Abstract

Artemether, an artemisinin derivative, is a component of the commonly used artemisinin-based combination therapy, artemether-lumefantrine. In this study, we cloned the VH and VL genes of a cell line (mAb 2G12E1) producing a monoclonal antibody specific to artemether, and used to construct a recombinant DNA of single-chain variable fragment (scFv). The scFv was constructed into prokaryotic expression vectors pET32a (+), pET22b (+), pGEX-2T, and pMAL-p5x, respectively. However, only the pMAL-p5x/scFv could be induced to express soluble scFv with comparable sensitivity and specificity to that of mAb 2G12E1. Based on the anti-artemether scFv, an indirect competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (icELISA) was developed. The 50% of inhibition concentration (IC50) value and the working range based on IC20 to IC80 were 4.33 ng mL−1 and 1.05–22.65 ng mL−1, respectively. The artemether content in different drugs were determined by the developed icELISA, and the results were consistent to those determined by ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC). The anti-artemether scFv prepared in the current study could be a valuable genetically engineered antibody applied for artemether monitoring and specific binding mechanism studying.

Keywords: Artemether, scFv, ELISA, Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), Malaria

1. Introduction

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the frontline treatment for falciparum malaria. More than 3.5 billion treatment courses of ACTs were sold from 2010 to 2020 [1]. Commercial artemisinin derivatives include artemether, dihydroartemisinin, and artesunate. ACTs are used to treat uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in children and adults, except for pregnant women in their first trimester [2, 3]. Fake and substandard ACTs containing little or no active ingredients are not only life-threatening but also promote the development of resistance in malaria parasites. Falsified antimalarial drugs have been a serious problem in many malaria-endemic areas, including Southeast Asia, India, and Africa, which significantly threatens the global malaria elimination campaign [4, 5]. To facilitate the antimalarial drugs quality surveys in the remote endemic region, that lack of expensive instrucments and trained personnel, there is a need to develop point-of-care devices such as lateral flow dipstick assays based on antibodies for rapid and high throughput detection in the field.

Immunoassay has been used for quantifying artemisinin and its derivatives [6-11]. Song et al. [6] reported polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) recognizing artesunate, dihydroartemisinin, and artemether. A radioimmunoassay based on these pAbs was used to determine artesunate and its active metabolites in pharmacokinetic studies in dogs [6]. Ferreira et al. [7] developed a pAb, which had a similar response to artemisitene and dihydroartemisinin at all dilutions [7]. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) based on this pAb was used to quantify the artemisinin content in different organs of greenhouse-grown plants and eight clones of Artemisia annua grown in tissue culture [7]. The monoclonal antibody (mAb) F170-10 was specific to artelinic acid, while it also recognized artemisinin (3–5% cross-reactivity) and artemether (3–5% cross-reactivity). An inhibition ELISA was used to detect artemisinin compounds in urine [8]. The mAbs raised by immunogen through conjugation of carrier protein to position 12 of artesunate (Fig. 1) usually showed low cross-reactivity with artemether [9, 10]. Our laboratory adopted a new hapten design strategy introducing a hydroxy group at position 9 of artemether and successfully developed a specific mAb 2G12E1against artemether, allowing more accurate differentiation between artemisinin and its derivatives (Fig. 1) [11].

Fig. 1.

Structures of artemisinin and its analogs

Single-Chain Variable Fragment (scFv) is the smallest functional unit of mAb, which connects the variable domains of heavy and light chains by linker peptides. Compared with mAb, scFvs have the advantages of smaller size, better tissue penetration, weaker immunogenicity and ease of modification, and can be economical produced by bacteria with high yield [12]. ScFvs have been widely used in fields, such as biomedical, immune detection and so on [12]. However, the sensitivity of scFvs without directed evolution and modification in vitro was usually less than those of mAbs or pAbs. For example, the anti-amantadine wild-type scFv possessed 13.5 ng mL−1 of IC50 value, which was about 33 times less sensitive than the parental mAb (0.41 ng mL−1) [13, 14]. The IC50 of 3-phenoxybenzoic acid scFv was 550 ng mL−1 [15], which was higher than those of pAbs (120 ng mL−1 for homologous coating antigens and 1.65 ng mL−1 for heterologous coating antigens) [16]. The IC50 value of the assay established with the anti-enrofloxacin scFv was 26.23 ng mL−1, compared with 0.56 ng mL−1 of a mAb [17, 18]. The production of recombinant scFv can encounter a solubility problem. The recombinant scFv sometimes exists in the inclusion body in Escherichia coli, which needs refolding [19-21]. The solubility and antigen-binding activity of scFv can be improved by co-expression with N-terminal signal peptides or fusing with solubility-enhancing tags [14, 20-23]. The expression level of the soluble scFv with or without the the pectate lyase B signal leader (pelB) had a 20 times difference, and the binding activity of scFv without the pelB leader was far below that with the pelB leader [22]. The maltose binding protein (MBP) fused HER2 (scFv)-PE24B was highly soluble and showed stronger cytotoxicity than HER2 (scFv) [23].

ScFvs are also commonly used for studying antigen-antibody binding mechanisms. Li et al. [24] found that the key amino acids of KA/2A9/3 scFv were TYR-92 (CDRL3), SER-93 (CDRL3), ASP-155 (CDRH1), and GLY-226 (CDRH3), and the hydrogen bond was the main force using homologous modeling and molecular docking. The analysis of the scFv-CD52 interactions showed that the mutants D53K, K54D, and K56D resulted in less attractive binding free energy, therefore lower scFv-CD52 affinity than the native scFv [25]. Rangnoi et al. [26] demonstrated that the VH domain played an important role in the binding of scFv to free aflatoxin B1.

