Abstract

Abstract

Recombinant Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line development for complex biotherapeutic production is conventionally based on the random integration (RI) approach. Due to the lack of control over the integration site and copy number, RI-generated cell pools are always coupled with rigorous screening to find clones that satisfy requirements for production titers, quality, and stability. Targeted integration into a well-defined genomic site has been suggested as a possible strategy to mitigate the drawbacks associated with RI. In this work, we employed the CRISPR-mediated precise integration into target chromosome (CRIS-PITCh) system in combination with the Bxb1 recombinase–mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) system to generate an isogenic transgene-expressing cell line. We successfully utilized the CRIS-PITCh system to target a 2.6 kb Bxb1 landing pad with homology arms as short as 30 bp into the upstream region of the S100A gene cluster, achieving a targeting efficiency of 10.4%. The platform cell line (PCL) with a single copy of the landing pad was then employed for the Bxb1-mediated landing pad exchange with an EGFP encoding cassette to prove its functionality. Finally, to accomplish the main goal of our cell line development method, the PCL was applied for the expression of a secretory glycoprotein, human recombinant soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hrsACE2). Taken together, on-target, single-copy, and stable expression of the transgene over long-term cultivation demonstrated our CRIS-PITCh/RMCE hybrid approach might possibly improve the cell line development process in terms of timeline, specificity, and stability.

Key points

• CRIS-PITCh system is an efficient method for single copy targeted integration of the landing pad and generation of platform cell line

• Upstream region of the S100A gene cluster of CHO-K1 is retargetable by recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) approach and provides a stable expression of the transgene

• CRIS-PITCh/Bxb1 RMCE hybrid system has the potential to overcome some limitations of the random integration approach and accelerate the cell line development timeline

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00253-022-12322-1.

Keywords: CHO cell line development (CLD), Random integration (RI), Targeted integration (TI), CRIS-PITCh, Microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), Recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE)

Introduction

In the mass production of therapeutic proteins in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, which are the main mammalian expression host in the biopharmaceutical industry, cell line development (CLD) is a multi-stage and time-consuming process. It is mostly based on the random integration (RI) of a transgene into the host genome, followed by metabolic selection and gene amplification. The resulting cell pool of RI displays a variety of characteristics, necessitating a costly and laborious screening of thousands of clones to find high-producing and stable clones. Furthermore, copy number variation and unpredictable expression levels continue to be major issues in this technique due to the position effect at the integration site(s) (Hamaker and Lee 2018; Shin and Lee 2020).

With a huge demand for biotherapeutics as well as interest in producing biosimilar versions of this class, the CLD process needs to be continuously refined to reduce time to market and improve quality. Targeted/semi-targeted integration has been noted in the CHO community for decades (Kito et al. 2002). One of the early approaches for developing targeted integration (TI) hosts was recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE), utilizing site-specific recombinases including Cre (Kito et al. 2002), Flp (Kim and Lee 2008), PhiC31 (Ahmadi et al. 2016), and R4 (Lieu et al. 2009). RMCE-driven site-specific integration (SSI) requires the development of a platform cell line (PCL) harboring recombinase recognition sites and a marker gene, referred to as a landing pad (LP) (Srirangan et al. 2020). Implementation of the LP was initially based on RI, followed by extensive screening to obtain founder clones with the highest expression level of the marker (Grav et al. 2018; Shin and Lee 2020).

The release of the CHO-K1 genome sequence (Xu et al. 2011) and the emergence of various genome editing tools have made it possible to move toward next-generation, more rational, and predictable CLD that focuses on the TI of a transgene into a designated locus in the host genome (Shin and Lee 2020; Tihanyi and Nyitray 2021). Since their discovery, programmable nucleases, including zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)–Cas (CRISPR-associated) system, have revolutionized the genetic modification of cultured cells, whole animals, and plants (Gaj et al. 2013; Kim and Kim 2014; Rocha-Martins et al. 2015). In comparison to traditional homologous recombination-based TI, these enzymes’ popularity stems from their ability to induce a targeted double-strand break (DSB) in the genome, which evokes endogenous repair pathways and thus greatly enhances site-specific modification (Bosshard 2019). Among these, the RNA-guided CRISPR/Cas9 system represents a milestone in the field due to its ease of use, high editing efficiency, flexibility, and low cost (Schweickert and Cheng 2020). Two primary repair pathways are activated once programmable nucleases induce a DSB. (1) The error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), in which two broken ends are ligated directly without using a homologous template (Smirnikhina et al. 2019); and (2) the less frequent homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway that utilizes a homologous DNA template for error-free break repair. Thus, HDR can be employed for gene knock-in if the exogenously introduced gene of interest (GOI) is flanked by DNA sequences homologous to the region flanking the DSB (Schweickert and Cheng 2020). HDR-mediated SSI is the most frequent method for TI of the GOI (Lee et al. 2015, 2016; Miao et al. 2018; Zhao et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2019; Pourtabatabaei et al. 2021) or the LP (Inniss et al. 2017; Grav et al. 2018; Chi et al. 2019; Pristovšek et al. 2019; Sergeeva et al. 2020) in CHO cells using CRISPR/Cas9.

Although harnessing HDR for gene knock-in enables accurate insertion of the GOI, it needs long homology arms (500–1000 bp), which makes the donor vector construction laborious and increases its size. Besides, targeting efficiency relies on HDR frequency in the cell types or organism species. Recently, Nakade et al. introduced a novel strategy for gene knock-in termed PITCh (precise integration into target chromosome) system that takes advantage of the microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) repair mechanism rather than HDR or NHEJ (Nakade et al. 2014).

PITCh method applies very short microhomologies (≤ 40 bp) for precise integration of the GOI, which can be easily added through PCR or oligonucleotide annealing (Sakuma et al. 2015, 2016). Thanks to the in vivo linearization of the donor vector in this system, a backbone-free integration can be performed. More importantly, owing to the relatively short microhomology arms, long-range PCR is not needed for knock-in confirmation, which can help speed up the process of on-target verification (Sakuma et al. 2015; Lau et al. 2020).

Despite the fact that nuclease-mediated SSI is considered a breakthrough in this field, recombinase-mediated SSI has maintained its place in a technique known as the hybrid approach, which combines CRISPR/Cas9 and RMCE for precise and robust CLD. Inniss et al. (2017) were the first to apply this method to develop a monoclonal antibody-producing CHO cell line. Although this procedure necessitates PCL generation, the rationale behind it, is that once generated, fully characterized PCL can be reused to produce another GOI, allowing for faster cell line generation. RMCE occurs in a conservative manner, with no cell type biases or reliance on DSB repair pathways, and there is no limitation on donor vector size (Srirangan et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2021).

