Abstract

Background

Adults with disabilities are at increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe disease; whether adults with disabilities are at an increased risk for ongoing symptoms after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection is unknown.

Objectives

To estimate the frequency and duration of long-term symptoms (>4 weeks) and health care utilization among adults with and without disabilities who self-report positive or negative SARS-CoV-2 test results.

Methods

Data from a nationwide survey of 4510 U.S. adults administered from September 24, 2021–October 7, 2021, were analyzed for 3251 (79%) participants who self-reported disability status, symptom(s), and SARS-CoV-2 test results (a positive test or only negative tests). Multivariable models were used to estimate the odds of having ≥1 COVID-19–like symptom(s) lasting >4 weeks by test result and disability status, weighted and adjusted for socio-demographics.

Results

Respondents who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 had higher odds of reporting ≥1 long-term symptom (with disability: aOR = 4.50 [95% CI: 2.37, 8.54] and without disability: aOR = 9.88 [95% CI: 7.13, 13.71]) compared to respondents testing negative. Among respondents who tested positive, those with disabilities were not significantly more likely to experience long-term symptoms compared to respondents without disabilities (aOR = 1.65 [95% CI: 0.78, 3.50]). Health care utilization for reported symptoms was higher among respondents with disabilities who tested positive (40%) than among respondents without disabilities who tested positive (18%).

Conclusions

Ongoing symptoms among adults with and without disabilities who also test positive for SARS-CoV-2 are common; however, the frequency of health care utilization for ongoing symptoms is two-fold among adults with disabilities.

Keywords: COVID-19, Disabilities, Post-COVID conditions, Long COVID, Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Infection with the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is associated with a wide range of acute and long-term symptoms and conditions. Long-term symptoms experienced 4 or more weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection are collectively called post-COVID conditions (PCC)1 (also known as long COVID or post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC)) and can include activity-limiting symptoms associated with long-term disability.2 Adults with disabilities, defined as serious difficulties with vision, hearing, mobility, cognition, self-care, or independent living, have a higher prevalence of underlying chronic health conditions than adults without disabilities. They are also at higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 illness than adults without disabilities3 , 4 and may have increased occurrence of PCC.

The estimated 61 million adults in the United States with disabilities5 who experienced challenges to accessing health care and social services before the pandemic6 remain medically underserved during the pandemic.7 They report disparities in access to health care, testing, and vaccines,8 among other psychosocial stressors,9 and may require additional resources, technical assistance, and disability accommodations if they develop PCC. Many long-term symptoms reported by people with disabilities, such as fatigue or shortness of breath, are similar to those reported from PCC, but distinguishing symptoms resulting from underlying disabilities from PCC symptoms is important.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Understanding the prevalence and duration of PCC in people with disabilities can help clinicians and public health practitioners identify long-term symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and treat them more effectively.

We analyzed cross-sectional survey data collected by Porter Novelli (PN) Public Services15 to 1) estimate the frequency of PCC and health care utilization among adults with and without disabilities after self-report of SARS-CoV-2 testing, and 2) identify whether PCC were more common among adults with disabilities who self-reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Methods

Survey design and study sample

We performed analyses using cross-sectional survey data collected by Porter Novelli (PN) Public Services15 in PN FallStyles 2021, a nationwide survey of U.S. adults administered from September 24, 2021–October 7, 2021. PN FallStyles participants were chosen from a sample of 4510 panel members aged 18 years or older who also answered an earlier survey of panelists in March–April 2021, called PN SpringStyles 2021. The survey was conducted by the market research firm Ipsos via their KnowledgePanel©, a continuously replenished panel consisting of approximately 60,000 panelists representative of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population.16 Panel members were randomly recruited by mail using probability-based sampling by address to reach respondents regardless of whether they have landline phones or Internet access. If needed, households were provided with a laptop or tablet and access to the Internet. Respondents received cash-equivalent reward points for their participation. Respondents could refuse to answer questions or leave the survey or panel at any time. We analyzed complete responses (which included answers for at least half of the questions in the survey) with self-reported socio-demographic information, underlying chronic conditions, disability status, SARS-CoV-2 test history, symptom(s), vaccination status, and health care utilization. Statistical weighting was used to align the sample with the noninstitutionalized U.S. population distributions, accounting for gender, age, household income, race/ethnicity, household size, education, census region, and metropolitan status (i.e., urban/rural differences). For this analysis, we used the recommended weights provided by Porter Novelli Public Services. For data currency, we used the most recent weighting from U.S. Census’ American Community Survey (ACS) data.17 Weights were designed to match the ACS proportions for these variables.17 For precision, we supplemented these data with metropolitan status, which is not available from the one-year ACS and was obtained from the Current Population Survey (CPS) March 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC).18

Variable definitions

Socio-demographics

Participants reported their age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, highest level of education completed, employment status, household income in 2021, and U.S. Census region.

Pre-existing conditions

Respondents self-reported health conditions they experienced currently, in the past year, or reported no health problems. They self-reported symptoms since January 2020 separately. (See “Symptoms.”)

Disability status

Respondents answered a series of questions asking whether or not they had serious difficulty with vision, hearing, mobility, cognition, self-care, or independent living, according to the six-item set often referred to as the American Community Survey – 6 (ACS-6).19 , 20 Respondents who answered ‘yes’ to at least one question were categorized as having a disability. Those who answered ‘no’ to all questions were categorized as not having a disability.

