Abstract

Neutralizing antibodies are known to have a crucial role in protecting against SARS-CoV-2 infection and have been suggested to be a useful correlate of protection for vaccine clinical trials and for population-level surveys. In addition to neutralizing virus directly, antibodies can also engage immune effectors through their Fc domains, including Fc receptor-expressing immune cells and complement. The outcome of these interactions depends on a range of factors, including antibody isotype–Fc receptor combinations, Fc receptor-bearing cell types and antibody post-translational modifications. A growing body of evidence has shown roles for these Fc-dependent antibody effector functions in determining the outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, measuring these functions is more complicated than assays that measure antibody binding and virus neutralization. Here, we examine recent data illuminating the roles of Fc-dependent antibody effector functions in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and we discuss the implications of these data for the development of next-generation SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapeutics.

Subject terms: Immunization, SARS-CoV-2, Antibodies

In addition to antibody-mediated neutralization, Fc-dependent effector functions of antibodies directed to SARS-CoV-2 are emerging as an important factor in determining the outcome of infection. This Review highlights the current state of the field and discusses remaining uncertainties regarding Fc-dependent, non-neutralizing functions of antibodies.

Introduction

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has resulted in more than 400 million infections and more than 6 million deaths globally1. Initial hopes of developing herd immunity to the virus through infection and/or vaccination have been challenged by the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VoCs)2. Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which is the primary antigenic target in most approved COVID-19 vaccines, have reduced the efficacy of neutralizing antibodies in serum from vaccinated individuals and from those who were infected with earlier viral variants3,4. Most studies evaluating correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 have focused on spike-binding or neutralizing antibody titres in patient serum5,6. Neutralizing antibodies correlate well with protection against infection, but, in addition, non-neutralizing antibodies and T cells are likely to have roles in mitigating severe disease and resolving infection through ancillary immunological mechanisms7,8. However, the relative contributions of neutralizing antibodies, non-neutralizing antibodies and T cells in modulating infection severity are difficult to deconvolute in vivo and remain poorly resolved at present. Several reductionist models investigating the protective mechanisms of passively transferred monoclonal antibodies have reported an important role for non-neutralizing (crystallizable fragment (Fc)-dependent) effector functions in mediating protection. Yet, trials of convalescent plasma therapy to treat COVID-19 in humans have had mixed results, with many reporting no benefit, which suggests that if or when non-neutralizing functions of antibodies are capable of mediating protection is complex and context dependent9. The variable outcomes of these studies are due, at least in part, to study design elements including the nature of the patient population, timing of intervention and identity of SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating during the study period. Nevertheless, these data raise questions about the relevance of non-neutralizing antibody effector functions in protection against COVID-19, which are discussed in detail in this Review.

Upon exposure to SARS-CoV-2, B cells that recognize viral antigens are activated, transit to germinal centres, undergo class-switch recombination and progress through iterative rounds of somatic hypermutation10–12. The end result of this process is the selection of B cell clones producing high-affinity antibodies. Neutralizing antibodies block SARS-CoV-2 from infecting cells by preventing binding to host cells and/or the conformational changes required to mediate fusion with host cell membranes, and they are therefore essential for mediating sterilizing immunity against initial infection13. Nevertheless, non-neutralizing antibodies that bind to SARS-CoV-2 epitopes or antigens that do not prevent infection of cells can mediate protection from disease by activating immune effector cells through interactions between the immunoglobulin Fc region and Fc receptors (FcRs), resulting in the clearance of virus and/or of infected cells13. Whereas neutralizing antibodies are theoretically able to both mediate neutralization and induce Fc-dependent effector functions, non-neutralizing antibodies are only able to mediate protection via Fc-mediated mechanisms. Here, we review recent evidence supporting a role for antibodies with Fc-dependent effector functions (of which neutralizing antibodies are a subset) in determining the outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Fc–Fc receptor interactions

Whereas the antigen-binding fragment (Fab) region of antibodies directly binds to antigen, the Fc region determines the antibody isotype and shapes FcR interactions14,15. The five major antibody isotypes — IgM, IgD, IgG, IgE and IgA — are characterized by distinct Fc regions. Although there are many similarities in the structure and function of human and mouse antibodies and FcRs, there are also several important biological differences that distinguish the two species, including Fc–FcR binding affinities, cell-type expression patterns of FcRs and functions of Fc–FcR interactions16 (Table 1). These species-specific differences must therefore be considered in studies of Fc-dependent effector functions in vivo in animal models (Box 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of human and mouse Fc receptors

| Fc receptor | Function | ITAM, ITIM or ITAMi | Binding affinity for antibody isotypesa | Cell type-specific expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | ||||

| FcμR | Endocytosis | None | IgM (+++) | B cells; subpopulations of T cells and NK cells |

| Fcα/μR | Endocytosis | None | IgM (+++), IgA (+++) | Subpopulations of B cells and DCs |

| FcαRI | Cell activation or inhibition | ITAM or ITAMi | IgA (++) | Neutrophils and eosinophils; subpopulations of monocytes/macrophages and DCs |

| FcεRI | Cell activation | ITAM | IgE (+++) | Basophils, mast cells and platelets; subpopulations of monocytes/macrophages, DCs and eosinophils |

| FcεRII | IgE regulation | None | IgE (++) | B cells, eosinophils and platelets; inducible expression on monocytes/macrophages and DCs |

| FcγRI | Cell activation | ITAM | IgG1 (+++), IgG3 (+++), IgG4 (+++) | Monocytes/macrophages; inducible expression on neutrophils and mast cells |

| FcγRIIA | Cell activation or inhibition | ITAM or ITAMi | IgG1 (++), IgG2 (++), IgG3 (++), IgG4 (++) | Monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, DCs, basophils, mast cells, eosinophils and platelets |

| FcγRIIB | Cell inhibition | ITIM | IgG1 (+), IgG2 (+), IgG3 (++), IgG4 (++) | B cells, DCs and basophils; majority of monocytes/macrophages (except alveolar macrophages); subpopulations of neutrophils |

| FcγRIICb | Cell activation | ITAM | IgG1 (+), IgG2 (+), IgG3 (++), IgG4 (++) | NK cells |

| FcγRIIIA | Cell activation or inhibition | ITAM or ITAMi | IgG1 (++), IgG2 (+), IgG3 (+++), IgG4 (++) | NK cells and monocytes/macrophages; uncertain expression on neutrophils |

| FcγRIIIB | Cell activation or decoy receptor | None | IgG1 (++), IgG3 (++) | Neutrophils; subpopulations of basophils |

| Mouse | ||||

| FcμR | Endocytosis | None | IgM (+++) | B cells |

| Fcα/μR | Endocytosis | None | IgM (+++), IgA (+++) | B cells; subpopulations of DCs |

| FcεRI | Cell activation | ITAM | IgE (+++) | Basophils and mast cells; inducible expression on neutrophils and DCs |

| FcεRII | IgE regulation | None | IgE (+++) | B cells; subpopulations of DCs |

| FcγRI | Cell activation | ITAM | IgG2a (+++), IgG2b (++) | Neutrophils; subpopulations of monocytes/macrophages and DCs |

| FcγRIIB | Cell inhibition | ITIM | IgG1 (++), IgG2a (++), IgG2b (++), IgE (+) | B cells, monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, DCs, basophils, mast cells and eosinophils |

| FcγRIII | Cell activation or inhibition | ITAM or ITAMi | IgG1 (++), IgG2a (++), IgG2b (++), IgE (+) | NK cells, monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, DCs, basophils, mast cells and eosinophils |

| FcγRIV | Cell activation | ITAM | IgG2a (+++), IgG2b (+++), IgE (++) | Monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils and DCs |

DC, dendritic cell; Fc, crystallizable fragment; FcR, Fc receptor; ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif; ITAMi, inhibitory ITAM; ITIM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif; NK, natural killer. aMeasured in terms of the association constant (Ka): +++, >1 × 107 M−1; ++, 1 × 105–1 × 107 M−1; +, <1 × 105 M−1. bEncoded by a pseudogene that is only expressed in a fraction of the human population owing to allelic polymorphism.