Several published studies and patents from major pharmaceutical companies indicate that the hybrid strategy is gaining popularity in CLD departments (Inniss et al. 2017; Ng et al. 2021). Pfizer, as a pioneer in this regard, reported that material produced from cell pools of RMCE is highly comparable to clones in terms of quality attributes and thus can be used for early molecular assessment of candidates and toxicology studies (Scarcelli et al. 2017). In addition to their industrial application for recombinant protein production, PCLs, especially the targeted ones, are of great interest in the academic sector for basic research. They have been used as isogenic cells for comparative cell engineering studies to evaluate the effect of different transgenes on the host transcriptome (Grav et al. 2018) or for fast screening of different expression cassettes (Pristovšek et al. 2019).

In this study, intending to improve the hybrid approach to accelerate the generation and characterization of PCLs and stable producer CHO cells, we applied a two-step strategy. In the first step, we successfully employed the PITCh system for SSI of the Bxb1 LP into the upstream region of the S100A gene cluster to develop the CHO-K1 PCL by applying homology arms as short as 30 bp. In the next step, we demonstrated the functionality of our PCL by retargeting the EGFP cassette into the incorporated LP using the Bxb1 RMCE system. For practical application, the PCL was also used to produce human recombinant soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hrsACE2), a secretory glycoprotein recently introduced as a potential treatment for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Monteil et al. 2020, 2022). We found that the CRIS-PITCh/RMCE hybrid system can serve as an efficient tool for rapid, precise, and reliable transgene-expressing CHO cell line development. Moreover, using the PITCh system in the hybrid technique would be very beneficial for increasing experiment throughput, such as the creation of homotypic or heterotypic multi-LP cell lines. These kinds of PCLs are valuable for multicopy TI of transgenes or TI of an effector gene to increase single-copy transgene production titers (Sergeeva et al. 2020; Shin et al. 2021).

Material and method

sgRNA design and plasmid construction

To construct an all-in-one plasmid containing tandem U6-PITCh gRNA, U6-genome targeting gRNA, and Cas9 nuclease, the single-stranded oligos for PITCh gRNA designed by Sakuma et al. (2016) were synthesized, phosphorylated, annealed, and cloned into the BbsI site of pU6-(BbsI)-CBh-Cas9-T2A-mCherry (Addgene plasmid #64,324) according to the Zhang lab’s protocol (Ran et al. 2013). Using XbaI forward and KpnI reverse primers, the U6 promoter and the PITCh gRNA (variable region + gRNA scaffold) were PCR amplified. The PCR fragment was digested by XbaI and KpnI and cloned into the pU6-(BbsI)-CBh-Cas9-T2A-mCherry and the resulting vector termed pU6-(BbsI)-CBh-Cas9-T2A-mCherry-PITCh gRNA. Genome-targeting gRNAs were designed using the CRISPOR online tool (http://crispor.tefor.net/). Subsequently, the single-stranded oligos were synthesized, phosphorylated, annealed, and cloned into the BbsI site of pU6-(BbsI)-CBh-Cas9-T2A-mCherry-PITCh gRNA. A schematic of the cloning steps is represented in supplementary Fig. S1.

Donor plasmid for the LP construct contained Bxb1 attP sequence, herpes simplex virus-1 thymidine kinase (HSV-TK), T2A, and puromycin resistance (puroR) expression units under PGK promoter, SV40 polyA, and Bxb1 GA mutant attP sequence (attP-PGK-TK-2A-PuroR-SV40 polyA-mut attP), flanked by 30 bp microhomology arms and PITCh gRNA cut sites (pattP-TK-PuroR). Donor plasmid for RMCE contained EGFP expression unit under CMV promoter and SV40 polyA flanked by Bxb1 attB and GA mutant attB sequences (attB-CMV-EGFP-SV40 polyA-mut attB) (pattB-EGFP, GenBank accession number: OP846958). LP and RMCE donor vectors were designed in silico and synthesized by Bio Basic Inc. (Canada). To remove unwanted integrants after ganciclovir (GCV) selection, the PGK promoter and HSV-TK coding sequence were PCR amplified from the LP construct and cloned into the KpnI/XbaI digested RMCE donor backbone outside of the retargeting cassette. Primers were synthesized by Metabion (Germany) and are listed in supplementary table S1. All constructs were confirmed with sequencing (Macrogen, South Korea).

Cell culture, transfection, and stable cell line generation

The adherent CHO-K1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-Ham's F-12 (DMEM-F12) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Biosera), incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified cell incubator, and passaged every 3–4 days.

For targeted integration of the LP (PCL generation) using CRISPR-PITCh system, CHO-K1 cells were seeded at a density of 8 × 104 cells/mL in a 24-well plate one day before transfection. The cells (80% confluent) were co-transfected with the Cas9-sgRNAs vector (250 ng) and LP donor vector (250 ng) using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Forty-eight-hour post-transfection, cells were transferred into the 6-well plates at 40–50% confluency. The next day (72-h post-transfection), cells were subjected to antibiotic selection pressure by adding 5 μg/mL of puromycin (ABM, Canada) into each well. Culture medium exchange was performed every 2–3 days, and selection continued for 10 days until stable colonies emerged and consequently expanded. The cells were then analyzed by 5′/3′ junction PCRs and further single-cell cloned by limiting dilution at 1 cell/well density in 200 μl medium in 96-well plates. After clonal expansion, single colonies were re-plated into the 24-well plates, then expanded in 6-well plates and validated using 5′/3′ junction and out-out PCRs, copy number determination by qPCR, and growth profile analysis.

For the generation of the EGFP-expressing cell line, CHO-K1 platform cells were co-transfected with the Bxb1 recombinase vector (Addgene plasmid #51,552) and the EGFP-encoding vector (targeting plasmid) at 1:3 ratio using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent. Transfected cells were re-seeded into 6-well tissue culture plates 72 h after transfection and subjected to 4 μM GCV selection on day 8. Cells recovered from the selection were then cloned by limiting dilution at 1 cell/well density in 200 μl medium in 96-well plates.

Fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry

Recovered EGFP single clones were passed from 96-well plates to 24-well plates and EGFP expression was monitored under a fluorescence microscope. EGFP-expressing clones were then subcultured into 6-well plates. When confluent, they were trypsinized and re-suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 1% FBS and analyzed on a flow cytometer (Cyflow) to quantify EGFP+ cells. Only clones with homogenous EGFP expression (≥ 97% GFP-positive cells) were chosen.