SARS-CoV-2 test history

Respondents self-reported ever having received a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result (“reported a positive test”), always receiving a negative SARS-CoV-2 test result (“reported only negative tests”), or never having been tested for SARS-CoV-2 (“never been tested”). Respondents who reported having received a positive or negative test result were included in the analysis.

Symptoms

Respondents who reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 test were asked if they experienced ≥1 of 17 symptoms following their first positive test that lasted >4 weeks since they first experienced the symptom(s).21 (See Appendix A.) PCC was defined as having one or more of these symptoms. Respondents who reported only negative tests were also asked to report whether they experienced any of the same symptoms for >4 weeks since January 2020. Respondents reported the duration of symptoms as lasting one to three months; three to six months; six to nine months; nine to twelve months; and twelve months or more. Throughout the results section, we use “long-term symptoms” to refer to respondents who reported these symptoms for >4 weeks, versus other underlying symptoms.

Vaccination status

Respondents were asked about receipt of ≥1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Responses were categorized as fully vaccinated (reported receiving one dose of Johnson & Johnson or two or more doses of Pfizer or Moderna, and considered fully vaccinated ≥2 weeks after receipt of that series); partially vaccinated (reported receiving only one dose of Pfizer or Moderna); and unvaccinated (reported not having received any doses of a COVID-19 vaccine).22 The survey was conducted prior to the recommendations of boosters.23 We define up-to-date vaccination as up-to-date during the survey time period (see Appendix A).24

Health care utilization

A smaller number of respondents self-reported their health care utilization related to long-term symptoms that lasted longer than 4 weeks since they first experienced the symptoms: seeing a doctor, nurse, or other health professional once or more than once; going to urgent or emergency care; hospitalization; or “none of these.”

Statistical analyses

We used chi-squared tests to examine differences in the frequency of demographics, underlying conditions, and long-term symptoms among participants by disability status or SARS-CoV-2 test status. Using multivariable logistic regression analyses, we estimated the odds of having ≥1 COVID-like symptom lasting >4 weeks following a positive SARS-CoV-2 test and their duration: 1) among individuals who reported testing positive for SARS-CoV-2, comparing adults with and without disabilities; 2) among adults with disabilities, comparing those with a positive test to those with a negative test; and 3) among adults without disabilities, comparing those with a positive test to those with a negative test. We described symptom clusters observed >4 weeks after infection in these respondents that were associated with not returning to pre-COVID physical and mental health in another survey of U.S. adults from this time period (see Appendix B).25 (Certain analyses did not compare respondents with and without disabilities due to small sample size of subgroups.) All odds ratios in the multivariable logistic regression model were adjusted for categorical age, sex, race/ethnicity, highest level of education completed, employment status, and U.S. census region. All analyses accounted for sampling weights and were completed in STATA 17. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Human subjects protection

This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. (See e.g., 45 C.F R. part 46, 21 C.F R. part 56; 42 U S C. §241(d); 5 U S C. §551a; 44 U S C. §3501 et seq.) We performed secondary data analysis on de-identified survey responses. Survey responses were confidential. Participants’ personally identifiable information was protected. The survey was conducted by Ipsos via their KnowledgePanel©,16 which maintains a confidentiality agreement with participants to protect their personally identifiable information and does not require a survey-specific consent for KnowledgePanel members who agreed to join the panel and receive survey invitations. Participation was voluntary.

Results

Analytic sample

PN FallStyles 2021 invited 4510 noninstitutionalized U.S. adults aged ≥18 years to participate; 3584 adults responded (79% response rate). Among these respondents, 31 who did not complete the survey or who completed the survey in 10 min or less (indicating incomplete responses) were excluded. Respondents with unknown disability status (n = 36) were also excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 3517 respondents, 3251 (92%) reported being tested for SARS-CoV-2 and disability status. Thus, 3251 respondents were included in our analyses.

Characteristics of respondents

Among the 3251 total respondents in the analytic sample, there were 653 (20%) respondents with disabilities and 2598 (80%) respondents without disabilities (Table 1 ). Overall, 63% of respondents were non-Hispanic White. Respondents with disabilities were generally older, not working, not married, and had lower educational attainment and household income than adults without disabilities (p < 0.001). A greater proportion of respondents with disabilities had ≥1 chronic condition (95%) than respondents without disabilities (66%) (Table 1). Among respondents with disabilities, the most commonly reported conditions were anxiety (48%), depression (41%), and high blood pressure (41%). The most common conditions among respondents without disabilities were seasonal allergies (22%) and high blood pressure (22%). Seventy-two percent (72%) of respondents with disabilities were fully vaccinated, versus 79% of respondents without disabilities (p < 0.004) (Table 1). Among the 653 respondents with disabilities, 82 (13%) reported a positive test, and 571 (87%) reported only negative tests. Among the 2598 respondents without disabilities, 302 (12%) reported a positive test and 2296 (88%) reported only negative tests (Supplemental Table).

Table 1.