IgG is the most abundant antibody isotype in human serum, with four subtypes that differ in relative abundance, hinge length and flexibility17. Differences in the functional characteristics of the IgG subclasses are partly explained by their different affinities for FcRs and by the distribution of those FcRs on different immune cell populations14,18. The characteristics of human FcRs for IgG (FcγRs) have been extensively reviewed16. In brief, the immune cell response is mediated by four activating receptors — FcγRI, FcγRIIA, FcγRIIC (encoded by a pseudogene that is expressed only in select individuals owing to allelic polymorphism) and FcγRIIIA — that signal through intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs, and one inhibitory receptor (FcγRIIB) that signals through an intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif. FcγRIIIB is expressed on the surface of some granulocytes and may function to trap IgG-containing immune complexes without leading to cell activation19,20. In addition to antibody isotype, the location and geometry of the antibody-binding epitope, stoichiometry of the antibody to antigen and affinity of the antibody for both its antigen and its cognate FcR are all crucial determinants of immune effector cell activation21,22.

IgA is the most abundant antibody isotype on mucosal surfaces and can form dimers and higher-order multimers linked by a J (joining) chain23,24. In the mucosa, IgA exists primarily in a dimeric form associated with a secretory component. IgA1 is the predominant subtype in serum, whereas IgA1 and IgA2 are present at more similar levels in the mucosa24. The classical FcR for IgA, FcαRI, is expressed on myeloid cells including neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes, macrophages and some dendritic cells16,25. Monomeric, dimeric and secretory IgA all bind to FcαRI, albeit with different affinities25,26. IgA-containing immune complexes have the greatest affinity for FcαRI, followed by monomeric IgA and dimeric IgA; secretory IgA requires the accessory molecule MAC1 to efficiently bind to FcαRI26. FcαRI is unique among the FcRs in that it can mediate both activating and inhibitory signalling. Crosslinking of FcαRI by IgA-containing immune complexes, resulting in sustained receptor aggregation, induces potent activating signalling through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs, whereas FcαRI binding by monomeric IgA, resulting in low-valency interactions and unsustained receptor aggregation, induces inhibitory signalling27.

Box 1 Evaluating Fc-dependent antibody effector functions in animal models of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Animal models of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection have been instrumental for understanding viral pathogenesis, transmission and immune responses, and for assessing the preclinical efficacy of candidate vaccines and antiviral therapeutics185. Various animal models, including mice, hamsters, ferrets and non-human primates, have been used to study particular aspects of SARS-CoV-2 infection185. However, in addition to differences in their disease sensitivity and susceptibility, these animal models also have differences in antibody biology (Table 1). Therefore, it is imperative to consider not only differences in disease pathogenesis but also immunological differences when choosing the most suitable model.

Many mouse models of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) use transgenic mice expressing human ACE2 or a mouse-adapted strain of SARS-CoV-2 (ref. 186). Mouse models have practical advantages, as mice are small and relatively inexpensive. They have been widely used to study fundamental aspects of crystallizable fragment (Fc)-dependent antibody responses as mouse Fc receptors (FcRs) cross-react with human antibodies (although with different affinities), facilitating passive-transfer studies187. However, it is important to consider differences in Fc–FcR interactions between humans and mice, particularly when interpreting data from mouse mechanistic studies. For example, the mouse orthologue of human FcγRIIA, FcγRIII, lacks the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif found in FcγRIIA (instead, it pairs with the FcR γ-chain, which contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif), and, unlike its human counterpart, it is expressed by natural killer cells19,20. In addition, mice lack FcαRI and instead probably compensate with Fcα/μR188. Therefore, IgA-mediated Fc-dependent effector functions in humans are not completely recapitulated in mice. Hamster models of COVID-19 share many of the advantages afforded by mice and can be used to study viral transmission189. However, the toolbox of immunological reagents compatible with hamsters is very limited, making studies of Fc-dependent antibody effector functions difficult. Like humans, rhesus macaques express four IgG subclasses, although there is less structural and functional diversity between these primate subclasses than between human IgG subclasses190. However, use of non-human primate models requires highly specialized facilities, may be ethically challenging and can be cost-preclusive. Therefore, knowledge of species-specific antibody and FcR biology must be considered when interpreting data pertaining to the role of antibodies in animal models of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Fc-dependent effector functions

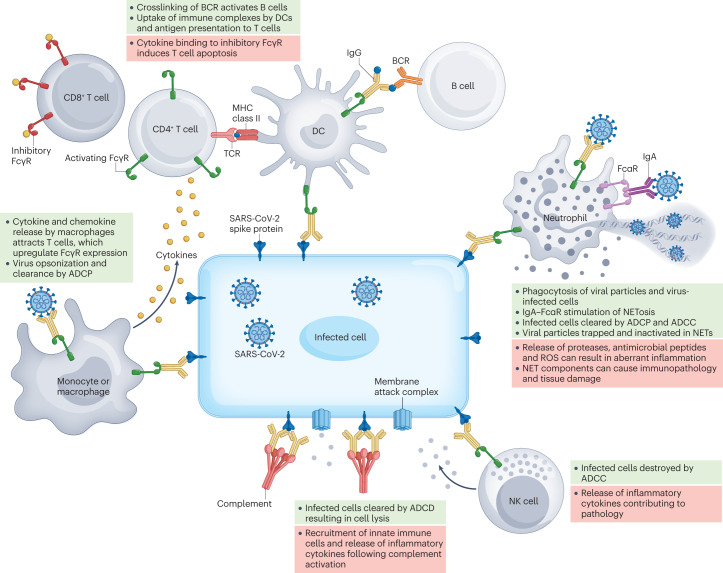

Immune complexes can be recognized by FcRs expressed on the surface of immune cells or bound by complement proteins (known as complement fixation) and mediate antimicrobial functions independently of neutralization. The outcome of these interactions depends on the isotype of the antibody, the protein or receptor to which the immune complex binds and the cell types on which the receptor is expressed. Possible outcomes include (but are not limited to) antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), antibody-dependent complement deposition (ADCD), antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), the production of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs; known as NETosis), modulation of T cell responses, immobilization of antigen on follicular dendritic cells, plasma cell survival and platelet activation (Table 2 and Fig. 1). In the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection, whether these Fc-dependent effector functions are protective or pathogenic is highly context dependent, as discussed below.

Table 2.

In vitro assays used to assess Fc-dependent antibody effector functions

| Assay type | Function assessed | Biochemical technique | Assay characteristics | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding assays | Antibody–FcR binding | Surface plasmon resonance | FcRs are immobilized on a biosensor and antibody binding is measured | 173,174 |

| ELISA | Recombinant FcRs are coated onto plates and antibodies are serially diluted to measure binding | 174 | ||

| Flow cytometry/FACS | Fluorescent antibodies are incubated with cells expressing FcRs. Median fluorescence intensity is measured to assess antibody binding | 174 | ||

| Fc-array with microspheres | Antigen-coated microspheres are incubated with serum. Microsphere–antibody complexes are subsequently incubated with fluorescent FcRs to assess median fluorescence intensity | 175 | ||

| Reporter-based assays | FcR-mediated transcriptional activation | ADCC and ADCP reporter bioassays | Engagement of FcR on effector cells activates intracellular signalling resulting in transcriptional activation of reporter gene expression | 176 |

| Functional assays | ADCC | Fluorescence reduction | Effector cell killing of fluorescent target cells results in a reduction in the size of the target cell population as measured by flow cytometry | 177 |

| Rapid fluorescent ADCC | Target cells are dual-stained with CFSE (viability) and PKH-26 (membrane dye). Incubation with effector cells results in target cell killing, as measured by the CFSE-negative population within the PKH-26-positive gate as measured by flow cytometry | 173,178 | ||

| Chromium release assay | Target cells are labelled with 51Cr and co-incubated with effector cells. 51Cr is released into the supernatant upon cell killing and radioactivity is measured | 179 | ||

| Effector cell activation | Target cells are co-incubated with effector cells. Flow cytometry is used to assess the percentage of effector cells positive for IFNγ, CCL4 and CD107a | 173,180 | ||

| ADCP | Fluorescence uptake | Uptake of antigen-coated beads by effector cells is assessed by flow cytometry. Both median fluorescence intensity and the percentage of bead-positive effector cells can be measured | 180 | |

| Fluorescent dye-labelled target cells are co-incubated with effector cells. Flow cytometry is used to assess the percentage of fluorescent dye-positive effector cells | 181 | |||

| ADCD | Bead-based assays | Antibodies are incubated with antigen-coated beads and subsequently incubated with complement. C3 deposition on beads can then be assessed as a measure of median fluorescence intensity | 182 | |

| Virus-based assays | Virions are incubated with complement, resulting in viral membrane disruption. Viral proteins are conjugated to streptavidin-coated beads and fluorescence intensity is determined by flow cytometry | 183 | ||

| Live/dead staining | Antigen-expressing target cells are incubated with serum and cells are stained with a viability marker to assess membrane integrity. Flow cytometry is used to measure the magnitude of cell killing | 183 | ||

| Antibody-dependent cell-mediated virus inhibition | ELISA | Infected target cells are incubated with antibodies and effector cells. An ELISA is performed on the supernatant to measure viral antigen | 174,184 |

