Abstract

Mood disturbances such as anxiety and depression are common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and impact negatively on their quality of life and disease course. An integrated multidisciplinary IBD team, which includes access to psychology and psychiatry opinion, makes possible the prompt recognition and management of psychological disturbance in patients with IBD. Based on our experience and existing literature, including systematic reviews of the effectiveness of available treatment modalities, a stepwise approach to the maintenance and restoration of psychological well-being is recommended, evolving upwards from lifestyle advice, through behavioural therapies to pharmacotherapy.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, psychological stress

What is already known on this subject

Mental disorders such as anxiety and depression are very common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but IBD clinicians often lack confidence in their management.

Psychological membership of the IBD multidisciplinary team (MDT) is mandated by the UK IBD Standards but many services do not yet meet this target.

Of the available psychological therapies, cognitive behavioural treatment has the strongest evidence base for efficacy in IBD.

What this study adds

This guide provides a stepwise approach to psychological care in patients with IBD which all members of the MDT can use.

An overview of the management options for optimising mental well-being in IBD is given, ranging from lifestyle measures to a combination of psychological therapy and antidepressants.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

Patients with anxiety or depression, depending on its severity, can be offered psychological therapy and/or started on an antidepressant by the IBD clinician alongside referral to psychiatry, if appropriate.

This practical guide will help all members of the IBD MDT provide holistic care and improve psychological wellbeing in patients with IBD.

Introduction

Psychological stress and mood disorders are common in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1 2 In recent surveys, people with IBD have reported that they want more attention paid to their emotional needs.3–5 In busy gastroenterology clinics, however, psychological needs may be overlooked, and the negative impact of stress or low mood on the quality of life (QOL) and course of patients’ IBD underestimated. Furthermore, the gastroenterology care team may lack the necessary training and confidence to assess and treat patients suffering from psychological distress, anxiety and depression (definitions in table 1).

Table 1.

Plain English explanations of psychological disorders and psychological therapies

| Psychological disorder | Explanation |

| (Psychological) stress | State of emotional turmoil in response to a real or perceived stimulus. Most people experience stress when what they perceive they ‘must do’ exceeds their perception of their ability to do it. |

| Anxiety | State of apprehension or unease driven by fear (eg, of disease, death). https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/feelings-symptoms-behaviours/feelings-and-symptoms/anxiety-disorder-signs/ |

| Somatic anxiety | Physical symptoms of anxiety such as headaches, muscle tension, discomfort in chest, abdomen or other body parts. Autonomic manifestations of anxiety include palpitations, sweating, tremor, dizziness, sexual dysfunction. |

| Depression | Prolonged period of low mood, low energy and loss of interest/pleasure (‘anhedonia’). https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/clinical-depression/overview/ |

| Functional symptoms | Persistent physical symptoms in an organ or system where there is no identifiable structural or metabolic abnormality. Example is irritable bowel syndrome. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs/ |

| Eating disorders | A group of mental disorders characterised by abnormal food intake, with or without preoccupations with low weight, body image and food restriction.65

https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/feelings-symptoms-behaviours/behaviours/eating-disorders/overview/ |

| Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) | Talking therapy. Based on theory that thoughts, emotions, behaviour and physiology interact, and the strong evidence that making changes in one of these areas alters the others.66

Aims to identify and understand problematic thinking styles, and to modify these in order to improve mood and relieve anxiety. Usually delivered in five - 20 individual or group sessions with a therapist to identify problem areas and where to apply changes in daily life. In England, accessed by self-referral to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT). https://babcp.com/ |

| Mindfulness | Aims to reduce stress by paying attention to a patient’s experience in the moment, with a non-judgemental and curious attitude, and the flexibility to consciously direct their attention towards other aspects of their experience.67 Taught in stress reduction programmes and in various apps. It is a key component of acceptance and commitment therapy and can be combined with CBT. |

| Acceptance and commitment therapy | Talking therapy that combines CBT strategies with mindfulness skills to increase psychological flexibility and ability to handle painful thoughts and feelings effectively. Aims to help create rich, meaningful lives while accepting the pain that life inevitably brings. Newer treatment, with limited evidence base.57 |

| Hypnotherapy | Uses intentional induction of a deeply relaxed or trance-like state (hypnosis), to try to treat conditions or change habits. Hypnosis occurs without loss of will or consciousness. |

After a brief overview of the prevalence of mood disorders in patients with IBD, we shall outline what is known of the mechanisms underlying the bidirectional relationship between mood disturbances and IBD. We shall then describe how the IBD team can offer holistic care—from the time of diagnosis and across the lifespan, maximising the chance of prompt recognition and treatment of mood disorders when they arise. We shall conclude by offering practical suggestions about how to provide a stepped care approach to prevention and management of mood disturbances in patients with IBD. As we shall mention later, there is limited trial data on the effectiveness of some of the available therapeutic modalities in the specific context of IBD. Our recommendations are therefore based additionally on evidence of how best to treat comorbid mental disorders in other long-term conditions, and on our clinical experience.

