Abstract

Purpose and Objectives:

American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) hypertension contributes to cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of premature death in this population. The purpose of this article is to document strategies, concerns, and barriers related to hypertension and cardiovascular disease from Native-Controlling Hypertension and Risks through Technology (Native-CHART) symposiums facilitated by the Center for Native American Health (CNAH). The objectives of this evaluation were to combine Health Needs Assessment (HNA) data and explore barriers and strategies related to hypertension while assessing changes in participants’ perspectives over time (2017-2021).

Approach:

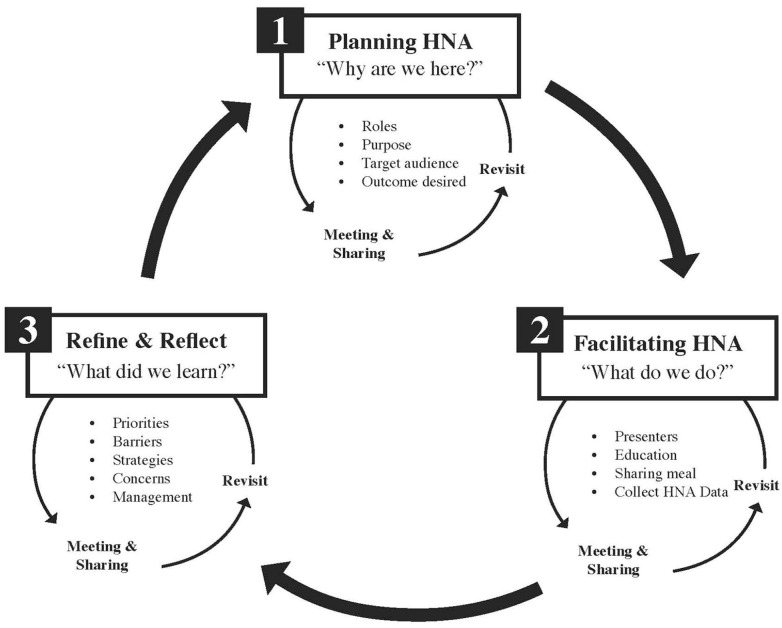

CNAH followed an iterative process each year for planning the HNA, facilitating the HNA, and refining and reflecting on HNA findings over time. This involved 3 interconnected steps: (1) developing a shared understanding for the HNA, “Why are we here?,” (2) facilitating the HNA during annual symposiums “What do we do?,” and (3) reflecting on “What did we learn?”.

Evaluation Methods:

Data were collected using a culturally centered HNA co-created by the CNAH team and tribal partners. Qualitative data analysis utilized a culturally centered thematic approach and NVivo software version 12.0. Quantitative data analysis included summarizing frequency counts and descriptive statistics using Microsoft Excel.

Results:

Over the 5-year period, 212 Native-CHART symposium participants completed HNAs. Data collected from HNAs show persistent barriers and concerns and illuminate potential strategies to address AI/AN hypertension. Future efforts must explore effective strategies that build on community strengths, culture and traditions, and existing resources. This is the path forward.

Implications for Public Health:

CNAH’s culturally centered and unique HNA approach helped assess participant perspectives over time. CNAH facilitated symposiums over multiple years, even amid a global pandemic. This demonstrates resilience and continuity of community outreach when it is needed the most. Other universities and tribal partners could benefit from this iterative approach as they work to design HNAs with tribal populations.

Keywords: health needs assessment, hypertension, American Indian Alaska Native, planning

Introduction

American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) hypertension contributes to cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of premature mortality.1 The Indian Health Care Improvement Act, Public Law 102-573 called for reducing coronary heart disease to a level of no more than 100 per 100 000 persons. This objective has not been met. Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and related disparities continue to impact AI/AN populations more than other populations in the US.2-4 Increases in hypertension among AI/AN populations are related to socio-cultural and environmental factors including colonization, trauma, discrimination, and post-colonial oppression.5,6 Other factors that contribute to increased hypertension risk in AI/AN populations include a poor diet, limited physical activity, obesity, diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, tobacco use, family history, poor mental health, and environmental exposures.7-10 For each risk factor, there is a unique history and understanding of risk that is required. An example is diet. For thousands of years, AI/AN populations have relied on traditional foods (berries, dry meat, wild turnips) and exerted food sovereignty, however, colonization disrupted traditional food systems, and forced AI/AN populations onto reservations which decreased access to traditional foods and hunting and disrupted their traditional ways of life that supported generational wellbeing.11 Understanding the complexity of hypertension causes, risk factors, and solutions within AI/AN populations requires a systematic and thoughtful approach to collecting data.

