Abstract

Adipose tissue secretions are depot-specific and vary based on anatomical location. Considerable attention has been focused on visceral (VAT) and subcutaneous (SAT) adipose tissue with regard to metabolic disease, yet our knowledge of the secretome from these depots is incomplete. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of VAT and SAT secretomes in the context of metabolic function. Conditioned media generated using SAT and VAT explants from individuals with obesity were analyzed using proteomics, mass spectrometry, and multiplex assays. Conditioned media were administered in vitro to rat hepatocytes and myotubes to assess the functional impact of adipose tissue signaling on insulin responsiveness. VAT secreted more cytokines (IL-12p70, IL-13, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8), adipokines (matrix metalloproteinase-1, PAI-1), and prostanoids (TBX2, PGE2) compared with SAT. Secretome proteomics revealed differences in immune/inflammatory response and extracellular matrix components. In vitro, VAT-conditioned media decreased hepatocyte and myotube insulin sensitivity, hepatocyte glucose handling, and increased basal activation of inflammatory signaling in myotubes compared with SAT. Depot-specific differences in adipose tissue secretome composition alter paracrine and endocrine signaling. The unique secretome of VAT has distinct and negative impact on hepatocyte and muscle insulin action.

Keywords: secretome, adipose tissue, insulin sensitivity, inflammation

Adipose tissue stored throughout the body has considerable structural and functional diversity, depending on anatomical location (1). Depots that have received the most attention with regard to type 2 diabetes and metabolic disease are subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) and visceral adipose tissue (VAT). The SAT depot is often thought of as a neutral fat storage compartment and has even been described as protective against type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease (2). In contrast, VAT accumulation is associated with a multitude of negative metabolic outcomes including cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and type 2 diabetes (3–5). Although the volume of VAT can be a relatively small portion of total body fat compared with SAT, studies that have carefully controlled for total body fat have found a strong correlation between increased visceral adiposity specifically and adverse metabolic risk (6). An important link in the negative association between VAT and metabolic health is direct delivery of free fatty acid (FFA) to the liver through the portal vein, which can also enter circulation, disrupting normal glucose regulation (7, 8). More recently adipose tissue has emerged as a significant secretor of a variety of bioactive compounds and proinflammatory mediators with local and systemic influence on processes essential to insulin sensitivity and metabolic homeostasis (9–11).

During the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes, adipose tissue cellular composition and abundance is marked by an increase in endothelial cells and fibroblasts, increased extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, and a proinflammatory shift in immune cell population (12). It is these cells, the nonadipocyte, stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue that are responsible for up to 90% of what is being secreted (11). Regarding the secretory contribution of SAT and VAT adipose depots, FFAs have retained much of the focus, and there is considerable work to be done to understand secreted bioactive factors that influence metabolic risk (9, 13, 14). In the present work, we describe a detailed secretion time course, along with comprehensive multi-omic profiling of the SAT and VAT secretomes. Additionally, we display the functional in vitro effect of SAT- and VAT-conditioned media on insulin sensitivity. This work highlights the complexity of the adipose tissue secretome and the importance that anatomical location has on secretome composition and functional impact.

Methods

Subjects

Paired human SAT and VAT tissue biopsies for this study were obtained from men and women aged between 33 and 48 years with obesity undergoing bariatric surgery (body mass index > 35 kg/m2). Participants gave written informed consent and were excluded if they had liver, kidney, thyroid, or lung disease. All individuals were sedentary and engaged in planned physical activity <2 h/wk. All medications were held for 3 days before tissue collection. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institution Review Board at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

Surgical Tissue Collection and Preparation of SAT and VAT

Tissue collection commenced on insertion of the laparoscopes. From 1 laparoscopic incision, superficial SAT was excised followed by omental adipose tissue (VAT). Both tissues were collected in 37 °C DMEM, transported to the laboratory, and dissected to remove blood and cauterized tissue. The average total adipose tissue explant volume was 209.5 mg for SAT and 273.8 mg for VAT. To account for differences in tissue sample sizes, explants were first cut into 10- to 20-mg pieces, and then rinsed thoroughly with 37 °C DMEM over a sterile 100-µm mesh filter. Tissues were then weighed, and DMEM volume was normalized using a 20:1 ratio (µL:mg) and cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Conditioned Media Optimization and Generation

Media were collected from the cultured SAT and VAT after 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 48 hours of tissue incubation. At those time points, either the entire conditioned media volume was collected and replaced with the same volume of fresh DMEM, or 5% of the total conditioned media volume was collected and replaced with fresh DMEM, leaving the majority of the secretome in culture throughout the time course. Based on results from this optimization experiment, adipose tissue was prepped for subsequent secretome analysis at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 1 hour in a 20:1 ratio (µL:mg). After 1 hour, conditioned media were discarded and replaced with a fresh volume of DMEM, incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2, and collected after 24 hours.

Measurement of Cytotoxicity and Hypoxia

To determine the effects of adipose tissue culture and conditioned media generation over time, SAT and VAT tissue explants were prepared and cultured as described previously. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) secreted into the cell culture supernatant was used to measure cytotoxicity using an LDH-Cytotoxicity Colorimetric Assay Kit (BioVision, Waltham, MA). To evaluate the need for supplemental oxygen, before each incubation, tissues were oxygenated using 95:5 O2:CO2 for 30 seconds with a gentle stream, sealed, and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. HIF-1α was measured as a hypoxia outcome in the adipose tissue conditioned media over time (Ray Biotech, Peachtree Corners, GA).

Cytokine Analysis

Quantification of 10 proinflammatory cytokines in adipose tissue conditioned media was performed using V-Plex Proinflammatory Panel 1 Human Kits (#K15049D, Meso Scale Diagnostics LCC, Rockville, MD). Samples were analyzed in duplicate and assays were performed per manufacturer protocol and read on a QuickPlex SQ120 (Meso Scale Diagnostics).

Adipokine Analysis

Adiponectin, HGF, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), resistin, and PAI-1 in adipose tissue-conditioned media were quantified using MILLIPLEX MAP Human Adipokine Magnetic Bead Panel kit (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) following the manufacturer protocol. Samples were analyzed in duplicate on a Luminex MAGPIX with xPONENT software (Luminex, Austin, TX).

Olink Analysis

Adipose tissue-conditioned media was evaluated by the Olink Explore platform that quantified 1072 proteins (Olink Bioscience AB, Uppsala, Sweden) using multiplex proximity extension assay panels, as previously described (15). Functional analysis of differentially expressed proteins was performed using DAVID open-access software (Functional Annotation Tool) using the entire output of human predicted genes as the background.

