Abstract

Catheter-directed interventions have slowly been gaining ground in the treatment of pulmonary embolism (PE), especially in patients with increased risk of bleeding. The goal of this study is to summarize the evidence for the efficacy and safety of percutaneous thrombectomy (PT) in patients with contraindications to systemic and local thrombolysis. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis using MEDLINE, Cochrane, Scopus and the Web of Science databases for studies from inception to March 2022. We included patients with intermediate- and high-risk PE with contraindications to thrombolysis; patients who received systematic or local thrombolysis were excluded. Primary endpoint was in-hospital and 30-day mortality, with secondary outcomes based on hemodynamic and radiographic changes. Major bleeding events were assessed as a safety endpoint. Seventeen studies enrolled 455 patients, with a mean age of 58.6 years and encompassing 50.4% females. In-hospital and 30-day mortality rates were 4% (95% CI 3–6%) and 5% (95% CI 3–9%) for all-comers, respectively. We found a post-procedural reduction in systolic and mean pulmonary arterial pressures by 15.4 mmHg (95% CI 7–23.7) and 10.3 mmHg (95% CI 3.1–17.5) respectively. The RV/LV ratio and Miller Index were reduced by 0.42 (95% CI 0.38–46) and 7.8 (95% CI 5.2–10.5). Major bleeding events occurred in 4% (95% CI 3–6%). This is the first meta-analysis to report pooled outcomes on PT in intermediate- and high-risk PE patients without the use of systemic or local thrombolytics. The overall mortality rate is comparable to other contemporary treatments, and is an important modality particularly in those with contraindications for adjunctive thrombolytic therapy. Further studies are needed to understand the interplay of anticoagulation with PT and catheter-directed thrombolysis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11239-022-02750-1.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism, Percutaneous thrombectomy, Hemodynamics, Mortality, Bleeding

Highlights

Catheter-directed interventions have slowly been gaining ground in the treatment of pulmonary embolism.

This study summarizes the evidence for the efficacy and safety of percutaneous thrombectomy in patients with contraindications to systemic and local thrombolysis.

Our meta-analysis to report pooled outcomes on PT The overall mortality and major bleeding of percutaneous thrombectomy in intermediate- and high-risk PE patients without the use of systemic or local thrombolytics is comparable to other contemporary treatments.

Introduction

Despite multiple advancements in therapy in the last two decades, pulmonary embolism (PE) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for the third most common cause of cardiovascular death [1]. The incidence of PE has been on the rise, with an estimated 370,000 PEs per year with resultant annual mortality rate of 33,000 in the United States alone [2, 3]. The COVID-19 pandemic has further compounded this disease state, with a 9-fold increase in the incidence of PE and more than doubled the risk of death in a patient with concomitant COVID-19 compared to PE alone [4].

The fundamental etiology of PE-related mortality is the degree of acute obstructive shock generated upon the right ventricle (RV) as a result of an abrupt decline in forward flow within the pulmonary arteries [5]. Classification of PE (low-risk, intermediate-risk or submassive, and high-risk or massive) is based on the presence or absence of hemodynamic compromise and RV strain [6]. Accordingly, the rate of mortality increases dramatically in the high-risk and intermediate-high-risk patients [6].

Historically, systemic thrombolysis has been the therapy of choice for hemodynamically-significant PEs but at the high cost of major bleeding [7]. The most devastating consequence, intracranial hemorrhage, has been shown to increase with increasing age [8]. Even when screening for absolute contraindications, major hemorrhage can be as high as 20% and intracerebral hemorrhage in 3–5% of patients receiving systemic thrombolysis [9]. Surgical pulmonary embolectomy has traditionally been an alternative when systemic thrombolysis is absolutely contraindicated or unavailable [9]. With recent advents in endovascular techniques and technology, catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) and percutaneous thrombectomy (PT) have emerged as less invasive options for management of the intermediate- and high-risk patients. Despite limited doses of thrombolytics in catheter-based approaches, there remains a risk of major bleeding even with localized infusions [5]. Thus, in the patient with high bleeding risk profile, PT without fibrinolytics remains a desirable choice.

