Abstract

Generating adaptive behavioral responses to emotionally salient stimuli requires evaluation of complex associations between multiple sensations, the surrounding context, and current internal state. Neural circuits within the amygdala parse this emotional information, undergo synaptic plasticity to reflect learned associations, and evoke appropriate responses through their projections to the brain regions orchestrating these behaviors. Information flow within the amygdala is regulated by the intercalated cells (ITCs), which are densely packed clusters of GABAergic neurons that encircle the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and provide contextually relevant feedforward inhibition of amygdala nuclei, including the central and BLA. Emerging studies have begun to delineate the unique contribution of each ITC cluster and establish ITCs as key loci of plasticity in emotional learning. In this review, we summarize the known connectivity and function of individual ITC clusters and explore how different neuromodulators conveying internal state act via ITC gates to shape emotionally motivated behavior. We propose that the behavioral state-dependent function of ITCs, their unique genetic profile, and rich expression of neuromodulator receptors make them potential therapeutic targets for disorders, such as anxiety, schizophrenia spectrum, and addiction.

Introduction

The amygdala plays a critical role in determining the emotional significance of sensory signals, and in regulating the memory and response to aversive or appetitive events (LeDoux, 2000). According to the canonical view, auditory and somatosensory information from the thalamus and cortex converges onto the lateral amygdala (LA). The LA then sends the information via glutamatergic projections to the basal amygdala (BA) (Pape and Paré, 2010). The BA is also reciprocally connected with the ventral hippocampus and mPFC, which provide contextual information and top-down control, respectively (Senn et al., 2014; Adhikari et al., 2015). Approximately 80% of LA and BA neurons, collectively referred to as BLA, are glutamatergic projection neurons similar to those of the cortex, although they are randomly oriented and lack laminar organization (McDonald, 1982b). The remaining 20% are GABAergic neurons that can be classified by neuropeptide expression, morphology, and intrinsic electrophysiological properties (Krabbe et al., 2018). The LA and BA project to the central amygdala (CeA). The LA mostly provides excitatory drive to the lateral subdivision (CeL), whereas the BA also innervates the medial subdivision (CeM). CeL, in turn, inhibits CeM (Krettek and Price, 1978; Aggleton, 1992). The CeL consists mostly of GABAergic neurons with morphology similar to that of medium spiny neurons of the striatum, whereas the CeM contains sparsely spiny neurons that resemble neurons in the ventral pallidum (McDonald, 1982a). The CeM is the output nucleus and projects to brainstem and hypothalamus areas that control the expression of defensive behaviors, such as freezing, hormonal secretions, and autonomic responses (LeDoux, 2000; Ciocchi et al., 2010; Penzo et al., 2014).

This model of amygdala information processing has been challenged by growing evidence that BLA and CeA can mediate independent, parallel associative functions in emotional memory formation (Maren, 2005; Balleine and Killcross, 2006; Ciocchi et al., 2010; Penzo et al., 2014) and by our emerging understanding of the role of inhibitory neurons in regulating these parallel information streams (Krabbe et al., 2018; Hagihara et al., 2021; Whittle et al., 2021).

Surrounding the periphery of BLA are the intercalated cells (ITCs), which are anatomically and functionally distinct clusters of densely packed GABAergic neurons (Millhouse, 1986; Paré and Smith, 1993). ITCs share the unifying role of providing feedforward inhibition to input and output nuclei of the amygdala. Feedforward inhibition has been theorized to perform several functions, such as increasing the “signal-to-noise” ratio by allowing only strongly driven neurons to overcome inhibition and fire (Buzsáki, 1984), enhancing the fidelity of synaptic coincidence detection (Pouille and Scanziani, 2001), and normalizing output in the face of varying levels of excitatory drive (Pouille et al., 2009). ITC clusters convey stimuli and state-dependent feedforward inhibition to their target nuclei to regulate output in this manner.

ITCs are crucial for amygdala-dependent emotional processing, and their dysfunction has been shown to impair fear extinction, fear generalization, and social behavior (Likhtik et al., 2008; Kuerbitz et al., 2018). ITCs exert control over the CeM, which projects to fear-promoting brainstem and hypothalamic structures via direct inhibition, and indirectly through feedforward inhibition of the CeL (Royer et al., 1999). They also project to the attention circuits of the basal forebrain (Paré and Smith, 1994) and regulate the reciprocal interaction of BLA with mPFC (Berretta et al., 2005; Amano et al., 2010; Palomares-Castillo et al., 2012). An advancement in our understanding of the parallel processing streams within the amygdala is the discovery that ITCs not only control the output of the amygdala but also receive direct sensory inputs from thalamic and cortical areas and provide feedforward inhibition onto BLA principal cells effectively modulating sensory input to the amygdala (Marowsky et al., 2005; Mańko et al., 2011; Morozov et al., 2011; Asede et al., 2015, 2021b; Strobel et al., 2015). Another fundamental insight comes from a recent study demonstrating that the balance of activity between ITC clusters regulates the switch between high- and low-fear states (Hagihara et al., 2021).

In addition to receiving a wide range of information about sensory experiences and context, ITCs act as barometers of internal state via strong expression of diverse neuromodulators (Palomares-Castillo et al., 2012; Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021; Asede et al., 2021b; Hagihara et al., 2021). They possess intrinsic firing properties that depend on prior synaptic activity and a nonuniform spatial distribution of inhibitory connections that provide lateral feedback within individual ITC clusters that refine this information in time and space (Royer et al., 1999, 2000b). Finally, their excitatory drive is altered by experience (Royer and Paré, 2003; Asede et al., 2015). These characteristics make ITCs ideal for their role as gate keepers and conveyors of internal state to the amygdala. Given that our understanding of ITCs has evolved considerably in recent years, in this review, we discuss the connectivity and functional role of individual ITC clusters in behavior. We illustrate characteristic intrinsic properties of ITC neurons. Finally, we examine the impact of the rich neuromodulator and neuropeptide receptor expression profile of ITCs, and how their unique connectivity allows them to convey information on internal state to the amygdala circuit through these neuromodulatory influences. Combined, these attributes and the expression of mental illness associated genes in ITCs make ITCs a potential target for pharmacological manipulation of fear and anxiety-related disorders.

ITC structure and function

ITC cluster segregation and development

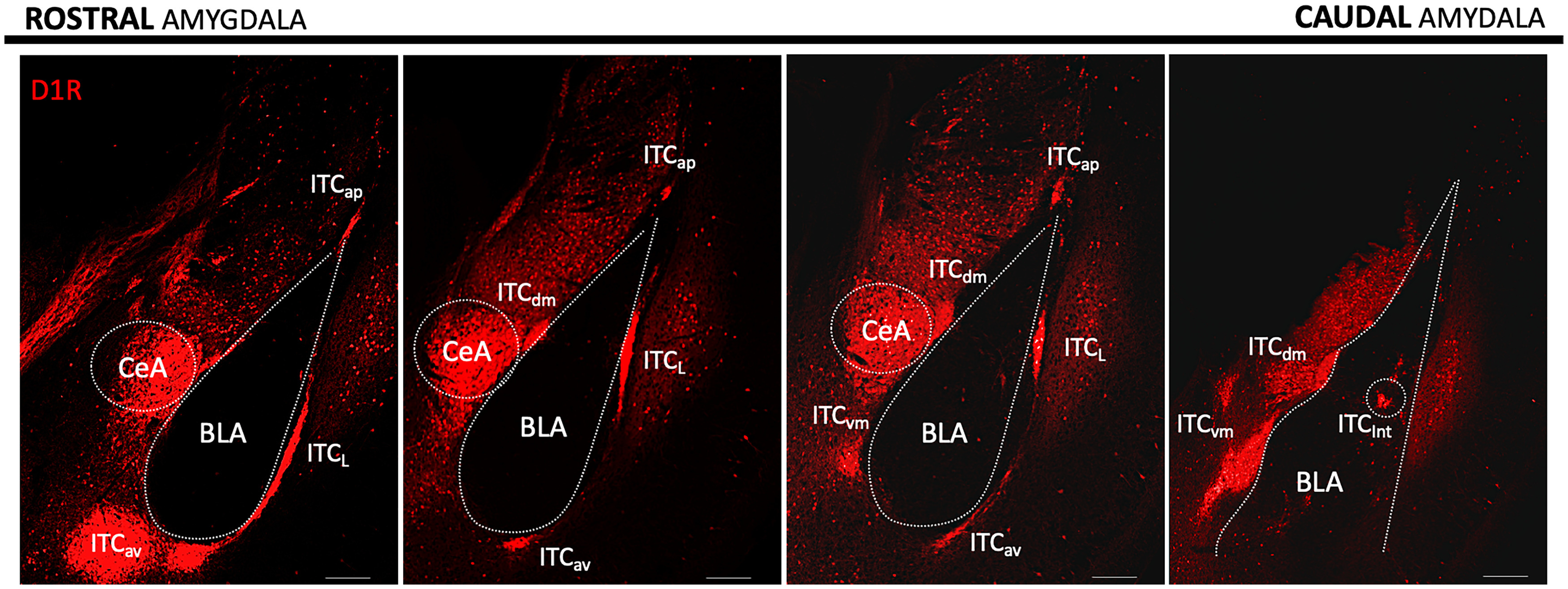

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the amygdala in rodents revealed seven morphologically and anatomically distinct ITC clusters (Marowsky et al., 2005; Busti et al., 2011; Hagihara et al., 2021). These clusters are named apical ITC (ITCap), lateral ITC (ITCL), anteroventral ITC (ITCav), ventromedial ITC (ITCvm), dorsomedial ITC (ITCdm), internal ITC(ITCint), and posteroventral ITC (ITCpv). These clusters are visualized in Figure 1. Historically, the ITCav was often referred to as the anterior main ITC and the ITCvm as the posterior main ITC (for literature nomenclature coregistration, see Hagihara, 2021, their Supplemental Table 1). ITCs have also been studied in other species, and the orientation of the amygdala and ITC cluster segregation varies between species. In primates, ITCs are not confined to discrete cell clusters but form a net surrounding the entire amygdala, which penetrates the interfaces between the LA, BA, basomedial amygdala (BMA), and CeA nuclei (Zikopoulos et al., 2016). These nets are characterized by distinct populations of neurons with different morphologies and expression patterns (Zikopoulos et al., 2016), suggesting that primate ITCs, while lacking spatial segregation, may also possess distinct subtypes. Because of the scarcity of ITC studies involving primates, it is unclear how primate ITCs function, but the general theme of serving as the interface between input-output nuclei of the amygdala appears to be preserved. For clarity to a general audience, we use the nomenclature of the analogous structure in the mouse when describing the seminal discoveries made in other species.

