Background and Definition of Placebo

A placebo is defined as a substance or procedure which is void of therapeutic value and can be used in multiple forms including tablet, physical, psychological, or surgical. While placebo has been a known notion since ancient times, the concept of placebo was initially introduced to the medical field in the late 18th century and currently has a designated role in the medical research. Examples of placebo include the use of oral or sublingual tablets of inert substances. They are considered placebo as they are without known intrinsic therapeutic properties. Other examples of procedural placebos are the use of intra–articular injections of inert substances or the use of sham surgeries. While at times considered controversial, placebo use has been instrumental in advancing the medical and healthcare knowledge as well as the quality and efficacy of treatments.

History of Placebo and the Placebo Effect

The early mention of placebo in the medical literature dates to the late 1700s when English physician, Dr. Alexander Sutherland, coined the term to describe a physician with great bedside manners.1 The term placebo was later used by William Cullen, a Scottish pharmacologist, to annotate the practice of prescribing a drug that was perceived to be ineffective according to the medical knowledge at that time.1 This was done to satisfy a patient’s request for a remedy and meet their expectations rather than aiming to cure the underlying illness. At that time, placebo meant any substance regarded as a weak or ineffective medicine for a particular ailment. The use of placebo in this context was widely prevalent during this period. However, the approach to placebo uses progressively changed with the introduction of the concept of utilizing an inert substance without any pharmacological effect. Some materials that were commonly used include sugar and breadcrumbs. One example of this practice was described in the treatment of syphilis. In the 1800s, before the use of penicillin, patients were prescribed pills that were made of breadcrumbs in the treatment syphilis.2

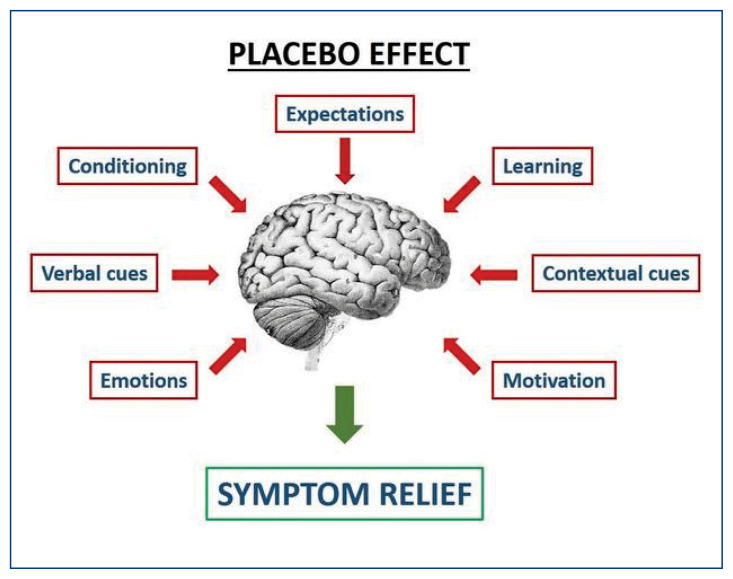

More recently, placebo has been employed in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of a new treatment. Scientists compare the characteristics of a group of participants who received the study drug to those who received the placebo drug. Based on this, a conclusion is derived about the study drug’s efficacy in achieving preset clinical parameters and end points. Typically, both study groups, intervention group and placebo group, as well as the investigators and study staff are blinded to the nature of the treatment that they receive. If no difference is seen between those two groups, the study drug is thought to be no different in efficacy than placebo. However, a new paradigm emerged noting that the lack of difference between the study drug and placebo groups can be indicative of other factors, including a component of patients’ psychology and other non–pharmacological mechanisms at play rather than a treatment’s lack of efficacy. The “placebo effect” was further defined as an improvement of a clinical condition through use of a sham treatment secondary to the patient’s perception of that intervention. The examined disease and perceived outcome also impact the effect of placebo. For example, in the context of the treatment of pain, placebo has been shown to have a small beneficial effect based on the patient’s perception, even though that there was no evidence of a powerful clinical effect.3 The placebo effect is now regarded as a complex interplay of a patient’s specific underlying psychological factors and neural pathways. The anticipation of an improvement with the prescribed treatment and a belief of its efficacy are fundamental to the concept of placebo effect.