Comparison of the frequencies of demographics and other characteristics among survey participants with and without disabilitiesa (N = 3251).

| With disabilitiesb (N = 653) unweighted n (weighted %) | Without disabilities (N = 2598) unweighted n (weighted %) | p-valueg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups, years | |||

| 18–29 | 104 (16) | 547 (21) | <0.001 |

| 30–39 | 89 (14) | 444 (17) | |

| 40–49 | 83 (13) | 419 (16) | |

| 50–59 | 118 (18) | 472 (18) | |

| 60–69 | 117 (18) | 414 (16) | |

| ≥70 | 142 (22) | 302 (12) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 310 (47) | 1250 (48) | 0.816 |

| Female | 343 (53) | 1348 (52) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 427 (65) | 1610 (62) | 0.179 |

| Black or African American, non-Hispanic | 80 (12) | 298 (11) | |

| Other, non-Hispanicc | 41 (6) | 254 (10) | |

| Hispanic | 105 (16) | 436 (17) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 306 (47) | 1533 (59) | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 33 (5) | 78 (3) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 119 (18) | 217 (8) | |

| Never married | 195 (30) | 770 (30) | |

| Highestlevel of education completed | |||

| Some high school or less | 138 (21) | 211 (8) | <0.001 |

| High school graduate/some college | 398 (61) | 1479 (57) | |

| 4-year college/some postgraduate education | 73 (11) | 512 (20) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 44 (7) | 396 (15) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed full-time | 153 (23) | 1309 (50) | <0.001 |

| Employed part-time | 75 (24) | 368 (14) | |

| Not working | 424 (65) | 921 (35) | |

| Household income 2021, USD | |||

| <25,000 | 180 (28) | 231 (9) | <0.001 |

| 25,000–49,999 | 153 (24) | 407 (16) | |

| 50,000–74,999 | 107 (16) | 449 (17) | |

| 75,000–99,999 | 73 (11) | 391 (15) | |

| 100,000–149,999 | 69 (11) | 540 (21) | |

| ≥150,000 | 71 (11) | 580 (22) | |

| U.S. Census Regiond | |||

| Northeast | 111 (17) | 471 (18) | 0.176 |

| Midwest | 139 (21) | 512 (20) | |

| South | 266 (41) | 962 (37) | |

| West | 137 (21) | 653 (25) | |

| Pastyear or current self-reported health conditions | |||

| One or more health conditions | 619 (95) | 1711 (66) | |

| --Anxiety | 312 (48) | 484 (19) | <0.001 |

| --Arthritis | 236 (36) | 284 (11) | <0.001 |

| --Asthma | 78 (12) | 155 (6) | <0.001 |

| --Chronic Pain | 250 (38) | 193 (7) | <0.001 |

| --Depression | 267 (41) | 285 (11) | <0.001 |

| --Diabetes | 141 (22) | 221 (9) | <0.001 |

| --Emphysema/COPD | 41 (6) | 26 (1) | <0.001 |

| --Flu | 23 (4) | 19 (1) | <0.001 |

| --High cholesterol | 212 (32) | 425 (16) | <0.001 |

| --Migraine headaches | 115 (18) | 213 (8) | <0.001 |

| --Seasonal allergies | 212 (32) | 576 (22) | <0.001 |

| --High blood pressure | 270 (41) | 570 (22) | <0.001 |

| --Heart condition (atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, angina, heart attack or other heart condition) | 53 (8) | 70 (3) | <0.001 |

| --Stroke | 13 (2) | 5 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| --Cancer (including skin cancer) | 46 (7) | 76 (3) | <0.001 |

| --Other mental health condition | 106 (16) | 35 (1) | <0.001 |

| --Other physical health condition | 147 (23) | 198 (8) | <0.001 |

| No health problems | 34 (6) | 887 (34) | <0.001 |

| SARS-CoV-2 positive test (self-report)e | |||

| Yes | 82 (13) | 302 (12) | 0.630 |

| No | 571 (87) | 2296 (88) | |

| Receipt of COVID-19 vaccination (self-report)f | |||

| Full vaccination | 471 (72) | 2053 (79) | 0.004 |

| Partial vaccination | 19 (3) | 31 (1) | |

| Unvaccinated | 161 (25) | 499 (19) | |

This count includes only those survey respondents who had a recorded disability and SARS-CoV-2 status (N = 3251). Statistical weighting was used to align the sample with U.S. population distributions, adjusting for gender, age, household income, race/ethnicity, household size, education, census region, and metropolitan status. Weights were designed to match the U.S. Census' American Community Survey (ACS) proportions for these variables. Metropolitan status, which is not available from the 1-year ACS, were obtained from the Current Population Survey (CPS) March 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC).

With disabilities includes persons aged ≥18 years who reported having serious difficulty with vision, hearing, mobility, cognition, self-care, or independent living. Excludes respondents whose disability status was unknown.

Participants who reported a race other than non-Hispanic White or Black, including Asian, American Indian, Alaskan Native, and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander or reported 2 or more non-Hispanic races.

States included in census regions: Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania; Midwest: Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota; South: Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas; West: Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Montana, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington.

The exposure of interest was SARS-CoV-2 infection, measured by one or more positive SARS-CoV-2 test results since January 2020. Respondents self-reported ever having received a positive test result, always receiving a negative test result, or never having been tested for SARS-CoV-2. Respondents who reported having received a positive (“reported a positive test”) or only negative test results (“reported only negative tests”) were included in the analysis.

