Abstract

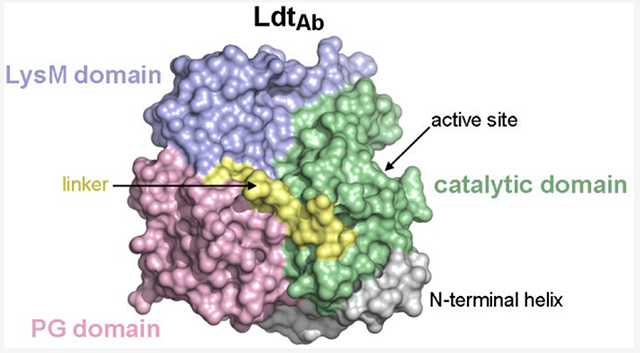

l,d-Transpeptidases (LDTs) are enzymes that catalyze reactions essential for biogenesis of the bacterial cell wall, including formation of 3–3 cross-linked peptidoglycan. Unlike the historically well-known bacterial transpeptidases, the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), LDTs are resistant to inhibition by the majority of β-lactam antibiotics, with the exception of carbapenems and penems, allowing bacteria to survive in the presence of these drugs. Here we report characterization of LdtAb from the clinically important pathogen, Acinetobacter baumannii. We show that A. baumannii survives inactivation of LdtAb alone or in combination with PBP1b or PBP2, while simultaneous inactivation of LdtAb and PBP1a is lethal. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of all 13 β-lactam antibiotics tested decreased 2- to 8-fold for the LdtAb deletion mutant, while further decreases were seen for both double mutants, with the largest, synergistic effect observed for the LdtAb + PBP2 deletion mutant. Mass spectrometry experiments showed that LdtAb forms complexes in vitro only with carbapenems. However, the acylation rate of these antibiotics is very slow, with the reaction taking longer than four hours to complete. Our X-ray crystallographic studies revealed that LdtAb has a unique structural architecture and is the only known LDT to have two different peptidoglycan-binding domains.

Keywords: peptidoglycan; cell wall; l,d-transpeptidase; β-lactam; crystal structure

Graphical Abstract

The cell wall determines bacterial shape, provides protection against high intracellular osmotic pressure and fluctuating environmental conditions, and plays an important role in division.1 Its major constituent, peptidoglycan, is composed of polymerized glycan strands of two alternating sugars, N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM), that are linked by β-1,4 glycosidic bonds. These glycan strands are cross-linked through peptide stems attached to each NAM unit and form a net-like macropolymeric structure that surrounds the cytoplasmic membrane of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Formation of cross-links between glycan strands of peptidoglycan is catalyzed by enzymes such as d,d-transpeptidases (DDTs), which are also widely known as penicillinbinding proteins or PBPs.2,3 While the mechanism of DDT-mediated cross-linking has been studied in many bacterial species, the most detailed information was gained for the Gram-negative pathogen, Escherichia coli. In this bacterium, cross-linking is performed by five different DDTs that crosslink the fourth residue (d-alanine) of the pentapeptide donor of one peptidoglycan chain to the third residue (mesodiaminopimelic acid or mDAP) of the acceptor tetrapeptide of another peptidoglycan chain, resulting in formation of the 4–3 or d,d-type bond. It was subsequently demonstrated that DDTs from other bacteria also generate 4–3 cross-linked peptidoglycan.

Deciphering of the peptidoglycan structure of various microorganisms also demonstrated the presence, in many of them, of 3–3 cross-linked peptidoglycan. The amount of this type of cross-link in bacterial species varies significantly, from 6–15% in E. coli4–6 to 60–80% in Clostridium difficile and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.7,8 Although the existence of 3–3 cross-links in peptidoglycan was established in the 1980s, the first enzyme (Ldtfm) catalyzing the 3–3 cross-linking reaction was discovered almost two decades later in the ampicillin-resistant laboratory mutant of the Gram-positive bacterium, Enterococcus faecium.9,10 Since that time, LDTs were identified in multiple bacterial species, and it was shown that they are encoded by chromosomally located genes whose number in different microorganisms varies from one to more than a dozen.11

Unlike DDTs, which use an active site serine residue as the nucleophile to catalyze the formation of 4–3 cross-linked peptidoglycan, LDTs utilize a cysteine to cross-link the third residue (mDAP) of the tetrapeptide donor chain of one peptidoglycan chain to the third residue (mDAP) of the acceptor tetrapeptide or tripeptide of another peptidoglycan chain, resulting in 3–3 or l,d-type cross-links.12,13 It was also shown that some LDTs do not form 3–3 cross-links, but catalyze other reactions. In E. coli, which produces six different LDTs, it was demonstrated that only two of them are responsible for the formation of 3–3 cross-links, while the other four perform cross-linking of the Braun lipoprotein to peptidoglycan and cleavage of these cross-linked species, or catalyze replacement of the terminal d-Ala residue in the donor tetrapeptides with noncanonical amino acids.14–19 LDTs differ from DDTs not only in their catalytic mechanism but also in their structural architecture. Currently, structural information is available for around 70 LDTs, which include both apo enzymes and complexes with their cell wall substrates and β-lactam antibiotics.12,13,20–24

Peptidoglycan is unique to bacteria and is essential for survival, which makes it an ideal target for development of antibiotics. Among drugs targeting various steps of bacterial cell wall biosynthesis, β-lactams constitute the largest and most commonly used class of antibiotics. They efficiently inhibit DDTs, which results in severe impairment of cell wall integrity and ultimately leads to bacterial death. Due to their broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity and low toxicity, β-lactam antibiotics of various classes (penams, cephems, penems, carbapenems, and monobactams) have been successfully used over the last eight decades for treatment of patients with a wide range of bacterial infections. However, over time, bacteria have developed and utilized various defensive mechanisms, allowing them to withstand the deleterious effects of β-lactam antibiotics. These mechanisms include production of β-lactam-degrading enzymes, β-lactamases, mutational alterations of their targets, DDTs, mutations hindering penetration of the drugs through the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, and activation of efflux pumps transporting antibiotics from the cell back to the milieu.25 It was demonstrated that LDTs also can contribute to bacterial resistance to β-lactams, as they are not efficiently inhibited by the majority of these drugs, with the exception of carbapenems.12,23,24,26–30 Consequently, this allows bacterial pathogens to survive in the presence of many β-lactams, as they can maintain the integrity of their cell wall by increasing formation of 3–3 cross-linked peptidoglycan, to compensate for the decrease of 4–3 cross-linked species resulting from inhibition of DDTs.26,31

Contribution of LDTs to bacterial survival in the presence of β-lactams underlines the importance of studies of these enzymes in clinically important bacterial pathogens. One such pathogen is Acinetobacter baumannii, which is notorious for its resistance to a wide range of antibiotics, including β-lactams.32 Such multidrug-resistant A. baumannii isolates cause deadly infections characterized by extremely high mortality rates.33 It was recently shown that the cell wall of A. baumannii contains 3–3 cross-linked peptidoglycan, and a search for enzymes that could perform 3–3 cross-linking in this pathogen identified two candidates, ACX60-RS05685 and ElsL, which both possess a YkuD-like domain characteristic for LDTs.34 Subsequent characterization of these enzymes (called LdtJ and LdtK, respectively) demonstrated that LdtJ is indeed an l,d-transpeptidase whose inactivation abolishes production of 3–3 cross-links, while function of LdtK was not unequivocally established.35 It was also shown by transposon mutagenesis that LdtJ is essential for bacterial survival in the absence of just a single DDT, PBP1a. We recently showed that LdtJ can sustain the growth of an A. baumannii mutant in which activity of all three individual DDTs (PBP1a, PBP1b, and PBP2) responsible for the peripheral peptidoglycan synthesis in this pathogen are inactivated.36 Analysis of the cell wall muropeptide composition of this A. baumannii triple mutant demonstrated that decrease in the amount of d,d-cross-linked muropeptide is compensated by a significant increase of the l,d-cross-linked species. Very recently, it was established that ElsL (also known as LdtK) is not an LDT but rather a cytoplasmic l,d-carboxypeptidase, a member of a previously unidentified class of cell wall recycling enzymes.37 This study demonstrated that the A. baumannii genome encodes only a single LDT, which the authors renamed from LdtJ to LdtAb.

Due to the utmost clinical importance of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii and lack of detailed information regarding the recently discovered LdtAb, in this manuscript we evaluated the role of this enzyme in A. baumannii growth and resistance to antibiotics. We also studied its interaction with β-lactams using mass spectrophotometry and solved its X-ray crystal structure.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Inactivation of A. baumannii LdtAb.

To evaluate effect of LdtAb inactivation on bacterial growth and susceptibility to antibiotics, we deleted its gene from the genome of A. baumannii CIP 70.10, an important β-lactam-susceptible fully sequenced reference strain that is often used to study antibiotic resistance in this species.38 For the gene deletion, we utilized a two-step homologous recombination protocol (described in the Methods and ref 39) with derivatives of the suicide vector pMo130 (Supplementary Table S1), which were constructed using primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. We also attempted to construct double mutants that, in addition to the deleted gene for LdtAb, had one of the three nonessential A. baumannii DDT genes (PBP1a, PBP1b, or PBP2) deleted or inactivated. We succeeded in generation of two such mutants, ΔLdtAb+PBP1b(S/A) and ΔLdtAb+ΔPBP2, but failed to obtain the ΔLdtAb+PBP1a(S/A) mutant, demonstrating that such combination is lethal, as was previously reported by using transposon mutagenesis.35 These data show that simultaneous inactivation of the LdtAb and PBP1a function may prove to be a valuable, new strategy to target A. baumannii, including multidrug-resistant isolates.

Effect of Loss of LdtAb Alone or in Combination with DDTs on A. baumannii Growth.

