Abstract

Background

In contrast with the last century, caries epidemiology has begun integrating enamel caries into determinations of caries prevalence and experience. The objective of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the caries status including estimations of enamel caries, of European adolescents.

Method

Four databases (Medline Ovid, Embase, CINAHL, and SweMed+) were systematically searched from 1 January 2000 through 20 September 2021 for peer-reviewed publications on caries prevalence and caries experience in 12–19-year-olds; that also included evaluations of enamel lesions. Summary estimates were calculated using random effect model.

Results

Overall, 30 publications were selected for the systematic review covering 25 observational studies. Not all studies could be used in the meta-analyses. Caries prevalence was 77% (n = 22 studies). Highest prevalence was reported in the age groups 16–19 years, and in studies where caries examinations were done before 2010. The overall mean DMFT score was 5.93 (n = 14 studies) and it was significantly lower among Scandinavian adolescents than among other European adolescents (4.43 vs. 8.89). The proportion of enamel caries (n = 7 studies) was 50%, and highest in the lowest age group (12–15 years). Results from the present systematic review reflected the caries distribution to be skewed at individual-, tooth- and surface levels; at tooth and surface level, also changed according to age.

Conclusions

Although studies in which the caries examinations had been done in 2010 or later documented a reduction in caries prevalence, caries during adolescence still constitutes a burden. Thus, the potential for preventing development of more severe caries lesions, as seen in the substantial volume of enamel caries during early adolescence, should be fully exploited. For this to happen, enamel caries should be a part of epidemiological reporting in national registers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-022-02631-2.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Caries prevalence, Caries experience, Adolescent

Introduction

Oral disease continues to constitute a global public health challenge. The most common oral disease globally is dental caries [1]. When occurring in the childhood years, caries may develop into a lifelong condition that tracks across adolescence and adulthood. Thus, it is worrying that in 2010, untreated caries in deciduous teeth was the tenth most prevalent health condition, affecting 9% of the global child population [1]. Surprisingly, from 1990 to 2015, global prevalence of untreated caries in deciduous and permanent teeth remained relatively unchanged [2]. These data also reveal that caries affected the permanent teeth of 5 billion people, with prevalence peaking in the 15–19-year-old group [2]. Although largely preventable, caries continues to be widespread, especially in many low- and middle-income countries [1]. In contrast, high-income countries have experienced a decrease in caries, most distinctly among 12-year-olds [3].

While a substantial number of epidemiologic studies have targeted childhood caries, few have focused on adolescents. Adolescence has been described as a period of continued behavioural development along a pathway established in childhood [4]. It is a critical life phase when the individual develops independence; peer interactions are gradually increasing, and parental control lessens. As a consequence, adolescent behaviour patterns differ from those in childhood and adulthood. Risk of caries in this phase of life is higher due to environmental factors such as a changing, sometimes poor, diet [5]; a lowering of oral hygiene standards [6, 7]; and a new independence for seeking, or avoiding, dental care [8]. The 12–15-year-old age group also faces a greater caries risk [9] due to newly erupted permanent canines, premolars, and second molars; 76 new tooth surfaces become exposed during this period. Adverse conditions around emerging teeth are another risk factor; good oral hygiene may be difficult, resulting in bacterial accumulation, which would promote the initiation of caries [10]. If favourable oral hygiene behaviours are not established before this period, it will be challenging for adolescents to maintain proper oral health hygiene [11].

Mejàre et al. observed a higher incidence of enamel caries on proximal surfaces among adolescents aged 12–15 years when compared to 20–27-year-olds [12]. The research group also found that the 12–15-year age group had a higher rate of caries lesion progression from the enamel-dentin border to the outer dentin compared with young adults [12]. In another study, Mejàre et al. [13] found that 11–12-year-old individuals with proximal caries experience showing visible radiolucency on bite-wing radiographs (BW) have a 2.5 times greater risk of developing new proximal enamel lesions than their counterparts with no such radiolucency. Caries when detected at the enamel stage, can be arrested or reversed, given the initiation of preventive strategies and non-operative treatment; thus, establishing good dental health habits, is clearly important.

Reproducible methods of dental caries evaluation have been described and measured for more than 70 years [14]. Even at that time, researchers were conscious of the possibility of caries arrest (inhibition of caries progression) and of the importance of an exact diagnosis of incipient or enamel caries as a therapeutic measure. Currently, inter-examiner reproducibility for enamel caries is acceptable, mostly due to the development of scientifically proven caries diagnostic criteria and examiner calibration routines [15, 16]. Regretfully, today national epidemiological surveys rarely assess enamel caries [17]. Caries prevalence in the population is thus underestimated, and the usefulness of the survey data in oral health care planning is undermined. However, a growing awareness is seen of the predictive strength of enamel lesions and their role in risk assessment [18], also, in the potential for managing future caries development through early, non-invasive treatment [19, 20]. Additionally, reporting caries patterns with enamel caries included at the individual, tooth, and surface levels is recognized as important for planning and evaluating oral health care [21]. In a lifespan perspective, preventive and early non-invasive treatment in adolescents is essential; caries control in this period will lay the foundation for good oral health in adulthood and reduce future costs for restoration and repair [22].

Previous systematic review and meta-analyses on caries prevalence [2, 23, 24] have used the World Health Organization (WHO) caries diagnostic criteria [25] based on the Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth index (DMFT) [26]. By this criterion cavitation in the dentine is used for caries detection, thus ignoring the presence of enamel caries. Kale et al. [24] targeted children and adolescents aged 6–15 years in the Eastern Mediterranean region, while Kassebaum et al. [2] took a global perspective and included all ages. No systematic reviews and meta-analyses on caries have included a focus on enamel caries in a study population of European adolescents.

The aims of the present systematic review and meta-analyses were to determine the prevalence and experience of dental caries in European adolescents with particular emphasis on the role of enamel caries. Three research questions were investigated a) What is the overall caries prevalence and caries experience at various ages during adolescence, and do they vary by age, year of publication, year of caries examination, type of caries examination or geographical region? b) What proportion of the total caries experience does enamel caries constitute at various ages? c) What is the caries distribution at various ages during adolescence at the individual-, tooth-, and surface levels?

Methods

Search methods

Four electronic databases (Medline Ovid, Embase, CINAHL, and SweMed+) were systematically searched from 1 January 2000 through 20 September 2021. We also manually searched the reference lists of all included publications for other relevant citations. The search was restricted to publications published in peer-reviewed journals and written in English, German, Norwegian, Swedish or Danish. Additional file 1: 1 presents the search terms used in the four databases.

Selection criteria

Reviews assessing prevalence data must adhere to the CoCoPop (Condition, Context, and Population) mnemonic criteria [27]. The observational studies including cross-sectional, case–control, cohort designs (prospective or retrospective), and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (e.g., caries baseline reports before intervention, or caries data from the control group) were included.

Population

Adolescents 12–19 years living in Europe were selected to limit the populations to a more comparable Human Development Index (HDI) country (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_sovereign_states_in_Europe_by_Human_Development_Index) than if the same age group of the global population was selected. Table 1 outlines the characteristics of the studies and participants: publication year; year of examination; country; levels according to national, subnational (regions), and community (cities and small areas); gender; socio-economic status or position (SES/SEP); immigrant background; and age.

Table 1.

Background characteristics, applied examination and assessment and the targeted primary outcomes

| Background characteristics | Examination and Assessment | Primary outcomes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author, Publication year |

Year of exam Country Level |

Study design | Sample size (N) Total F: Female M: Male |

Socio-economic status/ -position (SES/SEP) Immigrant (IM) + : reported − : not reported |

Age (yrs) |

Diagnostic method (ref.) |

BW (Yes/No) |

Calibration (Yes/No) Examiners (N) |

Caries prevalence (%) (D(M)FS > 0 or D(M)FT > 0) 1: enamel level 2: dentine level |

Caries experience Mean DeS Mean D(M)FS or Mean DeT Mean D(M)FT with enamel caries included |

