Abstract

We introduced the AliveCor KardiaMobile electrocardiogram (ECG), a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, iPad-enabled medical device, into the preclerkship curriculum to demonstrate the clinical relevance of cardiac electrophysiology with active learning. An evaluation showed that medical students considered the KardiaMobile ECG active learning activity to be a valuable educational tool for teaching cardiac physiology.

Keywords: active learning, medical school education, mobile ECG

INTRODUCTION

Illustrating clinical relevance in the preclerkship medical school curriculum promotes successful application of scientific knowledge in the clinical years (1). Medical students’ perceived clinical relevance of physiology instruction maximizes engagement in the classroom (2) and enhances the retention of basic science knowledge throughout undergraduate medical education and beyond (3). Although the electrocardiogram (ECG) is a widely used diagnostic tool in medicine, effective teaching of clinical ECG fundamentals is difficult in the classroom setting because of the complexity of the material, normal ECG variations in the population, and knowledge barriers preventing translation of static concepts from the classroom into clinical practice (4, 5).

A number of innovative strategies for ECG education have been implemented, including educational software (5), drawing (4), and web-based programs (6). In the first year of the preclerkship curriculum (MS1) at the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine (UCI), physiology faculty and students continuously improve the quality of medical physiology education through the introduction of innovating teaching modalities including E-learning modules and peer-led review sessions (7, 8). Physiology faculty hypothesized that incorporating live ECG devices as an active learning session would further students’ understanding of cardiovascular physiology and the interpretation of the ECG as a clinical tool. The KardiaMobile device was chosen given its affordability, accessibility, and ease of use compared with a standard 12-lead ECG.

The AliveCor KardiaMobile medical-grade ECG was evaluated as a promising tool to bring hands-on ECG experiences to first-year medical students. The KardiaMobile product consists of two electrodes, a piezo transducer, a printed circuit board assembly, and a battery housed in a plastic chassis. The device communicates with compatible mobile devices on the Apple iOS and Android platforms through the Kardia app using ultrasonic audio. The KardiaMobile was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014 as a medical device intended to record, store, and transfer single-channel ECG rhythms. Clinically, the Kardia app displays ECG rhythms and detects the presence of both normal sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation. There have been over 40 clinical studies performed with the KardiaMobile device, and KardiaMobile is integrated with an FDA-cleared automatic algorithm for the detection of atrial fibrillation with 98% sensitivity and 97% specificity (9). Because of its affordability, KardiaMobile is widely used for telemedicine applications to allow patients to monitor and readily communicate ECG readings outside the clinical setting. Here, we describe the use of the KardiaMobile iOS- and Android-enabled ECG modality to improve the hands-on learning experience and interpretation of cardiovascular physiology.