An scFv and an antigen-binding fragment (Fab) against artemisinin and artesunate have been reported earlier [27]. In this study, the genes for the VH and VL fragment of the hybridoma cell line 2G12E1 were sequenced, and the complementarity-determining regions (CDR) were analyzed using the Kabat and Chothia numbering scheme. The anti-artemether recombinant scFv was expressed in different prokaryotic expression systems and evaluated by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors. This study aims to prepare a highly sensitive scFv for rapid quality monitoring of artemether in antimalarial drugs and studying the antibody recognition mechanism of artemisinin derivatives in the future.

2. Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

The artemether mAb cell line 2G12E1 and 9-hydroxyartemether-bovine serum albumin (BSA) were previously prepared and described [11]. Cell culture medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Gibco BRL (PaisLey, Scotland). Primer sets used to clone the antibody variable genes were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Thermo Scientific GeneJET RNA Purification Kit and Thermo Scientific RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., Ltd. (Vilnius, Lithuania). E. coli competent cells were from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The DNA restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and pMD™19-T vector were purchased from Takara (Kyoto, Japan). The pMAL-p5x expression vector was from the New England Biolabs Inc. (Ipswich, MA, USA). The MBP-Tag mouse monoclonal antibody was obtained from Lablead (Beijing, China). Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG was purchased from Jackson (West Grove, PA, USA). Artemether was purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Dihydroartemisinin and 3, 3’, 5, 5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Artemisinin and artesunate were purchased from ACMEC biochemical (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals and organic solvents were of analytical grade and purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Beijing, China).

2.2. Construction of Gene Encoding scFv against Artemether

Total RNA was extracted from 5 × 106 hybridoma cells (2G12E1) using Thermo Scientific GeneJET RNA Purification Kit. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Thermo Scientific RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. The VH and VL genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using established antibody-specific primers, and the PCR products were cloned into the pMD™19-T vector. After transforming E. coli DH5α cells, the plasmid insert was directly screened from E. coli colonies. The plasmids in about 30 positive colonies were purified and sequenced by AZENTA Company (Suzhou, Jiangsu province, China). The genes encoding VH and VL domains were assembled and linked together by overlapping extension-PCR (SOE-PCR) to yield a full-length scFv gene with a VH-linker-VL format, with the linker being a standard 15 amino acid peptide (Gly4Ser)3. Then, the scFv gene was subcloned into the expression vectors pET32a (+), pET22b (+), pGEX-2T, and pMAL-p5x, respectively. The resulting constructs, which directed the synthesis of the recombinant anti-artemether scFvs with different tags, were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells.

2.3. Expression of Recombinant scFv against Artemether

Cells harboring each construct were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth medium (1 L) containing 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin and 2 g L−1 glucose. When the optical density of the culture at 600 nm reached 0.6, isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) (0.5 mM) was added to the culture to induce recombinant protein expression. After incubation at 37 °C for 12 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation, re-suspended in 100 mL of buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 7.4), and lysed by the repeated freeze-thaw method. The lysate was disrupted by sonication and then centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 min. The soluble fractions of the scFv-MBP fusion proteins were applied to a column (22.5 mm × 101 mm) containing Dextrin Beads (Smart-Lifesciences, Jiangsu, China). The other sorbents were not used due to insolubility of scFv samples fused with His tag and glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag. The recombinant antibody was purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, the purity of recombinant scFv was verified by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis and western blotting.

The scFv samples were mixed with 6 × SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and boiled for 15 min. Then all the proteins were detected by 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Blue Staining Solution (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The bands were electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane at 15 V for 25 min after separated by SDS-PAGE. The membrane was immersed in 5% non-fat milk in TBST (0.02 M Tris-HCl, 137 mM NaCl and 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, pH 7.6) for 2 h at room temperature. Next, the membrane was incubated with 0.17 μg mL−1 anti-MBP mouse mAb for scFv with MBP tag (1 μg mL−1 anti-His-tag mouse mAb for scFv with His tag and 0.25 μg mL−1 anti-GST tag mouse mAb for scFv with GST tag) for 12 hours at 4 °C. After that, the strip was incubated with 0.1 μg mL−1 Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG for 1 hour at room temperature. Then, the strip was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate Kit (Biosharp, Hefei, China) and the signal was analyzed using the Sapphire RGBNIR biomolecular imaging system (Azure Biosystems, Inc, USA).

2.4. Antigen Binding Assay of scFv by indirect ELISA

Indirect ELISA (iELISA) was used to verify the binding ability between artemether and the purified scFv. First, 100 μL of 0.25 μg mL−1 9-hydroxyartemether-BSA was coated on the plate for 3 h. The plate wells were washed with PBST (0.01 M PBS containing 0.1% tween-20, pH 7.4) three times and then incubated with 100 μL of various concentrations of scFv for 0.5 h. After washing the plate three times with PBST, 100 μL of 0.17 μg mL−1 anti-MBP mouse mAb for scFv with MBP tag (1 μg mL−1 anti-His-tag mouse mAb for scFv with His tag and 0.25 μg mL−1 anti-GST tag mouse mAb for scFv with GST tag) was added to the wells and incubated for 0.5 h. After rinsing, 100 μL of 0.1 μg mL−1 Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG was added to the wells and incubated for 0.5 h. After another washing step, 100 μL of 1.4 mM TMB substrate was added to each well, and the reaction was stopped with 50 μL of 1 M HCl. The optical densities at 450 nm (OD450) were recorded with a BioTek Synergy Neo2 microplate reader (BioTek, USA). All reactions were carried out at 37 °C.

