Abstract

Bile acids wear many hats, including those of an emulsifier to facilitate nutrient absorption, a cholesterol metabolite, and a signaling molecule in various tissues modulating itching to metabolism and cellular functions. Bile acids are synthesized in the liver but exhibit wide-ranging effects indicating their ability to mediate organ-organ crosstalk. So, how does a steroid metabolite orchestrate such diverse functions? Despite the inherent chemical similarity, the side chain decorations alter the chemistry and biology of the different bile acid species and their preferences to bind downstream receptors distinctly. Identification of new modifications in bile acids is burgeoning, and some of it is associated with the microbiota within the intestine. Here, we provide a brief overview of the history and the various receptors that mediate bile acid signaling in addition to its crosstalk with the gut microbiota.

Keywords: bile acids, nuclear receptor, G protein–couple receptor, synthesis, enterohepatic recirculation, gut microbiota

Bile acids, the body's natural detergent, are fundamentally known for their role in lipid digestion, but over the last two decades, their function as signaling molecules has been uncovered. There has been a major resurgence of interest in investigating bile acids, with obeticholic acid (OCA), one of its synthetic derivatives, being used in clinics for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and due to its interactions with the gut microbiota. Several reviews have elegantly and extensively discussed bile acid synthesis, chemistry, transport, metabolic roles, and its crosstalk with the gut microbiota (1–5). Therefore, we highlight historical and major developments focusing on the different receptors and their potency to specific bile acids, novel amino acid conjugations, and interactions with the gut microbiota.

Bile Acids—A Historical Perspective

Although the bile acid structure, function, and application have been investigated for more than 150 years, new signaling pathways and their varied roles in metabolism and overall physiology are still being uncovered. The study of bile acids began with Strecker isolating the primary bile acid, cholic acid (CA), in 1848 through combustion analysis, marking the discovery of the first bile acid (6). This discovery was followed by the identification of several distinct bile acids from different species (7). In the early 1900s, bile acids were mainly used as tonics and laxatives to increase bile flow in cholestatic patients despite the lack of well-controlled efficacy studies (2, 6). The field began to gather momentum in the 1930s when cortisone was commercialized to treat rheumatoid arthritis because deoxycholic acid (DCA) could be used to synthesize cortisone (7, 8). The development of gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy to analyze bile acid levels and composition further accelerated the field (9, 10). Of note, patients with hypercholesterolemia were fed CA in 1965. It was found that the CA diet suppressed bile acid and cholesterol synthesis (11, 12). The prospect of therapeutic benefits of bile acids and advances in analytical methods led to the large-scale synthesis of conjugated bile acids. Delineating the kinetics and intermediates of bile acid synthesis was arduous and took 4 decades to refine (13–17).

The next breakthrough came in 1972 when chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) was shown to promote gallstone dissolution, a considerable advancement in treating hepatobiliary diseases (12, 18). Unfortunately, the hepatotoxicity of CDCA feeding was a major concern that led to the exploration of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) as an alternative for gallstone dissolution. UDCA not only displayed higher efficacy but also minimal hepatotoxicity (18–22). In fact, the beneficial effects of UDCA were subsequently harnessed to mitigate the disease progression of primary biliary cirrhosis and alleviate the symptoms of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (23–25). Clinical use for UDCA has since expanded to also treat gallstones after bariatric surgery, low phospholipid–associated cholelithiasis, cystic fibrosis–associated liver injury, and hepatic injury following stem cell transplantation (26–30). While UDCA remains a drug of choice for treating cholestatic liver disease, its susceptibility to side chain amidation and lack of effectiveness against cholangiopathies led to the exploration of 24-norursodeoxycholic acid (norUDCA) as a therapeutic alternative. The shortened side chains protect norUDCA from taurine and glycine amidation and allows for cholehepatic shunting (31–33). As norUDCA promotes a bicarbonate-rich bile flow, and bile acid detoxification (34), it is currently in phase 3 clinical trials as a therapeutic for treating primary sclerosing cholangitis (35–39). In addition to treating cholestatic liver diseases, norUDCA and UDCA may alleviate NASH/nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, but, further studies are warranted to confirm their efficacy (35, 40).

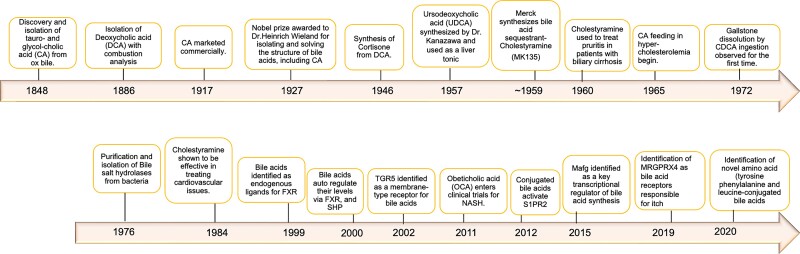

The therapeutic potential of bile acids underscored their importance in health and disease and was instrumental in pioneering their large-scale medical synthesis. A summary of the major advancements and discoveries in the field is represented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of historical bile acid research and innovation.

Bile Acid Structure

In 1927, a four-ring structure with a varying side chain of carbon atoms was first proposed for bile acids (41, 42). X-ray diffraction studies on vitamin D, cholesterol, and ergosterol showed that the ring structures of these molecules were similar to that of bile acids (43). This overlap in structure between cholesterol and bile acids led researchers to speculate cholesterol is a precursor of CA, but the inability of dietary cholesterol supplements to increase bile acid levels questioned this hypothesis. Radioactive labeling of cholesterol eventually led biochemists to observe deuterium incorporation into CA (44), thus solidifying that cholesterol was the true precursor for CA.

All bile acids share a saturated tetracyclic hydrocarbon perhydrocyclopentanophenanthrene system (steroid nucleus), which consists of three 6-carbon rings and one 5-carbon ring and are typically in the cis-conformation. Distinct side chains, stereochemistry, and hydroxyl groups gave rise to the varied bile acids. All primary bile acids synthesized de novo in the liver are identifiable with a 7α-hydroxyl group. The hydroxyl groups (positions 3, 7, and/or 12 in mammals) and the side chain (positions C18 and C19) of bile acids provide unique characteristics to the different bile acid species. Thus, bile acids possess both a hydrophilic (α) and hydrophobic (β) side (45), and their hydrophobic index varies distinctly (46). Their amphipathic nature enables micelle formation and the solubilization of lipids and cholesterol in the intestinal tract. Consequently, overall bile acid pool composition and concentration of individual bile acid species affect biological outcomes.

Primary and Secondary Bile Acids

The primary bile acids synthesized in human hepatocytes are CA and CDCA, while murine hepatocytes synthesize muricholic acid (MCA), CA, and CDCA. At least 17 liver enzymes are known to be involved in this process, which is divided into 2 distinct pathways termed the “classical” and “alternative” bile acid synthesis pathways (47). The classical, or neutral pathway, is responsible for producing approximately 90% or approximately 75% of total bile acids in humans and mice, respectively. The process is initiated with the 7α-hydroxylation of cholesterol by P450 cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), which is the rate-limiting step (47–49). The ratio between CA and CDCA in the bile acid pool is determined by microsomal sterol 12α-hydroxylase (CYP8B1). At basal conditions, the liver produces almost equal amounts of CA and CDCA (47, 50). The alternative, or acidic pathway, accounts for approximately 9% or approximately 25% of the bile acid pool in humans and mice, respectively (51, 52). This begins with the C27-hydroxylation of cholesterol by mitochondrial 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1). The intermediates are then converted by the oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7B1) into CDCA in humans and MCA in mice (47, 50). CYP2C70 was identified to synthesize MCA, a 6-hydroxylated bile acid that is highly present in mice (53). Of note, the deletion of Cyp2c70 in mice exhibited human-like bile acid metabolism (54), underscoring the role of MCA in contributing to the species differences. Bile acids are then conjugated with either glycine or taurine, which makes them less toxic and helps with their solubility (55). In humans, the number of glycine conjugates is three times higher than taurine conjugates (56, 57) whereas in mice, approximately 95% are taurine conjugated (58). Thus, when using rodent models to understand bile acid homeostasis, species-specific differences must be carefully considered and several reviews and reports have covered this aspect (59–62).