Figure 1.

Rostral-caudal segregation of ITC clusters in the mouse amygdala. Confocal image rendition of ITC clusters in 300 μm brain slices from a Drd1a-Cre-Ai9_tdTomato mouse line labeling D1R neurons in red. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Fate mapping studies indicate that, in contrast to GABAergic neurons in the BLA and CeA, which arise predominantly from the medial ganglionic eminence and ventrolateral ganglionic eminence, respectively, all ITCs originate from the dorsal lateral ganglionic eminence (Waclaw et al., 2010). They express Foxp2, Pbx3, and Meis2 (Kaoru et al., 2010), and transcription factors Tshz1 and SP8 are required for proper localization, molecular identity, and ultimately survival of ITCs (Kuerbitz et al., 2018, 2021).

Cell types and morphology

Both rodents and primates contain small, medium-sized spiny neurons, and larger aspiny neurons. The majority of ITCs are small to medium spiny neurons with 9-18 μm soma, and a minority (<5%) are large ITCs (>30 μm ovoid soma) with predominately aspiny dendrites (Millhouse, 1986; Bienvenu et al., 2015). In general, the small ITCs have electronically compact, spiny, often bipolar dendrites confined to the cluster and aligned parallel to the axon track surrounding the BLA in which they reside. Their axons collateralize extensively within the cluster to provide local lateral inhibition of other ITCs and project forward to inhibit specific amygdala nuclei (Paré and Smith, 1993; Royer et al., 1999, 2000a; Geracitano et al., 2007; Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021). In rodents, ITC axons may be topographically organized in their target fields, with asymmetric dendrites and axons to reflect the underlying structure, as demonstrated in guinea pigs (Royer et al., 2000a). Further support for this view comes from studies that have demonstrated heterogeneity within ITC clusters and cluster subtypes based on axonal projection pattern (Busti et al., 2011; Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021; Asede et al., 2021b; Kuerbitz et al., 2021). Axonal projections and inhibition are not obviously topographically organized in primate; Instead neurochemical identity determines connectivity patterns (Zikopoulos et al., 2016). The rodent large ITCs mainly reside at the periphery of ITC clusters and express GABAA receptor GABAAR1 and metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR1α (Bienvenu et al., 2015). Large ITCs surrounding the ITCdm are activated in vivo by noxious stimuli and are innervated by the posterior intralaminar nucleus (PIN) of the thalamus (Bienvenu et al., 2015). They innervate BLA interneurons and also project to distant brain areas, such as the perirhinal, entorhinal, and endopiriform cortex thereby disinhibiting a distributed network (Bienvenu et al., 2015).

ITC intrinsic properties

There are minor differences in ITC intrinsic properties between clusters (Marowsky et al., 2005; Asede et al., 2021b), and subtypes have been identified within clusters (Busti et al., 2011), but they form a single neuronal class distinct from classical inhibitory BLA interneurons. Compared with other amygdala neurons, ITCs have a high input resistance (527-865 mΩ) and small capacitance (27-65 pF) in line with their relatively small size (intrinsic properties reported are the range of values reported in the literature cited herein). They exhibit a very hyperpolarized resting potential (−76 to −87mV), a pronounced afterhyperpolarization (10.3-12.8 mV), and a maximum firing rate of (∼20-37 Hz). An unusual characteristic of ITC cells is that they have a slowly de-inactivating potassium channel (ISD) that activates at subthreshold voltage driven by excitatory synaptic activity (Royer et al., 2000b). It is rapidly inactivated when the cell fires and then slowly de-inactivates over seconds. Therefore, following synaptic depolarization or action potentials, the channels inactivate generating after-depolarizations, making the neuron more excitable. Given that the de-inactivation is very slow and each action potential renews the inactivation, this hyperexcitable state is self-renewing. Because of the hyperpolarized resting potential of ITCs, another consequence of slowly de-inactivating potassium channels (Isd) is that they can be activated by subthreshold synaptic potentials and transiently make the neuron less excitable to future synaptic inputs. This favors synchronized inputs by narrowing the synaptic integration window. This dependence of ITC excitability on its own recent firing history may sharpen the temporal precision of lateral inhibition and enhance signal-to-noise in feedforward projections. Consistent with these properties in vivo, ITCs have a high and irregular firing rate, 14 Hz on average and up to 35 Hz for ITCdm in awake cats (Collins and Paré, 1999).

ITC cluster connectivity and function

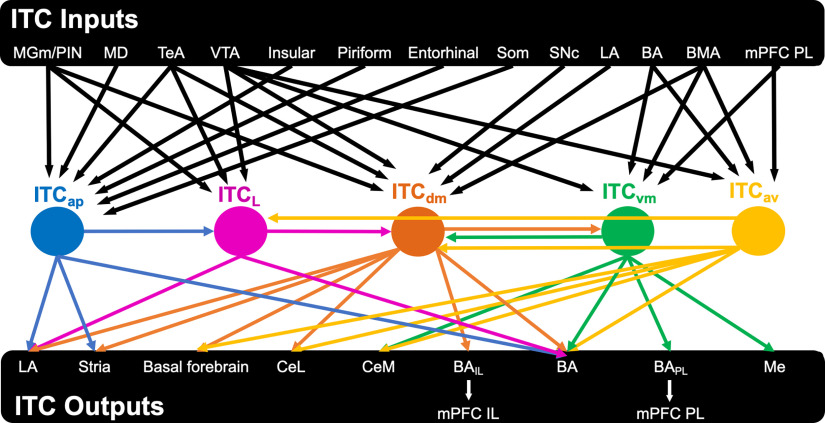

Among the seven identified ITC clusters, only five have been well studied. We will highlight the unique properties and functions of these clusters based on the available evidence. A summary of their inputs and outputs is shown in Figure 2. Of note, previously described “main” intercalated cluster (main) will be referred as either ITCav or ITCvm in this section.

Figure 2.

ITC inputs and outputs. This scheme demonstrates the current understanding of ITC cluster connectivity by consolidating experiments, including optogenetics, 3D neuron reconstruction, and electrical stimulation over the past 20 years. The general theme is that ITCs provide a wide web of sensory context to different amygdala and extra-amygdala structures. Black arrows indicate inputs to different clusters. Each ITC cluster and corresponding output are represented in their unique colors. MD, medial dorsal thalamus; TeA, temporal association cortex; BAIL, Som, somatosensory cortex; BA neurons projecting to mPFCIL; BAPL, BA neurons projecting to mPFCPL; Stria, striatum/transition zone striatum.

ITCap

Neurons of the ITCap cluster have a compact dendritic tree, onto which they receive cortical and thalamic sensory inputs from the medial geniculate nucleus (MGm), PIN, and medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus and from the temporal association, entorhinal, insular, piriform, and somatosensory cortex (Asede et al., 2021b). In addition to intracluster arborization, ITCap cells innervate LA, providing feedforward inhibition to LA principal cells, and also project to dorsal striatum (Asede et al., 2021b). The ITCap cluster thus provides an indirect inhibitory gating route between sensory thalamus and cortical areas and LA. The diverse input from cortical association areas suggests that ITCap integrate a wide range of information, which may provide specificity and context to sensory stimuli entering the amygdala.

ITCL

Electrical stimulation of external capsule (Marowsky et al., 2005) and optogenetic activation of fibers from temporal association cortex (Morozov et al., 2011) and auditory cortex (Strobel et al., 2015) result in monosynaptic glutamatergic responses in ITCL neurons. ITCL primarily targets the BLA, providing cortically driven feedforward inhibition to BLA principal cells (Kaoru et al., 2010; Morozov et al., 2011). It is not known whether this pathway is reciprocal, which could serve as a feedback inhibitory circuit controlling the BLA as has been demonstrated for ITCdm (Asede et al., 2015). ITCL cells also have monosynaptic connections to ITCdm (Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021). The ITCL cluster thus provides cortical and thalamic driven feedforward inhibition to BLA principal cells, which are also directly driven by these inputs. The ITCL and the ITCap may serve analogous functions for BA and LA, respectively.

ITCav

ITCav is the anterior part of the previously named “main” ITC cluster. ITCav neurons have a poorly branching, round-to-bipolar dendritic tree mostly confined within the boundaries of the cluster, and a projection axon with few local collaterals. This contrasts with the intranuclear collateralization observed in other ITC clusters (Geracitano et al., 2007; Asede et al., 2021b). ITCav neurons are reciprocally connected to BLA principal cells (Mańko et al., 2011; Winters et al., 2017; Gregoriou et al., 2021) and are activated by inputs carried by the external capsule (cortical axons) and internal capsule (thalamic axons) (Mańko et al., 2011). Early studies defined substantia inominata and diagonal band of Broca in the basal forebrain as a major projection target of the ITCav, suggesting a role in emotional control of attention (Paré and Smith, 1993, 1994). In addition to medial and extended amygdala, ITCav neurons project to all three subdivisions of the central amygdala (Mańko et al., 2011; Gregoriou et al., 2019). Axons from reconstructed neurons in the ITCav cluster approach the ITCdm and ITCL. Also, electrical stimulation of the external capsule (Mańko et al., 2011) and intermediate capsule (Busti et al., 2011) near the ITCL and ITCdm respectively, evoke inhibitory synaptic responses in ITCav neurons. However, direct connectivity between these three clusters has not yet been demonstrated. In summary, ITCav neurons are broadly connected to amygdala nuclei and project to distant cholinergic centers, such as the basal forebrain.

