Abstract

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-12 are two cytokines secreted by monocytes/macrophages in response to bacterial products which have largely opposite effects on the immune system. IL-12 activates cytotoxicity and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion by T cells and NK cells, whereas IL-10 inhibits these functions. In the present study, the capacities of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria to induce IL-10 and IL-12 were compared. Monocytes from blood donors were stimulated with UV-killed bacteria from each of seven gram-positive and seven gram-negative bacterial species representing both aerobic and anaerobic commensals and pathogens. Gram-positive bacteria induced much more IL-12 than did gram-negative bacteria (median, 3,500 versus 120 pg/ml at an optimal dose of 25 bacteria/cell; P < 0.001), whereas gram-negative bacteria preferentially stimulated secretion of IL-10 (650 versus 200 pg/ml; P < 0.001). Gram-positive species also induced stronger major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted IFN-γ production in unfractionated blood mononuclear cells than did gram-negative species (12,000 versus 3,600 pg/ml; P < 0.001). The poor IL-12-inducing capacity of gram-negative bacteria was not remediated by addition of blocking anti-IL-10 antibodies to the cultures. No isolated bacterial component could be identified that mimicked the potent induction of IL-12 by whole gram-positive bacteria, whereas purified LPS induced IL-10. The results suggest that gram-positive bacteria induce a cytokine pattern that promotes Th1 effector functions.

The innate immune system is an ancient defense system found in all multicellular organisms. It is comprised of cells and proteins which are able to recognize molecular patterns common to large groups of microorganisms (32). Recognition of such “danger signals” results in the activation of various types of effector functions that eliminate or wall off the microorganism, such as phagocytosis, mucus secretion, complement attack, coagulation, etc. (31).

Another important function of the innate immune system is to activate the more recently developed acquired immune system and to focus its attack on potentially dangerous antigens. T cells recognize their specific antigens in the form of peptides presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules on the surface of antigen-presenting cells, such as monocytes, dendritic cells, or Langerhans cells. Antigen-presenting cells react to bacterial stimulation by secretion of T-cell-activating cytokines and expression of membrane-bound costimulatory molecules which bind to corresponding receptors on T cells (9). Only if T cells receive such positive signals concomitantly with stimulation via their antigen-specific receptor will they become activated and an immune response be initiated (36). Thus, microbial products function as adjuvants which augment specific immune responses. In this way, the broad specificity and immediate action afforded by the ancient innate immune system may be combined with the infinite receptor repertoire and versatility of acquired immunity.

Two key cytokines that bridge the gap between innate and acquired immunity are interleukin 10 (IL-10) and IL-12. Both are produced by monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells in response to microbes (11, 18, 24), but they have largely opposite properties. IL-12 is a T-cell stimulatory cytokine which activates T cells and NK cells to secrete gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and to lyse target cells (40). T cells that are influenced by IL-12 during antigen presentation will mature into IFN-γ-producing cells (17, 39). IL-10, in contrast, downregulates T-cell cytotoxicity and IL-12 and IFN-γ production and decreases presentation of antigens for T cells (10, 13, 14). Instead, IL-10 stimulates B-cell maturation and antibody production (35).

We had previously observed that lactobacilli isolated from the human gastrointestinal mucosa, which are gram-positive commensal bacteria, induced secretion of large amounts of bioactive IL-12 from human monocytes, while gram-negative Escherichia coli induced very little IL-12, but more IL-10 (23). Along the same lines, pneumococci, which are gram-positive respiratory pathogens and commensals, triggered more IL-12 production from human mononuclear cells than gram-negative Haemophilus influenzae, while H. influenzae instead induced more IL-10 (2, 3). A similar discrepancy between a gram-positive bacterium and a gram-negative bacterium was also noted for the two oral pathogens Streptococcus mutans and Porphyromonas endodontalis (25). This prompted us to investigate whether gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria differ in their propensity to induce the partly opposite immunoregulatory cytokines IL-12 and IL-10.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and bacterial components.

Gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial species of types inhabiting human respiratory or gastrointestinal mucosa were obtained from the Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg (CCUG; Göteborg, Sweden). They represented both clinical and commensal isolates (Table 1). A Lactobacillus plantarum strain was isolated from rectal mucosa of a healthy human volunteer; this species represents the major lactobacillus group colonizing the human gastrointestinal tract (1). In addition, one strain each of Bifidobacterium sp., Clostridium perfringens, Enterococcus sp., Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacteroides sp. isolated from the feces of healthy breast-fed Swedish infants were included. These isolates had been passaged no more than two times and were stored frozen at −70°C before being used in the study.

TABLE 1.