Different mechanisms of PT exist, including rheolytic, mechanical aspiration, and large-bore suction thrombectomy. There is limited data on the overall outcomes of patients undergoing PT without augmentative systemic or local thrombolytics. In this meta-analysis, we assess the overall outcomes of PT in patients with intermediate- to high-risk PE, where systemic- and locally-administered thrombolytics were contraindicated.

Methods

Our systematic review and restrictive meta-analysis was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10].

Search strategy

Our search strategy involved searching Pubmed, Ovid, Scopus, Cochrane and the Web of Science Library up until March 25, 2022. Search strategy terms are reported in Supplemental Material. To complement our search, all references from selected studies were retrieved and manually reviewed according to the snowball effect. We also searched for unpublished abstracts in major congresses. Articles not in English were excluded.

Eligibility criteria and outcomes

Eligible studies included randomized clinical trials as well as non-randomized (prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case control, and case series) studies with the following characteristics: adult patients (age > 18 years of age), diagnosis of acute PE, severity of PE (intermediate-, intermediate- to high-, and high-risk), contraindications to thrombolysis, PT (aspiration/mechanical/rheolytic). Exclusion criteria included narrative review articles, editorials, case reports, experimental in-vitro or ex-vivo studies, or animal studies. We did not include studies with pregnant patients, or patients who received systemic thrombolytics or CDT. The primary outcome was in-hospital and 30-day mortality. Subgroup analysis was performed for in-hospital and 30-day mortality in the intermediate-high- and high-risk PE patient groups. Additional outcomes included hemodynamic outcomes, radiographic outcomes, and major bleeding. Moreover, we performed two meta-regression analyses looking at the association between catheter size and major bleeding as well as and the effect of systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (sPAP) reduction on in-hospital mortality outcomes.

Study selection

After importing database search results into Endnote, duplicate articles were removed. Two reviewers (IM and TK) independently screened titles and abstracts and then full texts for eligible studies; any conflict was resolved between the two reviewers by consensus. Two reviewers (SA and MW) independently extracted data on a predefined Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. A pilot test was performed before initiation to ensure coherence between the two review authors. Efforts to contact authors for missing data relevant to the analysis were made. Risk of bias was assessed by using the ROBINS-I tool, after the full text revision of studies and prior to data extraction [11].

Statistical analysis

Pooled proportion estimates were generated for each of the main and additional outcomes. Unstandardized mean differences were calculated for hemodynamic parameters before and after intervention. Given heterogeneity across studies, both fixed and random effects models were used. Study to study variation was assessed with the chi-square test of heterogeneity. We used the I2 index to quantify inconsistency across studies, with values > 50% described as moderate. Publication bias was visualized with funnel plots and tested with Egger’s test. All statistical analyses were performed on R Software for Statistical Computing.

Results

Study selection

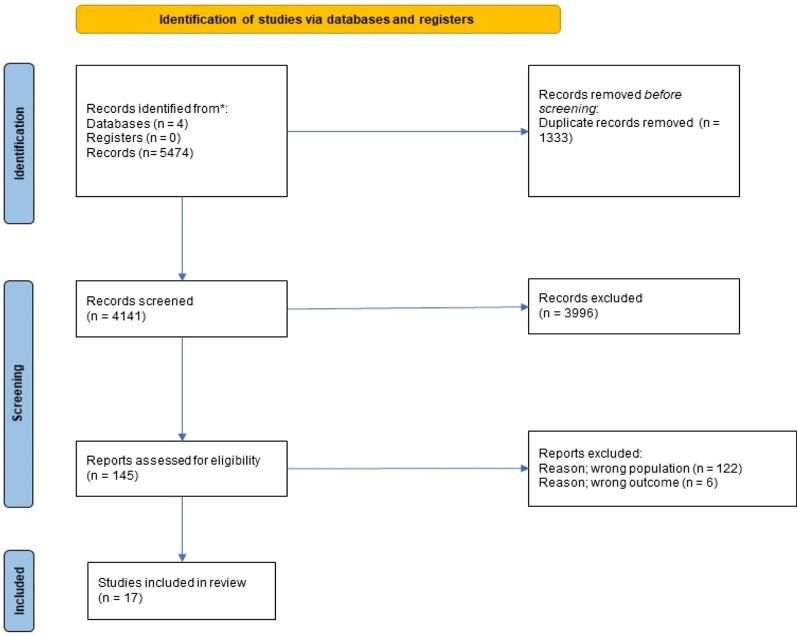

After removing duplicates, 4141 articles were identified for screening. After excluding 3996 articles, 145 possible studies were included for full text review (Fig. 1). Out of these, 6 studies did not report mortality outcomes and 122 studies included patients that received off-protocol CDT, resulting in exclusion. A total of 17 studies were included in our analysis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 Flowdiagram

