ABSTRACT

As individuals age, they become increasingly prone to infectious diseases, many of which are vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs). Adult immunization has become a public health priority in the modern era, yet VPDs vaccination rates for adults are low worldwide. In Central America and Caribbean, national recommendations and vaccination practices in adults differ across countries, and adult vaccination coverage data are limited. An advisory board comprised infectious disease experts, pulmonologists, geriatricians, occupational health, and public health professionals for Central America and Dominican Republic was convened to: a) describe adult immunization practices in these countries; b) discuss challenges and barriers to adult vaccination; and c) find strategies to increase awareness about VPDs. The advisory board discussions reflect that national immunization guidelines typically do not include routine vaccine recommendations for all adults, but rather focus on those with risk factors. This is the case for influenza, pneumococcal, and hepatitis B immunizations. Overall, knowledge lacks about the VPD burden among health-care professionals and the general public. Even more, there is insufficient information on vaccinology for students in medical schools. Actions from the responsible authorities – medical schools and scientific societies which can advocate for vaccination and a better knowledge in vaccinology – can help address these issues. A preventive medicine culture in the workplace may contribute to the advancement of public opinion on vaccination. Promoting vaccine education and research could be facilitated via working groups formed by disease experts, public and private sectors, and supranational authorities, in an ethical and transparent manner.

KEYWORDS: Adult immunizations, Caribbean, Central America, hepatitis B, herpes zoster, influenza, pneumococcal, Tdap, Td, vaccines

Introduction

A demographic transition has been recorded worldwide including Latin America and the Caribbean.1 According to the Latin American and Caribbean Demographic Center, the population aging intensifies due to the combination of sustained mortality decrease and a rapid decline in fertility.2 It is expected that by 2050, the proportion and absolute number of adults above the age of 65 will exceed the population of children under the age of 15.2 Life expectancy at birth continues to rise and is projected to increase from 75.2 years in 2015–2020 to 79.7 years in 2040–2045, for both sexes.3

As the population ages, the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) shifts to adults and older adult population groups.4 Because of co-morbidities, and immunosenescence, with age, people become increasingly vulnerable to infectious illnesses, many of which are VPDs.5,6 Moreover, infectious diseases further augment adults’ risk of chronic diseases, mortality, and disability.7–11 In addition to the disease burden, VPDs impose a considerable economic cost. In the United States in 2013, the yearly economic burden related to the four primary VPDs among persons aged 50 years and older, namely influenza, pneumococcal illness, herpes zoster, and pertussis, was $26.5 billion.12 This cost is predicted to rise substantially during the next 30 years as a result of population growth and changes in age distribution.13 Unvaccinated individuals accounted for 80% of the overall economic burden produced by VPDs in adults aged 19 and older, according to another economic cost model.14 On the contrary, higher vaccination coverage is associated with a considerable reduction in adult illnesses and billions in cost savings associated with avoided disease.15

Nonetheless, unlike childhood immunization, adult vaccination was not a health priority for the public or health authorities for decades.7,16,17 Adult vaccination rates are low worldwide due to a lack of vaccination recommendations, reimbursement and infrastructural constraints, vaccine hesitancy, and a lack of knowledge and education about the benefits of vaccination.5–16–19

The World Health Organization (WHO) has considered, more than a decade ago, that the increased risks from VPDs along with the benefits of preventive illness in older individuals both necessitate a “life-course approach” and the development of a corresponding vaccination schedule that would involve adults.5,7 However, a recent study of health systems in 194 WHO member states revealed a dearth of adult vaccination programs in 38% of countries.20 In the Americas WHO region, 91.4% of countries (32) reported influenza immunization programs, 88.6% (31) hepatitis B immunization, 31.4% (11) pneumococcal polysaccharide immunization, 11.4% (4) herpes zoster immunization, and 5.7% (2) pneumococcal conjugate immunization.20 There is a scarcity of data on adult vaccine coverage in the region, with existing evidence showing substantial variability among regions.21 According to the latest Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) data regarding adult vaccine coverage, the 2018 influenza vaccine coverage among adults varied from 32% in Uruguay, or 34% in Paraguay to 100% in Ecuador, Panama, and Argentina, while data were not available from most countries in the Central America and Caribbean region.21 A variety of factors contribute to low vaccine coverage: supply and access issues, lack of knowledge on adult vaccination guidelines by the public and health-care professionals (HCP) —including vaccines HCP themselves should receive—, and regulators’ lack of understanding of the associated disease and cost burden.22,23

In the current era, adult immunization has become a priority for public health.24 A coordinated effort among all stakeholders is required to implement a “life-course approach” to immunization and strengthen vaccination policies involving adults.5,7,24 In the Immunization Agenda 2030, the WHO acknowledges as strategic priority the life-course immunization goal,25 a priority that has been dramatically highlighted by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic impact on unvaccinated adults.26,27 Following the COVID-19, it is vital to extensively communicate the need for adult vaccinations besides COVID-19 vaccine and to establish strategies to address the associated barriers.19,28,29

An Advisory Board was organized to discuss current situation and recommendations related to adult vaccination in the Central America and the Caribbean region. The objectives of the meeting were to:

Describe current adult immunization practices in participating countries.