ADCC, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; ADCD, antibody-dependent complement deposition; ADCP, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis; CCL4, CC-chemokine ligand 4; CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; 51Cr, chromium-51; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; Fc, crystallizable fragment; FcR, Fc receptor; IFNγ, interferon-γ; PKH-26, Paul Karl Horan 26.

Fig. 1. Fc-dependent antibody effector functions contribute to protection from and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Non-neutralizing antibodies can engage crystallizable fragment (Fc) receptors (FcRs) on multiple types of immune cell, including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), neutrophils and natural killer (NK) cells, to stimulate effector functions that influence the outcome of infection. Antibodies that bind to the spike protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can also mediate complement fixation. Fc-dependent antibody responses tend to have antiviral functions that mediate disease resolution when properly regulated (green boxes) but may contribute to immunopathology and exacerbate disease when dysregulated (red boxes). ADCC, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; ADCD, antibody-dependent complement deposition; ADCP, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis; BCR, B cell receptor; NET, neutrophil extracellular trap; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TCR, T cell receptor.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

The rapid recognition and elimination of infected cells is paramount to control and clearance of viral infections. Classically, IgG-containing immune complexes, such as those formed by IgG binding to spike protein on the surface of infected cells, crosslink FcγRIII on natural killer (NK) cells to elicit ADCC, but neutrophils and macrophages are also capable of comparable cytotoxic functions28. Clustering of immune complex-bound FcRs on effector cells results in the creation of an immune synapse, leading to the release of perforin and granzymes from these effector cells followed by the apoptosis of infected cells29.

In animal models of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the ability to induce Fc-dependent effector functions was essential for the efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy in mice and hamsters30,31. However, this requirement is probably dependent on the inherent neutralization potency and titre of the antibody. If virus is effectively neutralized, the requirement for Fc-dependent effector functions is often reduced32. Following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans, serum neutralizing antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and its receptor binding domain (RBD) also elicit ADCC, and when convalescent individuals were given one dose of the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2, antibodies that elicit ADCC were strongly increased and remained high for 16 weeks31,33 but were not further boosted by a second vaccine dose34,35. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination induce antibodies with Fc-dependent effector function (of which neutralizing antibodies are only a subset) that persist long term and have been shown to contribute to disease resolution in animal models.

Antibody-dependent complement deposition

Complement is a highly conserved component of the immune system that functions by opsonizing pathogens and directly lysing infected cells through formation of the membrane attack complex36. Nearly all innate immune cells express complement receptors, and ADCD has been reported for antibodies capable of binding to cells infected with influenza A virus (IAV) or West Nile virus, although it is unclear the extent to which this activity contributes to protection in vivo37–39. However, higher levels of activation of complement and coagulation cascades were observed in patients with severe COVID-19 than in those infected with seasonal IAV or hospitalized for other non-COVID-19 causes of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation40–42, which suggests that ADCD can also mediate pathology. Indeed, in mouse models of Betacoronavirus infection, immunopathology caused by complement activation was ameliorated by genetic knockout of the gene encoding C3, by blocking antibodies to C5a receptor (also known as CD88) or by pharmacological intervention43–45. Stringent regulation of complement activation is therefore required during SARS-CoV-2 infection as increased circulating levels of soluble complement factors such as C3a and C5a are associated with severe COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, endotheliitis, coagulopathy and death in humans44,46–49. Notably, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein interferes with the function of factor H and thus activates the alternative complement pathway, and the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 directly activates the lectin pathway through MASP2 (refs 50–52). More than 90% of critically ill patients with COVID-19 have autoreactive IgM that can bind to diverse targets across distal organs and induce complement-dependent cytotoxicity in vitro53. Thus, complement is probably essential for optimal protection against SARS-CoV-2, but its activation must be carefully regulated to avoid systemic coagulopathy and organ failure54.

Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis

The opsonization of pathogens and formation of immune complexes by IgM, IgG and IgA can lead to enhanced Fc-mediated ADCP by macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells and neutrophils. Following the internalization of pathogen-bound immune complexes binding to FcRs, pathogens are trafficked to lysosomes, where degraded peptide antigens are loaded onto MHC molecules for presentation to and priming of T cells. Alveolar macrophages are sentinel airway immune cells that are crucial for preserving the delicate balance between inflammation against pathogenic insults and retention of airway architecture. The activation of alveolar macrophages and ADCP are indispensable for Fc-dependent antibody-mediated protection in a mouse model of IAV infection55. Furthermore, in a mouse model of SARS-CoV infection, phagocytes are required for antibody-mediated viral clearance56. In hospitalized patients with COVID-19, spike-specific antibodies mediating ADCP are associated with survival57. Interestingly, RBD-specific antibodies that signal through FcγRIIIB and mediate antibody-dependent neutrophil phagocytosis have been associated with more severe disease. These results highlight the importance of both effector cell type and epitope specificity of functional antibodies in determining clinical outcomes33,57. During severe COVID-19, massive immune cell infiltration is observed in the lungs, which probably contributes to antiviral responses but also to dysregulated high levels of cytokines58,59. Furthermore, proteomic and metabolomic analysis of patients with severe COVID-19 revealed enrichment of pathways involved in macrophage function, in addition to platelet degranulation and the complement system60. All of these events can be potentiated via Fc-dependent mechanisms. It is important to note that whether antibodies capable of stimulating ADCP are protective or pathogenic in the context of human infection is not entirely clear. In some cases, increased titres of specific FcR-activating antibodies may simply correlate with protection or with severe disease, without having a direct causative role. The effect of these antibodies on disease outcome may also depend on the specific FcRs that they engage, the cell types expressing those FcRs, the antigen or epitopes to which they bind and the kinetics with which they act during infection.

NETosis

Neutrophils phagocytose immune complexes, resulting in oxidative burst and antigen cross-presentation to CD8+ T cells61. Although their prototypical function is as first responders during bacterial infections, neutrophils have also been attributed protective functions during viral infections62. FcR-mediated activation of neutrophils can stimulate NETosis63,64. Furthermore, both SARS-CoV-2 viral particles alone and serum from hospitalized individuals in the acute phase of infection can induce NETosis65. Indeed, our group has shown that immune complexes consisting of pseudotyped lentiviruses expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with IgA from convalescent serum induce NETosis in an FcαR-dependent manner66. Although both IgG-containing immune complexes and high titres of virus can stimulate NETosis, IgA-containing immune complexes stimulated NETosis considerably more potently66.

Despite the antimicrobial functions of NETs, they are also commonly associated with adverse outcomes during respiratory virus infections67–69. During SARS-CoV-2 infection, NETosis leads to endothelial injury and platelet-mediated thrombosis, similar to the effects observed following SARS-CoV-2-induced ADCD49,70–72. Increased levels of neutrophil activation markers — including cell-free DNA, the myeloperoxidase–DNA complex, citrullinated histone H3 and neutrophil elastase — are found in the serum of patients with severe COVID-19 (refs 70,73). Indeed, increased IgA-mediated neutrophil activation correlates with more severe disease in adults, indicating that in the setting of high viral load, antigen-specific IgA may exacerbate NETosis and contribute to immunopathology74. By contrast, studies at earlier stages of infection suggest that mucosal IgA-mediated virus neutralization results in less severe disease75. Whether NETosis during the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection, when viral titres are low, expedites viral clearance remains to be determined. Importantly, the secretory component of secretory IgA impairs its ability to bind to FcαRI and stimulate NETosis, and therefore minimizes the risk of antibody-mediated immunopathology, making it a favourable target for induction by mucosal SARS-CoV-2 vaccines designed to elicit IgA responses at the site of infection76.