Cytokine response of human monocytes to various gram-positive and gram-negative bacteriaa

| Bacterial species (strain) | Isolation site | Metabolism | Concn (pg/ml) of:

|

IL-12/IL-10 ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12 | IL-10 | ||||

| Gram positive | |||||

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis (18363) | Adult intestine | Anaerobic | 4,300 ± 810 | 160 ± 28 | 27 |

| Clostridium perfringens (1795) | Bovine | Anaerobic | 160 ± 4 | 120 ± 13 | 1.3 |

| Corynebacterium minutissimum (541) | Erythrasma, trunk | Aerobic | 2,000 ± 340 | 390 ± 99 | 5.1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis (19916) | Unknown | Aerobic | 3,500 ± 660 | 200 ± 47 | 18 |

| Lactobacillus plantarum (67b) | Rectum, healthy | Aerobic | 2,200 ± 540 | 160 ± 50 | 14 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (1800) | Pleural fluid | Aerobic | 4,000 ± 850 | 240 ± 83 | 17 |

| Streptococcus mitis (31611) | Oral cavity | Aerobic | 3,600 ± 490 | 200 ± 44 | 18 |

| Gram negative | |||||

| Bacteroides vulgatus (4940) | Unknown | Anaerobic | 32 ± 2 | 350 ± 39 | 0.09 |

| Escherichia coli (24) | Urine, cystitis | Aerobic | 140 ± 60 | 1,200 ± 280 | 0.12 |

| Haemophilus influenzae (21594) | Pharynx, healthy | Aerobic | 90 ± 23 | 560 ± 100 | 0.16 |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae (12836) | Septic finger | Aerobic | 120 ± 50 | 650 ± 120 | 0.18 |

| Neisseria sicca (23929) | Pharynx, healthy | Aerobic | 460 ± 160 | 690 ± 150 | 0.67 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (551) | Unknown | Aerobic | <30 | 480 ± 120 | 0.06 |

| Veillonella parvula (5123) | Intestinal tract | Anaerobic | 1,600 ± 480 | 770 ± 200 | 2.08 |

Human monocytes from nine blood donors were purified by adherence and stimulated with each of 14 bacterial strains at a concentration of 5 × 106 UV-killed bacteria/ml. The bacteria were obtained from the CCUG, and their CCUG number given in parentheses. The L. plantarum strain was isolated from healthy human gastrointestinal mucosa (1). IL-12 p70, and IL-10 concentrations were measured by ELISA in the supernatant after 24 h. The results represent the mean and standard error for the responses of the nine blood donors to each bacterial strain.

Bacteria were cultured on blood agar aerobically overnight or anaerobically for 3 days, harvested in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed, and suspended at a concentration of 109/ml, corresponding to an optical density at 597 nm (OD597) of 0.96 (Vitatron; Bergström Instruments, Göteborg, Sweden). The bacteria were killed by exposure to UV light for 15 min, which was confirmed by a negative viable count, and stored at −20°C.

Peptidoglycan from S. aureus and lipoteichoic acids from S. aureus and Enterococcus faecalis were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), E. coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was purified by the phenol-water extraction method (16); DNA from S. aureus, prepared as described in reference 12, was a gift from L. V. Collins (Department of Rheumatology, University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden); and CpG and GpC oligonucleotides (5′-TCCATGACGTTCCTGATGCT-3′ and 5′-TCCATGAGCTTCCTGATGCT-3′, respectively) were synthesized by Scandinavian Gene Synthesis AB (Köping, Sweden).

Preparation and stimulation of blood monocytes and mononuclear cells.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from healthy blood donors by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep, Nyegaard, Norway) for 20 min at 800 × g. Monocytes were purified by plating mononuclear cells at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml in flat-bottom 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in pyrogen-free RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Edinburgh, Scotland) with 5% pooled fresh homologous serum from individuals of the AB blood group. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, nonadhering cells were removed by gentle flushing of the wells with warm medium. In some experiments, unfractionated blood cells were used at 2 × 106/ml without prior adherence. RPMI 1640 medium with 5% inactivated human AB serum (Sigma), 50 mM gentamicin (Sigma), and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco) was added, containing 5 × 105, 5 × 106, or 5 × 107 bacteria/ml (corresponding to approximately 2.5, 25, or 250 bacteria/monocyte) or the following final concentrations of isolated bacterial components: peptidoglycan, lipoteichoic acid, LPS, and bacterial DNA, 10 ng to 10 μg/ml; or synthetic oligonucleotides, 120 ng to 120 μg/ml. To examine the effect of bacterial viability on monocyte responses, dead or live S. aureus and E. coli cells at 5 × 106 or 5 × 107 bacteria/ml were added to cultures not containing gentamicin.

