Keywords: methodology, transspinal evoked potentials, transspinal stimulation

Abstract

Transspinal stimulation modulates neuronal excitability and promotes recovery in upper motoneuron lesions. The recruitment input-output curves of transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) recorded from knee and ankle muscles, and their susceptibility to spinal inhibition, were recorded when the position, size, and number of the cathode electrode were arranged in four settings or protocols (Ps). The four Ps were the following: 1) one rectangular electrode placed at midline (KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery or K-LAB4Recovery; P-KLAB), 2) one square electrode placed at midline (P-2), 3) two square electrodes 1 cm apart placed at midline (P-3), and 4) one square electrode placed on each paravertebral side (P-4). P-KLAB and P-3 required less current to reach TEP threshold or maximal amplitudes. A rightward shift in TEP recruitment curves was evident for P-4, whereas the slope was increased for P-2 and P-4 compared with P-KLAB and P-3. TEP depression upon single and paired transspinal stimuli was pronounced in ankle TEPs but was less prominent in knee TEPs. TEP depression induced by single transspinal stimuli at 1.0 Hz was similar for most TEPs across protocols, but TEP depression induced by paired transspinal stimuli was different between protocols and was replaced by facilitation at 100-ms interstimulus interval for P-4. Our results suggest that P-KLAB and P-3 are preferred based on excitability threshold of motoneurons. P-KLAB produced more TEP depression, thereby maximizing the engagement of spinal neuronal pathways. We recommend P-KLAB to study neurophysiological mechanisms underlying transspinal stimulation or when used as a neuromodulation method for recovery in neurological disorders.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Transspinal stimulation with a rectangular cathode electrode (P-KLAB) requires less current to produce transspinal evoked potentials and maximizes spinal inhibition. We recommend P-KLAB for neurophysiological studies or when used as a neuromodulation method to enhance motor output and normalize muscle tone in neurological disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Spinal cord stimulation has gained prominent attention in the scientific community, with research investigations spanning from animals to humans and from mathematical modeling to intraspinal, epidural, and transcutaneous (i.e., transspinal) delivery of electrical current to affect motor, locomotor, respiratory, and bladder function in upper motoneuron lesions (1–14).

The spinal cord serves as an integration center for descending and ascending neuronal signals (15). Therefore, transspinal stimulation has the potential to produce functional neuroplasticity of both brain and spinal cord neuronal circuits. Indeed, transspinal stimulation used as a treatment regimen affects cortical and corticospinal excitability (16, 17), decreases soleus H-reflex excitability, restores spinal inhibition (18), and produces uncoordinated or coordinated rhythmic motor activity in paralyzed patients (14, 19, 20). Transspinal stimulation with a single monophasic pulse generates compound muscle action potentials or transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) in leg muscles that either summate or eliminate motor evoked potentials (MEPs), M waves, and H reflexes based on the relative timing between the two associated stimuli (21, 22). These findings support that transspinal stimulation may use common neuronal pathways to the monosynaptic soleus H reflex.

Transspinal stimulation is currently used widely as a noninvasive method to promote neuromodulation and neurorecovery in upper motoneuron lesions (23–28). Because of the potential use of transspinal stimulation as a rehabilitation strategy, there is a great need to establish an optimal protocol regarding the position, size, and number of the cathodal stimulating electrodes based on neurophysiological properties of motoneurons and spinal neuronal circuits. Transspinal stimulation over the thoracolumbar region has been administered with 1 single square electrode placed over the spinal process at midline (29), a 9-electrode array spanning from Thoracic 10 to Lumbar 1 delivering single or paired pulses (30) or a 21-electrode array placed at Thoracic 11–12 delivering biphasic pulses (31), a silver-chloride electrode over Thoracic 11–12 spinal process (32), and a 0.25-cm round electrode (33). Because of the distribution of current and possible activation of different spinal circuits or excitability thresholds for dorsal root afferents and dorsal column axons (34, 35), comparison of results across studies is difficult. A recent study reported that motor thresholds, onset latency, and strength of paired stimuli-induced depression are not significantly different when cathodal stimulation is delivered with one or two electrodes (36).

A fundamental lack of knowledge regarding an optimal protocol for position, size, and number of the cathode electrode based on neurophysiological properties of motoneurons is apparent. To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has investigated the physiological effects of different transspinal stimulation electrode position, size, and number in humans. The purpose of this study was to establish excitability threshold and gain from the recruitment input-output TEP curves and the strength of spinal inhibition exerted on TEPs recorded bilaterally from knee and ankle muscles when the position, size, and number of the cathodal electrode placed over the thoracolumbar region varied. We investigated physiological differences when the position, size, and number of the transspinal cathodal electrode was arranged in four different settings, termed protocols. The four protocols were the following: 1) one cathodal rectangular electrode placed at midline (KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery/K-LAB4Recovery/P-KLAB), 2) one square electrode placed at midline (protocol 2; P-2), 3) two square electrodes 1 cm apart placed at midline (protocol 3; P-3), and 4) one square electrode placed on each paravertebral side (protocol 4; P-4).

The TEP recruitment input-output curves follow an S shape, in a manner similar to that described for the H reflex, M wave, and MEPs (10, 21, 30, 37, 38) consistent with the intrinsic properties of spinal motoneurons. We also established the strength of spinal inhibition exerted on TEPs. The rationale was that TEP depression following single transspinal stimuli at 1.0 Hz (compared with 0.1 Hz) and paired transspinal stimuli may rely on spinal neuronal mechanisms similar to those described for the soleus H reflex. It is well known that the soleus H-reflex depression upon single stimuli at 1.0 Hz compared with 0.1 Hz is purely homosynaptic and is largely due to decrease in the amount of neurotransmitters at the Ia-motoneuron synapse, depletion of releasable vesicles, failure of action potential conduction at axonal branches, decrease in presynaptic quantal size, and adaptation of exocytosis machinery (39–45). Paired stimuli at interstimulus intervals (ISIs) that vary from 30 up to 500 ms produce pronounced soleus H-reflex depression that possibly is exerted at both presynaptic and postsynaptic levels. The distribution of such inhibition depends on the type of group I afferents and target motoneurons (38, 46).

Collectively, the objectives of this study were to establish the most optimal protocol between P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4 for transspinal stimulation over the thoracolumbar region based on the strength of spinal inhibition and excitability threshold of motoneurons over multiple segments in healthy humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Eleven (6 female, 5 male) healthy adults aged 23–34 yr (25.73 ± 5.19 yr), with an average height of 1.70 ± 0.11 m and mass of 70.15 ± 12.07 kg (mean ± SD), without evidence of past or present neurological, orthopedic, or chronic systemic disorders participated in the study. The experimental protocol was approved by the City University of New York (New York, NY) Institutional Review Board Committee (IRB No. 2019-0806) and was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before participation in the study.

Transspinal Stimulation

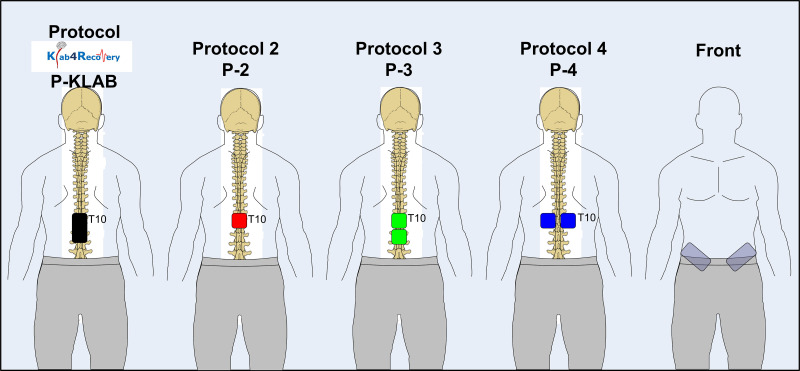

With subjects seated at the edge of a treatment table, the Thoracic 10 spinous process was identified via palpation and anatomical landmarks. The upper edge of the cathode electrode for all four protocols was placed on Thoracic 10 (Fig. 1). For P-KLAB, a single rectangle electrode (5 cm × 10 cm, model UF2040; Axelgaard Manufacturing, Fallbrook, CA) was placed at midline along the vertebrae equally between the left and right paravertebral sides covering from Thoracic 10 to Lumbar 1–2 vertebral levels. For P-2, a single square electrode (5 cm × 5 cm, model NP0222B; Hudson, OH) was placed at midline. For P-3, two single square electrodes (5 cm × 5 cm, model NP0222B; Hudson, OH) were placed at midline with 1-cm distance between them. Finally, for P-4 two single square electrodes (5 cm × 5 cm, model NP0222B; Hudson, OH) were placed on the left and right paravertebral sides. In all four protocols, the anode was a pair of interconnected reusable self-adhered electrodes (5 cm × 9 cm, model UF2040; Axelgaard Manufacturing, Fallbrook, CA) placed bilaterally on the iliac crests (21, 22, 47). All electrodes were affixed to the skin via Tegaderm transparent film (3M Healthcare, St. Paul, MN).

Figure 1.

Position, size, and number of transspinal cathode electrodes for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). For all 4 protocols the top edge of the electrode corresponded to Thoracic 10 (T10) vertebrae level. The space between the electrodes in P-3 and P-4 was 1 cm, while they were connected to act as 1 electrode in a manner similar to the anodes placed bilateral on the iliac crests. Body position is shown for representation purposes, as transspinal stimulation was delivered with subjects’ supine and both hips and knees flexed at 30°.

The cathode and anode electrodes were connected to a constant-current stimulator (DS7A; Digitimer, United Kingdom) that was triggered by Spike2 scripts (Cambridge Electronics Design Ltd., Cambridge, UK) to deliver single monophasic square-wave pulses of 1-ms duration. Transspinal stimulation was delivered while the participant lay supine with hips and knees flexed at 30° and ankles supported in a neutral position based on the significant effects of body position on amplitude and excitability threshold of TEPs (48). For all protocols, TEPs from all muscles were recorded at increasing stimulation intensities in steps of 0.5 mA, starting from below the right soleus (SOL) TEP threshold until increases in stimulation intensity did not alter the TEP amplitude further (i.e., maximum stimulation intensity). Four TEPs were recorded at each stimulation intensity. Furthermore, the strength of ankle and knee TEP depression in response to single and paired transspinal stimuli was also established. Specifically, TEPs from all muscles were recorded after single transspinal stimuli at 1.0, 0.33, 0.2, 0.125, and 0.1 Hz to establish differences in the strength of TEP depression following single stimuli at varying stimulation frequencies between protocols. TEPs were also recorded upon paired transspinal stimuli at the interstimulus intervals of 60, 100, 300, and 500 ms at 0.2 Hz to establish differences in the strength of TEP depression following paired stimuli between protocols. For both single and paired stimuli, transspinal stimulation was delivered at an intensity to evoke a right SOL TEP equivalent to 20–40% of the homonymous maximal TEP amplitude across subjects. In all cases, 12 TEPs were recorded. Orders of protocols and electrophysiological recordings within and across protocols were randomized for each subject via an electronic randomization generator.

Surface Electromyographic MG Recordings

A multichannel electromyographic (EMG) system (MA-300; Motion Lab Systems, Baton Rouge, LA) was used to record myoelectric signals with single differential bipolar surface electrodes (common mode rejection ratio > 100 dB, input impedance > 100 MΩ) from the rectus femoris (RF), vastus lateralis (VL), gracilis (GRC), medial hamstrings (MH), medial gastrocnemius (MG), SOL, tibialis anterior (TA), and peroneus longus (PL) muscles bilaterally after standard skin preparation. Surface electrodes were secured with Tegaderm transparent film (3M Healthcare, St. Paul, MN). EMG signals were low-pass filtered at 2,000 Hz and amplified (350× gain) before being sampled at 4,902 Hz with a Power 1401 and Spike2 data collection system (Cambridge Electronics Design Ltd., Cambridge, UK). EMG recordings were stored on a personal computer for offline analysis.

