Abstract

Capsules from a range of pathogenic bacteria are key virulence determinants, and the capsule has been implicated in virulence in Pasteurella multocida. We have previously identified and determined the nucleotide sequence of the P. multocida M1404 (B:2) capsule biosynthetic locus (J. D. Boyce, J. Y. Chung, and B. Adler, Vet. Microbiol. 72:121–134, 2000). The cap locus consists of 15 genes, which can be grouped into three functional regions. Regions 1 and 3 contain genes proposed to encode proteins involved in capsule export, and region 2 contains genes proposed to encode proteins involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis. In order to construct a mutant impaired in capsule export, the final gene of region 1, cexA, was disrupted by insertion of a tetracycline resistance cassette by allelic replacement. The genotype of the tet(M) ΩcexA mutant was confirmed by Southern hybridization and PCR. The acapsular phenotype was confirmed by immunofluorescence, and the strain could be complemented and returned to capsule production by the presence of a cloned uninterrupted copy of cexA. Wild-type, mutant, and complemented strains were tested for virulence by intraperitoneal challenge of mice; the presence of the capsule was shown to be a crucial virulence determinant. Following intraperitoneal challenge of mice, the acapsular bacteria were removed efficiently from the blood, spleen, and liver, while wild-type bacteria multiplied rapidly. Acapsular bacteria were readily taken up by murine peritoneal macrophages, but wild-type bacteria were significantly resistant to phagocytosis. Both wild-type and acapsular bacteria were resistant to complement in bovine and murine serum.

Pasteurella multocida is the causative agent of a wide range of diseases in both wild and domestic animals, and the diseases which affect livestock cause significant economic losses worldwide. Many P. multocida strains express a polysaccharide capsule on their surface, and isolates can be differentiated serologically by capsular antigens into serogroups A, B, D, E, and F (5, 26). The disease caused by the organism is generally dependent on capsular type, since serogroups B and E cause hemorrhagic septicemia in cattle and buffalo, serogroup A causes fowl cholera in poultry, and serogroup D causes atrophic rhinitis in pigs.

Polysaccharide capsules are found on the surface of a wide range of bacteria. With gram-negative bacteria, the capsule lies outside the outer membrane and is composed of highly hydrated polyanionic polysaccharides (27). Capsules have a significant role in determining access of certain molecules to the cell membrane, mediating adherence to surfaces, and increasing tolerance of desiccation. Furthermore, capsules of many pathogenic bacteria impair phagocytosis (22, 29, 30) and reduce the action of complement-mediated killing (7, 31, 35). Thus, capsules are likely to be major virulence determinants, and indeed, genetically defined acapsular mutants of a number of organisms have been shown to have reduced virulence (Vibrio vulnificus [38], Streptococcus spp. [30, 36], Staphylococcus aureus [32], Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae [35], Haemophilus influenzae [17, 20], Klebsiella pneumoniae [9], and Cryptococcus neoformans [8]). The capsule has been implicated in virulence in P. multocida, since encapsulated strains have been shown to be more virulent (15) and able to resist complement-mediated killing (10, 31) than spontaneous acapsular strains. However, no genetically defined acapsular strains have been constructed to allow unequivocal demonstration of the P. multocida capsule as a virulence determinant. Experiments with purified P. multocida B:6 capsular extract have indicated that it has significant antiphagocytic activity, although it should be noted that the extract used contained small amounts of nucleic acid and protein contaminants (21).

We have recently determined the nucleotide sequence of the P. multocida M1404 capsule biosynthetic locus (4). Like other gram-negative group II-like polysaccharide capsule biosynthetic loci, the genes can be grouped into three functional regions. Regions 1 and 3 contain a total of six genes, which are involved in transport of the polysaccharide, while region 2 contains nine genes, which are postulated to be involved in the biosynthesis of the polysaccharide. The proteins encoded by regions 1 and 3 showed significant similarity to those encoded by capsule export genes. Using this information, we have constructed isogenic strains impaired in capsule export to investigate the contribution to virulence of the P. multocida M1404 capsule.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. P. multocida B:2 strain M1404 and Escherichia coli DH5α were grown with aeration at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) or 2YT (Oxoid, Hampshire, England), respectively. Kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and tetracycline (5 μg/ml for P. multocida and 15 μg/ml for E. coli) were added to solid and liquid media when required.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F−endA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk+) thi-1 λ− recA1 gyrA96 relA1 φ80dlacZΔM15 | Bethesda Research Laboratories, Rockville, Md. |

