Abstract

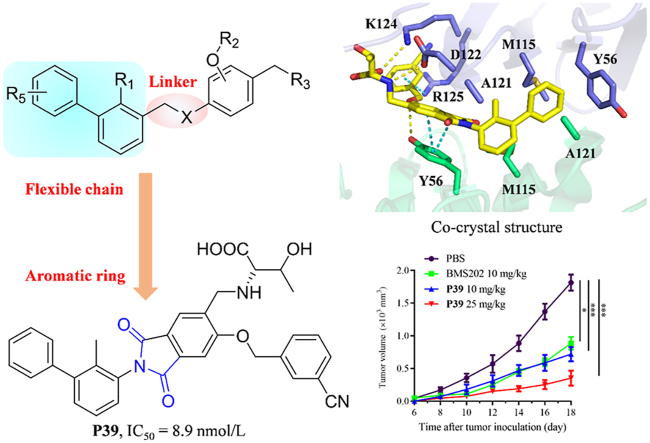

Programmed cell death 1(PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1(PD-L1) have emerged as one of the most promising immune checkpoint targets for cancer immunotherapy. Despite the inherent advantages of small-molecule inhibitors over antibodies, the discovery of small-molecule inhibitors has fallen behind that of antibody drugs. Based on docking studies between small molecule inhibitor and PD-L1 protein, changing the chemical linker of inhibitor from a flexible chain to an aromatic ring may improve its binding capacity to PD-L1 protein, which was not reported before. A series of novel phthalimide derivatives from structure-based rational design was synthesized. P39 was identified as the best inhibitor with promising activity, which not only inhibited PD-1/PD-L1 interaction (IC50 = 8.9 nmol/L), but also enhanced killing efficacy of immune cells on cancer cells. Co-crystal data demonstrated that P39 induced the dimerization of PD-L1 proteins, thereby blocking the binding of PD-1/PD-L1. Moreover, P39 exhibited a favorable safety profile with a LD50 > 5000 mg/kg and showed significant in vivo antitumor activity through promoting CD8+ T cell activation. All these data suggest that P39 acts as a promising small chemical inhibitor against the PD-1/PD-L1 axis and has the potential to improve the immunotherapy efficacy of T-cells.

Key words: PD-1/PD-L1, Small-molecule inhibitor, Immunotherapy, Co-crystal structure

Graphical abstract

Phthalimide derivative P39 induced dimerization of PD-L1 proteins, thereby blocking the binding of PD-1/PD-L1 and inhibiting immune escape of tumor cells.

1. Introduction

After decades of development, immunotherapy regimens have been gradually refined, and in recent years, one of the most rapidly developing treatment regimens is PD-1/PD-L1 therapy1, 2, 3, 4. Immune checkpoints are a series of molecules that are expressed on immune cells and can regulate the activation degree of immune cells. They play an important role in combating autoimmunity and suppressing excessive activation of immune cells, and PD-1/PD-L1 is one of the most important checkpoint molecules5,6. PD-1/PD-L1 regulates the immune system and promotes self-tolerance by down-regulating the immune system's response to human cells and by suppressing T-cell inflammatory activity5,7. Tumor cells can express PD-L1 and achieve immune escape through this mechanism to avoid being killed by T cells8. By inhibiting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, the ability of T cells to attack tumor cells can be restored to cure cancer9.

There are 4 PD-1 antibodies (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab, dostarlimab) and 3 PD-L1 antibodies (avelumab, atezolizumab, and durvalumab) approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical applications10. As an example, the approved indications of pembrolizumab have been increased to 18 types of cancer including and not limited to non-small cell lung cancer, classical Hodgkin lymphoma, head, and neck squamous cell carcinoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma11. Global sales of pembrolizumab and nivolumab reached $14.38 billion and $7.92 billion respectively in 2020. However, antibody drugs have some natural drawbacks, such as poor oral bioavailability, poor permeability of tumor tissues, immune-related adverse events, and high medical costs12,13. One improving strategy is to investigate small molecule PD-L1 inhibitors. After several antibody drugs came to market and showed good efficacy, small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors had become a hot research topic.

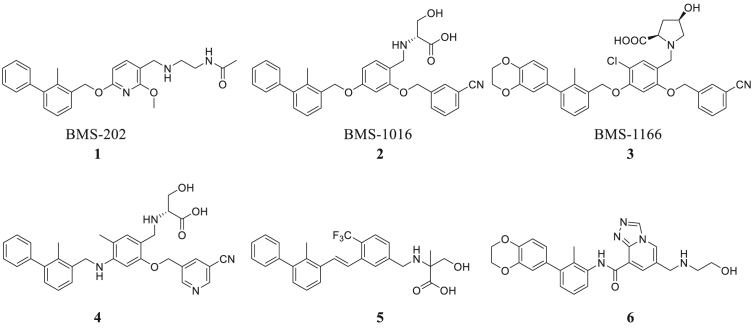

In the past few years, there have been some important advances in this area. The Bristol-Myers Squibb company has discovered a series of biphenyl derivatives14,15 that can lead to dimerization of PD-L1 molecules. Holak's group16,17 has disclosed the co-crystal structures of the complex which provides a very good research basis for subsequent small molecule inhibitor studies. A large number of companies and research institutions are involved in developing novel PD-1/PD-L1 small molecule inhibitors11,13, 14, 15,18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 (Fig. 1), but the vast majority of small molecules are still in preclinical studies. This indicates that druggable small molecule inhibitors are still to be discovered and further exploration is needed to find small molecule inhibitors for clinical use.

Figure 1.

Structures of representative small-molecule inhibitors of PD-1/PD-L1.

In this study, we designed and synthesized novel phthalimide derivatives as small-molecule inhibitors against the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Their structure‒activity relationships were systematically evaluated, and P39 was identified as the most promising leading compound with an IC50 value of 8.9 nmol/L which was assessed by a TR-FRET assay. P39 reduced the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction and enhanced the cytotoxicity of PBMCs against cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner. P39 also showed outstanding in vivo antitumor activity in a MC38 mouse model and a humanized LLC-hPD-L1 tumor model, which was worthy of further evaluation. Notably, this study identified the possibility of replacing flexible chains with aromatic rings as the linker in PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, which was verified by crystal structure and would well guide the subsequent exploration of potential drugs using aromatic rings as the linker.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Drug design