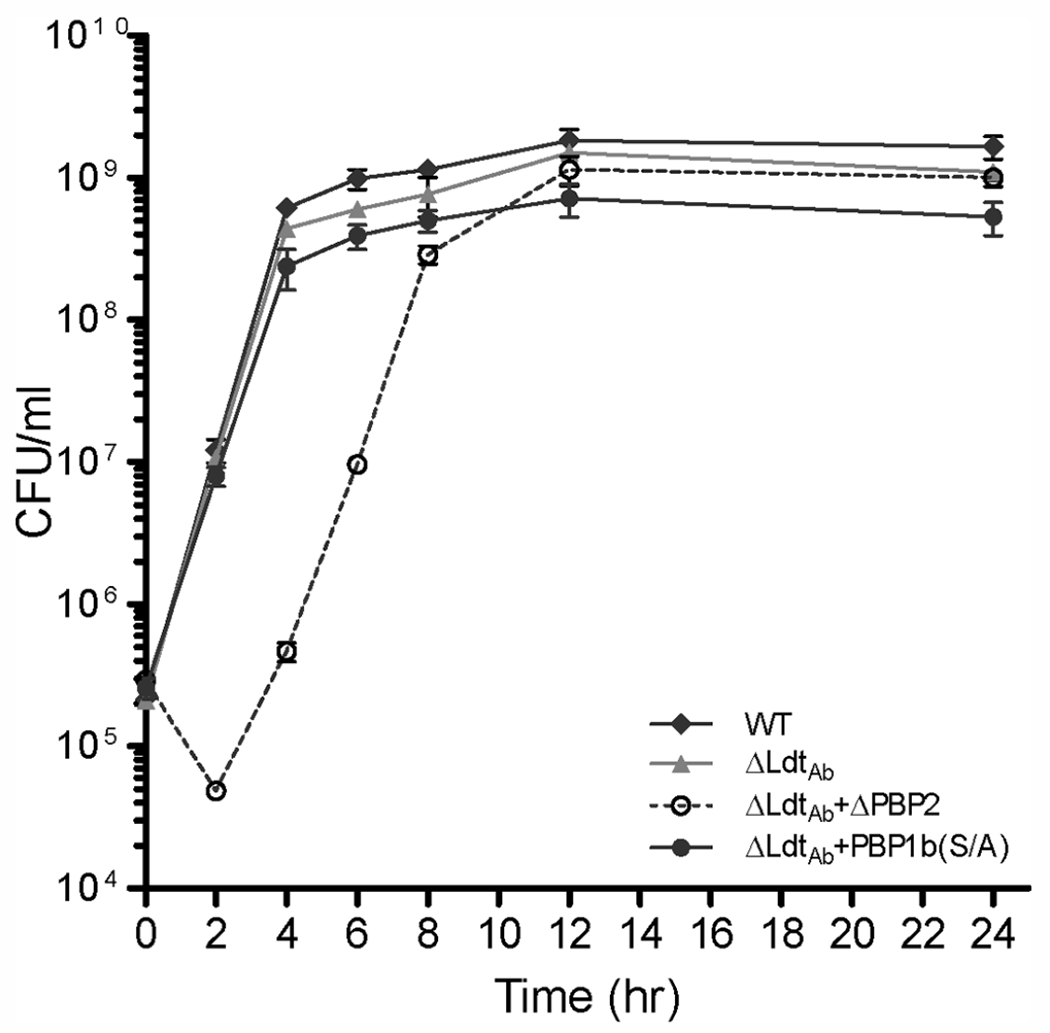

Growth curves for the wild-type parental strain and ΔLdtAb and ΔLdtAb+PBP1b(S/A) mutants were very similar in the logarithmic phase of growth; however, in the stationary phase both mutants grew slightly slower (in the order: ΔLdtAb+PBP1b(S/A) slower than ΔLdtAb) and had lower CFU/mL than the parental strain (Figure 1). In a recent publication, it was also shown that the ΔLdtAb mutant of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 had a similar growth rate as the parental strain.37 In contrast, growth of the ΔLdtAb+ΔPBP2 mutant of A. baumannii CIP 70.10 was affected more dramatically. We observed a significant (~5-fold) decrease in the number of viable cells during the first two hours of incubation. As a result, it took this mutant approximately four hours to reach the same CFU/mL it had at the start of the experiment. After the first four hours, we observed a transition of this mutant’s growth to the exponential and subsequently stationary phases, and its growth curve was similar in shape to those of the other two mutants and the parental strain. These results show that simultaneous deletion of the genes for LdtAb and PBP2 of A. baumannii is more detrimental to the bacteria than just deletion of the LdtAb gene alone or in combination with inactivation of PBP1b.

Figure 1.

Growth curves of A. baumannii CIP 70.10 and its mutant strains. WT, wild type; Δ, deletion of the corresponding protein; PBP, penicillin-binding protein; (S/A), Ser-to-Ala substitution in the transpeptidase domain of PBP1b.

Susceptibility of A. baumannii Mutants to Antibiotics.

To assess whether deletion of the A. baumannii CIP 70.10 LdtAb gene alone or in combination with loss of DDT function affects its susceptibility to antimicrobial agents, we determined the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 16 antibiotics against the pathogen. They included thirteen β-lactams of various classes, the aminoglycoside kanamycin, the fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline as a representative of the tetracycline class of drugs (Table 1). Deletion of the gene for LdtAb alone reduced MICs of all β-lactams tested by 2-to 8-fold, with the largest decrease observed for the penicillin mecillinam and cephalosporin cephalothin. MICs for all carbapenems decreased by 4-fold. In contrast, deletion of the LdtAb gene had no effect on susceptibility to non-β-lactam antibiotics, except for ciprofloxacin, for which we observed a 2-fold decrease in the MIC value. Whether this is due to some decrease in cell wall integrity is not clear, as the MICs of two other non-β-lactams, tetracycline and kanamycin, remained unchanged. For the ΔLdtAb+PBP1b(S/A) mutant, MICs of six β-lactams decreased 2-fold, and the MIC of cefoxitin decreased 4-fold, while MICs for the remaining six β-lactams and three non-β-lactams remained unchanged when compared to the single ΔLdtAb mutant (Table 1). These data indicate that combination of the single ΔLdtAb and PBP1b(S/A) mutants to produce the double mutant results in an additive effect on the susceptibility of A. baumannii to β-lactams. Simultaneous deletion of the LdtAb and PBP2 genes (the ΔLdtAb+ΔPBP2 mutant; Table 1) resulted in the largest decreases in MIC values overall. When compared to the ΔLdtAb mutant, MICs of all β-lactams (with exception of mecillinam) decreased by 2- to 8-fold. The ΔLdtAb+ΔPBP2 mutant was significantly more susceptible to β-lactam antibiotics than the wild-type parental strain A. baumannii CIP 70.10. The largest decrease in MIC values was observed for cephalosporins (8- to 32-fold) and, more importantly, for carbapenems (8- to 16-fold), which are considered last resort drugs for the treatment of many serious infections. The magnitude of the observed changes in MIC values of the double mutant when compared to those of the single ΔLdtAb and ΔPBP2 mutants indicates that simultaneous deletion of their genes synergistically increases susceptibility of A. baumannii CIP 70.10 to β-lactams. These data further indicate that LdtAb is a prospective target for the development of novel antibiotics, as not only simultaneous inhibition of LdtAb and PBP1a is lethal, but also loss of both LdtAb and PBP2 function significantly renders A. baumannii vulnerable to already existing β-lactams. Of note, introduction of the double ΔLdtAb+ΔPBP2 gene deletion in A. baumannii also had a more pronounced effect on MICs of non-β-lactam antibiotics; the MIC of kanamycin decreased 4-fold and that of ciprofloxacin decreased 2-fold compared to the parental strain, while the MIC of tetracycline remained unchanged.

Table 1.

Antibiotic Susceptibilities of A. baumannii CIP 70.10 and Its Transpeptidase Mutant Strains

| MICs (μg/mL)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| antibiotics | controlb | PBP1b(S/A)b | ΔPBP2b | ΔLdtAb | ΔLdtAb+PBP1b(S/A) | ΔLdtAb+ΔPBP2 |

| AMX | 32 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| AMP | 32 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 |

| PIP | 64 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 16 |

| MEC | 1024 | 512 | 1024 | 128 | 64 | 128 |

| CEF | 1024 | 1024 | 1024 | 128 | 128 | 32 |

| CAZ | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| CRO | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 0.5 |

| FOX | 128 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 16 | 16 |

| IPM | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.062 | 0.031 | 0.015 |

| MEM | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.062 |

| DOR | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.062 | 0.031 | 0.015 |

| ERT | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| ATM | 64 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| KAN | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| CIP | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| TET | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

The control was A. baumannii CIP 70.10; ΔPBP2, deletion of the gene for PBP2; PBP1b(S/A), Ser-to-Ala substitution in the transpeptidase domain of PBP1b; ΔLdtAb, deletion of the gene encoding the l,d-transpeptidase; AMX, amoxicillin; AMP, ampicillin; PIP, piperacillin; MEC, mecillinam/amdinocillin; CEF, cephalothin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CRO, ceftriaxone; FOX, cefoxitin; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; DOR, doripenem; ERT, ertapenem; ATM, aztreonam; KAN, kanamycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TET, tetracycline.

Published earlier36 except MICs of AMX, CEF, MEC, and TET.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis of the Interaction between LdtAb and β-Lactams.

