Abstract

Effective treatments for chronic pain remain limited. Conceptually, a closed-loop neural interface combining sensory signal detection with therapeutic delivery could produce timely and effective pain relief. Such systems are challenging to develop due to difficulties in accurate pain detection and ultrafast analgesic delivery. Pain has sensory and affective components, encoded in large part by neural activities in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), respectively. Meanwhile, studies show that stimulation of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) produces descending pain control. Here, we designed and tested a brain-machine interface (BMI) combining an automated pain detection arm, based on simultaneously recorded local field potential (LFP) signals from the S1 and ACC, with a treatment arm, based on optogenetic activation or electrical deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the PFC in freely behaving rats. Our multi-region neural interface accurately detected and treated acute evoked pain as well as chronic pain. This neural interface is activated rapidly and its efficacy remained stable over time. Given the clinical feasibility of LFP recordings and DBS, our findings suggest that BMI is a promising approach for pain treatment.

One sentence summary:

A multi-region brain machine interface automatically detects pain and delivers ultrafast analgesia for acute and chronic pain in rodents.

INTRODUCTION

Closed-loop brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) link neural signals for a sensory or motor event with neuromodulation and have the potential to treat neuropsychiatric disorders(1–3). BMIs have produced promising results for treating epilepsy and motor neuron diseases(4–8). However, their application to sensory disorders have been limited by challenges in detecting accurate sensory signals and providing fast and effective behavioral feedback.

Pain represents a unique challenge as well as an opportunity for BMI designs. Chronic pain is one of the most common sensory disorders, and it is defined by discrete episodes of pain that either are evoked by noxious stimuli or occur spontaneously(9). Current treatments are limited to scheduled pharmacological interventions and continuous spinal neuromodulation. These therapeutic options do not take into consideration the precise timing of individual pain episodes, resulting in frequent treatment delays and under- or overtreatment(10). Conceptually, a BMI approach is ideally suited to pain management by selectively targeting discrete nociceptive episodes. However, decoding pain signals remains challenging. Unlike other sensory modalities(11), there is no single target for pain representations(12–16). Among a distributed network of pain-processing regions, the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) is known to encode sensory-discriminative aspect of pain, including the location, timing, and quality of pain, whereas the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is known to play a key role in aversive response to pain(12–14, 17–20). Thus, an appealing strategy to decode pain is to integrate neural signals from multiple regions, with the S1 and ACC as the most relevant targets.

Current BMI applications primarily rely on neuronal spikes to produce accurately decoded signals. However, individual spikes are difficult to record faithfully over a prolonged period of time, which is needed for the management of chronic pain. In contrast, local field potentials (LFPs), which represent the subthreshold synaptic activity from local neuronal populations(21, 22), are relatively stable in chronic recordings. Although their signal stability facilitates clinical applications, LFPs have only recently started to be used for population decoding for BMI applications(23–25).

In terms of treatment targets, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is an important center for top-down control of sensory experiences(26). Human and animal studies have shown that decreased activity in the PFC contributes to symptoms of chronic pain(27–32). Importantly, stimulation of excitatory neurons in the PFC can produce rapid inhibition of withdrawal reflexes and aversive responses to pain without substantial side effects(32–37), supporting the use of PFC as a potential therapeutic target in BMI design.

In this study, we have developed an LFP-based decoding strategy using recordings from rodent S1 and ACC, and combined it with optogenetic or electrical stimulation of the PFC to form a multi-region neural interface. We show that this neural interface triggers analgesic stimulations with high sensitivity and specificity over a long period of time.

RESULTS

Design of a stable multi-region neural interface to detect and treat pain in real time

The S1 is known to provide sensory information for noxious inputs(16). Previous studies have shown that neural spikes from this region may decode the onset of pain that is generated in the corresponding somatotopic area(38, 39). Meanwhile, studies indicate that the ACC, particularly the rostral ACC, regulates the affective component of pain and can be used to decode both the onset and intensity of pain(12, 13, 19, 39). At the same time, stimulation of the prelimbic PFC (PL-PFC) has been shown to activate top-down regulatory pathways to inhibit pain(32–37). Based on these studies, we developed a multi-region, closed-loop neural interface for nociceptive control by using a pain decoder based on concurrent neural signals from the ACC and S1 to trigger potential analgesic stimulation of the PL-PFC in freely behaving rats (Fig. 1, A and B, and figs. S1 and S2). To decode pain onset, we recorded LFPs (21, 22), which are known to remain stable in chronic electrophysiological recordings (23–25). Here, we recorded LFPs simultaneously from the rostral ACC and the hind limb region of S1 (fig. S3A), while stimulating the contralateral hind paw of rats with either noxious pin pricks (PP) or non-noxious von Frey filaments (vF). From these neural signals, we could readily identify pain-evoked event-related potentials (ERPs) from the ACC and S1 (fig. S3A), indicating that nociceptive signals are contained within these two regions(12–14, 17–20). We extracted the ERP latency on a trial-by-trial basis (see Supplementary Materials and Methods), and found that the ERP peak latency in the ACC was on average slightly longer than the latency in the S1, suggesting that nociceptive information arrived at the S1 before the ACC (fig. S3B), compatible with earlier reports(40–42). These results support the use of LFP signals from S1 and ACC to decode pain.

Fig. 1. Design of a multi-region LFP-based neural interface for pain.

(A) Schematic of experiments. The online closed-loop brain-machine interface (BMI) consists of three steps. In step ①, silicon probe arrays are implanted in the rat anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and primary somatosensory cortex (S1) to record local field potentials (LFPs) simultaneously. In step ②, LFP signals are processed and sent to an automated decoder based on a state space model (SSM) to detect the onset of pain. In step ③, detected pain onset triggers neurofeedback in the form of optogenetic or electrical activation of the prelimbic prefrontal cortex (PL-PFC) to deliver pain modulation. (B) Placement of optic fiber or deep brain stimulating (DBS) electrode in the PL-PFC and recording silicon probes in the ACC and S1. (C) Raw LFP signals were processed to compute three band-limited LFP power features for the ACC channel: and S1 channel: , where the index k denotes the k-th temporal window (bin size 100 ms). MUA: multi-unit activity (300–500 Hz). (D) Schematic of two SSMs used to independently infer the latent variables and from the LFP features and of ACC and S1, respectively (see Supplementary Materials and Methods for details). The SSM is illustrated by a graphical model with a Markovian structure, in which each node denotes a random variable, and the arrow indicates statistical dependency between two random variables. (E) Illustration of a multi-region decoding strategy for pain onset. First, the Z-scores were derived from the latent variables and (horizontal dashed lines denote the 95% confidence intervals for statistical significance). Next, a moving average cross-correlation function (CCF) was used to compute the correlation between the two Z-score series. The area beyond statistical significance (horizontal dashed lines) was computed to determine the change point (Supplementary Materials and Methods). When pain onset was detected, the decoder automatically triggered optogenetic or DBS stimulation to activate the PL-PFC.