Eicosanoid Analysis

PGE2 and TBX2 were analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry as previously described (16). Briefly, after addition of a deuterated internal standard mixture, samples were added to methanol (1:2), centrifuged, and then extracted using a solid phase extraction cartridge (Strata-X 33 µm Polymeric Reversed Phase, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Metabolites were eluted, dried down, reconstituted, injected, and separated on an HPLC column (Gemini C18, 150 × 2 mm, 5 µm, Phenomenex) directly interfaced into the electrospray source of a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (4000 QTRAP, Sciex, Framingham, MA).

Cell Culture

L6 myotubes grown in low-glucose DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/100 mg Penicillin/Streptomycin using standard techniques with experiments were performed after 7 days of differentiation (17). Rat primary hepatocytes were prepared from 10-week-old rats using a previously published protocol (18). Isolated cells were filtered through a 100-µm cell strainer, collected by centrifugation (5 minutes at 50g), and washed 3 times with 20 mL of Wash Media (Invitrogen 17704-024). Cells were washed and Incubation Media was replaced after 4 hours. Experiments were performed the following day.

Measurement of Glycogen Synthesis and Insulin Signaling In Vitro

VAT and SAT conditioned media was diluted in DMEM and administered to L6 myotubes/primary rat hepatocytes for 21 hours, followed by a 3-hour serum starve with conditioned media exposure for a total treatment time of 24 hours. Cells were stimulated with 100 nM insulin for 1 hour in the presence of D-14C-glucose, after which the cell samples were harvested and glycogen synthesis of incorporated D-14C glucose was measured, as previously described (19). For measurement of insulin signaling, cells were stimulated with 100 nM insulin for 15 minutes and harvested in ice cold RIPA buffer.

Immunoblot Analysis

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Membranes were incubated for 1 hour in Intercept Blocking Solution (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) followed by primary (overnight at 4 °C) and secondary incubation (1 hour at room temperature without light exposure) in Intercept Antibody Diluent (LI-COR). The signal was detected using an Odyssey Clx Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR) and analyzed using Image Studio software.

All antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA; RRIDs: AB_2315049, AB_1147620, AB_561124, AB_10013750, AB_10839406, AB_2800035, AB_2800285, AB_331646, AB_390780) except for anti-phospho IRS1 tyrosine 612 (MilliporeSigma; RRID: AB_1163457).

Measurement of Glucose Production In Vitro

Isolated hepatocytes were starved for 4 hours in SAT/VAT-conditioned media diluted in Starvation Media (Williams E Media, 0.1% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1% BSA), after which cells were treated with 100 nM of insulin alone, 100 µM dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate (dbcAMP) alone or with a combination of 100 nM insulin and 100 μM dbcAMP in SAT/VAT-conditioned media diluted in glucose-free DMEM with 1% BSA. Glucose production was measured using a commercially available hexokinase-based glucose production assay kit (MilliporeSigma).

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups and tissues were analyzed using a 1-way ANOVA (Prism, GraphPad, San Diego, CA). When significant differences were detected, individual means were compared using Student t tests to determine differences between groups. Internal plate standardization and quality control for the proteomics were performed by Olink, exporting normalized protein expression values on log2 scale. A discovery approach was used for proteomic analysis using unadjusted P values for evaluating differentially expressed proteins.

Results

Demographics

The demographics of individuals undergoing bariatric surgery are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study participant demographics

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| N (female/male) | 12 (8/4) |

| Age (y) | 41.8 ± 2.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/mg2) | 45.0 ± 2.3 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 95.0 ± 7.8 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 5.8 ± 0.18 |

Values are mean ± SEM.

Adipose Tissue-conditioned Media Generation

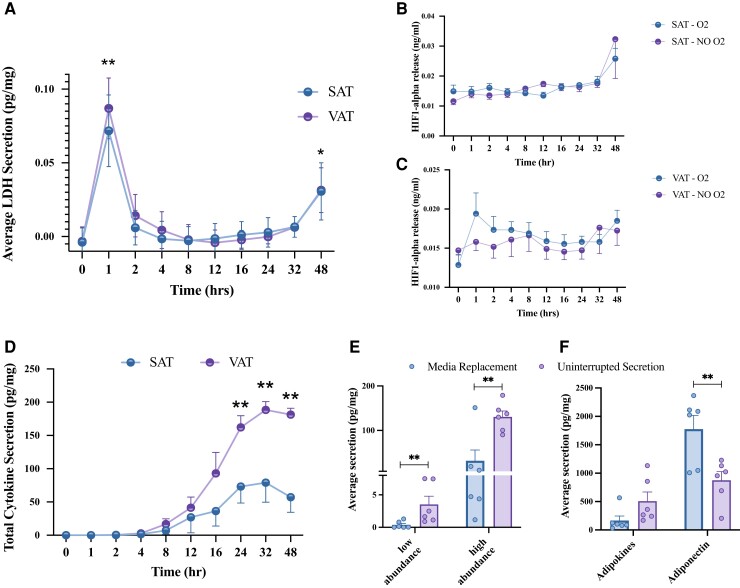

Explants from individuals with obesity were used to generate SAT- and VAT-conditioned media over the course of 48 hours to determine preferential methods for adipose tissue secretome analyses. After the first hour in culture, there was a significant increase in LDH concentration, a measure of cytotoxicity, in both SAT- and VAT-conditioned media samples (P < 0.01, Fig. 1A), which significantly decreased after the next hour in culture (P < 0.01, Fig. 1A), and remaining consistently low up to 24 hours, but increased significantly at 48 hours (Fig. 1A). These data indicated that although there was substantial cytotoxicity present immediately following tissue preparation and during the first hour of conditioned media generation, the very low levels of cytotoxicity present during the subsequent 24 hours would not confound the adipose tissue secretome analysis. When comparing oxygenated vs nonoxygenated culture conditions, there was no difference in HIF-1α concentration across the 48-hour time course in SAT or VAT samples (Fig. 1B and 1C), indicating that the tissues did not become hypoxic in culture. After 24 hours, significant differences in total cytokine (P < 0.05, Fig. 1D) and adipokine (P < 0.05, Supplemental Data 1A (20)) secretion between SAT and VAT were detected. These results indicate that 24 hours is an appropriate amount of time to capture the adipose tissue secretome without hypoxia or cytotoxicity.

Figure 1.