Placebo controlled trials were first conducted in the 1940s, soon followed by the landmark paper “The Powerful Placebo” which called attention to the placebo effect and underscored the importance of considering this concept to accurately determine a treatment’s efficacy.4 In that meta–analysis of 15 studies, placebo was used to alleviate multiple symptoms, including pain, cough, and anxiety. Placebo showed an improvement, on average of 35% of symptoms. Following this study, the interest in examining the placebo effect has progressively grown in the medical literature. Today, research data that is based on randomized double–blind placebo–controlled trials remains the highest quality of evidence available to test the efficacy of a specific treatment.

Uses of Placebo in the Clinical Practice and Research Field

Placebo has ubiquitous uses in clinical practice and research. For instance, in chronic pain conditions, clinical improvement is seen with a placebo response but is further strengthened by patient–centered care.5 To help further differentiate the different roles of placebo, a distinction between pure and ‘impure’ placebo nomenclature was created. Impure placebo is identified as a substance with pharmacologic effect that is suspected or recognized to have no effect on clinical disease but is given for a potential psychological benefit.5 On the other hand, pure placebo is an inactive substance without direct physiologic effect. Examples of impure placebo include the use of antibiotics in viral infections or vitamin infusions in the treatment of cancer, while examples of a pure placebo would include saline injection or the use of sugar–filled capsules. It is important to note that there remains a lack of consensus on the definition of ‘impure’ placebo.

Placebo has also been used in the form of a placebo surgery, or sham surgery, which involves replicating the surgical procedure setting with anesthesia use and an incision but without an intervention otherwise. In a study by Moseley et al., participants with knee osteoarthritis were randomized under double–blind conditions to three groups of arthroscopic debridement, lavage or placebo surgery.6 Both patients and the study personal who performed the assessment of the outcome were blinded to the patient’s assignment to treatment and placebo groups. The surgeon who performed the procedure did not participate in the outcome analysis. Placebo surgery involved a skin incision with a simulated debridement without inserting the arthroscope, while the interventions included either debridement or lavage. The aim was to evaluate the efficacy of arthroscopic surgery of the knee in pain relief at two years. Remarkably, the placebo surgery group described a pain relief that is similar to the group who underwent the lavage or debridement surgical interventions over a two–year period.6

In contrast to prior practices, the current use of pure placebo as a deceptive form of treatment is rare and more importantly, is considered unethical. Prescribing supplements or drugs as ‘impure’ placebos is a widespread practice, particularly in chronic pain conditions.7,8 In 2008, a national survey of 1200 practicing internists and rheumatologists reported that approximately 50% of physicians used such prescribing practices, and 62% of those physicians believed the practice to be ethically permissive.7 In particular, the most commonly used placebo treatments in this U.S. study were over the counter analgesics at approximately 41% of prescriptions, followed by antibiotics and sedatives. Alarmingly, even use of saline and sugar pills was reported, albeit to a lesser degree, of around 2% of surveyed physicians.7 Interestingly, the physician’s description and presentation of the actual placebo is an important factor. Most physicians label placebo as a potentially beneficial medicine or treatment, but only 9% refer to them as a placebo.7

The frequency of prescribing pure placebo substances and impure placebo therapies differs.9 In a European study, of 500 patient contacts per month in the United Kingdom (UK) and 1,000 in Germany, it was estimated that around 2% of UK general practitioners (GPs) prescribed pure placebo compared to 9–14% of German counterparts. On the other hand, prescribing non–specific therapies was much higher in both groups and approximated at 89% of GPs in the UK as opposed to around 57–69% of their German counterparts. The estimated use of ‘impure’ placebo was variable. Use of vitamins was reported by 23%–75% of GPs, use of antibiotics by 17%–69% of GPs, and use of supplements by 35%–59% of GPs. This study showed that while impure placebo use is not as prevalent as pure placebo use, both remain in the toolkits of practitioners.

