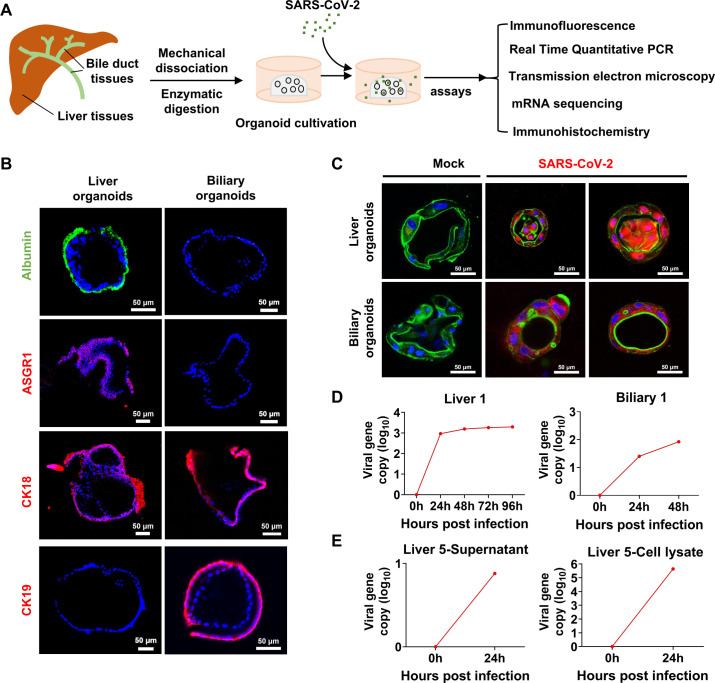

We have read with interest in a recent study published in Gut by Weber et al,1 reporting abnormal elevation of gamma-glutamyltransferase (37%) and total bilirubin (5%) in patients, that was associated with higher rates of COVID-19-related deaths. However, whether SARS-CoV-2 could infect human hepatocytes and cholangiocytes thus causing local damage has not been reported. Here, human organoids were used to investigate SARS-CoV-2 infection and its induced liver damage at cellular and molecular levels (figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Scheme of liver and biliary organoid culture establishment and performed assays. The liver and biliary organoids were generated from adjacent normal tissues of patients with liver cancer and coculture with SARS-CoV-2. (B) Differentiated liver and biliary organoids were immunostained using antibodies against human homologues to show albumin (green), ASGR1 (red), CK18 (red) and CK19 (red) protein, respectively. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) Immunofluorescent staining of SARS-CoV-2 infected liver organoids and biliary organoids at 24-hours. Virus are identified by SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein protein (red), nuclei and actin filaments are stained with DAPI (blue) and phalloidin (green), respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm. (D) Real time quantitative PCR analysis for viral sequences shows virus can productively replicate in the liver organoids at 0, 24, 48, 96 hours and in the biliary organoids at 0, 24, 48 hours after infection with SARS-CoV-2. (E) Live virus can be detected by RT-qPCR in supernatant and lysed organoids at 0 and 24 hours after infection with SARS-CoV-2.

We first established five lines of liver organoids and two lines of biliary organoids from adjacent normal tissues of seven patients with liver cancer (figure 1B; online supplemental figure 1A, B; online supplemental methods). We examined the susceptibility of human liver and biliary organoids to SARS-CoV-2 (Guangdong/20SF014/2020; EPI_ISL_403934; 19A) directly isolated from a patient with moderate COVID-19. The expression of SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein protein was readily detected in patchy areas of human liver and biliary organoids, but not in uninfected control by immunofluorescence staining (figure 1C; online supplemental figure 1C). Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 was dramatically increased in liver (liver 1 to liver 4) and biliary organoids (biliary 1 and biliary 2) at 24 hours postinfection with SARS-CoV-2, which remained stable for 96 hours in liver organoids and 48 hours in biliary organoids (figure 1D; online supplemental figure 2A; online supplemental table S1). Meanwhile, we found that live SARS-CoV-2 could amplify in lysed organoids (liver 5) and its culture supernatant (figure 1E; online supplemental table S1), inferring human liver and biliary organoids are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 and support robust viral replication.

gutjnl-2021-326617supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2021-326617supp004.pdf (91.9KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2021-326617supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2021-326617supp003.xlsx (139.3KB, xlsx)

