Abstract

Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the commentary by Kim-Mozeleski and colleagues on “Food insecurity transitions and smoking behavior among older adults who smoke”. This study examined the influence of food insecurity transitions on smoking cessation and daily cigarette consumption in 2014 within a sample of older U.S. adults from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) who indicated that they smoked in 2012. In particular, Kim-Mozeleski and colleagues highlight that findings of Bergmans (2019) contrast with results of a previous publication by Kim-Mozeleski and colleagues. In sum, it is not readily apparent why findings contradict those of Kim-Mozeleski et al. (2018). Moderation or confounding due to macroeconomic factors that influence health and behavior is a possibility. Bergmans (2019) examined associations over a recent 2-year period of U.S. economic growth. In contrast, data from Kim-Mozeleski et al. (2018) spanned 12 years and overlapped the Great Recession. A detailed response to the commentary is provided.

Keywords: Food insecurity, Smoking behavior

Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the commentary on “Food insecurity transitions and smoking behavior among older adults who smoke” Bergmans (2019). In particular, Kim-Mozeleski and colleagues highlight that findings of Bergmans (2019) contrast with their previous publication (Kim-Mozeleski et al., 2018).

First, Kim-Mozeleski and colleagues question whether analyses modeled smoking cessation or smoking continuation. Multivariable logistic regression models tested the association of food insecurity transitions with smoking cessation. Smoking cessation was treated as a binary variable: no longer current smokers vs. current smokers (reference group). Indeed, an initial misprint within the manuscript text indicated that the reference group was “no longer current smokers”. However, this has since been revised in the published manuscript and at no point was this error made within statistical analyses or reporting of results. Additionally, findings of Bergmans (2019) were consistent with results of a prior, independent analysis of smoking cessation in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) (Quiñones et al., 2017). Quiñones et al. (2017) observed that being diagnosed with a health condition was associated with greater smoking cessation. Using receipt of a new health diagnosis as a covariate in analyses, Bergmans (2019) also observed it to be associated with greater smoking cessation, which externally validates that smoking cessation was correctly modeled.

Second, Kim-Mozeleski and colleagues question the use of multinomial logistic regression to examine associations of food insecurity transitions with changes in daily cigarette consumption. A primary strength of multinomial logistic regression is to assess differential effects for each pairing of independent and dependent variable categories. Pernenkil et al. (2017) in addition to Bergmans (2019) observed that smoking reductions may be greater among those with fewer financial resources, contradicting findings by Kim-Mozeleski et al. (2018). In a representative sample of U.S. adults from 2003 to 2012, smoking cessation was greater among those with low socioeconomic status than those with high socioeconomic status (Pernenkil et al., 2017). This further supports using multinomial logistic regression to examine whether food insecurity transitions were associated with either an increase or a decreases in cigarette consumption.

Third, Kim-Mozeleski and colleagues state that findings among women “signal that there is an association between food insecurity and smoking status (whether one is a smoker or not) but cannot disentangle whether it changes the quantity of cigarettes consumed”. This is a misinterpretation because the reference group for daily cigarette consumption represented smokers with no change in cigarette consumption—categorically including only those who still smoked, and excluded nonsmokers. The comparison categories were (a) those who reported smoking more cigarettes per day in 2014 than 2012, and (b) those who reported smoking fewer cigarettes per day in 2014 than 2012, or stopped smoking in 2014.