Prevalence of, and risk factors for mood disorders in IBD

Mood disorders are more common in people with IBD than in the general population. In two large recent meta-analyses including over 30 000 and 1 50 000 patients, respectively, the prevalence of symptoms of anxiety in IBD was 32%–35%, and of depression 22%–25%,1 2 with figures for established anxiety and depression being 20% and 15%, respectively. Differences in the provision of psychiatric support at local community level make it hard to quantify with precision the impact of these disorders on IBD outpatient and emergency services in the UK. However, reports from Australia, the USA and the UK suggest that an integrated psychiatric service for patients with IBD, offered along the lines we advocate below, may reduce this impact and its related costs.6–8

At increased risk of mood disturbance are women, elderly patients9 and those with Crohn’s disease, a severe disease course, active disease or comorbidities. This risk is influenced by illness perceptions, coping strategies, past experiences and social support.10 11 Emotions such as distress, grief, guilt and denial are common and should be routinely anticipated.9 12 Functional gastrointestinal symptoms and fatigue in quiescent IBD and in the absence of anaemia or nutritional deficiencies, are much more common than in the general population and are associated with psychological morbidity.13–15 Their presence should thus alert healthcare professionals (HCPs) to possible mood disturbance.

A recent systematic review with meta-analysis suggested that, contrary to widespread belief, mood disorders are less common in children and adolescents than in adults.16 It should be noted, however, that young people suffering from psychiatric morbidity may present differently from adults: for example, use of psychotropic drugs, non-adherence to IBD medications,17 eating disorders and failure to attend follow-up clinic appointments commonly reflect mood disorders in adolescents.

In active IBD, gut symptoms are often associated with food intake, leading to restrictive eating behaviour. Disordered eating behaviour is more prevalent in patients with IBD than in the general population and persistent abnormal food intake, especially in the absence of active disease, should alert the clinician to a possible eating disorder.18 19

Recent reports from all over the world indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased psychological stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with IBD, particularly in younger people and in those with pre-existing mood disturbances.20 During the pandemic, it has been difficult to provide prompt access for patients to hospital IBD services, especially face to face, and it is important for their well-being to maintain availability of IBD nursing and psychological support as far as possible, and to provide them with information about the interactions between COVID-19, IBD and its treatment.21–23

Bidirectional links between mood disorders and IBD

The links between mood disorders and IBD are bidirectional.24 Thus, while IBD can pose a potent threat to psychological well-being, antecedent depression and anxiety may predispose to the development of IBD, particularly Crohn’s disease.25 Furthermore, several studies have indicated that incident psychological disorders can trigger relapse, worsen disease course and impair response to treatment in IBD.24 26–28 Conversely, improvement of psychological well-being on induction of remission29 and a beneficial effect of antidepressant use on IBD disease course use30 have also been documented. Whether psychological disorders should be regarded as an extra-intestinal manifestation of IBD, for example, mechanistically linked via the gut-brain axis to mucosal inflammation and the gut microbiome,31 is beyond the scope of this paper.

The practical implications of the bidirectional links between the gut and brain in IBD are fourfold. First, treating psychological disorders in patients with IBD may improve their mood and QOL, and the natural history of their IBD.32 Second, recognition that patients with IBD are at risk of psychological disturbance at particular times in their disease course should focus the care provider on enquiring for symptoms indicative of mood disorder at such psychological ‘pressure points’. Third, given the clear relationship between mood disturbances and active IBD, in order to optimise psychological well-being, every effort should be made to maintain patients in clinical remission. Lastly, and more speculatively, it is possible that further understanding of the links between the brain and gut may in the future open new approaches to the management of both IBD and its associated mood disturbances.

Management

The need for change in IBD service provision

Patient numbers in IBD clinics are rising and many services can offer only limited time for consultations. Most gastroenterologically trained HCPs have had little or no training in how to recognise or manage psychological aspects of IBD33 as they evolve during the course of their illness.