Proportion (DeS/D(M)FS or Proportion (DeT/D(M)FT |

Caries distribution + : reported −: not reported |

| Full mouth caries examination | ||||||||||||

|

Saethre-Sundli HB et al. [49] 2020 |

2014 Norway Subnational |

Cohort Exam. at Follow-up 2014 |

3,282 F: 1586 M: 1696 |

+ : Parental education Family status National background |

Mean age: 12.1 (SD: 0.5) |

Amarante E et al. [71] | Yes |

Yes 91 |

1: 58 2: 32 |

DeS: 1.35 DMFS: 2.15 (SD: 3.4) |

0.63 | + |

|

Jacobsen ID et al. [43] 2016 |

2010–2011 Norway Subnational |

Cross-sectional |

869 F: 420 M: 449 |

+ : National background Parental education Family status |

16 | Amarante et al. [71] | Yes |

Yes 1 |

1: 94 2: 83 |

- | - | - |

|

David J et al. [59] 2006 |

1993 Baseline |

Cohort Exam. at Baseline |

159 |

+ : Mothers’ education |

12 | Amarante E et al. [71] | Yes |

Yes 5 |

1: 90 2: 63 |

DeS: 6.2 (SD: 5.9) DMFS: 8.9 (SD: 7.8) |

0.70 | + |

|

1999 Follow-up Norway Community |

Exam. at Follow-up |

112 F: 56 M: 56 |

18 | Amarante E et al. [71] | Yes |

Yes 1 |

1: 99 2: 92 |

DeS: 4.4 (SD: 4.5) DMFS: 13.1 (SD: 11.4) |

0.34 | |||

|

Karlsson F et al [51] 2019 |

2009 Baseline |

Cohort Exam. at Baseline |

159 F: 82 M: 77 |

- | 12 | Socialstyrelsen, 1988 [72] | BW on indication only |

No -: number examiners not reported |

1: 48 2: not reported |

*DeS: 1.1 (SD: 2.3) DFS: 1.8 (SD: 2.9) |

*0.61 | - |

|

2014 Follow-up Sweden Community |

Exam. at Follow-up |

159 F: 82 M: 77 |

17 |

1: 55 2: not reported |

*DeS: 2.6 (SD: 4.2) DFS: 4.5 (SD: 6.1) |

*0.58 | ||||||

|

Koch G et al. [54] 2017 |

2013 Sweden Community |

Cross-sectional |

101 F: 49 M: 52 |

- | 15 | Koch G [73] | Yes |

Yes 3 |

1: 57 2: not reported |

DFS: 3.0 (CI: 1.9–4.1) | - | + |

|

Jacobssen B et al. [74] 2011 |

2003 Sweden Community |

Cross-sectional |

85 IM: 11 |

+ : Education National background |

15 |

Koch G [73] |

Yes |

Yes 8 |

1: 81 2: not reported IM: 1: 100 2: not reported |

- IM DFS: 11.8 (CI: 5.4–18.3) |

- | - |

|

Non IM: 74 |

Non IM: 1: 78 2: not reported |

Non IM: DFS: 5.5 (CI: 3.9–7.1) |

||||||||||

|

Hugoson A al. [55] 2008 |

2003 Sweden Community |

Cross-sectional |

96 F: 51 M: 45 |

- | 15 | Koch G [73] | Yes |

Yes 10 |

1: 80 2: not reported |

DeS: 4.7 DFS: 6.4 (CI: 4.8–8.0) |

0.73 | + |

|

Agustsdottir H et al. [50] 2010 |

2004–2005 Iceland National |

Cross-sectional | 757 | - | 12 | ICDAS | Yes |

Yes 1 |

1: 85 2: 66 |

*DeS: 5.67 (SE:0.47) DMFS: 8.77 (SE:0.64) |

*0.65 | + |

| 750 | 15 |

1: 94 2: 80 |

*DeS: 10.66 (SE: 0.80) ( DMFS: 17.00 (SE:1.10) |

*0.63 | ||||||||

|

Splieth CH et al.[45] 2019 |

2016 Germany National |

Cross-sectional | 55,002 |

+ : School type Class level |

12 | WHO [25] + initial caries lesions (IT) | No |

Yes 482 |

1: 34 2: 21 |

DeT: 0.52 DMFT: 0.96 |

0.54 | + |

|

Jablonski-Momeni A et al. [46] 2014 |

2009–2010 Germany Subnational |

Cross-sectional |

2 regions (969) Region 1: 525 |

+ : Mothers’ education National background |

12 | ICDAS | No | Yes |

1: 43 2: 23 |

*DeS: 0.77 DFS: 1.61 |

*0.48 | + |

|

Region 2: 444 |

Yes 1 |

1: 50 2: 17 |

*DeS: 1.7 DFS: 2.80 |

*0.61 | ||||||||

|

Wang X et al. [37] 2021 |

2013 England, Wales, Northern Ireland National |

Cross-sectional(analyses of clusters) |

2160 Cluster analyses: |

+ : School type Free school meals eligibility Deprivation Index (IMD) Region category National background |

15 | ICDAS [75] | No | From dental records (available data) |

1: not reported 2: not reported |

DeS: 1.73 DMFS: 4.39 CI: 3.60- 5.18) |

0.39 | + |

|

Wang X et al. [21] 2021 |

2013 England, Wales, Northern Ireland National |

Cross-sectional | 2532 |

+ : School type Free school meal eligibility Deprivation Index (IMD) Region category National background |

12 | ICDAS | No |

Yes 75 |

1: 65 2: 45 |

DeS: 1.61 DMFS: 3.91 (SD: 5.90) |

0.41 | + |

| 2418 | 15 |

1: 73 2: 59 |

DeS: 2.02 DMFS: 5.94 (SD: 8.04) |

0.34 | ||||||||

|

Vernazza CR et al. [38] 2016 |

2013 England, Wales, Norhern Ireland National |

Cross-sectional | 9866 (number included also 5-, 8- year-olds) |

+ : Free school meals eligibility Gender |

12 | ICDAS | No |

Yes 75 |

1: 57 2: approximately 33 |

DeT: 1.2 DMFT: 2.0 |

0.60 | - |

| 15 |

1: 63 2: approximately 50 |

DeT: 1.5 DMFT: 2.9 |

0.52 | |||||||||

|

Baciu D et al. [52] 2015 |

2011 UK Community (n = 5) |

Cross-sectional |

592 F: 323 M: 269 |

+ : Regions |

Mean age: 12.3 | ICDAS | No |

Yes 1 |

1: 83 2:76 |

*DeS: 1.71 (SD: 2.10) DMFS: 6.78 (SD: 7.25) |

*0.25 | - |

|

Maldupa I et al. [48] 2021 |

2016 Latvia National |

Cross-sectional |

2138 F: 1031 M: 1107 |

+ : Region Socio-economy (Family Affluence Scale (FAS)) |

12 | ICDAS II | No |

Yes 7 |

1: 99 2: 80 |

*DeS: 12.6 (SD: 10.5) DMFS: 17.6 (SD: 13.2) |

*0.72 | + |

|

Deery C et al. [76] 2000 |

1997 Latvia Community |

Cross-sectional |

182 F: 102 M: 80 |

- | Mean age: 13.3 (range: 10.6–15.7) | Deery et al. [77] |

No Visual examination (CVE) |

Yes 1 |

1: not reported 2: 99.5 |

DeS: 10.38 (SD: 11.68) DMFS: 22.65 |

0.46 | - |

|

Almerich-Torres T et al. [41] 2020 |

2018 Spain Community |

Cross-sectional | 632 |

+ : Social class by parental occupation |

12 | ICDAS II | No |

Yes 3 |

1: not reported 2: 30 |

DeS: 1.67 DMFS: 2.41 |

0.69 | - |

| 534 | 15 |

1: not reported 2: 45 |

DeS: 2.03 DMFS: 3.39 | 0.60 | ||||||||

|

Almerich-Torres T et al. [39] 2017 |

2010 Spain Community |

Cross-sectional |

409 F: 216 M: 193 |

+ : Social class by parental occupation (Domingo et al.) |

12 | ICDAS II | No |

Yes 3 |

1: not reported 2: not reported |

DeT: 2.57 DMFT: 3.44 (CI: 3.08–3.80) |

0.75 | - |

|

433 F: 226 M: 207 |

15 |

DeT: 3.66 DMFT: 4.74 (CI: 4.37–5.11) |

0.77 | |||||||||

|

Almerich-Silla JM et al. [40] 2014 |

2010 Spain Community |

Cross-sectional | 1373 |

+ : Social class by parental occupation (Domingo et al.) |

12 | ICDAS II | No |

Yes 6 |

1: 77 2: 38 |

DeS: 3.18 DMFS: 4.45 (CI: 3.96–4.93) |

0.71 | - |

| 15 |

1: 85 2: 44 |

DeS: 4.23 DMFS: 5.87 (CI: 5.36–6.37) |

0.72 | |||||||||

|

Calado R et al. [47] 2017 |

2009 Portugal National |

Cross-sectional | 1309 |

+ : Mothers’ occupation and education Area of residence Region |

12 | ICDAS | No |

Yes 24 |

1: 76 2: 47 |

DeS: 3.40 (SD: 0.17) DMFS: 8.61 (SD: 0.34) |

0.39 | + |

| 1075 | 18 | No |

1: 89 2: 68 |

DeS: 4.36 (SD: 0.20) DMFS: 16.64 (SD: 0.51) |

0.26 | |||||||

|

Campus G et al. [60] 2020 |

2017 Italy National |

Cross-sectional |

7064 F: 3605 M: 3459 |

+ : Income inequality and Unemployment rate Parental education Working status National background |

12 | ICDAS [78] | No |

Yes 4 |

1: 70 2: not reported |

DeT: 2.29 DFT: 3.71 |

0.62 | - |

|

Diamanti I et al. [57] 2021 |

2013 Greece National |

Cross-sectional |

1243 F: 631 M: 612 |

+ : Urban/rural area of residence Parental education |

12 | ICDAS II | No |

Yes 10 |

1: 72 2: 52 1: F: 74 1: M: 69 2: F: 54 2: M: 50 |

- *F: DeT: 1.8 (SD: 2.5) DMFT: 3.6 *M: DeT: 1.7 (SD: 2.6) DMFT: 3.1 |

*F: 0.50 *M: 0.55 |

- |

|

1227 F: 658 M: 569 |

15 |

1: 82 2: 66 1: F: 79 1: M:86 2: F: 68 2: M: 63 |

- *F: DeT: 2.6 (SD: 3.2) DMFT: 5.2 *M: DeT: 2.4 (SD: 3.1) DMFT: 4.7 |

*F: 0.50 *M: 0.51 |

||||||||

| Partial mouth caries examination (proximal surfaces of posterior teeth). One study also included occlusal surfaces | ||||||||||||

|

Jacobsen ID et al 2019 [42] |

Jacobsen ID et al. Norway. Details under full mouth caries examination |

1: 84 2: not reported |

DeAS: 5.8 (SD: 5.0) | - | - | |||||||

|

Bergström EK et al [53] 2019 |

2005- |

Cohort Controls: Exam. at Baseline |

Control group: 10,160 F: 4923 M: 5237 |

+ : Geographical area | 12 | Gröndahl et al. [80] | Not reported | Not reported |