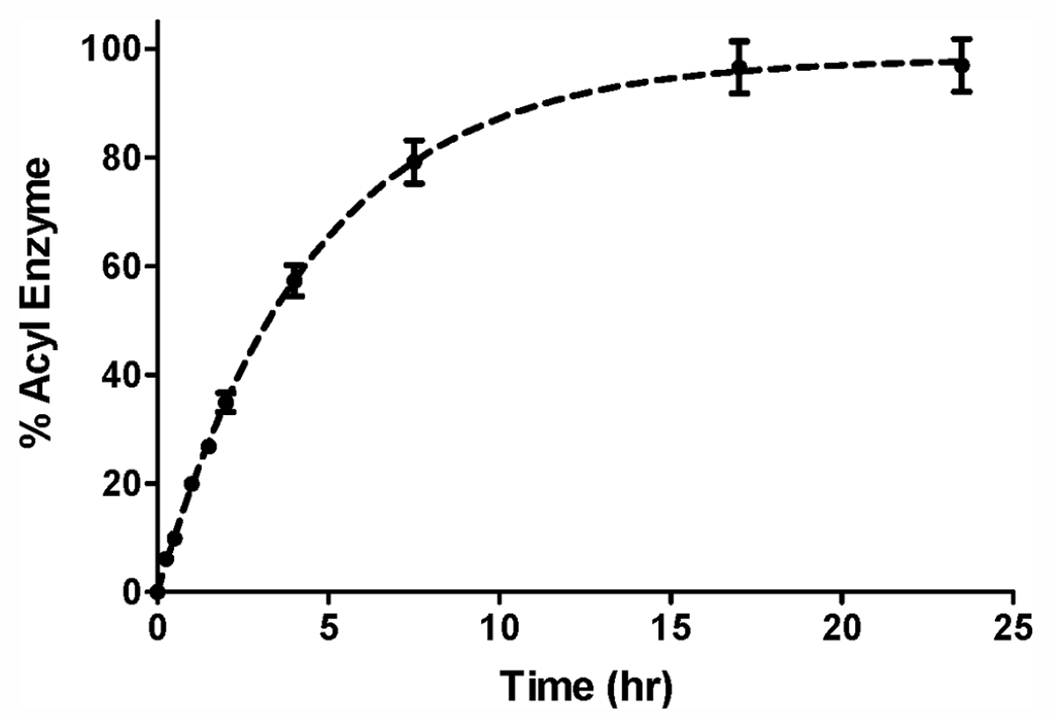

To gain a better understanding of how LdtAb contributes to β-lactam resistance in A. baumannii, we investigated the kinetics of its interaction in vitro with various β-lactam antibiotics. We tried to perform classical competition experiments with commonly used reporter substrates such as nitrocefin and bocillin. However, we found that the reaction with these substrates was very slow (acylation of LdtAb by nitrocefin took more than six hours to reach completion; data not shown), which would preclude their utility for these types of measurements. Therefore, we examined the interaction directly using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC-MS) with an excess of antibiotics. For incubation times up to 18 h, no acyl-enzyme complex was observed with the penicillin ampicillin, the cephalosporins cefotaxime and ceftazidime, and the monobactam aztreonam. For the carbapenems meropenem, imipenem, doripenem, and ertapenem, a small amount (maximum of 30% for ertapenem) was observed after one hour of incubation. Acylation was almost complete after 18 h for both ertapenem and imipenem, where 97 and 95% of the total LdtAb was in the acyl-enzyme complex, while for meropenem and doripenem, the amounts of acyl-enzyme complex comprised 48 and 21%, respectively. In all cases, we also observed a small amount of a species that was 44 Da smaller than the acyl-enzyme complex. This could result from loss of either carbon dioxide at the C3 position or the hydroxyethyl group at the C6 position of the carbapenem, as was previously reported for their interaction with LDTs from other bacteria and class A, C, and D β-lactamases.27,40–43 Since acylation was the most efficient with ertapenem, we used this antibiotic to measure the apparent acylation rate constant k2, which was found to be 0.22 ± 0.01 h−1 (Figure 2); this would result in one acylation event every four and a half hours. These results demonstrated that LdtAb is acylated in vitro only by carbapenems, albeit at a very slow rate. The rate of acylation is much slower than the A. baumannii CIP 70.10 doubling time (22 ± 0.4 min36) and, thus, is physiologically irrelevant. We next investigated whether the LdtAb-ertapenem complex was capable of deacylation. Using LC-MS, we found that after 20 h nearly all the enzyme (95%) was still in the acyl-enzyme complex, showing that no or very little deacylation had taken place during this time frame. These results showed that formation of the LdtAb-ertapenem complex is either irreversible or deacylation occurs at an incredibly slow rate.

Figure 2.

Kinetics of acylation of LdtAb by ertapenem determined by LC-MS.

There are only several reports of acyl-enzyme formation between LDTs from Gram-negative bacteria and β-lactams.23,24,26,27 Similar to our results, in all cases complexes were observed with carbapenems. For the LDT YcbB from E. coli, MS experiments showed full, irreversible acylation with meropenem and imipenem after one hour, while the observed YcbB-ceftriaxone complex was slowly hydrolyzed, and no acyl-enzyme complex was detected with ampicillin.26 In another report, LDT-like enzymes of unknown function from Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were cloned and evaluated for their ability to interact with β-lactams.27 After five hours of incubation, MS showed all three formed complexes with faropenem, while the enzyme from E. cloacae also formed complexes with cephalothin and doripenem, and that from K. pneumoniae formed a complex with doripenem; none of the enzymes formed complexes with amoxicillin. Formation of complexes with carbapenems has also been shown crystallographically for several LDTs, including the E. coli YcbB-meropenem complex,23 and the ertapenem complexes with YcbB from Salmonella Typhi and Citrobacter rodentium.24 These results are somewhat in contrast to those for LDTs from Gram-positive bacteria, where carbapenems, penems, and, to a lesser extent, cephalosporins have been reported to inactivate these enzymes.12 Though it is generally accepted that carbapenems are inhibitors of LDTs, the results of our study show these drugs only very poorly acylate LdtAb in vitro. This highlights the need for discovery of new efficient inhibitors of LdtAb from the important pathogen, A. baumannii. Furthermore, more detailed kinetic studies of LDTs from other Gram-negative bacteria of clinical relevance are warranted.

The LdtAb Crystal Structure.

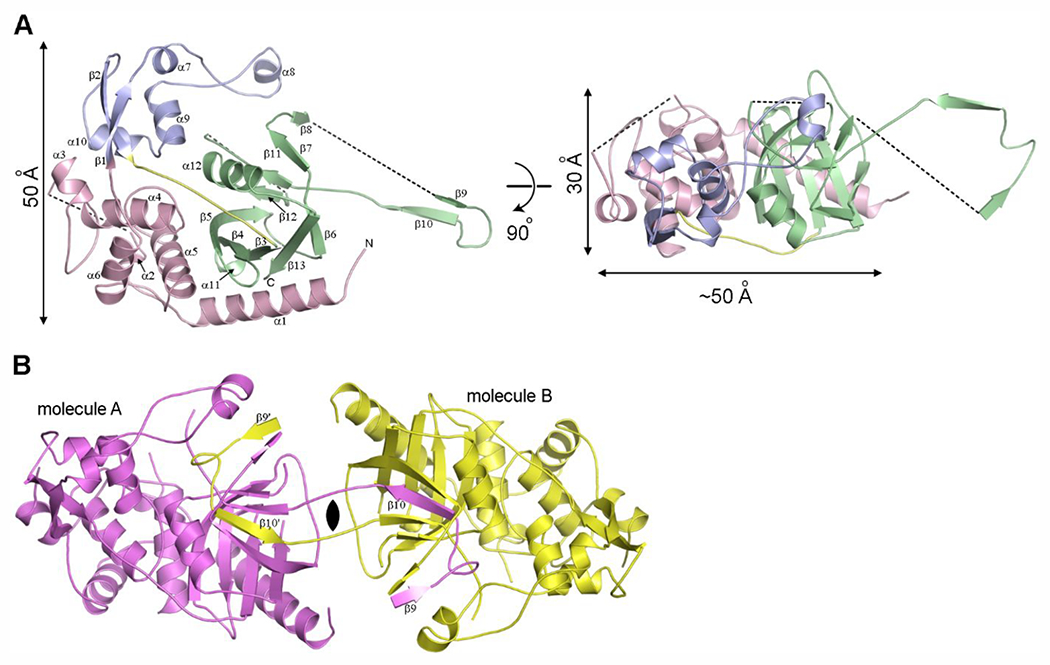

The LdtAb structure was solved by iodide-single wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) and refined at 2.6 Å resolution, which is similar to the resolution reported for other large LDTs (Supplementary Table S3). The LdtAb enzyme can be best described as a diskshaped, three-domain structure that measures approximately 50 Å by 30 Å in size (Figure 3A). Domain-1 (amino acid residues 37–179) consists of a long N-terminal helix (α1) followed by a small globular domain made up of a 310 helix (α2) and four α-helices (α3-α6). Domain-2 (residues 180–248) comprises three helices (α7, α9, α10), two β-strands (β1, β2), and a long loop formed by two extended pieces of polypeptide bracketing a 310 helix (α8). Finally, Domain-3 (residues 260–393) is composed of nine β-strands arranged into two β-sheets (β3, β4, β6, β13, and part of β5; β7, β10–β12, and part of β5) and is connected to Domain-2 by a ten-residue linker (residues 249–259) (Figure 3A). A visual inspection indicated that Domain-3 is a canonical LDT catalytic domain, with a fold consistent with the catalytic domain observed in all LDT structures.13,22–24,27,44–46

Figure 3.

The structure of LdtAb. (A) Ribbon representation of LdtAb colored by the structural domains; Domain-1 in pink, Domain-2 in blue, and Domain-3 (the catalytic domain) in green. The 10-residue linker connecting Domain-2 to the catalytic domain is shown in yellow. The black dashed lines indicate loops that are not visible in the electron density. The structure on the right is rotated approximately 90° relative to the structure on the left. (B) The crystallographic dimer generated from the LdtAb monomer (molecule A, magenta) showing the domain-swapped β9-loop-β10 motif from molecule A embedded in the symmetry-related molecule B (yellow).

Early in the structure building stages it was observed that part of the catalytic domain (strand β10 and a peripheral strand β9) crosses into a symmetry-related molecule and then folds back into the main molecule in a domain-swapping event, which could indicate dimer formation (Figure 3B; see Supplementary Methods for description of domain swapping analysis). However, native mass spectrometry experiments only showed presence of LdtAb as a monomer and did not indicate any formation of a dimer in solution (Supplementary Figure S1). Since crystals took a very long time to appear (more than one year), we surmise that domain-swapping and dimerization occurred very slowly, possibly as a result of partial dehydration of the drops over extended time, and that the dimerization observed in crystallo is probably not the natural state of the enzyme in vivo.

The Domain Structure of LdtAb.

Currently, there are around 70 LDT structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (www.rcsb.org), with more than 50 of them from M. tuberculosis. These structures can be grouped into nine general conformations (Supplementary Figure S2). Since the enzymes from M. tuberculosis have only the canonical catalytic domain in common with all other LDTs, we will limit our structural comparison of LdtAb to enzymes from Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria.