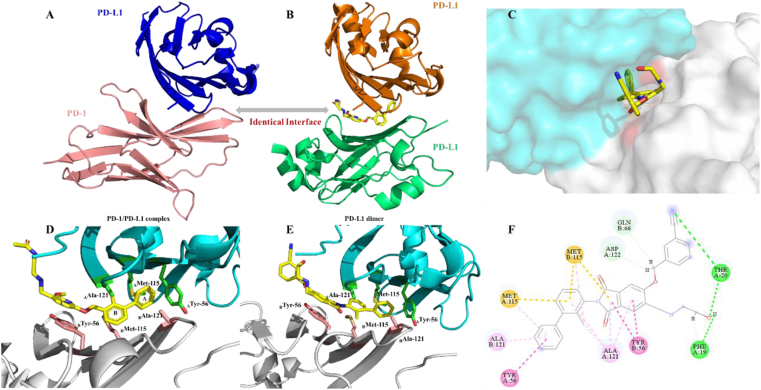

Crystal structure of human PD-1/PD-L1 complex was first reported by Holak in 201516. Three hot spots were recommended and key amino acid residues on the interaction surface of the complexes were disclosed, which included Tyr 56, Glu 58, Arg 113, Met 115, Ala 121, and Tyr 123 on PD-L1. Moreover, this research group determined the co-crystal structure of PD-L1 dimer by using a small molecule (BMS202). It could be found that the binding surface of the PD-L1 dimer (Fig. 2A and B) is overlapping with the PD-1/PD-L1 binding surface17. This is the mechanism of how BMS202 inhibits PD-1/PD-L1 protein‒protein interactions.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of PD-1/PD-L1 complex formation inhibition by small molecule inhibitor. (A) PD-1/PD-L1 interaction (PD-1 shown as the pink cartoon, PD-L1 shown as the blue cartoon, PDB: 4ZQK16). (B) BMS202 (yellow) induced dimerization of PD-L1 (orange, PD-L1; green, PD-L1; PDB: 5J8917). (C) Docking analysis of newly designed leading compound P1 (3D model, cyan, model A; grey, model B). (D) Co-crystal structure of BMS202 and PD-L1 dimer (cyan, model A; grey, model B; PDB: 5J89). (E) Docking analysis of newly designed leading compound P1 (3D model, cyan, model A; grey, model B). (F) Binding conformation of the leading compound P1 in PD-L1/PD-L1 dimer. The π‒π stacking interactions were shown as a red dash line, and hydrogen-bonding interactions were shown as a green dash line.

It is known from the data of molecular docking that biphenyl moiety is necessary for maintaining inhibitory activity17 (Fig. 2D). Ring A would form a T-stacking interaction with the residue ATyr 56, and further stabilized by the sidechains of BAla 121 and AMet 115 through π‒alkyl interactions, and the ring B creates a hydrophobic interaction with AAla 121 and BMet 115. The pyridine ring is involved in π‒π stacking with BTyr 56. These substituents are presumed to be important for maintaining activity and appear in almost all reported small molecules. Ethers are commonly chosen as the linkers and play a limited role in SARs. Replacing the ether linker with a better moiety could create more interactions and is the desired strategy. The co-crystal structure of PD-L1/BMS202 was further analyzed. BTyr 56 would be able to form a π‒π stacking with the linker if replace the linker from the ether moiety into an aromatic ring.

Based on this rational-design strategy, a series of phthalimide derivatives were designed and the docking results were consistent with expectations (Fig. 2E). The molecule docking showed that the newly designed molecule not only retains all the hydrophobic bonds formed by BMS202 with the dimer cavity after replacing the ether bond with the phthalimide ring but also forms strong π‒π stacking with BTyr 56, supporting the correctness of our rational-design strategy.

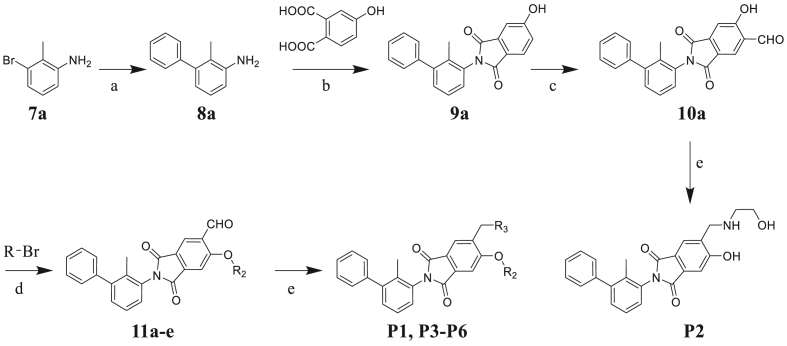

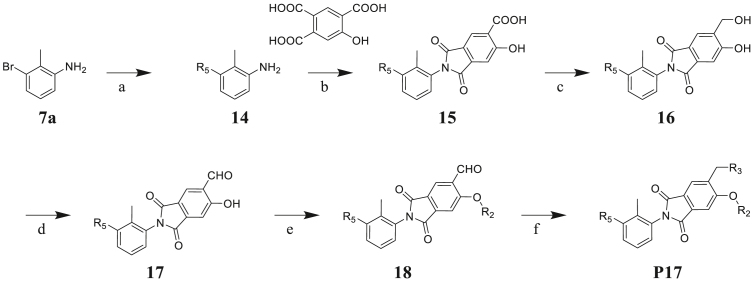

2.2. Chemistry

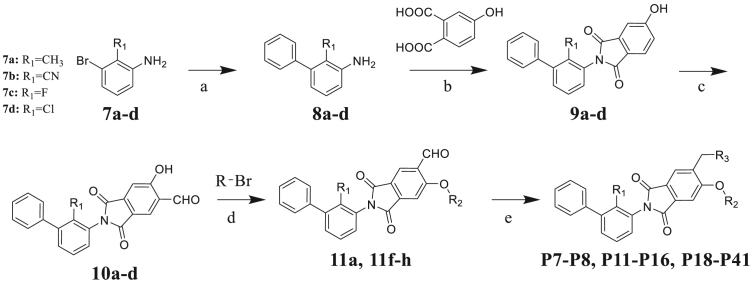

To verify the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity of designed molecules, a series of phthalimide derivatives were synthesized. The synthesis of phthalimide derivatives P1‒P8, P11‒P16, P18‒P41 are described in Scheme 1, Scheme 2. Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of compounds 7a‒d with phenylboronic acid yielded intermediates 8a‒d, respectively. Using acetic acid as the solvent, compounds 8a‒d reacted with 4-hydroxyphthalic acid to yield intermediates 9a‒d. Compounds 9a‒d reacted with hexamethylenetetramine to yield intermediates 10a‒d through a Duff reaction. The etherification of intermediates 10a‒d with the appropriate benzyl bromides provided the intermediates 11a‒h, followed by NaBH(OAc)3-mediated reductive amination with an appropriate amine to yield the final compounds P1, P3‒P8, P11‒P16, P18‒P41. While for target compound P2, intermediate 10a directly reacted with ethanolamine to yield the product.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds P1‒P6. Reagents and condition: (a) phenylboronic acid, Pd(OAc)2, K2CO3, EtOH/H2O (1:1), rt, 14 h, 82%; (b) AcOH, 120 °C, 7 h, 83%; (c) hexamethylenetetramine, CF3COOH, 120 °C, 10 h, 35%; (d) DMF, Cs2CO3, 80 °C, 2 h, 76%–80%; (e) appropriate amine, NaBH(OAc)3, CH2Cl2, rt, 6–10 h, 21%–30%.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds P7‒P8, P11‒P16, and P18‒P41. Reagents and condition: (a) phenylboronic acid, Pd(OAc)2, K2CO3, EtOH/H2O (1:1), rt, 14 h, 79%–82%; (b) AcOH, 120 °C, 7 h, 79%–83%; (c) hexamethylenetetramine, CF3COOH, 120 °C, 10 h, 30%–35%; (d) DMF, Cs2CO3, 80 °C, 2 h, 77%–80%; (e) appropriate amine, NaBH(OAc)3, CH2Cl2, rt, 6–10 h, 21%–69%.