1: not reported 2: not reported |

DeAS: 0.86 DAFS: 1.08 |

0.80 | - |

|

2008 Sweden Subnational |

Controls: Exam. at Follow-up | 15 |

DeAS:2.19 DAFS: 2.88 |

0.76 | ||||||||

|

Alm A et al. [56] 2006 |

2002 Sweden Community |

Cohort Exam. at Follow-up |

568 F: 286 M: 282 ??? |

+ : Socio-economic regions |

15 | Socialstyrelsen [72] | Yes |

Yes 1 |

1: 67 2: 22 |

DeAS: 2.78 (range 0–18) DAFS: 3.23 (Range:0–20) |

0.86 | - |

|

**Koch G et al [54] 2017 |

2013 Jönköping study, Sweden. Details under full mouth caries examination | 0.80–0.90 | ||||||||||

| Hugoson A et al. [55] 2008 | 2003 Jönköping study, Sweden. Details under full mouth caries examination | 0.80–0.90 | ||||||||||

|

Sköld UM et al. [79] 2005 |

1999–2003 Sweden Community |

Cohort Controls: Exam. at Baseline | 94 | - | 13 | Gröndahl et al. [80] | Yes |

No 2 |

1: not reported 2: not reported |

DAFS: 1.45 (SD: 2.17) | - | - |

| Controls: Exam. at Follow up | 16 |

1: not reported 2: not reported |

DA.FS: 3.29 (SD: 4.45) | |||||||||

|

Jacobsson B et al. [81] 2005 |

2003 Sweden Community |

Cross-sectional |

117 IM: 51 F: 27 M: 24 |

+ National background |

15 | Koch [73] | Yes |

No 4 |

1: 74 2: 44 1: IM: 76 2: IM: 47 |

IM: DeAS: 5.5 (CI: 4.0–7.0) DA.FS: 6.5 (CI: 4.7–8.2) |

0.85 | - |

|

Non IM: 66 F: 40 M: 26 |

1: Non IM: 74 2: Non IM: 42 |

Non IM: DeAS: 3.3 (CI: 2.3–4.4) DA.FS:: 4.0 (CI: 2.9–5.4) |

0.83 | |||||||||

|

Lith A et al. [82] 2002 |

1992–1993 Sweden Community |

Cross-sectional data From dental records |

285 |

+ : Income and education exceeded the average Swedish citizen |

17 |

Also occlusal lesions Gröndahl et al. [80] |

BW on indication only |

Yes -: number examiners not reported |

1: 93 2: 84 |

- | - | + |

|

Gustafsson A et al. [83] 2000 |

1993 |

Cohort Exam. at Baseline |

93 Analyzed 67 F: 34 M: 33 |

- | 14 | Gustafson et al. [83] | Yes |

Yes 2 |

1: 69 1: F: 76 1: M: 62 2: not reported |

- F: DeAS: 4.2 (SD: 5.5) DA.FS: 4.82 M: DeAS: 2.9 (SD: 43.9) DAlFS: 3.62 |

- F: 0.87 M: 0.80 |

- |

|

1998 Sweden Community |

Exam. at Follow-up |

Analyzed 66 F: 33 M: 33 |

19 |

1: 92 1: F. 91 1: M: 94 2: not reported |

- F: DeAS: 7.0 (SD: 4.7) DA.FS: 9.7 M: DeAS: 6.1 (SD: 4.7) DAFS: 10.6 |

- F: 0.72 M: 0.58 |

||||||

|

Pooerterman JHG et al [84] 2003 |

1990 |

Cohort From radiographs |

121 | - | 14 | Poorterman JHG. [85] | Yes |

Yes 2 |

1: 86 2: not reported |

DeAS:2.7 (SD: 3.1) DA.FS: 3.73 |

0.72 | - |

|

1993 The Netherlands Community |

From radiographs | 311 | 17 |

1: 88 2: not reported |

DeAS: 3.8 (SD: 1.1) DA.FS: 7.0 |

0.54 | ||||||

The first part of the table consists of publications based on full mouth caries examination and the second one, on articles from partial caries examination (both places arranged after country of origin). Within these sections, the publications are presented consecutively according to publication date

DeS: Surfaces with enamel caries (without– and with cavitation). DeAS: Proximal (approximal) DeS. DeT: Teeth with enamel caries (without– and with cavitation). D(M)FS: decayed (enamel and dentine caries)/(missed)/filled permanent surfaces. D(M)FT: decayed (enamel and dentine caries)/(missed)/filled permanent teeth. In many studies the M-component is not counted because no or almost no teeth were extracted due to caries. If available surface level index, this the one which is denoted in the table. DA(M)FS: decayed (enamel and dentine caries)/(missed)/filled approximal surfaces. Measures of variability (e.g. SD) are lacking in those cases components of mean caries experience have been calculated. Dental caries activity was not assessed

(*) In case that enamel caries omits cavitated lesions in enamel and as such underscores the DeS/ DeT component

(**) Article denoted in both categories; full mouth- and partial caries examination

Condition

The selected studies reported on dental caries in permanent teeth. All of them incorporated enamel caries (enamel caries with and without cavitation) which clinically implied any sign of caries in the enamel, and when radiographs were used, any radiolucency in enamel. The examinations were carried out either by full-mouth or partial-mouth examination (examination of proximal lesions in posterior teeth). The outcome variables were caries prevalence at enamel threshold (D[M]FS [S: Surface] > 0 or D[M)]T > 0), prevalence at dentine threshold without enamel caries, mean total caries experience (mean D[M]FS or mean D[M]FT, including enamel lesions), the enamel caries proportion of this latter value, and presentations of caries distribution at the individual, tooth, and surface levels (Table 1).

Context

The context or specific settings relevant to caries prevalence and caries experience, were reported. The following subgroups were used in the meta-analyses: age (12–15 years vs. 16–19 years as well as 12–13 years vs. 16–19 years), publication year (< 2010 vs. ≥ 2010), caries examination year (< 2010 vs. ≥ 2010), mouth examination (full- vs. partial-mouth), and region (Scandinavia [Norway, Sweden, Denmark] vs. rest of Europe).

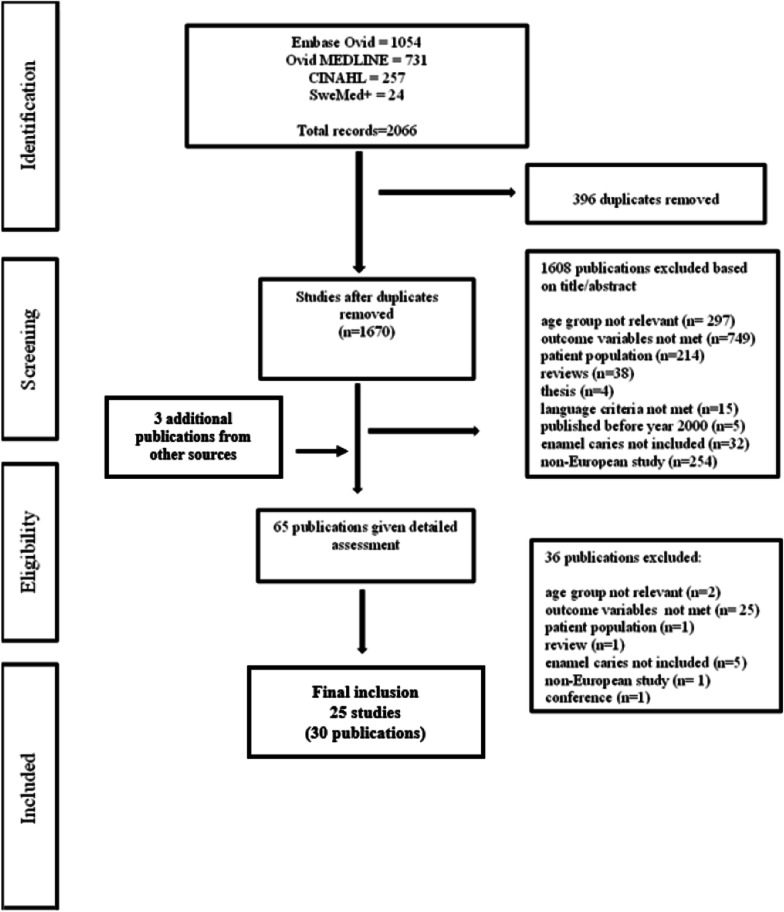

Exclusion criteria

Figure 1 illustrates the selection of studies, with reasons for exclusion, in a flow chart. Studies not reporting enamel caries and studies examining groups with various medical problems were excluded. Studies comparing populations exposed to low or high-water levels of fluoride were also excluded [28–30]. Adolescents under 12 years of age were excluded to avoid results from the deciduous dentition being included in the data. Not all publications selected for the present systematic review could be included in the meta-analyses because some publications represented the same study and were considered as one study in the meta-analysis; some did not report the exact sample size of the adolescent groups, only the total sample size; and some only reported estimates of caries prevalence, not caries experience, or vice versa. Additionally, mean caries experience of enamel caries (mean DeS) or of total caries (mean D[M]FS with enamel lesions included), was sometimes reported without 95% confidence intervals (CI), standard deviations (SD) or Standard errors (SE). These studies were also excluded. Lastly, publications reporting total caries experience on the tooth level (D[M]FT) were also omitted as only a few did so and a meta-analysis can only be done on comparable values.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

Data extraction

Two reviewers (MSS, KSK) independently evaluated articles for inclusion in the study. Articles were first selected based on the title. The reviewers then read the abstracts of these articles, followed by the full-text article if the study was within the scope of the research questions in the present study. Both reviewers then re-read the full-text articles that had been selected to determine final inclusion in the study; in cases of doubt, a third author (AS) read the article and discussed it with the reviewers to reach a consensus.

