Abstract

Background:

Governments introduced emergency measures to address the shortage of homecare workers and unmet care needs in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective:

This article aims to describe how policies impacted home care and identifies the potential risks for clientele and staff.

Method: Experts in home care (n = 15) were interviewed about policies that affect health and safety for homecare recipients.

Results:

New recruitment strategies, condensed education and rapid hiring during the pandemic did not lead to the recruitment of sufficient workers, but increased the potential for recruitment of unsuitable workers or workers with little training.

Conclusion:

It is important to consider the unintended effects of emergency policy measures and to manage the effects of such policies on homecare clients.

Abstract

Contexte:

Les gouvernements ont mis en place des mesures d'urgence pour remédier à la pénurie de travailleurs à domicile et aux besoins non satisfaits en matière de soins au Canada pendant la pandémie de COVID-19.

Objectif:

Cet article vise à décrire l'impact des politiques sur les soins à domicile et à identifier les risques potentiels pour la clientèle et le personnel.

Méthode:

Des experts en soins à domicile (n = 15) ont été interrogés sur les politiques qui affectent la santé et la sécurité des bénéficiaires de soins à domicile.

Résultats:

De nouvelles stratégies de recrutement, une formation condensée et une embauche rapide pendant la pandémie n'ont pas conduit au recrutement d'un nombre suffisant de travailleurs, mais ont augmenté le potentiel de recrutement de travailleurs inadaptés ou peu formés.

Conclusion:

Il est important de tenir compte des effets imprévus des mesures politiques d'urgence et d'en gérer l'impact sur les clients des soins à domicile.

Introduction

More older Canadians are requiring more complex care at home as policies move care away from long-term care (LTC) homes and hospitals (Blay and Roche 2020; CIHI 2017; Johnson and Bacsu 2018). Worker shortages are endemic, and homecare workers are often employed part-time with inconsistent, non-guaranteed hours of work and low pay (Zagrodney and Saks 2017). The bulk of homecare services in Canada is provided by unregulated workers, who help community-dwelling clients with activities of daily living. While in this paper we use the term “personal support workers” (PSWs), they are also called by other titles, such as home support workers or home health aides (Sims-Gould et al. 2010). Homecare PSWs provide help with routine personal care activities, such as washing and bathing, and are also regularly assigned clinical tasks such as transferring clients using required equipment and assisting with medication (Denton et al. 2015; Saari et al. 2018; Zeytinoglu et al. 2014).

This paper examines the emergency policy measures related to PSW recruitment and education introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Taking the case of Ontario, we consider the unintended consequences of emergency policy measures in PSW-provided home care.

New Risks and Pandemic Policy in Ontario

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ontario government brought in a series of orders under the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act (1990) (Jeronimo 2020). These orders arose from the need to mitigate the spread of infection in the midst of a deadly crisis in LTC that accounted for 64.5% of all COVID-19 deaths in Ontario (Stall et al. 2021). They included Limiting Work to a Single Long-Term Care Home (O. Reg. 146/20) that required LTC workers to work at only one LTC home – or retirement home (O. Reg. 158/20) – to avoid spreading the virus. (These orders were in place from April 2020 to March 2022.) This contributed to a shuffling of the LTC workforce, including PSWs leaving the homecare sector for better paying and more secure jobs in LTC (Casey 2021). A separate order – Deployment of Employees of Service Provider Organizations (O. Reg. 156/20) – allowed for the redeployment of workers from home care and other community settings to LTC (Jeronimo 2020), although both sectors were insufficiently resourced.

Homecare Recruitment and Retention

There is international concern about the shortage of healthcare human resources, with increasing older populations and high turnover among workers contributing to a demand–supply imbalance (Gruber et al. 2021; Quinn et al. 2021; Strandell 2020). Turnover issues have existed for well over a decade in the Canadian homecare sector (Sayin et al. 2019; Zeytinoglu et al. 2009). In 2014, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care reported that an estimated 60% of homecare PSWs leave their job each year (Matthews 2014).

Homecare workers are not regulated professionals in many countries, such as the UK (Saks and Allsop 2020), Sweden, Belgium, the US (Saari et al. 2018) and Canada (Afzal et al. 2018). In a context of inconsistent standards, the unclear competency of homecare workers can adversely impact client safety (Barken et al. 2020; Craven et al. 2012; Lang et al. 2014; Quinn et al. 2021; Tong et al. 2016).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for PSWs in Canada was ever more pressing as the demand for home care exceeded worker availability (Casey 2021).While demand for home care dropped as much as 16% in March and April 2020, it returned to historic levels by September 2020 (Jones et al. 2021). However, PSW supply lagged. For instance, Ontario's ability to meet homecare service requests fell from 95% pre-pandemic to 60% as of October 2021 (Casey 2021) because of PSW and nurse shortages (Rodriguez 2020; Weeks et al. 2021).