Discuss the challenges and the barriers for adult vaccination in these countries.

To find strategies to increase awareness of VPDs and adult vaccination among population, HCPs, and health authorities.

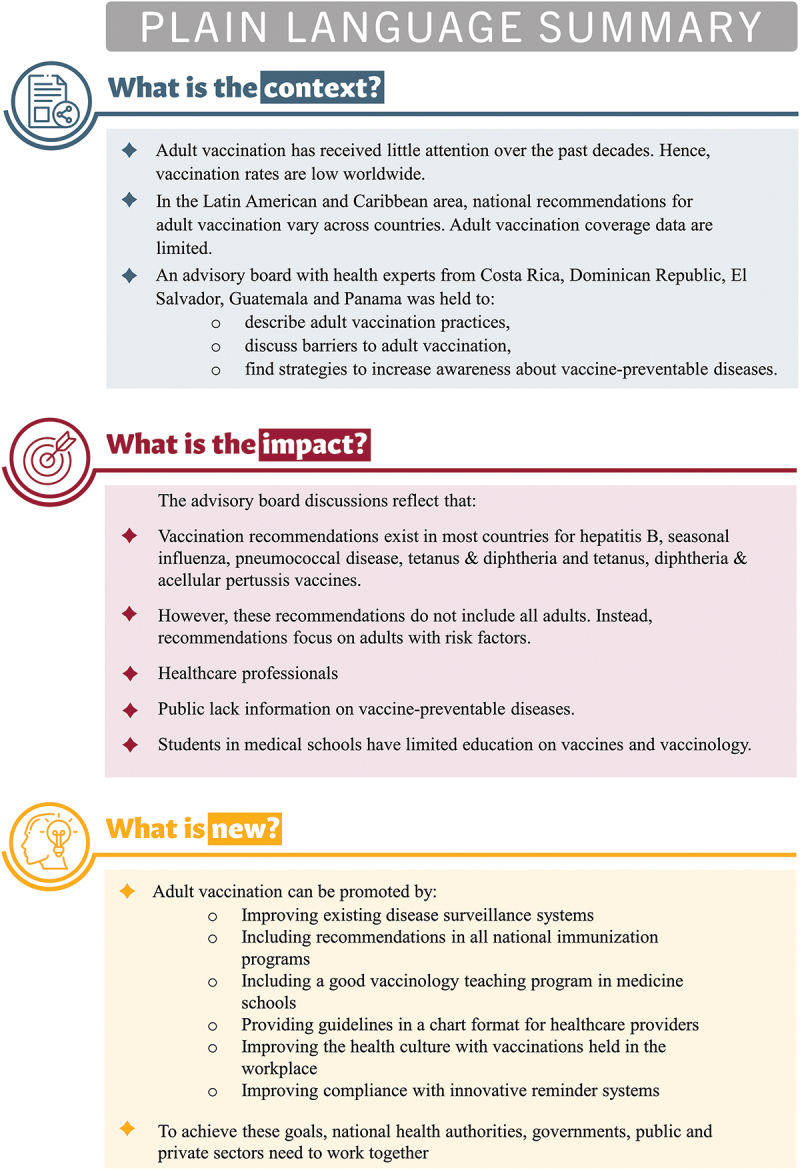

A lay summary of the study context, objectives and main findings can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Plain language summary.

Methods

Meeting setting

The Advisory Board meeting was virtually held on 9 December 2021. Eight experts (Table 1) on infectious diseases, pulmonology, geriatrics, occupational health, and public health from Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama, and Dominican Republic participated to the meeting. Medical and epidemiology experts from GSK facilitated the meeting organization and execution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Advisory board meeting participants.

| Name, country | Area of specialty | Current affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Fernando Coto, Costa Rica | Gerontology | Professor at the School of Medicine and the postgraduate School of Geriatrics and Gerontology at the University of Costa Rica |

| Carlos Rodriguez, Dominican Republic | Adult infectious diseases |

|

| Jorge Ramírez, El Salvador | Internal medicine, pulmonology |

|

| Telma Hernández, Guatemala | Clinical pharmacology/Occupational health and safety |

|

| Nancy Sandoval, Guatemala | Internal medicine and infectious diseases |

|

| Itza Barahona, Panama | Preventive medicine and public health |

|

| Reynaldo Chandler, Panama | Pulmonology |

|

| Ana Belén Araúz, Panama | Infectious diseases and internal medicine |

|

| Laura Naranjo | Pediatric infectious diseases Vaccines |

Advisory board meeting role: chair Investigator of SNI – Senacyt – Panama |

| Elidia Domínguez | Pediatric vaccines |

Advisory board meeting role: co-chair |

| Adriana Guzman Holst | Epidemiology |

Advisory board meeting role: presenting adults VPDs epidemiology data |

| Ingrid Leal | Vaccines | Lead Publications manager |

| Maria Mercedes Castrejón | Pediatric infectious diseases |

Advisory board meeting role: presenting adult NIPs and vaccine coverage evidence |

| Andrea Castrellon | Medical Coordinator |

Advisory board meeting role: Logistic & technical support |

Abbreviations: NIP, national immunization program; VPD, vaccine-preventable disease.