METHODS

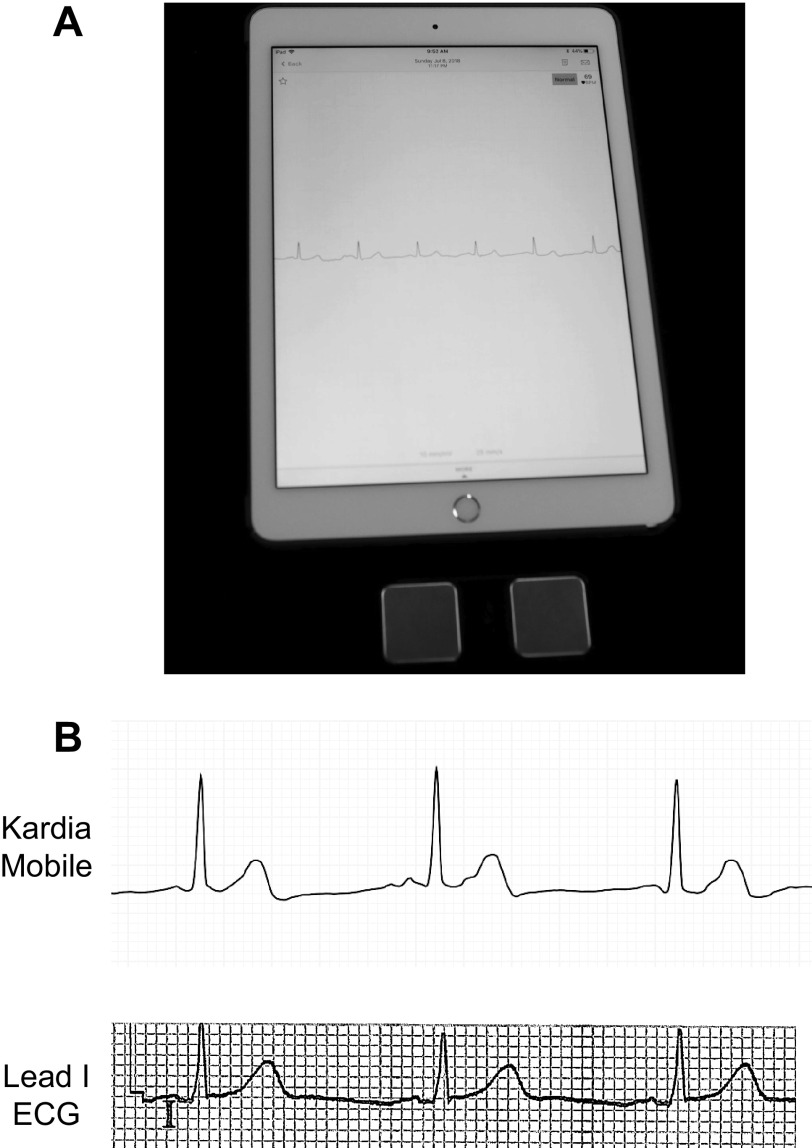

Before the in-class active learning session, the Kardia application was downloaded from the Apple App Store onto the Apple iPads that were distributed for the activity (Fig. 1A). New accounts were established in the Kardia application, and trial runs and sample rhythm strips were performed before the classroom activity with Division of Educational Technology faculty and teaching faculty from the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at the School of Medicine (UCI).

Figure. 1.

KardiaMobile equipment and output. A: Kardia iPad application running with the KardiaMobile electrocardiogram (ECG) medical device. B, top: example Kardia application output of a sinus rhythm when left and right fingers are placed on both KardiaMobile electrodes. Bottom: lead I ECG rhythm strip acquired from a standard 12-lead Burdick 8500 ECG from the same patient. Paper speed = 25 mm/s; gain = 10 mm/mV.

ECG recording involved holding the single-lead KardiaMobile device close to the iPad with one hand on each electrode, simulating a lead 1 ECG, tapping the “Record Now” button, and following the on-screen instructions. Typically, best results were demonstrated when one student held the KardiaMobile device with one hand on each electrode, simulating a lead 1 ECG, while another student held the iPad close to the KardiaMobile device until a “Strong Signal” was established. “Strong Signal” refers to a well-established connection between the KardiaMobile device and its respective iPad to ensure a stable recording. Excessive artifact or noise was improved by cleaning fingers and electrodes with an alcohol-based sanitizer, removing jewelry, clicking the “Enhanced Filter” button, and relaxing during recording. An example Kardia application rhythm strip, compared to the output of a standard 12-lead ECG, is shown in Fig. 1B. This study was qualified as exempt research by the UCI Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects.

General Procedure

One day before the ECG active learning session, students were given a digital handout detailing the instructions for the active learning activity. The in-class active learning session took place in the main MS1 lecture hall over a 50-min period. Before the beginning of the activity, students were informed that they would be reading and sharing their ECG readings with their fellow group members. Student participation was optional, and no student was required to record their own ECG if they were uncomfortable sharing their ECG readings. The lecturing faculty began with a 5-min introductory lecture, summarizing the learning objectives for the session and demonstrating use of the KardiaMobile. MS1 students were then asked to self-organize into groups of 8–10 students throughout the lecture hall, with sufficient distance between groups to prevent interference between adjacent KardiaMobile devices. During the activity, students were encouraged to work through the different exercises and answer the associated questions. Students were also asked to justify and provide rationale for their answers to the questions beyond a “yes or no” answer. Physiology faculty were available to review and evaluate the rhythm strips and recommend evaluation by a physician if unexpected ECG abnormalities were detected during the active learning activity. Throughout the session, physiology faculty circulated between the student groups, answered questions, and provided technical support.

Students were asked to complete four assignments for the KardiaMobile ECG active learning session: Reading the ECG, Comparing ECG Readings, Autonomic Regulation, and Simulating a 12-lead ECG.

Active learning assignment 1: Reading the ECG.

Learning objective.