| P. multocida | ||

| M1404 | Serotype B:2 wild-type strain | K. R. Rhoades, National Animal Disease Center, Ames, Iowa |

| PBA875 | M1404 tet(M) ΩcexA mutant containing pPBA1100; Kanr Tetr | This study |

| PBA1514 | M1404 tet(M) ΩcexA mutant, complemented with pPBA1621; Kanr Tetr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPBA1100 | P. multocida-E. coli shuttle vector; Kanr | 12 |

| pPBA1620 | pWSK129 containing the tet(M) ΩcexA mutagenesis cassette; Kanr Tetr | This study |

| pPBA1621 | cexA cloned in pPBA1100 under control of the lacZ promoter; Kanr | This study |

| pWSK129 | Low-copy-number E. coli cloning vector; Kanr | 34 |

| pVB101 | pBR322 containing the tet(M) gene from Tn916; Apr Tetr | Vickers Burdett, Duke University, Durham, N.C. |

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Genomic DNA was prepared by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide precipitation (2), and plasmid DNA was prepared by alkaline lysis (3). Plasmid DNA was further purified by polyethylene glycol precipitation (2) or by purification on Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) anion-exchange columns. DNA restriction and ligation reactions were carried out using enzymes obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Basel, Switzerland) or New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.), and reactions were performed according to the manufacturers' instructions. DNA was introduced into E. coli and P. multocida by electroporation as previously described (2, 14). DNA sequencing was carried out using the BigDye Ready Reaction DyeDeoxy Terminator cycle sequencing kits (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.), and the reactions were analyzed with a 373A DNA sequencing system.

PCR amplification was performed with the Expand high-fidelity PCR kit, using the reaction conditions specified by the manufacturer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Oligonucleotides used in this investigation are listed in Table 2. Prior to sequencing or cloning, PCR fragments were purified by polyethylene glycol precipitation. Southern hybridizations were carried out as described previously (4).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence | Positiona |

|---|---|---|

| BAP474 | 5′-ATTCAACAGATAAAGAGAGAG-3′ | 284–304 |

| BAP494 | 5′-CTACCAATTAGAGATTTTTACG-3′ | 2325–2304 |

| BAP518 | 5′-NNNNNNGAATTCATGCGATCTCGTG-3′ | 2376–2352 |

| BAP519 | 5′-CGCCCGAGGATCCCTACTTTCTC-3′b | 589–611 |

| BAP520 | 5′-GCGTAATGGATCCGGGAAATCAAC-3′b | 591–568 |

| BAP521 | 5′-CGTCATCAGTCGACGTCACG-3′ | —c |

| BAP745 | 5′-GTTACAAAGCTTTTAGCTGATG-3′b | —d |

| BAP747 | 5′-GGGAATGTTTGCTATCGG-3′ | 1028–1011 |

Position relative to the sequence deposited in GenBank (accession no. AF169324).

Does not match the wild-type sequence exactly due to the incorporation of restriction sites.

This sequence is approximately 550 bp 5′ of bp 1 (GenBank accession no. AF169324).

This sequence is approximately 50 bp 5′ of bp 1 (GenBank accession no. AF169324).

Construction of acapsular P. multocida M1404 (B:2) by allelic exchange.