ITCvm

ITCvm is the posterior part of the previously named “main” ITC cluster. ITCvm neurons are activated by neurons in BA (Blaesse et al., 2015; Hagihara et al., 2021), medial amygdala (MeA) (Westberry and Meredith, 2016, 2017; Biggs and Meredith, 2022), and dorsomedial PFC, which includes the prelimbic region (Adhikari et al., 2015). Similar to ITCav neurons, ITCvm neurons innervate BLA as well as CeM but have less influence on central lateral (CeL) and central capsular (CeC) amygdala nuclei. ITCvm cells are also bidirectionally connected with ITCdm (Mańko et al., 2011; Hagihara et al., 2021), and the activity balance between the two clusters mediates a switch in fear state (Hagihara et al., 2021).

ITCdm

Neurons of the ITCdm have dendritic branches that parallel the intermediate capsule, with asymmetrical dendritic trees and axonal arbors in the lateromedial plane in guinea pig (Royer and Paré, 2002). Similar to LA neurons, ITCdm neurons receive thalamic and cortical inputs that convey auditory and somatosensory information during fear learning (Asede et al., 2015; Strobel et al., 2015). They also receive excitatory input relaying information related to contextual fear from the BMA (Rajbhandari et al., 2021). ITCdm neurons are inhibited by neurons in ITCL and likely ITCav as discussed above (Mańko et al., 2011; Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021). Furthermore, ITCdm is reciprocally connected with the ITCvm (Mańko et al., 2011; Hagihara et al., 2021), and BLA, which also drives feedforward inhibition of CeL neurons by ITCdm (Royer et al., 1999; Amir et al., 2011). 3D reconstruction of ITCdm neurons demonstrates axons projecting to the basal forebrain (Busti et al., 2011).

Functional significance of intracluster and intercluster connectivity

Consistent with the extensive axon collateralization within clusters, there is relatively high connectivity between ITCs within clusters. For example, 14% of ITCdm pairs are connected, but bidirectional connections are very rare (Geracitano et al., 2007). ITCav/ITCvm neurons also exhibit intracluster connectivity (Mańko et al., 2011; Winters et al., 2017; Gregoriou et al., 2019). ITCap neurons have intracluster collateralization, but it is unknown whether ITC pairs are connected (Asede et al., 2021b). Lateral inhibition within ITC clusters may enhance response selectivity to the sensory, contextual, or internal information as proposed in computational models of primary sensory cortex (Churchland and Sejnowski, 1994). Intracluster connectivity may also tune the strength of inhibition delivered by ITCs to their targets, as highlighted in a computational model that revealed that increased inter-ITC strength depresses firing rates of individual ITC neurons (Li et al., 2011). Connections between ITCdm neurons also display short-term plasticity, which has been proposed as a mechanism to promote amygdala network stability (Geracitano et al., 2007). Upon high-frequency stimulation, the success rate for synaptic transmission between ITCs increases, decreases, or remains constant: a property that is determined by the presynaptic neuron rather than the postsynaptic target.

ITC cluster interconnectivity regulates amygdala-dependent behavior. ITCdm neurons have monosynaptic bidirectional connections with ITCvm (Lopez de Armentia and Sah, 2004; Busti et al., 2011; Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021; Hagihara et al., 2021). The connection from ITCdm to ITCvm is formed by a specific subclass of ITC neuron defined by axon projection and activity pattern in response to fear conditioning (Busti et al., 2011). The reciprocal connectivity between ITCdm and ITCvm contributes to the differential activation of these two clusters in different fear states (Busti et al., 2011; Hagihara et al., 2021). A switch from inhibition predominantly from ITCdm to ITCvm to inhibition predominantly from ITCvm to ITCdm is integral to switching from a high-fear state to a low-fear state (Hagihara et al., 2021).

Neurons in ITCav (Mańko et al., 2011) and ITCL (Mańko et al., 2011; Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021) also form synaptic connections onto ITCdm neurons. The functional significance of other intercluster pairs has not yet been investigated, but it is likely that shifts in the balance of inhibition between clusters driven by sensory or internal-state information facilitates the engagement of emotionally salient behaviors.

ITCs in fear behavior

Fear learning is a survival tool that promotes the avoidance of threatening environmental stimuli. It is equally important to be able to extinguish fear of stimuli that are found, through experience, to be nonthreatening. Failure to extinguish fear memories or aberrant fear memory generation is the hallmark of anxiety disorders (Shin and Liberzon, 2010).

The neural substrates of fear learning are often assessed using classical fear conditioning and extinction paradigms (Maren, 2005). During fear conditioning, subjects learn to associate a neutral sensory stimulus (conditioned stimulus [CS]), such as tone, with an aversive stimulus (unconditioned stimulus [US]), such as mild foot shock. Subsequent presentation of the CS alone elicits a fear response because it has acquired an aversive property. This conditioned fear can be suppressed when the CS is repeatedly presented alone in a different context, a process called fear extinction (Quirk and Mueller, 2008; Herry et al., 2010). In the canonical processing model of fear learning, sensory inputs to LA representing the US and CS are integrated and strengthened, and this increased response is propagated through BA, which directly drives CeM. In addition, the enhanced LA representation of CS results in increased excitatory input to subpopulations of CeL neurons (CeL-on), which inhibit other subpopulations of CeL neurons (CeL-off), leading ultimately to disinhibition of CeM output neurons and fear responses to the CS (Paré and Duvarci, 2012). In addition to strengthening excitatory auditory and somatosensory inputs from the thalamus and cortex to LA, associative fear learning is dynamically regulated by stimulus-specific activation of distinct disinhibitory microcircuits (Wolff et al., 2014; Krabbe et al., 2018; Hagihara et al., 2021). Fear extinction engages an active inhibitory process to suppress plastic changes induced by fear conditioning (Pape and Paré, 2010; Krabbe et al., 2018). ITCs play key roles in both processes and the transition between fear states that engage them.

Fear conditioning

ITCdm is wired to powerfully regulate fear. The complex circuitry through which ITCs contribute to fear conditioning is summarized in Figure 3A. Similar to LA neurons, ITCdm neurons also receive thalamic and cortical inputs that convey auditory and somatosensory information during fear conditioning (Asede et al., 2015; Strobel et al., 2015). ITCdm cells may also disinhibit the LA principal cells, to promote fear-related plasticity during fear learning. In vivo 2-photon Ca2+ imaging performed in head-fixed mice directly demonstrated that most ITCdm neurons respond to foot shock (US) with highly correlated neural activity (Hagihara et al., 2021). ITCdm neurons receive direct inputs from the thalamic PIN (Asede et al., 2015), which (together with insular cortex) relays foot shock information to the amygdala during fear conditioning (Romanski et al., 1993; Shi and Cassell, 1998). Furthermore, thalamic inputs to ITCdm neurons undergo an association-specific decrease in sensory input strength following fear learning (Asede et al., 2015). Fear conditioning and retrieval are associated with lasting decreases in the strength of thalamic inputs to ITCdm neurons, via changes at both presynaptic (increased PPR) and postsynaptic (decreased AMPA/NMDA ratio) sites (Asede et al., 2015). The decrease in AMPA/NMDA ratio is due to a reduction in the density of AMPARs at PIN/MGm-ITCdm synapses with fear memory (Seewald et al., 2021). This is in contrast to fear-mediated plasticity at thalamus-to-LA synapses, in which fear conditioning is associated with an increase in synapse strength, associated with insertion of AMPARs (Rumpel et al., 2005; Yeh et al., 2006; Sigurdsson et al., 2007). The large ITCs that encapsulate the ITCdm cluster also receive direct input from PIN and are activated by foot shock (Bienvenu et al., 2015).

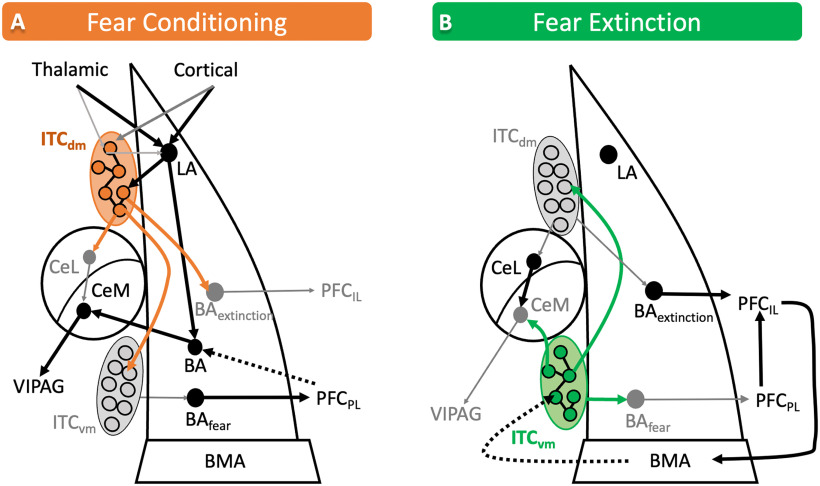

Figure 3.

ITCs shift amygdala circuits to facilitate fear learning and fear extinction. A, Fear conditioning is associated with long-lasting dampening of sensory thalamic and cortical drive to ITCdm neurons, which suppresses ITCdm-mediated feedforward inhibition to promote fear-related plasticity in LA. This results in increased synaptic drive from LA to ITCdm neurons, which facilitate fear learning. During fear memory retrieval, increased activity in ITCdm drives inhibition of extinction-promoting neurons in the ITCvm cluster and BA. ITCdm neurons could also inhibit extinction-promoting (PKCδ) neurons in the CeL. This leads to disinhibition of the CeM and the corresponding activation of fear-promoting brainstem structures. ITCdm also signals via a disynaptic mechanism through the BA to inhibit infralimbic mPFC inputs. B, During fear extinction, ITCdm is inhibited by the ITCvm, which assumes the role of modulating amygdala circuits. Consequently, ITCvm inhibits the fear-promoting CeM and BA neurons projecting to the mPFCPL. In concerted fashion, fear extinction enhances PL to IL drive that further activates the IL cortex. IL-mediated top-down control of the amygdala for extinction is speculated to occur through the BMA and ITCs. Baextinction, BA neurons that project to the infralimbic mPFC; BAfear, BA neurons that project to the mPFCPL; VlPAG, ventrolateral periaqueductal gray of the midbrain. Dashes indicate speculative networks. Gray lines/circles represent decreased function.

