Abstract

Background and Objectives

The aim of this study was to further understanding of the relationship between social support, internalized and perceived stigma, and mental health among women who experienced sexual violence in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Methods

Drawing from baseline survey data collected in eastern DRC, researchers conducted a secondary cross-sectional analysis using data from 744 participants. Regression and moderation analyses were conducted to examine associations between social support variables, felt stigma, and depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Results

Emotional support seeking and felt stigma were positively associated with increased symptom severity across all three mental health variables. Stigma modified associations between emotional support seeking and depression (t = −2.49, p = .013), anxiety (t = −3.08, p = .002), and PTSD (t = −2.94, p = .003). Increased frequency of emotional support seeking was associated with higher mental health symptoms of anxiety and PTSD among women experiencing all levels of stigma.

Conclusions

Enhancing understanding of social support and stigma may inform research and intervention among Congolese forced migrant populations across circumstances and geographic locations. Implications for practice and research are discussed.

Keywords: social support, stigma, mental health, refugees, displaced populations

Introduction

The second largest country in Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is as rich and diverse in history, culture, and natural resources as it is vast in size. Fueled by a violent colonial legacy, the DRC has endured armed conflict, political and economic strife, and mass population displacement since 1996. Millions have been forcibly displaced, fleeing abuses of the Congolese army and myriad militias seeking to gain economic, political, and military control. By 2016, 1.8 million Congolese were estimated to be internally displaced and approximately 450,000 additional Congolese were registered as refugees in neighboring countries throughout the region (UNHCR, 2017).

In conjunction with other acts of violence involving torture, looting, and forced recruitment, armed groups operating in eastern DRC have perpetrated sexual violence against civilians, targeting women and girls in particular. The health consequences of sexualized violence in conflict-affected areas such as eastern DRC can be debilitating and life-limiting (Stark & Wessells, 2012; Kinyanda et al., 2010). Though psychosocial consequences may be less visible, research in eastern DRC demonstrates that they are no less profound or far-reaching. Survivors of sexual violence in DRC have described psychological symptoms consistent with depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), impaired social functioning, feelings of abandonment and rejection by family and friends, concerns about providing for self and family, fear, and stigma (Bartels et al., 2010; Bass et al., 2013; Kelly et al., 2011).

A nascent but growing body of empirical work related to sexual violence and stigma in eastern DRC can serve to inform efforts to improve women’s health and psychosocial outcomes in the DRC, and deserves ongoing consideration in global contexts as populations displaced by war cross international borders. Thus, this study examines how social support, stigma and mental health interrelate among women who have experienced sexual violence, employing data collected in eastern DRC to inform future directions for practice and research.

Social Support

While scholars have long explored the benefits of social relationships, the concept of social support formally emerged in the 1970s and has since been studied as a determinant of physical and mental health across disciplines and populations (Barrera, 1986; Carlsson, Mortensen, & Kastrup, 2006; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Schweitzer et al., 2006; Uchino, 2009; Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003). By definition, social support is widely recognized as an essential function and product of social relationships. The degree to which social relationships are supportive relies on conditions such as reciprocity, accessibility and reliability, and individuals’ use of their relationships to request, access and/or provide support to others (Williams, Barclay & Schmied, 2004). Perceptions of available support, actual support received, seeking support, and network characteristics are distinct constructs related to the study of social support and are important to differentiate (Lakey & Cohen, 2000), as well as the adequacy and directionality of support (Gottlieb & Bergen, 2010). Conceptualizations of social support in research have typically employed deductive approaches that do not sufficiently address whether models of support reflect participants’ understanding of social support within specific contexts (Williams, Barclay & Schmied, 2004).

Despite the breadth of the social support literature across disciplines, considerable variation persists in how social support is categorized into types of behaviors and operationalized for the purposes of research. Categorizations often include: emotional support, which describes expressions of empathy, love, attachment, trust and caring; instrumental, material or practical support that involves concrete assistance or help in sharing goods, money, skills, labor or time; informational support, which encapsulates advice, guidance, suggestions and information; and, appraisal support that involves feedback or information useful for evaluating oneself or situation (Gottlieb & Bergen, 2010; Williams, Barclay & Schmied, 2004).

Theoretical perspectives from the fields of psychology and sociology offer explanations for the role of social support in physical and mental health, most commonly buffering and main-effect models of social support. The buffering model of social support posits that perceived social support moderates stress and promotes coping and adaptation in times of stress (Barrera, 1986; Cobb, 1976; Cohen & Wills, 1985). In this model, the correlation between life stress and poor mental health is stronger for people with low social support than for people with high social support. In contrast, the main effect model maintains that social support has continuous and direct benefits to well-being by addressing basic but constant social needs of individuals, not only in times of stress (Thoits, 1985). The main effect theory of social support is appropriate for the current study given the ongoing exposure to violence experienced within the community that renders stress a chronic condition, not a discrete event.

The link between social support and mental health may be related to identity and social roles that provide predictability, stability, self-worth, and a sense of belonging (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Thoits, 1985). Studies demonstrate the positive role of support for refugees provided by family and friends in buffering different types of distress and particularly the role of perceived social support from migrants’ ethnic communities in predicting mental health outcomes (Schweitzer et al., 2006; Simich, Beiser & Mawani, 2003). A lack of meaningful supportive relationships has been linked to social isolation, stress, and mental and physical health problems among refugee groups (Simich, Beiser & Mawani, 2003; Chen, Hall, Ling & Renhazo, in press). Social support has also been shown to be an important element of women’s recovery from sexual assault (Bryant-Davis, Ullman, Tsong, & Gobin, 2011; Coker et al., 2002; Fowler & Hill, 2004; Schummn, Briggs-Phillips & Hobfoll, 2006). Research has shown the absence of social support as a strong predictor of PTSD (Veling, Hall, & Joosse, 2013; Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000), and the presence of social support as a protective factor against PTSD and other mental health problems among survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence across contexts (Coker et al., 2002; Schumm, Briggs-Phillips & Hobfoll, 2006). Negative reactions are common to disclosures of sexual assault and additional research is required to understand the extent to which survivors’ post assault interactions impact their mental health (Ullman, Townsend, Filipas, Starzynski, 2007).

