Abstract

Immunotherapy has led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of cancer. Current cancer immunotherapies are mostly antibody-based, thus possessing advantages in regard to pharmacodynamics (e.g., specificity and efficacy). However, they have limitations in terms of pharmacokinetics including long half-lives, poor tissue/tumor penetration, and little/no oral bioavailability. In addition, therapeutic antibodies are immunogenic, thus may cause unwanted adverse effects. Therefore, researchers have shifted their efforts towards the development of small molecule-based cancer immunotherapy, as small molecules may overcome the above disadvantages associated with antibodies. Further, small molecule-based immunomodulators and therapeutic antibodies are complementary modalities for cancer treatment, and may be combined to elicit synergistic effects. Recent years have witnessed the rapid development of small molecule-based cancer immunotherapy. In this review, we describe the current progress in small molecule-based immunomodulators (inhibitors/agonists/degraders) for cancer therapy, including those targeting PD-1/PD-L1, chemokine receptors, stimulator of interferon genes (STING), Toll-like receptor (TLR), etc. The tumorigenesis mechanism of various targets and their respective modulators that have entered clinical trials are also summarized.

Key words: Cancer immunotherapy, Small molecules, Immunomodulators, Inhibitors, Agonists

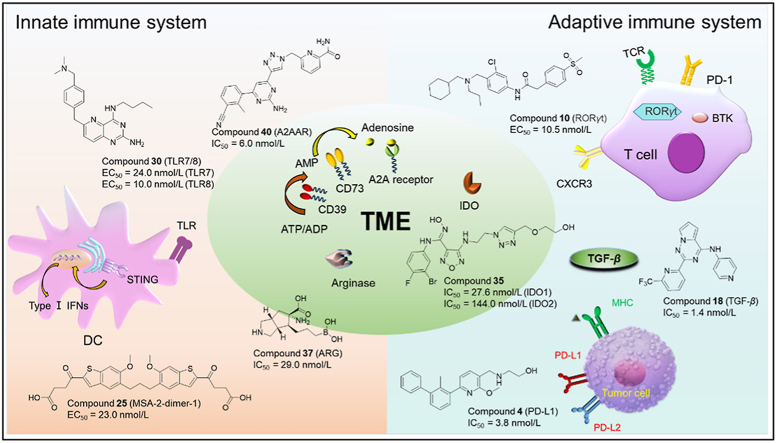

Graphical abstract

Recent advances and future directions in small molecule-based immunomodulators (inhibitors/agonists/degraders) for cancer therapy, including those targeting innate immune system, adaptive immune system, and tumor microenvironment (TME).

1. Introduction

Immunotherapy has led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of cancer1,2. Current onco-immunotherapies are based mostly on therapeutic antibodies targeting a wide range of proteins/receptors, such as PD-1/PD-L13, stimulator of interferon genes (STING)4, Toll-like receptor (TLR)5, chemokine receptors6. Fig. 1 is located in the innate/adaptive immune system or the tumor microenvironment (TME). Onco-immunotherapies, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody and chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy7 have demonstrated superior efficacy in cancer treatment8,9. For example, PD-1/PD-L1-targeting antibodies atezolizumab10 and pembrolizumab11 have been approved for treating various cancers (lung cancer and melanoma). Since the first approval of CAR-T cell-based therapy for hematological malignancies, great progresses have been made in utilizing CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors12.

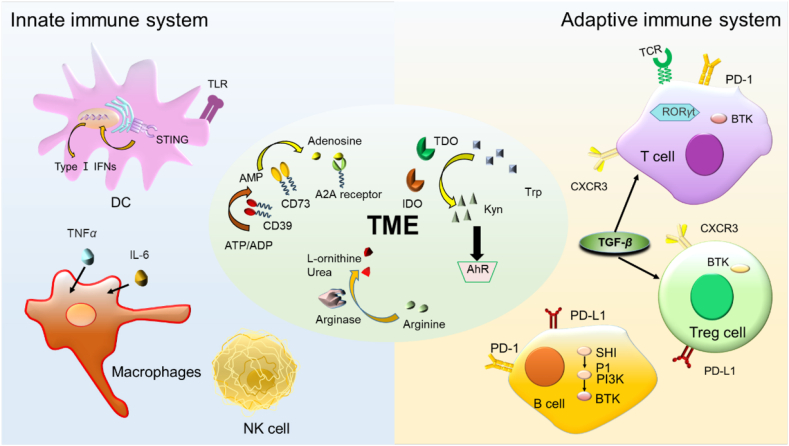

Figure 1.

Overview of immune targets related to innate immune system, adaptive immune system, and tumor microenvironment (TME).

Although numerous monoclonal antibodies (mAb) targeting immune checkpoints have been used clinically for cancer therapy as mentioned above, these therapeutic antibodies face challenges in the pharmacokinetics (i.e., long half-lives, poor tissue/tumor penetration, and little/no oral bioavailability) and pharmacodynamics (e.g., immunogenicity)13. In addition, there are also several other drawbacks for antibody-based immunotherapy including low response rate and inability to recognize intracellular targets14,15.

In contrast to therapeutic antibodies, small molecule based immunomodulators have advantages in their pharmacokinetic properties including reasonable oral availability, greater tumor/tissue penetration, acceptable half-life, and the ability to cross cell membranes to reach intracellular targets16. In addition, the cost for producing small molecules is lower in general17,18. Further, small molecule-based immunomodulators are complementary treatment modalities to therapeutic antibodies for cancer therapy, and may be combined with antibodies to elicit synergistic anticancer effects. Hence, small molecule-based cancer immunotherapies have received widespread attention in the last decade with a large number of new molecular entities discovered, as reviewed in the following section.

2. Innate and adaptive immune systems

The immune system is composed of two parts: the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system19 (Fig. 1), which protect us from many diseases including cancer20, inflammation21,22, atherosclerosis23, etc. The innate immune system is the first line of defense that can quickly generate non-specific immune response (innate immunity) against pathogens such as tumor antigens24. Antigen presenting cells (APCs) such as DC (dendritic cells) and macrophages play a key role in the maintenance of innate immunity (Fig. 1). In contrast, the adaptive immune system (e.g., T cells and B cells) produces specific and time-dependent responses (adaptive immunity) when exposing to non-self matters/antigens. Adaptive immunity enables the production of antibodies by B cells, and the antigens presented to helper T cells in turn generates cytokines to facilitate immune reactions25.

With the rapid development in molecular biology, immunology, and onco-immunology therapy, a large number of small molecules have been investigated as cancer immunotherapies. However, there are no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved small molecule-based immunotherapy for cancer so far26. In this review, we summarize the recent advances in small molecule immunomodulators that are being studied for cancer therapy.

3. Small molecule immunomodulators targeting the adaptive immune system

3.1. PD-1/PD-L1 immunomodulators

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), also known as CD279, is a surface protein which can regulate the immune system by inhibiting T-cell activity27. PD-1 is an important immunosuppressive molecule that plays a key role for the inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell response in diseases such as cancer28. PD-1 is constitutively expressed in various immune cells like T lymphocytes, natural killer T cells, activated monocytes, and B lymphocytes. Nevertheless, PD-1 is only expressed on the cell surface of activated T lymphocytes rather than resting T cells29. Thus, PD-1 can function as an intrinsic negative feedback loop for preventing T cell activation, thus reducing autoimmunity and promoting self-tolerance30. PD-1 can be activated by two ligands including PD-L1 and PD-L2, which are also type I transmembrane proteins belonging to the B7/CD28 family31. PD-L1 is widely expressed in lymphoids as well as tumor cells32. Unlike PD-L1, the expression of PD-L2 is more restricted and barely found in tumor tissues33. As shown in Fig. 2A, the infiltrated T cells overexpress PD-1, while tumor cells overexpress PD-L1 and PD-L2, which are induced by the tumor microenvironment (TME) in the body34. The binding between PD-1 and PD-L1 causes a down-regulation of T cell effector functions in cancer patients, thereby promoting immune escape and leading to the survival of tumor cells35. The blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interaction by inhibitors restores the activity of T cells and regains the immune function of T cells to fight against cancer36,37. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are also called ICIs (immune checkpoint inhibitors), and have demonstrated high efficacy in various types of tumors38. To date, numerous ICIs have been approved by FDA with all of them as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), such as Pembrolizumab (Merck, anti-PD-1), Avelumab (Pfizer & Merck, anti-PD-L1), Ipilimumab39 (BMS, anti-CTLA-4), Duvalumab (Astrazeneca, anti-PD-L1), Nivolumab (BMS, anti-PD-1), Atezolizumab (Roche, anti-PD-L1). Although these mAbs exhibit promising anti-tumor activities in patients with certain tumor types, the clinical applications of these antibody-based ICIs were hampered by limitations such as immune-related adverse effects, and the lack of oral bioavailability40,41. Therefore, the development of small molecule-based ICIs has been intensified as they have the potential to overcome the limitations of therapeutic antibodies as mentioned above.

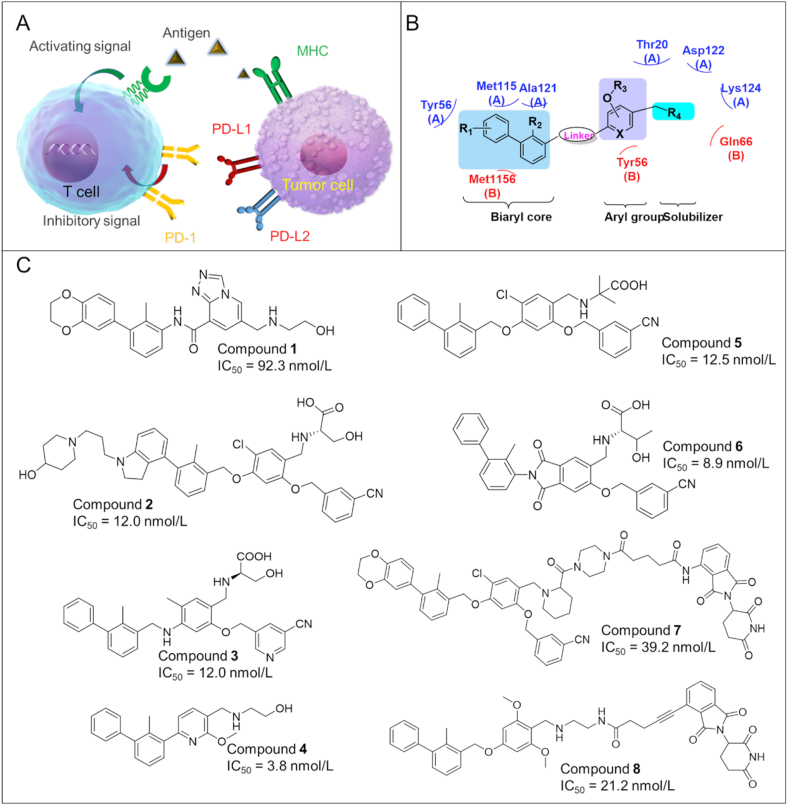

Figure 2.

