Abstract

Purpose

In the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, already limited services and resources for families of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in China became even more scarce.

This qualitative case study highlights one online parent education and training (PET) program developed during the pandemic to offer home-intervention strategies to parents of children with ASD in mainland China. This exploratory study sought to examine the emic perspectives of the trainers and parents who participated in the 12-week intensive training program while considering the cultural context in China and the transnational, remote nature of the program.

Methods

The primary data focused on the experiences of the trainers and parents within PET program’s structure and strategies, which were adapted from the Training of Trainers model, and were collected from semi-structured, in-depth individual and focus group interviews conducted virtually with trainers (n = 4). Supplemental data sources included training session materials and feedback forms collected from parents (n = 294) at the midpoint and end of the program. After the collected data were sorted and condensed, a thematic analysis was performed using the data analysis spiral to further organize and code the data, and the codes were finally collapsed into themes.

Findings

Three overarching themes were identified: (1) training as modeling with resources, (2) dilemmas in cultural contexts and expectations, and (3) cultivating parent support networks.

Conclusion

The online PET program became a hub of support networks and learning spaces for parents of children with ASD in different regions in China during the pandemic. Through the interactive virtual training sessions, parents were supported by continuous feedback on their home intervention and coached to cultivate support networks among themselves despite tensions arising from cultural differences and to implement effective intervention strategies that were individualized and authenticated to their specific familial needs.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Parent education and training, COVID-19, Home intervention, Training of trainers, Early childhood

What this paper adds?

This study contributes to the literature on parent education and training for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Situated during the COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China, a virtual training program for parents of children with ASD, its structure and processes, and the experiences of the trainers and parents are examined. The study employs qualitative research methods to highlight the emic perspectives of the trainers and parents, while also considering cultural context and the transnational and remote nature of the training program. The findings hold significant implications for future parent education and training models in emergency situations and beyond.

1. Introduction

Appropriate schooling and services are scarce resources for young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their families in mainland China (H.-T. Wang & Casillas, 2012). This is largely due to a lack of adequately trained professionals who are able to provide such education and services, especially in hard-to-reach regions in rural China (Hu & Yang, 2013; Liu et al., 2016; McCabe, 2013; B. Wang, Cao, & Boyland, 2019; D. Zhang & Spencer, 2015). One grassroots approach to ameliorating the situation has been to offer training to parents (Xu et al., 2018), as families continue to shoulder the bulk of the responsibility for educating their children with ASD in the absence of governmental and social support systems (B. Wang et al., 2019). In addition to a lack of appropriate placement in public education for children with ASD, the COVID-19 outbreak in the spring of 2020 exacerbated the need for the already limited services and resources, leaving parents in desperation for intervention training and education but reliant on programs from private service providers (Song, Giannotti, & Reichow, 2013; Y. W. Wang, 2017).

The Dami and Xiaomi Child Development Center is a pioneer service provider of early childhood special education in mainland China. Privately run and located in major cities, such as Shanghai, Guangzhou, Beijing, and Shenzhen, the center provides a variety of educational and therapeutic services, including applied behavior analysis intervention; speech and language, occupational, and physical therapy; and inclusive preschool education, particularly for children with ASD. When the COVID-19 pandemic forced the center to pause all of its service delivery in February 2020, Dami and Xiaomi turned the crisis into an opportunity and organized online parent education and training (PET) programs to train parents to work with their children at home during quarantine. The intent of the programs was to offer appropriate education and training to parents of children with ASD so they could utilize research-based and culturally relevant intervention strategies at home. In addition, the virtual mode aimed to reach parents in various parts of the country beyond the major cities, including rural and remote regions such as Yunnan and Gansu, which were even more deprived of special education services and resources during the national lockdown.

Past research has shown, when implementing parent training and support in culturally diverse contexts, it is important to take into account cultural sensitivity because the challenges that various developmental disabilities present to families can be culture specific (Kong & Au, 2018; Xu et al., 2018). Particularly in the Chinese cultural context, the prevalent exclusion of children with ASD in the public school system and the general population’s narrow understanding of individuals with ASD attribute to the stigma experienced by many families of children with ASD (Bie & Tang, 2014; Liu et al., 2016; McCabe, 2013). Moreover, due to the one-child policy, which led to hyper-expectations for academic and career achievement being placed on individual children, parents of children with ASD tend to experience higher rates of stress and are in need of adequate support (W. Zhang, Yan, Barriball, While, & Liu, 2015). Due to these cultural barriers and inaccurate perceptions of ASD, in China, many parents of children with ASD tend to feel ashamed of themselves (Huang, Jia, & Wheeler, 2013) and consider the education of their children as strictly their responsibility (McCabe & Barnes, 2012).