The synthesis of phthalimide derivatives P9‒P10 is described in Scheme 3. Intermediate 12 is a by-product of the reaction that produces intermediate 10a (Scheme 2). Similar to the design of compounds P7‒P8, P11‒P16, and P18‒P41, we conducted a two-step reaction and obtained the target products P9‒P10 to investigate the structure–activity relationship of the R4 substituent.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds P9‒P10. Reagents and condition: (a) hexamethylenetetramine, CF3COOH, 120 °C, 10 h, 10%; (b) DMF, Cs2CO3, 80 °C, 2 h, 75%; (c) appropriate amine, NaBH(OAc)3, CH2Cl2, rt, 6–10 h, 40%–55%.

The synthesis of target compound P17 is described in Scheme 4. The Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction between 7a and phenylboronic acid derivatives provided biphenyl compound 14. Using acetic acid as the solvent, compound 14 reacted with 5-hydroxybenzene-1,2,4-tricarboxylic acid to yield intermediate 15. Followed by reduction and oxidation to yield intermediates 16 and 17. Finally, compound P17 was prepared according to the similar procedure of compound P1 in two steps.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of compounds P41. Reagents and condition: (a) phenylboronic acid derivatives, Pd(OAc)2, K2CO3, EtOH/H2O (1:1), rt, 14 h, 84%; (b) AcOH, 120 °C, 7 h, 72%; (c) BH3·THF, THF, 10 h, rt, 70%; (d) Dess-Martin periodane, CH2Cl2, rt, 2 h, 75%; (e) DMF, Cs2CO3, 80 °C, 2 h, 80%; (f) appropriate amine, NaBH(OAc)3, CH2Cl2, rt, 10 h, 52%.

2.3. Biochemical evaluation and structural optimization

For all the final compounds, the inhibitory activities regulating the PD-1/PD-L1 interactions were evaluated using TR-FRET method.

To verify the effect of the R2 substituent on activity, new derivatives P1‒P6 were designed and further synthesized, and the IC50 values were shown in Table 1 and BMS202 was tested as the positive compound. All six derivatives used ethanolamine as the hydrophilic tail. Based on the docking results between PD-L1 and leading compound P1 in Fig. 2F, the 3-cyanobenzyl group in P1 formed a strong hydrogen bond interaction with the residue AThr 20. To confirm the importance of the 3-cyanobenzyl group as a R3 substituent, we firstly removed it directly and synthesized compound P2. The results indicated that the inhibitory activity of compound P2 was dramatically decreased, which elucidated the important role of the 3-cyanobenzyl substituent. Furthermore, we changed the cyano position on the benzyl ring and synthesized P3‒P4 to explore the influence of the substituent position on the activity. The meta-substituted compound P1 showed the best activity (P1: IC50 = 45.4 nmol/L), while the ortho- and papa-substituted compounds P3 and P4 only showed moderate activities (P3: IC50 = 170.9 nmol/L, and P4: IC50 = 153.1 nmol/L). Meanwhile, if we removed the cyano substituent to get compound P5, its activity was similar to P3 and P4. Also, if we replaced the para-cyano group of compound P4 with a 4-isopropylbenzyl group, its inhibitory activity decreased six folders. All these results indicate that the 3-cyanobenzyl used in compound P1 is the optimal substituent, which will be kept for further modification.

Table 1.

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity of compounds P1‒P6.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Compd. | R2 | IC50 (nmol/L) |

| P1 |  |

45.4 |

| P2 | H | 739.4 |

| P3 |  |

170.9 |

| P4 |  |

153.1 |

| P5 |  |

216.4 |

| P6 |  |

920.7 |

| BMS202 | 17.0 | |

Both the docking study and above SAR results indicate that introduction of the R3 substituent at the 5-position is the preferred design strategy. However, we obtained the intermediate 12 as a by-product during the synthesis of intermediate 10a (Scheme 2, Scheme 3). Therefore, we could obtain target compounds P7 and P8 with 3-R4 substituent instead of 5-R3 at ring C, and the IC50 values were shown in Table 2. Comparing compounds P7/8 with P9/10, the position change of the R3 substituent caused a significant decrease in the activity (P7: IC50 = 45.6 nmol/L vs P9: IC50 = 1141.0 nmol/L), which verifies that the strategy of our rational design is correct. Therefore, we will maintain the 5-R3 substituent in further modification.

Table 2.

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity of compounds P7‒P10.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compd. | R3 | R4 | IC50 (nmol/L) |

| P7 |  |

/ | 45.6 |

| P8 |  |

/ | 52.1 |

| P9 | / |  |

1141.0 |

| P10 | / |  |

4382.0 |

| BMS202 | 17.0 | ||

After exploring the influence of R3 on ring C, we further investigated the effect of R1 on ring B (Table 3). The methyl substituent on ring B was modified to a cyano, fluorine, or chlorine group. Interestingly, all the final compounds showed slightly improved activity (Table 2, Table 3: P11 vs P12, P8 vs P14 vs P16). Although fluoro- or chloro-substituted compounds P16 and P14 showed a little better activity, raw material for methyl-substituted products is the most accessible. Therefore, methyl substituent was selected for the follow-up studies.

Table 3.

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity of compounds P11‒P17.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd. | R1 | R3 | R5 | IC50 (nmol/L) |

| P11 | CH3 |  |

|

117.5 |

| P12 | CN |  |

|

100.0 |

| P13 | Cl |  |

|

39.3 |

| P14 | Cl |  |

|

22.1 |

| P15 | F |  |

|

58.7 |

| P16 | F |  |

|

31.6 |

| P17 | CH3 |  |

|

50.4 |

| BMS202 | 17.0 | |||

Besides keeping R5 as a phenyl ring, R5 was also replaced by a heterocycle benzodioxane group. Although this strategy led to a slightly decreased activity, the inhibitory activity of these two compounds (P7: 45.6 nmol/L vs P17: 50.4 nmol/L) was still at the same level and the synthesis of phenyl derivatization P7 was easier. Therefore, we kept R5 as a phenyl substituent for further modification. Of course, the heterocycle benzodioxane group may be a good direction to improve the physicochemical properties of the target compounds in future studies.

As shown in Table 3, the hydrophilic R3 tail was reported to play an important role in binding with PD-L1 and serve as hydrogen-bond donors21,23. To further investigate the diversity of hydrophilic substituents R3, a series of new derivatives with a chain or cyclic hydrophilic tail were designed and synthesized, including ester groups, alcohol groups, amide groups, and carboxyl groups (Table 4). Among these newly designed compounds, P22‒P27 bearing a cyclic substituent showed weaker activities when compared with compounds P18‒P21 with a chain tail. This indicates that a R3 chain tail may be a better choice for further modification. Meanwhile, replacing the hydroxyl group with a carboxyl group greatly improved the activity (P25 vs P27). Therefore, we further introduced the chain tail with a carboxyl group into the new derivatives and explored their structure-activity relationship. This strategy offered us a series of new compounds (P30, P33, P35, P37, and P39), which exhibited activities of great improvements. Especially, compound P39 exhibited the best IC50 value of 8.9 nmol/L. While we converted the carboxyl acid group to different ester groups (P31, P32, P34, P36, P38, and P40), their activities were remarkably decreased. This result further confirmed that the carboxyl acid group played a critical role to maintain the favorable activity.