Guiding questions

The meeting was organized based on a predetermined agenda. Each expert made a presentation covering the following guiding questions:

- In your practice, what is your knowledge or your perception of the burden of adult diseases such as pneumococcus, influenza, pertussis, and herpes zoster?

- What are the challenges in the current surveillance for adult diseases and how can it be improved?

- What type of adult vaccines and VPDs do you observe the most in your daily practice?

- Review the national immunization programs (NIP) for adult vaccination in your country. How do you think the respective vaccination calendar should be improved?

- Are there some differences among recommendations from public and private sector?

- Describe the challenges and barriers for adult vaccination in your country:

- Infrastructure

- Perception of disease risk in patients with comorbidities

- Underreporting or misdiagnosis of adult diseases

What do you think are the best approaches and strategies to increase adult disease awareness and vaccination in the general public and among HCPs? How could these be implemented and who should be involved?

- The role of scientific societies:

- Do you think scientific societies may influence the national recommendation in your country?

- Which of them could be the biggest influencer?

Findings

Current adult immunization practices

National immunization programs

The NIPs in each of the participating countries contain some recommendations for adults (Table 2). These recommendations typically only involve influenza, tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis, pneumococcal, and hepatitis B vaccinations and they are not recommended for all individuals, but rather for those who have risk factors, such as chronic medical conditions (Table 2).30–37–39

Table 2.

Recommendation for adults’ vaccination included in the national immunization programs, per country.

| Country | Hepatitis B | Influenza, seasonal | Pneumococcal | Tdap/Td | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominican Republic30 |

|

|

Tdap: pregnant women at 27 week [Pilot in three country regions] Td:

|

Yellow fever:

|

|

| Costa Rica31,32 |

|

|

|

Tdap: pregnant women at 3rd trimester Td: every 10 y |

|

| El Salvador33,34 |

|

|

|

Tdap:

Td:

|

|

| Guatemala35,36 |

|

|

Tdap & Td:

|

Yellow fever: risk groups ≤59 y | |

| Panama37,38 |

|

|

|

Tdap:

Td:

|

Measles and rubella:

|

Abbreviations: Td, tetanus & diphtheria vaccine; Tdap, tetanus, diphtheria & acellular pertussis vaccine; y, year(s).

aSource, NIP 2008:38 healthcare workers, people with kidney problems who need dialysis, people in need of regular blood transfusions, people living in prisons, asylums.

b: Source, WHO (2020):32-36 includes healthcare workers, pregnant women, patients with chronic conditions.

Some considerations were expressed by the experts. In Costa Rica, the social security covers 90% of the population40 and the vaccine coverage is around 90% for tetanus and diphtheria (Td), pneumococcal, tetanus, diphtheria & acellular pertussis (Tdap) and influenza vaccines.41 However, in 2021, the goal of 80% seasonal influenza vaccine coverage for all adults over 58 years of age was not reached. In Dominican Republic, influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are only for children and adult >65y with some special conditions. In the private market, HCPs follow CDC recommendations.

In El Salvador, NIP is focused on children under the age of five and individuals over the age of 60. However, even though pneumococcal vaccine is offered for all population at risk (Table 2), there is not always availability for 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) for that population. Tdap and influenza vaccines are recommended to pregnant women. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are being administered in the private sector, mostly to people with chronic respiratory diseases or other risk factors.

In Guatemala, pregnant women receive the influenza and Tdap vaccines. The Ministry of Health and Social Security recommends vaccination against influenza and pneumococcus for high-risk adults above the age of 65. There are recommendations for available vaccines included in NIP for all targeted people under Social Security system. The Labor association conducts annual influenza vaccination campaigns and educate employees about VPDs and their economic impact in the workplace.

Panama has one of Latin America’s best immunization programs (Table 2), Meningococcal vaccine is available in the National Immunization Program for high-risk groups and for outbreak’s containment. This vaccine is also available in the private health-care sector.

According to Ministry of Health in Panama, adult vaccination programs are split into two categories: one for adults aged 20–59 years and another for seniors aged 60 years and above.38 In 2020, vaccine coverage in older adults (>60 years) was 99% for influenza and 88% for pneumococcal vaccines (21 June 2022, instant message from Panama EPI Head MINSA to Dr. Itza Barahona de Mosca).

Additionally, the Panamanian NIP addresses the need to minimize the number of missed opportunities to vaccinate by supporting the simultaneous administration of more than one type of vaccine. However, some factors (dress style, transportation, business hour, wait time) can negatively influence the opportunities for getting vaccination. Additionally, pursuant to a 2007 law, all universities should require students to provide proof of immunization status. The private health sector adheres to the recommendations of the Ministry of Health but there are no specific facilities to vaccinate adults.