Insecure work hours and low pay are widely thought to contribute to poor retention, and workers experience high rates of workplace injury, stress, burnout and turnover (Barken et al. 2018; Sayin et al. 2019; Zeytinoglu and Denton 2006; Zeytinoglu et al. 2009, 2015).

Wages

In 2014, the provincial Ontario government implemented a gradual wage increase for PSWs (Lysyk 2015). However, a recent study found that the wage increase had no discernible effect on retention (Olaizola et al. 2020).

In this paper, we highlight the ripple effects of policy developments during the COVID-19 pandemic and identify potential risks for PSW-provided homecare clients using the case of Ontario. Analysis was guided by a client-risk lens as used by the UK Professional Standards Authority (Professional Standards Authority 2016) and Saks and Allsop (2020), who described the risks in light of inadequate training, supervision and low standards of care in the UK.

Method

We drew on interpretive policy analysis to explore data, which involves a focus on local knowledge, including an in-depth understanding of the actors and circumstances surrounding policy and the practical consequences of policies (Yanow 2000). This method is appropriate for exploring standpoints of multiple actors, their situated perspectives of policy related to PSWs and the implications for client risk. Ethics approval for this study was provided by the University of Waterloo Research Ethics Board and included informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality.

Recruitment and Sample

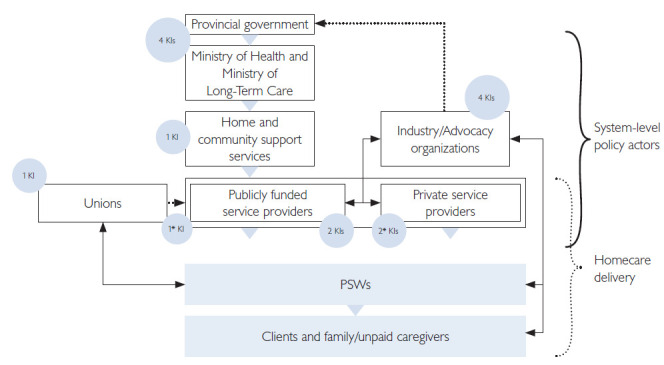

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted by PH (a former homecare PSW) from September 2020 to January 2021 and coincided with Ontario's second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews were conducted with key informants (KIs). KIs were required to have close and current knowledge of homecare policy, the PSW occupation and/or client safety. KIs were identified by mapping the homecare system-level policy making through to service delivery policy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

KIs within the homecare system: A policy actor map

* One Union KI and one private service provider KI were also PSWs.

KI = key informant; PSW = personal support worker.

To ensure that KIs were included from each part of the homecare system, we aimed for four participants from each of the following categories: the government, industry/advocacy organizations, service provider organizations (SPOs) and four other “policy actors” based on needs identified (Yanow 2007). We had difficulty recruiting KIs from two sections of our target sample: we had zero response for the home and community care support services (HCCSS) organizations; however, these organizations were undergoing administrative transitions while also dealing with COVID-19 infections among clients and staff. We requested snowball referrals from KIs and personal contacts, and one individual was recruited by these means. For SPOs, we were unable to recruit four KIs who had experience providing publicly funded home care and expanded our recruitment to include two private service providers that employed PSWs. We used government organizational directories, submissions to governments, organizational reports and lists of homecare service providers to identify potential KIs. While PSW experience was not part of the sample inclusion criteria as the study focused on policy, two KIs who had PSW experience added depth to our sample. One KI who was also a PSW was found as a union representative with public contact information and one was found via a publicly advertised company providing homecare services. Overall, this sampling strategy allowed for purposeful selection of well-positioned individuals from organizations and the government. Individuals were contacted by phone and, in some instances, by e-mail. If a response was not received within two weeks, we followed up with an additional contact. Fifteen KIs were included in this study.

Data Gathering and Analysis

Prior to and alongside interviews, PH examined applicable laws and government documents in keeping with the importance of local knowledge in interpretive policy analysis (Yanow 2000). This process enhanced our ability to ask specific questions of participants and deepened our understanding of their responses. Refer to Hopwood (2021) for more details on the policy analysis process.

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted via video calls or by telephone. The interview guide was based on previous policies and literature on the study topic (Yanow 2000), as well as co-authors' expertise in this area. Interview questions focused on KIs' perspectives of policies that increased risks for clients in PSW-provided care. (See Appendix 1, available online at here). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Memos and detailed field notes were also used to inform interpretations (Yanow 2007). Transcripts were uploaded to the NVivo-12 software (2018 version) and coded using an inductive coding process (Braun and Clarke 2006). Coding was conducted by PH, reviewed by EM and discussed with the remaining authors. In-depth analysis and team discussion of themes followed the coding process (Silverman 2015). Following Seale (2003), we used a triangulation of methods (policy analysis and interviews) and analysts (authors with different disciplinary backgrounds).