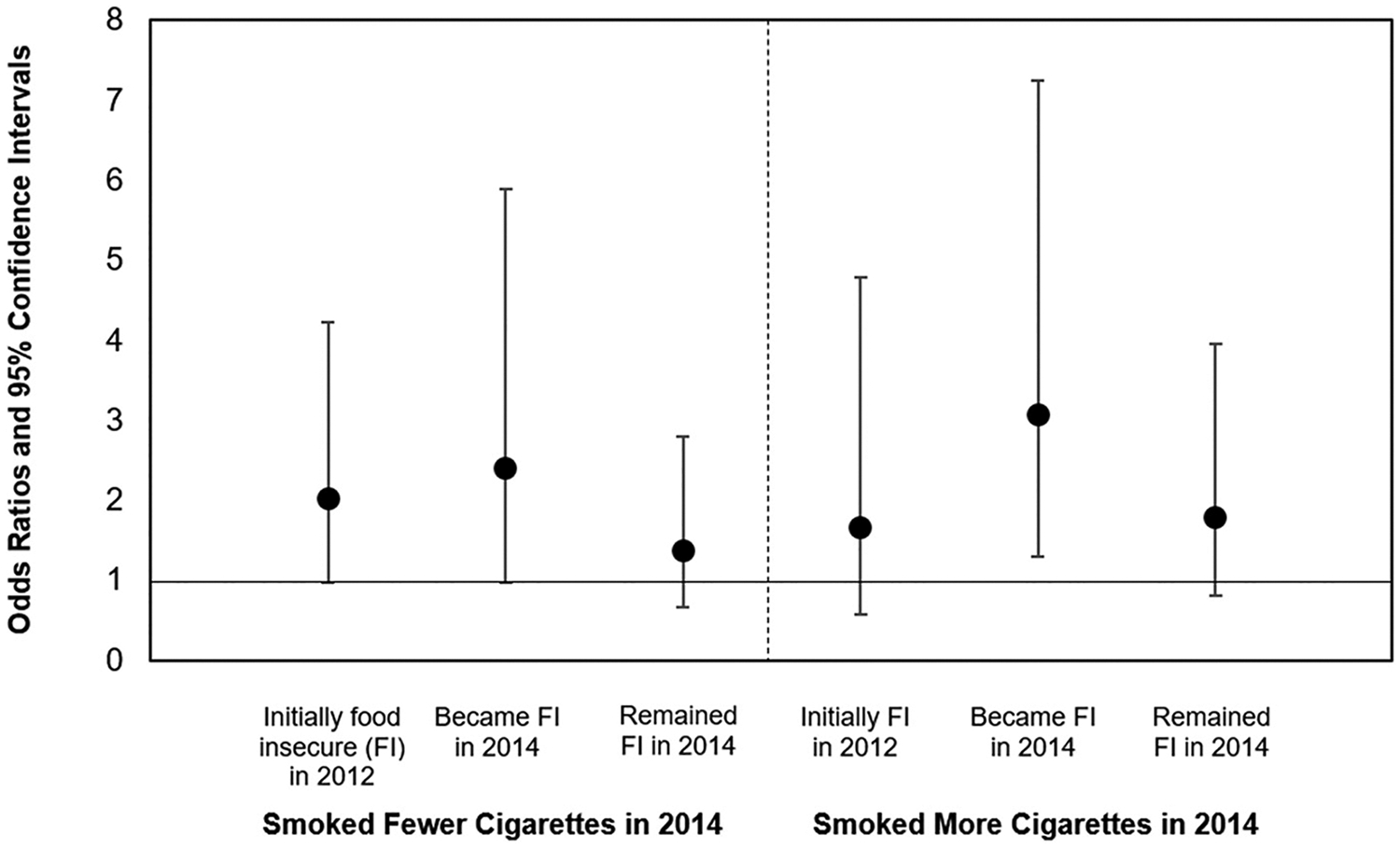

Fourth, Kim-Mozeleski and colleagues suggest that study conclusions would be influenced by re-characterizing the measure for daily cigarette consumption, such that “smoking fewer cigarettes” no longer includes those who stopped smoking in 2014. When repeating analyses as suggested, becoming food insecure is still associated with smoking more cigarettes (odds ratio (OR) = 3.1; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.3–7.2) and; is now only marginally associated with smoking fewer cigarettes (OR = 2.4; 95% CI = 1.0–5.9) among women (Fig. 1). This is consistent with initial findings by Bergmans (2019), which demonstrated that becoming food insecure was associated with smoking cessation among men and women and; smoking more cigarettes per day among women who continued to smoke.

Fig. 1.

Multinomial logistic regression for the association of food insecurity transition with daily cigarette consumptiona among women who smoke, HRSb 2012–2014c–e.

aNumber of cigarettes per day in 2014 vs. 2012; reference = same number/no change.

bU.S. Health and Retirement Study.

cn (men and women) = 1813; n (women sub-sample) = 981.

dAccounting for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, household income-to-poverty ratio, work status, retirement status, change in household income-to-poverty ratio, employment transition and being diagnosed with a new health condition.

eFood insecurity transition and gender interaction p-value = 0.034.

To conclude, it is not readily apparent why findings contradicted those of Kim-Mozeleski et al. (2018). Moderation or confounding due to macroeconomic factors that influence health and behavior is a possibility (Pernenkil et al., 2017; Margerison-Zilko et al., 2016). Bergmans (2019) examined associations over a recent 2-year period of U.S. economic growth. In contrast, the two waves of data used by Kim-Mozeleski et al. (2018) spanned 12 years and overlapped the Great Recession.

Declaration of competing interest

RSB is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH T32-MH73553). The NIMH did not have any role in study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure

No financial disclosures were reported by the author of this paper.

References

- Bergmans RS, 2019. Food insecurity transitions and smoking behavior among older adults who smoke. Prev. Med 126, 105784. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Mozeleski JE, Seligman HK, Yen IH, Shaw SJ, Buchanan DR, Tsoh JY, 2018. Changes in food insecurity and smoking status over time: analysis of the 2003 and 2015 panel study of income dynamics. Am. J. Health Promot. 33 (5), 698–707 (0890117118814397). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margerison-Zilko C, Goldman-Mellor S, Falconi A, Downing J, 2016. Health impacts of the great recession: a critical review. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep 3 (1), 81–91. 10.1007/s40471-016-0068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernenkil V, Wyatt T, Akinyemiju T, 2017. Trends in smoking and obesity among US adults before, during, and after the great recession and Affordable Care Act roll-out. Prev. Med 102, 86–92. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiñones AR, Nagel CL, Newsom JT, Huguet N, Sheridan P, Thielke SM, 2017. Racial and ethnic differences in smoking changes after chronic disease diagnosis among middle-aged and older adults in the United States. BMC Geriatr. 17 (1), 48. 10.1186/s12877-017-0438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]