Abstract

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, telehealth expanded rapidly and was adopted as a substitute for in-person patient and nurse visits. However, no studies have mapped nurse-led telehealth interventions during the pandemic. This study aimed to identify and summarize the strengths and weaknesses of nurse-led telehealth interventions for community-dwelling outpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study used a scoping review methodology and was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Scoping Review Extension. Five electronic databases were searched to find studies published in English peer-reviewed publications between January 2020 and February 2022. A total of 490 articles were retrieved, of which 23 empirical studies were selected based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Primary studies from nine countries with a variety of research designs were included. Four strengths and three weaknesses of nurse-led telehealth interventions for patients during COVID-19 were identified. For telehealth services to provide effective, efficient, and quality patient care, future research and nursing practice need to overcome the identified weaknesses of current nurse-led telehealth interventions. More rigorous evidence-based research and updated and standardized guidelines for nurses' telehealth services will help improve the quality of patient care. Nurse managers, leaders, and policymakers can use the findings of this scoping review to refine the current telehealth services system.

KEY WORDS: COVID-19, Nurse, Nurse practitioner, Review, Scoping review, Telehealth

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, or COVID-19, has caused severe illnesses and numerous deaths on a global scale.1 During the pandemic, the unprepared public healthcare systems were tested and damaged by an unprecedented health emergency.2

Nurses account for the largest healthcare professional population in the world. These frontline workers conduct primary assessments of patients and spend time caring for patients.1,3 Because of the high risk of COVID-19, telehealth has expanded as a promising substitute for face-to-face consultations.4 Correspondingly, nurses-led telehealth services in patient care are also expanding globally and have become more crucial since the onset of COVID-19 as a result of its significant impact on the healthcare system.5

Telehealth intervention is “any intervention in which clinical information is transferred remotely between patient and healthcare provider, regardless of the technology used to record or transmit the information.”6(p3) Telehealth has three modalities: synchronous (eg, real-time virtual visits), asynchronous (store and forward messages), and remote patient monitoring.7

In 2021, the World Health Organization made many recommendations on telehealth services4; numerous studies of telehealth services and their effectiveness with regard to patient outcomes have been conducted and published.8–10 Several systematic reviews from disciplines unrelated to nursing have shown the effectiveness of telehealth during the pandemic.11,12

However, empirical studies on the effects of nurse-led and -managed telehealth services on patients are limited.13,14 Furthermore, no review has provided a comprehensive overview of nurse-led telehealth interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS

Aim

This scoping review aimed to identify the strengths and weaknesses of nurse-led telehealth interventions for the care of community-dwelling outpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The specific research questions are as follows: (1) What are the characteristics of nurse-led telehealth interventions since the outbreak of COVID-19?; and (2) What are the strengths or weaknesses of nurse-led telehealth interventions implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic? To focus on the evidence related to the pandemic, this scoping review was limited to studies published between January 2020 (when the World Health Organization announced that COVID-19 is to be regarded as the highest alarm to public health) and February 10, 2022 (when the research was conducted).

Study Design

This review was guided by the Arksey and O'Malley15 framework for a scoping review. A scoping review aims to “examine the extent, range, and nature of research activity,”15(p21) to research a specific topic, identify current knowledge gaps, and provide implications future research, practice, and health policy.16 Unlike systematic reviews, a scoping review is not searching for a new finding about an intervention's effectiveness; instead, it provides a broad overview of literature.16 According to Arksey and O'Malley,15 scoping reviews have five steps: (1) identify the research question; (2) identify relevant articles from multiple databases; (3) select articles based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria; (4) chart and summarize data; and (5) analyze, synthesize, and report results of findings.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Scoping Review Extension statement also guided this review.17

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This scoping review selected studies based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) interventions were led by nurses, nurse practitioners (NPs), or nurse midwives during the COVID-19 pandemic and used telehealth modalities; (2) studies were designed as primary and empirical studies documenting interventions that will be implemented in the treatment of COVID-19 that were implemented as nurse-led telehealth interventions or research protocols; (3) study participants include patients (including caregivers) or nurses, NPs, or nurse midwives working in health-services sites; and (4) studies were published in an English-language journal between January 31, 2020, and February 10, 2022, including advance publications.

Editorials, policy papers, and commentaries that were not empirical studies were excluded. Studies that did not describe or did not include telehealth interventions as a main health intervention and studies that included interventions not conducted by nurses as primary healthcare practitioners were excluded. Studies that were targeted to nursing students, included diseases other than COVID-19 (including Coronavirus variants), and did not meet the aim of this review were also excluded. Supplemental Digital Content 1 (http://links.lww.com/CIN/A203) summarized the inclusion and exclusion criteria of this review.