Study and population characteristics

Eleven of 17 studies were prospective; none of the studies had a control group (Table 1). Most of the studies (13/17) included intermediate- to high-risk patients and rest of the studies (4/17) included only intermediate-risk PE patients. The 8 French (Fr) aspiration catheter systems were used in 8 out of 17 studies, followed by 20 Fr and 5–6 Fr catheter systems.

Table 1.

Type and characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and number of patients included in the meta-analysis

| Author/date | No of patients (original) | No of patients (meta-analysis) | Study | Risk stratification | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Contraindications to thrombolysis | Sheath size | Catheter size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbosa 2007 [14] | 10 | 10 | Prospective | SPE and MPE | Pulmonary artery occlusion > 50%, shock index > 1, sPAP > 25mmHg | Not specified | Not specified | 7 Fr | Rotatable Pigtail William Cook Europe Denmarck or Clot Buster Amplatz thrombectomy device |

| Tu 2019 [12] | 104 | 104 | Prospective | Intermediate risk |

(1) Age ≥ 18 and ≤ 75 years (2) Clinical signs, symptoms, and presentation consistent with acute PE 3) PE symptom duration ≤ 14 days (4) CT evidence of proximal PE (5) RV/LV ratio of ≥ 0.9 (6) SBP > 90mmHg (7) HR < 130 BPM |

(1) Thrombolytic use within 30 days of baseline CT (2) sPAP > 70mmHg (3)Vasopressor use (4) FiO2 > 40% (5) Hematocrit < 28% |

NA | 20–22 Fr | Flowretriever aspiration system (aspiration catheter 20Fr) |

| Bonvini 2013 [15] | 10 | 4 | Prospective | High risk | CTPE AND/OR TTE with RV strain AND Shock Index > 1 |

Non high risk PE Life expectancy < 3months |

NA | 6 Fr | AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy (6Fr) |

| Dumantepe 2015 [16] | 36 | 36 | Prospective | MPE and SPE |

(1) Dyspnea, hypoxia or hemodynamic instability; (2) Evidence of PE by multidetector contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) (3) Right ventricular dysfunction by echocardiography or RV/LV > 0.9 by CT |

NA | NA | 8 Fr |

Aspirex aspiration thrombectomy (8Fr) (catheter, straub medical) |

| Sista 2020 [13] | 119 | 119 | Prospective | SPE | Age > 18, CTA with diagnsis of PE, RV/LV > 0.9 AND SBP > 90mmHg |

(1) tPA use within 14 days prior to baseline CTA (2) SBP < 90 mmHg (3) SPAP > 70 mmHg by HC (4) FiO2 > 40% or > 6 LPM to keep oxygen saturation > 90% (5) Ht < 28% (6) Life Expectancy < 3months |

NA | 8 Fr (15% jugular) | Indigo aspiration catheter (8Fr) |

| Markovitz 2020 [17] | 13 | 13 | Retrospective | SPE and MPE | NA | Absolute and relative contraindications to thrombolysis per AHA guidelines 2011 |

Bleeding Disorder Recent intracranial/spinal surgery Head trauma/recent stroke ICH Intracranial hemorrhage |

22–24 Fr | PMT (percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy) with inari flow triever(20Fr) |

| Müller-Hülsbeck 2001 [18] | 9 | 4 | Prospective | SPE | CT diagostic of PE and duration of symptoms < 14 days | NA | 5/9 received systemic tPA and ruled out from the meta-analysis | 10 Fr | Amplatz thrombectomy device (8 Fr) |

| Voigtländer 1999 [19] | 5 | 5 | Prospective | MPE | PE on CTA AND RV dysfunction on ECHO AND elevated catheter measured PAP | NA | TBI, recent OR, critical iatrogenic bleeding, recent CNS OR, GI bleeding | 8 Fr | AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy (5Fr) |

| Wible 2019 [20] | 46 | 46 | Retrospective | SPE and MPE | NA | NA | 22 Fr | Aspiration mechanical thrombectomy with inari flow triever(20Fr) | |

| Margheri 2008 [21] | 25 | 17 | Retrospective | MPE and SPE | MPE and SPE per ESC 2000 guidelines | NA |