Other Fc-dependent functions

Antibodies to platelet factor 4 (PF4) from patients with vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) form immune complexes and activate platelets through crosslinking of FcγRIIA, the only FcR expressed on human platelets77,78. Notably, antibodies from patients with VITT induced platelet aggregation in the presence of adenoviral particles in a dose-dependent manner; however, this could be avoided by pharmacological inhibition of the tyrosine kinases SYK and BTK or by administering C5aR-neutralizing antibodies, all of which inhibit FcR signalling79–81. However, the antibodies that cause VITT after adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccination seem to be distinct from those elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection, and SARS-CoV-2 infection is known to result in thrombotic sequelae distinct from those observed in patients with VITT82.

Furthermore, despite initial concerns of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of disease, on the basis of previous observations from infection with SARS-CoV83 or feline infectious peritonitis virus84, there is little evidence of this phenomenon occurring in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Indeed, far from causing exacerbation of disease, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines containing the Wuhan-like (ancestral) spike antigen have continued to show significant protection against severe disease, even in the face of antigenically distinct variants, such as Omicron, for which there are significant reductions in neutralizing antibody titres85. This situation contrasts with the prototypical example of ADE in the context of Dengue virus infection, in which sub-neutralizing concentrations of antibodies enhance infection through opsonization of virus and uptake into FcR-expressing phagocytes86. Plasma from infected, but not vaccinated, individuals facilitated FcγRIIIa-dependent SARS-CoV-2 infection of monocytes ex vivo and resulted in pyroptosis, which could potentially contribute to aberrant inflammation observed in patients with COVID-19 (ref. 87). However, no infectious virus was recovered from the infected monocytes, demonstrating that SARS-CoV-2 infection of phagocytes in this context is abortive88–90. Furthermore, it is difficult to establish the extent to which monocyte pyroptosis might contribute to overall COVID-19 disease severity given the complexity of the pathways that contribute to pathogenicity in infected individuals. Indeed, previous studies of ADE in Dengue virus infection have shown that the factors contributing to disease enhancement are complex and include not only increased viral titres but also suppression of antiviral responses86.

Roles of FcR-bearing effector cells

In animal models of SARS-CoV-2 infection, Fc-dependent effector functions of monoclonal antibodies were required to enhance viral clearance, minimize immunopathology and maintain respiratory processes30,91,92 (Box 1). Monocytes have a central role in Fc-dependent protection mediated by monoclonal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, probably through resolving inflammation as monocyte depletion did not affect virus titres in vivo19,91,92. By contrast, CD8+ T cells reduced viral titres in an Fc-dependent manner, probably through ADCP that results in increased presentation of viral antigens to CD8+ T cells and subsequent T cell-mediated lysis of infected cells91. The roles of neutrophils and NK cells in Fc-dependent antibody-mediated protection from SARS-CoV-2 are less clear, as separate depletion studies have reported inconsistent results in K18-hACE2 transgenic mice challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (refs 91,92). One study using the monoclonal antibody CoV2-2050 found no contribution from NK cells or neutrophils in mediating protection91, whereas another study found that NK cells and neutrophils contributed to protection mediated by the monoclonal antibody CV3-1 (ref. 92). Both CoV2-2050 and CV3-1 target the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, but differences in antibody affinity and neutralization potency may explain their differential dependence on FcR-bearing cell types. In addition, the study of CV3-1 used a larger infectious dose of SARS-CoV-2 (105 focus-forming units compared with 103 plaque-forming units), leading to increased viral burden and more acute disease progression. Furthermore, the timing of antibody administration for CV3-1 was later than for CoV2-2050 (3 days post-infection compared with 1 day post-infection), suggesting that the kinetics of antibody delivery during infection may affect the requirement for FcR-bearing cell types. Efficient neutralization of a lower challenge dose of SARS-CoV-2 by CoV2-2050 early in the infection may mask the requirement for neutrophils and NK cells, which may only be necessary to resolve disease when neutralization is not efficient. Nevertheless, it is evident that the involvement of specific immune cells in mediating protection from SARS-CoV-2 is highly context dependent even in well-controlled animal models. It is also important to consider that the identification of cell types responsible for Fc-dependent antibody-mediated protection in mice (and other animal models) does not necessarily translate directly to humans owing to factors including differences in the FcR expression profile of these cells (Table 1) and differences in the relative abundance of these cell types in tissues and in circulation. In humans, delayed maturation of the antibody response, characterized by a paucity of FcR-activating antibodies, correlates with more severe disease57. Specifically, opsonophagocytosis and complement fixation by spike-specific antibodies were less likely to be found in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, whereas these pathways were enriched in those that resolved infection33,93.

Features of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2

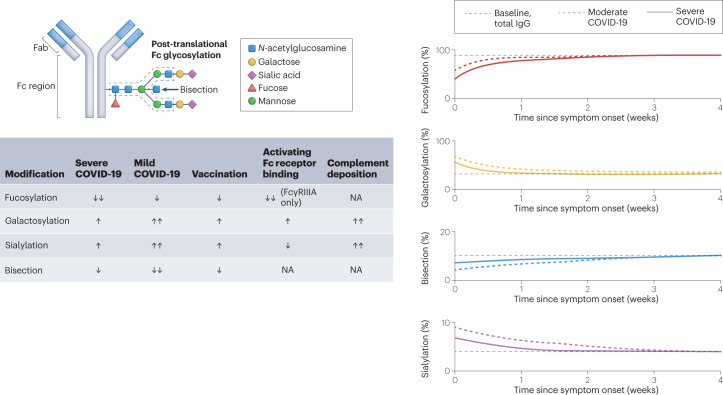

In addition to antibody isotype, several other features of antibodies influence both their ability to elicit Fc-dependent effector functions and the requirement of those functions for mediation of protection. For example, both the affinity of an antibody for its antigen and the affinity with which it binds to FcR affect the stability of immune complex formation and the FcR clustering that is required to promote the signalling leading to downstream effector functions. The glycosylation state of antibodies is also of great importance in modulating their FcR-binding characteristics (Fig. 2), and the glycan structures of antibodies induced by infection or vaccination are now known to be different. In a polyclonal immune response, the kinetics and relative concentrations of different types of antibody (for example, neutralizing and non-neutralizing) are also crucial determinants of infection outcomes and mechanisms of antibody-mediated protection or disease promotion. Finally, the specific epitope bound by an antibody can profoundly influence the potency of FcR activation, as has been shown in the context of IAV and HIV, for example94–96. In the context of SARS-CoV-2, there is emerging evidence of epitope specificity having a role in the ability to activate Fc-dependent effector functions, although more systematic studies are needed97,98. Below, we discuss how these properties influence antibody function in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Fig. 2. Antibody glycoforms are shaped by infection and vaccination, and modulate Fc-dependent effector functions.

The crystallizable fragment (Fc) regions of antibodies are post-translationally modified with patterns of glycosylation that shape their function. The relative levels of fucosylation, galactosylation, sialylation and bisection of antibody Fc regions have all been reported to affect the outcome of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with transient decreases in fucosylated antibodies that return to baseline levels of fucosylation 4–6 weeks after infection. Antibody afucosylation results in more potent Fc receptor (FcR) activation, specifically of FcγRIIIA. By contrast, galactosylation levels are increased in response to infection and vaccination. Antibody galactosylation enhances FcR activation, albeit to a lower level than does afucosylation, but is associated with more potent complement deposition. Antibody sialylation also increases upon vaccination or infection. Sialylation slightly reduces binding to activating FcRs, but enhances complement deposition. By contrast, levels of bisection slightly decrease with infection and vaccination, although the biological relevance of this is unclear as neither FcR binding nor complement deposition seem to be affected. The graphs in the right-hand panel depict the percentage of total or anti-spike IgG with specific glycosylation patterns in patients at baseline, with moderate COVID-19 (hospitalized, non-intensive care) or with severe COVID-19 (hospitalized, intensive care) following weeks after symptom onset. Fab, fragment antigen-binding. NA, no effect observed in response to changes in modification level.