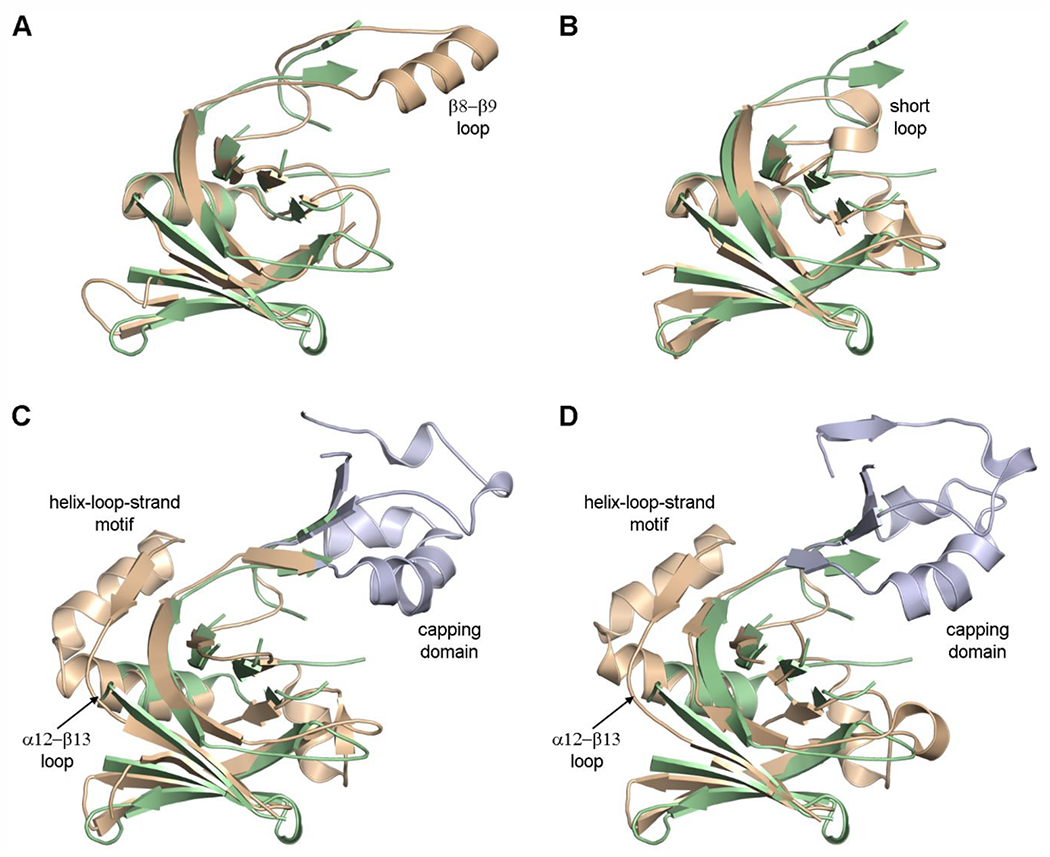

Superposition of known LDT structures onto the LdtAb catalytic domain shows that the nine β-strands comprising the two β-sheets of the canonical LDT catalytic fold are highly spatially conserved in the A. baumannii enzyme (Figure 4). Rather surprisingly, the catalytic domain of LdtAb is structurally most similar (rmsd of 1.4 Å) to the Bacillus subtilis YkuD catalytic domain as opposed to the equivalent domains from Gram-negative LDTs (rmsds ranging from 1.6 Å to 2.8 Å). Two loop regions show structural variability among the LDT enzymes. The region between strands β8 and β9 (in LdtAb numbering) varies greatly in length from a very short loop in the B. subtilis YkuD enzyme, a 13-residue loop in LdtAb, up to a large 50-residue insertion in the Gram-negative YcbB enzymes from E. coli, C. rodentium, S. Typhi, and Vibrio cholerae (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S3). In the YcbB enzymes, this insertion has been designated as the capping subdomain, and it was suggested that it is involved in substrate binding and release.23,24 A second region of variability is between helix α12 and strand β13 (LdtAb numbering). In LdtAb, the K. pneumoniae YbiS enzyme, and all of the Gram-positive LDTs, this loop is a short two-or three-residue turn leading from the helix into the strand (Figures 4A and 4B), whereas the YcbB enzymes all have a 25-residue insertion comprising an extra turn of helix α12 and an additional helix-loop-strand motif before leading back into the equivalent of strand α13 (Figures 4C and 4D).

Figure 4.

The LDT catalytic domain. (A) Superposition of LdtAb (green ribbons) on K. pneumoniae YbiS (tan, PDB ID 4LZH). In the latter enzyme, the β8–β9 loop is a single α-helix. (B) Superposition of LdtAb (green ribbons) on B. subtilis YkuD (tan, PDB ID 1Y7M). (C) Superposition of LdtAb (green ribbons) on E. coli YcbB (tan, PDB ID 6NTW). (D) Superposition of LdtAb (green ribbons) on C. rodentium YcbB (tan, PDB ID 7KGM). In panels C and D the large capping domains are colored light blue, and the location of the second insertion is shown as the helix-loop-strand motif.

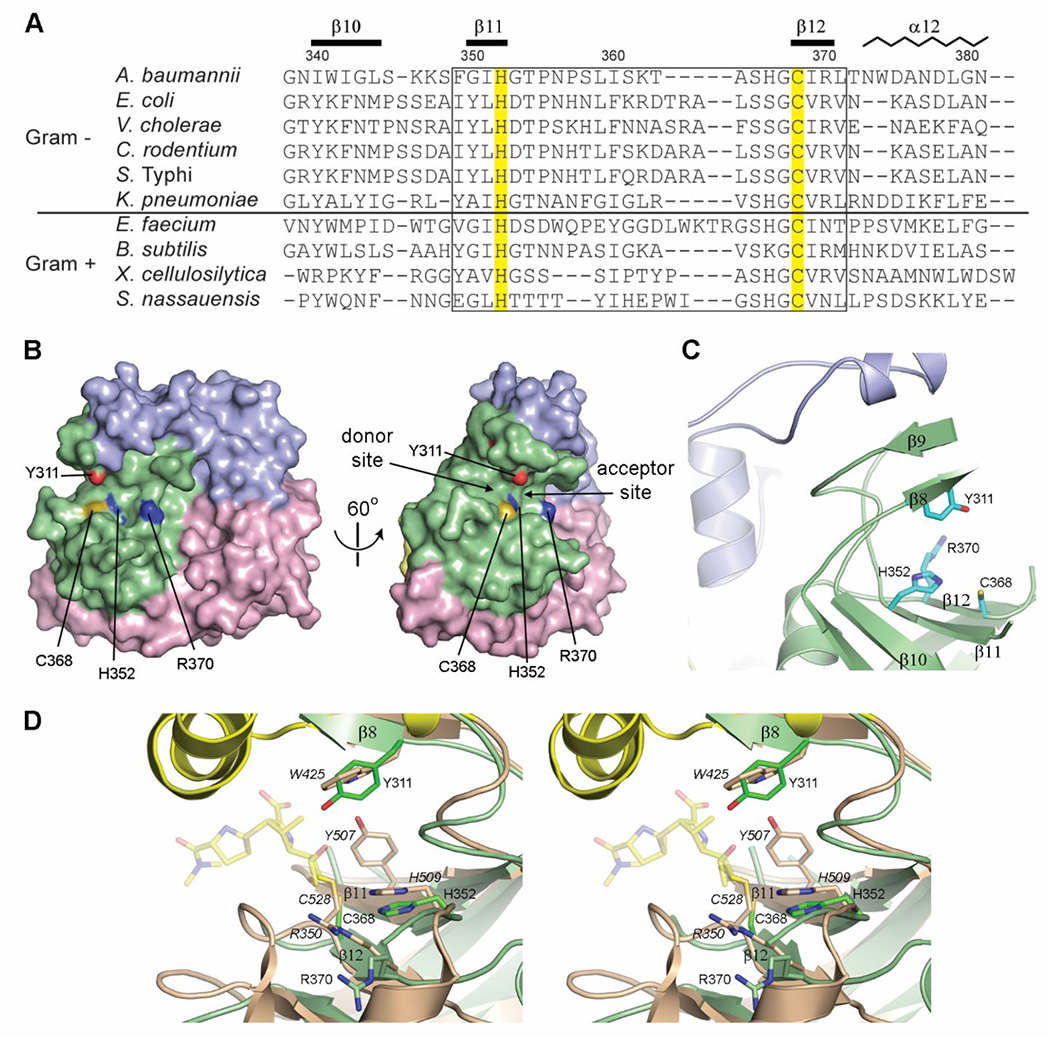

All LDTs that are involved in 3–3 cross-linking of peptidoglycan possess an extended active site for binding of donor and acceptor glycan strands.23 The donor region of the active site, which also interacts with some μ-lactam antibiotics, is identified by the highly conserved sequence motif HxX11SXGCh(R/N)47 (where x denotes either a Gly, Ala, or Ser, X represents any residue, and h is a small hydrophobic residue). In LdtAb this sequence motif (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure S3) is located in a shallow groove at the edge of the catalytic domain (Figure 5B), formed by strands β10, β11, and β12 (Figure 5C). The two catalytic residues, His352 and Cys368, are spatially conserved when compared to all of the other known LDT structures, and delineate the border between the donor and acceptor regions of the active site (Figure 5B). However, when compared to the other known Gram-negative LDTs, there are several distinct differences in the LdtAb donor region of the active site (Figure 5D). In the YcbB enzymes that are involved in peptidoglycan cross-linking, a conserved tyrosine residue at position 350 (in LdtAb numbering) (Figure 5A) was suggested to be the general base in protonation of the leaving group.23 The A. baumannii enzyme has a glycine residue at this position; however, another tyrosine residue (Tyr311), located on strand β8 from the opposite side of the active site cleft, could contribute to the catalytic mechanism in a similar manner.

Figure 5.

The LdtAb active site. (A) Partial structure-based sequence alignment of the active site of known Gram-positive and Gram-negative LDTs. The two catalytic residues are highlighted yellow. The secondary structure and residue numbering for LdtAb are shown above the sequences. The fingerprint LDT catalytic motif is indicated by the box. (B) Surface representation of LdtAb (left) and the same representation rotated by 60° on the right. The two catalytic residues (His352 and Cys368) delineate the donor and acceptor regions of the active site. (C) The LdtAb active site. (D) Stereoview of the LdtAb active site (light green ribbons and sticks) superimposed onto the E. coli YcbB LDT-ertapenem acyl-enzyme complex (light brown ribbons and sticks, with ertapenem shown in semitransparent yellow sticks, PDB ID 6NTW). The catalytic residues are indicated (E. coli labels are given in italics) along with the conserved Arg370 (Arg350 in E. coli). A tyrosine residue thought to be involved in protonation of the leaving groups in the E. coli enzyme (Tyr507) is spatially equivalent to a glycine (Gly350) on strand β11 (not shown for clarity) in LdtAb. A tyrosine residue (Tyr311) in LdtAb, in the equivalent position as a tryptophan in E. coli (Trp425), is near the catalytic residues and could play the same role postulated for Tyr507 in E. coli.