Contraindication to thrombolysis or failed thrombolysis (last group of patients excluded from meta-analysis) |

8 Fr | AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy (5Fr) |

| Al-Hakim 2017 [22] | 6 | 6 | Retrospective | SPE | PE diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) angiography, normotensive, evidence of right heart strain (RV/LV ratio > 1, troponin > 0.04 ng/mL, or prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide > 500 pg/mL), contraindication to thrombolysis, and use of continuous aspiration mechanical thrombectomy | NA | Intraspinal surgery, invasive procedure < 10 days prior, recent trauma, age > 80 years, and high risk of bleeding owing to extensive metastatic disease | 12 Fr | Aspiration mechanical thrombectomy with CAT8 Penumbra (8Fr) |

| Latacz 2018 [23] | 7 | 7 | Prospective | Intermediate and high risk | NA | NA | Absolute contraindications for fibrinolysis comprised head trauma, brain surgery and other major surgical procedures. Relative contraindications regarded patients with traumatic and surgical injuries associated with a high risk of uncontrollable bleeding | 6 or 7 Fr | Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy with AngioJet (5Fr) |

| Yasin 2020 [24] | 8 | 8 | Retrospective | SPE and MPE | NA | NA | NA | 22 Fr | Flowretriever aspiration system (aspiration catheter 20Fr) |

| Bayiz 2015 [25] | 16 | 16 | Retrospective | MPE | MPE classified by local center criteria and invasive angiography | NA | NA | 8 Fr | Aspirex1 aspiration thrombectomy catheter (8Fr) |

| Pelliccia 2020 [26] | 33 | 33 | Prospective | MPE |

(1) Diagnosis of massive PE on the basis of clinical assessment, echocardiographic findings, and biomarkers according to the guidelines of the American Heart Association (2) Evidence of extensive filling defects in either a main or proximal segmental pulmonary artery, as assessed by computed tomography at the spoke hospital and then confirmed by pulmonary angiography at the hub hospital; and (3) Contraindications to use of thrombolytic therapy (both systemic and locally administered) |

(1) Evidence of subsegmental PE; (2) evidence of irreversible neurologic abnormalities; and (3) life expectancy of < 6 months | Head trauma, brain surgery, and other major surgical procedures | 8 Fr | AngioJet catheter (8Fr) |

| Pieraccinni 2017 [27] | 18 | 18 | Prospective | MPE and SPE | MPE and SPE per ESC/AHA guidelines AND contraindications to thrombolysis and no contraindications to pulmonary artery catheterization | Low risk and intermediate-low risk PE without contraindications to thrombolytics | Ischaemic stroke, central nervous system damage/neoplasms, recent major trauma/surgery/head injury, gastrointestinal bleeding | 8 Fr | Aspiration mechanical thrombectomy with CAT8 Penumbra (8Fr) |

| Liu 2010 [28] | 14 | 9 | Retrospective | MPE | MPE initially diagnosed by contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CT) and confirmed by angiography (obstruction of two or more lobar arteries or equivalent, mean pulmonary artery pressure > 25 mmHg and shock index > 1 | NA | NA | 8 Fr (Right internal jugular vein) | Rotarex thrombectomy system (8Fr) |

A total of 455 patients comprised our study cohort, out of which 50.4% were female. Patients had a mean age of 58.6 years [interquartile range (IRQ) 54.5–62.7]. Of note, the studies of Tu et al. and Sista et al. contributed 223 patients in our meta-analysis [12, 13].

Outcomes

Pooled proportional effect estimate for in-hospital and 30-day mortality was calculated at 4% [95% confidence interval (CI) 1–11%] and 5% (95% CI 2–13%), respectively (Figs. 2, 3) for all intermediate- and high-risk patients. Heterogeneity was low for both analyses (I2 = 17 and 37, respectively). Subgroup analyses were performed for studies including only intermediate-high-risk and high-risk patients, showing increased in-hospital mortality at 7% (95% CI 2–20%) and 30-day mortality at 7% (95% CI 2–21%) (Figs. S1, S2).