Genomic DNA extraction and PCR amplification (junctions and out-out PCRs)

The Cell & Tissue DNA Extraction Kit (Gene Transfer Pioneers (GTP), Iran) or a NaOH/TRIS–HCl-based protocol (Freire 2017) were used to extract genomic DNA from cell pellets. To obtain cell lysates from single-cell clones, 20 μl of 0.2 M NaOH was added to the cell pellets; the reaction was incubated at 75 °C for 10 min and then neutralized by adding 180 μl of 0.04 M TRIS–HCl (pH = 7.8). The lysates were stored at − 20 °C. 2.5 μl of each lysate was added as a template to the corresponding 5′/3′ junction PCR reaction. For long-range out–out PCR, which is a PCR with a primer pair flanking the target site (preferably outside the homology arms) on genomic DNA, and other experiments, genomic DNA was extracted from 1 × 106 cells using the Cell & Tissue DNA Extraction Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To confirm on-target integration of the LP, 5′/3′ junction PCR was performed using 2 × PCR Master Mix Red (Ampliqon, Denmark) with specific primers binding outside of homology arms in the genomic locus (5′ forward and 3′ reverse primers) and primers specific to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cassette (5′ reverse and 3′ forward primers) according to the following PCR program: 95 °C for 5 min; 30 × : 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 40 s (5′ junction) and 1 min (3′ junction), and 72 °C for 10 min. Out-out PCR was carried out using Super PCR Master Mix 2x (Yekta Tajhiz Azma Co., Iran) according to the following PCR program: 95 °C for 5 min; 30 × : 95 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 3 min and 30 s and 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel.

To verify the proper replacement of the LP with the EGFP cassette, 5′/3′ junction PCR was performed on the stable cell pool and single clones under the following conditions: 95 °C for 5 min; 30 × : 95 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 10 min. PCR primers for junctions and out–out PCRs are listed in supplementary table S1.

Copy number analysis using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and growth curve determination

To investigate the absolute copy number of the TK and EGFP in single clones, qRT-PCR was performed on genomic DNA samples using 2 × Real-Time PCR Master Green (Amplicon, Denmark) on the Rotor-Gene™ 6000 system (Corbett Life Sciences). The extracted gDNAs were diluted to 10 ng/μl, and 2 μl were used as templates in the reaction mixture, including SYBR Green QPCR master mix and 200 nM of forward and reverse primers. Amplification was carried out under the following conditions: 95 °C for 15 min, 40 × :95 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 15 s. The standard curve was generated with a tenfold serial dilution of linearized pattP-TK-Puro and pattB-EGFP in a range of 108–102, resulting in good linearity (R2 = 0.99) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Copy number was calculated using the following equation (Lee et al. 2006):

Given that the CHO-K1 genome size was reported to be 2.6 Gb (Xu et al. 2011), the average genomic DNA content per diploid cell was estimated to be about 6 pg in order to calculate the transgene copy number per genome of CHO cell. If the calculated value was in the range of 0.7–1.3 (for LP clones) and 0.5–1.5 (for EGFP clones) (including standard deviations), clones were assumed to have one copy.

The relative copy number of EGFP was quantified using qRT-PCR on genomic DNA samples using β-actin as the reference gene. Reaction mixtures included SYBR Green QPCR master mix and 200 nM of each primer. Amplification was carried out under the following conditions: 95 °C for 15 min, 40 × :95 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 20 s. Efficiency was estimated by the LinReg method (Ramakers et al. 2003), and the relative copy number was calculated using the pfaffl method (Pfaffl 2001) with respect to clone R39 as the calibrator.

All PCR reactions were run in duplicate, and no-template controls (NTC) were included in each PCR run. Sequences of primers are listed in supplementary table S1.

To compare the growth profiles of a single-copy LP-targeted clone with the wild-type CHO-K1, cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a starting seeding density of 3 × 104 cells/well. For each day, two wells were considered. Cells were cultivated in batch mode and were counted at daily intervals until the culture reached the death phase (Freshney 2010).

Assessment of the long-term stability of transgene expression

Based on real-time results, three single-copy EGFP-expressing clones were passaged every 2–3 days for approximately 10 weeks in 6-well plates containing 2 mL of culture medium. At each passage, the seeding density was set at 5 × 104 cells/mL. The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) values of each clone and the percentage of EGFP-expressing cells at passages 0, 10, and 20 were measured by flow cytometry using BD FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Data analysis was performed with FlowJo 10 (FlowJo LLC).

Generation and characterization of targeted hrsACE2-producing CHO cells

To demonstrate the applicability of our CRISP-PITCh/RMCE hybrid method with a secretory glycoprotein, the generated CHO-K1 PCL was retargeted with the hrsACE2 expression cassette. To this end, the hrsACE2 sequence synthesized by GenScript was PCR amplified with G-HiFi DNA polymerase (Smobio, Taiwan) using NheI forward and XhoI reverse primers (supplementary table S1). The NheI/XhoI digested PCR product was cloned into the RMCE donor vector, substituting GFP with hrsACE2 (pattB-ACE2, GenBank accession number: OP846959). The PCL was co-transfected with the Bxb1 recombinase vector and pattB-ACE2 donor vector at a 1:3 ratio using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent and GCV selection (4 μM) was started on day 8 after transfection. Colonies that emerged under GCV selection were isolated using colony picking method and transferred to a 12-well tissue culture plate. The genomic DNA of each clone as well as the pool of clones was extracted for further junction PCR analysis. 5′/3′ junction PCR was performed under following condition: 95 °C for 5 min; 30 × : 95 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel. Primer sequences are listed in supplementary table S1.

Protein expression and purification by affinity chromatography

A 5′/3′ junction PCR-positive clone was expanded in T-75 flasks, and the culture supernatant (25 ml) was collected and filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane filter for protein expression analysis. The sample was loaded on the Ni–NTA agarose column (QIAGEN) after equilibration with the binding buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole; pH 8.0). Following the washing step (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole; pH 8.0), protein was eluted using the elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole; pH 8.0). The elution fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and western blotting.

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

Twenty-five microliters of each sample were mixed in SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol and boiled at 90 °C for 5 min and subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE on an 8% polyacrylamide gel. Protein bands were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, UK) in a wet transfer system. The membrane was blocked with 3% (w/v) skim milk in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, the membrane was washed 3 times with PBS and then incubated with 1:1000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-His-tag antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at room temperature. After the washing step with PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween-20, 3,3′ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) solution was added to visualize the desired bands.

Estimation of protein productivity

The concentration of the purified hrsACE2 in the targeted and random integration cell pools was estimated by densitometric analysis using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, USA). Standard bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Thermo Scientific, USA) was serially diluted and used for standard curve preparation.