An intriguing question is whether the function of large ITCs and ITCdm neurons is additive or oppositional during associative fear learning. This question stems from the fact that, although both large ITCs and ITCdm neurons receive information about noxious sensory stimuli, axonal boutons of ITCdm neurons are typically found in close apposition with CaMKII-positive dendrites, suggesting they synapses onto BLA principal neurons (Asede et al., 2015), whereas large ITCs make asymmetric shaft synapses onto BLA inhibitory interneurons (Bienvenu et al., 2015).

In contrast to the decrease in thalamic drive to the ITCdm neurons following fear learning, LA projections to the ITCdm neurons are strengthened during fear conditioning (Huang et al., 2014). LA-ITCdm synapses undergo LTP that leads to a persistent increase in AMPAR/NMDAR ratio (Huang et al., 2014). Finally, thalamic PIN/MGm inputs to ITCap neurons are strengthened by fear conditioning (Asede et al., 2021b), whereas thalamic PIN/MGm inputs to ITCdm neurons are depressed (Asede et al., 2015). These paradoxical findings await future experiments for resolution but support the emerging theme of parallel ITC-mediated feedforward inhibitory loops even within individual ITC clusters. Subpopulations of ITC neurons may receive different afferent information and impinge on different populations of target neurons and serve distinct functional roles.

Fear extinction

Fear extinction is thought to depend on a competing memory trace that recruits an inhibitory process to suppress fear (Fig. 3B). The network mediating fear extinction involves a complex interplay between the amygdala and mPFC (Maren, 2005). ITCs are a critical part of the amygdala microcircuit involved in fear extinction since selective ablation of ITC neurons after extinction training results in spontaneous fear reemergence (Likhtik et al., 2008). Within BLA, there are neurons called “fear neurons” that increase their firing rate during the presentation of the fear CS, and neurons called “extinction neurons” that respond to the omission of the US shock after the CS is presented during fear extinction training (Herry et al., 2008). Fear expression is determined in part by CS responsiveness of fear neurons in the BLA, which correlates with the activity of fear-promoting neurons in prelimbic PFC (mPFCPL) (Senn et al., 2014). BLA fear neurons preferentially project to the fear-promoting mPFCPL, while extinction neurons project predominantly to the extinction-promoting infralimbic PFC (mPFCIL) (Sierra-Mercado et al., 2011; Senn et al., 2014), providing a bottom-up signaling stream to the cortex conveying CS information.

The role of ITCs in fear extinction has long been under debate. Initially, they were thought to be the target of the mPFCIL that mediates cortical control over amygdala-driven fear responses (Ehrlich et al., 2009). Consistent with this hypothesis, BLA-evoked synaptic responses in ITCvm neurons are enhanced and have an increased AMPA/NMDA ratio after extinction learning (Amano et al., 2010). This increase in the strength of the BLA-ITCvm synapse is correlated with increased inhibition of CeM and requires the activity of mPFCIL during training (Amano et al., 2010). Interestingly, although electrical stimulation of mPFCIL is capable of evoking action potentials with short latency in juxtacellularly recorded ITCdm and ITCvm neurons in vivo (Amir et al., 2011), the axon projections from mPFCIL are sparse at best in ITC nuclei (Pinard et al., 2012; Dobi et al., 2013; Adhikari et al., 2015; Strobel et al., 2015), and optogenetic stimulation of mPFCIL terminals fails to evoke synaptic responses in ITCvm neurons (Strobel et al., 2015), which demonstrates that ITCs are not directly connected to mPFCIL. It is speculated that ITCs may be driven during fear extinction by the mPFCIL by a disynaptic mechanism either from BLA or BMA; However neither possibility has been conclusively proven (Adhikari et al., 2015). One explanation for the earlier findings may be off target injection sites or that electrical activation of mPFCIL neurons inadvertently activated the mPFCPL, which continues to demonstrate connectivity with ITCs (Adhikari et al., 2015). Although it remains unclear how cortical drive shapes ITC function, evidence is mounting that ITCs provide the initial switch in BLA circuits to convey fear/extinction state of the amygdala to the PFC (Hagihara et al., 2021).

ITCdm is preferentially activated during fear expression, whereas extinction training and extinction retrieval activate ITCvm (Busti et al., 2011), demonstrating the opposing and distinct roles of these ITC clusters (Busti et al., 2011). In line with this, a recent study that measured Ca2+ activity in ITCdm and ITCvm neurons during different phases of fear and extinction found that a large fraction of fear neurons were detected in ITCdm, whereas extinction neurons were overrepresented in ITCvm (Hagihara et al., 2021). Furthermore, ITCvm neurons selectively target PL-projecting, whereas ITCdm neurons target IL-projecting BLA neurons (Hagihara et al., 2021). This allows these two clusters to facilitate the transfer of appropriate state-dependent signals from amygdala circuits to the cortex. Further support for the hypothesis that ITC clusters are responsible for selecting fear- versus extinction-promoting neuronal ensembles is that artificial activation of the ITCdm during extinction training impairs extinction memory formation, as does inhibition of ITCvm. This implies that the balance of activity in these ITC clusters is a key component in selecting the appropriate state-dependent amygdala circuits.

The opposing roles of ITCvm and ITCdm are caused in part by the reciprocal inhibitory monosynaptic connections between these clusters (Jimenez and Maren, 2009; Asede et al., 2021a; Hagihara et al., 2021). Since the ITCvm inhibits ventrolateral-periaqueductal gray-projecting neurons in CeA (Tovote et al., 2015; Hagihara et al., 2021), a pathway that promotes physiological manifestations of fear, activity switching of ITCs during fear extinction helps ITCs inhibit fear promoting amygdala structures directly. However, it is possible that the mPFCIL uses an indirect mechanism to further enhance ITCvm drive onto the CeM or interacts with the CeM in an ITC-independent manner through other amygdala nuclei.

Together, these studies show that fear and extinction are regulated by the dynamic transformation of the balance of power between ITCvm and ITCdm.

ITCs in social behavior

There is emerging evidence that ITCs are also involved in social behavior. KO of Tshz1, a protein required for the maturation and survival of ITCs, in the ventral forebrain results in deficits in social behavior in addition to fear behaviors (Kuerbitz et al., 2018). The Tshz1 KO mice spent less time investigating other mice and were passive when being investigated. During social buffering, which is characterized by decreased stress in the presence of another conspecific rat during the presentation of an aversive CS after fear conditioning, the activity of ITCL neurons increases as shown by c-fos expression (Minami et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022). The authors propose that the anterior olfactory nucleus indirectly suppresses the LA by activating the ITCL to promote social buffering. Also, the activity of the ITCvm cluster as measured by c-fos expression is inversely correlated with sociability and social approach (Dorofeikova et al., 2021). These studies suggest that differential activation of ITC clusters may facilitate distinct aspects of social behavior similar to the balance of activity between ITCdm and ITCvm in fear and extinction.

Chemosensory information is central to rodent social life, and the MeA evaluates the relevance of social smells (see Petrulis, 2013). Chemosensory signals from the vomeronasal organ, the main and accessory olfactory bulbs, and the nasal epithelium project to the anterior MeA, which in turn projects to the posterior medial amygdala (MeP) (Maras and Petrulis, 2010; Been and Petrulis, 2011). In addition to the direct projection from MeA to MeP, chemosensory associations relevant for avoiding predators and engaging in social interactions (including mating behaviors) are processed via a triangular feedforward inhibitory loop from MeA to ITCvm to MeP (Westberry and Meredith, 2016, 2017; Biggs and Meredith, 2022). In hamsters, ITCvm neurons respond to chemosensory stimulation, as measured by immediate early gene expression (Westberry and Meredith, 2016, 2017; Biggs and Meredith, 2022). ITCvm neurons receive monosynaptic connections from MeA and send monosynaptic connection to the MeP (Westberry and Meredith, 2016, 2017; Biggs and Meredith, 2022). Both MeP and ITCvm project to basal forebrain regions, such as the preoptic area and hypothalamus, which engage normal reproductive and social behavioral repertoires (Paré and Smith, 1993, 1994; Maras and Petrulis, 2010; Been and Petrulis, 2011). This dual projection may function as another triangular feedforward inhibitory regulatory node for ITCs.