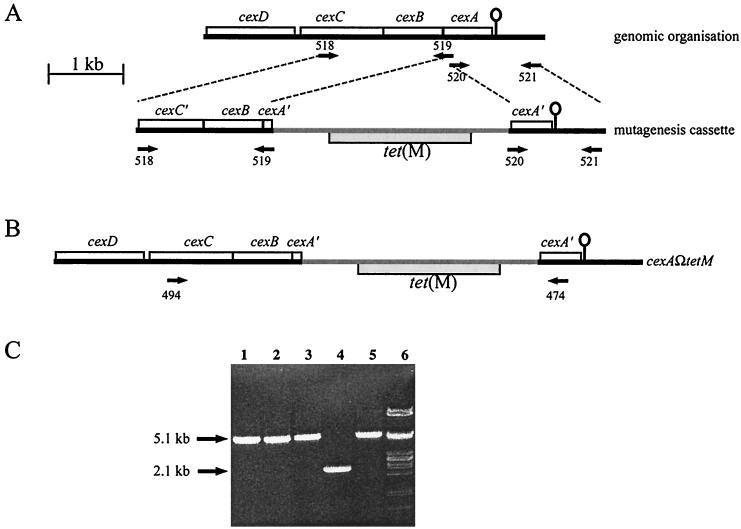

A DNA fragment containing a tet(M) insertion in cexA was constructed by ligating two PCR-generated fragments to the tet(M) gene from pVB101 (Fig. 1A). The oligonucleotides BAP521 and BAP520 (Table 2) were used to amplify by PCR a 1,100-bp fragment containing the 178 codons of cexA corresponding to the C terminus and 615 bp of downstream DNA. The oligonucleotides BAP519 and BAP518 (Table 2) were used to amplify a 1,800-bp fragment containing the 36 codons of cexA corresponding to the N terminus, all of cexB, and the 329 codons of cexC corresponding to the C terminus. These PCR-generated fragments were ligated to either end of the BamHI fragment from pVB101, which contains tet(M), and were cloned into pWSK129 to generate pPBA1620 (Table 1). The cloned mutagenesis cassette was further amplified by PCR, using pPBA1620 as a template and using oligonucleotides from the pWSK129 polylinker. Approximately 3 μg of each of the linear DNA fragments was used to transform P. multocida M1404 by electroporation (14), and the transformants were selected on NA (2.5% nutrient broth no. 2 [Oxoid], 0.3% tryptone, 1.0% agar) plates containing 5 μg of tetracycline/ml.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of construction of the capsule-deficient mutant of P. multocida M1404. (A) A 1,800-bp fragment containing all of cexB and part of cexA and cexC was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotides BAP518 and BAP519 (designated by arrows labeled 518 and 519). Similarly, a 1,100-bp fragment containing part of cexA and downstream DNA was amplified by using the oligonucleotides BAP520 and BAP521 (designated by arrows labeled 520 and 521). These fragments were ligated to either end of the tet(M) gene to obtain the linear DNA (mutagenesis cassette) used for mutagenesis by allelic exchange. The line-and-ball characters indicate the location of a putative transcriptional terminator, proposed to constitute the end of the cap locus (4). (B) Integration of the fragment by double-crossover homologous recombination would give rise to Tetr bacteria with inactive cexA. (C) The genotypes of three putative mutants were investigated by PCR. Genomic DNA was isolated from each mutant (lanes 1 to 3) and P. multocida M1404 (lane 4) and was used as a template for PCR with oligonucleotides BAP474 and BAP494. For comparison, the mutagenesis cassette DNA was also used as a template for PCR with the oligonucleotides BAP474 and BAP494 (lane 5). Lane 6 contains λ DNA digested with PstI. The sizes of the PCR products are indicated.

Identification of the surface exported capsule by immunofluorescence.

The P. multocida M1404 capsule was visualized by immunofluorescence as previously described (6). To maximize capsule production, cells were grown on dextrose starch agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) containing 6% avian serum (Monash University Animal Services, Clayton, Australia) prior to fixation. The primary antibody was P. multocida serogroup B capsular typing serum (kindly supplied by Thula Wijewardana, Veterinary Research Institute, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka), and the secondary antibody was fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin. FITC-labeled preparations were visualized with a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) IM35 epifluorescence inverted microscope, using a 100× oil immersion objective. Kodak Elite chrome 200 ASA film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) was used to record the images, and the processed slides were scanned with a Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) Coolscan II. Minor adjustments to the scanned images, which did not affect the data integrity, were completed in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, Calif.).

Assessment of virulence of acapsular P. multocida.

P. multocida strains were grown in BHI to an optical density at 650 nm of 0.6 and diluted in BHI to obtain cultures of approximately 102 to 109 CFU/ml. Exact bacterial numbers in each dilution were checked by direct-plate viable counts. Groups of at least six mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with aliquots of 0.1 ml of the appropriate dilutions. Mice were observed for signs of disease and were killed by cervical dislocation when deemed moribund, in accordance with animal ethics requirements. A control group of six mice injected with BHI showed no effects.

Kinetics of P. multocida infection of mice.

Groups of three mice were injected i.p. with 5 × 104 CFU, and bacterial counts were determined from the blood, liver, and spleen at 1, 4, 24, and 48 h after injection. Blood samples were taken from the retro-orbital plexus and diluted in BHI containing heparin prior to plating on NA. Liver and spleen were removed aseptically, homogenized in 4 ml of BHI, and, where necessary, diluted further in BHI prior to plating on NA.

Uptake of bacteria and survival inside macrophages.