Table 4.

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity of compounds P18‒P41.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd. | R3 | IC50 (nmol/L) | Compd. | R3 | IC50 (nmol/L) |

| P18 |  |

79.1 | P31 |  |

835.8 |

| P19 |  |

150.4 | P32 |  |

1155.0 |

| P20 |  |

395.4 | P33 |  |

13.3 |

| P21 |  |

188.9 | P34 |  |

>10,000 |

| P22 |  |

250.7 | P35 |  |

46.6 |

| P23 |  |

216.1 | P36 |  |

1667.0 |

| P24 |  |

738.1 | P37 |  |

11.6 |

| P25 |  |

187.4 | P38 |  |

>10,000 |

| P26 |  |

563.7 | P39 |  |

8.9 |

| P27 |  |

42.4 | P40 |  |

1686.0 |

| P28 |  |

867.4 | P41 |  |

527.1 |

| P29 |  |

607.0 | BMS202 | 17.0 | |

| P30 |  |

14.0 | |||

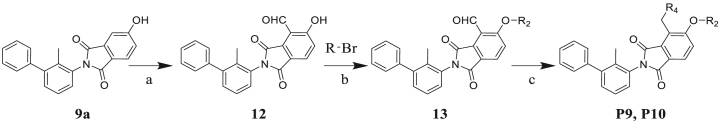

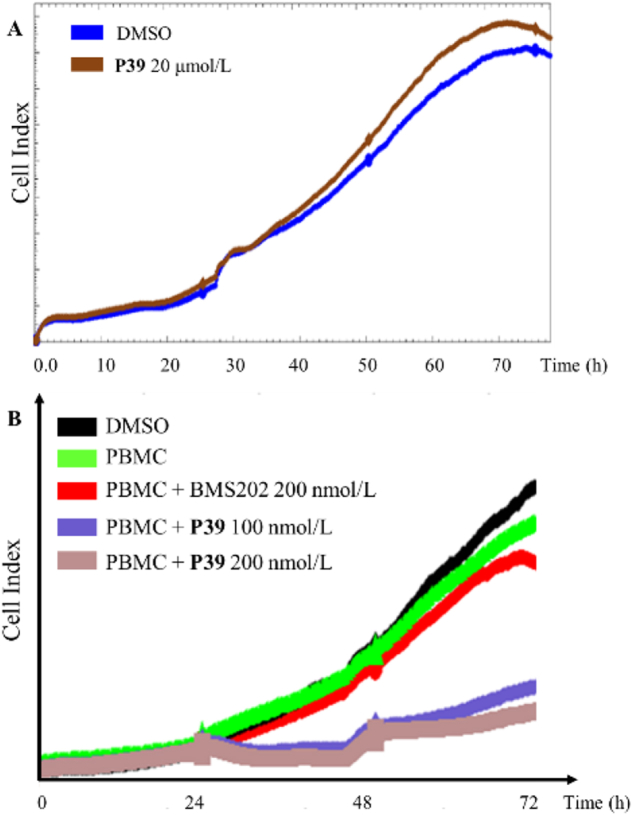

2.4. Cytotoxicity evaluation

When developing a small molecule PD-L1 immuno-oncology agent, we hope that its inhibitory activity on cancer cells is derived from the regulation of T-cell function rather than the cytotoxicity of the inhibitor. To evaluate the cytotoxicity of these new compounds, 10 representative compounds (P1, P3, P4, P8, P15, P17, P30, P33, P37, and P39) were chosen and tested using the Real-Time Cell Analyzing (RTCA) method. A375 cells were treated with 20 μmol/L of the selected compound. As illustrated in Fig. 3A and Supporting Information Fig. S1, real-time growth of A375 cells was measured and found to be almost identical between the experimental and control groups, demonstrating that these compounds were essentially non-toxic to A375 cells. Therefore, the cytotoxicity effects can be excluded in the subsequent cellular assays and in vivo antitumor experiments.

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity effect of P39 on tumor cell and killing effect of human PBMCs toward H460 cells. (A) Treated with different concentrations of P39, cell viability in A375 cells was measured using the xCELLigence system. (B) Cell impedance test was used to examine the killing effects of human PBMCs on H460 cells after treated with P39 (100 or 200 nmol/L) for 24 h.

2.5. Binding affinity of P39 to PD-L1

Considering the inhibitory action of PD-1/PD-L1 and cellular cytotoxicity, compound P39 was chosen as the top candidate and its binding affinity to hPD-L1 was further analyzed using microscale thermophoresis (MST) method. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S3, the KD value for compound P39 binding to hPD-L1 was 24.4 ± 0.02 nmol/L, while the KD value for positive control compound BMS202 was 134.8 ± 0.10 nmol/L. It indicated that compound P39 exhibited a strong binding affinity with human PD-L1 protein than BMS202.

2.6. P39 reduces PD-1/PD-L1 interaction and increases PBMC cytotoxicity

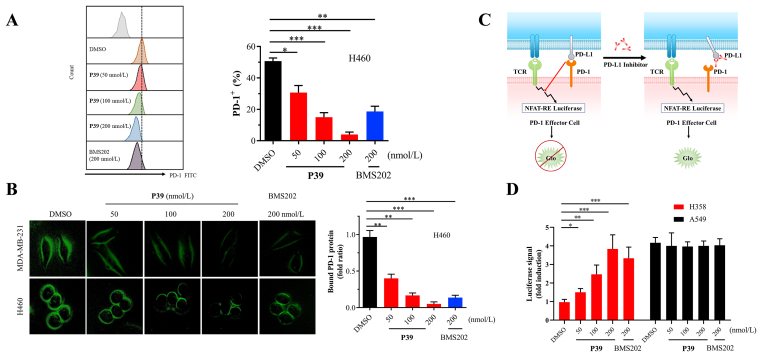

Based on the above experimental results, compound P39 was shown to have a high affinity for PD-L1 protein and blocked the protein interaction of PD-1/PD-L1. To assess its inhibitory activity on tumor cells, further cellular assays were performed. It was established that PD-L1 on tumor cells would bind to the homologous receptor PD-1 on tumor-infiltrating T cells thus inhibiting their antitumor activity28. To confirm whether P39 would influence the protein interaction of PD-1 and PD-L1, tumor cells pretreated with P39 were cultivated with recombinant human PD-1 Fc. A diminished fluorescent signal indicates the decreased interaction between PD-1 and PD-L129. It was found that the binding capacity of PD-1 to H460 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells was significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner after treatment with P39. At a concentration of 200 nmol/L, compound P39 showed a stronger inhibitory activity compared to the positive compound BMS202 (Fig. 4A and B). Moreover, PD-1/PD-L1 blockade bioassay30 (Fig. 4C and D) also showed the significant increase of transcriptional-mediated bioluminescent signal in P39-treated H358 cells in a concentration-dependent manner compared to untreated cells. A549 cells with very low PD-L1 expression served as a positive control. Luciferase signal increases when the protein interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 is blocked. These results suggested that P39 could block the interaction of PD-1/PD-L1, thereby inhibiting the checkpoint activity of PD-L1.

Figure 4.

P39 attenuates PD-1/PD-L1 interaction and strengthens the cytotoxicity of PBMCs. (A) Binding of PD-1 to H460 cells, which were treated with the indicated dose of P39 for 24 h, was measured by flow cytometry. The Y-axis shows the mean fluorescence intensity of PD-1. (B) After treatment with P39 (0–200 nmol/L, 24 h) on the MDA-MB-231 and H460 cells, the changes in immunostaining were monitored. The green fluorescence intensity indicates the binding of PD-1 to tumor cells. (C) Addition anti-PD-L1 inhibitor that interfered with the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction results in NFAT-RE-mediated luminescence. (D) Interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 between Jurkat NFAT-luciferase reporter cells and P39-treated A549 or H358 cells were measured using the PD-1/PD-L1 blockade assay. Data are shown as fold induction compared to untreated controls.

Furthermore, cell impedance assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of activated human PBMCs against co-cultured cancer cells. Consistently, P39 greatly increased the sensitivity of tumor cells to T cell killing, and showed a stronger killing ability compare to the BMS202 group (Fig. 3B). In conclusion, all these results suggest that P39 blocked the interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 and improved the immune killing ability of PBMCs against cancer cells.

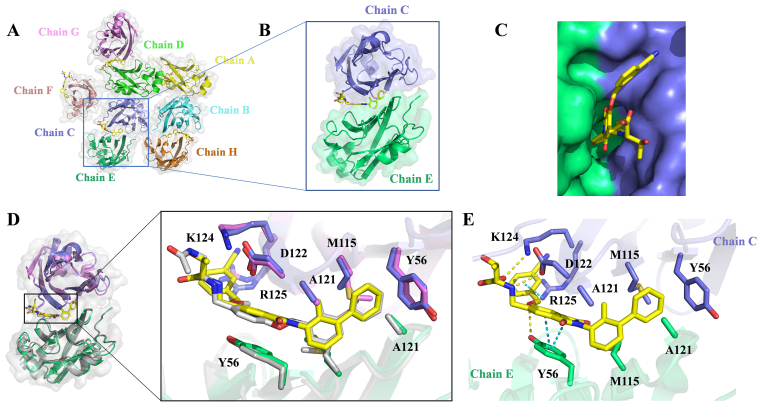

2.7. Structural basis for the interaction between P39 and PD-L1 protein

Crystals of the PD-L1/P39 complex diffracted to 2.7 Å resolution (Supporting Information Table S1). The asymmetric unit contains eight molecules of PD-L1. Six molecules form three dimers and the other two molecules form two dimers with molecules from neighboring asymmetric unit, respectively (Fig. 5A). The interface of each dimer contains one inhibitor, which forms a cylindrical hydrophobic pocket (Fig. 5B and C). This interaction mode of PD-L1 with P39 is in high agreement with the previous computer-aided drug design (CADD) results, and all hydrophobic bond formation is consistent with the calculated results. The ring A of compound P39 forms T-stacking interactions with the side chain CTyr 56 and additional π‒δ and π‒alkyl interactions with EAla 121 and CMet 115, respectively. Ring B is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions with CAla 121 and EMet 115. Both ring C and the phthalimide ring form π‒π stacking with ETyr 56, which is consistent with the computational design. By adding the phthalimide ring, the small molecule inhibitor forms a stronger hydrophobic interaction with the PD-L1 dimer, which helps stabilize the binding of the inhibitor to the dimer. In addition, 3-cyanobenzyl in the tail of P39 forms π‒cation interaction with CArg 125. The tails of compound P39 form a hydrogen bond with CAsp 122, CLys 124, and ETry 56, respectively, which greatly enhances the interaction of the inhibitor with the PD-L1 dimer (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Co-crystal structure of PD-L1/P39 complex. (A) Each asymmetric unit contains eight PD-L1 molecules (mixed ribbon/surface representation). Six molecules form three dimers and the other two molecules form two dimers with molecules from the other unit, respectively. (B) Structure of a single dimer, color coding as in Fig. 5A. (C) The small-molecule inhibitor P39 is embedded in a hydrophobic cavity formed by the PD-L1 dimer. (D) Overlay of the PD-L1/P39 and PD-L1/BMS202 dimer (PDB ID: 5J89). Both P39 (yellow) and BMS202 (gray) induce the PD-L1 dimerization and form a similar binding pocket (PD-L1/P39 complex: slate and green, PD-L1/BMS202 complex: violet and grey). (E) Detailed interaction of the inhibitor P39 with key amino acid residues of the PD-L1 dimer.

Comparison of the co-crystal structures of PD-L1/P39 complex and PD-L1/BMS202 complex (PDB ID: 5J89) revealed no significant displacement of key amino acid residues for the interaction of the two inhibitors and PD-L1 dimer (Fig. 5D), which suggested that changing the linker chain from a flexible chain to an aromatic heterocyclic may not result in significant change in protein conformation.

2.8. In vivo antitumor activity of compound P39

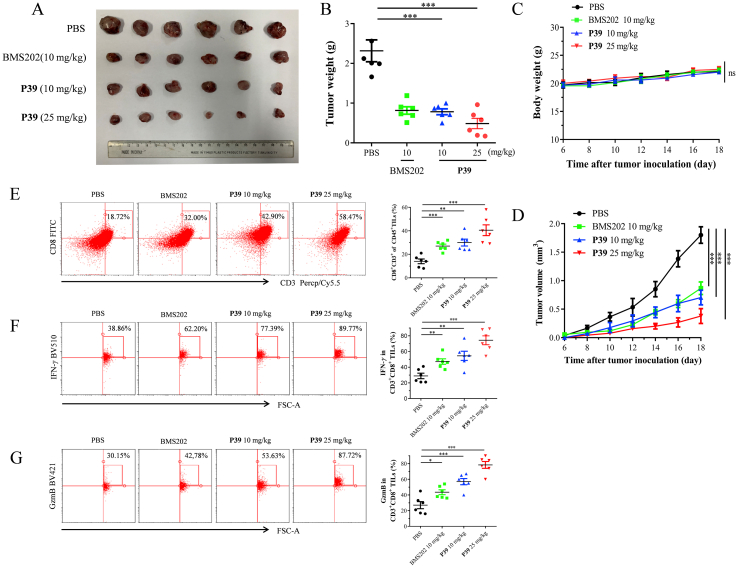

Prior to the in vivo efficacy evaluation experiments, acute toxicity experiments and pharmacokinetic (PK) experiments were performed to assess the safety properties of P39 and to define the appropriate mode of administration. Oral administration of P39 at a single dose of 5000 mg/kg for two weeks showed no mortality and obvious body weight loss, which proved that compound P39 had a favorable safety profile (Supporting Information Fig. S4). We evaluated the PK properties of P39 using SD rats, which showed hopeful PK properties included acceptable t1/2 and AUC by injectable administration (Supporting Information Table S2). However, the low oral bioavailability (F%) was similar to the reported compounds. These results guided us to use intraperitoneal injection for the in vivo evaluation, while not oral administration. A MC38 mouse model in C57BL/6 mice was used to assess the in vivo antitumor efficacy of top compound P39. After the tumor volume reached 100 mm3, the mice were divided equally into three groups, a blank control group and two experimental groups (dosages: 10 and 25 mg/kg). Compound P39 was administered by intraperitoneal injection once daily for 4 weeks. The tumor growth inhibition of the different groups was shown in Fig. S5A. Compound P39 inhibited tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner. After 4 weeks of administration with a low and high dosage of P39, the tumor volume growth inhibition was 54.9% and 68.3%, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. S5C). No weight loss or death of mice occurred during treatment (Fig. S5B), consistent with the acute toxicity assay, and the mice were well tolerated to compound P39. Compared with the control group, two P39-treated groups significantly decreased the final tumor weight (Fig. S5D). All these results indicate that compound P39 exhibited desired in vivo antitumor activity and safety profile as a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor. To further validate the in vivo antitumor efficacy of P39, the therapeutic effect of P39 was evaluated with a humanized mouse model (hPD-1-knockin C57BL/6 mice bearing Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells overexpressing hPD-L1 (LLC-hPD-L1)). Additionally, BMS202 was used as the control compound and the other test parameters were consistent with previous experiments (Fig. 6A‒D). P39 is a small molecule inhibitor designed based on the human PD-L1 protein, and the results assessed on a humanized mouse model would theoretically provide a better reflection of its effect on human. P39 showed similar tumor inhibitory effect as the control BMS202 at 10 mg/kg, while exhibited much better activity at 25 mg/kg. After 12 days of administration, the tumor inhibition rate in the high dose administration group reached 79.0%. Nude mice experiments were completed to demonstrate the ability of P39 to kill tumor cells in immunodeficient mice. The results showed that without the support of immune cells, P39 had no ability to clear tumor cells (Supporting Information Fig. S7). All these results demonstrated the great potential of P39 as a drug candidate for follow-up studies.

Figure 6.

In vivo antitumor activity of P39. hPD-1-knockin C57BL/6 mice bearing Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells overexpressing hPD-L1 (LLC-hPD-L1) were treated with PBS, BMS202 (10 mg/kg) and P39 (10 and 25 mg/kg). The tumor growth was monitored (n = 6). (A) Ex vivo observation of the tumors from the treated mice. (B) Comparison of the weight of the tumors from the mice treated with PBS, BMS202 or P39. (C) Body weight of the treated mice was measured every 2 days. (D) Tumor volume was measured every 2 days. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of infiltrating CD8+ T cells (n = 6) frequency in BMS202 or P39 treated mice. (F and G) Flow cytometry detecting the IFN-γ (F) and GzmB level (G) in CD3+ CD8+ TILs from PBS, BMS202 or P39 treated tumors (n = 6). Data shown are mean value ± standard error of mean (SEM). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ns, no significant.

2.9. P39 enhances infiltration of CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues

To demonstrate compound P39-mediated antitumor T-cell immunity on two mouse models, we collected tumor tissues from mice treated with vehicle or P39 and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were analyzed. We observed a significant increase in T cell population in TILs (Fig. 6E). The ratio of CD8+ to CD3+ T cells was greatly increased in the tumor of P39-treated mice (Supporting Information Fig. S6B and 6E), which indicated that P39 enhanced the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues and improved tumor immune response. In addition, the population of CD4+ T cells in the tumor tissue of mice treated with P39 did not change compared to the control group (Fig. S6C). Two important cytokines were detected. IFN-γ and GzmB levels in CD8+ T-cells were measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 6F and G), which showed that P39 significantly activated the antitumor activity of CD8+T cells. IHC experiments also demonstrated that P39 led to increased expression of CD8, IFN-γ, and GzmB (Supporting Information Fig. S8).

3. Conclusions

In the present study, a series of phthalimide derivatives were rationally designed and synthesized based on the binding model of PD-1/PD-L1 with BMS202. The possibility of replacing the flexible ether chain with a rigid aromatic ring as a linker to enhance the binding strength to PD-L1 protein was further explored via systematic structure‒activity relationship studies. Most of the new derivatives exhibited strong inhibitory ability to block the protein interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1. Among them, P39 was the most promising small-molecule inhibitor with an IC50 value of 8.9 nmol/L. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity evaluation demonstrated that these compounds were essentially non-toxic to cancer cells. Via in vitro studies of inhibitory activity and cytotoxicity, P39 was confirmed as the top candidate for further evaluations.

Subsequently, a series of cellular assays indicated that P39 significantly inhibited the PD-1/PD-L1 protein interaction and improved the cytotoxicity of PBMCs toward cancer cells. Co-crystal experiments revealed the binding mode of P39 to PD-L1 protein, which indicated that the newly designed phthalimide ring could form an additional π‒π stacking with Tyr 56, greatly contributing to a stable binding to the PD-L1 dimer. These results provided valuable information to guide the chemical modification of novel PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Meanwhile, the acute toxicity assay was conducted with oral administration of P39 at four different dosages. No mortality and obvious bodyweight loss were observed even at the high dose of 5000 mg/kg, which showed the excellent safety profile of P39. Intraperitoneal injection of P39 significantly inhibited the proliferation of MC38 tumor cells in vivo in a dose-dependent manner. In MC38 mouse model, the inhibition rate of tumor growth in the low dose of 10 mg/kg group was 54.9% after four weeks of treatment with P39, while the inhibition rate in the high dose of 25 mg/kg group was increased to 68.3%. While in the LLC-hPD-L1 mouse model, the inhibition rate of tumor growth in the low and high dose group were 66.2% and 79.0% respectively, which indicated that P39 has significant in vivo antitumor activity. Furthermore, the flow cytometry experiment demonstrated the antitumor mechanism of P39 via enhancing the activity of immune cells towards tumor cells. Overall, this study discovered P39 as a promising candidate to develop novel antitumor drugs against the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, and also provided valuable guiding information for further chemical modification.

4. Experimental

4.1. Cell culture

A549, H358, H460, and MDA-MB-231, as well as Jurkat (E6-1) cells were all obtained from the Institute of Basic Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). PBMCs were purchased from StemEry Biotech (Fuzhou, China). Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

4.2. Docking method

The co-crystal structure of human PD-L1 dimer and BMS202 (PDB code: 5J89) was downloaded from protein data bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/). Discovery Studio 2021 (DS2021, Accelrys, CA, USA) was used as the docking program. Following the protocol of DS2021, the protein was prepared. Compound P39 was prepared and docked via the LibDock mode. PyMOL software was used to generate images.

4.3. TR-FRET assay

The TR-FRET assay was used to measure the IC50 value of synthesized compounds. Dye-labeled acceptor, PD-1-Eu, and PD-L1 biotin were purchased from BPS Bioscience. Following the instructions of the manufacture, the TR-FRET assay was performed to measure the inhibition activities of all compounds. In brief, the solution of the dye-labeled acceptor, PD-1-Eu, and PD-L1 biotin with a suitable concentration was prepared at first. Then, 5 μL of PD-L1-biotin and 5 μL of the target compound were added and incubated for 15 min at rt. Subsequently, 5 μL of PD-1-Eu and 5 μL of dye-labeled acceptor were added to reach a total 20 μL volume, which was then incubated at rt. The fluorescent intensity was read with EnVision multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer). Data analysis was performed using the TR-FRET ratio (665 nm emission/620 nm emission). The IC50 values were calculated with GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

4.4. Cytotoxicity evaluation

According to our previous report30, the cytotoxicity of P39 on the tumor cells was evaluated using the xCELLigence system (Agilent) and the results were analyzed with RTCA Software.

4.5. Binding affinity

The binding affinity of the compound P39 with hPD-L1 ligand-binding domain was analyzed by microscale thermophoresis (MST). Purified hPD-L1 ligand-binding domain was labeled with the Monolith RED-NHS 2nd Generation protein labeling kit (Nano Temper Technologies). Serially diluted compounds, with concentrations of 10 to 0.0006 μmol/L, were mixed with a constant labeled hPD-L1 ligand-binding domain at room temperature in assay buffer (10 mmol/L HEPES pH 8.5, 20 mmol/L NaCl) and loaded into Monolith standard-treated capillaries. The MST measurement was performed on a Monolith NT.115 instrument (Nano Temper Technologies) at a constant LED power and varying microscale thermophoresis power of 20%, 40%, and 80%. KD values were fitted using MO. Affinity Analysis v2.2.4. software (Nano Temper Technologies).

4.6. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade bioassay

The interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 between Jurkat NFAT-luciferase reporter cells and PD-L1 antibody-treated A549 or H358 cells has been validated previously (Fig. S2). P39 mediated functional changes in PD-1/PD-L1 interaction were examined using the blockade Assay Kit (Promega, J1250) as described before30,31. The results were analyzed using ICE software.

4.7. PD-L1/PD-1 interaction assay

To explore the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction, H460 cells or MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with P39 (0–200 nmol/L) followed by incubation with recombinant human PD-1 Fc (Peprotech, 310-40) and anti-human Alexa Fluor 488 dye conjugated (Abcam, ab97003). Microscope (Zeiss Axio Vert A1, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) was used to capture green fluorescence signals. Novocyte flow cytometer (Agilent) was utilized to conduct quantitative analysis.

4.8. PBMCs-mediated tumor cell-killing assay

According to the previous report30, PBMCs-mediated tumor cell-killing assay was carried out using the xCELLigence system (Agilent).

4.9. Acute toxicity test

To evaluate the safety of compound P39 in vivo, 40 ICR mice were randomly divided into 5 groups (8 mice in each group), which included a control group and four experimental group (500, 1000, 2500, and 5000 mg/kg). The body weight of each mouse is 18–22 g. Mice were observed for 14 days after a single dose, symptoms of poisoning and death were recorded and dead animals were examined post-mortem. The body weight was weighed at the end of the experiment, and after the mice were sacrificed, the organ weights were weighed.

4.10. Protein expression and purification

The method to express and purify human PD-L1 protein (residues 18–134, C-terminal His tag) were described as previously32. In brief, the Escherichia coli strain BL21 was cultured, and inclusion bodies were collected, washed, and dissolved. A solubilized fraction was clarified by centrifugation and refolded by drop-wise dilution. And then, the protein was dialyzed and purified by size exclusion chromatography in buffer (pH 8.5, 10 mmol/L Tris, 20 mmol/L NaCl). The purity was evaluated by SDS-PAGE.

4.11. Crystallization of the complex of hPD-L1 with small molecule inhibitor

The hPD-L1 was purified in buffer (pH 8.5, 10 mmol/L Tris, 20 mmol/L NaCl) and mixed with small-molecule P39 at a 1:2 mol/L ratio. The PD-L1/P39 complex was concentrated to 8.5 mg/mL, and commercially available sets of conditions (Hampton Research, Rigaku, Molecular Dimensions) were used to screen with the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method, and 0.1 mol/L Tris, pH 7.5, 2% 1,4-dioxane, 17% PEG 3350 were used to make diffraction-quality crystals at 16 °C.

4.12. Determination and refinement of co-crystal structure

After cryoprotection, the crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The diffraction measurements were taken at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) BL19U beamline. XDS33 was used to index and integrate the data. Scala34 was used to scale and merge the data. Phaser35 was used to calculate molecular replacement and the PDB ID of a search model was 5C3T. Coot36 was used to build the protein model. Phenix37 or Refmac 5.038 was used to perform restrain refinement. The final model was deposited in the PDB with accession number 7VUN.

4.13. In vivo antitumor activity study

All animal experiment protocols and operations followed the guiding principles of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the China Pharmaceutical University. C57BL/6 mice (female, 4 weeks old) were purchased from Slac Laboratory Animal Technology (Shanghai, China). A MC38 mouse model was established by subcutaneously implanting 1 × 106 MC38 cells into the right flank of each mouse. The mice were randomly assigned into vehicle control and P39-treated groups (7 mice in each group) when the tumors reached a volume of 100 mm3. Mice were treated with vehicle control and P39 (dosages: 10 and 25 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection once a day for 28 days. The tumor volume and body weight were recorded and calculated with formula 0.5 × length (mm) × width (mm) × width (mm). On Day 28, the mice were sacrificed, and tumors were excised and weighed. Tumor growth inhibition (TGI) rates were calculated with Eq. (1):

| TGI (%) = [1‒Vt/Vv] × 100 | (1) |

where Vt presents tumor volumes of the treatment group, Vv, tumor volumes of vehicle control.

hPD-1-knockin C57BL/6 (6- to 8-week-old females, GemPharmatech, Nanjing, China) were conducted under guidelines approved by the animal ethics committee of the Institute of Medicinal Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. An LLC-hPD-L1 mouse model was established by subcutaneously implanting 1 × 106 Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells (overexpressing hPD-L1) into the right flank of each mouse. The other procedures were similar to the MC38 mouse model.

Balb/c-nude mice mouse model (6- to 8-week-old females, Beijing HFK bioscience, Beijing, China) was established by subcutaneously implanting 1 × 106 Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells (overexpressing hPD-L1) into the right flank of each mouse. The other procedures were similar to the MC38 mouse model.

4.14. Flow cytometry

Tumors tissues from vehicle or P39 group (dosages: 10 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg) were collected and digested to single cells. Then single cells were collected and washed three times using PBS. Suspension cells were blocked using anti-CD16/CD32 antibodies and stained with fixable viability dye. Antibodies CD45 (Biolegend, 157,605/103,113), CD3 (Biolegend, 100,217/100,203), CD8 (Biolegend, 140,403/100,721), CD4 (Biolegend, 116,005/100,407), IFN-γ (Biolegend, 505,841) and GranzymeB (Biolegend, 396,413) were used to stain cells in the dark for 30 min in the condition of 4 °C. Cell staining buffer (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to wash the cells three times and quantitative analysis was performed with BECKMAN COULTER CytoFLEX and Guava easy Cyte (Luminex, USA).

4.15. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

For IHC, tumor tissues were fixed in fresh 10% formaldehyde and cut to 4-μm thick paraffin sections. After incubated with primary antibodies against CD8, IFN-γ and granzyme B (1:300) for the determination of relative protein expression, PBS was used to replace the primary antibody for the negative control. The slides were probed with an HRP-labeled secondary antibody for 30 min. Subsequently, these slides were counterstained with DAB. Images were obtained using fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss, Axio Vert. A1).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073701, 31900687, 81973366), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK2019040713, China), and the Project Program of State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, China Pharmaceutical University (SKLNMZZ202013, China). This study was also supported by Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Drug Design and Optimization, China Pharmaceutical University (No. 2020KFKT-5, China), the “Double First-Class” University Project (CPU2018GF04, China), and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2021-I2M-1-070). The X-ray data were collected at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF, China) BL19U beamline.

Author contributions

Project design: Peng Yang; Medicinal chemistry: Chengliang Sun, Gefei Wang; Bio-test: Xiaojia Liu; Co-crystal structure: Yao Cheng; CADD: Wenjian Min; Writing and review: All; Study supervision and funding: Hongbin Deng, Yibei Xiao and Peng Yang.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.04.007.

Contributor Information

Hongbin Deng, Email: hdeng@imb.pumc.edu.cn.

Yibei Xiao, Email: yibei.xiao@cpu.edu.cn.

Peng Yang, Email: pengyang@cpu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Dunn G.P., Bruce A.T., Ikeda H., Old L.J., Schreiber R.D. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellman I., Coukos G., Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature. 2011;480:480–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen D.S., Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2013;342:1432–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardoll D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J., Hu L. Immunomodulators targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 protein‒protein interaction: from antibodies to small molecules. Med Res Rev. 2019;39:265–301. doi: 10.1002/med.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura H., Nose M., Hiai H., Minato N., Honjo T. Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity. 1999;11:141–151. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J.Y., Lee H.T., Shin W., Chae J., Choi J., Kim S.H., et al. Structural basis of checkpoint blockade by monoclonal antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13354. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X., Pan X., Zhang W., Guo H., Cheng S., He Q., et al. Epigenetic strategies synergize with PD-L1/PD-1 targeted cancer immunotherapies to enhance antitumor responses. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin X., Lu X., Luo G., Xiang H. Progress in PD-1/PD-L1 pathway inhibitors: from biomacromolecules to small molecules. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;186:111876. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.OuYang Y., Gao J., Zhao L., Lu J., Zhong H., Tang H., et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of o-(biphenyl-3-ylmethoxy)nitrophenyl derivatives as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with potent anticancer efficacy in vivo. J Med Chem. 2021;64:7646–7666. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasikumar P.G., Ramachandra R.K., Adurthi S., Dhudashiya A.A., Vadlamani S., Vemula K., et al. A rationally designed peptide antagonist of the PD-1 signaling pathway as an immunomodulatory agent for cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Therapeut. 2019;18:1081–1091. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu S., Yang J., Xu B., Magiera-Mularz K., Skalniak L., Musielak B., et al. Design, synthesis, evaluation, and structural studies of C2-symmetric small molecule inhibitors of programmed cell death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 protein–protein interaction. J Med Chem. 2019;62:7250–7263. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chupak L.S., Ding M., Martin S.W., Zheng X., Hewawasam P., Connolly T.P., et al. inventors; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, assignee . 2015 Oct 22. Compounds useful as immunomodulators. USA patent WO2015160641A2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chupak L.S., Zheng X., inventors; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, assignee . 2015 Mar 12. Compounds useful as immunomodulators. USA patent WO2015034820A1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zak K.M., Kitel R., Przetocka S., Golik P., Guzik K., Musielak B., et al. Structure of the complex of human programmed death 1, PD-1, and its ligand PD-L1. Structure. 2015;23:2341–2348. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zak K.M., Grudnik P., Guzik K., Zieba B.J., Musielak B., Domling A., et al. Structural basis for small molecule targeting of the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) Oncotarget. 2016;7:30323–30335. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo J., Luo L., Wang Z., Hu N., Wang W., Xie F., et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of linear aliphatic amine-linked triaryl derivatives as potent small-molecule inhibitors of the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 interaction with promising antitumor effects in vivo. J Med Chem. 2020;63:13825–13850. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y., Xu Z., Wu T., He M., Zhang N., inventors; Guangzhou Maxinovel Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., assignee . 2018 Jan 11. Aromatic acetylene or aromatic ethylene compound, intermediate, preparation method, pharmaceutical composition and use thereof. China patent WO2018006795A1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y., Zhang N., Wu T., He M., inventors; Guangzhou Maxinovel Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., assignee . 2019 Jul 4. Aromatic vinyl or aromatic ethyl derivative, preparation method therefor, intermediate, pharmaceutical composition, and application. China patent WO2019128918A1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin M., Cao Q., Zheng S., Tian Y., Zhang H., Xie J., et al. Discovery of [1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyridines as potent inhibitors targeting the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 interaction. J Med Chem. 2019;62:4703–4715. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park J.J., Thi E.P., Carpio V.H., Bi Y., Cole A.G., Dorsey B.D., et al. Checkpoint inhibition through small molecule-induced internalization of programmed death-ligand 1. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1222. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng B., Ren Y., Niu X., Wang W., Wang S., Tu Y., et al. Discovery of novel resorcinol dibenzyl ethers targeting the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 interaction as potential anticancer agents. J Med Chem. 2020;63:8338–8358. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng B., Wang W., Niu X., Ren Y., Liu T., Cao H., et al. Discovery of novel and highly potent resorcinol dibenzyl ether-based PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with improved drug-like and pharmacokinetic properties for cancer treatment. J Med Chem. 2020;63:15946–15959. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guzik K., Zak K.M., Grudnik P., Magiera K., Musielak B., Torner R., et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of the programmed cell death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) interaction via transiently induced protein states and dimerization of PD-L1. J Med Chem. 2017;60:5857–5867. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konieczny M., Musielak B., Kocik J., Skalniak L., Sala D., Czub M., et al. Di-bromo-based small-molecule inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint. J Med Chem. 2020;63:11271–11285. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L., Yao Z., Wang S., Xie T., Wu G., Zhang H., et al. Syntheses, biological evaluations, and mechanistic studies of benzo[c][1,2,5]oxadiazole derivatives as potent PD-L1 inhibitors with in vivo antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 2021;64:8391–8409. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ribas A., Wolchok J.D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X., Yin M., Dong J., Mao G., Min W., Kuang Z., et al. Tubeimoside-1 induces TFEB-dependent lysosomal degradation of PD-L1 and promotes antitumor immunity by targeting mTOR. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:3134–3149. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y., Liu X., Zhang N., Yin M., Dong J., Zeng Q., et al. Berberine diminishes cancer cell PD-L1 expression and facilitates antitumor immunity via inhibiting the deubiquitination activity of CSN5. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:2299–2312. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang N., Dou Y., Liu L., Zhang X., Liu X., Zeng Q., et al. SA-49, a novel aloperine derivative, induces MITF-dependent lysosomal degradation of PD-L1. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magiera-Mularz K., Skalniak L., Zak K.M., Musielak B., Rudzinska-Szostak E., Berlicki Ł., et al. Bioactive macrocyclic inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:13732–13735. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCoy A.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D., Winn M.D., Storoni L.C., Read R.J. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W.G., Cowtan K. Features and development of coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murshudov G.N., Skubák P., Lebedev A.A., Pannu N.S., Steiner R.A., Nicholls R.A., et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.