The role of scientific societies

In Costa Rica, scientific societies are actively involved in raising public awareness, and the Societies of Infectious Diseases, Immunology, Internal Medicine, and Pneumology may collaborate on developing recommendations. Similarly, in the Dominican Republic, alike scientific associations may offer guidance on adult vaccination although they do not currently provide any relevant recommendations. Scientific societies provide Continuing Medical Education seminars in El Salvador that include immunization-related topics.

In Guatemala, Internal medicine, Infectious disease, Labor medicine, and Geriatric Medical Associations all promote vaccination recommendations. Similarly, Panama’s pertinent scientific societies collaborate to provide recommendations. Certain disciplines involved in primary care (public health, family medicine, pediatrics, geriatrics, internal medicine, and labor medicine) can readily promote vaccination advocacy. Obstetrician and Gynecology society gives guidelines regarding vaccines recommendation in pregnant women.42 “Ciencia en Panama”43 is an organization of scientists working to promote and disseminate science versus anti-science.

With the exception of the Dominican Republic, all other Advisory Board countries have their own National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAG), which include representative members of local scientific societies. These NITAGs are members of the global NITAG network.44

Barriers and challenges for adult vaccination

The first cluster of adult vaccination barriers consists of those imposed by a lack of governmental and administrative requirements addressing adult immunizations (Table 3). They include pertinent laws, a lack of social security reimbursement, lack of appropriate structure and logistics for organizing adult vaccination: there are not enough health-care facilities in remote and rural areas capable of administering immunizations.

Table 3.

Main findings by thematic category.

| Current adult immunization practices | |

|---|---|

NIP

|

Scientific societies • Infectious Diseases, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Pneumology Labor Medicine, and Geriatrics medical associations generally promote vaccination awareness among the public in all countries • Some involvement in advising immunization recommendations • Some involvement in relevant Continuous Medical Education, in collaboration with public and private health sectors |

| Barriers & challenges | |

Disease burden perceptions

Public Health

|

HCPs

General public

|

| Suggested strategies | |

Public Health

|

HCPs

General public

|

Abbreviations: HCPs, healthcare professionals; NIP, national immunization program; VPDs, vaccine-preventable diseases; y, year(s).

Another cluster pertains to the attitudes and practices of HCPs about adult vaccines (Table 3). HCPs frequently have poor beliefs on the importance of adult immunizations, miss chances to vaccinate adults, and frequently fail to identify VPDs. They also underreport cases, adding to the general misconception about VPD prevalence among adults.

The final cluster of barriers involves the general public, that does not have a culture for primary care. Adults seldom seek prompt medical attention for any ailment, and they generally do not have a family doctor or a general practitioner consultant. The general public has a poor knowledge of disease burden, limited access to credible information, and is vaccine hesitant. Furthermore, those who want to get vaccinated may face transportation issues, and insurance companies often do not cover immunizations in adults. Under these conditions, anti-vaxxers gain a presence in social media disseminating misinformation and false messages.

Disease burden perception

Some consistent findings across all countries were the lack of adequate adult VPD surveillance systems (Table 3), and the few available reports on mortality and morbidities related to adult VPDs in the region. There is also limited access and low interest for healthcare and vaccination, even with the short adult vaccination schedules that are available in almost all participating countries. On the other hand, the pandemic of COVID-19 has shifted the public opinion in favor of adult immunization by raising awareness among the public and HCPs about the need of adult vaccination.

Costa Rica

The most common infectious diseases among adults in Costa Rica are pneumococcal disease and influenza, followed by herpes zoster mainly in people >80 years old. Pertussis is not included in the differential diagnosis for routine clinical examination in adults, and respective diagnostic tests can be performed solely on the basis of a clinician’s suspicion. The symptoms of chronic and infectious diseases in older adults might differ from the classic description, then there are under recognition, delay and inaccurate diagnosis with a worse prognosis.

Dominican Republic

In Dominican Republic, there are limited data of infectious diseases burden in adults due to poor availability of diagnosis test in public sector. The most common diseases in this population are pneumococcal disease, influenza, herpes zoster, hepatitis B, and hepatitis A. Pertussis is not diagnosed in the public setting due to the cost of respiratory panel tests, in contrast to private sector. Knowing VPDs burden is important due to the cost they represent, and this was demonstrated in a study performed by Dr. Rodriguez’s group,45 showing that treating bacterial pneumonia introduces a substantial economic burden on the healthcare system. The estimated direct medical cost in average was US$ 84,06 for outpatient care, US$ 550,74 for hospital attention, US$ 955,68 for intensive care unit (ICU) attention, and around US$ 4,000 for patients with invasive pneumonia or sepsis.45

El Salvador

In El Salvador, the reporting of respiratory illness cases is inaccurate, and the definition of cases within the surveillance system is not explicit, since it encompasses a broad range of respiratory syndromes. Respiratory infection tests are only available in restricted quantities in the public sector, and they are primarily utilized to diagnose influenza. Herpes zoster is more likely to be diagnosed in adults with underlying medical conditions.