2.5. Measurement of scFv Affinity by SPR

The binding affinity of the purified soluble anti-artemether scFv was measured using a Biacore 8000 system (GE Healthcare). Samples were prepared with the HBS-EP buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 3 mM EDTA). 9-hydroxyartemether-BSA and BSA standard were separately immobilized on the CM5 chip (GE Healthcare Bioscience) surface (flow cell 2 and 1). The antibody was diluted with HBS-EP buffer to the corresponding concentration and allowed to flow through the immobilized chip for 90 s with a flow rate of 30 μL min−1. The antibody was bound to 9-hydroxyartemether-BSA and then dissociated for 600 s. The chip surface was regenerated between binding cycles by injecting 10 mM glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.0) at 10 μL min−1 for 30 s. The sensorgram obtained for BSA was applied to remove the interference by nonspecific binding and bulk signal of the solvent. Data were analyzed using Biacore™ insight evaluation software with a 1:1 fit model.

2.6. Development of Indirect Competitive ELISA Based on scFv

The procedure of icELISA was the same as the iELISA described above, except that the addition of scFv was supplemented with an equal volume of artemether standard or analytes. The specificity of the scFv was evaluated by cross-reactivity with artemisinin and its derivatives utilizing icELISA.

2.7. Sample Extraction

Tablets of artemether (20 mg/tablet) were pulverized with a pestle, and 10 mL acetonitrile was added. Artemether capsule (40 mg/capsule) was diluted to 4 mg mL−1 using acetonitrile. The samples were then extracted by ultrasonication for 30 min. The supernatants were collected as the final extract and stored at −20 °C before analysis. For the bulk pharmaceutical chemicals (BPC) samples, the sample extracts were diluted into 2 mg mL−1 with acetonitrile as stock solutions for ELISA and ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) analyses based on the labeled content. Each sample was analyzed in triplicates.

2.8. UPLC Analysis of Artemether

Standards and samples were analyzed by UPLC according to the procedure of Chinese Pharmacopoeia [28]. The UPLC system consisted of a Waters Quaternary Solvent delivery system and a Waters PDA eλ detector (Singapore). A C18 reverse-phase column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm particle size; Waters, Ireland; Lot No. 0349392881) was used to separate artemether. The mobile phase, standards, and sample extracts obtained above were filtered through a 0.22-μm filter prior to UPLC. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and water (70/30, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The UV absorption was detected at 210 nm. The injection volume was 10 μL. All data were collected and analyzed by Waters Millennium 32 software.

2.9. Data Analysis

The data of icELISA and HPLC were analyzed by paired t-test and Bland-Altman method.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cloning and Sequencing of cDNAs Encoding scFv Against Artemether

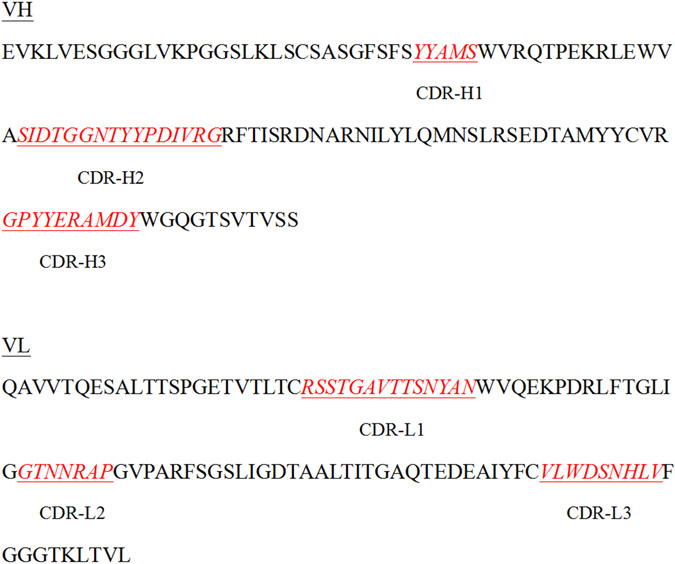

The VH and VL fragment genes were amplified from the mAb 2G12E1 cDNA, and were 354 bp and 327 bp, respectively. And the VL gene was a rare lambda light chain. The CDR, as shown in Fig. 2, was analyzed using the Kabat and Chothia numbering scheme (http://www.bioinf.org.uk/abs) and IMGT (http://www.imgt.org/IMGT_vquest/input). The closest V-genes and alleles for the VH domain are Musmus IGHV5–9*04 [F] (identity, 92.28%), and for Vλ are Musmus IGLV1*01 F (identity, 97.92%). The lengths of three CDRs of VH and Vλ by Kabat are 5-16-10 and 14-7-9, respectively. Compared with the closest germline sequences, there are 4 and 6 amino acid substitutions in CDRs and framework regions of VH, while these are 2 and 2 of Vλ, respectively. For VH, CDR1 and CDR2 have one (S36>Y) and five amino acid substitutions (S57>D, S58>T, S64>N, S70>I, and K72>R), respectively. For CDRs of Vλ, all the two amino acid substitutions occurred in CDR3 (A105>V and Y108>D). The Vλ is more conservative than VH. The result indicated that VH might contribute more to recognizing antigens than Vλ. Similar conclusions were also reached in other studies [26, 29]. The scFv sAFH-3e3 with amino acid mutations in FR1 and CDR1 of the VH chain showed a 7.5-fold improvement in sensitivity over the original scFv clone [26]. Two “designed” site-directed mutagenesis (A and B) targeting the N-terminal 1–10 positions of the VH FR1 successfully improved an anti-cortisol scFv (Ka, 3.6 × 108 M −1) [30]. The scFv mutants showed 17–31-fold increased affinity with > 109 M−1 Ka values [30].

Fig. 2.

Deduced amino acid sequences of VH and VL regions of anti-artemether antibody

After the sequence analysis of VH and VL, the two genes were assembled by SOE-PCR to construct a gene encoding scFv, with a full length of 726 bp, encoding 242 amino acids.