Similar trends were also seen in another German study.10 In 2014, a German survey regarding the use of pure and impure placebo use was sent to GPs, internists, and orthopedic specialists. This study found that the use of placebos, both pure and impure, were more commonly utilized by GPs and least used by orthopedists. It was also found that impure placebos were more commonly used than pure placebos. Finally, it was found that the physician’s attitude and belief in the use of alternative and complementary medicine impacted the behavior of prescribing such substances.10 Such prescription practices pose significant ethical challenges, as the perspective and attitude towards placebo use can differ substantially between health care providers and patients. Within the healthcare provider group itself, opinions on placebo use remain divergent. Healthcare providers often have different reasons for prescribing placebo, some of which include satisfying patients’ demands for treatment, offering a treatment option to patients with an incurable disease, or providing treatment for nonspecific symptoms.11 Maintaining the patient–doctor relationship is a prominent motive for placebo use, primarily to avoid conflicts, limit drug addiction, and to shy away from telling patient that treatment options are limited.11 Such complex interactions between patients and their health care provider create an ethical dilemma that is compounded by insufficient data and lack of evidence.8

Another role of placebo is to help differentiate functional etiologies of disease from organic causes.8 While the use of placebo in this capacity is rare, there is an increased interest in pursuing open label placebo randomized trials whereby participants are aware that a placebo is given. One example is a study of patients with irritable bowel syndrome who were randomized in an open label fashion to either a no–treatment group or a placebo pill group.12 Patients met with a health care provider prior to the randomization and were informed that the placebo was an inert and inactive pill without any medication in it with “self–healing properties” and the placebo effect was described to the participants. Patients in the open–label placebo group had higher reduction in symptoms as measured by standardized scales as compared to those in the no–treatment group. This study evidenced that an openly described inert placebo can be used and produce a symptomatic improvement without need for blinding or even deception.12 Limitations of report bias and selection bias of motivated participants were noted in this study and could have impacted the results due to the open label study format.

Ethical Considerations of Use of Placebo

Placebo use in clinical trials, a robust debate is ongoing related to its ethical implications and whether such placebo use should be halted. The purpose of introducing placebo into clinical trials is to separate the effect of the drug in question from the presumed lack of effect of placebo.13 Arguments against the use of placebo in clinical trials focus on the thought that patients may be deprived of potential effective treatments.14 Critics has also raised the concern that placebo use can potentially lead to delays of the proper diagnosis and timely treatment of diseases with the current standard of care therapy. Some argue placebo use is noncontributory to the daily clinical questions that physicians face, which revolves around the choice of one treatment among two possible treatment modalities rather than choice between one treatment or a placebo.15 Placebo use can also potentially interfere with the proper effect size estimation of the specific treatments at question.15 Some argue that the aim of both the physicians and the patients is to clarify and measure the total effect of an intervention, rather than the consequences and course of the disease if that intervention was not used. When there is a large psychological component of the placebo used in trials, the effect size of the intervention is perceived as small but the total effect including placebo might carry a significant clinical interest. In that context, placebo–controlled trials measure the treatment effect only. With respect to the use of placebo surgery in clinical trials, some find it unethical since it subjects patients to an invasive procedure with potential risks, without gaining any of the potential benefits of the effective surgery.

Proponents of placebo use argue that this practice is ethically justified by the informed consent in circumstances where potential harm of delaying effective therapy is minimal. Along the same lines, advocates also reason that the vital need for scientifically valid clinical data that measures the true effect of a treatment justifies the methodology of using placebo while considering the aforementioned risks which are minimized to the lowest degree possible.