Students will become familiar with analyzing a lead 1 ECG recording by examining their classmates for common cardiac abnormalities. The approach to ECG interpretation was adapted from Strong electrocardiography (10). Of the cardiac abnormalities prioritized, heart block is seen in 6% of adults over 60 yr and in 1–1.5% of those under 60 yr old (11). Additionally, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are common, with an estimated prevalence of >40% in the general population (12). Heart block was included in this exercise not only given its prevalence in patients but also because it is also listed in the content outline for the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) (13).

Procedures.

Each participating student will hold the KardiaMobile with one hand on each electrode according to the procedures described above. For every student who performs an ECG reading, the group will answer the following questions:

- Is there a detectable heart block?

- What is the definition of heart block?

- Test for 1st degree heart block: Is the PR interval < 200 ms?

- Test for 2nd and 3rd degree heart block: Is there a 1:1 relationship of P waves to QRS complexes?

- Are the ventricles contracting properly?

- Which ECG waveform represents ventricular contraction?

- Test for aberrant ventricular conduction: Is the QRS complex duration < 120 ms?

Active learning assignment 2: Comparing ECG readings.

Learning objective.

Exemplar normal ECGs in textbooks and lecture slides typically do not encompass the diversity of normal waveforms in the general population. Assignment 2 is designed to show the diversity of normal ECG waveforms in the population represented by the students engaging in the activity. Students will become familiar with common, nonpathological populational cardiac variations in ECG waveforms due to differences in athletic training, body type, and sex. For the following activities, students are asked to self-identify, share their ECG readings, and discuss the broad range of normal ECG waveforms.

Procedures.

Athletic training: The UCI medical class contains a diverse student body, including students with considerable collegiate athletic accomplishments. Students will identify group members with extensive athletic training and minimal athletic training. After ECG recording, the group will answer the following questions:

Are there detectable differences in ECG waveform amplitude between students?

Are there detectable differences in resting heart rate between classmates?

Body types: Body type can affect the positioning of the heart in the thoracic cavity and the amplitude of different waveforms determined by a lead 1 ECG. Students will identify group members with different body types (stature, build, etc.). After ECG recording, the group will answer the following questions:

Are there detectable differences in ECG waveform amplitude between students?

Do differences in body type affect the positioning of the heart?

Sex differences: Although there is significant variation, healthy adult women tend to have a faster heart rate, smaller left ventricular mass, and a QT interval that is, on average, ∼20 ms longer than men (14). After ECG recording, the group will answer the following questions:

Are there detectable differences in ECG waveform amplitude between students?

Are there detectable differences in QT intervals between students?

Active learning assignment 3: Autonomic regulation.

Learning objective.

Students will become familiar with how vagal maneuvers can induce sinus bradycardia and how exercise can induce sinus tachycardia with the lead 1 ECG. Vagal maneuvers are commonly used to increase vagal parasympathetic tone to diagnose and treat various arrhythmias (15). Additionally, exercise results in a number of ECG changes including QRS complex shortening, altered T-wave morphologies, ST segment upsloping, and QT interval shortening (16).

Procedures.

Vagal maneuvers: The Valsalva maneuver induces bradycardia that can be detected on the ECG (17). Students will take an ECG recording before and after performing the Valsalva maneuver or another vagal maneuver. After the ECG recordings, the group will answer the following questions:

Are there detectable differences in heart rate after the vagal maneuver?

If so, which portion of the cardiac cycle was most affected?

Sympathetic stimulation: Students will perform an ECG recording before and after a bout of exercise. Exercise may include running in place, climbing stairs, or performing jumping jacks for 2 min. The second ECG reading will be performed immediately after. After the ECG recordings, the group will answer the following questions:

Are there detectable differences in heart rate after exercise?

Are any of the ECG waveform changes listed above observed?

Active learning assignment 4: Simulating a 12-lead ECG.

Learning objective.

Students will examine how the car diac waveforms change when viewed from different angles by using the KardiaMobile to simulate a 12-lead ECG to generate a three-dimensional (3-D) electrical view of the heart. Examination of the transverse plane using the precordial leads is fundamental to the understanding of cardiac electrophysiology and the diagnosis of cardiac abnormalities, including hypertrophy and infarction (10).

Procedures.