Integrated biopsychosocial model of IBD care

There is consensus that integrated care offers an ideal framework to meet patients’ biopsychosocial needs.3 33 In the UK at least, we are far from reaching this ideal: a recent survey organised by Crohn’s and Colitis UK showed that only 2% of IBD services have sufficient support from psychologists to meet the UK National IBD Standards.5 HCPs with special expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders may include psychiatrists, psychologists, counsellors, psychiatric nurses, social workers and others.33 Including such HCPs in the multidisciplinary team (MDT) enables the prompt provision of personalised psychological therapies and is welcomed by patients.5 34 It also leads to the diffusion of their specialist skills towards other members of the team. Lastly, since patients with IBD with a co-existing mental health diagnosis incur significantly greater overall IBD healthcare costs than those without,6 provision of an integrated IBD MDT may reduce rather than increase net costs, for example, by reducing attendances of patients with IBD to emergency departments.3 6

Stepped care for the recognition and management of psychological disorders in IBD

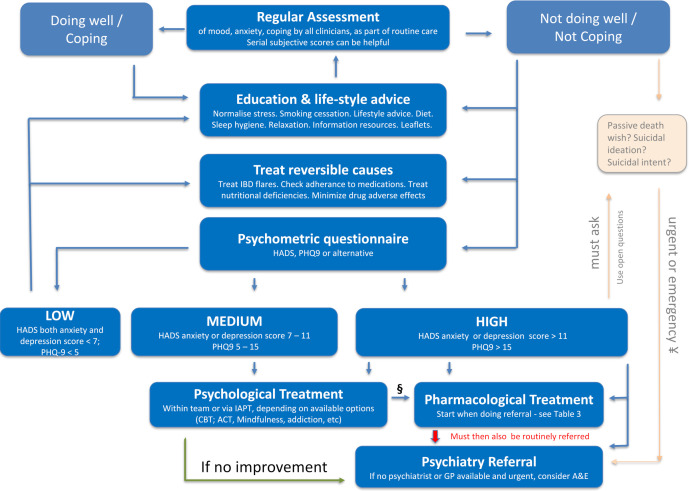

Living with IBD brings physical symptoms and uncertainty over a lifetime. Self-management with discussion between patients and HCPs to agree treatments, increases patients’ sense of control and, for most people, will reduce psychological burden. In busy IBD clinics, psychological distress is easily overlooked35 but it is everyone’s job within the MDT to assess patients regularly for mood disorders. There are several guiding principles for managing this task, which can be followed in a stepwise approach (figure 1).

Figure 1.

This figure serves as a guide for the steps than can be taken in the psychological care of IBD patients by all members of the MDT. HADS or other psychometric scores can be used in adult patients (over 18) to alert clinicians that patients need help, but scores alone are not diagnostic of mood disorders and the decision to treat always depends on physician judgement and patient preference. § Some patients with mild to moderate depression may benefit from pharmacological together with psychological treatment; the decision will depend on symptom load. ¥ Patients with a passive death wish could be referred for routine or urgent psychiatric evaluation. For patients with current suicidal ideas or active suicidal intent an emergency (same day) referral must be made. ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; A&E, accident and emergency department; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; GP, general practitioner; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale; IAPT, improving access to psychological therapies; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire 9.

Regular assessment of mood normalises the concept of stress (see below) and promotes engagement while reducing perceived stigma and reluctance to discuss ‘emotional stuff’. Ask open questions (“how are you doing generally?”) then more specific ones (“describe your mood lately; how are your stress levels?”) that alert the team that a person feels overwhelmed.

Identify also the patient’s narrative about their IBD: age of first symptoms, time taken to IBD diagnosis, disruption to a person’s identity, relationships, education/employment, treatment failures and current concerns (about intimacy, fertility, surgery, cancer). A shared family narrative where relatives had negative IBD experiences (‘the doctors missed this; bad surgery’) may inform the patient’s current overview.

Measurements of patients’ subjective anxiety are useful. Ask them to score this out of 10; 0 is none, and 10 is the most anxiety possible, and record these in a series of anxiety scores: score at time of first diagnosis, perisurgery, times of severe IBD or a family crisis, etc, as this can provide comparative information about how someone is currently managing.