Study Findings

The 15 KIs provided senior-level insight from their positions in government departments, as senior managers in province-wide industry and advocacy organizations and as union experts. The KIs were from both provincial (n = 9) and regional (n = 6) organizations. One-quarter of the KIs had nursing backgrounds, thus also contributing clinical perspectives, while two were also PSWs. Four had 2–10 years of experience, and 11 had more than 10 years of experience (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key informants

| Participant number | Organization* | Position/role* | Scope of knowledge | Experience in years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Government ministry | Senior government manager or official | Provincial | 11–15 |

| P2 | Government ministry | Senior government manager or official | Provincial | >25 |

| P3 | Government ministry | Senior government manager or official | Provincial | 2–5 |

| P4 | Government ministry | Policy researcher, consultant or program officer | Provincial | 6–10 |

| P5 | SPO | Senior manager | Region¶ A | >25 |

| P6 | SPO | Senior manager | Region¶ A | 2–5 |

| P7 | SPO | Senior manager | Region¶ B | >25 |

| P8 | SPO | PSW, entrepreneur | Region¶ A | 2–5 |

| P9 | Provincial health advocacy/industry organization | Senior manager | Provincial | >25 |

| P10 | Provincial health advocacy/industry organization | Senior manager | Provincial | >25 |

| P11 | Provincial health advocacy/industry organization | Senior manager | Provincial | 16–25 |

| P12 | Provincial health advocacy/industry organization | Senior manager | Provincial | 16–25 |

| P13 | HCSS§ | Care coordinator | Region¶ C | 11–15 |

| P14 | SPO | PSW, union representative | Region¶ D | 16–25 |

| P15 | Union | Occupational health and safety | Provincial | 11–15 |

HCCSS = Home and Community Care Support Services; PSW = personal support worker; SPO = service provider organization.

Broad categories are used to describe organizations and roles to protect participant identity.

HCCSS since April 2021 (formerly Local Health Integration Networks [LHINs], 2017–2021).

Regions: One of the Ontario Health Regions (North, West, Central, East and Toronto); location has not been provided to protect participant identity.

We discuss findings in three main areas: (1) shortages; (2) recruitment strategies: rapid education and hiring; and (3) recruitment and retention: wages.

Shortages

Many KIs commented on worker shortages as common and increasingly problematic across health sectors during the COVID-19 pandemic. A senior government manager identified the urgent need for homecare staff, saying “We just need people. We need people. We're desperate for people.” (P1)

A senior manager of a provincial health advocacy/industry organization noted a drop in the number of homecare staff provincially:

Overall, during the height of wave one, [the homecare sector] probably lost a good 20–30% of … staff. Not only just to better paying jobs, but to government subsidies. (P9)

Several KIs linked shortages to PSW job conditions. For example, a senior government manager spoke about how improved job conditions would probably be needed to help address PSW shortages. An HCCSS care coordinator summarized the overall environment in Ontario as a dire staffing situation and noted that varying client demands made homecare staffing challenging. As clients were moved from hospitals to LTC to create hospital space during the pandemic, the number of homecare clients waiting for LTC grew from almost 35,000 before the pandemic to more than 39,000 as of January 2021 (Stall et al. 2021). Detailed quotations regarding PSW shortages are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Challenges regarding personal support worker shortages

| KI | Role | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| P5 | Senior manager, SPO | “… multiple PSWs have multiple jobs. [T]hen [the] next thing you know, they're calling and cancelling their shifts because, maybe, the shifts that we had for them that they originally accepted might have been those shorter ones. But the other company now offered them those longer ones. So now they're cancelling on us and leaving the team to scramble to fill.” |

| P6 | Senior manager, SPO | “It doesn't matter if we had full-time hours to give them, but we were, you know, like a dollar shorter. You know, chances are they were going to go with another company or someone that was hiring them at an inflated price because a lot of companies were doing that.” |

| P15 | Occupational health and safety specialist, Union | “And the other thing we hear a lot from workers is that agencies are taking on patients and clients that they don't have the capacity to service, but they're taking them … just to get the funds attached.” |

| P13 | Care coordinator, HCCSS* | “So, trying to find a PSW is tough because a lot of the crunch right now for long-term-care facilities is [due to] crisis [at the] hospital because they're trying to clear out hospitals … I don't even know if we can [find] staff [for] high service needs [clients] in the [municipal] area, to be honest. |

| P1 | Senior manager, government ministry | “ … we're going to need to have better conditions … . Otherwise, we're just going to not have the people. And talking about increasing investment in home care is one thing, but to do it without putting money into the PSW side is going to be a real challenge because how do you keep up? I know some LHINs [HCCSS*] are [saying], ‘we can't spend the money you give us because we cannot find people to deliver it … .’" |

| P1 | Senior manager, SPO | “We've got shortages right now for sure. And it's something that we've grappled with for a number of years.” |

HCCSS = Home and Community Care Support Services; KI = key informant; LHIN = Local Health Integration Network; PSW = personal support worker; SPO = service provider organization.