Stigma

Much of the existing stigma research has been informed by Erving Goffman’s work in sociology (1963) and cross-disciplinary research in relation to mental illness, sexual orientation, HIV/AIDS, and race/ethnicity since 2000. Stigma is currently understood as “marks of shame or oppression,” “discrediting attributes” and a “devalued social identity,” and stigmatization as “the social process embedded in social relationships that devalues through conferring labels and stereotyping” (Pescosolido & Martin, 2015, p. 92). Stigma and stigmatization are dependent on interconnected processes that co-occur within a context of power dynamics that involve: identifying and labeling human differences; linking labeled persons to undesirable characteristics (stereotyping); socially distancing or othering the stigmatized group; and the experience of discrimination and loss of status by stigmatized individuals and groups (Link & Phelan, 2006). The constructs of internalized, perceived and enacted stigma have commonly been used in stigma research associated with mental illness, in particular (Brohan, Slade, Clement & Thornicroft, 2010). Internalized stigma relates to an individual’s feelings (i.e. shame, self-blame, guilt) or behaviors in response to negative perceptions, exacerbating feelings of difference (Simbayi et al., 2007). Perceived stigma refers to how an individual perceive how others negatively view or behave toward them (Liu et al., 2011), and enacted stigma is operationalized by actual acts of discrimination people experience (Lasalvia et al., 2013).

Women and girls marked as “raped” in the DRC are at increased risk of being ostracized, humiliated, blamed, and possibly turned out from their homes and abandoned (Bartels et al., 2010). Female survivors may also experience isolation, strained marital relations, exclusion from school and work, being labeled unfit for marriage and re-victimization (Josse, 2010; Kelly, Betancourt, Mukwege, Lipton, & VanRooyen, 2011; Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, 2009). Survivors may attempt to hide the fact they were raped, severely restricting the help and assistance available to them. A secondary data analysis of 1,021 patient files of women who presented post-rape to a hospital in eastern DRC revealed that women reporting multiple perpetrators were 2.8 times more likely to be abandoned by their husbands, and women who became pregnant as a result of rape were 2.6 times more likely to be abandoned by their husbands (Bartels et al., 2013).

In eastern DRC, family and/or community members commonly describe women’s experiences with discrimination associated with rape as “rejection”. Women have described experiencing varying and multiple rejections, including financial, emotional and physical. Kohli et al.’s qualitative study (2013) points to the complexity of rejection: some women may no longer live with their families; others may experience misunderstandings and tensions among family members that did not exist before; some may be unable to continue with their household responsibilities; some experience a loss of affection; other women described rejection as a loss of economic support, and some continue to live in the same household but no longer received financial support from their husbands for themselves or their children (Kohli et al., 2013, p. 753–754). While survivors in eastern DRC described rejection by one or more people in the family (e.g., in-laws, spouse, parents, children), they also pointed to how other family members provided support and helped with mending ruptured connections (Kohli et al., 2013).

Study aims

This study examined how social support, mental health and stigma interact among women who have experienced sexual violence in the Kivu Provinces of eastern DRC. Situated within the main effects theory of social support, the research questions guiding the current analysis are: 1) what is the direct relationship between social support and mental health among women who reported experiencing sexual violence in eastern DRC; and, 2) how does the internalization and perception of stigma moderate the relationship between social support variables and mental health outcomes? In relation to the first question we hypothesized that women reporting difficulty accessing social support across a variety of variables would be associated with higher levels of mental health symptoms. Our second hypothesis was that internalized and perceived stigma would change the relationship between social support and mental health, whereby social support would be associated with poorer mental health.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of cross-sectional data originally collected during two randomized controlled trials conducted in eastern DRC. Led by a research team from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the International Rescue Committee, the two trials tested the effectiveness of group psychotherapy therapy (study one) and a social-economic intervention (study two) on improving mental health and economic outcomes for women who had experienced sexual violence (Bass et al., 2013; Bass et al., 2016). The fact that both studies were conducted in the same region of DRC (in different villages), were concerned with the same population of women, employed similar recruitment approaches, and used the same measurement instruments allowed us to combine the two samples for the purposes of this analysis. Institutional review boards at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Kinshasa School of Public Health in the DRC approved the original studies.

Recruitment

The original researchers used nonprobability purposive sampling techniques to recruit participants in 15 rural communities for study one and nine rural communities for study two. Local organizations providing services and programs in response to sexual violence invited women in their communities who had previously self-reported significant and persistent problems with daily functioning and/or mental health symptoms to voluntarily participate in a study. As described in the parent studies (Bass et al., 2013; Bass et al., 2016), 1,184 adult women participated in interviews as part of a baseline assessment to determine eligibility for two randomized controlled trials. Given the current focus on the stigma associated with sexual violence, 440 cases of women who reported witnessing but not directly experiencing sexual violence were removed from the dataset resulting in a sample of 744 women who reported experiencing sexual violence for the current analysis.

Data collection procedures

Baseline data collection was conducted using the same instrument and techniques across the two trials. The survey instrument was verbally administered in five languages (Kibembe, Kifuliro, Kihavu, Mashi, and Swahili) by trained female interviewers with women who provided informed consent to participate. Baseline data were collected in December 2010 for study one and in February 2011 for study two.

Measures

Demographics.

Participants reported age, ethnicity, marital status, years of education completed (log transformed variable), number of women and total number of people living in the home, and number of children for whom they were responsible.

Mental health (dependent variables).

The original researchers conducted qualitative research in three linguistically diverse communities to inform the selection and modification of existing mental health measures (Bass et al., 2013). They used the 15-item subscale of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) to assess depression, the 10-item HSCL-25 anxiety subscale to measure anxiety (Winokur, Winokur, Rickels & Cox, 1984) and the 16-item Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ-Trauma) to assess PTSD (Mollica, Caspi-Yavin, Bollini, Truong, Tor & Lavelle, 1992). For the purposes of this secondary analysis, we removed a single item from the depression subscale (“feelings of worthlessness”) and one item (“feeling detached or withdrawn”) from the PTSD subscale due to their inclusion on the felt stigma scale described next. The Cronbach alpha scores indicated good internal consistency. For the depression subscale the Cronbach alpha was .85 before and after removing the one item; .88 for the anxiety subscale; and .89 for the trauma measure prior to removing the one item and .88 after it was removed. For each symptom, interviewers asked participants to rate how often they perceived that they experienced the problem in the prior four weeks on a four-point, pictorial Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = little bit, 2 = moderate amount, 3 = a lot). Mean scores were calculated with higher scores indicating greater number and/or frequency of symptoms.

Felt stigma (moderator).