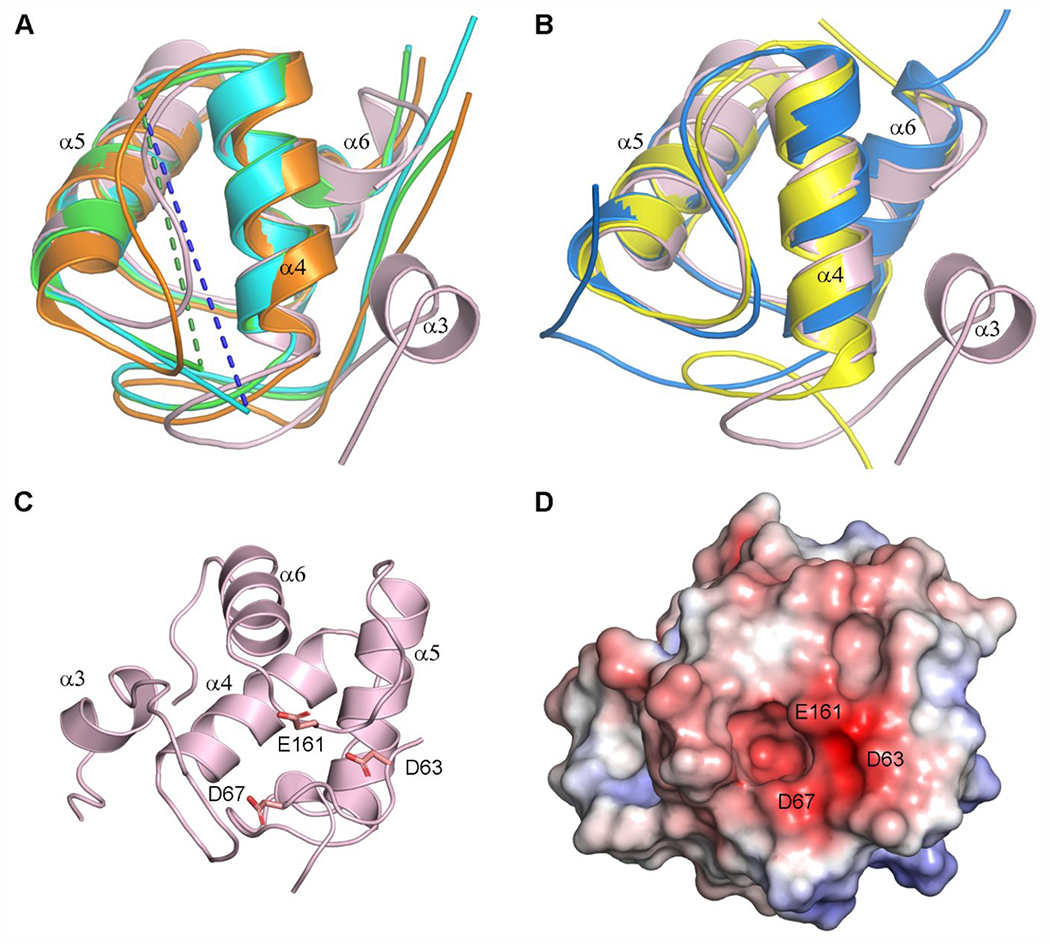

Domain-1 of LdtAb has structural similarity with the peptidoglycan-binding (PG) domains observed in other LDTs. Superposition of the PG domains (Figures 6A and 6B) onto LdtAb Domain-1 shows that the three antiparallel α-helices of the canonical PG domain fold are structurally conserved, with rmsds for the helical regions ranging from 0.7 to 1.0 Å. Structural variability is observed at the N-terminus of the three-helix bundle, and between the first and second helices (α4 and α5 in LdtAb; Figures 3A and 6). In LdtAb, this loop comprises 12 residues and is isostructural with the equivalent loops in the two Gram-positive enzymes (Figure 6B). In the E. coli, C. rodentium, and S. Typhi YcbB enzymes, this loop is long (between 43 and 56 residues) and disordered, although YcbB from V. cholerae has a 15-residue loop that is more similar to that from LdtAb (Figure 6A). It has been suggested that a conserved aspartate residue on the loop between the second and third helices (α5 and α6 in LdtAb), along with an arginine near the N-terminus, might be involved in peptidoglycan binding, based upon a structural comparison between several PG domains.48 The LdtAb PG domain does not have an equivalent aspartate or arginine, although there is a glutamate residue on the α5–α6 loop and two additional acidic residues nearby (Figure 6C), which form an extensive negatively charged patch on the surface of the domain (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Structural comparisons of the LdtAb PG domain. (A) Superposition of the LdtAb PG domain (pink ribbons) against the equivalent domains in the LDTs from E. coli (green, PDB ID 6NTW), C. rodentium (cyan, PDB ID 7KGM), and V. cholerae (orange, PDB ID 7AJ9). The helices are labeled according to LdtAb secondary structure nomenclature. Missing α4–α5 loops in the E. coli and C. rodentium enzymes are indicated by green and blue dashed lines. (B) Superposition of the LdtAb PG domain (pink ribbons) against the equivalent domains in the LDTs from X. cellulosilytica (yellow, PDB ID 4LPQ) and S. nassauensis (blue, PDB ID 5BMQ). The helices are labeled according to LdtAb secondary structure nomenclature. (C) Ribbon representation of the LdtAb PG domain (pink) showing three clustered acidic residues. (D) Electrostatic surface representation of the LdtAb PG domain in the same orientation as panel C. A negatively charged surface patch resulting from the clustering of the three acidic residue is indicated.

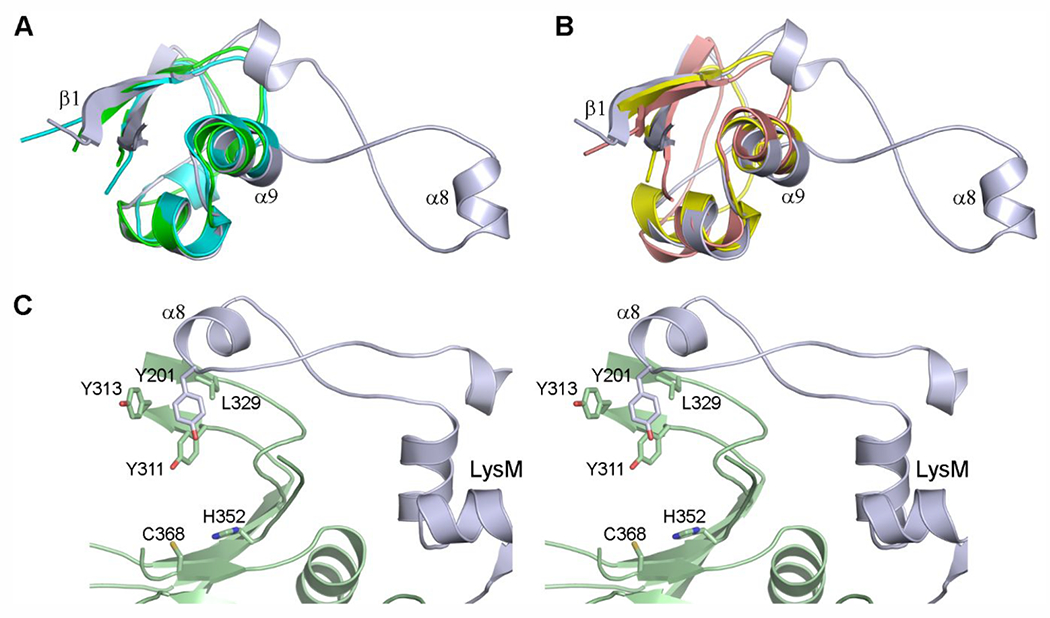

The LdtAb Domain-2 is a small globular domain composed of antiparallel β-strands and two short α-helices. Structural comparison of this domain with all known LDT structures revealed that only the B. subtilis YkuD enzyme (1Y7M) has a domain with a similar structure, described as a putative LysM domain.22 The small globular domain, typically comprised of 45–65 residues, was originally identified in a muramidase from Enterococcus hirae,49 and has since been found in a wide range of extracellular proteins, where it is used in anchoring proteins to chitin or peptidoglycan.50,51 Superposition of the LdtAb Domain-2 against the LysM domains from several LysM-containing enzymes (Figures 7A and 7B) shows that the spatial disposition of the helices and strands that make up the domain is highly conserved. However, the LysM domain of LdtAb differs from all other LysM domains in that there is an insertion of approximately 27 residues in the loop between the first strand (β1) and first helix (α9). This insertion folds as two long unstructured pieces of polypeptide flanking a 310 helix (α8) (Figure 3A and Figure 7). In other known LysM domains, this loop is always a short two-residue turn connecting the first strand and the first helix. The 27-residue loop insertion in LdtAb extends across the surface of the catalytic domain (Figure 3A). The side chain of Tyr201 on helix α8 at the end of the loop interacts with a cluster of hydrophobic residues from strands β8 and β9 in the catalytic domain (Figure 7C). These strands, together with helix α8, form a “pseudo-cap” adjacent to the active site, in a similar location to the capping subdomains described for the YcbB LDTs from E. coli,23 C. rodentium, and S. Typhi.24 For YcbB it was suggested that this capping subdomain plays a role in regulating release of the cross-linked peptidoglycan product from the active site.23,24 The smaller “pseudo-cap” in LdtAb may play a similar role in product release, which could be mediated via the connection between the “pseudo-cap” and the LysM domain.

Figure 7.

Structural comparison of the LdtAb LysM domain. (A) Superposition of the LdtAb LysM domain (light blue ribbons) against the LysM domains from P. ryukyuensis Chitinase A (green, PDB ID 4PXV) and the LDT YkuD from B. subtilis (cyan, PDB ID 4A1I). (B) Superposition of the LdtAb LysM domain (light blue ribbons) against the LysM domains from the T. thermophilus d,l-endopeptidase NlpC/P60 (yellow, PDB ID 4XCM) and the E. coli lytic murein transglycosylase Mltd (pink, PDB ID 1E0G). (C) Stereoview of the hydrophobic interaction between helix α8 at the end of the extended loop from the LysM domains (light blue) and residues from strands β8 and β9 from the catalytic domain (light green ribbons). The location of the active site is indicated by the side chains of His352 and the catalytic cysteine, Cys368.

Domain Architecture of the LDTs.