SAT/VAT secretome time course. Conditioned media generated from SAT/VAT explants were sampled/analyzed across 48 hours. (A) Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentration and HIF-1α accumulation in (B) SAT and (C) VAT was measured at each timepoint. *Significantly different from timepoint 0. (D) Total cytokine secretion in conditioned media was measured at each time point. *VAT significantly different from SAT. The effect of feedback from adipose tissue secretion on (E) total cytokine and (F) adipokine accumulation was measured after 24 hours. Media replacement is quantified by taking the sum of each value at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 24 hours, whereas uninterrupted secretion signifies the singular value after 24 hours. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n = 6.

Cell–cell Feedback Effects on Total Secretome Composition

Continuous, uninterrupted incubation and opportunity for cell–cell interactions with secreted factors resulted in significantly increased concentration of low (interferon-γ [IFN-γ], IL-10, IL12p70, IL-13, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4; P < 0.01) and high abundance cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8; P < 0.01), when compared with samples in which media were replaced and feedback was interrupted (Fig. 1E and 1F). Similar trends were observed for adipokines (MCP-1, PAI, resistin, HGF), with the exception of adiponectin, which was lower with continuous compared with interrupted incubation (P < 0.05). Combined, these data suggest that cell–cell communication via secreted factors augments the adipose tissue secretome except for adiponectin whose secretome did not follow this pattern.

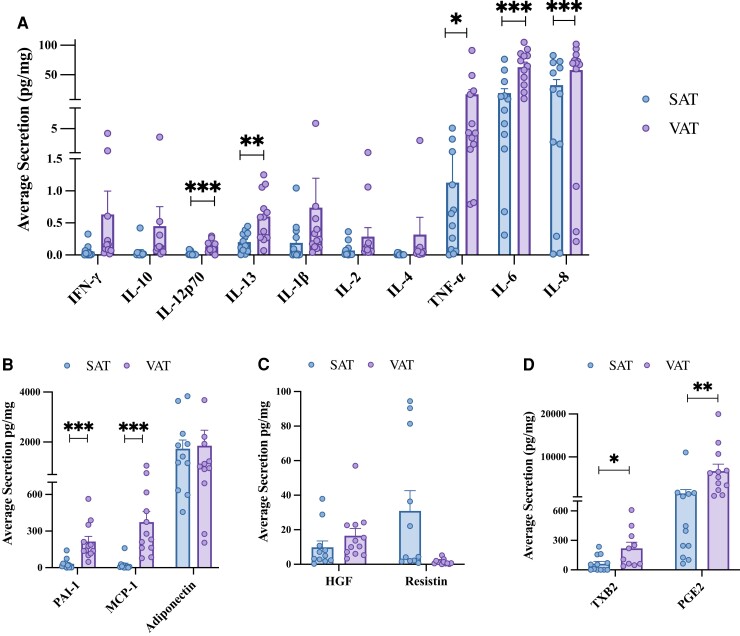

SAT and VAT Secretome Composition

Following optimization of adipose-conditioned media methods, VAT secretion of IL-12p70 (P < 0.001), IL-13 (P < 0.01), TNF-α (P < 0.05), IL-6 (P < 0.01), and IL-8 (P < 0.05) was significantly higher than SAT (Fig. 2A). In this small dataset, there were also trends for increased secretion of IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-1B, IL-2, and IL-4 from VAT (Fig. 2A). VAT secretion of MCP-1 and PAI-1 was significantly higher than SAT (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). SAT secreted more resistin than VAT (P = 0.07), and no differences in the secretion of HGF or adiponectin were observed (Fig. 2B and 2C). VAT secretion of proinflammatory eicosanoids TBX2 and PGE2 was significantly higher than SAT (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2D and 2E). These findings highlight the elevated inflammatory output of VAT compared with SAT.

Figure 2.

SAT and VAT secretome composition. Following SAT and VAT explant processing and 24-hour culture, adipose tissue conditioned media were analyzed for (A) cytokine, (B, C) adipokine, and (D) prostanoid concentrations. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 12.

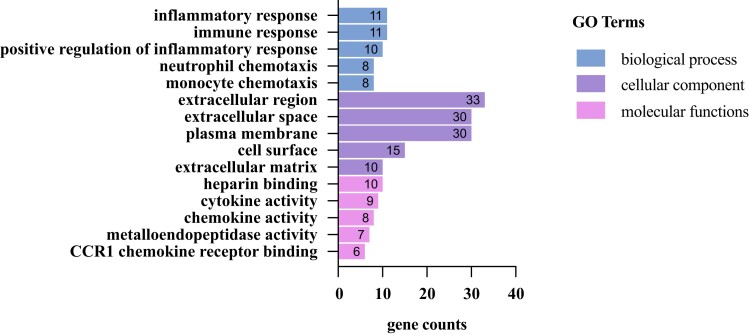

Conditioned Media Proteomics

To gain a more in-depth understanding of the secretome protein composition, functional annotation of differentially expressed proteins between SAT and VAT was performed (Fig. 3, Table 2). The gene ontology analysis results indicated that, for biological process ontology, targets were enriched in inflammatory and immune response processes; for cellular component ontology, targets were enriched in the extracellular region/space/matrix; and for molecular functions, targets were involved in cytokine/chemokine activity and metalloendopeptidases activity (Fig. 3). These results highlight immune infiltration/activation, inflammatory response, and extracellular matrix processes as important functional differences between the SAT and VAT secretome.

Figure 3.

SAT and VAT functional proteomic analysis. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of proteins identified as differentially expressed (P < 0.05) between SAT and VAT secretome analysis.

Table 2.