Students will hold the KardiaMobile in their right hand, with fingers on one electrode, to simulate the negative electrode. The student holding the KardiaMobile will then place the second electrode under the shirt at the V1 site at the 4th intercostal space to the right of the sternum. Another group member should hold the iPad close to the KardiaMobile to record the simulated V1 rhythm. The student should then repeat the procedure simulating a V6 recording, with the second electrode placed level with the 5th intercostal space at the left midaxillary line. The procedure can then be repeated for all precordial and limb leads to generate recordings that resemble waveforms shown on the normal 12-lead ECG (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Simulated 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) with KardiaMobile output and comparison. Example KardiaMobile application output of a sinus rhythm when simulating a 12-lead ECG (left) compared with the rhythm strip acquired from a standard 12-lead Burdick 8500 ECG from the same patient (right). Example V1 rhythm, when the right thumb is placed on one KardiaMobile electrode and the second electrode is placed at the V1 site (4th intercostal space to the right of the sternum). Example V2 rhythm, when the right thumb is placed on one KardiaMobile electrode and the second electrode is placed at the V2 site (4th intercostal space to the left of the sternum). Example V6 rhythm, when the right thumb is placed on one KardiaMobile electrode and the second electrode is placed at the V6 site (5th intercostal space in the midaxillary line). Paper speed = 25 mm/s; gain = 10 mm/mV.

For the Simulating a 12-lead ECG activity, it was clarified to the students that this procedure does not truly produce accurate recordings from precordial leads because of the lack of a Wilson central terminal providing a reference. Another limitation was the need to acquire each lead sequentially, compared with a standard 12-lead ECG recording, where several different leads are analyzed simultaneously.

Evaluation

To evaluate students’ perceptions of the utilization of mobile ECG devices in their first-year medical school curriculum, students were asked to complete an online survey toward the completion of their MS1 academic year. Survey questions and results are detailed in Fig. 3. Of the students who responded to the survey for this activity, 22% of them (n = 41) agreed or strongly agreed that that they had previous experience with mobile medical devices before entering medical school. Sixty-seven percent of students (n = 39) agreed or strongly agreed that the AliveCor KardiaMobile device was a valuable addition to ECG instruction. Fifty-one percent (n = 39) of students agreed or strongly agreed that the activity furthered their understanding of ECGs. Ninety-two percent of students (n = 39) surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that using mobile medical devices will help further their medical education. Ninety-two percent of students (n = 38) agreed or strongly agreed that knowing about mobile medical devices will be important in their future practice as physicians.

Fig. 3.

MS1 students’ evaluation of the electrocardiogram (ECG) active learning sessions. Data represent 41 questionnaire responses from the MS1 class. Survey questions: 1) I had experience with mobile medical devices before starting medical school. 2) The AliveCor KardiaMobile device was a valuable addition to the “Reading ECG” session in Physiology. 3) I felt that using the AliveCor KardiaMobile device helped further my understanding of ECGs. 4) I feel that using mobile medical devices will help further my medical education. 5) Knowing about mobile medical devices is important in my future practice as a physician.

DISCUSSION

The KardiaMobile ECG device was easily integrated with our preclerkship curriculum and readily deployed in the lecture hall, improving the clinical relevance of cardiovascular physiology instruction. The design of the active learning session for this study was anchored by the hands-on experience with the KardiaMobile. This active learning session was designed to align with Kolb’s experiential learning cycle (18), enabling a concrete experience with the KardiaMobile device, reflective observation through the questions integrated into each of the four active learning activities, abstract conceptualization during small-group discussion and faculty feedback, and opportunity for active experimentation throughout the session. Experiential learning has been shown to increase student interest and competency (19) over step-by-step or passive activities.

Although many of the activity questions were structured in a binary, “yes or no” format, students were encouraged to discuss their answers with their peers during the breakout group sessions. This study provides a framework that could be quickly adapted in other physiology education settings. The activity could be improved, including in the formatting of some discussion questions, but this allows for a framework that can be rapidly expanded and implemented.