Results

Guide RNA design and plasmids construction for MMEJ-mediated transgene targeting into the upstream site of the S100A gene cluster

S100A gene cluster encodes a group of calcium-binding proteins, e.g., S100A1, S100A13, S100A14, S100A16, S100A3, S100A2, S100A4, S100A5, and S100A6 which are divided into side cluster (S100A1, S100A13, S100A14, S100A16) and main cluster (S100A3, S100A4, S100A5, S100A6), having the NCBI Reference Sequence: NW_003613854.1. According to a previous publication, TI of a transgene within the upstream and downstream regions of the main cluster enabled predictable, high-level, and stable production during 60 days of culture (Mueller et al. 2019). First, the intended genomic target site was PCR amplified, and the product was sent for Sanger sequencing. BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) analysis against the Chinese Hamster (Cricetulus griseus) representative genome revealed a 100% identity between the sequencing result and the NCBI Reference Sequence: NW_003613854.1 (data not shown). Then, two sgRNAs were designed, and the Cas9/gRNA expression vectors for the CRIS-PITCh system were constructed. For TI of the Bxb1 LP via the MMEJ repair pathway, microhomology arms < 40 bps in length and vector linearization are required. To this end, 30 bp 5′ and 3′ microhomology arms were designed to flank the cleavage site of sgRNA1 (which had a higher efficiency score than sgRNA2 according to the CRISPOR tool). The LP containing a cassette that co-expressed HSV-TK and puromycin resistance proteins under the PGK promoter was flanked by orthogonal Bxb1 attP sites. Notably, the attP sites were put in inverse orientation to prevent plasmid backbone integration. To fulfill the requirement of the CRIS-PITCh system for in vivo vector linearization, the PITCh gRNA target sequence was placed on either side of the microhomology arms in a direction that cleavage could occur outside the microhomology arms (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

TI of the Bxb1 LP into predefined region utilizing the CRIS-PITCh system. a Overview of targeting strategy of the LP donor into the predetermined region. LP donor vector consisted of herpes simplex virus-1 thymidine kinase (HSV-TK), T2A, and puromycin resistance (puroR) coding sequences under PGK promoter and SV40 polyA flanked by Bxb1 wild type attP and GA mutant attP sequences, the LP was placed between 30 bp homology arms and PITCh gRNA cut site was put on either side. TI of the entire cassette (2.6 kb) through MMEJ occurs following limited end resection of DSB and annealing of microhomology arms. Primer sites for 5ʹ/3′ junction and out-out PCRs are noted. Sg represents the cut site of PITCh gRNA and MHA stands for microhomology arm. b Agarose gel electrophoresis results of 5´/3´ junction PCR and out-out PCR on stable cell pools of sgRNA1 and sgRNA2. The expected PCR product size for 5´ junction, 3´ junction, and out–out PCRs were 666, 1075, and 3289 bp, respectively. c Agarose gel electrophoresis results of out-out PCR on stable single clones. Asterisks indicate positive clones. M, 1 kb DNA ladder. N, negative control

Development of a CHO-K1 PCL through CRIS-PITCh-mediated knock-in

To achieve TI of the designed LP into the desired region of the CHO-K1 genome, cells were co-transfected with the LP donor vector and corresponding Cas9/gRNAs vector. Puromycin selection was initiated 3 days after transfection and lasted 10 days. Genomic DNA was then extracted from stable cell pools, and TI of the LP was verified by 5′/3′ junction PCR and subsequent long-range out–out PCR. The positions of the primers for 5′/3′ junction PCR and out-out PCR are shown in Fig. 1a. On stable cell pools of both sgRNA1 and sgRNA2, 5′ and 3′ junction PCRs, as well as out-out PCRs, produced amplicons with predicted sizes (666, 1075, and 3289 bp, respectively) (Fig. 1b). A 609 bp band in the out–out PCR of the stable cell pool could be related to either mono-allelic integration, random integration, or non-integrants. After confirming stable cell pools, single-cell cloning of the stable cell pool of sgRNA1 was performed using limiting dilution. A total of 125 single clones were recovered and analyzed for TI using 5′/3′ junction PCR. Twenty-one out of 125 (16.8%) were 5′/3′ junction positive (Supplementary Fig. S3). Out–out PCR demonstrated that of 21 junction PCR-positive clones, 13 (61.9% or 10.4% overall) were successfully targeted with the whole LP construct. Despite a 3289 bp band, seven clones (33, 41, 55, 62, 86, 99, and 123) displayed a 609 bp band, indicating monoallelic integration (Fig. 1c).

Absolute copy number and growth profile analysis of LP-targeted integrants

To further characterize 13 out–out PCR-positive clones, the absolute copy number of the LP was determined using qRT-PCR. The result showed that four clones contained one copy of the LP cassette (clones 33, 62, 86, and 99). Among two-copy clones, clones 35, 47, and 81 represented biallelic integration, and clone 55 displayed mono-allelic integration based on out–out PCR results, so we assumed that in clone 55, one copy of the LP was integrated randomly. Clones 32 and 49 displayed three copy numbers, of which two copies are at the desired site based on out–out PCR results (Figs. 1c and 2a). Clone 41 was excluded from copy number analysis due to the multi-Ct result.

Fig. 2.

A Absolute copy number of the LP cassette in single clones. The plot represents the absolute copy number of TK in targeted clones confirmed by out-out PCR. A linearized LP donor vector was used for standard preparation. The error bars show standard deviations of technical replicates (n = 2). b Growth profile of cells harboring a single copy of the LP (clone 62) and wild-type CHO-K1. Error bars show standard deviations of technical replicates (n = 2)

Overall, the results of 5ʹ/3′ junction PCR, out–out PCR, and copy number analysis indicated clones 33, 62, 86, and 99 harbor a single copy of the LP in the desired locus and can be considered as PCLs.

To further study the growth behavior of single-copy targeted clones, growth profile analysis on clone 62 was performed. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, the growth profile of clone 62 showed a small downward shift compared to wild-type CHO-K1, presumably as a result of the increased metabolic burden on cells that carry the genes for puromycin resistance and thymidine kinase.

