Summary

Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) are a threat to public health and sustainable development. NCDs were equated to being a ‘pandemic’ before COVID-19 originated. Globally, NCDs caused approximately 74% of deaths (2019). India accounted for nearly 14.5% of these deaths. NCDs and COVID-19 have a lethal bi-directional relationship with both exacerbating each other's impact. Health systems and populations, particularly in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) like India have among the highest burden of COVID-19. This narrative review tracks key policy and programmatic developments on NCD prevention and control in India, with a focus on commercially-driven risk factors (tobacco and alcohol use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and air pollution), and the corresponding NCD targets. It identifies lacunae and recommends urgent policy-focussed multi-dimensional action, to ameliorate the dual impact of NCDs and COVID-19. India's comprehensive response to NCDs can steer national, regional and global progress towards time-bound NCD targets and NCD-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Funding

This work is supported by the Commonwealth Foundation. None of the authors were paid to write this article by a pharmaceutical company or other agency. The authors were not precluded from accessing data and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Keywords: Non-communicable diseases, COVID-19, NCD risk factors, Policy

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases and COVID-19: two lethal inter-connected pandemics

Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) impose a significant threat to public health and sustainable development, making it imperative to strengthen their prevention and management. NCDs exacerbate human suffering and inflict a lethal attack on socio-economic development and have been referred to as a ‘pandemic’ even before the origin of COVID-19.1 Worldwide, NCDs adversely affect people of all ages and income groups. Globally, NCDs caused approximately 74% of deaths (nearly 42 million), in 2019.2 India alone accounted for nearly 14.5% or nearly 4.1 million of these deaths.2 The increase in NCD deaths, from 2000 to 2014, has been the sharpest in the South-East Asia Region (SEAR),3 highlighted by a loss of more than 8.5 million lives, annually.4 Out of the total NCD-related deaths in SEAR, India contributed to the maximum proportion of deaths (66%), in 2019.2 In India, deaths attributable to NCDs increased from 36% to 65%, from 1990 to 2019.2 NCDs also hamper economic growth. It is estimated that India will lose $4.58 trillion before 2030 as a result of NCDs and mental health conditions.5 People Living with NCDs bear a heavy financial burden due to out of pocket expenditure for treatment, which goes up to approximately $342.6 Hospitalisation for treatment of NCDs forced 47% of the households to bear catastrophic health expenditure.6

India contributes significantly to the regional and global NCD burden, given its large demographics. Robust national NCD mitigation efforts are warranted to alleviate the burden, in SEAR, and Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). India is a widely heterogenous country due to the diverse socio-economic, geographical, and demographic profile of its population. Effective NCD prevention, and control strategies from India, that are tailored to a variety of local contexts, have the potential to inform global efforts to arrest the ‘silent pandemic' of NCDs, particularly in LMICs, which bear the burden of 77% of the global annual NCD mortality.7

Globally, health systems have been bearing the crippling burden of the COVID-19 pandemic, with NCD prevention and treatment services being negatively impacted. This disruption was predominant in LMICs, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) rapid assessment conducted in 163 countries.8 The COVID-19 pandemic has had widespread health impacts, revealing the vulnerability of people with underlying conditions. It was reported that in India 30% fewer acute cardiac emergencies reached health facilities in rural areas, in March 2020, compared to 2019. Another rapid assessment conducted in hospitals across India revealed that the pandemic severely affected NCD outpatient services, elective surgeries, population-based screening and prevention activities, in a majority of the facilities.9

India is among the countries with the highest number of COVID-19 cases and deaths. NCDs further exacerbate COVID-19, leading to more adverse health outcomes.10 In India, like other countries, COVID-19 morbidity and mortality are associated with higher burden of NCDs and risk factors.11, 12, 13 Common reported NCDs with poor prognosis in COVID-19 cases include, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), chronic kidney or liver disease and obesity.14 Even more alarming and unprecedented is the lethal bi-directional relationship between a communicable disease (COVID-19) and NCDs. While NCDs are major catalysts for severe disease and poor health outcomes, conversely COVID-19 is a trigger for chronic conditions such as diabetes or cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), developing in those without these diseases and even further exacerbating them among those already living with such NCDs.15,16 This data was also supported by the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) which stated that 75% of fatalities due to COVID-19 were among the elderly and those with co-morbidities and NCDs.17

In addition to physical health, the catastrophic nature of the pandemic also adversely impacted the mental health of populations, both among people with pre-existing conditions and those who experienced emotional and psychological turmoil.18 In 2022, the Government of India (GoI) announced the National Tele-Mental Health Programme, which will comprise of 23 tele-mental health centers of excellence to provide people of all ages with better access to quality mental health counseling and care services.19 However, the roll-out of this programme needs micro-planning and capacity building of key stakeholders.

The inter-connectedness between NCDs and COVID-19 underscores that policies linked to NCD prevention and control must be accorded urgent priority and secure commitment from multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder partners.

Mapping progress and synergising multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder action for NCD prevention and control in India

Even though substantial multi-pronged action has been undertaken by GoI and sub-national governments to curb NCDs, there is a need to map progress for accelerating and amplifying targeted multi-stakeholder efforts directed towards course-correction warranted by COVID-19. A narrative review was undertaken in 2020–2022, to track key policy and programmatic developments on NCD prevention and control in India. This assessment was guided by the NCD Alliance's benchmarking tool.20 Information was extracted from publicly accessible documents and publications, on broad thematic areas including: NCD morbidity and mortality, NCD surveillance, distribution of NCD risk factors and their mitigation through policy and programmatic interventions, and recommendations to strengthen NCD prevention and control in India. Resources reviewed included, GoI policy and programmatic documents, reports, guidelines, and legislation; WHO reports and publications, scientific literature, reports by Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and other relevant publications. These resources were thoroughly scanned to conduct this policy review. The synthesis of this review and recommendations for multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder action, are presented in this paper.