The aforementioned qualitative research identified locally specific psychosocial problems associated with sexual violence. Researchers drew from this group of items, as well as upon additional items from the depression and PTSD measures, to develop an empirically-driven and context specific felt stigma scale, using factor analysis methods (Murray et al., 2018a). This previous analysis supported combining internalized and perceived stigma into a single construct of felt stigma. Felt stigma refers to people’s actual and anticipated fear of being discriminated against, perceptions of others’ negative views of oneself, and feelings of shame (Jacoby, 1994; Scambler & Hopkins, 1986). The eight-item felt stigma scale indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = .86). Items included: feeling badly treated by family members, feeling badly treated by community members, feeling rejected by everybody, feeling stigma, wanting to avoid people or hide, feeling shame, feeling detached from others (HTQ-Trauma), feelings of worthlessness (HSCL-25, depression subscale). For each symptom, participants were asked to rate how often they perceived that they experienced the problem in the prior four weeks (0 = not at all, 1 = little bit, 2 = moderate amount, 3 = a lot). A higher score indicated a higher number and/or frequency of feelings associated with perceived and internalized stigma.

Social support variables (independent variables).

Table 1 provides details on the seven social support measures we developed for the purposes of this analysis: emotional support seeking (two items); contact with others (six items); practical support (one item); anticipated short-term financial support (one item); anticipated long-term unspecified support (one item); support provided to others (four items); and asking for help (one item). The emotional support seeking measure was developed from questions included in the survey instrument on coping and service usage. The items used to assess contact with others, support provided to others, and asking for help came from a context-specific function scale developed as part of the same qualitative research on psychosocial problems indicated above (Bass et al., 2013). The single items assessing practical long- and short-term anticipated support were adapted from the Integrated Questionnaire for the Measurement of Social Capital (SC-IQ) (Grootaert Narayan, Woolcock, Nyhan-Jones, 2004) and log transformed due to non-normal distributions. For the four multi-item measures, items were averaged across participants and exhibited adequate to good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha range 0.64–0.85).

Table 1 –

Social support measurement details

| Social support construct | Measure | Items | Response options | Cronbach Alpha | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional support | Emotional support seeking | When you feel bad, how often do you talk about your problems with (1)friends or family members (2)other women who have experienced similar traumas |

0 = not at all 1 = rarely 2 = sometimes 3 = often |

0.64 | Higher score indicates more frequent support seeking |

| Contact with kin and non-kin | Contact with others | How much difficulty have you had in the past 4 weeks (1) Socializing with others in the community (2) Taking part in community activities or events (3) Taking part in family activities or events (4) Exchanging ideas with others (5) Interacting or dealing with people you do not know? (6) Attending church or mosque as usual? |

0 = none 1 = little 2 = moderate amount 3 = a lot 4 = often cannot do |

0.85 | Higher score indicates more difficulty in interacting with others |

| Received practical support | Practical support | How often do you receive practical help from your family, like help when you are sick, child care when you are away, or help with garden work? | 0 = not at all 1 = rarely 2 = sometimes 3 = often |

- | Higher score indicates more frequent support |

| Perceived practical support | Anticipated short-term financial support | How many people you could turn to that would be willing to provide you a small amount of money you suddenly needed (for example enough to pay for your household for one week)? | Number of people | - | Higher number indicates the more number of people they could anticipate support from. |

| Anticipated long-term unspecified support | How many people you could turn to who would be willing to assist you if you suddenly faced a long-term emergency, such as a family death or harvest failure? | Number of people | - | ||

| Support provided to others (practical, informational/emotional) | Support provided to others | How much difficulty have you had in the past 4 weeks (1) Uniting with other community members to do tasks for the community (2) Uniting with other family members to do tasks for the family (3) Giving advice to family members (4) Giving advice to other community members |

0 = none 1 = little 2 = moderate amount 3 = a lot 4 = often cannot do |

0.81 | A higher average indicates more difficulty in supporting others |

| Asking for help | Asking for help | How much difficulty have you had in the past 4 weeks asking or getting help from people or an organization? | 0 = none 1 = little 2 = moderate amount 3 = a lot 4 = often cannot do |

- | A higher average indicates more difficulty in asking for help |

Data analysis

We examined univariate distributions to identify any possible issues with erroneous values, outliers, normality, and missing data. We assessed percent missing per variable, correlated missingness, patterns of missingness, and Little’s omnibus test of missingness. Four variables had missingness in excess of 5%: contact with others (6.5%); practical support (32.9%); support provided to others (7.8%); and, asking for help (8.2%). We excluded practical support from the analysis moving forward, and assessed using sensitivity analyses that missingness on the three other variables did not affect the results.

We examined bivariate relationships between independent and dependent variables using Pearson’s correlations and one-way ANOVA analyses. Variables exhibiting a significant association to either independent or dependent variable were included in the regression model. We conducted complete case regression analyses based on 624 cases. Subsequently, we ran simultaneous entry regressions on each outcome variable to assess regression assumptions and normality of residuals. Multicollinearity was not detected across all three regression models (VIF statistic <10). When statistical assumptions were not met, these violations were addressed in the final moderation model by using version 2.15 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS module (Hayes, 2013).

Based on independent and significant associations with mental health variables found in the regression analyses we selected emotional support seeking to examine the interaction between social support and stigma in the final moderation models for the following outcomes: (1) depression, (2) anxiety, and (3) PTSD. Covariates included three remaining social support measures (contact with others, anticipated long term support, asking for help) that indicated a significant association with any of the mental health outcomes in regression analyses. Felt stigma and emotional support seeking were mean-centered. In the event of a significant moderation effect, we probed the interaction by testing the simple slope at low and high levels of felt stigma and emotional support seeking (Aiken & West, 1991), defined as one standard deviation (SD) below and above the mean. We conducted complete case moderation analyses based on data from 674 participants. All analyses with SPSS version 23 and all analyses were conducted with alpha = 0.05.

Results

Univariate analyses

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the study population. The women included in the current analysis had an average age of 37 years (range: 18 −80) and completed an average of two years of formal education (range: 0 – 12). Nearly half were married (47%) and 22.4% were divorced or separated from their spouse. Participants were responsible for an average of four children. Twenty-one percent of women (n=156) reported giving birth to a child as a result of sexual violence. Approximately three quarters of women reported having received some sort of post-rape medical attention.