Once bile acids are synthesized, conjugated, and secreted into the intestine, approximately 95% are reabsorbed in the terminal ileum and recirculated back to the liver. A small percentage of the bile salts (∼5%) are deconjugated by bacterial bile salt hydrolases and then absorbed or metabolized to secondary bile acids by bacterial 7α-dehydroxylase. CA and CDCA in the intestine are converted to DCA and LCA, respectively. Notably, LCA is more toxic of the two and is passively absorbed at a lower rate. The processes that detoxify LCA differ between humans and mice. Human LCA can be secreted into the bile after being sulfated and N-acylamidated in the liver, while murine LCA is eliminated through the feces after it is hydroxylated at the C-6 and/or C-7 positions. LCA can also be sulfated and eliminated through urination. In addition, LCA can be converted to hyocholic acid (HCA) and UDCA in humans, whereas it can be 7α-hydroxylated to CDCA and then converted to UDCA, α-, β-, and ω-MCA, HCA, and hyodeoxycholic acid (HDCA) in mice (50, 63, 64). The differences in secondary bile acid clearance and metabolism can contribute toward humans having a more hydrophobic bile acid profile in contrast to a more hydrophilic profile in mice (61, 65, 66).

Uncommon and Novel Bile Acids and Influence of the Gut Microbiota

The gut microbiome is responsible for deconjugating and converting primary to secondary bile acids. In fact, microbiota-mediated bile acid modifications and their effect on health have been reported (67–70). Conversely, bile acids can inhibit the growth of certain bacterial strains. Thus, gut microbial diversity and bile acid composition influence each other, and their interactions can be altered when bile acid homeostasis is disrupted or upon the onset of metabolic diseases (71–76).

Unusual 7-oxygenated bile acids (3β-hydroxy-Δ5), NPCBA1 (3β-hydroxy,7β-N-acetylglucosaminyl-5-cholenoic acid) and NPCBA2 (3β,5α,6β-trihydroxycholanoyl-glycine) have been observed in Niemann-Pick C (NPC) disease, which is a cholesterol and fat transportation disorder. The concentrations of 7-oxygenated bile acids are elevated in these patients, which may contribute to cholestasis, and at the same time, can also potentially serve as biomarkers (77, 78) 3β-hydroxy(iso)-bile acids are another prominent class of bile acids synthesized by Ruminnococcus gnavus (79). Diet can influence the gut microbiota and subsequently regulate the levels of 3β-hydroxy bile acids and possibly other bile acids (80, 81).

Although amino acid–conjugated bile acids have been identified, and the synthesis of taurine and glycine conjugated bile acids well recognized in mice and humans (82–85), their physiological relevance is yet to be fully understood. A recent global mapping study in germ-free and specific-pathogen free (SPF) mice revealed that the gut microbiota could conjugate CA with either phenylalanine (phenylalanocholic acid), tyrosine (tyrosocholic acid), or leucine (leucocholic acid). These conjugations are novel and need to be actively explored (86). Intriguingly, taurine-conjugated bile acids were found to be abundant in the germ-free mice, while secondary bile acids were elevated along with higher Shannon diversity index in the cecum and colon of the SPF mice. Thus, the gut microbiome plays an inherent role in modulating bile acid conjugation and metabolism. Interestingly, amino acid–conjugated bile acid concentrations are also increased in the small intestine and have been demonstrated to be agonists for farnesoid X receptor (FXR) in vitro. Further, cultured human gut microorganisms can produce these amino acid–conjugated bile acids and were elevated in human patients with inflammatory bowel disease or cystic fibrosis as measured by their spectral signatures (86).

Apart from diseased states, age-associated changes in bile acid metabolism and its composition have been extensively studied in rats (87), mice (88), and humans (89). Aging has been shown to affect the gut microbiota and the subsequent bile acid profile (90). In fact, interactions between bile acids and gut microbiome diversity have been observed in newborn mice, wherein taurocholic acid (TCA) and β-tauromurocholic acid (TβMCA) accelerate the maturation of bacteria (91). Sardinian centenarians displayed unique gut microbiota signatures distinct from younger and older individuals (92). Similarly, Japanese centenarians harbored gut microbiome that produced unique isoforms of LCA (iso-, 3-oxo-, 3-oxoallo-, and isoallo-), and the novel isoallo-LCA can inhibit the growth of gram-positive bacteria (93, 94). These findings delineate a link between specific bile acid isoforms and aging in such a way that some of them strongly correlate with health while others with disease.

Bile Acid–Activated Nuclear Receptors

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are a widely expressed superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors that exhibit a broad range of physiological and pathological roles (95–98). NRs share structural features with a conserved N-terminal DNA-binding domain, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (50, 99). Bile acids act as an endogenous ligand for certain NRs with predominant actions through FXR (100–102). Other NRs, such as pregnane X receptor (PXR) (103), vitamin D receptor (VDR) (104), and liver X receptor (LXR) (105) have been shown to be activated by secondary bile acids. In addition, each bile acid preferentially binds and activates their target receptors. This data from rodents and humans has been compiled in Table 1. Once bile acid binds the ligand-binding domain, the activation function region facilitates interaction and recruitment of coregulators. Thus, bile acids can modulate the transcriptional control of genes. Conversely, these NRs act as sensors to modulate bile acid concentrations primarily within the hepatocytes and enterocytes and mediate the metabolic consequences of bile acid signaling. NRs can also be found in other bile acid-related tissues as seen in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Natural bile acids as ligands and activators of nuclear receptors and G protein–coupled receptors

| Nuclear receptors | Model | Method | Bile acids and concentrations | Potency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fxr | Cell-free | Ligand-binding assay—human FXR | CDCA (4.5 μM) | LCA > TLCA > CDCA > GLCA > GCDCA∼TCDCA > DCA > GDCA∼TDCA > CA∼GCA∼CA; binding affinity EC50 | (106) |

| GCDCA (10 μM) | |||||

| TCDCA (10 μM) | |||||

| CA (>1000 μM) | |||||

| GCA (>1000 μM) | |||||

| TCA (>1000 μM) | |||||

| LCA (3.8 μM) | |||||

| GLCA (4.7 μM) | |||||

| TLCA (3.8 μM) | |||||

| DCA (100 μM) | |||||

| GDCA (≥500 μM) | |||||

| TDCA (≥500 μM) | |||||

| CV-1 cells | Transfected with murine or human FXR and CAT assay was performed after bile acid treatment | CDCA, CA, LCA, DCA (100 μM) | CDCA > DCA > LCA > CA | (106) | |

| CV-1 cells | Coexpressed human IBAT and FXR; bile acid treatment | CDCA, GCDCA, TCDCA, GCA, TCA, LCA, GLCA, TLCA, GDCA, TDCA (3 μM) | TCDCA ≈ GCDCA ≈ TLCA ≈ GLCA > TDCA ≈ GDCA > CDCA > TCA ≈ GCA; conjugated bile acids need a uptake transporter and exhibit strong affinity for FXR | (106) | |

| CV-1 cells | Cotransfected with rat FXR and luciferease reporter gene; bile acid treatment | CDCA, TCDCA, GCDCA, CA, TCA, GCA, DCA, TDCA, LCA (50 μM) | CDCA > LCA > DCA > CA∼GCDCA∼GCA∼TCDCA∼CA∼TDCA | (107) | |

| HepG2 cells | Transfected with human FXR and luciferease reporter gene; bile acid treatment | EC50: CDCA (10 μM) and DCA (10 μM) | CDCA > DCA > GDCA ≥ CA ≈ TCDCA | (107) | |

| CV-1 cells | Transfected with CMX-β-gal, EcRE ×6 and FXR with RXR or mutant RXR | CDCA, DCA, LCA, CA, UDCA (100 μM) | CDCA > DCA > LCA > UDCA > CA | (108) | |

| CV-1 cells | Transfected with CMX-β-gal, EcRE ×6 and FXR with RXR and liver bile acid transporter | CDCA, GCDCA, TCDCA, CA, GCA, TCA, LCA, GLCA, TLCA, DCA, GDCA, TDCA (100 μM) | DCA > TDCA > TCA > GDCA > GCA > CA > CDCA ≥ GCDCA > TCDCA > GLCA > LCA∼TLCA | (108) | |

| Cell-free | Scintillation proximity binding assay | CDCA (17 ± 3 μM) | LCA > CDCA > TCDCA > GCDCA > DCA > UDCA > CA > TCA > GCA, binding affinity IC50 | (109) | |

| DCA (131 ± 8 μM) | |||||

| CA (586 ± 64 μM) | |||||

| UDCA (185 ± 26 μM) | |||||

| LCA (3 ± 0.5 μM) | |||||

| GCDCA (32 ± 4 μM) | |||||

| TCDCA (19 ± 0 μM) | |||||

| GCA (800 ± 0 μM) | |||||

| TCA (733 ± 0 μM) | |||||

| HepG2 cells | Transfected with pcDNA3.1-hFXR, pcDNA3.1-hRXR, pGL3-enhancer-hBSEP-promoter-Luc, pCMV-lacZ; and treated with various concentrations of bile acids | CDCA (0-75 μM), CA (0-600 μM), DCA (0-100 μM), UDCA (0-400 μM) | CDCA > DCA > CA > UDCA | (109) | |

| C57BL/6 mice | Diet regimen for 7 d | 0.01-0.3%, w/w of CA-, CDCA-, DCA-, or LCA-supplemented diet | CA and DCA > CDCA and LCA (Diet) | (110) | |