Fig. 2.

Pooled proportional incidence of in-hospital mortality in intermediate, intermediate-high and high risk PE patients

Fig. 3.

Pooled proportional incidence of 30-day mortality in intermediate, intermediate-high and high risk PE patients

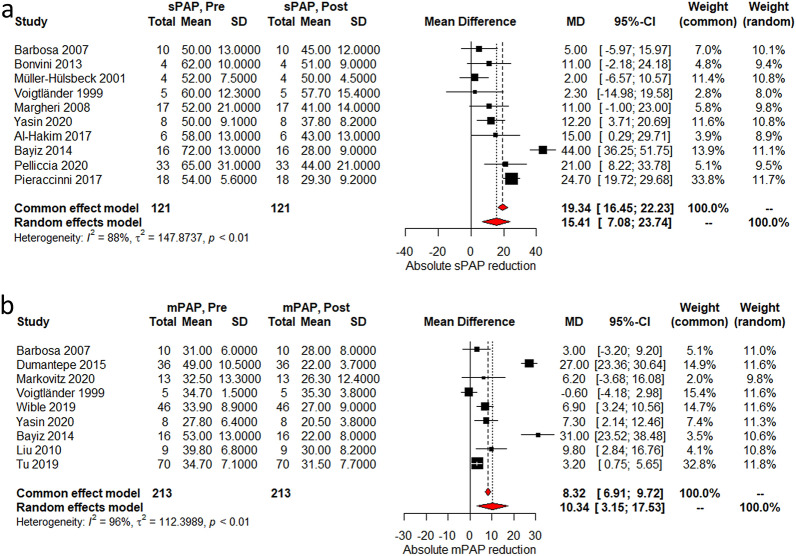

Most of the studies reported data on the effect of the intervention to hemodynamics as well as right ventricular/left ventricular (RV/LV) ratio and Miller Index. There was a mean heart rate (HR) reduction of 20 beats per minute (95% CI 8.8–31.5) after PT was performed (Fig. 4a). On the other hand, O2 saturation (SaO2) on pulse oximetry and systolic blood pressure (SBP) increased by 9.2% (95% CI 3.7–14.6%) and 15.7 mmHg (95% CI 3.4–28 mmHg), respectively, after the intervention (Fig. 4b, c). Systolic and mean pulmonary arterial pressures (sPAP and mPAP) decreased by 15.4 mmHg (95% CI 7–23.7 mmHg) and 10.3 mmHg (95% CI 3.1–17.5 mmHg) (Fig. 5a, b). Degree of systolic pulmonary artery pressure reduction was not associated with in-hospital mortality (p = 0.7, Fig. S3). Lastly, RV/LV ratio and Miller Index decreased by 0.42 (95% CI 0.38–46) and 7.8 (95% CI 5.2–10.5) (Fig. 6a, b). Heterogeneity was high with I2 > 90% for most of the hemodynamic outcomes; we performed sensitivity analyses that did not significantly improved heterogeneity (Supplemental material figs. S1–S5).

Fig. 4.

a Absolute mean difference reduction in heart rate reduction pre and post procedure; b Absolute mean difference reduction in O2 saturation on pulse oximetry pre and post procedure; c Absolute mean difference reduction in systolic blood pressure pre and post procedure; MD mean difference

Fig. 5.

a Absolute mean difference in sPAP pre and post procedure; b Absolute mean difference in mPAP pre and post procedure; MD mean difference

Fig. 6.

a Absolute mean difference reduction in RV/LV Ratio pre and post procedure; b Absolute mean difference reduction in Miller index pre and post procedure; MD mean difference

The average procedure time and total length of stay based on pooled proportional effect estimates was 67 minutes (95% CI 42–92) and 7.3 days (95% CI 5.5–8.8) (Figs. S4, S5). Major bleeding was noted at 3% (95% CI 1%–8%) (Fig. 7). No association was noted between catheter size and major bleeding (R −0.03, p = 0.59, Fig. S6) using meta-regression analysis.