HCCSS since April 2021 (formerly LHINs, 2017–2021).

Recruitment Strategies: Rapid Education and Hiring

KIs discussed how shortages escalated during the pandemic and drove the development of provincial policies focused on rapid recruitment, education and hiring. They described free and subsidized education for aspiring PSWs and “return of service” bonuses of $5,000 for newly graduated PSWs who completed six months' work for employers enrolled in the program (HealthForceOntario 2022). KIs also discussed SPOs offering wages above the usual minimum standards.

A KI with a senior government position in the Ministry of Health described that the lack of an adequate supply of PSWs to provide care created the potential for quality of care to be sacrificed and quick hiring to be prioritized: “The fact that some care is better than no care, I think, maybe, has driven a lot of the decision making” (P3, senior government role). Another senior government KI spoke about shortages and implications of orders to limit work to a single LTC or retirement home:

The health human resource[s] shortages are being exacerbated during the pandemic … People have multiple jobs. This [home care] may [just] have not been the one they decided to stick with. They were told to stay in one location, and if they have a long-term care gig, they were going to stay there. (P1)

Widespread labour shortages were seen as having implications for client risk as the high staffing need led to poor staff screening. This interplay between shortages and the hiring process was described by a senior manager in a provincial health advocacy/industry organization:

… There is such a shortage that even if a worker was to lose their job for poor practice, they would just get a job somewhere else immediately. (P10)

A senior government manager suggested that rapid hiring may contribute to the recruitment of unsuitable workers:

… I think that happens with PSWs … You keep getting hired and moved on because the shortage means that people aren't, maybe, taking the time to do all the background checking or perhaps it's kind of out of sight, out of mind … (P3)

Ontario's tuition-free college education was seen as creating a risk of drawing in people who were unsuited to PSW work. For instance, a homecare business owner and PSW saw free education as a magnet for “anybody” irrespective of their suitability for the job: "That attracted so many wrong people to our profession. Being a PSW, you can't just be anybody. You need to be caring. You need to be compassionate" (P8).

Recruitment and Retention: Wages

During the pandemic, policy to support recruitment and retention of PSWs included funding temporary wage increases for SPO workers; however, disparity between LTC and homecare wages remained (Ireton 2021). A senior manager in an SPO discussed how worker shortages led to an increased competition with higher paying sectors: “We [are] constantly needing individuals. It's difficult when you're competing with the long-term care homes and retirement homes” (P6). Low wage-related issues created competition, not just between LTC and homecare sectors but also among homecare service providers. Within home care, SPOs seeking to hire new workers led some organizations to offer wages above the minimum standards. Some SPO managers saw this wage increase as amplifying competition for hiring PSWs.

Discussion

This study explored how policies introduced to address PSW shortages during the pandemic may affect client safety in the home care provided by PSWs. Drawing on interpretive policy analysis and by using the case of Ontario, we focused on shortages and impacts observed by well-placed KIs in the system. Combined with the existing evidence regarding quality of care for clients, this allowed us to consider potential policy improvements. Despite KIs' heterogenous backgrounds and positions, there was surprising agreement on key policy issues, such as the need for effective strategies to attract and retain more workers well-suited to the job and the importance of adequate education.

Consequences of Shortages and Recruitment Strategies

Healthcare workforce shortages have been problematic across sectors and international jurisdictions during the pandemic (Frogner et al. 2022; Gruber et al. 2021). International literature shows that workers faced challenges of increased workload due to absent co-workers, while limited access to personal protective equipment and risk of infection were additional concerns (Bandini et al. 2021; Markkanen et al. 2021).

We found that increased worker shortages made it challenging for SPOs to find enough PSWs to cover client care needs. Consequences of insufficient workers have been shown to include clients not receiving care and a revolving door of new workers unfamiliar with clients – with increased risk for clients' health and safety and elevated caregiver distress (Gamble 2021; Pfeffer 2020). Staff shortages also place existing workers under additional pressure, raising concern about occupational health and burnout (Agrba 2021). Lack of staffing for the provision of appropriate care has also been found to contribute to workers' moral distress (Webber et al. 2022), which, in turn, may further impact job satisfaction and retention (Panagiotoglou et al. 2017). Government managers acknowledged that providing services or spending existing care dollars was not feasible without adequate workers, despite a need for care. Our study emphasized that policies and health workforce recruitment strategies implemented during the pandemic failed to attract and retain sufficient workers.