| Shp (orphan) | HepG2 cells | Transfected with human FXR, RXR and FXREPLTPx4-tk-luc reporter plasmid; and treated with various concentrations of bile acids and precursors | 5β-cholestane-3α,7α,12α,26-tetrol (26-OH-THC) (20 μM) | DHCA∼CDCA > 26-OH-DHC > 25-OH-THC > THCA > 26-OH-THC > CA | (111) |

| 3α,7α,12α-trihydroxy-5 β-cholestanoic acid (THCA) (50 μM) | |||||

| CA (50 μM) | |||||

| β-cholestane-3α,7α,26-triol (26-OH-DHC) (20 μM) | |||||

| 3α,7α-dihydroxy-5β-cholestanoic acid (DHCA) (30 μM) | |||||

| CDCA (50 μM) | |||||

| 5β-cholestane-3α,7α,12α,25-tetrol (25-OH-THC) (20 μM) | |||||

| Human primary hepatocyte cultures | Treated with various concentrations of bile acids; RT-PCR of FXR downstream targets was used for analysis | CA, CDCA, DCA, LCA, UDCA (10, 30, 100 μM) | CDCA (100 μM) > CDCA (30 μM) > CA (100 μM) > DCA (30uM) ≈ DCA (100 μM) > CA (30 μM) > LCA (30 μM) > CDCA (10 μM) > LCA (100 μM) > LCA (10 μM) > CA (10 μM) ≈ DCA (10 μM) ≈ UDCA (10, 30, 100 μM) | (112) | |

| Lxr | CV-1 cells | Transfected with human LXR, RXR, and LXRESREBP-1cx4-tk-luc reporter; and treated with various concentration of bile acids | 26-OH-THC, 3α,7α,12α-trihydroxy-5β-cholest-24-enoic acid (Δ24-THCA), 26-OH-DHC, DHCA, CDCA (20, 50 μM) | FXR-activating bile acids and precursors do not activate LXR | (111) |

| HEK293 cells | Transfected with pGL3/UREluc reporter gene, pSG5/hRXRα, CMX/hLXRα, and pSG5/hGrip1; treated cells with 5β-cholanoic acid methyl esters (CAME) | Hyodeoxycholic acid (HDCA) and tauro-hyodeoxycholic acid (THDCA) | ED50: HDCA∼17 μM; THDCA∼3 μM | (105) | |

| Vdr | HEK293 cells | Transfected with GAL4-SRC-1, VP16-VDR, and GAL4-responsive luciferase reporter; activation assay done in the presence or absence of IBAT | CDCA, LCA, TLCA, GLCA, 6-keto-LCA, 3-keto-LCA (30 μM) | LCA > 3-keto-LCA > GLCA > 6-keto-LCA > CDCA > TLCA; EC50: LCA (8 μM) and 3-keto-LCA (3 μM) | (104) |

| C57BL/6 mice | VDR(+/+) and VDR(−/−) mice treated with LCA | 0.3 or 0.8 mmol/kg | LCA induced Cyp24a1 as effective as 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] in small intestine | (113) | |

| Tgr5 | HEK293 cells | Transfected with hTGR5 and treated with various bile acids to induce cAMP production | LCA, DCA, CDCA, CA, UDCA | EC50: LCA (35 nM) > DCA (575 nM) > CDCA (4004 nM) > CA (>10 μM); UDCA induced cAMP production | (114) |

| NCI-H716 cells | Transfected with hTGR5 and treated with various bile acids to induce cAMP production | LCA, DCA, CDCA, CA, UDCA | LCA > DCA > CDCA > CA | (114) | |

| CHO cells | Transfected with TGR5-GFP and treated with various bile acids to induce cAMP production | TLCA, LCA, DCA, CDCA, CA | EC50: TLCA (0.33 μM) > LCA (0.53 μM) > DCA (1.01 μM) > CDCA (4.43 μM) > CA (7.72 μM) | (115) | |

| S1pr | HEK293 cells | GFP-S1PR1/2 wereexpressed and then treated with bile acid to assess ERK1/2 activation | TCA (5 and 50 μM) | TCA (5 μM) ≈ TCA (50 μM); only S1PR2 was active | (116) |

| Primary rat hepatocytes | Treated with various conjugated bile acids against a S1PR antagonist; Western blot analysis. The read out used was ERK1/2 and AKT expression. | TCA, TDCA, TUDCA, GCA, GDCA (50 μM) | GDCA > GCA∼TUDCA∼TDCA > TCA | (116) | |

| Mrgprx4 | HEK293 cells | Murine ortholog and other related human MRGPRs were transfected individually in cells stably expressing Gα15, and then treated with various concentrations of bile acids | DCA, CDCA, CA, UDCA, TDCA, TCDCA, TCA | EC50: UDCA (4.93 μM) > DCA (6.19 μM) > TDCA (18.9 μM) > TCDCA (30.1 μM) > CDCA (46.2 μM) >TCA (178.8 μM) > CA (430.5 μM) | (117) |

| 129svj/C57BL6J mice | Mice expressing humanized MRGPRX4 were injected with various bile acids to assess scratching bouts/pruritus | 50 μL injections: DCA (1 mM), TDCA (1 mM), UDCA (2 mM), CDCA (2 mM) | DCA > TDCA∼UDCA∼CDCA | (117) | |

| HEK293T cells | Stable cell lines expressing MRGPRX4 were treated with various concentrations of bile acids and assessed using the TGFα shedding and FLIPR assay | DCA, CDCA, CA, TDCA, GDCA, TLCA, LCA, TCDCA, GCDCA, TCA, GCA | TGFα shedding EC50: DCA (2.7 μM) > TLCA (6.1 μM) > CDCA (15.0 μM) ≈ CA 15.2 μM) > TDCA (28.0 μM) ≈ GDCA (28.3 μM) > LCA (88.0 μM) >TCDCA (>100 μM) ≈ GDCA (100 μM) | (97) | |

| FLIPR EC50: DCA (2.6 μM) > CA (6.9 μM) > LCA (9.3 μM) > TDCA (14.1 μM) ≈ GDCA (14.4 μM) > CDCA (15.9 μM) > TLCA (>50 μM) ≈ GCDCA (>50 μM) ≈ TCA (>50 μM) ≈ GCA (>50 μM) > TCDCA (>100 μM) | |||||

| Rat dorsal root ganglion | Cultured rat DRG electrically transfected with MRGPRX4; treated with bile acids to assess Ca2+ signal | DCA and CA (10 μM) | DCA > CA | (97) | |

| HEK293T cells | Transfected with MRGPRX4 and treated with mixture of serum bile acids from human patients with liver disease to assess Ca2+ signal | GCA, TCA, GCDCA, TCDCA abundance highest among 12 bile acids measured in diseased patients | Ca2+ signal increased from diseased serum mixture; DCA found to not contribute to itchiness | (97) | |

| Pxr | CV-1 cells | Transfected with expression plasmids for mouse PXR and reporter plasmid (Cyp3a23)2-tk-CAT followed by treatment with bile acids | CDCA, CA, DCA, LCA, 3-keto-LCA (100 μM) | 3-keto-LCA > LCA > DCA > CDCA∼CA | (118) |

| CV-1 cells | Transfected with expression plasmids for human PXR and reporter plasmid (Cyp3a23)2-tk-CAT and then treated with bile acids | CDCA, CA, DCA, LCA, 3-keto-LCA (100 μM) | 3-keto-LCA > LCA > DCA > CDCA∼CA | (118) | |

| 129/Sv mice | PXR-/- micetreated with i.p. (LCA or corn oil) 2×/d for 4 d | LCA (0.125 mg/g) | LCA induced hepatic Cyp3a11 and Oatp2 in WT, not Tg mice | (118) | |

| CV-1 cells | Transfected with mouse PXR-response reporter tk-3A4-Luc and expression vector for PXR | CDCA, DCA, LCA (100 μM) | DCA > LCA > CDCA | (103) | |

| CV-1 cells | Transfected with human PXR-response reporter tk-3A4-Luc and expression vector for PXR | CDCA, DCA, LCA (100 μM) | DCA > LCA > CDCA | (103) | |

| 129/Sv mice | PXR+/+ and PXR-/- and transgenic mice expressing SXR controlled by the albumin promoter (Alb-VPSXR), were treated by gavage 2×/d for 4 d | LCA (8 mg/d) | LCA showed histological changes in twice as many mice compared to WT. Alb-VPSXR showed sustained SXR can protect against LCA-induced hepatotoxicity | (103) | |

| FABP-VP-hPXR Tg mice | Transgenic mice expressing human PXR under the control of FABP promoter; mice treated with LCA enema 2×/d for 5 wk | LCA (5 mM) | LCA activated PXR in transgenic mice | (119) |

Abbreviations: Akt, protein kinase B; cAMP, 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate; CA, cholic acid; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic acid; DCA, deoxycholic acid; DHCA, dihydroxycholestanoic acid; EC50, half maximal effective concentration; FABP, fatty acid binding protein; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GCA, glycocholic acid; GCDCA, glycochenocholicdeoxycholic acid; GDCA, glycodeoxycholic acid; GLCA, glycolithocholic acid; HDCA, hyodeoxycholic acid; i.p., intraperitoneally; LCA, lithocholic acid; LXR, liver X receptor; MRGPRX4, mas-related G-protein coupled receptor X4; PXR, pregnane X receptor; RXR, retinoid X receptor; SHP, small heterodimer partner; S1PR, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor; SXR, steroid and xenobiotic receptor; TGR5, Takeda G-protein coupled receptor 5; TCA, taurocholic acid; TCDCA, taurochenodeoxycholic acid; TDCA, taurodeoxycholic acid; THCA, trihydroxycholestanoic acid; THDCA, taurohyodeoxycholic acid; TLCA, taurolithocholic acid; TGFα, transforming growth factor α; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; VDR, vitamin D receptor; WT, wild-type.