NCD risk factors in India

In literature, obesity, undernutrition, and climate change, have been referred to as three pandemics, representing The Global Syndemic that affects the NCD burden worldwide.21 India faces a paradoxical co-occurrence of underweight and overweight/obesity.22 It continues to carry a considerable burden of under-nutrition, with nutritional deficiencies causing about 0.5% of deaths,23 juxta positioned with altered living habits and commercialisation, contributing to the rising burden of overweight and obesity. As per the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016–2018, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents (10–19 years) was 5% and 1%, respectively.24 According to the National Family Health Survey-5, 24% of women and 22.9% of men in the age group of 15–49 years, are either overweight or obese.25 Air pollution resulted in 1.67 million deaths in 2019, accounting for 17.8% of the total deaths.26 Tobacco use accounts for over one million deaths every year and is projected to increase markedly over the coming years.27 About 5.4% of Alcohol Attributable Fraction - of all-cause mortality is contributed by alcohol use, with approximately 63% of all mortality attributed to liver cirrhosis due to alcohol use.28 Nearly 40% of adult Indians are reported to be physically inactive.29

COVID-19 lockdown increased NCD-risky behaviours in India

COVID-19 spreads across geographical borders, through aggressive biological transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The causative agents for NCDs are social, environmental, commercial and genetic.30 These include a complex set of non-modifiable and modifiable factors. Risk factors that are modifiable when supported by conducive policy environments and healthy behaviours include - tobacco use, alcohol use, unhealthy diet and physical inactivity. These risk factors are commercially transmitted through aggressive advertising and marketing of tobacco and alcohol products, and unhealthy foods and beverages. These risk factors along with air pollution, are exacerbated because of commercial interests and multiply trans-nationally.31 NCDs are manifested because of a complex inter-play of one or more risk factors. Exposure to these risk factors is amplified due to environmental (e.g., policies) and behavioural (e.g., lifestyle) determinants. Minimising exposure to these risk factors warrants comprehensive measures to curb the sale, marketing, and promotion of these products and evidence-based interventions to foster healthy norms at the individual, community, national, regional, and global levels.

With the rapid escalation in COVID-19 cases, emergency measures such as strict lockdowns were enforced to maintain physical distancing. Paradoxically, the lockdown manifested fertile conditions for the NCD-risky behaviours to surge via innovative advertising by the tobacco, alcohol, food and beverage industries, to exploit the public vulnerability.32,33 A clampdown on public places, educational institutions, and workplaces forced the population to remain indoors. The lack of access to exercise and home confinement resulted in increased sedentariness, unhealthy eating behaviours, and increased screen time for work, academic, and recreational purposes.34, 35, 36 Initial governmental directives prohibited sale of tobacco products and alcohol during the lockdown, but there were conflicting measures to increase access to alcohol through online sales, as a revenue generation strategy.37 A cross-sectional study conducted with 801 adult tobacco users revealed that those with access to tobacco products were 70% less likely to cease tobacco use compared to those who did not have access to tobacco products.38

NCD prevention and control in India

Through the National Action Plan and Monitoring Framework for the Prevention and Control of NCDs in India (2013),39 India was the first country to adopt the global NCD targets enshrined in the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs (2013–2020),40,41 to its national context. India's National Multi-sectoral Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Common NCDs (2017–2022) (NMAP), a follow-up to the Monitoring Framework, stipulates a roadmap to achieve the overall target of reducing premature NCD mortality by 25% by 2025.41

The NMAP is pivoted on a ‘Whole-of-Government' approach where all the sectors should consider health while developing policies and programmes. It also recommends a ‘Whole-of-Society' response to address NCDs effectively, underscoring that multiple stakeholders, including the Government, civil society, People Living with NCDs, youth, private sector, academia, donors, and media, must work in tandem. Several policies, programmes, communications, and reports have outlined GoI's efforts to integrate NCD prevention and control into the broader health and development agenda to achieve the 25x25 target42 and Goal 3.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to reduce premature NCD mortality by one-third by 2030.

Some of the key national NCD programmes include – National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Stroke; National Mental Health Programme; National Programme for Palliative Care; National Tobacco Control Programme; National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly, and; National Oral Health Programme.41 There are several challenges in the effective implementation of these programmes. Some of these include: limited human resource capacity of the healthcare workforce, insufficient budget allocation and utilisation, limited focus on health promotion, absence of a multi-sectoral approach, sub-optimal surveillance, monitoring and evaluation, inadequate health literacy, limited or tokenistic community and civil society engagement.43,44 There is also a need to shift from disease-specific vertical programmes to an integrated healthcare model for judicious utilisation of manpower and resources, tailored to the needs of the population, made evident by the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.45

GoI has prioritised addressing the burden of NCDs and strengthening the health system through primary healthcare under the National Health Protection Mission or Ayushman Bharat. Ayushman Bharat (means long live India) attempts to move from a selective approach to healthcare, to a comprehensive range of preventive, promotive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative care. Nearly, 1,18,314 Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) have been established with a focus on wellness and the delivery of an expanded range of services, closer to the community, including screening for NCDs, health promotion and wellness interventions.46

The inter-linkages and complexities of NCDs and development demands 360-degree action. It is imperative to track the trajectory which traces intent, action, and inaction towards the NCD targets and SDGs. This is particularly critical at this crucial juncture, amidst the crippling COVID-19 pandemic, that has compelled several key stakeholders to recalibrate their commitment and action towards buoyant public health systems that are sufficiently equipped to provide comprehensive support through the care continuum, from primordial prevention, across primary, secondary, tertiary services, and palliative care. As India strives to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic and further strengthen its public health policies and healthcare infrastructure, scaling-up NCD prevention and control is akin to public health emergency mitigation strategies, now and in the future.