Vaccination status was defined as follows: Full vaccination: reported receiving one dose of Johnson & Johnson and two or more doses of Pfizer or Moderna; partial vaccination: reported receiving one dose of Pfizer or Moderna; and unvaccinated: did not report receiving any doses of a COVID-19 vaccine. At the time of the survey, up-to-date vaccination was defined as receiving one dose of Johnson & Johnson or two or more doses of Pfizer or Moderna.24 The survey was conducted prior to the recommendations of boosters,23 though 194 respondents received more than two vaccine doses.

Characteristics were compared among groups using a chi-square test, with p-values <0.05 indicating significant differences between respondents with and without disabilities.

The following three sub-sections present the results of this analysis for 1) all respondents (with or without disabilities); 2) respondents with disabilities; and 3) respondents without disabilities. The results under each subheading include results stratified by SARS-CoV-2 test history.

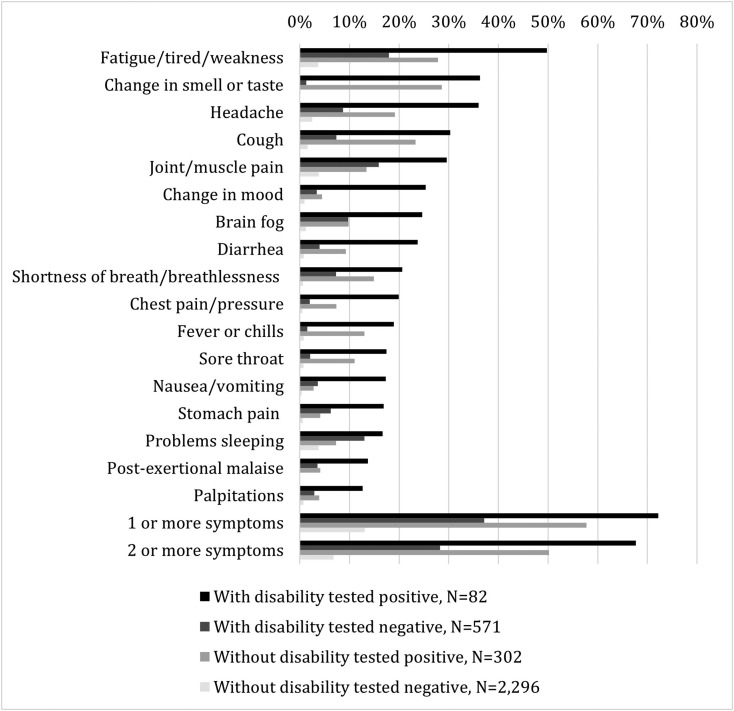

All respondents (with or without disabilities)

Many (n = 2330; 72%) respondents reported ≥1 symptom lasting >4 weeks. Symptoms were most frequently reported among respondents with disabilities who reported a positive test (72%) (Fig. 1 ). The most common long-term symptoms reported were "fatigue/tired/weakness," which were also most common among respondents with disabilities (50%) and without disabilities (28%) who reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 test. "Change in smell or taste" was also common among respondents with disabilities (36%) and without disabilities (29%) who reported a positive test.

Fig. 1.

Caption: Frequencies of symptoms lasting longer than 4 weeks among individuals with and without disabilities, stratified by self-reported SARS-CoV-2 test result∗ (N = 3251). Legend: (black box) With disability tested positive, N = 82, (medium gray box) Without disability tested positive, N = 302, (dark gray box) With disability tested negative, N = 571, (light gray box) Without disability tested negative, N = 2296. Footnote: ∗Statistical weighting was used to align the sample with U.S. population distributions, adjusting for gender, age, household income, race/ethnicity, household size, education, census region, and metropolitan status. Weights were designed to match the U.S. Census' American Community Survey (ACS) proportions for these variables. Metropolitan status, which is not available from the 1-year ACS, were obtained from the Current Population Survey (CPS) March 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC).

Among respondents who reported a positive test, we found no statistical evidence that those with disabilities were more likely than those without disabilities to have ≥1 long-term symptom (aOR = 1.65, 95% CI 0.78–3.50, p = 0.188) (Table 2 ). However, respondents with disabilities who reported a positive test were significantly more likely to report myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)-like symptoms, digestive symptoms, and symptoms lasting three to six months compared to respondents without disabilities who reported a positive test (Table 3 ).

Table 2.

Results of multivariable analyses estimating the odds of having symptoms lasting longer than 4 weeks and the odds of select duration of symptomsa among participants with disabilities who reported testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared to participants without disabilities who tested SARS-CoV-2-positiveb.

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)(ref: adults without disabilities) | P-value | |

| Symptoms for >4 weeks | ||

| One or more symptom | 1.65 (0.78, 3.50) | 0.188 |

| Two or more symptoms | 1.91 (0.86, 4.21) | 0.110 |

| Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome-like (ME/CFS-like) symptomsc | 2.60 (1.29, 5.24) | 0.008 |

| Digestive symptomsd | 3.07 (1.36, 6.91) | 0.007 |

| Change in taste or smelle | 1.68 (0.76, 0.37) | 0.197 |

| Upper respiratory symptomsf | 1.95 (0.90, 4.24) | 0.090 |

| One or more symptoms by different duration | ||

| 1–3 monthsa | 1.31 (0.57, 3.02) | 0.527 |

| 3–6 monthsa | 3.38 (1.19, 9.59) | 0.022 |

| 6–9 monthsa | 0.58 (0.06, 5.33) | 0.630 |

| 9–12 monthsa | 2.00 (0.38, 10.57) | 0.415 |

Duration of symptoms were mutually exclusive categories in the survey question but may overlap depending on how the respondent interpreted the survey question. For example, an individual who experienced three months of symptoms may have responded “1–3 months” or “3–6 months.”