Figure 2.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of human and murine nuclear receptors (NRs) and G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) in tissues involved in bile acid metabolism. Relative mRNA expression of NRs and GPCRs are denoted by their font size to signify how abundant they are in those tissues. The compiled mRNA expression data were obtained from the papers cited next to each nuclear receptor in paranthesis. Human MRGPXR4 and similar murine orthologs Mrgpra1 and Mrgprb2 genes are found in trigeminal ganglia and dorsal root ganglia (97,117,120,121). Human FXRα (95, 122, 123), SHP (124, 125), LXRα/β (95,126–128), VDR (95, 129, 130), TGR5 (115, 131), S1PR2 (132, 133), and PXR (95,134–143). Murine Fxrα (96), Shp (96, 144), Lxrα/β (145, 146), Vdr (96, 129), Tgr5 (147), S1pr2 (148, 149), and Pxr (96, 135, 150). *Asterisk denotes contradictory data for mRNA expression in that tissue. Created with BioRender.com.

Farnesoid X Receptor

FXR was discovered in 1995 as a retinoid X receptor (RXR)-interacting partner primarily expressed in the liver, intestine, kidney, and adrenal gland (100). It has since been well recognized as the endogenous bile acid receptor. Of note, in vitro studies have demonstrated that CDCA, DCA, and LCA can activate FXR with CDCA being the most potent (107, 108). Intriguingly, it has been reported that mice fed CA and DCA exhibited stronger FXR activation than CDCA and LCA (110). On the other hand, FXR orchestrates bile acid homeostasis as evident from Fxr knockout (FxrKO) mice, which exhibited altered gene expression of Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1, and Cyp27a1, ileal bile acid binding protein (Ibabp), small heterodimer partner (Shp), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (Pparα), and Lxr. In addition, FxrKO mice accumulated more serum bile acid on a CA-fed diet, highlighting its importance in bile acid regulation (151).

Over the last 2 decades, the crucial role of FXR in regulating bile acid synthesis and transportation has been elucidated. Notably, FXR displays tissue-specific functions (152). FXR orchestrates the negative feedback for suppressing bile acid synthesis by inducing another NR, SHP, which inhibits the Cyp7a1 gene expression in the liver (153, 154). FXR/SHP also coordinates the repression of ileal apical sodium dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT) expression to prevent bile acid reabsorption (155, 156). Furthermore, FXR induces the intestinal transcription of fibroblast growth factor 15 (FGF15) to regulate bile acid levels and other metabolic processes. The ileal FXR-FGF15 axis is one of the mediators of the gut-liver crosstalk such that FGF15 circulates to the liver, where it acts via β-Klotho and fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4) and along with hepatic SHP (157, 158) suppresses bile acid synthesis. Moreover, FGF15 also stimulates gallbladder filling such that Fgf15KO mice were unable to fill their gallbladder even after fasting (159, 160).

In addition to the liver and the intestine, the kidney enables the filtering of bile acids by either reabsorbing it in the renal proximal tubule by an Na+-dependent mechanism or excreting it in urine (161, 162). FXR is highly expressed primarily in the tubular cells of the kidneys, and its activation allows for metabolic waste clearance through organic cations transporter (163), maintenance of glutathione homeostasis during obesity and protection against ischemia-reperfusion damage (164). These data suggest the importance of FXR in regulating kidney function.

Fxr mutations or deficiencies affect humans and mice differently. Although constitutive and conditional knockout of Fxr is tolerated and nonlethal in mice, it can alter many biological processes, such as inflammatory response, tumorigenesis (165, 166), intestinal barrier function (167), gut microbiome composition, lipid (71), and bile acid metabolism (152). Interestingly, the loss of FXR in obese mice models attenuated weight gain and improved glucose homeostasis (168), indicating that murine FXR deficiency may be beneficial in these conditions. However, in humans, mutant Fxr variants are linked to progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, which can rapidly progress to end-stage liver disease in infants and lead to neonatal death (169–171).

Nevertheless, the metabolic roles of FXR makes it an attractive therapeutic target. There have been several clinical trials with synthetic and semi-synthetic FXR agonists to evaluate its efficacy for type 2 diabetes, primary biliary cholangitis, and NASH (172, 173). The drawback of these agonists is the onset of pruritus (itchy skin), which occurs in a dose-dependent manner. This side effect is possibly due to the activation of Takeda G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) 5 (TGR5) (174), which has been linked to pruritus and increased gallbladder volume (175–177). Other potential side effects of FXR agonists include the worsening of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio by OCA (178) and increase of hepatotoxicity by MET-409 (179).

The majority of therapeutic studies focus on FXR agonists and not its antagonists (173). But FXR antagonism has been reported to be beneficial in cholestasis (180), hypercholesterolemia (181), type 2 diabetes, cancer, and so on (173, 182). Intriguingly, intestinal FXR agonism has also been shown to be therapeutically beneficial (183, 184). For example, tempol treatment increased TβMCA, a natural antagonist of FXR, resulting in altered gut microbiome composition, reduced weight gain, and attenuated obesity in response to high-fat diet (185). While fexaramine, an intestine-specific FXR agonist, increased adipose tissue browning and reduced diet-induced weight gain, improved hepatic glucose metabolism, and decreased systemic inflammation (186). Taken together, these studies show modulating FXR can be beneficial to combat metabolic diseases.

Small heterodimer partner

Classically, SHP is considered a downstream signaling molecule of FXR. SHP is involved in regulating bile acid levels so that its constitutive or liver- or intestine-specific deletion results in altered bile acid homeostasis (187–190). There is no evidence that bile acids act as ligands for SHP, but they indirectly regulate SHP function (100). SHP is an orphan NR that lacks the conserved DNA-binding domain but it exerts its function through protein-protein interaction by forming heterodimers with other proteins to regulate biological processes (191). Although Shp transcript levels are reduced in FxrKO mice, it is not absent. Of note, Fxr and Shp DoubleKO (DKO) mice exhibited early-onset juvenile cholestasis, liver injury, and dysregulated bile acid homeostasis in contrast to the individual Fxr or ShpKOs (192), suggesting coordinate and FXR-independent roles for SHP. Several proteins can bind to the promoter region of the Shp gene to regulate its expression (188). Although FXR is known to stimulate Fgf15 transcript levels (157), we observed that loss of intestinal Shp expression was sufficient to inhibit the acute CA-mediated increase in ileal Fgf15 messenger RNA levels (188). Interestingly, 3-D imaging of CA-fed intestine-specific ShpKO (IShpKO) mice displayed lower mucin 2 (MUC2)-positive cells, which suggests there is a reduced number of goblet cells in the ileum (188). Further, IShpKO mice, despite maintaining their suppression in ASBT levels, accumulated ileal bile acids when challenged with a CA diet (188). Intriguingly, organic solute transporter β (OSTβ) protein levels were elevated in the IShpKO ileum, even under basal conditions, highlighting the importance of SHP in regulating ileal bile acid transport.

Moreover, transcriptomic analysis in global ShpKO mice revealed that SHP and FGF15 are essential for the repression of NPC1-like intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1L1) (188). This suggests that intestinal SHP and FGF15 may coordinate to lower cholesterol transport and possibly regulate intestinal lipid and bile acid transporters independent of FXR signaling.