Measure subjective mood too. Most of us on most days carry a subjective mood of 8/10 (0 is the worst possible; 10 is the happiest day of our life). Ask the difficult closed question: “your mood now is 3/10, do you ever wish you could go to sleep and not wake up?” A yes answer indicates a passive death wish, and alerts the clinician that a patient feels overwhelmed or depressed. “Is this fleeting or constant, and did you think you might act on these thoughts?” For patients with a passive death wish that has led to suicidal ideation, referral for psychiatric evaluation should be considered. If they are already engaged in mental health services, direct them back to this care. Psychiatric referral becomes urgent in patients with current suicidal ideas or active suicidal intent. If prompt assessment by the mental health team or GP is unavailable, consider referring to accident and emergency department. Know also your local mental health crisis phonelines, and provide these plus national helplines (table 2).

Table 2.

Mental health support available in the UK

| Mental health support | Access |

| NHS psychological therapies | Everyone in England, aged 18 years or over, and registered with a GP, can access NHS psychological therapies services via IAPT (https://www.nhs.uk/service-search/find-a-psychological-therapies-service/). Referral is by patients themselves or by their GP. IAPT services offer a range of talking therapies and guided self-help. |

| Local NHS mental health telephone helpline | The NHS operates urgent mental health helplines throughout England. They offer 24-hour advice and support for people of all ages. Local helpline telephone numbers can be found on https://www.nhs.uk/service-search/mental-health/find-an-urgent-mental-health-helpline |

| National NHS mental health telephone advice | NHS 111 can be accessed for urgent for mental health support if local NHS urgent mental health helplines are not available. Telephone number 111 or https://111.nhs.uk/ |

| Samaritans | In the UK, Samaritans operate a confidential telephone helpline, providing emotional support 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (free telephone number 116 123). |

GP, general practitioner; IAPT, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies; NHS, National Health Service.

Education and lifestyle advice benefit everyone. Normalise psychological reactions: stress and distress are common with all unpredictable, painful long-term conditions—and IBD disrupts key social activities (eating with others, visits to bathroom, dating). There is some evidence for the benefits of smoking cessation, gentle exercise 3–5 times a week and sleep-hygiene including avoidance of stimulants, in general populations36 and patients with irritable bowel syndrome.37 Patients’ perspectives are key: if they perceive high stress and/or judge their social supports to be poor, respond with achievable lifestyle changes and problem solving. Apps such as MyIBDCare38 and MyIBDCoach39 can be used to nudge patients to make positive changes.

Functional GI symptoms are common in IBD, occurring in a quarter of patients in deep remission and associated with psychological comorbidity.13 A diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) may provide relief of these gut symptoms in quiescent IBD and improve food-related QOL.40

In our experience, early discussion of these lifestyle and other social interventions helps many patients cope with their current stress and facilitates later discussion of antidepressants if low mood and anxiety fail to improve.

Treat reversible causes of psychological distress: active IBD is associated with increased psychological distress1 2 and should be assessed and treated where possible.29 Anaemia in patients with IBD is often associated with both depression and fatigue, and its treatment can improve QOL in general and psychological state and fatigue.41 42 Systemic steroids can adversely affect mood43 and should be avoided/withdrawn where possible. However, do not limit thinking to the two ‘boxes’ of IBD severity and mental disorders: many other factors drive poorer QOL. These include poor diet, addictions and social stressors such as poverty, insecure housing and relationship breakdown.

Psychometric questionnaires are useful for identifying the presence and severity of adverse mood symptoms and low mood should trigger their use. The result obtained can direct referral for psychological and/or psychiatric assessment.35 A range of validated options is available: we favour the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),44 because it is quick and easy to complete, is widely used and does not include somatic symptoms which could reflect IBD activity rather than mental state. CORE1045 is a good tool for its brevity. Across primary care and psychological services, the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)46 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 747 are widely used. These psychometric scores have been validated in adults and cannot be used in children (under 18 years of age).

Psychometric questionnaires alone are not diagnostic and cannot be a substitute for a conversation as they do not necessarily reflect an individual’s personal context or understanding of their situation. Some patients will score well on a measure but feel they cannot cope, while others who score badly may feel they are managing well and do not want specialist support.

Psychometric scores

HADS scores can be used to alert clinicians that a patient needs intervention. A decision to treat always depends on physician judgement and patient preference, hence the below HADS cut-offs are used to serve as a guide to the symptom burden and risk level of these patients. In addition, individual services may have differing capacity and referral criteria.