Public awareness of infectious diseases is low, and people often confuse their symptoms with those of a common cold. This makes them only seek medical help when their symptoms become more severe.

Guatemala

There is no active national epidemiologic surveillance in Guatemala, nor a requirement for mandatory reporting of several vaccine-preventable diseases (i.e influenza, pneumococcus, herpes zoster), and microbiological diagnosis is not commonly conducted. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, pneumonia was the second most frequently diagnosed infectious disease among patients in internal medicine service of Hospital Roosevelt.46 In contrast, during the pandemic era, pneumonia was in the sixth place. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) and influenza virus were also detected at that time. Pertussis is perceived as an illness that affects exclusively children and is unrecognized in adults, whereas herpes zoster is perceived as a disease associated with stress in the labor setting. Post herpetic neuralgia is a diagnosis in outpatients and influenza vaccination campaigns are taking place in the workplaces.47

Panama

Overall, microbiological detection of infectious lung diseases is quite poor in Panama. Multiplex testing is expensive, making it difficult to diagnose infectious illnesses in the public health sector. This suggests that there are more cases that are not reported. As a result, only a few sentinel surveillance data give any epidemiological information on adult respiratory infections. It is noteworthy that among the first five causes of death in 2018 in the country, “Pneumonia” is observed as the second cause of death only in Comarca Kuna, with a rate of 33.2 per 100,000 habitants. This finding calls for a comprehensive analysis due to disparities in the country.48

Adults do not seek for preventive health-care attention frequently. In 2019, 13.7% of adults between 20 and 59 y and 15% of adults >60 y sought for preventive health-care attention.49

Pertussis is not promptly recognized, and availability to diagnostic tests is restricted. Cases are rarely reported, but some outbreaks have occurred in indigenous communities. Herpes zoster is mainly reported among outpatient with the human immunodeficiency virus, and may go unreported in other settings.

Nonetheless, the geriatric population has a good awareness of pneumococcal disease and influenza, the two most common diseases afflicting this age group. Influenza awareness is high, due to effective yearly influenza vaccination efforts and the widespread availability of diagnostic testing.

Discussion

The Advisory Board experts identified low perception among HCPs and general public of the needs for vaccination and of the risk factors of VPDs in adults. Furthermore, there is a shortage of relevant provisions within the applicable Public Health legislation. Disease surveillance is inadequate, concealing the associated disease burden.

Future directions and related recommendations were made by the experts based on the discussed findings. These could be grouped in the same three clusters respective to the barriers and challenges (Table 3).

Strategies to increase adult disease awareness and vaccination

Public health

At the regulatory and administrative level of public health in the region, provisions should be established to promote adult vaccinations (Table 3). The first step is to emphasize the importance of adult immunization by including such recommendations in all NIPs. Second, the surveillance system should be modified to ensure the collection of reliable epidemiological data. The case notification network could be redesigned appropriately, and representatives from a variety of medical disciplines should be included in the case notification network to facilitate surveillance. Vaccine access must be improved, while also taking into account financial considerations. To contribute information on the economic impact of VPDs, health economic studies are necessary.

All experts agreed that after the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult morbidity and mortality, there is a need to reinforce primary care and develop adult vaccination programs considering also the vaccination in the workplace, which is compatible with the WHO Immunization Agenda 2030 and makes it highly relevant.25,50

National competent authorities could enhance their involvement in supranational organizations that develop policies impacting Latin America and the Caribbean.44,51 They could form working groups to develop immunization recommendations for adults in the region (Table 3).

HCPS

Continuous Medical Education would help keep HCPs up-to-date on the available evidence regarding VPDs in adults, advances in vaccine development, the relevance of incorporating vaccination into primary care systems, and the need to adequately monitor disease occurrence through a competent surveillance system.22–52–53,54 It is critical to align physicians, nurses, and other HCPs, on immunization criteria in order to maximize vaccination possibilities and minimize missed opportunities to vaccinate. In this way, Strategic Objective 3 of the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) calls for the benefits of immunization to be distributed equitably to all people. The PAHO wishes to make a standardized methodology to evaluate missed opportunities for vaccination, to improve vaccination services and to increase demand for vaccines.55 According to the discussion among experts, this might be aided by providing HCPs with vaccination guidelines in a chart format for use in routine clinical practice. It would likely be helpful to divide recommendations into groups ranging from younger to older adults, as well as by underlying conditions. This is because older adults are diverse, and their symptoms of chronic and infectious illnesses may differ from the standard description, resulting in delayed or inaccurate diagnosis and a poor prognosis.