Liver X Receptor

LXR signaling regulates cholesterol homeostasis with oxysterols being its endogenous ligand. The two different isoforms of LXR exhibit differential expression profiles with LXRα expressed in the intestine and the liver while LXRβ is ubiquitously expressed (100). LXR activation is known to regulate reverse cholesterol transport pathways, apoptosis, and macrophage activity (193–196) in addition to regulating the Cyp7a1 gene, specifically in rodents (197). Further, LXRα activation is also associated with increasing sulphation of bile acids to promote their elimination, and hence may contribute toward modulating bile acid homeostasis (198). Additionally, LXRα can also be activated in vitro by a secondary bile acid, HDCA (105, 199–201). Although in vivo mouse and human data are lacking, acute gavage of HDCA in zebrafish larvae showed a decrease in transportation of absorbed lipids (202). Mice challenged with an HDCA diet had a significantly lower Srebp1c, Acc, Scd1, and Fasn mRNA expression, all of which are direct targets of LXR (203, 204). However, mice treated with an HDCA derivative showed no change in hepatic lipid levels nor any change in Lxrα transcript (205). These results reveal the need for more in vivo studies to concretely prove HDCA as an activator of LXRα.

Vitamin D Receptor

Although 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (25D) is the bona fide ligand of VDR, the secondary bile acid, LCA can also activate it (104). Depending on the ligand, VDR is linked to either calcium homeostasis with 25D or with bile acids homeostasis and metabolite clearance with LCA (206). Additionally, VDR activation both by 25D and LCA has been shown to regulate CYP3A expression alongside SULTs and ATP-binding cassette transporters in humans, rats, and mice (104, 06–13). In obesity, type 2 diabetes, and bariatric surgery, there has been increased focus on VDR and LCA because of their ability to modulate cholic acid-7-sulfate synthesis, which is linked to beneficial metabolic outcomes (214). Of note, VDR activation has also been shown to protect against liver fibrosis (215). Due to its high expression in the small and large intestine, the role of VDR in modulating gut microbiota and bile acid modification is a growing area of research (209). Along this line, recent studies revealed that VDR expression is increased in the duodenum of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Notably, gut dysbiosis and overgrowth of intestinal Clostridia cluster XIV bacteria, responsible for LCA production from CA and CDCA, can be associated with irritable bowel syndrome onset (216).

Pregnane X Receptor

Like VDR, PXR can be activated by the secondary bile acid LCA (118). The hydrophobic ligand pocket of PXR makes it a versatile NR that can bind a myriad of ligands (217). On ligand binding and activation, PXR heterodimerizes with RXRα and transcriptionally regulates phase I (Cyp1A, Cyp2b, Cyp2c, and Cyp3a families) II (Sult family, Ugt1a1), and III (Mdr1, Mrp2, and Oatp2) genes (118, 218, 219). These metabolic pathways are also useful in modulating bile acid levels. For example, PXR ligands (medicinal herb [Schisandra sphenanthera (WZ)], rifampicin, pregnenolone-16a-carbonitrile [PCN]) induce the transcription of CYP3A, which promotes hydroxylation and subsequent detoxification of bilirubin and LCA (66, 103, 19–21). PXR exhibits differential mechanisms and preferences of ligands between humans and mice (222) Human PXR is activated by rifampicin, whereas murine PXR is activated by PCN (222–226). Recent advances revealed that defects in regeneration and bile duct degeneration seen on deletion of YAP/TAZ in biliary epithelial cells (Yap/TazBEC-KO) could be mimicked by PXR activation. In fact, pharmacological activation of PXR in wild-type (WT) mice recapitulated the regenerative defects observed in Yap/TazBEC-KO that was attributed to PXR activation secondary to bile acid excess, (227). These studies highlight the role for PXR signaling in maintaining bile acid homeostasis (227, 228).

Bile Acid–Activated G Protein–Coupled Receptors

Bile acids not only autoregulate their concentrations but also control the homeostasis of glucose and lipids and thus overall energy metabolism (50). One way of coordinating such diverse regulation is by signaling through GPCRs. GPCRs are 7-transmembrane–containing receptors that convert to a transient high-affinity state on ligand binding. Classically, the activated G protein receptor exchanges GDP for GTP, which then allows for the dissociation of the Gα subunits and Gβγ dimers, allowing for downstream activation of effectors, such as the release of Gαs to increase 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate (cAMP) levels (229). TGR5 (230, 231), sphingosine-1-phosphate 2 (S1PR2) (232, 233), and recently mas-related GPCR X4 (MRGPRX4) (97, 117) are GPCRs that are activated by bile acids. Similar to NRs, bile acids have different binding affinity and activation strength depending on which bile acid can interact with these GPCRs (see Table 1). TGR5 and S1PR2 can be found in many bile acid–related tissues, while human MRGPRX4 and its mouse orthologs MRGPRA1 and MRGPRB2 are mainly found in sensory neurons and specialized immune cells (234) (Fig. 2).

Takeda G Protein–Coupled Receptor 5

The G protein–coupled bile acid receptor (GPBAR1) or TGR5 was discovered in 2002 to be activated by both conjugated and unconjugated primary bile acids such as TCA, UDCA, and TLCA albeit varying in efficacy (115, 5–7). Upon bile acid binding and activation, TGR5 can modulate many cellular functions by increasing cAMP concentrations to modulate glucose homeostasis through glucagon-like peptide 1 secretion (238) and promote energy metabolism (239). Typically, TGR5 couples with stimulatory G α protein (Gαs) but in cholangiocytes, TGR5 selectively couples to either G α protein (Gαi) or Gαs based on membrane location to modulate cell proliferation to varying degrees based on the bound bile acid (114, 115, 210).

The Tgr5KO mice are relatively normal and healthy under basal conditions (240) but they do exhibit reduced expression of Cyp7b1 and alteration in the composition of the bile acid pool (241–243). Further, Tgr5KO mice are more susceptible to cholestatic liver injury such as chronic bile duct ligation (CBDL) and display reduced regenerative ability in response to partial hepatectomy (244–246). However, when challenged with a CA-enriched diet, Tgr5KO mice displayed an increased mitogenic response both in hepatocytes and other nonparenchymal cells (246). Consistent with its proliferative role, TGR5 is highly overexpressed in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) and numerous CCA cell lines (244, 247). Studies on TGR5's role in bile acid homeostasis, cell proliferation, and overall health in a tissue-specific manner needs further evaluation.

Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 2

S1PR2 is another GPCR that interacts with either Gαi or Gαs in a cell type–specific manner. Unlike TGR5, S1PR2 is activated primarily by conjugated bile acids and is mainly expressed in hepatocytes. Nevertheless, S1PR2 and TGR5 are both highly expressed in intestinal epithelial cells (248, 249). There are overlapping and distinct signaling pathways that are altered by these two GPCRs. For instance, their activation by conjugated bile acids can result in the regulation of epidermal growth factor, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), insulin receptor (IR), extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2), protein kinase B (AKT), and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) (231, 233, 244, 0–3). Similar to TGR5, in CCA cell lines, S1PR2 overexpression led to increased proliferation, migration, and invasiveness (250).

The conflicting nature of S1pr2KO and Tgr5KO phenotypes suggests that despite GPCRs’ ability to be activated by various bile acids, the function of these receptors is quite different. For example, unlike Tgr5KO mice being susceptible, S1pr2KO mice exhibit protection from cholestatic liver injury indicated by lower serum and hepatic bile acid accumulation on CBDL as opposed to WT mice (194). Conversely, S1pr2KO mice were more susceptible to lipid and cholesterol accumulation in the liver when challenged with a high-fat diet (191). Further studies on S1PR2 will be essential in delineating its role in hepatic injury recovery and proliferation.

Mas-Related G Protein–Coupled Receptor X4

Pruritus, or itch during cholestasis, is common and is attributed to bile acids and bilirubin (254). Until recently, TGR5 was implicated in mediating acute cholestatic itch (175) and further studies showed that this receptor is deactivated in chronic cholestasis (255). These results indicated that other neuronally expressed GPCRs may also contribute to cholestatic itch. Accordingly, in 2019, MRGPRX4 was discovered as a novel receptor both for bile acid and bilirubin independently by two laboratories (97, 117) Meixiong et al (117) reported that MRGPRX4 is present in human sensory neurons and in dorsal root ganglion, is activated by pathological levels of bile acids, and demonstrated that humanized MRGPRX4 mice scratch more when injected with various bile acids (DCA, TDCA, UDCA, CDCA). Yu and colleagues (97) showed that bile acids can elicit an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and action potential in neuronal cells and determined DCA to be the most potent bile acid to activate MRGPRX4.

Additionally, bilirubin was also identified to promote pruritis via mouse MRGPRA1 and human MRGPRX4 (120). Notably, nateglinide, an MRGPRX4 agonist, was sufficient to induce itchiness in humans confirming this novel receptor can contribute to cholestatic pruritis (97). Conversely, the hydrophilic bile acid UDCA is typically used to alleviate cholestatic symptoms in patients, but does not always reduce itchiness (256). The underlying mechansim may be due to the alteration in composition and concentration of bile acids present in the body (97, 254, 257, 258). Although UDCA has been prescribed to alleviate pruritus in cholestatic pregnancy, there are contradictory data that question its benefit and hence UDCA usage must be reexamined (259).