Differentially expressed proteins between SAT and VAT secretomes

| Protein identification | Protein name | SAT mean (NPX values) | VAT mean (NPX values) | Unadjusted P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P08727 | KRT19 - Cytokeratin-19 | 55.956271 | 186.020343 | 0.0001 |

| Q13219 | PAPPA - Pappalysin-1 | 46.9531223 | 129.293254 | 0.0007 |

| Q9BXY4 | RSPO3 - R-spondin-3 | 88.429085 | 167.305711 | 0.0007 |

| Q8WXI7 | MUC-16 - Mucin-16 | 62.7010027 | 135.603511 | 0.0010 |

| Q6UX15 | LAYN - Layilin | 46.9857025 | 90.5159558 | 0.0022 |

| Q92823 | Nr-CAM - Neuronal cell adhesion molecule | 129.656181 | 19.3096528 | 0.0034 |

| Q99538 | LGMN - Legumain | 31.4642634 | 93.8544966 | 0.0045 |

| Q9Y275 | TNFSF13B - Tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 13B | 59.2629226 | 86.3835896 | 0.0085 |

| P15311 | EZR - Ezrin | 31.2581339 | 69.015235 | 0.0101 |

| P21246 | PTN - Pleiotrophin | 6.72456009 | 50.9280178 | 0.0117 |

| Q2MKA7 | RSPO1- R-spondin-1 | 37.9110842 | 86.7350761 | 0.0119 |

| P21810 | BGN - Biglycan | 45.0579103 | 21.8314458 | 0.0121 |

| P78556 | CCL20 - C-C motif chemokine 20 | 70.4389791 | 129.138766 | 0.0126 |

| Q01638 | ST2 - Interleukin-1 receptor-like 1 | 100.181105 | 141.819465 | 0.0127 |

| P02760 | AMBP - Alpha-1-Microglobulin/Bikunin Precursor | 87.5822947 | 51.0996873 | 0.0128 |

| Q15109 | RAGE - Advanced glycosylation end product-specific receptor | 135.427245 | 69.3536764 | 0.0131 |

| P80098 | CCL7 - C-C motif chemokine 7 | 40.5951645 | 113.209751 | 0.0152 |

| Q14773 | ICAM4 - Intercellular adhesion molecule 4 | 77.0501462 | 38.5368229 | 0.0155 |

| O60462 | NRP2 - Neuropilin-2 | 31.38007 | 21.0037427 | 0.0155 |

| P08253 | MMP-2 - Matrix metalloproteinase-2 | 14.009602 | 7.49158702 | 0.0156 |

| P43490 | NAMPT - Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase | 73.9540966 | 51.4757053 | 0.0174 |

| Q9UKS7 | IKZF2 - Ikaros family zinc finger protein 2 | 16.6569048 | 25.376882 | 0.0180 |

| Q16790 | CAIX - Carbonic anhydrase 9 | 3.89458243 | 68.8877375 | 0.0196 |

| P01215 | CGA - Glycoprotein hormones alpha chain | 6.2116602 | 35.5842897 | 0.0225 |

| P01130 | CV3 LDL receptor - Low-density lipoprotein receptor | 10.8446378 | 3.86358987 | 0.0238 |

| Q9H5V8 | CDCP1 - CUB domain-containing protein 1 | 9.30494475 | 26.6284251 | 0.0243 |

| Q9H6B4 | CLMP - Adipocyte adhesion molecule | 95.6001652 | 43.605555 | 0.0251 |

| P78325 | Oncology ADAM 8 - Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 8 | 40.5732881 | 24.8793134 | 0.0253 |

| P07585 | DCN - Decorin | 247.867642 | 198.359505 | 0.0255 |

| P78310 | Immune Response CXADR - Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor | 0.3664827 | 23.3355314 | 0.0260 |

| O14788 | TRANCE - Tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 11 | 9.05941418 | 15.3388863 | 0.0261 |

| O75356 | ENTPD5 - Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 5 | 36.1940322 | 55.0388435 | 0.0261 |

| P24158 | CV3 PRTN3 - Myeloblastin | 52.2263466 | 1.17108808 | 0.0262 |

| P02144 | MB - Myoglobin | 70.5503735 | 120.55821 | 0.0275 |

| P13500 | MCP-1 - Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 | 195.726145 | 261.786395 | 0.0299 |

| P13236 | CCL4 - C-C motif chemokine 4 | 61.9855682 | 159.787211 | 0.0308 |

| Q15126 | PMVK - Phosphomevalonate kinase | 38.5766484 | 33.4075485 | 0.0324 |

| Q96D42 | KIM1 - Hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1 | 28.8057555 | 45.0072319 | 0.0324 |

| P36269 | NE GGT5 - Glutathione hydrolase 5 proenzyme | 23.1020799 | 7.66675689 | 0.0328 |

| P10147 | CCL3 - C-C motif chemokine 3 | 162.029034 | 271.109082 | 0.0335 |

| Q8N2G4 | LYPD1 - Ly6/PLAUR domain-containing protein 1 | 40.271706 | 44.4082564 | 0.0339 |

| O15467 | CV3 CCL16 - C-C motif chemokine 16 | 16.54343 | 9.30600477 | 0.0339 |

| Q92520 | FAM3C - Family with sequence similarity 3 | 59.0443605 | 100.382626 | 0.0344 |

| Q15661 | TPSAB1 - Tryptase alpha/beta-1 | 151.08881 | 101.75659 | 0.0353 |

| P11464 | NE PSG1 - Pregnancy-specific beta-1-glycoprotein 1 | 0.78997447 | 25.4631552 | 0.0363 |

| Q13231 | CHIT1 - Chitotriosidase-1 | 41.0545054 | 20.1041425 | 0.0381 |

| O94907 | Dkk-1 - Dickkopf-related protein 1 | 126.262271 | 183.594751 | 0.0392 |

| O75475 | PSIP1 - PC4 and SFRS1-interacting protein | 88.197148 | 117.995168 | 0.0396 |

| P29965 | CD40-L - Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Superfamily Member 5 Ligand | 35.7902123 | 25.461039 | 0.0403 |

| Q14512 | FGF-BP1 - Fibroblast growth factor-binding protein 1 | 45.6851729 | 73.7600404 | 0.0410 |

| Q13421 | MSLN - Mesothelin | 59.4791187 | 68.8839908 | 0.0410 |

| P09237 | MMP7 - Matrix metalloproteinase-7 | 86.9644464 | 39.3968265 | 0.0417 |

| Q9P126 | CLEC1B - C-type lectin domain family 1 member B | 111.174342 | 38.2370854 | 0.0427 |

| P10147 | CCL3 - C-C motif chemokine 3 | 185.100543 | 286.843498 | 0.0429 |

| P15018 | LIF - Leukemia inhibitory factor | 191.082806 | 259.985684 | 0.0453 |

| P01137 | LAP TGF-beta-1 - Transforming growth factor beta-1 proprotein | 66.2979714 | 26.2455776 | 0.0455 |

| P19971 | TYMP - Thymidine phosphorylase | 140.462075 | 87.0047554 | 0.0459 |

| O75054 | IGSF3 - Immunoglobulin superfamily member 3 | 30.3261053 | 44.644788 | 0.0486 |

| P05121 | PAI - Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 | 94.2633405 | 135.384111 | 0.0499 |

| P21860 | ERBB3 - Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-3 | 46.2121753 | 54.1128738 | 0.0500 |

Abbreviation: NPX, normalized protein expression.