Search Strategies

Literature searches were conducted in CINAHL, Ovid, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. These databases were searched using the following key terms with Boolean operators: (telehealth) OR (technology) OR (telemedicine) OR (telehealth assisted) AND (nurse) OR (nurse practitioner) OR (nurse midwives) OR (patient) OR (outpatient) OR (community) AND (COVID-19) OR (SARS-CoV-2). The following additional search terms were also used: (intervention) OR (service) OR (eHealth) OR (mHealth) OR (Internet) OR (online). Research that was published between January 31, 2022, and February 10, 2022, was collected. This review study also used snowball techniques with citations and reference list tracking from the initial search.

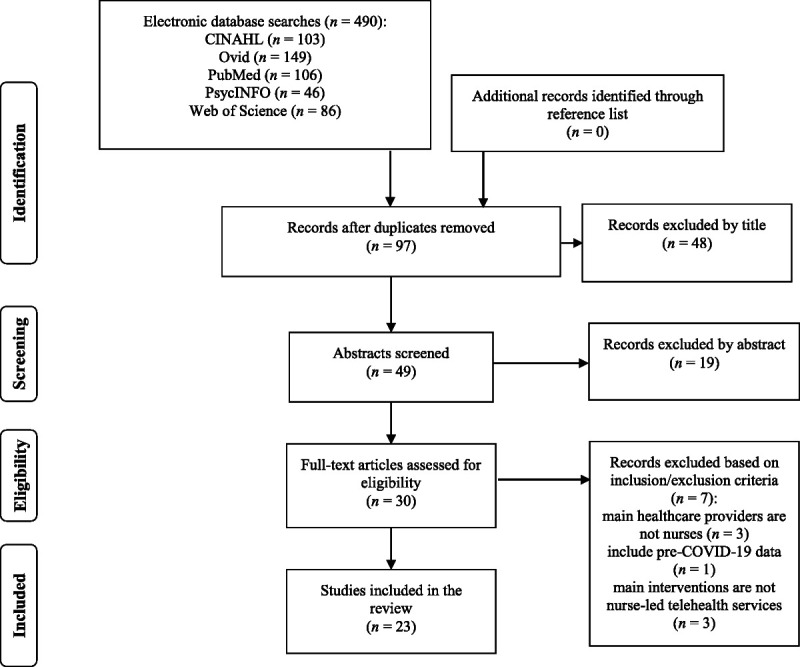

The initial search yielded 490 articles. No additional records or articles were identified from citations or reference lists. Duplicates were removed using EndNote X9 (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA), leaving 97 articles. Title review excluded 48 of these, and abstract review excluded an additional 19 because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or because they did not meet the aim or research questions of this review. The full texts of the 30 remaining articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, seven additional studies were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria; for example, interventions were not mainly led by nurses. A total of 23 articles were included in the scoping review.18–40Figure 1 presents this scoping review study screening process.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses flow diagram of the selection process.

The initial search was conducted on February 11, 2022, by the primary researcher and the librarian who is qualified to search electronic databases. A confirmation search was done on February 22, 2022, by the research assistant who is a professor emeritus in nursing checked and confirmed the search. A quality appraisal of the 23 included studies was not conducted because a scoping review does not require a quality assessment; instead, the methodology aims to map and find gaps in the existing articles.15

Data Charting and Management

A table was created to extract the following data from the included studies: author(s), publication year, country where the study was conducted or developed, study design, study purpose, sample, short description of nurse-led telehealth intervention, modality of telehealth intervention, theoretical model, and major results. The researcher extracted the data and independently checked the table for accuracy and to ensure consistency. During the tabulated table-charting process, key terms and codes were captured.15 These codes were collected and synthesized as themes, and these themes were categorized into strengths or weaknesses. All the data charting, coding, and thematic synthesis process was checked and confirmed to increase the trustworthiness of the research method.15 Both the researcher and the research assistant reached consensus on the themes as the results. Table 1 presents these themes with quotations from the included studies.

Table 1.

Themes in Selected Texts

| Theme | Relevant Study Quotation | |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Care provided without transmitting COVID-19 | “Almost half of the participants (n = 16, 47.1%,) stated they felt safer with the Virtual Nurse Visit”19(p107) “The monitoring program helped to ensure safe cancer care pathways during this period by avoiding unnecessary visits to the hospital while ensuring the monitoring of symptoms”24(p7) “The advantages of healthcare at a distance are seen in the protection of midwives as well as pregnant women, women who have recently given birth, and their families from COVID-19 infection”25(p4) “The reduction of contact time in hospital limited exposure of both healthcare providers and patients to potential risk for infection…. Feedback from adolescents and parents suggested that spending less time in the hospital greatly reduced their anxiety around contracting COVID-19”13(p617) “The majority were appreciative of the option for telemedicine and described it as a means of continuing communication and connection while also limiting potential exposures to COVID-19”38(p38) |