Diet and Gut Microbiota and Their Influence in Bile Acid Composition

Diet directly influences the gut microbiota and bile acid pool. Microbiota can catabolize nutrients for energy and thrive or adjust depending on the diet, while the content of the diet (such as high- fat vs high- carbohydrates) may alter bile acid levels and gut microbiome profile (260–264). In addition, gut bacteria can modify and generate secondary bile acids that can circulate in the bloodstream to regulate glucose and lipid metabolism (265).

Studies in rats, guinea pigs, and dogs showed that more dietary protein and fat increased total bile acid excretion; in contrast, carbohydrates lowered total fecal bile acid excretion. Addition of soluble fiber will further enhanced bile acid excretion (261). Consistent with these studies, vegans displayed a lower amount of total fecal bile acid than people who eat meat, suggesting that a higher intake of animal protein and fats may lead to higher total fecal bile acid excretion (260). Thus, content of the diet plays a crucial role in regulating bile acid levels.

Diet-induced obesity is a causal factor that predisposes one to various metabolic diseases. Interestingly, metabolically unhealthy patients with a high body mass index exhibited a significantly increased percentage of 12-OH bile acids (DCA, GDCA, TLCA, TDCA, TCA) in contrast to non–12-OH bile acids (HCA, HDCA, GHDCA, UDCA, CDCA, GUDCA). Further, it was demonstrated that lower non–12-OH bile acid percentages correlated with obesity and were associated with a low abundance of Clostridium scindens. Reintroducing C.scindens increased non–12-OH bile acid concentrations in these mouse livers, demonstrating that dysregulation in bile acid levels and gut microbiome profile is linked to obesity (266). The Western-style high-fat high-sugar diet (HFHSD) can also lead to gut dysbiosis and metabolic diseases. Intriguingly, Cyp2a12/Cyp2c70 double KO (CDKO) mice, which have human-like bile acid composition, do not exhibit any significant difference in gut microbiome at the basal level. Intriguingly, HFHSD alleviated the liver injury usch as bile duct proliferation and lymphocyte infilteration seen in CDKO mice. HFHSD-induced increase in BA pool and fecal BA excretion in the WT but not in the CDKO animals; however, both genotypes showed similar gut dysbiosis. These results suggest that the diet rather than the bile acid pool change leads to gut dysbiosis (263).

Concluding Perspectives

Bile acids have piqued generations of researchers over the last 2 centuries, be it their structure, synthesis, breakdown, transport, or signaling. Despite the enormous understanding of bile acid biology, many lingering questions and gaps remain to be addressed. Concentrations of individual bile acids within the bile pool are essential; still, it is cumbersome to tease apart their hierarchy since a change in one of their concentrations alters the others. Nevertheless, enzyme kinetics and monitoring the bile acid pool over time can provide some insights. How does the bile acid pool change translate to the downstream receptor signaling via NRs and GPCRs? For instance, does excess CDCA and LCA result in simultaneous activation of FXR, VDR, and TGR5? How does LCA prioritize between the receptors since it is a potent agonist both for TGR5 and VDR? Is it tissue milieu, cell-specific, or simply the vicinity and availability of the receptors? Different bile acids display varied receptor binding affinities. But if the concentration of bile acids is not limiting, is the physiological outcome a combination of mechanisms orchestrated by multiple receptors, or is there a hierarchy? How does this change in diseased states, for instance, in cholestasis or in fatty liver disease? Tissue-specific receptor KOs will help delineate if other receptors compensate for the loss and how the other receptors respond when challenged with different bile acids. This will be a labor-intensive endeavor as different bile acids must be tested. Bile acid pool composition must be constantly monitored since the loss of these receptors alters the pool, thus making it a catch-22 situation. But finding such redundancy is pertinent for understanding bile acid signaling. For example, FXR is typically investigated as the primary target of bile acids, but its absence can be compensated for by TGR5 and vice versa (267), indicating crosstalk between the NRs and GPCRs. Therefore, careful consideration of the bile acid dose and potential receptor crosstalk needs to be included as a variable in the experimental designs and interpretation of the data. Finally, with all the new bile acids being identified, teasing out gut microbiota and bile acid interactions may quickly lead to a chicken-and-egg scenario. Although germ-free mice and SPF have been helpful, they inherently have an altered bile acid pool. Despite centuries of work, our understanding of the diverse roles of bile acids feels like the tip of the iceberg. However, one thing for sure is that these cholesterol metabolites have graduated from natural detergents to signaling molecules.

“All we know is still infinitely less than all that remains unknown.”—William Harvey

Financial Support

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant No. R01 DK113080 to S.A.), the American Cancer Society (No. ACS132640-RSG132315 to S.A.), and the Cancer Center at Illinois (CCIL planning grant 6741 and minority supplement for R.P.H.S.).

Abbreviations

- 25D

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- ASBT

apical sodium dependent bile acid transporter

- cAMP

3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate

- CA

cholic acid

- CCA

cholangiocarcinoma

- CDCA

chenodeoxycholic acid

- CYP7A1

P450 cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase

- DCA

deoxycholic acid

- FABP

fatty acid binding protein

- FGF15

fibroblast growth factor 15

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- HCA

hyocholic acid

- HDCA

hyodeoxycholic acid

- HFHSD

high-fat high-sugar diet

- KO

knockout

- LCA

lithocholic acid

- LXR

liver X receptor

- MCA

muricholic acid

- MRGPRX4

Mas-related G protein–coupled receptor X4

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- norUDCA

24-norursodeoxycholic acid

- NPC

Niemann-Pick C

- NR

nuclear receptor

- OCA

obeticholic acid

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- S1PR2

sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2

- SHP

small heterodimer partner

- SPF

specific-pathogen free

- TCA

taurocholic acid

- TGR5

Takeda G protein–coupled receptor 5

- UDCA

ursodeoxycholic acid

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- WT

wild-type

Contributor Information

James T Nguyen, Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA.

Ryan Philip Henry Shaw, Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA.

Sayeepriyadarshini Anakk, Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; Cancer Center at Illinois, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; Division of Nutritional Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the present study.