Critical appraisal

We assessed risk of bias using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Instrument for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data, a revision of the JBI critical checklists for studies reporting prevalence data [27, 31]. The instrument evaluates nine items. The quality assessment of studies included were performed by two authors (MSS and KSK). In case of discrepancies, a third author (AS) was consulted (Additional file 1: 2). The instrument’s range of scores was from 0 to 11. Based on the scoring, overall, the studies were of good scientific quality. Two studies were scored equal to 8, all the others above 8.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 17.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Metaprop, a new command in Stata was used to conduct meta-analyses of proportions which allows computation of exact binomial confidence intervals using the ci (method) option [32]. The subgroups and overall summary estimates of dental caries prevalence with inverse-variance weights were obtained using random-effects model. The metan command was used to estimate overall caries experience and approximate proportion of enamel caries via pooling of study-specific estimates (mean enamel caries experience divided by mean total caries experience) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals, using inverse variance method of the Der Simonian and Laird random effect model. Cochran’s Q test and I2 [33] were used to assess heterogeneity between studies; I2 is the total variation explained by between-study variation. A value above 60% was considered to be substantial heterogeneity. The influence analyses were performed by removing one study at a time to assess whether a single study changed pooled estimates. Subgroup analyses were done to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity (studies within and between the groups). Conventional funnel plots for assessing the publication bias were found to be inaccurate to determine proportional related studies (i.e., for caries prevalence) [34], thus, LFK index to detect and quantify asymmetry of study effects in Doi plots. However, for mean caries experience, conventional Egger’s test [35] and Begg’s test [36] as well as funnel plots were inspected to assess publication bias. If p < 0.10 or if there was asymmetry in the funnel plots, the results were considered to indicate publication bias. Due to the low number of studies, no publication bias assessment was done for the meta-analysis of the proportion of enamel caries. Sensitivity analyses were done by omitting one study at a time to check the robustness of the findings. For each study, the displayed effect size corresponds to an overall effect size computed from a meta-analysis excluding that study. In addition, the plot also displays a vertical line at the overall effect size based on the complete set of studies (with no omission) to help detect influential studies.

Results

In total, 30 publications (Table 1), all published in English, met the inclusion criteria for the present systematic review; together, these publications reported data on approximately 92,780 adolescents (the exact number is unknown since some samples included younger age groups). Europe currently (year 2021) comprises 44 countries (https://www.worldometers.info/geography/how-many-countries-in-europe/); these publications cover 11 of the countries (25%). No publication studied populations in the 14 European countries with the lowest economic background according to GDP per capita (Gross domestic product divided by the total population) (https://www.thetealmango.com/featured/poorest-countries-in-europe/).

Three publications used data from UK’s the 2013 Children’s Dental Health Survey (CDHS) [21, 37, 38]. For meta-analysis, we used the publication with the highest sample size [21]. Three publications used survey data from the Valencia region of Spain [39–41], again the publication with the highest sample size was included in the meta-analysis [40]. Finally, of the two publications from the oral section of the “Fit Futures” study in Troms county, Norway [42, 43], the study presenting full-mouth caries data was used for meta-analysis [43], because the other publication only partially covered the study. Hence, in total 25 studies were included (30 publications). The types of caries examination varied. Of 30 publications, 22 publications reported caries based on full-mouth examination, of these, two included both full and partial mouth data. Eight of the publications were solely based on partial mouth examinations.

Ten publications were from the 2000s, 14 from the 2010s and six from the 2020s. Swedish publications were in the majority (n = 11). The majority of all publications (n = 17) included caries data of 12-year-olds, either as the only age group or together with other age groups. All studies (n = 25) were observational, mostly with cross-sectional designs (n = 18). In studies with cohort designs (n = 7), examination data were collected cross-sectionally, at baseline, at follow-up, or at both sessions. Cohort studies with intervention collected caries data from the control group (n = 2). The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) [44] was the caries diagnostic method most often used, but its Code 3 (visual change in enamel with cavitation) could not be separately quantified in all studies and hence, was not included in the total magnitude calculated for enamel caries. Table 2 shows the criteria of the different diagnostic tools for enamel caries.

Table 2.

The criteria for enamel caries (with and without cavitation) in the different diagnostic tools used

| Diagnostic tools | Clinical examination | Radiographical examination |

|---|---|---|

| Full mouth caries examination | ||

| Amarante et al. 1998 [71] | ||

| Grade 1 | Occlusal: White or brown discoloration in enamel. No clinical cavitation. No radiographic evidence of caries | Proximal: Radiolucency in outer half of enamel |

| Grade 2 | Occlusal: Small cavity formation, or discoloration of the fissure with surrounding grey/opaque enamel and/or radiolucency in enamel on radiograph | Proximal: Radiolucency in inner half of enamel |

| Socialstyrelsen, 1988 (National Board of Health and Welfare) [72] | ||

| Initial caries (Di) | Loss of mineral in the enamel causing a chalky appearance but without any clinical cavitations | Not reported as radiographs were performed on individual indication only |

| Koch G, 1967 [73] | ||

| Initial caries | Loss of mineral in the enamel causing a chalky appearance but not clinically classified as a cavity | The lesion restricted to the enamel |

| The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (many researchers have contributed developing the criteria [44, 75, 78] | ||

|

ICDAS (see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5030492/) ICDAS II criteria (see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5573507/) |

||

| Code 1 | Smooth tooth surfaces: A loss of mineral in the enamel causing a chalky appearance, but without any clinical cavitations | |

| Code 2 | Distinct visual change in enamel: The tooth must be viewed wet. When wet there is a (i) carious opacity (white spot lesion) and/or (ii) brown carious discoloration which is wider than the natural fissure/fossa that is not consistent with the clinical appearance of sound enamel (Note: the lesion must still be visible when dry) | |

| Code 3 | Localized enamel breakdown because of caries with no visible dentin or underlying shadow | |

| Splieth CH et al., 2019 [45] | ||

| IT Initial caries lesions with no precise description | ||

|

Deery C et al., 1995 [77] Clinical visuals examination (CVE) alone |

||

| W | ||

| B | White spot enamel caries | |

| Brown spot enamel caries | ||

| E | Enamel caries with breakdown of surface | |

| Partial mouth caries examination (proximal surfaces of posterior teeth) | ||

| Gröndahl et al., 1977 [80] | ||

| Based on BW: | (1) Caries lesion in the outer half of the enamel | |

| Based on BW: | (2) Caries lesion more than halfway through the enamel but not passing the enamel-dentin junction | |

|

Poorterman HJ et al., 2003 [84] Based on BW: |

A lesion confined to the enamel | |

| Gustavsson et al., 2000 [83] | ||

| Based on BW: | A lesion confined to the enamel |

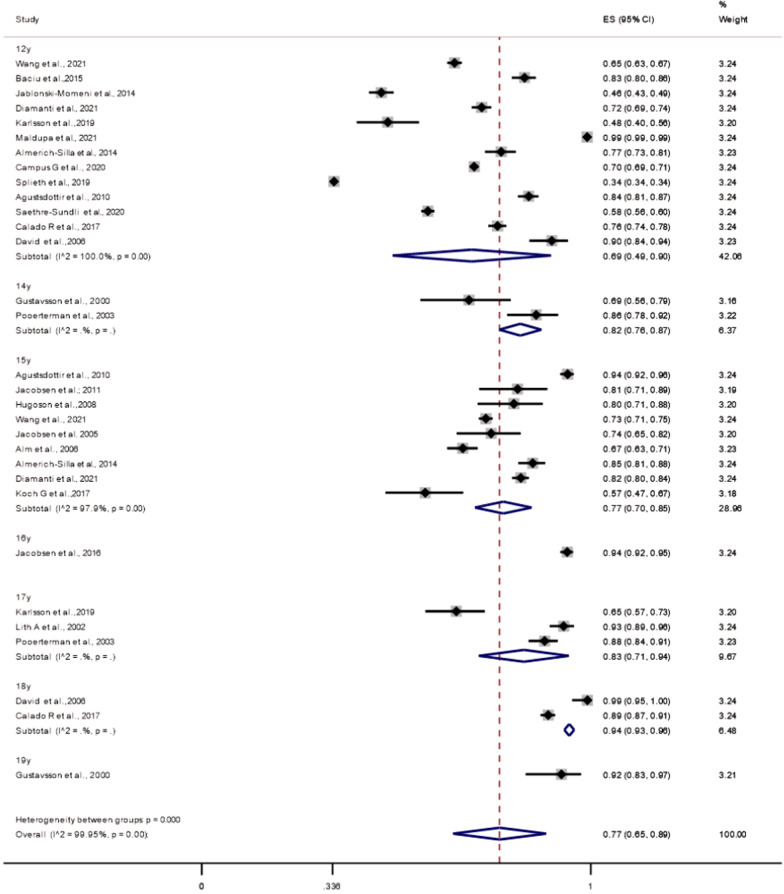

Caries prevalence

Of the 25 studies on caries prevalence at the enamel threshold, 22 were included to compute the summary estimates (participants: 84,512; cases with caries: 40,594). As all studies included in the meta-analysis from the Scandinavian countries, diagnosed caries using both clinical- and radiographic examinations, only two non-Scandinavian applied radiographs. Figure 2 shows that the overall prevalence of caries in 12–19-year-old adolescents was 77% (95% CI 49–81%; I2 = 99.95%; P-heterogenity < 0.001). In the subgroup analyses (Table 3), we found a significantly higher caries prevalence among 16–19-year-olds compared with 12–15-year-olds (P-heterogeneity: 0.028). When analyses by age group (12–13 vs. 16–19) were performed, there were still a little evidence of heterogeneity between the groups (P-heterogeneity: 0.057). We also found a significantly higher caries prevalence in adolescents examined before 2010 (1990–2010) than those examined later (P-heterogeneity: 0.001). Especially noticeable among 12-year-olds was a pattern of cross-country variation in caries prevalence. Two studies on German 12-year-olds reported the lowest caries prevalence [45, 46].