While all LDT enzymes have multidomain structures, it is evident that the spatial disposition of these domains varies greatly (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S3). This variability is not necessarily correlated to the LDTs’ function (e.g., peptidoglycan cross-linking or attachment of Braun lipoprotein) or whether the enzymes are from Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria. Comparison of the large peptidoglycan cross-linking YcbB enzymes from four different Gram-negative bacteria, E. coli, C. rodentium, S. Typhi, and V. cholerae, shows they are nearly structurally identical. All four microorganisms belong to the class Gammaproteobacteria, while the first three are even more closely related, all belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. It was thus somewhat surprising that the structure of LdtAb from Gram-negative A. baumannii, which also belongs to the class Gammaproteobacteria and performs the same function (peptidoglycan crosslinking), is different in size, domain composition, and domain spatial disposition (Supplementary Figure S2). The structures of the four highly similar YcbB enzymes are composed of the canonical catalytic domain with a capping subdomain, a ubiquitous α-helical PG domain characteristic of both Gramnegative and Gram-positive enzymes, and a scaffolding domain. LdtAb is smaller in size, and comprises the catalytic domain and the PG domain, but does not have a scaffolding domain. In addition, it also has a LysM-like domain that thus far has only been identified in two other LDT structures, YbiS from Gram-negative K. pneumoniae and YkuD from Gram-positive B. subtilis. This makes LdtAb unique from any other structurally characterized LDTs, as it is the only enzyme that has two different peptidoglycan-binding domains. Although the function of the LysM and PG domains in LdtAb is not confirmed, their structural similarity to known peptidoglycan-binding domains in various other, non-LDT enzymes indicates they are likely involved in anchoring the enzyme to the cell wall. Existence of the LysM and PG domains together in LdtAb could enhance the enzyme’s peptidoglycan binding ability, as has been demonstrated for other unrelated enzymes containing multiple LysM domains.51

In addition to the above-mentioned structures, the only other reported LDT structure from Gram-negative bacteria is that of YbiS from K. pneumoniae, another member of the Enterobacteriaceae family. The structure of the enzyme shows the presence of three domains, an N-terminal LysM domain, the conserved catalytic domain, and a C-terminal domain of unknown function (Supplementary Figure S2). This enzyme is almost identical with the E. coli YbiS protein, which is not involved in peptidoglycan cross-linking, but is important for attachment of Braun lipoprotein to peptidoglycan.14,15 A BLAST search of GenBank with the K. pneumoniae YbiS amino acid sequence also showed the presence of this smaller LDT in all Enterobacteriaceae but not in A. baumannii. As expected, a BLAST search also revealed presence in Klebsiella of the peptidoglycan cross-linking LDT YcbB.

CONCLUSIONS

Here we report characterization of LdtAb from the clinically important pathogen, A. baumannii, by evaluating the effect of its inactivation on bacterial growth, resistance to and kinetics of the interaction with β-lactam antibiotics, and by solving its X-ray crystal structure. Our study demonstrated that LdtAb has unique structural architecture and is very poorly inhibited in vitro by the carbapenems, antibiotics of last resort.

METHODS

Bacterial Strains.

E. coli DH10B and A. baumannii CIP 70.10 and its mutant derivatives were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) or Mueller–Hinton II (MH) medium or on LB agar plates. Kanamycin (30 and 50 μg/mL) was added to culture medium to maintain plasmids in A. baumannii and E. coli, respectively. LB medium was supplemented with 10% sucrose for counter selection against the plasmids during the procedure of generating the A. baumannii deletion mutant (ΔLdtAb).

DNA Methods.

The suicide vector pMo130 was used to generate the deletion mutant of the l,d-transpeptidase (ABCIP7010_2611) in the genome of A. baumannii CIP 70.10 (Supplementary Table S1). Plasmid isolation, PCR methods, cleaning of PCR products, preparation of electrocompetent cells, electroporation of vectors, and genomic DNA purification were performed using standard protocols as described earlier36 using New England Biolabs, Promega, Qiagen, and Bio-Rad products. Primers were synthesized by Eurofin Genomics (Supplementary Table S2), DNA sequences of all constructs were verified by Molecular Cloning Laboratories (MCLAB), and the whole genome sequencing and comparative genomic data analysis were performed by EzBiome.

Generation of the ΔLdtAb Deletion Mutant.

To delete the gene for the l,d-transpeptidase, LdtAb (ABCIP7010_2611), we followed the recently described protocol.36 Briefly, primers were designed to PCR amplify approximately 1000 bp of the upstream region (UR) and the downstream region (DR) of the gene (Supplementary Table S2). The UR and DR included the first 12 bp and the last 27 bp of the targeted gene, respectively. The PCR products were purified, ligated, and reamplified to introduce BamHI restriction sites at both ends. Following digestion with BamHI, the fragment was cloned into the BamHI site of the pMo130 plasmid, resulting in the gene knockout suicide vector pMT335FW. This vector was transformed into E. coli DH10B and isolated from kanamycin resistant colonies. To create the gene deletion, we followed the two-step homologous recombination protocol.39,52 Briefly, the suicide vector pMT335FW was electroporated into A. baumannii CIP 70.10, and transformants containing the chromosomally integrated vector were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with kanamycin. Presence of the integrated vector was subsequently confirmed by PCR. To facilitate elimination of integrated vector, the integrant was further passaged three times in 5 mL LB medium supplemented with 10% sucrose and plated on LB agar with 10% sucrose. Resulting colonies were replica plated on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin to identify kanamycin sensitive colonies, which were formed by cells where the integrated vector had been eliminated by homologous recombination. The presence of the deletion of the gene for LdtAb was confirmed by colony PCR and verified by DNA sequencing. We used the same protocol to create the LdtAb+penicillin-binding protein (PBP) double mutants by attempting to delete the gene for LdtAb in A. baumannii CIP 70.10 variants where the gene encoding the PBP2 transpeptidase was deleted (ΔPBP2), or the PBP1a or PBP1b transpeptidases were inactivated by substitution of the catalytic Ser by Ala in their active sites (PBP1a(S/A) and PBP1b(S/A) mutants).36 Whole genome sequencing of all mutants did not reveal any mutations in genes known to be involved in cell wall biosynthesis. Additional information is presented in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.

The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibiotics against A. baumannii CIP 70.10 and its mutant derivatives were measured using MH medium and the broth dilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations.53,54 All measurements were performed at least in triplicate.

Growth Curves.

Overnight cultures of A. baumannii CIP 70.10 and its mutant derivatives were diluted 1:100 in MH medium and grown until their optical density (OD600) reached 0.2. The cultures were further diluted (200-fold) in MH medium to a final volume of 5 mL. Bacterial growth was monitored by plating cells on LB agar plates at designated time points. Colony forming units (CFU) were counted after overnight incubation, and the CFU/mL values were plotted as a function of time using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Three independent experiments were performed to generate growth curves.

Protein Expression and Purification.

The LdtAb enzyme lacking the first 23 amino acid residues was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Briefly, bacteria were grown in 300 mL minimal media broth supplemented with 60 µg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C to an OD600 nm = 0.6, at which point protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and the temperature was reduced to 22 °C. Following additional incubation for 24 h, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation. The cells were resuspended in 20 mM HEPES, pH 8 and disrupted by sonication at 4 °C. Next, the solution was subjected to ultracentrifugation (32 000 RPM for 1 h) at 4 °C, and the supernatant was loaded onto a Q anion-exchange column (Bio-Rad). The LdtAb containing fractions of flow through were collected and loaded onto a High S cation-exchange column (Bio-Rad). The protein was eluted with a linear sodium chloride gradient (0–500 mM). Fractions containing LdtAb were combined, dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and stored at 4 °C. The concentration of the protein was calculated from the absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 49 390 M−1 cm−1. The purity of the protein was verified by SDS-PAGE.

Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) Experiments.

To monitor complex formation between LdtAb and μ-lactams, LC-MS experiments were performed. For acyl enzyme formation, the protein (2 μM) was incubated with an excess of μ-lactams (200 μM) in PBS (10 mM sodium phosphate, 1.8 mM potassium phosphate, 137 mM sodium chloride, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, pH 7.4) at 22 °C. At predetermined time points, aliquots were removed, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until LC-MS analysis. To determine whether deacylation occurred, first LdtAb (2 μM) was incubated with ertapenem (200 μM) in PBS for 18 h at 22 °C to allow for complex formation. At this point, an aliquot was removed and stored at −80 °C until LC-MS analysis to verify that no apo LdtAb remained. Subsequently, excess ertapenem was removed by passing the reaction through three successive Zeba-0.5 mL spin desalting columns (7 kDa molecular weight cutoff) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Next, the purified reaction was incubated for 20 h at 22 °C to allow for deacylation. For LC-MS analysis, the instrument was comprised of an ultrahigh pressure LC system coupled to a Bruker MicrOTOF-QII mass spectrometer utilizing Hystar 5.0 SR1 software. The electrospray ionization source was operated in the positive ion mode as follows: end plate offset voltage = −500 V, capillary voltage = 2000 V, and nitrogen as both a nebulizer (4 bar) and dry gas (8 L/min) at 180 °C. Mass spectra were collected from 400–3000 m/z. LC separations were performed using a Poroshell 300SB-C3 column (5 μm, 2.1 mm i.d. × 75 mm) at 40 °C with a 15 min program (90% A/10% B from 0 to 2 min, followed by a 10–90% B gradient from 2 to 13 min, and 90% A/10% B from 13 to 15 min, where A = 0.1% formic acid in water, B = 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) using a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. LC flow was diverted to the waste for the first 2 min of each run. The maximum entropy algorithm (Bruker Compass DataAnalysis 4.2 SR2) was used to deconvolute multiply charged LdtAb ions. Relative amounts of acyl-enzyme species were calculated from the MS peak heights of the deconvoluted spectra. To determine the acylation rate constant, k2, data collected in triplicate were fitted to eq 1,

| (1) |

where LdtA/Ldt∞ is the ratio of acylated LdtAb to total LdtAb or the percentage of acylated LdtAb at time t, and k2 is the observed first-order rate constant for acylation.

Protein Crystallization.

Initial crystallization trials with the A. baumannii l,d-transpeptidase were set down using the sitting drop method in Intelliplates (Art Robbins), with PEG/Ion screens I and II, Crystal screens I and II, the PEGRx HT screen, and the Grid screen Salt HT (Hampton Research), at 4 and 15 °C. Crystals were obtained under condition 23 from the PEG/Ion I screen (0.2 M ammonium formate containing 20% PEG 3350). Crystallization did not occur immediately, and crystals were only observed more than one year after the drops were set down. The LdtAb crystals were football-shaped plates, approximately 250 × 100 × 25 μm, belonging to the trigonal space group P3221 with unit cell dimensions a = b = 91.47 Å, c = 105.11 Å and diffracting to approximately 2.6 Å resolution. The crystals were flash cooled in crystallization buffer supplemented with 25% glycerol. Several crystals were also soaked in crystallization buffer augmented with varying concentrations of KI (1/2, 1/4, and 1/8 saturation) and 25% glycerol, and flash-cooled in liquid N2. All crystals were stored in cryovials and shipped to the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) for data collection.

Diffraction Data Collection and Structure Solution.