Our study uncovered that pandemic-era policies that introduced rapid education programs had the effect of exacerbating SPO (employer) and other HCCSS stakeholders' pre-existing concerns about inconsistent education (Kelly 2017; Kelly and Bourgeault 2015). Although a minimum education standard was implemented in 2014 in Ontario by the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities (Kelly 2017; Kelly and Bourgeault 2015), this education is not required under provincial policy for Ontario homecare workers (Brookman et al. 2022). To ensure a high-quality workforce, mandatory education from approved programs should be considered. For example, British Columbia evaluates each program and requires that all publicly funded healthcare aides graduate from one of the approved schools (BC Care Aide and Community Health Worker Registry 2013).

Ontario's decision to limit workers to a single site was a good infection prevention and control measure: multi-site work has been identified as problematic in the US, for example (Baughman et al. 2022). Research comparing different jurisdictions' policy responses to managing worker shortages is needed. The Ontario Health agency has broad authority to set contract conditions following restructuring under the Connecting People to Home and Community Care Act (2020). To further reduce risk of infection spread and distribute the limited workforce more efficiently, this government agency could implement province-wide workforce policy and fund permanent, full-time PSW jobs. This could improve worker consistency and reduce multi-site work and the risk of infection transmission. Ensuring that jobs offer more consistent – for example, full-time – hours may also improve worker satisfaction and, in combination with wage parity, reduce attrition.

Wages: a Barrier to Hiring

Previous wage enhancements in Ontario did not make a marked difference in the supply and retention of PSWs (Olaizola et al. 2020). Our study reinforces the point that historic increases and pandemic wage enhancement alone have had insufficient lasting effect on the homecare workforce supply. Wages and intersectoral competition were viewed as a barrier to hiring and retaining homecare PSWs. Permanent wage enhancement, with home care on par with LTC, higher wages for increased skills and opportunity for advancement may be helpful policy levers for PSW staffing across Canada (Pan-Canadian Planning Committee on Unregulated Health Workers 2009) and in international jurisdictions facing similar issues.

Strengths and Limitations

Our analysis is novel in exploring how the COVID-19 pandemic policy measures to address workforce shortages impacted home care while describing potential implications for client risk. A limitation of our research is that our results do not represent all Ontario regions or provide urban–rural comparison, although six KIs had varying knowledge and roles in four different provincial regions, and the other nine participants provided insights from a provincial level.

Our study was focused on policy. We achieved a knowledgeable sample including perspectives from senior-level KIs in the government, provider and healthcare advocacy and industry organizations. A limitation of this study is that we did not include more PSWs as KIs.

Implications for Future Policy Research

More research highlighting jurisdictions with promising practices should be considered. Future research could also investigate the expense of wage increases compared to turnover expenses, such as hiring and training 60% of the workforce every year. Including primary research with local PSWs, managers and families and considering how client care may be impacted by PSW shortages could also be examined in future work.

It will be important to learn if the recruitment schemes did impact recruitment and retention; thus, future work may consider whether workers who received the bonuses stay in the profession and in the sector. Examination of system-level data to evaluate any measurable changes to client risk during the pandemic also merits consideration.

Conclusion

In this paper, we focused on how Ontario's pandemic policy affected PSW-provided home care. By focusing on senior-level KIs' input on impacts of policy for the homecare sector, our findings contribute to identification of how the pandemic escalated key issues of concern – namely, PSW shortage, the development of more rapid education programs, accelerated recruitment and hiring and wages. Policies to recruit PSWs, reduce the length of education and subsidize tuition – while providing only temporary wage increases to existing PSWs – illustrates a short-term, “fire-dousing” approach that failed to address retention and contributed to hiring PSWs not well suited to the role. Permanent wage enhancement on par with LTC, full-time secure employment, advancement opportunity and consistent education are policy measures that may contribute to a sustainable, high-quality PSW workforce.

Acknowledgment

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Katherine Lippel (LLL, LLM, FRSC), who was an advisor during the early stages of this research. Pamela Hopwood was supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Contributor Information

Pamela Hopwood, PhD Candidate, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON.

Ellen MacEachen, Professor, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON.

Carrie McAIney, Associate Professor, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo; Schlegel Research Chair in Dementia, Schlegel-University of Waterloo Research Institute for Aging, Waterloo, ON.

Catherine Tong, Adjunct Professor, Research Scientist, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON.

References

- Afzal A., Stolee P., Heckman G.A., Boscart V.M., Sanyal C. 2018. The Role of Unregulated Care Providers in Canada—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Older People Nursing 13(3): e12190. doi:10.1111/opn.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrba L. 2021, September 16. The Push to Fill Canada's Critical PSW Shortage. Maclean's. Retrieved June 9, 2022. <https://www.macleans.ca/society/health/the-push-to-fill-canadas-critical-psw-shortage/>.