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of caries prevalence when caries is diagnosed at enamel threshold

Table 3.

Analyses of caries prevalence, caries experience, and enamel caries as a proportion of total caries experience

| Subgroups | N | Summary estimates | Pheterogenity (within) | I2 | Pheterogenity (between) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caries prevalence (enamel caries threshold) | |||||

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 12–15 | 24 | 0.73 (0.59–0.87) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | 0.028* |

| 16–19 | 7 | 0.90 (0.85–0.94) | < 0.001 | 95.2% | |

| Publication year | |||||

| < 2010 | 7 | 0.83 (0.75–0.89) | < 0.001 | 96.1% | 0.28 |

| ≥ 2010 | 15 | 0.72 (0.54–0.89) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | |

| Examination year* | |||||

| < 2010 | 10 | 0.78 (0.70–0.87) | < 0.001 | 98.7% | 0.001 |

| ≥ 2010 | 11 | 0.74 (0.53–0.96) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | |

| Type of examination | |||||

| Partial-mouth | 5 | 0.81 (0.70–0.91) | < 0.001 | 99.7% | 0.48 |

| Full-mouth | 17 | 0.74 (0.57–0.90) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | |

| Europe geographical region | |||||

| Scandinavian | 11 | 0.76 (0.65–0.87) | < 0.001 | 99.1% | 0.88 |

| Non-Scandinavian | 11 | 0.74 (0.53–0.96) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | |

| Caries prevalence (dentine caries threshold) | |||||

| Publication year | |||||

| < 2010 | 4 | 0.56 (0.22–0.90) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | 0.78 |

| ≥ 2010 | 11 | 0.51 (0.36–0.66) | < 0.001 | 99.5% | |

| Type of examination | |||||

| Partial-mouth | 3 | 0.50 (0.06–0.94 | < 0.001 | 99.9% | 0.90 |

| Full-mouth | 12 | 0.53 (0.38–0.68) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | |

| Europe geographical region | |||||

| Scandinavian | 9 | 0.49 (0.32–0.67) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | 0.64 |

| Non-Scandinavian | 6 | 0.57 (0.32–0.81) | < 0.001 | 99.7% | |

| Caries Experience | |||||

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 12–15 | 17 | 5.58 (4.33–7.21) | < 0.001 | 99.7% | 0.41 |

| 16–19 | 4 | 7.61 (3.78–15.30) | < 0.001 | 98.9% | |

| Age grouping (years) | |||||

| Publication year | |||||

| < 2010 | 4 | 5.48 (4.27–8.47) | < 0.001 | 96.7% | 0.74 |

| ≥ 2010 | 10 | 6.24 (4.16–9.37) | < 0.001 | 99.9% | |

| Examination year* | |||||

| < 2010 | 7 | 7.54 (5.46–10.43) | < 0.001 | 97% | 0.41 |

| ≥ 2010 | 6 | 5.21 (2.30–11.81) | < 0.001 | 99% | |

| Type of examination | |||||

| Partial-mouth | 2 | 3.53 (1.62–7.70) | < 0.001 | 93.2% | 0.16 |

| Full-mouth | 12 | 6.56 (4.55–9.47) | < 0.001 | 99.8% | |

| Europe geographical region | |||||

| Scandinavian | 8 | 4.43 (2.52–7.81) | < 0.001 | 98.5% | 0.037* |

| Non-Scandinavian | 6 | 8.89 (6.41–12.33) | < 0.001 | 99.8% | |

| Enamel caries proportion | |||||

| Age groups (years) | |||||

| 12–15 | 8 | 0.56 (0.42–0.76) | < 0.001 | 99.6% | 0.10 |

| 16–19 | 3 | 0.37 (0.24–0.56) | < 0.001 | 99.8% |

I2 = proportion of total variation in effect estimate due to between-study heterogeneity (based on Q)

*Karlsson et al. (2019) was excluded because the caries examinations were done both before and after 2010

No indication of publication bias for caries prevalence (LFK index = 0.46; no asymmetry; Additional file 1: 3 and caries experience were apparent (Additional file 1: 4). Further, sensitivity analyses were performed by omitting one study at a time revealed a pooled effect size of dental caries prevalence in the range between 76 to 78% (Additional file 1: 5).

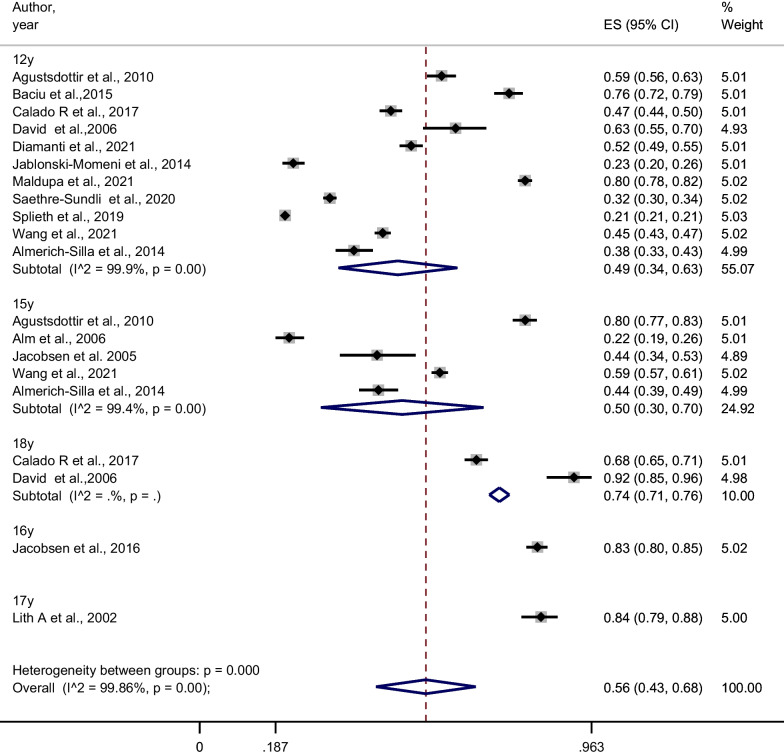

The overall caries prevalence when performed at the dentine threshold (n = 15 studies), Fig. 3, showed a mean caries prevalence of 56% (95% CI 43–68%; I2 = 99.86%; P-heterogenity < 0.001). Also, caries prevalence at dentine threshold showed no significance difference between studies according to publication year (< 2010 vs. ≥ 2010), mouth examination (full- vs. partial-mouth) and region (Scandinavia vs. rest of Europe) (Table 3). However, the prevalence at dentine level might be overestimated as 5 of the 15 included studies, dentine caries also included the ICDAS Code 3 (visual change in enamel with cavitation).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of caries prevalence when caries is diagnosed at dentine threshold

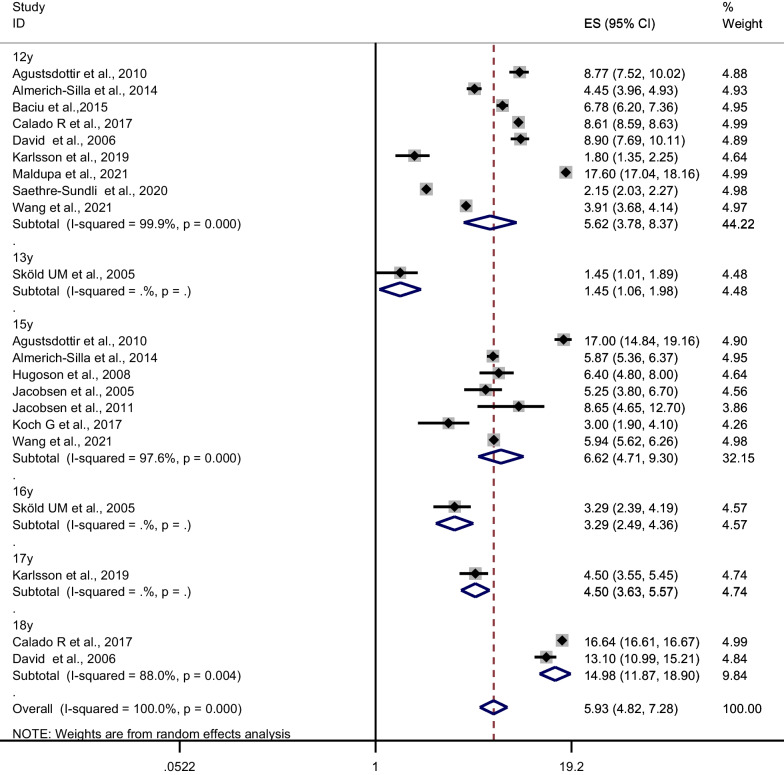

Caries experience

The present systematic review included 28 publications on caries experience; of these, 14 were eligible for meta-analysis (participants: 17,658). The overall mean estimate of caries experience (DMFS) in 12–19-year-old adolescents was 5.93 (95% CI 4.82, 7.28; I2 = 99.9%; P-heterogenity ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 4). Further, the subgroup analyses (Table 2) revealed only significant heterogeneity in caries experience by region with a significantly lower DMFS in Scandinavian countries than in the other European countries in the present study (P-heterogeneity: 0.037). A sensitivity analysis that omitted one study at a time suggested that pooled mean caries experience lies in the range 6.77–7.60 (see Additional file 1: 6).