3.2. Bacterial Expression and Purification of scFv Against Artemether

ScFv does not exist naturally as single entities but associates with each other to make a functional unit. Recombinant scFv produced in E. coli is typically insoluble due to their foreign nature, high expression rate, and lack of disulfide bonds in the reducing environment of the cytoplasm, which requires solubilization and refolding processes to make it functional [20, 31, 32]. In the present study, the assembled scFv gene was inserted into pET32a (+), pET22b (+), pGEX-2T, and pMAL-p5x vectors, which were transformed into E. coli for the production of the recombinant scFv. SDS-PAGE and ELISA analysis demonstrated that the scFv produced from the pMAL-p5x/scFv vector was present in the soluble fraction, whereas the scFv produced with the pET32a (+), pET22b (+) and pGEX-2T vectors were primarily present in inclusion bodies (data not shown). The MBP tag within the pMAL-p5x/scFv could improve the solubility of the fused scFv. The result was consistent with the observations by Sun et al. [21], who found that the scFvs fused with either N utilization substance protein A or MBP showed higher solubility than those fused with signal peptides or thioredoxin, whereas the removal of these tags led to the aggregation of the expressed scFvs. Park et al. [23] also found that MBP tags can be employed to enhance the soluble expression of immunotoxins in E. coli.

With the construct pMAL-p5x/scFv, the recombinant scFv showed a molecular mass of ~72 kDa (Fig. 3A), which agreed with the predicted size of scFv with the tags. The scFv with an N-terminal MBP tag expressed in the soluble fraction was purified by affinity chromatography using the Dextrin Beads (Fig. 3B) and was further confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Protein expression analysis (A), protein purification (B) and western blotting (C) further confirmed expression of anti-artemether scFv. (A) Lane 1, empty plasmid (pMAL-p5x) before induction; Lane 2, empty plasmid (pMAL-p5x) after induction; Lane 3, the supernatant of recombinant E. coli culture before induction; Lane 4, supernatant of recombinant E. coli culture after induction; Lane 5, total protein from recombinant E. coli before induction; Lane 6, total protein from recombinant E. coli after induction; M, Protein marker. (B) M, Protein marker; Lane 1-4, eluted protein samples. (C) Lane 1, empty plasmid (pMAL-p5x) after induction; Lane 2, total protein from recombinant E. coli after induction; Lane 3, eluted protein sample

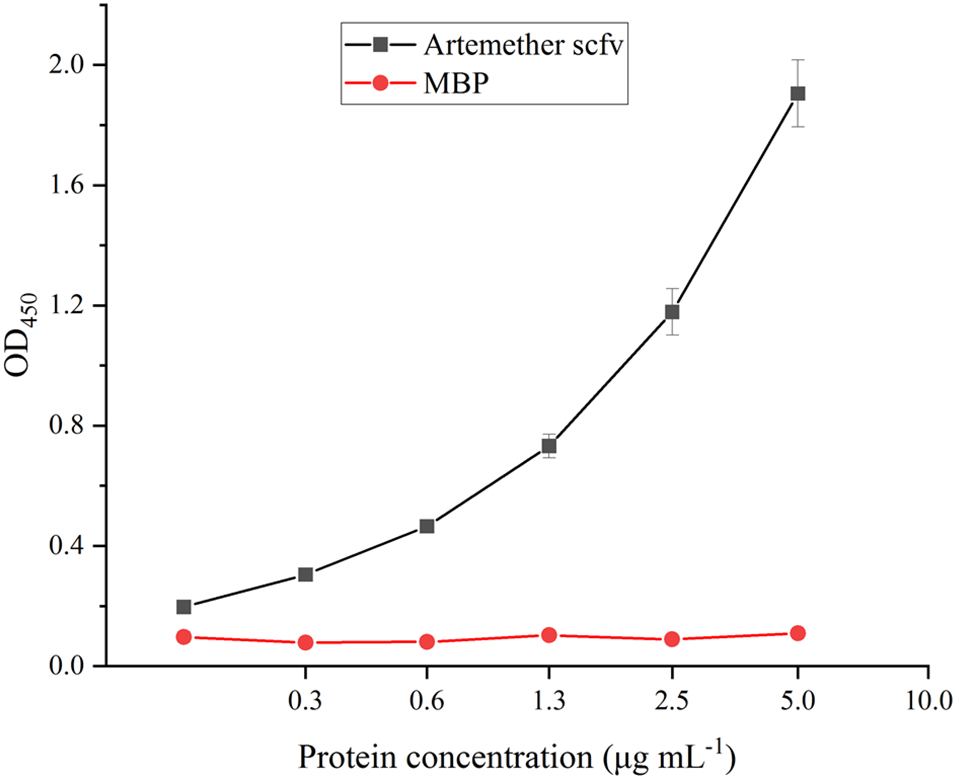

3.3. Antigen Binding Activity of the scFv Against Artemether

The antigen-binding activity of the purified scFv was measured by iELISA. The result indicated that the scFv recognized the artemether hapten-BSA conjugate, and the OD increased in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4). The scFv provided a high signal intensity of OD450 >1.0 at 2.5 μg mL−1 with the antigen 9-hydroxyartemether-BSA, while the the negative control MBP provided a very low signal intensity of OD450 ≤ 0.1 at 0–5 μg mL−1 with the antigen. The MBP tag did not specifically bind to the coating antigen. The result indicated that the scFv showed a high affinity toward the antigen and could be used to develop an ELISA.

Fig. 4.