References

- 1. Russell DW. Fifty years of advances in bile acid synthesis and metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S120–S125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hofmann AF, Hagey LR. Key discoveries in bile acid chemistry and biology and their clinical applications: history of the last eight decades. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(8):1553–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perino A, Demagny H, Velazquez-Villegas L, Schoonjans K. Molecular physiology of bile acid signaling in health, disease, and aging. Physiol Rev. 2021;101(2):683–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boyer JL. Bile formation and secretion. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(3):1035–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dawson PA. Roles of ileal ASBT and OSTα-OSTβ in regulating bile acid signaling. Dig Dis. 2017;35(3):261–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neubauer E. Über die Cholagoge Wirkung der Dehydrocholsäure beim Menschen. Klin Wochenschr. 1924;3(20):883–883. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sarett LH. Partial synthesis of pregnene-4-triol-17(beta), 20(beta), 21-dione-3,11 and pregnene-4-diol-17(beta), 21-trione-3,11,20 monoacetate. J Biol Chem. 1946;162:601–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hillier SG. Diamonds are forever: the cortisone legacy. J Endocrinol. 2007;195(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Griffiths WJ, Sjövall J. Bile acids: analysis in biological fluids and tissues. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(1):23–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sjövall J. Fifty years with bile acids and steroids in health and disease. Lipids. 2004;39(8):703–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grundy SM, Hofmann AF, Davignon J, Ahrens EH. Human cholesterol synthesis is regulated by bile acids. J Clin Invest. 1966;45:1018–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Danzinger RG, Hofmann AF, Schoenfield LJ, Thistle JL. Dissolution of cholesterol gallstones by chenodeoxycholic acid. N Engl J Med. 1972;286(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Norman A, Grubb R. Hydrolysis of conjugated bile acids by Clostridia and enterococci; bile acids and steroids 25. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1955;36(6):537–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Norman A, Sjövall J. On the transformation and enterohepatic circulation of cholic acid in the rat. J Biol Chem. 1958;233(4):872–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Norman A, Sjövall J, Bak TA, Varde E, Westin G. Formation of lithocholic acid from chenodeoxycholic acid in the rat. Bile acids and steroids 103. Acta Chem Scand. 1960;14:1815–1818. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lindstedt S. The turnover of cholic acid in man: bile acids and steroids. Acta Physiol Scand. 1957;40(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Danielsson H, Sjövall J.. Bile acid metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 1975;44:233–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bell GD, Whitney B, Dowling HR. Gallstone dissolution in man using chenodeoxycholic acid. Lancet. 1972;300(7789):1213–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sugata F, Shimizu M. [Retrospective studies on gallstone disappearance (author's transl)]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1974;71(1):75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakagawa S. Dissolution of cholesterol gallstones by ursodeoxycholic acid. Lancet. 1977:310(8034):367–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Makino I, Tanaka H. From a choleretic to an immunomodulator: historical review of ursodeoxycholic acid as a medicament. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13(6):659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poupon R, Poupon R, Calmus Y, Chrétien Y, Ballet F, Darnis F. Is ursodeoxycholic acid an effective treatment for primary biliary cirrhosis? Lancet. 1987;329(8537):834–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindor KD, Dickson ER, Baldus WP, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(5):1284–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palma J, Reyes H, Ribalta J, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of cholestasis of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind study controlled with placebo. J Hepatol. 1997;27(6):1022–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wieland H. The chemistry of bile acids. Nobel Lect Chem. 1966;2:94-–102.. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guzmán HM, Sepúlveda M, Rosso N, San Martin A, Guzmán F, Guzmán HC. Incidence and risk factors for cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2019;29(7):2110–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poupon R. Ursodeoxycholic acid and bile-acid mimetics as therapeutic agents for cholestatic liver diseases: an overview of their mechanisms of action. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36(Suppl 1):S3–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sakiani S, Kleiner DE, Heller T, Koh C. Hepatic manifestations of cystic fibrosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23(2):263–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ruutu T, Juvonen E, Remberger M, et al. ; Nordic Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation . Improved survival with ursodeoxycholic acid prophylaxis in allogeneic stem cell transplantation: long-term follow-up of a randomized study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(1):135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL clinical practice guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J Hepatol. 2016;65(1):146–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hofmann AF, Zakko SF, Lira M, et al. Novel biotransformation and physiological properties of norursodeoxycholic acid in humans. Hepatology. 2005;42(6):1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yoon YB, Hagey LR, Hofmann AF, Gurantz D, Michelotti EL, Steinbagh JH. Effect of side-chain shortening on the physiologic properties of bile acids: hepatic transport and effect on biliary secretion of 23-nor-ursodeoxycholate in rodents. Gastroenterology. 1986;90(4):837–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fickert P, Wagner M, Marschall H, et al. 24-norUrsodeoxycholic acid is superior to ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2):465–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Beuers U, Hohenester S, de Buy Wenniger LJM, Kremer AE, Jansen PLM, Elferink RPJO. The biliary HCO(3)(−) umbrella: a unifying hypothesis on pathogenetic and therapeutic aspects of fibrosing cholangiopathies. Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cabrera D, Arab JP, Arrese M. UDCA, NorUDCA, and TUDCA in liver diseases: a review of their mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2019;256:237–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Halilbasic E, Steinacher D, Trauner M. Nor-ursodeoxycholic acid as a novel therapeutic approach for cholestatic and metabolic liver diseases. Dig Dis. 2017;35(3):288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Trauner M, Halilbasic E, Claudel T, et al. Potential of ursodeoxycholic acid in cholestatic and metabolic disorders. Dig Dis. 2015;33(3):433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fickert P, Hirschfield GM, Denk G, et al. Norursodeoxycholic acid improves cholestasis in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67(3):549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chazouillères O. 24-Norursodeoxycholic acid in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a new “urso saga” on the horizon? J Hepatol. 2017;67(3):446–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Steinacher D, Claudel T, Trauner M. Therapeutic mechanisms of bile acids and nor-ursodeoxycholic acid in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis. 2017;35(3):282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Windaus A. Constitution of sterols and their connection with other substances occurring in nature. Nobel Lect Chem. 1941:105–121. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bernal JD. Crystal structures of vitamin D and related compounds. Nature. 1932;129(3251):277–278. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosenheim O, King H. The chemistry of the sterols, bile acids, and other cyclic constituents of natural fats and oils. Annu Rev Biochem. 1934;3(1):87–110. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bloch K, Berg BN, Rittenberg D. The biological conversion of cholesterol to cholic acid. J Biol Chem. 1943;149(2):511–517. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Armstrong MJ, Carey MC. The hydrophobic-hydrophilic balance of bile salts. Inverse correlation between reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatographic mobilities and micellar cholesterol-solubilizing capacities. J Lipid Res 1982;23(1):70–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reis S, Moutinho CG, Matos C, de Castro B, Gameiro P, Lima JLFC. Noninvasive methods to determine the critical micelle concentration of some bile acid salts. Anal Biochem. 2004;334(1):117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Russell DW. The enzymes, regulation, and genetics of bile acid synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:137–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Myant NB, Mitropoulos KA. Cholesterol 7α hydroxylase. J Lipid Res. 1977;18(2):135–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schwarz M, Lund EG, Setchell KDR, et al. Disruption of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene in mice. II. Bile acid deficiency is overcome by induction of oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(30):18024–18031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li T, Chiang JYL. Bile acid signaling in metabolic disease and drug therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2014;66(4):948–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Duane WC, Javitt NB. 27-Hydroxycholesterol: production rates in normal human subjects. J Lipid Res. 1999;40(7):1194–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schwarz M, Russell DW, Dietschy JM, Turley SD. Alternate pathways of bile acid synthesis in the cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase knockout mouse are not upregulated by either cholesterol or cholestyramine feeding. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(10):1594–1603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Takahashi S, Fukami T, Masuo Y, et al. Cyp2c70 is responsible for the species difference in bile acid metabolism between mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(12):2130–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Straniero S, Laskar A, Savva C, Härdfeldt J, Angelin B, Rudling M. Of mice and men: murine bile acids explain species differences in the regulation of bile acid and cholesterol metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2020;61(4):480–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Falany CN, Johnson MR, Barnes S, Diasio RB. Glycine and taurine conjugation of bile acids by a single enzyme. Molecular cloning and expression of human liver bile acid CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(30):19375–19379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hepner GW, Hofmann AF, Thomas PJ. Metabolism of steroid and amino acid moieties of conjugated bile acids in man: II. Glycine-conjugated dihydroxy bile acids. Gastroenterology. 1972;51(7):1898–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hepner GW, Sturman JA, Hofmann AF. Metabolism of steroid and amino acid moieties of conjugated bile acids in man. III. Cholyltaurine (taurocholic acid). Gastroenterology. 1973;52(2):433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alnouti Y, Csanaky IL, Klaassen CD. Quantitative-profiling of bile acids and their conjugates in mouse liver, bile, plasma, and urine using LC-MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;873(2):209–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thakare R, Alamoudi JA, Gautam N, Rodrigues AD, Alnouti Y. Species differences in bile acids I. Plasma and urine bile acid composition. J Appl Toxicol. 2018;38(10):1323–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ashby K, Navarro Almario EE, Tong W, Borlak J, Mehta R, Chen M. Review article: therapeutic bile acids and the risks for hepatotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(12):1623–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li J, Dawson PA. Animal models to study bile acid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865(5):895–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. de Boer JF, Bloks VW, Verkade E, Heiner-Fokkema MR, Kuipers F. New insights in the multiple roles of bile acids and their signaling pathways in metabolic control. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2018;29(3):194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res. 2006;47(2):241–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ridlon JM, Harris SC, Bhowmik S, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB. Consequences of bile salt biotransformations by intestinal bacteria. Gut Microbes. 2016;7(1):22–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Van Nieuwerk CMJ, Groen AK, Ottenhoff R, et al. The role of bile salt composition in liver pathology of mdr2 (-/-) mice: differences between males and females. J Hepatol. 