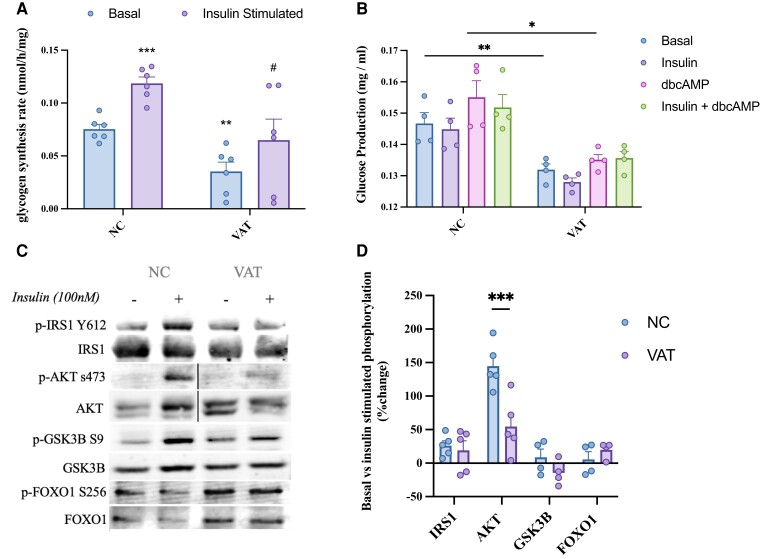

SAT/VAT-conditioned Media Modulate Insulin Sensitivity In Vitro

To investigate the functional impact of the VAT secretome on liver metabolic function, we administered VAT-conditioned media to primary hepatocytes in vitro. Insulin stimulation caused a significant increase in glycogen synthesis (P < 0.001), which was abolished in hepatocytes exposed to VAT for 24 hours (Fig. 4A), indicating a reduction in insulin sensitivity. Basal glucose production from hepatocytes exposed to VAT conditioned media for 24 hours was significantly decreased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4B). Additionally, glucose production from untreated hepatocytes increased after stimulation by a cell-permeable synthetic analog of cAMP; however, VAT treatment caused a significant reduction in cAMP-stimulated glucose production compared with normal cells (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Although insulin was able to reduce glucose production when treated in combination with cAMP in hepatocytes without VAT exposure, this blunting of glucose production by insulin was not observed in hepatocytes after VAT treatment (Fig. 4B). Although this in vitro model does not reflect the complicated dynamics of hepatic glucose regulation in vivo, these results indicate that VAT secretome may impact normal hepatic regulation of glucose production. Finally, VAT caused significant reduction in insulin-stimulated AKT phosphorylation (P < 0.001); however, no other downstream mediators of glycogen synthesis and glucose production were significantly affected (Fig. 4C and 4D), indicating that the effect of VAT on hepatocyte glucose regulation may not be entirely explained by disruptions in insulin signaling.

Figure 4.

VAT secretome modulates hepatocyte function in vitro. (A) Primary rat hepatocytes were exposed to VAT-conditioned media for 24 hours to measure the direct impact on basal and insulin stimulated (100 nM) glycogen synthesis. #Significantly different from negative control (insulin stimulated), *significantly different from negative control (basal). (B) Alteration in glucose production in response to 100 µM dbcAMP with or without insulin was measured in primary rat hepatocytes after 24 hours’ exposure to VAT-conditioned media. (C) Following 24 hours of VAT treatment, downstream effectors of insulin signaling were measured (phosphorylated and total protein) and (D) quantification of immunoblot analyses measuring differences between protein expression in the basal compared with insulin-stimulated conditions are shown. Black lines in panel C represent where lanes were removed from the immunoblot image. Values are mean ± SEM. *Significantly different from negative control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 6.

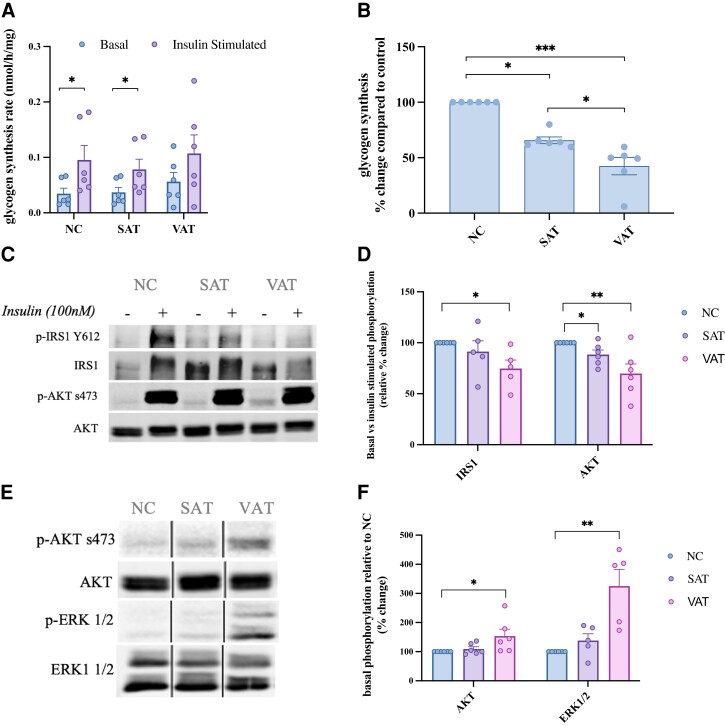

Skeletal muscle is critical to whole-body glucose homeostasis and secretions from SAT and, to a lesser degree, VAT reach skeletal muscle through endocrine interactions; therefore, SAT- and VAT-conditioned media was administered to L6 myotubes in vitro. A significant decrease in skeletal muscle insulin-stimulated glycogen synthesis was observed after 24 hours of exposure to SAT (P < 0.05) and VAT (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A and 5B). VAT exposure caused a significant reduction in phosphorylation of IRS1 (Tyr612) (P < 0.05) and AKT (Ser473) (P < 0.01) in response to insulin (Fig. 5D). A significant reduction in AKT phosphorylation was also observed in response to SAT exposure (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5D). VAT treatment caused an increase in phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) (P < 0.05) and ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (P < 0.01) in the absence of insulin (Fig. 5E). This indicates that VAT, more robustly than SAT, causes constitutive activation of signaling cascades involved in processes such as inflammation and glucose utilization, while decreasing myotube responsiveness to insulin.