Affinity for antigen

The potency of antibody-mediated Fc-dependent effector functions depends on two points of contact: the affinity of the antibody Fab region for antigen and the affinity of the antibody Fc region for FcR. In addition, antibody-binding epitopes proximal to the cell membrane are preferential for efficient FcR clustering and the stabilization of immune synapses99,100. In terms of SARS-CoV-2 antigens, the spike protein consists of two subunits: S1, consisting of the N-terminal domain (NTD) and RBD, which mediates attachment to the host cell receptor ACE2; and S2, which is responsible for spike trimerization and membrane fusion. Importantly, the SARS-CoV-2 RBD is dynamic and can assume either a ‘down’ or ‘up’ conformation, the latter of which is favourable for ACE2 binding101. Up to 80% of neutralizing antibodies from convalescent individuals bound either on or proximal to the RBD, with the remaining 20% of neutralizing antibodies targeting the NTD or S2 subunits2,102–104. Although neutralizing antibodies can mediate protection independently of Fc-dependent effector functions, many require these functions for optimal activity. Furthermore, non-neutralizing antibodies that bind to sites distal from the RBD (such as the S2 domain) can also elicit Fc-dependent effector functions that may contribute to protection in vivo105.

Many SARS-CoV-2 VoCs exhibit convergent evolution of mutations concentrated around the RBD, NTD and polybasic furin cleavage site of spike protein that enhance immune evasion by reducing antibody binding and/or promoting transmissibility, thereby promoting overall fitness106. However, whereas neutralizing antibodies are constrained to recognizing limited epitopes involved in binding to and fusion with host cells, up to 95% of total spike-specific antibodies are non-neutralizing and can bind to epitopes spread across the spike protein107,108. These antibodies retain the ability to induce Fc-dependent effector functions. Although vaccine-elicited antibodies neutralized more recent VoCs such as Omicron quite poorly relative to ancestral SARS-CoV-2, significant binding of vaccine-elicited antibodies to Omicron full-length spike protein was preserved, suggesting the maintenance of conserved spike epitopes recognized by non-neutralizing antibodies capable of FcR activation107. Likewise, convalescent plasma raised against early SARS-CoV-2 variants had a marked decrease in neutralization activity against VoCs harbouring mutations in RBD and NTD, whereas titres of antibodies that elicit Fc-dependent effector functions were only slightly reduced97. Therefore, despite the accumulation of antibody-escape mutations in antigenic hot-spots such as RBD, antibodies that bind outside of these regions probably contribute to protection in the absence of neutralization. The diversity of epitopes that can be bound by antibodies capable of eliciting Fc-dependent effector functions (mediated by both neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies) may explain the overall lack of antigenic escape relative to the more discrete epitopes that contribute to neutralization. Indeed, vaccine effectiveness against VoCs such as Omicron remains high in terms of preventing severe disease and hospitalization despite low serum titres of neutralizing antibodies109–111. This protection is probably mediated, at least in part, by Fc-dependent antibody effector functions, although vaccine-induced T cell responses against spike protein or more conserved internal antigens must also be considered13,35,112–114.

Compared with plasma from individuals infected with the Alpha or Delta SARS-CoV-2 variants, convalescent plasma from individuals infected with the Beta variant contained higher titres of cross-reactive antibodies to spike proteins from other VoCs that mediate Fc-dependent effector functions. This may result from a shift in the immunodominant epitopes on the spike protein of the Beta variant, as antibodies raised to Beta were more focused on epitopes outside of the ACE2-binding site that recognize RBD in both ‘up’ and ‘down’ conformations, analogous to the S309 monoclonal antibody112,115–117. Antibodies induced by infection or by vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 have demonstrable differences in titres and ratios of neutralizing and FcR-binding antibodies that may depend on exposure route, antigen load, antigen conformation or cytokine milieu97,98,107,118. Changes in antigenicity are not the only factors that determine the immunodominance hierarchy, as previous research on IAV haemagglutinin has shown that vaccination route and vaccine formulation also shape immunodominance119. To rationally design next-generation vaccines for SARS-CoV-2, strategies should tailor antibody responses towards evolutionarily conserved antigenic sites capable of eliciting Fc-dependent effector functions, in addition to inducing neutralizing antibodies that often target epitopes prone to mutation or antigenic drift.

Glycosylation

Glycosylation of the Fc domain is a crucial determinant of antibody structure, function and stability120,121. Antibody glycosylation is crucial in mediating Fc–FcR interactions as aglycosylation ablates FcR binding122. The core bi-antennary glycan that decorates glycosylated antibodies is further modified by conserved patterns of fucosylation, galactosylation, bisection and sialylation (Fig. 2). For example, the human IgG1 Fc region is glycosylated at the conserved Asn297 residue, and IgG1 antibodies in healthy adults are typically characterized by high levels of fucosylation (85–95%), intermediate levels of galactosylation (25–40%), low levels of bisection (5–15%) and low levels of sialylation (2–15%)123,124. The glycosylation pattern of IgG1 directly influences its affinity for FcγR. Notably, afucosylation of IgG1 increases its affinity for FcγRIIIA and FcγRIIIB by tenfold125. Whereas galactosylation only slightly increases FcR affinity and sialylation slightly decreases FcR affinity, both of these glycosylation patterns increase ADCD125–127. The biological relevance of bisection with respect to antibody function remains unknown, as it affects neither FcR affinity nor complement deposition126. Heterogeneity of the core glycan complex is associated with various factors including age, sex, body mass index and infection status128,129.

Glycosylation profiles of SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific antibodies differ in response to vaccination or infection130–133. Patients with severe COVID-19 transiently produce a higher proportion of afucosylated spike-specific antibodies than patients with milder disease; antibody fucosylation levels then return to baseline 4–6 weeks after symptom onset130–133. The processes that regulate antibody fucosylation in response to infection are incompletely understood but they may be related to the relative proportions of antibody-secreting cell subsets. The transient increase of afucosylated antibodies after infection could originate from short-lived plasma cells as these cells have lower levels of glucose import than long-lived plasma cells produced later in infection and may therefore produce antibodies with altered glycosylation profiles134. Changes in the expression profiles of glycosyl and fucosyl transferases responsible for processing of the Fc glycan are also likely to be important in determining the glycan profile135. Increased titres of afucosylated antibodies and hence more potent FcγR activation were associated with aberrant secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by alveolar macrophages in vitro and platelet-mediated thrombosis in patients with severe disease, implicating a role for these antibodies in immunopathology81,132,133. By contrast, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination generates fucosylated IgG1, consistent with reports of influenza virus and hepatitis B virus vaccination130,136. The mechanisms driving differential antibody fucosylation after vaccination or natural infection with SARS-CoV-2, and the extent to which this occurs in the context of other viruses, are not yet clear, but could be partially explained by the context of antigen presentation to B cells133. It has been suggested that direct contact of B cells with the membrane of infected cells facilitates the production of afucosylated antibodies after infection through unknown host receptor–ligand pairs133. Importantly, this led to a striking dichotomy whereby the relative overabundance of afucosylated antibodies was uniquely biased towards surface proteins from enveloped viruses, but did not occur in the context of soluble proteins, internal proteins of enveloped viruses or non-enveloped viruses133. Antibody fucosylation levels must also be determined by additional factors, such as differential cell type-specific expression of the postulated host receptor–ligand pairs, as the BNT162b2 SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine promotes antibody fucosylation despite the fact that spike protein is presented on host cell membranes130,137.

Antibody galactosylation and sialylation have minimal effects on FcR affinity, but levels of both are upregulated in infected individuals and correlate with disease severity133,138. Importantly, both of these glycosylation patterns potentiate ADCD and thus may contribute to the complement-associated pathophysiology observed in severe COVID-19 (refs 130,132,133,138). After infection or vaccination, levels of spike-specific IgG1 bisection remain the same or transiently decrease, and lower levels of bisection correlated with recovery from infection130,131,133,138.