Bacterial uptake and survival within mouse peritoneal macrophages were determined by using gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria as described previously (25). Mouse peritoneal macrophages were harvested as described previously (33), except that an influx of macrophages was stimulated 48 h prior to harvest with 1 ml of 2% starch. The cells were resuspended in 3 ml of M199 (CSL Ltd., Melbourne, Australia) containing 10% fetal calf serum (M199-FCS), dispensed into Lab Tek Slide chambers (Nunc, Naperville, Ill.), and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 16 h to allow cells to adhere to the slide surface. The medium was removed, and the cells were washed three times in M199-FCS. The cells were incubated for a further 48 h, with a medium change and wash at 24 and 48 h. Bacteria (107 CFU) were resuspended in M199-FCS, added to the macrophages, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The slides were then washed five times in M199-FCS containing 200 μg of gentamicin/ml, and incubation was continued for a further 30 min. The supernatant was removed, and the macrophages were lysed by addition of 0.4 ml of cold BHI. The numbers of released bacteria were determined by direct plate counts. Strains were tested in triplicate slide wells.

Bacterial interaction with murine peritoneal phagocytes.

Mouse peritoneal macrophages were harvested and grown as described above. Bacteria were grown in BHI to an optical density at 650 nm of 0.3, washed once in phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in M199-FCS at 108 CFU/ml. Approximately 3 × 107 bacteria were added to the slide chambers containing the murine macrophages and were incubated for 90 min at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Slides were then washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline and stained with Giemsa stain for 20 min. Cells were visualized with a Zeiss IM35 inverted microscope using a 100× oil immersion objective, and images were recorded as described previously. A total of 100 (PBA875 and PBA1514) or 150 (P. multocida M1404) macrophages was observed across multiple randomly chosen microscope fields, with the presence of interacting bacteria recorded. Strains were tested in triplicate or quadruplicate slide wells.

Serum sensitivity assays.

The sensitivity of P. multocida strains to the bactericidal complement activity of bovine (AMRAD, Adelaide, Australia) or murine (Monash University Animal Services) serum was determined by direct plate counts after incubation of approximately 104 bacteria in 90% serum for 4 h at 37°C with shaking. Complement activity was inactivated in control samples by heating at 56°C for 30 min.

Statistics.

Analysis of bacterial survival within macrophages was performed using ordinary analysis of variance, followed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test. Analyses of serum sensitivity data were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric analysis of variance test (corrected for ties), followed by Dunn's posttest. Approximate probability values were determined using InStat, version 2.03 (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

Construction of P. multocida mutants impaired in capsule polysaccharide export.

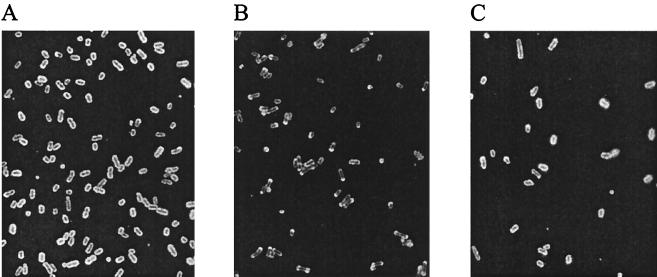

The capsule biosynthetic locus of P. multocida has been described previously (4). To evaluate the role of the P. multocida capsule in virulence, we constructed an isogenic mutant in which capsule export was inactivated. A DNA fragment containing a tetracycline resistance cassette within cexA (at codons 36 to 40) was constructed by PCR (Fig. 1) (see Materials and Methods). Three putative mutants were identified, and the genotypes were investigated by PCR (Fig. 1C) and Southern hybridization (data not shown). All three colonies contained the tet(M) insertion within cexA, and one isolate was designated PBA875. The phenotype of PBA875 was investigated by immunofluorescence, using P. multocida type B antiserum as the primary antibody (Fig. 2). P. multocida M1404 (wild type) showed strong fluorescence completely encircling the cells, while PBA875 showed markedly polar fluorescence (Fig. 2A and B, respectively), indicating failed capsular export. Furthermore, PBA875 cells were often significantly elongated compared to wild-type cells, especially after continued incubation on solid medium (data not shown). The immunofluorescence profile of this strain was virtually indistinguishable from that of a previously described H. influenzae bexA (cexA homologue) mutant (17). As a control, the phenotype of PBA875 was investigated by immunofluorescence using the antilipopolysaccharide (anti-LPS) monoclonal antibodies T1C6 and T2B2 (24) as the primary antibodies. No difference was observed between the immunofluorescence profile of PBA875 and wild-type P. multocida M1404 with either anti-LPS antibody, indicating that LPS biosynthesis and transport had not been affected in the mutant strain.

FIG. 2.