Surveillance mechanisms for tracking the NCD targets, indicators, and risk factors

The National NCD Monitoring Survey (NNMS)47 assesses national NCD targets and indicators. 2010 served as a baseline for assessing the progress made for achieving the NCD targets in 2015, 2020, and 2025. This survey provided information on the prevalence of NCD risk factors in the Indian population. The results of the survey covering 10,659 adults showed that the prevalence of tobacco and alcohol use was 32.8% and 15.9%, respectively. Overall, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among the adults was 26.1% and 6.2%, respectively, and more than one-third of adults (41.3%) were physically inactive. 28.5% were with raised blood pressure, and 9.3% with raised blood glucose levels. The proportion of adults (40–69 years) who had a ten-year CVD risk of >30% or with existing CVD was, 12.8%.47 The findings highlighted the presence of NCD risk factors in high proportions among adults and the dire need for fast tracking their mitigation if India has to meet its NCD targets and NCD-related SDGs.

Policies and programmes addressing NCD risk factors

Advancing risk factor alleviation demands substantial scaling-up of cost-effective interventions, including the WHO Best Buys.48 Current updates on actions to curb the five major NCD risk factors in the Indian context are summarised. While each of these are distinct, they are all commercially driven, and strategies to control them are largely synergistic. Table 1 contextualises the status of NCD risk factors in India with selected national NCD targets. Table 2 provides further granularity on recommended actions by key Government and non-government players, in order to progress towards the national NCD targets.

Table 1.

National NCD targets and five key risk factors from an Indian context (selected).

| Risk factor | National NCD target by 2025 | Current considerations in Indian context |

|---|---|---|

| Premature mortality from NCDs | 25% relative reduction in overall mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, or chronic respiratory disease |

|

| Tobacco use | 30% relative reduction in current tobacco use |

|

| Alcohol use | 10% relative reduction in alcohol use |

|

| Salt/sodium intake (Unhealthy diet) | 30% relative reduction in mean population salt intake |

|

| Physical inactivity | 10% relative reduction in prevalence of insufficient physical activity |

|

| Household indoor air pollution | 50% relative reduction in household use of solid fuels as a primary source of energy for cooking |

|

Table 2.

Recommendations for accelerating integrated multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder action towards India's NCD targets.

| Stakeholder | Recommendations for action |

|---|---|

| Government The concept of ‘Health-in-all-Policies' should be the guiding principle to avoid conflict in governmental policies, across ministries, particularly in regulating commercially driven risk factors. | |

| Ministry of Health and Family Welfare |

|

| Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change |

|

| Department of Revenue (Ministry of Finance) |

|

| Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment |

|

| Department of School Education and Literacy (Ministry of Education) |

|

| Ministry of Information and Broadcasting |

|

| Ministry of Commerce and Industry |

|

| |

| Researchers |

|

| Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) |

|

| People Living with NCDs |

|

| Youth |

|

Tobacco use

Substantial progress has been made to regulate multiple forms of smoking and smokeless tobacco products, including enforcement of the Indian Tobacco Control Law49 and a nationwide ban on electronic cigarettes.50,51 The Global Adult Tobacco Survey - GATS 2 (2016–17) revealed a relative reduction of 17% in current tobacco use, since GATS 1 (2009–10).52 The prevalence of tobacco use among minors (15–17 years) has also decreased from 10% in GATS 1 to 4% in GATS 2, with a relative reduction of 54%.52 This reduction in tobacco use can be attributed to comprehensive tobacco control action by multiple Government and non-government stakeholders. A uniform pan-India tobacco control legislation (COTPA), a dedicated National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP)53 and commitment to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC)54 are some of the major components of India's progress in tobacco control. However, observing the challenges being faced by COTPA enforcement agencies and the widespread propaganda by the tobacco industry to lure customers, there are several policy interventions that are urgently required. Some of these include: the need for dedicated strategies targeted at smokeless tobacco use reduction, strengthening the outreach of tobacco cessation services, a national policy to check Tobacco Industry Interference (TII), under Article 5.3 of WHO FCTC.55 Instances of TII are rampant in India and pose one of the most significant threats to tobacco control efforts. The level of implementation of Article 5.3 in India was assessed annually from 2018 to 2021 through a TII Index. While India's rating improved from 72 in 2018 to 57 in 2021 (a lower score indicating better compliance), TII continues to be a serious threat to tobacco control.56, 57, 58, 59 Under the ambit of COTPA, some of the key lacunae that need urgent intervention include: removal of designated smoking areas; prohibiting online marketing and promotion of tobacco products and regulating depiction of tobacco imagery on online streaming platforms. MoHFW has introduced the COTPA Amendment Bill 2022, which addresses some of these gaps, however, the legislative process for this is ongoing.60

Alcohol use

India's NCD targets aimed beyond the global targets by committing to reduce alcohol use and not just the harmful use of alcohol. In India, alcohol control policies are heterogenous, varying from state to state. While five jurisdictions have imposed a ban on alcohol,61 in the absence of a national policy or legislation, these measures are partial. The introduction of a National Alcohol Control Policy needs to be expedited. Key priority areas include restrictions on advertisements, promotion, and sponsorship; ban on drinking in public places; restrictions on opening of liquor shops at certain locations; regulating availability through restrictions on time and place of sales; prescribing a unform Minimum Legal Drinking Age (MLDA); depiction of health warnings on alcohol bottles, and; levying excise duty on alcohol.