An emergent body of literature has shown that providing PET via online methods can viably empower parents to effectively implement intervention strategies, especially regarding young children’s communication skills (Meadan et al., 2016; Snodgrass et al., 2017). One of the advantages of online PET is it enables parents and/or caregivers to become more active during intervention sessions, even become the primary facilitators of intervention, in the most naturalistic environments (Meadan & Daczewitz, 2015). Additionally, a review of the literature on PET for children with ASD reports that effective PET programs include not only intervention strategies but also support systems to facilitate the well-being of parents and families (Dawson-Squibb, Davids, Harrison, Molony, & de Vries, 2020). Caring for and educating children with ASD is a lifelong challenge, especially in a cultural context where educational and social welfare systems are not yet established widely (Ji, Sun, Yi, & Tang, 2014; Lu et al., 2018; Song et al., 2013; Xiong et al., 2011). Considering this context and the particular educational emergency caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Dami and Xiaomi designed their PET programs to provide optimal education and training for home intervention. The programs also incorporated the imperative component of social support for parents to decrease stress related to parenting children with ASD.

This qualitative case study explores one of these online PET programs, the Social Stories Parent Education and Training Program, focusing on its structure and delivery of intervention strategies for social-emotional development and communication through a culturally relevant Social Stories curriculum (McDevitt, Jiang, Xu, & Pei, 2020) coupled with a parent support component. This Social Stories curriculum was developed at Dami and Xiaomi in an effort to enact more culturally relevant curricula to support children with ASD at the center. While this curriculum was adapted from the evidence-based program Social Narrative from the United States (Sam & AFIRM Team, 2015), its contents were originally created to meet the cultural and linguistic needs of children and parents in China. The Social Stories curriculum had been used as one of the core curricular at Dami and Xiaomi for about a year, and there have been ongoing efforts to measure its effectiveness.

The current research, therefore, is an exploratory response to the needs of children and parents that quickly became apparent in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following research question was asked: How do the trainers and parents describe the benefits and tensions experienced in the remote Social Stories PET program during the COVID-19 lockdown? Utilizing data from semi-structured interviews with the program’s trainers and feedback forms received from the participating parents, this study examines the experiences of the trainers and trainees within the implemented PET training structure, the tensions and dilemmas negotiated by the trainers and trainees, and the relationships and support networks cultivated as a result of the program. In particular, this study aims to examine the emic perspectives of the trainers and parents while considering the cultural context in mainland China and the transnational and remote nature of the training program, especially since no PET programs for ASD have been conducted on this large and comprehensive a scale outside of the United States (Dawson-Squibb et al., 2020; Meadan & Daczewitz, 2015). It is also worth mentioning that the Social Stories PET program is one of the first PET programs to include multimodality and one of the first to be delivered fully online during a global pandemic. As such, the findings of this study have significant implications for implementation of PET in future emergency situations and beyond.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

A total of 294 parents, mostly mothers of young children (ages 2–7) who were clinically diagnosed with ASD, a neurodevelopmental disorder, participated in the 12-week-long online PET program, which consisted of weekly webinars, small group discussions, and individual feedback sessions. The parents were recruited through the online platform WeChat, where Dami and Xiaomi share blog posts and daily articles containing information about ASD and intervention strategies. Participants were also recruited through free webinars offered by Dami and Xiaomi to help parents in different parts of China, both urban and rural, become familiar with online learning methods and access educational resources. The parents who showed further interest signed up to participate in the intensive online PET program.

The Social Stories PET program employed a pyramidal or cascade training model called Training of Trainers (TOT; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC], 2020), similar to the Train-the-Trainer (TTT) model (Blitz, Edwards, Mash, & Mowle, 2016; Suhrheinrich, 2015). The TOT model has been used in many fields such as medicine (see Maruta, Yao, Ndlovu, & Moyo, 2014), health education (see Chou, Colley, Pearlman, & White, 2014), and other fields of education such as language education (see Benson & Plüddemann, 2010; Vu & Pham, 2014). Research on the TOT model has proven its effectiveness and sustainability, especially for training expansive groups in a relatively short time period. According to the CDC (2020), the TOT model, as one of its Professional Development Best Practices, is premised on master trainers coaching multiple new or inexperienced trainers so they may gain skills or expertise in a specific topic area and become trainers themselves. These intermediate trainers then present information and lead activities for new trainees. The TOT model is practice-intensive, with both trainers and trainees participating in role play as they teach and learn the curriculum content at the same time (Maruta et al., 2014). The master trainer teaches the curriculum content to the intermediate trainers using interactive, learner-centered pedagogy, and they then practice the learned content by teaching it to new trainees and receive feedback from the master trainer.