Table 2 –

Participant characteristics (N=744)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Demographics | |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 69 (9.3) |

| Married | 353 (47.4) |

| Divorced | 18 (2.4) |

| Separated | 134 (18) |

| Widowed | 170 (22.8) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Mushi | 307 (41.3) |

| Mufuliru | 155 (20.8) |

| Muhavu | 121 (16.3) |

| Mubembe | 51 (6.9) |

| Other | 110 (14.78) |

| Post sexual violence (SV) events | |

| Received medical attention | 559 (75.1) |

| Told someone about it | 536 (72) |

| Had a child as a result of SV | 156 (21) |

|

| |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Demographics | |

| Age | 37 (13.16) |

| Completed years of education | 2.03 (3.03) |

| Number of people living in the home | 7.13 (3.11) |

| Number of children responsible for | 4.14 (2.60) |

| Mental health | |

| Average depression score | 1.95 (0.58) |

| Average anxiety score | 2.14 (0.67) |

| Average PTSD score | 1.92 (0.65) |

| Moderator variable | |

| Felt stigma | 1.75 (0.80) |

| Social support variables | |

| Contact with others | 1.43 (1.02) |

| Emotional support seeking | 1.33 (0.88) |

| Practical support received | 2.07 (0.98)* |

| Anticipated short-term financial support | 1.28 (1.92) |

| Anticipated long-term unspecified support | 2.22 (4.72) |

| Support provided to others | 1.70 (1.10) |

| Asking for help | 2.0 (1.35) |

32.9% missing data, therefore this variable was not included subsequent analysis

Regression analyses

Results from the forced entry regression analyses assessing the relationship of stigma and social support variables with different mental health outcomes are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 –

Regression analyses predicting mental health outcomes (N=624)

| Depression | Anxiety | PTSD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (CI) | SE B | β | p | b (CI) | SE B | β | p | b (CI) | SE B | β | p | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Constant | .94 (.82, 1.05) | .06 | .000 | 1.04 (.88, 1.20) | .08 | .000 | .77 (.65, .90) | .06 | .000 | |||

| Felt stigma | .40 (.35, .45) | .03 | .55 | .000 | .44 (.37, .50) | .04 | .52 | .000 | .45 (.40, .51) | .03 | .56 | .000 |

| Emotional support seeking | .08 (.05, .12) | .02 | .13 | .000 | .17 (.12, .22) | .03 | .23 | .000 | .13 (.09, .17) | .02 | .20 | .000 |

| Contact with others | .04 (−.01, .01) | .03 | .08 | .118 | .01 (−.07, .08) | .04 | .01 | .886 | .07 (.01, .13) | .03 | .11 | .022 |

| Anticipated short-term financial support* | −.1 (−.08, .06) | .04 | −.01 | .777 | .03 (−.07, .12) | .05 | .03 | .543 | .04 (−.32, .12) | .04 | .05 | .254 |

| Anticipated long-term unspecified support* | −.04 (−.94, .02) | .03 | −.05 | .244 | −.04 (−.12, .04) | .04 | −.04 | .354 | −.08 (−.14, −.2) | .03 | −.10 | .014 |

| Support provided to others | .01 (−.04, .06) | .03 | .01 | .801 | .01 (−.06, .07) | .03 | .02 | .787 | .04 (−.02, .09) | .03 | .06 | .179 |

| Asking for help | .07 (.04, .09) | .02 | .15 | .000 | .02 (−.02, .06) | .02 | .04 | .265 | .02 (−.01, .05) | .02 | .04 | .250 |

| R 2 | .49 | .000 | .33 | .000 | .51 | .000 | ||||||

logtransformed variables

(CI – Confidence Interval)

Depression.

A significant regression equation was found [R2 = .49, F (7, 617) = 84.42, p < .001] in the model with depression as the outcome. Felt stigma (b = .40, p < .001), frequency of emotional support seeking (b = .08, p < .001), and asking for help (b = .07, p < .001) were positively associated with more depression symptomology.

Anxiety.

For the regression analysis with anxiety as the dependent variable [R2 = .33, F (7, 617) = 43.59, p < .001], felt stigma (b = .44, p = .000) and frequency of emotional support seeking (b = .17, p < .001) were also significantly associated with increased symptom severity.

PTSD.

Results of the PTSD regression model were also significant [R2 = .51, F (7, 617) = 91.94, p < .001] with felt stigma (b = .45, p < .001), frequency of emotional support seeking (b = .13, p < .001), contact with others (b = .07, p = .022) positively associated with increased levels of PTSD. Long-term anticipated support (b = −.08, p = .014) had a negative association with PTSD, indicating that more long-term anticipated support was associated with fewer PTSD symptoms.