Unhealthy diet

The National Nutrition Strategy (2017) acknowledges the dual burden of NCDs and infectious diseases. One of its goals is congruent to a national NCD target and calls for no increase in childhood obesity. The Strategy focuses on nutrition education to ensure optimal feeding and caring practices, dietary diversity in nutritious foods; sanitation and hygiene, and that healthy lifestyles are promoted, addressing undernutrition and the dual burden of malnutrition.62 The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) had developed Guidelines for Making Available Wholesome, Nutritious, Safe, and Hygienic Food to School Children in India (2015). In 2020, FSSAI notified, Food Safety and Standards (safe food and balanced diet for children in school) Regulation, to ensure the availability, and promotion of safe food and balanced diet in and around the school campus.63 Over the last several years, a steep rise has been observed in the consumption of ultra-processed foods, high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS), in India, resulting in an increase in prevalence of overweight and obesity and related NCDs. Policies to curb the consumption of HFSS foods have been inadequate and fragmented. India's first Food Safety and Standards (Labelling and Display) Regulations (2018)64 will require front-of-pack warning labels for foods high in sodium, sugar, and fat. There is a need to accelerate the evidence-based finalisation and enforcement of these regulations, pan-India. Industry-dependent self-regulations related to marketing of ultra-processed and HFSS foods and Sugar Sweetened Beverages (SSBs) in India are largely voluntary without any enforcement mechanisms, rendering them largely ineffective and untenable. FSSAI, the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), and the Ministry of Women and Child Development are encouraging several initiatives including the Eat Right Movement,65 to urge people to reduce their salt, sugar, and fat intake. However, these voluntary measures can only yield limited success, devoid of any legislative framework. The national NCD targets include a target on reducing intake of salt/sodium. The absence of any NCD targets to reduce fat and sugar consumption is an impediment to advance policy action.

Physical inactivity

In 2019, India launched the Fit India Movement, under the aegis of the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports,66 which has developed Fitness Protocols and Guidelines for population aged 5 to 65+ years.67, 68, 69 CBSE was advised to reserve one period every day for health and physical education, for mainstreaming health and physical education in schools.70 The School Health and Wellness Curriculum of Ayushman Bharat includes the promotion of a healthy lifestyle, and the prevention and management of substance misuse.71 However, policy and programmatic actions have been limited, based on promoting physical activity in educational institutions, workplaces, and Resident Welfare Associations, including the promotion of active transport usage. It is essential to administer evidence-based public health interventions, build dedicated infrastructure and capacity and, target high-risk populations, anchored by a robust National Multi-sectoral Physical Activity Policy.29

Air pollution

The existing National Air Quality Monitoring Programme under Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) monitors the status and trends of ambient air quality across the country.72 The National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) aims to tackle air pollution. Targets are set to achieve 20%–30% reduction in Particulate Matter concentrations by 2024.73 The National Programme for Climate Change and Human Health (NPCCHH)74 under the National Health Mission (NHM) aims to create general awareness among vulnerable communities like children, women and marginalised populations along with the health care providers, and policy makers. The political declaration of the Third United Nations High-Level Meeting (2018) recognised air pollution (indoor and ambient/outdoor) air pollution as a risk factor for NCDs.75 Prior to that, India had already included a target on household indoor air pollution as a part of the national NCD targets. However, till date, ambient/outdoor air pollution is not included as a part of the national target. Since air pollution has only been recently documented as a risk factor for NCDs, the narrative on addressing it as a health or NCDs issue is limited with insufficient buy-in from the NCD and public health community. This is an area where multi-sectoral engagement needs to be substantially scaled-up towards a common national action agenda.