For assessment of lymphocyte IFN-γ production and proliferation in response to bacteria, 2 × 106 unfractionated blood mononuclear cells/ml were stimulated for 5 days with 5 × 105, 5 × 106, or 5 × 107 bacteria/ml or with 5 μg of phytohemagglutinin per ml (Sigma). Proliferation was assessed by incorporation of 5 μCi of tritium-labelled thymidine per ml (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) for 6 h. The cells were harvested onto glass filters, and radioactivity was analyzed in a beta counter (Matrix 96; Canberra Packard, Uppsala, Sweden). The dependence of IFN-γ and proliferation on MHC class II antigen presentation was tested by adding blocking mouse anti-human HLA-DP, -DQ, or -DR antibodies (Becton Dickinson, Paramus, N.J.) or control antibodies of the corresponding isotype (final concentration, 2.5 μg/ml) to the cultures before stimulation.

IL-12 determination.

IL-12 concentrations were determined by using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) specific for p70, which is the bioactive form of IL-12 composed of the two subunits p35 and p40 (41). The specificity of the ELISA was demonstrated by the fact that free IL-12 p40 monomers (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom) did not give rise to any signal above background levels.

Microtiter plates (Maxisorp; Nunc) were coated overnight at 4°C with monoclonal mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antihuman IL-12 antibody (clone B-P24; Diaclone, Besançon, France [unknown concentration]) diluted 1/200 in PBS. The plates were washed and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) in PBS for 2 h at room temperature, emptied, and left to dry overnight. Culture supernatants were diluted 1:5, 1:25, or 1:125 in PBS with 1% BSA and incubated for 2 h together with biotinylated monoclonal mouse IgG1 anti-human IL-12 (clone B-T21; Diaclone [unknown concentration]) diluted 1/100 in PBS with 1% BSA. After washing, the plates were incubated with a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Diaclone) diluted 1/6,700 for 20 min. The plates were washed and incubated for 20 min with tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Diaclone). The reaction was stopped with 1 M H2SO4, and the color reaction was measured as the OD450 in a spectrophotometer (Titertec Multiscan; Flow Laboratories, Maclean, Va.). The limit of detection of the assay was 6 pg/ml.

IFN-γ, IL-10, and TNF-α determination.

Supernatant concentrations of IFN-γ, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were measured by sandwich ELISAs with identical protocols, but different reagents. Polystyrene microtiter plates (Maxisorp; Nunc) were coated overnight at 4°C with 2 μg of either mouse IgG1 monoclonal anti-human IFN-γ (Coatech AB, Ljungby, Sweden), rat IgG1 monoclonal anti-human IL-10 (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), or mouse IgG1 monoclonal antihuman TNF-α (Nordic Biosite AB, Täby, Sweden) antibody per ml diluted in bicarbonate buffer (Na2CO3, 1.6 g/liter; NaHCO3, 2.9 g/liter; NaN3, 0.2 g/liter [pH 9.5]). The plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Kebo Lab, Spånga, Sweden) and blocked for 1 h with 2% BSA in PBS at room temperature. After the plates had been washed with PBS-Tween, the supernatants were diluted 1:2, 1:5, or 1:25 in dilution buffer (10 g of BSA per liter, 40 g of NaCl per liter, 0.5 g of NaN3 per liter, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated at room temperature for 3 h. After washing, the biotinylated IgG1 monoclonal antihuman IFN-γ (0.1 μg/ml) (Coatech AB), IgG2a antihuman IL-10 (2 μg/ml) (Pharmingen), and mouse IgG1 antihuman TNF-α (0.5 μg/ml) (Nordic Biosite) antibodies were added, and the plates were incubated for another 2 h at 37°C. The plates were washed and incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated ExtrAvidin (Sigma), diluted 1/2,000 for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, the substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate in diethanolamine buffer (pH 9.8) was added. The color reaction was measured as the OD405 in a spectrophotometer (Titertec Multiscan; Flow Laboratories). Recombinant human IFN-γ (Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.), human IL-10 (R&D Systems), and human TNF-α (R&D Systems) of 97 to 99% purity were used as standards. The sensitivities of the assays were 15 U/ml for IFN-γ (which corresponds to 60 pg/ml), 25 pg/ml for IL-10, and 25 pg/ml for TNF-α.

Blocking of IL-10.

For inhibition experiments, rat IgG1 anti-human IL-10 antibodies or rat IgG1 control antibodies (both from Pharmingen) were added to the monocyte cell cultures at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml before the addition of bacteria (final concentration, 5 × 106 bacteria/ml). IL-10 and IL-12 concentrations in supernatants were measured by ELISA after 24 h.

Statistical analysis.