Thus, measuring the relative abundance of antigen-specific antibody isotypes alone is not sufficient to predict the profile of Fc-dependent effector functions that they may elicit or how they might influence clinical outcomes. Fc glycosylation profiles have a pivotal role in determining antibody function. A more complete understanding of the determinants that regulate antibody glycosylation profiles may lead to improvements in vaccine effectiveness and new therapeutic interventions to prevent or treat severe disease in cases in which particular glycosylation profiles are associated with poor clinical outcomes. However, there is a paucity of studies that have directly compared Fc glycosylation profiles after vaccination or infection in a well-controlled cohort using a consistent experimental methodology to assess Fc glycosylation. This leaves uncertainty regarding the ways in which each type of exposure shapes Fc glycan profiles, and further study of this important area is required. For example, infection induces a distinct set of inflammatory pathways relative to vaccination and usually results in more persistent and diverse antigen expression, all of which could be anticipated to influence Fc glycosylation.

Kinetics and relative concentration

The kinetics and magnitude of the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 are influenced by both the type of exposure (either vaccination or infection) and the number of exposures. Titres of neutralizing antibodies and antibodies with Fc-dependent effector functions have distinct patterns following vaccination. Indeed, the first dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine elicits lower titres of neutralizing antibodies than are elicited by the second dose34,139. These neutralizing antibodies wane steadily from their peak at 2 weeks after the second dose to 5–10-fold lower titres several months later140. A third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine boosts titres of neutralizing antibodies to even higher levels, and neutralization titres are maintained for at least 4 months against the divergent Omicron variant141. Compared with neutralizing antibodies, antibodies with Fc-dependent functions are induced much more efficiently after the first vaccine dose and persist for longer34,139. The kinetics and durability of antibodies with Fc-dependent functions after additional vaccine doses are currently being investigated. Differences in kinetics between neutralizing antibodies and antibodies with Fc-dependent functions after vaccination may be attributed to the more stringent epitope specificity and affinity required for neutralizing antibodies. Neutralizing antibodies often exhibit high levels of somatic hypermutation and bind with high affinity to a very limited number of epitopes on the spike protein to inhibit viral infection12,142. This process of antibody evolution and maturation continues in germinal centres for up to 6 months after initial antigen exposure12,143.

Extending dose intervals for the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines increases neutralizing antibody titres and reduces hospitalizations and deaths144,145. In addition, extending the interval between vaccine doses also increases antibody avidity to RBD and titres of antibodies with Fc-dependent functions34. Mechanistically, longer intervals between vaccine doses allow for more substantial waning of antibodies elicited by the initial vaccine dose, driven by the contraction of plasmablasts and short-lived plasma cells146,147. This reduces the effects of epitope masking, a phenomenon in which pre-existing antibodies to shared epitopes reduce interactions with B cells specific for that epitope and therefore reduce subsequent expansion of B cell clones and de novo antibody responses to the same epitope148. Indeed, baseline antibody titres are a well-known negative correlate of vaccine response149. However, pre-existing antibodies can also help to promote adaptive immune responses by processes that include driving the uptake of antigen by dendritic cells and trapping of antigen on follicular dendritic cells, thereby promoting B cell selection. Thus, there may be a threshold of pre-existing antibody titres that can promote more effective subsequent antibody responses.

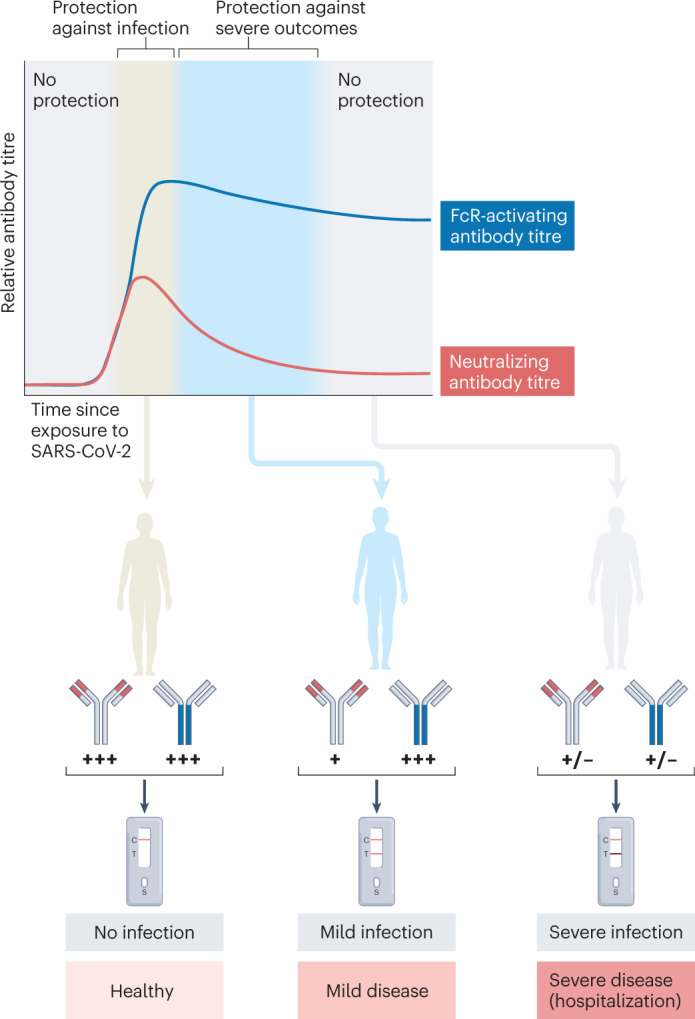

The different kinetics of neutralizing antibodies and antibodies with Fc-dependent effector functions after natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 are well documented150–156. Both neutralizing and Fc-dependent antibody titres have been reported to correlate positively with disease severity, but this is probably a by-product of higher viral loads in severely affected individuals150–152. Studies directly comparing the longevity of functional antibody populations have found that neutralizing antibodies wane more quickly after infection than do Fc-dependent antibodies153. Other studies have found that antibodies that mediate ADCC can be detected even up to 400 days after infection154. Interestingly, immunity conferred by natural infection in combination with vaccination (often referred to as ‘hybrid immunity’) is more durable than immunity conferred by a homologous mRNA vaccine prime–boost regimen and results in the production of higher titres of neutralizing antibodies and of antibodies that mediate Fc-dependent effector functions34,155,156.

Vaccines and antibody therapeutics

Understanding the relative contribution of Fc-dependent antibody effector functions in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection is essential to informing vaccine and therapeutic design, as well as to evaluating their efficacy. Historically, the binding and neutralizing activities of antibodies have been the most commonly measured properties used to assess correlates of protection. However, our deepening understanding of the contribution of Fc-dependent effector functions to the protection mediated by vaccines and monoclonal antibodies warrants the development and validation of standardized assays to account for these functions and to assess their contribution to immunity and their possible use as correlates of protection (Box 2).

Box 2 Considerations for measuring antibody correlates of protection.

Large trials are required to establish immunological correlates of protection. For this reason, factors such as reproducibility and feasibility are key considerations when selecting assays appropriate for mid-scale to large-scale immunogenicity analyses. The scalability and standardization of serological assays such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and microneutralization assays make them well suited for large, multi-centre clinical trials assessing vaccine correlates of protection. However, the immune response to vaccination is multifaceted and the contributions of crystallizable fragment (Fc)-dependent antibody effector functions are not captured by these assays, which focus on binding and neutralization.

ELISAs are amenable to high-throughput assessment of antigen-specific antibodies. Quantitative or semi-quantitative ELISAs are most informative when attempting to establish correlates of protection. However, ELISAs only measure antibody binding. Neutralization assays are therefore often carried out in conjunction with ELISAs. Determination of neutralizing antibody titre is commonly carried out by incubating serially diluted serum samples with virus, transferring these mixtures onto a monolayer of susceptible cells and measuring infectivity. Pseudoviruses are often used in neutralization assays, especially in the context of pathogens that require higher standards of containment. Pseudoviruses are often engineered to express reporters that are convenient for high-throughput processing.