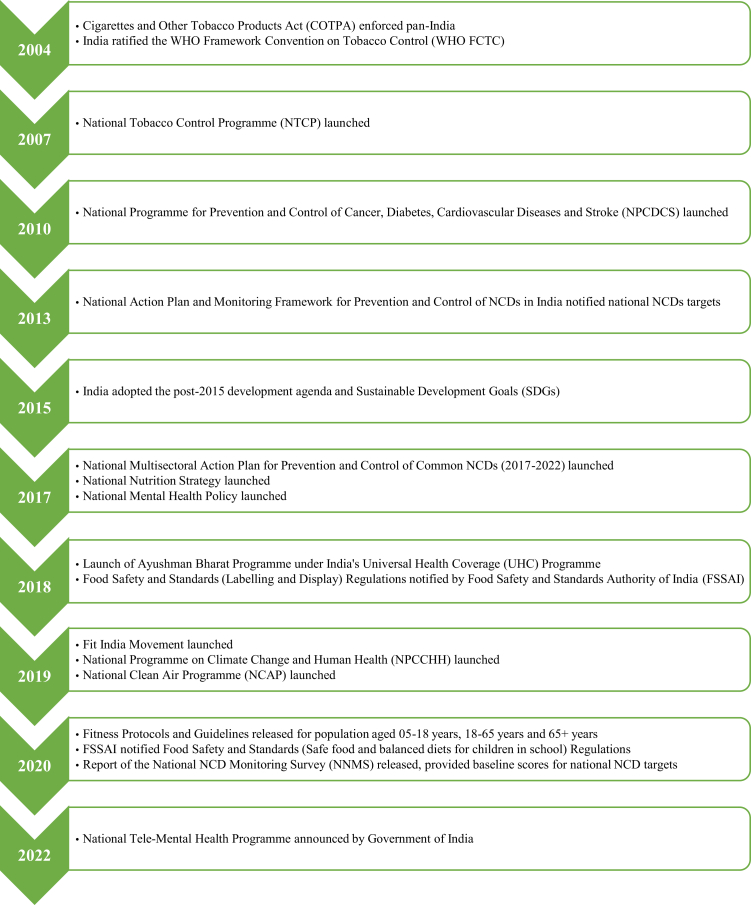

Fig. 1 provides a timeline for key NCD policies and programmes in India.

Fig. 1.

Key NCDpolicies andprogrammes in India–Atimeline.

Recommendations for multi-pronged action to accelerate towards India's NCD targets

The NMAP provides a blueprint to streamline multi-pronged NCD action. While it offers a pathway for increased integrated action across domains and partners, its operationalisation, particularly at the sub-national level, needs strengthening. Through a ‘Whole-of-Government' approach, the NMAP defines the role of key government ministries. It also briefly alludes to role of civil society. Civil society stakeholders like the Healthy India Alliance76 can steer the adoption of concrete guidelines for meaningful stakeholder engagement, across the country. CSOs, People Living with NCDs, and youth must be provided agency as important constituencies for a comprehensive response to strengthen NCD prevention and control.

Table 2 provides recommendations for multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder actions for key government and non-government players towards selected national NCD targets presented in Table 1. The strategies provided in the NMAP, and the items listed in Table 2 also warrant careful planning and earmarking of human, technical, and financial resources. Capacity building of the frontline workforce; CSOs; youth-led groups, and People Living with NCDs are important for the robust planning, implementation and monitoring of these recommended actions.

Conclusion

This policy analysis highlights the strengths and voids in India’s policy response to the crippling load of NCDs that contributes significantly to the global and SEAR burden of this public health catastrophe. It emphasises that COVID-19 has provided a reality check on the importance of effective prevention and management of chronic co-morbidities. The two-way link established between NCDs and COVID-19 has made it evident that the stress and strain of the pandemic on the preventive and curative arms of the health system, has further exacerbated the NCD burden in immeasurable proportions. Fresh NCD cases have been diagnosed as a by-product of COVID-19 infection and simultaneously, serious prognosis for existing COVID-19 + NCD cases, is rampant. This deadly inter-play has impacted the most vulnerable sections of the population.

The COVID-19 pandemic was not in the equation while setting NCD targets for 2025 or the SDGs for 2030. The healthcare and public health infrastructure has been jolted by COVID-19 with a threat of delaying and diluting progress. NCD treatment regimens and services took an unwarranted blow due to unprecedented lockdowns and lifestyle patterns shifted radically, akin to increased NCD risk. It is important to address deficiencies in the policy framework to shield the population, particularly children, adolescents, and young adults, from commercially-driven NCD risk factors (tobacco use, alcohol use, unhealthy diets – including HFSS foods and SSBs), inadequate physical activity and air pollution. Most LMICs, including India, are off track to reach SDG target 3.4 for NCD mortality and consequently, the NCD targets.77,78 The NMAP is due for renewal in 2023. The WHO Noncommunicable Disease Progress Monitor (2022) has highlighted areas to scale-up action to effectively address NCDs in India.79 Rebuilding a resilient and comprehensive strategy for recalibrating and advancing NCD policies and programmes, in India, is essential for erecting a strong public health defence against current and future epidemics and pandemics.

The drafting of the next phase of NMAP (from 2023) should be informed by multi-stakeholder consultation. It should encompass, increased investments for NCDs to establish well-equipped systems and workforce that target continuum of NCD care, from primary prevention to palliative care. It should also focus on establishing a robust bottoms-up and top-down stakeholder engagement plan, that ensures meaningful community and civil society involvement, guided by a transparent and independent accountability mechanism, to safeguard NCD policies from vested commercial interests. This is essential for effectively mitigating the enduring impact of pandemics like COVID-19 and NCDs, at large.

Blunting the potential long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in worsening NCD risk and burden, across the globe, critically warrants that India should step-up domestic action towards a concrete, resilient and well-resourced health system, supported by an evidence-based and robustly enforced policy framework. Escalation of such multi-dimensional NCD action in India can foster adaptation of best practices and evidence to create a sustained ripple effect, beyond its territory. This will substantially reduce the manifold and tragic impact of NCDs, and lead India, SEAR and the globe, particularly LMICs, towards the NCD targets and SDGs. COVID-19 is a dangerous warning to urgently plug policy and systemic gaps with a clear roadmap to march full throttle towards recommended actions. The receding pandemic should not be misconstrued as an opportunity to snooze the alarm. The next wake-up call might just be round the corner.

Contributors

RS and MA conceptualised this analysis and led its development and finalisation. RS conducted the narrative review and developed the manuscript. TR, RM, IK, and SB provided critical inputs for finalisation of the technical content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Commonwealth Foundation. The authors thank Dr Mansi Chopra and Dr Barsa Priyadarshini Rout for their contribution towards this manuscript.