Nine blood donors were tested with each of the 14 bacterial strains. Each person's average response to the seven gram-positive bacteria was calculated and compared to that person's average response to the seven gram-negative bacterial species, by using Wilcoxon's signed-rank test for paired samples. For responses to the individual bacterial strains, the mean and standard error were calculated from the responses of all donors tested.

RESULTS

IL-12 and IL-10 responses by human monocytes or PBMCs in response to whole gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.

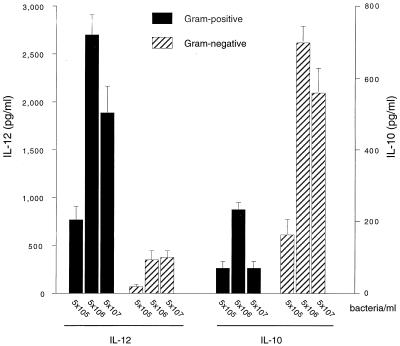

Monocytes from nine blood donors were stimulated with each of seven gram-positive and seven gram-negative bacterial strains representing both commensal and pathogenic bacteria of types inhabiting the nasopharynx or gastrointestinal tract. IL-12 and IL-10 concentrations in the supernatant were maximal after 24 h. Regardless of bacterial concentration, gram-positive bacteria induced much higher levels of IL-12 than did gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 1). A concentration of 5 × 106 gram-positive bacteria/ml (corresponding to approximately 25 bacteria/monocyte) elicited the maximal response. This concentration of gram-positive bacteria triggered an average IL-12 concentration of 3,500 pg/ml, compared to 120 pg/ml triggered by gram-negative bacteria (P < 0.001).

FIG. 1.

IL-12 p70 and IL-10 responses by monocytes from nine blood donors stimulated with each of seven gram-positive and seven gram-negative species separately. Concentrations ranged from 5 × 105 to 5 × 107 bacteria/ml. Cytokines were measured in 24-h culture supernatants by ELISA. Each bar represents the mean response of all donors to all gram-positive or gram-negative bacterial strains at a particular concentration. The error bars represent standard errors for the variability between the bacterial species.

Conversely, gram-negative bacteria induced more IL-10 than did gram-positive bacteria at all concentrations tested (Fig. 1), the median level at 5 × 106 bacteria/ml being 650 pg/ml versus 200 pg/ml (P < 0.001). IL-12 and IL-10 were not detected in cultures without bacteria (data not shown).

As seen in Table 1, all individual species of gram-positive bacteria, with the exception of C. perfringens, induced uniformly high levels of IL-12 p70 regardless of whether they represented commensal or pathogenic isolates or whether they had an aerobic or anaerobic metabolism. Conversely, all gram-negative bacteria, with the exception of the anaerobic colonic bacterium Veillonella parvula, were very poor inducers of IL-12. E. coli was the most efficient inducer of IL-10 among the gram-negative bacteria. The ratio of IL-12 to IL-10 production ranged between 1.3 and 27 for gram-positive bacteria (median, 17.5) and between 0.06 and 2.1 for gram-negative bacteria, the median being 0.16.

We also tested unfractionated blood mononuclear cells for their responsiveness to whole bacteria. Instead of washing away nonadherent cells, the whole mixture of cells was stimulated with the bacterial strains indicated above. Despite overall lower IL-12 concentrations in such cultures compared to those in cultures with monocytes, the difference in IL-12 responses to gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria remained (1,800 ± 290 pg/ml versus 60 ± 10 pg/ml; P < 0.001). IL-10 production was instead four times larger in mononuclear cells than that in adhered monocytes, but the difference between gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria was seen equally well (860 ± 90 versus 2,800 ± 210 pg/ml; P < 0.001).

Levels of stimulation of cells with UV-killed or live bacteria were compared. Dead or live S. aureus and E. coli cells at 5 × 106 or 5 × 107 bacteria/ml were added to antibiotic-free monocyte cultures. Live S. aureus and E. coli cells were no more effective in inducing either IL-12 or IL-10 than were dead bacteria of the same species (data not shown). Freezing and thawing of UV-killed bacteria did not change their capacity to induce either IL-10 or IL-12.

The culture collection strains used had been stored for extended periods of time and had probably also been passaged many times. Fecal bacteria, recently isolated from newborn infants, that had been passaged only twice in vitro and thereafter stored at −70°C were used to stimulate mononuclear cells from three additional blood donors. These bacteria belonged to the following genera or species: Bifidobacterium sp., C. perfringens, Enterococcus sp., S. aureus, and Bacteroides sp. The responses were very similar to those elicited by culture collection strains of the same species (data not shown).

Blocking of IL-10.

