Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization and the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region recommend the self-assessment of public health core competencies to strengthen the proficiency of the public health workforce and prepare them for future challenges. A framework for these competencies is lacking and highly needed in Lebanon. This study aims to validate the WHO-ASPHER self-declared scale and evaluate the perceived competency level of the different categories of Lebanese public health practitioners.

Methods

This population-based cross-sectional study conducted online between July and September 2021 involved 66 public health practitioners who graduated from different universities in Lebanon. Data were collected using the snowball technique via a self-report questionnaire that assessed public health proficiency, categorized into 1) content and context, 2) relationship and interactions, and 3) performance and achievements. The rotated component matrix technique was used to test the construct validity of the scales. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed after ensuring the adequacy of the models. Significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

The factor analysis for scale domains showed that the Barlett test sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), high loadings of items on factors, and Cronbach’s alpha values of more than 0.9 in all three categories, showing an appropriate scale validity and reliability. The perceived level of competencies was significantly different between public health professionals and other health professionals with public health activities. All respondents scored low in most public health categories, mainly science and practice.

Conclusion

Data findings showed variability of self-declared gaps in knowledge and proficiency, suggesting the need to review the national public health education programs. Our study offers a valuable tool for academia and public health professionals to self-assess the level of public health proficiency and guide continuous education needs for professional development.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-022-03940-4.

Keywords: Competencies, Public Health, Scale, Validation, WHO-ASPHER

Background

Public health is an organized societal effort based on different structures and processes intended to understand, safeguard and improve population health and reduce health inequalities [1–3]. It is the art of applying science in the context of politics to assess the influences of health systems and interventions on societies’ mental and physical health promotion and efficiency, health protection, and disease prevention [1–8]. Public health tackles all socioeconomic, political, physical, chemical, and biological conditions that impact or interact with the population’s health [9]. A high-performing public health system requires a competent public health workforce with adequate baseline capacity and transferrable skills to be held professionally accountable for the health of a defined population [9–14]. Therefore, a lack of workforce competence contributes to substandard service delivery [15] and leads to social, economic, and health burdens [14–16]. Alternatively, strengthening the performance and core competencies contributes to the sustainable development of nations [14, 17].

To ensure a high level of proficiency and highlight the gaps in knowledge that need strengthening, self-assessment of core competencies in public health is considered a starting point. The baseline requirements for high-level public health performance and service delivery differ between countries [18]. More than ten frameworks for assessing core competencies in public health are available for use, originating from different countries such as the United States of America (USA), Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and other European countries [9, 19–28]. The knowledge and skills needed to carry out core professional functions in public health are complex [9, 10, 20].

Published studies used mainly a formulated survey to assess the perceived needs of public health practitioners for training and identify gaps in knowledge [29–31]. A recent review of the questions asked in 24 published articles showed a lack of consistency, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings [32]. Another systematic review published in 2012 evaluated 126 public health workforce articles and gray literature and recommended the development of quantifiable output measures to offer baseline data to build models that address workforce demand [33]. This finding highlights the need for a country-specific framework for the self-assessment of public health core competencies to overcome these barriers.

Consequently, in the absence of requirements for health workers to receive public health training and the lack of preset national core competencies to assess the competence of the public health workforce, matching population health priorities and professional competencies is very challenging [26]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER) set a context-specific core competency framework designed to assess the gaps and weaknesses in the levels of knowledge, skills, aptitudes of public health practitioners, aiming to strengthen public health workforce [26]. The framework provides level descriptors to interpret the extent to which competencies are mastered based on the Dreyfus model of adult skill acquisition [34]. The WHO framework sets three categories of competency needed to assess the extent of mastered competencies in each domain [26]. Category 1 evaluates the science and practice, health promotion, one-health, and security; it also tackles law, policies, and ethic-related frameworks that reinforce public health practice. Category 2 examines the level of competencies in terms of relations and interactions, such as communication and advocacy, collaboration and partnership, and leadership and system thinking. Category 3 addresses performance and achievements, such as professional development, governance, ethical practice, and resource management [26].

The assessment of competencies offers a broader perspective on how to serve the needs of populations and create people-centered services. It also helps improve the curricula and continuing professional development based on existing capacity and training requirements [26, 35].

Furthermore, lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the gaps in global health systems readiness facing this threat and the need to strengthen the core competencies of the health workforce to deliver efficient public health functions [35–38]. More specifically, in Lebanon, the pandemic and the Port of Beirut explosion on August 4, 2020, revealed a chaotic Lebanese health system, struggling to manage these concomitant public health crises with limited or lack of resources, drug shortages, a damaged infrastructure, health professionals’ migration, and economic downturn [39]. This challenging situation shows the need for a national health system plan for humanitarian crises, relying on a highly competent and trained public health workforce. The public health workforce (PHW) is highly diverse and complex [40], including a broad range of occupational backgrounds trained in a variety of institutional settings involved in the protection and promotion of public health [40].

To our knowledge, little is known about the competencies of public health professionals in Lebanon. Public health education is delivered in schools/faculties of health sciences and/or health professions. Degrees offered can be undergraduate or graduate and can be professionally oriented or research-driven (i.e., to be completed by a PhD). Public health professionals work in public and private sectors (non-governmental organizations and health institutions), while some teach in universities. The only professional association for public health workers in Lebanon is the Lebanese Epidemiological Association (LEA), which has been providing an umbrella to academic and field workers in epidemiology and public health in Lebanon since 1994. However, it does not have guidelines related to the job market of public health professionals and does not give directions regarding national educational needs in the field.

This study primarily aims to validate the public health self-assessment competency scale adapted from the WHO-ASPHER framework and assess the self-declared competencies of Lebanese public health professionals using a validated scale. The results would help determine the gaps in knowledge, prioritize the domains that need strengthening in public health, and identify the national public health educational program needs and necessary competencies for prospective public health bachelor or master graduates.

Methods

Study design and sampling

A population-based cross-sectional study conducted online between July 01, 2021, and September 30, 2021, involved 66 public health practitioners who graduated from different universities in Lebanon. Data were collected using the snowball technique via a self-report questionnaire developed on Google Forms (https://forms.gle/J4wXjq5sZUBYdqfR7) and shared on social media (WhatsApp, Facebook, and LinkedIn) of healthcare professional groups and public health graduates from different universities (Additional file 1 Appendix 1). Public health graduates and practitioners, healthcare professionals involved in public health activities in Lebanon, and epidemiologists were eligible to participate in the study.

Ethics approval

The Lebanese International University research committee approved this study (2020RC-047-LIUSOP). The objectives were stated on the landing page of the survey, and participants had to consent to participate before enrolling. They received no compensation in return for their participation, which was entirely voluntary.

Sample size calculation

The G-power 3.1.9.4 software [41] calculated a minimum sample of 64 participants based on a Cohen effect size f2 = 30% (large explanation of the dependent variable by the model variables), an alpha error of 5%, a power of 80%, and considering ten factors to be entered in the multivariable analysis.

Questionnaire (Appendix 1)

The online survey tool was in English and included closed-ended questions. It was inspired by published articles and reports [14, 19, 25] and adapted by the authors (of whom three are public health experts) to fit the Lebanese context of public health practice. Some items were clarified by adding the geographical location “in Lebanon”, while others were removed or adapted to the Lebanese practice.

The questionnaire consisted of four main sections. The first section covered sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, area of residence, specialization field, public health practice domain, and years of experience). The second section consisted of public health essential operations, and the third section assessed the level of public health workforce competency (detailed below). In the fourth section, public health practitioners gave feedback on their experience by rating 15 statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from totally disagree to totally agree. The five options were collapsed into three categories as follows: strongly agree/agree, neutral, disagree/strongly disagree.