ITCs and internal state

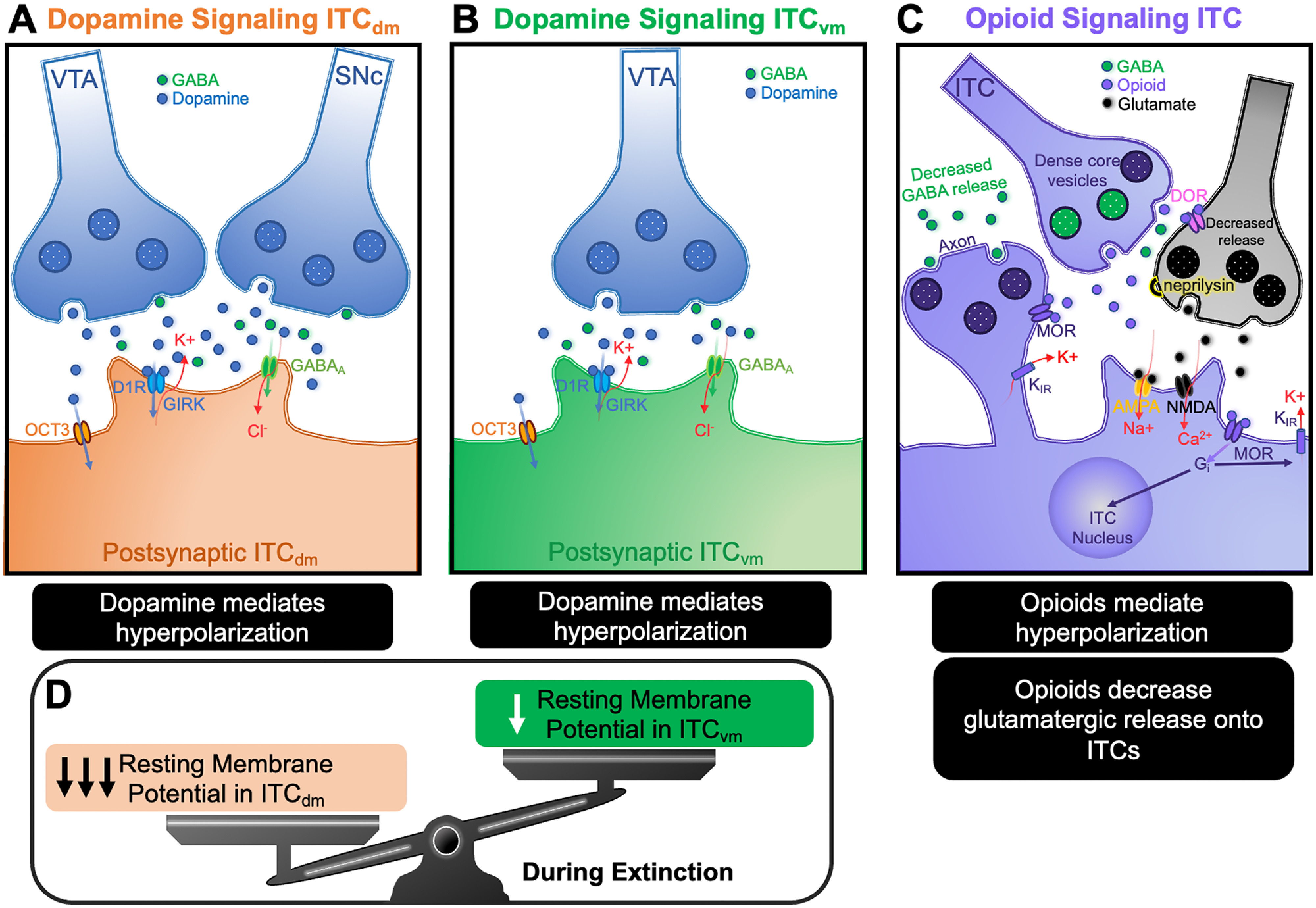

The ITCs are tightly controlled by the dopamine, μ-opioid, and other neuromodulatory systems (Fig. 4) (Fuxe et al., 2003; Marowsky et al., 2005; Jacobsen et al., 2006; Blaesse et al., 2015).

Figure 4.

Dopamine and opioid signaling hyperpolarizes ITCs. Dopamine acting via D1R hyperpolarizes ITCs by activating GIRK channels. This hyperpolarization is further regulated by organic cation 3-mediated dopamine clearance as well as GABA corelease. There appears to be differences in dopamine release and responses between clusters with the notable discovery that the ITCdm neurons (A) receive dopaminergic inputs from VTA and SNc, whereas VTA is the only source of dopamine to ITCvm neurons (B) during fear extinction. The consequence of unbalanced dopamine transmission to the clusters can promote shifts in ITC activity. This is shown where ITCdm are disproportionately hyperpolarized during fear extinction promoting ITCvm activity (D). C, Opioid signaling involves axo-axonic communication that directly modulates both presynaptic and postsynaptic activity of ITCs. Opioid release from dense core vesicles from ITCs provides axo-axonic communication to local glutamatergic neurons and promotes decreased glutamatergic drive onto ITCs. It also functions to induce ITC membrane hyperpolarization via a Gi-coupled K-inward rectifying channel. Opioid signaling was also shown to reduce GABA release from ITCs. Neprilysin is an enzyme that mediates opioid clearance from the synaptic cleft and regulates opioid signaling at the ITC interface. OCT3, Organic cation 3; DOR, δ-opioid receptor; MOR, μ-opioid receptor; RMP, resting membrane potential; GIRK, G-protein-coupled inward rectifying channels; Gi, G-protein inhibitory subunit; KIR, inward rectifying potassium channel.

Dopamine

Dopamine modulates brain circuits to facilitate reward prediction, stimulus salience, motor control, and motivation (Schultz, 1997). Dopamine is released from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) of the midbrain. Dopaminergic projections from both of these areas convey emotionally relevant reward-prediction-error signals to the BLA, CeA, and ITC clusters (Lamont and Kokkinidis, 1998; Greba and Kokkinidis, 2000; Greba et al., 2001). In the absence of emotionally salient stimuli, the amygdala output neurons are quiescent as a result of tonic cortically driven inhibition. Dopamine flips the switch from cortical inhibitory control to a disinhibited state, promoting the expression of fear behaviors and the learning of associations between emotional stimuli (Luo et al., 2018).

Dopamine facilities this transition by altering neuron excitability, synaptic transmission, and plasticity at multiple points along the amygdala's information-processing stream (de la Mora et al., 2010). Dopamine, acting through D2R on local inhibitory neurons within the LA, suppresses feedforward inhibition and thus promotes LTP of sensory thalamic inputs to LA principal neurons (Bissière et al., 2003). Dopamine also suppresses mPFC-driven inhibition of sensory inputs onto BLA principal neurons (Rosenkranz and Grace, 2001, 2002).

Dopaminergic axons innervate ITCs profusely (Asan, 1997; Fuxe et al., 2003), suggesting that ITCs may contribute to dopamine-induced emotional state transitions (Marowsky et al., 2005; Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021; Hagihara et al., 2021). However, ITC clusters are not uniformly innervated by dopaminergic terminals. This feature is preserved across species, including primates (Zikopoulos et al., 2016). Dopamine innervation is more prominent in ITCdm than ITCvm. ITCdm receives dopamine projections from both VTA and SNc, whereas ITCvm only receives projections from VTA (Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021). This differential dopamine innervation of ITCs could enable selection of specific subsets of emotional associations by adjusting the relative impact of inhibition by different ITC clusters.

Dopamine regulates ITC clusters and their targets through several mechanisms. Dopamine activation of dopamine 1 receptors (D1Rs) hyperpolarizes ITC resting membrane potential and decreases ITC spike firing by activating a G-protein-coupled inward-rectifying potassium channel (Royer and Paré, 2002; Marowsky et al., 2005; Balleine and Killcross, 2006; Gregoriou et al., 2019; Asede et al., 2021b; Biggs and Meredith, 2022). Dopamine has been demonstrated to decrease intracluster lateral inhibition in ITCav (Gregoriou et al., 2019), and to decrease presynaptic GABA release at ITCL-to-ITCdm and ITCdm-to-ITCvm synapses (Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021). D1R-mediated hyperpolarization decreases action potentials driven in ITCs by excitatory afferents and also decreases the probability of GABA release from ITCs (Marowsky et al., 2005). Therefore, dopamine decreases feedforward inhibition by ITC clusters both by decreasing their firing via hyperpolarization and by decreasing GABA release. Finally, dopamine signaling in ITC clusters appears regulated by the organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3). This recently described high-capacity transporter for dopamine and other monoamines is expressed at high density in ITCs in very close proximity to D1Rs and allows rapid termination of dopamine signaling (Hill and Gasser, 2013).

Dopamine-mediated suppression of feedforward inhibition has been demonstrated at multiple ITC synapses. Dopamine decreases cortically driven ITCL-mediated feedforward inhibition of BLA neurons and decreases BLA-evoked ITCdm-mediated feedforward inhibitory responses in CeA neurons (Marowsky et al., 2005). Similarly, dopamine decreases MeA-driven feedforward inhibition of MeP by ITCvm, thus regulating social behavior (Biggs and Meredith, 2022). ITC suppression by dopamine and the resulting disinhibition of amygdala circuits may be one of the key mechanisms of salience processing within the amygdala. Since dopamine release in the amygdala is proportional to the stressor intensity (Y. Wang et al., 2012), dopamine concentration may be a proxy of emotional salience for ITCs. Weak fear conditioning (less salient) and the correspondingly low level of dopamine release activates D4Rs in LA principal cells and induces LTD of ITCdm neurons, and this is reversed with strong fear conditioning (more salient) (Kwon et al., 2015).

During fear conditioning, footshock (US) increases VTA dopaminergic drive to BA neurons and inhibition of this pathway suppresses fear memory (Tang et al., 2020). Although both ITCdm and ITCvm neurons are innervated by VTA dopaminergic afferents, ITCdm neurons are preferentially activated by footshock, and activity within this cluster is correlated with footshock responses during fear conditioning (Hagihara et al., 2021). However, it is unclear whether footshock also increases dopaminergic drive to ITCdm neurons during fear conditioning the way it does with BA neurons. If so, it would not support our current understanding of ITCdm-mediated disinhibition of CeM during fear retrieval. While the precise role of D1R activation in ITCs is still poorly understood, a combination of differential relative afferent drive and impact of dopamine on different ITC clusters by fear-promoting and extinction-promoting stimuli, combined with intercluster inhibition, may explain it.

As discussed earlier in this review, a shift in activity balance from ITCdm to ITCvm is a key step enabling fear extinction learning. Dopamine afferents responding to the unexpected absence of the US decrease ITCdm inhibition of ITCvm, allowing ITCvm to inhibit CeM-mediated fear behaviors (Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021). In addition to dopamine-mediated suppression of inhibitory interactions between ITC clusters, dopaminergic afferents also control ITCs by coreleasing GABA to mediate rapid, direct inhibition (Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021). Finally, early extinction training augments both GABA corelease onto ITCdm and dopamine-mediated suppression of ITCdm to ITCvm inhibition.

Neuropsychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia and PTSD, are characterized by dopamine signaling dysfunction (McGowan et al., 2004), which likely affect ITC function. In humans with schizophrenia, postmortem pathology studies demonstrate that dopaminergic axon terminals innervating ITC clusters appear to have decreased dopamine synthesis (dopamine β-hydroxylase activity) (Markota et al., 2014), suggesting that inadequate dopamine signaling to ITCs may disinhibit amygdala circuits and contribute to symptoms of paranoia and anxiety. In rats, in vivo focal application of dopamine antagonist into the ITCdm cluster produced anxiolytic effects (de la Mora et al., 2005). Manipulating the actions of dopamine signaling to ITCs may be an intriguing treatment option for anxiety. Recently, a technique targeting D4R on ITCs for treating PTSD was patented (Kim et al., 2018).

Opioids

Endogenous opioid peptides and their cognate inhibitory (Gαi/Gαo) GPCRs are widely expressed throughout the nervous system and are particularly concentrated in pain pathways and brain regions encoding reward and motivation. Within the amygdala, different classes of opiate receptors are expressed by specific nuclei, types of neurons, and classes of synapses. For example, high levels of δ opiate receptors are expressed in BLA and CeA (Mansour et al., 1994; D. Wang et al., 2018), and BLA terminals projecting to BNST (relevant for anxiety) express kappa opiate receptors (Crowley et al., 2016). Amygdala opioid transmission through μ-opioid receptor activation is relevant for emotional memory consolidation, affective modulation of pain perception, reward valuation, and stress adaptation (for review, see Bodnar, 2014).

ITC clusters express some of the highest densities of μ-opioid receptors within the amygdala (Jacobsen et al., 2006; Poulin et al., 2006; Likhtik et al., 2008; Amir et al., 2011; Busti et al., 2011). ITC opioid expression is so characteristic that a toxin targeting μ-opioid expressing neurons was created to ablate ITCs and study their dysfunction (Likhtik et al., 2008). A subset of CeA neurons also express μ-opioid receptors (Zhu and Pan, 2004; Cabral et al., 2009). ITCs and CeA also express high levels of Met-enkephalin, an endogenous agonist for both the μ-opioid and δ-opioid receptors (Poulin et al., 2006, 2008; Winters et al., 2017). The expression level of enkephalin varies topographically within ITC clusters, conveying specificity to the microcircuits engaged by opiates. For example, in rats, enkephalin innervation is higher in rostromedial of ITCvm and ITCav than rostrolateral. This is complementary to TH-expressing dopaminergic terminals, which innervate rostrolateral more heavily than rostromedial (Jacobsen et al., 2006).

Endogenous enkephalin regulates ITC function through multiple mechanisms. As with dopamine, ITCs undergo membrane hyperpolarization upon μ-opioid binding (Winters et al., 2017; Biggs and Meredith, 2022). This hyperpolarization, which was demonstrated in the ITCav and ITCvm clusters, is mediated by a signaling cascade initiated by activation of inhibitory g-protein and resulting in inward rectifying potassium channel activation (Blaesse et al., 2015; Winters et al., 2017; Biggs and Meredith, 2022) (Fig. 4C). met-enkephalin is concentrated in dense-core vesicles in ITC axon terminals, including in a subset of terminals directly opposed to glutamatergic presynaptic terminals that synapse on ITC dendrites. This arrangement suggests that met-enkephalin released from ITCs inhibits glutamatergic input onto ITC dendrites, as well as inhibiting GABAergic transmission both between ITCs within a cluster and from ITCs to their projection targets (Winters et al., 2017). Indeed, in ITCav, endogenously released opiates and exogenous activation of μ-opioid receptor have been demonstrated to inhibit both intracluster GABAergic synapses and glutamatergic transmission from BLA to ITCav (Winters et al., 2017). In addition, exogenous met-enkephalin inhibits ITCav-to-BLA and ITCav-to-CeM synapses (Gregoriou et al., 2021). Furthermore, the μ-opioid receptor agonist, DAMGO, inhibits GABAergic transmission from ITCvm to CeM (Blaesse et al., 2015).

Endogenous opiate regulation of other ITC clusters has not been investigated but is likely mechanistically similar. Regardless, like the case for dopamine modulation of ITCs, the behavior and context-specific engagement of individual ITC clusters combined with differential innervation by enkephalin terminals will determine the relative effect of endogenous opiates on ITC cluster activity and net behavioral outcome. In summary, opiates disinhibit ITC targets by decreasing the excitability of the ITCs themselves, their afferent glutamatergic drive, lateral inhibition from neighboring ITCs within the cluster, and GABA transmission onto their projection targets. Furthermore, this endogenous-opiate-mediated decrease in ITC feedforward inhibition is dynamic because of the combination of the rapid release of opiates with moderate synaptic stimulation and degradation by a zinc-dependent metalloprotease, neprilysin (Gregoriou et al., 2021).

Altered opiate signaling in ITCs may play a role in disease. Studies in humans have demonstrated that, during PTSD and anxiety, μ-opioid expression in the amygdala is reduced (Liberzon et al., 2007; Nummenmaa et al., 2020), suggesting that receptor dysregulation within ITCs could contribute to anxiety phenotypes. Furthermore, ITCs dynamically downregulate their μ-opioid receptor expression in response to severe stress over a period of at least 24 h after stress exposure (Gouty et al., 2021). Like stress-mediated μ-opioid receptor changes, release of endogenous opiates in response to chronic pain and chronic consumption of exogenous opiates likely alters the expression of μ-opioid receptor on ITCs, as they have been demonstrated to do in other key brain regions in the reward and pain pathways (Lutz and Kieffer, 2013).

Opioid signaling in ITCs plays a role in reward salience. During opiate withdrawal in rats, neprilysin, the predominant peptidase in the degradation of enkephalin in ITCav, is enhanced. This reduces ITC-mediated feedforward inhibition of BLA and leads to increased BLA stimulation of targets, such as NAc altering reward salience (Gregoriou et al., 2020, 2021).

Other neuropeptides

While dopamine and opioid receptors are prominently expressed throughout the ITC clusters and have been used as histologic markers, ITCs also express other neuromodulatory receptors that are less studied. A few neuromodulators with documented actions on ITCs are discussed below.

Norepinephrine plays an integral role in the neurobiological response to stress. Exposure to stressful stimuli increases norepinephrine levels via activation of locus coeruleus neurons that project throughout the brain, including dense innervation of the amygdala (Fallon et al., 1978; Silberman et al., 2010). Norepinephrine signals through α- and β-adrenergic GPCRs. Bilateral BLA microinjection of the selective β3-adrenoceptor (AR) agonist BRL37344 reduces anxiety-like behaviors in an open field and the elevated plus maze and enhances ITCL-evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents in BLA neurons with no effect on local BLA GABAergic inhibition (Silberman et al., 2010). This suggests that increases in ITCL-mediated inhibition by β3-AR activation may contribute to the anxiolytic profile of β3-AR agonists. The effects of β3-AR activation on other ITC clusters have not been investigated but may also contribute to anxiolysis.

ITCs express pituitary adenylyl cyclase receptor 1 (PAC1R), which when bound by the ligand pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), influences fear memory consolidation (Rajbhandari et al., 2021). BMA afferents to the ITCdm corelease glutamate and PACAP; and deletion of the PAC1R from ITCdm neurons led to increased fear generalized and decreased extinction in males and decreased fear acquisition in females, suggesting a possible sexually dimorphic role for PACAP within amygdala circuits (Rajbhandari et al., 2021).

Neuropeptide S (NPS), acting through the Neuropeptide S receptor (NPSR), is anxiolytic and facilitates the extinction of condition fear when infused directly into the amygdala (Jungling et al., 2008; Ren et al., 2013). NSPR is highly expressed in ITC clusters and moderately in cortical nuclei of the extended amygdala, but not in BLA (Xu et al., 2007). NPSR is located on presynaptic terminals of LA principal neurons that project to ITCdm and, when bound by NPS, enhances glutamatergic input to ITCdm neurons (Jungling et al., 2008). In rats, ITCdm neurons are recruited via NPSR binding, which increases ITC-mediated feedforward inhibition of the CeL (Ren et al., 2013). Another study found that NPS binding to NPSR in ITCs inhibits nociceptive processing of CeA neurons in a pain state, but not under normal conditions (Medina et al., 2014). In contrast to ITCdm, ITCL neurons do not display changes in glutamatergic drive following exogenous NPS administration, suggesting cluster- or input-specific NPS responses (Jungling et al., 2008).

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y1 receptor (NPYY1R) and Galanin receptor 2 (GALR2) interact in several regions of the limbic system. GALR2 enhances NPYY1R-mediated anxiolytic actions in the open field and elevated plus maze (Narvaez et al., 2015). Increased density of GALR2/NPYY1R heteroreceptor complexes in the ITCdm, following GALR2 and NPYY1R coactivation is correlated with reduced anxiety (Narvaez et al., 2018).

In summary, ITCs orchestrate behavioral state-dependent regulation of fear and other emotionally charged behaviors through their expression of receptors for a wide range of neuromodulators and neuropeptides. The dysregulation of these neuromodulatory systems is classically associated with various neuropsychiatric disorders.

ITCs' role in social and emotional disorders

Studies involving selective ITC lesions (Likhtik et al., 2008; Kuerbitz et al., 2018) demonstrate that ITC dysfunction results in fear extinction deficits as well as depression-like phenotypes and impaired social interaction (i.e., increased passivity). In mice, the deletion of Tshz1, which is critical for normal ITC development, results in symptoms similar to those observed in depressive disorders in human patients with distal 18q deletions that include the Tshz1 locus (Daviss et al., 2013; Kuerbitz et al., 2018). Furthermore, loss of Tshz1 resulted in downregulation of other known regulators of neuronal migration, such as ErbB4, a receptor tyrosine-protein kinase that has been implicated in schizophrenia (Law et al., 2007; Mei and Nave, 2014). Although it is currently unknown whether ErbB4 expression in ITCs is important for regulation of emotional response, deletion of ErbB4 disrupts synaptic plasticity of thalamic inputs to ITCdm neurons (Asede et al., 2021b), and neuregulin1-ErbB4 disruption in ITCs impairs feedforward inhibition of CeM neurons, suppressing fear output (Chen et al., 2021).