Phenotypic characterization of P. multocida capsule expression. Photomicrographs of methanol-fixed P. multocida M1404 (A), PBA875 (B), and PBA1514 (C) visualized by immunofluorescence, with P. multocida serogroup B typing antiserum as the primary antibody and FITC-labeled anti-rabbit immunoglobulin as the secondary antibody.

In order to complement the mutant strain, a plasmid was constructed which contained an uninterrupted copy of cexA. A fragment containing cexA was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotides BAP745 and BAP747 (Table 2), digested with HindIII, and cloned into the HindIII site of pPBA1100 to generate pPBA1621 (Table 1). The plasmid pPBA1621 was transformed into PBA875 to generate the strain PBA1514. The phenotype of PBA1514 was shown by immunofluorescence to be close to that of the wild type (Fig. 2C). The growth rate of PBA1514 was indistinguishable from the growth rates of PBA875 in both 2YT broth (data not shown) and bovine and murine serum (see below).

Acapsular P. multocida is significantly impaired in virulence.

The virulence properties of P. multocida M1404, PBA875, and PBA1514 were investigated by i.p. challenge of mice (Table 3). Wild-type P. multocida had a 50% infective dose (ID50) of <10 CFU and an ID100 of <1,000 CFU. At a dose of 10 CFU, only 17% of mice survived the challenge. In contrast, no deaths were recorded for mice challenged with <8 × 105 CFU of PBA875 (acapsular mutant). However, at higher doses some mice developed fatal infections, and the ID50 was calculated to be approximately 107 CFU. Bacteria isolated from the blood of mice which had received fatal doses of PBA875 were shown by PCR and immunofluorescence to be both genetically and phenotypically identical to the PBA875 mutant. The complemented mutant, PBA1514, displayed full wild-type virulence, with an ID50 of <20 CFU and an ID100 of <200 CFU.

TABLE 3.

Virulence of P. multocida M1404, PBA875, and PBA1514, as determined by i.p. challenge of female BALB/c mice

| Strain | Injected dose (CFU) | % Survival (group size) |

|---|---|---|

| M1404 | 10 | 17 (6) |

| 1 × 102 | 10 (11) | |

| 1 × 103 | 0 (6) | |

| PBA875 | 8 × 102 | 100 (21) |

| 8 × 104 | 100 (11) | |

| 8 × 105 | 94 (18) | |

| 8 × 106 | 64 (11) | |

| 8 × 107 | 33 (6) | |

| PBA1514 | 20 | 17 (6) |

| 2 × 102 | 0 (6) |

Acapsular P. multocida is rapidly removed from the blood and other organs.

The kinetics of infection of PBA875 and PBA1514 were investigated following challenge of mice (Table 4). Bacterial counts were determined from the blood, liver, and spleen after injection of 5 × 104 CFU. Bacteria could be isolated from all organs of mice infected with PBA1514, and the numbers of bacteria increased to approximately 5 × 107 CFU in all organs at 24 h (approximately the time of death). By contrast, small numbers of PBA875 (acapsular mutant) organisms were isolated from all organs of the mice 1 h after infection, but none could be isolated from any of the organs 4, 24, or 48 h after infection. These data indicated that when mice were infected with 5 × 104 CFU of PBA875, the bacteria were cleared rapidly to low levels within the first 4 h, whereas PBA1514 could not be cleared and rapidly multiplied in all organs until lethal levels were reached.

TABLE 4.

Kinetics of infection by PBA875 and PBA1514 following i.p. challenge of female BALB/c mice

| Strain | Time (h) | CFUa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Liver | Spleen | ||

| PBA1514 | 1 | 3.8 (±0.3) × 103 | 9 (±6) × 102 | 5 (±3) × 103 |

| 4 | 1 (±0.5) × 105 | 9 (±7) × 104 | 7 (±3) × 104 | |

| 24b | 5 × 107 | 6 × 107 | 2 × 107 | |

| PBA875 | 1 | 2 (±1) × 102 | 5 (±4) × 102 | 1.3 (±1) × 102 |

| 4 | NDc | ND | ND | |

| 24 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 48 | ND | ND | ND | |

Numbers for blood are CFU per milliliter and for the liver and spleen are CFU per total organ. Reported numbers are means (±1 standard deviation) determined from three replicates.

No error limits could be determined for this time point, since only one of the group survived to 24 h.

ND, no bacteria were detected for these time points. The detection limit of the experiment was estimated to be approximately 10 CFU/ml (blood) or 40 CFU/organ (liver and spleen).

Acapsular P. multocida is sensitive to phagocytosis by murine peritoneal macrophages.