Figure 5.

SAT and VAT secretomes modulate myotube function in vitro. (A) Absolute and (B) relative percent change between basal and insulin stimulated (100 nM) glycogen synthesis in L6 myotubes was measured after to 24 hours’ exposure to SAT/VAT-conditioned media. Changes to myotube signaling after 24 hours of SAT/VAT exposure was measured by immunoblot analysis in response to (C) insulin stimulation and (E) in the basal state, which is quantified as a (D) relative percent change between basal and insulin-stimulated protein expression (phosphorylation vs total protein) and (F) percent change in phosphorylated vs total protein in the basal state only. Black lines represent where lanes were removed from the immunoblot image. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 6.

Discussion

As our understanding of the endocrine/paracrine role of adipose tissue continues to expand, the need for in-depth studies exploring the composition of the adipose tissue secretome and its impact on local and systemic regulation of metabolic homeostasis has increased. In the present study, we aimed to comprehensively measure visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue secretomes from populations with obesity, including outcomes of secretome exposure on metabolic function in vitro. The major findings from this study are as follows: (1) autocrine/paracrine interactions within whole adipose tissue amplifies secretory function; (2) VAT has increased secretory output compared with SAT, secreting greater levels of cytokines, chemokines, adipokines, and prostanoids; (3) ECM organization as well as immune/inflammatory processes distinguish VAT from SAT; and (4) the VAT secretome in particular activates inflammatory signaling and disrupts insulin sensitivity, signaling, and glucose regulation in metabolic tissues.

Tissue preparation for culture can trigger substantial cellular stress and a large amount of cell damage/death. Cellular cytotoxicity and death processes result in the release of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-8, CCL2, IL-1, and IL-18 (21, 22); these factors will be detectable in the media for hours or days depending on the protein (23, 24). Because tissue handling can elevate inflammatory signals, it is important to discard those stress-specific factors and resume the generation of conditioned media when cellular secretion resembles “normal” tissue function. Similarly, we have shown that cytotoxicity begins to emerge in adipose tissue explants after 24 hours in culture, suggesting that extensive incubation times are not advisable because they may introduce factors that are the result of cell damage/death, with the potential to confound future analyses.

Adipose tissue cellular composition is altered in the obese state, and it has been suggested that rather than contributions from individual adipocytes, it is crosstalk between different cell types, as well as local paracrine interactions, which leads to substantial increases in cytokine secretion from adipose tissue (25). We found that adipose tissue from individuals with obesity secreted significantly more cytokines, adipokines, and eicosanoids in a 24-hour period when the tissue was left to incubate in its secretory milieu, compared with those tissues that had frequent media replacements, emphasizing the significance of paracrine signaling between cells in the activation of the immune system. The findings in this study and others display the importance of preserving paracrine signaling between different cell types within the whole tissue to capture an accurate picture of the adipose secretome that reflects the in vivo condition.

Adipose tissue becomes inflamed when increased secretion of chemotactic factors leads to the infiltration of immune cells, causing increased secretion of cytokines such as IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α (26). Obese VAT is known to harbor significantly more immune cells than SAT, leading to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines, which was corroborated in this study (27). Although our findings of increased secretion of chemoattractant and pro-inflammatory mediators are consistent with what is known about the inflammatory nature of VAT, increased secretion of anti-inflammatory agents observed in this study was somewhat less expected. However, others have found an increase in circulating IL-13 and IL-4 in obesity with strong correlations to visceral obesity (28, 29). To explain this increased expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, 1 hypothesis that has emerged describes a state of “cytokine resistance” in type 2 diabetes from disrupted anti-inflammatory cytokine action and impaired signaling cascades that bridge insulin and cytokine action (30, 31). Just as signaling through the insulin receptor is disrupted in type 2 diabetes, cytokine receptors that require IRS phosphorylation for intracellular signals are potentially susceptible to disruption. This cytokine resistance is in agreement with the increased secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines from obese VAT observed in this study, pointing to the continual ineffectiveness of anti-inflammatory cytokines to maintain balance, and the subsequent low-grade inflammation that accompanies increased visceral adiposity and type 2 diabetes.

In addition to cytokines, secretion of the eicosanoids PGE2 and TXB2 were increased from VAT compared with SAT. PGE2 and TXB2 are part of a family of eicosanoids called prostanoids that are derived from cyclooxygenase and have been associated with inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity (32–34.) These compounds exert complex and diverse effects on glucose and fatty acid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation (35). In the liver, these metabolites generally act as negative mediators of insulin sensitivity, disrupting regulation of glucose utilization and lipid storage (36, 37). The effect of prostanoids such as PGE2 in peripheral tissues remains controversial. In obese adipose tissue, some have reported a negative effect of PGE2 on inflammation, lipid metabolism, and insulin resistance (38, 39), whereas others report a protective role through the regulation of immune balance and lipid distribution/accumulation (40, 41). Interestingly, in skeletal muscle, prostaglandins have been shown to limit inflammation and increase insulin sensitivity (42, 43). VAT-derived PGE2 and TXB2 are elevated and, in addition, have direct access to the liver, where they appear to elicit a more negative effect on insulin sensitivity than in peripheral tissues. This highlights the anatomical relevance of depot-specific adipose secretions and adds to the wealth of evidence suggesting a specifically negative role for VAT in hepatic glucose and fatty acid metabolism.

In addition to the inflammatory secretome, proteomic enrichment analysis highlighted differences in secretion of ECM. Specifically, SAT and VAT had significantly differential secretion of ECM-associated proteins involved in processes such as the proteolytic release of membrane proteins (shedding), fibrillogenesis, and ECM disassembly. Differences in ECM remodeling between SAT and VAT has been similarly highlighted by others (14), and there is accumulating evidence suggesting an association between ECM remodeling and insulin resistance in metabolic tissues such as adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle (44, 45). The combination of increased synthesis and decreased degradation of ECM in obesity could decrease vascular insulin delivery and obstructs insulin and glucose transport (44).