| Increased access to healthcare | “Nurse navigators were able to identify vulnerabilities and implement preventive measures”24(p7) “Telehealth WOC nursing services also benefit patients in the community setting who cannot easily be transported to her clinic”30(p441) “Due to the preventive measures of lockdown, which have made accessibility to our services difficult, the use of telemedicine resources has been promoted”32(p485) “The current global pandemic and state mandate on social distancing further amplify this disparity. The national epidemic of chronic pain and the immediate need to enhance the care of vulnerable patients required a timely implementation of telehealth delivered programming that can enhance the quality of life for the local populations”33(p9) “As a part of implementing robust telehealth practices, promoting health equity for all patients and families was of primary importance”36(p2) “During the study, period there were 21 610 completed on-demand telehealth visits and 1852 patients for whom there were left without being seen attempted follow-ups”37(p1) |

|

| Patient-centered and continuous care | “In the healthcare context, telehealth has proved an important tool in enabling continuity in healthcare, especially during emergent and widespread pandemic conditions”20(p633) “They (nurse navigators) provided personalized care to the patients by managing the course of COVID-19 symptoms and contributed to a global approach in patient management”24(p7) “The advantages of healthcare at a distance are associated with maintaining care/counseling in an exceptional situation”25(p4) “It (electronic medical records) eliminates difficulties finding notes and ensures continuity of care”26(p5) “…telemedicine has served to bridge the need for continuity of care of patients during COVID-19 pandemic, especially in the management of chronic diseases”13(p617) “Continuing virtual forms of education, activities, and socialization even as pandemic restrictions lift, could be beneficial to children with chronic conditions”38(p6) |

|

| Increased satisfaction among patients and nurses | “All participants (100%, n = 34) expressed that they were satisfied (agreed or strongly agreed) with the ability to see and talk to their nurse during the virtual nurse visits”19(p105) “Ninety-one percent of patients from the COVID-19 response programs reported that the program ‘helped them to know what to do next,’ and 96.7% of patients indicated they would recommend the program (agree/strongly agree)”21(p233) “…including parental comments, support that the majority of families were highly satisfied with their telehealth encounter and that this was an effective strategy to address most patient needs during the pandemic”22(p40) “The clinical team is satisfied that it is clinically appropriate to manage the patient at home and a caregiver can safely provide care to the patient with appropriate personal protective equipment, or the patient can provide care to himself/herself, and a member of the clinical team carries out daily monitoring and follow-up evaluation27(p4) “The team concluded that Pain Coping Skills Training is a viable and effective intervention that NPs can deliver to enhance self-efficacy for osteoarthritis patients”33(pp.7–8) “Other nurse practitioners mentioned greater patient satisfaction with virtual visits (eg, ‘patients love it’), increased accessibility and ease of communication. Some nurse practitioners also liked virtual visits”34(p5) “Both the adolescents and parents reported that telehealth was similar (80%) to in-person clinic, and 20% reported superior to the in-person clinics. Sixty five percent of the adolescents and 67% of parents would continue to use this telehealthcare with the APN”13(p4) |

|

| Weaknesses | Absence of evidence-based telehealth guidelines for treating COVID-19 | “Since the pandemic, Sue (nurse practitioner) has been challenged with rapidly adapting her practice from a traditional direct care model to a blended practice offering telehealth services”29(p441) “Guidelines for WOC telehealth nursing care need to be developed to provide structure to practice and improve patient safety”29(p442) “While several medications are beneficial, achieving optimal guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) is challenging. COVID-19 created a need to explore new ways to deliver care”30(p77) “Protocols and educational tools will need to be developed to ensure that high-quality telehealth is delivered appropriately”34(p6) “However, across these guidelines was the failure to address specific considerations in conducting telehealth with underresourced patients and families or those that have low levels of health or technological literacy”36(p2) |

| Technical issues | “Participants also reported various challenges with accessing their Zoom session due to the requirement of inputting numerical passcodes to enter the secured virtual nurse visit”19(p107) “Technology challenges were faced not only by our team but also by the patients themselves because some areas were impoverished or rural with limited Internet connectivity, and others did not have a telephone or email account and thus were challenged to access and understand the digital solutions provided21(p234) “Similarly, families who reported audio, visual, or connectivity issues were sometimes accepting of technological barriers because of COVID-19”22(p39) “Among the 46 participants, 11 (24%) sent an email and two participants (4%) made a phone call for technical assistance”31(p5) “Some (nurse practitioners) relayed concerns for specific patient populations whose care may be less compatible with telehealth”34(p5) |

|

| Challenges of physical and psychological care | “Concerns ranged from the accuracy of the objective data taken in a home setting to the capacity of a provider to adequately assess a patient via video”22(p38) “We experienced barriers when obtaining photographs of wounds for patients in strict isolation due to COVID-19. For example, this patient was admitted to our newly created COVID-19 hospital, where there were remote cameras available, which were not functioning to their full capacity, rendering it difficult to obtain clear images of the medical device–related pressure injuries caused by prolonged prone positioning”23(p454) “Studies comparing in-person and videoconferencing encounters have found that providers use less empathetic, supportive, and facilitating statements in virtual encounters, and there is less information exchange, with the presentation of fewer problems”28(p2) “For example, the WOC nurse is not able to establish the level of rapport with a patient that occurs during physical visits to the patient's home, palpate or smell the wound, or watch the patient with an ostomy perform a pouch change”29(p440) “(nurse mentioned), loss of face time with patients and team members, as well as the challenges to physical assessments and diagnosis”34(p5) “Several health services offered in the face-to-face care model, including physical assessment and point of care lab testing, are not available in telehealth”14(p3) |