- Bandini J., Rollison J., Feistel K., Whitaker L., Bialas A., Etchegaray J. 2021. Home Care Aide Safety Concerns and Job Challenges during the COVID-19 Pandemic. NEW Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 31(1): 20–29. doi:10.1177/1048291120987845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barken R., Denton M., Brookman C., Davies S., Zeytinoglu I.U. 2020. Community-Based Personal Support Workers' Responses to Health and Safety Risks: Tensions between Individual and Collective Responsibility. International Journal of Care and Caring 4(4): 459–78. doi:10.1332/239788220X15929332017232. [Google Scholar]

- Barken R., Denton M., Sayin F.K., Brookman C., Davies S., Zeytinoglu I.U. 2018. The Influence of Autonomy on Personal Support Workers' Job Satisfaction, Capacity to Care, and Intention to Stay. Home Health Care Services Quarterly 37(4): 294–312. doi:10.1080/01621424.2018.1493014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman R.A., Stanley B., Smith K.E. 2022. Second Job Holding among Direct Care Workers and Nurses: Implications for COVID-19 Transmission in Long-Term Care. Medical Care Research and Review 79(1): 151–60. doi:10.1177/1077558720974129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BC Care Aide and Community Health Worker Registry. 2013. Recognized BC Health Care Assistant Programs. Retrieved February 6, 2022. <https://www.cachwr.bc.ca/About-the-Registry/List-of-HCA-programs-in-BC.aspx>.

- Blay N., Roche M.A. 2020. A Systematic Review of Activities Undertaken by the Unregulated Nursing Assistant. Journal of Advanced Nursing 76(7): 1538–51. doi:10.1111/jan.14354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [Google Scholar]

- Brookman C., Sayin F., Denton M., Davies S., Zeytinoglu I. 2022. Community-Based Personal Support Workers' Satisfaction with Job-Related Training at the Organization in Ontario, Canada: Implications for Future Training. Health Science Reports 5(1): e478. doi:10.1002/hsr2.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). 2017. Seniors in Transition: Exploring Pathways across the Care Continuum. Retrieved February 6, 2022. <https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/seniors-in-transition-report-2017-en.pdf>.

- Casey L. 2021, October 31. ‘A Crisis for Home Care’: Droves of Workers Leave for Hospitals, Nursing Homes. Toronto Star. Retrieved December 1, 2021. <https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2021/10/31/a-crisis-for-home-care-droves-of-workers-leave-for-hospitals-nursing-homes.html>.

- Connecting People to Home and Community Care Act, 2020, S.O. 2020, c. 13 – Bill 175. Government of Ontario. Retrieved October 17, 2022. <https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/s20013>. [Google Scholar]

- Craven C., Byrne K., Sims-Gould J., Martin-Matthews A. 2012. Types and Patterns of Safety Concerns in Home Care: Staff Perspectives. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 24(5): 525–31. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzs047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton M., Brookman C., Zeytinoglu I., Plenderleith J., Barken R. 2015. Task Shifting in the Provision of Home and Social Care in Ontario, Canada: Implications for Quality of Care. Health and Social Care in the Community 23(5): 485–92. doi:10.1111/hsc.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E.9. Government of Ontario. Retrieved October 17, 2022. <https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90e09>. [Google Scholar]

- Frogner B. K., Dill J.S. 2022. Tracking Turnover among Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Health Forum 3(4): e220371. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble S. 2021, December 3. Unreliable Home Care: ‘Healthcare's Other Dirty Secret’. Brantford Expositor. Retrieved February 6, 2022. <https://www.brantfordexpositor.ca/news/unreliable-home-care-healthcares-other-dirty-secret>.

- Gruber E.M., Zeiser S., Schröder D., Büscher A. 2021. Workforce Issues in Home- and Community-Based Long-Term Care in Germany. Health and Social Care in the Community 29(3): 746–55. doi:10.1111/hsc.13324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthForceOntario. 2022, February 2. Personal Support Worker Return of Service (PSW ROS) 2021–22. Retrieved October 19, 2022. <https://www.healthforceontario.ca/en/Home/All_Programs/PSW_Return_of_Service>.

- Hopwood P. 2021. A Critical Examination of How Ontario's Home Care System Policy Affects PSW-Provided Home Care and Client Risk [Thesis]. University of Waterloo. Retrieved June 9, 2022. <https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/17353/Hopwood_Pamela..pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y>.

- Ireton J. 2021, March 18. Home-Care Workers Say Low Wages Are Driving Them Out of the Sector. CBC News. Retrieved December 8, 2021. <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/home-care-workers-poorly-paid-shortage-gender-race-issue-1.5953597>.