Worries exist about the possible lack of transparency and accuracy of the information provided to the participants regarding the explanation of the benefits and harms of placebo which were detected in prior trials.16,17 Such an issue places the informed consent at risk of being considered invalid. Another widespread critique of placebo use is that a valid assessment of the benefit of treatment requires concealment of placebo use. Open label placebo treatment trials offer a potential ethical solution to the problem of blinding of placebo use that some critics describe as deceptive. Open label placebo treatment was shown to conform with ethical standards of transparency, informed consent and respect for an individual choice and autonomy.18 It is promising that patients are also open to trying such open label placebo studies.19 Studies have shown that patients value the physician’s transparency and honesty about the use of placebo with an emphasis on the physician’s level of confidence in the benefits, safety and purpose of that treatment.20 Physicians also viewed honest and transparent communication with the patient regarding the outcome as critical.21 A shared decision–making model should involve a physician–patient conversation about the role of placebo effect in clinical care.22

Conclusion

Placebo use has become widespread in the medical field in multiple forms with varied applications. Since placebo use for prescriptions and for clinical trials carries problematic issues, numerous ethical considerations remain important in this discussion of their use. Transparency in informed consent as well as honest and clear communication remain key in maintaining patient–physician relationship. Despite the rising research interest in this field, there remains a paucity of data, and further research in this field is necessary to explore multiple unanswered questions.

Footnotes

Gebran Khneizer, MD,(left), is a Fellow, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and Roshani Desai, MD,(right), is an Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Both are at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

References

- 1.Jütte R. The early history of the placebo. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21(2):94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treatise A. on the Venereal Disease and Its Varieties. Med Chir Rev. 1833;19(37):38–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(21):1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beecher HK. The powerful placebo. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;159(17):1602–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960340022006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaptchuk TJ, Hemond CC, Miller FG. Placebos in chronic pain: evidence, theory, ethics, and use in clinical practice. Bmj. 2020;370:m1668. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moseley JB, O’Malley K, Petersen NJ, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(2):81–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tilburt JC, Emanuel EJ, Kaptchuk TJ, Curlin FA, Miller FG. Prescribing “placebo treatments”: results of national survey of US internists and rheumatologists. Bmj. 2008;337:a1938. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fässler M, Meissner K, Schneider A, Linde K. Frequency and circumstances of placebo use in clinical practice––a systematic review of empirical studies. BMC Med. 2010;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linde K, Atmann O, Meissner K, et al. How often do general practitioners use placebos and non–specific interventions? Systematic review and meta–analysis of surveys. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linde K, Friedrichs C, Alscher A, Wagenpfeil S, Meissner K, Schneider A. The use of placebo and non–specific therapies and their relation to basic professional attitudes and the use of complementary therapies among German physicians––a cross–sectional survey. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e92938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fässler M, Gnädinger M, Rosemann T, Biller–Andorno N. Use of placebo interventions among Swiss primary care providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:144. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaptchuk TJ, Friedlander E, Kelley JM, et al. Placebos without deception: a randomized controlled trial in irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chavarria V, Vian J, Pereira C, et al. The Placebo and Nocebo Phenomena: Their Clinical Management and Impact on Treatment Outcomes. Clin Ther. 2017;39(3):477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothman KJ, Michels KB. The continuing unethical use of placebo controls. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(6):394–398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vickers AJ, de Craen AJ. Why use placebos in clinical trials? A narrative review of the methodological literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(2):157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blease CR, Bishop FL, Kaptchuk TJ. Informed consent and clinical trials: where is the placebo effect? Bmj. 2017;356:j463. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bishop FL, Adams AE, Kaptchuk TJ, Lewith GT. Informed consent and placebo effects: a content analysis of information leaflets to identify what clinical trial participants are told about placebos. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blease C, Colloca L, Kaptchuk TJ. Are open–Label Placebos Ethical? Informed Consent and Ethical Equivocations Bioethics. 2016;30(6):407–414. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishop FL, Aizlewood L, Adams AE. When and why placebo–prescribing is acceptable and unacceptable: a focus group study of patients’ views. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hull SC, Colloca L, Avins A, et al. Patients’ attitudes about the use of placebo treatments: telephone survey. Bmj. 2013;347:f3757. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosén A, Sachs L, Ekdahl A, et al. Surgeons’ behaviors and beliefs regarding placebo effects in surgery. Acta Orthop. 2021;92(5):507–512. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2021.1941627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brody H, Colloca L, Miller FG. The placebo phenomenon: implications for the ethics of shared decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(6):739–742. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1977-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]