P. multocida M1404 has been shown previously to be phagocytosed inefficiently but to survive inside macrophages without multiplication (25). Bacterial uptake and survival within murine peritoneal macrophages were assessed by using gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria. PBA875 was shown to be four- to sixfold more susceptible to macrophage uptake than both wild-type and complemented bacteria. The numbers of surviving bacteria released from lysed macrophages for M1404, PBA875, and PBA1514 were 1,800 ± 400, 7,100 ± 1,800, and 1,200 ± 500 CFU/ml, respectively. The values are the sample mean ±1 standard deviation. The difference between results for PBA875 and those for M1404 or PBA1514 was determined to be highly significant (Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test; P < 0.01), but the difference between results for M1404 and those for PBA1514 was determined to be not significant (P > 0.05). Therefore, acapsular bacteria are both internalized and capable of survival within murine peritoneal macrophages for at least 30 min. The interactions (macrophage uptake and adherence) of P. multocida M1404, PBA875, and PBA1514 with murine peritoneal macrophages were also assessed visually with Giemsa-stained preparations of bacteria and macrophages after 90 min of incubation. Only 9% of macrophages were shown to contain wild-type P. multocida M1404, but 64% of macrophages were observed to contain the acapsular mutant PBA875 (data not shown).

Acapsular and encapsulated P. multocida strains are highly resistant to complement activity in naive serum.

PBA875 and PBA1514 were incubated in 90% bovine serum to investigate their sensitivity to complement-mediated killing. Both P. multocida strains grew rapidly in either untreated or heat-treated serum, whereas E. coli DH5α was rapidly killed in untreated serum but grew in heat-treated serum (Table 5). No statistically significant difference was observed between the growth rates of PBA875 in untreated and heat-treated serum, indicating that the loss of the capsule does not increase sensitivity to complement-mediated killing. Similar results were obtained for growth in murine serum (data not shown), although the level of bactericidal activity against the E. coli control was lower, in accordance with the lower level of bactericidal activity previously observed for murine serum (16). The growth rates of PBA875 and PBA1514 were virtually indistinguishable in both murine and bovine serum, indicating that the reduction in virulence observed for PBA875 was unlikely to be due to an altered growth rate.

TABLE 5.

Sensitivity of P. multocida to bactericidal activity of bovine serum

| Strain | Serum heat treatment | I4ha |

|---|---|---|

| PBA1514 | + | 36 ± 7b |

| PBA1514 | − | 26 ± 4b |

| PBA875 | + | 58 ± 5b |

| PBA875 | − | 33 ± 5b |

| E. coli DH5α | + | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| E. coli DH5α | − | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

I4h is defined as CFU per milliliter at 4 h divided by CFU per milliliter at 0 h. Reported numbers are means ± 1 standard deviation, determined from at least three replicates.

The difference in sensitivity between PBA875 and PBA1514 in either heated or unheated serum was determined to be not significant (Kruskal-Wallis test; P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

A mutant defective in the export of the P. multocida capsule was constructed by allelic exchange. Using the sequence of the P. multocida cap locus (4), a DNA fragment was constructed with a tet(M) insertion within the capsule export gene cexA. The mutant strain (PBA875) showed markedly polar immunofluorescence (Fig. 2), which we suggest is due to a failure of capsular polysaccharide export. A bexA mutant (cexA homologue) in H. influenzae has previously been investigated, and this mutant appeared identical when viewed by immunofluorescence microscopy (17). Detailed analysis of the H. influenzae bexA mutant indicated that it was capable of synthesizing immunoreactive material but failed to export it appropriately (17). These data are in agreement with the expected phenotype of a bexA mutant, since bexA encodes the ATP binding component of the ATP binding cassette transporter complex required for export of capsular polysaccharide (18, 23). Therefore, we believe that PBA875 is also capable of synthesizing immunoreactive polysaccharide but fails to export it correctly. Complementation of PBA875 with a plasmid containing an intact copy of cexA returned the strain to capsule production (Fig. 2C). These data are consistent with the involvement of cexA in the transport of the P. multocida capsular polysaccharide.

It has previously been hypothesized that the P. multocida capsule is a virulence determinant, since spontaneous unencapsulated strains are less virulent (15) and more sensitive to complement-mediated killing (31) than encapsulated strains. However, to date no isogenic strains have been available to unequivocally demonstrate this. We infected mice with various doses of P. multocida M1404, PBA875, or PBA1514 and observed that PBA875 was significantly less virulent than either the wild-type or complemented strain. The ID50 of PBA875 was approximately 106-fold higher than that of P. multocida M1404 or PBA1514. At very high doses (>8 × 105), PBA875 was capable of lethal infection, and bacteria isolated from mice which succumbed to challenge at these doses were shown to be acapsular.