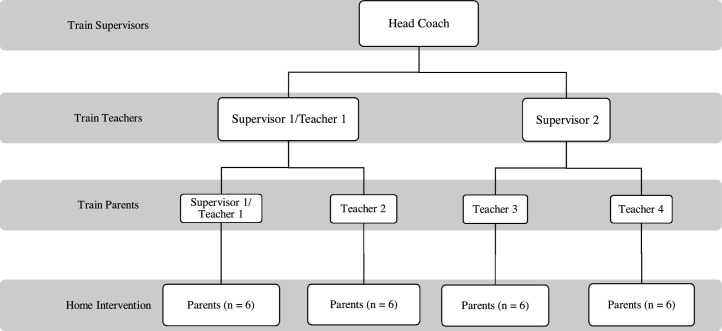

Likewise, most of the training in the Social Stories PET program focused on interactive learning components such as demonstration, discussion, role play, and hands-on practice in addition to the weekly webinars. The structure of the program consisted of three levels of training: (1) the head coach (master trainer) trained 6 supervisors on a weekly basis, starting a few weeks before the program and continuing for its duration; (2) each supervisor trained 8 teachers on a weekly basis, starting a few weeks before the program and continuing for its duration; and (3) each teacher trained a group of 6 parents on a weekly basis for the duration of the program. A few of the supervisors had dual roles as both supervisor and teacher (see Fig. 1 ). It is important to mention that the training was transnational and collaborative as the head coach and a few of the supervisors and teachers resided in the United States while all of the participating parents (trainees) were located in various regions of China.

Fig. 1.

Adapted and Simplified Training of Trainers (TOT) Model Used by the Social Stories PET Program.

The three levels of training occurred systematically and simultaneously, and approaches to training were constantly adjusted based on conversations and feedback from all members at all levels. The head coach, supervisors, and teachers followed the TOT model of leading discussions that reinforce learning, listening effectively to gauge and respond to learners’ needs, providing individualized feedback by observing home-intervention implementation videos, and supporting learners to create support networks. At each level, all participants were trainers and learners simultaneously; the head coach modeled what should happen in each trainer’s own small group of learners, whether they were teachers or parents. The weekly sessions were conducted on DingTalk, a popular, accessible, and free online messaging application. Participants were able to access the weekly webinars, group discussions, feedback sessions, and communications among group members, as well as upload their home intervention videos, using DingTalk on their smartphones, tablets, or computers.

The 12-week program was divided into three segments, each lasting 4 weeks, that covered (a) preparing home environments for at-home intervention, (b) helping children with emotional regulation, and (c) managing challenging behaviors. The first segment focused on supporting parents for at-home intervention. It included strategies for establishing new routines, since previous routines had been disrupted by the lockdown, identifying existing material and familial resources, and building and maintaining strong and positive relationships with children during uncertain times. The second segment focused on helping children with emotional regulation and began by asking parents to express the emotions and trauma they themselves were experiencing during the lockdown and their lived experiences of having children with ASD in their Chinese cultural contexts. Once the parents processed their own emotions and trauma, they learned ways to empathize with their children and help them engage in emotional regulation by identifying and responding to patterns in their emotional displays. The final segment was dedicated to management of challenging behavior, prevention strategies, and ways of building on children’s strengths rather than focusing on problem behaviors.

2.2. Data collection and analysis

Upon receiving IRB approval and consent from Dami and Xiaomi, the head coach, supervisors, teachers, and parents, data collection began in Week 4 of the program. The delay in data collection was due to the spontaneous nature of the online program, which was a response to an urgent need during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the processing time for IRB approval. The primary data sources included semi-structured individual interviews at the midpoint of the program with the head coach and three supervisors who were also teachers of parent groups. At the end of the program, another in-depth individual interview with the head coach and a focus group interview with the supervisors/teachers were conducted. The interviews, which totaled six and lasted 30 min to 2 h each, explored questions around the particulars of their training and how they placed meaning on their learning processes during the pandemic. All interviews were conducted in English and were transcribed verbatim.

Supplemental data from the training materials were collected such as recorded weekly lecture webinars, video-recorded small group discussions with parents, parents’ home-intervention implementation videos, and feedback forms from parents. The feedback form was a short questionnaire distributed at the midpoint and again at the end of the program asking parents about their overall satisfaction, understanding of the content materials, time spent receiving training and completing assignments, utilization of learned intervention strategies and execution at home, and suggestions and recommendations for improving the program. Their responses were organized into Excel and a research assistant fluent in Mandarin translated the feedback and other supplemental data into English.

The collected data were organized and analyzed using the data analysis spiral (Creswell & Poth, 2018). First, the data from the various sources were sorted into the different modes (interview transcripts, videos, documents, and parent feedback). Second, keeping the research aim and question in mind, emerging ideas from the video data and the written and transcribed data were recorded as analytic memos. Then, through a selective process of “data condensation” (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2020, p. 8), the collected data were mainly sifted for trainer interview and parent feedback data. Using open and descriptive coding processes (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016), the interview and feedback data were highlighted and sorted under initial codes, such as “training as modeling,” “cultural differences,” “emotional support,” etc. (see Table 1 ). Finally, a thematic analysis was conducted through an iterative process in which the data were further reduced and coded according to identified patterns (Yin, 2014).

Table 1.