(A) PD-1/PD-L1 interaction between T cell and tumor cells. (B) Pharmacophore model of PD-1/PD-L1 immunomodulators. (C) Chemical structures of representative small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 modulators.

3.1.1. Small molecule PD-L1 inhibitors

During the past 5 years, plenty of small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have been identified based on the biphenyl scaffold first disclosed by BMS company (Fig. 2B). The molecules are summarized in Fig. 2C.

Compound 1 (A22, the original compound ID/code, the same hereafter): Qin et al.42 synthesized a series of triazole-pyridine based PD-L1 inhibitors with an amide linker. Among which, compound 1 displayed the highest PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity (IC50 = 92.3 nmol/L) as assessed by a homogenous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) assay.

Compound 2 (A22): A variety of substituted 4-phenylindoline derivatives were designed and evaluated by Yang et al.43 as PD-L1 inhibitors. Compound 2 exhibited the highest PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 12.0 nmol/L (HTRF) and an EC50 of 2.9 μmol/L in a T-cell/cancer cell co-culture model.

Compound 3 (58): Guo's group44 reported the design and synthesis of a series of novel triaryl derivatives as inhibitors of PD-1/PD-L1 with a linear aliphatic amine linker. Compound 3 exhibited the most potent inhibitory activity against hPD-L1 with an IC50 value of 12.0 nmol/L and a KD of 16.2 pmol/L. Compound 3 significantly suppressed tumor growth in a humanized mouse model without obvious toxicity at a dose of 15 mg/kg.

Compound 4 (24): In 2021, a novel series of biphenyl pyridine-containing compounds without the linker was developed by Wang's team as small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors45. Among which, compound 4 strongly inhibited the interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 with an IC50 of 3.8 nmol/L 4 showed great in vivo antitumor efficacy (TGI = 66.8%) in a CT-26 mouse model. With the removal of the linker moiety, this compound is smaller than most current PD-L1 inhibitors, thus is expected to have favorable druggability.

Compound 5 (NP-19): Cheng et al.46 synthesized a series of novel small molecule compounds as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Among them, 5 exhibited high PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity with IC50 value of 12.5 nmol/L. In addition, it also demonstrated excellent in vivo antitumor efficacy (TGI = 76.5%) in a B16 melanoma tumor model. However, the oral bioavailability is relatively low (F = 5%).

Compound 6 (P39): In 2022, Sun et al.47 reported phthalimide derivatives as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. 6 not only inhibited PD-1/PD-L1 interaction (IC50 = 8.9 nmol/L), but it also exhibited a favorable safety profiles with a LD50>5000 mg/kg.

The above mentioned PD-L1 inhibitors are mostly lipophilic molecules (e.g., logP>5) with poor pharmacokinetics such as low oral bioavailability. The potency may also need to be improved when compare with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 mAbs.

3.1.2. PD-L1-targeting PROTAC degraders

PROTAC (proteolysis targeting chimera) is a protein degradation technology that has attracted significant attention from both industry and academia. PD-L1-targeting PROTACs provide an alternative approach for cancer immunotherapy. Two PROTAC degraders of PD-L1 have been reported so far as described in Fig. 2C and below.

Compound 7 (P22): In 2020, Cheng et al.48 reported the design and synthesis of a series of novel resorcinol diphenyl ether-based PROTAC degraders of PD-L1. Among them, compound 7 was able to degrade PD-L1 by 35% (at 10.0 μmol/L) via the lysosome pathway. 7 also inhibited PD-1/PD-L1 interaction with an IC50 of 39.2 nmol/L.

Compound 8 (21a): In 2021, Wang et al.49 discovered a new class of PROTAC degraders of PD-L1. Among which, compound 8 induced degradation of PD-L1 in different cancer cells through the proteasome pathway.

There are two problems with the above PROTAC PD-L1 degraders: 1) only moderate degrading efficiency was observed; 2) the exact mechanism for degrading PD-L1 remain to be elucidated. PROTAC molecules are designed for the degradation of intracellular proteins. While PD-L1 is a membrane/surface protein which may be degraded by PROTACs via the proteasome pathway after ribosomal synthesis in the cells (before maturing from the cell), or via the lysosome pathway upon endocytosis of the PROTAC–PD-L1 complex.

3.2. RORγt agonists

RORγt (retinoic acid-related orphan receptor-gamma t) belongs to the nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily and functions as a key transcription factor to drive the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th17 cells50,51. As shown in Fig. 3A, RORγt agonists can strengthen the effector function of Type 17 immune cells found in the tumor microenvironment, and enhance the antitumor immunity of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells by increasing the secretion of IL-17A52. Moreover, RORγt agonists could decrease the production of Treg (regulatory T cells) and curtail the level of co-inhibitory receptors including PD-1 on tumor-reactive lymphocytes, so as to reduce immunosuppression53. Therefore, the development of RORγt agonists could provide a promising approach for cancer immunotherapy.

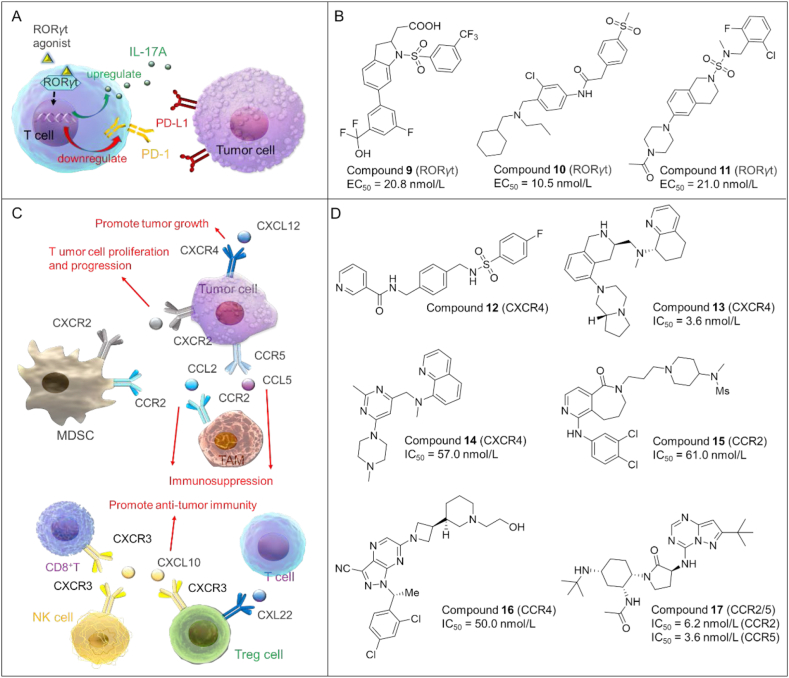

Figure 3.

(A) RORγt signaling pathways in tumor immunity. RORγt agonists act by integrating into a single treatment several antitumor mechanisms, which can disrupt the interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1, increase the production of IL-17A, and reduce Treg formation to achieve anti-tumor effects. (B) Chemical structures of representative RORγt agonists. (C) The multifaceted roles of chemokines and their receptors in tumorigenesis. Chemokines are found in tumor cells, intratumor stromal cells, while chemokine receptors are mainly expressed on the surface of tumor cells as well as immune cells including MDSC, CD8+T, NK, and Treg. Chemokine ligands can bind to their corresponding chemokine receptors, resulting in different immune responses (e.g., inducing cancer cell proliferation or promoting anti-tumor effects). MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; NK, natural killer cell; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; Treg, regulatory T cell; chemokine: CXCL1, CXCL10, CXCL12, CCL2, CCL5, CXL22; chemokine receptor: CXCR2, CXCR4, CCR2, CCR3, CXCR4, CXCR5. (D) Chemical structures of representative chemokine receptor antagonists.

Recently, small molecule RORγt agonists as potent anticancer agents have experienced a rapid development, and are summarized in Fig. 3B.

Compound 9 (14): As an orally bioavailable RORγt agonist54, compound 9 showed high potency with an EC50 of 20.8 nmol/L. In addition, it exhibited outstanding in vivo pharmacokinetics in mice with an oral bioavailability of 100%.

Compound 10 (8b): Qiu et al.55 discovered a series of tertiary-amine-based RORγt agonists. Among them, compound 10 displayed excellent RORγt agonistic activity with an EC50 of 10.5 nmol/L. Compound 10 significantly increased the production of IL-17 by ∼30% when compare to the basal levels (EC50 = 37.2 nmol/L).

Compound 11 (28): In 2021, a new set of N-sulfonamide-tetrahydroisoquinolines was synthesized as potent RORγt agonists by Ma et al.56 Among them, compound 11 activated RORγt with an EC50 of 21.0 nmol/L in a dual Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (dual-FRET) assay and maximum activation of 83.1%.

3.3. Chemokine receptor antagonists

Chemokines and chemokine receptors are important mediators of the immune system, and have multifaceted roles in tumorigenesis. For example, CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 can promote tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis57. While CXCL10 may enhance the antitumor immunity or cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells. Thus, inhibiting chemokines or their receptors (e.g., CXCL12/CXCR4) represents an attractive strategy for cancer immunotherapy58 (Fig. 3C).

3.3.1. CXCR4 antagonists

As shown in Fig. 3D, several small molecule CXCR4 antagonists have been discovered as potent anticancer agents during the past 5 years.

Compound 12 (IIIe): In 2020, Wu et al.59 discovered a new series of amide sulfamide derivatives as CXCR4 antagonists. Among which compound 12 showed a TGI of 43% in a BLAB/c mouse model of breast cancer without any bodyweight lost.

Compound 13 (25o): Compound 1360 is a highly potent, selective, and metabolically stable CXCR4 antagonist with an IC50 of 3.6 nmol/L. It also possessed excellent intestinal permeability and low risk of CYP-mediated drug–drug interactions.

Compound 14 (3): Compound 1461 is an aminoquinoline-based CXCR4 antagonist with an IC50 of 57.0 nmol/L. In addition, it also demonstrated high plasma protein binding in human (99%) but moderate binding in rats (90%) and mice (94%). However, it's rapidly metabolized in rat liver microsomes.

In spite of the potential in tumor immunotherapy, CXCR antagonists are known to cause adverse effects like cardiotoxicity62. Therefore, the development of CXCR antagonists with antitumor effectiveness and benign toxicity profiles is essential.

3.3.2. CCR2/4/5 antagonists

Over the last couple of years, tremendous efforts have been made toward the discovery of CCR antagonists as anticancer agents as detailed in Fig. 3D and below.

Compound 15 (13a): In 2018, Qin et al.63 designed and synthesized a series of 6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-pyrido[4,3-c]azepin-5-one compounds via scaffold hopping strategy. Compound 15 as a small molecule CCR2 antagonist showed potent CCR2 inhibitory activity (IC50 = 61.0 nmol/L) and 10-fold selectivity for inhibiting CCR2 over CCR5.

Compound 16 (38): In 2020, Robles et al.64 developed compound 16 as a potent small molecule antagonist of CCR4 with an IC50 of 50.0 nmol/L. Compound 16 exhibited a reasonable bioavailability (F = 29%).

Compound 17 (BMS-813160): 1765 is a promising dual antagonist of CCR2 and CCR5 with IC50 of 6.2 and 3.6 nmol/L for binding to CCR2 and CCR5, respectively. It exhibited an oral bioavailability of 100% in a mouse PK model.

3.4. Small molecule TGF-β inhibitors

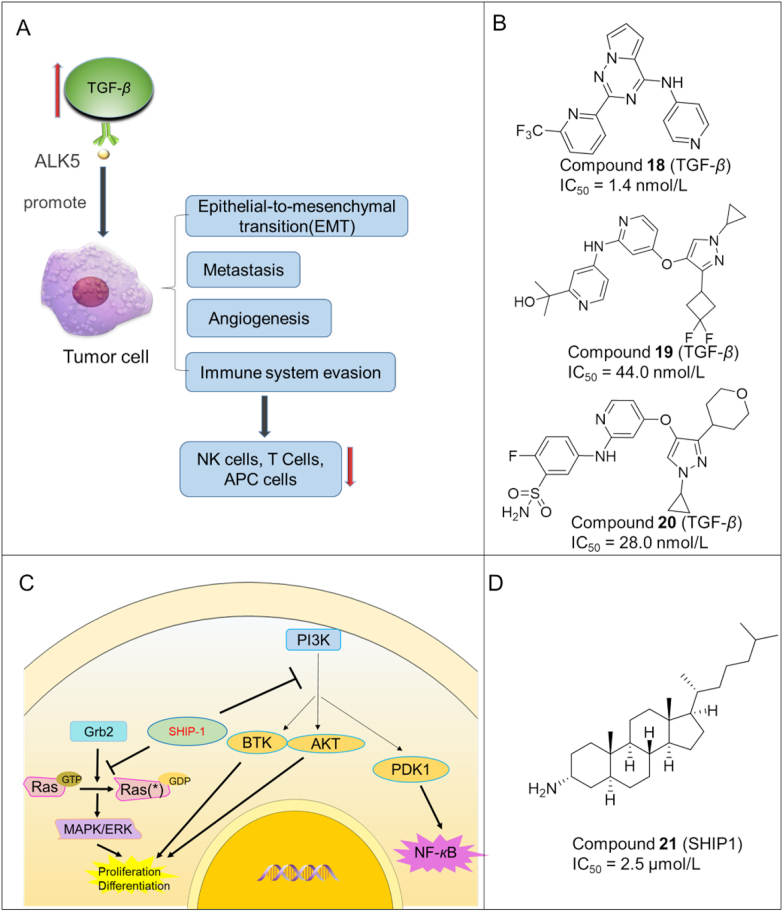

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is a pleiotropic cytokine that regulates multiple cellular processes such as cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, motility, invasion, extracellular matrix production, angiogenesis, and immune response66. TGF-β has an important role in tumorigenesis. Raised TGF-β level is associated with cancer initiation and progression as well as immune evasion (Fig. 4A). Activin receptor-like kinase 5 (ALK5), also known as TGF-β type I receptor kinase, can facilitate TGF-β signaling pathway in tumor growth. Therefore, inhibition of TGF-β/ALK5 is a new approach for cancer treatment.

Figure 4.

(A) The tumor promoting effects of TGF-β signaling. Firstly, TGF-β could enhance immune evasion by decreasing the activation of T cell, APC cells and NK cells; next, TGF-β promotes the proliferation of tumor cells through stimulation of angiogenesis as well as metastasis. Lastly, as a major EMT (epithelial mesenchymal transition) regulator, TGF-β plays a crucial role in the development of tumors. (B) Chemical structures of representative TGF-β inhibitors. (C) SHIP1 signaling in haematolymphoid cells. (D) Chemical structure of a representative SHIP1 inhibitor.

So far, several small molecule TGF-β inhibitors have been discovered, which are summarized in Fig. 4B.

Compound 18 (15): In 2018, a novel series of pyrrolotriazine derivatives were synthesized by Harikrishnan et al.67 as TGF-β inhibitors. Among them, compound 18 showed excellent binding affinity to TGF-β (IC50 = 1.4 nmol/L), long residence time (t1/2 > 120 min) and significantly improved TGF-β inhibitory potency in the PSMAD cellular assay (IC50 = 24.0 nmol/L).

Compound 19 (15r): Xu et al.68 disclosed a new set of pyrazole derivatives as ALK5 inhibitors. Compound 19 was found to be the most potent with an IC50 of 44.0 nmol/L for inhibiting ALK5. In addition, it displayed excellent bioavailability (F = 120%) and a TGI of 65.7% in a CT-26 xenograft mouse model.

Compound 20 (12r): In 2020, a series of new amino derivatives as potent ALK5 inhibitors were developed by Tan et al.69 Compound 20 exhibited strong ALK5-inhibitory activity with an IC50 of 28.0 nmol/L and a high oral bioavailability of 57.6%.

Despite the fact that TGF-β inhibitors are promising cancer immunotherapeutics, inhibiting the TGF-β pathway is associated with serious toxicities70 (e.g., valvulopathy and/or aortic pathologies), which should be closely monitored when used in tumor immunotherapy.

3.5. SH2-containing 5′-inositol phosphatase 1 (SHIP1) inhibitors

SHIP1 is a negative regulator for the activation of immune cells. It is primarily expressed in haematolymphoid cells and is the nexus of intracellular signaling pathways mediating inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects (Fig. 4C). Overactive SHIP1 could inhibit the responses and maturation of NK cells. In addition, SHIP1 can interfere with T cell receptor (TCR) signaling that can shape the development, maturation, and effector function of T lymphocytes71. Due to the important role in tumor development and immunosuppression, SHIP1 has been regarded as a promising target for small molecule inhibitors.

Compound 21 (3AC): Gumbleton et al.72 identified a steroid analog 24 as a SHIP1 inhibitor that increased the responsiveness of both T and NK cells in an intermittent and short-term treatment, resulting in significant inhibition of tumor growth (Fig. 4D).

4. Small molecule immunomodulators targeting the innate immune system

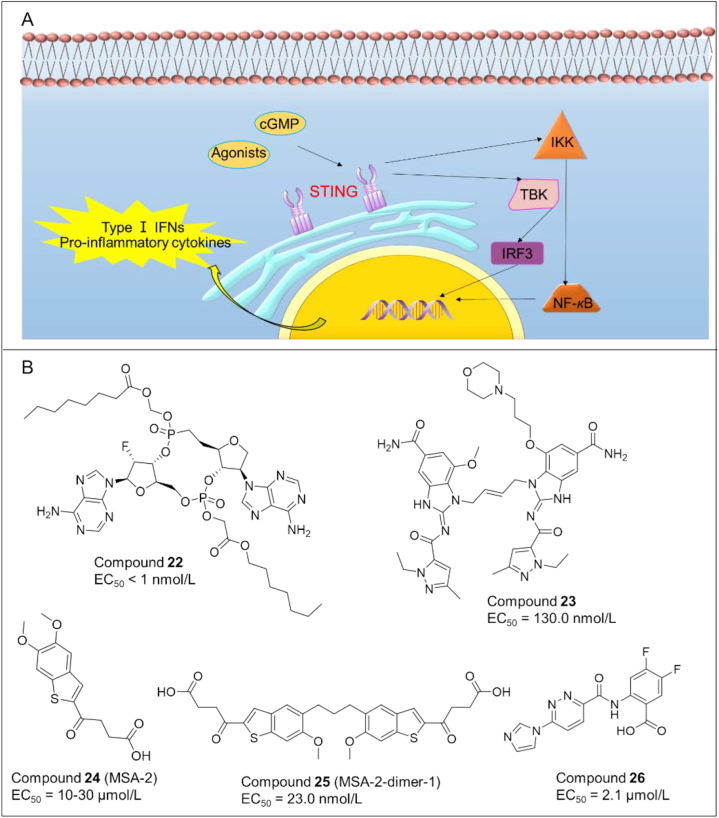

4.1. Small molecule STING agonists

Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) is a receptor protein that plays a vital role in innate immune sensing in response to cytosolic pathogen-derived and self DNA. Tumor-derived DNA induces the production of STING ligand cGAMP by cGAS and activates downstream signaling, resulting in anti-tumor immunity4,73,74 (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

(A) Overview of the Sting signaling pathway. (B) Chemical structures of representative STING agonists.

Cyclic dinucleotides (CDN) are the first generation of STING agonists, but suffer from several disadvantages such as poor cellular uptake and rapid clearance. To overcome these problems, plenty of small molecule STING agonists with novel skeletons have been identified in the past 5 years as potent anticancer agents, like isonucleotidic CDN and diABZI. The representative small molecules are as shown in Fig. 5B.

Compound 22 (31): Dejmek and co-workers75 described the discovery of a set of isonucleotidic CDN as a novel class of CDN STING agonists, of which compound 22 showed improved cellular uptake, and consequently enhanced activity up to four orders of magnitude.

Compound 23 (25): Ramanjulu et al.76 synthesized the amidobenzimidazole (ABZI) as a STING agonist that binds to the cGMP pocket of STING dimer at a ratio of 2:1. Subsequently they modified the N1-hydroxyphenethyl moiety to obtain a dimeric amidobenzimidazole ligand (diABZI) 23, which showed enhanced binding affinity to STING and could induce the secretion of IFN-β (EC50 = 130 nmol/L). In vivo, 23 exhibited satisfactory plasma concentrations and significant antitumor efficacy in a CT-26 tumor model at 1.5 mg/kg dosing intravenously.

Compound 24 (MSA-2) and compound 25 (MSA-2 dimer-1): In 2020, Pan et al.77 reported a benzothiophene derivative 24 as an orally bioavailable human STING (hSTING) agonist. 24 inhibited the binding of radiolabeled cGAMP to hSTING and induced IFN-β production in THP-1 cells. On the basis of 24, they further developed a series of covalent MSA-2 dimers, of which 25 displayed enhanced binding affinity to STING (IC50 = 23.0 nmol/L) and secretion of IFN-β (EC50 = 70.0 nmol/L).

Compound 26 (SR-717): Chin et al.78 identified another non-nucleotide STING agonist 26 (EC50 = 2.1 μmol/L) with potent antitumor activity and the ability to activate CD8+ T and DC cells in vivo. Cocrystal structure analysis demonstrated that 26 induced the same “closed” conformation of STING like cGAMP. Interestingly, 26 also increased the expression of clinically relevant targets, including PD-L1.

Compound 27 (CRD-5500): Banerjee's team79 discovered 27 (structure not available) as a direct STING agonist, causing the maturation of hDCs and release of innate and adaptive inflammatory cytokines. Pre-clinical data showed that 27 effectively reduced tumor mass via intravenous and intratumoral injections, and the anti-tumor activity can be further amplified when combined with check point inhibitor therapy.

The major barrier that hampers the clinical application of current small molecule STING agonists is immunotoxicity (e.g., unwanted inflammation) when administered systematically, as STING is ubiquitously expressed in both normal and tumor tissues. With the improved understanding of the underlying mechanisms of STING signaling defects in tumors and the assistance of targeted drug delivery, STING agonists could be developed into potential cancer immunotherapeutics.

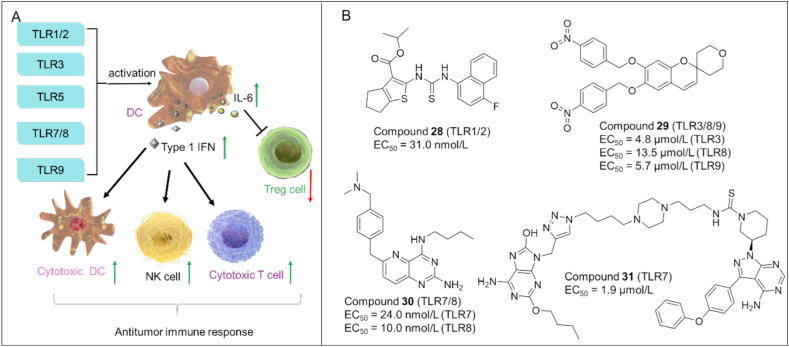

4.2. Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists

TLRs are essential membrane receptors in the innate immune system. It has been demonstrated that activation of specific TLRs such as TLR1/2, TLR3, TLR580, TLR7/8 and TLR9 can induce anti-tumor immune response through various mechanisms. As shown in Fig. 6A, activated TLRs modulate the activation of DCs, which in turn triggers the secretion of type I IFN and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in DCs. Type I IFN induces the activation of cytotoxic DC, NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), causing antitumor immunity. In addition, IL-6 secreted in DC can block the immunosuppressive function of Treg cells. Therefore, targeting TLRs with agonists have become an effective immunotherapy to treat cancer81,82.

Figure 6.

(A) The roles of TLRs in antitumor immunity. Agonizing specific TLRs (e.g., TLR3, 5, 9, and TLR7/TLR8) can trigger antitumor immunity through the activation of CTL, DC, NK and inhibition of Treg. (B) Chemical structures of representative TLR agonists.

Compound 28 (SMU-C80): By virtual screening and chemical optimization strategies, Chen et al.83 identified a highly efficient and specific human TLR1/2 agonist (28) with an EC50 of 31.0 nmol/L (Fig. 6B). 28 caused the release cytokines by recruiting MyD88 and triggering the NF-κB pathway. Moreover, 28 increased the percentage of NK-cells, B-cells, CD8+ T-cells, leading to the suppression of cancer cell growth.

Compound 29 (CUCPT17e): Zhang and co-workers84 discovered a small molecule TLR agonist (29) which was able to activate multiple TLRs including TLR 3, 8, and 9. Furthermore, 29 induced the release of various cytokines in human THP-1 cells, thus strengthening the antitumor immune response.

Compound 30 (24e): Wang et al.85 synthesized a series of pyrido[3,2-d]pyrimidine-based TLR 7/8 dual agonists. Among them, 30 exhibited potent agonistic activities toward TLR7/8 with EC50 of 24.0 and 10.0 nmol/L, respectively. In vivo study showed that 30 markedly suppressed tumor growth and led to complete tumor regression when combined with anti-PD-L1 antibody.

Compound 31 (GY161): Ren et al.86 designed a novel TLR7/BTK dual-targeting compound 31 by chemically conjugating a TLR7 agonist to ibrutinib (BTK inhibitor). In vitro, 31 activated TLR7 (EC50 = 1.86 μmol/L) and promoted the maturation of DCs. In vivo, 31 increased the number of CD8+ T cells in spleens and tumors, and suppressed tumor growth in a B16 melanoma model in mice.

Although numerous TLR agonists have shown great potential to be used as antitumor immunotherapeutic agents, the activation of TLRs can induce excessive release of pro-inflammatory factors, which may trigger autoimmune diseases or serious inflammation. Hence, it is important to carefully use TLR agonists for cancer immunotherapy to minimize immunotoxicity.

5. Small molecule immunomodulators targeting the tumor microenvironment

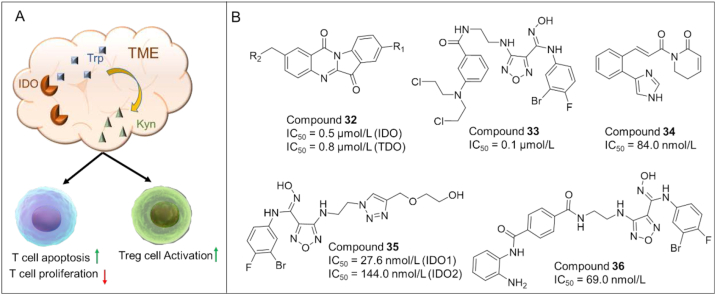

5.1. Small molecule IDO (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase) inhibitors

IDO187 is an enzyme overexpressed in tumor cells and APCs (e.g., DCs), and is activated in TME. Activated IDO1 degrades tryptophan and generates kynurenine, thus inducing T cell dysfunction (T cell anergy) and immune suppression (Fig. 7A). Thus, pharmacological inhibition of IDO1 is a compelling therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment88. Unfortunately, the recent failure of a promising IDO inhibitor (ECHO-301) in a phase III clinical trial for metastatic melanoma has dampened the enthusiasm for the development of IDO1 inhibitors. The failure is probably due to the compensation mechanism of TDO and IDO2 which also catalyze the degradation of tryptophan, in adequate drug exposure/doses, insufficient action time, and improper combination of drugs, which prompt researchers to rethink the future direction89. One of the promising strategies is to develop IDO-based dual-target inhibitors.

Figure 7.

(A) The role of IDO in T cell anergy and immune tolerance. The activation of IDO causes the degradation of tryptophan (Trp) into kynurenine (Kyn), resulting in T cell anergy via the activation of GCN2 and inhibition of mTOR, and the acceleration of Treg differentiation. (B) Chemical structures of representative IDO-based dual inhibitors.

In recent years, small molecule IDO inhibitors have gained significant attention as potential cancer immunotherapy. Although IDO inhibitors as monotherapy showed limited efficacy in cancer treatment, the development of IDO-based dual-acting agents represents a promising strategy with a number of compounds discovered as detailed in the following section and Fig. 7B.

5.1.1. IDO/TDO dual-target inhibitors

Compound 32 (RY103): In 2021, Liang et al.90 described the discovery of a dual-target inhibitor of IDO1/TDO (32) and evaluation of its preclinical efficacy for treating pancreatic cancer (PC). 32 significantly inhibited tumor growth and metastasis in KPIC orthotopic PC mice by ameliorating the immunosuppressive status.

5.1.2. IDO/DNA dual-target inhibitors

Compound 33 (4): In 2018, Fang et al.91 combined the pharmacophores of IDO1 inhibitors and chlorambucil (alkylating agents) to generate a series of dual IDO1 and DNA targeting agents. Among them, compound 33 displayed high IDO-inhibitory activity (IC50 = 130.0 nmol/L) and proper antiproliferative activity. Moreover, compound 33 exhibited decent in vivo antitumor efficacy in immunocompetent mice (CT-26 tumor growth model, TGI = 58.2%) and nude mice (TGI = 28.6%), as well as an acceptable safety profile in mice treated with a high dose of compound 33 (100 mg/kg).

5.1.3. IDO/TRXR dual-target inhibitors

Compound 34 (ZC0101): Fan et al.92 used pharmacophore fusion strategy to develop the first-generation dual inhibitors of IDO1 and TrxR (ROS modulators). Among them, compound 34 exhibited dual inhibitory activity against IDO1 (IC50 = 84.0 nmol/L) and TrxR (IC50 = 8.0 μmol/L). Compound 34 also effectively induced ROS accumulation in cancer cells and decreased plasma Kyn levels in C57BL/6 mice.

5.1.4. IDO1/IDO2 dual-target inhibitors

Compound 35 (4t): Based on the crystal structures of Epacastat in complex with IDO1/2 and molecular modeling, He et al.93 designed the first IDO1/IDO2 dual inhibitor (35) with IC50 of 28.0 nmol/L and 144.0 nmol/L for IDO1 and IDO2, respectively. Compound 35 also blocked the kynurenine pathway with IC50 of 2.2 nmol/L, and showed weak cytotoxicity.

5.1.5. IDO/HDAC dual-target inhibitors

Compound 36 (10): In 2018, Fang et al.94 developed a series of IDO/HDAC dual inhibitors by connecting the pharmacophores of Epacastat and Mocetinostat (an HDAC inhibitor) via a variety of linkers. Among them, compound 36 showed excellent inhibitory activity against IDO1 (IC50 = 69.0 nmol/L) as well as HDAC1 (IC50 = 66.5 nmol/L). Compound 36 exhibited a reasonable oral bioavailability (F = 18%), and high in vivo antitumor efficacy with a TGI of 56.0% in C57BL/6 mice bearing LLC tumors.

Although dual-target inhibitors may have advantages over single-target inhibitors with regard to their efficacy, the development of IDO-based dual acting inhibitors is still challenging, for example, the selection of a proper target that can act synergistically with IDO, and the identification of inhibitors with balanced effects against both targets95.

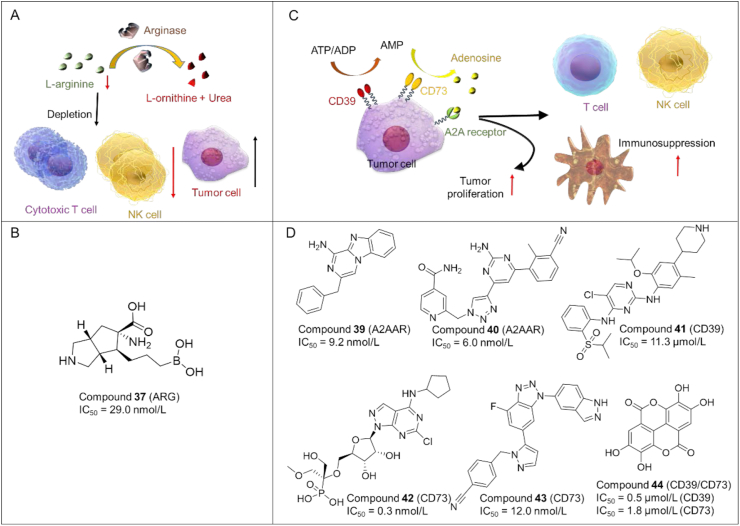

5.2. Small molecule arginase inhibitors

Arginase is a key hydrolase that converts l-arginine into l-ornithine and urea (Fig. 8A). It is important for the activation and proliferation of cytotoxic T-cells and NK-cells. Aberrant upregulation of arginase often occurs in cancer cells and immunosuppressive myeloid cells (e.g., MDSCs), which can accelerate the hydrolysis process of arginine in TME. The exhaustion of arginine results in immunosuppressive TME. Thus, inhibiting arginase is an attractive strategy for tumor immunotherapy.

Figure 8.

(A) Role of arginase in immunosuppression. Arginase is able to catalyze the conversion of l-arginine into l-ornithine and urea. Depletion of l-arginine prevents the activation of cytotoxic T cells and NK cells in tumors, thus causing immunosuppression. (B) Chemical structures of representative arginase inhibitors. (C) Mechanism of adenosine-mediated tumor survival and immunosuppression. CD39 and CD73 catabolize the production of adenosine from ATP. Adenosine can promote the proliferation of tumor cells and prevent the activation of T cells, NK cells, DC in tumors, resulting in immunosuppression. (D) Chemical structures of representative A2A adenosine receptor antagonists.

Small molecule arginase inhibitors as anticancer agents have been developed rapidly in recent years96, as shown in Fig. 8B.

Compound 37 (31a): Mitcheltree and co-workers97 developed a series of ABH derivatives as ARG inhibitors. As expected, compound 37 showed potent inhibitory activity against arginase (IC50 = 29.0 nmol/L). It also exhibited favorable pharmacokinetics with reasonable oral bioavailability (7% for mice; 29% for dog; 25% for rhesus).

Compound 38 (OATD-02): Grzybowski et al.98 reported another arginase inhibitor 38 with potent inhibitory activity against ARG-1 (IC50 = 17 nmol/L) and ARG-2 (IC50 = 34 nmol/L). 38 demonstrated acceptable oral bioavailability and high antitumor efficacy in various mouse models, as well as favorable safety profiles. 38 is a promising arginase inhibitor that will enter phase I clinical trials for the treatment of cancer.

5.3. A2A adenosine receptor and CD39/CD73 antagonists

5.3.1. Small molecule antagonists of A2A adenosine receptors

It has been reported that the levels of adenosine are elevated in TME, and adenosine can cause immunosuppressive effects by binding to A2A adenosine receptors (A2AAR) in the surface of tumor cells, thus blunting immune effector cells and promoting the immune escape of tumor cells (Fig. 8C). Therefore, blocking the adenosine-A2AAR interaction and inhibiting adenosine-generating enzymes (e.g., CD39 and CD73) are two effective strategies to reverse immunosuppression99,100. However, A2A adenosine receptor antagonists showed no effect in some patients due to the unrecognition of TCR, which could be caused by the lack immune cells, or the deletion/mutation of cancer cell antigens. Thus, combining A2A adenosine receptor antagonists with CAR-T may an effective strategy for cancer therapy.

Compound 39 (27): Reddy et al.101 designed and synthesized a series of compounds as antagonists of A2A adenosine receptors. Among which compound 39 (Fig. 8D) showed higher binding affinity to A2A (IC50 = 9.2 nmol/L), high potency in cAMP (IC50 = 31.0 nmol/L) functional and IL-2 (EC50 = 164.6 nmol/L) production assays.

Compound 40 (7i): Li et al.102 discovered a series of dual A2AAR/A2BAR antagonists by introducing a methylbenzonitrile group and a pyridine ring to the triazole-pyrimidine scaffold. Among them, compound 40 showed excellent inhibitory activity against A2AAR (IC50 = 6.0 nmol/L) and A2BAR (IC50 = 14.1 nmol/L), as well as high potency in IL-2 production. In addition, 40 exhibited high liver microsomal stability and acceptable PK properties in vivo.

5.3.2. Small molecule inhibitors of CD39/CD73

A number of small molecule inhibitors of CD39/CD73 have been discovered as potent anti-tumor agents, as summarized in Fig. 8D.

Compound 41 (Ceritinib): Schakel et al.103 discovered a selective CD39 hit compound 41 (IC50 = 11.3 μmol/L), which is an approved ALK inhibitor. 41 decreased the extracellular concentrations of immunosuppressive adenosine with high metabolic stability and optimized physicochemical properties. Thus, compound 41 has the potential to be used as a dual CD39/ALK inhibitor for tumor immunotherapy.

Compound 42 (OP-5244): Du et al.104 designed a series of novel monophosphonate as small molecule CD73 inhibitors. Among them, 42 exhibited potent inhibitory activity against hCD73 (IC50 = 0.3 nmol/L) and relatively low oral bioavailability (1.8% for rat, 11.3% for dog, and 3.7% for cynomolgus monkey).

Compound 43 (73): Beside the nucleotide inhibitors, a number of non-nucleotide CD73 inhibitors were designed to improve the drug-like properties (membrane permeability). Among them, compound 43 discovered by Beatty105 showed high CD-73-inhibitory activity with IC50 of 12.0 nmol/L.

Compound 44 (Ellagic acid): Wang's team106 described the discovery of 44 as a dual CD39/CD73 inhibitor with IC50 of 0.5 and 1.8 μmol/L, respectively. 44 represents a valuable natural product-based lead compound for cancer immunotherapy.

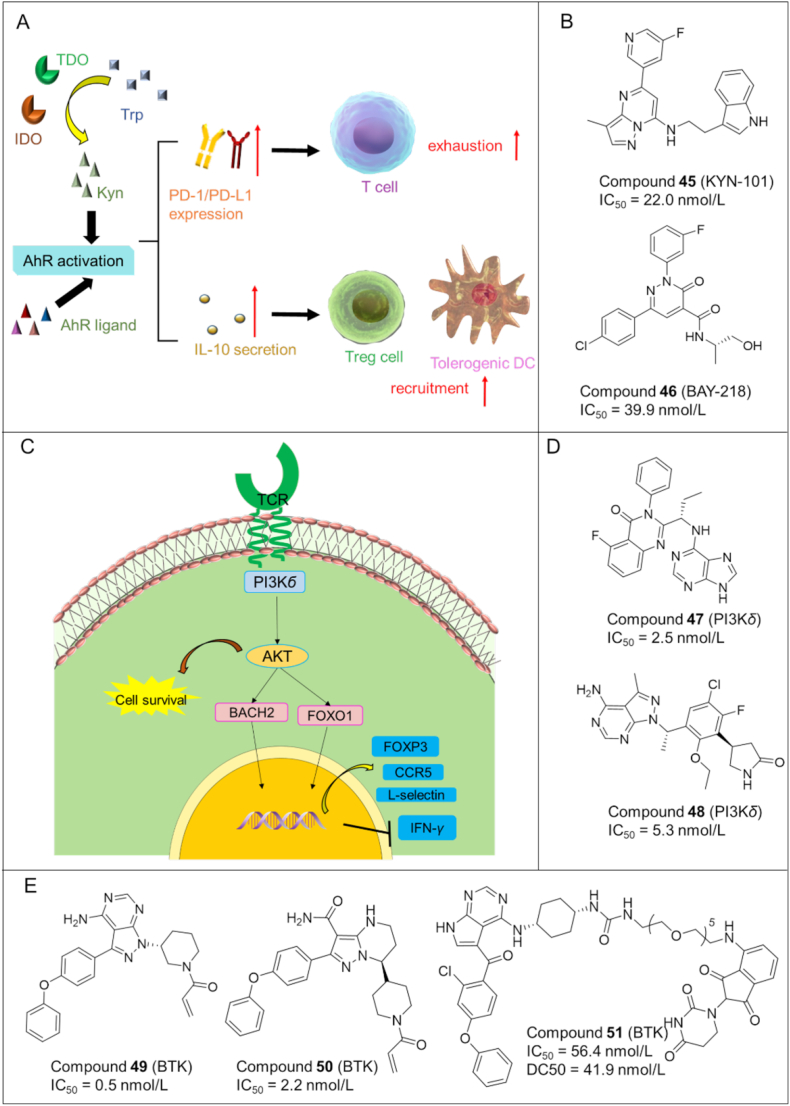

5.4. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) antagonists

AhR is a ligand activated transcription factor that controls the expression of a number of immunosuppressive signaling molecules, including the immune checkpoint proteins PD-1/PD-L1 and cytokine IL-10. AhR activation also stimulates the formation and recruitment of TolDCs (tolerogenic dendritic cells), TAMs (tumor associated macrophages), and regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment, which restrains antitumoral immune response (Fig. 9A). Overexpression of AhR has been observed in a number of different types of cancers and is suggested to contribute to immune dysfunction and cancer progression107.

Figure 9.

(A) Mechanism of AhR pathway in immunosuppression. (B) Chemical structures of representative AhR inhibitors. (C) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-δ pathway in the regulation of Tregs and anti-cancer immunity. (D) Chemical structures of representative PI3K-δ inhibitors. (E) Chemical structures of representative BTK inhibitors.

Compound 45 (KYN-101): Campesato et al.108 discovered a potent AHR antagonist of 45 with IC50 value of 22.0 nmol/L (Fig. 9B). 45 suppressed tumor growth in B16 melanoma mouse models overexpressing IDO1/TDO.

Compound 46 (BAY218): Schmees et al.109 reported another small molecule 46 with potent inhibitory activity against AhR (IC50 = 39.9 nmol/L). 46 could also enhanced the in vivo antitumor efficacy of anti-PD-L1 antibody in a CT-26 mouse model (Fig. 9B).

6. Small molecule kinase inhibitors with tumor immunomodulatory effects

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ (PI3K-δ) and Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) were firstly identified as targets of anticancer agents, but immune-related toxicity for their inhibitors have been reported in clinical applications. For example, the PI3K-δ inhibitor idelalisib was approved in 2014 for treating relapsed follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but severe adverse effects were documented due to disruption of the immune system, e.g., impairing the production of IL-6 and IL-10. This provides new targets for tumor immunotherapeutic agents and may open novel avenues in cancer immune therapy.

6.1. PI3K-δ inhibitors

PI3K-δ has diverse biological functions by generating lipid second messengers. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated the critical role of PI3K-δ in Treg differentiation and immunosuppressive function. PI3K-δ activates AKT pathway (Fig. 9C), leading to the phosphorylation of BACH2 and FOXO1 transcription factors which can regulate the production FOXP3, L-selectin, CCR7 and IFN-γ110.

Compound 47 (idelalisib): Idelalisib111 is a PI3K-δ inhibitor undergoing clinical trials for cancer treatment (Fig. 9D). Further studies showed that idelalisib reduced Tregs without affecting the CD4/CD8 ratio or the absolute number of T-cells. Therefore, compound 47 may exert anticancer effects by modulating the immune system, in addition to inhibiting PI3K-δ.

Compound 48 (parsaclisib): Parsaclisib112 is a novel PI3K-δ inhibitor being investigated in clinical trials for the treatment of B-cell malignancies (Fig. 9D). Recently it was found that parsaclisib suppressed tumor growth in the murine A20 model, and reduced Treg cells in the tumors and spleens of mice. These results were consistent with previous clinical data that combined use of parsaclisib and pembrolizumab (PD-L1 antibody) significantly reduced Treg cells in patients with solid tumors.

6.2. BTK modulators (inhibitors/degraders)

BTK belongs to the Tec family and plays a significant role in B-cell receptor (BCR) signal pathways that regulate the differentiation and proliferation of B cells. Notably, BTK has immunomodulatory effects on the cytokine/chemokine network and a variety of immune cell subsets in the adaptive immune system including CD4 and CD8 T cells, NK cells, MDSCs, and DCs. Thus, targeting BTK can be a compelling strategy for anti-tumor immunotherapy113.

6.2.1. Small molecule BTK inhibitors

BTK modulators (inhibitors/degraders) can be used as immunomodulators for the treatment of various conditions including cancer and autoimmune diseases (e.g., arthritis). Thus BTK-targeting therapeutic agents have experienced a rapid development in recent years with some of them summarized in Fig. 9E.

Compound 49 (Ibrutinib): Compound 49113, 114, 115, 116 is the first BTK inhibitor approved for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma and CLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia). Ibrutinib could decrease the effector memory T cells as well as Treg and MDSCs, while restoring the low counts of innate cell subsets (i.e., DCs) in CLL patients toward the healthy donor range, thereby rescuing both T cell and myeloid cell defects associated with CLL114, 115, 116.

Compound 50 (Zanubrutinib): Compound 50117 is a second generation BTK inhibitor with higher potency and selectivity than ibrutinib. It could downregulate PD-1 and PD-L1 levels in T cells and tumor cells, respectively. It also decreased the expression levels of CXCR5 and CD19 in B cells in nearly all patients.

6.2.2. PROTAC BTK degraders

In addition, numerous BTK-targeting PROTAC degraders (e.g., compound 51 (6e) in Fig. 9E)118 have been disclosed in recent years, providing an alternative for targeting BTK in the treatment of cancer and autoimmune diseases. These PROTAC degraders of BTK have the potential to overcome the drawbacks (e.g., drug resistance) of conventional BTK inhibitors. However, the druggability of PROTAC molecules remain to be improved.

7. Small molecule immunomodulators marketed and in clinical trials

7.1. Investigational (clinical stage) small molecule immunomodulators

During the past 5 years, many small molecule immunomodulators have been identified with some of them in clinical trials. Herein, we summarize the investigational (clinical stage) small molecule immunomodulators based on their molecular targets.

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors: As shown in Table 1, a number of small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have entered clinical trials. For example, CA-170 (NCT02812875) is a rationally designed and orally available PD-L1 inhibitor which also acts as a V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA). In the completed phase 1 trial (NCT02812875), CA-170 demonstrated favorable pharmacokinetics and acceptable safety profiles. In phase II clinical trials, CA-170 exhibited encouraging clinical effects119. INCB086550120, an orally bioavailable PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor with nanomolar affinity, is currently being investigated in patients with advanced solid tumors (phase II, NCT04629339). IMMH-010121 is a brain permeable PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor undergoing a phase I clinical trial for advanced solid tumors (NCT04343859). Other small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors currently in phase clinical trials include MAX-10181121 (NCT05196360), GS-4224 (NCT04049617), ASC61 (NCT05287399), BPI-371153 (NCT05341557).

Table 1.

Small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical trials.

| ID | Structure | Indication (clinical status) |

|---|---|---|

| CA-170 |  |

Advanced tumors and lymphomas (Phase I) |

| INCB086550 |  |

Advanced solid tumors (Phase II) |

| IMMH-010 |  |

Advanced solid tumors (Phase I) |

| MAX-10181 |  |

Advanced solid tumors (Phase I) |

| GS-4224 |  |

Advanced solid tumors (Phase IB/2) |

| ASC61 | Unknown | Advanced solid tumors (Phase I) |

| BPI-371153 | Unknown | Advanced solid tumors (Phase I) |

RORγt agonists: LYC-55716 is a potent and orally bioactive RORγt agonist that can improve the function of immune cells and decrease immune suppression. The phase 1/2a clinical trials in adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic cancer have been completed for LYC-55716 (Table 2)122. The clinical studies indicated that LYC-55716 has therapeutic effects on locally advanced or metastatic cancer with favorable safety profiles.

Table 2.

Small molecule RORγt agonists and chemokine receptor antagonists in clinical trials.

| Target | ID | Structure | Indication (clinical status) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RORγt | LYC-55716 |  |

Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors (Phase I/IIA) |

| Chemokine receptor | AZD5069 |  |

Advanced solid tumors and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (Phase IB/2) |

| X4P-001 |  |

Metastatic colorectal cancer (Phase I) | |

| Vicriviroc |  |

Advanced/metastatic microsatellite stable (MSS) colorectal cancer (Phase II) | |

| Maraviroc |  |

Metastatic colorectal cancer (Phase I) | |

| SX-682 |  |

Metastatic melanoma (Phase I) |

Chemokine receptor antagonists: AZD-5069 is a CXCR2 antagonist being studied in phase Ib/II clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumors (NCT02499328) (Table 2)123. X4P-001124 is an orally bioavailable CXCR4 inhibitor which has been evaluated in phase I/II studies in combination with pembrolizumab and/or maraviroc for mCRC (metastatic colorectal cancer) (NCT03274804). Vicriviroc125 (MK-7690) as a CCR5 antagonist is undergoing a phase II trial in combination with Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in participants with advanced/metastatic microsatellite stable (MSS) colorectal cancer (CRC) (NCT03631407). The combination of maraviroc and pembrolizumab126 is being evaluated in a phase I study (NCT03274804) for mCRC (metastatic colorectal cancer). SX-682127 (combined with pembrolizumab) is currently in a phase I clinical trial for treating metastatic melanoma (NCT03161431).

TGF-β inhibitors: Galunisertib128 (also known as LY-2157299, Table 3) as a small molecule TGF-β receptor I kinase inhibitor is undergoing several clinical trials for rectal adenocarcinoma and prostate cancer. Another TGF-β inhibitor, LY-3200883, is being evaluated in clinical trials for patients with solid tumors (NCT02937272). Vactosertib (EW-7197)129 is an ALK5 inhibitor which also blocks TGF-β-mediated immune suppression. Vactosertib is being investigated in a phase I clinical study for advanced solid tumors (NCT03143985; NCT02160106).

Table 3.

Small molecule TGF-β inhibitors and PI3K-δ inhibitors in clinical trials.

| Target | ID | Structure | Indication (clinical status) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β | LY-2157299 |  |

Rectal adenocarcinoma (Phase II) prostate cancer (Phase II) |

| LY-3200883 |  |

Solid tumors (Phase I) | |

| EW-7197 |  |

Advanced stage solid tumor (Phase I) | |

| PI3K-δ | Parsaclisib |  |

Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Phase II) |

| Acalisib |  |

Lymphoid malignancies (Phase IB) | |

| Linperlisib |  |

Lymphoma (Phase II) | |

| Umbralisib |  |

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (Phase II) | |

| SHC014748M |  |

Lymphoma (Phase II) |

PI3K-δ inhibitors: Parsaclisib130 is a potent PI3K-δ inhibitor (Table 3) being investigated in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (NCT02998476). Acalisib131 (GS-9820) has been studied in a phase 1b clinical trial for lymphoid malignancies (NCT01705847). Linperlisib132 (YY-20394) is being assessed in a phase II clinical trial for adult patients with R/R Peripheral T/NK Cell Lymphoma (NCT05274997). Other PI3K-δ inhibitors such as Umbralisib133 (TGR-1202) (NCT03364231), SHC014748M134 (NCT04431089), and HMPL-689135 (NCT04849351) have entered clinical trials for the treatment of various cancers.

STING agonists: In recent years, numerous STING agonists have entered clinical trials as illustrated in Table 4. ADU-S100136 was in a phase I clinical trial to treat advanced solid tumors (NCT02675439) but failed to show efficacy. E7766137 is a macrocycle-bridged STING agonist undergoing phase 1 clinical trials for lymphoma and advanced solid tumors (NCT04144140). TAK-676138 is now being evaluated in phase 1 trial for solid tumors (NCT04420884). MK-1454139 is a STING agonist undergoing a phase I study to treat solid tumors (NCT04420884). Other STING agonist that are in clinical trials with different solid tumors include BMS-986301140 (NCT03956680), SB-11285141 (NCT04096638), MK-2118 (NCT03249792), HG-381 (NCT04998422), GSK-3745417 (NCT05424380), SNX281 (NCT04609579)142.

Table 4.

Small molecule STING agonists in clinical trials.

| ID | Structure | Indication (clinical status) |

|---|---|---|

| ADU-S100 |  |

Advanced/metastatic solid tumors or lymphomas (Phase I) |

| E7766 |  |

Lymphoma and advanced solid tumors (Phase IB) |

| TAK-676 |  |

Solid tumors (Phase I) |

| BMS-986301 | Unknown | Advanced solid cancers (Phase I) |

| SB-11285 | Unknown | Melanoma/head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (Phase IA/IB) |

| MK-2118 | Unknown | Solid tumor lymphoma (Phase I) |

| HG-381 | Unknown | Advanced solid tumor (Phase I) |

| GSK-3745417 | Unknown | Neoplasms (Phase I) |

| SNX281 | Unknown | Advanced solid tumor (Phase I) |

TLR agonists: The clinical stage TLR agonists are summarized in Table 5. GSK1795091143 is TLR4 agonist which has been evaluated in phase I study for treating patients with neoplasms (NCT02798978). Imiquimod144 is a TLR7 agonist being studied in clinical trials for different tumors such as basal cell carcinoma (NCT00314756) and melanoma (NCT01720407). Other TLR7 agonists undergoing clinical trials include LHC165145 (NCT03301896), DSP-0509146 (NCT03416335), JNJ-64794964147 (NCT04273815). MEDI-9197148 as a TLR7/8 agonist was studied in a phase I trial for solid tumors (NCT02556463) but failed. Motolimod149 is a potent TLR8 agonist currently being investigated for ovarian cancer in combination with Durvalumab and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (NCT02431559).

Table 5.

Small molecule TLR agonists in clinical trials.

| ID | Structure | Indication (clinical status) |

|---|---|---|

| GSK1795091 |  |

Neoplasms (Phase I) |

| Imiquimod |  |

Basal cell carcinoma (Phase IV) Melanoma (Phase III) |

| LHC165 |  |

Solid tumors (Phase I) |

| Guretolimod (DSP-0509) |  |

Solid tumors (Phase I/II) |

| JNJ-64794964 | Unknown | NSCLC (Phase IB) |

| MEDI-9197 |  |

Solid tumors (Phase I) |

| Motolimod |  |

Ovarian cancer (Phase I/II) |

IDO1 inhibitors: As shown in Table 6, indoximod150 (NCT03301636), Epacadostat151 (NCT03361865), Navoximod (GDC-0919)152 (NCT02048709) and NLG802153 (NCT03164603) have been studied in various stages of clinical trials. However, Epacadostat failed to show efficacy in the phase III clinical trial for metastatic melanoma. Thus, researchers have turned their attention to IDO-based dual inhibitors with many of them advanced to clinical trials. For example, two IDO/TDO dual inhibitors [BMS-986205154 (NCT03792750) and SHR9146155 (HTI-1090) (NCT03208959)] are being studied in clinical trials for advanced solid tumors.

Table 6.

Small molecule IDO1 inhibitors in clinical trials.

| Target | ID | Structure | Indication (clinical status) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDO | Indoximod |  |

Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (Phase II) |

| Epacadostat |  |

Urothelial cancer (Phase III) | |

| Navoximod |  |

Solid tumors (Phase I) | |

| NLG802 |  |

Solid tumors (Phase I) | |

| IDO/TDO | BMS-986205 |  |

Advanced cancer (Phase I/2) |

| SHR9146 | Unknown | Advanced solid tumors (Phase I) |

A2A adenosine receptor antagonists: Ciforadenant156 (CPI-444) is an A2A adenosine receptor antagonist which has been studied in a phase I trial for solid tumors (NCT02655822) (Table 7). Imaradenant (AZD4635)157 is another A2A adenosine receptor antagonist being investigated in a phase I clinical trial for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) (NCT03192943). Other A2A adenosine receptor antagonists such as Etrumadenant (AB928)158 (NCT05277012), Inupadenant159 (NCT04233060), M1069160 (NCT05198349) and PBF-509/NIR178161 (NCT02403193) have entered clinical trials. CD73, a 5′ nucleotidase in the cell surface, can produce adenosine from AMP. CD73 represents an attractive target for tumor immunotherapy. As for CD73 inhibitors, AB680162 is currently in Phase I stage for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Other CD73 inhibitors being evaluated in clinical trials include LY3475070163 (NCT04148937) and ORIC-533164 (NCT05227144).

Table 7.

Small molecule A2A adenosine receptor antagonists and CD73 inhibitors in clinical trials.

| Target | ID | Structure | Indication (clinical status) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenosine receptor | CPI-444 |  |

Solid tumors (Phase I) |

| AZD4635 |  |

Prostate cancer (Phase II) | |

| Etrumadenant (AB928) |  |

Healthy volunteers (Phase I) | |

| Inupadenant |  |

Advanced solid tumors (Phase I) | |

| M1069 | Unknown | Metastatic solid tumors (Phase I) | |

| PBF-509/NIR178 |  |

NSCLC (Phase I/IB) | |

| CD73 | AB680 |  |

Advanced pancreatic cancer (Phase I) |

| LY3475070 |  |

Advanced cancer (Phase I) | |

| ORIC-533 | Unknown | Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (Phase IB) |

Arginase inhibitors: CB-1158165 (INCB001158) is a promising arginase inhibitor being studied in a phase I clinical trial for patients with advanced/metastatic solid tumors (NCT02903914, Table 8).

Table 8.

Small molecule arginase inhibitors and AhR antagonists in clinical trials.

| Target | ID | Structure | Indication (clinical status) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arginase | CB-1158 |  |

Advanced/metastatic solid tumors (Phase I/II) |

| AhR | IK175 |  |

Solid tumors (Phase IA/B) |

| BAY2416964 |  |

Advanced solid tumors (Phase I) |

Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) antagonists: IK175166 is an orally bioavailable AhR inhibitor being assessed in a phase 1a/b study as a single agent and/or in combination with Nivolumab in patients with metastatic solid tumors and urothelial carcinoma (NCT04200963, Table 8). Another AhR antagonist, BAY2416964167, is currently being investigated in a clinical trial for treating advanced solid tumors.

7.2. Approved (marketed) small molecule immunomodulators

Although numerous small molecule immunomodulators have been identified with some of them in clinical trials as summarized above, only two immunomodulators (TLR agonists) have been approved by FDA (Table 9) for use as cancer vaccine adjuvants or anticancer drugs. The first one is monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA), which is a TLR4 agonist developed and marketed by GSK company as an adjuvant of cervical cancer vaccine. MPLA is lipid A derivative isolated from Salmonella minnesota R595 lipopolysaccharide (LPS), but is significantly less toxic than LPS while maintaining immunostimulatory effects. As a vaccine adjuvant, MPLA could induce a strong Th1 response when tested in animal models168. The second one is Imiquimod (R-837; TMX-101; S-26308; trade names: Aldara; Zyclara among others), which is a TLR7 agonist and the first small-molecule immuno-oncology drug approved by the FDA for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Imiquimod was developed by 3M's pharmaceuticals division and gained the first FDA approval in 1997 under the brand name of Aldara.

Table 9.

Approved (marketed) small molecule immunomodulators.

| Target | ID | Structure | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4 | MPLA |  |

Cervical cancer vaccine |

| TLR7 | Imiquimod |  |

Basal cell carcinoma |

8. Discussion and conclusions

Immunotherapy has become one of the three pillars of cancer therapeutics (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy). In particular, antibody-based immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer treatment with high specificity and efficacy. However, antibody-based immunotherapy has several drawbacks including unfavorable pharmacokinetics (e.g., poor tissue/tumor penetration, little/no oral bioavailability and long half-lives) and pharmacodynamics (e.g., immunogenicity). In contrast to therapeutic antibodies, small molecule immuno-oncology agents have the potential to obviate the above disadvantages of antibodies. For example, antibodies are unable to penetrate cell membranes to exert their effects on intracellular targets such as STING and IDO1, while small molecules can act on intracellular targets. In addition, small molecules are more amenable than antibodies to structural modifications for achieving better pharmacokinetics such as high oral bioavailability. Further, small molecule-based immunomodulators and therapeutic antibodies are complementary modalities for cancer treatment, and may be combined to elicit synergistic effects.

Despite recent progress made in small molecule-based immunomodulators for cancer therapy, numerous obstacles remain to unlocking the full potential of immunotherapy. One of the challenges is to design compounds with high affinity to those targets without a stable or pocket-like active site. PD-L1 interacts with PD-1 through a hydrophobic, flat and extended (∼1.700 Å) interface, meaning that each of them does not have a deep binding pocket. One of the effective strategies to solve this problem is to design allosteric modulators. In addition, small molecule immunomodulators may exhibit less specificity than therapeutic antibodies, thus causing undesired adverse effects (e.g., ibrutinib and idelalisib). Nonetheless, a number of potent small molecule immunomodulators have been advanced to clinical stages, providing confidence to this field. Moreover, with the availability of crystal structures for many target proteins and the assistance of computer aided drug design technology, the prospects for discovering potent small molecule immunomodulators for cancer therapy seem to be more promising, e.g., compounds with improved specificity, and pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic/toxicological profiles.

Another challenge for small molecule immuno-oncology agents is that many immunotherapeutic targets and pathways are interlinked, which means that modulating one target may affect additional immune signaling pathways. Taking IDO1 as an example, inhibition of IDO1 can affect Trp metabolism in the tumor microenvironment to enhance anti-tumor immunity. However, Trp may be compensated by other enzymes such as IDO2, TDO, which is one of the reasons for the poor efficacy of ECHO-301 (IDO1 inhibitor) in phase III clinical trials. One of the future directions for the development of IDO inhibitors is to design dual-target or multi-target inhibitors for Trp metabolism, such as IDO1/IDO2 dual-target inhibitors or IDO1/TDO dual-acting inhibitors. There are already clinical or preclinical studies for multi-target inhibitors showing advantages over IDO1 single-target inhibitors. In terms of chemokine receptors, a large number of chemokine receptors and ligands have been identified and play multifaceted roles in tumor development and immunosuppression. Further study is needed to investigate the connection among different chemokine receptors/ligands to design potent chemokine receptor antagonists.

A large number of studies have shown that some chemotherapeutic drugs display anti-tumor effects through immune-related pathways in addition to inhibiting the necessary targets for tumorigenesis. One of the future directions in this field is to develop bifunctional or multi-functional molecules with anti-tumor and indirect immunomodulatory activity, which may open a new avenue for small molecule immunomodulators. In fact, Schakel et al.103 have developed dual CD39/ALK inhibitors, and Ren et al.86 designed dual-acting TLR7/BTK modulators by chemically conjugating a TLR7 agonist to ibrutinib.

Nonetheless, tremendous efforts have been made and are still ongoing towards the discovery of small molecule-based immunotherapy, which may lead to a new paradigm for the treatment of cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82173668), Scientific Research Project of High-Level Talents (No. C1034335, China) in Southern Medical University of China, and Thousand Youth Talents Program (No. C1080094, China) from the Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee, China.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Kui Cheng, Email: chengk@smu.edu.cn.

Huichang Bi, Email: bihchang@smu.edu.cn.

Jianjun Chen, Email: jchen21@smu.edu.cn.