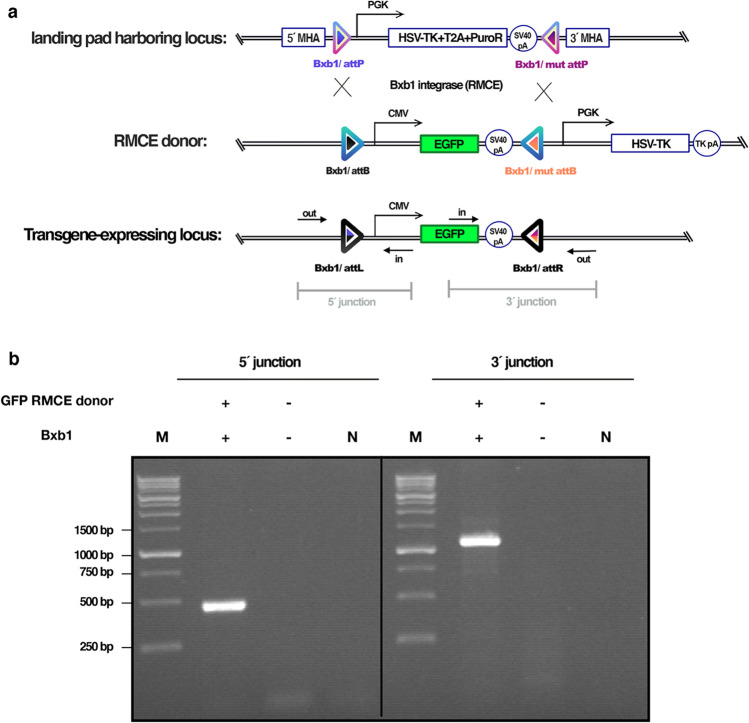

Development of an EGFP-expressing cell line using the Bxb1 RMCE system

To investigate the PCL’s functionality, we needed to ensure that the Puro-TK LP could be properly recombined with another GOI harboring cassette. Hence, the Bxb1 attB-flanked EGFP encoding vector was used as a targeting vector. Clone 62 was co-transfected with the EGFP donor vector and Bxb1 recombinase vector. On day 8 post-transfection, cells were subjected to GCV selection, and colonies that emerged were examined under a fluorescence microscope. The EGFP-expressing cells were passed to the T25 flask, and genomic DNA was extracted when confluent. To determine whether the cells undergo proper RMCE, 5′/3′ junction PCR was performed. The binding sites of the junction primers are displayed in Fig. 3a. DNA band of the correct size in both 5′ junction PCR (about 400 bp) and 3′ junction PCR (about 1100 bp) confirmed the proper exchange of the LP with the EGFP cassette (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

TI of the GOI (EGFP) into the PCL using Bxb1 RMCE system. a Schematic representation of the Bxb1 RMCE strategy into the PCL genome. RMCE donor consisted of EGFP coding sequence under CMV promoter and SV40 polyA flanked by the Bxb1 wild type attB and GA mutant attB sequences. Primer sites for 5ʹ/3′ junction and out-out PCRs are noted. b Agarose gel electrophoresis results of 5´/3´ junction PCR on the cell pool co-transfected with EGFP donor vector and Bxb1 integrase after GCV selection. The expected PCR fragment sizes were about 400 bp and 1100 bp for 5´ and 3´ junction PCRs, respectively. M, 1 kb DNA ladder. N, Negative control

Flow cytometry analysis of EGFP-expressing clones

RMCE clones were evaluated for EGFP expression approximately 2 weeks following the limiting dilution of the EGFP cell pool. Twelve of the 35 single clones (R3, R4, R26, R27, R29, R33, R37, R39, R40, R45, R47, and R48) displayed EGFP expression when examined under a fluorescence microscope. These clones were then analyzed by flow cytometry. CHO-K1 parental cells were used to set the gate for EGFP-positive cells. Flow cytometry data demonstrated that in 7 EGFP clones, ≥ 96% of cells were positive for EGFP expression (clones R26, R27, R37, R39, R40, R47, and R48). The remaining 5 clones were considered non-clonal (clones R3, R4, R29, R33, and R45) and excluded from further analysis (supplementary Fig. S4).

RMCE confirmation in EGFP-positive clones using 5′/3′ junction PCRs

5′/3′ junction PCRs were used to confirm that EGFP-positive clones were successfully recombined cells rather than the result of random EGFP cassette integration. All clones with homogenous EGFP expression demonstrated the correct band sizes of about 400 bp and 1100 bp in 5′ and 3′ junction PCR, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis results of 5´/3´ junction PCR on stable EGFP RMCE clones. The expected PCR product size for 5′ and 3′ junctions were about 400 and 1100 bp, respectively. M, 1 kb DNA ladder. N, Negative control

Absolute and relative copy number analysis in EGFP-targeted integration clones

qRT-PCR was used to further quantify the copy number of the EGFP in seven EGFP-positive clones. Copy number was calculated the same way as the copy number of LP clones was determined. Results of absolute qRT-PCR indicated that all seven clones successfully harbored a single copy of the EGFP cassette (Fig. 5a) supposedly due to the high specificity of the Bxb1 RMCE approach. Relative quantification of the EGFP demonstrated that all clones carried the same number of EGFP transgene (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

qRT-PCR for quantifying EGFP copy number in clonal cells. a Absolute copy number analysis of the EGFP cassette in single clones. The plot represents the absolute copy number of EGFP in targeted clones confirmed by 5´/3´ junction PCR. Linearized EGFP donor vector was used for standard preparation. b Relative copy number analysis of the EGFP cassette in single clones. Clone R39 considered as the calibrator. The error bars show standard deviations of technical replicates (n = 2)

Long-term culture to evaluate transgene expression stability

To evaluate the effect of long-term culture on the stability of transgene expression, three single-copy EGFP-expressing clones (R37, R39, and R40) were cultured for 10 weeks with cryopreservation after every 2–3 passages. The cryopreserved cultures from weeks 0, 5, and 10 were thawed and cultured concurrently after completion. The MFI value of each clone and the percentage of EGFP-positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. CHO-K1 parental cells were used to set the gate for EGFP-positive cells. During long-term cultivation, clone R39 displayed the most stable EGFP expression. In clones R37 and R40, there was a slight decrease in EGFP expression (Fig. 6a). Until the completion of the experiment, the percentage of EGFP-positive cells in all clones remained > 99% (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Long-term culture stability analysis of EGFP-targeted clones. a The MFI value was measured in clones R37, R39, and R40 with a single copy of the EGFP cassette at passage 0 (P0), passage 10 (P10), and passage 20 (P20). The EGFP expression profile at P0, P10, and P20 is illustrated by pink, blue, and orange lines, respectively. The gray-colored histogram represents CHO-K1 cells as negative control. b Percentage of EGFP-expressing cells of stable clones (R37, R39, and R40) during 20 passages

Generation and evaluation of targeted hrsACE2-producing CHO cells

For practical applications, the secretory glycoprotein hrsACE2 was expressed in our PCL. Due to its post-translational modification (glycosylation and generation of disulfide bonds), mammalian hosts are the preferred hosts for its production. The CHO-K1 platform cells retargeted with the hrsACE2 coding sequence were isolated through GCV selection, and the genomic DNA of recovered cells was subjected to junction PCR analysis. Successful TI of the hrsACE2 cassette in the pool of cells (Fig. 7a) and single clones (Fig. 7b) is indicated by bands of approximately 400 bp and 600 bp in the 5′ and 3′ junction PCRs, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Generation of hrsACE2-producing CHO cells using Bxb1 RMCE system. a Agarose gel electrophoresis results of 5´/3´ junction PCR on the cell pool co-transfected with hrsACE2 donor vector and Bxb1 integrase after GCV selection. b Agarose gel electrophoresis results of 5´/3´ junction PCR on single clones. The expected PCR fragment sizes were about 400 bp and 600 bp for 5´and 3´ junction PCRs, respectively. M, 1 kb DNA ladder. N, Negative control