Competency assessment section

Competency assessment items were distributed over three main categories, each composed of several domains, as presented by the WHO-ASPHER framework [26]:

Content and context. This category encompasses four domains: 1) Science and practice; 2) Promoting health; 3) Law, policies, and health services; 4) One-health and health security.

Relations and interactions. This category encompasses three domains: 1) Leadership and systems thinking; 2) Collaboration and partnerships; 3) Communication, culture, and advocacy.

Performance and achievements. This category encompasses three domains: 1) Governance and resource management; 2) Professional development and reflective ethical practice; 3) Organizational literacy and adaptability.

Participants were asked to rate their perceived level of proficiency on each competency statement in the three categories listed above [26] on a 4-point Likert scale: 1 (none: I am unaware or have very little knowledge of the skill), 2 (aware: I have heard of, but have limited knowledge or ability to apply the skill), 3 (knowledgeable: I am comfortable with my knowledge or ability to apply the skill), and 4 (proficient: I am very comfortable, am an expert, or could teach this skill to others). The average score for each category represents the total number of allocated scores per statement divided by the total number of statements per category. The results represent the average score for all domains. A score of 1–2 per domain means a low level of competency that needs strengthening, while a score of 3–4 is interpreted as a high level of competency [26].

Statistical analysis

Data were extracted from Google on an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using SPSS version 25.0. A descriptive analysis evaluated the sample demographic characteristics using the absolute frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations (SD) for quantitative measures.

The rotated component matrix technique was used to test the construct validity of the scales. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin’s (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were calculated to ensure the adequacy of the model [42]. Factors with eigenvalues values of more than one were retained, and the scree plot method was used to determine the number of components to extract [43]. Only items with factor loading greater than 0.4 were considered [44]. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to determine the internal consistency of the scale.

For bivariate analysis, the Chi-square test and the Fisher exact test were used to compare percentages, and the Student T-test and the Mann Whitney were applied to compare means between two groups. The multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed, considering the competency item per category as the dependent variable and the public health specialty versus others as the independent variable after adjusting for gender, years of experience, area of residence, and area of practice. Adjusted coefficients (beta) and their 95% confidence intervals served to interpret the associations between the dependent and independent variables. Residual plots were used to assess the assumptions of the MANCOVA (homoscedasticity); the linear relationship between the continuous dependent and the independent variables was ensured, in addition to the absence of interaction and co-linearity. In all cases, a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. Participants had a mean age of 29.74 ± 7.57 years, were predominantly females (84.8%), mainly living in Mount Lebanon (59.1%), with five or fewer years of experience (71.2%). Study degrees were distributed as follows: Bachelor of Science (BS) in public health (33.3%), pharmacy (21.2%), nursing (10.6%), nutrition (10.6%), and medicine (3%). The vast majority of the respondents practiced in more than one area (63.6%). The fields of practice included academia (63.6%), research epidemiology (57.6%), non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (47%), Ministry of Public Health (37.9%), and medical settings (36.4%), added to fresh graduates with a degree in public health (21.2%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the participants (n = 66)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 (15.2%) |

| Female | 56 (84.8%) |

| Area of residence | |

| Beirut | 18 (27.3%) |

| Mount Lebanon | 39 (59.1%) |

| Other region (North, south, Bekaa) | 9 (13.6%) |

| Years of experience | |

| 1 – 5 years | 47 (71.2%) |

| 6 – 10 years | 10 (15.2%) |

| More than 10 years | 9 (13.6%) |

| Basic specialty degree | |

| BS in Public health | 22 (33.3%) |

| Pharmacy | 14 (21.2%) |

| Nursing | 7 (10.6%) |

| Nutrition | 7 (10.6%) |

| Other | 16 (23.2%) |

| Area of practicea | |

| Academia | 42 (63.6%) |

| Medical setting | 24 (36.4%) |

| Research epidemiology | 38 (57.6%) |

| NGO | 31 (47.0%) |

| MOPH | 25 (37.9%) |

| Fresh graduate | 14 (21.2%) |

| Mean ± SD | |

| Age (years) | 29.74 ± 7.57 |

Abbreviations: BS bachelor of sciences, MOPH Ministry of Public Health, n number of participants, NGO non-governmental organization, SD standard deviation

aThe same person could have several areas of practice

Factor analysis of the WHO-ASPHER competency scale

A factor analysis was performed to assess the validity of the public health competency scale and the adequacy of the model.

For the “Content and Context” category, the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.923 for “Science and Practice”, 0.924 for “Promoting Health”, 0.915 for “Law, Policies, and Health Services”, and 0.972 for “One-Health and Health Security”. Regarding “Science and Practice”, the first factor explained the most variance by 69.97%, followed by 8.71% for the second factor. For “Promoting Health”, “Law, Policies, and Health Services”, and “One Health and Health Security”, the first factor explained all the variances by 76.16%, 81.91%, and 77%, respectively (Table 2A).

Table 2.

Factor analysis of public health competencies according to categories and domains

| A: Promax rotated matrix, for category 1: Content and Context | ||||

| Science and Practice domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Identify the strengths and weaknesses of routine data and use these data as part of the complex assessment of population needs | 4 | 1.073 | ||

| Determine the key features of the epidemiology, trends, incidence, and prevalence of the significant diseases in Lebanon | 2 | 0.833 | ||

| Address the main health needs of the Lebanese population | 6 | 0.832 | ||

| Retrieve, analyze, and appraise evidence from all data sources to support decision-making | 5 | 0.817 | ||

| Describe the features of national demographic structure and its implications for public health | 1 | 0.799 | ||

| Use vital statistics and health indicators | 3 | 0.798 | ||

| Compare and assess the needs and services provided to meet health needs | 8 | 0.785 | ||

| Establish and monitor indicators of population health | 7 | 0.766 | ||

| Contribute to or lead community-based health needs assessments | 9 | 0.598 | ||

| Show a high level of knowledge of research methods and analysis techniques | 12 | 1.055 | ||

| Design and conduct qualitative and/or quantitative research that adds to the evidence base for public health practice | 11 | 0.951 | ||

| Review routine data and the literature to what actions should be taken to meet health needs | 10 | 0.787 | ||

| Evaluate local public health services and interventions, applying sound methods based on recognized evaluation models | 13 | 0.692 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 78.68 | 69.97 | 8.71 | |

| Cronbach alpha = 0.964 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.923 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| Promoting Health domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Know the rationale for screening programs and the basis of secondary prevention in my country | 9 | 0.919 | ||

| Use health promotion theory and the options for delivering health-promotion initiatives | 1 | 0.897 | ||

| Challenge incorrect information delivered to the public using a wide range of approaches, including communication with the media and politicians | 8 | 0.897 | ||

| Promote the health of the public using evidence-based methods | 3 | 0.886 | ||

| Raise health literacy | 2 | 0.876 | ||

| Ensure that health education and health literacy activities are informed by evidence and/or theory | 4 | 0.875 | ||

| Contribute to the evaluation of the effectiveness of activities to promote health to lead changes at various levels across different sectors | 5 | 0.872 | ||

| Use appropriate methods to foster citizens empowerment and community engagement | 6 | 0.864 | ||

| Consult with the public to engage meaningful decision-making that represents the wider societal views | 7 | 0.855 | ||

| Focus on disease prevention, reduction of inequalities, and equity in access to health services | 10 | 0.849 | ||