Since IL-10 is known to counteract the production of IL-12 (10), the poor IL-12-inducing capacity of the gram-negative species could be secondary to their capacity to promote IL-10 production. To test this hypothesis, a neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody was added to the monocyte cultures before stimulation with bacteria. This treatment increased the production of IL-12 in response to both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, but gram-positive bacteria were still vastly better inducers of IL-12 than gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 2). IL-10 levels were undetectable in cultures after addition of neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibodies (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

IL-12 p70 responses in supernatants after addition of anti-IL-10 antibodies or control IgG1 antibodies to the monocyte cultures before stimulation with 5 × 106 bacteria/ml. IL-12 was measured after 24 h. Bars represent the mean responses of three donors, and the error bars represent standard errors of the means.

Role of bacterial components in induction of IL-12 and IL-10.

Because the results presented above indicated that gram-positive, but not gram-negative, bacteria contained structures capable of efficient triggering of IL-12 production by monocytes, we tested whether isolated bacterial components such as peptidoglycan, lipoteichoic acid, or gram-positive bacterial DNA could induce IL-12 from purified monocytes. However, although peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acids induced some TNF-α when used in quite high concentrations, neither of these components stimulated production of IL-12 above the background level of 30 pg/ml (Table 2). Likewise, bacterial DNA purified from S. aureus in concentrations up to 10 μg/ml or CpG oligonucleotides up to 120 μg/ml were completely ineffective in inducing IL-12 production from human monocytes (data not shown). In contrast to the gram-positive bacterial components, E. coli LPS induced IL-12 production of a magnitude similar to that seen in response to whole gram-negative bacteria.

TABLE 2.

Monocyte cytokine response to bacterial componentsa

| Final concn of component | Concn (pg/ml) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12 p70 | IL-10 | TNF-α | |

| E. coli LPS | |||

| 10 μg/ml | 270 ± 240 | 630 ± 180 | 20,000 ± 10,000 |

| 1 μgml | 310 ± 210 | 660 ± 240 | 17,000 ± 9,500 |

| 100 ngml | 410 ± 260 | 600 ± 210 | 15,000 ± 8,300 |

| 10 ng/ml | 370 ± 220 | 600 ± 230 | 11,000 ± 5,700 |

| S. aureus peptidoglycan | |||

| 10 μg/ml | <30 | <50 | 9,200 ± 890 |

| 1 μgml | <30 | <50 | 3,000 ± 100 |

| 100 ngml | <30 | <50 | <50 |

| 10 ng/ml | <30 | <50 | <50 |

| S. aureus lipoteichoic acid | |||

| 10 μg/ml | <30 | <50 | 1,000 ± 70 |

| 1 μgml | <30 | <50 | <50 |

| 100 ngml | <30 | <50 | <50 |

| 10 ng/ml | <30 | <50 | <50 |

| E. faecalis lipoteichoic acid | |||

| 10 μg/ml | <30 | <50 | 2,500 ± 570 |

| 1 μgml | <30 | <50 | <50 |

| 100 ngml | <30 | <50 | <50 |

| 10 ng/ml | <30 | <50 | <50 |

Monocytes from three blood donors were purified by adherence and stimulated with purified bacterial components in various concentrations. The concentrations of cytokines in supernatants by 24 h were measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean ± standard error for three blood donors.

E. coli LPS was efficient in stimulating IL-10 as well as TNF-α production, inducing TNF-α responses at 1,000-fold-lower concentrations than those required with peptidoglycan or the lipoteichoic acids. Neither peptidoglycan nor lipoteichoic acids or bacterial DNA preparations induced IL-10 at any of the concentrations tested.

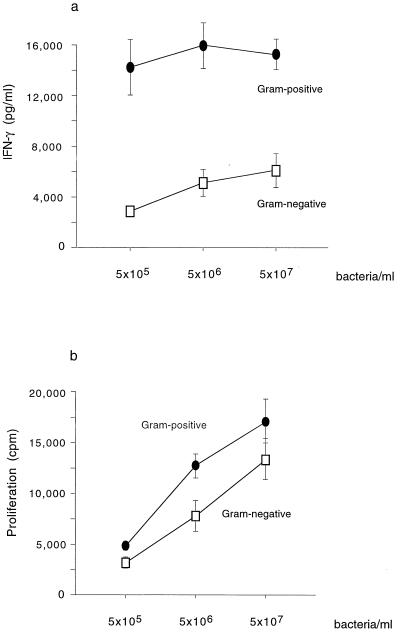

IFN-γ responses and proliferation by PBMCs in response to whole bacteria.

