ABSTRACT

Bacterial populations can survive exposure to antibiotics through transient phenotypic and gene expression changes. These changes can be attributed to a small subpopulation of bacteria, giving rise to antibiotic persistence. Although this phenomenon has been known for decades, much remains to be learned about the mechanisms that drive persister formation. The RNA-binding protein ProQ has recently emerged as a global regulator of gene expression. Here, we show that ProQ impacts persister formation in Salmonella. In vitro, ProQ contributes to growth arrest in a subset of cells that are able to survive treatment at high concentrations of different antibiotics. The underlying mechanism for ProQ-dependent persister formation involves the activation of metabolically costly processes, including the flagellar pathway and the type III protein secretion system encoded on Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. Importantly, we show that the ProQ-dependent phenotype is relevant during macrophage infection and allows Salmonella to survive the combined action of host immune defenses and antibiotics. Together, our data highlight the importance of ProQ in Salmonella persistence and pathogenesis.

KEYWORDS: ProQ, RNA-binding protein, persister formation, antibiotic persistence, Salmonella, flagella, antibiotic persisters, flagellar gene regulation

INTRODUCTION

In nature, bacterial populations are constantly exposed to changing and stressful conditions and must rapidly adapt to survive. Phenotypic heterogeneity allows a bacterial population to split into subpopulations with different growth and survival properties as a result of changes in gene expression. Such heterogeneity underlies a phenomenon known as antibiotic persistence. Persister bacteria comprise a subpopulation that is transiently tolerant to antibiotics through growth arrest rather than genetic change (1–4). Persisters can resume growth, and if this occurs after antibiotic removal, a population of both persister and susceptible bacteria is reestablished (1–4). Increasing evidence suggests that the regrowth of persisters contributes to prolonged and recurrent infections (5–8) and facilitates the development of antibiotic resistance (9–11). For example, within macrophages, the intracellular pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Salmonella) forms a subpopulation of nongrowing persisters that can survive the combined action of host cell defense and antibiotics (2, 3, 8, 12) and promote the spread of antibiotic resistance plasmids upon regrowth (9).

Persisters may form spontaneously through fluctuations in gene expression. However, spontaneous persisters seem to be less common than triggered persisters, which are formed in response to multiple environmental signals such as nutrient limitation (13, 14), pH variation (2, 3), oxidative stress (15, 16), extracellular metabolites (17, 18), high cell density (19), and antibiotic exposure (20). However, the underlying mechanisms responsible for persister formation are not always understood, often because of ambiguous results that arise from difficulties in distinguishing antibiotic persistence from tolerance (21). Nevertheless, several mechanisms have repeatedly been shown to induce persister formation, including the activation of the stringent response (22–25) and the SOS response (26, 27), the induction of toxin-antitoxin modules (2, 6, 26–30), a drop in ATP levels (31–34), the induction of prophages (35, 36), and protein aggregation (37). Although persisters have generally been associated with cell dormancy, active cellular processes such as antioxidant scavenging and antibiotic efflux have been shown to promote persistence (13, 38). Moreover, intracellular Salmonella persisters actively secrete effector proteins into the host cell cytosol (12). Genome-wide screens have revealed many additional genes involved in prolonged growth arrest and persister formation (39–43). For example, the expression of virulence genes important for invasion imposes a metabolic burden on Salmonella, leading to the formation of a nongrowing antibiotic persister subpopulation (44, 45). Still, in most cases, the mechanistic role of genes involved in antibiotic persistence remains to be established.

The RNA-binding protein (RBP) ProQ has recently been recognized as a major posttranscriptional regulator of gene expression in Salmonella and Escherichia coli (46–50). ProQ binds to several hundred mRNAs and small RNAs (sRNAs) through the recognition of structured motifs (46, 47, 49–53). The regulatory outcomes of ProQ binding include stabilization of RNA targets (46–48, 52, 54) and translational mRNA repression via base-pairing sRNAs (48, 52). Through its RNA-binding and regulatory activities, ProQ contributes to several cellular responses in Salmonella and E. coli, such as adaptation to osmotic and chemical stress (55, 56), motility (46, 48, 57), biofilm formation (58), and bacterial virulence (48). Interestingly, several evolutionary experiments have identified adaptive loss-of-function mutations in proQ, suggesting that ProQ can negatively affect growth, which under certain conditions becomes disadvantageous (59–63). Consequently, we sought to determine whether and, if so, how ProQ affects Salmonella growth and what implications this has for bacterial persistence and pathogenesis.

In this study, we show that ProQ impacts the growth of Salmonella. Specifically, ProQ contributes to growth arrest in a subset of cells within a Salmonella population in vitro and, thus, the generation of distinct subpopulations of bacteria with different growth and survival properties. Accordingly, we show that ProQ promotes the formation of persisters that can survive high concentrations of different antibiotics, which are lethal to the rest of the population. In addition to providing an underlying mechanism for ProQ-dependent persister formation that relies on the expression of genes encoding flagella and the pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system, we show that this phenotype is relevant during macrophage infection. Together, our data expand the physiological role of ProQ and show that this RBP is critical for the ability of Salmonella to survive antibiotic treatment.

RESULTS

ProQ reduces the growth rate of Salmonella.

Bacterial growth and survival depend on efficient adaptation to rapidly changing conditions. In Salmonella and E. coli, the RNA-binding protein ProQ plays a central role in adaptation by controlling the expression of a large number of genes (46–50). Previous studies demonstrated that adaptive mutations accumulate in the proQ gene in E. coli during laboratory evolution and confer a growth advantage over wild-type (WT) bacteria (59–61). These findings led us to investigate whether ProQ affects the growth of Salmonella. First, Salmonella SL1344 cells were grown in LB medium in 96-well plates for 16 h, and the optical density (OD) of cell populations was measured (Fig. 1A). The growth curves generated from the OD measurements suggested no obvious differences between the wild-type, ΔproQ, and ProQ complementation strains. We then asked whether a putative impact of ProQ on growth might be observable only during extended growth periods. To test this, competition experiments were performed. A Salmonella SL1344 ΔproQ strain carrying a chloramphenicol resistance marker gene was competed against a wild-type strain carrying a kanamycin resistance marker gene and vice versa. Cells from both strains were mixed in equal proportions and sequentially passaged in LB medium for 80 generations (six passages), during which CFU were determined every 13th generation. The competitive index (CI) was calculated as the ratio in CFU between ΔproQ and wild-type cells divided by the initial ratio at the start of the experiment. As seen in Fig. 1B and C, the ΔproQ strain outcompeted its wild-type counterpart irrespective of the antibiotic resistance marker used for selection. At the 80th generation, ΔproQ mutant cells outnumbered wild-type cells by approximately 10:1 (Fig. 1B and C). These results show that proQ imposes a burden on Salmonella growth at the population level.

FIG 1.

Effects of ProQ on Salmonella growth. (A) Growth curves of Salmonella SL1344 wild-type or ΔproQ cells carrying an empty control vector (WT, ΔproQ) or an IPTG-inducible proQ overexpression construct (pProQ). The optical density was monitored at 600 nm during growth in LB medium supplemented with IPTG (500 μM) in 96-well plates. The average values of six replicates with standard deviations (SD) are shown. (B and C) Growth competition experiments between Salmonella SL1344 strains. Salmonella wild-type and ΔproQ strains carrying antibiotic resistance marker genes (CamR, gene conferring chloramphenicol resistance; KanR, gene conferring kanamycin resistance) were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 in LB medium and incubated at 37°C. At roughly 24-h intervals, mixtures were plated on selective agar plates to determine CFU counts, and the remaining mixtures were serially passaged by 10,000-fold dilution in fresh LB medium for regrowth. Competitive indexes were calculated as the ratio of mutant cells to wild-type cells at the indicated generation divided by the initial ratio. Average values of six (generations 0 to 40) and three (generations 50 to 80) replicates with standard errors of the means (SEM) are shown.