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of caries experience (D[M]FS) when caries is diagnosed at enamel threshold

Further, we found some evidence of publication bias (Egger’s test for a regression intercept; P = 0.054), and an asymmetrical funnel plot. However, the evidence of publication bias appears to have been driven by relatively large studies [21, 47–49].We found no evidence of publication bias with Begg’s test (P = 0.78).

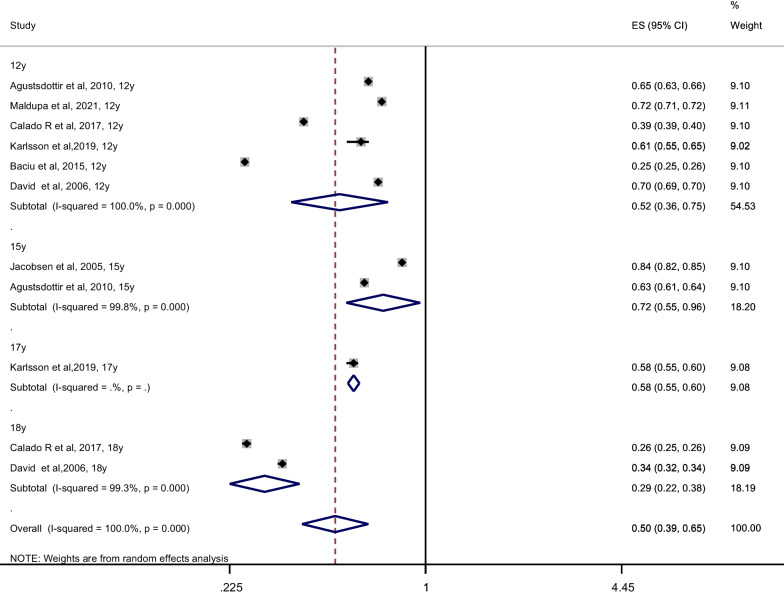

The D component—enamel caries

According to Fig. 5, only 7 of the 24 publications were included in meta-analysis computing the summary estimates of enamel caries (participants = 7056). The overall proportion of enamel caries was 0.50 (95% CI 0.39, 0.65; I2 = 99.6%; P-heterogenity < 0.001). When we performed a sensitivity analysis deleting one study at a time, the pooled proportion ranged between 0.50–0.57 (see Additional file 1: 7. The proportion of enamel caries in the 12–15-year age group was found to be slightly higher than in the 16–19-year age group, though the P for heterogeneity between the groups was non-significant (P = 0.10; Table 2). Four of the included 7 studies [48, 50–52] using ICDAS diagnostic criteria, underestimated the proportion of enamel caries because only enamel caries without cavitation was noted, not ICDAS Code 3.

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis of proportion of enamel caries

The Swedish studies of 12-and 15-year-olds [53] and of only 15-year-olds [54–56] in the present systematic review, not included in this meta-analysis, found that 80–90% of all proximal caries lesions were enamel caries. Enamel caries as a proportion of total caries (Table 1) was rather low in studies reporting a high total caries experience. As an example, a study from Portugal, published in 2017, found a substantially high caries experience among 12-year-olds (DMFS: 8.6; SD: 0.34) and 18-year-olds (DMFS: 16.64; SD: 0.51) [47] where enamel caries constituted 39% and 26%, respectively, of the total caries burden.

Caries distribution

No meta-analysis could be conducted since the reporting of caries distribution in the different studies (n = 11 studies) varied too much, both at individual-, tooth- and surface levels.

At the individual level

Six studies [45, 47–50, 57] used The Significant Caries (SiC) index [58] which measures the mean DMFT for one third of the population with the highest level of caries. The national German study on 12-year-olds [45] found the SiC-index to be three times higher than the mean DMFT of all participating 12-year-olds. Other studies also revealed that caries had a skewed distribution [38, 50, 54, 55]; e.g. the 2013 CDHS study in the UK [38] observed that 15% of the 15-year-olds had a severe caries burden. Different measures of socio-economic markers also displayed significant association with caries at individual level (results not shown).

At the tooth level

In participants aged 12 years, three studies observed the permanent first molars to be the teeth most often affected by caries [21, 48, 59]. One study of these [48] reported the mandibular first molars to be the most caries prone, while another [21] found no difference in caries prevalence between the four quadrants. The same study [21] which also included 15-year-olds, reported that the permanent second molars at that age were increasingly more caries prone. The teeth least affected by caries among 12- and 15-year-olds, were the lower anterior- and upper canine teeth [21]. By age 18 years, the first permanent molars had still the highest caries experience [59].

At the surface level

Some publications reported that the caries surfaces most often affected among 12- and 15-year-olds were the occlusal surfaces of the permanent molars and the buccal surfaces of the lower first molars [21, 46, 59]. In Sweden, however, the Jönköping epidemiological surveys in 15-year-olds [54, 55], reported that proximal surfaces were most often affected with caries of all surfaces. The 2013 CDHS study targeting 15-year-olds also revealed that the surface distribution of caries was influenced by the extent of the caries experience [37]; among those with low decay caries experience, caries mainly affected the occlusal and buccal surfaces of the permanent molars, but among those with extremely high decay experience, caries lesions affected almost all teeth, even the anterior surfaces of mandibular teeth.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis report on dental caries also including enamel caries among European adolescents. First, the studies included had a substantial level of statistical variability. The meta-analyses of caries prevalence suggested that 77% of the adolescents were affected by caries (n = 22 studies), with a significantly higher caries prevalence in 16–19-year-old group. Caries prevalence was also significantly higher among participants examined before 2010 compared with in 2010 and after, which indicates a caries reduction in recent years. Our meta-analysis of caries experience (n = 14) found significantly lower value among adolescents in Scandinavian countries than in European countries outside Scandinavia. In the meta-analysis of enamel caries proportion, it constituted 50% of the total caries experience (n = 7 studies); however, this proportion was higher in the 12–15 year than the 16–19-year age group. Other publications that were not included in the meta-analysis tended to confirm this finding, reporting enamel caries to constitute 80–90%. Thus, our findings have clearly revealed that when caries epidemiology omits consideration of enamel caries, the caries burden is seriously underreported. The systematic review also contained information about the distribution of caries (n = 11 studies). This information also confirmed findings in the literature that caries distribution was skewed, both at individual-, tooth- and surface level. At tooth and surface level, this distribution also changed according to age.

The present findings were not representative of the European continent since the search resulted in studies originated in only one-fourth of the countries and only a share of these reported caries on national levels [21, 37, 45, 47, 48, 50, 57, 60]. Germany reported the lowest caries prevalence with data for 12-year-olds [45, 46], but since bitewing radiographs were not taken, caries prevalence may be underestimated [46, 50]. The lower caries prevalence in Germany and sometimes in Scandinavia, may be due to the organization of dental health care and the focus on preventive care for this age group; free dental health care service in Germany through a comprehensive oral health insurance [61] and in Scandinavia, through publicly free provided oral healthcare services [62]. Although many countries in Southern Europe provide free public dental services for children, dental treatment of adolescents may still incur out-of-pocket costs [63]. Caries distributions at the individual level (not shown by meta-analysis) have indicated that a multitude of socio-demographic markers of caries also prevail in countries with free dental health care. As European countries are not homogeneous, a validated, measure comprising socio-economic markers would have benefitted our review by allowing inter-country comparisons [64].

It has been reported that enamel caries has a greater impact on caries estimates among school children with a higher SES compared with among those with a lower SES [65] and that enamel caries is more often a higher proportion of total caries in populations with low compared with high caries prevalence [66]. The dominance of enamel caries seen in 12- and 15-year-olds in Scandinavia (countries with a high HDI) [53–56] is consistent with this literature. Because caries progression is lower in individuals living in affluent conditions, the reasoning is that enamel caries is more likely to be identified [65].

Current knowledge that caries increases with age is consistent with this present meta-analysis of caries prevalence, showing a significantly higher prevalence in the 16–19-year-old group. We also observed higher DMFS scores in the older age groups compared with younger age groups, but the differences were not significant. The lack of significance may be both methodological and biological: methodologically, due to the high degree of clinical heterogeneity (e.g., inconsistency in sample size) [67] and biologically, due to the variability of caries risk during the adolescent years. The occlusal surfaces of the permanent second molars are at highest caries risk the first 3 years after eruption, during ages 12–15 years [12]. Likewise, following eruption and establishment of proximal contact in this same period, proximal surfaces of premolars and molars are at likelihood of new caries lesions [12], in particular the distal surfaces of the premolars and the mesial surfaces of the second molars [13]. Lesion progression from the enamel into the dentine, however, is reported to be relatively slow; surfaces affected by enamel caries survive a median of 4.8 years and 46% of enamel caries survive 15 years without progressing into dentine [12, 13]. This implies that enamel lesions most often occur in early adolescence and then progress during late adolescence. Mejàre and Kidd [68] observed that a caries-free 15–16-year-old runs a very small risk of experiencing new lesions over the next 3 years. It is therefore essential that especially during early adolescence, the great prevention potential visualized by the volume of enamel caries, should be fully exploited. When studies omit consideration of enamel lesions, the caries data simply demonstrate a failure of the optimal treatment option: the one being performed when the lesions were in the enamel stage.