IL-12 upregulates IFN-γ production and proliferation by NK and T cells, while IL-10 decreases it. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria were tested for their capacity to stimulate production of IFN-γ and proliferation of unfractionated mononuclear cells in 5-day cultures. Indeed, much more IFN-γ was produced in response to gram-positive bacteria than to gram-negative bacteria (P < 0.001) and the former also induced somewhat better proliferative responses (Fig. 3). Both IFN-γ production and proliferation in response to the various bacteria were MHC class II dependent, since neutralizing antibodies to HLA-DP, -DQ, and -DR on average reduced IFN-γ production and proliferation by 69 and 71%, respectively.

FIG. 3.

IFN-γ production (a) and proliferation (b) on day 5 by unfractionated blood mononuclear cells from nine donors stimulated with each of seven gram-positive and seven gram-negative species in concentrations ranging from 5 × 105 to 5 × 107 bacteria/ml. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria induce different patterns of immunoregulatory cytokines: gram-positive bacteria induced on average 18 times more IL-12 than IL-10 in human monocytes, while gram-negative bacteria on average induced 7 times more IL-10 than IL-12. This discrepancy was seen with dead or live, aerobic or anaerobic, and commensal or pathogenic bacteria regardless of whether the bacteria had recently been isolated or were from a culture collection.

Production and secretion of IL-10 from human monocytes in response to gram-negative bacteria probably depended on their LPS, which efficiently triggers IL-10 production according to the present and previously published results (5, 6). However, isolated LPS could not induce as much IL-10 as intact gram-negative bacteria. This, plus the fact that gram-positive bacteria, which lack LPS, still gave rise to some IL-10 production, suggested that other bacterial components as well may trigger production of this cytokine, although less effectively. Alternatively the IL-10 produced in response to gram-positive bacteria is simply an intrinsic negative feedback mechanism induced by the abundant production of IL-12, since IL-12 has been shown to induce IL-10 (33). Because IL-10 represses the formation of IL-12 (10), one could anticipate that the poor IL-12-inducing capacity of gram-negative bacteria was secondary to the higher levels of IL-10 produced in response to these bacteria. However, blocking of IL-10 in the cultures did not remediate IL-12 induction of gram-negative bacteria. The potent capacity to stimulate IL-12 thus appears to be an inherent property of gram-positive bacteria.

Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria have been evolutionarily separated and have developed in parallel for very long time (21). The cell walls of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria differ in several respects. The gram-positive reaction is thought to depend on the exceptional thickness and rigidity of their peptidoglycan layer in gram-positive bacteria, which prevents leakage of crystal violet-protein complexes from the cell (8). Gram-positive bacteria have peptidoglycan layers approximately 50 times thicker than those of gram-negative bacteria, and the peptidoglycan strands are also more tightly cross-linked (22). Furthermore, teichoic and lipoteichoic acids are unique to gram-positive bacteria (4, 15).

The fact that the gram-positive anaerobic bacterium C. perfringens was inefficient in inducing IL-12 indicated that the cell wall provided the stimulus for IL-12 production. Clostridia often show poor development of their peptidoglycan layer during stationary culture conditions (7). Indeed, when our C. perfringens culture was gram stained, >90% of the bacterial cells appeared gram negative. One gram-negative bacterium, the obligately anaerobic intestinal commensal species V. parvula, induced IL-12 responses almost as high as those of the gram-positive bacteria. We have no explanation for this finding.

We could not identify any component of the gram-positive bacterial cell wall that mimicked the impressive IL-12-inducing effect of intact bacteria. Peptidoglycan induced TNF-α synthesis when used in quite high doses, as has previously been reported (30, 38), but no functional IL-12 (i.e., p70 dimer). Neither could lipoteichoic acid, purified bacterial DNA from S. aureus, or nonmethylated CpG motifs typical of bacterial DNA trigger production of IL-12 in human monocytes, in contrast to previous findings with murine cells (27). Conceivably a combination of certain bacterial and particular structural motifs needs to be present to optimally interact with receptors on monocytes that, when triggered, induce the synthesis of IL-12. In line with this, we observed that sonication of gram-positive bacteria reduced their IL-12-inducing capacity (unpublished observation), while live or killed bacteria were equally effective. Alternatively, a yet-undefined component of gram-positive bacteria is responsible for their strong IL-12-inducing capacity. Thus, due to their evolutionary separateness, a number of structures may also differ between these two types of bacteria (20).