A complete data set comprising 650 images with a rotation angle of 0.2° was collected from a single LdtAb crystal on SSRL beamline BL12–2 using X-rays at 12658 eV (0.97946 Å) and a PILATUS 6 M PAD detector running in shutterless mode. The data were processed with XDS55 and scaled with AIMLESS56 from the CCP4 suite of programs.57 The Mathews coefficient,58 assuming one molecule in the asymmetric unit, was 3.0 Å3/Da (59% solvent content). Final data collection statistics are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data Collection Statisticsa

| LdtAb | Iodide-LdtAb | |

|---|---|---|

| resolution (Å) | 37.1–2.6 (2.72–2.60) | 38.0–3.2 (3.42–3.20) |

| reflections, observed/unique | 113592/16048 | 714128/9200 |

| R meas b | 11.1 (112.6) | 46.6 (284.0) |

| R pim b | 4.1 (42.0) | 5.2 (32.6) |

| I/σI | 10.3 (1.9) | 15.5 (3.4) |

| completeness (%) | 99.8 (98.8) | 99.6 (99.3) |

| CC1/2c | 0.999 (0.932) | 0.998 (0.961) |

| average multiplicity | 7.1 (7.0) | 77.6 (74.1) |

| Wilson B (Å2) | 67.0 | 103.0 |

| anomalous multiplicity | – | 41.6 (38.8) |

| CCanomd |

– | 0.494 |

| MSANe | – | 1.288 |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

Rmeas is the redundancy-independent merging R factor. Rpim is the precision-indicating merging R factor.62

Correlation between intensities from random half-sets of data.63

Correlation of ΔIanom from two random half-sets.64

Midslope of the anomalous normal probability plot. Values > 1 indicate significant anomalous signal.62

Data from a single KI-soaked LdtAb crystal were collected on SSRL beamline BL12–2, using a PILATUS 6 M PAD detector in shutterless mode, with an X-ray energy of 7000 eV (1.77114 Å). A total of 7200 images were collected using the inverse beam method, in wedges of 10°, such that the Bijvoet pairs are measured close in time and with a minimal difference in absorption. The data were processed using XDS and scaled with AIMLESS to give a final data set to 3.2 Å resolution. Analysis of the data suggested a strong anomalous signal to approximately 4 Å resolution. Final statistics are given in Table 2.

The LdtAb structure was solved by single wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) methods using the PHENIX suite of programs.59 The substructure identified by the HYSS routine comprised seven iodide atoms, and these were used to obtain initial phases for the protein in space group P3231, with an initial FOM of 0.27. Solvent flattening and density modification gave interpretable electron density with clear protein–solvent boundaries and a map skew 0.09. A total of 200 residues out of 373 were built into the experimentally phased and density-modified electron density maps, resulting in Rwork and Rfree values of 0.446 and 0.502, respectively. The structure was rebuilt using phenix.autobuild to give a model comprising 273 residues with an Rfree of 0.355. Interactive model building with COOT60 was used to check the autobuilt residues and add the others. Refinement was transferred to the 2.6 Å resolution data, and water molecules and sulfate ions were added at this stage. The final model contained 313 residues (Ala37–Glu393) with three missing loops (Ser73–Ala93, Ser316–Pro326, and Ser361–Ala364), and 45 water molecules, with a Rwork of 0.2178 and a Rfree of 0.2648. Final refinement statistics for the LdtAb structure are given in Table 3. Ramachandran statistics indicate that all but two of the residues lie in the allowed regions, as calculated using MOLPROBITY.61

Table 3.

Structure Refinement Statistics

| LdtAb | |

|---|---|

| PDB code | 8DA2 |

| resolution range (Å) | 37.1–2.6 |

| reflections used, total/free | 15854/820 |

| working R-factor/Rfreea | 0.2178/0.2648 |

| total atoms | |

| protein | 2461 |

| solvent | 45 |

| B factors | |

| protein (Å2) | 74.7 |

| solvent (Å2) | 66.1 |

| rms deviations | |

| bonds (Å) | 0.009 |

| angles (°) | 1.12 |

| Ramachandran plotb | |

| favored regions (%) | 96.2 |

| outliers | 1 |

| MOLPROBITY scoreb | 2.28 (91st percentile) |

| Clash scoreb | 9.36 (98th percentile) |

Rfree was calculated with 5% of the unique reflections

Calculated with MOLPROBITY.59

Determination of Homo-oligomer State with Native Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS).

The LdtAb protein was buffer exchanged into 1 M ammonium acetate, pH 6.5–7 using a Zeba spin desalting column (Thermo) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein concentration was measured using a NanoDrop, and aliquots of serially diluted samples (1.2–12.4 μM) were analyzed with native ESI-MS.

The mass spectra of LdtAb were acquired in the mass range 500–10 000 Da using a Bruker MicrOTOF-QII operating in the positive-ion mode with the following parameters: end plate offset −500 V, capillary voltage 3.6 kV, nebulizer gas pressure 1.8 bar, dry gas flow rate 3.5 L/min, dry gas temperature 180 °C, funnel 1 RF 400 V, funnel 2 RF 500 V, hexapole RF 600 V, quadrupole ion energy 3 eV, collision energy 5 eV, collision cell RF 3.4 kV, ion transfer time 110 μs, and repulse ion storage 30 μs. Solutions were infused at a flow rate of 3 μL/min. Mass spectra were collected for 3 min. Multiply charged ions were deconvoluted using the maximum entropy algorithm (Bruker Compass DataAnalysis 4.2).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Grant 1R01AI155723 from the NIH/NIAID to SBV. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy (BES, BER) and by the National Institutes of Health (NCRR, BTP, NIGMS). The project described was also supported by Grant Number 5 P41 RR001209 from the NCRR, a component of the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- NAG

N-acetylglucosamine

- NAM

N-acetylmuramic

- DDTs

d,d-transpeptidases

- LDTs

l,d-transpeptidases

- mDAP

meso-diaminopimelic acid

- PBPs

penicillin-binding proteins

- MICs

minimal inhibitory concentrations

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- rmsds

root-mean-square deviations

- SAD

single wavelength anomalous diffraction

- PG

peptidoglycan-binding

- LB

Luria–Bertani

- MH

Mueller–Hinton

- UR

upstream region

- DR

downstream region

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- OD

optical density

- IPTG

isopropyl-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- CFU

colony forming units

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00321.

Evidence for domain-swapping in the LdtAb crystals (Supplementary Methods); Bacterial strains and plasmid constructs used in this study (Table S1); Steps of allelic exchange procedure, primers, and sizes of PCR products to generate and verify the ΔLdtAb mutant derivatives of A. baumannii CIP 70.10 (Table S2); Representative structures of l,d-transpeptidases (Table S3); Native ESI-MS of LdtAb (Figure S1); Structures of selected known l,d-transpeptidases (Figure S2); Structure-based sequence alignment of the canonical catalytic domains for the Gram-negative and Gram-positive LDTs (Figure S3); Predicted structure of the LdtAb monomer (Figure S4); Evidence for domain-swapping in LdtAb (Figure S5) (PDF)

Accession Codes

The LdtAb structure factors and atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with PDB code 8DA2. The authors will release the atomic coordinates and experimental data upon article publication.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00321

Contributor Information

Marta Toth, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Nichole K. Stewart, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

Clyde A. Smith, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States; Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, Menlo Park, California 94025, United States