Moderation analyses

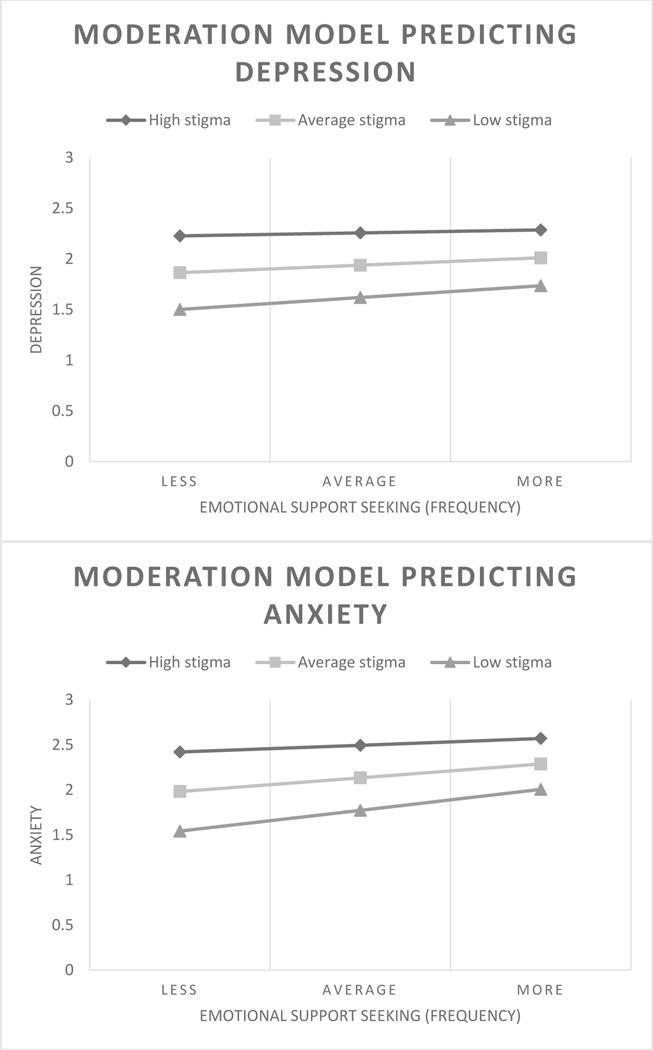

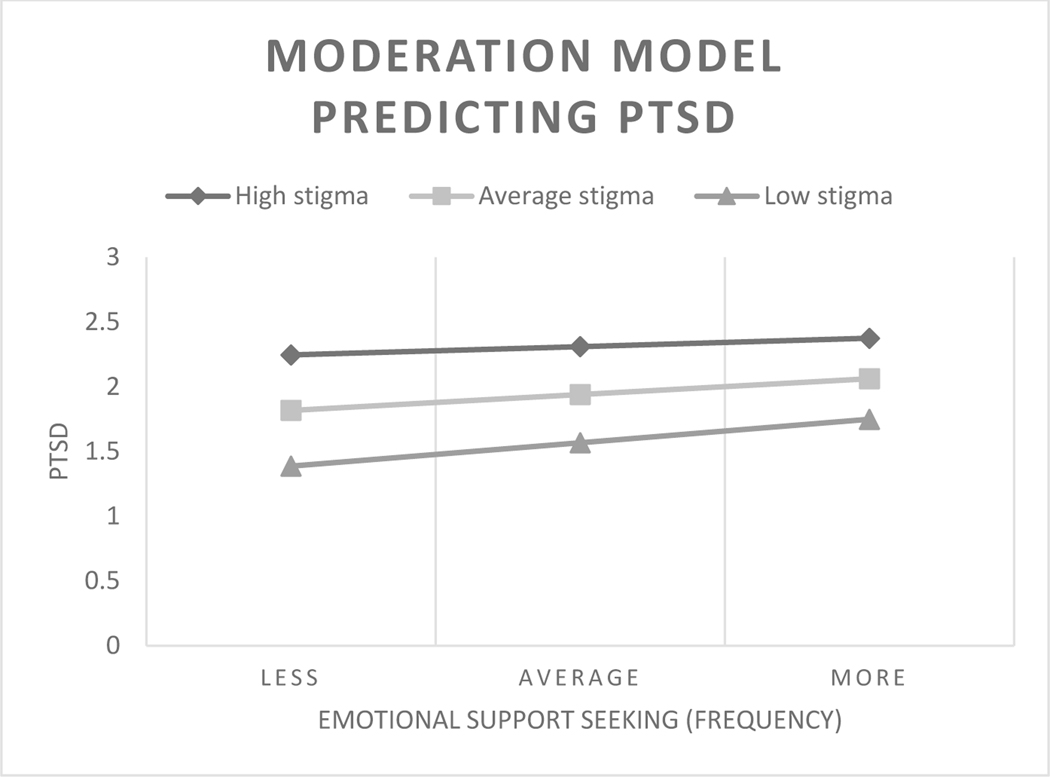

Detailed results from the moderation analyses are presented in Table 4 and depicted in graph form in Figure 1.

Table 4 –

Moderation models predicting mental health outcomes (N=674)

| Depression | Anxiety | PTSD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (CI) | SE Β | t | p | b (CI) | SE Β | t | P | b (CI) | SE B | t | p | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Constant | 1.78 (1.70, 1.86) | .04 | 42.38 | .000 | 2.08 (1.98, 2.19) | .05 | 39.50 | .000 | 1.79 (1.70, 1.88) | .05 | 39.83 | .000 |

| Felt stigma (centered) | .40 (.35, .46) | .03 | 14.91 | .000 | .45 (.39, .52) | .04 | 13.05 | .000 | .47 (.41, .52) | .03 | 17.08 | .000 |

| Emotional support seeking (centered) | .08 (.05, .12) | .02 | 4.66 | .000 | .18 (.13, .22) | .03 | 7.12 | .000 | .14 (.10, .18) | .02 | 6.85 | .000 |

| Emotional support seeking X Felt stigma | −.06 (−.11, −.13) | .03 | −2.49 | .013 | −.11 (−.19, −.04) | .04 | −3.08 | .002 | −.08 (−.14, −.03) | .03 | −2.94 | .003 |

| Covariates | W | |||||||||||

| Contact with others | .05 (.01, .08) | .02 | 2.70 | .007 | .01 (−.04, .07) | .03 | .56 | .60 | .09 (.05, .13) | .02 | 4.31 | .000 |

| Anticipated long-term unspecified support* | −.04 (−.08, .00) | .02 | −1.76 | .079 | −.00 (−.06, .06) | .03 | −.07 | .95 | −.04 (−.08, .01) | .02 | −1.49 | .136 |

| Asking for help | .06 (.03, .09) | .01 | 4.34 | .000 | .02 (−.02, .05) | .02 | .88 | .38 | .02 (−.01, .05) | .02 | 1.23 | .218 |

| R 2 | .50 | .000 | .36 | .000 | .53 | .000 | ||||||

logtransformed variable

Figure 1.

Moderation models predicting mental health outcomes. Fitted values from regression models were 1 SD below the mean (less or low), mean (average), 1 SD above the mean (more or high) for emotional support seeking and stigma, respectively.

Depression.

The interaction term between emotional support seeking and felt stigma accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in depression (Δ = .01, F(1, 667) = 6.20, p = .01). Significant conditional effects existed between emotional support seeking and depression at low (t = 4.41, p < .001) and average levels of stigma (t = 4.66, p < .001), and frequency of emotional support seeking predicted higher depression scores (see Figure 1). The conditional effect for depression became non-significant among women reporting high levels of felt stigma (t = 1.44, p = .151). For this group, depression scores remained the highest and were relatively constant across stigma levels. Two social support covariates included in the moderation model were associated with significantly higher depression: contact with others (b = .05, SE = .02, p = .007) and asking for help (b = .06, SE = .01, p < .001), the latter of which was also associated with depression in the regression analysis.

Anxiety.

The interaction term between emotional support seeking and felt stigma accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in anxiety (Δ = .02, F(1, 667) = 9.47, p = .002). Significant findings indicated that among women with low (t = 6.29, p < .001), average (t = 7.12, p < .001) or high (t = 2.56, p = .011) felt stigma scores, seeking less, average and more frequent emotional support seeking predicted increased anxiety scores (see Figure 1). Similar to the regression model, no associations were found between social support covariates and anxiety.

PTSD.