Abbreviations: APN, advanced practice nurse; WOC, wound, ostomy, and continence.

RESULTS

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Supplemental Digital Content 2 (http://links.lww.com/CIN/A204), and the details are presented in Supplemental Digital Content 3 (http://links.lww.com/CIN/A205). All the studies were published in English in peer-reviewed clinical journals between 2020 and 2022. Two of these studies were in the preprint status at the time of this review.25,34 The 23 studies were based in nine countries: the United States (n = 14), Australia (n = 2), and Canada, France, Ireland, New Zealand, Singapore, Spain, and Switzerland (all n = 1). All included studies were empirical studies encompassing a variety of designs (including qualitative, mixed-methods, case, pilot, quasi-experimental, and descriptive studies) (Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/CIN/A205).

The study participants were community-dwelling outpatients who provided care via a telehealth system. The patients included youth, adults, and the elderly. Eighteen studies targeted patients with diseases such as heart failure, cancer, diabetes, and chronic pain or patients with disabilities who were living or staying in their homes or long-term care facilities, of which three were diagnosed with COVID-19.24,27,31 Three studies included parents who cared for their children. Five studies sampled nurses, NPs, or nurse-midwives.

Nurse-Led Telehealth Interventions During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Three of the studies demonstrated intervention protocols for telehealth services during COVID-19.14,18,28 Twenty studies assessed either the effectiveness or experiences of nurse-led telehealth interventions for patients or nurses (including NPs) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study interventions included healthcare services through telehealth devices and virtual visits, disease management, physical assessment through PC monitors and Web cameras, consultations, and follow-up services. Nurse-led telehealth service modalities included combined synchronous and remote patient monitoring, meaning that nurses visited patients virtually, including teleconferencing via telehealth applications or software such as Zoom, for health assessment or consultation. Some studies have used asynchronous delivery modes, including regular follow-up calls, text messages, and emails (Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/CIN/A205). Five studies adopted and applied a theoretical framework for their studies.19,20,22,35,36

In these studies, nurse-led telehealth services were provided for special cases. For example, for patients who have an ostomy and need wound care, wound care management was provided by NPs to assist patients in performing self-care through virtual consultation.23,29 Many telehealth services were targeted at patients with chronic conditions or those infected with COVID-19, and two studies provided telehealth to isolated patients and facility residents to reduce their anxiety.18,35

More than half of the studies were conducted between February 2020 and March 2021. Nine studies began their research in March 2020. One protocol description study indicated that they planned to collect data in the summer of 2021. Eight studies did not clearly report the date of intervention or data collection.

Strengths of Nurse-Led Telehealth Interventions During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Four strengths of nurse-led telehealth interventions were identified: (1) care provided without transmitting COVID-19; (2) increased access to healthcare; (3) patient-centered and continuous care; and (4) increased satisfaction among patients and nurses.

Care Provided Without Transmitting COVID-19

One strength of nurse-led telehealth interventions was the provision of care without transmitting COVID-19 to either patients or nurses themselves. Studies have shown that patients with chronic diseases are more vulnerable and frailer, making them more susceptible to COVID-19 infection.19,24 Thus, patients with oncological conditions had a reduced risk of COVID-19 transmission through telehealth interventions.38 Patients and their caregivers reported that spending less time in hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic, while also utilizing telemonitoring services with nurses, was an advantage of telehealth interventions.13,24,25 In one qualitative study, participants expressed that they appreciated the option of nurse-led telehealth intervention during the pandemic because the intervention limited their exposure to COVID-19.38

Increased Access to Healthcare

Studies have reported that COVID-19 has limited access to traditional healthcare services.31,32 However, studies also indicated that nurse-led telehealth interventions increased access to health services for patients who needed them.32,37 This increased access especially benefited vulnerable patients who are affected by healthcare disparities.24,30 Because of the pandemic's social distancing mandates, patients with limited mobility who needed transportation in the community were also provided with telehealth services and received timely care.24,32,33 Studies have demonstrated that telehealth interventions increase the possibility that health disparities may be reduced among vulnerable populations and thus may promote health equity.30,36