- Jeronimo S.N. 2020, April 1. The Orders Made Under the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act in Light of COVID-19 – What Are They? Hicks Morley. Retrieved December 1, 2021. <https://hicksmorley.com/2020/04/01/what-are-the-orders-made-under-the-emergency-management-and-civil-protection-act/>. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S., Bacsu J. 2018. Understanding Complex Care for Older Adults within Canadian Home Care: A Systematic Literature Review. Home Health Care Services Quarterly 37(3): 232–46. doi:10.1080/01621424.2018.1456996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A., MacLagan L.C., Schumacher C., Wang X., Jaakkimainen R.L., Guan J. et al. 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Home Care Services among Community-Dwelling Adults with Dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 22(11): 2258–62.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2021.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C. 2017. Exploring Experiences of Personal Support Worker Education in Ontario, Canada. Health and Social Care in the Community 25(4): 1430–38. doi:10.1111/hsc.12443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C., Bourgeault I.L. 2015. The Personal Support Worker Program Standard in Ontario: An Alternative to Self-Regulation? Healthcare Policy 11(2): 20–26. doi:10.12927/hcpol.2016.24450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A., MacDonald M.T., Storch J., Stevenson L., Mitchell L., Barber T. et al. 2014. Researching Triads in Home Care: Perceptions of Safety from Home Care Clients, Their Caregivers, and Providers. Home Health Care Management and Practice 26(2): 59–71. doi:10.1177/1084822313501077. [Google Scholar]

- Lysyk B. 2015. Special Report: Community Care Access Centres—Financial Operations and Service Delivery. Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Retrieved December 1, 2021. <https://www.homecareontario.ca/docs/default-source/publications-mo/ccacs_en.pdf?sfvrsn=2>.

- Markkanen P., Brouillette N., Quinn M., Galligan C., Sama S., Lindberg J. et al. 2021. “It Changed Everything”: The Safe Home Care Qualitative Study of the COVID-19 Pandemic's Impact on Home Care Aides, Clients, and Managers. BMC Health Services Research 21(1): 1055. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-07076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews D. 2014, January 27. Making Healthy Change Happen: Ontario's Action Plan for Health Care – Year Two Progress Report. Speeches. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. Retrieved December 1, 2021. <http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/news/speech/2014/sp_20140127.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- O. Reg. 146/20: LIMITING WORK TO A SINGLE LONG-TERM CARE HOME under Reopening Ontario (A Flexible Response to COVID-19) Act, 2020, S.O. 2020, c. 17. Retrieved October 17, 2022. <https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/200146>.

- O. Reg. 156/20: ORDER UNDER SUBSECTION 7.0.2 (4) OF THE ACT – DEPLOYMENT OF EMPLOYEES OF SERVICE PROVIDER ORGANIZATIONS filed April 16, 2020 under Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E.9. Retrieved October 17, 2022. <https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/r20156>.

- O. Reg. 158/20: LIMITING WORK TO A SINGLE RETIREMENT HOME under Reopening Ontario (A Flexible Response to COVID-19) Act, 2020, S.O. 2020, c. 17. Retrieved October 17, 2022. <https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/200158>.

- Olaizola A., Loertscher O., Sweetman A. 2020. Exploring the Results of the Ontario Home Care Minimum Wage Change. Healthcare Policy 16(1): 95–110. doi:10.12927/hcpol.2020.26288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan-Canadian Planning Committee on Unregulated Health Workers. 2009. Maximizing Health Human Resources: Valuing Unregulated Health Workers: Highlights of the 2009 Pan-Canadian Symposium. Canadian Nurses Association. Retrieved February 23, 2022. <https://cdnhomecare.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/UHW_Final_Report_e.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotoglou D., Fancey P., Keefe J., Martin-Matthews A. 2017. Job Satisfaction: Insights from Home Support Care Workers in Three Canadian Jurisdictions. Canadian Journal on Aging 36(1): 1–14. doi:10.1017/S0714980816000726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer A. 2020, December 6. Critical Shortage of Workers Hampering Home Care in Ottawa. CBC News. Retrieved December 1, 2021. <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ottawa-staffing-homecare-shortages-1.5828311>.

- Professional Standards Authority. 2016, January. Program Review of the Ontario Personal Support Worker Registry: Final Report. Retrieved January 1, 2021. <https://www.professionalstandards.org.uk/docs/default-source/publications/161212-psw-review-final-report.pdf?sfvrsn=ae607120_0>.