Data Analysis

The onset latency and duration of TEPs were estimated after transspinal stimulation with a single monophasic square-wave pulse of 1-ms duration delivered at 0.2 Hz (every 5 s). The latency and duration were estimated for each TEP separately from the nonrectified waveform averages of 12 sweeps. Onset latency was determined as the time between the onsets of stimulus and response. Duration was determined as the time from the latency onset until EMG returned to baseline.

The TEP amplitude was measured as the area under the full wave-rectified waveform from EMG signals (mV × ms). The recruitment curve, for each TEP separately, was plotted with the intensity on the x-axis and normalized area under the curve to the homonymous maximal amplitude. A Boltzmann sigmoid function (Eq. 1) was then fitted to the recruitment curve. In Eq. 1, m is the slope parameter of the function, S50 is the stimulus required to elicit a TEP equivalent to 50% of the maximal TEP (TEPmax), and s is the TEP amplitude at a given stimulus value. The TEP slope and stimuli corresponding to TEP threshold (TEPth) were estimated based on Eqs. 2 and 3, respectively. The predicted parameters of the sigmoid function were estimated by applying the Nash variant of Marquardt’s algorithm for nonlinear least squares (49).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

For each response, the predicted homonymous TEPth from the P-KLAB was used to normalize the raw stimulation intensity. This was done to reveal the real differences across protocols, because when stimulation intensities are normalized to the homonymous TEP threshold the effects are masked. After normalization, the TEP threshold values of P-KLAB had a mean value of 1 with no standard error of the mean. A sigmoid function was then fitted to each recruitment curve that both stimulation intensity and amplitude were normalized. For each response, averages from all participants were calculated in incremented steps of 0.05 from 0.5 up to 2.5 times the stimulation threshold.

Each TEP recorded from each muscle at 1.0, 0.33, 0.2, and 0.125 Hz was expressed as a percentage of the mean amplitude of the homonymous TEP recorded at 0.1 Hz and grouped across subjects per muscle and protocol. The TEP evoked by the second transspinal pulse at the interstimulus intervals of 60, 100, 300, and 500 ms at 0.2 Hz was expressed as a percentage of the mean amplitude of the homonymous TEP evoked by the first stimulus. Normalized TEPs were then grouped per muscle and stimulation protocol across all subjects.

Statistics

The robust regression and outlier method (Q = 0.1%) was used to identify and remove statistical outliers. Data analyzed with linear mixed-effect models with subject as the random factor produce random intercepts (offsets) for each subject. The mixed-effects model uses a compound symmetry covariance matrix and is fitted using restricted maximum likelihood. The mixed-effects model gives the same results as repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) if there are no missing values. When a significant effect was found, Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests were performed to establish significant pairwise differences. When necessary, lower case letter displays of Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests were used to report significant pairwise differences across levels of factors. Effect size for the pairwise comparisons was calculated with the unbiased Cohen’s d-applied Hedges’ correction (|d| < 0.2 negligible effects, |d| < 0.5 small effects, |d|< 0.8 medium effects; otherwise large effects) (50). Diagnostic plots were used to assess mixed-effects model assumptions of variance homogeneity and normality (residuals plotted against fitted values and quantile-quantile plots of residuals). For severe violations of mixed-effects model assumptions data underwent aligned rank transformation (51–53) before being analyzed with a mixed-effects model. Accordingly, Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests for aligned rank-transform models were implemented (54). Nagelkerke’s coefficient of determination R2 (analogous to the R2 in linear regression) was calculated and used to evaluate the performance of the Boltzmann sigmoid model. Mean R2 values and 95% coefficient intervals (CIs) were calculated via Fisher’s z transformation. For all statistical tests, the level of significance was set at α = 0.05. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla CA, 2022). Data processing was performed with R version 4.1.3 (55).

RESULTS

Latency and Duration of TEPs for P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4

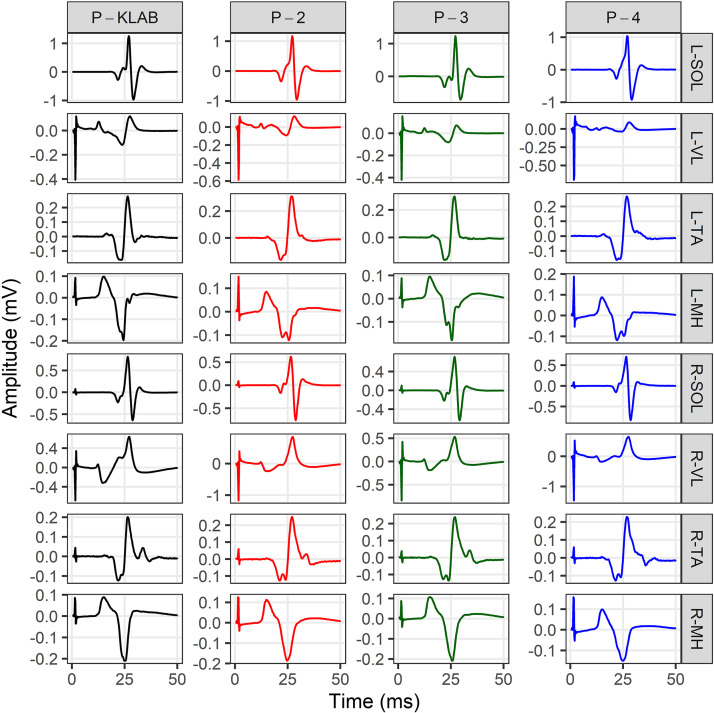

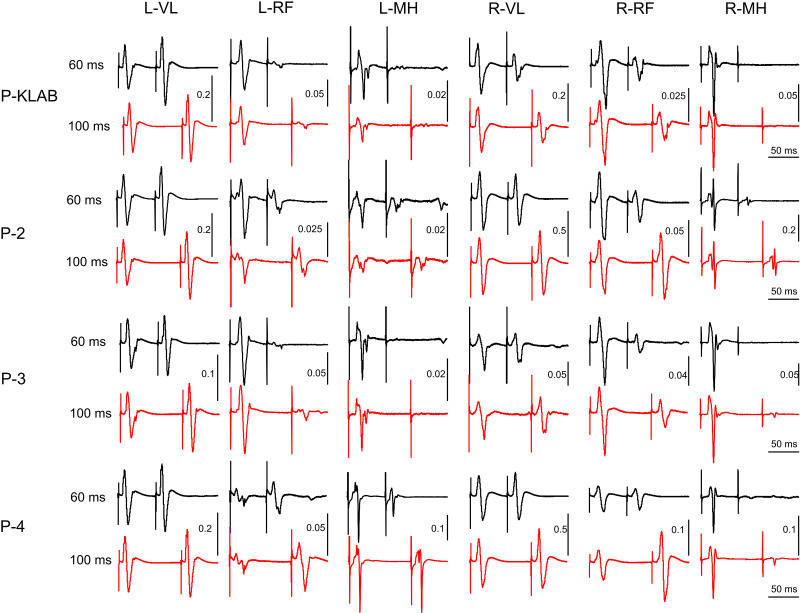

As we have extensively described in humans, transspinal stimulation with single monophasic pulses of 1-ms duration over the thoracolumbar region using the P-KLAB evokes TEPs in leg muscles with specific neurophysiological properties regarding shape, latency, and duration (21, 22, 56–58). These properties are clearly depicted on the representative nonrectified waveform averages of the left and right SOL, TA, VL, and MH TEPs recorded at each protocol’s maximum stimulation intensity (Fig. 2). Consistent with our previous observations, the TEP shape recorded from left and right homonymous muscles was similar, whereas the left/right SOL and TA TEP had a similar shape with P-KLAB and P-3. Furthermore, the TEP size was different across muscles, being larger in the left and right SOL and MH muscles and smaller in the left and right TA, a phenomenon observed across all four protocols. The required stimulation intensity to elicit TEPs of similar size was different across protocols. For the TEPs indicated in Fig. 2, the individual maximum stimulation intensity was 21.0 mA for P-KLAB, 27.5 mA for P-2, 23.5 mA for P-3, and 34.0 mA for P-4, suggesting that more current is needed with P-2 and P-4 to produce responses similar in amplitude to those produced by P-KLAB and P-3.

Figure 2.

Waveform averages (n = 4, evoked at 0.2 Hz) of transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) elicited at maximum stimulation intensity for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). TEPs recorded from the left (L) and right (R) soleus (SOL), tibialis anterior (TA), vastus lateralis (VL), and medial hamstring (MH) muscles from a single participant at maximum stimulation intensities of P-KLAB = 21.0 mA, P-2 = 27.5 mA, P-3 = 23.5 mA, and P-4 = 34.0 mA. Time 0 ms on the abscissa corresponds to the onset of transspinal stimulation. Stimulation artifacts are present mostly for responses recorded from knee muscles.

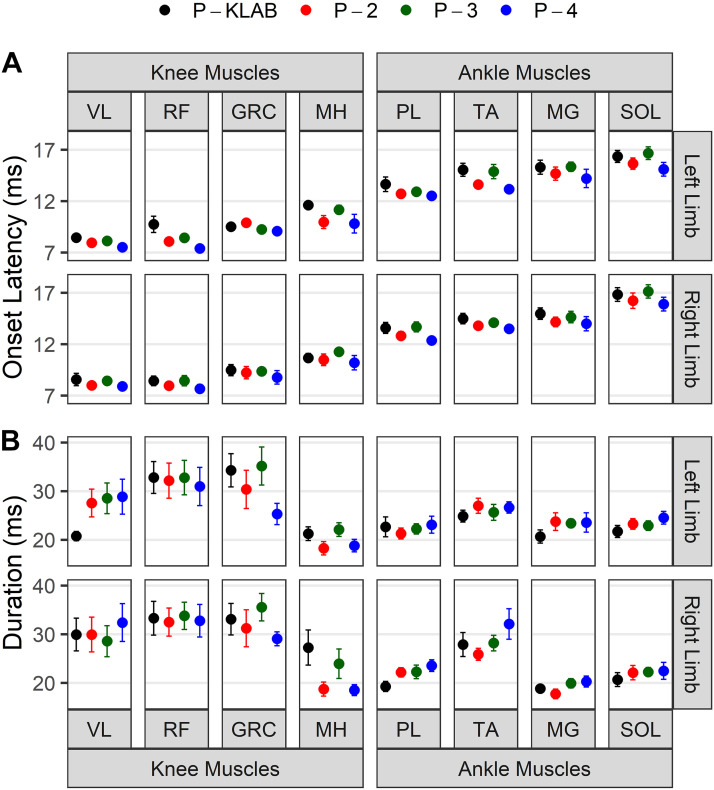

The mean onset TEP latencies recorded from all muscles, participants, and protocols are shown in Fig. 3A. The latency was estimated for each TEP separately when transspinal stimulation was delivered at 0.2 Hz. It is evident from Fig. 3A that the TEP onset latency for ankle muscles was longer than that of knee TEPs. For example, in the P-KLAB, the left and right SOL TEP (16.35 ± 0.59 ms and 16.84 ± 0.67 ms, respectively) latency was longer than that of left and right RF TEP (9.23 ± 0.70 ms and 8.78 ± 0.55 ms, respectively). This result reflects the proximity of the RF muscle to the stimulation site compared with the SOL muscle. A two-way, mixed-effects analysis showed a significant main effect of muscle (F15,150 = 85.35, P < 0.001) and protocol (F3,30 = 11.11, P < 0.001) on TEP onset latency, but a significant interaction between muscle and protocol was not found (F45,415 = 0.7126, P = 0.92). Tukey’s multiple comparisons test showed significant differences between P-KLAB and P-4 (P < 0.001, d = 0.34), P-KLAB and P-2 (P = 0.004, d = 0.207), P-2 and P-3 (P = 0.04, d = -0.155), and P-3 and P-4 (P = 0.001, d = 0.288). These significant differences were driven mostly by changes in latency in the left and right TA and left RF and left VL between P-KLAB and P-4 and between P-KLAB and P-2. The mean TEP durations recorded from all muscles, participants, and protocols are shown in Fig. 3B. The duration was estimated for each TEP when transspinal stimulation was delivered at 0.2 Hz. A two-way, mixed-effects analysis showed a significant main effect of muscle (F15,120 = 3.701, P < 0.001) but not between protocols (F3,24 = 1.745, P = 0.18), while a significant interaction between muscle and protocol was not found (F45,360 = 1.356, P = 0.07). Tukey’s multiple comparisons on muscle main effects revealed that the duration of TEPs recorded from right MG was significantly different from that of right VL (P = 0.02, d = −1.39), right RF (P = 0.001, d = −1.95), left RF (P = 0.008, d = −1.62), right GRC (P = 0.03, d = −1.83), and left GRC (P = 0.02, d = −1.52). These findings suggest that knee TEPs have longer action potentials than ankle TEPs.