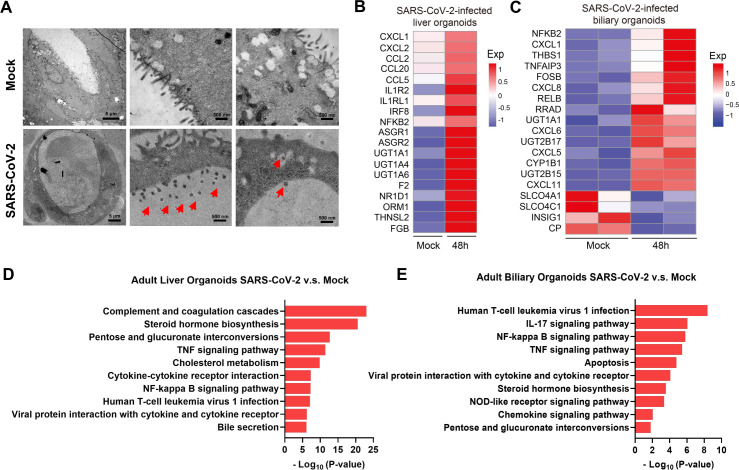

SARS-CoV-2 enters target cells mainly through the ACE2 receptor.2 Given that ACE2 receptor was more highly expressed in cholangiocytes (59.7%) than in hepatocytes (2.6%),3 we investigated the ultrastructure of SARS-CoV-2-infected biliary organoids under transmission electron microscopes (TEM) and found that viral particles were present in the lumen and at basolateral and apical sides of the organoid, as well as in membrane-bound vesicles (figure 2A). Therefore, TEM captured the critical location of SARS-CoV-2 in infected biliary organoids, indicating potential dissemination route of how SARS-CoV-2 enters the cholangiocytes.

Figure 2.

(A) Representative TEM imaging of biliary organoids at 0 and 24 hours of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. Coronaviruses were observed in the lumen of the organoid (arrows) and are found at the membrane-bound vesicles (arrows). Scale bar 500 nm to 5 µm. (B, C) Heatmaps depicting the 19 most significantly enriched genes related to viral infection and immune system on SARS-CoV-2 infection in liver and biliary organoids. Coloured bar represents the log2-transformed values. (D, E) KEGG orthology-based annotation system of differential gene expression profiles from SARS-CoV-2-infected liver and biliary organoids compared with mock infection. TEM, transmission electron microscope.

Gene expression changes induced by SARS-CoV-2-infection in liver and biliary organoids was identified by RNA sequencing. Heatmap and volcano plot of differentially expressed genes revealed robust induction of proinflammatory chemokines/cytokines including CXCL1 in SARS-CoV-2-infected liver and biliary organoids. Consistently, KEGG Orthology Based Annotation System revealed multiple upregulated proinflammatory pathways in infected organoids, including NF-κB signalling pathway etc. Of note, the significant upregulation of TNF signalling pathway and apoptosis pathway in infection group indicated that SARS-CoV-2 infection may induce cell death of hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. Besides, UGT1A1 was upregulated in liver and biliary SARS-CoV-2-infected organoids, which was associated with elevation of bilirubin. While, bile acid transporter gene SLCO4C1 was significantly decreased in SARS-CoV-2-infected biliary organoid, and the steroid hormone biosynthesis and bile secretion pathways were upregulated in SARS-CoV-2-infected organoids, which could cause bile acid accumulation. Moreover, the upregulation of IL1R2 and IL1RL1 could be associated with the albumin production inhibition, thereby impairing liver functions.4 It was reported an interacting host receptome of SARS-CoV-2 and demonstrated ASGR1 as alternative functional receptors, providing insight into SARS-CoV-2 tropism and pathogenesis.5 We found that ASGR1 was upregulated in infected liver organoids, which may explain that SARS-CoV-2 viral load was higher in liver organoids compared with biliary organoids, though expression of ACE2 receptor was upregulated in cholangiocytes than hepatocytes (figure 2B–E; online supplemental figure 2B; online supplemental table S1). Consistently, bilirubin levels were reported to be significantly higher in non-survivors than survivors with SARS-CoV-2 infection.1 6 Immunohistochemistry further validated the upregulated expressions of inflammatory factor CXCL8 and CXCL11 in SARS-CoV-2-infected biliary organoids compared with mock (online supplemental figure 2C).

In conclusion, SARS-CoV-2 can effectively infect human liver and biliary organoids. SARS-CoV-2 viruses are rapidly replicated in infected organoids to induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines, local hepatocytes and cholangiocytes damage and consequent bile acid accumulation, which may contribute to liver injury.

Footnotes

YZ, XR and JL contributed equally.

Contributors: YZ and XR performed experiments and drafted the manuscript. JL performed experiments and revised the manuscript. MinghuiH and MingleH performed bioinformatics analyses. ZL and LY performed experiments. MK collected human samples and commented on the study. HX and JJYS supervised and commented on the study. XL, LX and JY designed, supervised the study and revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82173191), Guangdong Science and Technology Program (2021B1212030007).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by The Institutional Ethics Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Weber S, Hellmuth JC, Scherer C, et al. Liver function test abnormalities at hospital admission are associated with severe course of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a prospective cohort study. Gut 2021;70:1925–32. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020;181:271–80. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chai X, Hu L, Zhang Y. Specific ACE2 expression in cholangiocytes may cause liver damage after 2019-nCoV infection. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gounden V, Vashisht R, Jialal I. Hypoalbuminemia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gu Y, Cao J, Zhang X, et al. Receptome profiling identifies KREMEN1 and ASGR1 as alternative functional receptors of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res 2022;32:24–37. 10.1038/s41422-021-00595-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jothimani D, Venugopal R, Abedin MF, et al. COVID-19 and the liver. J Hepatol 2020;73:1231–40. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2021-326617supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2021-326617supp004.pdf (91.9KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2021-326617supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2021-326617supp003.xlsx (139.3KB, xlsx)