride as the COVID-19 pandemic continues.

6.1. Limitations and future studies

The present study has several limitations. First, this study focused on the messages from the airlines to the customers. A future study could investigate customer perceptions of these messages or the customer messages themselves. Second, although the researcher analyzed a large dataset of the represented European airlines' messages, only content published in English and German received focus. Further, airlines such as TAP Portugal, Iberia, and Aeroflot released crisis-related messages in their country's languages. Thus, future research could include national languages beyond English and German. Third, the present study analyzed a limited sample of 20 European airlines, selected according to their revenue.

Further research could expand on this study by including more airline companies from Europe or other continents. Fourthly, the methodology could be a limitation as the most significant criticism of the methodology we employed is that it is not scientific (deductive) but based on inductive reasoning, drawn from the data analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 2017). Future studies could use the constant comparative method suggested by Glaser and Strauss (2017), which combines the coding and analytic procedures and allows a more systematic approach. Finally, the timeframe from December 1, 2019, to May 25, 2020, was established for gathering the data, which covered the pre-crisis and crisis phase but did not include the post-crisis phase. Future studies could analyze the messages in the post-crisis phase or the messages in all three phases.

References

- Agarwal P., Ferrell C. Flight bans and the Ebola crisis: policy recommendations for future global health epidemics. Harvard Publ. Health Rev. 2018;14 http://harvardpublichealthreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Chelsea-Ferrell-and- Pulkit-Agarwal14.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Albers S., Rundshagen V. European airlines' strategic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (January-May, 2020) J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;87:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonetti P., Baghi I. When blame-giving crisis communications are persuasive: a dual-influence model and its boundary conditions. J. Bus. Ethics. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04370-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arun T., Ozili P. 2020. Spillover of COVID-19: Impact on the Global Economy.https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3562570 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bick M., Bühler J., Lauritzen M. Twentieth Americas Conference on Information System; Savannah: 2014. Social Media Communication in European Airlines. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen J.T., Laroe C. Airline networks and the international diffusion of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Geogr. J. 2006;127(2):130–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4959.2006.00196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron G., Cheng Y. In: Social Media and Crisis Communication. Austin L., Jin Y., editors. Routledge; New York, NY: 2018. The status of social-mediated crisis communication (SMCC) research; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Canny I.U. An application of situational crisis communication theory on Germanwings flight 9525 crisis communication. SSRN Electronic J. 2016;7(3):1–18. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299593974_An_Application_of_Situational_Cr isis_Communication_Theory_on_Germanwings_Flight_9525_Crisis_Communication Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Cascio M.A., Freedman D.A., Lee E., Vaudrin N. A team-based approach to open coding: considerations for creating intercoder consensus. Field Methods. 2019;31(2):116–130. doi: 10.1177/1525822X19838237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys A.S. Better safe than sorry: why organizations in crisis should never hesitate to steal thunder. Bus. Horiz. 2017;60(3):305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2017.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: the development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007;10(3):163–176. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Institute for Public Relations; 2014. Crisis Management and Communications.https://instituteforpr.org/crisis- management-communications/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Institute for Public Relations; 2014. State of Crisis Communication: Evidence and the Bleeding Edge.https://instituteforpr.org/state-crisis-communication- evidence-bleeding-edge/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. In: Social Media and Crisis Communication. Austin L., Jin Y., editors. Routledge; New York, NY: 2018. Revising situational crisis communication theory; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cugueró-Escofet N., Suau-Sanchez P., Voltes-Dorta A. An early assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on air transport: just another crisis or the end of aviation as we know it? J. Transport Geogr. 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte . 2020. Global COVID-19 Government Response: Daily Summary of Government Response Globally.https://www2.deloitte.com/ch/en/pages/finance/articles/covid19-government-funding- response.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Egan K. 2017. The Difference between Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, & Pinterest.https://www.impactbnd.com/blog/the-difference-between-facebook-twitter-linkedin- google-youtube-pinterest (updated for 2020). Retrieved February 20, 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott K. In: The New Rules of Crisis Management. 3 ed. Culp R., editor. 2019. How to create an effective crisis preparedness plan in the digital age.https://www.rockdovesolutions.com/the-new-rules-of-crisis-management-3rd-edition Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis D., Guira J., Tyers R. What future do airlines have? Three experts discuss. 2020. https://theconversation.com/what-future-do-airlines-have-three-experts- discuss-135365 Retrieved from.

- Federal Office of Public Health FOPH . 2020. COVID-19, symptoms and treatment, origins of the new coronavirus. Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG.www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/krankheiten/ausbrueche-epidemien- pandemien/aktuelle-ausbrueche-epidemien/novel-cov/krankheit-symptome-behandlung- ursprung.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Font X., Gallego I. Changes in air passenger demand as a result of the COVID-19 crisis: using big data to inform tourism policy. J. Sustain. Tourism. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1773476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B.G., Strauss A.L. Routledge; New York, NY: 2017. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- Göritz A., Schultz F., Utz S. Is the medium the message? Perceptions of and reactions to crisis communication via Twitter, blogs and traditional media. Publ. Relat. Rev. 2011;37(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Hall C.M., Scott D. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tourism. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grančy M. Airline Facebook pages—a content analysis. European Transport Res. Rev. 2014;6:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s12544-013-0126-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greer C.F., Moreland K.D. United ’Airlines' and American ’Airlines' online crisis communication following the September 11 terrorist attacks. Publ. Relat. Rev. 2003;29:427–441. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2003.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IATA . 2016. Crisis Communication in the Digital Age: A Guide to “Best Practice” for the Aviation Industry.http://www.iata.org/publications/Documents/social- media-crisis-communications-guidelines.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- IATA . 2020. COVID-19.https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/third-impact- assessment Third impact assessment. Retrieved March 24, 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak S. Leading airline groups by revenue. Airl. Bus. 2019;35(6):28–29. https://edition.pagesuite- professional.co.uk/html5/reader/production/default.aspx?pubname=&edid=bd1095d8- 6883-4f75-90c4-c3391904a5a0 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Liu B.F. Are all crises opportunities? A comparison of how corporate and government organizations responded to the 2009 flu pandemic. J. Publ. Relat. Res. 2012;24(1):69–85. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2012.626136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.Y. Weathering the crisis: effects of stealing thunder in crisis communication. Publ. Relat. Rev. 2016;42(2):336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Othman A.F., Yusoff S.Z. Crisis communication management strategies in MH370 crisis with special references to situational crisis communication theory. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020;10(4):172–182. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i4/7118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobieralski J.B. Vol. 5. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives; 2020. COVID-19 and airline employment: insights from historical uncertainty shocks to the industry.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590198220300348 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statista . 2020. Most Popular Social Media Networks Worldwide as of April 2020, Ranked by Number of Active Users.https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of- users/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Timonen Verpi, Foley Geraldine, Conlon Catherine. Challenges When Using Grounded Theory: A Pragmatic Introduction to Doing GT Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2018;17:1–10. doi: 10.1177/1609406918758086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Rolling Updates on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel- coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happe Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Yu Meng, Li Zhiyong, Yu Zhicheng, He Jiaxin, Zhou Jhingyan. Communication related health crisis on social media: a case of COVID-19 outbreak. Current Issues in Tourism. 2020;2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1752632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]