Patient-Centered and Continuous Care

In some studies, nurses provided personalized healthcare through virtual visits and telemonitoring.20,24 For example, nurses monitored COVID-19 patients with cancer via telehealth monitoring systems, considered their current treatment of care, and provided information based on patients' understanding.20 Several studies have reported that telehealth interventions offer continuity-of-care advantages.13,25,38 Even when social isolation was mandated, nurses could navigate patients' symptoms, thereby reducing the absence of continuous care and making it possible to both increase patients' quality of healthcare and significantly reduce their emergency department visits.26

Increased Satisfaction Among Patients and Nurses

Many studies have emphasized that the implementation of nurse-led telehealth interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic has increased patient and nurse satisfaction.13,19,21 Patients also reported that they learned coping skills and had opportunities to talk with nurses despite social distancing and social isolation.19,33 In the study by Lim et al,13 80% of patients said that virtual nurses' visits were similar to in-person clinic visits. Moreover, they are willing to continue using telehealth services with NPs.13

In these studies, nurses and NPs also reported increased satisfaction with virtual visits and remote patient monitoring.33,34 They explained that they could deliver care appropriately through telehealth modalities, even during the pandemic.27,33 During lockdowns, nurses could still educate patients and their caregivers about effective disease management strategies through virtual visits.22,27

Weaknesses of Nurse-Led Telehealth Interventions During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Three weaknesses of nurse-led telehealth interventions were identified: (1) absence of evidence-based telehealth guidelines for treating COVID-19; (2) technical issues; and (3) challenges in physical and psychological care.

Absence of Evidence-Based Telehealth Guidelines for Treating COVID-19

None of the included studies reported the use of telehealth guidelines during COVID-19. Several studies have reported a lack of practical guidelines.29,30 In Mahoney's study,29 one NP was challenged to rapidly adopt a new telehealth practice without guidelines. This NP tried to blend traditional and telehealth services themselves.29 Other studies have reported that although there are guidelines for treating patients with chronic illnesses, these guidelines are insufficient to address all telehealth issues.34,36 Studies have suggested that standardized and structured practical guidelines for nurses are related to patient safety and the quality of patient outcomes.29,34

Technical Issues

Many studies have reported the technical challenges experienced by both patients and nurses while implementing telehealth interventions. Patients had difficulty using mobile or PC devices in telehealth sessions.19,31 Some patients reported that they contacted nurses not for healthcare issues but for technical assistance.31 During exit surveys for one telehealth intervention, patients reported barriers, such as limited Internet connectivity or getting disconnected during virtual visits.21 In some studies, nurses expressed concern for patients, such as the elderly, who were not accustomed to using telehealth devices.19,34

Challenges of Physical and Psychological Care

Some studies have reported that nurses face difficulty in conducting physical assessments and establishing psychological rapport.14,22,23,28,34 Many observed issues regarding nurses' accuracy in physical assessments and diagnoses. For example, many nurses reported unclear or inaccurate objective data obtained using a Web camera during virtual visits or using uploaded photographs taken and uploaded by patients.22,23,34 A nurse in the study by Mahoney29 described difficulties in providing emotional care through virtual conferencing. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients experienced social isolation—all countries were shut down—so they expected an increased level of emotional support from nurses.29,34 However, telehealth interventions, especially asynchronous modes of care delivery, limit nurses' abilities to establish rapport with patients.29

DISCUSSION

Telehealth has been one of the most highlighted, expanded, and pivotal strategies for delivering healthcare services during COVID-19. This scoping review aimed to identify, collate, and synthesize research evidence on nurse-led telehealth interventions developed for or conducted on patients during COVID-19. The study found 23 studies published between 2020 and 2022. This is the first scoping review to address the strengths and weaknesses of nurse-led telehealth interventions during a pandemic.

A variety of telehealth interventions led by nurses and NPs have been attempted or designed to provide effective and efficient healthcare to patients during the pandemic. The four strengths of nurse-led telehealth interventions identified in this review were as follows: (1) care provided without transmitting COVID-19; (2) increased access to healthcare; (3) continuous and patient-centered care; and (4) increased satisfaction among patients and nurses. The first strength revealed that telehealth services are useful and provide health security to both nurses and patients. In previous acute respiratory epidemics, such as the SARS or MERS outbreaks, home-based online healthcare services were the way to protect healthcare providers and patients from virus transmission.39 In fact, the US Department of Health and Human Services encouraged providers to adopt telehealth during COVID-19 for safety's sake.40 The first strength revealed in this review aligns with evidence from previous studies that telehealth services are a safe and effective means of coordinating care and reducing disease transmission.

The second strength of this scoping review was that nurse-led telehealth interventions increased patients' access to healthcare. Indeed, the interventions even reduced the rate of health disparities, suggesting that such interventions could be useful for all populations.36 The most significant issue during COVID-19 was the increased risk of exposure to the virus for vulnerable populations.41 Factors such as income, geographic region, racial/ethnic minority status, and age are signs of vulnerability and health disparities that may indicate disadvantages in accessing healthcare systems.41 This scoping review revealed that telehealth with nurses' care services offers broad access to patients and suggests that it may help reduce health disparities.