General public

Several publications coincide with the experts in that a vaccination campaign or education and health promotion programs supported by recognized and respected sources – community leaders, doctors, scientists academics, public health authorities, researchers, and influencers in the countries – would be an effective strategy for reaching the adult population, and might contribute to increased public awareness of VPDs in adults.18,22,29 Simultaneously, authorities might leverage social media channels to aggressively spread trustworthy information in response to anti-vaxxers’ disinformation.22–56–58 The efficacy and safety of vaccines should be communicated in plain language, with crucial points contained inside infographics or animations.57–60

To encourage individuals to adhere to vaccination regimens, reminders are helpful.61 Enhanced vaccination cards with reminders or smartphone applications could be developed as innovative strategies to help individuals adhere to schedules.

Conclusions

In the countries represented in this Advisory Board, there is a significant lack of accessible evidence about VPDs. This parallels a significant awareness gap about the burden induced by VPDs, both among the adult population and HCPs. These unmet demands can be addressed by appropriate measures on the part of competent authorities and scientific societies, both of which can play a significant role in vaccine advocacy, including through a good vaccinology teaching program in medicine schools. A preventive medicine culture fostered in the workplace might aid in advancing public attitudes about vaccination. Each country’s experts might form working groups with the public and private sectors and the supranational authorities, to promote vaccination education for HCPs and the general adult population, and to conduct studies on VPDs, including health economics studies. This will help increase the knowledge of vaccines and vaccination.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andrea Castrellon for all logistic and advisory board coordination. The authors also thank the Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Athanasia Benekou provided medical writing support.

Funding Statement

GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA funded this study/research and was involved in all stages of study conduct, including analysis of the data. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA also took in charge all costs associated with the development and the publishing of the present manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AdBoard

Advisory Board

- COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- HCPs

healthcare professionals

- NIP

national immunization program

- VPDs

vaccine-preventable diseases

- WHO

World Health Organization

- PAHO

Pan American Health Organization

Author contributions

All authors participated in the discussion and the development of this manuscript. All authors had full access and gave final approval before submission.

Disclosure statement

LN, ED, MMC, IL and AGH are employees of GSK. ED, MMC, IL and AGH hold shares in company.

All authors received fees from GSK for the conduct of this advisory board. All authors declare no other financial and non-financial relationships and activities.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current work.

References

- 1.Turra CM, Fernandes F.. Demographic transition: opportunities and challenges to achieve the sustainable development goals in Latin America and the Caribbean. Project Documents, (LC/TS.2020/105), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC); 2020. [accessed 2022 Apr 11]. https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/46261.

- 2.Latin America and the Caribbean to reach maximum population levels by 2058. United Nations, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean; 2019. [accessed 2022 Mar 16]. https://www.cepal.org/en/pressreleases/latin-america-and-caribbean-reach-maximum-population-levels-2058.

- 3.CEPALSTAT Statistical Databases and Publications . Demographic and social. United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). 2021. [accessed 2022 June 30]. https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/dashboard.html?theme=1&lang=en.

- 4.Sauer M, Vasudevan P, Meghani A, Luthra K, Garcia C, Knoll MD, Privor-Dumm L. Situational assessment of adult vaccine preventable disease and the potential for immunization advocacy and policy in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2021;39:1556–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teresa Aguado M, Barratt J, Beard JR, Blomberg BB, Chen WH, Hickling J, Hyde TB, Jit M, Jones R, Poland GA, et al. Report on WHO meeting on immunization in older adults: Geneva, Switzerland, 22–23 March 2017. Vaccine. 2018;36:921–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eilers R, Krabbe PFM, van Essen TGA, Suijkerbuijk A, van Lier A, de Melker HE. Assessment of vaccine candidates for persons aged 50 and older: a review. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas-Crusells J, McElhaney JE, Aguado MT. Report of the ad-hoc consultation on aging and immunization for a future WHO research agenda on life-course immunization. Vaccine. 2012;30:6007–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang SY, Li HX, Yi XH, Han GL, Zong Q, Wang MX, Peng XX. Risk of stroke in patients with Herpes Zoster: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:301–07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manousakis G, Jensen MB, Chacon MR, Sattin JA, Levine RL. The interface between stroke and infectious disease: infectious diseases leading to stroke and infections complicating stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009;9:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saberi A, Akhondzadeh S, Kazemi S, Kazemi S. Infectious agents and stroke: a systematic review. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2021;12:427–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sisniega DC, Reynolds AS. Severe neurologic complications of SARS-CoV-2. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2021;23:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin JM, McGinnis JJ, Tan L, Mercatante A, Fortuna J. Estimated human and economic burden of four major adult vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States, 2013. J Prim Prev. 2015;36:259–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talbird SE, La EM, Carrico J, Poston S, Poirrier J-E, DeMartino JK, Hogea CS. Impact of population aging on the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases among older adults in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:332–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozawa S, Portnoy A, Getaneh H, Clark S, Knoll M, Bishai D, Yang HK, Patwardhan PD. Modeling the economic burden of adult vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:2124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrico J, Talbird SE, La EM, Poston S, Poirrier JE, DeMartino JK, Hogea C. Cost-Benefit analysis of vaccination against four preventable diseases in older adults: impact of an aging population. Vaccine. 2021;39:5187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doherty TM, Del Giudice G, Maggi S. Adult vaccination as part of a healthy lifestyle: moving from medical intervention to health promotion. Ann Med. 2019;51:128–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan L. Adult vaccination: now is the time to realize an unfulfilled potential. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:2158–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Gomensoro E, Del Giudice G, Doherty TM. Challenges in adult vaccination. Ann Med. 2018;50:181–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Privor-Dumm LA, Poland GA, Barratt J, Durrheim DN, Deloria Knoll M, Vasudevan P, Jit M, Bonvehí PE, Bonanni P. A global agenda for older adult immunization in the COVID-19 era: a roadmap for action. Vaccine. 2021;39:5240–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams SR, Driscoll AJ, LeBuhn HM, Chen WH, Neuzil KM, Ortiz JR. National routine adult immunisation programmes among World Health Organization member states: an assessment of health systems to deploy COVID-19 vaccines. Euro Surveill. 2021;26:2001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization . Influenza vaccine coverage in countries and territories of the Americas - adults. 2018. [accessed 2022 Mar 26]. http://ais.paho.org/imm/InfluenzaCoverageMap.asp.