We designed a model-based unsupervised learning approach to decode pain from multi-region LFP signals. Prior work has shown that spectral features from low gamma (30–50 Hz), high gamma (50–100 Hz), and ultra-high frequency (300–500 Hz) bands are particularly relevant for cortical pain processing(41–43). The ultra-high frequency power can be viewed as a proxy for multiunit activity (MUA). Thus, we computed frequency-dependent LFP power features and inputted these features into a real-time neural decoder based on a state space model (SSM) (Fig. 1, C to E; Supplementary Materials and Methods). In the presence of a noxious stimulus, the SSM identified a relative change in observed neural activity (Z-scored) from the baseline, and used this change in activity as a proxy for the acute pain signal. To optimize the specificity of pain detection, we designed a cross-correlation function (CCF, see Supplementary Materials and Methods) to track temporally coherent changes of pain-encoded LFP features in the S1 and ACC, as the use of concurrent signals from these cortical regions allowed us to capture both sensory and aversive components of pain(12–14, 17–20). This CCF combined the two SSM-inferred Z-scores derived separately from the ACC and S1 LFP features, and optimized the detection performance by adjusting the relative weights of each region’s contributions. For online BMI experiments, we used the CCF-based decoder to automatically detect the onset of nociceptive signal to trigger optogenetic or electrical stimulation of the PL-PFC to control pain (Fig. 1, A and B, and figs. S1 and S2).

We tested our decoding strategy in a set of pain assays. First, we delivered a noxious PP or non-noxious 2g or 6g vF stimulus to the rat’s hind paw, while recording LFPs from the contralateral areas of the rostral ACC and the hind limb region of the S1 (Fig. 2A). As expected, rats showed a higher paw withdrawal rate in response to PP than to vF stimulations (Fig. 2B). In online experiments, our SSM decoder successfully detected the onset of noxious PP stimulus (Fig. 2C), as opposed to non-noxious vF stimulus (Fig. 2D). Using this method, we trained the decoder with a few calibration trials with PP and conducted online BMI behavior experiments that continuously and automatically detected the onset of pain signals (Fig. 2E). The detection rate for the noxious stimulus (PP) was higher than the non-noxious stimulus (2g or 6g vF) based on LFPs from ACC, S1 or a combination of ACC and S1 (the CCF method) (Fig. 2F). These results suggest that our decoding paradigm can detect “painful” stimuli and distinguish them from “non-painful” stimuli of varying intensities. The area under curve (AUC, see Supplementary Materials and Methods) was computed to further validate the detection accuracy of the system (Table S1). The results show that AUC values for detecting 2g vF or 6g vF are both at chance accuracy; in contrast, the AUC value for detecting PP is higher. In addition, detection using the CCF method is superior to decoding using either the ACC or S1 alone (Fig. 2F, Table S1). To further quantify the accuracy of the CCF-based decoding method, we compared the false detection rate produced by the CCF strategy with the false detection rate produced by single-region decoding methods. We found that the multi-region decoding strategy showed a substantial reduction in false detections (Fig. 2G), likely contributing to the enhanced specificity of CCF-based decoding. Such high true detection and low false detection rates are critical for a real-world implementation of a BMI system and demonstrates the importance of using multiple regions to optimize pain decoding.

Fig. 2. The multi-region LFP-based neural interface reduces acute mechanical and thermal pain.

(A) Schematic of pain experiments demonstrating peripheral stimulation with either pin prick (PP) or von Frey filament (vF). LFP signals were recorded from ACC and S1 for pain detection, and optogenetic stimulation was administered to the PL-PFC for pain control. (B) Withdrawal response to mechanical stimulation, n = 10 rats; ****P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. (C) Illustration of mechanical pain onset detection using an LFP-based strategy. LFP features were computed from the ACC, S1, or both ACC and S1. The top two panels show single-channel LFP traces (white) overlying the spectrogram. The vertical dotted line indicates the onset of noxious peripheral stimulus (PP), and the vertical solid line indicates the time of paw withdrawal. The third and fourth panels show Z-scores (shaded areas denote the 95% confidence intervals) derived from the SSM-based decoder using LFPs recorded from ACC and S1, respectively (Methods). The two horizontal lines indicate the Z-score threshold ± 3.38. The fifth panel shows the cross-correlation function (CCF) between ACC and S1 from the third and fourth panels. The two horizontal dashed lines indicate the significance threshold. The bold triangle indicates the detection point. (D) Similar to panel c, except that the stimulus given is non-noxious (vF). (E) Demonstration of continuous online pain onset detection in a sample recording session. The vertical dotted line indicates the stimulus onset, and the vertical solid line indicates paw withdrawal. ♦ denotes true pain detection, * denotes false detection. (F) Comparison of detection rates between various non-noxious stimuli and noxious PP based on LFP decoding strategies using the ACC, S1 and combined (ACC + S1) signals. Each circle indicates data from one rat, n = 5 rats; ns, P > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests to compare decoding rates for 2g vF, 6g vF, PP stimulation using signals from the ACC, S1 or ACC+S1. (G) The false positive (FP) detection rate per minute. n = 5 rats; P = 0.9679 (ACC vs S1), **P = 0.0036 (ACC vs ACC+S1), **P = 0.0036 (S1 vs ACC+S1), one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. (H) Comparison of detection rates based on LFP signals recorded in two different sessions, 3 months apart. Session 2 was recorded 3 months after session 1. Each pair of circles connected by a line indicates data from the same rat. We used the first 1–3 trials of each recording session to train the parameters of the SSM. n = 5 rats; *P = 0.0148 (ACC), P = 0.4651 (S1), P = 0.8650 (ACC+S1), paired t-test. (I) Comparison of detection rates based on model parameters set 5 days apart. We used the first 3 trials on Day 1 to train the parameters of SSM, and then used these same parameters to detect pain on the subsequent 5 days. n = 5 rats; P = 0.2339, one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests.

For therapeutic BMI applications, signal stability is critical. In our previous pain decoding studies using neural spike signals, spike signal stability could become unpredictable over time, requiring repeated model parameter updates (38). Here, we tested the reliability of the LFP signals and found that our LFP-based decoding strategy maintained a high degree of accuracy over three months (Fig. 2H, fig. S4A). Furthermore, when we used the model parameters derived from day 1 of testing, we found that the same model was able to detect pain with high accuracy on day 5, suggesting that the model parameters may not require frequent training or calibration (Fig. 2I, fig. S4B). Such signal and model fidelity for pain decoding are appealing for real-world applications with chronic neural recordings.

Automated pain detection and analgesic delivery by the multi-region neural interface