1997;26(1):138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Honda A, Miyazaki T, Iwamoto J, et al. Regulation of bile acid metabolism in mouse models with hydrophobic bile acid composition. J Lipid Res. 2020;61(1):54–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Enright EF, Griffin BT, Gahan CGM, Joyce SA. Microbiome-mediated bile acid modification: role in intestinal drug absorption and metabolism. Pharmacol Res. 2018;133:170–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wahlström A, Sayin SI, Marschall HU, Bäckhed F. Intestinal crosstalk between bile acids and microbiota and its impact on host metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;24(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Winston JA, Theriot CM. Diversification of host bile acids by members of the gut microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2020;11(2):158–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cai J, Sun L, Gonzalez FJ. Gut microbiota-derived bile acids in intestinal immunity, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30(3):289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang L, Xie C, Nichols RG, et al. Farnesoid X receptor signaling shapes the gut microbiota and controls hepatic lipid metabolism. mSystems. 2016;1(5):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wahlström A, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Ståhlman M, Khan MT, Bäckhed F, Marschall HU. Induction of farnesoid X receptor signaling in germ-free mice colonized with a human microbiota. J Lipid Res. 2017;58(2):412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Islam KBMS, Fukiya S, Hagio M, et al. Bile acid is a host factor that regulates the composition of the cecal microbiota in rats. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1773–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB, Bajaj JS. Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30(3):332–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Just S, Mondot S, Ecker J, et al. The gut microbiota drives the impact of bile acids and fat source in diet on mouse metabolism. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Begley M, Gahan CGM, Hill C. The interaction between bacteria and bile. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29(4):625–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Alvelius G, Hjalmarson O, Griffiths WJ, Björkhem I, Sjövall J. Identification of unusual 7-oxygenated bile acid sulfates in a patient with Niemann-Pick disease, type C. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(10):1571–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mazzacuva F, Mills P, Mills K, et al. Identification of novel bile acids as biomarkers for the early diagnosis of Niemann-Pick C disease. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:1651–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Devlin AS, Fischbach MA. A biosynthetic pathway for a prominent class of microbiota-derived bile acids. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(9):685–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Staley C, Weingarden AR, Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ. Interaction of gut microbiota with bile acid metabolism and its influence on disease states. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101(1):47–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. He X, Gao J, Peng L, et al. Bacterial O-GlcNAcase genes abundance decreases in ulcerative colitis patients and its administration ameliorates colitis in mice. Gut. 2021;70(10):1872–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shonsey EM, Sfakianos M, Johnson M, et al. Bile acid coenzyme A: amino acid N-acyltransferase in the amino acid conjugation of bile acids. Methods Enzymol. 2005;400(05):374–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shonsey EM, Wheeler J, Johnson M, et al. Synthesis of bile acid coenzyme A thioesters in the amino acid conjugation of bile acids. Methods Enzymol. 2005;400(05):360–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sfakianos MK, Wilson L, Sakalian M, Falany CN, Barnes S. Conserved residues in the putative catalytic triad of human bile acid coenzyme A:amino acid N-acyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(49):47270–47275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kirilenko BM, Hagey LR, Barnes S, Falany CN, Hiller M. Evolutionary analysis of bile acid-conjugating enzymes reveals a complex duplication and reciprocal loss history. Genome Biol Evol. 2019;11(11):3256–3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Quinn RA, Melnik A V, Vrbanac A, et al. Global chemical effects of the microbiome include new bile-acid conjugations. Nature. 2020;579(7797):123–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lee G, Lee H, Hong J, Lee SH, Jung BH. Quantitative profiling of bile acids in rat bile using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography–orbitrap mass spectrometry: alteration of the bile acid composition with aging. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2016;1031:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fu ZD, Csanaky IL, Klaassen CD. Gender-divergent profile of bile acid homeostasis during aging of mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Frommherz L, Bub A, Hummel E, et al. Age-related changes of plasma bile acid concentrations in healthy adults-results from the cross-sectional KarMeN study. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Molinero N, Ruiz L, Sánchez B, Margolles A, Delgado S. Intestinal bacteria interplay with bile and cholesterol metabolism: implications on host physiology. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. van Best N, Rolle-Kampczyk U, Schaap FG, et al. Bile acids drive the newborn's gut microbiota maturation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wu L, Zeng T, Zinellu A, Rubino S, Kelvin DJ, Carru C. A cross-sectional study of compositional and functional profiles of gut microbiota in Sardinian centenarians. mSystems. 2019;4(4):e00325-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sato Y, Atarashi K, Plichta DR, et al. Novel bile acid biosynthetic pathways are enriched in the microbiome of centenarians. Nature. 2021;599(7885):458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rimal B, Patterson AD. Role of bile acids and gut bacteria in healthy ageing of centenarians. Nature. 2021;599(7885):380–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Nishimura M, Naito S, Yokoi T. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiles of human nuclear receptor subfamilies. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2004;19(2):135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bookout AL, Jeong Y, Downes M, Yu RT, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Anatomical profiling of nuclear receptor expression reveals a hierarchical transcriptional network. Cell. 2006;126(4):789–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Yu H, Zhao T, Liu S, et al. Mrgprx4 is a novel bile acid receptor in cholestatic itch. Elife. 2019;8:e48431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wang L, Nanayakkara G, Yang Q, et al. A comprehensive data mining study shows that most nuclear receptors act as newly proposed homeostasis-associated molecular pattern receptors. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mazaira GI, Zgajnar NR, Lotufo CM, et al. The nuclear receptor field: a historical overview and future challenges. Nucl Recept Res. 2018;5:101320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Seol W, Choi HS, Moore DD. Isolation of proteins that interact specifically with the retinoid X receptor: two novel orphan receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9(1):72–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Forman BM, Goode E, Chen J, et al. Identification of a nuclear receptor that is activated by farnesol metabolites. Cell. 1995;81:687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell. 1995;83(6):841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Xie W, Radominska-Pandya A, Shi Y, et al. An essential role for nuclear receptors SXR/PXR in detoxification of cholestatic bile acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(6):3375–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Makishima M, Lu TT, Xie W, et al. Vitamin D receptor as an intestinal bile acid sensor. Science. 2002;296(5571):1313–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Song C, Hiipakka RA, Liao S. Selective activation of liver X receptor alpha by 6alpha-hydroxy bile acids and analogs. Steroids. 2000;65(8):423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Parks DJ, Blanchard SG, Bledsoe RK, et al. Bile acids: natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science. 1999;284(5418):1365- 1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Makishima M, Okamoto AY, Repa JJ, et al. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science. 1999;284(5418):1362–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Wang H, Chen J, Hollister K, Sowers LC, Forman BM. Endogenous bile acids are ligands for the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR. Mol Cell. 1999;3:543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Lew JL, Zhao A, Yu J, et al. The farnesoid X receptor controls gene expression in a ligand- and promoter-selective fashion. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(10):8856–8861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Song P, Rockwell CE, Cui JY, Klaassen CD. Individual bile acids have differential effects on bile acid signaling in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;283(1):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Nishimaki-Mogami T, Une M, Fujino T, et al. Identification of intermediates in the bile acid synthetic pathway as ligands for the farnesoid X receptor. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(8):1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Liu J, Lu H, Lu YF, et al. Potency of individual bile acids to regulate bile acid synthesis and transport genes in primary human hepatocyte cultures. Toxicol Sci. 2014;141(2):538–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ishizawa M, Akagi D, Makishima M. Lithocholic acid is a vitamin D receptor ligand that acts preferentially in the ileum. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7):1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Maruyama T, Miyamoto Y, Nakamura T, et al. Identification of membrane-type receptor for bile acids (M-BAR). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298(5):714–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Kawamata Y, Fujii R, Hosoya M, et al. A G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(11):9435–9440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Studer E, Zhou X, Zhao R, et al. Conjugated bile acids activate the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 in primary rodent hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2012;55(1):267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Meixiong J, Vasavda C, Snyder SH, Dong X. Mrgprx4 is a G protein-coupled receptor activated by bile acids that may contribute to cholestatic pruritus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(21):10525–10530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Staudinger JL, Goodwin B, Jones SA, et al. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(6):3369–3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Zhou J, Liu M, Zhai Y, Xie W. The antiapoptotic role of pregnane X receptor in human colon cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(4):868–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Meixiong J, Vasavda C, Green D, et al. Identification of a bilirubin receptor that may mediate a component of cholestatic itch. Elife. 2019;8:e44116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Flegel C, Schöbel N, Altmüller J, et al. RNA-Seq analysis of human trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia with a focus on chemoreceptors. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Van Erpecum KJ, Wang DQH, Moschetta A, et al. Gallbladder histopathology during murine gallstone formation: Relation to motility and concentrating function. J Lipid Res. 2006;47(1):32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Chignard N, Mergey M, Barbu V, et al. VPAC1 expression is regulated by FXR agonists in the human gallbladder epithelium. Hepatology. 2005;42(3):549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Prestin K, Olbert M, Hussner J, et al. Modulation of expression of the nuclear receptor NR0B2 (small heterodimer partner l) and its impact on proliferation of renal carcinoma cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4867–4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Zhu R, Tu Y, Chang J, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor gene NR0B2 is a favorite prognosis factor modulated by multiple cellular signal pathways in human liver cancers. Front Oncol. 2021;11:691199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Oksvold P, et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(2):397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. NR1H2 Transcriptomics Data—The Human Protein Atlas . Accessed July 26, 2022.https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000131408-NR1H2/summary/rna

- 128. NR1H3 Transcriptomics Data—The Human Protein Atlas . Accessed July 26, 2022. https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000025434-NR1H3/summary/rna

- 129. Gascon-Barré M, Demers C, Mirshahi A, Néron S, Zalzal S, Nanci A. The normal liver harbors the vitamin D nuclear receptor in nonparenchymal and biliary epithelial cells. Hepatology. 2003;37(5):1034–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Seubwai W, Wongkham C, Puapairoj A, Khuntikeo N, Wongkham S. Overexpression of vitamin D receptor indicates a good prognosis for cholangiocarcinoma: implications for therapeutics. Cancer. 2007;109(12):2497–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Keitel V, Ullmer C, Häussinger D. The membrane-bound bile acid receptor TGR5 (gpbar-1) is localized in the primary cilium of cholangiocytes. Biol Chem. 2010;391(7):785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]