- 22.Badur S, Ota M, Öztürk S, Adegbola R, Dutta A. Vaccine confidence: the keys to restoring trust. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:1007–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barratt J, Mishra V, Acton M. Latin American adult immunisation advocacy summit: overcoming regional barriers to adult vaccination. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31:339–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonanni P, Bonaccorsi G, Lorini C, Santomauro F, Tiscione E, Boccalini S, Bechini A. Focusing on the implementation of 21st century vaccines for adults. Vaccine. 2018;36:5358–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . Immunization Agenda 2030: a global strategy to leave no one behind. 2020. [accessed 2022 Mar 23]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/strategy/ia2030/ia2030-draft-4-wha_b8850379-1fce-4847-bfd1-5d2c9d9e32f8.pdf?sfvrsn=5389656e_69&download=true.

- 26.Johnson AG, Amin AB, Ali AR, Hoots B, Cadwell BL, Arora S, Avoundjian T, Awofeso AO, Barnes J, Bayoumi NS, et al. COVID-19 incidence and death rates among unvaccinated and fully vaccinated adults with and without booster doses during periods of Delta and Omicron variant emergence — 25 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4–December 25, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:132–38. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang LL, Kuo HS, Ho HJ, Wu CY. COVID-19 vaccinations are associated with reduced fatality rates: evidence from cross-county quasi-experiments. J Glob Health. 2021;11:05019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindstrand A, Cherian T, Chang-Blanc D, Feikin D, O’Brien KL. The world of immunization: achievements, challenges, and strategic vision for the next decade. J Infect Dis. 2021;224:S452–S67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antonelli-Incalzi R, Blasi F, Conversano M, Gabutti G, Giuffrida S, Maggi S, Marano C, Rossi A, Vicentini M. Manifesto on the value of adult immunization: “We know, we Intend, we advocate”. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization . Vaccination schedule for Dominican Republic. 2022. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/schedule-by-country/dom.html?DISEASECODE=&TARGETPOP_GENERAL=.

- 31.Esquema de vacunación official en Costa Rica Adultos. 2021. [accessed 2022 Apr 4]. https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/centro-de-informacion/material-comunicacion/vacunas-3/5350-esquema-de-vacunacion-oficial-en-costa-rica-adultos/file.

- 32.World Health Organization . Vaccination schedule for Costa Rica. 2022. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/schedule-by-country/cri.html?DISEASECODE=&TARGETPOP_GENERAL=.

- 33.Gobierno de El Salvador Ministerio de Salud . Esquema Nacional de Vacunación, El Salvador. 2021. [accessed 2022 Apr 4]. https://www.salud.gob.sv/servicios/esquema-nacional-de-vacunacion-el-salvador-2021/.

- 34.World Health Organization . Vaccination schedule for El Salvador. 2022. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/schedule-by-country/slv.html?DISEASECODE=&TARGETPOP_GENERAL=.

- 35.World Health Organization . Vaccination schedule for Guatemala. 2022. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/schedule-by-country/gtm.html?DISEASECODE=&TARGETPOP_GENERAL=.

- 36.Noticias IGSS . Vacunas para todos durante toda la vida. 2022. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://www.igssgt.org/noticias/2019/04/15/vacunas-para-todos-durante-toda-la-vida/.

- 37.World Health Organization . Vaccination schedule for Panama. 2022. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/schedule-by-country/pan.html?DISEASECODE=&TARGETPOP_GENERAL=.

- 38.Ministerio de Salud, República de Panamá . Esquema Nacional de Vacunación. 2021. [accessed 2022 June 29]. https://www.minsa.gob.pa/sites/default/files/programas/esquema-de-vacunacion2021_revision_14_de_septiembre.pdf.