In addition to structural roles, many ECM proteins are able to influence tissue responses to disease and injury through direct signaling processes and activation of intracellular signaling cascades (14). For instance, proteins that were differentially expressed between SAT and VAT such as decorin and biglycan bind to receptor tyrosine kinases and toll-like receptors, activating downstream mediators such as ERK, IKK, and p38 that are known to intersect insulin signaling (46, 47). ICAM and ADAM family members, which were detected in the proteomic analysis, are ligands for integrin receptors that are critical to ECM communication with cells (48). Molecules downstream of integrin signaling such FAK and ILK have been implicated in the regulation of insulin signaling in the muscle and liver (44) but with divergent effects on insulin sensitivity, suggesting ECM receptor activation may be tissue-specific and dependent on particular ligand–receptor interactions (49, 50). The differential secretion pattern of ECM proteins by SAT and VAT observed in the current study and others further supports the idea that anatomical differences in delivery of adipose-derived ECM proteins may be critical to the metabolic outcome of these secreted structural and signaling molecules.

Finally, these studies highlight the functional impact of the adipose tissue secretome on tissues that regulate glucose homeostasis. Cytokines such as IL-6, IL-13, and TNF-α have been shown to inhibit basal hepatic glycogen accumulation and glucose production, independent of insulin signaling (51–53), which may help to explain the dampening of glucose uptake and release in response to VAT in the current study, which is indicative of a generalized disruption in hepatocyte function and insulin sensitivity. Although VAT caused a significant reduction in myotube insulin sensitivity and insulin signaling, this appeared to occur in part from increased glycogen synthesis and signaling in the basal state, which was unexpected. A variety of cytokines and inflammatory mediators have been shown to stimulate glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (54–57.) The hyperproductivity of inflammatory mediators from VAT displayed in this study, combined with the functional outcome of VAT exposure on hepatocytes and myotubes, highlight the potentially critical metabolic impact of cytokines and other mediators that are not traditionally considered to be moderators of glucose regulation and homeostasis.

In summary, the current work has shown that compared with SAT, obese VAT secretes more pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators. In addition, the significance of immune response and extracellular matrix processes in differentiating these 2 anatomically diverse adipose tissues is highlighted. Finally, VAT secretome exposure results in a blunting of hepatocyte function that is indicative of insulin resistance, as well as decreased insulin sensitivity in muscle cells. The findings in this study further substantiate the current shift in the field of adipose biology to advance beyond an FFA-centric view of adipose tissue signaling and investigate the multitude of other adipose-derived lipid and protein mediators and their ability to regulate insulin sensitivity in metabolic tissues.

Abbreviations

- dbcAMP

dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FFA

free fatty acid

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- SAT

subcutaneous adipose tissue

- VAT

visceral adipose tissue

Contributor Information

Darcy Kahn, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Emily Macias, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Simona Zarini, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Amanda Garfield, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Karin Zemski Berry, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Paul MacLean, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Robert E Gerszten, The Cardiovascular Research Center and Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Andrew Libby, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Claudia Solt, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Jonathan Schoen, Department of Surgery, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Bryan C Bergman, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health General Clinical Research Center grant RR-00036, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants to B.C.B. (R01DK118149), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants to D.E.K (F31DK126393) and the Colorado Nutrition Obesity Research Center grant P30DK048520.