Figure 3.

Latency and duration of transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Overall mean onset latency (A) and duration (B) in milliseconds of TEPs recorded from left and right ankle and knee muscles for all 4 study protocols. Error bars indicate the SE. GRC, gracilis; MG, medialis gastrocnemius; MH, hamstrings; PL, peroneus longus; RF, rectus femoris; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior, VL, vastus lateralis.

TEP Recruitment Input-Output Curves for P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4

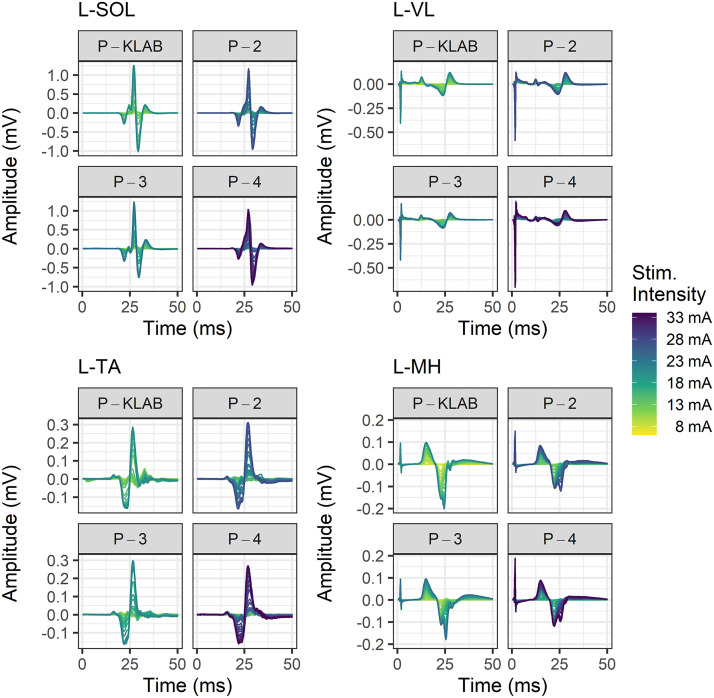

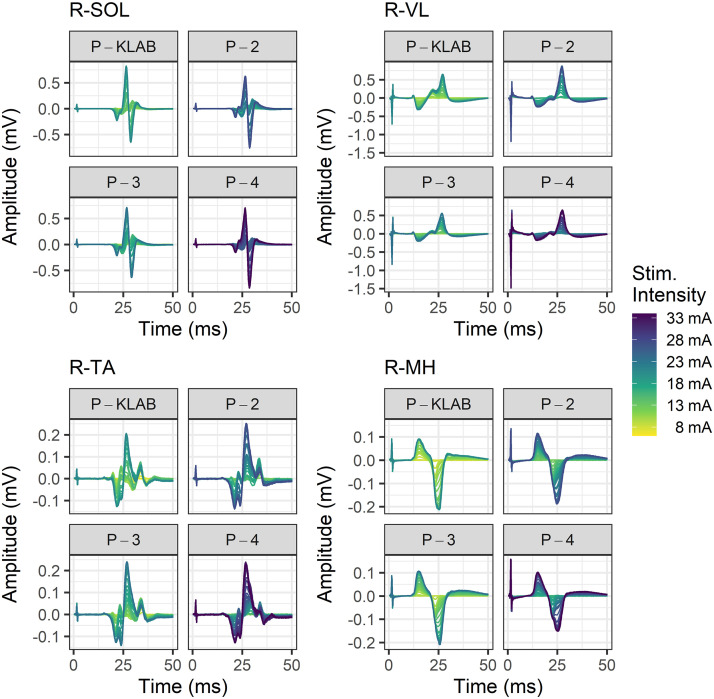

Representative nonrectified TEP waveforms recorded from the left (Fig. 4) and right (Fig. 5) SOL, TA, VL, and MH muscles at different stimulation intensities to build the recruitment input-output curve are shown separately for P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4. In both Figs. 4 and 5, the amplitude of TEPs is shown as a function of the stimulation intensity that is color coded, with yellow and purple representing low and high stimulation intensities, respectively. It is apparent that to elicit TEPs in left and right knee or ankle muscles of similar size more stimulation intensity is needed for P-2 and P-4 compared with P-KLAB or P-3. A one-way, mixed-effects model analysis verified a significant main effect of protocol on the maximum stimulation intensity needed to reach a plateau (F3,29 = 36.96, P < 0.0001). Tukey’s multiple comparisons showed that the maximum stimulation intensity was significant different between P-KLAB and P-2 (P = 0.0005, d = −0.837), between P-KLAB and P-4 (P < 0.0001, d = −1.58), between P-2 and P-3 (P = 0.0005, d = 0.825), between P-2 and P-4 (P = 0.0004, d = -0.826), and between P-3 and P-4 (P < 0.0001, d = −1.56), supporting higher maximum stimulation intensities in P-2 and P-4 (27.9 ± 1.6 mA and 32.7 ± 1.9 mA maximum stimulus intensity, respectively) across muscles compared with P-KLAB or P-3 (23.4 ± 1.6 mA and 23.7 ± 1.6 mA maximum stimulus intensity, respectively).

Figure 4.

Color-coded stimulation intensities and associated transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs). TEPs from a representative subject recorded at different stimulation intensities to construct the recruitment input-output curve for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). TEPs are shown for the left (L) soleus (SOL), vastus lateralis (VL), tibialis anterior (TA), and medial hamstring (MH) muscles. The stimulation intensity is color coded, with yellow and purple corresponding to low and high stimulation intensities, respectively.

Figure 5.

Color-coded stimulation intensities and associated transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs). TEPs from a representative participant recorded at different stimulation intensities to construct the recruitment input-output curve for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). TEPs are shown for the right (R) soleus (SOL), vastus lateralis (VL), tibialis anterior (TA), and medial hamstring (MH) muscles. The stimulation intensity is color coded, with yellow and purple corresponding to low and high stimulation intensities, respectively.

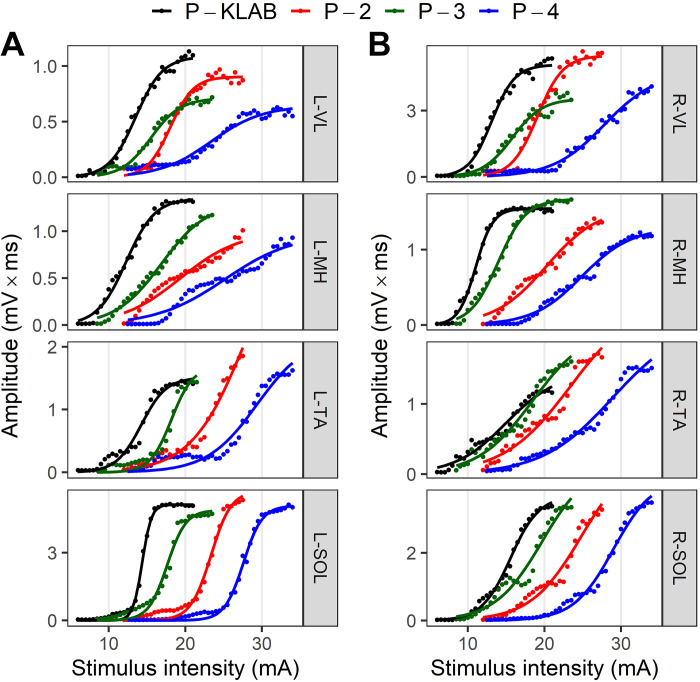

The amplitude of TEPs as area under the rectified curve recorded from left and right SOL, TA, VL, and MH muscles plotted against the stimulation intensity (mA) from a representative subject (subject 7) for all four protocols is indicated in Fig. 6. Regardless of the muscle from which TEPs are recorded, P-KLAB requires less current at TEP threshold and evokes maximal TEPs, whereas a clear shift to the right is evident when TEPs are evoked with P-4. The S shape of the recruitment curve is maintained largely for the ankle and knee extensor muscles but not for the ankle TA flexor muscle or VL and MH with P-4. These results support increased responsiveness of motoneurons after transspinal stimulation with P-KLAB.

Figure 6.

Single-subject transspinal evoked potential (TEP) recruitment input-output curves for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Recruitment input-output curves of TEPs recorded from the left (L; A) and right (R; B) leg muscles for P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4. TEP amplitude is plotted against the stimulation intensities along with the sigmoid function fitted to the data. MH, medial hamstring; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis.

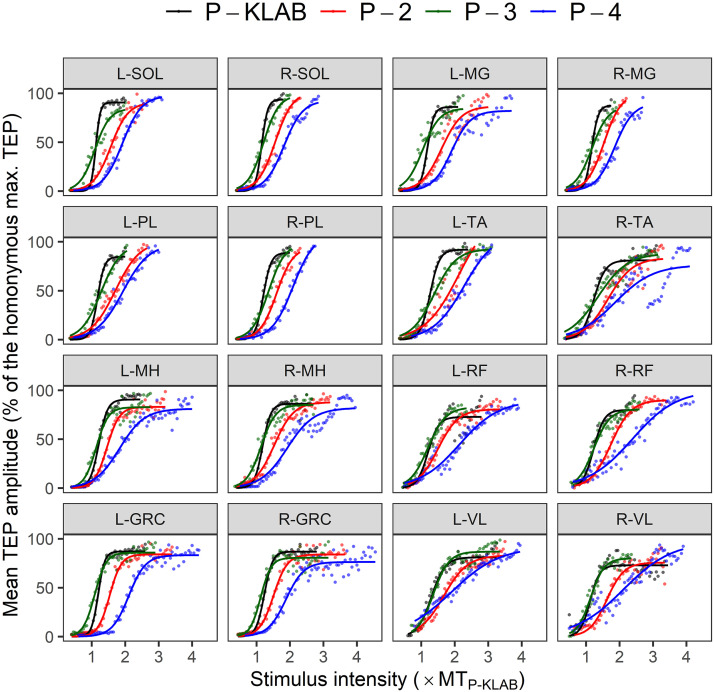

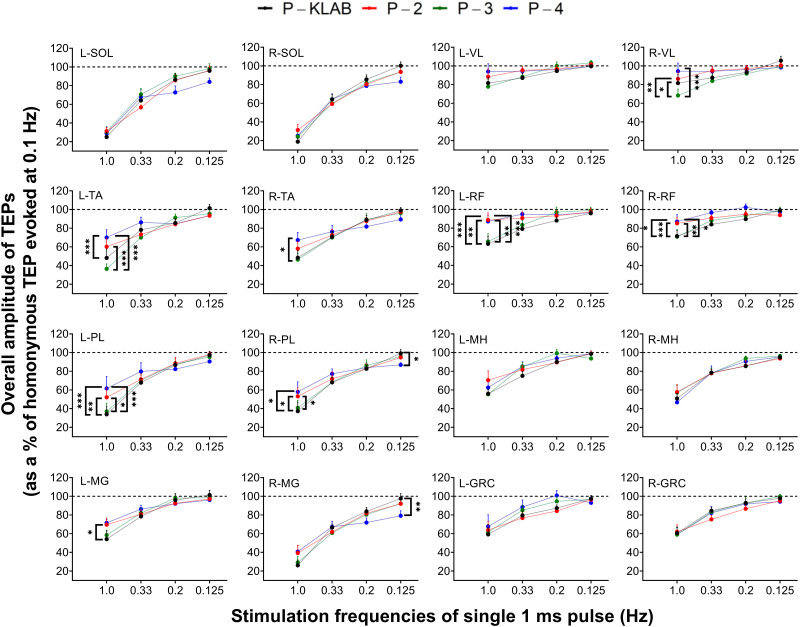

The TEP recruitment curves assembled from all muscles and protocols for all participants are indicated in Fig. 7. TEP amplitudes from all participants are shown as values normalized to the maximal homonymous TEP amplitude and are plotted against the stimulation intensity normalized to the homonymous predicted TEPth intensity of P-KLAB established via the sigmoid fit. It is apparent that the TEP recruitment curves from all ankle and knee muscles are shifted to the right for P-4, supporting that more current is needed to depolarize motoneurons and reach maximal contractions as depicted by the maximal TEP amplitudes.