The third strength is that nurse-led telehealth provides continuous and patient-centered care, which is imperative for patients with chronic illnesses,42 such as cancer patients in the study by Ferrua et al.24 In this review, studies implemented personalized care through telemonitoring by nurses based on patient symptoms. The two touted benefits of telehealth services are in-person care and continuous patient monitoring.43,44 Finally, this review identified increased satisfaction among patients and nurses as strength of telehealth services. This finding is aligned with a previous review; the association between telehealth services and patient satisfaction is a key indicator of patient outcomes.45

This scoping review highlights three weaknesses of nurse-led telehealth interventions: (1) absence of evidence-based guidelines; (2) technical issues; and (3) challenges of physical and psychological care. Although these weaknesses represent barriers to the current public health crisis, they also have several implications for research, practice, and health policymaking.

First, empirical and practical guidelines for nurses should be prepared for telehealth services. Public health has experienced several pandemic outbreaks in recent years, including SARS, MERS, and H1N1; however, these outbreaks were less deadly worldwide than COVID-19. However, the guidelines and standards of practice for nurses and other healthcare professionals are limited.3,46 Thus, nurses failed to adhere to these guidelines.46 This review also identified that limited guidelines for telehealth practice were susceptible to rapid information changes related to COVID-19. Missing or rapidly changing guidelines are likely to cause nurses to experience difficulties and feel stress.3,29 Thus, evidence should be synthesized, and telehealth delivery models should be prepared to improve nurses' practice and create standard guidelines for COVID-19. Moreover, it is also imperative to develop guidelines for telehealth or for pandemics in general, both for current frontline nurses and nursing students.

Furthermore, this scoping review identified some technical challenges. These findings align with previous research on telehealth services by other healthcare practitioners.47,48 For example, the review identified regions and populations with limited access to telehealth devices; both patients and nurses had a limited ability to utilize telehealth modalities. The selected studies also observed nurses and patients who preferred traditional examinations and had difficulties performing telehealth services. Practical training in Internet use and technological skills is recommended for future research and practice. Nurses and nursing educators should receive periodic education to prepare them adequately for such practices.

In this review, five of the included studies adopted a theoretical framework.19,20,22,35,36 No studies have developed or expanded the theoretical model of telehealth services. Relevant theoretical frameworks can be strengthened to create sustainable interventions as care strategies.49

This review has several strengths. This is the first scoping review to summarize and provide evidence on nurse-led telehealth interventions during COVID-19. The results of this review can be used to help both nurses and healthcare leaders during the ongoing pandemic and prepare for future pandemics. This study applied the framework of Arksey and O'Malley15 to ensure the clarity of review and provide comprehensive evidence. This scoping review identified and synthesized evidence from research to highlight practical implications for telehealth services by nurses, who have been the primary healthcare providers during COVID-19.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this scoping review. First, this review included only studies conducted in nine developed countries (Australia, Canada, France, Ireland, New Zealand, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States); and more than half of these studies were conducted in the United States. Therefore, the results of this review may not be generalizable for the healthcare systems of other countries in the world. In particular, there are differences between the telehealth systems in developed and developing countries. Second, this review included only studies published in English. COVID-19 pandemic is a global public health emergency, and there is research from journals in languages other than English that might have uncovered more information on the telehealth services led by nurses. Third, this review included nurses, NPs, and nurse midwives without considering their work experience or educational levels. Fourth, this review included patients of all ages and was not limited to specific diagnosed disease groups. In addition, this review included only community-dwelling patients and excluded inpatients at hospitals. Fifth, this review did not clearly distinguish patients with diagnosed diseases from those with COVID-19 symptoms. Finally, the literature search and databases used in this review might not have captured all studies examining nurse-led telehealth interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implications for Nursing and Health Policy

Nurse managers and leaders should support and fund both telehealth services and research to find the best evidence-based practices and develop guidelines for telehealth interventions. The shortage of research funding impedes the improvement and adoption of telehealth services.5 Moreover, some countries still have limited readiness for or are conservative about utilizing telehealth services.1,5,50 In these countries, healthcare leaders and policymakers should construct systems and develop infrastructure for telehealth services. In the United States, healthcare policy changed to fund in-person and telehealth visits as of March 6, 2020, and during the COVID-19 pandemic.5 However, many other countries remain vague in terms of reimbursing nurses' telehealth services and have been conservative in adopting telehealth visits as a substitute for in-person clinic visits.50 Healthcare policymakers and nurse leaders in these countries need to allow the expansion of telehealth services' reimbursements for nurses.