Low

For patients with low psychometric score (HADS score <7 on both the anxiety and depression scales; PHQ score <5), no specific psychological treatment is recommended and they should be encouraged to follow the lifestyle interventions described (figure 1).

Medium

When mood or anxiety symptoms are persistently impinging on functioning, referral for more specific psychological treatment should be considered. This corresponds to medium psychometric scores: HADS score 7–11 on either the anxiety or depression scale; PHQ-9 score 5–14.

High

For patients with severe anxiety or depression, corresponding with a HADS score >11 on either scale, or PHQ-9 score >15, we recommend referral for psychological treatment and that clinicians consider, based on their clinical impression, an antidepressant. This can be started by the IBD doctor or IBD nurse prescriber, and should be accompanied by referral to a psychiatrist.

Psychological treatments

There is limited good quality research into the effects of psychological interventions on mood, QOL and disease course specifically in patients with IBD, and conclusions drawn are generally mixed. Additionally, an intervention shown to be effective when given to populations of patients with IBD may not be beneficial in a given individual in which a range of different factors may be contributing to their psychological distress.12 48 Conversely, despite lack of evidence from trials, particular psychological interventions might be of benefit in an individual patient with IBD.49 Notwithstanding this practical limitation of the therapeutic application of trial data, the following psychological treatments can be offered to patients with IBD.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has a strong evidence base in the general population.50 51 In IBD, the best available evidence for psychological therapies on psychological well-being is for CBT, which has been shown to improve QOL, at least briefly. In systematic review and meta-analyses, however, CBT has no clear effect on anxiety or stress in patients with IBD.52–54 The studies demonstrating benefit were done in patients with quiescent disease and there is very limited data with mixed results in patients with active disease.53 54

Mindfulness-based therapies have a modest effect in IBD on QOL, stress and depression but have no effect on anxiety.54 55 CBT can be combined with mindfulness and in one recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) was shown to reduce psychological symptoms and fatigue in patients with mild-to-moderate Crohn’s disease.56

Hypnotherapy has given mixed results in IBD, with improved QOL in one and non-significant improvement in another study.54

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a newer treatment57 58 that thus far has a limited evidence base, but is showing promise for use in long-term conditions.59 In one RCT of patients with quiescent and active IBD, it was shown to reduce stress, perceived stress and depression, but not anxiety.60

Notwithstanding the results of some individually reported studies, none of these psychological interventions has been shown to improve IBD disease activity or course in systematic reviews.54

Accessing psychological therapies

The decision for referral for psychological treatment should consider motivation for change and ability to engage with the proposed psychological intervention. Few interventions will lift the mood of someone in a toxic relationship or of a heavy drinking, isolated patient.

Psychological therapy can be provided from within the team, if the IBD MDT includes a psychologist or psychotherapist. If this is not available, in England, everyone aged 18 years and registered with a GP can access NHS psychological therapies using improving access to psychological services (IAPT) (table 2), via GP or self-referral. IAPT services offer a range of talking therapies including CBT. A minority of patients will not improve with these CBT interventions and will be referred on by IAPT to specialist mental health services.

Antidepressants

There is a reluctance among physicians to prescribe antidepressants, probably as a result of their lack of experience in this area, but they are very effective in treating anxiety and depression.61 While evidence for the efficacy of antidepressants in improving mood in patients with IBD62 is less clear, this is in part because there have been only a small number of studies, including limited patient numbers. Some benefits have been identified and include improving QOL, managing associated functional GI symptoms, improving sleep, reducing chronic pain and (with some antidepressants) potentially favourable immunoregulatory effects.62 Despite the limitations of existing data relating to the use of antidepressants in people with IBD, there is good evidence that they are effective in other chronic illnesses.63

Our practice is to encourage gastroenterologists to start antidepressants for patients with a HADS score >11 on either the anxiety or depression axis, and in parallel with psychiatric referral. Regular review by psychiatry of response to antidepressants, identifies non-responders and risk of suicidal behaviours. A practical guide for prescribing antidepressants is given in table 3.

Table 3.