Fig. 7.

Pooled proportional incidence of major bleeding post-procedurally in intermediate, intermediate-high and high risk PE patients

Risk of bias assessment

The studies included were mostly single arm, unblinded prospective trials. Risk of bias assessment is presented in Fig. S7. Funnel plots and Egger’s tests were negative for publication bias in terms of 30-day mortality and catheter-related major bleeding outcomes (Figs. S8–10). Egger’s test was positive for in-hospital mortality outcome (p < 0.007). We identified seven possible missing studies, the effect of which would not have significantly changed the pooled proportional outcome.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to investigate PT outcomes in patients with intermediate- to high-risk PE with contraindications to systemic and local thrombolysis. We included 17 studies with 455 patients in the final analysis, with a finding of overall in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates in the 4–5% range, but higher in the intermediate-high- and high-risk patients. Overall, hemodynamics improved along with decreased radiographic thrombus burden and RV strain.

Past studies have generated favorable data regarding the safety and efficacy of systemic thrombolytics in patients with intermediate- to high-risk PE. In a meta-analysis performed by Marti et al., pooling more than 2057 acute PE patients (including low-, intermediate-, and high-risk) to compare systemic thrombolysis versus heparin alone, thrombolytic therapy reduced mortality only in the high-risk group [odds ratio (OR) 0.59, 95% CI 0.36–0.96], but at the expense of increased incidence of major bleeding (OR 3.18, 95% CI 1.25–8.11) [29]. Similarly, the pulmonary embolism thrombolysis (PEITHO) trial showed no difference in mortality between the thrombolysis and heparin anticoagulation alone (OR 0.63, p = 0.02) in patients with intermediate-risk PE, but increased major bleeding events in the intervention arm (OR 5.55, p < 0.001) [30]. As such, catheter-based interventions are promising alternatives in the treatment of PE patients in the current era. Although the doses of thrombolytics utilized in CDT are much smaller than systemic administration (25 +/− 12.5mg of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator), there still remains a small inherent risk of bleeding [5, 31]. CDT may be too high of risk for patients with absolute and/or relative contraindications to thrombolytics. Thus, we sought to study the outcomes of PT without adjunctive systemic or local thrombolytics in patients with intermediate- and high-risk PE with contraindications to thrombolysis.

Our mortality rates are comparable to other PE studies. The overall mortality in low-intermediate- to high-risk patients in a meta-analysis by Marti et al was 2% for the thrombolysis group and 4% for the heparin group [29]. Based on an older evaluation of the national inpatient sample database by Patel et al., which compared 1169 patients undergoing systemic thrombolysis versus 352 treated with catheter-directed therapies, including locally administered thrombolysis, the in-hospital mortality (20.0% vs. 10.2%, P < 0.001) were lower in the catheter-directed therapy group [32]. In a systematic review evaluating catheter-directed intervention, including locally administered thrombolysis, in comparison to open embolectomy, in-hospital mortality was estimated to be 6% in the intermediate- to high-risk patients [9]. Moreover, Tafur et al. showed mortality rates of 4 and 9% in the ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis (USAT) studies and non-USAT studies respectively [33]. A review that assessed all the contemporary studies investigating the role of ultrasound-guided thrombolysis found a mortality rate of 3.2% [34].

Various clinical endpoints were investigated using two different effects models. Regardless of the effects model used, there were statistically significant improvements in HR, SpO2, SBP, sPAP, mPAP, Miller index, and RV/LV ratio. Fasullo et al. compared hemodynamic effects of systemic thrombolysis against anticoagulation alone, with a finding that systemic thrombolysis was superior in RV/LV ratio improvement (1.4 ± 0.05➝1.12 ± 0.04) against anticoagulation alone in intermediate-risk patients (1.42 ± 0.04➝1.25 ± 0.04) [35]. Macovei et al. reported improvement in sPAP between local (decrease from 51 to 15 mmHg and systemic thrombolysis groups in high-risk patients (decrease from 70 to 37 mmHg) [36]. Although our findings suggest a less dramatic decrease in sPAP with non-fibrinolytic based therapies, there still remained a statistically significant drop in sPAP. In our exploratory analysis, the degree of sPAP drop was not associated with mortality outcomes.