The measurement of Fc-dependent antibody effector functions is considerably more complex than that of antibody binding and neutralization. Many assays that measure Fc-dependent antibody responses use primary immune cells (Table 2). Although this approach maximizes biological relevance, it has limitations in terms of scalability and reproducibility owing to inherent variability between donors. Measurement of Fc-dependent responses at higher throughput is possible using immortalized or engineered cell lines but these often fail to fully recapitulate the complexity of Fc receptor (FcR) signalling in primary cells. Similarly, assays that measure Fc–FcR binding, such as multiplexed bead-based assays, are more amenable to high-throughput analyses but inherently fail to capture functionality. Therefore, a balance must be struck when selecting assays to measure Fc-dependent antibody effector functions: the most biologically relevant assays may not always be feasible for large-scale analyses. Thus, determining high-throughput readouts that can be standardized and that best predict Fc-dependent functional antibody responses is essential for the more widespread uptake of assays that will be required to advance the understanding of how these antibodies mediate protection.

Vaccination

Titres of both spike-binding and neutralizing antibodies have been used as correlates of protection (Box 2) for currently approved COVID-19 vaccines and during preclinical development5,6,157–160. However, many of the preliminary studies were carried out when the circulating virus was more antigenically similar to the vaccine immunogen (typically from the Wuhan-Hu-1 variant of SARS-CoV-2) than is now the case. Correlates of protection must now be reassessed in the setting of new, antigenically divergent, circulating variants of SARS-CoV-2 to determine metrics that reliably predict vaccine effectiveness, durability and establishment of long-term protective responses. Fully vaccinated individuals still experience breakthrough infections with these SARS-CoV-2 variants, although vaccine effectiveness against severe illness and death remains high161. Thus, the correlates of protection for specific outcomes, including asymptomatic re-infection, symptomatic infection, severe disease or death, are likely to differ. Likewise, correlates of protection may differ for particular populations, including the elderly and immunocompromised. High titres of neutralizing antibodies are capable of preventing infection altogether, but neutralizing antibody titres alone do not adequately capture all aspects of a protective immune response. Therefore, efforts are needed to better understand the protective contributions of other components of the immune system, including Fc-dependent antibody effector responses162 (Box 2). Establishing more nuanced correlates for specific outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection will help to streamline future clinical trials and to better inform vaccine policy decisions based on immunological readouts.

Fc-dependent antibody effector functions have repeatedly been shown to contribute to antibody-mediated protection in other contexts, including infection with HIV, IAV or Ebola virus163–165. Although partial protection from disease could be achieved after just one dose of the NVX-CoV2373 recombinant spike protein vaccine for SARS-CoV-2, a second dose led to increased titres of antibodies mediating ADCP and inducing NK cell activation, which correlated with increased protection in non-human primates166. In addition, both neutralization activity and Fc-dependent effector activity were preserved against the Alpha and Beta SARS-CoV-2 variants. These findings are congruent with human studies that have reported the induction of Fc-dependent antibody effector responses after a single dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine139. Titres of neutralizing antibodies and spike-binding antibodies were both associated with protection mediated by the mRNA-1273 vaccine in preclinical and phase III clinical studies157,167. However, despite only low titres of neutralizing antibodies after a single vaccine dose, considerable protection from disease was observed. This suggests that other factors, including, potentially, Fc-dependent antibody effector functions and T cell activation, are also important in vaccine-mediated protection, especially when neutralizing antibody titres are low.

Polyfunctional immune responses are crucial for sustaining vaccine-mediated protection in the setting of increasing mutation of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Recently observed reductions in vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection are attributed to the decreased neutralizing potency of antibodies to the heavily mutated RBD of contemporary SARS-CoV-2 variants such as Omicron85. However, despite the decline in antibody binding and neutralization titres against VoCs, the Fc-dependent effector functions of vaccine-induced antibodies are largely maintained. Specifically, titres of Omicron spike-specific antibodies that bind to FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIA, which are associated with ADCP and ADCC, respectively, were preserved across several vaccine platforms107. This maintenance of antibodies with Fc-dependent effector functions is associated with prolonged protection against severe outcomes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Kinetics of Fc-dependent antibody effector functions after vaccination and association with outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Both neutralizing and crystallizable fragment (Fc) receptor (FcR)-activating antibodies (of which neutralizing antibodies are a subset) are elicited following exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). High titres of neutralizing antibodies are associated with protection against infection, but these titres wane relatively quickly after exposure. Titres of antibodies capable of engaging FcRs are more stable and durable after exposure. Maintenance of these antibodies may be associated with protection against severe outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection even as titres of neutralizing antibodies wane.

To assess whether Fc-dependent antibody responses are true correlates of protection against specific outcomes, robust and standardized assays for evaluating Fc-dependent effector functions following vaccination should be developed and routinely carried out as a supplement to conventional binding assays and neutralization assays. However, this is not a trivial task. Unlike the assessment of antibody binding or neutralization, no single assay can capture all Fc-dependent antibody effector functions (Table 2). There are also practical considerations for the selection of these assays (Box 2).

Therapeutics

The transfusion of plasma from patients who had recovered from COVID-19 was considered to be a promising therapeutic option early in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. However, although this intervention is safe, its effectiveness has been disputed9. Some trials have shown promising efficacy, whereas others have failed to find therapeutic benefit. Differences in trial design including the source of donor plasma, the specific recipient patient population and the timing of plasma administration relative to infection account for some of this variability in outcome. Differences in the antibody profile of donor plasma must also be considered. For many trials, binding and/or neutralizing antibody titres were used to screen donor plasma; however, the specific criteria used to select donors were often inconsistent. Recent studies have identified antibodies capable of eliciting ADCC, ADCP and ADCD as key predictors of the efficacy of convalescent plasma therapy168,169. Interestingly, the CONCOR-1 (Convalescent Plasma for COVID-19 Respiratory Illness) trial found that donor plasma with high levels of neutralization activity and Fc-dependent effector functionality (such as ADCC) achieved a significant reduction in severe outcomes and death169. Donor plasma with enhanced nucleocapsid-specific antibody responses and spike-specific antibodies inducing ADCP by neutrophils may also provide benefit170,171. Passive-transfer studies in animal models of COVID-19 have also shown that functions beyond neutralization have an important role in the in vivo protection afforded by monoclonal antibodies30,91. Indeed, one study showed that robust Fc–FcR engagement and activation of monocytes, neutrophils and NK cells were all necessary to achieve full protection mediated by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in a post-exposure therapeutic context92. Thus, optimal protection is mediated by a combination of antibody-mediated neutralization and Fc-dependent effects. Furthermore, engineered monoclonal antibodies that have increased affinity for activating FcRs are superior to wild-type antibodies at treating and preventing clinical signs of SARS-CoV-2 infection in rodent models172. Together, these data suggest that measuring titres of antibodies with Fc-dependent functions, in addition to neutralizing antibody titres, should be an important consideration in the selection of convalescent plasma donors and in the evaluation of monoclonal antibody therapeutics.

Conclusions and perspectives

Neutralizing antibodies provide a first line of defence to prevent cells from becoming infected, but antibodies can also mediate protection post-infection through their Fc-dependent effector functions. These diverse functions depend on interactions with FcR-expressing immune cells or complement. It is clear that Fc-dependent antibody functions contribute to shaping the outcome of infection with SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses (Fig. 1). However, the framework for understanding their relative contributions remains limited.

An individual’s profile of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 that have Fc-dependent functions is shaped by a large number of variables, including the nature of exposure to viral antigens (infection or vaccine type), route of exposure (parenteral or mucosal), age and underlying health or pregnancy status. Measuring these antibody profiles is more complicated than conventional binding and neutralization assays owing to the diversity of effector pathways that antibodies can engage. Therefore, developing a more detailed framework for understanding how Fc-dependent antibody effector functions contribute to protection requires more routine evaluation and profiling of these antibodies in the context of clinical trials and cohort studies. To facilitate comparability, assays must be selected on the basis of performance, scalability and standardization. The way in which spike protein is expressed — for example, by infection versus transfection, or by using wild-type virus versus pseudovirus — in experimental systems measuring Fc-dependent outcomes is also important to consider.