IL-12 activates T cells and NK cells to proliferate, produce IFN-γ, and lyse target cells (40), while IL-10 downregulates these functions, but instead stimulates B-cell maturation (35). Thus, gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria may exhibit fundamentally different adjuvant functions. Indeed, gram-positive bacteria induced more IFN-γ than did gram-negative bacteria. This response was suggestedly antigen dependent, since it was highly dependent on MHC class II recognition. It is highly unlikely that normal individuals have much stronger T-cell memory for each of the seven gram-positive species than for the seven gram-negative species. More likely, people have T-cell memory for protein antigens from gram-positive as well as gram-negative bacteria, but the strong T-cell activation by gram-positive bacteria probably results from the high levels of IL-12 and low levels of IL-10 produced by antigen-presenting cells in response to these bacteria. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria have also been shown to induce different patterns of costimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells which could contribute to diverging T-cell responses to gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (26). Our data suggest that gram-positive bacteria could be especially suited as adjuvants for Th1-type responses.

Responses to natural infections support our findings, in that patients suffering from meningitis due to gram-positive pneumococci have higher levels of IFN-γ in the cerebrospinal fluids than patients with the same disease caused by gram-negative H. influenzae (19, 28). In line with this, the gram-positive bacterium S. mutans elicited strong IL-12 and IFN-γ responses in vitro and pronounced inflammatory infiltrates in vivo, while the gram-negative bacterium P. endodontalis induced no IL-12 or IFN-γ and only mild inflammatory infiltration in mice injected with the two bacterial species into the scalp (25).

IFN-γ increases lysozyme production (29) and bactericidal capacity in macrophages (34). TNF-α synergizes with IFN-γ in promoting killing of intracellular bacteria (37). We have noted that gram-positive bacteria induce more TNF-α than gram-negative bacteria, while other proinflammatory cytokines are equally or more strongly triggered by gram-negative bacteria than by gram-positive bacteria (C. Hessle et al., unpublished data). Thus, the cytokines preferentially induced by gram-positive bacteria (i.e., IL-12, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) should synergize to increase the capacity of macrophages to kill and digest bacteria that they have phagocytosed. It is possible that this type of response has evolved to cope with the exceptional sturdiness of the gram-positive cell wall.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The skillful technical assistance of Britt-Marie Essman is greatly appreciated.