The interaction term between emotional support seeking and felt stigma accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in PTSD (Δ = .01, F(1, 667) = 8.66, p = .003). Whether felt stigma was low (t = 6.32, p < .001), average (t = 6.85, p < .001), or high (t = 2.62, p = .009), we found a significant positive relationship between emotional support seeking and PTSD (see Figure 1), signifying that seeking emotional predicted increased symptoms associated with PTSD for women regardless of their level of felt stigma. Consistent with the regression model, the covariate contact with others was again associated with PTSD scores (b = .09, SE = .02, p < .001) in the moderation model.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to further understanding of the relationship between social support variables, internalized and perceived stigma (felt stigma), and mental health among women who experienced sexual violence in eastern DRC. We found positive significant main effects of emotional support seeking and felt stigma for depression, anxiety and PTSD. Contrary to our first hypothesis, however, more frequent seeking of emotional support was associated with higher not lower mental health scores. The cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow us to draw conclusions about the direction of the relationship between emotional support seeking and mental health symptoms. Therefore, increased mental health symptoms may predict emotional support seeking and unexpectedly act as an impetus for women to talk more frequently about their problems with friends, family members and/or other women who have experienced similar traumas. As we predicted in our second hypothesis, felt stigma did statistically significantly moderate the relationship between emotional support seeking and the three mental health outcomes. In all three models, higher felt stigma was associated with poorer mental health. Women with low levels of stigma had the lowest levels of depression, anxiety and PTSD as their emotional support seeking increased. As women reported higher levels of stigma, the relationship between emotional support seeking and mental health symptoms weakened such that an increase in emotional support seeking was associated with a smaller increase in mental health symptoms. Though the association was attenuated among women experiencing a higher level of stigma, positive conditional regression coefficients indicated that increased frequency of emotional support seeking was still associated with higher mental health symptoms among women experiencing across levels of stigma, with the exception of depression.

Emotional support seeking is important to understanding women’s social support in relation to mental health and psychosocial wellbeing. Our findings, however, bring into question the role emotional support seeking plays in alleviating mental health symptoms for women who may be experiencing stigma associated with sexual violence as well as mental health problems. Indeed, research pointing to more social support as predictive of increased emotional strain (Johnson & Stoll, 2008; Mendoza, Mordeno, Latkin, & Hall, 2017) speaks to a “dark side” of social capital (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). We would want to know more about the feedback women received as a result of seeking this form of support, positive or negative, and the degree to which those reactions served to reinforce existing or introduce new feelings of stigma (see Ullman, 1999; Ullman, Townsend, Filipas, & Starzynski, 2007).

This study serves to highlight the internalized nature of stigma and the extent to which psychosocial consequences of being raped can also be perpetuated from within. The feelings of stigma reported by women in this study included feeling badly treated by family and community members, feeling rejected by everybody, wanting to avoid people and hide, and feeling shame, worthlessness and detached from others. These feelings and perceptions are especially troubling when we consider socio-cultural contexts such as eastern DRC in which women rely heavily upon social support from extended family and community members. As they reflect fissures in relationships critical to women’s identity, survival, and wellbeing, “reconstituting links to community is critical to healing the injury done by rejection consequent to sexual violation” (Sideris, 2003, p. 722). Byrant-Davis and colleagues (2011) found African American female sexual assault survivors who had more frequent social contact in the last year with others in their current network were less likely to report symptoms of depression and PTSD. These authors situated their findings “within the framework of collectivistic cultural principles that are articulated by the Afrocentric notions of identity being rooted, shaped, and reflected by connection to others” (Nasim, Corona, Belgrave, Utsey, & Fallah, 2007 in Bryant-Davis et al., 2011, p. 1612), and theorize that social connection is instrumental to rectifying the ruptures created by sexual violence. Indeed, PTSD is often connected to broken social bonds due to the nature of the traumatic event, the social consequences of stigmatized reactions, or diminished social networks (Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008).

The study findings point to implications for practice and research in eastern DRC with survivors of sexual violence. Service agencies and practitioners may not readily see the interplay of social support, stigma and mental health. Even as mental health symptoms lessen, and social networks improve with treatment or over time (Bass et al., 2012; Hall et al., 2014), stigma-related feelings may persist. Indeed, in a related study, we saw smaller treatment effects on stigma from a group therapy intervention than mental health outcomes (Murray et al., 2018b). Programs addressing these issues in the DRC that operationalize “rejection” as women physically abandoned and living separate from their families may overlook the less visible psychosocial needs of women struggling with felt stigma who continue to live at home (Kohli et al., 2013, p. 754). It is common for services to focus on the health and well-being of the individual but not on the consequences of sexual violence on the person’s interpersonal relationships, which survivors in the DRC report can be as devastating as the incidents themselves (Albutt, Kelly, Kabanga, & VanRooyen, 2017). Our findings point to the complexity and potential negative effects of discussing stigmatized problems among women’s interpersonal networks, as well as reinforce the importance of availing formal and culturally relevant support options to women. Service providers, including healthcare providers, can help identify violence against women and assist women with developing skills, resources, and support networks (Coker et al., 2002). Charuvastra and Cloitre (2008) posit that the therapeutic relationship reflects commonalities with social support and that it may be helpful to conceptualize the therapeutic process as involving the creation of a social bond. Previous studies indicate that group psychotherapy and cognitive restructuring in particular may improve a range of mental health and social outcomes regardless of the degree to which women who experienced sexual violence perceive, internalize and experience stigma in the DRC (Murray et al., 2018b; Hall et al., 2014).

Though our findings may not generalize to other contexts, our results are useful in suggesting considerations for practice and future research directions with displaced populations. A recent study found that women who reported being rejected in the DRC were twice as likely to experience ongoing displacement and other facets of vulnerability integral to their safety and security (Albutt, Kelly, Kabanga, & VanRooyen, 2017). Women who migrate both within and across the international borders of the DRC may do so with perceptions and internalizations of stigma, which in turn may influence how they forge new connections and the extent to which they access new sources of support moving forward. Agencies providing social services with internally and externally displaced populations may not be aware of the extent to which internalized stigma may compound the vulnerability of and lack of support options available to women affected by sexual violence. Further inquiry is required to understand how stigma may be carried across borders as part of the forced migration experience and how these feelings continue, are exacerbated, or cease to influence the relationship between social support and mental health, and the role of social support in women’s psychosocial wellbeing (Mendoza, Mordeno, Latkin, & Hall, 2017). For women migrating with the children born as a result of their assault(s), these questions become all the more complex. Women raising children from sexual violence-related pregnancies in the DRC report symptoms indicative of mental health disorders that may be addressed through programming that addresses stigma and acceptance (Scott et al., 2015). The growing body of literature on mental health and stigma associated with the experience of sexual violence is instrumental for informing practice, but may not be readily accessed by practitioners working with Congolese women and communities. Efforts to synthesize the literature and translate research into practice would serve the practitioner community working with increasingly diverse communities with complex and nuanced needs.