ProQ contributes to the formation of a growth-arrested Salmonella population.

We next investigated the effect of ProQ on Salmonella growth at the single-cell level using fluorescence dilution (FD) (2, 3). This method is based on the dilution of a preformed pool of stable green fluorescence protein (GFP) after its induction has been stopped (Fig. 2A). In growing cells, the GFP signal intensity decreases 2-fold for each cell division, while nongrowing cells retain the initial high GFP intensity. For this purpose, the dual-fluorescence plasmid pFCcGi was used, which carries an arabinose-inducible GFP gene to monitor bacterial growth and a constitutively expressed mCherry gene for robust detection of bacterial cells during flow cytometry analysis (64). Salmonella SL1344 carrying pFCcGi was grown overnight in LB medium supplemented with arabinose to induce GFP expression. Cells were subsequently diluted 1,000-fold into fresh medium lacking the inducer and harvested at hourly intervals thereafter. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the majority of Salmonella wild-type and ΔproQ cells had undergone division as observed by a decrease in GFP signal intensity over time (Fig. 2B; Fig. S1). Nevertheless, nongrowing cells that retained a high GFP signal were detected in both wild-type and ΔproQ populations (Fig. 2C). The Salmonella ΔproQ population displayed a significantly smaller fraction of nongrowing cells than the wild-type population during early exponential growth (Fig. 2C), indicating that ProQ contributes to the formation of growth-arrested cells within the Salmonella population.

FIG 2.

Single-cell analysis of Salmonella growth using fluorescence dilution in vitro. (A) Schematic of the fluorescence dilution method (2, 3, 12). Bacterial cells were labeled by inducing the expression of green fluorescence protein (GFP). After the accumulation of GFP, bacterial cells were transferred into fresh medium without an inducer, and changes in the GFP signal intensity were monitored by flow cytometry analysis. In growing cells, the GFP signal intensity decreases with each cell division. In nongrowing cells, the GFP signal intensity is retained. (B) Flow cytometry detection of green fluorescence in a Salmonella SL1344 wild-type population carrying plasmid pFCcGi (64). Bacterial cultures were grown to stationary phase in LB medium supplemented with arabinose (0.2%) to induce GFP expression. Upon regrowth in fresh LB medium without an inducer, dilution of the preformed pool of GFP was monitored during 0 h, 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h. Representative data are shown for one out of three replicates. Data for monitoring fluorescence dilution in SL1344 ΔproQ populations are shown in Fig. S1. a.u., arbitrary units. (C) Quantification of the percentage of nongrowing cells for Salmonella wild-type and ΔproQ strains (from panel B) 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h after regrowth in fresh LB medium. The average values from three replicates with SD are shown. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t test (*, P < 0.1; **, P < 0.01; NS, nonsignificant).

Flow cytometry detection of green fluorescence in a Salmonella SL1344 ΔproQ population carrying the plasmid pFCcGi (64). Bacterial cultures were grown to stationary phase in LB medium supplemented with arabinose (0.2%) to induce GFP expression. Upon regrowth in fresh LB medium without an inducer, dilution of the preformed pool of GFP was monitored during 0 h, 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h. Representative data are shown for one out of three replicates. Data for monitoring fluorescence dilution in an SL1344 wild-type population are shown in Fig. 2B. Download FIG S1, EPS file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

ProQ promotes Salmonella survival in the presence of antibiotics.

The formation of nongrowing cells within a bacterial population has been linked to antibiotic persistence (2–4, 65). We therefore assessed whether ProQ influences Salmonella antibiotic persistence. To this end, we performed persister assays with exponential-phase cultures treated with the DNA-damaging fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin at 60× MIC for 5 h (Fig. 3A). Time-dependent killing curves revealed a biphasic pattern with a plateau of surviving persister bacteria (1) and showed that 5 h was an appropriate time point for determining persister levels under the tested conditions (Fig. S2). In these experiments, Salmonella deleted for proQ had three times lower persister levels than the wild-type strain. Given that persisters often exhibit a multidrug tolerance phenotype (66), persister assays were also carried out with the cell wall synthesis-inhibiting beta-lactam ampicillin, at 60× MIC for 5 h. Similar to the results presented in Fig. 3A, the ΔproQ strain had eight times lower persister levels than the wild-type strain (Fig. 3B). MIC tests confirmed that changes in survival were not due to changes in resistance to either ampicillin or ciprofloxacin (Table S1). Together, these results show that ProQ promotes persister formation in Salmonella.

FIG 3.

Effects of ProQ on Salmonella antibiotic persistence in vitro. Exponential-phase cultures of Salmonella SL1344 wild-type and ΔproQ strains were treated with ciprofloxacin (1 μg/mL; 60× MIC) (A) and ampicillin (50 μg/mL; 60× MIC) (B) for 5 h. CFU counts were determined before and after treatments to calculate the surviving fraction. Average values from 12 (A) and 6 (B) replicates with SEM are shown. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t test (*, P < 0.1).

Time-dependent antibiotic killing of the Salmonella wild-type strain. Exponential-phase cultures were treated with ciprofloxacin (1 μg/mL; 60× MIC) (A) or cefotaxime (100 μg/mL; 100× MIC) (B), and sample aliquots were taken at the indicated time intervals. CFU counts were determined before and after treatment and normalized to time zero. Average values from nine (A) or three (B) replicates and the standard errors of the means (SEM) are shown. Download FIG S2, EPS file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

MICs determined for Salmonella strains using Etest strips. The average values from three replicates with SD are shown. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

ProQ contributes to persister formation by increasing the expression of flagellar genes.