- Quinn M.M., Markkanen P.K., Galligan C.J., Sama S.R., Lindberg J.E., Edwards M.F. 2021. Healthy Aging Requires a Healthy Home Care Workforce: the Occupational Safety and Health of Home Care Aides. Current Environmental Health Reports 8(3): 235–44. doi:10.1007/s40572-021-00315-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S. 2020, October 30. Lack of PSWs Leaves London, Ont., Man Stuck in His Wheelchair for 3 Days. CBC News. Retrieved October 30, 2021. <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/psw-shortage-george-white-1.5781127>.

- Saari M., Patterson E., Kelly S., Tourangeau A.E. 2018. The Evolving Role of the Personal Support Worker in Home Care in Ontario, Canada. Health and Social Care in the Community 26(2): 240–49. doi:10.1111/hsc.12514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saari M., Xiao S., Rowe A., Patterson E., Killackey T., Raffaghello J. et al. 2018. The Role of Unregulated Care Providers in Home Care: A Scoping Review. Journal of Nursing Management 26(7): 782–94. doi:10.1111/jonm.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks M., Allsop J. 2020. Regulation, Risk and Health Support Work. In Saks M. ed., Support Workers and the Health Professions in International Perspective: The Invisible Providers of Health Care (1st ed.) (pp. 79–100). Bristol University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sayin F.K., Denton M., Brookman C., Davies S., Chowhan J., Zeytinoglu I.U. 2019. The Role of Work Intensification in Intention to Stay: A Study of Personal Support Workers in Home and Community Care in Ontario, Canada. Economic and Industrial Democracy 42(4): 917–36. doi:10.1177/0143831x18818325. [Google Scholar]

- Seale C. 2003. Quality in Qualitative Research. In Lincoln Y.S., Denzin N.K., eds., Turning Points in Qualitative Research: Tying Knots in a Handkerchief (pp. 169–84). AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D. 2015. Interpreting Qualitative Data. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Gould J., Byrne K., Craven C., Martin-Matthews A., Keefe J. 2010. Why I Became a Home Support Worker: Recruitment in the Home Health Sector. Home Health Care Services Quarterly 29(4): 171–94. doi:10.1080/01621424.2010.534047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall N.M., Brown K.A., Maltsev A., Jones A., Costa A.P., Allen V. et al. 2021. COVID-19 and Ontario's Long-Term Care Homes. Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table 2(7): 1–34. doi:10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.07.1.0. [Google Scholar]

- Strandell R. 2020. Care Workers Under Pressure – A Comparison of the Work Situation in Swedish Home Care 2005 and 2015. Health and Social Care in the Community 28(1): 137–47. doi:10.1111/hsc.12848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong C.E., Sims-Gould J., Martin-Matthews A. 2016. Types and Patterns of Safety Concerns in Home Care: Client and Family Caregiver Perspectives. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 28(2): 214–20. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber J., Trothen T.J., Finlayson M., Norman K.E. 2022. Moral Distress Experienced by Community Service Providers of Home Health and Social Care in Ontario, Canada. Health and Social Care in the Community 30(5): e1662–670. doi:10.1111/hsc.13592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks L.E., Nesto S., Hiebert B., Warner G., Luciano W., Ledoux K. et al. 2021. Health Service Experiences and Preferences of Frail Home Care Clients and Their Family and Friend Caregivers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Research Notes 14(1): 271. doi:10.1186/s13104-021-05686-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanow D. 2000. Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Yanow D. 2007. Interpretation in Policy Analysis: On Methods and Practice. Critical Policy Studies 1(1): 110–22. doi:10.1080/19460171.2007.9518511. [Google Scholar]

- Zagrodney K., Saks M. 2017. Personal Support Workers in Canada: The New Precariat? Healthcare Policy 13(2): 31–39. doi:10.12927/hcpol.2017.25324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeytinoglu I.u., Denton M. 2006, December. Satisfied Workers, Retained Workers: Effects of Work and Work Environment on Homecare Workers' Job Satisfaction, Stress, Physical Health, and Retention. Research Institute for Quantitative Studies in Economics and Population, McMaster University. Retrieved February 6, 2022. <https://scholar.google.ca/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=TFbRPTEAAAAJ&citation_for_view=TFbRPTEAAAAJ:Se3iqnhoufwC>.

- Zeytinoglu I.U., Denton M., Brookman C., Plenderleith J. 2014. Task Shifting Policy in Ontario, Canada: Does It Help Personal Support Workers' Intention to Stay? Health Policy 117(2): 179–86. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeytinoglu I.U., Denton M., Davies S., Plenderleith J.M. 2009. Casualized Employment and Turnover Intention: Home Care Workers in Ontario, Canada. Health Policy 91(3): 258–68. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeytinoglu I.U., Denton M., Plenderleith J., Chowhan J. 2015. Associations between Workers' Health, and Non-Standard Hours and Insecurity: The Case of Home Care Workers in Ontario, Canada. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 26(19): 2503–522. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.1003082. [Google Scholar]