- 39.República Dominicana, Secretaría de Estado de Salud Pública y Asistencia . Manual de procedimientos técnicos sobre las normas del PAI 2008: vacunas del PAI. 2008. [accessed 2022 Apr 4]. https://repositorio.msp.gob.do/handle/123456789/1367.

- 40.Castillo Rivas J Características de la cobertura de los seguros sociales de la Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social. 2012. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://www.inec.cr/sites/default/files/documentos/inec_institucional/publicaciones/anpoblaccenso2011-01.pdf_0.pdf.

- 41.Ministerio de Salud Costa Rica . Análisis de la Situación de Salud 2018. 2019. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ministeriodesalud.go.cr%2Findex.php%2Fbiblioteca-de-archivos-left%2Fdocumentos-ministerio-de-salud%2Fvigilancia-de-la-salud%2Fanalisis-de-situacion-salud%2F3600-analisis-de-situacion-salud-2018-1%2Ffile&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK.

- 42.Sociedad Panamenã de Obstetricia y Ginecología . 2022. [accessed 2022 June 29]. https://spogpanama.org/.

- 43.Ciencia en Panamá . 2022. [accessed 2022 Apr 11]. https://www.cienciaenpanama.org/.

- 44.National immunization technical advisory groups - members 2019. 2019. [accessed 2022 Apr 6]. https://www.nitag-resource.org/network/members.

- 45.Rodriguez-Taveras CJ, Abreu R, Badillo SD. PRS28 - cost of illness due to bacterial pneumonia in the adult population in Dominican Republic from a public perspective during 2018. Value Health. 2018;21:S408. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Memoria de Labores, Departamento de Medicina Interna Hospital Roosevelt. 2013. [accessed 2022 Jul 26]. https://docplayer.es/60917522-Memoria-de-labores-2013-departamento-de-medicina-interna-hospital-roosevelt.html.

- 47.Federación Centroamericana y del Caribe de Salud Ocupacional . Guía de Vacunación para los Trabajadores. 2018. [accessed 2022 June 29]. http://www.fecacso.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Guia-de-Vacunacion-Portada.pdf.

- 48.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo - Panamá . Cuadro 12. Defunciones y tasa de mortalidad de las cinco principales causas de muerte, por sexo, según provincia, comarca indígena de residencia y causa: año 2018. 2018. [accessed 2022 June 30]. https://www.inec.gob.pa/archivos/P0705547520191205111401Cuadro%2012.pdf.

- 49.Ministerio de Salud, República de Panamá . Cobertura y concentración de control de salud de adulto, en el Ministerio de Salud de la Republica de Panama, por grupo de edad, según región de salud y comarca indígena: año 2019. 2019. [accessed 2022 June 29]. https://www.minsa.gob.pa/sites/default/files/general/cuadro_33.pdf.

- 50.The Lancet. 2021: the beginning of a new era of immunisations? Lancet. 2021;397:1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan IL, Mowson R, Alonso JP, Roberti J, Contreras M, Velandia-González M. Promoting immunization equity in Latin America and the Caribbean: case studies, lessons learned, and their implication for COVID-19 vaccine equity. Vaccine. 2022;40:1977–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Madewell Z, Chacón-Fuentes R, Badilla-Vargas X, Ramirez C, Ortiz MR, Alvis-Estrada JP, Jara J. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices for the use of seasonal influenza vaccination, healthcare workers, Costa Rica. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021;15:1004–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34:6700–06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu PJ, Srivastav A, Amaya A, Dever JA, Roycroft J, Kurtz MS, O’Halloran A, Williams WW. Association of provider recommendation and offer and influenza vaccination among adults aged ≥18 years - United States. Vaccine. 2018;36:890–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) . Methodology for the evaluation of missed opportunities for vaccination. 2013. [accessed 2022 Apr 8]. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/49297.

- 56.Stahl JP, Cohen R, Denis F, Gaudelus J, Martinot A, Lery T, Lepetit H. The impact of the web and social networks on vaccination. New challenges and opportunities offered to fight against vaccine hesitancy. Med Mal Infect. 2016;46:117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization . Vaccination and trust. How concerns arise and the role of communication in mitigating crises. 2017. [accessed 2022 Apr 8]. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/329647/Vaccines-and-trust.PDF.

- 58.World Health Organization . Denmark campaign rebuilds confidence in HPV vaccination. 2018. [accessed 2022 June 30]. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/02-03-2018-denmark-campaign-rebuilds-confidence-in-hpv-vaccination.

- 59.Muzumdar JM, Pantaleo NL. Comics as a medium for providing information on adult immunizations. J Health Commun. 2017;22:783–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diamond J, McQuillan J, Spiegel AN, Hill PW, Smith R, West J, Wood C. Viruses, vaccines and the public. Mus Soc Issues. 2016;11:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bridges CB, Hurley LP, Williams WW, Ramakrishnan A, Dean AK, Groom AV. Meeting the challenges of immunizing adults. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:S455–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current work.