| Explore the underlying causes of morbidity and mortality, and recommendations to address these determinants of health and health services | 11 | 0.805 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 76.16% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.968 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.924 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| Law, Policies, and Health Services domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Develop and implement strategies based on relevant evidence, legislation, emergency planning, procedures regulations, and policies | 6 | 0.927 | ||

| Contribute to the delivery of equitable and effective health care and policies to improve the health of the public | 5 | 0.923 | ||

| Maximize opportunities to protect and promote health and well-being using applied laws and regulations | 7 | 0.914 | ||

| Comply with the legislation and professional codes of practice in my interaction with others | 1 | 0.910 | ||

| Understand and apply the laws and regulations directly or indirectly applicable to the practice of public health in Lebanon | 2 | 0.903 | ||

| Apply scientific principles and concepts to inform discussion of health-related fiscal, social, and political issues | 3 | 0.886 | ||

| Compare and contrast health and social service delivery systems between countries | 4 | 0.871 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 81.91% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.962 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.915 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| One Health and Health Security domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Comply with the requirements of both formal and informal surveillance systems and conduct risk assessment | 9 | 0.911 | ||

| Prevent risks and mitigate the health crises that originate at the interface between human, animals, and environments and affect the health of the population | 2 | 0.902 | ||

| Apply the International Health regulations to coordinate and develop strategic partnerships and resources in key sectors and disciplines for health security purposes | 5 | 0.892 | ||

| Understand the impact of climate on health and the responsibility of public health for protecting the natural environment | 12 | 0.891 | ||

| Analyze critically the changing nature, key factors, and resources that shape One Health | 3 | 0.891 | ||

| Promote occupational health and health and safety regulations and legislations | 6 | 0.887 | ||

| Identify and describe environmental determinants of health and connections between environmental protection and public health policy | 11 | 0.882 | ||

| Use multisectoral evidence-based guidelines for preventing and controlling health risks and diseases | 8 | 0.881 | ||

| Understand the One Health | 4 | 0.875 | ||

| Identify and assure minimum safety standards in delivering services | 10 | 0.860 | ||

| Understand the local implications of the One Health approach and its global interconnectivity | 1 | 0.859 | ||

| Apply the practical principles of food safety essential to public health | 7 | 0.793 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 77.00% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.972 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.911 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| B: Category 2: Relations and Interactions | ||||

| Factor analysis, promax rotated matrix for Category 2: Leadership and Systems Thinking domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Catalyze behavioral, and/or cultural changes | 7 | 0.938 | ||

| Lead and work as part of an interdisciplinary team | 6 | 0.936 | ||

| Support initiatives for change at the organization, community, or individual level | 8 | 0.935 | ||

| Understand principles of systems thinking to the improve delivery of public health services | 9 | 0.926 | ||

| Facilitate the development of other leaders | 2 | 0.922 | ||

| Identify and support the roles and responsibilities of all team members, including external stakeholders | 3 | 0.922 | ||

| Show practicality, flexibility, and adaptability in working with others to achieve public health goals | 5 | 0.918 | ||

| Demonstrate emotional intelligence and understand the impact of one’s belief, values, and behaviors on decision-making and others’ reactions | 4 | 0.914 | ||

| Motivate others to work toward common vision, program, and/or organizational goals | 1 | 0.886 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 85.04% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.978 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.920 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| Collaboration and Partnerships domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Evaluate partnerships and address barriers to successful collaboration to improve public | 5 | 0.943 | ||

| Build, maintain, and effectively use strategic alliances, coalitions, professional networks, and partnerships to plan and generate evidence implement programs | 4 | 0.935 | ||

| Establish effective partnerships and understand the priorities and motivations of a wide range of stakeholders | 2 | 0.934 | ||

| Identify, connect, and manage relationships with stakeholders in interdisciplinary and intersectoral projects to improve public health services and goals | 3 | 0.917 | ||

| Understand and apply effective techniques for working with boards and governance | 6 | 0.916 | ||

| Work across sectors in organizational structures at the national and international levels | 1 | 0.846 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 83.88% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.961 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.880 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| Communication, Culture, and Advocacy domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Understand and apply cultural awareness and sensitivity in communication with diverse populations | 5 | 0.938 | ||

| Communicate with respect when representing professional opinions, and encourage other team members | 6 | 0.935 | ||

| Recognize that social media and social marketing are increasingly important tools | 4 | 0.927 | ||

| Deliver administrative tasks that require communication within or across organizations | 8 | 0.919 | ||

| Advocate for health-related public policies and services to promote and protect human health and well-being | 9 | 0.901 | ||

| Prepare a meeting agenda | 7 | 0.900 | ||

| Convey information and complex scientific evidence in an understandable way to people | 3 | 0.896 | ||

| Communicate strategically by defining target audience, listening, and developing audience-appropriate messaging | 1 | 0.894 | ||

| Understand the importance of communication at different organizational levels to gain political commitment, policy support, and social acceptance for a health goal or program | 2 | 0.886 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 82.94% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.974 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.917 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| C—Category 3: Performance and achievements | ||||

| Factor analysis, promax rotated matrix for Category 3: Governance and Resource Management domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Design proactively and monitor quality standards and apply quality improvement methods and tools to ensure that quality standards are met | 7 | 0.916 | ||

| Demonstrate knowledge of basic business practices and develop a business plan | 6 | 0.899 | ||

| Use risk management principles and programs | 9 | 0.888 | ||

| Develop descriptions to assure staffing at various organization levels | 4 | 0.869 | ||

| Use key accounting principles and financial management tools | 8 | 0.869 | ||

| Plan the allocation of work tasks to achieve the goals set by the organization | 3 | 0.853 | ||

| Understand and apply the principles of economic thinking in public health | 10 | 0.843 | ||

| Perform health evaluation and assessment of a given procedure, intervention strategy, or policy | 11 | 0.840 | ||

| Conduct hiring interviews and evaluate candidates | 5 | 0.832 | ||

| Apply knowledge of organizational systems, theories, and behaviors to set priorities for resources and achieve clear strategic goals and objectives | 1 | 0.803 | ||

| Manage people effectively by providing clarity on task responsibility, provide training, and give regular feedback on performance | 2 | 0.793 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 73.23% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.963 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.915 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| Professional Development & Reflective Ethical Practice domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Ensure the availability of development opportunities | 5 | 0.950 | ||

| Act and promote evidence-based professional practice | 7 | 0.949 | ||

| Demonstrate an ability to understand and manage conflict-of-interest situations | 6 | 0.947 | ||

| Act according to ethical standards and norms with integrity, and promote professional accountability, social responsibility, and the public health good | 3 | 0.943 | ||

| Demonstrate willingness to pursue learning in public health | 1 | 0.932 | ||

| Address your own development needs based on career goals and required competencies | 2 | 0.931 | ||

| Critically review and evaluate your own practices in relation with public health principles | 4 | 0.900 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 87.65% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.976 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.856 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

| Organizational Literacy and Adaptability domain | ||||

| Factor | Item | Factor 1 | ||

| Demonstrate persistence, perseverance, resilience, and the ability to call on personal resources and energy at time of challenge | 2 | 0.933 | ||

| Show entrepreneurial orientation through proactiveness, innovativeness, and risk-taking, generating potential solutions to critical situations | 3 | 0.914 | ||

| Apply for available funding sources and opportunities | 5 | 0.907 | ||

| Cope with uncertainty and manage work-related stress | 1 | 0.905 | ||

| Respond to call for project applications and grants | 6 | 0.904 | ||

| Adapt to changing professional environments and circumstances | 4 | 0.894 | ||

| Draft tender and project briefs | 7 | 0.882 | ||

| Percentage variance explained | 82.02% | |||

| Cronbach alpha = 0.963 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.918 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001 | ||||

Regarding the “Relations and Interactions” category, the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.920 for the “Leadership and Systems Thinking”, 0.880 for “Collaboration and Partnerships”, and 0.917 for “Communication, Culture, and Advocacy”. For the “Leadership and Systems Thinking”, “Collaboration and Partnerships”, and “Communication, Culture, and Advocacy”, the first factor explained all the variances by 85.04%, 83.88%, and 82.94%, respectively (Table 2B).