Pituitary adrenocortical axis plays a key role in stress response. PAC1/PACAP signaling in ITCs is dysregulated in PTSD (Rajbhandari et al., 2021). Corticosterone is elevated in PTSD and other mental illnesses. Corticosterone treatment precipitates PTSD-like enhancements in fear learning and blocks plasticity of ITCdm neurons, thus allowing the consolidation and enhancement of fear responses (Kwon et al., 2015; McCullough et al., 2016). In summary, ITCs are involved in behaviors that are often dysregulated in psychiatric disorders, which makes them excellent targets for therapeutic manipulations.

In conclusion, evidence discussed here highlights the pivotal role of ITCs in regulating information flow at many nodes in the parallel processing streams of the amygdala circuitry. On the input side, ITCs receive primary sensory and higher-order association information, which drives their feedforward inhibitory gating of BLA. On the output side, BLA drives the medial ITC clusters, which in turn deliver feedforward inhibition to CeM. ITCs are also regulated by neuromodulators, which represent internal state, and they convey this signal to the CeA, BLA, and PFC. Adding to the complexity, the clusters also inhibit each other. The inhibitory interaction between medially located ITC clusters serves as a unique regulatory motif that facilitates the switch between high- and low-fear states (Hagihara et al., 2021). ITCdm dominates during fear association, whereas ITCvm dominates during fear extinction. It is still unclear how other ITC clusters are recruited during amygdala-dependent behaviors.

Another key question is how ITCs versus local BLA GABAergic neurons coordinate and shape the activity of BLA principal cells during behavior. Do these two GABAergic populations function synergistically or exert dynamic effects in different behavioral states? Tools that allow simultaneous manipulation and recording of activity of different neuronal populations in behaving animals (Wolff et al., 2014; Hagihara et al., 2021) will provide valuable insights. The unique genetic profile, neuroreceptor expression, and behavioral-state-dependent function of ITCs make them a potential target for pharmacological manipulation of fear and anxiety-related disorders.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Max Planck Institute for Neuroscience. We thank Timothy Holford for comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Adhikari A, Lerner TN, Finkelstein J, Pak S, Jennings JH, Davidson TJ, Ferenczi E, Gunaydin LA, Mirzabekov JJ, Ye L, Kim SY, Lei A, Deisseroth K (2015) Basomedial amygdala mediates top-down control of anxiety and fear. Nature 527:179–185. 10.1038/nature15698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP (1992) The amygdala: neurobiological aspects of emotion, memory, and mental dysfunction. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy-Aksel A, Gall A, Seewald A, Ferraguti F, Ehrlich I (2021) Midbrain dopaminergic inputs gate amygdala intercalated cell clusters by distinct and cooperative mechanisms in male mice. Elife 10:e63708. 10.7554/Elife.63708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Unal CT, Paré D (2010) Synaptic correlates of fear extinction in the amygdala. Nat Neurosci 13:489–494. 10.1038/nn.2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir A, Amano T, Paré D (2011) Physiological identification and infralimbic responsiveness of rat intercalated amygdala neurons. J Neurophysiol 105:3054–3066. 10.1152/jn.00136.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asan E (1997) Ultrastructural features of tyrosine-hydroxylase-immunoreactive afferents and their targets in the rat amygdala. Cell Tissue Res 288:449–469. 10.1007/s004410050832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asede D, Bosch D, Luthi A, Ferraguti F, Ehrlich I (2015) Sensory inputs to intercalated cells provide fear-learning modulated inhibition to the basolateral amygdala. Neuron 86:541–554. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asede D, Okoh J, Ali S, Doddapaneni D, Bolton MM (2021a) Deletion of ErbB4 disrupts synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation of thalamic input to amygdalar medial paracapsular intercalated cells. Front Synaptic Neurosci 13:697110. 10.3389/fnsyn.2021.697110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asede D, Doddapaneni D, Chavez A, Okoh J, Ali S, Von-Walter C, Bolton MM (2021b) Apical intercalated cell cluster: a distinct sensory regulator in the amygdala. Cell Rep 35:109151. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Killcross S (2006) Parallel incentive processing: an integrated view of amygdala function. Trends Neurosci 29:272–279. 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Been LE, Petrulis A (2011) Chemosensory and hormone information are relayed directly between the medial amygdala, posterior bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and medial preoptic area in male Syrian hamsters. Horm Behav 59:536–548. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta S, Pantazopoulos H, Caldera M, Pantazopoulos P, Paré D (2005) Infralimbic cortex activation increases c-Fos expression in intercalated neurons of the amygdala. Neuroscience 132:943–953. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu TC, Busti D, Micklem BR, Mansouri M, Magill PJ, Ferraguti F, Capogna M (2015) Large intercalated neurons of amygdala relay noxious sensory information. J Neurosci 35:2044–2057. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1323-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs LM, Meredith M (2022) Functional connectivity of intercalated nucleus with medial amygdala: a circuit relevant for chemosignal processing. IBRO Neurosci Rep 12:170–181. 10.1016/j.ibneur.2022.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissière S, Humeau Y, Lüthi A (2003) Dopamine gates LTP induction in lateral amygdala by suppressing feedforward inhibition. Nat Neurosci 6:587–592. 10.1038/nn1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaesse P, Goedecke L, Bazelot M, Capogna M, Pape HC, Jungling K (2015) mu-Opioid receptor-mediated inhibition of intercalated neurons and effect on synaptic transmission to the central amygdala. J Neurosci 35:7317–7325. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0204-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar RJ (2014) Endogenous opiates and behavior: 2013. Peptides 62:67–136. 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busti D, Geracitano R, Whittle N, Dalezios Y, Mańko M, Kaufmann W, Satzler K, Singewald N, Capogna M, Ferraguti F (2011) Different fear states engage distinct networks within the intercalated cell clusters of the amygdala. J Neurosci 31:5131–5144. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6100-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G (1984) Feed-forward inhibition in the hippocampal formation. Prog Neurobiol 22:131–153. 10.1016/0301-0082(84)90023-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral A, Ruggiero RN, Nobre MJ, Brandão ML, Castilho VM (2009) GABA and opioid mechanisms of the central amygdala underlie the withdrawal-potentiated startle from acute morphine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33:334–344. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Li Y, Liu Y, Xu H, Bi LL (2021) Neuregulin-1-dependent control of amygdala microcircuits is critical for fear extinction. Neuropharmacology 201:108842. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchland PS, Sejnowski TJ (1994) The computational brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ciocchi S, Herry C, Grenier F, Wolff SB, Letzkus JJ, Vlachos I, Ehrlich I, Sprengel R, Deisseroth K, Stadler MB, Muller C, Luthi A (2010) Encoding of conditioned fear in central amygdala inhibitory circuits. Nature 468:277–282. 10.1038/nature09559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DR, Paré D (1999) Reciprocal changes in the firing probability of lateral and central medial amygdala neurons. J Neurosci 19:836–844. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00836.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley NA, Bloodgood DW, Hardaway JA, Kendra AM, McCall JG, Al-Hasani R, McCall NM, Yu W, Schools ZL, Krashes MJ, Lowell BB, Whistler JL, Bruchas MR, Kash TL (2016) Dynorphin controls the gain of an amygdalar anxiety circuit. Cell Rep 14:2774–2783. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daviss WB, O'Donnell L, Soileau BT, Heard P, Carter E, Pliszka SR, Gelfond JA, Hale DE, Cody JD (2013) Mood disorders in individuals with distal 18q deletions. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 162B:879–888. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mora MP, Cárdenas-Cachón L, Vázquez-García M, Crespo-Ramírez M, Jacobsen K, Höistad M, Agnati L, Fuxe K (2005) Anxiolytic effects of intra-amygdaloid injection of the D1 antagonist SCH23390 in the rat. Neurosci Lett 377:101–105. 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mora MP, Gallegos-Cari A, Arizmendi-García Y, Marcellino D, Fuxe K (2010) Role of dopamine receptor mechanisms in the amygdaloid modulation of fear and anxiety: structural and functional analysis. Prog Neurobiol 90:198–216. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobi A, Sartori SB, Busti D, Van der Putten H, Singewald N, Shigemoto R, Ferraguti F (2013) Neural substrates for the distinct effects of presynaptic group III metabotropic glutamate receptors on extinction of contextual fear conditioning in mice. Neuropharmacology 66:274–289. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorofeikova M, Borkar CD, Weissmuller K, Smith-Osborne L, Basavanhalli S, Bean E, Duong A, Resendez A, Fadok JP (2021) Sex-dependent effects of traumatic stress on social behavior and neuronal activation in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala. bioRxiv 473017. 10.1101/2021.12.16.473017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Humeau Y, Grenier F, Ciocchi S, Herry C, Luthi A (2009) Amygdala inhibitory circuits and the control of fear memory. Neuron 62:757–771. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JH, Koziell DA, Moore RY (1978) Catecholamine innervation of the basal forebrain: II. Amygdala, suprarhinal cortex and entorhinal cortex. J Comp Neurol 180:509–532. 10.1002/cne.901800308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe K, Jacobsen KX, Hoistad M, Tinner B, Jansson A, Staines WA, Agnati LF (2003) The dopamine D1 receptor-rich main and paracapsular intercalated nerve cell groups of the rat amygdala: relationship to the dopamine innervation. Neuroscience 119:733–746. 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00148-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geracitano R, Kaufmann WA, Szabo G, Ferraguti F, Capogna M (2007) Synaptic heterogeneity between mouse paracapsular intercalated neurons of the amygdala. J Physiol 585:117–134. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouty S, Silveira JT, Cote TE, Cox BM (2021) Aversive stress reduces mu opioid receptor expression in the intercalated nuclei of the rat amygdala. Cell Mol Neurobiol 41:1119–1129. 10.1007/s10571-020-01026-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greba Q, Kokkinidis L (2000) Peripheral and intraamygdalar administration of the dopamine D1 receptor antagonist SCH 23390 blocks fear-potentiated startle but not shock reactivity or the shock sensitization of acoustic startle. Behav Neurosci 114:262–272. 10.1037//0735-7044.114.2.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greba Q, Gifkins A, Kokkinidis L (2001) Inhibition of amygdaloid dopamine D2 receptors impairs emotional learning measured with fear-potentiated startle. Brain Res 899:218–226. 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoriou GC, Kissiwaa SA, Patel SD, Bagley EE (2019) Dopamine and opioids inhibit synaptic outputs of the main island of the intercalated neurons of the amygdala. Eur J Neurosci 50:2065–2074. 10.1111/ejn.14107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoriou GC, Patel SD, Winters BL, Bagley EE (2020) Neprilysin controls the synaptic activity of neuropeptides in the intercalated cells of the amygdala. Mol Pharmacol 98:454–461. 10.1124/mol.119.119370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoriou GC, Patel SD, Pyne S, Winters BL, Bagley EE (2021) Opioid withdrawal abruptly disrupts amygdala circuit function by reducing peptide actions. bioRxiv 471860. 10.1101/2021.12.22.471860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara KM, Bukalo O, Zeller M, Aksoy-Aksel A, Karalis N, Limoges A, Rigg T, Campbell T, Mendez A, Weinholtz C, Mahn M, Zweifel LS, Palmiter RD, Ehrlich I, Luthi A, Holmes A (2021) Intercalated amygdala clusters orchestrate a switch in fear state. Nature 594:403–407. 10.1038/s41586-021-03593-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herry C, Ciocchi S, Senn V, Demmou L, Müller C, Lüthi A (2008) Switching on and off fear by distinct neuronal circuits. Nature 454:600–606. 10.1038/nature07166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herry C, Ferraguti F, Singewald N, Letzkus JJ, Ehrlich I, Luthi A (2010) Neuronal circuits of fear extinction. Eur J Neurosci 31:599–612. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JE, Gasser PJ (2013) Organic cation transporter 3 is densely expressed in the intercalated cell groups of the amygdala: anatomical evidence for a stress hormone-sensitive dopamine clearance system. J Chem Neuroanat 52:36–43. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Chen CC, Liang YC, Hsu KS (2014) Long-term potentiation at excitatory synaptic inputs to the intercalated cell masses of the amygdala. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 17:1233–1242. 10.1017/S1461145714000133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen KX, Hoistad M, Staines WA, Fuxe K (2006) The distribution of dopamine D1 receptor and mu-opioid receptor 1 receptor immunoreactivities in the amygdala and interstitial nucleus of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure: relationships to tyrosine hydroxylase and opioid peptide terminal systems. Neuroscience 141:2007–2018. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez SA, Maren S (2009) Nuclear disconnection within the amygdala reveals a direct pathway to fear. Learn Mem 16:766–768. 10.1101/lm.1607109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungling K, Seidenbecher T, Sosulina L, Lesting J, Sangha S, Clark SD, Okamura N, Duangdao DM, Xu YL, Reinscheid RK, Pape HC (2008) Neuropeptide S-mediated control of fear expression and extinction: role of intercalated GABAergic neurons in the amygdala. Neuron 59:298–310. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaoru T, Liu FC, Ishida M, Oishi T, Hayashi M, Kitagawa M, Shimoda K, Takahashi H (2010) Molecular characterization of the intercalated cell masses of the amygdala: implications for the relationship with the striatum. Neuroscience 166:220–230. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lee JH, Ko B, Kwon OB (2018) POSTECH Academy-Industry Foundation, assignee. Mouse with D4R iRNA in the intercalating cell mass of the amygdala. United States patent US10668061B2 (2020) June 2.