Statistical weighting was used to align the sample with U.S. population distributions, adjusting for gender, age, household income, race/ethnicity, household size, education, census region, and metropolitan status. Weights were designed to match the U.S. Census' American Community Survey (ACS) proportions for these variables. Metropolitan status, which is not available from the 1-year ACS, were obtained from the Current Population Survey (CPS) March 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC). Odds ratios were adjusted for age category, sex, race/ethnicity, highest level of education completed, employment status, and census region.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome-like (ME/CFS-like) symptoms include change in mood, “brain fog,” fatigue/tired/weakness, joint/muscle pain, palpitations (heart racing or pounding), post-exertional malaise, problems sleeping, and shortness of breath/breathlessness. (See Appendix B.)

Digestive symptoms include diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, and stomach pain. (See Appendix B.)

Change in taste or smell, a specific symptom for COVID infection1, was asked as one question, rather than as two separate symptoms, as on other surveys of patients with PCC. (See Appendix B.)

Upper respiratory symptoms include cough and sore throat. (See Appendix B.)

Table 3.

Among individuals with and without disabilities, multivariable analyses estimating the odds of having long-term symptomsa and select duration of symptomsb by self-reported SARS-CoV-2 test statusc.

|

With disabilities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) (ref: adults with disability with a negative test history) | P-value | |

| One or more symptom | 4.50 (2.37, 8.54) | <0.001 |

| Two or more symptoms | 6.12 (3.10, 12.10) | <0.001 |

| Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome-like (ME/CFS-like) symptomsd | 3.78 (2.05, 6.99) | <0.001 |

| Digestive symptomse | 3.12 (1.51, 6.48) | 0.002 |

| Change in taste or smellf | 52.62 (19.11, 144.92) | <0.001 |

| Upper respiratory symptomsg | 9.46 (4.24, 21.11) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom for 1–3 monthsb | 8.19 (3.97, 16.90) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom for 3–6 monthsb | 9.73 (3.09, 30.62) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom for 6–9 monthsb | 1.38 (0.21, 9.31) | 0.738 |

| One or more symptom for 9–12 monthsb | 4.36 (0.86, 22.21) | 0.076 |

| One or more symptom for more than 12 monthsb | 0.38 (0.08, 1.94) | 0.246 |

|

Without disabilities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) (ref: adults without disability with a negative test history) | P-value | |

| One or more symptom | 9.88 (7.13, 13.71) | <0.001 |

| Two or more symptoms | 15.07 (10.27, 22.13) | <0.001 |

| Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome-like (ME/CFS-like) symptomsd | 9.88 (7.12, 13.71) | <0.001 |

| Digestive symptomse | 9.19 (4.48, 14.96) | <0.001 |

| Change in taste or smellf | 222.24 (76.57, 645.05) | <0.001 |

| Upper respiratory symptomsg | 18.00 (11.30, 28.69) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom for 1–3 monthsb | 12.61 (8.61, 18.46) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom for 3–6 monthsb | 11.16 (5.19, 24.00) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom for 6–9 monthsb | 38.43 (15.82, 93.36) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom for 9–12 monthsb | 19.55 (4.84, 79.03) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom for more than 12 monthsb | 1.22 (0.48, 3.12) | 0.676 |

Long-term symptoms were defined as symptoms lasting longer than 4 weeks since the respondent first experienced symptoms believed to be related to acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, and excluding symptoms that could be a side effect of getting a COVID-19 vaccine (within 7 days of vaccination). For those who never had documented infection.

Duration of symptoms were mutually exclusive categories in the survey question but may overlap depending on how the respondent interpreted the survey question. For example, an individual who experienced three months of symptoms may have responded “1–3 months” or “3–6 months.”

Statistical weighting was used to align the sample with U.S. population distributions, adjusting for gender, age, household income, race/ethnicity, household size, education, census region, and metropolitan status. Weights were designed to match the U.S. Census' American Community Survey (ACS) proportions for these variables. Metropolitan status, which is not available from the 1-year ACS, were obtained from the Current Population Survey March 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC).

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome-like (ME/CFS-like) symptoms include change in mood, “brain fog,” fatigue/tired/weakness, joint/muscle pain, palpitations (heart racing or pounding), post-exertional malaise, problems sleeping, and shortness of breath/breathlessness. (See Appendix B.)

Digestive symptoms include diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, and stomach pain. (See Appendix B.)

Change in taste or smell, a specific symptom for COVID infection, was asked as one question, rather than as two separate symptoms, as on other surveys of patients with PCC. (See Appendix B.)

Upper respiratory symptoms include cough and sore throat. (See Appendix B.)