Finally, in the “Performance and Achievements” category, the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.915 for “Governance and Resource Management”, 0.856 for “Professional Development and Reflective Ethical Practice”, and 0.918 for “Organizational Literacy and Adaptability”. For the “Governance and Resource Management”, “Professional Development and Reflective Ethical Practice”, and “Organizational Literacy and Adaptability”, the first factor explained all the variances by 73.23%, 87.65%, and 87.02%, respectively. In all categories, Barlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), and Cronbach’s alpha value was higher than 0.9 (Table 2C).

Essential operations in public health

Table 3 describes the perceived level of knowledge for public health essential operations. Most participants declared being knowledgeable of the public health essential operations. Almost half of them (48.5%) considered they had adequate knowledge in assuring sustainable organizational structures and financing.

Table 3.

The level of knowledge for the statement of public health essential operations

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Surveillance of population health and well-being | 42 (63.6%) |

| Monitoring and response to health hazards and emergencies | 41 (62.1%) |

| Health protection, including environmental, occupational, food safety, and other | 46 (69.7%) |

| Health promotion, including action to address social determinants and health inequity | 48 (72.7%) |

| Disease prevention, including early detection of illness | 44 (66.7%) |

| Assuring governance for health and well-being | 39 (59.1%) |

| Assuring a sufficient and competent health workforce | 39 (59.1%) |

| Assuring sustainable organizational structures and financing | 32 (48.5%) |

| Advocacy communication and social mobilization for health | 40 (60.6%) |

| Advancing public health research to inform policy and practice | 44 (66.7%) |

Bivariate analysis

Competency levels between specialties

Table 4 shows the differences in competency levels between all specialties and between public health professionals versus all the others. Overall, graduates with a BS in public health reported a lower competency compared to other specialties in most categories and domains, with percentages varying by 2 to 4 folds.

Table 4.

Differences in the levels of competencies between public health and other specialties

| Public health with BS vs other specialties | All the specialties | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public health with BS degree | Other Specialties | Pharmacist | Nursing | Nutrition | Medicine | Unspecified specialties | p-value between all the specialties and competenciesa | p-value Public health with BS vs other specialtiesa | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Category 1: Content and Context | |||||||||

| Science and Practice domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 20 (90.9%) | 30 (68.2%) | 8 (57.1%) | 5 (71.4%) | 7 (100%) | 1 (50.0%) | 9 (64.3%) | 0.056 | 0.042 |

| High competency | 2 (9.1%) | 14 (31.8%) | 6 (42.9%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 5 (35.7%) | ||

| Promoting Health domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 21 (95.5%) | 28 (63.6%) | 9 (64.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | 7 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (64.3%) | 0.001 | 0.005 |

| High competency | 1 (4.5%) | 16 (36.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (100%) | 5 (35.7%) | ||

| Law, Policies, and Health Security domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 19 (86.4%) | 28 (63.6%) | 9 (64.3%) | 6 (85.7%) | 6 (85.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | 0.036 | 0.055 |

| High competency | 3 (13.6%) | 16 (36.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (100%) | 7 (50.0%) | ||

| One Health and Health Security domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 19 (86.4%) | 31 (70.5%) | 10 (71.4%) | 4 (57.1%) | 6 (85.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (78.6%) | 0.121 | 0.155 |

| High competency | 3 (13.6%) | 13 (29.5%) | 4 (28.6%) | 3 (42.9%) | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (100%) | 3 (21.4%) | ||

| Category 2: Relations and Interactions | |||||||||

| Leadership and Systems Thinking domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 20 (90.9%) | 29 (65.9%) | 11 (78.6%) | 3 (42.9%) | 7 (100%) | 1 (50.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | 0.008 | 0.029 |

| High competency | 2 (9.1%) | 15 (34.1%) | 3 (21.4%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | ||

| Collaboration and Partnerships domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 21 (95.5%) | 25 (56.8%) | 11 (78.6%) | 2 (28.6%) | 6 (85.7%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (42.9%) | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| High competency | 1 (4.5%) | 19 (43.2%) | 3 (21.4%) | 5 (71.4%) | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (100%) | 8 (57.1%) | ||

| Communication, Culture, and Advocacy domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 19 (86.4%) | 28 (63.6%) | 10 (71.4%) | 3 (42.9%) | 7 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 6 (42.9%) | 0.012 | 0.055 |

| High competency | 3 (13.6%) | 16 (36.4%) | 4 (28.6%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (57.1%) | ||

| Category 3: Performance and achievements | |||||||||

| Governance and Resource Management domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 21 (95.5%) | 29 (65.9%) | 10 (71.4%) | 4 (57.1%) | 7 (100%) | 1 (50%) | 7 (50%) | 0.005 | 0.008 |

| High competency | 1 (4.5%) | 15 (34.1%) | 5 (28.6%) | 3 (42.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50%) | 7 (50%) | ||

| Organizational Literacy and Adaptability domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 19 (86.4%) | 25 (56.8%) | 9 (64.3%) | 4 (57.1%) | 5 (71.4%) | 1 (50%) | 6 (42.9%) | 0.103 | 0.016 |

| High competency | 3 (13.6%) | 19 (43.2%) | 5 (35.7%) | 3 (42.9%) | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (50%) | 8 (57.1%) | ||

| Professional Development and Reflective Ethical Practice domain | |||||||||

| Low competency | 20 (90.9%) | 28 (63.6%) | 9 (64.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | 6 (85.7%) | 1 (50%) | 9 (64.3%) | 0.067 | 0.019 |

| High competency | 2 (9.1%) | 16 (36.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 4 (57.1%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (50%) | 5 (35.7%) | ||

aNumbers in bold indicate statistically significant results

In Category 1 (Content and Context), the results showed statistically significant differences between public health versus other specialties in the domains of “Science and Practice” (p = 0.042) and “Promoting Health” (p = 0.005), with the holders of a BS in public health degree declaring being less competent than their counterparts from other specialties. A significant association was found between all specialties and the domains of “Promoting Health” (p = 0.001), where the nursing specialty scored higher than other specialties. In addition, medical doctors showed a higher competency in Law, Policies, and Health Security domain than other health professionals (p = 0.036).

In Category 2 (Relations and Interactions), statistically significant differences in knowledge were found in all domains between all specialties and between public health specialists versus all others (p < 0.05), except for a borderline difference (p = 0.055) when comparing the level of competency in “Communication, Culture, and Advocacy” between public health and other specialties. Public health degree holders declared being less competent than other public health professionals, with nurses being more competent than all others in this domain.

In Category 3 (performance and achievements), the results showed statistically significant differences between public health versus other specialties (p < 0.05), where public health degree holders were also less competent than professionals from other specialties. Medical doctors seemed more competent than other practitioners in the domain of “Governance and Resource Management” (p = 0.005).