Themes, codes, data sources, and data examples.

| Themes | Codes | Data sources | Data examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training as modeling with resources | Modeling training | Trainer interviews | “This way, I get to see a small picture of their daily life and ask more nuanced questions such as ‘He’s moving his hands but is he really not listening to the story?’ ‘What do you think you need the most help with in order to get him to interact with you?’” |

| Constructive feedback | Parent feedback | “I don't feel confident in teaching my child on my own.” | |

| Individualized resources | “I feel helpless most of the time.” | ||

| “I don't know if I can manage his behaviors while I read to him.” | |||

| “I am not sure how to get him to interact with me.” | |||

| Dilemmas in cultural contexts and expectations | Cultural differences | Trainer interviews | “I would say the biggest challenge was to get the parents to try to take the first step to be bold and to take the first step to try things that they haven’t tried before” |

| Understanding autism | Parent feedback | “[We are] afraid that teachers [in school] or other kids [might] see [our] kids differently. . . and consider them as very strange [if they continue their repetitive behavior].” | |

| Challenging behavior | |||

| Expectations for children | |||

| Cultivating parent support networks | Emotional support | Trainer interviews | “I felt like parents were in distress in this pandemic. The parents needed to feel connected and supported.” |

| Self-care strategies | Parent feedback | “I love the course contents. I love the teacher. In this program, I got to feel that the teachers are genuine and that they are really caring, that they’re really thinking for us and helping us. So, I really appreciate that.” | |

| Parents support |

3. Findings

The COVID-19 crisis had changed the participants’ lives entirely with many unforeseen challenges; yet, new and innovative opportunities through the PET program have brought people together from near and far. Thus, emic perspectives were examined to illustrate the structure and the processes of the implemented program, with a focus on the experiences of the individuals involved in the training and the relationships built among them throughout the course. The thematic analysis produced three themes: (1) training as modeling with resources, (2) dilemmas in cultural contexts and expectations, and (3) cultivating parent support networks. The first theme illustrates the program’s training structure and the ways in which the trainers modeled how to individualize resources to provide constructive feedback on intervention strategies. The second theme reveals the tensions and dilemmas that arose from the differing cultural contexts and expectations of teachers and parents due to the transnational nature of the training team. The final theme describes the support networks that were cultivated by the trainers and parents to withstand the challenges they faced in quarantine and from raising children with ASD in the Chinese mainland context. The findings below detail the three themes, highlighting the narratives of the trainers and parents on how they confronted challenges, celebrated successes, and supported each other in the virtual training spaces.

3.1. Training as modeling with resources

Aligned with TOT structure, the Social Stories PET training was modeled for each group, whether it was at the level of supervisor, teacher, or parent. Because of the interactive nature of the program, one of the most essential aspects of modeling was showing how to provide constructive, individualized feedback. However, this was also one of the most challenging parts of the training for many teachers. For example, each teacher was instructed to hold individual and weekly feedback sessions after parents submitted home-intervention implementation videos demonstrating their execution of the learned strategies with their children. While discussing the videos with the parents, teachers were to provide individualized feedback on the successes and challenges experienced by the parents and what they could do to improve their intervention skills. Many teachers were new to training parents and expressed difficulty in speaking to them virtually in supportive and generative ways.

In response, Hui, the head coach, focused on modeling this practice from early on in the supervisor- and teacher-training sessions. She demonstrated how to provide individualized and constructive feedback by using teachers’ weekly videos of their small group or individualized feedback sessions as resources. She firmly believed that it was important to create an experience that mimicked the trainees’ experience, so that the trainers could be trained in the same way they were to train the parents. Parents often brought concerns to their feedback sessions such as, “I don't feel confident in teaching my child on my own,” “I feel helpless most of the time,” “I don't know if I can manage his behaviors while I read to him,” “I am not sure how to get him to interact with me,” and so on. Following Hui’s lead, Sue (pseudonym), who held a dual role as a supervisor and teacher, would tell parents she would watch their home-intervention implementation videos and examine their interactions with their child. She explained,

This way, I get to see a small picture of their daily life and ask more nuanced questions, such as, “He’s moving his hands but is he really not listening to the story?” “What do you think you need the most help with in order to get him to interact with you?”

By emulating Hui’s modeling, Sue was able to ask questions that resulted in conversations and problem-solving that were contextualized in the parents’ home environments and “based on their capabilities and what they could do.” Sue mentioned that, just as she was empowered by Hui’s modeling, she wanted to empower the parents in her group to “see and accept their strengths.” Ling (pseudonym), also a supervisor and teacher, added,

I learned how to talk to the teachers and parents in my group and to really think about how my suggestions would actually support them. It was important that I say certain things in ways that matched each parent’s situation and their own progress with home intervention.

Illuminated in the words of the head coach, supervisors/teachers, and parents was that they were often resources in themselves and feedback could be individualized according to their own progress and home environments. Modeling best practices to empower and encourage trainees promoted a ripple effect among the team of trainers, ultimately benefiting the children through home intervention. However, tensions inevitably arose, particularly between teachers and parents, due to cultural clashes and differing expectations. The second theme describes these contextual dilemmas and how participants negotiated expectations.