The major bleeding incidence in our study was noted at 3%, which is lower than other analyses with thrombolytics. Even though early trials by Konstantinides et al. showed similar major bleeding events between thrombolysis and heparin arms for intermediate-risk PE patients, the PEITHO trial showed significantly elevated major bleeding events in the thrombolysis arm compared to heparin (6.3%, p < 0.001) in the same patient population [30, 37]. In a meta-analysis comparing thrombolysis versus heparin in intermediate- and high-risk patients, major bleeding events were present in 9.9% of patients on thrombolytics and 3.6% of control patients (p < 0.001) [29]. In the study of Patel et al. the incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was higher in the thrombolysis group versus the group that underwent catheter-directed therapies (21.0% vs. 10.5%, P < 0.001) [32]. On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis of CDT in intermediate- and high-risk PE patients noted major bleeding events to be 1.8% (CI 0.3–4%) [31]. One possible explanation for the difference in reported rates of major bleeding could be the heterogeneity in major bleeding definition from study to study.

Limitations

Our meta-analysis has several limitations and results should be interpreted with caution. The studies included were single arm, and pre- and post-intervention data was used to assess the efficacy and safety of the intervention. As shown by past data, anticoagulation alone can produce similar changes in hemodynamic parameters, albeit likely at a slower rate [35]. Without a comparison group, it is uncertain if any benefit unique to PT was achieved in the included studies. Additionally, significant heterogeneity was present in the hemodynamics evaluation, as demonstrated by I2 values > 50% for most of the hemodynamic parameters that were assessed. Much of this heterogeneity likely results from distinctions in inclusion and exclusion criteria in the studies analyzed. Additionally, studies from 2007 to 2020 were included in the analysis, which may be a source of heterogeneity, given the rapidly changing thrombectomy technologies within this period of time. Finally, we were unable to assess long term outcomes, including the development of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension following intervention as this data was not reported.

Future directions

The emerging use of CDT and PT with the encouraging outcomes reported in multiple cohorts of patients and meta-analyses has prompted further investigation of these treatment modalities. Currently, the higher-risk pulmonary embolism thrombolysis (HI-PEITHO) study investigators randomize patients to compare the efficacy of CDT versus anticoagulation alone [38]. The PEERLESS trial will shed light on CDT versus PT with a large bore device in clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

In patients with intermediate- to high-risk PE with contraindications to systemic or local thrombolytics, PT is a safe and feasible therapy to help reduce overall mortality and improve hemodynamics rapidly. Ongoing evaluation of the role of PT against thrombolytic-based therapies and anticoagulation will be imperative in the rapidly evolving field of catheter-directed therapies.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (DOCX 480.7 kb)