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Council for Forestry and Agricultural Research and the Swedish Medical Research Council (no. K98-06X-12612-01A).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahrné S, Nobaek S, Jeppsson B, Alderberth I, Wold A E, Molin G. The normal Lactobacillus flora of healthy human rectal and oral mucosa. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:88–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvå E, Andersson B. Induction of phagocyte-stimulating and Th1-promoting cytokines by in vitro stimulation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:417–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvå E, Andersson B. Induction of phagocyte-stimulating cytokines by in vitro stimulation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells with Haemophilus influenzae. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:411–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baddiley J. Bacterial cell wall and membranes. Discovery of the teichoic acids. Bioessays. 1989;10:207–210. doi: 10.1002/bies.950100607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barsig J, Kusters S, Vogt K, Volk H D, Tiegs G, Wendel A. Lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-10 in mice: role of endogenous tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2888–2893. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg D J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K, Muller W, Menon S, Davidson N, Grunig G, Rennick D. Interleukin-10 is a central regulator of the response to LPS in murine models of endotoxic shock and the Shwartzman reaction but not endotoxin tolerance. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:2339–2347. doi: 10.1172/JCI118290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beveridge T J. Mechanism of Gram variability in select bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1609–1620. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1609-1620.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beveridge T J. Ultrastructure, chemistry, and function of the bacterial wall. Int Rev Cytol. 1981;72:229–317. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croft M, Dubey C. Accessory molecule and costimulation requirements for CD4 T cell response. Crit Rev Immunol. 1997;17:89–118. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v17.i1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Andrea A, Aste-Amezaga M, Valiante N M, Ma X, Kubin M, Trinchieri G. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits human lymphocyte interferon gamma-production by suppressing natural killer cell stimulatory factor/IL-12 synthesis in accessory cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1041–1048. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Andrea A, Rengaraju M, Valiante N M, Chehimi J, Kubin M, Aste M, Chan S H, Kobayashi M, Young D, Nickbarg E, et al. Production of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin 12) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1387–1398. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng G M, Nilsson I M, Verdrengh M, Collins L V, Tarkowski A. Intra-articularly localized bacterial DNA containing CpG motifs induces arthritis. Nat Med. 1999;5:702–705. doi: 10.1038/9554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor C G, de Vries J E. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiorentino D F, Zlotnik A, Mosmann T R, Howard M, O'Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer W. Bacterial phosphoglycolipids and lipoteichoic acids. New York, N.Y: Plenum; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galanos C, Luderitz O, Westphal O. A new method for the extraction of R lipopolysaccharides. Eur J Biochem. 1969;9:245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1969.tb00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerosa F, Paganin C, Peritt D, Paiola F, Scupoli M T, Aste-Amezaga M, Frank I, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 primes human CD4 and CD8 T cell clones for high production of both interferon-gamma and interleukin-10. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2559–2569. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giambartolomei G H, Dennis V A, Lasater B L, Philipp M T. Induction of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins in monocytes is mediated by CD14. Infect Immun. 1999;67:140–147. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.140-147.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glimåker M, Olcén P, Andersson B. Interferon-γ in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with viral and bacterial meningitis. Scand J Immunol. 1994;26:141–147. doi: 10.3109/00365549409011777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grundy F J, Henkin T M. A regulatory system hitherto found only in gram-positive bacteria in a gram-negative bacterium that grows only in co-culture with a bacillus strain. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:667–668. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta R S. What are archaebacteria: life's third domain or monoderm prokaryotes related to gram-positive bacteria? A new proposal for the classification of prokaryotic organisms. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:695–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond S M, Lambert P A, Rycroft A N. The bacterial cell surface. Washington, D.C.: Kapitan Szabo Publishers; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hessle C, Hanson L Å, Wold A E. Lactobacilli from human gastrointestinal mucosa are strong stimulators of IL-12 production. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116:276–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00885.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh C S, Macatonia S E, Tripp C S, Wolf S F, O'Garra A, Murphy K M. Development of TH1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science. 1993;260:547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang Y, Magli L, Russo M. Bacterium-dependent induction of cytokines in mononuclear cells and their pathologic consequences in vivo. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2125–2130. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2125-2130.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller R, Keist R, Joller P. Macrophage response to microbial pathogens: modulation of the expression of adhesion, CD14, and MHC class II molecules by viruses, bacteria, protozoa and fungi. Scand J Immunol. 1995;42:337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klinman D M, Yi A K, Beaucage S L, Conover J, Krieg A M. CpG motifs present in bacteria DNA rapidly induce lymphocytes to secrete interleukin 6, interleukin 12, and interferon gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2879–2883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornelisse R F, Hack C E, Savelkoul H F J, van der Pouw Kraan T C T M, Hop W C J, van Mierlo G, Suur M H, Neijens H J, de Groot R. Intrathecal production of interleukin-12 and gamma interferon in patients with bacterial meningitis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:877–881. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.877-881.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis C E, McCarthy S P, Lorenzen J, McGee J O. Differential effects of LPS, IFN-gamma and TNF alpha on the secretion of lysozyme by individual human mononuclear phagocytes: relationship to cell maturity. Immunology. 1990;69:402–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattsson E, Verhage L, Rollof J, Fleer A, Verhoef J, van Dijk H. Peptidoglycan and teichoic acid from Staphylococcus epidermidis stimulate human monocytes to release tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;7:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matzinger P. An innate sense of danger. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:399–415. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medzhitov R, Janeway C A., Jr Innate immunity: impact on the adaptive immune response. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:4–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyaard L, Hovenkamp E, Otto S A, Miedema F. IL-12-induced IL-10 production by human T cells as a negative feedback for IL-12-induced immune responses. J Immunol. 1996;156:2776–2782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray H W, Cartelli D M. Killing of intracellular Leishmania donovani by human mononuclear phagocytes. Evidence for oxygen-dependent and -independent leishmanicidal activity. J Clin Investig. 1983;72:32–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI110972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rousset F, Garcia E, Defrance T, Peronne C, Vezzio N, Hsu D H, Kastelein R, Moore K W, Banchereau J. Interleukin 10 is a potent growth and differentiation factor for activated human B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1890–1893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz R H. A cell culture model for T lymphocyte clonal anergy. Science. 1990;248:1349–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.2113314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva J S, Vespa G N R, Cardoso M A G, Aliberti J C S, Cunha F Q. Tumor necrosis factor alpha mediates resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice by inducing nitric oxide production in infected gamma interferon-activated macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4862–4867. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4862-4867.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timmerman C P, Mattsson E, Martinez-Martinez L, De Graaf L, Van Strijp J A G, Verbrugh H A, Verhoef J, Fleer A. Induction of release of tumor necrosis factor from human monocytes by staphylococci and staphylococcal peptidoglycans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4167–4172. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4167-4172.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trinchieri G. Cytokines acting on or secreted by macrophages during intracellular infection (IL-10, IL-12, IFN-gamma) Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine produced by antigen-presenting cells with immunoregulatory functions in the generation of T-helper cells type 1 and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;84:4008–4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolf S F, Temple P A, Kobayashi M, Young D, Dicig M, Lowe L, Dzialo R, Fitz L, Ferenz C, Hewick R M, et al. Cloning of cDNA for natural killer cell stimulatory factor, a heterodimeric cytokine with multiple biologic effects on T and natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1991;146:3074–3081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]