Finally, healthcare leaders and organizations such as the World Health Organization should consider collaborating internationally to develop guidelines and practices relevant to telehealth services. Moreover, developing such guidelines is important to prepare for future epidemics and pandemics.

CONCLUSION

This is the first scoping review to survey nurse-led telehealth interventions for COVID-19 patients. It highlights the strengths and weaknesses of nurses' telehealth practices. Globally, telehealth has become an increasingly valuable care strategy and accepted instrument for providing efficient and effective care. From the studies included in this review, telehealth interventions by nurses revealed the tremendous benefits of this alternative care during the pandemic. Therefore, global healthcare leaders should support and broadly adopt telehealth services to improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge thoughtful support of Gachon University in the preparation of this article. The author thanks Dr Hae-kyung Lee (professor emeritus) for her work in data extraction and supervision of this study.

Footnotes

The author has disclosed that she has no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.cinjournal.com).

References

- 1.Jackson D Bradbury-Jones C Baptiste D, et al. Life in the pandemic: some reflections on nursing in the context of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(13–14): 2041–2043. 10.1111/jocn.15257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Listings of WHO's Response to COVID-19. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline. Updated January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joo JY, Liu F. Nurses' barriers to caring for patients with COVID-19: a qualitative systematic review. International Nursing Review. 2021;68(2): 202–213. https://doi:10.1111/inr.12648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Implementing Telemedicine Services During COVID-19: Guiding Principles and Considerations for a Stepwise Approach. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336862/WPR-DSE-2020-032-eng.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y. Updated May 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frey MB, Chiu SH. Considerations when using telemedicine as the advanced practice registered nurse. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2021;17(3): 289–292. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanlon P Daines L Campbell C, et al. Telehealth interventions to support self-management of long-term conditions: a systematic metareview of diabetes, heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(5): e172. 10.2196/jmir.6688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Using Telehealth to Expand Access to Essential Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html. Updated June 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghai B, Malhotra N, Bajwa SJS. Telemedicine for chronic pain management during COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020;64(6): 456–462. https://doi:10.4103/ija.IJA_652_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krenitsky NM, Spiegelman J, Sutton D, Syeda S, Moroz L. Primed for a pandemic: implementation of telehealth outpatient monitoring for women with mild COVID-19. Seminars in Perinatology. 2020;44(7): 151285. https://doi:10.1016/j.semperi.2020.151285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J Hamadi HY Hicks-Roof KK, et al. Healthcare professionals and telehealth usability during COVID-19. Telehealth Medicine Today. 2021;6(3). 10.30953/tmt.v6.270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garfan S Alamoodi AH Zaidan BB, et al. Telehealth utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2021;138: 104878. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1): 1193. https://doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim ST, Yap F, Chin X. Bridging the needs of adolescent diabetes care during COVID-19: a nurse-led telehealth initiative. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(4): 615–617. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutter R, Cuellar AE, Harvey M, Hong YA. Academic nurse-managed community clinics transitioning to telehealth: case report on the rapid response to COVID-19. JMIR Nursing. 2020;3(1): e24521. https://doi:10.2196/24521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1): 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cacchione PZ. The evolving methodology of scoping reviews. Clinical Nursing Research. 2016;25(2): 115–119. https://doi:10.1177/1054773816637493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7): 467–473. https://doi:10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Archbald-Pannone LR Harris DA Albero K, et al. COVID-19 collaborative model for an academic hospital and long-term care facilities. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020;21(7): 939–942. http://doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birkhoff SD Nair JM Bald K, et al. Facilitators and challenges in the adoption of a virtual nurse visit in the home health setting. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2021;40(2): 105–120. https://doi:10.1080/01621424.2021.1906374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunelli VN, Beggs RL, Ehrlich CE. Case study discussion: the important partnership role of disability nurse navigators in the context of abrupt system changes because of COVID-19 pandemic. Collegian. 2021;28(6): 628–634. https://doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2021.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooling M Klein CJ Pierce LM, et al. Access to care: end-to-end digital response for COVID-19 care delivery. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2022;18(2): 232–235. https://doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dempsey CM Serino-Cipoletta JM Marinaccio BD, et al. Determining factors that influence parents' perceptions of telehealth provided in a pediatric gastroenterological practice: a quality improvement project. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2022;62: 36–42. 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engels D Austin M Doty S, et al. Broadening our bandwidth: a multiple case report of expanded use of telehealth technology to perform wound consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 2020;47(5): 450–455. https://doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrua M Mathivon D Duflot-Boukobza A, et al. Nurse navigators' telemonitoring for cancer patients with COVID-19: a French case study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2021;29(8): 4485–4492. 10.1007/s00520-020-05968-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gemperle M Grylka-Baeschlina S Klamroth-Marganska V, et al. Midwives' perception of advantages of health care at a distance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Switzerland. Midwifery. 2022;105: 103201. 