- Krabbe S, Grundemann J, Luthi A (2018) Amygdala inhibitory circuits regulate associative fear conditioning. Biol Psychiatry 83:800–809. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krettek J, Price J (1978) A description of the amygdaloid complex in the rat and cat with observations on intra-amygdaloid axonal connections. J Comp Neurol 178:255–280. 10.1002/cne.901780205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbitz J, Arnett M, Ehrman S, Williams MT, Vorhees CV, Fisher SE, Garratt AN, Muglia LJ, Waclaw RR, Campbell K (2018) Loss of intercalated cells (ITCs) in the mouse amygdala of Tshz1 mutants correlates with fear, depression, and social interaction phenotypes. J Neurosci 38:1160–1177. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1412-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbitz J, Madhavan M, Ehrman L, Kohli V, Waclaw R, Campbell K (2021) Temporally distinct roles for the zinc finger transcription factor Sp8 in the generation and migration of dorsal lateral ganglionic eminence (dLGE)-derived neuronal subtypes in the mouse. Cereb Cortex 31:1744–1762. 10.1093/cercor/bhaa323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon OB, Lee JH, Kim HJ, Lee S, Lee S, Jeong MJ, Kim SJ, Jo HJ, Ko B, Chang S, Park SK, Choi YB, Bailey CH, Kandel ER, Kim JH (2015) Dopamine regulation of amygdala inhibitory circuits for expression of learned fear. Neuron 88:378–389. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont EW, Kokkinidis L (1998) Infusion of the dopamine D1 receptor antagonist SCH 23390 into the amygdala blocks fear expression in a potentiated startle paradigm. Brain Res 795:128–136. 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00281-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law AJ, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR, Weickert CS (2007) Disease-associated intronic variants in the ErbB4 gene are related to altered ErbB4 splice-variant expression in the brain in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet 16:129–141. 10.1093/hmg/ddl449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE (2000) Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 23:155–184. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Amano T, Paré D, Nair SS (2011) Impact of infralimbic inputs on intercalated amygdala neurons: a biophysical modeling study. Learn Mem 18:226–240. 10.1101/lm.1938011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon I, Taylor SF, Phan KL, Britton JC, Fig LM, Bueller JA, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK (2007) Altered central micro-opioid receptor binding after psychological trauma. Biol Psychiatry 61:1030–1038. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtik E, Popa D, Apergis-Schoute J, Fidacaro GA, Paré D (2008) Amygdala intercalated neurons are required for expression of fear extinction. Nature 454:642–645. 10.1038/nature07167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez de Armentia M, Sah P (2004) Firing properties and connectivity of neurons in the rat lateral central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurophysiol 92:1285–1294. 10.1152/jn.00211.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R, Uematsu A, Weitemier A, Aquili L, Koivumaa J, McHugh TJ, Johansen JP (2018) A dopaminergic switch for fear to safety transitions. Nat Commun 9:11. 10.1038/s41467-018-04784-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz PE, Kieffer BL (2013) The multiple facets of opioid receptor function: implications for addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23:473–479. 10.1016/j.conb.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mańko M, Geracitano R, Capogna M (2011) Functional connectivity of the main intercalated nucleus of the mouse amygdala. J Physiol 589:1911–1925. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Burke S, Meng F, Thompson RC, Akil H, Watson SJ (1994) Mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol 350:412–438. 10.1002/cne.903500307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maras PM, Petrulis A (2010) The anterior medial amygdala transmits sexual odor information to the posterior medial amygdala and related forebrain nuclei. Eur J Neurosci 32:469–482. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S (2005) Synaptic mechanisms of associative memory in the amygdala. Neuron 47:783–786. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markota M, Sin J, Pantazopoulos H, Jonilionis R, Berretta S (2014) Reduced dopamine transporter expression in the amygdala of subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 40:984–991. 10.1093/schbul/sbu084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marowsky A, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Vogt KE (2005) A specialized subclass of interneurons mediates dopaminergic facilitation of amygdala function. Neuron 48:1025–1037. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough KM, Morrison FG, Ressler KJ (2016) Bridging the gap: towards a cell-type specific understanding of neural circuits underlying fear behaviors. Neurobiol Learn Mem 135:27–39. 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ (1982a) Cytoarchitecture of the central amygdaloid nucleus of the rat. J Comp Neurol 208:401–418. 10.1002/cne.902080409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ (1982b) Neurons of the lateral and basolateral amygdaloid nuclei: a Golgi study in the rat. J Comp Neurol 212:293–312. 10.1002/cne.902120307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan S, Lawrence AD, Sales T, Quested D, Grasby P (2004) Presynaptic dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: a positron emission tomographic [18F]fluorodopa study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:134–142. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina G, Ji G, Gregoire S, Neugebauer V (2014) Nasal application of neuropeptide S inhibits arthritis pain-related behaviors through an action in the amygdala. Mol Pain 10:32. 10.1186/1744-8069-10-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei L, Nave KA (2014) Neuregulin-ERBB signaling in the nervous system and neuropsychiatric diseases. Neuron 83:27–49. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millhouse OE (1986) The intercalated cells of the amygdala. J Comp Neurol 247:246–271. 10.1002/cne.902470209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami S, Kiyokawa Y, Takeuchi Y (2019) The lateral intercalated cell mass of the amygdala is activated during social buffering of conditioned fear responses in male rats. Behav Brain Res 372:112065. 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov A, Sukato D, Ito W (2011) Selective suppression of plasticity in amygdala inputs from temporal association cortex by the external capsule. J Neurosci 31:339–345. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5537-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez M, Millon C, Borroto-Escuela D, Flores-Burgess A, Santin L, Parrado C, Gago B, Puigcerver A, Fuxe K, Narvaez JA, Diaz-Cabiale Z (2015) Galanin receptor 2-neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor interactions in the amygdala lead to increased anxiolytic actions. Brain Struct Funct 220:2289–2301. 10.1007/s00429-014-0788-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]