However, the results showed non-significant differences in the declared level of competencies in Category 1 (Content and Context), in the domain of “One-Health and Health Security” between all specialties (p = 0.121) and between public health versus all others (p = 0.155).

Feedback on the main competencies needed for public health practice

Table 5 highlights the feedback agreement of the participants on the main competencies needed for public health practitioners based on their experience. The vast majority of participants (90.9%) agreed that “having foundational training in a health discipline” is a priority. Less than half of them (43.9%) considered that “performing intuitively and only occasionally need deliberation” is a priority for public health practitioners.

Table 5.

Feedback of participants agreement on the main competencies that are needed for public health practitioners

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Focus on the central aspects of a problem | 51 (77.3%) |

| Perform intuitively and only occasionally need deliberation | 29 (43.9%) |

| Reflect on how the system works | 57 (86.4%) |

| Assess the quality of the work done in their organization | 59 (89.4%) |

| Assume leadership roles | 53 (80.3%) |

| Develop strategies and assign leadership responsibilities to others | 55 (83.3%) |

| Have substantial authority and responsibility | 56 (84.8%) |

| Supervise multiple tiers of staff | 50 (75.8%) |

| Make decisions via intuition and analytical thinking | 55 (83.3%) |

| See the situation and the interconnectedness of the decisions they make | 58 (87.9%) |

| Have supervisory responsibility | 51 (77.3%) |

| Have foundational training in a health discipline | 60 (90.9%) |

| Rely heavily on their core public health competencies | 53 (80.3%) |

| Recognize that complex work requires non-routine decision-making, to which hard and fast rules do not clearly apply | 51 (77.3%) |

| Supervise smaller groups of staff | 43 (65.2%) |

Multivariate analysis

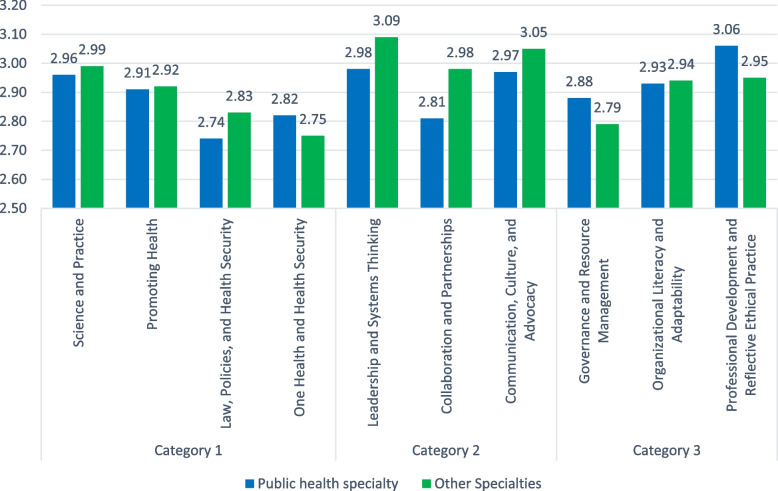

Table 6 shows no significant associations between baseline specialties and self-declared competencies, while the latter were sometimes affected by sociodemographic characteristics (Fig. 1).

Table 6.

Association between the public health competencies score by category and public health specialty vs other specialties

| Beta | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Category 1: Content and Context | ||||

| Science and Practice | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.467 | 0.080 | -0.058 | 0.992 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.082 | 0.721 | -0.543 | 0.379 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.613 | 0.050 | 0.0001 | 1.225 |

| Area of practice academia | -0.211 | 0.286 | -0.603 | 0.181 |

| Area of practice medical setting | -0.104 | 0.532 | -0.434 | 0.227 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | 0.412 | 0.039 | 0.022 | 0.801 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.007 | 0.966 | -0.327 | 0.341 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.049 | 0.784 | -0.305 | 0.403 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | 0.181 | 0.371 | -0.222 | 0.583 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.458 | 0.026 | -0.858 | -0.058 |

| Area of residence North | -0.607 | 0.143 | -1.426 | 0.212 |

| Area of residence South | 0.195 | 0.580 | -0.508 | 0.899 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | 0.195 | 0.689 | -0.780 | 1.170 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | -0.047 | 0.795 | -0.409 | 0.315 |

| Promoting Health | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.637 | 0.042 | 0.024 | 1.251 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.186 | 0.491 | -0.724 | 0.352 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.474 | 0.189 | -0.241 | 1.189 |

| Area of practice academia | 0.038 | 0.868 | -0.420 | 0.496 |

| Area of practice medical setting | 0.083 | 0.668 | -0.303 | 0.469 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | -0.273 | 0.235 | -0.728 | 0.183 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.173 | 0.379 | -0.218 | 0.563 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.099 | 0.633 | -0.314 | 0.512 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | -0.019 | 0.936 | -0.489 | 0.451 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.467 | 0.050 | -0.935 | -0.005 |

| Area of residence North | -0.171 | 0.721 | -1.127 | 0.785 |

| Area of residence South | 0.093 | 0.822 | -0.729 | 0.914 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | 0.006 | 0.992 | -1.133 | 1.145 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | -0.040 | 0.851 | -0.463 | 0.384 |

| Law, Policies, and Health Security | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.360 | 0.215 | -0.216 | 0.935 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.625 | 0.016 | -1.130 | -0.120 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | -0.223 | 0.508 | -0.894 | 0.448 |

| Area of practice academia | 0.147 | 0.496 | -0.283 | 0.576 |

| Area of practice medical setting | -0.118 | 0.515 | -0.480 | 0.244 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | -0.005 | 0.983 | -0.432 | 0.423 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.104 | 0.571 | -0.262 | 0.470 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.457 | 0.022 | 0.069 | 0.845 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | 0.040 | 0.857 | -0.401 | 0.481 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.670 | 0.003 | -1.108 | -0.232 |

| Area of residence North | -0.259 | 0.564 | -1.156 | 0.637 |

| Area of residence South | 0.156 | 0.687 | -0.615 | 0.927 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | 0.005 | 0.993 | -1.064 | 1.073 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | -0.012 | 0.951 | -0.409 | 0.385 |

| One Health and Health Security | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.499 | 0.092 | -0.084 | 1.083 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.215 | 0.403 | -0.727 | 0.297 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.503 | 0.144 | -0.177 | 1.184 |

| Area of practice academia | -0.109 | 0.619 | -0.544 | 0.327 |

| Area of practice medical setting | 0.191 | 0.302 | -0.176 | 0.558 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | -0.150 | 0.492 | -0.583 | 0.284 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.200 | 0.285 | -0.171 | 0.571 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.511 | 0.012 | 0.117 | 0.904 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | -0.130 | 0.562 | -0.577 | 0.317 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.646 | 0.005 | -1.091 | -0.202 |

| Area of residence North | -0.395 | 0.388 | -1.304 | 0.515 |

| Area of residence South | -0.305 | 0.437 | -1.087 | 0.477 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | 0.203 | 0.708 | -0.880 | 1.286 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | 0.077 | 0.702 | -0.326 | 0.480 |

| Category 2: Relations and Interactions | ||||

| Leadership and Systems Thinking | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.527 | 0.090 | -0.084 | 1.138 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.171 | 0.525 | -0.708 | 0.366 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.557 | 0.123 | -0.156 | 1.270 |

| Area of practice academia | -0.428 | 0.065 | -0.884 | 0.028 |

| Area of practice medical setting | -0.327 | 0.094 | -0.712 | 0.057 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | 0.105 | 0.643 | -0.349 | 0.559 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.375 | 0.059 | -0.015 | 0.764 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.163 | 0.432 | -0.250 | 0.575 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | 0.048 | 0.838 | -0.421 | 0.517 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.711 | 0.003 | -1.177 | -0.245 |