The numbers of PBA1514 or PBA875 bacteria in various organs of mice were determined at 1, 4, 24, and 48 h after i.p. challenge. The numbers of PBA1514 organisms rose rapidly in all organs, reaching approximately 107 to 108 CFU/organ at the time of death. In contrast, PBA875 was shown to be removed rapidly from the body, with no bacteria being detected in any of the organs after 1 h. These data indicate that the reduced virulence of PBA875 was due to its rapid removal from the body after infection. It appears likely that at very high infective doses, the animals could not clear even the acapsular mutant faster than it was capable of replicating, and this may account for the virulence of PBA875 observed at doses of >8 × 105 CFU.

Two mechanisms have been suggested for the enhanced sensitivity of acapsular bacteria to removal from the blood: (i) increased sensitivity to the bactericidal activity of complement (10, 31, 37) and (ii) increased susceptibility to phagocytosis (1, 11, 19, 30). The acapsular strain PBA875 was shown to be significantly more sensitive to phagocytosis, with four- to sixfold more PBA875 organisms internalized by mouse peritoneal macrophages than was found with either P. multocida M1404 or PBA1514. Acapsular bacteria were still capable of surviving within the macrophages for at least 30 min. Furthermore, the average number of macrophages observed to contain PBA875 was seven times greater than that observed for P. multocida M1404. Interestingly, all strains were shown to be equally resistant to the bactericidal activity of complement in either bovine or murine serum and to grow at similar rates in both sera. Therefore, we believe that the rapid reduction in the number of PBA875 organisms in the organs after infection is primarily due to increased sensitivity to phagocytosis.

Taken together, these data provide for the first time unequivocal proof that the capsule is a major virulence factor in P. multocida. The reduction in virulence is due primarily to the rapid removal of the acapsular bacteria from the blood and other organs, and this removal is likely due to an increased susceptibility to phagocytosis. In other species, attenuated organisms have shown potential as vaccine candidates (13, 28), and work is in progress to determine if these attenuated acapsular P. multocida mutants are capable of conferring a protective immune response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vicki Vallance and Ian McPherson for excellent technical assistance and Sean Moore and Scott Chandry for slide scans and minor digital manipulation.