Binding activity of anti-artemether scFv to the antigen 9-hydroxyartemether-BSA

3.4. Affinity of the scFv Against Artemether

The binding affinity of the purified soluble anti-artemether scFv was tested using a label-free SPR system. 9-hydroxyartemether-BSA was coupled to the CM5 sensor chip. Recombinant antibody dose-dependent binding was observed in the 9-hydroxyartemether-BSA coated channel, with an association rate constant (ka) of 2.18 × 104 M−1 s−1, a dissociation rate constant (kd) of 4.15 × 10−4 s−1, and affinity (KD) of 1.90 × 10−8 M (Fig. 5). These results indicated that anti-artemether scFv exhibited strong artemether-binding affinity and stability.

Fig. 5.

Binding kinetics of the anti-artemether scFv measured by SPR

Soluble expression of the scFv can increase the affinity of the protein. The binding activity of insoluble scFv protein without the pelB leader was much lower than the soluble scFv protein with the pelB leader [22]. Expression plasmids including highly hydrophilic tags such as MBP can improve the solubility and activities of fused scFvs because the tags have a chaperone-like activity that can prevent or significantly diminish scFv inclusion body formation [20, 21]. The high affinity of artemether scFv conforms to the previous conclusions that MBP can improve the solubility and activities of fused scFvs.

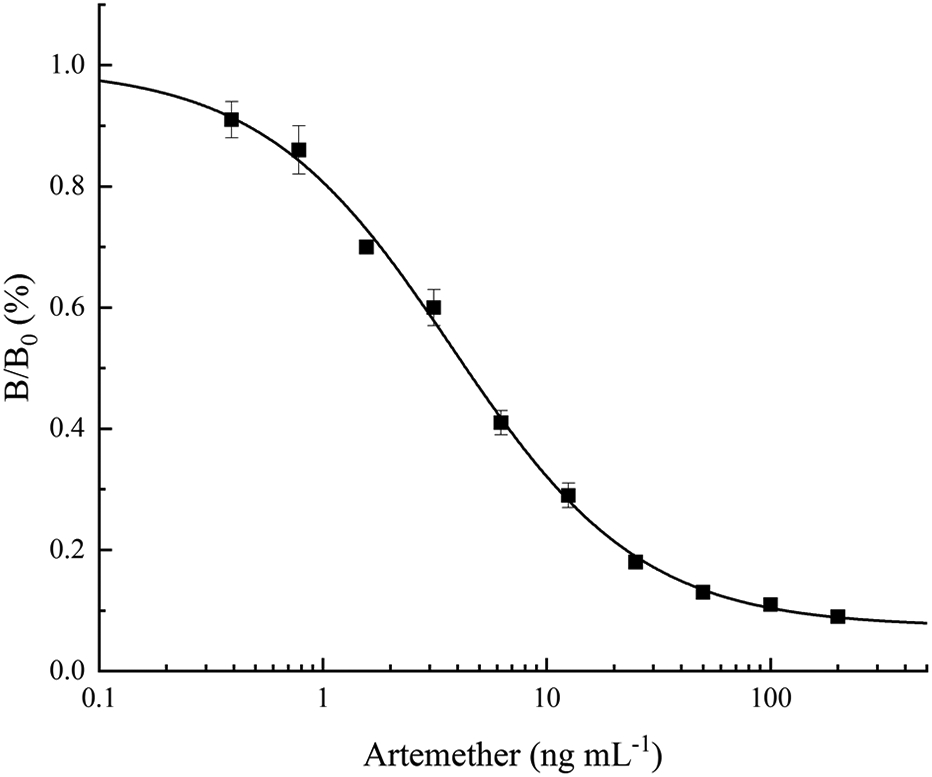

3.5. Standard Curves of icELISA based on the scFv Against Artemether

The optimal concentrations of coating antigen and scFv were screened by checkerboard titration. A standard inhibition curve for artemether was established by icELISA under the optimized conditions (Fig. 6). The IC50 value and the working range based on 20% to 80% inhibition were 4.33 ng mL−1 and 1.05–22.65 ng mL−1, respectively. The IC50 value of the icELISA was similar to that of the parental mAb 2G12E1 (3.7 ng mL−1) [11]. Paudel et al. [27] reported an scFv and a Fab against artemisinin and artesunate, but the scFv could not be used in an ELISA even at 30 μg mL−1. The IC50 values of the Fab-based icELISA were 1580 ng mL−1 for artemisinin and 22 ng mL−1 for artesunate. The sensitivity of the scFv and Fab was lower than mAb 3H2, which had IC50 values 1.29 ng mL−1 for artemisinin and 0.2 ng mL−1 for artesunate [10]. The sensitivity of scFvs without directed evolution and modification in vitro was usually less than those of mAbs or pAbs. Table 2 compares the analytical parameters of the scFv and ELISA in this paper with other reported immunoassays. The sensitivity of the scFv against artemether in this study was consistent with its parent mAb.

Fig. 6.

Standard inhibition curve of artemether in icELISA format. B0 and B are absorbance in the absence and presence of competitors, respectively. Concentration causing 50% inhibition by artemether was 4.33 ng mL−1. Each value represents the mean of three replicates

Table 2.