| Area of residence North | -1.405 | 0.005 | -2.358 | -0.452 |

| Area of residence South | -0.393 | 0.340 | -1.212 | 0.426 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | 0.241 | 0.671 | -0.894 | 1.376 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | -0.051 | 0.808 | -0.473 | 0.371 |

| Collaboration and Partnerships | ||||

| Gender (females vs malesa | 0.649 | 0.032 | 0.060 | 1.239 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.296 | 0.257 | -0.813 | 0.222 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.104 | 0.763 | -0.584 | 0.792 |

| Area of practice academia | 0.041 | 0.851 | -0.399 | 0.482 |

| Area of practice medical setting | -0.113 | 0.545 | -0.484 | 0.259 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | -0.183 | 0.406 | -0.621 | 0.255 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.325 | 0.089 | -0.051 | 0.700 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.319 | 0.113 | -0.078 | 0.717 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | -0.181 | 0.424 | -0.633 | 0.271 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.491 | 0.033 | -0.941 | -0.042 |

| Area of residence North | -1.037 | 0.028 | -1.956 | -0.117 |

| Area of residence South | 0.035 | 0.930 | -0.756 | 0.825 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | -0.256 | 0.640 | -1.351 | 0.838 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | -0.199 | 0.332 | -0.606 | 0.208 |

| Communication, Culture, and Advocacy | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.773 | 0.011 | 0.184 | 1.361 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.421 | 0.108 | -0.938 | 0.095 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.076 | 0.824 | -0.610 | 0.763 |

| Area of practice academia | -0.121 | 0.581 | -0.561 | 0.318 |

| Area of practice medical setting | -0.110 | 0.554 | -0.480 | 0.260 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | -0.031 | 0.886 | -0.469 | 0.406 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.307 | 0.106 | -0.067 | 0.682 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.104 | 0.600 | -0.292 | 0.501 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | -0.104 | 0.644 | -0.555 | 0.347 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.366 | 0.107 | -0.815 | 0.082 |

| Area of residence North | -1.314 | 0.006 | -2.232 | -0.396 |

| Area of residence South | -0.430 | 0.279 | -1.219 | 0.359 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | 0.305 | 0.577 | -0.788 | 1.398 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | -0.155 | 0.448 | -0.561 | 0.252 |

| Category 3: Performance and achievements | ||||

| Governance and Resource Management | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.458 | 0.142 | -0.159 | 1.075 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.442 | 0.108 | -0.983 | 0.100 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.004 | 0.992 | -0.716 | 0.724 |

| Area of practice academia | -0.200 | 0.387 | -0.661 | 0.260 |

| Area of practice medical setting | -0.112 | 0.566 | -0.500 | 0.277 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | -0.070 | 0.760 | -0.529 | 0.388 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.062 | 0.754 | -0.331 | 0.455 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.368 | 0.082 | -0.048 | 0.784 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | -0.248 | 0.297 | -0.721 | 0.225 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.522 | 0.030 | -0.992 | -0.052 |

| Area of residence North | -0.845 | 0.084 | -1.808 | 0.117 |

| Area of residence South | 0.013 | 0.976 | -0.815 | 0.840 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | 0.540 | 0.349 | -0.606 | 1.686 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | 0.046 | 0.830 | -0.380 | 0.472 |

| Organizational Literacy and Adaptability | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.564 | 0.090 | -0.091 | 1.218 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.118 | 0.682 | -0.692 | 0.456 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.527 | 0.172 | -0.236 | 1.291 |

| Area of practice academia | -0.042 | 0.863 | -0.531 | 0.446 |

| Area of practice medical setting | -0.180 | 0.384 | -0.592 | 0.232 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | -0.026 | 0.914 | -0.512 | 0.460 |

| Area of practice NGO | -0.041 | 0.844 | -0.458 | 0.376 |

| Area of practice MOPH | 0.141 | 0.523 | -0.300 | 0.583 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | -0.267 | 0.291 | -0.768 | 0.235 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.548 | 0.032 | -1.047 | -0.050 |

| Area of residence North | -1.249 | 0.017 | -2.270 | -0.229 |

| Area of residence South | 0.431 | 0.329 | -0.446 | 1.308 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | -0.161 | 0.791 | -1.377 | 1.054 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | -0.012 | 0.958 | -0.464 | 0.440 |

| Professional Development and Reflective Ethical Practice | ||||

| Gender (females vs males) | 0.763 | 0.024 | 0.105 | 1.420 |

| Years of experience (1–5 years) | -0.235 | 0.417 | -0.812 | 0.342 |

| Years of experience (6–10 years) | 0.834 | 0.034 | 0.067 | 1.601 |

| Area of practice academia | -0.210 | 0.395 | -0.700 | 0.281 |

| Area of practice medical setting | -0.232 | 0.265 | -0.646 | 0.182 |

| Area of practice research epidemiology | -0.131 | 0.592 | -0.620 | 0.357 |

| Area of practice NGO | 0.209 | 0.322 | -0.210 | 0.627 |

| Area of practice MOPH | -0.070 | 0.753 | -0.513 | 0.373 |

| Area of practice fresh graduate | -0.312 | 0.220 | -0.815 | 0.192 |

| Area of residence Mont Lebanon | -0.686 | 0.008 | -1.187 | -0.185 |

| Area of residence North | -1.312 | 0.013 | -2.337 | -0.287 |

| Area of residence South | -0.371 | 0.402 | -1.252 | 0.510 |

| Area of residence Bekaa | 0.057 | 0.926 | -1.164 | 1.278 |

| Specialty (public health vs othersa) | 0.140 | 0.539 | -0.314 | 0.593 |

In the global model, the independent variable is “specialty” (public health vs others*). Covariates are gender, years of experience, area of residence and area of practice

aReference group

Fig. 1.

Adjusted means of health competency domains according to the type of specialty (public health vs. other specialties). No significant difference between public health and other specialties in self-declared competency domains with p > 0.05

There were no statistically significant differences between public health practitioners and all others for any of these competencies (p > 0.05 for all).

Category 1 (Content and Context)

Practicing as a research epidemiologist (Beta = 0.412, p = 0.039) was significantly associated with a higher “Science and Practice” score. Female gender (beta = 0.637, p = 0.042) was significantly associated with a higher “Promoting Health” score. Working in the Ministry of Public Health was significantly associated with higher “Law, Policies, and Health Security” (Beta = 0.457, p = 0.022) and higher “One-Health and Health Security” scores (Beta = 0.511, p = 0.012). Having an experience of 1–5 years (Beta = -0.625, p = 0.016) was significantly associated with lower “Law, Policies, and Health Security” scores. Living in Mount Lebanon was significantly associated with lower scores in all Category 1 competencies.

Category 2 (Relations and Interactions)

Participants living in the Mount Lebanon and North regions scored significantly lower in three competencies (Leadership and Systems Thinking, Collaboration and Partnerships, and Communication, Culture, and Advocacy). Female gender was significantly associated with higher “Collaboration and Partnerships” and “Communication, Culture, and Advocacy” scores.

Category 3 (Performance and Achievements)

Living in Mount Lebanon was significantly associated with lower scores in three competencies (Governance and Resource Management, Organizational Literacy and Adaptability, and Professional Development and Reflective Ethical Practice). Also, participants from North Lebanon scored significantly lower on “Organizational Literacy and Adaptability” and “Professional Development and Reflective Ethical Practice”. Being a female (Beta = 0.763, p = 0.024) and having an experience of 6–10 years (Beta = 0.834, p = 0.034) were significantly associated with higher “Professional Development and Reflective Ethical Practice” scores.