Figure 7.

Transspinal evoked potential (TEP) recruitment input-output curves. The amplitude of each TEP for each subject was normalized to the homonymous maximal TEP amplitude, plotted against the stimulation intensity normalized to the homonymous predicted right soleus TEP threshold intensity (TEPth) from the KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB) and grouped separately for each muscle and protocol based on multiples (MTs) of TEPth. The sigmoid function fitted to the data is shown. Mean R2 average values across subjects and protocols were for P-KLAB = 0.981 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.975–0.986], protocol 2 (P-2) = 0.980 (95% CI, 0.972–0.985), protocol 3 (P-3) = 0.981 (95% CI, 0.974–0.986), and protocol 4 (P-4) = 0.979 (95% CI, 0.969–0.985). GRC, gracilis; L, left; MG, medial gastrocnemius, MH, medial hamstring; PL, peroneus longus; R, right; RF, rectus femoris; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis.

Two-way mixed-effects analysis was conducted for each muscle separately to establish the effects of protocol and stimulation intensity on TEP recruitment curve. Table 1 shows the results of the tests of fixed effects (F ratio, degrees of freedom, P value) for each TEP recruitment curve assembled for each muscle. As expected, a significant main effect of stimulation intensity on TEP recruitment curve was found in all muscles (P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a statistically significant main effect of protocol in all muscles. The results of Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests of the effects of protocol at stimulation intensities ranging from 1.0 × to 2.5 × TEPth of P-KLAB are presented in Fig. 8. Pairwise significant differences (P < 0.05) of TEP amplitudes between protocols at each normalized stimulation intensity are indicated with colored dots. The color of the dot indicates for which protocol the TEP amplitude is higher. For example, the green dots for the left SOL, same color for P-3, indicate that TEP values of P-3 are higher than those of P-4. Similarly, the red dots for the left SOL, same color for P-2, indicate that TEP values for P-2 are higher than those of P-4. TEP amplitudes for the recruitment curves for P-4 are not higher than for any other protocol, while P-KLAB and P-3 predominate.

Table 1.

Results of analysis of variance of transspinal evoked potential recruitment curve for each muscle

| F Ratio | df | P Value | F Ratio | df | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-SOL | L-MH | ||||||

| Protocol | 61.7 | 3, 30 | <0.001 | Protocol | 14.9 | 3, 30 | <0.001 |

| Intensity | 21.4 | 31, 310 | <0.001 | Intensity | 96.0 | 38, 380 | <0.001 |

| Protocol × intensity | 4.48 | 93, 303 | <0.001 | Protocol × intensity | 3.78 | 114, 248 | <0.001 |

| R-SOL | R-MH | ||||||

| Protocol | 23.7 | 3, 30 | <0.001 | Protocol | 22.0 | 3, 30 | <0.001 |

| Intensity | 85.4 | 26, 260 | <0.001 | Intensity | 131 | 39, 390 | <0.001 |

| Protocol × intensity | 4.51 | 78, 328 | <0.001 | Protocol × intensity | 6.35 | 117, 241 | <0.001 |

| L-MG | L-RF | ||||||

| Protocol | 14.4 | 3, 18 | <0.001 | Protocol | 13.9 | 3, 27 | <0.001 |

| Intensity | 52.8 | 30, 180 | <0.001 | Intensity | 36.4 | 31, 279 | <0.001 |

| Protocol × intensity | 4.29 | 90, 123 | <0.001 | Protocol × intensity | 2.17 | 93, 236 | <0.001 |

| R-MG | R-RF | ||||||

| Protocol | 15.2 | 3, 30 | <0.001 | Protocol | 9.76 | 3, 21 | <0.001 |

| Intensity | 76.2 | 22, 220 | <0.001 | Intensity | 36.1 | 36, 252 | <0.001 |

| Protocol × intensity | 5.17 | 66, 295 | <0.001 | Protocol × intensity | 2.60 | 108, 245 | <0.001 |

| L-PL | L-GRC | ||||||

| Protocol | 17.6 | 3, 30 | <0.001 | Protocol | 19.6 | 3, 27 | <0.001 |

| Intensity | 65.1 | 31, 310 | <0.001 | Intensity | 107 | 33, 297 | <0.001 |

| Protocol × intensity | 2.66 | 93, 275 | <0.001 | Protocol × intensity | 10.7 | 99, 211 | <0.001 |

| R-PL | R-GRC | ||||||

| Protocol | 14.2 | 3, 27 | <0.001 | Protocol | 19.0 | 3, 27 | <0.001 |

| Intensity | 78.0 | 26, 234 | <0.001 | Intensity | 158 | 36, 324 | <0.001 |

| Protocol × intensity | 3.92 | 78, 258 | <0.001 | Protocol × intensity | 7.51 | 108, 294 | <0.001 |

| L-TA | L-VL | ||||||

| Protocol | 17.7 | 3, 30 | <0.001 | Protocol | 4.08 | 3, 18 | 0.02 |

| Intensity | 60.9 | 31, 310 | <0.001 | Intensity | 28.7 | 33, 198 | <0.001 |

| Protocol × intensity | 1.53 | 93, 188 | 0.007 | Protocol × intensity | 1.91 | 99, 195 | <0.001 |

| R-TA | R-VL | ||||||

| Protocol | 11.6 | 3, 27 | <0.001 | Protocol | 9.50 | 3, 21 | <0.001 |

| Intensity | 48.5 | 44, 396 | <0.001 | Intensity | 41.9 | 29, 203 | <0.001 |

| Protocol × intensity | 1.34 | 132, 129 | 0.05 | Protocol × intensity | 3.26 | 87, 118 | <0.001 |

Two-way repeated-measures mixed-effects model analysis with participants as random factor was conducted in each muscle to examine the effect of protocol and stimulation intensity factors (fixed) on transspinal evoked potential (TEP) recruitment curve. The analysis of variance table of the fixed effects shows the F ratio, degrees of freedom (df), and P value separately for each muscle. GRC, gracilis; L, left; MG, medial gastrocnemius; MH, medial hamstring; PL, peroneus longus; R, right; RF, rectus femoris; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis. Significant differences for P < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Comparisons of transspinal evoked potential (TEP) recruitment input-output curves between KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Statistically significant differences of TEPs recorded at 1 × to 2.5 × the TEP threshold (MT) of P-KLAB based on Tukey’s post hoc comparisons between protocols (P < 0.05). The dots indicate statistically significant differences between protocols. The color of the dot indicates at which protocol the TEP amplitude is higher. For example, the green dots for the left soleus (SOL), same color representing P-3, indicate that TEP values of P-3 are higher than those of P-4. Similarly, the red dots for the left SOL, same color representing P-2, indicate that TEP values for P-2 are higher than those of P-4. TEP amplitudes for the recruitment curves for P-4 are not higher than for any other protocol, whereas P-KLAB and P-3 predominate. GRC, gracilis; L, left; MG, medial gastrocnemius, MH, medial hamstring; PL, peroneus longus; R, right; RF, rectus femoris; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis.

Descriptive statistics for the predicted parameters (TEPth, S50, m, slope) from the sigmoid function fitted to each TEP recruitment input-output curves separately for each subject, muscle, and protocol are summarized in Table 2 for the ankle muscles and in Table 3 for the knee muscles from both legs. Two-way, mixed-effects analysis was conducted to establish the effects of protocol and muscle on TEPth (aligned rank transformed), S50, m, and slope. The TEPth was statistically significant different between protocols (F3,439 = 269.9, P < 0.001) and muscles (F15,439 = 1.792, P = 0.03). Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests showed that the TEPth was not significant different between P-KLAB and P-3 but was significantly different between P-KLAB and P-4 (P < 0.001, d = −3.163) and between P-3 and P-4 (P < 0.001, d = −3.043), supporting the shift of the recruitment curves to the right for P-4 compared to P-KLAB and P-3, i.e., higher stimulation intensity thresholds for P-4 (see Fig. 7). In Tables 2 and 3, the values of the stimulation intensity corresponding to the TEPth for all protocols are presented as multiples (MTs) of the P-KLAB threshold. On average, P-4 and P-2 TEPth values were 1.6 and 1.3 times higher than that of the P-KLAB. In contrast, P-3 shared similar TEPth values with P-KLAB (P-3 TEPth is 0.99 MT of P-KLAB).

Table 2.

Transspinal evoked potential recruitment curve sigmoid function parameters for the different protocols for shank muscles

| L-SOL | R-SOL | L-MG | R-MG | L-PL | R-PL | L-TA | R-TA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation intensity at threshold (TEPth)* | ||||||||

| P-KLABa | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 |

| P-2b | 1.33 ± 0.067 | 1.31 ± 0.081 | 1.36 ± 0.048 | 1.24 ± 0.068 | 1.32 ± 0.074 | 1.24 ± 0.091 | 1.44 ± 0.13 | 1.45 ± 0.097 |

| P-3a | 0.99 ± 0.055 | 1.01 ± 0.056 | 0.92 ± 0.070 | 0.99 ± 0.058 | 1.00 ± 0.059 | 1.04 ± 0.051 | 1.07 ± 0.081 | 1.03 ± 0.067 |

| P-4c | 1.65 ± 0.098 | 1.59 ± 0.078 | 1.64 ± 0.046 | 1.63 ± 0.10 | 1.54 ± 0.11 | 1.62 ± 0.12 | 1.80 ± 0.11 | 1.30 ± 0.20 |

| Stimulus required to elicit TEP equivalent to 50% of TEPmax (S50) | ||||||||

| P-KLAB | 1.14 ± 0.016a | 1.13 ± 0.011a | 1.25 ± 0.034a | 1.20 ± 0.022a | 1.21 ± 0.028a | 1.20 ± 0.025a | 1.29 ± 0.028a | 1.39 ± 0.073a |

| P-2 | 1.55 ± 0.083b | 1.60 ± 0.13b | 2.00 ± 0.15b | 1.54 ± 0.069b | 1.68 ± 0.12b | 1.62 ± 0.066b | 1.80 ± 0.16b | 2.06 ± 0.25b |

| P-3 | 1.16 ± 0.084a | 1.17 ± 0.077a | 1.18 ± 0.12a | 1.16 ± 0.074a | 1.19 ± 0.079a | 1.27 ± 0.072a | 1.43 ± 0.12a | 1.46 ± 0.16a |

| P-4 | 1.89 ± 0.099b | 1.90 ± 0.11c | 2.04 ± 0.11b | 1.83 ± 0.10b | 2.02 ± 0.15b | 1.97 ± 0.12b | 2.32 ± 0.18c | 2.36 ± 0.31b |

| m parameter of function | ||||||||

| P-KLAB | 16.5 ± 1.74a | 14.2 ± 1.49a | 9.27 ± 1.60a | 10.1 ± 0.85a,b | 11.0 ± 1.39a | 11.9 ± 1.69a | 7.37 ± 0.68a | 6.26 ± 1.23a,b |