Limitations

Several limitations of our analysis are important to note. First, cross-sectional analyses do not allow us to draw conclusions about the direction of the relationships under study and the sequence of events among variables are unknown. Second, social support was not a primary outcome of the original research. We therefore examined individual measures relevant to the construct of social support, but we were unable to analyze women’s social support as robustly as we would have liked. Future research might deepen our understanding of social support by utilizing an exploratory mixed methods approach, starting with qualitative research to query context and culturally-specific understandings of social support, which can inform the development and validation of a locally specific social support scale. Third, the original research was not specifically designed to understand and assess stigma and as a result there may be important facets of the stigma experience that may not be reflected in the stigma scale (Murray et al., 2018a). We were also unable to distinguish whether the stigma women reported was specific to their experiences with sexual violence, and/or highly stigmatized mental health symptoms. Finally, while the findings offer important insights into complex processes, sampling procedures used in the original studies limit generalizability of findings to women in eastern DRC, as well as to other contexts.

Conclusion

At the time of writing, the current study is the first we are aware of to explore the modifying role of felt stigma in exacerbating mental health symptoms among women who experienced sexual violence. Our aim in producing this paper was to produce insights into the complexity of women’s experiences with sexual violence, social support, stigma, and mental health, and spark questions for practice with Congolese and other war-affected populations. Our findings indicate that the relationship between emotional support seeking and mental health for women having experienced stigmatized violence is complicated and warrants further understanding. How dynamics examined in this study carry over into women’s experiences with forced migration, over time and in context, is of particular importance moving forward. In addition, further understanding is needed regarding the interaction of a range of traumatic events women experience in war and displacement, and context-specific stigmas associated with the psychosocial and mental health consequences of those experiences.

Acknowledgements

We thank the women who participated in the original research, and whose lives were severely impacted by violent conflict. Many thanks to Dr. Stephanie Rivaux who helped guide the development of the analysis and paper, and Dr. Laurie Cook Heffron who reviewed an early draft.

Funding

The current analysis was made possible by a dissertation fellowship provided to Dr. Wachter by the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health at the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Murray was supported in part by an NIMH T32 Training Grant for Global Mental Health (T32MH103210). The original study was funded the U.S. Agency for International Development Victims of Torture Fund and the World Bank.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Karin Wachter, Arizona State University, 411 N. Central Avenue, Suite 800, Phoenix, AZ 85004-0689; The University of Texas at Austin, Institute on Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault.

Sarah M. Murray, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 N. Broadway, 8th Floor, Baltimore, Maryland, 21205

Brian J. Hall, University of Macau, E21-3040, Avenida da Universidade, Taipa, Macau (SAR), People’s Republic of China, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 21205

Jeannie Annan, The International Rescue Committee, 122 East 42nd Street, New York, New York 10168-1289.

Paul Bolton, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Suite E8132, Baltimore, Maryland 21205.

Judy Bass, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 N. Broadway, Room 861, Baltimore, Maryland 21205.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG, & Reno RR (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. Thousand Oaks: CA. [Google Scholar]