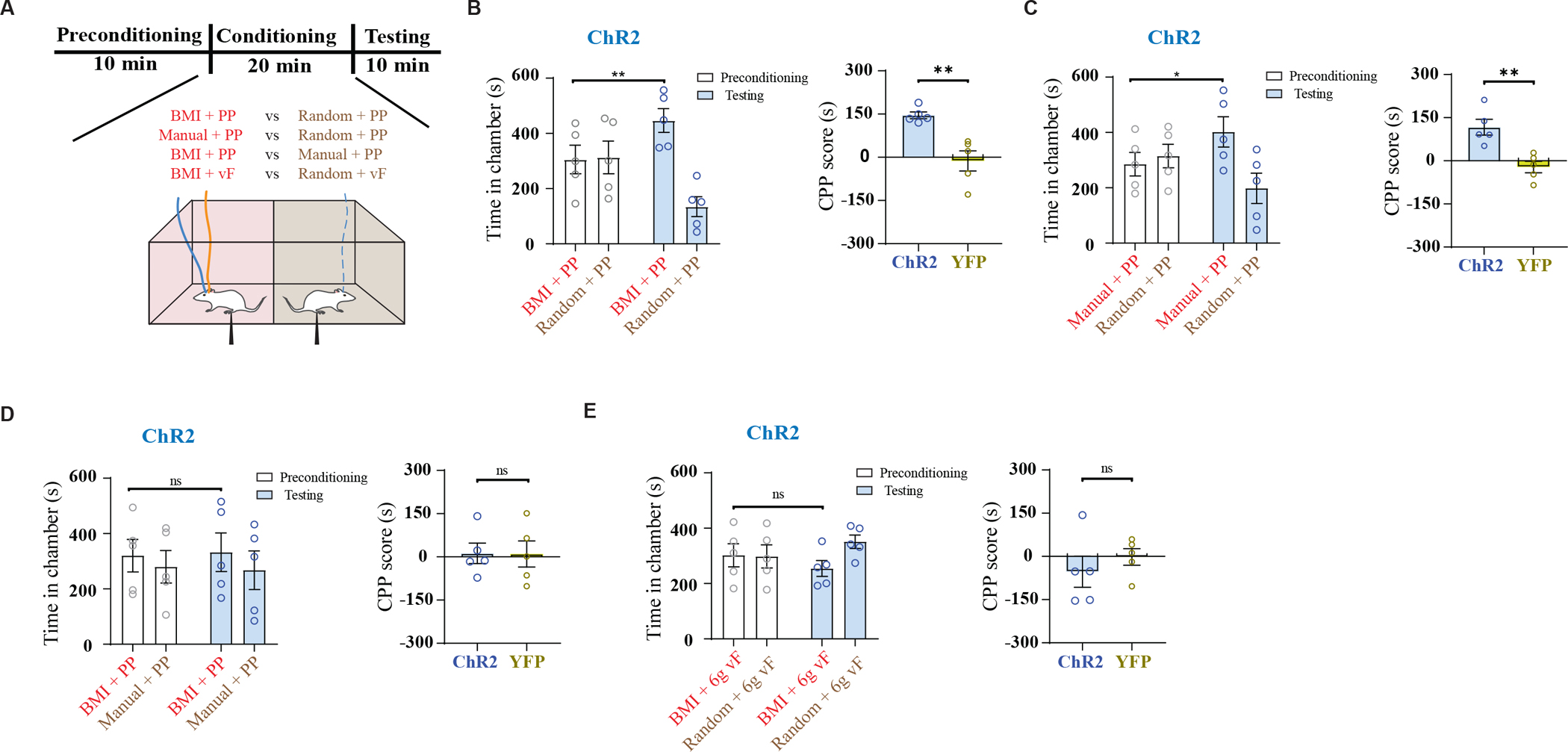

Having established the accuracy, specificity, and reliability of our CCF-based pain decoder, we coupled this decoder with optogenetic stimulation of pyramidal neurons of the PL-PFC (using a CaMKII promotor to express channelrhodopsin (ChR2)) to form an analgesic BMI (Fig. 1, A and B, and figs. S1 and S2). We used a conditioned place preference (CPP) assay to assess how this BMI could inhibit acute mechanical pain(19, 37, 40). In the preconditioning phase, animals moved freely between two chambers. During conditioning, we paired each chamber with a peripheral (noxious or non-noxious) stimulus in combination with BMI or various control optogenetic neurostimulation protocols (Fig. 3A). In the testing phase, we removed peripheral stimuli and neurostimulation and allowed the rats to move freely again. If the BMI treated pain, rats should prefer the chamber associated with the BMI during the testing phase. A CPP score was calculated by subtracting the time rats spent in the BMI-paired chamber during the preconditioning phase from the time they spent in the testing phase, to quantify the effects of BMI on reducing pain-aversion. First, we compared noxious PP stimulation coupled with BMI-triggered optogenetic stimulation of the PL-PFC (BMI + PP) against PP coupled with random PL-PFC stimulation of matching duration and intensity (random neurostimulation + PP). Rats preferred the chamber associated with the BMI, suggesting that it reduced acute mechanical pain (Fig. 3B). We then repeated this experiment on rats that expressed yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), and found that YFP-treated control rats did not experience pain relief (fig. S5A). A comparison of the CPP scores highlighted the efficacy of the BMI in delivering analgesia (Fig. 3B). As a positive control, we compared manual activation of the PL-PFC directly following delivery of PP to the paw (manual + PP) against random PL-PFC stimulation coupled with PP (random + PP). Here, we observed a preference for manual PL-PFC activation in ChR2 rats but not YFP rats (Fig. 3C and fig. S5B), compatible with earlier reports (33, 37). Results from Figs. 3B and 3C suggest the BMI worked as well as precise manual control of the PL-PFC. To confirm this finding, we compared BMI control of the PL-PFC in the presence of PP with manual control of PL-PFC in the presence of PP, and found that rats could not distinguish between the two treatments (Fig. 3D and fig. S5C). Finally, to demonstrate that the effects of the PL-PFC activation delivered by the BMI were specific to pain, we examined the rats’ preference for BMI in the presence of a non-noxious vF stimulus (by comparing BMI + 6g vF with random PL-PFC activation + 6g vF), and found that rats did not show a preference for either chamber (Fig. 3E and fig. S5D). These results support the specificity of the BMI in delivering pain control without substantial side effects. Furthermore, we found that BMI treatment also reduced firing rates of ACC neurons in response to noxious stimuli (fig. S6).

Fig. 3. The multi-region LFP-based neural interface reduces acute mechanical pain.

(A) Schematic of conditioned place preference (CPP) assays to assess pain aversion. In a two-chamber set up, during conditioning, one of the chambers was paired with treatment shown in red, and the opposite chamber was paired with control conditions shown in brown (see Supplementary Materials and Methods for details). (B) Left panel: Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in BMI+PP vs random+PP paired chambers, n = 5 rats; **P = 0.0016, paired t-test. Right panel: comparison of CPP scores of ChR2-expressing and YFP-expressing (control) rats (n = 5 ChR2 rats and 5 YFP rats, **P = 0.0027, unpaired t-test). (C) Left panel: Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in manual+PP vs random+PP paired chambers, n = 5 rats; *P = 0.013, paired t-test. Right panel: comparison of CPP scores of ChR2 and YFP rats (n = 5 ChR2 rats and 5 YFP rats, **P = 0.0036, unpaired t-test). (D) Left panel: Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in BMI+PP vs manual+PP paired chambers, n = 5 rats; P = 0.74, paired t-test. Right panel: comparison of CPP scores of ChR2 and YFP rats (n = 5 ChR2 rats and 5 YFP rats, P = 0.969, unpaired t-test). (E) Left panel: Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in BMI+6g vF vs random+6g vF paired chambers, n = 5 rats; P = 0.46, paired t-test. Right panel: comparison of CPP scores of ChR2 and YFP rats (n = 5 ChR2 rats and 5 YFP rats, P = 0.428, unpaired t-test).