| P-2 | 10.8 ± 1.36b | 10.0 ± 1.62b | 3.50 ± 0.58b | 6.95 ± 0.82c | 9.00 ± 1.89a | 6.32 ± 0.79b | 5.46 ± 0.59a | 4.84 ± 1.10a |

| P-3 | 15.1 ± 1.94a | 17.6 ± 1.64a | 5.94 ± 0.41a,b | 12.9 ± 1.51a | 10.8 ± 1.62a | 8.78 ± 1.18a,b | 6.96 ± 1.13a | 8.30 ± 1.64b |

| P-4 | 8.87 ± 0.88b | 9.07 ± 1.35b | 3.84 ± 0.31b | 7.82 ± 1.36b,c | 7.67 ± 1.82a | 6.16 ± 0.61b | 4.80 ± 0.83a | 2.88 ± 0.63a |

| Slope | ||||||||

| P-KLAB | 0.14 ± 0.016a | 0.13 ± 0.011a | 0.25 ± 0.034a | 0.20 ± 0.022a | 0.21 ± 0.028a | 0.20 ± 0.025a | 0.29 ± 0.028a | 0.39 ± 0.073a |

| P-2 | 0.22 ± 0.032a | 0.18 ± 0.027a | 0.57 ± 0.10b | 0.30 ± 0.041a | 0.24 ± 0.045a | 0.28 ± 0.023a | 0.32 ± 0.034a | 0.48 ± 0.12a,b |

| P-3 | 0.14 ± 0.014a | 0.12 ± 0.011a | 0.26 ± 0.057a | 0.15 ± 0.020a | 0.22 ± 0.045a | 0.28 ± 0.044a | 0.36 ± 0.072a | 0.43 ± 0.12a |

| P-4 | 0.20 ± 0.012a | 0.19 ± 0.020a | 0.47 ± 0.063b | 0.26 ± 0.037a | 0.28 ± 0.066a | 0.31 ± 0.023a | 0.42 ± 0.058a | 0.72 ± 0.16b |

Averaged values (mean ± SE) of the predicted parameters from the sigmoid function fitted to the data for each transspinal evoked potential (TEP) recruitment curve. The values of the stimulation intensity corresponding to the TEP threshold (TEPth) for all protocols are presented as multiples (MTs) of the KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB) TEP threshold. Since the raw stimulation intensity was normalized to the homonymous predicted TEPth observed for the P-KLAB for each TEP separately, the TEPth values for the P-KLAB are 1 MT. Lower case letter displays of Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests report significant pairwise comparisons. Based on Tukey’s multiple comparison tests of the simple effects of protocol at the levels of muscle factor, averaged values with no letter in common are significantly different at 5% level of significance. When the same superscripted letter does not appear at each row, then there is a significant difference between the protocols. For example, m parameter of function for L-SOL TEP is significantly different between P-KLAB and protocol 2 (P-2) and between P-KLAB and protocol 4 (P-4) because they do not have the same letter. Similarly, the m for P-KLAB is not different between P-KLAB and protocol 3 (P-3) because they share the same letter. *For the TEPth variable a significant interaction between muscle and protocol was not found. L, left; MG, medial gastrocnemius; PL, peroneus longus; R, right; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior.

Table 3.

Transspinal evoked potential recruitment curve sigmoid function parameters for the different protocols for thigh muscles

| L-MH | R-MH | L-RF | R-RF | L-GRC | R-GRC | L-VL | R-VL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation intensity at threshold (TEPth)* | ||||||||

| P-KLABa | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 |

| P-2b | 1.26 ± 0.04 | 1.36 ± 0.03 | 1.27 ± 0.10 | 1.34 ± 0.11 | 1.26 ± 0.03 | 1.27 ± 0.06 | 1.21 ± 0.13 | 1.37 ± 0.08 |

| P-3a | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.97 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 1.11 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.07 |

| P-4c | 1.57 ± 0.10 | 1.75 ± 0.10 | 1.52 ± 0.15 | 1.55 ± 0.36 | 1.73 ± 0.08 | 1.57 ± 0.09 | 1.79 ± 0.08 | 1.41 ± 0.20 |

| Stimulus required to elicit TEP equivalent to 50% of TEPmax (S50) | ||||||||

| P-KLAB | 1.18 ± 0.013a | 1.27 ± 0.034a | 1.48 ± 0.13a | 1.24 ± 0.04a | 1.19 ± 0.016a | 1.25 ± 0.028a | 1.57 ± 0.17a,b | 1.33 ± 0.07a |

| P-2 | 1.53 ± 0.061b | 1.72 ± 0.092b | 1.54 ± 0.08a | 1.94 ± 0.05b | 1.61 ± 0.072b | 1.59 ± 0.059b | 1.95 ± 0.25a | 1.95 ± 0.19b |

| P-3 | 1.15 ± 0.070a | 1.24 ± 0.084a | 1.32 ± 0.95a | 1.23 ± 0.07a | 1.13 ± 0.056a | 1.27 ± 0.083a | 1.33 ± 0.06b | 1.16 ± 0.03a |

| P-4 | 2.18 ± 0.18c | 1.81 ± 0.085b | 2.30 ± 0.12b | 2.13 ± 0.29b | 2.15 ± 0.039c | 2.01 ± 0.086c | 1.91 ± 0.23a | 2.00 ± 0.23b |

| m parameter of function | ||||||||

| P-KLAB | 10.8 ± 0.66a | 8.70 ± 1.02a,b | 7.56 ± 1.89a | 7.59 ± 1.39a | 10.7 ± 1.16a | 8.30 ± 0.95a | 4.43 ± 1.09a | 7.85 ± 1.95a |

| P-2 | 7.52 ± 0.94a,b | 5.98 ± 0.77a | 7.41 ± 1.42a | 4.31 ± 0.76a,b | 6.23 ± 0.48b,c | 5.83 ± 0.62a,b | 6.81 ± 2.45a | 5.94 ± 1.80a,b |

| P-3 | 9.29 ± 1.32a | 9.39 ± 1.21b | 9.26 ± 2.07a | 9.81 ± 2.52a | 10.5 ± 1.51a,b | 8.32 ± 1.25a,b | 8.09 ± 1.97a | 12.1 ± 2.56a |

| P-4 | 5.13 ± 1.25b | 5.87 ± 0.80a,b | 4.28 ± 0.95b | 3.88 ± 1.31b | 5.29 ± 0.63c | 4.53 ± 0.45b | 4.92 ± 1.58a | 3.94 ± 0.63b |

| Slope | ||||||||

| P-KLAB | 0.18 ± 0.013a | 0.27 ± 0.034a | 0.48 ± 0.13a,b | 0.24 ± 0.047a | 0.19 ± 0.016a | 0.25 ± 0.02a | 0.57 ± 0.17a | 0.33 ± 0.07a,b |

| P-2 | 0.27 ± 0.028a | 0.40 ± 0.056a | 0.32 ± 0.06a | 0.52 ± 0.11b,c | 0.31 ± 0.019a | 0.39 ± 0.04a,b | 0.45 ± 0.17a | 0.57 ± 0.19a,c |

| P-3 | 0.17 ± 0.022a | 0.25 ± 0.032a | 0.39 ± 0.11a | 0.26 ± 0.061a,b | 0.17 ± 0.016a | 0.27 ± 0.04a | 0.28 ± 0.05a | 0.20 ± 0.05b |

| P-4 | 0.32 ± 0.055a | 0.35 ± 0.048a | 0.64 ± 0.14b | 0.58 ± 0.17c | 0.42 ± 0.054a | 0.48 ± 0.05b | 0.40 ± 0.10a | 0.59 ± 0.09c |

Averaged values (mean ± SE) of the predicted parameters from the sigmoid function fitted to the data for each transspinal evoked potential (TEP) recruitment curve. The values of the stimulation intensity corresponding to the TEP threshold (TEPth) for all configurations are presented as multiples (MTs) of the TEP threshold of the KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB). Since the raw stimulation intensity was normalized to the homonymous predicted TEPth observed for the P-KLAB for each TEP separately, the TEPth values for the P-KLAB are 1 MT. Lower case letter displays of Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests report significant pairwise comparisons. Based on Tukey’s multiple comparison tests of the simple effects of protocol at the levels of muscle factor, averaged values with no letter in common are significantly different at 5% level of significance. When the same subscripted letter does not appear at each row, then there is a significant difference between the protocols. For example, m parameter of function for L-MH TEP is significantly different between P-KLAB and protocol 4 (P-4) because they do not have the same letter. Similarly, m parameter of function for L-MH TEP is not different between P-KLAB and protocol 3 (P-3) because they share the same letter. *For the TEPth variable a significant interaction between muscle and protocol was not found. GRC, gracilis; L, left; MH, medial hamstring; P-2, protocol 2; R, right; RF, rectus femoris; VL, vastus lateralis.

Similarly, the stimulation intensity required to elicit a TEP equivalent to 50% of the TEPmax (S50) was lower in P-KLAB and P-3 (1.27 MT of P-KLAB and 1.24 MT of P-KLAB, respectively) compared with P-2 and P-4 (1.73 MT of P-KLAB and 2.05 MT of P-KLAB, respectively) (Tables 2 and 3). S50 was statistically significant different across muscles (F15,150 = 3.244, P < 0.001) and protocols (F3,30 = 34.09, P < 0.001), while a significant interaction between muscle and protocol was present (F45,269 = 1.66, P = 0.008). Tukey’s multiple comparisons test showed that the S50 was not significantly different between P-KLAB and P-3, but it was significantly different between P-KLAB and P-4 (except for the left VL muscle, P = 0.12), between P-3 and P-4, between P-KLAB and P-2 (except for left VL and left RF, P = 0.19 and P = 0.59, respectively), and between P-3 and P-2 (except for the left RF muscle, P = 0.09), supporting a shift of the recruitment curves to the right and/or decreased steepness of the recruitment curves for P-4 and P-2 compared with P-KLAB and P-3.

Mean values of the m parameter and TEP slope are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The m parameter was significantly different between protocols (F3,30 = 12.58, P < 0.001) and muscles (F15,150 = 6.785, P < 0.001), while a significant interaction between protocol and muscle was present (F45,280 = 1.993, P < 0.001). The m function of the slope was not significantly different between P-KLAB and P-3 or between P-2 and P-4. The slope of the TEP recruitment curves was significantly different between protocols (F3,30 = 4.651, P = 0.009) and muscles (F15,150 = 7.274, P < 0.001), while a significant interaction between protocol and muscle was present (F45,250 = 1.913, P < 0.001). The slope of the TEP recruitment curves was not significantly different between P-KLAB and P-3 or between P-2 and P-4 (except for the left RF muscle, P = 0.01). In contrast, the slope was significantly different between P-3 and P-4 for the right VL, right TA, right/left RF, right GRC, and left MG TEPs (P < 0.05 for all). Additional significant differences were found between P-KLAB and P-4 for the right VL, right TA, right RF, right GRC, and left MG TEPs (P < 0.05 for all). The slope was significantly different between P-KLAB and P-2 for the right RF and left MG and between P-2 and P-3 for the left MG and the right VL TEP recruitment curves (P < 0.05). The altered slope of the TEP recruitment input-output curves between P-KLAB or P-3 and P-2 or P-4 suggests that P-KLAB–P-3 and P-2–P-4 affect the gain of the system differently. In P-2 or P-4, the steepness of the input-output relationship was increased up to 1.39 and 1.64 times the P-KLAB mean value and up to 1.52 and 1.80 times the P-3 mean value, respectively. The results of the protocol effects for each muscle and all predicted parameters from the sigmoid fit (TEPth, S50, m, slope) are presented in Tables 2 and 3, where a significant difference is noted with lower case letter displays. Average values with no common letter are significantly different based on results of Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (α = 0.05).