- Albutt K, Kelly J, Kabanga J, & VanRooyen M. (2017). Stigmatisation and rejection of survivors of sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Disasters, 41(2), 211–227. Doi. 10.1111/disa.12202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babalola SO (2014). Dimensions and correlates of negative attitudes toward female survivors of sexual violence in Eastern DRC. Journal of interpersonal violence, 29(9), 1679–1697. Doi: 0886260513511531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M. (1986). Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American journal of community psychology, 14(4), 413–445. Doi: 10.1007/bf00922627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels S, Scott J, Leaning J, Mukwege D, Lipton R, & VanRooyen M. (2013). Surviving sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 11(4), 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bass JK, Annan J, McIvor Murray S, Kaysen D, Griffiths S, Cetinoglu T, Wachter K, Murray LK, Bolton PA (2013). Cognitive Processing Therapy for mental health problems of sexual violence survivors in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: Outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 2182–91. Doi: 10.1037/e533652013-328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J, Murray S, Cole G, Bolton P, Poulton C, Robinette K, Seban J, Falb K, & Annan J. (2016). Economic, social and mental health impacts of an economic intervention for female sexual violence survivors in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Global Mental Health, 3, e19. Doi: 10.1017/gmh.2016.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass JK, Ryder RW, Lammers MC, Mukaba TN, & Bolton PA (2008). Post‐partum depression in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: Validation of a concept using a mixed‐methods cross‐cultural approach. Tropical medicine & international health, 13(12), 1534–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, & Tran N. (2008). Psychological distress and adjustment of Vietnamese refugees in the United States: Association with pre- and postmigration factors. American Journal Of Orthopsychiatry, 78(1), 109–120. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, & Valentine JD (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68(5), 748–766. Doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, & Thornicroft G. (2010). Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice and discrimination: a review of measures. BMC health services research, 10(1), 80. Doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Tsong Y, & Gobin R. (2011). Surviving the storm: The role of social support and religious coping in sexual assault recovery of African American women. Violence Against Women, 17(12), 1601–1618. Doi: 10.1037/e517292011-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson JM, Mortensen EL, & Kastrup M. (2006). Predictors of mental health and quality of life in male tortured refugees. Nordic journal of psychiatry, 60(1), 51–57. Doi: 10.1080/08039480500504982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell K, Blackburn P, & Barker C. (2011). The relationship between trauma, post-migration problems and the psychological well-being of refugees and asylum seekers. International Journal Of Social Psychiatry, 57(2), 107–119. doi: 10.1177/0020764008105699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charuvastra A, & Cloitre M. (2008). Social bonds and posttraumatic stress disorder. Annu. Rev. Psychol, 59, 301–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Hall BJ, Ling L, Renhazo AMN (2017). Pre-migration and post- migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: findings from the first wave of the BNLA cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 4(3), 218–229. Doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(17)30032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38, 300–314. Doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, & Davis KE (2002). Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of women’s health & gender-based medicine, 11(5), 465–476. Doi: 10.1089/15246090260137644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (1988). Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology, 7, 269–297. Doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.7.3.269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin, 98(2), 310. Doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler DN, & Hill HM (2004). Social support and spirituality as culturally relevant factors in coping among African American women survivors of partner abuse. Violence against women, 10(11), 1267–1282. Doi: 10.1177/1077801204269001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gellis ZD (2003). Kin and nonkin social supports in a community sample of Vietnamese immigrants. Social Work, 48(2), 248–258. Doi: 10.1093/sw/48.2.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, & Hill J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel hierarchical models (Vol. 1). New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazinour M, Richter J, & Eisemann M. (2004). Quality of Life Among Iranian Refugees Resettled in Sweden. Journal Of Immigrant Health, 6(2), 71–81. doi: 10.1023/B:JOIH.0000019167.04252.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb BH, & Bergen AE (2010). Social support concepts and measures. Journal of psychosomatic research, 69(5), 511–520. Doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootaert C, Narayan D, Woolcock M, Nyhan-Jones V. (2004). Measuring social capital: An integrated questionnaire. World Bank working paper no. 18 Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (2009). Characterizing Sexual Violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Profiles of Violence, Community Responses, and Implications for the Protection of Women. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and Open Society Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby A. (1994). Felt versus enacted stigma: A concept revisited. Evidence from a study of people with epilepsy in remission. Social Science & Medicine, 38, 269–274. Doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90396-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PJ, & Stoll K. (2008). Remittance patterns of southern Sudanese refugee men: Enacting the global breadwinner role. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal Of Applied Family Studies, 57(4), 431–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Josse E. (2010). ‘They came with two guns’: the consequences of sexual violence for the mental health of women in armed conflicts. International Review of the Red Cross, 92(877), 177–195. Doi: 10.1017/s1816383110000251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, & Berkman LF (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban health, 78(3), 458–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JT, Betancourt TS, Mukwege D, Lipton R, & VanRooyen MJ (2011). Experiences of female survivors of sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo: a mixed-methods study. Confl Health, 5, 25. Doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-5-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Kabanga J, Cragin W, Alcayna-Stevens L, Haider S, & Vanrooyen MJ (2012). ‘If your husband doesn’t humiliate you, other people won’t’: Gendered attitudes towards sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Global Public Health, 7(3), 285–298. Doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.585344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinyanda E, Musisi S, Biryabarema C, Ezati I, Oboke H, Ojiambo-Ochieng R, ... & Walugembe J. (2010). War related sexual violence and it’s medical and psychological consequences as seen in Kitgum, Northern Uganda: A cross-sectional study. BMC international health and human rights, 10(1), 28. Doi: 10.1186/1472-698x-10-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli A, Tosha M, Ramazani P, Safari O, Bachunguye R, Zahiga I, ... & Glass N. (2013). Family and community rejection and a Congolese led mediation intervention to reintegrate rejected survivors of sexual violence in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Health care for women international, 34(9), 736–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli A, Perrin NA, Mpanano RM, Mullany LC, Murhula CM, Binkurhorhwa AK, ... & Glass N. (2014). Risk for family rejection and associated mental health outcomes among conflict-affected adult women living in rural eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Health care for women international, 35(7–9), 789–807. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.903953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasalvia A, Zoppei S, Van Bortel T, Bonetto C, Cristofalo D, Wahlbeck K, ...Thornicroft G. (2013). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination reported by people with major depressive disorder: A cross-sectional survey. The Lancet, 381(9860), 55–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61379-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2006). Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet, 367(9509), 528. Doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68184-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S-H, Srikrishnan AK, Zelaya CE, Solomon S, Celentano DD, & Sherman SG (2011). Measuring perceived stigma in female sex workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Care, 23, 619–627. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza NB, Hall BJ, Mordeno IG, & Latkin CA (2017). Evidence of the paradoxical effect of social network support: A study among Filipino domestic workers in China. Psychiatry Research, 255, 263–271. Doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, & Lavelle J. (1992). The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 180(2), 111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SM, Robinette KL, Bolton P, Cetinoglu T, Murray LK, Annan J, & Bass JK (2018a). Stigma among survivors of sexual violence in Congo: scale development and psychometrics. Journal of interpersonal violence, 33(3), 491–514. Doi: 10.1177/0886260515608805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SM, Augustinavicius J, Kaysen D, Rao D, Murray L, Wachter K, Annan J, Falb K, Bolton P, Bass J. (2018b). The impact of Cognitive Processing Therapy on stigma among sexual violence survivors in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Conflict and Health, 12(1), 1–9. Doi: 10.1186/s13031-018-0142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasim A, Corona R, Belgrave F, Utsey SO, & Fallah N. (2007). Cultural orientation as a protective factor against tobacco and marijuana smoking for African American young women. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(4), 503–516. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, & Martin JK (2015). The stigma complex. Annual review of sociology, 41, 87–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J, & Salovey P. (1989). Health psychology. Annual review of psychology, 40(1), 533–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scambler G, & Hopkins A. (1986). Being epileptic: Coming to terms with stigma. Sociology of Health & Illness, 8, 26–43. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11346455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, Briggs‐Phillips M, & Hobfoll SE (2006). Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner‐city women. Journal of traumatic stress, 19(6), 825–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Melville F, Steel Z, Lacherez P. (2006). Trauma, post-migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled Sudanese refugees. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(2), 179–187. Doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Rouhani S, Greiner A, Albutt K, Kuwert P, Hacker MR, VanRooyen M & Bartels S. (2015). Respondent-driven sampling to assess mental health outcomes, stigma and acceptance among women raising children born from sexual violence-related pregnancies in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. BMJ open, 5(4), e007057. Doi: 0.1136/bmjopen-2014-007057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, & Mqeketo A. (2007). Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Social science & medicine, 64(9), 1823–1831. Doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simich L, Beiser M, & Mawani FN (2003). Social support and the significance of shared experience in refugee migration and resettlement. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 25(7), 872–891. Doi: 10.1177/0193945903256705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark L, & Wessells M. (2012). Sexual violence as a weapon of war. JAMA, 308(7), 677–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner B, Benner MT, Sondorp E, Schmitz KP, Mesmer U, & Rosenberger S. (2009). Sexual violence in the protracted conflict of DRC programming for rape survivors in South Kivu. Conflict and Health, 3(1), 1. Doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-3-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (1985). Social support and psychological well-being: Theoretical possibilities. In Social support: Theory, research and applications (pp. 51–72). Springer; Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE (1999). Social support and recovery from sexual assault: A review. Aggression and violent behavior, 4(3), 343–358. Doi: 10.1016/s1359-1789(98)00006-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Townsend SM, Filipas HH, & Starzynski LL (2007). Structural models of the relations of assault severity, social support, avoidance coping, self‐blame, and PTSD among sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(1), 23–37. Doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00328.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on psychological science, 4(3), 236–255. Doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2017) DRC Regional Refugee Response. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online at: http://data.unhcr.org/drc/regional.php (accessed 24 February 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Veling W, Hall BJ, & Joosse P. (2013). The association between posttraumatic stress symptoms and functional impairment during ongoing conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of anxiety disorders, 27(2), 225–230. Doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, & Marmot M. (2003). Social determinants of health: the solid facts. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- William P, Barclay L & Schmied V. (2004). Defining social support in context: A necessary step in improving research, intervention and practice. Qualitative Health Research, 14(7), 942–960. Doi: 10.1177/1049732304266997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winokur A, Winokur DF, Rickels K, & Cox DS (1984). Symptoms of emotional distress in a family planning service: stability over a four-week period. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 144(4), 395–399. Doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.4.395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]