Respondents with disabilities

Of the 82 respondents with disabilities who reported a positive test, 44% reported ≥1 long-term symptom lasting one to three months following their first positive test and 20% reported ≥1 symptom lasting three to six months following their first positive test (Supplemental Figure). Among respondents with disabilities who reported only negative tests, 15% reported ≥1 symptom lasting one to three months and 3% at three to six months after the most recent test date; similar results were reported at six to nine and nine to twelve months after the most recent test date. Respondents with disabilities who reported only negative tests had the highest percentage of reported symptoms twelve months or more after the most recent test date (14%; see Supplemental Figure).

The odds of having ≥1 long-term symptom were higher among those who reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 test than among those who reported only negative tests (aOR = 4.50, 95% CI 2.37–8.54, p < 0.001) (Table 3). Respondents with disabilities who reported a positive test were more likely to have symptoms up to three to six months after the test date than those who always reported negative tests (aOR = 9.73, 95% CI 3.09–30.62, p < 0.001), but this association was not statistically different six to nine months after the test date.

Respondents without disabilities

Of 302 respondents without disabilities who reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, 42% reported ≥1 symptom one to three months post-infection; 6% reported ≥1 symptom three to six months post-infection (See supplemental figure). In comparison, 7% of the 2296 respondents without disabilities with a negative test reported ≥1 symptom one to three months after the test result and 1% reported ≥1 symptom three to six months after their test result.

Similar to respondents with disabilities, respondents without disabilities were more likely to report long-term symptoms if also reporting a positive test rather than only negative tests (aOR = 9.88, 95% CI 7.13–13.71, p < 0.001) (Table 3). Respondents without disabilities who reported a positive test were more likely to have symptoms lasting three to six months than those who always reported negative tests (aOR = 11.16, 95% CI 5.19–24.00, p < 0.001). However, this association was not statistically significant more than twelve months after the test date (Table 3).

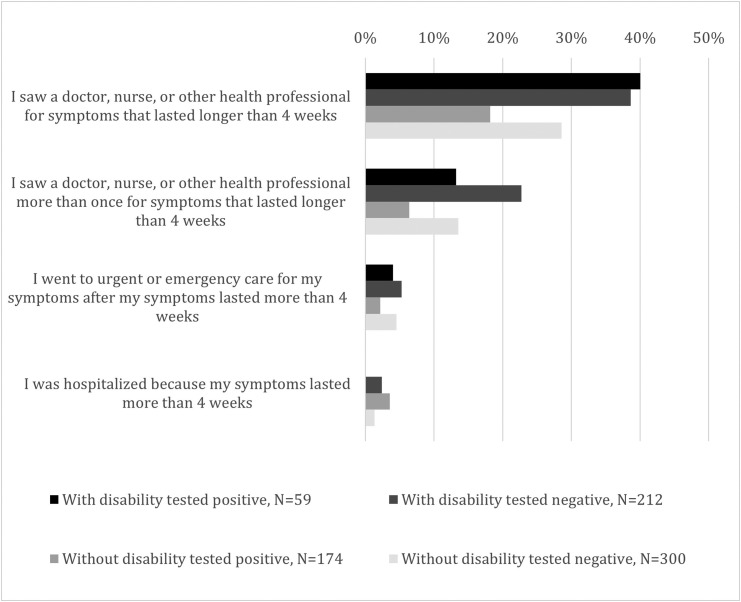

Health care utilization

Health care utilization for reported symptoms was higher among respondents with disabilities who tested positive than among respondents without disabilities who tested positive. Among respondents with disabilities, the proportion who saw a doctor, nurse, or other health professional for long-term symptoms was similar: 40% of those who reported testing SARS-CoV-2 positive and 39% who reported only negative tests. Among respondents without disabilities, 18% of those who reported a positive test sought health care for long-term symptoms compared to 29% of those who always reported negative tests (p = 0.03) (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Caption: Health utilization among individuals with and without disabilities who reported at least one symptom lasting for >4 weeks, stratified by self-reported SARS-CoV-2 test result, weighted. Legend: (black box) With disability tested positive, N = 59, (medium gray box) Without disability tested positive, N = 174, (dark gray box) With disability tested negative, N = 212, (light gray box) Without disability tested negative, N = 300.

Discussion

In this nationwide survey of U.S. adults, more than half of all respondents who self-reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result also reported ≥1 symptom lasting >4 weeks after the date of their first positive test result. This proportion did not differ significantly between respondents with or without a disability. Among respondents with disabilities, one in five (20%) reported symptoms still present three to six months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Health care utilization for reported long-term symptoms was more common among respondents with disabilities, and higher among respondents with disabilities who tested positive (40%) than among respondents without disabilities who tested positive (18%), with the caveat that only a subgroup responded to these questions.

Our finding that long-term symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection were common among respondents is consistent with the literature. A systematic review by Groff et al. estimated that over half of adults who have an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection may develop PCC.26 Many of these adults had underlying chronic conditions26 , 27 before they developed PCC. Consistent with other studies, we found a strong positive association between reporting a positive test and long-term symptoms, regardless of disability status.2 , 21 An analysis of PCC-like symptoms versus underlying symptoms associated with disability more generally is out of the scope of this study.