Accessing AI/AN health data is difficult due to small population sizes, inconsistent classifications of AI/AN status on death certificates and in clinical settings, and differences in how diseases are classified and reported in community-based settings.3 Moreover, AI/AN community views about hypertension are influenced by culture, context, and language. Thus, documenting AI/AN specific hypertension needs concerns with members of the AI/AN communities is an essential step in addressing premature mortality.

AI/AN communities have been assessing their health and well-being status for thousands of years.6 Traditionally, AI/AN communities used oral traditions, passed down from one generation to the next, to document wellness-related topics. In non-AI/AN communities, health needs assessments (HNAs) started in the US during the 1800s with medical officers assessing the health needs of their local populations.12 Today, HNAs are often used to document needs, and sometimes strengths, while creating opportunities to address health-related concerns. Other terms utilized within the HNA milieu include community health assessment (CHA) or community health needs assessment (CHNA), and community health needs and strengths survey.13 While different terms are used, the purpose is similar, to identify key health needs and issues through systematic and comprehensive data collection and analysis. Generally, HNAs are part of a larger planning and evaluation process, for example, prioritizing issues, developing plans to address issues, and implementing and evaluating efforts for maximum impact. In some instances, HNAs are a requirement tied to funding. States receiving Title V funding must prepare a state-wide HNA every 5 years documenting their health status goals and national health objectives. With AI/AN populations, HNAs are related to the US federal government’s trust responsibility to maintain, improve, and assure the highest possible health status. For example, the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, Title V, Section 504, requires urban AI/AN locations to determine the health status and needs of tribal constituents. In other examples tribes as sovereign nations are required to conduct HNAs as a required activity tied to federal grants from agencies like the Indian Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.14

Some AI/AN communities feel that the HNA process is colonial, western, bureaucratic, oppressive, and deficit-focused.15 Within AI/AN communities, HNA’s conducted by non-tribal members have been used to get funding, support, or bring attention to health-related issues without attention or respect to culture, protocols and potential community harms. Thus, the history of HNAs requires a balance of planning the HNA, identifying and adapting the appropriate methods including the community in the planning process, and doing the work in a culturally appropriate and respectful manner. HNAs may help define or monitor a health-related problem, such as hypertension, when done in a decolonized, transparent, and ethical manner.16,17 However, the process in which HNA’s occur with AI/AN populations is not well documented or understood.

This paper fills a gap in the existing literature by outlining the planning process and outcomes of implementing an AI/AN HNA over a 5-year period in New Mexico with the Native-Controlling Hypertension and Risks through Technology (Native-CHART) study.

Purpose and Objectives

The purpose of the HNA was to document strategies, concerns, and barriers to tribal hypertension from participants attending the Native-CHART symposiums facilitated by the Center for Native American Health (CNAH). The objectives of this evaluation were to combine HNA data and explore barriers and strategies related to hypertension while assessing changes in participants’ perspectives over time (2017-2021).

Native-CHART Description

The Native-CHART study was implemented by Washington State University from 2017 to 2022 (https://ireach.wsu.edu/nchart/). Native-CHART’s overall goal was to improve control of blood pressure (BP) and associated cardiovascular and stroke risk factors among AI/AN, and Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander (NHPI) populations. The long-term goal of Native-CHART is to generate findings that can be translated into practical policy, organizational change, and treatment innovations that will optimize patient-centered health outcomes and reduce or eliminate hypertension-related health disparities in underserved minority communities. CNAH at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNM HSC) (https://hsc.unm.edu/cnah/) served as one of the Native-CHART satellite centers which was part of the Consortium and Dissemination Cores for the southwest region. CNAH planned and facilitated the Native-CHART symposiums in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2021. One of the goals of the Native-CHART symposiums was to communicate Native-CHART research results using culturally appropriate methods to reach healthcare providers, government agencies, community-based organizations, patients, and AI/AN and NHPI communities.