Comparison of different immunoassays for the determination of artemisinin analogsa

| Type of assay |

Hapten | Type of antibody |

Analytical parameters | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working range (ng mL−1) |

LOD (ng mL−1) |

Cross-reactivity | Analyzed matrices |

||||

| Radioimmunoassy |

|

Anti-artemisinin pAb | — | 2–3 | Artemisinin (100%), Artemether (100%), Dihydroartemisinin (100%), Artesunate (100%) | Plasma of dogs | [6] |

| ELISA |

|

Anti-artemisinin pAb | — | 1.5 | Artemisinin (100%), Dihydroartemisinin (High cross-reactivity) | Artemisia annua | [7] |

| ELISA |

|

Anti-artelinic acid mAb | — | — | Artemisinin (3–5%), Artemether (3–5%), Dihydroartemisinin (0.3–0.5%), Artesunate (<3–5%) | Urine | [8] |

| ELISA |

|

Anti-artemisinin mAb | 2000–20000 for artemisinin, 4–125 for artesunate | 2000 for artemisinin, 4 for artesunate | Artemisinin (100%), Dihydroartemisinin (29.9%), Artesunate (630%) | Artemisia annua | [9] |

| ELISA |

|

Anti-artemisinin mAb | 0.5–5.8 | 0.5 | Artemisinin (100%), Artemether (3%), Dihydroartemisinin (57%), Artesunate (650%) | Artemisia annua | [10] |

| ELISA |

|

Anti-artemether mAb | 0.7–19 | 0.7 | Artemisinin (2.3%), Artemether (100%), Dihydroartemisinin (1.3%), Artesunate (0) | Antimalarial drugs | [11] |

| ELISA |

|

Anti-artemisinin Fab | 160–40000 for artemisinin, 8–60 for artesunate | 160 for artemisinin, 8 for artesunate | Artemisinin (100%), Artesunate (7182%) | Artemisia plants | [27] |

| ELISA |

|

Anti-artemisinin mAb | 0.6–11.5 | 0.6 | Artemisinin (100%), Artemether (0), Dihydroartemisinin (0), Artesunate (0) | Artemisia annua and rat serum | [33] |

| ELISA and dipstick immunoassay |

|

Anti-artesunate mAb | 1.6-30.8 (ELISA), 1000-2000 (dipstick immunoassay) | 1.6 (ELISA), 1000-2000 (dipstick immunoassay) | Artemisinin (4.0%), Artemether (0.9%), Dihydroartemisinin (0.5%), Artesunate (100%) | Antimalarial drugs | [34] |

| ELISA and dipstick immunoassay |

|

Anti-dihydroartemisinin mAb | 0.26-4.87 (ELISA), 50–100 (dipstick immunoassay) | 0.18 (ELISA), 50–100 (dipstick immunoassay) | Artemisinin (52.3%), Artemether (<0.02%), Dihydroartemisinin (100%), Artesunate (1.6%) | Culture medium and antimalarial drugs | [35] |

| ELISA |

|

Anti-artemether scFv | 1.05–22.65 | 1.05 | Artemisinin (1.47%), Artemether (100%), Dihydroartemisinin (0.75%), Artesunate (<0.03%) | Antimalarial drugs | This work |

LOD: limit of detection; Ref.: reference; —: data not show

The cross-reactivity of the scFv was tested using artesunate, dihydroartemisinin, and artemisinin in icELISA (Table 1). The scFv showed low cross-reactivity with dihydroartemisinin (0.75%), artemisinin (1.47%), and artesunate (<0.03%). In comparison, the cross reactivity of mAb 2G12E1 with dihydroartemisinin, artemisinin, and artesunate was approximately 1.3%, 2.3%, and 0 (IC50 > 20,000 ng mL−1), respectively. The improved affinity of the scFv with artesunate may be due to the different three-dimensional structures of scFv and mAb. Our team has developed four other mAbs showing different specificities to artemisinin and its derivatives in previous studies [10, 33-35]. These mAb-producing cell lines will also be sequenced and studied on the relationship between protein structure and function of the scFv.

Table 1.

Cross reactivities of the icELISA with artemisinin and its derivatives

| Analytes | IC50 (ng mL−1) | Cross-reactivitya (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Artemether | 4.33 ± 0.23b | 100 ± 5.2 |

| Artemisinin | 294.80 ± 31.83 | 1.47 ± 0.15 |

| Dihydroartemisinin | 579.21 ± 37.59 | 0.75 ± 0.05 |

| Artesunate | >20000 | <0.03 |

Cross-reactivity (%)=(IC50 of artemether/IC50 of other compound) × 100

Data represent means of triplicate ± SD

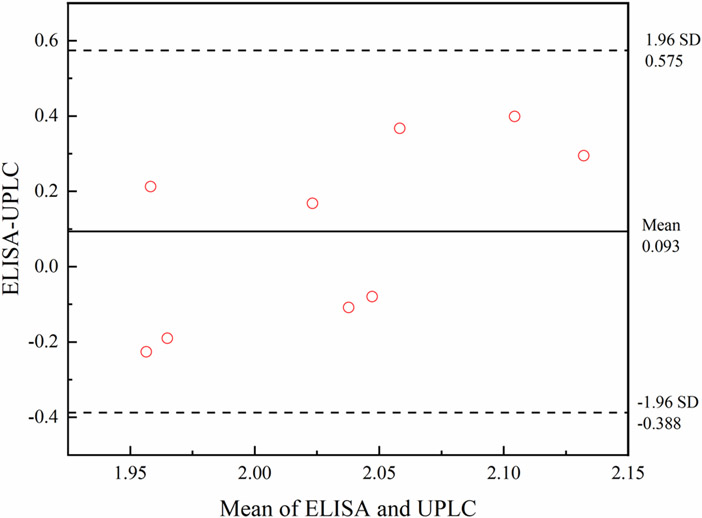

3.6. Comparative Analysis of Artemether Samples with icELISA and UPLC

We further evaluated the scFv-based icELISA for the analysis of nine artemether drugs and compared it with the UPLC (Table 3). The results of the icELISA and UPLC were compared by the paired t-test for accuracy at a 95% confidence level for eight degrees of freedom (T=1.133, P=0.290 > 0.05), which indicated no significant difference between the two methods in terms of accuracy. Data from these two assays were further analyzed by Bland-Altman bias plot combined with calculation of bias and 95% limits of agreement with 95% confidence intervals (Fig. 7). The mean bias ±1.96 standard deviations were between 0.575 and −0.388 ng mL−1. Thus, both statistical procedures suggested that the results from the two methods were comparable, and the icELISA method could be used to accurately quantify artemether and artemether drug quality control in field settings.

Table 3.

Comparison between ELISA and UPLC results for the quantitation of artemether in commercial drugs and bulk pharmaceutical chemicals (BPC)

| Drug namesa | SM/DCb | Lot no. | Purchased Region |

ELISA resultsc (mg/ml) |

UPLC resultsc (mg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARTEM | SM: Kunming Pharmaceutical Co., China | 120224 | Unknown, Myanmar | 2.24 ± 0.11 | 1.87 ± 0.01 |

| ARTEL+ | DC: Poly Gold Company | 1501AA2398 (Myanmar Reg. No) | Belin, Myanmar | 2.11 ± 0.14 | 1.94 ± 0.03 |

| ARTEL+ | DC: Poly Gold Company | 1501AA2398 (Myanmar Reg. No) | Pinleibu, Myanmar | 2.28 ± 0.03 | 1.98 ± 0.02 |

| SUPA ARTE | DC: AA Medical Products Ltd., Vietnam | 1501AA2398 (Myanmar Reg. No) | Kyankin, Myanmar | 2.06 ± 0.09 | 1.85 ± 0.01 |

| ARTEL+ | DC: Poly Gold Company | 1501AA2398 (Myanmar Reg. No) | Kyankin, Myanmar | 2.30 ± 0.05 | 1.90 ± 0.00 |

| Artemether (≥98.0%) | SM: Shanghai D&B Biological and Technology Co. Ltd, China | KK02 | Online | 1.87 ± 0.19 | 2.06 ± 0.08 |

| Artemether (≥98.0%) | SM: Shanghai Xianding Biological and Technology Co. Ltd, China | PAEVYDM | Online | 1.98 ± 0.14 | 2.09 ± 0.07 |

| Artemether (≥98.0%) | SM: Saen Chemical Co. Ltd, China | RXR8RAE4 | Online | 2.01 ± 0.21 | 2.09 ± 0.02 |

| Artemether (≥98.0%) | SM: Zhengzhou Acme Chemical Co. Ltd, China | ACME13503 | Online | 1.84 ± 0.06 | 2.07 ± 0.03 |

Each sample was analyzed in triplicate

SM: Stated Manufacturer. DC: Distributing Company

Data represent mean ± SD. The theoretical content of all drugs was 2 mg mL−1

Fig. 7.

Bland-Altman bias plots for ELISA and UPLC. Quantitating artemether drugs concentration expressed as mg mL−1. The solid line represents the bias between the assays, and the dashed lines represent the bias ± 1.96-s limits

4. Conclusion

In this study, we cloned the VH and VL genes of a cell line (mAb 2G12E1) producing a monoclonal antibody specific to artemether, and used to construct a recombinant DNA of scFv. The DNA was constructed into pMAL-p5x vector to express soluble scFv with comparable sensitivity and specificity to that of mAb 2G12E1, and an icELISA was developed based on the scFv. We further evaluated the scFv-based icELISA for the analysis of artemether drugs and compared it with the UPLC. The results indicated that the recombinant produced in this study scFv can be used for artemether drug quality control in field settings.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900677), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Jiangmen (2021030102590004834) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (U19AI089672).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Fang Lu: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing– original draft, Visualization; Fa Zhang: Methodology, Validation, Investigation; Jingqi Qian: Validation, Investigation, Resources; Tingting Huang: Validation, Investigation; Liping Chen: Validation, Investigation; Yilin Huang: Validation, Investigation; Baomin Wang: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition; Liwang Cui: Writing – Review & Editing; Suqin Guo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration; Funding acquisition.

References

- [1].World Health Organization, world malaria report 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040496, 2021. (Accessed 29 March 2022).

- [2].World Health Organization, WHO Guidelines for malaria. https://app.magicapp.org/#/guideline/j9QMBj/section/nBMKdz, 2022. (Accessed 29 March 2022).

- [3].World Health Organization, Report on antimalarial drug efficacy, resistance and response: 10 years of surveillance (2010–2019). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240012813, 2020. (Accessed 29 March 2022).

- [4].Ozawa S, Evans DR, Bessias S, Haynie DG, Yemeke TT, Laing SK, Herrington JE, Prevalence and estimated economic burden of substandard and falsified medicines in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis, JAMA Netw. Open 1 (2018) e181662–e181662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lamy MCM, Framing the challenge of poor-quality medicines: problem definition and policy making in Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2017. DOI: 10.17037/PUBS.04645490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Song Z, Zhao K, Liang X, Liu C, Yi M, Radioimmunoassay of qinghaosu and artesunate, Acta Pharm. Sin 20 (1985) 610–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ferreira JF, Janick J, Immunoquantitative analysis of artemisinin from Artemisia annua using polyclonal antibodies, Phytochemistry 41 (1996) 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Eggelte T, Van Agtmael M, Vuong T, Van Boxtel C, The development of an immunoassay for the detection of artemisinin compounds in urine, Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 61 (1999) 449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tanaka H, Putalun W, De-Eknamkul W, Matangkasombut O, Shoyama Y, Preparation of a novel monoclonal antibody against the antimalarial drugs, artemisinin and artesunate, Planta Med. 73 (2007) 1127–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].He SP, Tan GY, Li G, Tan WM, Nan TG, Wang BM, Li ZH, Li QX, Development of a sensitive monoclonalantibody-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the antimalaria active ingredient artemisinin in the Chinese herb Artemisia annua L, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 393 (2009) 1297–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Guo S, Cui Y, He L, Zhang L, Cao Z, Zhang W, Zhang R, Tan G, Wang B, Cui L, Development of a specific monoclonal antibody-based ELISA to measure the artemether content of antimalarial drugs, PloS One 8 (2013) e79154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bates A, Power CA, David vs. Goliath, The Structure, Function, and Clinical Prospects of Antibody Fragments, Antibodies 8 (2019) 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang Z, Wen K, Zhang X, Li X, Wang Z, Shen J, Ding S, New hapten synthesis, antibody production, and indirect competitive enzyme-linked immnunosorbent assay for amantadine in chicken muscle, Food Anal. Methods 11 (2018) 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Xie S, Wang J, Yu X, Peng T, Yao K, Wang S, Liang D, Ke Y, Wang Z, Jiang H, Site-directed mutations of anti-amantadine scFv antibody by molecular dynamics simulation: prediction and validation, J. Mol. Model 26 (2020) 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liu Y, Liu D, Shen C, Dong S, Hu X, Lin M, Zhang X, Xu C, Zhong J, Xie Y, Construction and characterization of a class-specific single-chain variable fragment against pyrethroid metabolites, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 104 (2020) 7345–7354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shan G, Huang H, Stoutamire DW, Gee SJ, Leng G, Hammock BD, A sensitive class specific immunoassay for the detection of pyrethroid metabolites in human urine, Chem. Res. Toxicol 17 (2004) 218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chen J, Jiang J, Monoclonal antibody-based solvent tolerable indirect competitive ELISA for monitoring ciprofloxacin residue in poultry samples, Food Agric. Immunol 24 (2013) 331–344. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang F, Li N, Zhang Y, Sun X, Hu M, Zhao Y, Fan J, Preparation and Directed Evolution of Anti-Ciprofloxacin ScFv for Immunoassay in Animal-Derived Food, Foods 10 (2021) 1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Andersen DC, Reilly DE, Production technologies for monoclonal antibodies and their fragments, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 15 (2004) 456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Arbabi-Ghahroudi M, Tanha J, MacKenzie R, Prokaryotic expression of antibodies, Cancer Metastasis Rev. 24 (2005) 501–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sun W, Xie J, Lin H, Mi S, Li Z, Hua F, Hu Z, A combined strategy improves the solubility of aggregation-prone single-chain variable fragment antibodies, Protein Expr. Purif 83 (2012) 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chen W, Wu J, Chen W, Hu P, Wang X, An approach to achieve highly soluble bioactive ScFv antibody against staphylococcal enterotoxin A in E.coli with pelB leader, IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci 512 (2020) 012077 (012077pp). [Google Scholar]

- [23].Park S, Nguyen MQ, Ta H, Nguyen MT, Han C, Soluble Cytoplasmic Expression and Purification of Immunotoxin HER2(scFv)-PE24B as a Maltose Binding Protein Fusion, Int. J. Mol. Sci 22 (2021) 6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li L, Hou R, Shen W, Chen Y, Wu S, Wang Y, Wang X, Yuan Z, Peng D, Development of a monoclonal-based ic-ELISA for the determination of kitasamycin in animal tissues and simulation studying its molecular recognition mechanism, Food Chem. 363 (2021) 129465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Frota NF, de Sousa Rebouças A, Fuzo CA, Lourenzoni MR, Alemtuzumab scFv fragments and CD52 interaction study through molecular dynamics simulation and binding free energy, J. Mol. Graph. Model 107 (2021) 107949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rangnoi K, Choowongkomon K, O’Kennedy R, Rüker F, Yamabhai M, Enhancement and analysis of human antiaflatoxin b1 (AFB1) scFv antibody–ligand interaction using chain shuffling, J. Agric. Food Chem 66 (2018) 5713–5722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Paudel MK, Takei A, Sakoda J, Juengwatanatrakul T, Sasaki-Tabata K, Putalun W, Shoyama Y, Tanaka H, Morimoto S, Preparation of a single-chain variable fragment and a recombinant antigen-binding fragment against the anti-malarial drugs, artemisinin and artesunate, and their application in an ELISA, Anal. Chem 84 (2012) 2002–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2020, Beijing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [29].López-Requena A, Rodríguez M, de Acosta CM, Moreno E, Puchades Y, González M, Talavera A, Valle A, Hernández T, Vázquez AM, Gangliosides, Ab1 and Ab2 antibodies: II. Light versus heavy chain: An idiotype-anti-idiotype case study, Mol. Immunol 44 (2007) 1015–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kiguchi Y, Oyama H, Morita I, Nagata Y, Umezawa N, Kobayashi N, The VH framework region 1 as a target of efficient mutagenesis for generating a variety of affinity-matured scFv mutants, Sci. Rep 11 (2021) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Barkhordari F, Sohrabi N, Davami F, Mahboudi F, Garoosi YT, Cloning, expression and characterization of a HER2-alpha luffin fusion protein in Escherichia coli, Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol 49 (2019) 759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dong S, He K, Guan L, Shi Q, Wu J, Feng J, Yang W, Shi X, Construction and Characterization of a Single-Chain Variable Fragment (scFv) for the Detection of Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac Toxins from the Anti-Cry1Ab Monoclonal Antibody, Food Anal. Methods 15 (2022) 1321–1330. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Guo S, Cui Y, Wang K, Zhang W, Tan G, Wang B, Cui L, Development of a specific monoclonal antibody for the quantification of artemisinin in Artemisia annua and rat serum, Anal. Chem 88 (2016) 2701–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guo S, Zhang W, He L, Tan G, Min M, Kyaw MP, Wang B, Cui L, Rapid evaluation of artesunate quality with a specific monoclonal antibody-based lateral flow dipstick, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 408 (2016) 6003–6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ning X, Li W, Wang M, Guo S, Tan G, Wang B, Cui L, Development of monoclonal antibody-based immunoassays for quantification and rapid assessment of dihydroartemisinin contents in antimalarial drugs, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 159 (2018) 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]