Funding

There was no funding received for this research project.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Shishehbor is a consultant for Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Terumo, Philips, and Boston Scientific. Dr. Li is on the advisory board for Boston Scientific, Inari Medical, and Medtronic; she receives research funding from Abbott Vascular and Inari Medical. The rest of the authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Turetz M, Sideris A, Friedman O, Triphathi N, Horowitz J, Epidemiology Pathophysiology, and natural history of pulmonary embolism. Semin intervent Radiol. 2018;35:92–98. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1642036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virani SS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SB, et al. Analysis of national trends in admissions for pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2016;150:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miró Ò, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: incidence, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3127–3142. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo WT, et al. Catheter-directed therapy for the treatment of massive pulmonary embolism: systematic review and meta-analysis of modern techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1431–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konstantinides SV, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European respiratory society (ERS) Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg I, Jaff MR. Accelerated Thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism: will clinical benefit be ultimately realized? Circulation. 2014;129:420–421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vedantham S, Piazza G, Sista AK, Goldenberg NA. Guidance for the use of thrombolytic therapy for the treatment of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:68–80. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1318-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loyalka P, et al. Surgical pulmonary embolectomy and catheter-based therapies for acute pulmonary embolism: a contemporary systematic review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:2155–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterne JA, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu T, et al. A prospective, single-arm, multicenter trial of catheter-directed mechanical thrombectomy for intermediate-risk acute pulmonary embolism. JACC. 2019;12:859–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sista AK, et al. Indigo aspiration system for treatment of pulmonary embolism. JACC. 2021;14:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbosa MAO, et al. Treatment of massive pulmonary embolism by percutaneous fragmentation of the thrombus. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia. 2007;88:279–284. doi: 10.1590/S0066-782X2007000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonvini RF, et al. AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy in patients presenting with high-risk pulmonary embolism and cardiogenic shock: a feasibility pilot study. EuroIntervention. 2013;8:1419–1427. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I12A215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumantepe M, Teymen B, Akturk U, Seren M. Efficacy of rotational thrombectomy on the mortality of patients with massive and submassive pulmonary embolism. J Card Surg. 2015;30:324–332. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markovitz M, Lambert N, Dawson L, Hoots G. Safety of the Inari FlowTriever device for mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute submassive and massive pulmonary embolism and contraindication to thrombolysis. AJIR. 2020;4:18. doi: 10.25259/AJIR_26_2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müller-Hülsbeck S, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy of major and massive pulmonary embolism with use of the Amplatz thrombectomy device. Invest Radiol. 2001;36:317–322. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voigtlander T, et al. Clinical application of a new rheolytic thrombectomy catheter system for massive pulmonary embolism. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 1999;47:91–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-726X(199905)47:1<91::AID-CCD20>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wible BC, et al. Safety and efficacy of acute pulmonary embolism treated via large-bore aspiration mechanical thrombectomy using the inari FlowTriever device. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:1370–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2019.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margheri M, et al. Early and long-term clinical results of AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Hakim R, Bhatt A, Benenati JF. Continuous aspiration mechanical thrombectomy for the management of submassive pulmonary embolism: a single-center experience. J Vasc interventional Radiol. 2017;28:1348–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latacz P, et al. Treatment of high- and intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism using the AngioJet percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy system in patients with contraindications for thrombolytic treatment - a pilot study. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2018;13:233–242. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2018.75848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yasin J, et al. Technical efficiency, short-term clinical results and safety of a large-bore aspiration catheter in acute pulmonary embolism - A retrospective case study. Lung India. 2020;37:485–490. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_115_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayiz H, Dumantepe M, Teymen B, Uyar I. Percutaneous aspiration thrombectomy in treatment of massive pulmonary embolism. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelliccia F, et al. Safety and outcome of rheolytic thrombectomy for the treatment of acute massive pulmonary embolism. J Invasive Cardiol. 2020;32:412–416. doi: 10.25270/jic/20.00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pieraccini M, et al. Acute massive and submassive pulmonary embolism: preliminary validation of aspiration mechanical thrombectomy in patients with contraindications to thrombolysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:1840–1848. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-2011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu S, et al. Massive pulmonary embolism: treatment with the Rotarex thrombectomy system. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34:106–113. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9878-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marti C, et al. Systemic thrombolytic therapy for acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:605–614. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer G, et al. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1402–1411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avgerinos ED, et al. A meta-analysis of outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis for high- and intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. J Vascular Surgery. 2018;6:530–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel N, et al. Utilization of catheter-directed thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism and outcome difference between systemic thrombolysis and catheter-directed thrombolysis: Catheter-directed thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2015;86:1219–1227. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tafur AJ, et al. Catheter-directed treatment of pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of modern literature. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2017;23:821–829. doi: 10.1177/1076029616661414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chopard R, Ecarnot F, Meneveau N. Catheter-directed therapy for acute pulmonary embolism: navigating gaps in the evidence. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2019;21:I23–I30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suz224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fasullo S, et al. Six-month echocardiographic study in patients with submassive pulmonary embolism and right ventricle dysfunction: comparison of thrombolysis with heparin. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:33–39. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181f1fc3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macovei L, et al. Local thrombolysis in high-risk pulmonary embolism—13 years single-center experience. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26:107602962092976. doi: 10.1177/1076029620929764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konstantinides S, Annette G, Gerhard H, Fritz H, Wolfgang K. Heparin plus alteplase compared with heparin alone in patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;8:1143–1150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klok FA, et al. Ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed thrombolysis vs anticoagulation alone for acute intermediate-high-risk pulmonary embolism: Rationale and design of the HI-PEITHO study. Am Heart J. 2022;251:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2022.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 (DOCX 480.7 kb)