Discussion

Our study is the first to validate a tool to assess self-declared public health competencies, namely the WHO-ASPHER framework. The framework comprises three categories, i.e., 1) Content and Context, 2) Relations and Interactions, and 3) Performance and Achievements, each divided into domains that include many items. The factor analysis for scale domains showed that Barlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), high loadings of items on factors, and Cronbach’s alpha values of more than 0.9 in all three categories, indicating appropriate validity and reliability. These results show the possibility of applying a European framework in a developing country, which can be considered an innovation in the Lebanese context in the absence of a national framework. Our results are also close to those of Zwanikken and collaborators, who used Delphi rounds with experts and alumni feedback to validate their framework in low- and middle-income countries [45]; they came up with domains of a different structure than ours, but the content is overall comparable. The WHO-ASPHER framework can thus be used in Lebanon and would also allow benchmarking at the international level.

In Lebanon, the suggested framework would thus allow public health professionals to self-evaluate their proficiency level in different domains and determine the gaps in knowledge that need strengthening. Investment in the public health workforce is more highly mandated now than ever [26, 46, 47]. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted global weaknesses in the health systems against the threat of communicable diseases and disease outbreaks [26, 48]. Consequently, strengthening public health capacity and services has become a global priority [9, 26, 49–51], and the core competencies in the public health framework allow professionals to reach this goal [26] and help identify the essential individual attributes required to fulfill their role [52, 53]. Indeed, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and other academic, governmental and non-governmental institutions emphasized the need to enhance academic preparedness to meet the 21st-century public health challenges [51, 54–62].

The suggested framework would also help stakeholders, such as policy-makers, educational institutions, and public health institutes [26], develop context-specific competency measures to improve education, performance, capacity-building, analysis, and monitoring, in addition to planning and investment [26]. Our study validated the framework to offer an evidence-based, comprehensive template that helps the public health practitioner identify the domains that need strengthening and guides the academic sector to plan a curriculum that meets current and future public health challenges.

Data analysis of the survey showed that the perceived level of competencies was significantly different between the public health professionals and other health professionals with activities in public health. Graduates with public health degrees declared a lower competency level than other health professionals; the latter had variable competency levels in different domains, depending on the health specialty. It is noteworthy that multivariate analysis showed that differences were no longer significant, likely due to the low sample size.

Our findings also revealed that public health core competencies and workforce requirements are not yet well delineated at the national level. All respondents from different educational backgrounds scored low in most public health categories, mainly science and practice. Other studies reported similar results, highlighting the need to call for action to build a public health workforce [56, 63, 64]. Most participants agreed that foundational training in a health discipline is the main competency needed for public health professionals. These findings shed light on the existing capacity and future training requirements to strengthen education tailored to national needs [26].

Studies similar to ours using a formulated framework or survey showed that the main gaps were communication, budgeting and financial planning [29–31], systems thinking [30, 31, 65], policy development [29, 65, 66], and other management skills [29, 31, 65] among surveyed participants. Other gaps included developing a vision for a healthier community [30]. The level of competencies was significantly different between public health professionals and other health professionals with activities in public health. Creating a public health workforce that delivers essential services in all domains of the three core competency categories is critical and challenging at the same time. According to the WHO-ASPHER, professionals are expected to demonstrate a subset of their competencies related to their role [26].

This study offers baseline data to conduct in-depth research across Lebanon, including public health professionals from multiple disciplines and universities with variable levels of expertise and practice in the field. Based on these findings, building a highly-performing Lebanese public health workforce, linking education to practice, and enhancing cross-disciplinary collaboration would help design an academic curriculum for excellence in public health practice. This study also highlighted the importance of setting national guidelines for public health workforce planning and policy-supporting workforce development while addressing the gaps and pitfalls in the field. The guidelines should be tailored to the local requirements to set targeted objectives and plan a joint action based on the adapted WHO-ASPHER framework to the national context. Other countries can benefit from this framework to allow benchmarking, follow-up, and collaborative international action plans for health policy-making to improve competencies in public health.

This study would be the ground for identifying workforce misdistribution, inefficiencies, performance evaluation, and quality assurance to build a workforce for excellence. To reach this point, strategies related to public health education and the workforce are necessary, based on further assessment of the Lebanese context; authorities, academia, professionals, and other stakeholders should join efforts to develop and implement such strategies.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is the first to validate the scale for self-assessment of public health core competencies. It offers a valuable tool for academia and public health professionals to self-assess the level of public health proficiency and orientate continuous education needs for professional development on an individual level while also offering evidenced data for curriculum review and identification of training needs in the academic sector.

The main limitation of this study is the low number of participants per specialty; thus, larger-scale studies are warranted to confirm these descriptive results. The survey was web-based, which may be amenable to sampling and response bias, given in particular that the population of public health professionals is large and unclearly defined. Moreover, when diffusing the questionnaire on social media, most accounts were open; thus, the exact number of potential participants who received the survey link could not be assessed. Respondents were mainly females with one to five years of experience, which hampers the generalizability of the results. Participants self-rated their level of competency in public health services, reflecting their perception only and leading to reporting bias. However, the study design and method used are common to other tool validation studies.

Conclusion

Our study offered a validated tool for academia and public health professionals based on the WHO-ASPHER framework to self-assess the level of public health proficiency and guide continuous education needs for professional development. Data findings also showed variability of self-declared gaps in knowledge and skills, suggesting a need to review the national public health education programs. This study calls for close collaboration between academia and health policy-makers to strengthen public health by addressing national gaps and needs while joining forces with international health organizations to improve the global readiness for future health hurdles.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contribution

PS contributed to the formulation and evolution of overarching research goals and search strategy; PS supervised and coordinated the research activity planning and execution. K.I. wrote the manuscript; CH prepared the figure, PS, KI, AH, CH, MA, RZ, HS contributed to the conception and design of the study, while HS undertook grammar and content editing. All authors read and reviewed the manuscript, critically revised it for intellectual content and approved the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the INSPECT-LB repository, https://inspect-lb.org/assessing-self-reported-core-competencies-of-public-health-practitioners-in-lebanon-using-the-who-aspher-validated-scale-a-pilot-study/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Lebanese International University institutional ethics committee under the number 2020RC-047-LIUSOP. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before filling out the online survey, participants were well informed about the objective of the study and freedom to withdraw at any time. Participants did not receive any financial reward for their participation. The online survey was anonymous and voluntary. An informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Organization, W.H . Health promotion glossary of terms 2021. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization WH. The World Health Report 1998: Life in the 21st century a vision for all, in The world health report 1998: life in the 21st century A vision for all. 1998. p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Healthy people. Available at : https://health.gov/healthypeople. [Last Accessed February 16, 2022]. 2020.

- 4.Organization, W.H., Health21: the health for all policy framework for the WHO European Region. 1999: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

- 5.PAHO . Public health in the Americas: conceptual renewal, performance assessment, and bases for action. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amory, W.C.-E., The untilled field of public health. Mod Med, 1920. 2.

- 7.Marks, L., D. Hunter, and R. Alderslade, Strengthening Public Health capacity and services in Europe. WHO Publ, 2011.