Guide to prescribing first-line antidepressants

| Drug class | Name | Start dose | Subsequent dose | Positives | Negatives |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) | Fluoxetine | 20 mg once a day | Increase, if necessary, after 6 weeks to 40 mg once a day | Longest half-life: discontinuation syndrome unlikely. Does not cause weight gain (as other SSRIs). |

1/5 experience upper GI symptoms in first days, always recommend taking with food, typically breakfast as sedative side effect is unlikely. Consider initiating on half the start dose to minimise these effects. Sexual side effects† common. |

| Sertraline | 50 mg once a day | Increase, if necessary, after 6 weeks to 100 mg once a day | Fewer upper GI side effects than other SSRIs. | ||

| Citalopram | 20 mg once a day | Increase, if necessary, after 6 weeks to 30 mg once a day | Safest in liver impairment. | ||

| Presynaptic alpha 2-adrenoreceptor antagonist | Mirtazapine | 15 mg once a day | Adjust dose, if necessary, every 2–4 weeks by 15 mg to maximum dose of 45 mg once a day | Promotes sleep and has antinausea action due to antihistamine effects. Anti-anxiety effects, useful in panic disorder. | Weight gain. 1/5 patients fail to tolerate due to daytime sedation. Sexual side effects.† |

All have liquid preparations, some have orodispersible strips. Citalopram has an intravenous form. Suicidal ideas can arise in early antidepressant treatment,68 give patients numbers of local 24-hour mental health crisis help lines or Samaritans telephone number to access if their mental health deteriorates (table 2).

*12 weeks in adults over 65 years old.

†Sexual side effects: low sex drive; difficulty achieving orgasm; erectile dysfunction.

GI, gastrointestinal.

For the general population, CBT is recommended as treatment for mild-to-moderate depression; however, for long-term conditions including IBD, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommend that CBT combined with antidepressants works better than either alone.63 Meta-analysis of treatment of depression in patients with IBD also shows that combined therapy showed greater benefit than either alone.64

Discussion

Two major challenges hinder the optimisation of the management of patients with IBD and psychological comorbidity. The first is to ensure that the IBD team in every centre includes in-built psychological and psychiatric support, in line with recommendations in the UK National IBD Standards. This is to share in the care of patients with IBD when appropriate, and, as mentioned earlier, to make possible regular in-house training of non-specialists in how to manage comorbid mood disorders. Those seeking to persuade hospital managers of the need to expand their IBD team in this way can remind them that this is a cost-reducing move.6 7

The second, less immediately tractable problem is to rectify the paucity of currently available high-quality data, as mentioned above, to guide treatment decisions. Indeed, for this reason, some of the present recommendations should be regarded as expert advice based on clinical experience rather than following directly from published evidence. Reasons for the inadequacy of current trial data have been reviewed elsewhere,49 and in part reflect the ‘one-size-fits-all’ principle necessary for RCTs. Thus, even if the substantial difficulties associated with the design of trials to assess the efficacy of psychological and pharmacological therapies can be overcome, there will remain the need to tailor therapy to the individual patient, for example, to the stage of their adjustment to their IBD.48

Psychological comorbidity has a major negative impact on the lives of people with IBD. In this paper, we have set out a stepwise approach, based on our own practice, to identify and manage psychological stress and mood disorders in patients with IBD. This approach should be adopted by every member of the IBD team, with the aim of providing holistic and individualised care throughout the course of the IBD of the patients attending their clinics. Not everyone who works in the team will feel confident about how to proceed when faced with a distressed patient in a time-limited clinic, and we hope that the advice and the algorithm provided here (figure 1) will help guide their response.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were responsible for design of study, data collection and critical revisions to the manuscript. KBK, PB, PM, DSR: data analysis and authorship. DSR and PB original idea.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Barberio B, Zamani M, Black CJ, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:359–70. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2016;87:70–80. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lores T, Goess C, Mikocka-Walus A, et al. Integrated psychological care is needed, Welcomed and effective in ambulatory inflammatory bowel disease management: evaluation of a new initiative. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:819–27. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Engel K, Homsi M, Suzuki R, et al. Newly diagnosed patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the relationship between perceived psychological support, health-related quality of life, and disease activity. Health Equity 2021;5:42–8. 10.1089/heq.2020.0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crohn’s and Colitis Care in the UK: The Hidden Cost and a…. IBD UK. Available: https://ibduk.org/reports/crohns-and-colitis-care-in-the-uk-the-hidden-cost-and-a-vision-for-change