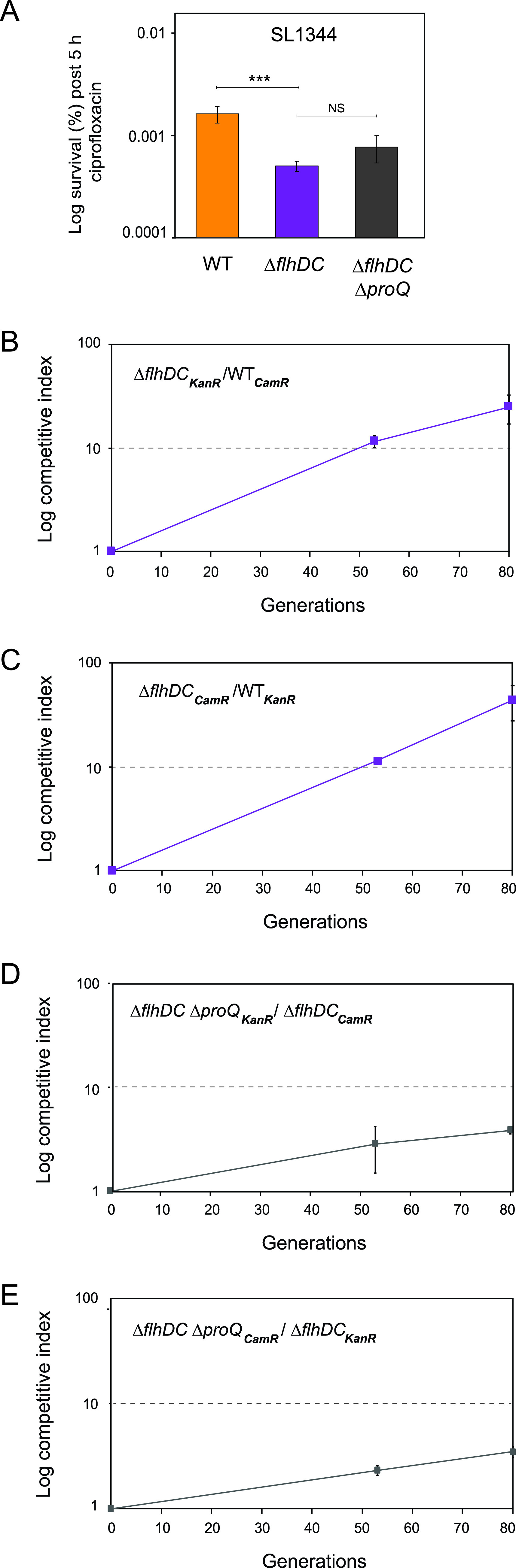

We next asked by which mechanism ProQ promotes Salmonella persister formation. Recent transcriptomic analyses revealed that deletion of proQ leads to global effects on gene expression. For instance, genes located within the flagellar pathway are enriched among differentially expressed genes (46, 48). Previous studies using transposon mutagenesis in E. coli demonstrated that disruption of several flagellar genes decreases persister formation (42). Given that deletion of proQ in Salmonella reduces the expression of most flagellar genes (46–48, 57), we asked whether flagellar synthesis has a role in the formation of ProQ-dependent persister cells. To this end, we constructed a Salmonella SL1344 strain lacking flhDC, encoding the master regulator that controls the expression of all flagellar genes (67, 68). Deletion of flhDC resulted in a significant reduction in persister levels compared to the wild-type strain following 5 h of ciprofloxacin treatment (Fig. 4A), indicating that flagellar synthesis contributes to persister formation in Salmonella. Strikingly, deleting proQ did not reduce the persister levels in the ΔflhDC strain (Fig. 4A). This shows that ProQ-dependent effects on persister frequencies require a functional flagellar pathway and indicates that ProQ-dependent persister formation in Salmonella is linked to ProQ-dependent regulation of flagellar gene expression (57).

FIG 4.

Effects of ProQ and FlhDC on antibiotic persistence in vitro and growth. (A) Exponential-phase cultures of Salmonella SL1344 wild-type, ΔflhDC, and ΔflhDC ΔproQ strains were treated with ciprofloxacin (1 μg/mL; 60× MIC) for 5 h. CFU counts were determined before and after treatment to calculate the surviving fraction. Average values from 5 (wild-type), 11 (ΔflhDC), and 8 (ΔflhDC ΔproQ) replicates with SEM are shown. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t test (***, P < 0.001; NS, nonsignificant). (B to E) Growth competition experiments between Salmonella strains. Salmonella SL1344 wild-type and ΔflhDC strains (B and C) or ΔflhDC and ΔflhDC ΔproQ strains (D and E) carrying antibiotic resistance marker genes (CamR, gene conferring chloramphenicol resistance; KanR, gene conferring kanamycin resistance) were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 in LB medium and incubated at 37°C. At roughly 24-h intervals, mixtures were plated on selective agar plates to determine CFU counts, and the remaining mixtures were serially passaged by 10,000-fold dilution in fresh LB medium for regrowth. (B and C) Competitive indexes were calculated as the ratio of ΔflhDC cells to wild-type cells at the indicated generation divided by the initial ratio. (D and E) Competitive indexes were calculated as the ratio of ΔflhDC ΔproQ cells to ΔflhDC cells at the indicated generation divided by the initial ratio. The average values from three replicates with SD are shown.

The buildup and operation of flagella is estimated to use 5 to 10% of the total cell energy budget (69, 70) and, hence, confers a substantial cost for Salmonella growth. It is therefore possible that the decreased persister levels in the ΔflhDC mutant (Fig. 4A) are linked to the increased availability of energy resources otherwise needed for producing flagella. To test this, we competed a Salmonella SL1344 ΔflhDC strain carrying a chloramphenicol resistance marker gene against a wild-type strain carrying a kanamycin resistance marker gene and vice versa (Fig. 4B and C). As expected, strains lacking flhDC strongly outcompeted the wild-type strain by 25:1 at the 80th generation, verifying that flagellar gene expression confers a growth disadvantage for Salmonella.

Since ProQ-dependent persister formation requires a functional flagellar pathway (Fig. 4A), we next asked whether the observed growth disadvantage conferred by ProQ (Fig. 1B and C) could be attributable to the expression of flagellar genes. To address this, the competitive fitness of ProQ was studied in a ΔflhDC background. The Salmonella SL1344 ΔproQ ΔflhDC strain carrying a chloramphenicol resistance marker gene was competed against a ΔflhDC strain carrying a kanamycin resistance marker gene and vice versa (Fig. 4D and E). In contrast to previous results (Fig. 1B and C), the growth advantage conferred by the deletion of proQ was strongly reduced in the ΔflhDC background (Fig. 4D and E). Together, these results suggest that deletion of proQ, which entails reduced activation of flagellar synthesis (46, 48, 57), leads to a growth advantage in Salmonella.

ProQ contributes to persister formation by increasing the expression of genes encoding the SPI-2 type III secretion system.

Activation of virulence-related processes in a nonhost environment also confers a metabolic cost for Salmonella, and the resulting growth reduction has been linked to antibiotic persistence (44, 45). The data in Fig. 4 suggest that ProQ promotes the formation of persisters in vitro through the activation of a costly process, the flagellar pathway. We asked whether the activation of other metabolically costly processes by ProQ promotes persister formation. Recent transcriptomic analyses showed that deletion of proQ leads to a downregulation of genes in Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2), which encode a type III secretion system (T3SS) important for intracellular survival (48). To test whether ProQ affects persister formation through the SPI-2-encoded T3SS, we constructed a Salmonella SL1344 strain lacking slyA, which encodes one of the main transcriptional activators of the SPI-2 locus (71). We performed persister assays in acidic SPI-2-inducing medium with exponential-phase cultures treated with the beta-lactam cefotaxime for 5 h (Fig. 5). Consistent with previous results (Fig. 3 and 4A), Salmonella deleted for proQ had two times lower persister levels than the wild-type strain. Furthermore, the deletion of slyA resulted in a significant reduction in persister levels compared to the wild-type strain, indicating that the production of the SPI-2 T3SS contributes to the antibiotic persistence of Salmonella. Notably, deleting proQ did not reduce the persister levels in the slyA mutant. Thus, ProQ activation of the SPI-2-encoded T3SS (48) promotes Salmonella survival in the presence of antibiotics under in vitro conditions that mimic the intracellular environment.

FIG 5.

Effects of ProQ and SlyA on antibiotic persistence in vitro. Exponential-phase cultures of Salmonella SL1344 wild-type, ΔproQ, ΔslyA, and ΔslyA ΔproQ strains in acidic SPI-2 medium were treated with cefotaxime (100 μg/mL) for 5 h. CFU counts were determined before and after treatment to calculate the surviving fraction. The average values from four replicates with SEM are shown. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t test (***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; NS, nonsignificant).

ProQ promotes Salmonella survival in the presence of antibiotics during macrophage infection.