Detecting targeted hrsACE2 expression

To confirm the expression of targeted hrsACE2, affinity-purified culture supernatant from clone 1 was subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis under reduced conditions. On SDS-PAGE, hrsACE2 could show up as a band(s) ranging from 83 to 120 kDa, depending on the glycosylation pattern (Schuster et al. 2010). SDS-PAGE analysis represented a 120 kDa band (Fig. 8a), indicating that our PCL enables the expression of homogenous, highly glycosylated hrsACE2. Western blot analysis was also performed to confirm the identity of purified hrsACE2. The band detected in the western blot was consistent with that detected on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Protein purification and identification. a Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel (8%) of the elution fractions together with initial supernatant and flowthrough under reduced condition. b Reduced western blotting analysis using HRP-conjugated anti-His-tag antibody. M, Mw marker. N, negative control

Estimation of protein productivity

Purified hrsACE2 from a TI and RI cell pool as well as a twofold dilution series of a standard BSA were run on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel, and densitometric analysis was performed (supplementary Fig. S5a). Considering the volume of cell culture supernatant subjected to purification, we obtain an expression level of 0.9 μg/ml and 0.3 μg/ml for TI and RI cell pools, respectively (supplementary Fig. S5b).

Discussion

TI of the GOI into a safe harbor site is a promising strategy for addressing the unexpected and unstable expression level generated by RI. In this study, we developed a hybrid system that combines MMEJ-mediated knock-in with Bxb1-mediated cassette exchange for rapid and precise integration of the GOI into the host genome. In the initial part of the experiment, the MMEJ repair pathway of CHO cells was employed to knock in the Bxb1 LP, 2.6 kb in size, into the desired hot spot using CRIS-PITCh technology.

Only 60 bp of the 5.5 kb LP donor vector was occupied by microhomology arms; hence, it can save space for larger cassettes in comparison to HDR donors with 500–1000 bp homology arms. Out–out PCRs revealed that not all 5´/3´ junction PCR-positive clones were likewise positive in more precise out–out PCR which is consistent with Lee et al. (2015). So, using out–out PCR results in our calculations, we achieved a targeting efficiency of 10.4% following puromycin selection, which is high enough for recombinant CHO cell line development. In 2018, Kawabe et al. utilized the PITCh system for TI of an scFv-Fc cassette into the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) locus of the CHO genome and reported a 50% knock-in efficiency (Kawabe et al. 2018). It should be emphasized that disrupting the HPRT gene confers an endogenous selection property to their knocked-in cell line, enabling them to enrich on-target cells with 6-thioguanine selection, therefore together with puromycin selection; they applied a dual selection system and screened more enriched cells than in our study. However, aside from selection strategies, the targeted locus in terms of chromatin accessibility, gRNAs efficiency, and transgene cassette size all may have a great impact on editing efficiency (Shy et al. 2016; Jensen et al. 2017). Although in vivo vector linearization increases the chance of DNA integration into the host chromosome (Potter and Heller 2011), which may consequently increase the probability of RI, out–out PCR results together with copy number analysis demonstrated that the PITCh method allows for single-copy TI of the LP (4 out of 12 clones). Furthermore, according to the out-out PCR, clones 35, 47, and 81 with two copy numbers of the LP are homozygous and so considered on-target integrants. Clones 100 and 123 have unexpected copy numbers (0.28 and 0.59, respectively) which do not match out–out PCR results, probably due to non-clonal cell populations, or the subpopulation creation through mutation or translocation of the LP cassette as a result of a metabolic burden on cells. These kinds of unusual copy numbers were also determined in clones from HDR-mediated knock-in (Lee et al. 2015; Freire 2017).

We verified our PCL in the second stage of our experiment by retargeting the EGFP cassette in the presence of the Bxb1 integrase. After a short period of negative selection, EGFP-expressing cells emerged, demonstrating that the LP is accessible to recombination and expression machineries. Although it was believed that by inserting the HSV-TK cassette into the backbone of the RMCE vector, as Chi et al. did in their CRISPR-Cas9/PhiC31 hybrid approach (Chi et al. 2019) any unwanted recombination events would be prevented, 23 out of 35 clones were non-GFP expressing after GCV selection. This is in line with the previous findings that suggest GCV counter selection is inadequate to remove all non-exchanged parental cells (Qiao et al. 2009; Reese and Ku 2021). The selection strategies in RMCE systems can be significantly improved by applying promoter trap or poly (A) trap strategies (Inniss et al. 2017; Pristovšek et al. 2019). Moreover, in accordance with Bateman’s suggestion, we placed the att sites in reverse orientation. This prevents LP exchange with the plasmid backbone rather than the GOI cassette (Bateman et al. 2006; Turan et al. 2013). Overall, this strategy along with the use of a combination of selection strategies such as that utilized by Inniss et al., who combined FACS enrichment, negative selection, and antibiotic selection (Inniss et al. 2017) could potentially boost the homogeneity of the hybrid approach.

According to copy number analysis, all seven clones had a single copy of the EGFP cassette, implying the high specificity of Bxb1-mediated SSI. This also indicates that this approach can provide great homogeneity, which consequently reduces screening time. Although RMCE clones were generated from the same PCL, their stability profiles differed, with clones R37 and R40 showing a reduction in MFI in passage 20 compared to clone 39, in which EGFP expression remained constant after 20 passages. One reason for this reduction could be epigenetic silencing of transgene because CMV promoter is prone to methylation (Kim et al. 2011; Jia et al. 2018), which is one of the major causes of instability over time. Clones derived from the same PCL might not be identical in terms of epigenetic factors such as DNA methylation rate although more research is needed to confirm this phenomenon. In a comparative study with four distinct promoters including CMV, SV40, EF1α, and CP promoters, in three different integration sites, CMV promoter showed the highest cell-to-cell variation in all three sites (Pristovšek et al. 2019). Besides, stochasticity of gene expression could be another source of cell-to-cell variability even among genetically identical cells (Lee et al. 2019).

To achieve the ultimate goal of our CLD strategy, a secretory glycoprotein, hrsACE2, was also expressed in our PCL. The resulting homogeneous cell pool enabled the quick isolation and characterization of transgene-expressing single clones. This is a significant improvement over the RI method, which generally takes 4 to 5 months (Stuible et al. 2018). Although, in comparison to a randomly integrated cell pool, a threefold expression level was achieved; it is far from satisfying the industrial requirement. It should be noted that protein expression was performed at lab scale under non-optimized conditions in terms of culture media, culture mode, and CHO strain. This finding is consistent with other studies (Gaidukov et al. 2018; Ding et al. 2022).

