ABSTRACT

CUO246, a novel DNA gyrase/topoisomerase IV inhibitor, is active in vitro against a broad range of Gram-positive, fastidious Gram-negative, and atypical bacterial pathogens and retains activity against quinolone-resistant strains in circulation. The frequency of selection for single step mutants of wild-type S. aureus with reduced susceptibility to CUO246 was <4.64 × 10−9 at 4× and 8× MIC and remained low when using an isogenic QRDR mutant (<5.24 × 10−9 at 4× and 8× MIC). Biochemical assays indicated that CUO246 had potent inhibitory activity against both DNA gyrase (GyrAB) and topoisomerase IV (ParCE). Furthermore, CUO246 showed rapid bactericidal activity in time-kill assays and potent in vivo efficacy against S. aureus in a neutropenic murine thigh infection model. These results suggest that CUO246 may be useful in treating infections by various causative agents of acute skin and skin structure infections, respiratory tract infections, and sexually transmitted infections.

KEYWORDS: CUO246, DNA gyrase, in vitro activity, in vivo efficacy, topoisomerase IV

INTRODUCTION

Antibiotic resistance in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria has become an increasingly serious problem for health care systems worldwide. Previously effective treatments are now compromised by the emergence of resistance, urgently necessitating the development of new drugs. An important class of clinically used antibiotics are the fluoroquinolones, which block DNA replication in bacteria by dual inhibition of the type II topoisomerases gyrase and topoisomerase IV (1, 2). Bacterial topoisomerases mediate changes in DNA topology (e.g., relaxing supercoils) and belong to either the type I or type II class. Type I topoisomerases catalyze transient breakage of one strand of double-stranded DNA, whereas type II topoisomerases catalyze breaks in both strands and can introduce negative supercoils (3). Gyrase and topoisomerase IV are the only type II enzymes in bacteria and play essential nonredundant roles in maintaining DNA integrity. Furthermore, while DNA topoisomerases are generally conserved in bacteria, there are substantial differences between the bacterial enzymes and topoisomerase II enzymes of higher eukaryotes (3–5), reflecting differences in chromosome structure between bacterial (haploid) and mammalian (diploid) cells. Functionally, all type II enzymes exhibit multiple activities, including DNA binding and DNA double-strand cleavage and reunion. In the case of bacteria, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV are composed of two subunits that combine to form a heterotetrameric complex (gyrase, A2B2; Topo IV, C2E2) (6). In general, A subunits are associated with DNA binding and cleavage activities while the B subunit harbors an ATPase active site. In contrast, eukaryotic topoisomerases are single subunit enzymes that operate as homodimers. Because of these differences, fluoroquinolones target prokaryotic topoisomerase enzymes at concentrations 100- to 1,000-fold lower than mammalian enzymes (7). Fluoroquinolones target both gyrase and topoisomerase IV in bacteria, but topoisomerase IV is the primary target in Gram-positive and DNA gyrase is the primary target in Gram-negative (4). The clinical success of the fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics provides strong validation of gyrase and topoisomerase IV as antibacterial targets. However, and despite the dual targeting of two essential enzymes by the fluoroquinolones, clinical resistance has ultimately emerged via mechanisms decreasing intracellular concentration of the inhibitor or through mutational alterations of target enzymes (2). Substantial fluoroquinolone resistance occurs through the accumulation of target mutations encoding amino acid substitutions in both the gyrase and topoisomerase IV proteins. Such genes are commonly called gyrA and gyrB, and parC and parE, respectively. In Staphylococcus aureus, they are referred to as grlA and grlB (2). Regions within these proteins that are now well characterized as being important sites for resistance development are referred to as quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDR).

Fluoroquinolones are widely used for treating a range of infectious diseases, but in some hospitals, the increasing level of resistance led to avoidance of this class of compounds as first line treatment. A large proportion of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates are now resistant to fluoroquinolones, although methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) remain more susceptible (8–10). S. aureus is among the leading causes of hospital-acquired infections, as well as a cause of serious community-acquired infections (11), including acute skin and skin structure infections and numerous invasive pathologies (12–14). Resistance to fluoroquinolones has been reported for Streptococcus pneumoniae, a major pathogen of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), in various areas of the world (15, 16). CAP can also be caused by various fastidious and atypical Gram-negative bacteria. Haemophilus influenzae is the most commonly identified Gram-negative agent of CAP, followed by Enterobacteriaceae, Legionella pneumophila (the causative agent of Legionnaires’ Disease), Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydophila pneumoniae. While vaccines are available for the most common causes of bacterial pneumonia, S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae type b, the etiologic agent in CAP infection is only determined for 30 to 50% of patients, necessitating the need for a therapy that covers all possible causes (17). Among pathogens causing sexually transmitted diseases, high variations in fluoroquinolone resistance rates are observed. The more alarming reports concern Neisseria gonorrhoeae, with values ranging from 10% in the United States to 60% in Europe and more than 90% in Asia (18). N. gonorrhoeae is responsible for hundreds of thousands of sexually transmitted infections every year and is the second most reported notifiable disease in the United States. Untreated infection can lead to serious complications, including loss of fertility in women, as well as increased HIV transmission rates. In 2007, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that fluoroquinolones no longer be used to treat N. gonorrhoeae infections (19) and recommended against treatment with cefixime and tetracycline in 2012 (20).

This scenario has prompted ongoing interest in the identification of novel inhibitors to exploit the well-validated gyrase and topisomerase IV antibacterial targets that are not as impacted by the typical resistance mutations emerging in the clinic. Along with the small molecule fluoroquinolone class of inhibitors are several other chemical entities, including natural products (aminocoumarins [chlorobiocin and coumermycin], simocyclinone, and cyclothialidines) and large toxins (CcdB and microcin B17), which all have potent antibacterial activity by virtue of their inhibition of type II DNA topoisomerases (21, 22). The 2-aminoquinazolinedione (23), the isothiazoloquinolone (24), the spiropyrimidinetrione (25), and the novel tricyclic topoisomerase inhibitor (NTTI) (26) classes are examples of antibacterial discovery based on exploiting novel binding interactions between new chemical ligands and the target enzymes in order to bypass mutations associated with quinolone resistance. Furthermore, the novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitor (NBTI) type compounds retain potency against fluoroquinolone-resistant (FQR) isolates by binding to a site that is distinct from, but adjacent to, the catalytic center of DNA gyrase/topoisomerase IV, which is occupied by the quinolones (27).

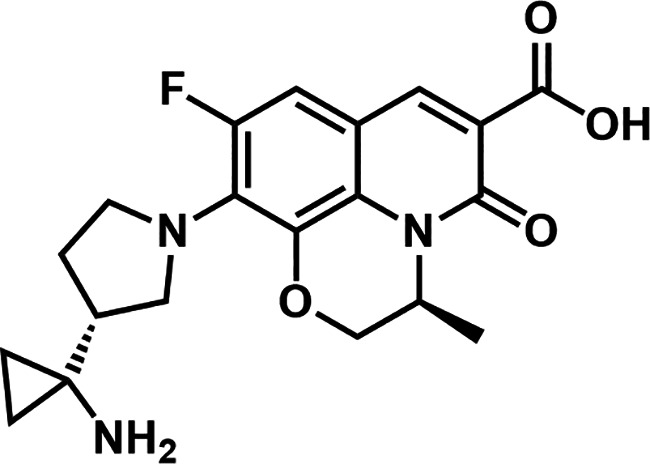

This study describes the in vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity of CUO246, a novel DNA gyrase/topoisomerase IV inhibitor (Fig. 1). We previously reported the discovery of a novel series of antibacterial agents characterized by a quinolin-2 (1H)-one scaffold. This series was identified using a scaffold morphing approach inspired by a phenotypic hit and incorporating features of both fluoroquinolones and Pfizer’s quinazolinediones (28). Subsequent optimization culminated in CUO246 (Fig. 1), which exhibited promising activity against fluoroquinolone-resistant Gram-positive bacteria. CUO246, like other compounds in this series, inhibits bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV by binding to, and stabilizing, DNA cleavage complexes (29).

FIG 1.

Chemical structure of CUO246.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Inhibition of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV by CUO246.

The amount of supercoiled DNA generated in Escherichia coli and S. aureus gyrase (GyrAB) reactions and the decatenated or nicked kinetoplast DNA produced in E. coli topoisomerase (ParCE) or human topoisomerase II alpha reactions were measured using size exclusion chromatography (described in supplemental methods). CUO246 showed good inhibitory activity against DNA gyrase from E. coli (IC50 3.51 μM) and S. aureus (5.75 μM) and against E. coli bacterial topoisomerase IV (8.18 μM) (Table 1). Ciprofloxacin, delafloxacin and moxifloxacin were more potent against E. coli gyrase than CUO246; however, activity against S. aureus gyrase was similar between CUO246, and delafloxacin, with both being more potent than moxifloxacin. Interestingly, CUO246 activity against E. coli gyrase and topoisomerase IV was slightly more balanced (about 2.3-fold different) than ciprofloxacin (5.5-fold), delafloxacin (about 3.8-fold) or moxifloxacin (6.1-fold). This suggests that CUO246 may also exhibit fairly even dual targeting against the S. aureus topoisomerases. Importantly, CUO246 had good in vitro selectivity against human topoisomerase II, with an IC50 of >250 μM.

TABLE 1.

Inhibitory activity of CUO246 against DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV and human topoisomerase IIa

| Agent | IC50 (μM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli GyrAB |

E. coli ParCE |

S. aureus GyrAB | Human topoisomerase II alpha | |

| CUO246 | 3.51 ± 0.47 | 8.18 ± 1.07 | 5.75 ± 3.73 | >250 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.49 ± 0.17 | 2.71 ± 0.32 | ND | >250b |

| Delafloxacin | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.53 ± 0.21 | 4.55 ± 1.80 | >250 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 2.07 ± 0.56 | 15.38 ± 0.58 | >250 |

Results expressed as the geometric mean ± SEM from 3–5 experimental results.

Ciprofloxacin was used as the assay control in this assay (38).

In vitro susceptibility.

The activity of CUO246 was evaluated against a large set of characterized reference isolates from various bacterial species (Table 2). When tested against aerobic Gram-positive strains, CUO246 MIC values ranged from ≤0.03 to 1 μg/mL. CUO246 was active against the Gram-positive anaerobes Clostridioides difficile and Propionibacterium acnes with MICs of 1 and 4 μg/mL, respectively. CUO246 was active against the Enterobacteriaceae strains tested with MIC values ranging from 1 to 4 μg/mL. Among nonfermenting Gram-negative organisms, CUO246 possessed reduced activity, with MIC values between 8 and >32 μg/mL. However, CUO246 had potent activity against various strains of fastidious Gram-negative species (MIC range, 0.12 to 1 μg/mL) and Gram-negative anaerobic strains (MIC range, 0.25 to 2 μg/mL). CUO246 had MIC values of 16 and 8 μg/mL against the acid-fast strains Mycobacterium peregrinum and Mycobacterium smegmatis, respectively.

TABLE 2.

In vitro spectrum of activity of CUO246a

| Organism | Strain | MIC (μg/mL) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUO246 | MXF | NOR | VAN | TET | SXT | CLI | CAZ | MEM | TZP | ||

| Gram-positive aerobic bacteria | |||||||||||

| Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC 29212 | 1 | 0.25 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 0.06 | – | – | – | – |

| Enterococcus faecium | ATCC 6569 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.06 | – | – | – | – |

| Lactobacillus casei | ATCC 15008 | ≤0.03 | 0.03 | 1 | >32 | 0.12 | 0.12 | – | – | – | – |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC 29213 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.12 | – | – | – | – |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | ATCC 12228 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 1 | 64 | 0.5 | – | – | – | – |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | ATCC 13813 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 4 | 0.25 | ≤0.06 | 0.25 | – | – | – | – |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | ATCC 49619 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.5 | – | – | – | – |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | ATCC 8058 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | – | – | – | – |

| Gram-positive anaerobic bacteria | |||||||||||

| Clostridioides difficile | ATCC 700057 | 1 | 2 | – | 1 | – | – | 8 | – | 1 | – |

| Propionibacterium acnes | ATCC 6919 | 4 | 0.5 | – | 0.5 | – | – | ≤0.12 | – | 0.06 | – |

| Enterobacteriaceae | |||||||||||

| Enterobacter cloacae | ATCC 13047 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.06 | – | 1 | >4 | – | 16 | 0.06 | – |

| Escherichia coli | ATCC 25922 | 2 | 0.015 | ≤0.03 | – | 0.5 | 0.25 | – | 0.5 | 0.03 | – |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | ATCC 13048 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.06 | – | 1 | 0.5 | – | 0.5 | 0.06 | – |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 43816 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | – | 1 | 2 | – | 0.5 | 0.06 | – |

| Morganella morganii | ATCC 25830 | 1 | 0.06 | ≤0.03 | – | 0.5 | 0.5 | – | ≤0.015 | 0.06 | – |

| Proteus mirabilis | ATCC 29906 | 4 | 0.5 | ≤0.03 | – | 32 | 0.25 | – | 0.06 | 0.12 | – |

| Providencia alcalifaciens | ATCC 9886 | 4 | 0.5 | ≤0.03 | – | 1 | 0.25 | – | 0.06 | 0.06 | – |

| Salmonella enterica | ATCC 15782 | 4 | 0.06 | ≤0.03 | – | 1 | 0.25 | – | 0.25 | 0.03 | – |

| Serratia marcescens | ATCC 13880 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.12 | – | 32 | 1 | – | 0.25 | 0.06 | – |

| Shigella flexneri | ATCC 29903 | 1 | 0.03 | ≤0.03 | – | 0.25 | 1 | – | 0.12 | 0.03 | – |

| Nonfermenting Gram-negative bacteria | |||||||||||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | ATCC 19606 | 8 | 0.5 | 16 | – | 2 | – | – | 16 | 2 | – |

| Burkholderia cepacia | ATCC BAA-245 | >32 | >4 | 32 | – | 64 | – | – | >16 | >16 | – |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 | 32 | 2 | 1 | – | 16 | – | – | 2 | 0.5 | – |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | ATCC 13637 | 8 | 0.06 | – | – | – | – | – | 8 | >16 | – |

| Atypical and fastidious Gram-negative bacteria | |||||||||||

| Campylobacter fetus | ATCC 33293 | 1 | 0.03 | 2 | – | 0.25 | – | – | >16 | ≤0.015 | – |

| Haemophilus influenzae | ATCC 49247 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.06 | – | 8 | – | – | 0.5 | 0.5 | – |

| Helicobacter pylori | ATCC 43504 | 0.25 | 0.25 | – | – | 0.25 | – | – | 4 | ≤0.015 | – |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | ATCC 25240 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.12 | – | 0.12 | – | – | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | – |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | ATCC 49226 | 0.12 | 0.008 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.12 | ≤0.03 | – |

| Vibrio cholerae | IEM101 | 0.5 | 0.03 | ≤0.03 | – | 0.12 | – | – | 0.12 | 0.25 | – |

| Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria | |||||||||||

| Bacteroides fragilis | ATCC 25285 | 0.5 | 0.25 | – | – | – | – | – | >16 | 0.12 | 0.25/4 |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | ATCC 29741 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | >16 | 0.12 | 16/4 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | ATCC 25586 | 0.25 | ≤0.12 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | ≤0.015 | – |

| Prevotella melaninogenica | ATCC 25845 | 2 | 0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 0.12 | – |

| Acid-fast bacteria | |||||||||||

| Mycobacterium peregrinum | ATCC 700686 | 16 | 0.25 | 4 | >32 | 1 | 0.03 | – | – | – | – |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis | ATCC 19420 | 8 | 0.06 | 8 | 32 | 0.12 | 0.03 | – | – | – | – |

MXF, moxifloxacin; NOR, norfloxacin; VAN, vancomycin; TET, tetracycline; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; CLI, clindamycin; CAZ, ceftazidime; MEM, meropenem; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; -, not determine.

Further characterization of CUO246 in vitro activity against recent clinical isolates is summarized in Table 3. CUO246 was found to have activity against 40 S. aureus isolates with MIC values that ranged from 0.12 to 4 μg/mL. MIC50 and MIC90 values were 0.5 μg/mL and 2 μg/mL, respectively. CUO246 MIC90 values for methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates were 1 and 2 μg/mL, respectively. There was an 8-fold difference between MIC90 values for fluoroquinolone-susceptible (MIC90, 0.5 μg/mL; N = 20, 8 MSSA and 12 MRSA) and fluoroquinolone-resistant (MIC90, 4 μg/mL; N = 20, 2 MSSA and 18 MRSA) isolates. However, the marketed fluoroquinolones tested for comparison (ciprofloxacin, delafloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin) were at least 64-fold less active against the fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates compared to the fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates tested. Therefore, CUO246 appeared less impacted by the range of resistance mutations currently found in the clinic than the comparator fluoroquinolones. Consistent with the shifts described above, CUO246 was only ≤2-fold less active against isogenic S. aureus mutants encoding single characterized quinolone resistance determining region (QRDR) substitutions (GyrA S84L, GrlA S80Y, GrlA S80F or GrlA E84L), or the double substitution GyrA S84L/GrlA E84L (Table 4). The 2-fold shift associated with GyrA S84L alone (NB01001-DLR0024) was increased to 4-fold shift when combined with a GrlA S80F or a GrlA S80Y mutation (NB01001-DLR0056 and NB01001-DLR0060, respectively). Moxifloxacin showed a similar loss of potency (2- to 4-fold) against the mutants encoding these single substitutions but exhibited a 32-fold shift against the mutants with the double substitutions. Norfloxacin potency was shifted ≥16-fold against three of the mutants with single substitutions and 64- to 128-fold against mutants with double substitutions. While isogenic mutants encoding the double substitution GyrA S84L/GrlA S80F or GyrA S84L/GrlA S80Y were 4-fold less susceptible to CUO246, they were 32-fold and ≥64-fold less susceptible to moxifloxacin and norfloxacin, respectively.

TABLE 3.

In vitro activity of CUO246 and comparators antimicrobial agents against Gram-positive and Gram-negative isolates

| Microorganism (N) and test agent |

MIC (μg/mL) |

% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | Susceptiblea | |

| S. aureus (40) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.12–4 | 0.5 | 2 | NAb |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12–>32 | 1 | 32 | 50.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.03–>32 | 0.25 | 8 | 50.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25–>32 | 4 | >32 | 47.5 |

| Delafloxacin | ≤0.004–4 | 0.008 | 0.5 | 85.0 |

| Linezolid | 1–4 | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5–4 | 1 | 1 | 97.5 |

| MSSA isolates (10) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.12–4 | 0.25 | 1 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12–32 | 0.25 | 4 | 80.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.03–8 | 0.06 | 2 | 90.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25–>32 | 0.5 | 16 | 90.0 |

| Delafloxacin | ≤0.004–0.25 | ≤0.004 | 0.12 | 100 |

| Linezolid | 2–4 | 2 | 4 | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5−1 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| MRSA isolates (30) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.25–4 | 1 | 2 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12–>32 | 4 | >32 | 40.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.03–>32 | 2 | 8 | 40.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25–>32 | 16 | >32 | 36.7 |

| Delafloxacin | ≤0.004–4 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 80.0 |

| Linezolid | 1–4 | 2 | 4 | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5–4 | 1 | 1 | 96.7 |

| CoNS (10)c | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.25–4 | 0.5 | 4 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25–>8 | 1 | >8 | 50.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.06–>32 | 0.25 | 16 | 50.0 |

| Delafloxacin | ≤0.004–4 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 80.0 |

| Azithromycin | 1–>32 | >32 | >32 | 10.0 |

| Linezolid | 0.5−16 | 1 | 2 | 90.0 |

| Vancomycin | 1–2 | 1 | 2 | 100 |

| E. faecalis (15) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.5–8 | 2 | 8 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5–>8 | 1 | >8 | 60.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.12–32 | 0.25 | 16 | NA |

| Delafloxacin | 0.03–1 | 0.06 | 1 | 60.0 |

| Azithromycin | 2–>32 | >32 | >32 | NA |

| Linezolid | 1–16 | 2 | 16 | 86.7 |

| Vancomycin | 1–>32 | 2 | >32 | 66.7 |

| E. faecium (12) | ||||

| CUO246 | 8–32 | 16 | 32 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | >8 | >8 | >8 | 0.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | 16–32 | 32 | 32 | NA |

| Delafloxacin | >4 | >4 | >4 | 0.0 |

| Azithromycin | 0.5–>32 | >32 | >32 | NA |

| Linezolid | 1–32 | 4 | 32 | 33.3 |

| Vancomycin | 16–>32 | >32 | >32 | 0.0 |

| S. pneumoniae (20)d | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.06–1 | 0.5 | 1 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 1–>16 | >16 | >16 | 35.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.06–4 | 2 | 4 | 35.0 |

| Delafloxacin | 0.008–1 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 35.0 |

| Azithromycin | 0.03–>16 | >16 | >16 | 15.0 |

| Linezolid | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 0.12−0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 100 |

| S. pyogenes (7) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.06–0.12 | 0.12 | –e | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5–4 | 1 | – | 85.7 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.06–0.25 | 0.12 | – | 100 |

| Delafloxacin | ≤0.004–0.015 | 0.008 | – | 100 |

| Azithromycin | 0.06–8 | 0.12 | – | 71.4 |

| Linezolid | 1 | 1 | – | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | – | 100 |

| S. agalactiae (7) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.12–0.5 | 0.25 | – | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 2–4 | 2 | – | 71.4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 | – | 100 |

| Delafloxacin | 0.008–0.015 | 0.015 | – | 100 |

| Azithromycin | 0.03–>16 | 0.06 | – | 85.7 |

| Linezolid | 1–2 | 1 | – | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5−1 | 1 | – | 100 |

| Viridans group (6) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.25−1 | 0.25 | – | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 2–>16 | 2 | – | 50.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.06–8 | 0.25 | – | 83.3 |

| Delafloxacin | 0.008–0.25 | 0.015 | – | 83.3 |

| Azithromycin | 0.06–>16 | 0.25 | – | 50.0 |

| Linezolid | 0.25−1 | 0.5 | – | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 0.25–1 | 0.5 | – | 100 |

| E. coli (12) | ||||

| CUO246 | 2−32 | 16 | 32 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.03–>4 | >4 | >4 | 18.2 |

| Ciproloxacin | 0.008–>4 | >4 | >4 | 18.2 |

| Delafloxacin | 0.015–4 | 2 | 4 | 18.2 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25–>32 | 2 | >32 | 63.6 |

| Gentamicin | 0.25–>16 | 0.5 | >16 | 54.5 |

| Meropenem | 0.03–>16 | 0.06 | 16 | 63.6 |

| Tigecycline | 0.25−1 | 0.25 | 1 | 100 |

| K. pneumoniae (15) | ||||

| CUO246 | 2–>32 | 32 | >32 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12–>4 | >4 | >4 | 40.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.03–>4 | >4 | >4 | 26.7 |

| Delafloxacin | 0.03–>4 | 2 | >4 | 20.0 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.5–>32 | >32 | >32 | 20.0 |

| Gentamicin | 0.12–>16 | 8 | >16 | 40.0 |

| Meropenem | 0.06–>16 | 4 | >16 | 46.7 |

| Tigecycline | 0.5–>4 | 1 | 4 | 86.7 |

| H. influenzae (25) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.25–4 | 0.5 | 1 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | ≤0.008−0.06 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 100 |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.03−0.25 | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | 100 |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | 0.12/0.06–4/2 | 0.25/0.12 | 2/1 | 100 |

| Ampicillin | 0.12–32 | 0.25 | 32 | 73.9 |

| Azithromycin | 0.25–>32 | 4 | >32 | 69.6 |

| Cefuroxime | 0.25–4 | 0.5 | 4 | 100 |

| Tetracycline | 0.5–32 | 0.5 | 1 | 95.7 |

| M. catarrhalis (22) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.5–2 | 2 | 2 | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.015−0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 100 |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.03–0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | NA |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | ≤0.03/0.015–0.5/0.25 | 0.12/0.06 | 0.25/0.12 | 100 |

| Ampicillin | ≤0.03–16 | 2 | 16 | NA |

| Azithromycin | ≤0.03–0.12 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | 100 |

| Cefuroxime | 0.25–4 | 1 | 2 | 100 |

| Tetracycline | 0.12–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 100 |

| N. gonorrhoeae (25) | ||||

| CUO246 | ≤0.06–1 | 0.25 | 1 | NA |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.004–>1 | >1 | >1 | 24.0 |

| Azithromycin | ≤0.12–>8 | 0.25 | 4 | NA |

| Cefriaxone | ≤0.002–2 | 0.015 | 0.5 | 88.0 |

| Penicillin G | 0.06–>2 | 2 | >2 | 4.0 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.12–>8 | 2 | >8 | 4.0 |

| L. pneumophila (4) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.25 | 0.25 | – | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.015–0.03 | 0.015 | – | NA |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.03 | 0.03 | – | NA |

| Azithromycin | 0.06 | 0.06 | – | NA |

| Erythromycin | 0.12–0.25 | 0.25 | – | NA |

| Clarithromycin | 0.015–0.03 | 0.015 | – | NA |

| Doxycycline | 2−8 | 8 | – | NA |

| M. pneumoniae (4) | ||||

| CUO246 | 0.25−0.5 | 0.5 | – | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25–0.5 | 0.25 | – | 100 |

| Moxifloxacinf | 0.03 | 0.03 | – | 100 |

| Azithromycin | 0.002–0.004 | 0.002 | – | 100 |

| Erythromycin | 0.015–0.03 | 0.015 | – | 100 |

| Clarithromycinf | 0.008 | 0.008 | – | NA |

| Doxycyclinef | 0.004–0.008 | 0.004 | – | NA |

| C. pneumoniae (1) | ||||

| CUO246 | 1 | – | – | NA |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | – | – | – |

| Azithromycin | 0.015 | – | – | – |

| Clarithromycin | 0.004 | – | – | – |

| Doxycycline | 0.03 | – | – | – |

Susceptibility as defined by CLSI document M100 (39). In the absence of CLSI breakpoints, USA-FDA breakpoints were applied (40).

NA, not applicable. Susceptibility has not been defined for CUO246.

Strains tested include S. epidermidis (3), S. capitis (1), S. haemolyticus (1), S. hominis (2), S. saprophyticus (1), S. simulans (1), and S. warneri (1).

Out of the 20 strains tested, 9 were non-susceptible to PenG when tested by TREK Sensititer Microdilution Plate (STP6F).

MIC90 values were not calculated when N <10 isolates.

N = 3 strains tested.

TABLE 4.

In vitro activity of CUO246 against an isogenic panel of S. aureus QRDR mutantsa

| S. aureus mutants | Relevant characteristic | MIC (μg/mL) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUO246 | MOX | NOR | ||

| Parent (ATCC 29213) | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 | |

| NB01001-DLR0024 | GyrA S84L (TCA→TTA) | 0.5 | 0.12 | 1 |

| NB01001-DLR0027 | GrlA S80Y (TCC→TAC) | 0.25 | 0.12 | 16 |

| NB01001-DLR0028 | GrlA S80F (TCC→TTC) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 16 |

| NB01001-DLR0133 | GrlA E84L (GAA→AAA) | 0.25 | 0.12 | 32 |

| NB01001-DLR0056 | GyrA S84L (TCA→TTA), GrlA S80F (TCC→TTC) | 1 | 2 | 128 |

| NB01001-DLR0060 | GyrA S84L (TCA→TTA), GrlA S80Y (TCC→TAC) | 1 | 2 | 64 |

| NB01001-DLR0064 | GyrA S84L (TCA→TTA), GrlA E84L (GAA→AAA) | 0.25 | 2 | 64 |

MOX, moxifloxacin; NOR, norfloxacin.

CUO246 MIC50/90 values against 10 coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) clinical isolates were 0.5/4 μg/mL, with MIC values ranging between 0.25 and 4 μg/mL (Table 2). All isolates were methicillin-resistant and 5 were fluoroquinolone-resistant. The MIC50/90 values of CUO246 against 15 E. faecalis stains were 2/8 μg/mL with MIC values ranging between 0.5 and 8 μg/mL, and the MIC50/90 values for CUO246 against 12 E. faecium isolates were 16/32 μg/mL with MIC values ranging between 8 and 32 μg/mL. All E. faecium isolates were fluoroquinolone-resistant and vancomycin-intermediate or -resistant. CUO246 showed good activity against isolates of E. casseliflavus (MIC 2 μg/mL), E. flavescens (MIC 0.5 μg/mL), and E. gallinarum (MIC 0.5 μg/mL). The MIC50/90 values of CUO246 against 40 streptococci, which included 20 S. pneumoniae, 7 S. pyogenes, 7 S. agalactiae, and 6 viridans group streptococci isolates, were 0.25/0.5 μg/mL with MIC values ranging between 0.06 and 1 μg/mL. CUO246 MIC50/90 values against the 20 S. pneumoniae isolates, 13 of which were fluoroquinolone-resistant, were 0.5/1 μg/mL, with MIC values ranging from 0.06 to1 μg/mL. While CUO246 had potent activity against the Enterobacteriaceae ATCC reference strains tested, it had limited activity against the majority of the clinical isolates tested. The MIC50/90 for E. coli isolates (N = 12) was 16/32 μg/mL and the MIC50/90 for K. pneumoniae isolates (N = 15) was 32/>32 μg/mL. Against other Enterobacteriaceae isolates tested, which included C. freundii (N = 3), K. aerogenes (N = 2), and E. cloacae (N = 3), CUO246 had an MIC50 of 32 μg/mL. Fluoroquinolone-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae isolates were more sensitive to inhibition by CUO246 (N = 10; MIC50/90 of 8/16 μg/mL) than fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates (N = 25; MIC50/90 of 32/>32 μg/mL). When tested against fastidious Gram-negative isolates, CUO246 had activity against H. influenzae (N = 25), with an MIC50 of 0.5 μg/mL and an MIC90 of 1 μg/mL. The MIC50/90 values of CUO246 against M. catarrhalis (N = 22) was 2/2 μg/mL. No fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates of H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis were tested in this study as clinical incidence for fluoroquinolone-resistance is still generally low for these species (30). CUO246 was tested against twenty-five isolates of N. gonorrhoeae from various geographic regions, including a World Health Organization (WHO) surveillance panel comprised of 14 isolates (31). CUO246 had activity against N. gonorrhoeae (N = 25), with an MIC50 of 0.25 μg/mL and an MIC90 of 1 μg/mL. When comparing its potency against ciprofloxacin-susceptible (N = 6; MIC50, 0.12 μg/mL), ciprofloxacin-intermediate (N = 2; MIC50, 0.5 μg/mL), and ciprofloxacin-resistant (N = 17; MIC50, 0.25 μg/mL) isolates, the activity of CUO246 was relatively unaffected by ciprofloxacin susceptibility in N. gonorrhoeae. Against three ceftriaxone-resistant isolates, CUO246 MIC values ranged between 0.5 and 1 μg/mL (the isolates were ciprofloxacin-resistant and azithromycin-susceptible). The MIC range of CUO246 against nine atypical Gram-negative isolates was 0.25 to 1 μg/mL. The MIC50 values of CUO246 against Legionella pneumophila (N = 4) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (N = 4) isolates were 0.25 μg/mL and 0.5 μg/mL, respectively. CUO246 was tested against a single strain of Chlamydophila pneumoniae and the MIC was 1 μg/mL. All atypical isolates evaluated in this study were fluoroquinolone-susceptible, as resistance is rare in the clinic.

Effect of test parameter variation on in vitro activity of CUO246.

Alterations to inoculum preparation, incubation atmosphere, media preparation, or media composition did not substantively change CUO246 MIC values. The only condition that increased CUO246 MIC values by 4-fold for two of the four strains tested was a prolonged incubation time up to 48 h (Supplemental result Table R1). When tested under the same conditions, minimal effects (≤2-fold) were observed on the activity of moxifloxacin (data not shown).

In vitro selection of mutants with decreased susceptibility to CUO246.

Single-step mutant selection was performed using S. aureus ATCC 29213 and a quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) mutant (NB01001-DLR0056, selected on 8 μg/mL of norfloxacin) expressing GyrA S84L/GrlA S80F variants. The frequency of selecting S. aureus ATCC29213 mutants on CUO246 ranged from 2.37 × 10−9 at 2× MIC to <4.64 × 10−9 at 4× and 8× MIC (Table 5). Mutants selected at 2× MIC were less susceptible to CUO246, but the MIC of CUO246 against these mutants did not exceed 1 μg/mL (data not shown). The mutant frequency was similarly low for S. aureus NB01001-DLR0056 selected on CUO246 (8.39 × 10−9 at 2× MIC and <5.24 × 10−9 at 4× and 8× MIC). This suggests that the presence of preexisting fluoroquinolone-selected QRDR mutations may not result in an increased propensity to select mutations decreasing susceptibility to CUO246. Starting from a first step mutant selected on CUO246 (NB01001-DRL0080, which was 4-fold less susceptible to CUO246 than its parent ATCC 29213 [Table 6]), a second round of selection on CUO246 was conducted yielding a mutant frequency of 1.76 × 10−9 at 2× MIC and <2.04 × 10−10 at 4× MIC. A third selection experiment using a mutant derived from the second step selection (NB01001-DRL0100) yielded mutants at a frequency of 5.53 × 10−9 at 2× MIC and <1.91 × 10−10 at 4× MIC. Mutants emerging after the third selection experiments were 64- to128-fold less susceptible to CUO246 (MIC values of 16 to 32 μg/mL for 14 selected mutants compared to 0.25 μg/mL for the parent strain, data not shown). All of these tested mutants displayed wild-type sensitivity to tetracycline and ethidium bromide, suggesting reduced susceptibility to CUO246 in these mutants did not involve efflux (32). Whole-genome sequencing revealed that the first step selection mutant NB01001-DLR0080 (Table 5) harbored gyrB and grlA mutations encoding GyrBE477G and GrlAR519C, respectively. The second step mutant derived from this first step mutant, NB01001-DRL0100 (Table 5), harbored an additional mutation in grlB encoding a GrlBE472A. A mutant derived from this second step mutant (NB01001-DLR0118) was sequenced and it was found to contain an additional gyrA mutation encoding GyrAS84L. The identification of these target mutations provides further evidence that CUO246 indeed targets gyrase and topoisomerase IV in S. aureus. This also suggests that substantial shifts in susceptibility to CUO246 can occur progressively via the accumulation of these target alterations, although each mutation appears to occur at a frequency of approximatively 1 × 10−9. Interestingly, the additional mutation selected during the third selection step did not further reduce susceptibility to moxifloxacin or norfloxacin over that of the second step mutant NB01001-DLR0100 (Table 6). In fact, susceptibility to these agents appears to have increased approximately 4-fold, consistent with differential target interaction between CUO246 and traditional fluoroquinolones. Additional studies will be required to determine the impact of each mutation individually and to better understand how they interact to alter susceptibility to CUO246 or fluoroquinolones.

TABLE 5.

Frequency of selection of mutant strains by selection with CUO246

| S. aureus strain used for | MIC (μg/mL) | Frequency at the following multiple of MIC |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2× MIC | 4× MIC | 8× MIC | ||

| First selection | ||||

| ATCC 29213 | 0.12 | 2.37 × 10−9 | <4.64 × 10−9 | <4.64 × 10−9 |

| NB01001-DLR0056a | 1 | 8.39 × 10−9 | <5.24 × 10−9 | <5.24 × 10−9 |

| Second selection | ||||

| NB01001-DLR0080b | 1 | 1.76 × 10−9 | <2.04 × 10−10 | ND |

| Third selection | ||||

| NB01001-DLR0100c | 4 | 5.53 × 10−9 | <1.91 × 10−10 | ND |

QRDR mutant encoding GyrA S84L/ GrlA S80F amino acid substitutions.

Isolated from parental strain ATCC 29213, selected on 0.25 μg/mL of CUO246.

Isolated from parental strain NB01001-DRL0080, selected on 2 μg/mL of CUO246.

TABLE 6.

In vitro activity of CUO246 against mutants selected on CUO246a

| S. aureus mutants | Selection | MIC (μg/mL) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUO246 | MOX | NOR | TET | Et Br | ||

| Parent (ATCC 29213) | Parental strain | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 |

| NB01001-DLR0080b | First selection | 1 | 0.06 | 2 | 05 | 2 |

| NB01001-DLR0100c | Second selection | 4 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 2 |

| NB01001-DLR0118d | Third selection | 16 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 |

MOX, moxifloxacin; NOR, norfloxacin; TET, tetracycline; Et Br, ethidium bromide.

Isolated from parental strain ATCC 29213, selected on 0.25 μg/mL of CUO246.

Isolated from parental strain NB01001-DRL0080, selected on 2 μg/mL of CUO246.

Isolated from parental strain NB01001-DRL0100, selected on 8 μg/mL of CUO246.

Bactericidal activity.

CUO246 achieved a 3-log10 reduction in the colony count within 24 h, without regrowth, against strains of MSSA (ATCC 29213), and MRSA (ATCC 33591, ATCC BAA-1717, NB01021, and NB01058) when the inoculum ranged between 5.6 and 6.6 log10 CFU (CFU)/mL. The minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) for these strains were 2-times the MICs (Table 7). The killing curves typically exhibited an initial rapid decrease within 2 to 4 h and a slower phase that resulted in sterilization of the culture within 24 h. Moxifloxacin and vancomycin were also bactericidal against the tested strains, while linezolid was bacteriostatic (data not shown).

TABLE 7.

MBCs determined by time-kill studies

|

S. aureus strain |

Inoculum (log10 CFU/mL) | MBC |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUO246 |

Moxifloxacin |

Vancomycin |

|||||

| μg/mL | xMIC | μg/mL | xMIC | μg/mL | xMIC | ||

| ATCC 29213 | 6.1 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 8 | 2 | 2 |

| ATCC 33591 | 5.6 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.12 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| ATCC BAA-1717 | 5.8 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| NB01021 | 6.3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | ND | ND |

| NB01058 | 6.6 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 2 | ND | ND |

In vivo efficacy in murine infection models.

The antibacterial efficacy of CUO246 was evaluated in vivo against infections caused by S. aureus isolates in the neutropenic murine thigh infection model. CUO246 was efficacious against clinically relevant strains, including fluoroquinolone-susceptible and fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates. CUO246 reduced bacterial load in a dose-dependent manner for all strains tested (Table 8). CUO246 static and 1-log10 kill doses ranged from 2.64 to 26.78 mg/kg/day and 4.23 to 45.98 mg/kg/day, respectively. While a 2-log10 kill doses of 8.49 and 23.98 mg/kg/day were calculated against S. aureus ATCC 29213 and NB01021 strains, a 2-log10 kill was not achieved against strain NB01058 for any dose tested. The moxifloxacin dose required for stasis was 5-fold higher than the dose required for CUO246 to achieve the same effect against S. aureus ATCC 29213 strain. Against that strain, moxifloxacin MIC (0.06 μg/mL) was 4-fold lower than CUO246 MIC (0.25 μg/mL) indicating that while its MIC values may be elevated in comparison with marketed fluoroquinolone agents, CUO246 has improved in vivo efficacy against fluoroquinolone-susceptible as well as against fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates. S. aureus NB01021 was used to assess the efficacy of CUO246 oral dosing. In thigh infection studies, CUO246 was similarly efficacious when given orally, with a static dose of 9.23 mg/kg/day and a 1-log10 kill dose of 11.91 mg/kg/day.

TABLE 8.

CUO246 efficacy in murine neutropenic thigh infection modela

| Efficacy against S. aureus isolates | Dose (mg/kg/day) required to achieve bacterial stasis, 1-log10 kill or 2-log10 kill against S. aureus isolates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent | ATCC 29213 | NB01021 | NB01058 | |

| CUO246 | Stasis | 2.64 | 11.34 | 26.78 |

| 1-log10 kill | 4.23 | 15.99 | 45.98 | |

| 2-log10 kill | 8.49 | 23.98 | NA | |

| MIC (μg/mL) | 0.25 | 1 | 4 | |

| Moxifloxacin | Stasis | 13.90 | - | - |

| 1-log10 kill | - | - | - | |

| 2-log10 kill | - | - | - | |

| MIC (μg/mL) | 0.06 | 2 | 8 | |

| Vancomycin | Stasis | - | 63.12 | 25.70 |

| 1-log10 kill | - | 73.73 | - | |

| 2-log10 kill | - | 83.24 | - | |

| MIC (μg/mL) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Linezolid | Stasis | - | 92.61 | 42.72 |

| 1-log10 kill | - | 131.67 | 44.76 | |

| 2-log10 kill | - | 269.96 | - | |

| MIC (μg/mL) | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

aEfficacy against S. aureus isolates in a neutropenic murine thigh infection model. Log10 CFU/thigh present in the thigh after 24 h of treatment. Treatment was administered subcutaneously every 24 h. Data are presented as mean, N = 4 animals per group. NA, not achieved. -, not determine.

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics of CUO246.

The efficacy of CUO246 was tested against S. aureus strains ATCC29213 and NB01058 in a mouse thigh infection model dose fractionation study (Table 9). For both strains, the static dose increased as the dosing interval decreased suggesting that fCmax/MIC might be contributing to efficacy. Assuming linear kinetics and incorporating the protein binding to determine free drug levels, PK parameters for the doses and schedules investigated in the efficacy study were determined in relation to the MIC to provide corresponding fAUC/MIC, fCmax/MIC and fT>MIC for each log10 CFU/thigh. Regression analysis showed that the parameter that best correlated with the efficacy of CUO246 against S. aureus ATCC 29213 was the fCmax/MIC (R2 = 86%) followed by fAUC/MIC (R2 = 73%). A similar analysis was also completed for strain NB01058. In this case, it was difficult to determine the dominant index with all 3 parameters appearing to equally contribute to efficacy with R2 values of 75%, 78% and 73% for fCmax/MIC, fAUC/MIC, and fT>MIC, respectively. Both the fAUC/MIC and the fCmax/MIC were analyzed further using an additional three strains of S. aureus and considering only Q24H dosing. The magnitude of each parameter required for stasis and 1-log10 reduction from stasis is shown in Table 10.

TABLE 9.

Static does of CUO246 in the murine thigh model of S. aureus infection

| Dosing | Static dose (mg/kg/day) |

|

|---|---|---|

| ATCC 29213 | NB01058 | |

| Q24H | 2.53 | 27.11 |

| Q12H | 3.54 | 33.44 |

| Q6H | 7.31 | 41.54 |

| Q3H | 9.36 | 69.81 |

TABLE 10.

Magnitude of fAUC/MIC and fCmax/MIC required for CUO246 to induced stasis and 1-log10 killing in the murine thigh model of S. aureus infection

| Strain | MICa (μg/mL) | fAUC/MIC (stasis) |

fAUC/MIC (1-log10 drop) |

fCmax/MIC (stasis) |

fCmax/MIC (1-log10 drop) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 29213 | 0.25 | 18.47 | 30.93 | 3.22 | 5.38 |

| NB01020 | 0.25 | 27.5 | 54.82 | 4.79 | 9.55 |

| NB01021 | 1 | 21.84 | 25.56 | 3.81 | 4.45 |

| NB01058 | 2 | 24.73 | 47.23 | 4.31 | 8.25 |

| NB01346 | 0.25 | 18.77 | NA | 3.28 | NA |

Results are representative of at least six independent experiments.

In summary, CUO246 has inhibitory activity against both DNA gyrase (GyrAB) and topoisomerase IV (ParCE) leading to potent in vitro activity against a broad panel of clinically relevant Gram-positive, fastidious Gram-negative and atypical pathogens, including fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates. These findings are consistent with data from a panel of isogenic strains expressing various QRDR mutations. CUO246 demonstrated efficacy in vivo, in a neutropenic murine thigh infection model, against S. aureus, including strains resistant to ciprofloxacin; the PK/PD driver for CUO246 efficacy in this model of infection was both fAUC/MIC and fCmax/MIC. Together, these in vitro and in vivo findings support the continued development of this new agent for the treatment of infections due to various causative agents of acute skin and skin structure infections, respiratory tract infections, and sexually transmitted infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimicrobial agents.

CUO246 was synthesized at Novartis (29). Amoxicillin, azithromycin, ceftazidime, cefuroxime, ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, clindamycin, linezolid, meropenem, penicillin G, piperacillin, sulfamethoxazole, and tazobactam were purchased from US Pharmacopeia (Rockville, MD). Ampicillin, ceftriaxone, clavulanate, doxycycline, erythromycin, gentamicin, levofloxacin, norfloxacin, tetracycline, trimethoprim, and vancomycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Daptomycin and tigecycline were obtained from SellkChem (Houston, TX), delafloxacin was obtained from MedChem Express (Monmouth Junction, NJ), and moxifloxacin was purchased from Sequoia Research Products (Pangbourne, UK).

Bacterial strains.

Clinical isolates used in these studies were obtained from various geographic locations and were from the Novartis collection. The isolates were acquired between 1987 and 2016. Reference strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Vibrio cholerae IEM101, an attenuated strain deficient in CTXΦ, was from the Novartis collection.

Inhibitory activity of CUO246 against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV and human topoisomerase II.

Protein purifications and biochemical assays using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) to measure the supercoiled DNA generated in gyrase reactions, and to measure the decatenated kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) generated in the topoisomerase IV reaction are described in supplemental materials (Methods M1 and M2). These SEC biochemical assays were validated using reference compounds, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and delafloxacin.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility testing was performed by broth microdilution and agar dilution methods as described in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (33–36) with the exception of Chlamydophila pneunoniae for which MICs were determined using automated fluorescence microscopy (Methods M3 described in supplemental materials).

Effect of serum, pulmonary surfactant and test parameter variations on in vitro activity.

Pooled human serum (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at final concentrations of 10% and 50% (vol/vol) while pulmonary surfactant (AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL) was added at final concentrations of 1% and 5% (vol/vol). Various in vitro test parameters were systematically evaluated in the MIC assay to determine their effect on the activity of CUO246. Results were compared to MIC tests using the standard reference method (testing media, CAMHB; inoculum, 5 × 105 CFU/mL; incubation conditions, ambient air at 35°C; pH 7.4; incubation time,16 to 20 h) (33).

Test media: Testing was performed in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB), cation-adjusted-MHB (CAMHB), and CAMHB supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood (LHB, Quad Five, Ryegate, MT). Fresh CAMHB was defined as media that was prepared on the day of testing. Modified acidity of CAMHB was tested at pH 6.4 and pH 8.4. Cations were adjusted by addition of 50 mg/L calcium. Salinity was adjusted by addition of 5% NaCl (vol/vol).

Incubation time, incubation conditions and inoculum: Microtiter plates were incubated at 35°C in ambient air for 16–20 and 48 h. Incubation was performed at 35°C with 5% CO2 or under microaerobic or anaerobic conditions. Variations to the inoculum preparation were implemented by testing low (5 × 104 CFU/mL) or high (5 × 106 CFU/mL) inoculum concentrations or by the use of a 48 h plate or of log-phase growth inoculum.

Selection of single step spontaneous mutants.

S. aureus isolates, including reference strain ATCC 29213 and an isolate with a QRDR mutant encoding GyrA S84L/GrlA S80F amino acid substitutions (NB01001-DLR0056) were used for selection experiments. For each bacterial strain, a concentrated cell suspension (target of ≥1010 CFU/mL) was prepared by growing overnight on three MHA plates and harvesting the cells from the entire surface of the plates using sterile cotton swabs. Cells were suspended in 3 mL of CAMHB/17% sterile glycerol and frozen at −80°C. The CFU/mL were then determined. Single-step selection was performed on plates containing test compounds at 2×, 4×, and 8× multiples of the MIC mode for each compound in duplicate. Dilutions of cell suspension were also plated on drug-free medium to enumerate CFU/mL. Plates were incubated overnight at 35°C for 24 h and CFU were counted. Mutant frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of colonies on drug containing plates by the number of CFU plated.

Bactericidal activity.

Time-kill experiments were performed following CLSI methodology (37) against five strains of S. aureus in CAMHB. Antibiotics were added to the culture media at concentrations equivalent to multiples of the MIC for each organism tested. Tubes were inoculated with early log-phase cultures of bacteria, which were diluted to yield a final cell density of 1 × 106 CFU/mL. The samples taken at this time constituted the 0-h time point. Cultures were then incubated at 35°C in ambient air with constant agitation using an orbital shaker (Innova 43, New Brunswick Scientific) for 24 h and were sampled at various times. Prior to each sampling, tubes were mixed carefully. Viable cell counts were determined by performing 10-fold serial dilutions in sterile saline; 0.1 mL of undiluted and diluted samples was applied directly on the Mueller-Hinton agar. Colonies were counted after 24 h incubation at 35°C in ambient air.

Animals.

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Inc. (Emeryville, CA, USA). Female CD-1 mice (17 to 20 g; Envigo, Livermore, CA, USA) were kept under controlled specific pathogen-free conditions with 12 h dark/12 h light cycles, 22°C constant temperature, 30% to 70% relative humidity with food and water ad libitum. Four animals were housed per cage in IVC Innovive disposable caging (Innovive, San Diego, CA, USA).

Inoculum preparation for animal studies.

For each bacterial strain, an overnight culture was prepared by inoculating 25 mL Mueller–Hinton Broth with 20 μL of bacterial strain from frozen stock. The culture was allowed to grow for 16 to 18 h at 37°C with agitation at 150 rpm (I2400 Incubator Shaker; New Brunswick Scientific). 10 mL of the overnight cultures were centrifuged at 2,330 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in 10 mL sterile saline. Using optical density: CFU correlations, the inoculum was prepared at 2 × 106 by diluting with sterile saline. To confirm titer, inoculum was diluted with sterile saline, plated on TSA plates and incubated overnight at 37°C for bacterial enumeration.

Neutropenic murine thigh infection.

Animals were rendered neutropenic by intraperitoneal injections of 150 and 100 mg/kg cyclophosphamide (Sigma-Aldrich), on days −4 and −1, respectively, prior to infection. Two hours prior to treatment (−2 h), 50 μL of bacterial, containing approximatively105 to 106 CFU, was administered into the left gastrocnemius muscle via an intramuscular injection. At time zero hour, animals were treated via the subcutaneous (sc) route of administration (5 mL/kg) in alternating left and right inguinal areas (we compared oral and sc dosing for CUO246 and similar CUO246 exposures were observed for oral and sc dosing, given the frequency of dosing required for comprehensive PK/PD analysis we selected sc route for technical reasons). Doses (2.5 to 80 mg/kg) were administered either as a single doses or fractionated into equal aliquots and time intervals. At 0 h a cohort of animals was sacrificed via CO2 to determine the bacterial levels at the start of treatment. The remaining animals were euthanized 24 h after the start of therapy. The infected thighs were excised and homogenized in sterile saline until the tissue was completely homogenized. The homogenates were serially diluted in sterile saline before dilutions were plated on TSA plates, incubated overnight at 37°C and the colonies counted. The CFU/thigh were calculated and transformed to log10. Data were analyzed in GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software).

Pharmacokinetic analysis and modeling.

Pharmacokinetic studies were performed in uninfected mice with drug concentrations determined by LC-MS/MS. All analysis was performed using Phoenix WinNonLin 6.4 to generate PK parameters. Plasma concentrations were corrected for protein binding (13%), as determined by rapid equilibrium dialysis, to calculate free drug levels. Mean plasma concentrations were fit using compartmental analysis followed by simulations of the dosing paradigm used in the study. The AUC was obtained from the measured plasma concentrations versus time using the trapezoidal method and extrapolated to 24 h.

Calculation of static dose.

The static dose (mg/kg/day) is that which is required to keep the bacterial load at the same level as when therapy was initiated. Dose/day was plotted against log10 CCFU and analyzed using a four parametric logistic curve (SigmaPlot 12.0; SyStat Software). The static dose was calculated using the following equation: log10 static dose = {Log10 (E/[Emax − E])/N} + log10 ED50, where E is the control growth (log10 change in CFU per thigh in untreated controls after the 24 h period of study), Emax is the maximum effect, ED50 is the dose required to achieve 50% of Emax, and N is the slope of the dose-effect curve. In addition, the dose required to achieve 1-log10 reduction below bacterial stasis was calculated (E + 1-log10).

PK/PD relationship.

Using free drug (f) levels, PK/PD relationships were determined by calculating the percentage of time that the free concentration of drug in the plasma was above the MIC (%fT>MIC), free peak plasma concentration (fCmax)/MIC, and fAUC/MIC and plotting them against log10 CFU. To determine the dominant parameter driving efficacy, the R2value from nonlinear regression analysis was used to show what percentage of the variation in CFU/thigh could be attributed to each PK/PD parameter. Regression analysis and the magnitude of the dominant PK/PD parameter for bacterial stasis and killing were determined using the same method as that for the static dose determination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bret M. Benton, Gianfranco De Pascale, Brian Feng, John Fuller, and Laura McDowell for their contribution to assay development for the automated fluorescence microscopy and bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV assessment. We thank Peter-Skewes-Cox and David Barkan for bioinformatics support and Lauren Chapman for editorial support.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lesher GY, Froelich EJ, Gruett MD, Bailey JH, Brundage RP. 1962. 1,8-Naphthyridine derivatives: a new class of chemotherapeutic agents. J Med Chem 5:1063–1065. doi: 10.1021/jm01240a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Bambeke F, Michot JM, Eldere VJ, Tulkens PM. 2005. Quinolones in 2005: an update. Clin Microbiol Infect 11:256–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang JC. 2002. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3:430–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colin F, Shantanu K, Mxwell A. 2011. Exploiting bacterial DNA gyrase as a drug target: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 92:479–497. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3557-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champoux JJ. 2001. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem 70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellon S, Parson JD, Wei Y, Hayakawa K, Swenson LL, Charifson PS, Lippke JA, Aldape T, Gross CH. 2004. Crystal structures of Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV parE subunit (24 and 43 kilodaltons): a single residue dictates differences in novobiocin potency against topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:1856–1864. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1856-1864.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heisig P. 2009. Type II topoisomerases-inhibitors, repair mechanisms and mutations. Mutagenesis 24:465–469. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gep035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sader HS, Flamm RK, Mendes RE, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. 2016. Antimicrobial activities of ceftaroline and comparator agents against organisms causing bacteremia in patients with skin and skin structure infections in U.S. medical centers, 2008 to 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2558–2563. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02794-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flamm RK, Mendes RE, Hogan PA, Streit JM, Ross JE, Jones RN. 2016. Linezolid surveillance results for the United Stats LEADER Surveillance Program 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2273–2280. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02803-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaefler S. 1989. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resistant to quinolones. J Clin Microbiol 27:335–336. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.335-336.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S, National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Team and Participating NHSN Facilities . 2013. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34:1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pendleton JN, Gorman SP, Gilmore BF. 2013. Clinical relevance of the ESKAPE pathogens. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 11:297–308. doi: 10.1586/eri.13.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. 2009. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SH, Song JH, Chung DR, Thamlikitkul V, Yang Y, Wang H, Lu M, So TM, Hsueh PR, Yasin RM, Carlos CC, Pham HV, Lalitha MK, Shimono N, Perera J, Shibl AM, Baek JY, Kang CI, Ko KS, Peck KR, ANSORP Study Group . 2012. Changing trends in antimicrobial resistance and serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in Asian countries: an Asian Network for Surveillance of Resistant Pathogens (ANSORP) study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1418–1426. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05658-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nichol KA, Adam HJ, Karlowsky JA, Zhanel GG, Hoban DJ. 2008. Increasing genetic relatedness of ciprofloxacin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in Canada from 1997 to 2005. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1190–1194. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01260-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin AN, Cerceo EA, Deitelzweig SB, Pile JC, Rosenberg DJ, Sherman BM. 2014. The hospitalist perspective on treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Postgrad Med 126:18–29. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2014.03.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Bambeke F. 2014. Renaissance of antibiotics against difficult infections: focus on oritavancin and new ketolides and quinolones. Ann Med 46:512–529. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.935470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2007. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. Morbidity and Mortality Wkly Report 56:332–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2012. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. Morbidity and Mortality Wkly Report 61:581–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sissi C, Palumbo M. 2010. In front of and behind the replication fork: bacterial type IIA topoisomerases. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:2001–2024. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couturier M, Bahassi e-M, Van Melderen L. 1998. Bacterial death by DNA gyrase poisoning. Trends Microbiol 6:269–275. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellsworth EL, Tran TP, Showalter HD, Sanchez JP, Watson BM, Stier MA, Domagala JM, Gracheck SJ, Joannides ET, Shapiro MA, Dunham SA, Hanna DL, Huband MD, Gage JW, Bronstein JC, Liu JY, Nguyen DQ, Singh R. 2006. 3-aminoquinazolinediones as a new class of antibacterial agents demonstrating excellent antibacterial activity against wild-type and multidrug resistant organisms. J Med Chem 49:6435–6438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pucci MJ, Podos SD, Thanassi JA, Leggio MJ, Bradbury BJ, Deshpande M. 2011. In vitro and in vivo profiles of ACH-702, an isothiazoquinolone, against bacterial pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 55:2860–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basarab GS, Kern GH, McNulty J, Mueller JP, Lawrence K, Vishwanathan K, Alm RA, Barvian K, Doig P, Galullo V, Gardner H, Gowravaram M, Huband M, Kimzey A, Morningstar M, Kutschke A, Lahiri SD, Perros M, Singh R, Schuck VJ, Tommasi R, Walkup G, Newman JV. 2015. Responding to the challenge of untreatable gonorrhea: ETX0914, a first-in-class agent with a distinct mechanism-of-action against bacterial type II topoisomerases. Sci Rep 5:11827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savage VJ, Charrier C, Salisbury A-M, Moyo E, Forward H, Chaffer-Malam N, Metzger R, Huxley A, Kirk R, Uosis-Martin M, Noonan G, Mohmed S, Best SA, Ratcliffe AJ, Stokes NR. 2016. Biological profiling of novel tricyclic inhibitors of bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1905–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bax BD, Chan PF, Eggleston DS, Fosberry A, Gentry DR, Gorrec F, Giordano I, Hann MM, Hennessy A, Hibbs M, Huang J, Jones E, Jones J, Brown KK, Lewis CJ, May EW, Saunders MR, Singh O, Spitzfaden CE, Shen C, Shillings A, Theobald AJ, Wohlkonig A, Pearson ND, Gwynn MN. 2010. Type IIA topoisomerase inhibition by a new class of antibacterial agents. Nature 466:935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skepper CK, Armstrong D, Balibar CJ, Bauer D, Bellamacina C, Benton BM, Bussiere D, De Pascale G, De Vicente J, Dean CR, Dhumale B, Fisher LM, Fuller J, Fulsunder M, Holder LM, Hu C, Kantariya B, Lapointe G, Leeds JA, Li X, Lu P, Lvov A, Ma S, Madhavan S, Malekar S, McKenney D, Mergo W, Metzger L, Moser HE, Mutnick D, Noeske J, Osborne C, Patel A, Patel D, Patel T, Prajapati K, Prosen KR, Reck F, Richie DL, Rico A, Sanderson MR, Satasia S, Sawyer WS, Selvarajah J, Shah N, Shanghavi K, Shu W, Thompson KV, Traebert M, Vala A, et al. 2020. Topoisomerase inhibitors addressing fluoroquinolone resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. J Med Chem 63:7773–7816. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lapointe G, Skepper CK, Holder LM, Armstrong D, Bellamacina C, Blais J, Bussiere D, Bian J, Cepura C, Chan H, Dean CR, De Pascale G, Dhumale B, Fisher LM, Fulsunder M, Kantariya B, Kim J, King S, Kossy L, Kulkarni U, Lakshman J, Leeds JA, Ling X, Lvov A, Ma S, Malekar S, McKenney D, Mergo W, Metzger L, Mhaske K, Moser HE, Mostafavi M, Namballa S, Noeske J, Osborne C, Patel A, Patel D, Patel T, Piechon P, Polyakov V, Prajapati K, Prosen KR, Reck F, Richie DL, Sanderson MR, Satasia S, Savani B, Selvarajah J, Sethuraman V, Shu W, et al. 2021. Discovery and optimization of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV inhibitors with potent activity against fluoroquinolone-resistant Gram-positive bacteria. J Med Chem 64:6329–6357. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biedenbach DJ, Huband MD, Hackel M, de Jonge BL, Sahm DF, Bradford PA. 2015. In vitro activity of AZD0914, a novel bacterial DNA gyrase/topoisomerase IV inhibitor, against clinically-revelant Gram-positive and fastidious Gram-negative pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6053–6063. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01016-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unemo M, Golparian D, Sánchez-Busó L, Grad Y, Jacobsson S, Ohnishi M, Lahra MM, Limnios A, Sikora AE, Wi T, Harris SR. 2016. The novel 2016 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strains for global quality assurance of laboratory investigations: phenotypic, genetic and reference genome characterization. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:3096–3108. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Speer BS, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. 1992. Bacterial resistance to tetracycline: mechanisms, transfer, and clinical significance. Clin Microbiol Rev 5:387–399. doi: 10.1128/CMR.5.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Methods for dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 10th ed. CLSI document M07-A10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2012. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria; approved standard, 8th ed. CLSI document M11-A8. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2011. Susceptibility testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardiae, and other aerobic Actinomycetes; approved standard, 2nd ed. CLSI document M24-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2016. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria; approved guideline, 3rd ed. CLSI document M45-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents; approved guideline. CLSI document M26-A. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charrier C, Salisbury AM, Savage VJ, Duffy T, Moyo E, Chaffer-Malam N, Ooi N, Newman R, Cheung J, Metzger R, McGarry D, Pichowicz M, Sigerson R, Cooper IR, Nelson G, Butler HS, Craighead M, Ratcliffe AJ, Best SA, Stokes NR. 2017. Novel Bacterial Topoisomerase Inhibitors with Potent Broad-Spectrum Activity against Drug-Resistant Bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02100–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Approved standard M100, 28th ed. Informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2016. Tygacil: highlights of prescribing information. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Philadelphia, PA. http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=491. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download aac.00921-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.3 MB (289.1KB, pdf)