The meta-analyses of both caries prevalence and overall caries experience did not differ significantly between partial- vs. full mouth examination. This finding is in line with the Swedish Jönköping surveys in 15-year-olds [54, 55], which found consolidation of proximal caries to be extensive during adolescence. The 2013 CDHS study from the UK showed that the level of caries experience influenced caries distribution [37]: the distribution of caries lesions among participating 15-year-olds differed between groups with low and extremely high decay experience. This supports the model of Batchelor and Sheiham, introduced 20 years ago, of grouping tooth surfaces by caries susceptibility [69].

Strengths

The most important strength of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was the inclusion of enamel caries in the definition of caries burden during the searches, thus allowing both the magnitude of enamel caries and its proportion of the total caries experience to be quantified. Including enamel lesions in the selection criteria means the present systematic review and meta-analysis is the first to accurately reflect modern dental caries epidemiology [70]. Our systematic review also looked at the distribution of lesions at the individual-, tooth-, and surface- levels, issues that were emphasized in the 2018 “Brussels statement on the future needs for caries epidemiology and surveillance in Europe”[64].

Limitations

Only limited studies could be included in the meta-analysis on the enamel proportion because most of the studies have not reported standard deviation or confidence intervals. Its meta-analysis result was also underestimated because in four out of seven included studies, accurate estimations of enamel caries were not possible. Other shortcomings were that some of the included publications provided little information on previous calibration procedures, some publications did not report the number of examiners or reported a high number, and use of bitewing radiography varied. Together with the skewed distribution of ages and fewer studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria outside Scandinavia, the present findings might not be considered representative of the European adolescent population.

Conclusion

Although studies in which the caries examinations had been done in 2010 or later documented a reduction in caries prevalence, caries during adolescence still constitutes a burden. Thus, the potential for preventing development of more severe caries lesions, as seen in the substantial volume of enamel caries during early adolescence, should be fully exploited. For this to happen, enamel caries should be a part of epidemiological reporting in national registers.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Seach strategy in four electronic databases; Medline Ovid, Embase, CINAHL, Sewed+ (Sept 20th 2021).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BW

Bitewing radiographs

- CoCoPop

Condition, Context, and Population

- DMFT/DMFS

Decayed/missed/filled permanent teeth/surfaces

- FAS

Family Affluence Scale

- ICDAS

International Caries Detection and Assessment System

- IMD

Indices of Multiple Deprivation

- HDI

Human Development Index

- JBI

Joanna Brigg’s Institute

- RCTs

Randomized Controlled Trials

- WHO

World Health Organisation

Author contributions

Two authors (MSS and AS) shared co-first authorship as they both worked together on the publication and contributed to the conception and design. MSS and KSK: read and assessed the abstracts and selected articles in full text. MSS: wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AS performed the statistical analyses. AS, GD, TNF, HH, KSK, actively participated in the interpretation of data and the writing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bergen. The study was financially supported by the Norwegian Directorate of Health, through their support for research at the Norwegian Centres for Oral Health Services and Research (https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/tilskudd/etablering-og-drift-av-regionale-odontologiske422kompetansesentre).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shared first authorship: Marit S. Skeie, and Abhijit Sen.

References

- 1.Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, et al. Oraldiseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394:249–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabe E, Fleming TD, Reynolds AE, Vos T, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J Dent Res. 2017;96:380–387. doi: 10.1177/0022034517693566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frencken JE, Sharma P, Stenhouse L, Green D, Laverty D, Dietrich T. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis - a comprehensive review. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(Suppl 18):94–105. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novak A, Pelaez M. What is adolescent behavioral development? In: Pelaez M, editor. Novak A. Child and adolescent development. A behavioral systems approach. London: Sage Publications; 2014. pp. 463–492. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newens KJ, Walton J. A review of sugar consumption from nationally representative dietary surveys across the world. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:225–240. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaktskjold A. Frequency of tooth brushing and associated factors among adolescents in western Norway. Norsk Epidemiologi. 2019;28:97–103. doi: 10.5324/nje.v28i1-2.3056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ericsson JS, Wennström JL, Lindgren B, Petzold M, Östberg AL, Abrahamsson KH. Health investment behaviours and oral/gingival health condition, a cross-sectional study among Swedish 19-year olds. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74:265–271. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2015.1112424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fagerstad A, Windahl J, Arnrup K. Understanding avoidance and non-attendance among adolescents in dental care - an integrative review. Community Dent Health. 2016;33:195–207. doi: 10.1922/CDH_3829Fagerstad13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mejàre I, Kallestal C, Stenlund H, Johansson H. Caries development from 11 to 22 years of age: a prospective radiographic study. Prevalence and distribution. Caries Res Keyword Heading Clinical study Dental caries Orthodontic appliances Prevalence. 1998;32:10–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Fejerskov O. Pathology of dental caries. In: Fejerskov O, Nyvad B, Kidd E, editors. Dental caries the disease and its clinical management. 3. London: Blackwell Munksgaard Ltd.; 2015. pp. 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen P. The health-promoting family: a conceptual framework for future research. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mejàre I, Stenlund H, Zelezny-Holmlund C. Caries incidence and lesion progression from adolescence to young adulthood: a prospective 15-year cohort study in Sweden. Caries Res. 2004;38:130–141. doi: 10.1159/000075937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mejàre I, Källestål C, Stenlund H. Incidence and progression of approximal caries from 11 to 22 years of age in Sweden: A prospective radiographic study. Caries Res. 1999;33:93–100. doi: 10.1159/000016502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backer Dirks O, Van Amerongen J, Winkler KC. A reproducible method for caries evaluation. Dental Res. 1951;30:346–359. doi: 10.1177/00220345510300030701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fyffe HE, Deery C, Nugent ZJ, Nuttall NM, Pitts NB. Effect of diagnostic threshold on the validity and reliability of epidemiological caries diagnosis using the Dundee Selectable Threshold Method for caries diagnosis (DSTM) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:42–51. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro ALS, Vianna MIP, Mendes CMC. Comparison of caries lesion detection methods in epidemiological surveys: CAST. ICDAS and DMF BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:122. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0583-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skeie M, Klock K. Scandinavian systems monitoring the oral health in children and adolescents; an evaluation of their quality and utility in light of modern perspectives of caries management. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seppä L, Hausen H. Frequency of initial caries lesions as predictor of future caries increment in children. Scand J Dent Res. 1988;96:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1988.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SBU. Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering. Karies - diagnostik, riskbedömning och icke-invasiv behandling. En systemisk litteraturöversikt. Stockholm: Elanders Infologistics Väst AB, Mölnlycke; 2007.

- 20.Fejerskov O. Changing paradigms in concepts on dental caries: consequences for oral health care. Caries Res. 2004;38:182–191. doi: 10.1159/000077753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Bernabe E, Pitts N, Zheng S, Gallagher JE. Dental caries thresholds among adolescents in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 2013 at 12, and 15 years: implications for epidemiology and clinical care. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:137. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01507-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isaksson H, Alm A, Koch G, Birkhed D, Wendt LK. Caries prevalence in Swedish 20-year-olds in relation to their previous caries experience. Caries Res. 2013;47:234–242. doi: 10.1159/000346131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uribe SE, Innes N, Maldupa I. The global prevalence of early childhood caries: A systematic review with meta-analysis using the WHO diagnostic criteria. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021. 817–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kale S, Kakodkar P, Shetiya S, Abdulkader R. Prevalence of dental caries among children aged 5–15 years from 9 countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a meta-analysis. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26:726–735. doi: 10.26719/emhj.20.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO. Oral health surveys. Basic methods, 4th edition. Geneva: 1997; Report. 1997.

- 26.Klein H, Palmer C, Knutson J. Studies on dental caries: I. Dental status and dental needs of elementary school children. Pub Health Rep. 1938;53:751–765. doi: 10.2307/4582532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGrady MG, Ellwood RP, Maguire A, Goodwin M, Boothman N, Pretty IA. The association between social deprivation and the prevalence and severity of dental caries and fluorosis in populations with and without water fluoridation. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whelton H, Crowley E, O’Mullane D, Donaldson MC, Kelleher V. Dental caries and enamel fluorosis among the fluoridated population in the Republic of Ireland and non fluoridated population in Northern Ireland in 2002. Community Dent Health. 2006;23:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machiulskiene V, Baelum V, Fejerskov O, Nyvad B. Prevalence and extent of dental caries, dental fluorosis, and developmental enamel defects in Lithuanian teenage populations with different fluoride exposures. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:154–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-06.