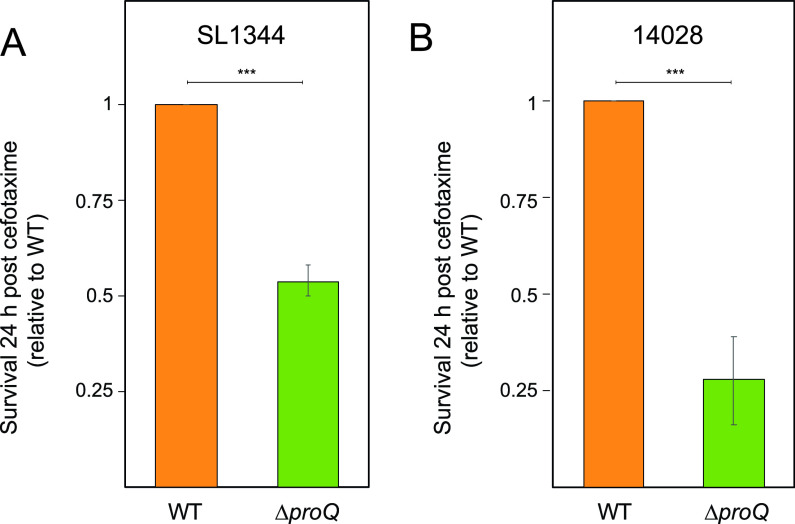

Salmonella is an intracellular pathogen that produces high levels of persister cells following internalization by macrophages (2, 3, 8, 12). As our in vitro work revealed that ProQ contributes to persister formation in Salmonella (Fig. 4 and 5), we asked whether this phenotypic effect could be observed in vivo. Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were infected with Salmonella and treated with the cell wall synthesis-inhibiting beta-lactam cefotaxime at 100× MIC for 24 h. The fraction of surviving cells was determined by release from macrophages and CFU counts. Consistent with our in vitro results (Fig. 3 and 5A), the number of intramacrophage persister cells decreased by 50% in Salmonella SL1344 lacking proQ compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 6A; Table S5). Given that the strain SL1344 is auxotrophic for histidine (72), we reasoned that intracellular limitation of this amino acid could in itself affect Salmonella growth and, thus, mask the persister population effect (73). Therefore, persister assays were repeated with ΔproQ and wild-type strains of Salmonella 14028, which are proficient in histidine biosynthesis (74, 75). The number of intramacrophage persister cells decreased by approximately 75% in 14028 ΔproQ compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 6B). The MIC for cefotaxime was not affected by the proQ deletion, neither in SL1344 nor in 14028, ruling out antibiotic resistance as a plausible explanation for differences in persister levels (Table S1). Together, this shows that ProQ promotes Salmonella persisters during macrophage infection.

FIG 6.

Effects of ProQ on Salmonella antibiotic persistence during macrophage infection. Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages were infected with wild-type or ΔproQ strains of Salmonella SL1344 (A) and 14028 (B) and treated with cefotaxime (100 μg/mL; 100× MIC) for 24 h. For Salmonella SL1344, the infection medium was supplemented with 2 mM histidine. Intracellular Salmonella cells were released from macrophages, and the surviving fraction was determined by CFU counts and normalized to wild-type levels. Average values from six replicates (A) and four replicates (B) with SEM are shown. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t test (***, P < 0.001).

CFU counts from a representative in vivo persister assay. Download Table S5, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.7KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

The effect of ProQ on the survival of intracellular Salmonella in the presence of antibiotics (Fig. 5) might reflect effects on bacterial growth. To test if ProQ affects single-cell growth within the intracellular Salmonella population, the FD method was used (Fig. 2A). Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages were infected with preinduced Salmonella carrying the dual-fluorescence plasmid pFCcGi. After 16 h of infection, the released Salmonella cells were subjected to flow cytometry for quantification of growing and nongrowing fractions (Fig. 7). Interestingly, no obvious differences in the fraction of nongrowing cells were observed between SL1344 wild-type and ΔproQ intracellular populations (Fig. 7A). This contrasted with the smaller fraction of nongrowing cells observed for the ΔproQ population that formed in the LB medium (Fig. 2). Quantification of proliferation by FD revealed significantly slower growth for single cells within the ΔproQ population than in the wild-type population (Fig. 7B). Similar results were observed for mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages infected with preinduced Salmonella 14028 carrying pFCcGi. The 14028 wild-type and ΔproQ populations showed no differences in the fraction of nongrowing cells, but single cells within the ΔproQ population grew to a lesser extent than the wild-type cells (Fig. 7C and D). Together, these results indicate that ProQ promotes the growth (Fig. 7) and survival (Fig. 6) of single cells within a Salmonella population during macrophage infection, presumably through the activation of the SPI-2-encoded T3SS (48), which in contrast to flagella, is upregulated during intracellular growth (76) and is required for the survival of antibiotic persister cells (Fig. 5) (12).

FIG 7.

Single-cell analysis of Salmonella growth using fluorescence dilution during macrophage infection. Salmonella SL1344 and 14028 wild-type and ΔproQ strains were grown to stationary phase in LB medium supplemented with arabinose (0.2%) to induce GFP expression. Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages were infected with the preinduced Salmonella cells for 16 h. Intracellular Salmonella cells were released from macrophages and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. (A and C) Quantification of the fraction of nongrowing cells. (B and D) Quantification of the number of undergone generations. The average values from six replicates with SD are shown. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t test (**, P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Bacteria produce phenotypic subpopulations of nongrowing persisters that can survive exposure to antibiotics (77, 78). Understanding the molecular pathways essential for the formation of these persisters may lead to new strategies for their elimination. To date, several global regulators, toxin-antitoxin modules, and metabolic enzymes have been linked to persister formation (79–81). Here, we show for the first time that the global RNA-binding protein ProQ promotes persister formation.

In Fig. 1, we show that ProQ impacts the growth of Salmonella. Specifically, ProQ contributes to the formation of nongrowing cells within the Salmonella population (Fig. 2) that are able to survive treatment at high concentrations of antibiotics (Fig. 3) without changes in resistance (Table S1) and, thus, represent persisters. ProQ promotes the formation of these nongrowing persisters in laboratory medium by activating flagellar synthesis (Fig. 4) and the SPI-2-encoded T3SS (Fig. 5). We reveal that the ProQ-dependent impact on persisters is relevant both in bacterial monoculture and during host cell infection (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

Schematic model of ProQ-dependent persister formation. During the growth of Salmonella monocultures under standard laboratory conditions, ProQ promotes the expression of energetically costly but dispensable processes such as flagella and the SPI-2 T3SS. This leads to decreased growth, an increased frequency of nongrowing cells, and higher persister levels. When Salmonella resides inside macrophages, ProQ promotes the expression of the SPI-2 T3SS, which is indispensable for the survival, growth, and maintenance of persisters under this condition.

Persisters may be generated through stochastic fluctuations in gene expression or, more commonly, upon perceiving a stress signal (2, 3, 14, 17, 19, 20). Multiple stress signals have been shown to trigger persister formation, the most common one being starvation (13), although active cellular processes also can promote persistence (reviewed in reference 80). The in vitro persister assays used in this study (Fig. 3 to 5) were performed by diluting a starved overnight culture into fresh medium. The culture was incubated until it reached exponential phase, and antibiotics were added to score the persister cells. It is therefore possible that the ProQ-induced persisters (Fig. 3 to 5) were triggered already by the preceding starvation phase. In line with this, we observed a decline in nongrowing cells after diluting a stationary-phase culture into fresh growth medium and a decrease in the fraction of nongrowing cells upon deletion of proQ (Fig. 2). Although outside the scope of this study, it would be interesting to monitor ProQ’s effect on the formation of nongrowing cells and persisters upon entry into stationary phase. ProQ-dependent persister formation was also observed during macrophage infection (Fig. 6). After uptake by macrophages, Salmonella encounters an acidified and nutrient-limited environment, which has been linked to persister formation (2). It is therefore possible that the ProQ-induced persisters in macrophages (Fig. 6) were triggered by starvation as well.

Previous work has suggested the role of ProQ in the regulation of flagellar genes (46–48, 57). We show here that ProQ promotes persister formation by activating flagellar synthesis (Fig. 4). Thus, it appears that ProQ impacts not only flagellar synthesis itself but also persister formation through the flagellar pathway. Work in E. coli has shown that flagellar synthesis contributes to the formation of persisters, but the underlying mechanism is not completely known (42). Our work suggests that flagellar synthesis confers a growth disadvantage for bacterial cells (Fig. 4) and, thereby, entails increased persistence. A similar phenomenon has been observed in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, where a low-persister strain outcompeted a high-persister strain in both the absence and presence of antibiotics (82). In relation to this, it is tempting to speculate that the proQ deletion strain would lose its competitive advantage in the presence of antibiotics. After uptake by macrophages, flagella are no longer required for movement, and Salmonella strongly downregulates flagellar synthesis (83, 84). Therefore, it is likely that ProQ promotes persistence in vivo (Fig. 6) through a mechanism other than the activation of the flagellar pathway.