Reflective Health Needs Assessment Approach

CNAH followed an iterative process each year for planning, facilitating, refining, and reflecting on findings over time (Figure 1). This involved 3 interconnected steps: (1) developing a shared understanding for the HNA, “Why are we here?,” (2) facilitating the HNA during annual symposiums “What do we do?,” and (3) reflecting on “What did we learn?”

Figure 1.

CNAH’s intentional HNA process.

Step 1. Planning

CNAH hosted an orientation meeting on April 7, 2017. This meeting focused on stakeholder engagement, strategic planning, and orienting participants to the Native-CHART study. Planning the HNA involved multiple meetings with tribal stakeholders and organizations and reviewing existing hypertension data on AI/ANs in New Mexico. During the planning process, existing quantitative data was shared that documented hypertension prevalence and trends. For example, heart disease was the second leading cause of death among AI/ANs in New Mexico from 2014 to 2018.18 Heart disease mortality among AI/AN males in New Mexico was 186.4 per 100 000 persons which is more than double the female rate of 88.3 per 100 000 persons.18 Hypertension diagnoses and related risk factors are common, 30% of AI/ANs served by the Albuquerque Area Indian Health Service have been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, 75% overweight or obese, and 35% of males and 28% of females have been diagnosed with hypertension.18 Open-ended questions included in the HNA explored why and how hypertension disparities exist among AI/AN populations in New Mexico, with a focus on barriers and strategies).

Step 2. Facilitating the HNA

CNAH collected HNAs during 4 Native-CHART symposiums on December 8, 2017, April 14, 2018, November 8, 2019, and January 8, 2021. Symposiums were culturally centered and highlighted tribal community strengths and effective approaches to hypertension treatment. Presenters shared information and resources generated by the Native-CHART study and traditional healers discussed the use of traditional medicine, culture-based interventions/treatment, and healthy lifestyles.

Step 3. Refining and Reflecting

After each symposium, CNAH reviewed and analyzed HNA data. Findings from HNAs were shared with the Native-CHART study team to inform them of priority areas for future Native-CHART symposiums and research. For example, HNA highlights and strategies compiled from the 2017 symposium were to collaborate with community health representatives (CHRs) and public health nurses, use strength-based approaches, and culture-based interventions, address diabetes and obesity, and explore gender differences and risk factors. These topics were then incorporated into the planning process for the second Native-CHART symposium in 2018. This iterative process to refine, reflect, and understand HNA data occurred before and after each symposium.

Symposium overview

CNAH led 4 symposiums over a 5-year period. The target symposium audience was tribal leaders, community members, and tribal health professionals in New Mexico. Symposiums covered a variety of topics including stroke and stroke risk, hypertension, diabetes, kidney disease, vascular dementia, traditional medicine, and technology. Native-CHART study findings were also disseminated during symposiums via resource materials and presenters.

Evaluation methods and analysis

Members of the Native-CHART CNAH planning team developed a set of questions for the HNA related to hypertension during the planning phase (step 1). The HNA included open-text and multiple-choice questions using in-person, paper methods, and Qualtrics (online survey) immediately following the symposiums. The CNAH team also documented symposium highlights, via note-taking, and recorded questions and concerns from the audience. An external evaluator analyzed HNA data using NVivo version 12.0 and Microsoft Excel. Qualitative data were analyzed by variable type and major theme based on the HNA questions and following a culturally centered thematic analysis approach. The themes were categorized by strategies, concerns, barriers, and what participants still need to learn. Quantitative data in the form of frequency counts and participant types were entered into Microsoft Excel.

Results

Over the 5-year period, 212 Native-CHART symposium participants completed HNAs (Table 1). Attendance varied by year, providers were the largest group of individuals represented at annual symposiums followed by researchers and academics (Table 1). Moreover, the HNA data were organized by year and major themes (Table 2).

Table 1.

HNA Respondents by Year and Role.

| Year | Community/tribal organization | Tribal leadership | Researcher/academic | Provider | State/IHS | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 29 |

| 2018 | 25 | 2 | 29 | 54 | 1 | 8 | 119 |

| 2019 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 14 | 31 |

| 2021 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 0 | 11 | 33 |

| Total | 41 | 8 | 44 | 71 | 8 | 40 | 212 |

Table 2.

Themes: Barriers, Strategies, and Concerns Related to Hypertension by Year.

| Year | Barriers | Strategies | Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017a | Funding issues, silos, problematic health systems, changes in tribal leadership materials are too technical, not strength based limited data, for example for males, youth, gender differences | Assistance in developing standardized education materials, and culturally appropriate integrate traditional healing into western medical practice | Diabetes, gestational diabetes, obesity, and youth impacts |

| 2018a | Cultural sensitivity, use of traditional aspects, traditional healers not used, systemic issues, integration of care, transport, expenses, lack of follow-up, the impact of government culture | Cultural sensitivity, traditional foods, traditional healer, cultural competency, cultural relevance reciprocity in education, learning between patients and providers, gender and cultural differences | Hypertension, obesity, diabetes, sedentary lifestyle, cholesterol, risk factors, and risky behaviors, such as smoking |

| 2019b | Unhealthy lifestyle, being overweight or obese, lack of understanding | Assistance with standardized education materials, learning what other communities are doing, training sessions for providers, community, and staff | Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, unhealthy behaviors, elevated cholesterol, pre-diabetes, and coronary heart disease |

| 2021b | Unhealthy lifestyle, lack of understanding, lack of community resources, limited health literacy, being overweight/obese | Conduct training sessions for programing and strategic plans, learning what other communities are doing, assistance with standardized education materials, assistance with cost-effectiveness | Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, unhealthy behaviors, pre-diabetes, coronary heart disease |

Data from qualitative summaries completed by CNAH team during the symposium (based on local data collected, post-it notes, World Café session, and discussions).

Data from an online quantitative survey completed by participants after the symposium, includes responses with 50% or more of participants selecting barrier/strategy.

Barriers

The 2017 and 2018 HNA findings suggest funding is a significant barrier, “[. . .]Tribal leaders need to advocate for continuous funding, this is difficult when tribal leadership can change yearly.” Providers also mentioned funding in the 2018 HNA. For example, one provider mentioned that “reimbursement for telemedicine, limited resources, and the administrative process involved to approve the use of finances [is a significant barrier].” However, in subsequent years (2019-2021), funding was not mentioned as a common barrier, but unhealthy lifestyles, lack of community resources, and understanding were. A 2018 participant wrote, “A barrier and priority area are how to make a return home medically safe while still having your family, whom you trust [with you].” Another 2019 participant wrote, “There is a lack of education in health to assist the population in using their native foods and teaching them how to use native foods in a healthier way.” In 2019 systemic issues were mentioned and a need for “\integration of care, coordination of care, transportation, [and] coverage for expenses related to care to increase the likelihood of follow-up.” In contrast, the 2021 HNA findings suggest that barriers were related to unhealthy lifestyles, lack of resources, and limited health literacy.

Strategies

HNA strategies to address hypertension were related to cultural sensitivity, community education, programing, and the integration of community cultural practices into risk reduction efforts. In 2017 and 2018 the most frequent responses to helpful strategies were cultural sensitivity, reciprocity in education, listening, and traditional healers. One participant expressed the importance of cultural sensitivity, “The use of traditional foods for nutrition and a traditional healer in the referral system [. . .]we must emphasize cultural sensitivity and competency.” One 2019 participant wrote, “[. . .]strategies must address culturally sensitive topics that also align with beliefs.” Another reflected, “Community policy programs to promote healthy eating and fitness throughout the life cycle are a fundamental part of the community.” Another participant in 2021 wrote, “Community education to increase knowledge and understanding about hypertension and cardiovascular risk factors and the treatment and prevention, including traditional cultural practices.” During this same symposium, a participant reflected on necessary strategies, “[Our community needs the] implementation of traditional cultural practices and knowledge to reduce hypertension and cardiovascular risks.”

Concerns

HNA’s documented participants’ concerns related to hypertension. For example, diabetes was mentioned in all HNAs as a primary concern followed by hypertension, gestational diabetes, risky behaviors, and addressing the cycle of obesity and risk factors in youth. Other HNA findings suggest that data access is a major issue, with differences in urban and tribal data, data sharing, and data classification. Technology was also a concern, with many tribal communities not having equitable access to the required technology needed to control diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases.

Still need to learn

CNAH collected resonating thoughts from the 2018 symposium participants. During the symposium, participants discussed the need to address the social determinants of health and the interplay between substance abuse, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and stroke risks. Some felt that learning from one another is necessary, where patients learn from providers and providers learn from patients. Others wrote about learning how to integrate culture, prevention, and addressing the dominant culture:

What are the roles of CHRs in stroke prevention and early detection?—2017 Symposium, Table Discussion

How do we change or integrate medical information into the individual’s cultural milieu?—2018 Symposium, Participant

We need to recognize the impact of culture, customs, education, and prevention. . .. we need the government to help not hinder.—2018 Symposium, Participant

We need to learn about diabetes, and hypertension, how to make education accessible, the dominant culture, and how to avoid discrimination.—2019 Symposium, Participant

Provider perspectives

The HNA included 2 additional questions for providers regarding the specific needs for hypertension in their practice. These are listed in the table below as barriers and strategies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Provider Perspectives on Hypertension Barriers and Strategies.

| Year | Barriers | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| 2017a | Systemic issues, rural challenges, language and cultural differences, distinct and unique communities, medicine is not sufficient to heal | Community health teams support patients, use of CHRs in the community, provider/nurse case management meetings, indigenous health clinic visits |

| 2018 | No provider data collected | |

| 2019b | Systemic barriers, uncertainty about home blood pressure equipment/monitoring, lack of education, lack of monitoring devices | List of patient self-management guidelines, comprehensive education materials, funding for ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring devices, consistent internal practice guidelines |

| 2021b | Systemic barriers, uncertainty about home blood pressure equipment/monitoring, medication costs and adherence, lack of education materials | Funding for ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring devices, list of patient self-management guidelines, comprehensive education materials, funding for care navigators |

Based on symposium notes from 2017 provider/panel perspectives.

Data from an online quantitative survey completed by participants after the symposium, includes responses with 50% or more of participants selecting barrier/strategy, 2019 (n = 3), and 2021 (n = 7).

We explored differences in responses over time from participants and providers. This included data collected pre-COVID (2017-2019) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (2021). The team expected to see differences in barriers and strategies but qualitative analysis revealed limited differences. HNAs did not include specific information related to COVID-19 and hypertension prevention and control.

Limitations

Although the HNA presented here demonstrates an iterative and culturally centered process, there are a few limitations. First, different data collection methods were utilized throughout the 5-year HNA process. Data collected in 2017, the first year of the HNA process was exploratory in nature, and there was not a common or shared set of barriers or strategies that could be included in a fixed response survey. While the data from 2017 was used to populate survey fields in the future HNA years, direct comparison of year-to-year data is subject to these limitations. Second, the HNA was specific to the Native-CHART study and documented hypertension barriers, strategies, and concerns. It is likely that participants are concerned about other health-related issues, but these were not addressed by the Native-CHART study (ie, poverty and unemployment, post-colonial oppression, or broader determinants of health).6,19 Tribal leaders specific to New Mexico Pueblos change frequently, perspectives presented here are not representative of all the Tribal leaders in the southwest region. Finally, while the HNA elevates tribal and tribal provider perspectives while demonstrating an academic-tribal planning process, it may not be appropriate for use in every tribal community or academic partnership. Tribes are unique in their culture, traditions, and practices. These must be upheld and honored during the HNA process.

Discussion

The HNA outlined here addresses an important gap in the literature by presenting an approach to plan, implement, and reflect on hypertension barriers, concerns, and strategies over time. This process may be particularly useful for primary care clinics, policy makers, researchers, and professionals as they work together to address chronic diseases like hypertension. With support from the Native-CHART study, CNAH continuously engaged a diverse group of tribal members, tribal leaders, community partners, providers, staff from the State of New Mexico and Indian Health Service, researchers, and others to explore hypertension. CNAH’s engagement approach is consistent with HNA literature where value is placed on cooperation, collaboration, and partnerships to achieve common goals.6 CNAH’s process, planning, and implementation, occurred over a 5-year period, and during the global COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, most assessments conducted with AI/AN populations are conducted at one point in time for a specific reason, like a funding agency requirement.6 Administering the HNA over multiple years allowed the team to observe changes over time, and engage additional community members (as defined above) in the process. Time also allowed CNAH to implement a 3-step process that has not been used or published before, where the steps are: (1) develop a shared understanding for the HNA, “Why are we here?,” (2) facilitate the HNA during annual symposiums “What do we do?,” and (3) reflect on “What did we learn?.” Information collected during this process was then used to create content and future symposium agendas, train community members, inform tribal leaders, and redirect hypertension resources and research. However, implementing the HNA during the COVID-19 pandemic required a significant shift in how CNAH planned and implemented the symposiums. The 2020 symposium was canceled, and in 2021 planning meetings and the actual symposium was virtual due to meeting restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2021 virtual symposium required online-data collection methods, whereas in-person symposiums included paper and pen surveys, interviews, and in-person meetings for planning and reflecting. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic and disproportionate mortality rates that AI/AN communities experienced,20 there were limited qualitative differences in barriers and strategies presented to address hypertension. This is likely because the HNA focused on hypertension barriers, concerns, and strategies rather than COVID-19.

One distinct characteristic of CNAH’s approach is how community is defined. Most assessments focus on a tribal community or one geographic region.13 For example one tribal CHA process involved collecting data from Tribal members who were eligible for health services living on the Reservation.21 However, in this HNA, the community is a collective group of individuals, tribes, providers, and programs working to address hypertension and related risk factors. During the planning process, these community members knew that hypertension was a serious health concern, they shared health-related data (eg, from the Native-CHART study, Indian Health Service and tribal stakeholders) and had knowledge of resources, policy, and needs. A traditional community (as defined by geographic area or tribe) may not have access to this data3 or knowledge in the planning process.

Accessing data related to hypertension in AI/AN populations is difficult. The data collected and presented in this HNA are distinct from other assessments which often focus on quantitative data, for example rankings, prevalence, or Likert-type scales. Some assessments document the burden of disease using clinical data from the Indian Health Service,22 but these data generally only reflect need and quantitative indicators. They tell readers what the problem is, but not why it exists or how to address it. Qualitative data gathered from this iterative HNA process goes beyond assessing need, it explores why hypertension is an issue, what the barriers are, strategies to address hypertension, and what people still need to learn. Some of the barriers identified in the HNAs are funding, limited resources, lack of education, lack of health care access, limited health literacy, and unhealthy lifestyles. Barriers and concerns are balanced by suggested strategies to address hypertension including assistance with developing educational materials that are culturally appropriate, integration of traditional healing into western medical practice, cultural sensitivity, reciprocity, and sharing lessons learned from other communities. These strategies are consistent with recommendations found in existing literature where restoring traditional healing and lifeways23 and culturally-tailored approaches to reduce chronic disease risk factors are necessary24 to address cardiometabolic disease pathways.25 By documenting the barriers and concerns, tribes may advocate for increased funding, services, policy change, and programing to affect change.

CNAH’s HNA approach and findings could be used to address policy issues and underlying factors that contribute to health disparities in AI/AN communities and other underserved populations.2 Existing literature advocates for policies that direct resources and support for culturally-informed clinical interventions with AI/AN populations while addressing cultural differences and limited resources—the Native-CHART study is one example of progress in this area. However more work is needed. Some policies such as the Indian Health Care Improvement Act Public Law 102-573 allocate additional funding, but they do not address the underlying causes of a health disparity such as hypertension. One key finding from the HNA is that there is still more to learn about hypertension. Providers feel there are systemic issues that create barriers to care. While providers did not specify issues, these could be associated with structural determinants stemming from colonization including exclusion, oppression, discrimination, and loss of control.26 These translate to a broken health system, staffing issues, poor surveillance, limited prevention, and ultimately premature death from cardiovascular diseases.1

Conclusion

To address extant disparities in AI/AN health, it is essential for universities, researchers, communities, tribal leaders, and tribal health professionals to document needs, identify, barriers, and explore strategies to address them. Solutions must come from within the community, as the community is often the healer.27

CNAH’s HNA demonstrated here is intentional, reflective, and connected. CNAH’s Native-CHART team created annual symposium agendas that met the needs and concerns of tribal professionals and tribal providers. Symposiums increased access to resources, research, and technology but many feel that hypertension in AI/AN populations is not the issue. The issue is in addressing the interplay of multiple contributing factors and structural determinants in tribal communities that place individuals at risk for premature death. Future efforts must explore effective strategies that address structural and institutional inequities while building on community strengths, culture, and existing resources in tribal communities. This is the path forward.

Medicine is not sufficient on its own to heal. . .we need to learn community and collaborative approaches, customized to the people we are working with. − 2017 Native-CHART Symposium Participant

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD011240. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iD: Allyson Kelley  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4127-3975

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4127-3975

References

- 1. Espey DK, Jim MA, Cobb N, et al. Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 3):S303-S311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson PJ, Blewett LA, Call KT, Davern M. American Indian/Alaska Native uninsurance disparities: a comparison of 3 surveys. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1972-1979. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rhoades DA. Racial misclassification and disparities in cardiovascular disease among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1250-1256. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157735.25005.3F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warne D, Wescott S. Social determinants of American Indian nutritional health. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(Suppl 2):12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khoury L, Tang YL, Bradley B, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ. Substance use, childhood traumatic experience, and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban civilian population. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(12):1077-1086. doi: 10.1002/da.20751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomas LR, Donovan DM, Sigo RLW. Identifying community needs and resources in a native community: a research partnership in the pacific Northwest. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2010;8(2):362-373. doi: 10.1007/s11469-009-9233-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e563-e595. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bakhru A, Erlinger TP. Smoking cessation and cardiovascular disease risk factors: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. PLoS Med. 2005;2(6):e160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bijker R, Agyemang C. The influence of early-life conditions on cardiovascular disease later in life among ethnic minority populations: a systematic review. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11(3):341-353. doi: 10.1007/s11739-015-1272-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deen JF, Adams AK, Fretts A, et al. Cardiovascular disease in American Indian and Alaska Native youth: unique risk factors and areas of scholarly need. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(10):e007576. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoover E. “You can’t say you’re sovereign if you can’t feed Yourself”: defining and enacting food sovereignty in American Indian community gardening. Am Indian Cult Res J. 2017;41(3):31-70. doi: 10.17953/aicrj.41.3.hoover [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wright J, Williams R, Wilkinson JR. Health needs assessment: development and importance of health needs assessment. BMJ. 1998;316(7140):1310-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC - Assessment and plans - Community health assessment - STLT gateway. Published April 6, 2019. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/cha/plan.html

- 14. Indian Health Service. Community Health Tools Community Health Assessment. Health promotion/disease prevention. Published n.d. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.ihs.gov/hpdp/communityhealth/

- 15. Shanley KW, Evjen B. Mapping Indigenous Presence: North Scandinavian and North American Perspectives. University of Arizona Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelley A, Belcourt-Dittloff A, Belcourt C, Belcourt G. Research ethics and indigenous communities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2146-2152. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pacheco CM, Daley SM, Brown T, Filippi M, Greiner KA, Daley CM. Moving forward: breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2152-2159. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. English K. CVD, stroke, diabetes, and kidney disease among American Indians in the Southwest. Published online 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kelley A. Public Health Evaluation and the Social Determinants of Health. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arrazola J. COVID-19 mortality among American Indian and Alaska Native persons — 14 states, January–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1853-1856. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hopi Community Needs Assessment. The Hopi Tribe. Published May 21, 2021. Accessed November 10, 2022. https://www.hopi-nsn.gov/hopi-community-needs-assessment/

- 22. O’Connell J, Reid M, Rockell J, Harty K, Perraillon M, Manson S. Patient outcomes associated with utilization of education, case management, and advanced practice pharmacy services by American Indian and Alaska Native peoples with diabetes. Med Care. 2021;59(6):477-486. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Redvers N, Blondin B. Traditional Indigenous medicine in North America: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Adakai M, Sandoval-Rosario M, Xu F, et al. Health disparities among American Indians/Alaska Natives - Arizona, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1314-1318. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6747a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lewis ME, Volpert-Esmond HI, Deen JF, Modde E, Warne D. Stress and cardiometabolic disease risk for indigenous populations throughout the lifespan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):eng1012384551661. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leung E, Parker T, Kelley A, Blankenship JC. Social determinants of incidence, outcomes, and interventions of cardiovascular disease risk factors in American Indians and Alaska Natives. World Med Health Policy. 2022. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kelley A, Small C, Milligan K, Charani Small M. Rising above: COVID-19 impacts to culture-based programming in four American Indian communities. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res J Natl Cent. 2022;29(2):49-62. doi:10.5820/aian.2902.2022.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]