- 32.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72:39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter JP, Saratzis A, Sutton AJ, Boucher RH, Sayers RD, Bown MJ. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Bernabe E, Pitts N, Zheng S, Gallagher JE. Dental Caries Clusters among adolescents in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland in 2013: implications for proportionate universalism. Caries Res. 2021;55:563–576. doi: 10.1159/000518964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vernazza CR, Rolland SL, Chadwick B, Pitts N. Caries experience, the caries burden and associated factors in children in England, Wales and Northern Ireland 2013. Br Dent J. 2016;221:315–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almerich-Torres T, Montiel-Company JM, Bellot-Arcis C, Almerich-Silla JM. Relationship between caries, body mass index and social class in Spanish children. Gac Sanit. 2017;31:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almerich-Silla JM, Boronat-Ferrer T, Montiel-Company JM, Iranzo-Cortes JE. Caries prevalence in children from Valencia (Spain) using ICDAS II criteria, 2010. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19:e574–e580. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almerich-Torres T, Montiel-Company JM, Bellot-Arcis C, Iranzo-Cortes JE, Ortola-Siscar JC, Almerich-Silla JM. Caries prevalence evolution and risk factors among schoolchildren and adolescents from Valencia (Spain): trends 1998–2018. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6561). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Jacobsen ID, Crossner CG, Eriksen HM, Espelid I, Ullbro C. Need of non-operative caries treatment in 16-year-olds from Northern Norway. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2019;20:73–78. doi: 10.1007/s40368-018-0387-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobsen ID, Eriksen HM, Espelid I, Schmalfuss A, Ullbro C, Crossner CG. Prevalence of dental caries among 16-year-olds in Troms County, Northern Norway. Swed Dent J. 2016;40:191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pitts NB, Ekstrand KR, Foundation I. International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) and its International Caries Classification and Management System (ICCMS) - methods for staging of the caries process and enabling dentists to manage caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:e41–52. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Splieth CH, Santamaria RM, Basner R, Schuler E, Schmoeckel J. 40-Year longitudinal caries development in German adolescents in the light of new caries measures. Caries Res. 2019;53:609–616. doi: 10.1159/000501263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jablonski-Momeni A, Winter J, Petrakakis P, Schmidt-Schafer S. Caries prevalence (ICDAS) in 12-year-olds from low caries prevalence areas and association with independent variables. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014;24:90–97. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calado R, Ferreira CS, Nogueira P, Melo P. Caries prevalence and treatment needs in young people in Portugal: the third national study. Community Dent Health. 2017;34:107–111. doi: 10.1922/CDH_4016Calado05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maldupa I, Sopule A, Uribe SE, Brinkmane A, Senakola E. Caries prevalence and severity for 12-year-old children in Latvia. Int Dent J. 2021;71:214–223. doi: 10.1111/idj.12627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saethre-Sundli HB, Wang NJ, Wigen TI. Do enamel and dentine caries at 5 years of age predict caries development in newly erupted teeth? A prospective longitudinal study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2020;78:509–514. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2020.1739330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agustsdottir H, Gudmundsdottir H, Eggertsson H, Jonsson SH, Gudlaugsson JO, Saemundsson SR, et al. Caries prevalence of permanent teeth: a national survey of children in Iceland using ICDAS. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:299–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karlsson F, Stensson M, Jansson H. Caries incidence and risk assessment during a five-year period in adolescents living in south-eastern Sweden. Int J Dent Hyg. 2020;18:92–98. doi: 10.1111/idh.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baciu D, Danila I, Balcos C, Gallagher JE, Bernabe E. Caries experience among Romanian schoolchildren: prevalence and trends 1992–2011. Community Dent Health. 2015;32:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergström EK, Davidson T, Moberg SU. Cost-Effectiveness through the dental-health FRAMM guideline for caries prevention among 12- to 15-year-olds in Sweden. Caries Res. 2019;53:339–346. doi: 10.1159/000495360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koch G, Helkimo AN, Ullbro C. Caries prevalence and distribution in individuals aged 3–20 years in Jonkoping, Sweden: trends over 40 years. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2017;18:363–370. doi: 10.1007/s40368-017-0305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hugoson A, Koch G, Helkimo AN, Lundin SA. Caries prevalence and distribution in individuals aged 3–20 years in Jonkoping, Sweden, over a 30-year period (1973–2003) Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alm A, Wendt L, Koch G, Birkhed D. Prevalence of approximal caries in posterior teeth in 15-year-old-Swedish teenagers in relation to their caries experience at 3 years of age. Caries Res. 2007;41:392–398. doi: 10.1159/000104798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diamanti I, Berdouses ED, Kavvadia K, Arapostathis KN, Reppa C, Sifakaki M, et al. Caries prevalence and caries experience (ICDAS II criteria) of 5-, 12- and 15-year-old Greek children in relation to socio-demographic risk indicators. Trends at the national level in a period of a decade. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021;22:619–631. doi: 10.1007/s40368-020-00599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bratthall D. Introducing the Significant Caries Index together with a proposal for a new global oral health goal for 12-year-olds. Int Dent J. 2000;50:378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2000.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.David J, Raadal M, Wang NJ, Strand GV. Caries increment and prediction from 12 to 18 years of age: a follow-up study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2006;7:31–37. doi: 10.1007/BF03320812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Campus G, Cocco F, Strohmenger L, Cagetti MG. Caries severity and socioeconomic inequalities in a nationwide setting: data from the Italian National pathfinder in 12-years children. Sci Rep. 2020;10:15622. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72403-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ziller S, Eaton KE, Widstrom E. The healthcare system and the provision of oral healthcare in European Union member states. Part 1: Germany. Br Dent J. 2015;218:239–244. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palvarinne R, Birkhed D, Widstrom E. The public dental service in Sweden: an interview study of Chief Dental Officers. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2018;8:205–211. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_95_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bindi M, Paganelli C, Eaton KA, Widstrom E. The healthcare system and the provision of oral healthcare in European Union member states. Part 8: Italy. Br Dent J. 2017;222:809–817. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pitts NB, Carter NL, Tsakos G. The Brussels statement on the future needs for caries epidemiology and surveillance in Europe. Community Dent Health. 2018;35:66. doi: 10.1922/CDH_PittsBrussels01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alves L, Susin C, Dame-Teixeira N, Maltz M. Impact of different detection criteria on caries estimates and risk assessment. Int Dent J. 2018;68:144–151. doi: 10.1111/idj.12352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ismail A. Diagnostic levels in dental public health planning. Caries Res. 2004;38:199–203. doi: 10.1159/000077755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fletcher J. What is heterogeneity and is it important? BMJ. 2007;334:94–96. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39057.406644.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mejàre I, Kidd E. Radiography for caries diagnosis. In: Fejerskov O, Kidd E, editors. Dental caries. The disease and its clinical management. London: Blackwell. Munksgaard; 2008. p. 69–88.

- 69.Batchelor PA, Sheiham A. Grouping of tooth surfaces by susceptibility to caries: a study in 5–16 year-old children. BMC Oral Health. 2004;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Innes NPT, Chu CH, Fontana M, Lo ECM, Thomson WM, Uribe S, et al. A century of change towards prevention and minimal intervention in cariology. J Dent Res. 2019;98:611–617. doi: 10.1177/0022034519837252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Amarante E, Raadal M, Espelid I. Impact of diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of dental caries in Norwegian children aged 5, 12 and 18 years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Socialstyrelsen: Socialstyrelsens almänna råd om diagnostik, registrering och behandling av karies. Stockholm: SOSFS: 1988.

- 73.Koch G. Effect of sodium fluoride in dentifrice and mouth wash on incidence of dental caries in schoolchildren. Odontol Rev. 1967;18(Suppl):12. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jacobsson B, Koch G, Magnusson T, Hugoson A. Oral health in young individuals with foreign and Swedish backgrounds–a ten-year perspective. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2011;12:151–158. doi: 10.1007/BF03262797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, Ekstrand K, Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17030. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deery C, Care R, Chesters R, Huntington E, Stelmachonoka S, Gudkina Y. Prevalence of dental caries in Latvian 11- to 15-year-Old children and the enhanced diagnostic yield of temporary tooth separation, FOTI and electronic caries measurement. Caries Res. 2000;34:2–7. doi: 10.1159/000016563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deery C, Fyffe HE, Nugent Z, Nuttall NM, Pitts NB. The effect of placing a clear pit and fissure sealant on the validity and reproducibility of occlusal caries diagnosis. Caries Res. 1995;29:377–381. doi: 10.1159/000262096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ismail AI, Sohn W, Tellez M, Amaya A, Sen A, Hasson H, et al. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS): an integrated system for measuring dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sköld U, Birkhed D, Borg E, Petersson L. Approximal caries development in adolescents with low to moderate caries risk after different 3-year school-based supervised fluoride mouth rinsing programmes. Caries Res. 2005;39:529–535. doi: 10.1159/000088191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gröndahl HG, Hollender L, Malmkrona E, Sundquist B. Dental caries and restorations in teenagers. I. Index and score system for radiographic studies of proximal surfaces. Swed Dent J. 1977;1:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jacobsson B, Wendt LK, Johansson I. Dental caries and caries associated factors in Swedish 15-year-olds in relation to immigrant background. Swed Dent J. 2005;29:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lith A, Lindstrand C, Gröndahl HG. Caries development in a young population managed by a restrictive attitude to radiography and operative intervention: II. A study at the surface level. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:232–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gustafsson A, Svenson B, Edblad E, Jansson L. Progression rate of approximal carious lesions in Swedish teenagers and the correlation between caries experience and radiographic behaviour. An analysis of the survival rate of approximal caries lesions. Acta Odontol Scand. 2000;58:195–200. doi: 10.1080/000163500750051737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Poorterman JH, Aartman IH, Kieft JA, Kalsbeek H. Approximal caries increment: a three-year longitudinal radiographic study. Int Dent J. 2003;53:269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2003.tb00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Poorterman J. On quality pf dental care. The development, validation and standardization of an index for assessment of restorative care. Thesis. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam; 1997.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Seach strategy in four electronic databases; Medline Ovid, Embase, CINAHL, Sewed+ (Sept 20th 2021).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].