Barriers to implementation were relatively minor and included the cost of the devices, acquisition of sufficient devices to reduce the number of students per small group, and recruitment of teaching faculty to assist the students during the session. Most students felt that the active learning session helped improve their understanding of cardiovascular physiology. Limitations of the approach involved the use of a single-lead device and relatively large student groups. In future ECG sessions, more KardiaMobile devices will be made available to students in order to decrease overall group size, to increase hands-on opportunities for all students. Additional physiology faculty will also be made available to students to help facilitate and scaffold the learning experience. Additional mobile health care devices can be implemented in similar active learning sessions, including digital fingertip pulse oximeters, smart spirometers, digital stethoscopes, and retinal cameras (20). In summary, implementation of the KardiaMobile device in the ECG active learning session was an effective learning strategy to improve ECG education within UCI’s preclerkship curriculum.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.H.F., A.C.G., J.Y., W.F.W., and M.L.G. conceived and designed research; E.H.F., A.C.G., J.Y., W.F.W., and M.L.G. performed experiments; E.H.F. and M.L.G. analyzed data; E.H.F., A.C.G., J.Y., W.F.W., and M.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; E.H.F. and M.L.G. prepared figures; E.H.F., A.C.G., J.Y., W.F.W., and M.L.G. drafted manuscript; E.H.F., A.C.G., J.Y., W.F.W., and M.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; E.H.F., A.C.G., J.Y., W.F.W., and M.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Michael Cahalan and Dr. Amit Jairaman for assistance in proctoring the active learning session. We especially thank Angel Meza and David Williams for excellent administrative support enabling successful active learning implementation and evaluation. We also thank Francisco Chanes for photography and Ken Tran for technological support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dahle LO, Brynhildsen J, Behrbohm Fallsberg M, Rundquist I, Hammar M. Pros and cons of vertical integration between clinical medicine and basic science within a problem-based undergraduate medical curriculum: examples and experiences from Linkoping, Sweden. Med Teach 24: 280–285, 2002. doi: 10.1080/01421590220134097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandiera G, Boucher A, Neville A, Kuper A, Hodges B. Integration and timing of basic and clinical sciences education. Med Teach 35: 381–387, 2013. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.769674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malau-Aduli BS, Lee AY, Cooling N, Catchpole M, Jose M, Turner R. Retention of knowledge and perceived relevance of basic sciences in an integrated case-based learning (CBL) curriculum. BMC Med Educ 13: 139, 2013. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arsanious MN, Brown G. A novel approach to teaching electrocardiogram interpretation: learning by drawing. Med Educ 52: 559–560, 2018. doi: 10.1111/medu.13535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pontes PA, Chaves RO, Castro RC, de Souza EF, Seruffo MC, Frances CR. Educational software applied in teaching electrocardiogram: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int 2018: 1–14, 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/8203875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson M, Bolinder G, Held C, Johansson BL, Fors U, Östergren J. Evaluation of a web-based ECG-interpretation programme for undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ 8: 25, 2008. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisch EH, Bhatter P, Grimaud LW, Tiourin E, Youm JH, Greenberg ML. A preference for peers over faculty: implementation and evaluation of medical student-led physiology exam review tutorials. Adv Physiol Educ 44: 520–524, 2020. doi: 10.1152/advan.00084.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longmuir KJ. Interactive computer-assisted instruction in acid-base physiology for mobile computer platforms. Adv Physiol Educ 38: 34–41, 2014. doi: 10.1152/advan.00083.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau JK, Lowres N, Neubeck L, Brieger DB, Sy RW, Galloway CD, Albert DE, Freedman SB. iPhone ECG application for community screening to detect silent atrial fibrillation: a novel technology to prevent stroke. Int J Cardiol 165: 193–194, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strong E. YouTube as an educational resource for learning ECGs. J Electrocardiol 47: 758–759, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oldroyd SH, Makaryus AN. First Degree Heart Block. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn MS. Current concepts of premature ventricular contractions. J Lifestyle Med 3: 26–33, 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.USMLE Content Outline. United States Medical Licensing Examination, 2020.

- 14.Rautaharju PM, Zhou SH, Wong S, Calhoun HP, Berenson GS, Prineas R, Davignon A. Sex differences in the evolution of the electrocardiographic QT interval with age. Can J Cardiol 8: 690–695, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niehues LJ, Klovenski V. Vagal Maneuver. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whyte GP, Sharma S. Practical ECG for Exercise Science and Sports Medicine. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elisberg EI. Heart rate response to the valsalva maneuver as a test of circulatory integrity. JAMA 186: 200–205, 1963. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03710030040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolb D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konak A, Clark TK, Nasereddin M. Using Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle to improve student learning in virtual computer laboratories. Comput Educ 72: 11–22, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasich T. Doctors go digital: smartphone attachments are replacing traditional tools of the trade. UCI News, 2016. [Google Scholar]