This work was funded in part by project grants from the Australian Research Council, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, and the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson L C, Rush H G, Glorioso J C. Strain differences in the susceptibility and resistance of Pasteurella multocida to phagocytosis and killing by rabbit polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Am J Vet Res. 1984;45:1193–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce J D, Chung J Y, Adler B. Genetic organisation of the capsule biosynthetic locus of Pasteurella multocida M1404 (B:2) Vet Microbiol. 2000;72:121–134. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter G R. Pasteurellosis: Pasteurella multocida and Pasteurella hemolytica. Adv Vet Sci. 1967;11:321–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catlin B W, Tartagni V R. Delayed multiplication of newly capsulated transformants of Haemophilus influenzae detected by immunofluorescence. J Gen Microbiol. 1969;56:387–401. doi: 10.1099/00221287-56-3-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chae C H, Gentry M J, Confer A W, Anderson G A. Resistance to host immune defense mechanisms afforded by capsular material of Pasteurella haemolytica, serotype 1. Vet Microbiol. 1990;25:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang Y C, Penoyer L A, Kwon-Chung K J. The second capsule gene of Cryptococcus neoformans, CAP64, is essential for virulence. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1977–1983. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1977-1983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Favre-Bonte S, Joly B, Forestier C. Consequences of reduction of Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule expression on interactions of this bacterium with epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:554–561. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.554-561.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen L M, Hirsh D C. Serum resistance is correlated with encapsulation of avian strains of Pasteurella multocida. Vet Microbiol. 1989;21:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(89)90030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmon B G, Glisson J R, Latimer K S, Steffens W L, Nunnally J C. Resistance of Pasteurella multocida A:3,4 to phagocytosis by turkey macrophages and heterophils. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:1507–1511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homchampa P, Strugnell R A, Adler B. Cross protective immunity conferred by a marker-free aroA mutant of Pasteurella multocida. Vaccine. 1997;15:203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inzana T J, Todd J, Veit H P. Safety, stability, and efficacy of noncapsulated mutants of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae for use in live vaccines. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1682–1686. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1682-1686.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jablonski L, Sriranganathan N, Boyle S M, Carter G R. Conditions for transformation of Pasteurella multocida by electroporation. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90066-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacques M, Kobisch M, Bélanger M, Dugal F. Virulence of capsulated and noncapsulated isolates of Pasteurella multocida and their adherence to porcine respiratory tract cells and mucus. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4785–4792. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4785-4792.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim K S, Kang J H, Cross A S. The role of capsular antigens in serum resistance and in vivo virulence of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;35:275–278. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroll J S, Hopkins I, Moxon E R. Capsule loss in H. influenzae type b occurs by recombination-mediated disruption of a gene essential for polysaccharide export. Cell. 1988;53:347–356. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroll J S, Loynds B, Brophy L N, Moxon E R. The bex locus in encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae: a chromosomal region involved in capsule polysaccharide export. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1853–1862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maheswaran S K, Thies E S. Influence of encapsulation on phagocytosis of Pasteurella multocida by bovine neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1979;26:76–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.1.76-81.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moxon E R, Deich R A, Connelly C. Cloning of chromosomal DNA from Haemophilus influenzae. Its use for studying the expression of type b capsule and virulence. J Clin Investig. 1984;73:298–306. doi: 10.1172/JCI111214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muniandy N, Edgar J, Woolcock J B, Mukkur T K S. Virulence, purification, structure and protective potential of the putative capsular polysaccharide of Pasteurella multocida type 6:B. In: Patten B E, Spencer T L, Johnson R B, Hoffmann H D, Lehane L, editors. The international workshop on pasteurellosis in production animals. Bali, Indonesia: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research; 1992. pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsson I-M, Lee J C, Bremell T, Rydén C, Tarkowski A. The role of staphylococcal polysaccharide microcapsule expression in septicemia and septic arthritis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4216–4221. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4216-4221.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pigeon R P, Silver R P. Topological and mutational analysis of KpsM, the hydrophobic component of the ABC-transporter involved in the export of polysialic acid in Escherichia coli K1. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:871–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramdani B, Adler Opsonic monoclonal antibodies against lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antigens of Pasteurella multocida and the role of LPS in immunity. Vet Microbiol. 1991;26:335–347. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90027-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramdani . Studies on pathogenesis and immunochemistry of Pasteurella multocida model infection in mice. Ph.D. thesis. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University Melbourne; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rimler R B, Rhoades K R. Serogroup F, a new capsule serogroup of Pasteurella multocida. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:615–618. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.4.615-618.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts I S. The biochemistry and genetics of capsular polysaccharide production in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:285–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimoji Y, Mori Y, Sekizaki T, Shibahara T, Yokomizo Y. Construction and vaccine potential of acapsular mutants of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: use of excision of Tn916 to inactivate a target gene. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3250–3254. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3250-3254.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimoji Y, Yokomizo Y, Sekizaki T, Mori Y, Kubo M. Presence of a capsule in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae and its relationship to virulence for mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2806–2810. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2806-2810.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith H E, Damman M, van der Velde J, Wagenaar F, Wisselink H J, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Smits M A. Identification and characterization of the cps locus of Streptococcus suis serotype 2: the capsule protects against phagocytosis and is an important virulence factor. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1750–1756. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1750-1756.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snipes K P, Hirsh D C. Association of complement sensitivity with virulence of Pasteurella multocida isolated from turkeys. Avian Dis. 1986;30:500–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thakker M, Park J-S, Carey V, Lee J C. Staphylococcus aureus serotype 5 capsular polysaccharide is antiphagocytic and enhances bacterial virulence in a murine bacteremia model. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5183–5189. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5183-5189.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tu V, Adler B, Faine S. The role of macrophages in the protection of mice against leptospirosis: in vitro and in vivo studies. Pathology. 1982;14:463–468. doi: 10.3109/00313028209092128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward C K, Lawrence M L, Veit H P, Inzana T J. Cloning and mutagenesis of a serotype-specific DNA region involved in encapsulation and virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5a: concomitant expression of serotype 5a and 1 capsular polysaccharides in recombinant A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3326–3336. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3326-3336.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wessels M R, Goldberg J B, Moses A E, DiCesare T J. Effects on virulence of mutations in a locus essential for hyaluronic acid capsule expression in group A streptococci. Infect Immun. 1994;62:433–441. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.433-441.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright A C, Simpson L M, Oliver J D, Morris J G., Jr Phenotypic evaluation of acapsular transposon mutants of Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1769–1773. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1769-1773.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuppardo A B, Siebeling R J. An epimerase gene essential for capsule synthesis in Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2601–2606. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2601-2606.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]