References

- 1.Allen L. Are we facing a noncommunicable disease pandemic? J Epidemiol Glob Health [Internet] 2017;7(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2016.11.001. [cited 2022 May 11]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IHME Viz Hub; 2022. GBD Compare.https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Status Report on noncommunicable diseases 2014 “Attaining the nine global noncommunicable diseases targets; a shared responsibility.”. 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/148114/9789241564854_eng.pdf [cited 2022 May 11]; Available from:

- 4.Noncommunicable diseases in SEARO [Internet] 2022. https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases [cited 2022 May 11]. Available from:

- 5.Economics of Non-Communicable Diseases in India World Econ Forum [Internet] 2014. www.weforum.orgseehttp://www.weforum.org/issues/healthy-living [cited 2022 May 13]. Available from:

- 6.Menon G.R., Yadav J., John D. Burden of non-communicable diseases and its associated economic costs in India. Soc Sci Humanit Open [Internet] 2022;5(1):100256. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ [cited 2022 May 13]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Non communicable diseases. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases [Internet] [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from:

- 8.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2020. Results of a rapid assessment [Internet] pp. 1–32.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ncds-covid-rapid-assessment Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nath A., Sudarshan K.L., Rajput G.K., Mathew S., Chandrika K.R.R., Mathur P. A rapid assessment of the impact of coronavirus disease (COVID- 19) pandemic on health care & service delivery for noncommunicable diseases in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev [Internet] 2022;16(10):102607. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102607. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1871402122002211 [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikoloski Z., Alqunaibet A.M., Alfawaz R.A., et al. Covid-19 and non-communicable diseases: evidence from a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2021;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11116-w. https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11116-w [cited 2022 May 11]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaur K., Khedar R.S., Mangal K., Sharma A.K., Dhamija R.K., Gupta R. Macrolevel association of COVID-19 with non-communicable disease risk factors in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2021;15(1):343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pal R., Bhadada S.K. COVID-19 and non-communicable diseases. Postgrad Med J [Internet] 2020;96(1137):429–430. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137742. https://pmj.bmj.com/content/96/1137/429 [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suva M.A., Suvarna V.R., Mohan V. Impact of COVID-19 on noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) J Diabetol [Internet] 2021;12(3):252. https://www.journalofdiabetology.org/article.asp?issn=2078-7685;year=2021;volume=12;issue=3;spage=252;epage=256;aulast=Suva [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi S. Indian COVID-19 risk score, comorbidities and mortality clinical studies in sexual medicine view project SITE-screening India's twin epidemic view project. Artic J Assoc Physicians India [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1016/j. [cited 2022 Oct 10] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narain J.P. COVID-19 and chronic noncommunicable diseases: profiling a deadly relationship. Int J Noncommun Dis [Internet] 2020;5(2):25. https://www.ijncd.org/article.asp?issn=2468-8827;year=2020;volume=5;issue=2;spage=25;epage=28;aulast=Narain [cited 2022 Oct 10] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evolving COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Why addressing chronic diseases today is even more critical. Med [Internet] 2021;6(2):1–3. http://medical.advancedresearchpublications.com/index.php/EpidemInternational/article/view/609 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 17.Indian Council of Medical Research Pandemic management to continue along with work on other diseases. 2021. https://www.icmr.gov.in/pdf/press_realease_files/Newsletter_English_July_2021.pdf from.

- 18.Roy A., Singh A.K., Mishra S., Chinnadurai A., Mitra A., Bakshi O. Mental health implications of COVID-19 pandemic and its response in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry [Internet] 2021;67(5):587. doi: 10.1177/0020764020950769. /pmc/articles/PMC7468668/ [cited 2022 May 11] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaul R. Budget 2022: Sitharaman announces 24x7 free tele counselling for mental health–Hindustan Times [Internet] 2022. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/union-budget-2022-sitharaman-announces-24x7-free-counselling-for-mental-health-101643741447764.html [cited 2022 May 13]. Available from:

- 20.NCD Alliance Benchmarking tool | NCD alliance [Internet] 2022. https://ncdalliance.org/what-we-do/global-accountability/benchmarking-tool [cited 2022 Apr 1]. Available from:

- 21.Swinburn B.A., Kraak V.I., Allender S., et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791–846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gopalan C. The changing nutrition scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138(3):392–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Indian Council of Medical Research, Public Health Foundation of India, for Health Metrics I Evaluation. India: Health of the Nation’s States–The India State–Level Disease Burden Initiative. [Internet] 2017. http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/2017%7B%5C_%7DIndia%7B%5C_%7DState-Level%7B%5C_%7DDisease%7B%5C_%7DBurden%7B%5C_%7DInitiative%7B%5C_%7D-%7B%5C_%7DFull%7B%5C_%7DReport%7B%5C%25%7D5B1%7B%5C%25%7D5D.pdf [cited 2020 Jun 26]. Available from:

- 24.Comprehensive national nutrition survey. 2016. https://nhm.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/1405796031571201348.pdf [cited 2022 Mar 31]; Available from:

- 25.National Family Health Survey-5. 2022. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5_FCTS/India.pdf [cited 2022 Mar 31]; Available from:

- 26.Pandey A., Brauer M., Cropper M.L., et al. Health and economic impact of air pollution in the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Planet Heal [Internet] 2021;5(1):e25–e38. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30298-9. https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S2542519620302989?token=F4D3ED0EEEA18C340FE556FE8E2982A5028DB71895439060B238235A35069424ED6232881BCDCB20005500F415C271E1&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20211118101701 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization Factsheet 2018 India [Internet] 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272672/wntd_2018_india_fs.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [cited 2020 Jun 26]. Available from:

- 28.WHO Global status report on alcohol and health. 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639 [Internet]. Available from:

- 29.Ramamoorthy T., Kulothungan V., Mathur P. Prevalence and correlates of insufficient physical activity among adults aged 18–69 Years in India: findings from the national noncommunicable disease monitoring survey. J Phys Act Heal [Internet] 2022;19(3):150–159. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2021-0688. https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/jpah/19/3/article-p150.xml [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization Invisible numbers [Internet] 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/invisible-numbers [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from:

- 31.Whitaker K., Webb D., Linou N. Commercial influence in control of non-communicable diseases. BMJ [Internet] 2018;360:k110. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k110. https://www.bmj.com/content/360/bmj.k110 [cited 2022 May 11]. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Policy response to alcohol consumption and tobacco use during the COVID-19 pandemic in the WHO South-East Asia Region: preparedness for future pandemic events [Internet] 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/363123?show=full [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from:

- 33.Collin J., Leppold C., Barry R., Dain K., Renshaw N. 2020. Signalling virtue, promoting harm acknowledgements. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chopra S., Ranjan P., Singh V., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on lifestyle-related behaviours- a cross-sectional audit of responses from nine hundred and ninety-five participants from India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev [Internet] 2020;14(6):2021–2030. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.034. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33099144/ [cited 2022 Apr 1]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta P., Sachdev H.S. The escalating health threats from ultra-processed and high fat, salt, and sugar foods: urgent need for tailoring policy. Indian Pediatr [Internet] 2022;59(3):193. doi: 10.1007/s13312-022-2463-z. pmc/articles/PMC8964373/ [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khandelwal S. In: Health dimensions of COVID-19 in India and beyond. Pachauri S., Pachauri A., editors. 2022. Health dimensions of COVID-19 in India and beyond. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arora M., Aneja K. Online sale of liquor could dilute India's efforts to contain spread of coronavirus. Wire [Internet] 2020:1–10. https://thewire.in/government/liquor-sale-alcohol-coronavirus Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arora M., Nazar G.P., Sharma N., et al. COVID-19 and tobacco cessation: lessons from India. Public Health [Internet] 2022;202:93. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.11.010. /pmc/articles/PMC8633921/ [cited 2022 Apr 1]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India . National action plan and monitoring framework for prevention andcontrol of NCDs. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathur P., Kulothungan V., Leburu S., et al. Baseline risk factor prevalence among adolescents aged 15-17 years old: findings from National Non-communicable Disease Monitoring Survey (NNMS) of India. BMJ Open [Internet] 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044066. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) Government of India National multisectoral action plan for prevention and control of common noncommunicable diseases [Internet] 2018. https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/National Multisectoral Action Plan %28NMAP%29 for Prevention and Control of Common NCDs %282017-22%29_1.pdf Available from:

- 42.Nations U . Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2022. Goal 3.https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3 [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 13]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thakur J.S., Paika R., Singh S. Burden of noncommunicable diseases and implementation challenges of National NCD Programmes in India. Med J Armed Forces India [Internet] 2020;76:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nath A., Shalini M., Mathur P. Health systems challenges and opportunities in tackling non-communicable diseases in rural areas of India. Natl Med J India [Internet] 2021;34(1):29. doi: 10.4103/0970-258X.323661. https://nmji.in/health-systems-challenges-and-opportunities-in-tackling-non-communicable-diseases-in-rural-areas-of-india/ [cited 2022 Oct 10] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar R. Health policy: a National Interest Protecting national interest through public health policy-Why does India need to shift from selective primary health care (disease focused vertical programs) to a comprehensive health care model; lessons from COVID 19. 2021. www.jfmpc.com Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) Government of India Official Website Ayushman Bharat | HWC [Internet] 2022. http://ab-hwc.nhp.gov.in/ [cited 2022 May 13]. Available from:

- 47.Mathur P., Kulothungan V., Leburu S., et al. National noncommunicable disease monitoring survey (NNMS) in India: estimating risk factor prevalence in adult population. PLoS One [Internet] 2021;16(3):e0246712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246712. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0246712 [cited 2022 Apr 1] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO Tackling NCDs: “best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases [Internet] 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259232 [cited 2022 May 13]. Available from:

- 49.Justice M of L and. The Gazette of India Extraordinary. 2022. https://ntcp.nhp.gov.in/assets/document/Acts-Rules-Regulations/COTPA-2003-English-Version.pdf [cited 2022 May 13]; Available from:

- 50.Prohibition of electronic cigarettes (production, manufacture, import, export, transport, sale, distribution, storage and advertisement) act. 2019. http://indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/13078 [cited 2022 Oct 10]; Available from:

- 51.Ministry of Law and Justice The prohibition of electronic cigarettes (production, manufacture, import, export, transport, sale, distribution, storage and advertisement) act. 2019. https://ntcp.nhp.gov.in/assets/document/The-Prohibition-of-Electronic-Cigarettes-Production-Manufacture-Import-Export-Transport-Sale-Distribution-Storage-and-Advertisement)-Act-2019.pdf (Dl):1–5. Available from:

- 52.Global Adult Tobacco Survey-2 [Internet] Ministry of health and family Welfare,Tata Institute of Social Sciences. 2017. https://www.tiss.edu/view/11/research-projects/global-adult-tobacco-survey-round-2-for-india-2016/ Available from.