Inside macrophages, Salmonella induces the expression of a T3SS encoded on its pathogenicity island 2 and uses it to secrete effector molecules that interfere with host cell defenses (85, 86). Recently, it was shown that the survival, but not formation, of Salmonella persisters within macrophages is dependent on a functional SPI-2-encoded T3SS that allows reprogramming of the host (12). ProQ positively regulates the expression of SPI-2 genes; in its absence, the majority of these genes are downregulated (48). We show here that a functional SPI-2 T3SS is required for ProQ-dependent persister formation during in vitro conditions that mimic the host cell environment (Fig. 5). We therefore speculate that ProQ also promotes the survival of Salmonella persisters within macrophages (Fig. 6) through the activation of the SPI-2 T3SS. Interestingly, ProQ does not seem to affect the size of the nongrowing subpopulation in macrophages (Fig. 7A, C), in agreement with the fact that SPI-2 promotes persister survival but not formation. Indeed, if all intracellular persisters stem from the nongrowing population, not all nongrowers are persisters (2), and it requires additional factors other than growth arrest to successfully survive the combined action of antibiotics and macrophages (2, 12). It thus appears that ProQ is involved in the maintenance of intramacrophage persister cells rather than their formation. Like SPI-2, ProQ promotes the growth rate of the growing intracellular Salmonella population (Fig. 7B and D) (3).

While ProQ seems to promote the growth of Salmonella during macrophage infection (Fig. 7B to D), it reduces bacterial growth under standard laboratory conditions (Fig. 1B and C). We speculate that ProQ-dependent activation of flagella and SPI-2 genes (46, 48) in nonhost environments confers a metabolic cost for bacterial cells, which reduces bacterial growth (Fig. 4B to E) and increases the fraction of persister cells (Fig. 4A and 6). In line with this, the activation of other virulence-related processes, such as the SPI-1-encoded T3SS that is important for host cell invasion, has been shown to reduce Salmonella growth in nonhost environments and lead to the formation of an antibiotic persister subpopulation (44, 45). Thus, the activation of metabolically costly processes may be a more general mechanism by which Salmonella persister populations can form and evade antibiotics and is, in part, dependent on ProQ.

Previous work on Salmonella has reported that ProQ contributes to several cellular processes important for pathogenesis, such as motility (46, 48), biofilm formation (58), and bacterial virulence (48). We extend this view by demonstrating that ProQ contributes to the survival of Salmonella to antibiotic exposure. Taken together, our work expands the role of ProQ and highlights the importance of this RBP for Salmonella pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

All Salmonella strains used in this study are listed in Table S2. Salmonella cells were grown aerobically at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm in standard Luria-Bertani broth (LB) medium or SPI-2 medium (87). If applicable, the following antibiotics were added to the growth medium: kanamycin (50 μg/mL), ampicillin (100 μg/mL), tetracycline (15 μg/mL), and chloramphenicol (30 μg/mL).

Strains used in this study. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (21.1KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Plasmid construction.

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S3. The construction of plasmids pAR007, pAR009, and pFCcGi has been described elsewhere (57, 64).

Plasmids used in this study. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (18KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Strain construction.

Oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S4. The ΔflhDC mutant strain (EHS-2093) was constructed by lambda Red recombination (88) using plasmid pKD4 (89). First, a kanamycin resistance gene was amplified (EHO-1118/1119) from strain JVS-11364 (46), inserted into a Salmonella wild-type strain, and subsequently transferred to a Salmonella wild-type strain by P22 transduction (88). Second, the antibiotic resistance cassette was removed using plasmid pCP20 (90). The ΔslyA mutant strain (EHS-1880) was constructed by P22 transduction. First, the slyA gene was deleted from JVS-1574 by using phage lysate from strain 1867 from the McClelland collection (91). Second, the antibiotic resistance cassette was removed using plasmid pCP20. The proQ gene was deleted from EHS-1880, EHS-2391, EHS-2392, EHS-2093, and EHS-2209 by using P22 phage lysate from JVS-11364. The antibiotic resistance cassettes were removed using plasmid pCP20. The STM1553 pseudogene was deleted from strains JVS-1574, EHS-1880, EHS-1882, EHS-2093, and EHS-2154 by use of P22 phage lysates from SK3313 (92) and SK3318 (92).

Oligonucleotides used in this study. Download Table S4, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13.4KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Optical density measurements.

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:1,000 into fresh LB medium supplemented with 500 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG; Sigma). Cultures were grown in 96-well plates (Costar) at 37°C, and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured every 10 min for 16 h in a plate reader (Tecan Infinite Pro). The background was removed by subtracting the OD values obtained from wells with LB medium from those of wells with bacterial cells. Mean values and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for every biological replicate.

Competition experiments.

Overnight cultures of tagged mutant and parental strains were mixed in a 1:1 ratio. At roughly 24-h intervals, cell mixtures were serially passaged for 6 days by 10,000-fold dilution into 1 mL fresh LB medium or SPI-2 medium and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm. On the indicated days, the ratio of mutant to parent was measured by CFU counts on selective agar plates. Competitive indexes were calculated as the ratio of the CFU of mutant to parental cells divided by the initial ratio.

Fluorescence dilution method in vitro.

Single colonies of Salmonella strains carrying the plasmid pFCcGi were inoculated in LB medium supplemented with 0.2% l-arabinose (Sigma) and incubated overnight. The overnight cultures were diluted to an OD of 0.001 in fresh LB medium in the absence of an inducer and grown for 3 h. At hourly intervals, bacterial pellets were resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and loaded in a 96-well polystyrene plate for single-cell analysis of GFP and mCherry fluorescence. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using a MACSQuant VYB flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec). GFP was excited with a blue laser (488 nm; band-pass filter, 525/50 nm; channel B1). mCherry was excited with a yellow laser (561 nm; band-pass filter, 615/20 nm; channel Y2). A total of 100,000 events were recorded for each sample. Data were acquired with the MACSQuantify software (Miltenyi Biotec) and processed with FlowJo software (Beckton, Dickinson, and Company). For the identification of bacterial cells, the gate was set based on the constitutive mCherry signal. For the characterization of nongrowing cells, the gate was set on a retained GFP signal. The percentage of growing bacteria was calculated using the equation x = 1/1 + 2n × (nr)/r, where x is the percentage of growing bacteria, n is the number of generations that growing bacteria undergo, nr is the fraction of nongrowing bacteria measured by the retained GFP signal, and r is the fraction of growing bacteria measured by dilution in GFP signal. The number of generations was determined by calculating the log2 of the ratio in the geometric mean of GFP between the initial nondividing population and the dividing population.

In vitro persister assays.

Overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 in fresh LB medium or an OD600 of 0.04 in fresh SPI-2 medium and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm until reaching exponential phase (OD600 of 0.25 to 0.35). At that point, ciprofloxacin (1 μg/mL; 60× MIC), ampicillin (50 μg/mL; 60× MIC), or cefotaxime (100 μg/mL; 100× MIC) was added to cultures. Before and 5 h after antibiotic treatment, bacterial pellets were washed once and diluted in PBS. Samples were plated on agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. CFU counts were determined from plates containing 30 to 300 bacterial colonies. The surviving fraction of cells was determined by the ratio of CFU between treated and untreated samples.

Cell culture and infection of macrophages.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were extracted from the tibia and femur of C57BL/6 female mice (Charles River) according to a UK Home Office Project License and grown as described previously (12). For infection, bacteria from overnight cultures were opsonized with 8% mouse serum (Sigma) for 20 min and added to the BMDMs at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Infection was synchronized by centrifugation at 110 × g for 5 min. Phagocytosis was allowed to occur for 30 min at 37°C with 5% CO2. Infected BMDMs were washed three times with PBS and either collected (0-h time point [T0]) or incubated in medium with cefotaxime (100 μg/mL; 100× MIC) for 24 h (T24) at 37°C with 5% CO2. For sample collection, BMDMs were washed three times in PBS and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS. Pelleted bacteria were resuspended and diluted in fresh PBS. Bacterial dilutions were plated on agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. CFU counts were determined and normalized by dividing the number of bacteria at 24 h by the number of bacteria at T0 for each strain. The obtained values were normalized to those of the respective reference WT strains (14028s or SL1344).

Fluorescence dilution method in vivo.

Salmonella strains carrying the fluorescence dilution plasmid pFCcGi were inoculated in LB medium supplemented with 0.2% l-arabinose and incubated overnight. BMDMs were infected with the preinduced Salmonella as described above and incubated in medium with gentamicin (50 μg/mL). For BMDMs infected with Salmonella SL1344, the medium was supplemented with 2 mM histidine. After 16 h of infection, BMDMs were washed three times in PBS and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Pelleted bacteria were resuspended in PBS and subsequently subjected to flow cytometry analysis using a BD LSR II flow cytometer. GFP and mCherry fluorophores were excited at 488 nm and 561 nm, respectively, and detected at 525/50 nm and 615/20 nm, respectively. A total of 10,000 events were recorded for each sample. Data were analyzed with the FlowJo software. Nongrowing bacterial cells were identified and quantified as described above.

Data availability.

FCS files from single-cell analysis were deposited in the FlowRepository database and can be accessed via https://flowrepository.org/experiments/5329.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Koskiniemi, M. Stårsta, and Mikael Sellin for sharing bacterial strains and S. Ronneau for his assistance with flow cytometry analysis in vivo.

Funding was provided by the Swedish Research Council (EH: 2016-03656; EGHW: 2020-03622), Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (ICA16-0021), Uppsala Antibiotic Center, and Åke Wiberg Foundation.

We declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a direct contribution from E. Gerhart H. Wagner, a Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology, who arranged for and secured reviews by Kim Lewis, Northeastern University, and Jan Michiels, KU Leuven.

Contributor Information

E. Gerhart H. Wagner, Email: gerhart.wagner@icm.uu.se.

Erik Holmqvist, Email: erik.holmqvist@icm.uu.se.

Gisela Storz, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

REFERENCES

- 1.Balaban NQ, Helaine S, Lewis K, Ackermann M, Aldridge B, Andersson DI, Brynildsen MP, Bumann D, Camilli A, Collins JJ, Dehio C, Fortune S, Ghigo JM, Hardt WD, Harms A, Heinemann M, Hung DT, Jenal U, Levin BR, Michiels J, Storz G, Tan MW, Tenson T, Van Melderen L, Zinkernagel A. 2019. Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:441–448. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0196-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helaine S, Cheverton AM, Watson KG, Faure LM, Matthews SA, Holden DW. 2014. Internalization of salmonella by macrophages induces formation of nonreplicating persisters. Science 343:204–208. doi: 10.1126/science.1244705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helaine S, Thompson JA, Watson KG, Liu M, Boyle C, Holden DW. 2010. Dynamics of intracellular bacterial replication at the single cell level. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:3746–3751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000041107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roostalu J, Jõers A, Luidalepp H, Kaldalu N, Tenson T. 2008. Cell division in Escherichia coli cultures monitored at single cell resolution. BMC Microbiol 8:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulcahy LR, Burns JL, Lory S, Lewis K. 2010. Emergence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains producing high levels of persister cells in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Bacteriol 192:6191–6199. doi: 10.1128/JB.01651-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schumacher MA, Balani P, Min J, Chinnam NB, Hansen S, Vulić M, Lewis K, Brennan RG. 2015. HipBA-promoter structures reveal the basis of heritable multidrug tolerance. Nature 524:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature14662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torrey HL, Keren I, Via LE, Lee JS, Lewis K. 2016. High persister mutants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 11:e0155127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rycroft JA, Gollan B, Grabe GJ, Hall A, Cheverton AM, Larrouy-Maumus G, Hare SA, Helaine S. 2018. Activity of acetyltransferase toxins involved in Salmonella persister formation during macrophage infection. Nat Commun 9:1993. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04472-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakkeren E, Huisman JS, Fattinger SA, Hausmann A, Furter M, Egli A, Slack E, Sellin ME, Bonhoeffer S, Regoes RR, Diard M, Hardt WD. 2019. Salmonella persisters promote the spread of antibiotic resistance plasmids in the gut. Nature 573:276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1521-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin-Reisman I, Ronin I, Gefen O, Braniss I, Shoresh N, Balaban NQ. 2017. Antibiotic tolerance facilitates the evolution of resistance. Science 355:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.aaj2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Windels EM, Michiels JE, Fauvart M, Wenseleers T, Van den Bergh B, Michiels J. 2019. Bacterial persistence promotes the evolution of antibiotic resistance by increasing survival and mutation rates. ISME J 13:1239–1251. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stapels DAC, Hill PWS, Westermann AJ, Fisher RA, Thurston TL, Saliba AE, Blommestein I, Vogel J, Helaine S. 2018. Salmonella persisters undermine host immune defenses during antibiotic treatment. Science 362:1156–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen D, Joshi-Datar A, Lepine F, Bauerle E, Olakanmi O, Beer K, McKay G, Siehnel R, Schafhauser J, Wang Y, Britigan BE, Singh PK. 2011. Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science 334:982–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1211037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown DR. 2019. Nitrogen starvation induces persister cell formation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 201:e00622-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00622-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y, Vulić M, Keren I, Lewis K. 2012. Role of oxidative stress in persister tolerance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4922–4926. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00921-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowe SE, Wagner NJ, Li L, Beam JE, Wilkinson AD, Radlinski LC, Zhang Q, Miao EA, Conlon BP. 2020. Reactive oxygen species induce antibiotic tolerance during systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection. Nat Microbiol 5:282–290. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0627-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Möker N, Dean CR, Tao J. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa increases formation of multidrug-tolerant persister cells in response to quorum-sensing signaling molecules. J Bacteriol 192:1946–1955. doi: 10.1128/JB.01231-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung V, Lévesque CM. 2012. A stress-inducible quorum-sensing peptide mediates the formation of persister cells with noninherited multidrug tolerance. J Bacteriol 194:2265–2274. doi: 10.1128/JB.06707-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh A, Baltekin Ö, Wäneskog M, Elkhalifa D, Hammarlöf DL, Elf J, Koskiniemi S. 2018. Contact-dependent growth inhibition induces high levels of antibiotic-tolerant persister cells in clonal bacterial populations. EMBO J 37:e98026. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goormaghtigh F, Van Melderen L. 2019. Single-cell imaging and characterization of Escherichia coli persister cells to ofloxacin in exponential cultures. Sci Adv 5:eaav9462. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav9462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ronneau S, Hill PW, Helaine S. 2021. Antibiotic persistence and tolerance: not just one and the same. Curr Opin Microbiol 64:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2021.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amato SM, Orman MA, Brynildsen MP. 2013. Metabolic control of persister formation in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell 50:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viducic D, Ono T, Murakami K, Susilowati H, Kayama S, Hirota K, Miyake Y. 2006. Functional analysis of spoT, relA and dksA genes on quinolone tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa under nongrowing condition. Microbiol Immunol 50:349–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korch SB, Henderson TA, Hill TM. 2003. Characterization of the hipA7 allele of Escherichia coli and evidence that high persistence is governed by (p)ppGpp synthesis. Mol Microbiol 50:1199–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helaine S, Kugelberg E. 2014. Bacterial persisters: formation, eradication, and experimental systems. Trends Microbiol 22:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel J, Argaman L, Wagner EGH, Altuvia S. 2004. The small RNA IstR inhibits synthesis of an SOS-induced toxic peptide. Curr Biol 14:2271–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dörr T, Vulić M, Lewis K. 2010. Ciprofloxacin causes persister formation by inducing the TisB toxin in Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol 8:e1000317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moyed HS, Bertrand KP. 1983. hipA, a newly recognized gene of Escherichia coli K-12 that affects frequency of persistence after inhibition of murein synthesis. J Bacteriol 155:768–775. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.768-775.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross BN, Thiriot JD, Wilson SM, Torres AG. 2020. Predicting toxins found in toxin-antitoxin systems with a role in host-induced Burkholderia pseudomallei persistence. Sci Rep 10:16923. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73887-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berghoff BA, Hoekzema M, Aulbach L, Wagner EGH. 2017. Two regulatory RNA elements affect TisB-dependent depolarization and persister formation. Mol Microbiol 103:1020–1033. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unoson C, Wagner EGH. 2008. A small SOS-induced toxin is targeted against the inner membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 70:258–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conlon BP, Rowe SE, Gandt AB, Nuxoll AS, Donegan NP, Zalis EA, Clair G, Adkins JN, Cheung AL, Lewis K. 2016. Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat Microbiol 1:16051. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shan Y, Gandt AB, Rowe SE, Deisinger JP, Conlon BP, Lewis K. 2017. ATP-dependent persister formation in Escherichia coli. mBio 8:e02267-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02267-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolau SE, Lewis K. 2022. The role of integration host factor in Escherichia coli persister formation. mBio 13:e03420-21. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03420-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandvik EL, Fazen CH, Henry TC, Mok WWK, Brynildsen MP. 2015. Non-monotonic survival of Staphylococcus aureus with respect to ciprofloxacin concentration arises from prophage-dependent killing of persisters. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 8:778–792. doi: 10.3390/ph8040778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harms A, Fino C, Sørensen MA, Semsey S, Gerdes K. 2017. Prophages and growth dynamics confound experimental results with antibiotic-tolerant persister cells. mBio 8:e01964-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01964-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dewachter L, Bollen C, Wilmaerts D, Louwagie E, Herpels P, Matthay P, Khodaparast L, Khodaparast L, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Michiels J. 2021. The dynamic transition of persistence toward the viable but nonculturable state during stationary phase is driven by protein aggregation. mBio 12:e00703-21. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00703-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pu Y, Zhao Z, Li Y, Zou J, Ma Q, Zhao Y, Ke Y, Zhu Y, Chen H, Baker MAB, Ge H, Sun Y, Xie XS, Bai F. 2016. Enhanced efflux activity facilitates drug tolerance in dormant bacterial cells. Mol Cell 62:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keren I, Shah D, Spoering A, Kaldalu N, Lewis K. 2004. Specialized persister cells and the mechanism of multidrug tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 186:8172–8180. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8172-8180.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu Y, Coates ARM. 2005. Transposon mutagenesis identifies genes which control antimicrobial drug tolerance in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett 243:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen S, Lewis K, Vulić M. 2008. Role of global regulators and nucleotide metabolism in antibiotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2718–2726. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00144-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shan Y, Lazinski D, Rowe S, Camilli A, Lewis K. 2015. Genetic basis of persister tolerance to aminoglycosides in Escherichia coli. mBio 6:e00078-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00078-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhar N, McKinney JD. 2010. Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence mutants identified by screening in isoniazid-treated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:12275–12280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003219107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sturm A, Heinemann M, Arnoldini M, Benecke A, Ackermann M, Benz M, Dormann J, Hardt WD. 2011. The cost of virulence: retarded growth of Salmonella Typhimurium cells expressing type III secretion system 1. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002143. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnoldini M, Vizcarra IA, Peña-Miller R, Stocker N, Diard M, Vogel V, Beardmore RE, Hardt WD, Ackermann M. 2014. Bistable expression of virulence genes in Salmonella leads to the formation of an antibiotic-tolerant subpopulation. PLoS Biol 12:e1001928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smirnov A, Förstner KU, Holmqvist E, Otto A, Günster R, Becher D, Reinhardt R, Vogel J. 2016. Grad-seq guides the discovery of ProQ as a major small RNA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:11591–11596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609981113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holmqvist E, Li L, Bischler T, Barquist L, Vogel J. 2018. Global maps of ProQ binding in vivo reveal target recognition via RNA structure and stability control at mRNA 3′ ends. Mol Cell 70:971–982.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westermann AJ, Venturini E, Sellin ME, Förstner KU, Hardt WD, Vogel J. 2019. The major RNA-binding protein ProQ impacts virulence gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. mBio 10:e02504-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02504-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerovac M, Mouali YEL, Kuper J, Kisker C, Barquist L, Vogel J. 2020. Global discovery of bacterial RNA-binding proteins by RNase-sensitive gradient profiles reports a new FinO domain protein. RNA 26:1448–1463. doi: 10.1261/rna.076992.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hör J, Di Giorgio S, Gerovac M, Venturini E, Förstner KU, Vogel J. 2020. Grad-seq shines light on unrecognized RNA and protein complexes in the model bacterium Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 48:9301–9319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez GM, Hardwick SW, Maslen SL, Skehel MJ, Holmqvist E, Vogel J, Bateman A, Luisi BF, Broadhurst RW. 2017. Structure of the Escherichia coli ProQ RNA-binding protein. RNA 23:696–711. doi: 10.1261/rna.060343.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smirnov A, Wang C, Drewry LL, Vogel J. 2017. Molecular mechanism of mRNA repression in trans by a ProQ-dependent small RNA. EMBO J 36:1029–1045. doi: 10.15252/embj.201696127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stein EM, Kwiatkowska J, Basczok MM, Gravel CM, Berry KE, Olejniczak M. 2020. Determinants of RNA recognition by the FinO domain of the Escherichia coli ProQ protein. Nucleic Acids Res 48:7502–7519. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melamed S, Adams PP, Zhang A, Zhang H, Storz G. 2020. RNA-RNA interactomes of ProQ and Hfq reveal overlapping and competing roles. Mol Cell 77:411–425.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milner JL, Wood JM. 1989. Insertion proQ220::Tn5 alters regulation of proline porter II, a transporter of proline and glycine betaine in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 171:947–951. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.947-951.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Lay N, Gottesman S. 2012. A complex network of small non-coding RNAs regulate motility in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 86:524–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rizvanovic A, Kjellin J, Söderbom F, Holmqvist E. 2021. Saturation mutagenesis charts the functional landscape of Salmonella ProQ and reveals a gene regulatory function of its C-terminal domain. Nucleic Acids Res 49:9992–10006. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheidy DT, Zielke RA. 2013. Analysis and expansion of the role of the Escherichia coli protein ProQ. PLoS One 8:e79656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conrad TM, Joyce AR, Applebee MK, Barrett CL, Xie B, Gao Y, Palsson BT. 2009. Whole-genome resequencing of Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 undergoing short-term laboratory evolution in lactate minimal media reveals flexible selection of adaptive mutations. Genome Biol 10:R118. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-r118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Avrani S, Bolotin E, Katz S, Hershberg R. 2017. Rapid genetic adaptation during the first four months of survival under resource exhaustion. Mol Biol Evol 34:1758–1769. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knöppel A, Knopp M, Albrecht LM, Lundin E, Lustig U, Näsvall J, Andersson DI. 2018. Genetic adaptation to growth under laboratory conditions in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. Front Microbiol 9:756. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gross J, Avrani S, Katz S, Hilau S, Hershberg R. 2020. Culture volume influences the dynamics of adaptation under long-term stationary phase. Genome Biol Evol 12:2292–2301. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evaa210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katz S, Avrani S, Yavneh M, Hilau S, Gross J, Hershberg R. 2021. Dynamics of adaptation during three years of evolution under long-term stationary phase. Mol Biol Evol 38:2778–2790. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Figueira R, Watson KG, Holden DW, Helaine S. 2013. Identification of Salmonella pathogenicity island-2 type III secretion system effectors involved in intramacrophage replication of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium: implications for rational vaccine design. mBio 4:e00065-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00065-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S. 2004. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science 305:1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis K. 2008. Multidrug tolerance of biofilms and persister cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 322:107–131. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kutsukake K, Ohya Y, Iino T. 1990. Transcriptional analysis of the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 172:741–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.741-747.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yanagihara S, Iyoda S, Ohnishi K, Iino T, Kutsukake K. 1999. Structure and transcriptional control of the flagellar master operon of Salmonella typhimurium. Genes Genet Syst 74:105–111. doi: 10.1266/ggs.74.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koskiniemi S, Sun S, Berg OG, Andersson DI. 2012. Selection-driven gene loss in bacteria. PLoS Genet 8:e1002787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schavemaker PE, Lynch M. 2022. Flagellar energy costs across the tree of life. Elife 11:e77266. doi: 10.7554/eLife.77266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Linehan SA, Rytkönen A, Yu X-J, Liu M, Holden DW. 2005. SlyA regulates function of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) and expression of SPI-2-associated genes. Infect Immun 73:4354–4362. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4354-4362.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stocker BA, Hoiseth SK, Smith BP. 1983. Aromatic-dependent “Salmonella sp.” as live vaccine in mice and calves. Dev Biol Stand 53:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hill PWS, Moldoveanu AL, Sargen M, Ronneau S, Glegola-Madejska I, Beetham C, Fisher RA, Helaine S. 2021. The vulnerable versatility of Salmonella antibiotic persisters during infection. Cell Host Microbe 29:1757–1773.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Henry T, Garcia-Del Portillo F, Gorvel JP. 2005. Identification of Salmonella functions critical for bacterial cell division within eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol 56:252–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Z, Liu Y, Fu J, Zhang B, Cheng S, Wu M, Wang Z, Jiang J, Chang C, Liu X. 2019. Salmonella proteomic profiling during infection distinguishes the intracellular environment of host cells. mSystems 4:e00314-18. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00314-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Srikumar S, Kröger C, Hébrard M, Colgan A, Owen SV, Sivasankaran SK, Cameron ADS, Hokamp K, Hinton JCD. 2015. RNA-seq brings new insights to the intra-macrophage transcriptome of Salmonella Typhimurium. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005262. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gollan B, Grabe G, Michaux C, Helaine S. 2019. Bacterial persisters and infection: past, present, and progressing. Annu Rev Microbiol 73:359–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dewachter L, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2019. Bacterial heterogeneity and antibiotic survival: understanding and combatting persistence and heteroresistance. Mol Cell 76:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ronneau S, Helaine S. 2019. Clarifying the link between toxin-antitoxin modules and bacterial persistence. J Mol Biol 431:3462–3471. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilmaerts D, Windels EM, Verstraeten N, Michiels J. 2019. General mechanisms leading to persister formation and awakening. Trends Genet 35:401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eisenreich W, Rudel T, Heesemann J, Goebel W. 2021. Persistence of intracellular bacterial pathogens with a focus on the metabolic perspective. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:615450. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.615450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stepanyan K, Wenseleers T, Duéñez-Guzmán EA, Muratori F, Van den Bergh B, Verstraeten N, De Meester L, Verstrepen KJ, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2015. Fitness trade-offs explain low levels of persister cells in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Ecol 24:1572–1583. doi: 10.1111/mec.13127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eriksson S, Lucchini S, Thompson A, Rhen M, Hinton JCD. 2003. Unravelling the biology of macrophage infection by gene expression profiling of intracellular Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol 47:103–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hautefort I, Thompson A, Eriksson-Ygberg S, Parker ML, Lucchini S, Danino V, Bongaerts RJM, Ahmad N, Rhen M, Hinton JCD. 2008. During infection of epithelial cells Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium undergoes a time-dependent transcriptional adaptation that results in simultaneous expression of three type 3 secretion systems. Cell Microbiol 10:958–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McGourty K, Thurston TL, Matthews SA, Pinaud L, Mota LJ, Holden DW. 2012. Salmonella inhibits retrograde trafficking of mannose-6-phosphate receptors and lysosome function. Science 338:963–967. doi: 10.1126/science.1227037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hensel M, Shea JE, Waterman SR, Mundy R, Nikolaus T, Banks G, Vazquez-Torres A, Gleeson C, Fang FC, Holden DW. 1998. Genes encoding putative effector proteins of the type III secretion system of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 are required for bacterial virulence and proliferation in macrophages. Mol Microbiol 30:163–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Coombes BK, Brown NF, Valdez Y, Brumell JH, Finlay BB. 2004. Expression and secretion of Salmonella pathogenicity island-2 virulence genes in response to acidification exhibit differential requirements of a functional type III secretion apparatus and SsaL. J Biol Chem 279:49804–49815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yu D, Ellis HM, Lee EC, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Court DL. 2000. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:5978–5983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100127597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00193-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Porwollik S, Santiviago CA, Cheng P, Long F, Desai P, Fredlund J, Srikumar S, Silva CA, Chu W, Chen X, Canals R, Reynolds MM, Bogomolnaya L, Shields C, Cui P, Guo J, Zheng Y, Endicott-Yazdani T, Yang HJ, Maple A, Ragoza Y, Blondel CJ, Valenzuela C, Andrews-Polymenis H, McClelland M. 2014. Defined single-gene and multi-gene deletion mutant collections in Salmonella enterica sv Typhimurium. PLoS One 9:e99820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stårsta M, Hammarlof DL, Waneskog M, Schlegel S, Xu F, Gynnå AH, Borg M, Herschend S, Koskiniemi S. 2020. RHS-elements function as type II toxin-antitoxin modules that regulate intramacrophage replication of Salmonella Typhimurium. PLoS Genet 16:e1008607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Flow cytometry detection of green fluorescence in a Salmonella SL1344 ΔproQ population carrying the plasmid pFCcGi (64). Bacterial cultures were grown to stationary phase in LB medium supplemented with arabinose (0.2%) to induce GFP expression. Upon regrowth in fresh LB medium without an inducer, dilution of the preformed pool of GFP was monitored during 0 h, 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h. Representative data are shown for one out of three replicates. Data for monitoring fluorescence dilution in an SL1344 wild-type population are shown in Fig. 2B. Download FIG S1, EPS file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Time-dependent antibiotic killing of the Salmonella wild-type strain. Exponential-phase cultures were treated with ciprofloxacin (1 μg/mL; 60× MIC) (A) or cefotaxime (100 μg/mL; 100× MIC) (B), and sample aliquots were taken at the indicated time intervals. CFU counts were determined before and after treatment and normalized to time zero. Average values from nine (A) or three (B) replicates and the standard errors of the means (SEM) are shown. Download FIG S2, EPS file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, eps) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

MICs determined for Salmonella strains using Etest strips. The average values from three replicates with SD are shown. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

CFU counts from a representative in vivo persister assay. Download Table S5, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.7KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Strains used in this study. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (21.1KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Plasmids used in this study. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (18KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Oligonucleotides used in this study. Download Table S4, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13.4KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2022 Rizvanovic et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Data Availability Statement

FCS files from single-cell analysis were deposited in the FlowRepository database and can be accessed via https://flowrepository.org/experiments/5329.