This is one of the first studies to estimate and compare ongoing long-term symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection among adults with and without disabilities.13 , 28 Tartof et al. found COVID-19-associated excess health care utilization in the six months following SARS-CoV-2 infection, but their study did not look at utilization by disability status.29 Adults with disabilities have more underlying chronic conditions, social vulnerability factors,6 and pandemic-related behavioral or mental health changes7 , 12 than adults without disabilities, and associated increased care needs and expenditures for social services.9 They experience greater challenges than adults without disabilities in accessing health care services30 (e.g., testing, vaccination, nonpharmaceutical interventions, clinic visits) and might be at higher risk for undiagnosed SARS-CoV-2, leading to missed cases13 (e.g., PCC in adults with intellectual disabilities).31 Adults with disabilities have been shown to have a lower likelihood of having received COVID-19 vaccination, attributed to difficulties obtaining a COVID-19 vaccine or (less likely) vaccine hesitancy.8 This information might help centers for independent living and other disability organizations anticipate how many new consumers with PCC they may receive, and how demand for these services could increase as more people with PCC gain eligibility for disability accommodations.

Though we hypothesized that adults with disabilities with SARS-CoV-2 infection are more likely to have PCC than infected adults without disabilities, we did not find a statistically significant association between the presence of ≥1 symptom in adults who self-reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 test and disability status. This might be because it can be difficult to distinguish symptoms related to underlying chronic conditions from symptoms of PCC. Many people with disabilities report underlying symptoms similar to PCC, even prior to infection. Similar differences were observed in this survey, with 5% of adults with disabilities reporting no underlying chronic conditions, compared to 34% of adults without disabilities. Persistent long-term symptoms were observed in respondents with disabilities who always reported negative tests for SARS-CoV-2, but these symptoms may reflect underlying chronic conditions which may overlap with PCC. A higher proportion of respondents without disabilities who reported a positive test reported underlying chronic conditions (70%) than respondents without disabilities who reported only negative tests (65%).

This cross-sectional study had several limitations. The survey did not capture when disabilities occurred relative to the presentation of symptoms, associated chronic conditions, or a positive SARS-CoV-2 test or receipt of COVID-19 vaccination,32 complicating the analysis of a direct connection between PCC and health care utilization. The analysis adjusted for age in multivariate models but did not compare respondents with and without disabilities directly or test for interaction between disability status and symptoms. These results cannot be used to estimate the risk of PCC attributable to SARS-CoV-2 infection. The respondents who agreed to join a survey panel might not be representative of the general population of U.S. adults. These data are subject to recall bias because respondents may have recalled symptoms differently depending upon their test status, frequency of testing, timing of when the illness occurred, chronic conditions, or intellectual and developmental disabilities. Respondents who self-reported a positive test might have been more likely to recall their symptoms. Also, respondents with disabilities were older than those without disabilities, potentially affecting reporting of underlying chronic conditions and severity of COVID-19 illness. Long-term symptoms in respondents with disabilities may have been missed as well, potentially affecting adjusted odds ratios estimates of PCC by self-reported disability and SARS-CoV-2 test status. The SARS-CoV-2 test histories were based on respondents' self-report and subject to misclassification (e.g., false negative). Frequency of testing may have had an impact on the likelihood of identifying a positive test; there was no clear way to evaluate how long symptoms lasted. Respondents who always received a negative test result might have had a longer period in which to report symptoms, potentially inflating the prevalence of long-term symptoms and health care utilization. The survey measured the prevalence and duration of symptoms (based on survey respondents’ self-report of how long symptoms have lasted), but not intensity or severity. In addition, the survey did not ask about the date of infection or date of vaccination, so we could not determine precisely when a respondent tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, nor whether vaccination played a role in the burden of PCC. Results should be interpreted with caution, given the small sample size of people with disabilities who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusion

PCC is common among SARS-CoV-2-infected adults with or without disabilities. Longer duration of ongoing symptoms after infection and seeking health care for symptoms are more common among adults testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 with disabilities. Although adults with disabilities do not appear to have an increased occurrence of PCC compared to those without disabilities, any increase in their health care needs and utilization is important to address. Many adults with disabilities already experience challenges in accessing health services, and they may need different clinical management of their symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially if their long-term symptoms are difficult to distinguish from their underlying chronic conditions. Our findings raise awareness of PCC among adults with disabilities and their health care providers and caregivers. Continued monitoring and clinical care for long-term symptoms and reducing disparities in access to SARS-CoV-2 infection prevention and control measures are important. Reducing infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 with up-to-date vaccination (including booster administration) and nonpharmaceutical interventions can reduce the risk of COVID-19 illness and PCC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dena Bushman (Career Epidemiology Field Officer, Maine Department of Health and Human Services), Reed Magleby (CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service, New Jersey Department of Health), and Hannah Segaloff (CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service, Wisconsin Department of Health Services) who provided technical assistance with the sub-analysis of PCC symptom clusters in the multi-state survey. (See Appendix B.)

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101436.