More work must also be done to determine the outcomes (such as severe illness and death) for which Fc-dependent antibody functions may be useful correlates. In particular, standard immunogenicity assays carried out during routine vaccine evaluation and studies of immunity in convalescent individuals (for example, antibody binding and neutralization assays) should be expanded to take a ‘systems serology’ approach that captures Fc profiles so that these variables can be routinely and broadly assessed for their value as correlates. It is essential that a standardized framework be developed for these assays to facilitate cross-comparisons among different studies. From a feasibility perspective, it is also important that these assays are amenable to relatively high-throughput approaches. It is important to note that correlates of protection do not necessarily imply causation. That is to say that even if robust correlates can be established among Fc-dependent antibody effector functions, it will be crucial to continue investigating the mechanisms of Fc-mediated protection in vivo. These studies require careful consideration of appropriate animal models and a detailed understanding of differences in antibody biology when comparing those model organisms to humans.

In addition to mediating protection, there may also be situations in which dysregulated activation of Fc-dependent antibody effector functions contributes to disease pathology. Understanding these situations is equally important, as they may highlight opportunities for therapeutic intervention (such as FcR-blocking antibodies). The routine standardized measurement of Fc-dependent antibody profiles as outlined above would facilitate these types of study as well.

Overall, deepening our understanding of the contribution of Fc-dependent effector functions to protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection (as well as infection with other pathogens) should lead to improvements in the design and evaluation of vaccines and antibody therapies that are likely to increase their effectiveness and help to mitigate the impacts of antigenic drift as the virus continues to evolve.

Acknowledgements

M.S.M. was supported, in part, by a Canada Research Chair in Viral Pandemics. A.Z. is supported by a Physician Services Incorporated Research Trainee Fellowship and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Graduate Scholarships — Doctoral Award. H.D.S. is supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship and a Canadian Society for Virology United Supermarket Studentship. M.R.D. is supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship and the Fred and Helen Knight Enrichment Award. Y.T. is supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. A.M. is supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship.

Glossary

- Alternative complement pathway

One of the three complement pathways. It is activated by spontaneous hydrolysis of C3 to C3b and C3a, followed by binding of C3b to an infected cell or pathogen.

- Antibody-dependent enhancement

(ADE). An immunological phenomenon in which antibody binding to virus enables its more efficient entry into host cells (infection) and/or more severe disease.

- Bi-antennary glycan

A glycan structure characterized by the addition of branch points to the glycan core.

- Bisection

A modification of the N-glycan core of an antibody by addition of a β1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine residue linked to the β-mannose core.

- Cross-presentation

The internalization and processing of extracellular antigens by antigen-presenting cells for presentation on MHC class I molecules to CD8+ T cells.

- Factor H

A soluble plasma glycoprotein that regulates the alternative complement pathway.

- Immune complexes

Multiprotein complexes consisting of antibody-bound antigens.

- K18-hACE2 transgenic mice

Transgenic mice expressing human ACE2 (hACE2) under control of the human keratin 18 (K18) promoter that are used to study SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infections.

- Lectin pathway

A non-classical complement pathway characterized by activation through mannose-binding lectin and ficolins.

- Neutralizing antibodies

Antibodies that interfere with the ability of a virus to infect a cell.

- Neutrophil extracellular traps

(NETs). Net-like structures composed primarily of chromatin and antimicrobial enzymes released from neutrophils via programmed pathways of NETosis.

- Non-neutralizing antibodies

Antibodies that bind to viral antigens but do not impede the ability of the virus to infect a cell.

- Oxidative burst

The rapid production and release of reactive oxygen species, usually by myeloid cells, as an antimicrobial defence mechanism.

- Polybasic furin cleavage site

A proteolytic excision site recognized by host furin proteases that is present at the S1–S2 junction of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, cleavage of which is required for maturation.

- Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia

(VITT). A rare physiological phenomenon characterized by acute thrombosis and thrombocytopenia following vaccination with some adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccines.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks W. Mothes and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Al-Awwal N, Dweik F, Mahdi S, El-Dweik M, Anderson SH. A review of SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19): pandemic in our time. Pathogens. 2022;11:368. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11030368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey WT, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:409–424. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Planas D, et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596:276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caniels TG, et al. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern evade humoral immune responses from infection and vaccination. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:eabj5365. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj5365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khoury DS, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2021;27:1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cromer D, et al. Neutralising antibody titres as predictors of protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants and the impact of boosting: a meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3:e52–e61. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00267-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty S, et al. Early non-neutralizing, afucosylated antibody responses are associated with COVID-19 severity. Sci. Transl Med. 2022;14:eabm7853. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abm7853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahnan W, et al. Spike-dependent opsonization indicates both dose-dependent inhibition of phagocytosis and that non-neutralizing antibodies can confer protection to SARS-CoV-2. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:808932. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.808932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piechotta V, et al. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021;5:CD013600. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner JS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Nature. 2021;596:109–113. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03738-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gitlin AD, Shulman Z, Nussenzweig MC. Clonal selection in the germinal centre by regulated proliferation and hypermutation. Nature. 2014;509:637–640. doi: 10.1038/nature13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim W, et al. Germinal centre-driven maturation of B cell response to mRNA vaccination. Nature. 2022;604:141–145. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04527-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zohar T, Alter G. Dissecting antibody-mediated protection against SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:392–394. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0359-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu LL, Suscovich TJ, Fortune SM, Alter G. Beyond binding: antibody effector functions in infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:46–61. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk–specific antibodies require FcγR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat. Med. 2014;20:143–151. doi: 10.1038/nm.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruhns P, Jönsson F. Mouse and human FcR effector functions. Immunol. Rev. 2015;268:25–51. doi: 10.1111/imr.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redpath S, Michaelsen TE, Sandlie I, Clark MR. The influence of the hinge region length in binding of human IgG to human Fcγ receptors. Hum. Immunol. 1998;59:720–727. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(98)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruhns P, et al. Specificity and affinity of human Fcγ receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood. 2009;113:3716–3725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcγ receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruhns P. Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood. 2012;119:5640–5649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-380121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazor Y, et al. Enhancement of immune effector functions by modulating IgG’s intrinsic affinity for target antigen. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0157788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapcan E, et al. Covalent stabilization of antibody recruitment enhances immune recognition of cancer targets. Biochemistry. 2021;60:1447–1458. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krugmann S, Pleass RJ, Atkin JD, Woof JM. Structural requirements for assembly of dimeric IgA probed by site-directed mutagenesis of J chain and a cysteine residue of the α-chain CH2 domain. J. Immunol. 1997;159:244–249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.159.1.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woof JM, Kerr MA. IgA function — variations on a theme. Immunology. 2004;113:175–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oortwijn BD, et al. Monomeric and polymeric IgA show a similar association with the myeloid FcαRI/CD89. Mol. Immunol. 2007;44:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Spriel AB, Leusen JHW, Vilé H, van de Winkel JGJ. Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) as accessory molecule for FcαR (CD89) binding of IgA. J. Immunol. 2002;169:3831–3836. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasquier B, et al. Identification of FcαRI as an inhibitory receptor that controls inflammation: dual role of FcRγ ITAM. Immunity. 2005;22:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bournazos S, Wang TT, Dahan R, Maamary J, Ravetch JV. Signaling by antibodies: recent progress. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017;35:285–311. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaumouillé V, et al. Actin cytoskeleton reorganization by Syk regulates Fcγ receptor responsiveness by increasing its lateral mobility and clustering. Dev. Cell. 2014;29:534–546. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schäfer A, et al. Antibody potency, effector function, and combinations in protection and therapy for SARS-CoV-2 infection in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2021;218:e20201993. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan CEZ, et al. The Fc-mediated effector functions of a potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody, SC31, isolated from an early convalescent COVID-19 patient, are essential for the optimal therapeutic efficacy of the antibody. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0253487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wheatley AK, et al. Landscape of human antibody recognition of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain. Cell Rep. 2021;37:109822. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atyeo C, et al. Distinct early serological signatures track with SARS-CoV-2 survival. Immunity. 2020;53:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]