- 6. Szigethy E, Murphy SM, Ehrlich OG, et al. Mental health costs of inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2021;27:40–8. 10.1093/ibd/izaa030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lores T, Goess C, Mikocka-Walus A, et al. Integrated psychological care reduces health care costs at a hospital-based inflammatory bowel disease service. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:96–103. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wahed M, Corser M, Goodhand JR, et al. Does psychological counseling alter the natural history of inflammatory bowel disease? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:664–9. 10.1002/ibd.21098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ludvigsson JF, Olén O, Larsson H, et al. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and psychiatric morbidity and suicide: a Swedish nationwide population-based cohort study with sibling comparisons. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15:1824–36. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sajadinejad MS, Asgari K, Molavi H, et al. Psychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012;2012:1–11. 10.1155/2012/106502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jordan C, Sin J, Fear NT, et al. A systematic review of the psychological correlates of adjustment outcomes in adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Psychol Rev 2016;47:28–40. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Menichetti J, Fiorino G, Vegni E. Personalizing psychological treatment along the IBD journey: from diagnosis to surgery. Curr Drug Targets 2018;19:722–8. 10.2174/1389450118666170502142939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fairbrass KM, Costantino SJ, Gracie DJ, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:1053–62. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30300-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gracie DJ, Hamlin JP, Ford AC. Longitudinal impact of IBS-type symptoms on disease activity, healthcare utilization, psychological health, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:702–12. 10.1038/s41395-018-0021-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hindryckx P, Laukens D, D'Amico F, D’Amico F, et al. Unmet needs in IBD: the case of fatigue. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018;55:368–78. 10.1007/s12016-017-8641-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stapersma L, van den Brink G, Szigethy EM, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:496–506. 10.1111/apt.14865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brooks AJ, Rowse G, Ryder A, et al. Systematic review: psychological morbidity in young people with inflammatory bowel disease - risk factors and impacts. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:3–15. 10.1111/apt.13645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Day AS, Yao CK, Costello SP, et al. Food-Related quality of life in adults with inflammatory bowel disease is associated with restrictive eating behaviour, disease activity and surgery: a prospective multicentre observational study. J Hum Nutr Diet 2022;35:234-244. 10.1111/jhn.12920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peters JE, Basnayake C, Hebbard GS, et al. Prevalence of disordered eating in adults with gastrointestinal disorders: a systematic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021;e14278:e14278. 10.1111/nmo.14278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Graff LA, Fowler S, Jones JL, et al. Crohn's and colitis Canada's 2021 impact of COVID-19 and inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: mental health and quality of life. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2021;4:S46–53. 10.1093/jcag/gwab031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheema M, Mitrev N, Hall L, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: Australian national survey. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2021;8:e000581. 10.1136/bmjgast-2020-000581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mir N, Cheesbrough J, Troth T, et al. COVID-19-related health anxieties and impact of specific interventions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the UK. Frontline Gastroenterol 2021;12:200–6. 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luber RP, Duff A, Pavlidis P, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress among inflammatory bowel disease patients during COVID-19: a UK cohort study. JGH Open 2022;6:76–84. 10.1002/jgh3.12699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gracie DJ, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. The influence of the brain-gut axis in inflammatory bowel disease and possible implications for treatment. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:632–42. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30089-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peppas S, Pansieri C, Piovani D, et al. The brain-gut axis: psychological functioning and inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med 2021;10:377. 10.3390/jcm10030377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kochar B, Barnes EL, Long MD, et al. Depression is associated with more aggressive inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:80–5. 10.1038/ajg.2017.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jordi SBU, et al. Depressive symptoms predict clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2021;izab136. 10.1093/ibd/izab136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fairbrass KM, Gracie DJ, Ford AC. Longitudinal follow-up study: effect of psychological co-morbidity on the prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021;54:441–50. 10.1111/apt.16454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Loftus EV, Feagan BG, Colombel J-F, et al. Effects of adalimumab maintenance therapy on health-related quality of life of patients with Crohn's disease: patient-reported outcomes of the CHARM trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:3132–41. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kristensen MS, Kjærulff TM, Ersbøll AK, et al. The influence of antidepressants on the disease course among patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative Colitis-A Danish nationwide register-based cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:886–93. 10.1093/ibd/izy367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moulton CD, Pavlidis P, Norton C, et al. Depressive symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease: an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammation? Clin Exp Immunol 2019;197:308–18. 10.1111/cei.13276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Macer BJD, Prady SL, Mikocka-Walus A. Antidepressants in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:534–50. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mikocka-Walus AA, Andrews JM, Bernstein CN, et al. Integrated models of care in managing inflammatory bowel disease: a discussion. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:1582–7. 10.1002/ibd.22877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eccles JA, Ascott A, McGeer R, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease psychological support pilot reduces inflammatory bowel disease symptoms and improves psychological wellbeing. Frontline Gastroenterol 2021;12:154–7. 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lewis K, Marrie RA, Bernstein CN, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of undiagnosed depression and anxiety disorders among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:1674–80. 10.1093/ibd/izz045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, et al. A meta-review of "lifestyle psychiatry": the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2020;19:360–80. 10.1002/wps.20773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fikree A, Byrne P. Management of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Clin Med 2021;21:44–52. 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. My IBD Care: Crohn’s or Colitis Management App. Ampersand Health. Available: https://ampersandhealth.co.uk/myibdcare/