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanrahan G Ennis C Conway M, et al. An evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of telephone triage in prioritizing patient visits to an ophthalmic emergency department—the impact of COVID-19 [published online October 19, 2021]. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2021;1–6. https://doi:10.1007/s11845-021-02806-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutchings OR Dearing C Jagers D, et al. Virtual health care for community management of patients with COVID-19 in Australia: observational cohort study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(3): e21064. https://doi:10.2196/21064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koppel PD, De Gagne JC. Exploring nurse and patient experiences of developing rapport during oncology ambulatory care videoconferencing visits: protocol for a qualitative study. JMIR Research Protocols. 2021;10(6): e27940. https://doi:10.2196/27940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahoney MF. Telehealth, telemedicine, and related technologic platforms: current practice and response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 2020;47(5): 439–444. https://doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLachlan A, Aldridge C, Morgan M, Lund M, Gabriel R, Malez V. An NP-led pilot telehealth programme to facilitate guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction during the COVID-19 pandemic. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2021;134(1538): 77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michaud A, Vadeboncoeur A, Cloutier L, Goupil R. The feasibility of home self-assessment of vital signs and symptoms: a new key to telehealth for individuals? [published online September 28, 2021]. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2021;155: 104602. https://doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarro-Correal E Borruel N Robles V, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the activity of advanced-practice nurses on a reference unit for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2021;44(7): 481–488. https://doi:10.1016/j.gastrohep.2020.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien M. Pain coping skills training un-locks patient-centered pain care during the COVID- 19 lockdown [published online November 11, 2021]. Pain Management Nursing. 2021;S1524-9042(21): 00237–X. https://doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2021.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Reilly-Jacob M, Perloff J, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh R, Flanagan J. Nurse practitioners' perception of temporary full practice authority during a COVID-19 surge: a qualitative study [published online November 23, 2022]. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2022;126: 104141. https://doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross L, Meier N. Improving adult coping with social isolation during COVID-19 in the community through nurse-led patient-centered telehealth teaching and listening interventions. Nursing Forum. 2021;56(2): 467–473. https://doi:10.1111/nuf.12552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serino-Cipoletta J, Dempsey C, Goldberg N. Telemedicine and health equity during COVID-19 in pediatric gastroenterology. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2022;36(2): 124–135. https://doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheridan MD, Adams KT, Booker E. Pilot assessment of an on-demand telehealth ‘left without being seen’ follow-up programme [published online January 21, 2021]. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. https://doi:10.1177/1357633X20983159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinberg DM, Andresen JA, Pahl DA, Licursi M, Rosenthal SL. “I've weathered really horrible storms long before this…”: the experiences of parents caring for children with hematological and oncological conditions during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2021;28(4): 720–727. 10.1007/s10880-020-09760-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keshvardoost S, Bahaadinbeigy K, Fatehi F. Role of telehealth in the management of COVID-19: lessons learned from previous SARS, MERS, and Ebola outbreaks. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health. 2020;26(7): 850–852. https://doi:10.1089/tmj.2020.0105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Department of Health & Human Services . Telehealth: Delivering Care Safely During COVID-19. US Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/telehealth/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hooper MW, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24): 2466–2467. https://doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joo JY, Liu MF. A scoping review of telehealth-assisted case management for chronic illnesses [published online April 23, 2021]. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2022;44(6): 598–611. https://doi:10.1177/01939459211008917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ondra S. Why Telehealth and Continuous Remote Patient Monitoring Has Staying Power Beyond COVID-19. Managed Healthcare Executive. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/telehealth-continuous-remote-patient-monitoring-staying-beyond-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thornton L. Telehealth Ensures Continuous, Patient-Centered Care. Kennedy Krieger Institute. https://www.kennedykrieger.org/stories/potential-magazine/summer-2020/telehealth-ensures-continuous-patient-centered-care. Summer 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, Tran L, Vela J, Brooks M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8): e016242. https://doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cipriano PF, Boston-Leaty K, Mcmillan K, Peterson C. The US COVID-19 crises: facts, science and solidarity. International Nursing Review. 2020;67(4): 437–444. https://doi:10.1111/inr.12646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kichloo A Albosta M Dettloff K, et al. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Family Medicine and Community Health. 2020;8(3): e000530. https://doi:10.1136/fmch-2020-000530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nittari G, Khuman R, Baldoni S. Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health. 2020;26(12): 1427–1437. https://doi:10.1089/tmj.2019.0158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Gastmans C. How to achieve the desired outcomes of advance care planning in nursing homes: a theory of change. BMC Geriatrics. 2018;18(1): 47. https://doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0723-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng G. How COVID-19 Is Accelerating Telemedicine Adoption in Asia Pacific. Health Advantage Blog. https://healthadvancesblog.com/2020/05/08/how-covid-19-is-accelerating-telemedicine-adoption-in-asia-pacific/ [Google Scholar]