- 53.National Tobacco Control Programme [Internet] 2022. https://ntcp.nhp.gov.in/ [cited 2022 May 13]. Available from:

- 54.WHO WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control [Internet] 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42811/9241591013.pdf?sequence=1 [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from:

- 55.WHO Guidelines for implementation of Article 5.3 [Internet] 2020. https://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/article%7B%5C_%7D5%7B%5C_%7D3/en/ [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from:

- 56.Tobacco industry interference index, India 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 57.India Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2019. 2019. https://globaltobaccoindex.org/upload/assets/Er8klWfdERBxBGMyoU6sQ3gkoe56pGh2wrYE36IlMRXCFBxZ5Q.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tobacco industry interference index 2020. 2020. https://globaltobaccoindex.org/upload/assets/3Z3etsFtAPNhMM3sovQgfULM4uTjafVS7mLvQe2He5CHQOmy49.pdf Available from:

- 59.Tobacco industry interference index, India. 2021. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/searo/india/tobacoo/economic-burden-of-tobacco-related-diseases-in-india- [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from:

- 60.The Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products(Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce) 2022. https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A2003-34.pdf [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from:

- 61.NDDTC, All India institute of medical sciences (AIIMS) ND Magnitude of substance use in India. 2019. https://www.ndusindia.in/downloads/Magnitude_India_EXEUCTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf [cited 2022 May 13]. Available from:

- 62.NITI Aayog G Nourishing India. National Nutrition Strategy [Internet] 2020. https://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document%7B%5C_%7Dpublication/Nutrition%7B%5C_%7DStrategy%7B%5C_%7DBooklet.pdf [cited 2020 Jun 27]. Available from:

- 63.Food Safety and Standards Authority of India Food Safety andStandards (Safe food and balanced diets for children in school) Regulations. https://fssai.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/Gazette_Notification_Safe_Food_Children_07_09_2020.pdf 2020;(1):1–9. Available from:

- 64.Food Safety and Standards Authority of India, Drafts regulations on safe and wholesome Food for School Children [Internet] 2018. https://foodsafetyhelpline.com/fssai-drafts-regulations-safe-wholesome-food-school-children/ Available from:

- 65.Food Safety and Standards Authority of India Eat Right India [Internet] 2020. https://fssai.gov.in/EatRightMovement/foodbusinesses.jsp [cited 2020 Jun 27]. Available from:

- 66.FIT India Movement [Internet] 2020. http://fitindia.gov.in/ [cited 2020 Jun 27]. Available from:

- 67.Ministry of Youth and Sports Affairs, Government of India. Fitness protocols and guidelines for 5-18 years. [cited 2022 May 13] 2022. https://fitindia.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/doc/Fitness%20Protocols%20for%20Age%2005-18%20Years%20v1%20(English).pdf Available from:

- 68.Ministry of Youth and Sports Affairs, Government of India Fitness Protocols and guidelines for 18+ to 65 years. 2022. https://yas.nic.in/sites/default/files/Fitness Protocols for Age 18-65 Years v1 (English).pdf [cited 2022 May 13]; Available from:

- 69.Ministry of Youth and Sports Affairs Government of India. Fitness protocols and guidelines for 65+ years. [cited 2022 May 13] 2022. https://fitindia.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/doc/Fitness%20Protocols%20for%20Age%2065%20Years%20v1%20(English).pdf Available from:

- 70.Report of health and physical education (HPE), central board of secondary education. 2018. http://cbseacademic.nic.in/web_material/Circulars/2018/36_Circular_2018.pdf Available from:

- 71.Operational guidelines on school health programme under ayushman Bharat health and wellness ambassadors partnering to build a stronger future. 2018. https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/RMNCHA/AH/guidelines/Operational_guidelines_on_School_Health_Programme_under_Ayushman_Bharat.pdf Available from:

- 72.CPCB Central Pollution Control Board [Internet] 2021. https://cpcb.nic.in/monitoring-network-3/ [cited 2021 Dec 15]. Available from:

- 73.National Clean Air Programme. Press Inf Bur GoI [Internet] 2019:1–8. https://pib/.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1655203 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 74.National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC); 2022. National programme on climate change & human health (NPCCHH)https://ncdc.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1&sublinkid=876&lid=660 [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 14]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 75.(2018-2019) UGA (73rd sess. :, York) UGAH-LM of H of S and G on the P and C of N-CD (2018 : N. Political declaration of the 3rd High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases [Internet]. UN. 2018. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1648984 [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from:

- 76.Healthy India alliance [Internet] 2020. http://healthyindiaalliance.org/ [cited 2020 Sep. 1]. Available from:

- 77.Watkins D.A., Msemburi W.T., Pickersgill S.J., et al. NCD Countdown 2030: efficient pathways and strategic investments to accelerate progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4 in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet [Internet] 2022;399(10331):1266–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02347-3. http://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140673621023473/fulltext [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Singh Thakur J., Nangia R., Singh S. Progress and challenges in achieving noncommunicable diseases targets for the sustainable development goals [Internet] FASEB Bioadv. 2021;3:563–568. doi: 10.1096/fba.2020-00117. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8332469/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.World Health Organization Noncommunicable diseases progress monitor 2022 [Internet] 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240047761 [cited 2022 Jun 16]. Available from: