Abstract

Hospital emergency departments (EDs) lack the tools and processes required to facilitate consistent screening and intervention in cases of elder abuse and neglect. To address this need, the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment has developed a clinical care model that ED’s can implement to improve screening, referral, and linkage to coordinated care and support services for older adults who are at risk of mistreatment. To gauge ED readiness to change and facilitate adoption of the care model, we developed an organizational assessment tool, the Elder Mistreatment Emergency Department Assessment Profile (EM-EDAP). Development included a phased approach in which we reviewed evidence on best practice; consulted with multidisciplinary experts; and sought input from ED staff. Based on this formative research, we developed a tool that can be used to guide EDs in focusing on practice improvements for addressing elder mistreatment that are most responsive to local needs and opportunities.

Keywords: elder abuse, elder neglect, elder mistreatment, organizational assessment, emergency department, implementation science, screening, referral, coordinated care

Introduction

Approximately 1 in 10 Americans aged 60 and older experience some form of elder mistreatment each year (Acierno et al., 2010), with estimates ranging as high as 5 million elders mistreated (Connolly et al., 2014). Elder mistreatment results when a caregiver or any other person behaves knowingly, intentionally or negligently in ways that harm or introduce risk of harm to an older adult (National Center on Elder Abuse, n.d.). Mistreatment includes physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, psychological abuse, and financial exploitation; and victims of elder mistreatment frequently experience multiple types at the same time.

Among older adults, victimization is associated with declining physical health and functioning (Burnes et al., 2015; Dong, 2015; Dong & Simon, 2015; Johannesen & LoGiudie, 2013); mental illness (Dong, 2015; Dong et al., 2011; Fulmer et al., 2005); reduced cognitive status (Dong et al., 2014; Friedman et al., 2017); and substance misuse (Conrad et al., 2019). Similarly, older adults reliant on caregivers who have physical health problems (Fulmer et al., 2005), substance misuse (Campbell et al., 2001;Conrad et al., 2019; Jackson et al., 2016) and/or mental disorders (Johannesen & LoGuidie, 2013; Labrum et al., 2015) are more likely to experience mistreatment than their counterparts.

Older adults who experience elder mistreatment are more likely than those who do not to experience depression, anxiety, and psychological distress and worse physical and functional health outcomes (Acierno et al., 2017; Wong & Waite, 2017; Yunus et al., 2019). They also are more likely to engage frequently with health care systems than those who do not experience mistreatment, including presenting to the emergency department (Dong & Simon, 2013a; Lachs et al., 1997), and requiring hospitalization (Dong & Simon 2013c) and nursing home placement (Dong & Simon, 2013b; Lachs et al., 2002). Elders experiencing mistreatment have a three times greater risk of death when compared to those who have not experienced mistreatment (Lachs et al., 1998). The direct medical costs associated with increased morbidity and mortality due to elder mistreatment likely exceed many billions of dollars each year (Dong, 2005; Mouton et al., 2004); and are expected to rise as the baby boomer generation ages.

Such alarming numbers and consequences make the identification of elder mistreatment a major public health priority. Yet, currently, only 1 in 24 cases of abuse is identified and reported to the authorities (Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc. et al., 2011). Hospital emergency department (EDs) visits provide an important potential opportunity to identify older adults who are at risk of or are experiencing mistreatment as well as to report and intervene as appropriate (Rosen et al., 2017). Compared to other older adults, elder mistreatment victims are more likely to visit the ED, often for acute illnesses or injuries, and less likely to see a primary care provider (Rosen, Stern, Elman et al., 2018). Once in the ED, the potential for detection increases as, unlike the primary care setting, multidisciplinary providers assess older adults over several hours, examining, interacting, and observing them (Rosen, Mehta-Naik et al., 2018). As with child abuse and intimate partner violence among younger populations, which EDs are routinely required to address, ED providers also are well-positioned to identify, report, and initiate interventions for suspected elder mistreatment. Yet, elder mistreatment screening and identification is not widely practiced in many EDs across the country, which lack the tools and processes required to facilitate consistent screening and intervention.

To address this need, The John A. Hartford Foundation funded the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment (National Collaboratory) to develop a novel clinical care model that EDs can implement to address elder mistreatment. This model, designed by national experts with input from ED clinicians from multiple disciplines and community-based elder abuse professionals, is currently undergoing feasibility testing in hospital EDs across the country (Stoeckle et al., 2019). The model includes tools and training designed to improve screening, referral, and linkage to coordinated care and support services for older adults who are at risk of mistreatment or likely experiencing mistreatment (Stoeckle et al., 2019; Stoeckle & Bane, 2020).

A critical element of successfully implementing new programs such as the elder mistreatment care model designed by the National Collaboratory involves rigorous, systematic assessment of readiness for change as well as current processes, staff attitudes and knowledge, barriers, and gaps. Research has shown that healthcare professionals find it challenging to implement changes in care practices and service delivery, even when substantial evidence of effectiveness supports such changes (Herr et al., 2004; McGlynn et al., 2003; Nembhard et al., 2009). An organization’s readiness to change exerts substantial influence on the adoption and delivery of innovative health practices (Hagedorn & Heideman, 2010; Holt et al., 2010; Kahn et al., 2014; Kotter, 1995; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982; Weiner, 2009; Weiner et al., 2008). This “readiness for change” involves preparedness to take action in the immediate future (McCluskey & Cusak, 2002; Moulding et al., 1999). Signs of this readiness to improve practices involve assessing whether staff are individually and collectively motivated and capable of implementing aspects of a new program; recognizing that the problem is high-priority and addressing it in a health care environment; and agreeing that the proposed changes to individual staff and hospital protocols will result in improvements in care and patient outcomes (Holt et al., 2010). Additionally, a pre-implementation assessment should include what circumstances are likely to help or hinder implementation of the new model (Holt et al., 2007). This assessment can help identify areas of greatest need and opportunity, gaps which often present as significant differences between what is currently done and a potential more effective approach to screening and response. By identifying such discrepancies, a tension for change emerges (Gustafson et al., 2003). This tension, and the fact that it is specific to a given institution, is what motivates individuals to change their behavior, especially if individuals are provided the tools and guidance to facilitate such change and address gaps. Using the information from this pre-implementation assessment, health care teams may be more likely to develop action plans that successfully facilitate the adoption and implementation of the new protocol (Kotter, 1995; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982).

Further, a formal assessment can help hospitals monitor change or progress made when implementing the new care model and make course corrections as needed. This tool may be administered pre-implementation and on a semi-annual or annual basis to monitor changes in organizational readiness over time, whether the new care model was completely or only partially adopted, and whether there have been any improvements in staff knowledge, professional practice issues, and perceptions of the problem. Additionally, when multiple institutions are administering the tool, these can compare their results with those of other, similar hospitals, to assess their progress toward specific benchmarks.

An example of the potential for important impact of a tool such as this is the Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile (GIAP). More than 300 diverse hospitals (NICHE, 2010) have used the GIAP to: assess institutional readiness to provide best practices in geriatric care (Abraham et al., 1999); evaluate changes in geriatric care before and after implementation of best practice (Fulmer et al., 2002); and compare gaps in knowledge and attitudes about geriatric care, geriatric practice concerns, and hospital characteristics relevant to geriatric care (Kim et al., 2009). Multiple studies have found the GIAP to be a reliable and valid measure of hospital attributes relevant to geriatric care (Abraham et al., 1999; Boltz et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2009, 2010; Kim et al., 2007, 2009; McKenzie et al., 2011).

Similar to the GIAP, the Collaboratory has developed the Elder Mistreatment Emergency Department Assessment Profile (EM-EDAP) to allow hospital EDs to evaluate readiness for change as well as current processes, staff attitudes and knowledge, barriers, and gaps surrounding elder mistreatment in their environment. Here, we describe in detail the rigorous, multi-phase process of developing this institutional assessment tool and present the final version.

Methods

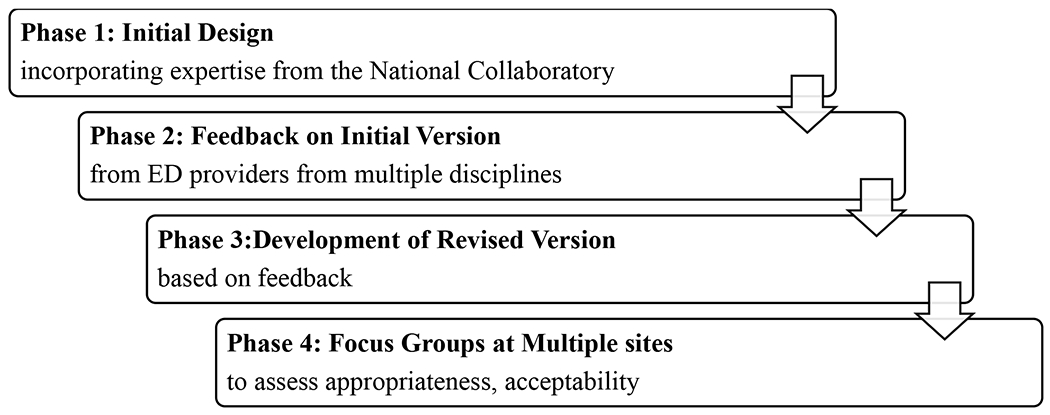

To develop the EM-EDAP, we used a multi-phase process that included formative contributions from national experts and ED staff from multiple disciplines. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Multi-phase development of the EM-EDAP

In Phase 1, we developed a preliminary version with input from members of the National Collaboratory, whose membership includes those with expertise in elder mistreatment prevention, management, and reporting; emergency medicine; geriatric care; implementation science; and program evaluation. We modeled the EM-EDAP on the Geriatric Institutional Assessment Protocol (GIAP), a self-report survey designed to assess a hospital’s readiness to implement a geriatric program in the hospital setting (Abraham et al., 1999). A review of the GIAP and its implementation shows a high degree of specificity, conformity, appropriateness, and utility in the evaluation of nurses’ perceptions of geriatric care (Tavares & da Silva, 2013). The EM-EDAP also draws upon a 2016 survey of ED provider knowledge, attitudes, and practices around elder mistreatment developed at Weill Cornell Medicine as well as extant literature on best practices in (Rosen et al., 2016; Rosen, Mehta-Naik et al., 2018; Rosen, Stern, Elman et al., 2018; Rosen et al., 2019) and barriers to (Reingle Gonzalez et al., 2018; Rosen, Stern, Mulcare et al., 2018) addressing elder mistreatment in the ED. Based on input from this group, we developed a tool that hospital EDs could administer online so that ED staff would be able to complete it at their convenience. This was felt to be less burdensome and would allow for automated participant recruitment, data collection, and reporting. Members of the Collaborative who work in hospital EDs suggested that the EM-EDAP should take no longer than 10 to 15 minutes to complete to be acceptable to ED providers, and would result in higher response rates. The preliminary tool developed in Phase 1 with this expert input included 19 main questions and 70 items overall. Three open-ended questions asked about training received and desired on identifying, managing, and reporting elder mistreatment and pressing issues related to addressing elder mistreatment in the ED. Sixty-seven closed-ended items assessed staff background, knowledge, attitudes, and practice related to elder mistreatment as well as staff perceptions of the ED practice environment, and staff perceptions of service quality provided to patients at-risk for or experiencing elder mistreatment.

In Phase 2, we sought input on the preliminary EM-EDAP version from ED providers working in a mid-size, suburban community hospital located outside of New York City. We selected this particular ED because it serves a large population of older adults (41% of patients seen in the ED were aged ≥65), and has no formal elder mistreatment protocols. Such specialized input was considered crucial in the early stages of development given concerns about surveying health professionals working in fast-paced environments, and the extent to which the EM-EDAP reflected best practice in and barriers to recognizing and addressing elder mistreatment in the ED. We conducted a focus group with 10 ED physician and nurse participants, including academic and clinical leaders as well as interviews with a case manager and a physician expert in geriatric emergency medicine. Focus group and interview participants provided feedback on appropriateness of content, readability, and length using a semi-structured questionnaire. Specifically, ED staff were asked: whether questions would make sense to all ED staff, not just nurses and physicians; what changes to wording are required so that tool will fit multiple ED contexts (e.g., hospitals with or without geriatric nurses or sexual assault nurse examiners, hospitals with or without ED social work on all shifts); how they would implement the tool in hospital EDs (e.g., staff who would oversee implementation); and suggestions for overcoming those challenges to implementing the assessment.

Overall, feedback from focus group(s) and interview participants was that the EM-EDAP was clear and would be relatively easy to implement in hospital ED settings, but they emphasized that it needed to be shortened. Respondents thought that staff from multiple disciplines should complete the tool to get the best possible picture of the institution. These disciplines included ED nurses, ED attending and resident physicians, advanced practice providers, as well as in-patient social workers and case managers. If possible, they recommended that other ED staff members, such as patient care technicians, clerks, and patient escorts should also complete it as their perceptions of care could provide valuable insight. ED staff noted that in some hospitals services including ED-based social work and case management is available during the day and evenings but not overnight or on weekends. Therefore, it was suggested that ED staff on all shifts complete the EM-EDAP to highlight any differences in institutional readiness or barriers based on shift. ED staff participating in focus groups and interviews also recommended that inpatient staff should complete the institutional assessment as many elder mistreatment victims identified in the ED are admitted to the hospital, requiring the inpatient team to take over and execute any intervention plan or connections to services within the community. Participants agreed that online administration was appropriate and emphasized the importance of ED nurse and physician leadership championing the EM-EDAP or making completion mandatory to maximize participation. They also offered comments on several individual items that should be removed, re-worded, or added.

In Phase 3, members of the National Collaboratory used this clinician input to revise the EM-EDAP. These revisions included adding questions to address differences in care provided during the day and night shifts (i.e., how hospital ED staff handle suspected cases of elder mistreatment that present overnight) and ensuring that questions included were relevant to all staff as well as providing response options that include “not applicable.” We also shortened the assessment by removing eight items participants identified as repetitive or that could be answered by accessing hospital records. Finally, we added an open-ended question suggested in the focus group that asks, “When you suspect elder mistreatment, what do you do next?” to identify variation in responses to cases of elder mistreatment by EDs. We also recognized that input from a single ED in the initial phase of development may have introduced bias about what constitutes readiness to address elder mistreatment. Therefore, we advanced to another round of review with additional hospital ED staff.

In Phase 4, 20 ED staff and administrators at three hospitals participated in 60 – 90-minute focus groups led by National Collaboratory members to assess appropriateness and acceptability to ED staff of this revised and shortened instrument. Participating hospitals, which were chosen to ensure viewpoints apart from those obtained from a suburban community hospital, were situated in the northeastern and southwestern regions of the U.S., and included two large, urban teaching hospitals as well as a rural, 135-bed community-based hospital. At each site, the following staff participated: ED nurses, physicians, physician’s assistants, community health workers, and emergency services directors. During Phase 4, focus group participants were asked to complete the assessment and then respond to the same semi-structured questionnaire as in Phase 2. Overall impressions were that the revised assessment could be completed in 9 – 12 minutes; was useful and easy to implement; and could be completed using a smart phone. Participants recommended integrating the assessment into existing online training platforms when possible. Participants also noted how the assessment made them think about the kinds of practices they should be implementing but that they and their colleagues were not.

Results

Based on the formative research described above, the final version of the EM-EDAP includes 20 main questions and 61 items altogether that measure structural and psychological dimensions of readiness to change. The items included are shown in Table 1. In keeping with Holt and colleagues’ (2010) definition of readiness to change, structural factors are the circumstances under which new protocols for addressing elder mistreatment are occurring; and psychological factors are staff attitudes and beliefs about those new protocols as they relate to existing practices. Questions ask staff to identify their beliefs about the need and their ability to address elder mistreatment in the ED. Questions assess ED staff members’ collective commitment and efficacy to address elder mistreatment, asking whether ED staff routinely implement specific practices to address elder mistreatment. The EM-EDAP asks about general staff knowledge, skills, and capability to address elder mistreatment in the ED acquired through training. There also are questions about human and material resources, communication channels, and formal policy or procedures that may affect staff abilities to address elder mistreatment. These questions are framed as barriers often cited by ED staff and the research literature (Reingle Gonzalez et al., 2018; Lees et al., 2018; Rosen, Stern, Mulcare et al., 2018) and as access to and availability of community resources required to adequately respond to suspected cases of elder mistreatment identified.

Table 1.

EM-EDAP items by domain

| Background | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Main Category | Subcategory |

| Position in Hospital ED | • Medical (e.g., physicians, physician assistant) • Nontechnical Support (e.g., registration, patient services) • Nursing (nurse, nurse practitioner) • Organization and oversight (administration) • Pharmacy (pharmacist) • Religious (chaplain) • Social Work (e.g., social worker, care coordinator) • Technical Support (e.g., patient care technician) |

| Experience | • Years working in position • Years in position at current hospital ED • Frequency of overnight ED shift work |

| Psychological Readiness to Change | |

|

| |

| Main Category | Subcategory |

|

| |

| Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about ED screening for EM | • Screening for elder mistreatment (EM) in a hurried context • Viewing EM as a common/serious public health problem • Screening all older adults for mistreatment • Implementing best practices for identifying cases of suspected EM |

| Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about ED response to EM | • Knowing whom to contact to report suspected cases • Reporting EM to proper authorities • Understanding laws surrounding confidentiality, anonymity, and personal liability for reporting • Feeling that reports are taken seriously • Monitoring victims after they are discharged • Wanting to know the outcome of reported EM investigations • Handling suspected cases of EM that present at night • Implementing best practices for managing cases of suspected EM |

| Attitudes and beliefs about community response to EM | • Community resources available to prevent/respond to EM • Multidisciplinary teams assess and manage EM programs to support caregivers suspected of EM • Police receptive and helpful in EM cases • Adult protective services (APS) receptive and helpful in EM cases |

| Formal education or training on EM | • Formal education on EM detection, management, or reporting • Type of training received • Perceptions about training adequacy • Interest in more training in EM detection, management, or reporting • Preferences for additional training focus |

| Personal efficacy to address EM in the ED | • Reported frequency of recognizing/missing EM • Confidence in ability to recognize, intervene, and report EM • Actions taken when elder EM is suspected (open-ended) • To whom cases of EM are reported in the hospital ED |

| Structural Readiness to Change | |

|

| |

| Main Category | Subcategory |

|

| |

| Perceptions about screening for EM in ED | • ED medical and nursing staff routinely screen older patients for EM. |

| Perceptions about ED staff training to address EM | • ED medical and nursing staff are trained to recognize/intervene in suspected EM cases. • Hospital educates ED staff to handle suspected EM cases. |

| Perceived structural barriers to identifying and managing EM in the hospital ED | • Awareness of EMS concerns about home environment • Lack of time to conduct a thorough evaluation • Difficulty distinguishing mistreatment from accidental trauma, illness, or quality of care issues • Lack of (or inadequate) protocol for EM response • Differences of opinion among staff regarding intervention in EM cases • Reliance on family members or caregivers for medical and social historical information • Communication difficulties with older adults (e.g., due to cognitive or hearing impairment) • Lack of specialized community services for older adults vulnerable to mistreatment • Limited follow-up by APS when cases are reported • Lack of basic training and knowledge of EM • Perceptions about most pressing issues faced in caring for older adults who have been mistreated (open-ended) |

| Perceptions about whether staff in the hospital ED implement best practices to address EM | • Photographing injuries and other physical findings potentially related to EM and adding the photographs to the medical chart • Engaging a multidisciplinary team of experts in assessing suspected EM • Developing safety plans with older adults who are at risk of or who have experienced mistreatment • Reporting suspected cases of EM to appropriate authorities • Referring victims of EM to appropriate community resources • Referring alleged EM perpetrators to appropriate community resources • Monitoring victims of EM after discharge for adherence to referral or care plans • Admitting victims of EM for safety or social reasons despite the absence of a medical indication for hospitalization • Holding potential victims of EM, who present during the night shift, until morning when a social worker or case manager is on duty |

Discussion

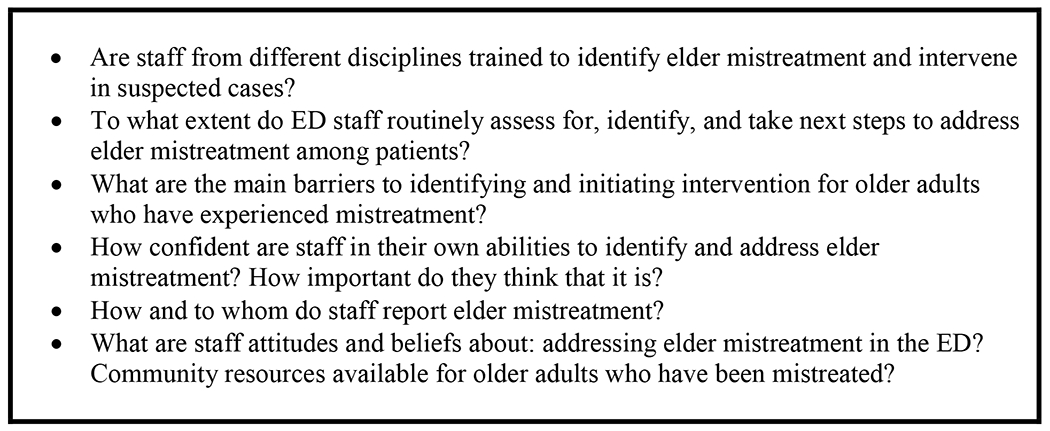

Our aim was to develop a tool that hospitals can use to promote improvements to hospital ED systems and practices for identifying and managing older adults at risk of or experiencing mistreatment. Our formative research resulted in a tool that assesses and profiles needs and opportunities for addressing elder mistreatment in hospital EDs by examining screening, intervention, reporting, and follow-up practices related to elder mistreatment. The EM-EDAP measures factors likely to influence adoption of elder mistreatment care models—staff knowledge, attitudes, and efficacy related to elder mistreatment; staff perceptions of the ED practice environment; and staff perceptions of service quality provided to patients at risk of or experiencing elder mistreatment. These items in the EM-EDAP are meant to highlight helping and hindering factors that align with aspects of the care protocol for addressing elder mistreatment: identifying and intervening in cases of elder mistreatment, reporting cases of elder mistreatment to proper authorities, and referring or connecting older adults (and, in some cases, their caregivers) to community resources. By aligning questions and items in the assessment to the care model elements, we are able to determine the extent to which hospitals are ready—from a behavioral and structural perspective—to implement the innovation and address any factors that might hasten readiness. Using the EM-EDAP helps EDs and hospitals answer many questions about their staff and institutions, including those shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The EM-EDAP helps answer these questions about ED care

Despite our attention to phased, expert- and user-informed development, there are limitations to our methods and the resulting EM-EDAP tool that are worth noting. First, focus group and interview participants self-selected into formative research activities led by members of the National Collaboratory and experts on elder mistreatment at their respective hospitals and, while we felt that expert facilitation was warranted to maximize valuable information, we acknowledge that participants may have been reluctant to criticize drafts and might have held back on recommendations for extensive modification in the presence of such expertise. Second, although we aimed to create a tool that all ED staff can complete, we remain concerned that staff other than those who provide medical, nursing, and social work services, may not be able to respond to most items given the nature of their job roles. We added response options of “no opinion” and “not applicable” to encourage tool completion. However, because focus groups did not include these populations, it is not clear how applicable questions are to their ED experiences and perceptions. Through field-testing, we should be able to determine whether all ED staff are able to complete the assessment tool or if EDs can validly collect only subsections of data from disciplines other than medicine, nursing, and social work. Third, we have yet to test the psychometric properties of the assessment instrument. Therefore, we cannot make any claims about the reliability, validity, and accuracy of the information that the EM-EDAP will generate to guide decision-making.

More extensive testing of the EM-EDAP will likely help us address the limitations noted above. Currently, we are piloting the EM-EDAP with partner clinical sites in Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, and Texas, results of which will be reported in a subsequent manuscript. We have been working with these hospital emergency departments to develop recruitment strategies, identify eligible staff for EM-EDAP participation, and disseminate the EM-EDAP to staff via automated invitation that includes a link to complete the assessment using a secure online survey platform.

To facilitate sharing of findings to promote practice change, we also have developed reporting templates—full and one-page brief reports—for summarizing EM-EDAP findings so that they can be shared with hospital administration and staff to prioritize and motivate change. We anticipate that these reports will present aggregate data for each hospital ED—frequencies, percentages, and mean scores on items and scales organized by the following topic areas specific to identifying, managing, and reporting suspected elder mistreatment: ED staff training; implementation of best practices in the ED; barriers to practice; ED staff efficacy to implement best practices;staff attitudes and beliefs about addressing elder mistreatment in the ED; and availability of community resources for elder mistreatment. In addition to presentation of descriptive statistics on responses to each item, these reports may include bivariate analyses examining differences in responses by discipline, day vs. night shift work, and years of experience.

Conclusion

We have created an institutional assessment tool designed to evaluate readiness for change, barriers, and gaps to help facilitate the implementation of a new care model for addressing elder mistreatment in hospital EDs. Informed by implementation science, research on best practice in and barriers to addressing elder mistreatment in the hospital ED and with input from experts and frontline staff, the tool is designed to be completed in 10 minutes and can provide hospitals with actionable information to guide practice improvement.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This project was supported by grants from The John A. Hartford Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Health Foundation for Western and Central New York.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

References

- Abraham IL, Botrell MM, Dash KR, Fulmer TT, Mezey MD, O’Donnell L, & Vince-Whitman CV (1999). Profiling care and benchmarking best practice in care of hospitalized elderly: The Geriatric Institutional Profile. Nursing Clinics of North America, 34(1), 237–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, & Kilpatrick DG (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 292–297. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada MA, Anetzberger GJ, Loew D, & Muzzy W (2017). The National Elder Mistreatment Study: An 8-year longitudinal study of outcomes. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 29(4), 254–269, 10.1080/08946566.2017.1365031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Bowar-Ferres S, Norman R, Secic M, Kim H, Fairchild S, Mezey M, & Fulmer T (2008a). Changes in the geriatric care environment associated with NICHE (Nurses Improving Care for HealthSystem Elders). Geriatric Nursing, 29(3), 176–185. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Bowar-Ferres S, Norman R, Secic M, Kim H, Fairchild S, Mezey M, & Fulmer T (2008b). Hospital nurses’ perception of the geriatric nurse practice environment. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40(3), 282–289. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Kim H, Fairchild S, & Secic M (2009). Test-retest reliability of the Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile. Clinical Nursing Research, 18(3), 242–252. 10.1177/1054773809338555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Capezuti E, Kim H, Fairchild S, & Secic M (2010). Factor structure of the Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile’s professional issues scales. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 3(2), 126–34. 10.3928/19404921-20091207-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnes D, Pillemer K, Caccamise PL, Mason A, Henderson CR, & Lachs MS (2015). Prevalence of and risk factors for elder abuse and neglect in the community: A population-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(9), 1906–1912. 10.1111/jgs.13601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Reay AM, & Browne KD (2001). Risk factor characteristics in carers who physically abuse or neglect their elder dependents. Aging and Mental Health, 5(1), 56–62. 10.1080/13607860020020654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly M, Brandl B, & Breckman R (2014). Elder justice roadmap report. A stakeholder initiative to respond to an emerging health, justice, and financial social crisis. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/file/852856/download [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KJ, Liu PJ, & Iris M (2019). Examining the role of substance abuse in elder mistreatment: Results from mistreatment investigations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(2), 366–391. 10.1177/0886260516640782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X (2005). Medical implications of elder abuse and neglect. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 21(2), 293–313. 10.1016/j.cger.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X (2015). Elder abuse: Systematic review and implications for practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(6), 1214–1238. 10.1111/jgs.13454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, & Simon MA (2013a). Association between elder abuse and use of ED: findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 31(4), 693–698. 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, & Simon MA (2013b). Association between reported elder abuse and rates of admission to skilled nursing facilities: Findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Gerontology, 59(5), 464–472. 10.1159/000351338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, & Simon MA (2013c). Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, 173(10), 911–917. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, & Simon M (2015). Association between elder abuse and metabolic syndromes: Findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Gerontology, 61(5), 389–398. 10.1159/000368577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Simon MA, Beck TT, Farran C, McCann JJ, & Evans DA (2011). Elder abuse and mortality: The role of psychologial and social wellbeing. Gerontology, 57(6), 549–555. 10.1159/000321881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Simon MA, Rajan K, & Evans DA (2014). Decline in cognitive function and elder mistreatment: Findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(6), 598–605. 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LS, Avila S, Rizvi T, Partida R, & Friedman D (2017). Physical abuse of elderly adults: Victim characteristics and determinants of revictimization. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(7), 1420–1426. 10.1111/jgs.14794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer T, Mezey M, Bottrell M, Abraham I, Sazant J, Grossman S, & Grisham E (2002). Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE): Using outcomes and benchmarks for evidenced-based practice. Geriatric Nursing, 23(3), 121–127. 10.1067/mgn.2002.125423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer T, Paveza G, VandeWeerd C, Fairchild S, Guadagno L, Bolton-Blatt M, & Norman R (2005). Dyadic vulnerability and risk profiling for elder neglect. The Gerontologist, 45(4), 525–524. 10.1093/geront/45.4.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Sainfort F, Eichler M, Adams L, Bisognano M, & Steudel H (2003). Developing and testing a model to predict outcomes of organizational change. Health Services Research, 38(2), 751–776. 10.1111/1475-6773.00143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn HJ, & Heideman PW (2010). The relationship between baseline organizational readiness to change assessment subscale scores and implementation of hepatitis prevention services in substance use disorders treatment clinics: A case study. Implementation Science, 5(46). 10.1186/1748-5908-5-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr K, Titler MG, Schilling ML, Marsh JL, Xie X, Ardery G, Clarke WR, & Everett LQ (2004). Evidence-based assessment of acute pain in older adults: Current nursing practices and perceived barriers. Clinical Journal of Pain, 20(5), 331–340. 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DT, Armenakis AA, Harris SG, & Feild HS (2007). Toward a comprehensive definition of readiness for change: A review of research and instrumentation. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 16, 289–336. 10.1016/S0897-3016(06)16009-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DT, Helfrich CD, Hall CG, & Weiner BJ (2010). Are you ready? How health professionals can comprehensively conceptualize readiness for change. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(Suppl 1), 50–55. 10.1007/s11606-009-1112-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SL (2016). All elder abuse perpetrators are not alike: The heterogeneity of elder abuse perpetrators and implications for intervention. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(3), 265–285. 10.1177/0306624X14554063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesen M, & LoGiudie D (2013). Elder abuse: A systematic review of risk factors in community-dwelling elders. Age and Ageing, 42(3), 292–298. 10.1093/ageing/afs195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Timmings C, Moore JE, Marquez C, Pyka K, Gheihman G, & Straus SE (2014). The development of an online decision support tool for organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science, 9, 56. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Capezuti E, Boltz M, & Fairchild S (2009). The nursing practice environment and nurse-perceived quality of geriatric care in hospitals. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 31(4), 480–495. 10.1177/0193945909331429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Capezuti E, Boltz M, Fairchild S, Fulmer T, & Mezey M (2007). Factor structure of the geriatric care environment scale. Nursing Research, 56(5), 339–347. 10.1097/01.NNR.0000289500.37661.aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotter JP (1995). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review 73, 59–67. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2 [Google Scholar]

- Labrum T, Solomon PL, & Bressi SK (2015). Physical, financial, and psychological abuse committed against older women by relatives with psychiatric disorders: Extent of the problem. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 27(4–5), 377–391. 10.1080/08946566.2015.1092902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Hurst L, Kossack A, Siegal A, & Tinetti ME (1997). ED use by older victims of family violence. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 30(4), 448–454. 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, & Pillemer KA (2002). Adult protective service use and nursing home placement. Gerontologist, 42(6), 734–739. 10.1093/geront/42.6.734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, & Charlson ME (1998). The mortality of elder mistreatment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280(5): 428–432. 10.1001/jama.280.5.428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees KE, Lang D, Graham A, Burnett J, Olsen B, Sivers-Teixeira T, Rosen T, & Elman A (2018, November 15). An environmental scan of empirical and practice-based evidence to inform care model development. Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, & New York City Department for the Aging. (2011). Under the radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study. http://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey A, & Cusick A (2002). Strategies for introducing evidence-based practice and changing clinician behavior: A manager’s toolbox. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 49(2), 63–70. 10.1046/j.1440-1630.2002.00272.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro, & Kerr EA (2003). The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(26), 2635–2645. 10.1056/NEJMsa022615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie JA, Blandford AA, Menec VH, Boltz M, & Capezuti E (2011). Hospital nurses’ perceptions of the geriatric care environment in one Canadian health care region. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43(2), 181–187. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01387.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulding N, Silagy C, & Weller D (1999). A framework for effective management of change in clinical practice: Dissemination and implementation of clinical practice guideline. Quality in Health Care, 8(3), 177–83. 10.1136/qshc.8.3.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton CP, Rodabough RJ, Rovi SLD, Hunt JL, Talamantes MA, Brzyski RG, & Burge SK (2004). Prevalence and 3-year incidence of abuse among postmenopausal women. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 605–612. 10.2105/ajph.94.4.605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Elder Abuse. (n.d.). Resources: Frequently asked questions. https://ncea.acl.gov/FAQ.aspx

- Nembhard IM (2009). Why does quality of health care continue to lag? Insights from management research. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(1), 24–42. 10.5465/AMP.2009.37008001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE). (2010). The NICHE benchmarking service: The Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile (GIAP). New York University College of Nursing. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NICHE2014website/NICHE+Benchmarking_GIAP+Scales+%26+Subscales.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kotter JP (1995). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review 73, 59–67. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2 [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, & DiClemente CC (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 19(3), 276–288. 10.1037/h0088437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reingle Gonzalez JM, Cannell MB, Jetelina KK, & Radpour S (2016). Barriers in detecting elder abuse among emergency medical technicians. BMC Emergency Medicine, 16(1), 36. 10.1186/s12873-016-0100-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Elman A, Dion S, Delgado D, Demetres M, Breckman R, Lees K, Dash K, Lang D, Bonner A, Burnett J, Dyer CB, Snyder R, Berman A, Fulmer T, & Lachs M (2019). Review of programs to combat elder mistreatment: Focus on hospitals and level of resources needed. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(6), 1286–1294. 10.1111/jgs.15773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Elman A, Mulcare MR, & Stern ME (2017). Recognizing and managing elder abuse in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine, 49(5), 200–207. 10.12788/emed.2017.0028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Hargarten S, Flomenbaum NE, & Platts-Mills TF (2016). Identifying elder abuse in the emergency department: Toward a multidisciplinary team-based approach. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 68(3), 378–382. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Mehta-Naik N, Elman A, Mulcare MR, Stern ME, Clark S, Sharma R, LoFaso VM, Breckman R, Lachs M, & Needell N (2018). Improving quality of care in hospitals for victims of elder mistreatment: Development of the Vulnerable Elder Protection Team. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 44(3), 164–171. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Stern ME, Elman A, & Mulcare MR (2018). Identifying and initiating intervention for elder abuse and neglect in the emergency department. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 34(3), 435–451. 10.1016/j.cger.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Stern ME, Mulcare MR, Elman A, McCarthy TJ, LoFaso VM, Bloemen EM, Clark S, Sharma R, Breckman R, & Lachs MS (2018). Emergency department provider perspectives on elder abuse and development of a novel ED-based multidisciplinary intervention team. Emergency Medicine Journal, 35(10), 600–607. 10.1136/emermed-2017-207303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckle RJ, & Bane S (2020). The National Collaboratory on Elder Mistreatment. Generations, 44(1), 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckle RJ, Lees-Haggerty K, Dash K, Lachs M, Mosqueda L, Bonner A, & Dyer C (2019). The National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment: A collective impact approach. Innovation in Aging, 3(Suppl 1), S74. 10.1093/geroni/igz038.289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares JP, & da Silva AL 2013. Use of the Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile: An integrative review. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 6(3), 209–220. 10.3928/19404921-20130304-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ (2009). A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science, 4, 67. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ, Amick H, & Lee SY (2008). Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: A review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Medical Care Research and Review, 65(4), 379–436. 10.1177/1077558708317802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JS, & Waite LJ (2017). Elder mistreatment predicts later physical and psychological health: Results from a national longitudinal study. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 29(1), 15–42. 10.1080/08946566.2016.1235521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunus RM, Hairi NN, & Choo WY (2019). Consequences of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review of observational studies. Trauma Violence Abuse, 20(2), 197–213. 10.1177/1524838017692798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.