Author contributions

Yinrong Wu and Zichao Yang searched the literatures and wrote the manuscript. Kui Cheng and Huichang Bi provided the new idea. Jianjun Chen edited the language, conceived the study and provided the guidance of the whole study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Osipov A., Saung M.T., Zheng L., Murphy A.G. Small molecule immunomodulation: the tumor microenvironment and overcoming immune escape. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:224. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0667-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S., Song Z., Zhang A. Small-molecule immuno-oncology therapy: advances, challenges and new directions. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019;19:180–185. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190308131805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin X., Lu X., Luo G., Xiang H. Progress in PD-1/PD-l1 pathway inhibitors: from biomacromolecules to small molecules. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding C., Song Z., Shen A., Chen T., Zhang A. Small molecules targeting the innate immune cGAS‒STING‒TBK1 signaling pathway. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:2272–2298. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rostamizadeh L., Molavi O., Rashid M., Ramazani F., Baradaran B., Lavasanaifar A., et al. Recent advances in cancer immunotherapy: modulation of tumor microenvironment by Toll-like receptor ligands. Bioimpacts. 2022;12:261–290. doi: 10.34172/bi.2022.23896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miao M., De Clercq E., Li G. Clinical significance of chemokine receptor antagonists. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2020;16:11–30. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2020.1711884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masoumi J., Jafarzadeh A., Abdolalizadeh J., Khan H., Philippe J., Mirzaei H., et al. Cancer stem cell-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAT)-T cell therapy: challenges and prospects. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:1721–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chacon A.C., Melucci A.D., Qin S.S., Prieto P.A. Thinking small: small molecules as potential synergistic adjuncts to checkpoint inhibition in melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:3228. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y., Zhang X., Wang Y., Zhao W., Li H., Zhang L., et al. Application of immune checkpoint targets in the anti-tumor novel drugs and traditional Chinese medicine development. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:2957–2972. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sangro B., Sarobe P., Hervas-Stubbs S., Melero I. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:525–543. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00438-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spisarova M., Melichar B., Vitaskova D., Studentova H. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2021;21:693–703. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2021.1903321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma S., Li X., Wang X., Cheng L., Li Z., Zhang C., et al. Current progress in CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2548–2560. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.34213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb E.S., Liu P., Baleeiro R., Lemoine N.R., Yuan M., Wang Y.H. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Biomed Res. 2018;32:317–326. doi: 10.7555/JBR.31.20160168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topalian S.L., Taube J.M., Anders R.A., Pardoll D.M. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:275–287. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Offringa R., Kotzner L., Huck B., Urbahns K. The expanding role for small molecules in immuno-oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21:821–840. doi: 10.1038/s41573-022-00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van der Zanden S.Y., Luimstra J.J., Neefjes J., Borst J., Ovaa H. Opportunities for small molecules in cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:493–511. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams J.L., Smothers J., Srinivasan R., Hoos A. Big opportunities for small molecules in immuno-oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:603–622. doi: 10.1038/nrd4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van den Bulk J., Verdegaal E.M., de Miranda N.F. Cancer immunotherapy: broadening the scope of targetable tumours. Open Biol. 2018;8 doi: 10.1098/rsob.180037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viana I.M.O., Roussel S., Defrene J., Lima E.M., Barabe F., Bertrand N. Innate and adaptive immune responses toward nanomedicines. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:852–870. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell D., Chintala S., Dey M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell in immunity and cancer. J Neuroimmunol. 2018;322:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castanheira F.V.S., Kubes P. Neutrophils and nets in modulating acute and chronic inflammation. Blood. 2019;133:2178–2185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-844530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H., Fan C., Lu H., Feng C., He P., Yang X., et al. Protective role of berberine on ulcerative colitis through modulating enteric glial cells-intestinal epithelial cells-immune cells interactions. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:447–461. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy P., Orecchioni M., Ley K. How the immune system shapes atherosclerosis: roles of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:251–265. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00584-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng M., Jiang W., Kim B.Y.S., Zhang C.C., Fu Y.X., Weissman I.L. Phagocytosis checkpoints as new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:568–586. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbott M., Ustoyev Y. Cancer and the immune system: the history and background of immunotherapy. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019;35 doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bedard P.L., Hyman D.M., Davids M.S., Siu L.L. Small molecules, big impact: 20 years of targeted therapy in oncology. Lancet. 2020;395:1078–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ai L., Chen J., Yan H., He Q., Luo P., Xu Z., et al. Research status and outlook of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:3625–3649. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S267433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J., Hu L. Immunomodulators targeting the PD-1/PD-l1 protein‒protein interaction: from antibodies to small molecules. Med Res Rev. 2019;39:265–301. doi: 10.1002/med.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Awadasseid A., Wu Y., Zhang W. Advance investigation on synthetic small-molecule inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2021;282 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li K., Tian H. Development of small-molecule immune checkpoint inhibitors of PD-1/PD-L1 as a new therapeutic strategy for tumour immunotherapy. J Drug Target. 2019;27:244–256. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2018.1440400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konstantinidou M., Zarganes-Tzitzikas T., Magiera-Mularz K., Holak T.A., Domling A. Immune checkpoint PD-1/PD-L1: is there life beyond antibodies? Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57:4840–4848. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng H., Tan S., Gao X., Zou C., Xu C., Tu K., et al. CDK5 knocking out mediated by CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing for PD-L1 attenuation and enhanced antitumor immunity. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:358–373. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu C., Seeram N.P., Ma H. Small molecule inhibitors against PD-1/PD-L 1immune checkpoints and current methodologies for their development: a review. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:239. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01946-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y., Liu X., Zhang N., Yin M., Dong J., Zeng Q., et al. Berberine diminishes cancer cell PD-L1 expression and facilitates antitumor immunity via inhibiting the deubiquitination activity of csn5. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:2299–2312. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X., Guo G., Guan H., Yu Y., Lu J., Yu J. Challenges and potential of PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade immunotherapy for glioblastoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:87. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1085-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X., Pan X., Zhang W., Guo H., Cheng S., He Q., et al. Epigenetic strategies synergize with PD-L1/PD-1 targeted cancer immunotherapies to enhance antitumor responses. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X., Yin M., Dong J., Mao G., Min W., Kuang Z., et al. Tubeimoside-1 induces TFEB-dependent lysosomal degradation of PD-L1 and promotes antitumor immunity by targeting mTOR. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:3134–3149. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu X., Meng Y., Liu L., Gong G., Zhang H., Hou Y., et al. Insights into non-peptide small-molecule inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction: development and perspective. Bioorg Med Chem. 2021;33 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Overman M.J., Lonardi S., Wong K.Y.M., Lenz H.J., Gelsomino F., Aglietta M., et al. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:773–779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.9901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen W., Yuan Y., Jiang X. Antibody and antibody fragments for cancer immunotherapy. J Control Release. 2020;328:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiao P., Geng Q., Jin P., Su G., Teng H., Dong J., et al. Small molecules as PD-1/PD-L1 pathway modulators for cancer immunotherapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24:4911–4920. doi: 10.2174/1381612824666181112114958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin M., Cao Q., Zheng S., Tian Y., Zhang H., Xie J., et al. Discovery of [1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyridines as potent inhibitors targeting the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 interaction. J Med Chem. 2019;62:4703–4715. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Y., Wang K., Chen H., Feng Z. Design, synthesis, evaluation, and sar of 4-phenylindoline derivatives, a novel class of small-molecule inhibitors of the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) interaction. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;211 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.113001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo J., Luo L., Wang Z., Hu N., Wang W., Xie F., et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of linear aliphatic amine-linked triaryl derivatives as potent small-molecule inhibitors of the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 interaction with promising antitumor effects in vivo. J Med Chem. 2020;63:13825–13850. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang T., Cai S., Wang M., Zhang W., Zhang K., Chen D., et al. Novel biphenyl pyridines as potent small-molecule inhibitors targeting the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 interaction. J Med Chem. 2021;64:7390–7403. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng B., Ren Y., Niu X., Wang W., Wang S., Tu Y., et al. Discovery of novel resorcinol dibenzyl ethers targeting the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 interaction as potential anticancer agents. J Med Chem. 2020;63:8338–8358. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun C., Cheng Y., Liu X., Wang G., Min W., Wang X., et al. Novel phthalimides regulating PD-1/PD-L1 interaction as potential immunotherapy agents. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:4449–4460. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng B., Ren Y., Cao H., Chen J. Discovery of novel resorcinol diphenyl ether-based PROTAC-like molecules as dual inhibitors and degraders of PD-L1. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;199 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y., Zhou Y., Cao S., Sun Y., Dong Z., Li C., et al. In vitro and in vivo degradation of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) by a proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) Bioorg Chem. 2021;111 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harikrishnan L.S., Gill P., Kamau M.G., Qin L.Y., Ruan Z., O'Malley D., et al. Substituted benzyloxytricyclic compounds as retinoic acid-related orphan receptor gamma t (RORγt) agonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020;30 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng J., Wang J., Wang Q., Zou H., Wang H., Zhang Z., et al. Targeting castration-resistant prostate cancer with a novel rorgamma antagonist elaiophylin. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:2313–2322. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu X., Liu X., Moisan J., Wang Y., Lesch C.A., Spooner C., et al. Synthetic rorγ agonists regulate multiple pathways to enhance antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1254854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang M.R., Dharmarajan V., Doebelin C., Garcia-Ordonez R.D., Novick S.J., Kuruvilla D.S., et al. Synthetic RORγt agonists enhance protective immunity. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:1012–1018. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu Y., Sun N., Yu M., Guo H., Xie Q., Wang Y. Discovery of aryl-substituted indole and indoline derivatives as RORγt agonists. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;182 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qiu R., Yu M., Gong J., Tian J., Huang Y., Wang Y., et al. Discovery of tert-amine-based RORγt agonists. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;224 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma X., Sun N., Li X., Fu W. Discovery of novel N-sulfonamide-tetrahydroisoquinolines as potent retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor gammat agonists. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;222 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sonawani A., Kharche S., Dasgupta D., Sengupta D. Insights into the dynamic interactions at chemokine-receptor interfaces and mechanistic models of chemokine binding. J Struct Biol. 2022;214 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2022.107877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lai W.Y., Mueller A. Latest update on chemokine receptors as therapeutic targets. Biochem Soc Trans. 2021;49:1385–1395. doi: 10.1042/BST20201114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu R., Yu W., Yao C., Liang Z., Yoon Y., Xie Y., et al. Amide-sulfamide modulators as effective anti-tumor metastatic agents targeting CXCR4/CXCL12 axis. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;185 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nguyen H.H., Kim M.B., Wilson R.J., Butch C.J., Kuo K.M., Miller E.J., et al. Design, synthesis, and pharmacological evaluation of second-generation tetrahydroisoquinoline-based CXCR4 antagonists with favorable adme properties. J Med Chem. 2018;61:7168–7188. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin Y., Li Z., Xu C., Xia K., Wu S., Hao Y., et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel CXCR 4 antagonists based on an aminoquinoline template. Bioorg Chem. 2020;99 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xun Y., Yang H., Li J., Wu F., Liu F. Cxc chemokine receptors in the tumor microenvironment and an update of antagonist development. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;178:1–40. doi: 10.1007/112_2020_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qin L.H., Wang Z.L., Xie X., Long Y.Q. Discovery and synthesis of 6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-pyrido[4,3-c]azepin-5-one-based novel chemotype CCR2 antagonists via scaffold hopping strategy. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018;26:3559–3572. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]