3.2. Dilemmas in cultural contexts and expectations

The training efforts documented in this study were transnational. The head coach and some of the supervisors and teachers were in the United States and the rest of the teachers and the parents were in mainland China. Although they all spoke Mandarin, their cultural and familial contexts varied. The parents lived in a social and cultural context in which stigma is attached to ASD, called “alone syndrome” in Chinese (B. Wang et al., 2019, p. 138), and where there is a lack of disability awareness among the general population (Bie & Tang, 2014; H.-T. Wang & Casillas, 2012). Meanwhile, the trainers in the United States lived in a different social and cultural context, where ASD is widely known and is considered a part of neurodiversity and personal identity.

While the trainers in the United States had immigrated from China and possessed a cultural understanding of the parents’ lived experiences, there seemed to be distinctive differences in their views toward certain characteristics of ASD and expectations for the children. For example, during individual feedback or group discussion sessions on managing challenging behavior, the trainers tried to shift the parents’ perspectives on their children’s behavior by normalizing some of their repetitive behaviors. However, parents had opposing ideas and responded, “[We are] afraid that teachers [in school] or other kids [might] see [our] kids differently. . . and consider them as very strange [if they continue their repetitive behavior].” According to Mai-Lin (pseudonym), a supervisor and teacher, the parents in her group wanted to learn practical strategies to change their children’s behavior so they could be “fixed” and “fit in society.” This social pressure and structural barrier in the parents’ cultural context often created a dilemma during the training.

Many of the parents in the program were also coming to terms with their children’s diagnosis, trying to understand what ASD was and how it manifested in their children. One parent shared his negative perspectives toward his own child, stating, “My child is never going to catch up. He’s the worst of all the children I’ve seen.” Some of these comments seemed to be coming from the stigma experienced in school settings. A mother mentioned, “My child’s teacher doesn’t have high expectations for him because of his special needs. So, if he misbehaved, the teacher would just let it go, because she thinks he’s the child with special needs and it’s pointless to correct him.” Sue added that many parents in her group believed it was their fault their children had ASD and saw their children with “a very deficit view” based on many negative experiences in their own community involving their children.

Recognizing the deficit views and low expectations of children with ASD in the parents and the cultural context in mainland China, the trainers sought opportunities to shift parents’ attitudes and perspectives during their group discussions. Sue stated, “I would say the biggest challenge was to get the parents to try to take the first step to be bold and to take the first step to try things that they haven’t tried before.” By working through tensions and having difficult discussions with the parents, the teachers came to understand the complex, layered experiences that shaped the parents’ beliefs about their children and their disabilities, and that they required much deeper intervention. The last theme below articulates the ways in which the trainers delved deeper into supporting parents socially and emotionally and helping them establish support networks.

3.3. Cultivating parent support networks

Considering the parents’ accumulated lived realities and the many stressors of quarantine life, the trainers prioritized the social-emotional well-being of the parents and intentionally created spaces that allowed them to share their traumas and experiences. Hui discussed what she considered was the primary purpose of the program:

During the pandemic, a lot of parents came to us to ask questions, but they actually came to us for comfort. . . We wanted to support them and make sure they do self-care, make sure they have resources, make sure they know where to seek help, make sure they encourage themselves, and have motivation.

Hui was aware of the difficulty the parents might be having, at home with their children in small housing spaces, with little resources and no support systems in place for emergency situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. During one of her first weekly lectures, Hui told the frustrated parents to “forgive [their] mistakes, forgive [themselves], forgive [their] children, and forgive other people who had the wrong idea of autism.” Hui understood the role of the training program was to support parents in dealing with their own emotions during the crisis before teaching any intervention strategies.

Following the lead of the head coach, the trainers established what they called, “the check-in ritual” during which they asked their group members how they were doing and what they were feeling as they began training each week. The check-in ritual was implemented within the teacher groups by their supervisors and within the parent groups by the teachers during the group discussion sessions before discussing any intervention strategies. The check-ins prompted teachers to first tune into what parents had to say, what they were struggling with, and the kinds of resources they needed. They also prompted the creation of support networks within parent groups as they began to trust the teachers and each other, and as they began to more openly discuss their current lives and their empathy toward each other.

Beyond the check-in rituals, their weekly discussions also became a space where parents formed relationships, harnessing a community of hope among themselves. Sometimes, these chats, designed to be 30 min long, lasted 90 min because of the level of engagement among the parents. One parent provided feedback regarding the group discussions: “I know it’s very hard for us because our children are different from typical children. But it just takes time, and requires patience.” Ling referred to a conversation that took place during a group session with parents and said, “We were talking about how to switch our attitudes. . . They were really supporting each other and building on each other’s comments.” In this space where they could honestly share the ups and downs of their daily experiences caring for their children at home during the pandemic, parents began to acknowledge their own emotions attached to raising children with ASD and reflect on their intervention skills. Sometimes, these conversations went on without much facilitation from the teacher.

The cultivation of support networks also empowered parents to implement the learned intervention strategies more effectively. Mai-Lin explained during a parent group session that they were focusing on children’s books related to social-emotional development to help parents “understand how to manage their children’s emotion, and how to manage their own emotions.” One of the parents who participated in the discussion shared, “Well, I never thought about it that way. I can actually use this strategy to express myself, and I can have a conversation with my kid about my own feelings, and then teach him how to express himself.” Within such a learning community, the parents were encouraged to care for their own emotional well-being and to apply the learned practice with their children in their own contexts.

According to both trainer interviews and parent feedback forms, the cultivation of a support system for the parents through the check-in ritual and small group discussions was the most successful aspect of the PET program. Hui echoed the responses: “I felt like parents were in distress in this pandemic. The parents needed to feel connected and supported.” Validating their humanity and having their voices heard among their group members was the reason she had made a social-emotional support system the focal point of the PET program. Supported and comforted by their teachers and group members throughout the program, parents were able to recognize their own strengths as well as vulnerabilities during the lockdown. They began to identify authentic ways to nurture their children’s social-emotional development and communication skills by individualizing the intervention strategies. Parents attributed their gains in this program to their teachers, stating, “I love the course contents. I love the teacher. In this program, I got to feel that the teachers are genuine and that they are really caring, that they’re really thinking about us and helping us. So, I really appreciate that.” Sue responded to the feedback, highlighting the reciprocity in the relationships, “We gave our best, we gave our whole heart.”

4. Discussion

The Social Stories PET program was anchored in the principles of honoring parents as capable members and prioritizing their humanity and well-being while equipping them with resources and intervention strategies focused on developing social-emotional and communication skills in their young children with ASD. Facilitation of training was made possible by a thoughtfully designed structure aligned with the TOT model and timely workshops with intervention strategies and resources that responded to educational needs exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings highlighted how parents urgently sought resources and support networks during the national lockdown and withstood the crisis together with other parents by sharing their lived experiences of educating and caring for their children with ASD in their cultural context.

Previous research found that conducting online PET has the benefit of empowering parents to implement home intervention in naturalistic environments (Meadan et al., 2016; Snodgrass et al., 2017). The current study demonstrated more specifically how providing virtual, individualized feedback to parents as part of an online PET program plays a critical role in empowering parents to actively engage in conversations about their intervention strategies (Jayaraman, Marvin, Knoche, & Bainter, 2015). Following the TOT model and the head coach, the teachers trained the parents using generative feedback, which offered parents opportunities to reflect on and rethink their children’s abilities and disabilities. The ongoing individual feedback sessions also provided a space for parents to examine their own relationships with their children and understand more deeply how ASD is manifested in them uniquely. As the trainers positioned themselves as equal partners in their conversations with the parents, they found resources within themselves by carefully listening to each other and engaging in problem-solving together when challenges arose. This exchange between the trainers and parents laid a foundation for building and sustaining authentic relationships and, ultimately, improving their practices and skills (Fox, Hemmeter, Snyder, Binder, & Clarke, 2011).

Tensions still arose during the program due to transnational differences between the trainers and parents as well as elevated levels of stress and frustration. A recent study on the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on caregivers of children with disabilities documented high levels of stress and anxiety (Dhiman et al., 2020). Parallel to this these findings, the parents who participated in the Social Stories PET program showed the increased levels of stress and required deeper intervention for their mental health. The establishment of the check-in ritual and group discussions created a site of comfort and community where parents came to share their experiences in the lockdown as well as their accumulated lived realities and hardships as parents of children with ASD in mainland China (Huang et al., 2013, H. Wang, Hu, & Han, 2020, W. Zhang et al., 2015). During global emergency contexts such as the COVID-19 crisis, as Sahlberg (2020) noted, learning should first focus on relationships, social-emotional development, and individual well-being. The trainers prioritized the personal well-being of the trainees, especially through their discussion sessions, and cultivated intimate support systems among the parents. The unique supportive networks facilitated by the group teachers demonstrated collaborative and authentic partnerships within a community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and seemed to have encouraged the parents to motivate each other to provide more effective home intervention for their children (Baker & Sanders, 2017; Dawson-Squibb et al., 2020). Ultimately, these networks seemed to have enabled a shift in the parents’ mindsets towards their children and their disability, from deficit-based perspectives to strength-based orientations (Kemp & Turnbull, 2014).

Lastly, affirmed by existing literature on remote intervention (Vismara, McCormick, Young, Nadhan, & Monlux, 2013; Wainer, Pickard, & Ingersoll, 2017), one of the most powerful benefits of the Social Stories PET program and its virtual delivery, as opposed to in-person training, was the ability to reach many more parents in various parts of the country. In China, although still limited, the majority of resources regarding autism intervention and services are located in large cities (Hu & Yang, 2013; McCabe, 2008). For example, despite its rapid expansion, the Dami and Xiaomi Child Development Center is located in only about ten major cities in China. By promptly responding to the educational emergency brought on by COVID-19, Dami and Xiaomi’s launch of the online PET program opened a new opportunity for them to reach parents residing in under-resourced and hard-to-reach areas, such as rural regions in China. Reaching more people also meant expanding parent support networks, which have enabled parents to share resources for children with ASD around the nation.

5. Limitations and future directions

Drawing from the perspectives of the trainers, including the head coach, supervisors, and teachers, and the parents who participated in the Social Stories PET program, the present study provides a window into the struggles and passion of parents who have children with ASD in China. Although the trainers’ narratives were supported by parent feedback and training materials, the main data did not include in-depth interviews of the parents. Future research can directly inquire into the perspectives of parents and children with ASD to understand their experiences of navigating disability and the social and educational landscape in China (Song et al., 2013; B. Wang et al., 2019) in the post−COVID era.

Implications for future practice include the need to develop more teachers who are adequately trained to engage with children with ASD and their parents and to create culturally relevant instructional materials. In China, it is not uncommon for these children and their parents to have teachers who are inexperienced in interventions for ASD or lack formal education in special education (McCabe, 2008). Although the teachers in the current study showed rapid acquisition of intervention skills, many were not formally trained in teaching young children with ASD or working with parents. Experts on emergency education have stated that schools and educational programs must be prepared for possible future crises similar to the COVID-19 pandemic (Moriarty, 2020). Having more trained professionals can reduce coaching intensity and allow online training programs to expand more readily to reach more children and parents with fidelity, especially during educational emergencies. Transnational collaboration can also benefit training efforts as shown in this case study.

6. Conclusion

The COVID-19 global pandemic forced an unprecedented upheaval of the lives of families, especially those with children with developmental disabilities in mainland China, where already limited resources are unequally distributed. A team of trainers at Dami and Xiaomi made a rapid decision to respond to this pivotal moment by offering online PET programs to provide support for parents of children with ASD in different regions in China. As illustrated in this case study, a transnational team of trainers came together under pressing circumstances and imagined new educational opportunities and possibilities and designed an online PET program to make a difference in these families’ lives. There were tensions between the trainers and parents due to their cultural and contextual differences and the complex lived experiences parents brought with them to their learning. However, over the weeks-long training period, the parents cultivated support networks among themselves, facilitated by the trainers, to withstand the challenges they faced during the crisis. These support systems became a cornerstone of effective implementation of intervention strategies that were individualized and authenticated according to specific familial needs.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the Dami and Xiaomi Child Development Center for their support in providing access to their service program and their generous funding to undertake this research. Many thanks also to the trainers and parents who participated in the study and shared their experiences and time, and to Siqi Cheng for her help with data translation and preliminary analysis.

References

- Baker S., Sanders M.R. Predictors of program use and child and parent outcomes of a brief online parenting intervention. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2017;48:807–817. doi: 10.1007/s10578-016-0706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson C., Plüddemann P. Empowerment of bilingual education professionals: The training of trainers programme for educators in multilingual settings in southern Africa (ToTSA) 2002–2005. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2010;13(3):371–394. [Google Scholar]

- Bie B., Tang L. Representation of autism in leader newspapers in China: A content analysis. Health Communication. 2014;30(9):884–893. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.889063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz J., Edwards J., Mash B., Mowle S. Training the trainers: Beyond providing a well-received course. Education for Primary Care. 2016;27(5):375–379. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2016.1220237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Understanding the training of trainers model.https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/tths/train_trainers_model.htm August. [Google Scholar]

- Chou C., Colley L., Pearlman R.E., White M.K. Enhancing patient experience by training local trainers in fundamental communication skills. Patient Experience Journal. 2014;1(2):36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W., Poth C.N. 4th ed. Sage; 2018. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Squibb J.-J., Davids E.L., Harrison A.J., Molony M.A., de Vries P.J. Parent education and training for autism spectrum disorder: Scoping the evidence. Autism. 2020;24(1):7–25. doi: 10.1177/1362361319841739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhiman S., Sahu P.K., Reed W.R., Ganesh G.S., Goyal R.K., Jain S. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on mental health and perceived strain among caregivers tending children with special needs. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox L., Hemmeter M., Snyder P., Binder D., Clarke S. Coaching early childhood special educators to implement a comprehensive model for promoting young children’s social-emotional competence. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2011;31(3):178–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Yang X. Early intervention practices in China: Present situation and future directions. Infants and Young Children. 2013;26(1):4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huang A.X., Jia M., Wheeler J.J. Children with autism in the People’s Republic of China: Diagnosis, legal issues, and educational services. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(9):1991–2001. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1722-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman G., Marvin C., Knoche L., Bainter S. Coaching conversations in early childhood programs: The contributions of coach and coachee. Infants and Young Children. 2015;28(4):323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ji B., Sun M., Yi R., Tang S. Multidisciplinary parent education for caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2014;28(5):319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp P., Turnbull A.P. Coaching with parents in early intervention: An interdisciplinary research synthesis. Infants and Young Children. 2014;27(4):305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kong M.M., Au T.K. The incredible years parent program for Chinese preschoolers with developmental disabilities. Early Education and Development. 2018;29(4):494–514. [Google Scholar]