Depression of TEPs following Single-Pulse Transspinal Stimulation at Different Frequencies for P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4

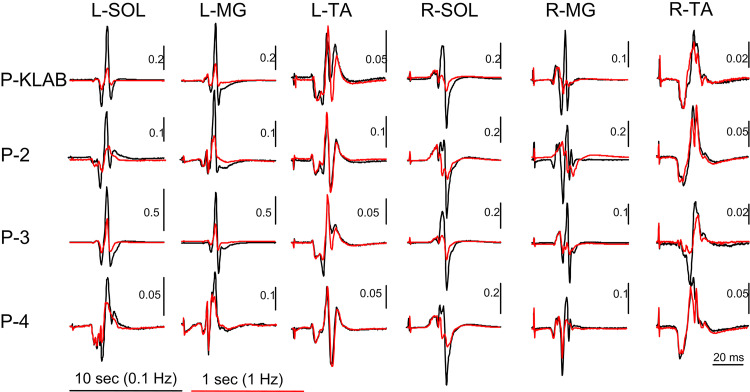

Representative nonrectified waveform averages (n = 12) of TEPs recorded from the left and right SOL, MG, and TA muscles from one subject (subject 11) are indicated in Fig. 9. For all cases, TEPs evoked by single monophasic 1-ms-duration stimulation pulses delivered at 1.0 Hz are shown superimposed to TEPs evoked at 0.1 Hz. It is apparent that 1) TEPs in the left and right SOL and MG muscles are significantly depressed when evoked at 1.0 Hz compared with 0.1 Hz, 2) depression at 1.0 Hz is absent in the left TA TEPs, whereas some depression is evident in the right TA TEP with P-3, and 3) TEPs evoked with P-4 in this subject are smaller in amplitude compared with TEPs evoked with P-KLAB or P-3 (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Single transspinal stimuli induced transspinal evoked potential (TEP) depression in ankle muscles for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Representative examples of nonrectified waveform averages (n = 12) of TEPs recorded from the left (L) and right (R) soleus (SOL), medial gastrocnemius (MG), and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles upon thoracolumbar stimulation at frequencies of 0.1 and 1.0 Hz for all 4 protocols tested in this study.

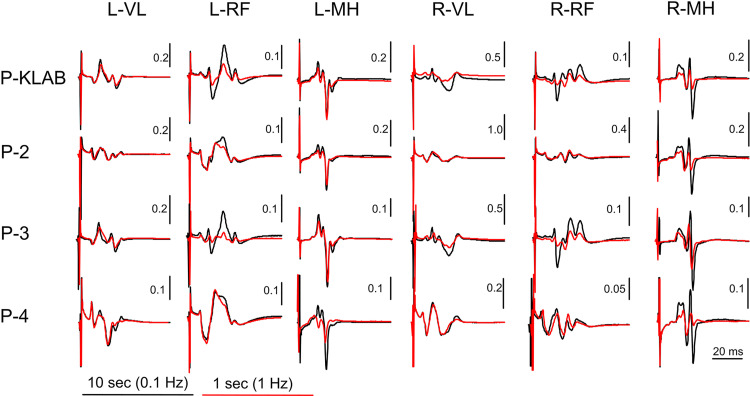

For the same subject, the nonrectified waveform averages (n = 12) of TEPs recorded from the left and right VL, RF, and MH muscles upon single transspinal stimuli at 1.0 Hz superimposed to the TEPs evoked at 0.1 Hz for all four protocols are indicated in Fig. 10. It is apparent that knee TEPs have a shorter latency compared with ankle TEPs, consistent with the shorter distance between the stimulation and recording sites (56, 59). More importantly, TEP depression following single transspinal stimulation at different frequencies manifests in a muscle-dependent manner, being absent in the left and right VL but present in the left and right MH for all four protocols.

Figure 10.

Single transspinal stimuli induced transspinal evoked potential (TEP) depression in thigh muscles for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Representative examples of nonrectified waveform averages (n = 12) of TEPs recorded from the left (L) and right (R) vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris (RF), and medial hamstrings (MH) muscles upon thoracolumbar stimulation at frequencies of 0.1 and 1.0 Hz for all 4 protocols tested in this study.

The overall amplitude of TEPs, from all subjects, evoked at stimulation frequencies of 1.0, 0.33, 0.2, and 0.125 Hz as a percentage of the homonymous TEP evoked at 0.1 Hz is shown in Fig. 11 for each protocol. Two-way, mixed-effects analysis performed separately for each muscle and protocol showed that the strength of TEP depression was not significantly different between protocols for all muscles, while an interaction between stimulation frequency and protocol was present in the left/right TA (F12,109 = 5.480, P < 0.0001 and F12,110 = 3.199, P = 0.0006, respectively), left/right PL (F12,110 = 3.348, P = 0.0004 and F12,109 = 3.308, P = 0.0004, respectively), left/right MG (F12,109 = 2.234, P = 0.0146 and F12,109 = 2.693, P = 0.0033, respectively), left/right RF (F12,108 = 3.896, P < 0.0001 and F12,110 = 2.789, P = 0.0023, respectively), and right VL (F12,109 = 2.454, P = 0.0072). Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests showed a significant difference between P-KLAB and P-4 at 1.0 Hz (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Single transspinal stimuli induced transspinal evoked potential (TEP) depression for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Overall mean amplitude of TEPs evoked at different stimulation frequencies for each protocol is shown as a percentage of the homonymous TEP evoked at 0.1 Hz. GRC, gracilis longus; L, left; MG, medialis gastrocnemius; MH, hamstrings; PL, peroneus longus; R, right; RF, rectus femoris; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis. Error bars are SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001: significant differences between protocols on the strength of TEP depression within each stimulation frequency.

At the stimulation frequency of 1.0 Hz, TEPs were grouped by muscle and protocol to investigate further differences between these two factors, because TEP depression at the stimulation frequency of 0.1 Hz was stronger for TEPs recorded from ankle muscles compared with TEPs recorded from knee muscles (Fig. 11). Specifically, the depression was 80% for the SOL, 60% for the TA/MG, and 20% for the GRC/VL TEPs. Indeed, repeated-measures ANOVA showed that the strength of depression at 1.0 Hz varied significantly between muscles (F15,606 = 22.5, P < 0.001) and protocols (F3,606 = 13.74, p < 0.001). Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests showed that the left SOL TEP depression was significantly different from left VL (t = 10.1, P < 0.001), right VL (t = 9.58, P < 0.001), right RF (t = 8.85, P < 0.001), left RF (t = 8.64, P < 0.001), left MG (t = 6.4, P < 0.001), left GRC (t = 5.89, P < 0.001), left MH (t = 5.56, P < 0.001), right GRC (t = 5.46, P < 0.001), right TA (t = 4.48, P < 0.001), left TA (t = 4.24, P < 0.001), and right MH (t = 4.11, P < 0.001) TEPs, supporting a muscle dependence of TEP depression. Additionally, TEP depression at 1.0 Hz was significantly different between P-4 and P-KLAB (t = 4.76, P < 0.001) and between P-2 and P-KLAB (t = 4.37, P < 0.001), suggesting that P-KLAB at 1.0 Hz produces more TEP depression.

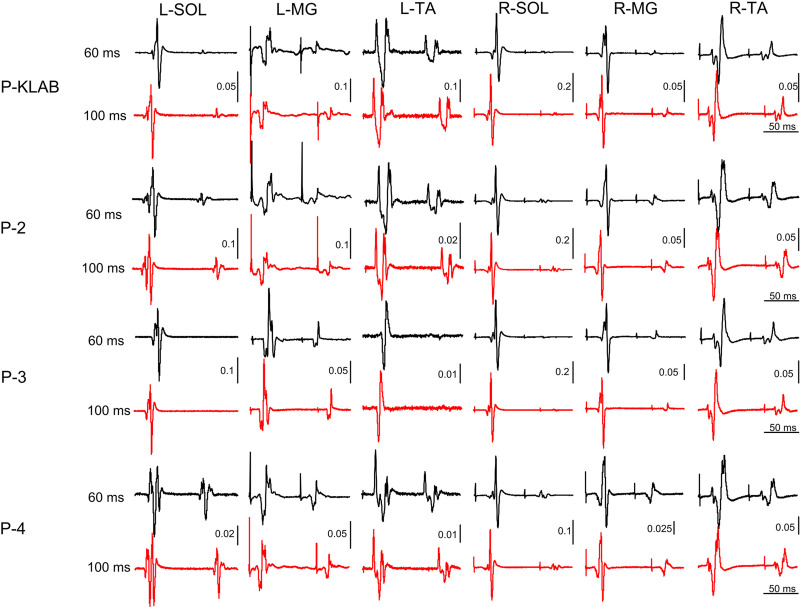

Depression of TEPs following Paired Transspinal Stimulation for P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4

Representative nonrectified waveform averages (n = 12) of TEPs from one participant (participant 9) recorded from the left and right SOL, MG, and TA muscles when paired transspinal stimuli were delivered at the interstimulus intervals of 60 and 100 ms at 0.2 Hz for all four protocols are shown in Fig. 12. It is evident that ankle extensor TEPs are susceptible to a strong depression upon paired transspinal stimulation with the left SOL TEP to be completely occluded with P-KLAB and P-3. The left and right TA TEPs were depressed but not completely occluded. These results suggest a muscle-dependent effect on TEP depression, similar to that described above following transspinal stimulation with single pulses at 1.0 Hz. Additionally, a protocol-dependent effect is present because P-4 appeared to produce less TEP depression compared with the other protocols.

Figure 12.

Paired transspinal stimuli induced transspinal evoked potential (TEP) depression in ankle muscles for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Representative examples of nonrectified waveform averages (n = 12) of TEPs recorded from the left (L) and right (R) soleus (SOL), medial gastrocnemius (MG), and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles upon thoracolumbar paired stimuli at 60 and 100 ms for all 4 protocols tested in this study.

For the same participant (participant 9), the nonrectified waveform averages of TEPs recorded from the left and right VL, RF, and MH muscles upon paired-pulse transspinal stimulation at the interstimulus intervals of 60 and 100 ms for all four protocols are shown in Fig. 13. It is apparent that postactivation TEP depression is absent and replaced by facilitation in left VL TEP in all four protocols, an effect that was present in left/right RF TEP under P-4 and in right VL in P-2 and P-4, especially at the interstimulus interval of 100 ms. Thus, the amount of TEP depression following paired-pulse transspinal stimulation appears in a muscle-dependent manner.

Figure 13.

Paired transspinal stimuli induced transspinal evoked potential (TEP) depression in thigh muscles for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Representative examples of nonrectified waveform averages (n = 12) of transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) recorded from the left (L) and right (R) vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris (RF), and medial hamstrings (MH) muscles upon thoracolumbar paired stimuli at 60 and 100 ms for all 4 protocols tested in this study.

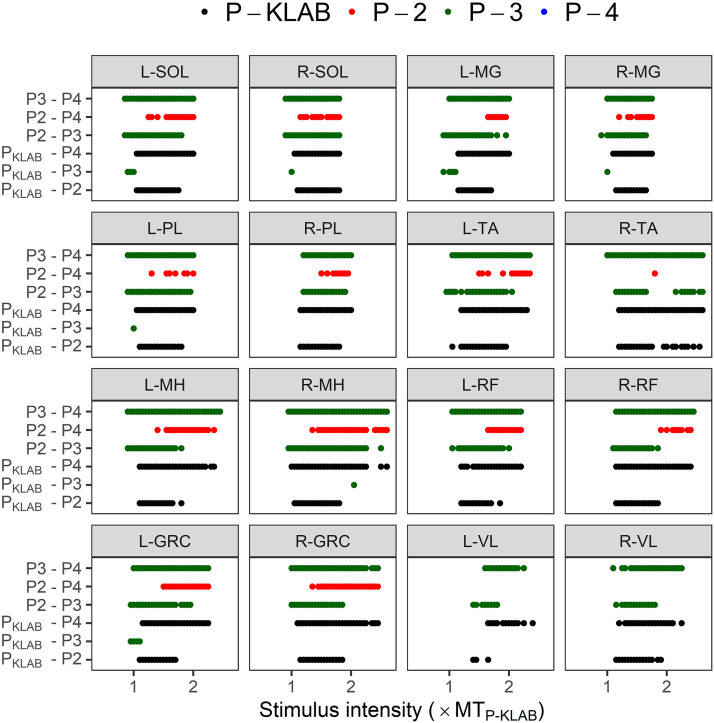

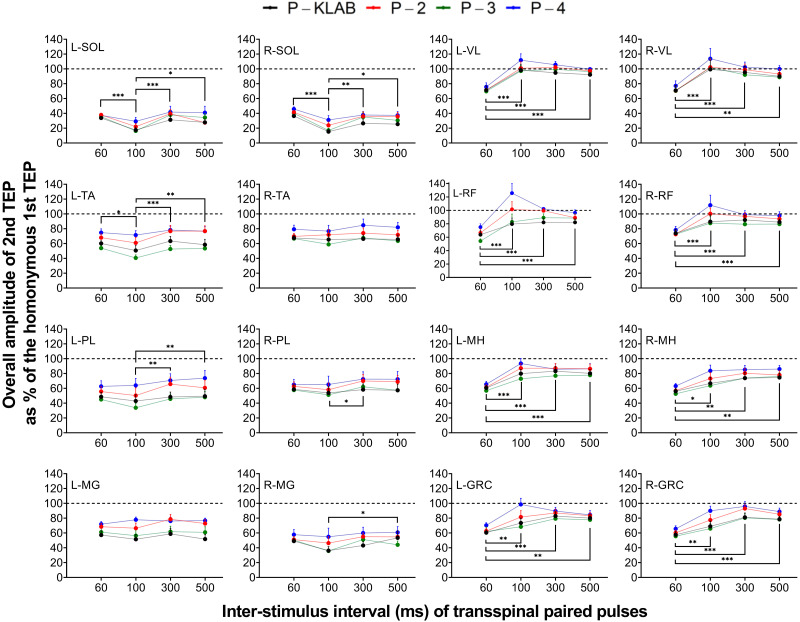

The overall amplitudes of the second TEP following transspinal stimulation with paired pulses at the interstimulus intervals of 60, 100, 300, and 500 ms as a percentage of the homonymous TEP evoked by the first pulse from all subjects and protocols are shown in Fig. 14. Based on two-way mixed-effects analysis, the strength of TEP depression induced by paired transspinal stimuli was significantly different between protocols and interstimulus intervals for the left TA (protocol: F3,30 = 28.05, P < 0.001; ISI: F3,30 = 7.31, P < 0.001), left MH (protocol: F3,30 = 6.541, P = 0.002; ISI: F3,30 = 35.48, P < 0.001), left GRC (protocol: F3,30 = 3.328, P = 0.03; ISI: F3,30 = 10.47, P < 0.001), left RF (protocol: F3,30 = 8.577, P < 0.001; ISI: F3,30 = 14.18, P < 0.001), and left PL (protocol: F3,30 = 9.175, P < 0.001; ISI: F3,30 = 6.017, P = 0.002), whereas for the left MG there were significant differences only across protocols (protocol: F3,30 = 3.654, P = 0.02; ISI: F3,30 = 2.006, P = 0.13). No statistically significant differences as a function of protocol were found in the left SOL TEP (protocol: F3,30 = 1.900, P = 0.15; ISI: F3,30 = 8.408, P < 0.001) and left VL (protocol: F3,30 = 2.547, P = 0.07; ISI: F3,30 = 24.45, P < 0.001). For TEPs recorded from the right leg muscles, the strength of depression was significantly different between protocols and interstimulus intervals for the right SOL (protocol: F3,30 = 4.961, P = 0.006; ISI: F3,30 = 10.96, P < 0.001), right MG (protocol: F3,30 = 3.286, P = 0.03; ISI: F3,30 = 3.745, P = 0.02), right MH (protocol: F3,30 = 5.554, P = 0.004; ISI: F3,30 = 7.837, P < 0.001), and right GRC (protocol: F3,30 = 3.328, P = 0.03; ISI: F3,30 = 10.47, P < 0.001), whereas for the right TA statistically significant differences were found only between protocols (protocol: F3,30 = 4.709, P = 0.008; ISI: F3,30 = 1.111, P = 0.36). No statistically significant differences as a function of protocol were found for the right PL TEP (protocol: F3,30 = 2.781, P = 0.06; ISI: F3,30 = 3.729, P = 0.02), right VL (protocol: F3,30 = 1.426, P = 0.25; ISI: F3,30 = 13.57, P < 0.001), and right RF (protocol: F3,30 = 2.799, P = 0.06; ISI: F3,30 = 20.07, P < 0.001). In general, the strength of depression was different between P-KLAB and P-4 (left TA: P < 0.001, d = −0.928; left RF: P < 0.001, d = −0.864; left PL: P = 0.005, d = −0.783; left MG: P = 0.04, d = −1.21; right SOL: P = 0.007, d = −0.874; right MH: P = 0.01, d = −0.560; right GRC: P = 0.002, d = −0.681; right TA: P = 0.03, d = −0.736) and between P-4 and P-3 (left GRC: P = 0.04, d = 0.718; left RF: P = 0.002, d = 0.733; left PL: P < 0.001, d = 1.02; right MG: P = 0.05, d = 0.58; right MH: P = 0.004, d =0.606; right GRC: P < 0.001, d = 0.758; right TA: P = 0.01, d = 0.813). For the knee muscles, TEPs at 60 ms were statistically significantly different from the other interstimulus intervals (100, 300, and 500 ms) (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

Paired transspinal stimuli induced transspinal evoked potential (TEP) depression for KNIKOU-LAB4Recovery protocol (P-KLAB), protocol 2 (P-2), protocol 3 (P-3), and protocol 4 (P-4). Overall mean amplitude of the 2nd TEP evoked at 60-, 100-, 300-, and 500-ms interstimulus intervals for each protocol is shown as a percentage of the homonymous 1st TEP upon paired thoracolumbar stimuli for all 4 protocols. GRC, gracilis longus; L, left; MG. medialis gastrocnemius; MH, medial hamstrings; PL, peroneus longus; R, right; RF, rectus femoris; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis. Error bars are SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001: significant differences between interstimulus intervals on the strength of TEP depression.

To assess whether TEP depression following transspinal stimulation with paired pulses was muscle dependent between protocols, as was the case for TEP depression following transspinal stimulation at 0.1 Hz, a two-way mixed-effects model with protocol and muscle as fixed factors was performed for each interstimulus interval separately. At the interstimulus interval of 60 ms, a significant main effect of muscle (F15,150 = 8.194, P < 0.001) and protocol (F3,30 = 9.353, P < 0.001) was found, while an interaction between muscle protocol was also present (F45,413 = 1.637, P = 0.008). Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests showed that TEP depression following transspinal stimulation with paired pulses in ankle extensor muscles like SOL was statistically significantly different from that observed in thigh muscles [left SOL vs. left and right RF (d = −2.07 and d = −2.99, respectively), left and right GRC (d = −2.37 and d = −2.10, respectively), left and right VL (d = −2.80 and d = −2.34, respectively), and left and right TA TEP (d = −2.24 and d = −2.84, respectively); right SOL vs. left and right RF (d = −1.71 and d = −2.60, respectively), left and right GRC (d = −1.94 and d = −1.66, respectively), left and right VL (d = −2.41 and d = −2.02, respectively), and left and right TA TEP (d = −1.84 and d = −2.42, respectively); all P < 0.01], and differences between synergistic muscles like left SOL and left MG were also present (P = 0.01, d = −2.07). Furthermore, TEP depression was statistically significantly different between P-KLAB and P-4 (P = 0.001, d = −0.491) and between P-3 and P-4 (P < 0.001, d = −0.57). Similar results were found for the interstimulus interval of 100 ms (muscle: F15,150 = 31.84, P < 0.001; protocol: F3,30 = 3.969, P = 0.02; muscle × protocol: F45,397 = 0.9498, P = 0.58), 300 ms (muscle: F15,150 = 23.06, P < 0.001; protocol: F3,30 = 10.12, P < 0.001; muscle × protocol: F45,416 = 1.298, P = 0.10), and 500 ms (muscle: F15,150 = 22.93, P < 0.001; protocol: F3,30 = 8.020, P < 0.001; muscle × protocol: F45,417 = 1.654, P = 0.007). Collectively, these results support a muscle- and protocol-dependent effect on the strength of TEP depression by transspinal stimulation with paired pulses. In summary, P-4 produced the weakest depression in all muscles, TEPs from knee muscles had the weakest depression compared with triceps surae muscle at 60 ms, and depression was replaced by facilitation in left and right VL and RF TEPs at the interstimulus interval of 100 ms (Fig. 14).

Pain Scale for P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4

The visual analog scale, from 0 to 10, for pain reported by participants at maximal transspinal stimulation intensities was significantly different between protocols (F = 4.96, P = 0.007), with P-4 and P-2 receiving equally higher scores (4.00 ± 0.76 and 3.8 ± 0.61, respectively) compared with P-3 and P-KLAB, which received equally lower scores (3.45 ± 0.8 and 3.54 ± 0.83, respectively).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated in this study significant physiological differences upon variations of the size, position, and number of the cathode electrode for transspinal stimulation. Threshold differences were present with a rightward shift of the TEP recruitment input-output curve recorded from knee and ankle muscles and P-4 needing more current to produce TEPs. These differences coincided at similar onset latencies but with longer duration of TEPs. TEP depression following single and paired transspinal stimuli was pronounced in ankle TEPs, was less prominent or absent in knee TEPs, and was stronger with P-KLAB. TEP depression following paired transspinal stimuli varied between protocols and muscles and was replaced by facilitation at 100 ms in knee but not ankle TEPs. In general, P-KLAB produced more TEP depression. These results support that optimal transspinal stimulation protocols can be based on the strength of spinal inhibition and excitability threshold of TEPs.

Origin of TEPs and Their Susceptibility to Inhibition with P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4

Transspinal stimulation over the thoracolumbar region produces simultaneously bilateral TEPs in knee and ankle muscles. There is a great need to understand the nature of TEPs and what exactly transspinal stimulation activates in the spinal cord. Synaptic actions on motoneurons derived from peristimulus time histograms of single motor units support antidromic activation of group Ia afferents (4), whereas the summation between TA MEPs and TA TEPs on the surface EMG at the negative conditioning-test interval of 8 ms supports transsynaptic activation of alpha motoneurons (21). Furthermore, the summation between the SOL H reflex and SOL TEP at the negative conditioning-test intervals of 13 and 19 ms supports orthodromic excitation of motor axons (22). The prolonged latency of F waves by 2.2 ms following supramaximal stimulation of deep peroneal and tibial nerves at the same time with transspinal stimulation suggests activation of peripheral motor axons near the spinal cord and at the root exit site in the vertebral foramina (60). These activation sites have been confirmed by computer simulation studies (61, 62). Subsequently, we can conclude that TEPs are likely the result of both synaptic and nonsynaptic neuronal events including but not limited to 1) antidromic discharges of muscle afferents, 2) primary afferent depolarization-induced spikes that propagate orthodromic to afferent terminals that subsequently depolarize alpha motoneurons, 3) activation of spinal interneuronal circuits including recurrent and reciprocal Ia inhibition, and 4) orthodromic excitation of motor axons.

TEPs appear to be more complex in nature than we initially thought but may use neuronal mechanisms and spinal circuits/pathways similar to those used by the H reflex and thus possess spinal reflex characteristics. The left/right SOL and right MG TEP exhibited the strongest depression at 1.0 Hz, whereas the least depression was present in the left/right VL and RF TEPs (Figs. 9–11). On the basis of these findings we propose that either transspinal stimulation does not activate similar neuronal pathways for knee and ankle TEPs or this type of depression is not equally distributed in all leg muscles. Furthermore, TEP depression following single transspinal stimuli at 1.0 Hz varied between protocols, with P-KLAB (single rectangular electrode at midline) and P-3 (2 square electrodes at midline) producing more TEP depression than P-2 and P-4, thus supporting more physiological spinal inhibition, consistent with our previous reports (10).

It is well established that the soleus H-reflex amplitude is reduced in response to repetitive tibial nerve stimulation, tendon tap, passive stretch, and TA and SOL muscle contraction (40, 41, 44, 63). In a similar manner, TEPs are depressed during passive muscle stretch and muscle-tendon vibration (64). The soleus H-reflex depression that occurs at the Ia-motoneuron synapse has been attributed to reduced transmitter release from the previously activated Ia afferents and is exerted on the same synapses (40, 41). If we accept that transspinal stimulation produces both orthodromic and antidromic action potentials within the muscle afferents, then it is possible that the TEP depression at 1.0 Hz is partly due to reduced transmitter release at the afferent terminals and decreased strength of sodium spikes that travel antidromic produced by primary afferent depolarization via αGABAA receptors (65, 66). Differences of TEP depression suggest, based on the position, size, and number of the cathode electrode, either that transspinal stimulation can activate different neuronal elements or that the order of activation of different neuronal elements resulting in synaptic and nonsynaptic events differs between protocols.

Posterior tibial nerve stimulation with paired pulses at interstimulus intervals of 30 ms and up to 500 ms produces a significant depression of the second soleus H reflex that can be potentially ascribed to reduced transmitter release at the spinal level, but because transcranial electrical stimulation reduces the reflex depression, long corticospinal loop neuronal pathways may also be involved (10, 67, 68). TEP depression upon paired transspinal stimulation manifested with a different profile compared to that observed upon single transspinal stimulation at 1.0 Hz compared with 0.1 Hz (compare Figs. 11 and 14). TEP depression was stronger with P-KLAB and was significantly reduced with P-4, during which two cathodal electrodes were placed on each paravertebral side (Fig. 14). Furthermore, TEP depression upon paired transspinal stimulation was present at all interstimulus intervals for the ankle TEPs, was maximal for the left and right VL and right RF TEPs at the interstimulus interval of 60 ms, and was either reduced or replaced by facilitation at the interstimulus interval of 100 ms for knee TEPs (Fig. 14), a phenomenon that was pronounced with P-4. The TEP depression at the interstimulus interval of 60 ms may potentially be attributed to reduced transmitter release at the Ia-motoneuron synapse, recurrent inhibition of alpha motoneurons following Renshaw cell activation by motor axon collaterals, hyperpolarization of afferents, and hyperpolarization of motoneurons. The reversal of knee TEP depression to facilitation at the interstimulus interval of 100 ms suggests different types of afferents or different ratios of afferents and motor axons being activated not being susceptible to this type of depression (46, 69). This may be partly due to the transspinal stimulation intensity, which was adjusted to evoke right SOL TEPs equivalent to 20–40% of the homonymous maximal TEP. Because knee TEPs have lower electrical thresholds than ankle TEPs, the stimulation intensity might have been high for the knee TEPs, resulting in recruitment of afferents and/or motor axons not susceptible to presynaptic inhibition. However, we should note that the reversal we observed at 100 ms may be linked to GABA receptors that depolarize the membrane potentials via chloride ions (70) or to facilitatory actions driven by excitatory spinal cord neurons (71).

Threshold, Gain, and Recruitment of Spinal Motoneurons with P-KLAB, P-2, P-3, and P-4

The recruitment input-output curve of the SOL H reflex, M wave, MEP, and TEP is generally characterized by a sigmoid shape (17, 21, 38, 72, 73). Physiological measures derived from the recruitment input-output curves are the shape, threshold, gain, maximal amplitudes, and associated stimulation intensities. The TEP latency remained relatively similar for the same muscle between protocols, with only the left and right TA TEP appearing 2 ms later with P-KLAB compared to P-4. The TEP duration was significantly longer in the right/left GRC and RF TEPs compared to the right MG (Fig. 3B). Because the duration of afterhyperpolarization correlates with motor unit type and twitch contraction time (74), and slow motoneurons have a significantly slower time course of afterhyperpolarization (75), motor unit studies are needed to determine the duration of action potentials of knee and ankle TEPs, eliminating a possible effect of the distance between the surface EMG electrode and the neuromuscular junction and the type of motor units in ankle and knee TEPs. Transspinal stimulation with P-KLAB and P-3 produced TEPs with less intensity, which suggests that these protocols can effectively increase the net output of the spinal cord. This is preferred in cases of impaired motor output of the spinal cord as is the case of upper motoneuron lesions.

The TEP threshold was similar between P-KLAB and P-3 but was different between P-KLAB and P-4 and between P-3 and P-4 (Fig. 7). P-KLAB and P-3 compared to P-2 and P-4 required less intensity to produce TEPs in knee and ankle muscles. This difference is clearly depicted by the rightward shift of the TEP recruitment curves for P-2 and P-4 (Figs. 6 and 7), regardless of the muscle and leg side from which TEPs were recorded. The TEP threshold represents the excitability of all synaptic and nonsynaptic neuronal actions and interactions that occurs inside and away from the spinal cord. A decreased threshold with P-KLAB and P-3 suggests that different cells and axons were activated with P-KLAB and P-3 compared to P-2 and P-4. The fact that P-4 produced the smallest TEP size compared with the remaining protocols (Fig. 8) further supports activation of different neuronal elements.

The threshold differences between protocols were in agreement with the differences in the slope of the TEP recruitment curves, which was higher for P-2 and P-4 compared to P-KLAB and P-3 for the left MG, right TA, left/right RF, right GRC, and right VL muscles (Tables 2 and 3). The slope of the TEP recruitment curves may be viewed as the gain of the spinal cord neuronal circuits after transspinal stimulation. Changes in gain can occur concomitant with changes in threshold and size of action potentials. These changes can partly be attributed to altered number of motoneurons within the subliminal fringe, synaptic inputs to slow versus fast motoneurons, background activity, persistent inward currents of the soma and dendrites of spinal motoneurons, and cholinergic C buttons that increase the gain by reducing the spike afterhyperpolarization (76–80). Specifically, it has been shown that persistent inward currents adjust the input-output properties, increase the amplitude of depolarization, and partly control bistable activity of motoneurons and interneurons (81, 82). The protocols with high gain (P-2 and P-4) may be due to differences in the ratio of inhibitory/excitatory distribution of inputs to motoneurons (83) compressing the recruitment curve, with facilitation of the fast motoneurons (79). Because the nervous system after brain or spinal cord injury responds by increasing the gain of motoneurons and compressing the threshold of consecutively recruited motor neurons (79), we suggest that P-KLAB and P-3 are preferred over P-2 and P-4.

It is possible that the physiological differences we observed may be related to the neuronal elements being activated by the different protocols, especially with one electrode at the midline of the vertebral column (P-KLAB) and one electrode at each paravertebral side (P-4). For example, summation of occlusion of action potentials with P-3 may have been present (30). Modeling studies have shown that posterior column fibers with multiple collaterals have a threshold three times higher than the posterior root fibers, and when activated both anterior and posterior nerve root of small and large diameter fibers are activated (84). However, the order in which different neuronal structures are excited by transspinal stimulation is not known, and future research on this matter is warranted.

Conclusions

This study provided evidence on the strength of TEP depression in response to single and paired transspinal stimuli and excitability threshold and gain of TEP recruitment curves from knee and ankle muscles when the position, size, and number of the cathode stimulating electrode varied in a group of healthy subjects. On the basis of the findings of this study, we suggest that P-KLAB is most optimal compared to P-2, P-3, and P-4 for transspinal stimulation. P-KLAB produces more postactivation depression and thus optimally engages mechanisms or pathways for synaptic and nonsynaptic neuronal activation and interaction, while requiring less current to depolarize motoneurons innervating knee and ankle muscles. The importance of these effects may be apparent in upper motoneuron lesions during which reduced spinal inhibition is one of the major mechanisms underlying hyperreflexia, spasticity, and spasms. Finally, different position or size of electrodes can potentially activate different neuronal elements. More research is warranted on the neuronal structures being activated and the sequence of neuronal events following transspinal stimulation.

Future Research

Transspinal stimulation is a promising neuromodulation method to produce reorganization of cortical and spinal neuronal circuits and thus promote recovery of function in people with spinal cord injury and other neurological disorders. Transspinal stimulation has been delivered at different arrangements as a therapeutic modality including but not limited to single pulses at sub- and suprathreshold levels at rest (18) or during step training (28), paired with transcortical stimulation during step training (26, 27), and at varying frequencies at rest or during stepping (23–25, 85, 86). The SOL TEP shows neuronal characteristics similar to those of the SOL H reflex. However, it is difficult to document whether the SOL TEP has a monosynaptic nature or whether the SOL H reflex and TEP for example activate the same motoneurons (type/number). Furthermore, there is a great need to delineate the order of synaptic and nonsynaptic events, which neuronal circuits are mostly prone to plasticity by short-term and long-term transspinal stimulation, and the duration that neuroplasticity effects are sustained. Answers to these questions could enable the scientific and clinical community to develop targeted rehabilitation strategies via noninvasive transspinal stimulation that are based on neurophysiological evidence.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R01HD100544 and in part by the Spinal Cord Injury Research Board (SCIRB) of the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH), Wadsworth Center under contract number C35594GG awarded to M. Knikou, and the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation (Award No. 725158).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.S.P. and M.K. conceived and designed research; A.S., T.S.P., and M.K. performed experiments; A.S. and M.K. analyzed data; M.K. interpreted results of experiments; A.S. and M.K. prepared figures; A.S. and M.K. drafted manuscript; A.S. and M.K. edited and revised manuscript; A.S., T.S.P., and M.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dimitrijevic MR, Gerasimenko Y, Pinter MM. Evidence for a spinal central pattern generator in humans. Ann NY Acad Sci 860: 360–376, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harkema S, Gerasimenko Y, Hodes J, Burdick J, Angeli C, Chen Y, Ferreira C, Willhite A, Rejc E, Grossman RG, Edgerton VR. Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: a case study. Lancet 377: 1938–1947, 2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60547-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holinski BJ, Mazurek KA, Everaert DG, Toossi A, Lucas-Osma AM, Troyk P, Etienne-Cummings R, Stein RB, Mushahwar VK. Intraspinal microstimulation produces over-ground walking in anesthetized cats. J Neural Eng 13: 056016, 2016. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/13/5/056016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hunter JP, Ashby P. Segmental effects of epidural spinal cord stimulation in humans. J Physiol 474: 407–419, 1994. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jilge B, Minassian K, Rattay F, Pinter MM, Gerstenbrand F, Binder H, Dimitrijevic MR. Initiating extension of the lower limbs in subjects with complete spinal cord injury by epidural lumbar cord stimulation. Exp Brain Res 154: 308–326, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1666-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mazurek KA, Holinski BJ, Everaert DG, Mushahwar VK, Etienne-Cummings R. A mixed-signal VLSI system for producing temporally adapting intraspinal microstimulation patterns for locomotion. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 10: 902–911, 2016. doi: 10.1109/TBCAS.2015.2501419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Minassian K, Hofstoetter US, Danner SM, Mayr W, Bruce JA, McKay WB, Tansey KE. Spinal rhythm generation by step-induced feedback and transcutaneous posterior root stimulation in complete spinal cord–injured individuals. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 30: 233–243, 2016. doi: 10.1177/1545968315591706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Minassian K, Jilge B, Rattay F, Pinter MM, Binder H, Gerstenbrand F, Dimitrijevic MR. Stepping-like movements in humans with complete spinal cord injury induced by epidural stimulation of the lumbar cord: electromyographic study of compound muscle action potentials. Spinal Cord 42: 401–416, 2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moraud EM, Capogrosso M, Formento E, Wenger N, DiGiovanna J, Courtine G, Micera S. Mechanisms underlying the neuromodulation of spinal circuits for correcting gait and balance deficits after spinal cord injury. Neuron 89: 814–828, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murray LM, Knikou M. Repeated cathodal transspinal pulse and direct current stimulation modulate cortical and corticospinal excitability differently in healthy humans. Exp Brain Res 237: 1841–1852, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s00221-019-05559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]