Presentation

The materials in Appendix B were presented as an oral presentation at the 2022 CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service annual conference. All other parts of the manuscript are unpublished. They have not been presented at academic conferences.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. It was produced as part of the COVID-19 emergency response. This project was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report for this study.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.C.D.C. Post-COVID Conditions: Information for Healthcare Providers. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-conditions.html Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Romieu A.C., Carton T.W., Saydah S., et al. Prevalence of select new symptoms and conditions among persons aged younger than 20 Years and 20 Years or older at 31 to 150 days after testing positive or negative for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA Netw Open. 4 Feb 2022 2022;(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.47053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Underlying C.D.C. 2022. Medical Conditions Associated with Higher Risk for Severe COVID-19: Information for Healthcare Professionals.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan Y., Thierry J.M., Bull-Otterson L., et al. COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations among medicare beneficiaries with and without disabilities — United States, January 1, 2020−November 20, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 17 Jun 2022;71(24):791–796. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7124a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.28 Oct 2022. C.D.C. Disability Impacts All of Us.https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turk M.A., Mitra M. COVID-19 and people with disability: social and economic impacts. Disability and Health Journal. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okoro C.A., Strine T.W., McKnight-Eily L., Verlenden J., Hollis N.D. Indicators of poor mental health and stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic, by disability status: a cross-sectional analysis. Disability and Health Journal. 2021;14 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101110/1936-6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryerson A.B., Rice C.E., Hung M.C., et al. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination status, intent, and perceived access for noninstitutionalized adults, by disability status — National Immunization Survey adult COVID module, United States, May 30–June 26, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1 October 2021 2021;70(39):1365–1371. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7039a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khavjou O.A., Anderson W.L.H., Honeycutt A., et al. State-level health care expenditures associated with disability. Publ Health Rep. 2021;136(4):441–450. doi: 10.1177/0033354920979807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lunsky Y., Durbin A., Balogh R., Lin E., Palma L., Plumptre L. COVID-19 positivity rates, hospitalizations and mortality of adults with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities in Ontario, Canada. Disability and Health Journal. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schott W., Tao S., Shea L. COVID-19 risk: adult Medicaid beneficiaries with autism, intellectual disability, and mental health conditions. Autism. 2021:1–13. doi: 10.1177/1362361321103966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebrasseur A., Fortin-Bedard N., Lettre J., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on people with physical disabilities: a rapid review. Disability and Health Journal. 2021;14 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shakespeare T., Ndagire F., Seketi Q.E. Triple jeopardy: disabled people and the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 10 April 2021 2021;397:1331–1333. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown H.K., Saha S., Chan T.C.Y., et al. Outcomes in patients with and without disability admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J) 2022 January 31 2022;194:E112–E121. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter Novelli Styles https://styles.porternovelli.com/consumer-youthstyles/

- 16.Ipsos KnowledgePanel Accessed 21 April 2022. 2022. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/solutions/public-affairs/knowledgepanel?msclkid=bc1672f5c1ae11eca70492b1450649d6 [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Census Bureau . 2020. American Community Survey (ACS) March 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement, S1810: Disability Characteristics.https://data.census.gov/cedsci/all?q=disability [dataset] Accessed from. [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Census Bureau . 2020. Current Population Survey (CPS) Datasets.https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/cps/cps-asec.2020.html#list-tab-S0DSGKHMB58P2A9KF5 [dataset] Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 19.16 Sept 2020. C.D.C. Disability and Health Overview.https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 20.2022. U.S. Census Bureau.How disability data are collected from the American community survey.https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-collection-acs.html Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanga V., Chevinsky J.R., Dimitrov L.V., et al. Long-term symptoms among adults tested for SARS-CoV-2 — United States, January 2020−April 2021. MMWR Morb Wkly Rep. 2021;70(36) doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7036a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.C.D.C Archived COVID-19 Vaccination Schedules. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/archived-covid-19-vacc-schedule.html

- 23.Mbaeyi S., Oliver S.E., Collins J.P., et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendations for Additional Primary and Booster Doses of COVID-19 Vaccines — United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 5 Nov 2021 2021;70:1545–1552. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7044e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.15 October 2021. C.D.C. When You’ve Been Fully Vaccinated: How to Protect Yourself and Others.https://public4.pagefreezer.com/browse/CDC%20Covid%20Pages/11-05-2022T12:30/https:/www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/fully-vaccinated_archived.html [Accessed 1 June 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konkle S.L., Magleby R., Segaloff H., et al. Post-COVID Condition Symptom Clusters and Associations with Return to Pre-COVID Health — Results from a 2021 Multi-State Survey. CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service 2022 Annual Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA. 2-5 May, 2022. (oral presentation) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groff D., Sun A., Ssentongo A.E., et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 13 Oct 2021 2021;4(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nalbandian A., McGroder C., Stevens J.S., et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med (New York, NY, U S) April 2021 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saydah S.H., Brooks J.T., Jackson B.R. Surveillance for post-COVID conditions is necessary: addressing the challenges with multiple approaches. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07446-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tartof S.Y., Malden D.E., Liu I.A., al e. Health care utilization in the 6 Months following SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.25657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lund E.M., Ayers K.B. Ever-changing but always constant: "Waves" of disability discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(4) doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawlings G.H., Beail N. Long-COVID in people with intellectual disabilities: a call for research of a neglected area. Br J Learn Disabil. 2022 doi: 10.1111/bld.12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korves C., Izurieta H.S., Smith J., et al. Relative effectiveness of booster vs. 2-dose mRNA Covid-19 vaccination in the Veterans Health Administration: self-controlled risk interval analysis. Vaccine. 2022;S0264–410X(22):816–817. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.