Collectively, the upstream region of the S100A gene cluster, as the selected integration site, meets the three criteria proposed by Qiao et al. (2009) stable expression, targetable, and single copy accommodation of the GOI. We established transgene-expressing cell line in as short as 2 weeks after developing and characterizing our PCL. Thus, our hybrid strategy can potentially circumvent some limitations of RI for homogenous stable cell line development, rapidly and precisely. The results of this work have the potential to be applied to engineering-based chassis platform CHO cell production.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Pasteur Institute of Iran as a Ph.D. dissertation (grant no. BD-9579) and National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD’s project no. 978694).

Author contribution

Conceptualization: [FD, SGH], methodology: [SGH, FD, MA, PFE, EB, MHM], formal analysis and investigation: [SGH], investigation-supporting: [EB], writing — original draft preparation: [SGH], writing – review and editing: [SGH, FD, MA, PFE, MHM], funding acquisition: [FD], resources: [FD, SGH, MA, PFE], supervision: [FD].

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Ethics approval

No human or animal participants were involved in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmadi M, Mahboudi F, Akbari Eidgahi MR, Nasr R, Nematpour F, Ahmadi S, Ebadat S, Aghaeepoor M, Davami F. Evaluating the efficiency of phiC31 integrase-mediated monoclonal antibody expression in CHO cells. Biotechnol Prog. 2016;32:1570–1576. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman JR, Lee AM, Wu C-T. Site-specific transformation of Drosophila via ϕC31 integrase-mediated cassette exchange. Genetics. 2006;173:769–777. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.056945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosshard S (2019) Study of DNA repair and recombination mechanisms in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Doctoral dissertation, Université de Lausanne, Faculté de biologie et médecine

- Chi X, Zheng Q, Jiang R, Chen-Tsai RY, Kong L-J. A system for site-specific integration of transgenes in mammalian cells. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0219842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Chen Y, Wu H, Yang Z, Cai Y, Dai Y, Xu Q, Jin J, Li H (2022) Construction of a CHO cell line with site-specific integration to stably express exogenous proteins using the CRISPR–Cas9 technique. Syst Microbiol Biomanufacturing 1–10. 10.1007/s43393-022-00147-y

- Freire CAM (2017) Genome editing via CRISPR / Cas9 targeted integration in CHO cells. MA Thesis Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon, Portugal

- Freshney RI (2010) Culture of animal cells: a manual of basic technique and specialized applications, 6th edn. John Wiley & Sons

- Gaidukov L, Wroblewska L, Teague B, Nelson T, Zhang X, Liu Y, Jagtap K, Mamo S, Tseng WA, Lowe A, Das J, Bandara K, Baijuraj S, Summers NM, Lu TK, Zhang L, Weiss R. A multi-landing pad DNA integration platform for mammalian cell engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:4072–4086. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grav LM, Sergeeva D, Lee JS, Marin de Mas I, Lewis NE, Andersen MR, Nielsen LK, Lee GM, Kildegaard HF. Minimizing clonal variation during mammalian cell line engineering for improved systems biology data generation. ACS Synth Biol. 2018;7:2148–2159. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaker NK, Lee KH. Site-specific integration ushers in a new era of precise CHO cell line engineering. Curr Opin Chem Eng. 2018;22:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inniss MC, Bandara K, Jusiak B, Lu TK, Weiss R, Wroblewska L, Zhang L. A novel Bxb1 integrase RMCE system for high fidelity site-specific integration of mAb expression cassette in CHO Cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2017;114:1837–1846. doi: 10.1002/bit.26268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KT, Fløe L, Petersen TS, Huang J, Xu F, Bolund L, Luo Y, Lin L. Chromatin accessibility and guide sequence secondary structure affect CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing efficiency. FEBS Lett. 2017;591:1892–1901. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia YL, Guo X, Lu JT, Wang XY, Qiu L le, Wang TY (2018) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout for DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a in CHO cells displays enhanced transgenic expression and long-term stability. J Cell Mol Med 1–11. 10.1111/jcmm.13687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kawabe Y, Komatsu S, Komatsu S, Murakami M, Ito A, Sakuma T, Nakamura T, Yamamoto T, Kamihira M. Targeted knock-in of an scFv-Fc antibody gene into the hprt locus of Chinese hamster ovary cells using CRISPR/Cas9 and CRIS-PITCh systems. J Biosci Bioeng. 2018;125:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Kim JS. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:321–334. doi: 10.1038/nrg3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, O’Callaghan PM, Droms KA, James DC. A mechanistic understanding of production instability in CHO cell lines expressing recombinant monoclonal antibodies. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:2434–2446. doi: 10.1002/bit.23189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Lee GM. Use of Flp-mediated cassette exchange in the development of a CHO cell line stably producing erythropoietin. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;18:1342–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kito M, Itami S, Fukano Y, Yamana K, Shibui T. Construction of engineered cho strains for high-level production of recombinant proteins. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;60:442–448. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C-H, Tin C, Suh Y (2020) CRISPR-based strategies for targeted transgene knock-in and gene correction. Fac Rev 9. 10.12703/r/9-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee C, Kim J, Shin SG, Hwang S. Absolute and relative QPCR quantification of plasmid copy number in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 2006;123:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Grav LM, Pedersen LE, Lee GM, Kildegaard HF. Accelerated homology-directed targeted integration of transgenes in Chinese hamster ovary cells via CRISPR/Cas9 and fluorescent enrichment. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:2518–2523. doi: 10.1002/bit.26002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Kallehauge TB, Pedersen LE, Kildegaard HF. Site-specific integration in CHO cells mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 and homology-directed DNA repair pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep08572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Kildegaard HF, Lewis NE, Lee GM. Mitigating clonal variation in recombinant mammalian cell lines. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37:931–942. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu PT, MacHleidt T, Thyagarajan B, Fontes A, Frey E, Fuerstenau-Sharp M, Thompson DV, Swamilingiah GM, Derebail SS, Piper D, Chesnut JD. Generation of site-specific retargeting platform cell lines for drug discovery using phiC31 and R4 integrases. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:1207–1215. doi: 10.1177/1087057109348941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Z, Li Q, Zhao J, Wang P, Wang L, He H-P, Wang N, Zhou H, Zhang T-C, Luo X-G. Stable expression of infliximab in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated BAK1-deficient CHO cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2018;40:1209–1218. doi: 10.1007/s10529-018-2578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteil V, Eaton B, Postnikova E, Murphy M, Braunsfeld B, Crozier I, Kricek F, Niederhöfer J, Schwarzböck A, Breid H, Devignot S, Klingström J, Thålin C, Kellner MJ, Christ W, Havervall S, Mereiter S, Knapp S, Sanchez Jimenez A, Bugajska-Schretter A, Dohnal A, Ruf C, Gugenberger R, Hagelkruys A, Montserrat N, Kozieradzki I, Hasan Ali O, Stadlmann J, Holbrook MR, Schmaljohn C, Oostenbrink C, Shoemaker RH, Mirazimi A, Wirnsberger G, Penninger JM (2022) Clinical grade ACE2 as a universal agent to block SARS-CoV -2 variants . EMBO Mol Med 14. 10.15252/emmm.202115230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Monteil V, Kwon H, Prado P, Hagelkrüys A, Wimmer RA, Stahl M, Leopoldi A, Garreta E, Hurtado del Pozo C, Prosper F, Romero JP, Wirnsberger G, Zhang H, Slutsky AS, Conder R, Montserrat N, Mirazimi A, Penninger JM. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:905–913.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller M, Schaub J, Bernloehr C, Koenitzer J (2019) Integration sites in CHO cells