Mijoon Lee, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States; Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Sergei B. Vakulenko, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Vollmer W; Blanot D; de Pedro MA Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2008, 32, 149–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Cochrane SA; Lohans CT Breaking down the cell wall: Strategies for antibiotic discovery targeting bacterial transpeptidases. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2020, 194, 112262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Sauvage E; Kerff F; Terrak M; Ayala JA; Charlier P The penicillin-binding proteins: structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2008, 32, 234–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Glauner B; Holtje JV; Schwarz U The composition of the murein of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem 1988, 263, 10088–10095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Pisabarro AG; de Pedro MA; Vazquez D Structural modifications in the peptidoglycan of Escherichia coli associated with changes in the state of growth of the culture. J. Bacteriol. 1985, 161, 238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Blasco B; Pisabarro AG; de Pedro MA Peptidoglycan biosynthesis in stationary-phase cells of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol 1988, 170, 5224–5228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Peltier J; Courtin P; El Meouche I; Lemee L; Chapot-Chartier MP; Pons JL Clostridium difficile has an original peptidoglycan structure with a high level of N-acetylglucosamine deacetylation and mainly 3–3 cross-links. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 29053–29062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lavollay M; Arthur M; Fourgeaud M; Dubost L; Marie A; Veziris N; Blanot D; Gutmann L; Mainardi JL The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by L,D-transpeptidation. J. Bacteriol 2008, 190, 4360–4366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mainardi JL; Morel V; Fourgeaud M; Cremniter J; Blanot D; Legrand R; Frehel C; Arthur M; Van Heijenoort J; Gutmann L Balance between two transpeptidation mechanisms determines the expression of β-lactam resistance in Enterococcus faecium. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 35801–35807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Mainardi JL; Fourgeaud M; Hugonnet JE; Dubost L; Brouard JP; Ouazzani J; Rice LB; Gutmann L; Arthur M A novel peptidoglycan cross-linking enzyme for a β-lactam-resistant transpeptidation pathway. J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 38146–38152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cameron TA; Anderson-Furgeson J; Zupan JR; Zik JJ; Zambryski PC Peptidoglycan synthesis machinery in Agrobacterium tumefaciens during unipolar growth and cell division. mBio 2014, 5, No. e01219–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Aliashkevich A; Cava F,L,D-transpeptidases: the great unknown among the peptidoglycan cross-linkers. FEBS J. 2021, DOI: 10.1111/febs.16066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Biarrotte-Sorin S; Hugonnet JE; Delfosse V; Mainardi JL; Gutmann L; Arthur M; Mayer C Crystal structure of a novel β-lactam-insensitive peptidoglycan transpeptidase. J. Mol. Biol 2006, 359, 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Magnet S; Dubost L; Marie A; Arthur M; Gutmann L Identification of the L,D-transpeptidases for peptidoglycan cross-linking in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol 2008, 190, 4782–4785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Magnet S; Bellais S; Dubost L; Fourgeaud M; Mainardi JL; Petit-Frere S; Marie A; Mengin-Lecreulx D; Arthur M; Gutmann L Identification of the L,D-transpeptidases responsible for attachment of the Braun lipoprotein to Escherichia coli peptidoglycan. J. Bacteriol 2007, 189, 3927–3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Winkle M; Hernandez-Rocamora VM; Pullela K; Goodall ECA; Martorana AM; Gray J; Henderson IR; Polissi A; Vollmer W DpaA detaches Braun’s lipoprotein from peptidoglycan. mBio 2021, 12, No. e00836–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bahadur R; Chodisetti PK; Reddy M Cleavage of Braun’s lipoprotein Lpp from the bacterial peptidoglycan by a paralog of L,D-transpeptidases, LdtF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2021, 118, No. e2101989118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).More N; Martorana AM; Biboy J; Otten C; Winkle M; Serrano CKG; Monton Silva A; Atkinson L; Yau H; Breukink E; den Blaauwen T; Vollmer W; Polissi A Peptidoglycan remodeling enables Escherichia coli to survive severeouter membrane assembly defect. mBio 2019, 10, No. e02729–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cava F; de Pedro MA; Lam H; Davis BM; Waldor MK Distinct pathways for modification of the bacterial cell wall by noncanonical D-amino acids. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 3442–3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Erdemli SB; Gupta R; Bishai WR; Lamichhane G; Amzel LM; Bianchet MA Targeting the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: structure and mechanism of L,D-transpeptidase 2. Structure 2012, 20, 2103–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ahmad N; Dugad S; Chauhan V; Ahmed S; Sharma K; Kachhap S; Zaidi R; Bishai WR; Lamichhane G; Kumar P Allosteric cooperation in β-lactam binding to a non-classical transpeptidase. eLife 2022, 11, e73055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bielnicki J; Devedjiev Y; Derewenda U; Dauter Z; Joachimiak A; Derewenda ZSB subtilis ykuD protein at 2.0 A resolution: insights into the structure and function of a novel, ubiquitous family of bacterial enzymes. Proteins 2006, 62, 144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Caveney NA; Caballero G; Voedts H; Niciforovic A; Worrall LJ; Vuckovic M; Fonvielle M; Hugonnet JE; Arthur M; Strynadka NCJ Structural insight into YcbB-mediated β-lactam resistance in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Caveney NA; Serapio-Palacios A; Woodward SE; Bozorgmehr T; Caballero G; Vuckovic M; Deng W; Finlay BB; Strynadka NCJ Structural and cellular insights into the L,D-transpeptidase YcbB as a therapeutic target in Citrobacter rodentium, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Salmonella Typhi infections. Anti-microb. Agents Chemother 2021, DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01592-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Aurilio C; Sansone P; Barbarisi M; Pota V; Giaccari LG; Coppolino F; Barbarisi A; Passavanti MB; Pace MC Mechanisms of action of carbapenem resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hugonnet JE; Mengin-Lecreulx D; Monton A; den Blaauwen T; Carbonnelle E; Veckerle C; Brun YV; van Nieuwenhze M; Bouchier C; Tu K; Rice LB; Arthur M Factors essential for L,D-transpeptidase-mediated peptidoglycan cross-linking and β-lactam resistance in Escherichia coli. eLife 2016, e19469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kumar P; Kaushik A; Lloyd EP; Li SG; Mattoo R; Ammerman NC; Bell DT; Perryman AL; Zandi TA; Ekins S; Ginell SL; Townsend CA; Freundlich JS; Lamichhane G Non-classical transpeptidases yield insight into new antibacterials. Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Cordillot M; Dubee V; Triboulet S; Dubost L; Marie A; Hugonnet JE; Arthur M; Mainardi JL In vitro cross-linking of Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptidoglycan by L,D-transpeptidases and inactivation of these enzymes by carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 5940–5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Triboulet S; Arthur M; Mainardi JL; Veckerle C; Dubee V; Nguekam-Moumi A; Gutmann L; Rice LB; Hugonnet JE Inactivation kinetics of a new target of β-lactam antibiotics. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 22777–22784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Triboulet S; Dubee V; Lecoq L; Bougault C; Mainardi JL; Rice LB; Etheve-Quelquejeu M; Gutmann L; Marie A; Dubost L; Hugonnet JE; Simorre JP; Arthur M Kinetic features of L,D-transpeptidase inactivation critical for β-lactam antibacterial activity. PloS One 2013, 8, No. e67831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Shaku M; Ealand C; Matlhabe O; Lala R; Kana BD Peptidoglycan biosynthesis and remodeling revisited. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 112, 67–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Nguyen M; Joshi SG Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii, and their importance in hospital-acquired infections: a scientific review. J. Appl. Microbiol 2021, 131, 2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Wong D; Nielsen TB; Bonomo RA; Pantapalangkoor P; Luna B; Spellberg B Clinical and pathophysiological overview of Acinetobacter infections: a century of challenges. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2017, 30, 409–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Geisinger E; Mortman NJ; Dai Y; Cokol M; Syal S; Farinha A; Fisher DG; Tang AY; Lazinski DW; Wood S; Anthony J; van Opijnen T; Isberg RR Antibiotic susceptibility signatures identify potential antimicrobial targets in the Acinetobacter baumannii cell envelope. Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Kang KN; Kazi MI; Biboy J; Gray J; Bovermann H; Ausman J; Boutte CC; Vollmer W; Boll JM Septal class A penicillin-binding protein activity and L,D-transpeptidases mediate selection of colistin-resistant lipooligosaccharide-deficient Acinetobacter baumannii. mBio 2021, 12, No. e02185–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Toth M; Lee M; Stewart NK; Vakulenko SB Effects of inactivation of D,D-transpeptidases of Acinetobacter baumannii on bacterial growth and susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2022, 66, No. e0172921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Dai Y; Pinedo V; Tang AY; Cava F; Geisinger E A new class of cell wall-recycling L,D-carboxypeptidase determines β-lactam susceptibility and morphogenesis in Acinetobacter baumannii. mBio 2021, 12, No. e0278621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Krahn T; Wibberg D; Maus I; Winkler A; Puhler A; Poirel L; Schluter A Complete genome sequence of Acinetobacter baumannii CIP 70.10, a susceptible reference strain for comparative genome analyses. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, No. e00850–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Biswas I Genetic tools for manipulating Acinetobacter baumannii genome: an overview. J. Med. Microbiol 2015, 64, 657–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Gupta R; Al-Kharji N; Alqurafi MA; Nguyen TQ; Chai W; Quan P; Malhotra R; Simcox BS; Mortimer P; Brammer Basta LA; Rohde KH; Buynak JD Atypically modified carbapenem antibiotics display improved antimycobacterial activity in the absence of β-lactamase inhibitors. ACS Infect. Dis 2021, 7, 2425–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Zandi TA; Townsend CA Competing off-loading mechanisms of Meropenem from an L,D-transpeptidase reduce antibiotic effectiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2021, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2008610118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Chiou J; Cheng Q; Shum PT; Wong MH; Chan EW; Chen S Structural and functional characterization of OXA-48: insight into mechanism and structural basis of substrate recognition and specificity. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2021, 22, 11480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Papp-Wallace KM; Endimiani A; Taracila MA; Bonomo RA Carbapenems: past, present, and future. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 4943–4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Brammer Basta LA; Ghosh A; Pan Y; Jakoncic J; Lloyd EP; Townsend CA; Lamichhane G; Bianchet MA Loss of a functionally and structurally distinct L,D-transpeptidase, LdtMt5, compromises cell wall integrity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 25670–25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Correale S; Ruggiero A; Capparelli R; Pedone E; Berisio R Structures of free and inhibited forms of the L,D-transpeptidase LdtMtl from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 2013, 69, 1697–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Zhao F; Hou YJ; Zhang Y; Wang DC; Li DF The l-β-methyl group confers a lower affinity of L,D-transpeptidase LdtMt2 for ertapenem than for imipenem. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2019, 510, 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Bianchet MA; Pan YH; Basta LAB; Saavedra H; Lloyd EP; Kumar P; Mattoo R; Townsend CA; Lamichhane G Structural insight into the inactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis non-classical transpeptidase LdtMt2 by biapenem and tebipenem. BMC Biochem. 2017, 18, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Maciejewska B; Zrubek K; Espaillat A; Wisniewska M; Rembacz KP; Cava F; Dubin G; Drulis-Kawa Z Modular endolysin of Burkholderia AP3 phage has the largest lysozyme-like catalytic subunit discovered to date and no catalytic aspartate residue. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 14501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Joris B; Englebert S; Chu CP; Kariyama R; Daneo-Moore L; Shockman GD; Ghuysen JM Modular design of the Enterococcus hirae muramidase-2 and Streptococcus faecalis autolysin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 1992, 91, 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Buist G; Steen A; Kok J; Kuipers OP LysM, a widely distributed protein motif for binding to (peptido)glycans. Mol. Microbiol 2008, 68, 838–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Mesnage S; Dellarole M; Baxter NJ; Rouget JB; Dimitrov JD; Wang N; Fujimoto Y; Hounslow AM; Lacroix-Desmazes S; Fukase K; Foster SJ; Williamson MP Molecular basis for bacterial peptidoglycan recognition by LysM domains. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Amin IM; Richmond GE; Sen P; Koh TH; Piddock LJ; Chua KL A method for generating marker-less gene deletions in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).CLSI. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 11th ed.; CLSI Document M07-A11; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Stewart NK; Smith CA; Antunes NT; Toth M; Vakulenko SB Role of the hydrophobic bridge in the carbapenemase activity of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2019, 63, No. e02191–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Kabsch W XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Evans PR; Murshudov GN How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 2013, 69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Winn MD; Ballard CC; Cowtan KD; Dodson EJ; Emsley P; Evans PR; Keegan RM; Krissinel EB; Leslie AG; McCoy A; McNicholas SJ; Murshudov GN; Pannu NS; Potterton EA; Powell HR; Read RJ; Vagin A; Wilson KS Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 2011, 67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Matthews BW Solvent contents of protein crystals. J. Mol. Biol 1968, 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Adams PD; Afionine PV; Bunkoczi G; Chen VB; Davis IW; Echols N; Headd JJ; Hung LW; Kapral GJ; Grosse-Kunstleve RW; McCoy AJ; Moriarty NW; Oeffner R; Read RJ; Richardson DC; Richardson JS; Terwilliger TC; Zwart PH PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Emsley P; Lohkamp B; Scott WG; Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Chen VB; Arendall WB 3rd; Headd JJ; Keedy DA; Immormino RM; Kapral GJ; Murray LW; Richardson JS; Richardson DC MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Weiss MS Global indicators of X-ray data quality. J. Appl. Crystallogr 2001, 34, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Karplus PA; Diederichs K Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science 2012, 336, 1030–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Evans P Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 2006, 62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.