Author Contributions

B.C.B. is the study sponsor/funder of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. D.K. performed subject testing, sample analysis, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. E.M performed sample processing and analysis and edited the manuscript. S.Z. prepared samples and edited the manuscript. A.G. performed subject testing, helped with sample analysis, and edited the manuscript. K.Z.B. performed eicosanoid sample analysis and edited the manuscript. P.M. facilitated the use of primary rat hepatocytes and edited the manuscript. A.L. helped performed primary rat hepatocyte isolation and edited the manuscript. C.S. helped performed primary rat hepatocyte isolation and edited the manuscript. J.S. provided medical oversight, helped perform biopsies, and edited the manuscript. R.G. performed Olink analysis on the samples and edited the manuscript. B.C.B. performed subject testing, analyzed and interpreted data, and helped write the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Kahn CR, Wang G, Lee KY. Altered adipose tissue and adipocyte function in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(10):3990–4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manolopoulos KN, Karpe F, Frayn KN. Gluteofemoral body fat as a determinant of metabolic health. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34(6):949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444(7121):881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petta S, Amato MC, Di Marco V, et al. Visceral adiposity index is associated with significant fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(2):238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruiz-Castell M, Samouda H, Bocquet V, Fagherazzi G, Stranges S, Huiart L. Estimated visceral adiposity is associated with risk of cardiometabolic conditions in a population based study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116(1):39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Girard J, Lafontan M. Impact of visceral adipose tissue on liver metabolism and insulin resistance. Part II: visceral adipose tissue production and liver metabolism. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34(5):439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nielsen S, Guo Z, Johnson CM, Hensrud DD, Jensen MD. Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(11):1582–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2548–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fontana L, Eagon JC, Trujillo ME, Scherer PE, Klein S. Visceral fat adipokine secretion is associated with systemic inflammation in obese humans. Diabetes. 2007;56(4):1010–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fain JN, Madan AK, Hiler ML, Cheema P, Bahouth SW. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology. 2004;145(5):2273–2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vijay J, Gauthier MF, Biswell RL, et al. Single-cell analysis of human adipose tissue identifies depot and disease specific cell types. Nat Metab. 2020;2(1):97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Makki K, Froguel P, Wolowczuk I. Adipose tissue in obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance: cells, cytokines, and chemokines. ISRN Inflamm. 2013;2013:139239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roca-Rivada A, Bravo SB, Perez-Sotelo D, et al. CILAIR-based secretome analysis of obese visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues reveals distinctive ECM remodeling and inflammation mediators. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Assarsson E, Lundberg M, Holmquist G, et al. Homogenous 96-plex PEA immunoassay exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent scalability. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zarini S, Gijon MA, Ransome AE, Murphy RC, Sala A. Transcellular biosynthesis of cysteinyl leukotrienes in vivo during mouse peritoneal inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(20):8296–8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sinha S, Perdomo G, Brown NF, O’Doherty RM. Fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in L6 myotubes is prevented by inhibition of activation and nuclear localization of nuclear factor kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(40):41294–41301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seglen PO. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1976;13:29–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmitz-Peiffer C, Craig DL, Biden TJ. Ceramide generation is sufficient to account for the inhibition of the insulin-stimulated PKB pathway in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells pretreated with palmitate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(34):24202–24210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Darcy Kahn EM, Zarini S, Garfield A, et al. Exploring visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue secretomes in human obesity: implications for metabolic disease. Figshare2022. https://figshare.com/s/82497e33a2e7f4267142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. Place DE, Kanneganti TD. Cell death-mediated cytokine release and its therapeutic implications. J Exp Med. 2019;216(7):1474–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tanzer MC, Frauenstein A, Stafford CA, Phulphagar K, Mann M, Meissner F. Quantitative and dynamic catalogs of proteins released during apoptotic and necroptotic cell death. Cell Rep. 2020;30(4):1260–1270.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tam IYS, Ng CW, Lau HYA, Tam SY. Degradation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by tryptase co-released in immunoglobulin E-dependent activation of primary human cultured mast cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;177(3):199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ito A, Mukaiyama A, Itoh Y, et al. Degradation of interleukin 1beta by matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(25):14657–14660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nitta CF, Orlando RA. Crosstalk between immune cells and adipocytes requires both paracrine factors and cell contact to modify cytokine secretion. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huber J, Kiefer FW, Zeyda M, et al. CC chemokine and CC chemokine receptor profiles in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue are altered in human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(8):3215–3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guzik TJ, Skiba DS, Touyz RM, Harrison DG. The role of infiltrating immune cells in dysfunctional adipose tissue. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(9):1009–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martinez-Reyes CP, Gomez-Arauz AY, Torres-Castro I, et al. Serum levels of interleukin-13 increase in subjects with insulin resistance but do not correlate with markers of low-grade systemic inflammation. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:7209872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Binisor ID, Moldovan R, Moldovan I, Andrei AM, Banita MI. Abdominal obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus are associated with higher seric levels of IL 4 in adults. Curr Health Sci J. 2016;42(3):231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnson DR, O’Connor JC, Satpathy A, Freund GG. Cytokines in type 2 diabetes. Vitam Horm. 2006;74:405–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Connor JC, Sherry CL, Guest CB, Freund GG. Type 2 diabetes impairs insulin receptor substrate-2-mediated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in primary macrophages to induce a state of cytokine resistance to IL-4 in association with overexpression of suppressor of cytokine signaling-3. J Immunol. 2007;178(11):6886–6893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hardwick JP, Eckman K, Lee YK, et al. Eicosanoids in metabolic syndrome. Adv Pharmacol. 2013;66:157–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pulcinelli FM, Biasucci LM, Riondino S, et al. COX-1 sensitivity and thromboxane A2 production in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients under chronic aspirin treatment. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(10):1279–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Graziani F, Biasucci LM, Cialdella P, et al. Thromboxane production in morbidly obese subjects. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(11):1656–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang W, Zhong X, Guo J. Role of 2series prostaglandins in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (review). Int J Mol Med. 2021;47(6):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Henkel J, Neuschafer-Rube F, Pathe-Neuschafer-Rube A, Puschel GP. Aggravation by prostaglandin E2 of interleukin-6-dependent insulin resistance in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2009;50(3):781–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hsieh P-S, Jin J-S, Chiang C-F, Chan P-C, Chen C-H, Shih K-C. COX-2-mediated inflammation in fat is crucial for obesity-linked insulin resistance and fatty liver. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(6):1150–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan P-C, Hsiao F-C, Chang H-M, Wabitsch M, Hsieh P-S. Importance of adipocyte cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2-prostaglandin E receptor 3 signaling in the development of obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. FASEB J. 2016;30(6):2282–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Inazumi T, Yamada K, Shirata N, et al. Prostaglandin E2-EP4 axis promotes lipolysis and fibrosis in adipose tissue leading to ectopic fat deposition and insulin resistance. Cell Rep. 2020;33(2):108265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ceddia RP, Lee D, Maulis MF, et al. The PGE2 EP3 receptor regulates diet-induced adiposity in male mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(1):220–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Danneskiold-Samsoe NB, Sonne SB, Larsen JM, et al. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in adipocytes reduces fat accumulation in inguinal white adipose tissue and hepatic steatosis in high-fat fed mice. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Coll T, Palomer X, Blanco-Vaca F, et al. Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition exacerbates palmitate-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells. Endocrinology. 2010;151(2):537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leighton B, Budohoski L, Lozeman FJ, Challiss RA, Newsholme EA. The effect of prostaglandins E1, E2 and F2 alpha and indomethacin on the sensitivity of glycolysis and glycogen synthesis to insulin in stripped soleus muscles of the rat. Biochem J. 1985;227(1):337–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Williams AS, Kang L, Wasserman DH. The extracellular matrix and insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(7):357–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ahmad K, Lee EJ, Moon JS, Park S-Y, Choi I. Multifaceted interweaving between extracellular matrix, insulin resistance, and skeletal muscle. Cells. 2018;7(10):148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reszegi A, Horvath Z, Karaszi K, et al. The protective role of decorin in hepatic metastasis of colorectal carcinoma. Biomolecules. 2020;10(8):1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Karsdal MA, Manon-Jensen T, Genovese F, et al. Novel insights into the function and dynamics of extracellular matrix in liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308(10):G807–G830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 19):3901–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kang L, Ayala JE, Lee-Young RS, et al. Diet-induced muscle insulin resistance is associated with extracellular matrix remodeling and interaction with integrin alpha2beta1 in mice. Diabetes. 2011;60(2):416–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Williams AS, Kang L, Zheng J, et al. Integrin alpha1-null mice exhibit improved fatty liver when fed a high fat diet despite severe hepatic insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(10):6546–6557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. da Rocha AF, Liboni TF, Kurauti MA, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha abolished the suppressive effect of insulin on hepatic glucose production and glycogenolysis stimulated by cAMP. Pharmacol Rep. 2014;66(3):380–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dent JR, Chowdhury MK, Tchijov S, Dulson D, Smith G. Interleukin-6 is a negative regulator of hepatic glucose production in the isolated rat liver. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2016;122(2):103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stanya KJ, Jacobi D, Liu S, et al. Direct control of hepatic glucose production by interleukin-13 in mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Busquets S, Figueras M, Almendro V, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Interleukin-15 increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. An antidiabetogenic effect of the cytokine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760(11):1613–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Roher N, Samokhvalov V, Diaz M, MacKenzie S, Klip A, Planas JV. The proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases the amount of glucose transporter-4 at the surface of muscle cells independently of changes in interleukin-6. Endocrinology. 2008;149(4):1880–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jiang LQ, Franck N, Egan B, et al. Autocrine role of interleukin-13 on skeletal muscle glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetic patients involves microRNA let-7. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(11):E1359–E1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pu J, Peng G, Li L, Na H, Liu Y, Liu P. Palmitic acid acutely stimulates glucose uptake via activation of akt and ERK1/2 in skeletal muscle cells. J Lipid Res. 2011;52(7):1319–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.