- Lave J., Wenger E. Cambridge University Press; 1991. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Li J., Zheng Q., Zaroff C.M., Hall B.J., Li X., et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of autism spectrum disorder in a stratified sampling of preschool teachers in China. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0845-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M.-H., Wang G.-H., Lei H., Shi M.-L., Zhu R., Jiang F. Social support as mediator and moderator of the relationship between parenting stress and life satisfaction among the Chinese parents of children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(4):1181–1188. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3448-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruta T., Yao K., Ndlovu N., Moyo S. Training-of-trainers: A strategy to build country capacity for SLMTA expansion and sustainability. African Journal of Laboratory Medicine. 2014;3(2) doi: 10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.196. Art. 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe H. Effective teacher training at the autism institute in the People’s Republic of China. Teacher Education and Special Education. 2008;31(2):103–117. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe H. Bamboo shoots after the rain: Development and challenges of autism intervention in China. Autism. 2013;17(5):510–526. doi: 10.1177/1362361312436849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe H., Barnes R.E. Autism in a family in China: An investigation and ethical consideration of sibling issues. International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education. 2012;59(2):197–207. [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt S., Jiang H., Xu Y., Pei D. Culturally relevant special education curriculum for children with autism in China. Childhood Education. 2020;96(3):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Meadan H., Daczewitz M.E. Internet-based intervention training for parents of young children with disabilities: A promising service-delivery model. Early Child Development and Care. 2015;185(1):155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Meadan H., Snodgrass M.R., Meyer L.E., Fisher K.W., Chung M.Y., Halle J.W. Internet-based parent-implemented intervention for young children with autism: A pilot study. Journal of Early Intervention. 2016;38(1):3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam S.B., Tisdell E.J. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; 2016. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. [Google Scholar]

- Miles M.B., Huberman A.M., Saldaña J. 4th ed. SAGE; 2020. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty K. Collective impacts on global education emergency: The power of network response. Prospects. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09483-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlberg P. Shanker Institute; 2020. Five things not to do when schools re-open.https://www.shankerinstitute.org/blog/five-things-not-do-when-schools-re-open June 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sam A., AFIRM Team . National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder, FPG Child Development Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2015. Social narratives.http://afirm.fpg.unc.edu/social-narratives [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass M.R., Chung M.Y., Biller M.F., Appel K.E., Meadan H., Halle J.W. Telepractice in speech–Language therapy: The use of online technologies for parent training and coaching. Communication Disorders Quarterly. 2017;38(4):242–254. [Google Scholar]

- Song Z., Giannotti T., Reichow B. Resources and services for children with autism spectrum disorders and their families in China. Infants and Young Children. 2013;26(3):204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Suhrheinrich J. A sustainable model for training teachers to use pivotal response training. Autism. 2015;19(6):713–723. doi: 10.1177/1362361314552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vismara L.A., McCormick C., Young G.S., Nadhan A., Monlux K. Preliminary findings of a telehealth approach to parent training in autism. Journal of Autism and Development Disorder. 2013;43(12):2953–2969. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1841-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu M.T., Pham T.T. Training of trainers for primary English teachers in Viet Nam: Stakeholder evaluation. The Journal of Asia TEFL. 2014;11(4):89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wainer A.L., Pickard K., Ingersoll B.R. Using web-based instruction, brief workshops, and remote consultation to teach community-based providers a parent-mediated intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2017;26:1592–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.W. Sixth Tone; 2017. China’s autism schools a last resort for youth on the spectrum.https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1000161/chinas-autism-schools-a-last-resort-for-youth-on-the-spectrum May 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.-T., Casillas N. Asian American parents’ experiences of raising children with autism: Multicultural family perspective. Journal of Asian and African Studies. 2012;48(5):594–606. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Cao F.T., Boyland J.T. Addressing autism spectrum disorders in China. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2019;163:137–162. doi: 10.1002/cad.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Hu X., Han Z.R. Parental stress, involvement, and family quality of life in mothers and father of children with autism spectrum disorder in mainland China: A dyadic analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong N., Yang L., Yu Y., Hou J., Li J., Li Y., et al. Investigation of raising burden of children with autism, physical disability and mental disability in China. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(1):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Yang J., Yao J., Chen J., Zhuang X., Wang W., et al. A pilot study of a culturally adapted early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders in China. Journal of Early Intervention. 2018;40(1):52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yin R.K. Sage; 2014. Case study research: Design and methods. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Spencer V.G. Addressing the needs of students with autism and other disabilities in China: Perspectives from the field. International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education. 2015;62(2):168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Yan T.T., Barriball K.L., While A.E., Liu X.H. Post-traumatic growth in mothers of children with autism: A phenomenological study. Autism. 2015;19(1):29–37. doi: 10.1177/1362361313509732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]