- 39. de Jong MJ, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. Telemedicine for management of inflammatory bowel disease (myIBDcoach): a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;390:959–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31327-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhan Y-le, Zhan Y-A, Dai S-X. Is a low FODMAP diet beneficial for patients with inflammatory bowel disease? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Nutr 2018;37:123–9. 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gasche C, Lomer MCE, Cavill I, et al. Iron, anaemia, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 2004;53:1190–7. 10.1136/gut.2003.035758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rampton DS, Goodhand JR, Joshi NM, et al. Oral iron treatment response and predictors in anaemic adolescents and adults with IBD: a prospective controlled open-label trial. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:706–15. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brown ES, Chandler PA. Mood and cognitive changes during systemic corticosteroid therapy. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3:17–21. 10.4088/PCC.v03n0104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barkham M, Bewick B, Mullin T, et al. The CORE-10: a short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 2013;13:3–13. 10.1080/14733145.2012.729069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, et al. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016;39:24–31. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maunder R, Esplen MJ. Facilitating adjustment to inflammatory bowel disease: a model of psychosocial intervention in Non-Psychiatric patients. Psychother Psychosom 1999;68:230–40. 10.1159/000012339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goodhand JR, Wahed M, Rampton DS. Management of stress in inflammatory bowel disease: a therapeutic option? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;3:661–79. 10.1586/egh.09.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Richards DA, Ekers D, McMillan D, et al. Cost and outcome of behavioural activation versus cognitive behavioural therapy for depression (cobra): a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016;388:871–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31140-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wiles NJ, Thomas L, Turner N, et al. Long-Term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in primary care: follow-up of the cobalt randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:137–44. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00495-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li C, Hou Z, Liu Y, et al. Cognitive-Behavioural therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Pract 2019;25:e12699. 10.1111/ijn.12699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gracie DJ, Irvine AJ, Sood R, et al. Effect of psychological therapy on disease activity, psychological comorbidity, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:189–99. 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30206-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Paulides E, Boukema I, van der Woude CJ, et al. The effect of psychotherapy on quality of life in IBD patients: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2021;27:711–24. 10.1093/ibd/izaa144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ewais T, Begun J, Kenny M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness based interventions and yoga in inflammatory bowel disease. J Psychosom Res 2019;116:44–53. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Goren G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral and Mindfulness-Based stress reduction on the quality of life of patients with Crohn disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2021;izab083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Harris R. Act made simple: an easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Acceptance and commitment therapy (act). Available: https://babcp.com/Membership/Special-Interest-Groups/ACT

- 59. Graham CD, Gouick J, Krahé C, et al. A systematic review of the use of acceptance and commitment therapy (act) in chronic disease and long-term conditions. Clin Psychol Rev 2016;46:46–58. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wynne B, McHugh L, Gao W, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy reduces psychological stress in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2019;156:935–45. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018;391:1357–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mikocka-Walus A, Prady SL, Pollok J, et al. Adjuvant therapy with antidepressants for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;4:CD012680. 10.1002/14651858.CD012680.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Overview | depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: recognition and management | guidance | NICE. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91

- 64. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL, et al. Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2014;13:56–67. 10.1002/wps.20089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Claudino AM, Pike KM, Hay P, et al. The classification of feeding and eating disorders in the ICD-11: results of a field study comparing proposed ICD-11 guidelines with existing ICD-10 guidelines. BMC Med 2019;17:93. 10.1186/s12916-019-1327-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Westbrook D, Kennerley H, Kirk J. An introduction to cognitive behaviour therapy: skills and applications. SAGE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2003;10:125–43. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Taylor DM, Barnes TRE, Young AH. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons, 2021. [Google Scholar]