We then tested this multi-region BMI on acute thermal pain using a Hargreaves test. We first delivered infrared (IR) stimulations at two different intensities – noxious IR 70 and non-noxious IR 10 – to the rats’ hind paws (Fig. 4A). Rats withdrew their paws 100% of the time with IR 70 stimulations, compared to <10% of the time with IR 10 stimulations (Fig. 4B). Our multi-region LFP-based pain decoder successfully detected the onset of thermal pain before paw withdrawals in response to noxious stimulation (Fig. 4C), but not to non-noxious thermal stimulation (Fig. 4D). Similar to the decoding of mechanical pain, CCF-based pain decoding showed a lower (<10%) false positive detection rate than single-region decoding, while maintaining high (~80%) detection rate for noxious stimulations. This remained true even when non-noxious stimulations of varying intensities (IR 10 and 20) were administered, demonstrating the ability of the decoder to specifically distinguish pain episodes rather than different stimulus intensities (Fig. 4E, Table S2). Next, we tested the efficacy of this BMI in relieving thermal pain (fig. S7). We found the latency to paw withdrawal increased in the presence of neurostimulation driven by the multi-region BMI, and that the BMI achieved similar effects in reducing withdrawals as manually controlled constitutive PL-PFC activation (Fig. 4F). As expected, control rats that expressed YFP did not demonstrate pain relief (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4. The multi-region neural interface reduces acute thermal pain.

(A) Schematic of thermal stimulation experiments, with infrared intensity (IR) set to either 70 (noxious) or 10 (non-noxious). (B) IR 70 elicited paw withdrawals. n = 10 rats; ****P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. (C, D) Illustration of thermal pain onset detection using an LFP-based strategy, similar to panels 2C and 2D. (E) Comparison of the detection rate based on LFP decoding strategies using the ACC, S1, and combined (ACC + S1) signals. Each circle indicates data from a single rat. Comparison of the detection rates for three LFP-based decoding strategies. n = 5 rats; ns, P > 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests to compare decoding rates for IR 10, 20, 70 using signals from ACC, S1 or ACC+S1. (F) Comparison of paw withdrawal latency for ChR2 rats. n = 5 rats; **P = 0.0089 (No opto vs BMI opto), **P = 0.0044 (No opto vs Manual opto), P = 0.9176 (BMI opto vs Manual opto), one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. (G) Comparison of paw withdrawal latency for YFP control rats. n = 5 rats; P = 0.5385 (No opto vs BMI opto), P = 0.9741 (No opto vs Manual opto), P = 0.7909 (BMI opto vs Manual opto), one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests.

Closed-loop multi-region neural interface inhibits inflammatory pain

Next, we tested whether this closed-loop multi-region neural interface can also treat chronic pain, using a well-known inflammatory pain model, the Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) model. We injected CFA into the rats’ paws contralateral to the implanted recording electrodes (Fig. 5A, see Supplementary Materials and Methods). CFA-treated rats demonstrated persistent mechanical allodynia lasting 14 days (Fig. 5B), and showed higher rates of paw withdrawal in response to 6g vF (allodynia-inducing) stimulations than 0.4g vF (non-allodynic) stimulations (Fig. 5C). Our LFP-based decoding strategy reliably detected the onset of allodynic episodes (Fig. 5D). Again, the CCF method produced a lower rate of false detections, while maintaining relatively high decoding sensitivity (Fig. 5E, Table S2). Furthermore, we found that application of this BMI reduced mechanical allodynia in CFA-treated rats (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5. The multi-region neural interface performance in a chronic inflammatory pain model.

(A) Schematic of experiments in CFA-treated rats. (B) CFA injection caused mechanical allodynia, n = 10 rats (5 ChR2 rats and 5 YFP rats); ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. (C) Paw withdrawal rate with vF stimulation. n = 10 rats, ****P < 0.0001, paired t-test. (D) Illustration of the multi-region LFP-based strategy for detecting the onset of evoked pain signal in a CFA-treated rat. Similar to panels 2C and 2D. (E) A comparison of different LFP-based strategies for decoding the pain onset in the CFA model. Comparison of the detection rates for the noxious vs non-noxious stimulus, n = 10 rats, ****P < 0.0001, paired t-test. Comparison of the detection rates for three LFP-based decoding strategies. For the noxious stimulus: n = 10 rats; P = 0.8139 (ACC vs S1), P = 0.9993 (ACC vs ACC+S1), P = 0.8231 (S1 vs ACC+S1). For the noxious stimulus: n = 10 rats; P = 0.4975 (ACC vs S1), *P = 0.0250 (ACC vs ACC+S1), **P = 0.0023 (S1 vs ACC+S1), one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. (F) Multi-region LFP-based BMI inhibited mechanical allodynia in CFA-treated rats. n = 5 rats; **P = 0.0026, paired t-test.

Next, we tested the anti-aversive effects of BMI in the CFA model using the CPP assay (Fig. 6A). We paired the allodynic 6g vF stimulus with the BMI in one chamber and with random PL-PFC activation of matching duration and intensity in the opposite chamber. Rats expressing ChR2 showed a preference for the BMI-paired chamber (Fig. 6B); YFP rats, in contrast, did not show any chamber preference (Fig. 6C and fig. S8A). To ensure that the anti-aversive effects of this BMI were specific to pain, we repeated the same experiments using a non-allodynic 0.4 g vF stimulus. In this case, neither ChR2 rats nor YFP rats showed any preference for the BMI treatment (Fig. 6, D and E, and fig. S8B).

Fig. 6. The multi-region neural interface reduces chronic inflammatory pain.

(A) Schematic of CPP assays in CFA-treated rats. 6g vF represents noxious stimulation, 0.4g vF represents non-noxious stimulation. (B) Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in chambers paired with BMI+6g vF vs random+6g vF, n = 5 rats; *P = 0.028, paired t-test. (C) Comparison of CPP scores of ChR2 and YFP rats, n = 5 ChR2 rats and 5 YFP rats; *P = 0.015, unpaired t-test. (D) Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in chambers paired with BMI+0.4g vF vs random+0.4g vF, n = 5 rats; P = 0.392, paired t-test. (E) Comparison of CPP scores of ChR2 and YFP rats, n = 5 ChR2 rats and 5 YFP rats; P = 0.527, unpaired t-test. (F) Schematic of the CPP experiment to test tonic pain in CFA-treated rats. No peripheral stimuli were given. One chamber was paired with closed-loop BMI treatment, and the opposite chamber was paired with random PL-PFC activation of matching duration and intensity. (G) Demonstration of continuous decoding for spontaneous pain detection in the absence of peripheral stimuli. The first and second panels show the Z-score (shaded area denotes the 95% confidence intervals) derived from the LFP-based SSM decoder, where two horizontal dotted lines indicate the Z-score threshold ± 3.38. The third panel shows the cross-correlation function (CCF) between the two Z-scores. Two horizontal dashed lines indicate the significance threshold. The two black triangles mark the detection onset of spontaneous pain. (H) Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in chambers paired with BMI vs random stimulation, n = 5 rats; *P = 0.0266, paired t-test. (I) Comparison of CPP scores of ChR2 and YFP rats, n = 5 ChR2 rats and 5 YFP rats; **P = 0.0087, unpaired t-test.

In addition to hypersensitivity to evoked stimulus, a key pathologic feature of chronic pain is tonic, or spontaneously occurring, pain. Currently, no assays can reliably identify the onset of these spontaneous pain episodes, rendering the timing of treatment exceedingly difficult, which results in either delayed, under- or overtreatment. We used a classic CPP to unmask tonic pain in CFA-treated rats(33, 44, 45). In this assay, one of the chambers was paired with our multi-region BMI, and the other chamber was paired with random PL-PFC optogenetic stimulation. No peripheral stimuli were given, but the rats were conditioned for a prolonged period of time to unmask tonic pain episodes (Fig. 6F). We trained our multi-region decoder using noxious stimulations (PP), and then allowed the trained decoder to automatically detect tonic pain events in the absence of a peripheral stimulus (Fig. 6G). During conditioning, we paired one chamber with our BMI which used automated tonic pain detection to trigger optogenetic PL-PFC activation, and the other chamber with random PL-PFC stimulation. We found that after conditioning, CFA-treated rats preferred the chamber associated with the BMI, indicating that this treatment had a high likelihood of targeting tonic pain episodes, as opposed to random PL-PFC stimulations (Fig. 6H). YFP-treated control rats did not demonstrate this preference (fig. S8C). CPP scores further quantified the efficacy of BMI in reducing the aversive response to tonic pain (Fig. 6I). These results strongly suggest that our multi-region neural interface could identify and treat spontaneous pain in a timely fashion.

Closed-loop deep brain stimulation delivers on-demand analgesia

The use of optogenetics can provide cell-type specific stimulation; however, it is not currently available for clinical application. To advance the translational value of our BMI, we replaced optogenetic stimulation of the PL-PFC with electrical deep brain stimulation (DBS), which has been safely implemented for human use(46–51). We combined electrical stimulation of the PL-PFC with the multi-region LFP-based decoder to produce a closed-loop BMI-triggered DBS system (Fig. 7A and fig. S9). First, we performed CPP to assess the efficacy of this system in treating acute mechanical pain (Fig. 7, B and C). We found that when presented with repeated noxious stimuli (PP), rats preferred the BMI-paired chamber to the chamber paired with randomly timed DBS, suggesting that BMI-triggered DBS reduced mechanical pain (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, this BMI reduced acute thermal pain on the Hargreaves test (Fig. 7E). Next, we assessed the efficacy of this BMI-triggered DBS system in treating chronic pain. We found that our system reduced mechanical allodynia in CFA-treated rats (Fig. 7F). We then conducted CPP in the presence of an allodynia-inducing stimulus (6g vF) (Fig. 7G). We found that when presented with allodynic stimuli, CFA-treated rats preferred the BMI-paired chamber, suggesting that the neural interface reduced pain aversion (Fig. 7H). Finally, we conducted the CPP assay for spontaneous pain (Fig. 7I). We trained our multi-region decoder using the allodynic 6g vF stimulus, and then allowed the decoder to automatically detect tonic pain episodes and trigger therapeutic DBS during conditioning. We found that after conditioning, CFA-treated rats preferred the BMI-paired chamber to the chamber paired with randomly delivered DBS (Fig. 7J). Likewise, when we compared conditioning with BMI-triggered DBS vs no DBS, we found that CFA-treated rats preferred the BMI-paired chamber (fig. S10, A and B). These results suggest that BMI-triggered DBS can inhibit tonic pain. Furthermore, we examined stimulation effects on locomotion and found that it had none (fig. S10C).

Fig. 7. A BMI-driven, closed-loop DBS reduces acute and chronic inflammatory pain.

(A) Placement of stimulating electrode in the PL-PFC and recording electrodes in the ACC and S1. (B) Schematic of pain experiments during mechanical stimulus delivery. (C) Schematic of CPP experiments to assess aversion to evoked pain using DBS. (D) Time spent in preconditioning and testing phase in chambers paired with BMI+PP vs random+PP, n = 7 rats; *P = 0.0207, paired t-test. (E) Schematic of thermal experiments in DBS rats. Top panel: schematic of the Hargreaves test (IR 70). Bottom panel: comparison of paw withdrawal latency during different experimental conditions. n = 7 rats; ***P = 0.001, paired t-test. (F) Top panel: schematic of the experiment. Bottom panel: 50% paw withdrawal threshold in the presence of BMI-driven DBS vs control (no DBS). n = 7 rats; ****P < 0.0001, paired t-test. (G) Schematic of the CPP assay to assess aversion to evoked pain. (H) Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in chambers paired with BMI+vF vs random+vF, n = 7 rats; *P = 0.0194, paired t-test. (I) Schematic of the CPP experiment to test tonic pain in CFA-treated rats. (J) Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in chambers paired with BMI vs random DBS, n = 7 rats; ****P < 0.0001, paired t-test.

Closed-loop BMI inhibits chronic neuropathic pain

To further validate the efficacy of our closed-loop multi-region neural interface for delivering analgesia, we tested it with a model of chronic neuropathic pain - the Spared Nerve Injury (SNI) model (Fig. 8A, see Supplementary Materials and Methods) (52). SNI produced persistent mechanical allodynia (Fig. 8B), that was abolished by the application of the BMI (Fig. 8C). In a CPP assay, one chamber was paired with the BMI, and the other chamber was paired with random PL-PFC electric stimulation of the same quantity and duration. No peripheral stimuli were administered, but rats were conditioned for a prolonged period of time to unmask tonic pain episodes (Fig. 8D). The decoder was trained using an allodynia-inducing stimulus (6.0g vF), and then allowed to automatically detect tonic pain events. We found that after conditioning, SNI-treated rats preferred the BMI-paired chamber (Fig. 8E). These results in chronic neuropathic pain further validate our findings in the inflammatory pain model.

Fig. 8. Closed-loop BMI reduces chronic neuropathic pain.

(A) Schematic of pain experiments in SNI-treated rats. (B) SNI operation resulted in mechanical allodynia, n = 5 rats; ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. (C) Multi-region LFP-based BMI inhibited mechanical allodynia in SNI-treated rats. n = 5 rats; ***P = 0.0004, paired t-test. (D) Schematic of the CPP experiment to test tonic pain in SNI-treated rats.. (E) Time spent in preconditioning and testing phases in chambers paired with BMI vs random DBS, n = 5 rats; *P = 0.0231, paired t-test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have engineered a multi-region LFP-based neural interface to deliver pain relief. Our system employs recordings from multiple brain regions to enhance the coding specificity; it is stable over time and compatible with current electroencephalographic (EEG) or electrocorticographic (ECoG) data. This interface was able to produce almost instantaneous pain relief in rodent models. The use of this interface with optogenetic stimulation of pyramidal PL-PFC neurons supports cell-type specificity to enable mechanistic inquiries and its success with DBS opens the possibility for clinical application.

There is not one single brain region that specifically processes pain information. Instead, different regions process different aspects of pain. To meet the challenge of accurate pain detection, we exploited a strategy that adapts to the unique multidimensional nature of the pain experience. We decoded pain based on neural signals simultaneously recorded from two different brain regions. Ascending nociceptive signals from the periphery are known to terminate in the ACC and S1. The ACC is well-known for processing the affective component of pain (12–15, 19, 38, 48, 53–57), and neural activity in this region has been previously used to decode the intensity and timing of pain(19, 38, 40, 53). The S1, meanwhile, provides critical sensory information for pain in a somatotopic manner. Prior studies have further demonstrated that information flow between these two brain regions integrates sensory and affective information to give rise to the overall pain experience(40, 41). In our study, the success of the multi-region neural interface in treating acute and chronic pain demonstrated the specificity of decoding based on concurrent signals from the S1 and ACC. Mechanistically, these results also confirm that these two regions together contribute to the experience of pain.

A number of studies have shown that the PL-PFC provides pain inhibition through top-down projections as well as projections to other cortical areas(32–36). We have chosen this region as the stimulation target of our neural interface, as it is one of the few neural structures that can regulate both sensory and affective components of pain, especially in the context of nociceptive inputs. The success of our BMI in inhibiting both sensory withdrawal and pain aversion validated this choice. There is functional homology between the rodent PL-PFC and the dorsolateral PFC in primates(58, 59), suggesting the possibility that our neural interface may be adapted to the dorsolateral PFC to provide demand-based treatment in patients with chronic pain. Mechanistically, we found that optogenetic stimulation of the pyramidal neurons in the PL-PFC reduced pain, compatible with previous results(33, 34, 36, 37, 60). In contrast, activation of inhibitory neurons in this region is known to enhance pain(32, 61).

We have shown that we can minimize false detections and improve specificity by integrating neural activities from two distinct brain regions that have complementary roles in pain processing. This approach supports the multidimensional nature of the pain experience. Each cortical region may process a unique aspect of pain, in addition to other behavioral functions. During a pain episode, however, multiple brain regions must activate/inactivate at the same time, and thus a decoder based on activities across multiple nodes of the pain network has a higher likelihood of improving specificity. This decoding approach can be extended to incorporate additional brain structures, such as the insular cortex, to further improve decoding specificity(62).

Another key aspect of our study is the use of LFPs to decode pain in real time. Although spikes provide specific signals at the level of individual neurons, they are likely less stable over long time periods in freely behaving animals and in humans(63, 64). LFPs provide an alternative solution for neural readout(65, 66). In our study, we were able to reliably record LFPs over a period of three months. This signal stability supports the use of LFPs for BMI applications in chronic recording conditions, which is crucial for the management of chronic pain and similar neuropsychiatric diseases. Our decoding model remains stable for five days post-training. The robustness of our model likely results from a combination of signal stability and the use of multi-region decoding, and it shows promise for clinical translation.

In our study, we have tested our therapeutic BMI for acute mechanical and thermal pain, as well as inflammatory and chronic neuropathic pain. The use of multiple preclinical pain models validates our treatment approach, and more importantly it provides a basis for human translational studies. For example, persistent localized inflammation and peripheral neuropathy are common causes of chronic pain in patients. The success of our system in these pain models also indicates that acute and chronic pain share certain mechanistic principles in cortical processing. LFP signals can be recorded from the brains of patients who undergo stereotaxic surgeries, as in the case of the mapping of epileptic foci, and DBS is an approved method for treating brain disorders. Thus, our study can be extended to human studies to test the robustness of pain detection using cortical signals and to verify that a BMI can deliver adequate treatment. Such experiments can in turn pave the way for closed-loop treatment for pain patients.

Several limitations of our work need to be addressed to enable clinical translation. First, despite the use of two regions in decoding pain, we still encountered false detections. These false detections are likely caused by the non-specificity of neuronal firings in the S1 and ACC, and/or by the non-stationarity of neural signals in freely behaving rats. Next steps to improve decoding specificity include incorporating recordings of additional brain regions that could serve as positive and negative controls into our decoding algorithms as well as combining neural signals with real-time behavioral analyses(67). Secondly, although we have demonstrated signal stability over a period of three months, even longer periods of testing are needed for application to chronic pain management. Another limitation of our study is that due to its multi-functionality, stimulation of the PFC can lead to nonspecific effects. Nonspecific side effects are a general issue for neuromodulation treatments and have been observed with existing clinical applications of DBS(68, 69). There are two strategies to minimize non-specific effects: target highly pain-specific neural structures, or limit treatments to a defined period of time. Currently, there is not a single known target in the central nervous system that can reliably treat pain without any side effects, and thus in this study, we have taken up the second strategy of using a closed-loop, demand-based paradigm to restrict neuromodulation to the duration of the detected pain episodes. However, future discoveries of neuronal populations with specific pain-regulatory functions may be adapted to our therapeutic interface to improve treatment specificity. At the same time, our BMI can also be used to facilitate such discoveries. The use of DBS represents another potential limitation of our study. DBS does not directly target specific classes of neurons; however, at lower frequencies such as in the case of our study, it has been shown to enhance cortical outputs (70). Our locomotion tests indicate that DBS of the PL-PFC may be relatively safe; nevertheless, further behavioral testing is needed. In addition, while DBS has been used safely in humans, its safety and efficacy for targeting the homologous PFC region still needs to be evaluated. Finally, while ECoG probes may be used to derive similar decoding results, further improvement of hardware design to enable a biocompatible, portal closed-loop system of decoding and stimulation is needed.

In conclusion, we have designed and tested a multi-region neural interface that produces reliable detection and treatment of pain in rats. The use of LFP signals allows our pain decoder to be compatible with ECoG or even EEG recordings. Given the clinical feasibility of EEG or ECoG recordings and DBS, adaptation of our technology could be a potential step towards a new way of treating chronic debilitating pain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The purpose of this study was to develop and test the performance of a closed-loop neural interface for pain. We hypothesized that our BMI could accurately detect acute pain episodes based on neural activity in the rodent cortex and modulate cortical areas to inhibit pain. Acute pain tests included thermal stimulations using the Hargreaves’ table and mechanical stimulations using pinprick and von Frey filaments. Mechanical stimulations were repeated on models of chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain conditions modeled by CFA and SNI, respectively. Pain decoding was achieved through unsupervised machine learning of LFP data recorded from surgically implanted silicon probes in the S1 and ACC. Pain inhibition was achieved by optogenetic or deep brain stimulation of the PL-PFC and assessed by Hargreaves’ test, mechanical allodynia and CPA or CPP. In each pain experiment, the performance of the BMI system was compared with random or manually controlled stimulations or no stimulations as control. Sample size was informed by previous similar studies. Behavioral and neural data for each of our experiments were collected from N = 10 rats for optogenetic studies (5 ChR2 rats in treatment group and 5 YFP rats in control group), and N = 12 rats for DBS studies (7 rats in CFA group and 5 rats in SNI group). Multiple experimenters in the laboratory participated in the experiment. One experimenter performed surgeries and randomly selected the treatment and control groups. Other experimenters blinded to the treatment conditions performed behavior experiments. No data was excluded.

Statistical analysis

Neural and behavioral data were analyzed offline through custom MATLAB (2018 version, MathWorks) scripts and GraphPad Prism version 8 software (GraphPad). Results were reported and analyzed as mean ± SEM. Comparison between mean values of two groups were evaluated by two-tailed paired t-test, two-tailed unpaired t-test, and two-tailed Wilcoxon test. A one-way ANOVA with repeated measurements and post-hoc multiple pair-wise comparison Tukey’s tests was used to compare the mean differences of more than two groups. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05. Exact P values and sample sizes are shown in figure legends.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-GM115384 (to J.W.), R01-NS121776 (to J.W., Z.S.C.) and NSF grant CBET-1835000 (to Z.S.C., J.W.).

Footnotes

Competing interests: J.W. and Z.S.C. have a provisional patent based on this work (“Closed-loop neural interface for pain control,” USPTO #121587). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or in the Supplementary Materials.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Andersen RA, Aflalo T, Kellis S, From thought to action: The brain–machine interface in posterior parietal cortex. PNAS 116, 26274–26279 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grosenick L, Marshel JH, Deisseroth K, Closed-loop and activity-guided optogenetic control. Neuron 86, 106–139 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanechi MM, Brain–machine interfaces from motor to mood. Nat Neurosci 22, 1554–1564 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergey GK, Morrell MJ, Mizrahi EM, Goldman A, King-Stephens D, Nair D, Srinivasan S, Jobst B, Gross RE, Shields DC, Barkley G, Salanova V, Olejniczak P, Cole A, Cash SS, Noe K, Wharen R, Worrell G, Murro AM, Edwards J, Duchowny M, Spencer D, Smith M, Geller E, Gwinn R, Skidmore C, Eisenschenk S, Berg M, Heck C, Van Ness P, Fountain N, Rutecki P, Massey A, O’Donovan C, Labar D, Duckrow RB, Hirsch LJ, Courtney T, Sun FT, Seale CG, Long-term treatment with responsive brain stimulation in adults with refractory partial seizures. Neurology 84, 810–817 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor DM, Tillery SI, Schwartz AB, Direct cortical control of 3D neuroprosthetic devices. Science 296, 1829–1832 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochberg LR, Serruya MD, Friehs GM, Mukand JA, Saleh M, Caplan AH, Branner A, Chen D, Penn RD, Donoghue JP, Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia. Nature 442, 164–171 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner FB, Mignardot JB, Le Goff-Mignardot CG, Demesmaeker R, Komi S, Capogrosso M, Rowald A, Seanez I, Caban M, Pirondini E, Vat M, McCracken LA, Heimgartner R, Fodor I, Watrin A, Seguin P, Paoles E, Van Den Keybus K, Eberle G, Schurch B, Pralong E, Becce F, Prior J, Buse N, Buschman R, Neufeld E, Kuster N, Carda S, von Zitzewitz J, Delattre V, Denison T, Lambert H, Minassian K, Bloch J, Courtine G, Targeted neurotechnology restores walking in humans with spinal cord injury. Nature 563, 65–71 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willett FR, Avansino DT, Hochberg LR, Henderson JM, Shenoy KV, High-performance brain-to-text communication via handwriting. Nature 593, 249–254 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D, Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 139, 267–284 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis KD, Aghaeepour N, Ahn AH, Angst MS, Borsook D, Brenton A, Burczynski ME, Crean C, Edwards R, Gaudilliere B, Discovery and validation of biomarkers to aid the development of safe and effective pain therapeutics: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Neurol 16, 381–400 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anumanchipalli GK, Chartier J, Chang EF, Speech synthesis from neural decoding of spoken sentences. Nature 568, 493–498 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, Carrier B, Bushnell MC, Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science 277, 968–971 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansen JP, Fields HL, Manning BH, The affective component of pain in rodents: direct evidence for a contribution of the anterior cingulate cortex. PNAS 98, 8077–8082 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaGraize SC, Borzan J, Peng YB, Fuchs PN, Selective regulation of pain affect following activation of the opioid anterior cingulate cortex system. Exp Neurol 197, 22–30 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melzack R. a. C., Sensory KL, motivational, and central control determinants of pain: a new conceptual model. . The Skin Senses, 423–443 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melzack R, Wall PD, Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 150, 971–979 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navratilova E, Xie JY, Okun A, Qu CL, Eyde N, Ci S, Ossipov MH, King T, Fields HL, Porreca F, Pain relief produces negative reinforcement through activation of mesolimbic reward-valuation circuitry. PNAS 109, 20709–20713 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansen JP, Fields HL, Glutamatergic activation of anterior cingulate cortex produces an aversive teaching signal. Nat Neurosci 7, 398–403 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Q, Manders T, Tong AP, Yang R, Garg A, Martinez E, Zhou H, Dale J, Goyal A, Urien L, Yang G, Chen Z, Wang J, Chronic pain induces generalized enhancement of aversion. Elife 6, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H, Zhang Q, Martinez E, Dale J, Hu S, Zhang E, Liu K, Huang D, Yang G, Chen Z, Wang J, Ketamine reduces aversion in rodent pain models by suppressing hyperactivity of the anterior cingulate cortex. Nat Commun 9, 3751 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buzsáki G, Anastassiou CA, Koch C, The origin of extracellular fields and currents—EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 407–420 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pesaran B, Vinck M, Einevoll GT, Sirota A, Fries P, Siegel M, Truccolo W, Schroeder CE, Srinivasan R, Investigating large-scale brain dynamics using field potential recordings: analysis and interpretation. Nat Neurosci 21, 903–919 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao L, Varga V, Chen ZS, Spatiotemporal patterns of rodent hippocampal field potentials uncover spatial representations. bioRxiv, 828467 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khorasani A, Beni NH, Shalchyan V, Daliri MR, Continuous force decoding from local field potentials of the primary motor cortex in freely moving rats. Sci Rep 6, 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stavisky SD, Kao JC, Nuyujukian P, Ryu SI, Shenoy KV, A high performing brain–machine interface driven by low-frequency local field potentials alone and together with spikes. J Neural Eng 12, 036009 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salzman CD, Fusi S, Emotion, cognition, and mental state representation in amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 33, 173–202 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moayedi M, Weissman-Fogel I, Crawley AP, Goldberg MB, Freeman BV, Tenenbaum HC, Davis KD, Contribution of chronic pain and neuroticism to abnormal forebrain gray matter in patients with temporomandibular disorder. Neuroimage 55, 277–286 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geha PY, Baliki MN, Harden RN, Bauer WR, Parrish TB, Apkarian AV, The brain in chronic CRPS pain: abnormal gray-white matter interactions in emotional and autonomic regions. Neuron 60, 570–581 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly CJ, Huang M, Meltzer H, Martina M, Reduced glutamatergic currents and dendritic branching of layer 5 pyramidal cells contribute to medial prefrontal cortex deactivation in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Front Cell Neurosci 10, 133 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radzicki D, Pollema-Mays SL, Sanz-Clemente A, Martina M, Loss of M1 Receptor Dependent Cholinergic Excitation Contributes to mPFC Deactivation in Neuropathic Pain. J Neurosci 37, 2292–2304 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji G, Neugebauer V, Pain-related deactivation of medial prefrontal cortical neurons involves mGluR1 and GABA(A) receptors. J Neurophysiol 106, 2642–2652 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Gadotti VM, Chen L, Souza IA, Stemkowski PL, Zamponi GW, Role of Prelimbic GABAergic Circuits in Sensory and Emotional Aspects of Neuropathic Pain. Cell Rep 12, 752–759 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee M, Manders TR, Eberle SE, Su C, D’Amour J, Yang R, Lin HY, Deisseroth K, Froemke RC, Wang J, Activation of corticostriatal circuitry relieves chronic neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 35, 5247–5259 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez E, Lin HH, Zhou H, Dale J, Liu K, Wang J, Corticostriatal Regulation of Acute Pain. Front Cell Neurosci 11, 146 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hardy SG, Analgesia elicited by prefrontal stimulation. Brain Res 339, 281–284 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiritoshi T, Ji G, Neugebauer V, Rescue of Impaired mGluR5-Driven Endocannabinoid Signaling Restores Prefrontal Cortical Output to Inhibit Pain in Arthritic Rats. J Neurosci 36, 837–850 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dale J, Zhou H, Zhang Q, Martinez E, Hu S, Liu K, Urien L, Chen Z, Wang J, Scaling Up Cortical Control Inhibits Pain. Cell Rep 23, 1301–1313 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Z, Zhang Q, Tong AP, Manders TR, Wang J, Deciphering neuronal population codes for acute thermal pain. J Neural Eng 14, 036023 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.S Z. Q. Hu, Wang J, Chen Z, A real-time rodent neural interface for deciphering acute pain signals from neuronal ensemble spike activity. Proc. Asilomar Conf. Signals, Systems & Computers, 93–97 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh A, Patel D, Li A, Hu L, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Guo X, Robinson E, Martinez E, Doan L, Rudy B, Chen ZS, Wang J, Mapping Cortical Integration of Sensory and Affective Pain Pathways. Curr Biol 30, 1703–1715 e1705 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan LL, Oswald MJ, Heinl C, Retana Romero OA, Kaushalya SK, Monyer H, Kuner R, Gamma oscillations in somatosensory cortex recruit prefrontal and descending serotonergic pathways in aversion and nociception. Nat Commun 10, 983 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao Z, Martinez E, Kulkarni PM, Zhang Q, Hou Q, Rosenberg D, Talay R, Shalot L, Zhou H, Wang J, Chen ZS, Cortical Pain Processing in the Rat Anterior Cingulate Cortex and Primary Somatosensory Cortex. Front Cell Neurosci 13, 165 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Q, Xiao Z, Huang C, Hu S, Kulkarni P, Martinez E, Tong AP, Garg A, Zhou H, Chen Z, Wang J, Local field potential decoding of the onset and intensity of acute pain in rats. Sci Rep 8, 8299 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King T, Vera-Portocarrero L, Gutierrez T, Vanderah TW, Dussor G, Lai J, Fields HL, Porreca F, Unmasking the tonic-aversive state in neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci 12, 1364–1366 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Navratilova E, Xie JY, Meske D, Qu C, Morimura K, Okun A, Arakawa N, Ossipov M, Fields HL, Porreca F, Endogenous opioid activity in the anterior cingulate cortex is required for relief of pain. J Neurosci 35, 7264–7271 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boccard SG, Pereira EA, Moir L, Aziz TZ, Green AL, Long-term outcomes of deep brain stimulation for neuropathic pain. Neurosurgery 72, 221–230; discussion 231 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spooner J, Yu H, Kao C, Sillay K, Konrad P, Neuromodulation of the cingulum for neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Case report. J Neurosurg 107, 169–172 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewin W, Whitty CW, Effects of anterior cingulate stimulation in conscious human subjects. J Neurophysiol 23, 445–447 (1960). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richardson DE, Akil H, Pain reduction by electrical brain stimulation in man. Part 1: Acute administration in periaqueductal and periventricular sites. J. Neurosurg. 47, 178–183 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hosobuchi Y, Adams JE, Linchitz R, Pain relief by electrical stimulation of the central gray matter in humans and its reversal by naloxone. Science 197, 183–186 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turnbull IM, Shulman R, Woodhurst WB, Thalamic stimulation for neuropathic pain. J Neurosurg 52, 486–493 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Decosterd I, Woolf CJ, Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 87, 149–158 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu S, Zhang Q, Wang J, Chen Z, Real-time particle filtering and smoothing algorithms for detecting abrupt changes in neural ensemble spike activity. J Neurophysiol 119, 1394–1410 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Büchel C, Bornhövd K, Quante M, Glauche V, Bromm B, Weiller C, Dissociable neural responses related to pain intensity, stimulus intensity, and stimulus awareness within the anterior cingulate cortex: a parametric single-trial laser functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosci 22, 970–976 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hutchison WD, Davis KD, Lozano AM, Tasker RR, Dostrovsky JO, Pain-related neurons in the human cingulate cortex. Nat Neurosci 2, 403–405 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sikes RW, Vogt BA, Nociceptive neurons in area 24 of rabbit cingulate cortex. J Neurophysiol 68, 1720–1732 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kang SJ, Kwak C, Lee J, Sim SE, Shim J, Choi T, Collingridge GL, Zhuo M, Kaang BK, Bidirectional modulation of hyperalgesia via the specific control of excitatory and inhibitory neuronal activity in the ACC. Mol Brain 8, 81 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vertes RP, Interactions among the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and midline thalamus in emotional and cognitive processing in the rat. Neuroscience 142, 1–20 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Metz AE, Yau H-J, Centeno MV, Apkarian AV, Martina M, Morphological and functional reorganization of rat medial prefrontal cortex in neuropathic pain. PNAS 106, 2423–2428 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheriyan J, Sheets PL, Altered Excitability and Local Connectivity of mPFC-PAG Neurons in a Mouse Model of Neuropathic Pain. J Neurosci 38, 4829–4839 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang J, Gadotti VM, Chen L, Souza IA, Huang S, Wang D, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Zhang Z, Zamponi GW, A neuronal circuit for activating descending modulation of neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci 22, 1659–1668 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiao Z, Hu S, Zhang Q, Tian X, Chen Y, Wang J, Chen Z, Ensembles of change-point detectors: implications for real-time BMI applications. J Comput Neurosci 46, 107–124 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang D, Zhang QS, Li Y, Wang YW, Zhu JM, Zhang SM, Zheng XX, Long-term decoding stability of local field potentials from silicon arrays in primate motor cortex during a 2D center out task. J Neural Eng 11, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chestek CA, Gilja V, Nuyujukian P, Foster JD, Fan JM, Kaufman MT, Churchland MM, Rivera-Alvidrez Z, Cunningham JP, Ryu SI, Shenoy KV, Long-term stability of neural prosthetic control signals from silicon cortical arrays in rhesus macaque motor cortex. J Neural Eng 8, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flint RD, Wright ZA, Scheid MR, Slutzky MW, Long term, stable brain machine interface performance using local field potentials and multiunit spikes. J Neural Eng 10, 056005 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nason SR, Vaskov AK, Willsey MS, Welle EJ, An H, Vu PP, Bullard AJ, Nu CS, Kao JC, Shenoy KV, Jang T, Kim HS, Blaauw D, Patil PG, Chestek CA, A low-power band of neuronal spiking activity dominated by local single units improves the performance of brain-machine interfaces. Nat Biomed Eng 4, 973–983 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Langford DJ, Bailey AL, Chanda ML, Clarke SE, Drummond TE, Echols S, Glick S, Ingrao J, Klassen-Ross T, Lacroix-Fralish ML, Matsumiya L, Sorge RE, Sotocinal SG, Tabaka JM, Wong D, van den Maagdenberg AM, Ferrari MD, Craig KD, Mogil JS, Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat Methods 7, 447–449 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alomar S, King NK, Tam J, Bari AA, Hamani C, Lozano AM, Speech and language adverse effects after thalamotomy and deep brain stimulation in patients with movement disorders: A meta-analysis. Mov Disord 32, 53–63 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beric A, Kelly PJ, Rezai A, Sterio D, Mogilner A, Zonenshayn M, Kopell B, Complications of deep brain stimulation surgery. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 77, 73–78 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levy RM, Lamb S, Adams JE, Treatment of chronic pain by deep brain stimulation: long term follow-up and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 21, 885–893 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bokil H, Andrews P, Kulkarni JE, Mehta S, Mitra PP, Chronux: a platform for analyzing neural signals. J Neurosci Methods 192, 146–151 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun G, Wen Z, Ok D, Doan L, Wang J, Chen ZS, Detecting acute pain signals from human EEG. J Neurosci Methods 347, 108964 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or in the Supplementary Materials.