- 8.Martin-Moreno JM, et al. Defining and assessing public health functions: a global analysis. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:335–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foldspang A, Birt CA, Otok R. ASPHER’s European list of core competences for the public health professional. Scand J Public Health Supplement. 2018;23:1–52. doi: 10.1177/1403494818797072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organization, W.H., The world health report 2000: health systems: improving performance. 2000: World Health Organization.

- 11.Peters DH, et al. Job satisfaction and motivation of health workers in public and private sectors: cross-sectional analysis from two Indian states. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willis-Shattuck M, et al. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Organization, W.H., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and The World Bank. Delivering quality health services: a global imperative for universal health coverage, 2018.

- 14.Bhandari S, et al. Identifying core competencies for practicing public health professionals: results from a Delphi exercise in Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1737. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09711-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organization, W.H., Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce. 2016.

- 16.Slawomirski, L., A. Auraaen, and N.S. Klazinga, The economics of patient safety: Strengthening a value-based approach to reducing patient harm at national level. 2017.

- 17.Organization, W.H., Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030. 2016.

- 18.Centre for Workforce Intelligence, Mapping the core public health workforce. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507518/CfWI_Mapping_the_core_public_health_workforce.pdf. [Last Accessed 2 November 2021]. 2014.

- 19.WHO, WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework for the Public Health Workforce in the European Region. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/444576/WHO-ASPHER-Public-Health-Workforce-Europe-eng.pdf. [Last Accessed 2 November, 2021]. 2020.

- 20.Foldspang A. Towards a public health profession: the roles of essential public health operations and lists of competences. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(3):361–362. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Association, P.H., Generic competencies for public health in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Retrieved May, 2007. 20: p. 2010.

- 22.Bialek R. Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice: Bridging the Gap Progress Report, July 1 through September 30. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Government of Canada, Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/public-health-practice/skills-online/core-competencies-public-health-canada.html. [Last Accessed 4 February 2020]. 2021.

- 24.Lee V, National aboriginal and torres strait Islander public health curriculum framework. , et al. Canberra. Australia: Public Health Leadership Network; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.OECD, COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/careers/competency_framework_en.pdf. [Last Accessed 4 February 2020]. 2014.

- 26.Organization, W.H., WHO-ASPHER competency framework for the public health workforce in the European Region. 2021, World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

- 27.Birt, C. and A. Foldspang, European Core Competences for Public Health Professionals (ECCPHP). ASPHER’s European Public Health Core Competences Programme. ASPHER Publication, 2011(5).

- 28.Organization, W.H., Core competencies for public health: a regional framework for the Americas, in Core competencies for public health: a regional framework for the Americas. 2013. [PubMed]

- 29.Grimm BL, et al. Assessing the education and training needs of Nebraska’s public health workforce. Front Public Health. 2015;3:161. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogaert K, et al. Research Full Report: The public health workforce interests and needs survey (PH WINS 2017): An expanded perspective on the state health agency workforce. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(2 Suppl):S16. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor HL, Yeager VA. Core competency gaps among governmental public health employees with and without a formal public health degree. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(1):20–29. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joly BM, et al. A review of public health training needs assessment approaches: opportunities to move forward. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(6):571. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck AJ, Boulton ML. Building an effective workforce: a systematic review of public health workforce literature. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):S6–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dreyfus SE. The five-stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bull Sci Technol Soc. 2004;24(3):177–181. doi: 10.1177/0270467604264992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucey CR, Johnston SC. The transformational effects of COVID-19 on medical education. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1033–1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salas-Vallina A, Ferrer-Franco A, Herrera J. Fostering the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: Shared leadership, social capital, and contagion among health professionals. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020;35(6):1606–1610. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuhlmann, E., G. Dussault, and M. Wismar, Health labour markets and the ‘human face’of the health workforce: resilience beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. The European Journal of Public Health, 2020. 30(Suppl 4): p. iv1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Frenk J, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mjaess G, et al. COVID-19, the economic crisis, and the Beirut blast: what 2020 meant to the Lebanese health-care system. East Mediterr Health J. 2021;27(6):535–537. doi: 10.26719/2021.27.6.535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beaglehole R, Dal Poz MR. Public health workforce: challenges and policy issues. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Apponic, G*Power. Analyze different types of power and compute size with graphics options. Available at: https://g-power.apponic.com/. [Last Accessed 31 October, 2022]. 2022.

- 42.Loewen S, Gonulal T. Advancing quantitative methods in second language research. Routledge; 2015. Exploratory factor analysis and principal components analysis; pp. 182–212. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanyongo GY. Determining the correct number of components to extract from a principal components analysis: a Monte Carlo study of the accuracy of the scree plot. J Mod Appl Stat Methods. 2005;4(1):13. doi: 10.22237/jmasm/1114906380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellis, J.L., Factor analysis and item analysis. Applying Statistics in Behavioural Research, 2017: p. 11–59.

- 45.Zwanikken PA, et al. Validation of public health competencies and impact variables for low-and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riddle, M.C., et al., A lesson from 2020: public health matters for both COVID-19 and diabetes. 2021, Am Diabetes Assoc. p. 8–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.National Academy of Medicine, S., Strengthening Public Health as the Foundation of the Health System and First Line of Defense, in The Neglected Dimension of Global Security: A Framework to Counter Infectious Disease Crises. 2016, National Academies Press (US). [PubMed]

- 48.Gostin LO. The great coronavirus pandemic of 2020–7 critical lessons. JAMA. 2020;324(18):1816–1817. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.18347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Health Organization, European Action Plan for Strengthening Public Health Capacities and Services. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/171770/RC62wd12rev1-Eng.pdf. 2012.

- 50.Public Health England, Public Health Skills and Knowledge Framework as a tool for line managers. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/777202/PHSKF_as_a_tool_for_line_managers.pdf. 2019.

- 51.Wilson, A.N., R. Moodie, and N. Grills, Public health physicians: who are they and why we need more of them-especially in Victoria. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Van Loo J, Semeijn J. Defining and measuring competences: an application to graduate surveys. Qual Quant. 2004;38(3):331–349. doi: 10.1023/B:QUQU.0000031320.86112.88. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Czabanowska K, et al. In search for a public health leadership competency framework to support leadership curriculum–a consensus study. The European Journal of Public Health. 2014;24(5):850–856. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hernandez, L.M., L. Rosenstock, and K. Gebbie, Who will keep the public healthy?: educating public health professionals for the 21st century. 2003: National Academies Press. [PubMed]

- 55.Control, C.f.D., et al., Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 2005: Department of Health & Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for ….

- 56.Zahner SJ, Henriques JB. Public health practice competency improvement among nurses. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5):S352–S359. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warren R, et al. Public health competencies for pharmacists: A scoping review. Pharm Educ. 2021;21:731–758. doi: 10.46542/pe.2021.211.731758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calhoun JG, et al. Development of a core competency model for the master of public health degree. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1598–1607. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koo D, Miner K. Outcome-based workforce development and education in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:253–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Curtis LM, Marx JH. Untapped resources: exploring the need to invest in doctor of public health–degree training and leadership development. Am Public Health Assoc. 2008;98:1547–1549. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roemer MI. Higher education for public health leadership. Int J Health Serv. 1993;23(2):387–400. doi: 10.2190/P3K6-2NQJ-3CLG-ATB8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Calhoun JG, et al. Core competencies for doctoral education in public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):22–29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuhlmann E, et al. A call for action to establish a research agenda for building a future health workforce in Europe. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0333-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Issel LM, et al. Self-reported competency of public health nurses and faculty in Illinois. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23(2):168–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.230208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sellers K, et al. The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey: the first national survey of state health agency employees. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(Suppl 6):S13. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]