- Nakade S, Tsubota T, Sakane Y, Kume S, Sakamoto N, Obara M, Daimon T, Sezutsu H, Yamamoto T, Sakuma T, Suzuki KIT. Microhomology-mediated end-joining-dependent integration of donor DNA in cells and animals using TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9. Nat Commun. 2014;5:1–3. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CKD, Crawford YG, Shen A, Zhou M, Snedecor BR, Misaghi S, Gao AE (2021) Targeted integration of nucleic acids

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45–e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter H, Heller R. Transfection by electroporation. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2011;52:20–25. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb2005s52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourtabatabaei S, Ghanbari S, Damavandi N, Bayat E, Raigani M, Zeinali S, Davami F. Targeted integration into pseudo attP sites of CHO cells using CRISPR/Cas9. J Biotechnol. 2021;337:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2021.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pristovšek N, Nallapareddy S, Grav LM, Hefzi H, Lewis NE, Rugbjerg P, Hansen HG, Lee GM, Andersen MR, Kildegaard HF. Systematic evaluation of site-specific recombinant gene expression for programmable mammalian cell engineering. ACS Synth Biol. 2019;8:757–774. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J, Oumard A, Wegloehner W, Bode J. Novel tag-and-exchange (RMCE) strategies generate master cell clones with predictable and stable transgene expression properties. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:579–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers C, Ruijter JM, Lekanne Deprez RH, Moorman AFM. Assumption-free analysis of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) data. Neurosci Lett. 2003;339:62–66. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)01423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran F, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese NB, Ku S. Development of recombinase-based targeted integration systems for production of exogenous proteins using transposon-mediated landing pads. Curr Res Biotechnol. 2021;3:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.crbiot.2021.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Martins M, Cavalheiro GR, Matos-Rodrigues GE, Martins RAP. From gene targeting to genome editing: transgenic animals applications and beyond. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2015;87:1323–1348. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201520140710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma T, Nakade S, Sakane Y, Suzuki KIT, Yamamoto T. MMEJ-Assisted gene knock-in using TALENs and CRISPR-Cas9 with the PITCh systems. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:118–133. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma T, Takenaga M, Kawabe Y, Nakamura T, Kamihira M, Yamamoto T. Homologous recombination-independent large gene cassette knock-in in CHO cells using TALEN and MMEJ-directed donor plasmids. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:23849–23866. doi: 10.3390/ijms161023849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarcelli JJ, Shang TQ, Iskra T, Allen MJ, Zhang L. Strategic deployment of CHO expression platforms to deliver Pfizer’s monoclonal antibody portfolio. Biotechnol Prog. 2017;33:1463–1467. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster M, Loibner H, Janzek-Hawlat E, Peball B, Stranner S, Wagner B, Weik R (2010) ACE2 Polypeptide

- Schweickert PG, Cheng Z. Application of genetic engineering in biotherapeutics development. J Pharm Innov. 2020;15:232–254. doi: 10.1007/s12247-019-09411-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeeva D, Lee GM, Nielsen LK, Grav LM. Multicopy targeted integration for accelerated development of high-producing Chinese hamster ovary cells. ACS Synth Biol. 2020;9:2546–2561. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Kim SH, Lee JS, Lee GM. Streamlined human cell-based recombinase-mediated cassette exchange platform enables multigene expression for the production of therapeutic proteins. ACS Synth Biol. 2021;10:1715–1727. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.1c00113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SW, Lee JS. CHO cell line development and engineering via site-specific integration: challenges and opportunities. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2020;25:633–645. doi: 10.1007/s12257-020-0093-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shy BR, Macdougall MS, Clarke R, Merrill BJ. Co-incident insertion enables high efficiency genome engineering in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:7997–8010. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnikhina SA, Anuchina AA, Lavrov A V. (2019) Ways of improving precise knock-in by genome-editing technologies. Hum Genet 138. 10.1007/s00439-018-1953-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Srirangan K, Loignon M, Durocher Y. The use of site-specific recombination and cassette exchange technologies for monoclonal antibody production in Chinese Hamster ovary cells: retrospective analysis and future directions. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2020;40:833–851. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2020.1768043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuible M, van Lier F, Croughan MS, Durocher Y. Beyond preclinical research: production of CHO-derived biotherapeutics for toxicology and early-phase trials by transient gene expression or stable pools. Curr Opin Chem Eng. 2018;22:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2018.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tihanyi B, Nyitray L. Recent advances in CHO cell line development for recombinant protein production. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2021;1:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan S, Zehe C, Kuehle J, Qiao J, Bode J. Recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) - a rapidly-expanding toolbox for targeted genomic modifications. Gene. 2013;515:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Nagarajan H, Lewis NE, Pan S, Cai Z, Liu X, Chen W, Xie M, Wang W, Hammond S, Andersen MR, Neff N, Passarelli B, Koh W, Fan HC, Wang J, Gui Y, Lee KH, Betenbaugh MJ, Quake SR, Famili I, Palsson BO, Wang J. The genomic sequence of the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cell line. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:735–741. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Yang C, Tasan I, Zhao H. Expanding the potential of mammalian genome engineering via targeted DNA integration. ACS Synth Biol. 2021;10:429–446. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Wang J, Luo M, Luo H, Zhao M, Han L, Zhang M, Yang H, Xie Y, Jiang H, Feng L, Lu H, Zhu J. Rapid development of stable transgene CHO cell lines by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated site-specific integration into C12orf35. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:6105–6117. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Chen Y, Gong X, Jin J, Li H. Site-specific integration of light chain and heavy chain genes of antibody into CHO-K1 stable hot spot and detection of antibody and fusion protein expression level. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2019;0:1–7. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2019.1573196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].